Abstract

The following essay examines Anthony Hernandez’s photographic work from the early 1970s to the present. The essay addresses how Hernandez reimagines the genre of street photography in Los Angeles, countering the misconception that the genre, so dominant in the history of the medium, is nearly inexistent in California.

1. Landscape Without Horizon

There was a term in the army—you might have heard it—but it said everything and nothing and it was constantly used. In Vietnam, it was the attitude. The expression was: fuck it. And it applies here in L.A. It’s L.A. now. And L.A.’s the future.

Architectural literature on most cities ignores the daily grind, the millionfold smalltime commercial transactions, the lives of the workers and the shopkeepers, police and criminals, housewives and teachers, and unemployed and elderly in favor of the few immediate features which apparently distinguish them from other cities.

Dirt. Cigarettes. Scraps of paper. The cover of Anthony Hernandez’s photobook, Landscapes for the Homeless (1995), pictures a ground without a horizon (Figure 1). The photograph is composed of rubbish and garbage. In the center of the image sits a crumpled blanket alongside wrappers, plastic cutlery, and food waste. These scraps index a landscape of economic despair. On the bits and pieces of paper we can read the following words: “CALL 24HRS”, “NEED CASH”, “NEED CREDIT”, “NEW COUPON INSIDE”. The project Landscapes for the Homeless documented the homeless camps, shelters, and objects encountered throughout the streets, underpasses, and densely wooded areas of Los Angeles. Throughout the book one finds a continuation of images similar to this cover image—photographs of rotten vegetables, discarded food containers, and other cast off materials (Figure 2). Also featured are frequent photographs of improvised shelters containing traces of former inhabitants—sleeping bags, pillows, and mattresses. No figures populate the photographs.

Figure 1.

Anthony Hernandez, Landscapes for the Homeless #24 (1990), © Anthony Hernandez.

Figure 2.

Anthony Hernandez, Landscapes for the Homeless #72 (1988), © Anthony Hernandez.

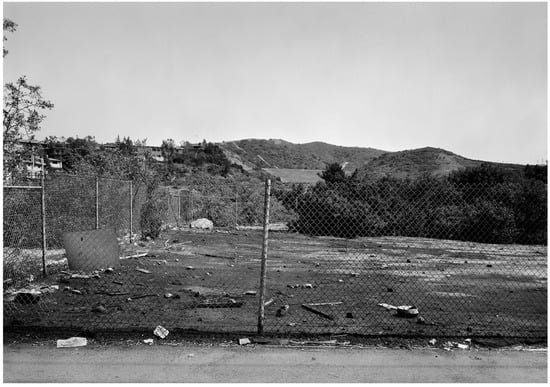

Hernandez shot the photographs published in Landscapes for the Homeless by walking through the streets of Los Angeles. The photobook was first published in a catalogue for an exhibition held at the Spengel Museum in Hannover (September 24–November 19, 1995). Two years later, Hernandez reworked his cover image of absence by republishing a second iteration of the photobook under a different title: Sons of Adam: Landscapes for the Homeless (1997), for exhibitions at the Musée de l’Elysée, Paris (November 22–January 19, 1997), and the Centre national de la photographie, Paris (May 16–August 11, 1997). Unlike the cover of the first edition of the book, which turns to the material substance of garbage—dirt, cigarettes, scraps of paper—Hernandez’s second cover is distanced from the scene and site, screened through the blurry enclosure of a chain-link fence. If placed side by side, the two books, Hernandez imagined, could be read polysequentially—a type of reading that attempts to make sense of the sequential relations between images and the books as a system of continuities and discontinuities, relays and delays, interruptions and anticipations, and successions and simultaneities. One way to think of the polysequential relationship between the two covers is to compare the oscillation of immediacy and opacity—the excess of dirt and cigarettes (immediacy) in contrast to the blurry view through a chain-link fence (opacity).

Although the street and homelessness in Los Angeles served as the central site and concern of the project, the photographs published throughout the two photobooks look nothing like the images conventionally affiliated with the genre of street photography. Hernandez re-imagines the genre through procedures that are both formal and political. The project features no photographs of unwitting subjects in the mode of Paul Strand, no unique urban scenes in the style of Robert Frank. Likewise, there are no photographs of distinctive “urban” events in the mode or approach of Garry Winogrand, and no self-portraits staged on the sidewalk as encountered in the work of Vivian Maier. In many ways, Hernandez’s work is closer to Martha Rosler’s landmark critique of documentary photography and its ties to the street in The Bowery: in two inadequate descriptive systems (1974–1975). That work, which was shot while Rolser walked up and down the long stretch of The Bowery in New York, juxtaposes photographs of de-peopled storefronts with words associated with drunkenness. Despite their clear differences, Hernandez’s work shares Rosler’s austere distance, its view through a chain-link fence as well as its affinity for garbage—cast-off bottles, wrappers, and other detritus found abandoned on the ground. In the shift from subject to object, Hernandez’s work disrupts documentary’s anthropocentric focus by emphasizing traces, vestiges, and fragments.

The following essay will attempt to think the political and aesthetic imbrication between photography and eviction in Los Angeles. Hernandez’s work distinguishes itself formally, aesthetically, and politically from the conventions of the genre of traditional street photography by appealing to a complicated dialectic between material presence and absence, interior and exterior space, center and periphery. It is a set of contingencies that contemporary Los Angeles, as opposed to a city like New York, was particularly poised to provide.

2. The Evicted

Art historian Abigail Solomon-Godeau has recently questioned the legitimacy of “street photography” as a genre within the history of photography. Her critique extends to the discursive construction of photography—via the museum, curator, critic, and historian—that desires to “discipline” photography by confining it to a distinct genre—“landscape photography”, “street photography”, or “documentary photography” (Solomon-Godeau 2017a, p. 2). She claims other distinctive art historical genres, such as “the nude” or “the landscape” (emphasis in the original), derive from the fields of art history and art criticism, whereas a genre such as “street photography” is medium specific.1 Her critique is encapsulated by the observation that even though there are hundreds of “paintings of the street”, there is no genre called “street painting” (ibid., p. 78). One could question Hernandez’s project similarly: Where is this “street” located in his series? Is “the street” encountered, literally, on the dry dirt ground? Or is “the street” encountered within the covered enclosure of the underpass? Or is “the street” found in the crumpled and faded bits of paper?

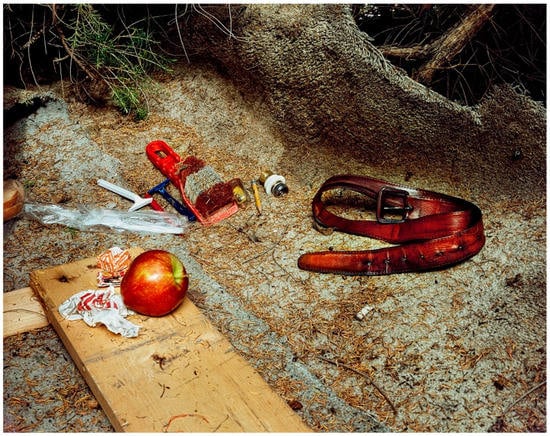

A key difference between Hernandez and canonical figures such as Frank and Winogrand is the oscillation between related oppositions—immediacy and opacity, the excess of poverty, and the obscurity that lies at the heart of many of his photographs. These images do not yield immediate readings or easy narratives. Although Hernandez shot his project in and around the margins of Los Angeles—underpasses, highways, and abandoned lots—he equally turned his camera to seemingly interior scenes or spaces. His photographs are often populated with objects found in kitchens, living rooms, or bedrooms—cutlery, blankets, cups, window-panes, belts, razors, pots and pans, and a telephone. In one photograph from the series, a window is propped up on the branch of tree. Hernandez consistently addresses this “interior” condition by alluding to the improvised strategies through which the subjects who reside in these precarious sites assert their privacy (Figure 3). In a number of photographs from the series, we see cardboard and plywood propped up by nails and stakes to construct a provisional wall between the concrete underpass, bridge, and street (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Anthony Hernandez, Landscapes for the Homeless #14 (1989), © Anthony Hernandez.

Figure 4.

Anthony Hernandez, Landscapes for the Homeless #22 (1988), © Anthony Hernandez.

In another photograph, a blanket is draped on a string to provide shade, but also to shield the camp from visibility, implicitly blocking the site from the photographic lens. Instead of crossing the threshold, the camera stands back at a distance. Many of Hernandez’s photographs flirt with opacity. This coupling of distance and obscurity is referenced in innumerable photographs of clothes and objects hung on branches of trees, suggesting a haunting absence of a human presence (Figure 5). What are we to make of this configuration of absence? Thinking through this peculiar oscillation between immediacy and opacity, interior and exterior limits, public and private space, as well as excess and paucity, is one way to begin to rethink the project’s political relation to the street (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Anthony Hernandez, Landscapes for the Homeless #54 (1989), © Anthony Hernandez.

Figure 6.

Anthony Hernandez, Landscapes for the Homeless #15 (1989), © Anthony Hernandez.

As argued by a number of critics, including Allan Sekula, Rosler, and Solomon-Godeau, the politics of the street have been often characterized by a “look-down” from the photographer who has historically approached the disenfranchised as a passive subject.2 This “look down” from the photographer was a look often associated with a range of conflicting sentiments—didactic, sociological, ameliorative, and moralizing—tied to the project of liberal humanism.3 Reading Hernandez’s photographs, however, pushes the following questions to the fore: What would a project not aligned to a project of “liberal humanism” look like? Could photography’s pessimism and negativity be mobilized for political ends?

In photographer Lewis Baltz’s published conversation with Hernandez, he described Landscapes for the Homeless as a project that pictured the conditions of shelter at “degree zero” (Hernandez and Baltz 1995, p. 13). Baltz’s reading of Hernandez’s work was premised on the rejection of two conventional interpretations of images of poverty.4 For Baltz, Hernandez’s photographs neither “exploit” the homeless by turning their image of suffering into a spectacle (an easily digestible image for middle-class consumption), nor does Landscapes for the Homeless desire to have its images “speak for” the homeless. In contrast, Baltz’s claims that the value of Hernandez’s project lies in its power to draw our attention to the lives and shelters of “the evicted”. For the two photographers, eviction is a central concept around which Landscapes of the Homeless pivots. Central to Hernandez and Baltz’s discussion is the inadequacy of the term “the homeless” as a political concept (the bold italics text indicates Hernandez’s voice as it appears in the publication):

Even the word homeless, as a noun, is recent. The Homeless, neither voters nor consumers, disenfranchised and without economic subjecthood, have rather suddenly become a permanent fixture in America’s ossifying caste system. Like Iraqi civilian casualties in the Gulf War, their precise number is elusive. Let’s say they are many. Very many. That term, “The Homeless,” as if they were an organized group, a group with rights, a group you belonged to. If one weren’t implicated in the commonplaceness of their existence, that is, if the homeless weren’t such a present feature on the social horizon, one might find the distance to inquire as to why such a class exists at all in the United States. One might ask what sort of poor, shitty country it is that has so little self-respect as to allow its citizens to sleep in doorways and beg for food. Questions like this don’t get you very far. It’s a matter of priorities. That’s how it is. It’s a free country. Both the rich and the poor have the right to sleep under bridges. Why don’t they just go away? They’re already away. They’re “home.” They’ve been “evicted,” a word which, unlike “homeless,” speaks volumes.

Although Hernandez and Baltz emphasize how the label “the homeless” is inadequate when compared to the term, “the evicted”, Hernandez (without explanation) keeps the former in the work’s title. To continue this discussion of semantics, other aspects of Hernandez’s title are more ambivalent than politically suspect. Does the “for” in Hernandez’s title imply that these photographs were made “for” the homeless? Or does it imply that this book is “for” their appreciation, a means to alleviate or ameliorate their plight? Or are these “landscapes” the only places “for” the homeless to safely and securely reside without imminent threat from the police, private landlords, or other members of the public that resent their existence? The “for” in Hernandez’s title is somewhat ambiguous. Likewise, in the project’s focus on “interior” objects, scenes, and spaces, it is harder to claim that Hernandez’s photographs navigate the genre of landscape as his title suggests, especially because the project seems formally and politically closer to the historical and painterly genre of the still life (Figure 7). Hernandez’s work in this regard finds its closest equivalent to Dutch still life but with an added twist. As Simon Schama argues in The Embarrassment of Riches (1997), the fruit of Dutch still life was always captured at its perfect point of ripeness. For Schama, this was clearly a metaphor for what happens when you live in prosperity—you are always on the brink of disaster. In Hernandez’s series, however, the disaster is ever-present—rot and decay have wholly colonized the image (Schama 1997).

Figure 7.

Anthony Hernandez, Landscapes for the Homeless #29 (1989), © Anthony Hernandez.

One should note that throughout Hernandez and Baltz’s conversation, continual reference is made to war and conflict as a means to reimagine the political and public nature of Hernandez’s project. In fact, Hernandez appears to subtly reference this condition in the cover image of Landscapes for the Homeless, in the mimetic association of hundreds of cigarettes with shell casings of bullets, which are in essence a material indication of absence. Through this comparison, one is able to see how poverty and homeless is reimagined and understood as a type of “civil war”, in this instance envisioned as a type of class war, which is to say a war waged by other means. It should be stressed, here, that the end of the Vietnam era in the early 1970s coincided with the dawn of neoliberal policies and the radical downgrading of public structures.5 Baltz makes this argument explicit in his conversation with Hernandez.

Like many other desert flora L.A. is mostly sharp edges, and Hernandez has worked along a lot of them. In some ways formed by war, Anthony Hernandez photographed America’s undeclared civil war as though it was always/already Vietnam, or Beirut, or Bosnia. Usually he witnessed the defeated (they are, after all, the majority) waiting, walking, waiting more, taking very, very humble recreations. One time he gathered evidence about the winners, the lumpen rich, enjoying spoils of their victory on Rodeo Drive. And here, now, this time, the casualties, the already triaged. The evicted.(Ibid., p. 15)

A number of questions emerge from this statement: What does it mean to continue to take photographs of the spaces of “the unseen”, “the forgotten”, and “the evicted”, as Hernandez and Baltz call them? Secondly, how does Landscapes for the Homeless challenge and disrupt the conventions, tendencies, and assumptions of the history of street photography? The answer to these two questions, I argue, finds its root in a number of earlier projects that Hernandez began in the late 1970s that detailed the neglected, racialized, and working-class spaces of the city of Los Angeles. Hernandez’s photographic work is read alongside the writings of his friend, the photographer and historian Allan Sekula, who argued that the genre of documentary in Los Angeles in the 1990s had been “evicted” from the historical and social imaginary. What Sekula called for instead was a dialectical counter-argument that pushed up against the environment of eviction and historical forgetting that has symptomatically characterized the cultural ecology and photographic history of Los Angeles. It is my argument that Hernandez’s work from the 1970s was one place to enact this project cultural retrieval and reevaluation.

3. Reworking the Street: Los Angeles in the 1970s

Almost two decades before Hernandez photographed the homeless camps of Los Angeles, the photographer first turned his camera to working-class spaces and sites of the city, an evolution that is crucial to his reworking of the genre of street photography. Hernandez grew up in the barrio of East Los Angeles, a short walk away from the east side of the Los Angeles River, where a number of the photographs in Landscapes for the Homeless were taken years later.6 As a teenager in the 1960s, Hernandez attended East Los Angeles College (ELAC) with the initial idea of becoming a commercial photographer.7 However, in 1967, at the youthful age of nineteen, he was drafted into the U.S. Army and spent fourteen months in Vietnam working in a Medivac helicopter. When he was not in the field, flying over Southern Vietnam and attending to the wounded, he would read the pages of Artforum, a publication he received, unexpectedly and unannounced, from his aunt Dolores back in Los Angeles (ibid., p. 16). Hernandez returned to Los Angeles in 1969 and in his free time he would walk through downtown and along Wilshire Boulevard pretending to take photographs with his Nikon 35 mm camera. In these early studies, his camera was not loaded with film. For Hernandez, this exercise was a means to relearn the critical faculty of photographic vision. He stated in a 1990 LA Times interview: “Being aware is more important than the evidence of the awareness on a piece of paper. Being sensitive to what passes in front of you is more important than what passes into the camera” (Anthony Hernandez quoted in Parker 1973, p. 9).

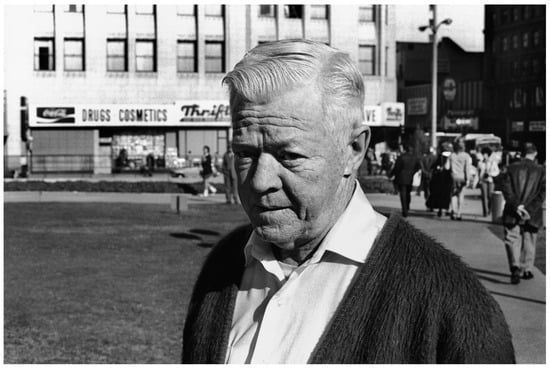

When Hernandez photographed the pedestrians of downtown Los Angeles in the early 1970s, he positioned himself directly along the path of his subjects and set his camera’s lens so that anything at arm’s-length would be in focus. In each image, the camera assumes a confrontational proximity (Figure 8). In Hernandez’s series, the towering buildings of downtown Los Angeles provide the backdrop to the work. Stretching across the horizon is the signage of the Broadway Arcade Building, Desmond’s Department Store, C.H. Baker Shoes, Forum Cafeteria, KRKO Radio tower, Petrie’s and Thrifty Drug—stores that make up what historian Mike Davis has called “the great Latino shopping areas of the city” (Davis 2000, p. 79). Davis remarks that Latinx communities encountered in Downtown and Boyle Heights during this period had more in common with the early twentieth-century city than they do with a “death wish of postmodernity”, which Los Angeles is often associated (ibid.).

Figure 8.

Anthony Hernandez, Los Angeles #6 (1971), © Anthony Hernandez.

Captured from either waist height or eye level, half of his figures appear oblivious to his presence, while the other half recognize the situation and respond with a harsh or perturbed look. Two photographs from the series, for instance, figure two separate subjects shielding their face from Hernandez’s camera—one figure, framed against a tiled wall, crouches and covers his face with a few slender pieces of paper, while the other grips his face with his right hand, unclear whether he is covering himself from Hernandez’s camera or whether he was simply absorbed in thought or emotion (Figure 9). Other figures appear to register Hernandez’s presence, but on the whole most appear unaware or unconcerned by the situation, generally indifferent to the scene and the world around them. The expressions that meet Hernandez’s camera range from the hostile to the confused, from the aggressive to the blasé. In a sense, the pedestrians in Hernandez’s series often appear disconnected, producing a general sense of alienation and distance, despite the camera’s extreme proximity. If there is a trace of community or conviviality to these photographs, it is at the margins of the image, evidenced in small couples or groups.8

Figure 9.

Anthony Hernandez, (a) Los Angeles #1 (1971); (b) Los Angeles #7 (1969), © Anthony Hernandez.

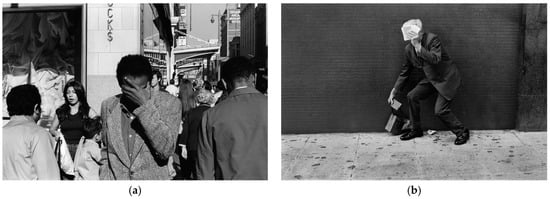

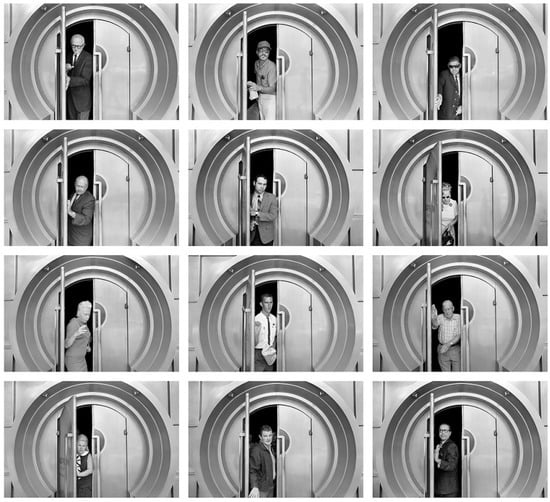

One extraordinary work from the period, Los Angeles (1970) (Figure 10), photographs a sequence of pedestrians exiting a downtown restaurant through its metal doors. Framed by the building’s circular metal doors, the figures represented in the sequence appear as if they themselves were simply the stuffed contents of a tin can. In many ways, this particular work shares many similarities with Allan Sekula’s own photographs of factory workers exiting the General Dynamics Convair Division plant in San Diego California for his series Untitled Slide Sequence (1972). For the project, Sekula climbed atop the pedestrian stairway and photographed its workers leaving the factory. To realize the project, he envisioned himself as a union militant handing out leaflets to the unorganized Convair workers (Risberg and Sekula 1999, p. 240) At the time, the Convair factory was a central cog in the American War in Vietnam, engaged in the production of Atlas and Centaur rockets used in the aerial bombardment of Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia—conditions which made it illegal to photograph on the company’s grounds (ibid.).

Figure 10.

Anthony Hernandez, Los Angeles (1971,) © Anthony Hernandez.

Similar to Hernandez’s photographs of the pedestrians of downtown Los Angeles, Sekula’s Untitled Slide Sequence is a work of extremes. The latter’s framing oscillates between a position of acute frontality and extensive depth. At times, the bodies of these workers obscure the perspectival depth of the image, but in other instances the photo’s perspectival depth seems to recede, infinitely, into the sun-drenched horizon. Initially, hundreds of laborers are represented at once, and yet only a few minutes later only a handful are figured by Sekula’s camera. The first image from Sekula’s Untitled Slide Sequence (1972) shows a sea of figures streaming outwards from the factory yard. The other twenty-four images of laborers, shop foremen, middle management, secretaries, and security guards are structurally similar. Formally, Sekula’s camera is pointed down the stairwell, just above the security office, and the extreme foreshortening makes it look as though each worker is surging forth to break the plane of the image.

For the duration of the sequence, Sekula’s lens adjusts to the flow of bodies as they make their way up the stairwell, tacking back-and-forth along the overpass, forcing each worker to adjust to his position. Both Hernandez and Sekula adopt this confrontational position—a position that purposefully “gets in the way” of each subject. When there is a lag in flow, each camera adjusts to find another body to photograph. Sekula’s camera can be seen, repeatedly, jostling for position. Under this continuous movement, Untitled Slide Sequence reads not as a static recording of workers leaving the factory, but a performative occasion where Sekula matches the workers’ movements with his confrontational stance. If the faces of Sekula’s subjects were isolated, the expressions that greet his camera range from the hostile to the confused, the suspicious to the indifferent. And similar to Hernandez’s photographs of downtown Los Angeles, Sekula’s camera is mobilized not as a means to mirror or reflect reality but to interrupt and intervene in it.9

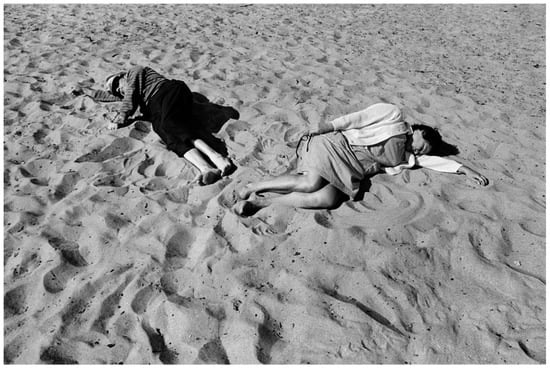

Notably, in 1971, while Hernandez was completing his series on the pedestrians of downtown LA, the photographer participated in the exhibition The Crowded Vacancy at the Pasadena Art Museum (June 29–August 29, 1971), alongside Lewis Baltz and Terry Wild. The curator of the museum, Fred Parker, decided to include Hernandez’s photographs of downtown Los Angeles’ pedestrians to counterpose Baltz’s and Wild’s anonymous photographs of non-distinct Los Angeles buildings and landscapes. In contrast to Baltz’s and Wild’s photographs of unpeopled waiting rooms, abandoned garages, and vacant sidewalks, Hernandez turned his camera to the sunbathers near Santa Monica Pier and the pedestrians of downtown Los Angeles (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Anthony Hernandez Santa Monica # 14 (1969), © Anthony Hernandez.

No accompanying essay was published in the exhibition catalogue. A short compendium of the demographics of Los Angeles, however, was included. The catalogue merely listed that “Los Angeles County” included 7,032,075 people, 2,575,789 dwellings, and 4,668,761 automobiles. Missing from this demographic is any mention of the distinctions of race, class, or gender. In many respects, the exhibition’s title, The Crowded Vacancy, was a contradiction. The photographs included in the exhibition taken by Baltz and Wild did not emphasize the “crowded” aspect of Los Angeles County, per se, but the vacant nature of the landscape. If Baltz’s and Wild’s photographs expunged the subject from their work, Hernandez’s photographs were distinctively figurative in their nature, situating the subject outside of malls, along sidewalks, and sleeping near the beach of Santa Monica Pier; spaces that were hardly crowded.

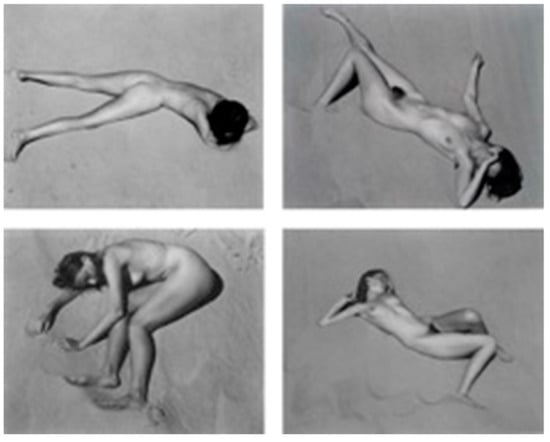

Hernandez’s beach photographs formally echo Edward Weston’s photographs of his wife, Charis, in Nude on Sand (1936) (Figure 12).10 In contrast, Hernandez’s figures appear fully clothed and physically depleted. Exhaustion and collapse are palpable conditions throughout the series, as if each figure was too tired to remove the clothes off of their back. By no means are these photographs images of Southern Californian leisure. In a remarkable move, Hernandez pushes the state of exhaustion almost to the point of death. In many photographs from the series, Hernandez frames the body as corpse. This framing is most notable in, Santa Monica #2 (1970) (Figure 13), which echoes the extreme foreshortening found in Andrea Mantegna’s Lamentation over the Dead Christ (1480). Similarly to Mantegna, Hernandez underscores the subject’s feet, a signifier of the body’s common and corruptible flesh.

Figure 12.

Edward Weston, Nude on Sand (1936), © courtesy of private collection.

Figure 13.

Anthony Hernandez, Santa Monica # 2 (1970), © Anthony Hernandez.

4. Los Angeles from the Middle-Distance

Hernandez’s photographs of the beaches and sidewalks of Los Angeles were shot during a significant period of economic restructuring. During the 1970s, Los Angeles was subject to crippling deindustrialization, resulting in job losses and plant closures. For the political geographer Edward Soja, the 1970s marked the end of the long US postwar economic boom, which signaled the beginning of a type of “crisis-generated” restructuring of the economy and social space (Soja 2014, p. 17). In the wake of the urban riots of the 1960s, Los Angeles sought a “spatial-fix” to address widespread economic and social blight. For Soja, by the late 1970s, the US had entered a new post-Fordist phase of the economy, defined by a pronounced centralization of new forms of production and employment, as well as a marked escalation of international investment and finance throughout downtown Los Angeles.11

In part, this “spatial fix” was an attempt by the local government to rebrand Los Angeles as a “world class city”. An attempt that was advanced in particular by Mayor Tom Bradley, the first elected black mayor in any major U.S. city, who came to power in 1973 and in the wake of the Watts Riots. In 1975, Bradley established an Economic Development Office for Los Angeles to encourage the investment of international capital to the city, as well as the increased allocation of federal funds for large-scale downtown development.12 To encourage the investment of international capital into the city’s downtown core, the city was reimagined as an international hub for finance capital—a “crossroads city”—on par with London and New York, but with the added bonus of a gateway to the Pacific Rim (ibid.). Between 1972 and 1982, Soja notes that over thirty million square feet of high-rise office space was built (ibid., p. 49).

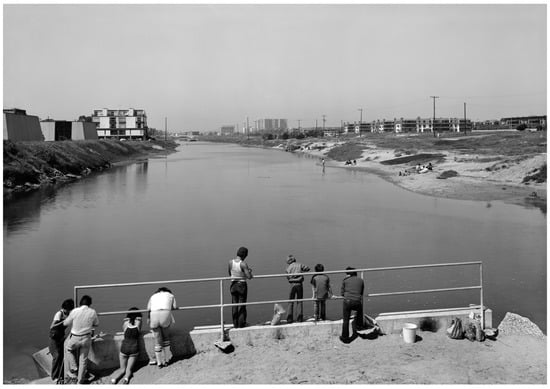

In the late 1970s, Hernandez purchased a large-format 5 × 7 Deardorff view camera and developed a series of photographs of bus stops, car repair shops, fishing holes, and public courtyards. Hernandez titled the four works Public Transit Areas (1979–80), Public Fishing Areas (1979–82), Public Use Areas (1979–81), and Automotive Landscapes (1978–79). The four series rejected a car-centric view of the street and city associated with mobility, freedom, and privacy. In contrast, the photographer focused on a slower, public city, where forms of mobility and freedom ran aground. The formal qualities of Hernandez’s 35 mm camera work, characterized by skewed perspectives, odd cropping, and intense close-ups, is exchanged for a detached and cold tripod-based camera work. In this later work, there is an almost obsessive emphasis on traditional perspective and an absence of cropping, while human figures are photographed not in their immediacy, but from a middle-distance perspective.

Each project was defined by a strict procedural condition—a full-frontal approach to its subject, consistent midday lighting, the placement of the figure or group in the middle distance of the image, a receding picture plane, and a common topology for all sites in a given series (such as bus stops, fishing holes, and public use areas) (Figure 14).13 For the series, Automobile Landscapes, the photographer turned his camera to car dealerships, repair shops, and other sites of automotive repair (Figure 15). To complete the series, Hernandez wandered through the outskirts of Los Angeles searching for these landscapes of wreckage, ruin, and disaster. The four projects were premised on picturing the unremarkable spaces of the city, which the passing automobile never encountered in its immediacy (or only encountered in passing)—the working-class sites and spaces where people commuted between jobs, ate their lunch, and went fishing. “The guts of L.A.”, as the art critic Peter Plagens called it at the time (Plagens 1972, p. 69).

Figure 14.

Anthony Hernandez, Public Transit Areas #3 (1979), © Anthony Hernandez.

Figure 15.

Anthony Hernandez, Automobile Landscapes # 35 (1978), © Anthony Hernandez.

Why then did Hernandez adopt a different technical vocabulary? In some respects this question might seem like a false one. Instead of representing a regressive, or even anachronistic move, the “slowness” of Hernandez’s large format work reads as a temporally appropriate and approximate means to figure the subject and the city—a slower mode of working that appears coterminous with its subject. In this frame, the slowness of photographic act aligns with his subjects as they wait for a bus, eat their lunch on an administered break, and idle as they wait for car repairs. Moreover, this theory of the photograph offers up a counter-image of the accelerated and dispersed movements of Los Angeles, premised on the circulation of labor, commodities, and information, aided primarily by the automobile. Hernandez turned to the city’s slower, working-class landscapes—bus stops, public use areas, fishing holes—not only to reflect on the medium of photography and its attendant modes of observation and picturing, but also as a means to mobilize an alternative representation and temporality of the city (Figure 16). Even though Hernandez’s turn to large format work represented a slower way of working, it did not represent a distinct shift in the conditions, subject, or mode of observation.

Figure 16.

Anthony Hernandez, Public Fishing Areas #30 (1979), © Anthony Hernandez.

In the context of Los Angeles photographic history, Hernandez appears situated between the photographic work of Frank and Winogrand, who both photographed pedestrians while visiting Los Angeles, but also the conceptual work of Baltz and Ed Ruscha, who both photographed the nondescript spaces and buildings of Los Angeles (gas stations, parking lots, and industrial buildings). In Public Transit Areas, for instance, Hernandez shows his subjects sitting, standing, and waiting for a bus. These figures assume a range of poses: some are slouched over, some are standing, some are lost in thought and some throw their gaze towards Hernandez’s camera—puzzled, concerned, or nonplussed. In one photograph, composed at the intersection of Vermont Avenue and Wilshire, the scene is framed as a moment of anticipation. In the first photograph in the series, Hernandez finds his subject waiting adjacent to the Bob Hope Airport, turned away from the camera in profile perdu (“lost profile”), positioned across from the airport’s major parking lot. Another photograph taken along the Pacific Coast Highway shows a shirtless man trying to hitch a ride while waiting at a bus stop as cars speed past. Surrounded by a world of movement—planes, cars, and buses—Hernandez’s figures are almost always immobile and stranded, as if waiting for a bus that will never arrive.14

This type of anticipation found in Hernandez’s work is different to what Jeff Wall has called the “dynamic anticipatory framing” associated with 35 mm street photography. These are not the “decisive moments” encountered in the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson. Cartier-Bresson, Lee Friedlander, as well as Winogrand—the whole corps of leading street photographers—emphasized their quickness: their agility with which they moved through spaces and crowds and the cunning maneuvers that permitted them to capture their subjects by surprise. Wall claims that they tended to see themselves as predators or hunters (Wall 2009, p. 15). In contrast, Hernandez’s anticipatory framing is slower and more methodical. “Hernandez deliberately slowed his movement down in making these pictures”, Wall writes. The conventional “street photographs”, Wall claims, tend to concentrate on figures, either individuals or crowds, and so the surrounding environment and architecture are less prominent. In contrast, Hernandez inverts these terms by placing the figure in the middle-distance. The figure no longer dominates the photograph (Figure 17). “The result is a new vision of the photograph of the street”, Wall states, “no longer strictly speaking a ‘street photograph’” (ibid., p. 15).

Figure 17.

Anthony Hernandez, Automotive Landscapes #42 (1978), © Anthony Hernandez.

And yet, the concept of “anticipation” that is so central to the work of Cartier-Bresson is not discarded altogether. If there is a hint of “anticipation” found in Hernandez’s series, Public Transit Areas, it is, indeed, found in the gestures, movements, and poses that his figures strike. One figure in Public Transit Areas, for instance, stands close to the curb and leans out onto the street to look out for an arriving bus. Ironically, a sign in the background states, “don’t get stranded,” while two buses stream past the intersection perpendicular to this figure, suggesting that these figures are stuck in some interminable limbo. As a group, no one seems to care for or to speak to one another, and, generally speaking, most bus riders in the series do not even appear to look one another in the eyes. They merely exist alongside one another at a bus stop. The ensemble that gathers at the bus stop is interchangeable and instrumental, representative of a particular social and historical form of isolation.15

Hernandez’s work throughout the 1970s can be read as a distinct form of abstraction where the figure is subsumed, in whole or in part, into the social landscape in which he or she is situated. In a sense, Hernandez’s series is founded on an abstract grammar that navigates the midway point between distance and proximity, figure and ground, landscape and portraiture, subject and object. The projects are unified in their serial form where each portrait figures the subject and the city within an interstitial space of the city—spaces of waiting, leisure, torpor, and boredom. “The idea I really liked”, Hernandez once claimed about his photographs of Public Transit Areas, “was that I could take the same picture over and over again. They would be the same in general but always different” (Hernandez 2016). In a sense, Hernandez’s series signals a unique form of social leveling—each figure is united in their common activity. This form of abstraction is placed in contrast to the unique geographic specificity of each bus stop. In the series, the social landscape of Los Angeles is represented as many things—a low-rise series of apartments, a rambling weed-infested lot, a fenced-in playground, a bank façade, a billboard for vodka, an empty parking lot, a domestic appliance store, and a cliffside near the beach. The background is as variously particular as it is abstract. Considering these abstract characteristics, the city appears as an indifferent landscape lacking distinguishing characteristics.

This middle distance perspective is similar to the perspective adopted by Rosler in her photo-text piece, The Bowery (1974–75). The photographs are at once analytically composed and highly descriptive. And yet, unlike Rosler’s Bowery, which turns away from the “overexposed” human subject—the so-called “bowery bum”, subject to numerous photographic and sociological studies—Hernandez’s camera balances the particular against the general, subject against landscape, such that these oppositions slide into one another. Unlike Rosler, Hernandez focuses on the bodies of working-class subjects. His camera does not linger on a “white” Los Angeles, but a multi-ethnic city made up of Chicanas, Latinos, African Americans, and Asians. The subjects are not the city’s illustrious—celebrities, movie stars, or developers—but those who take the bus, fish, and work in offices in downtown Los Angeles. From Hernandez’s perspective, race is not merely conveyed through its geographical specificities or its cultural localities, but is filtered through an economic lens. Hernandez’s photographs draw our attention to the profound transformations of working-class Los Angeles culture and identity in the 1970s.

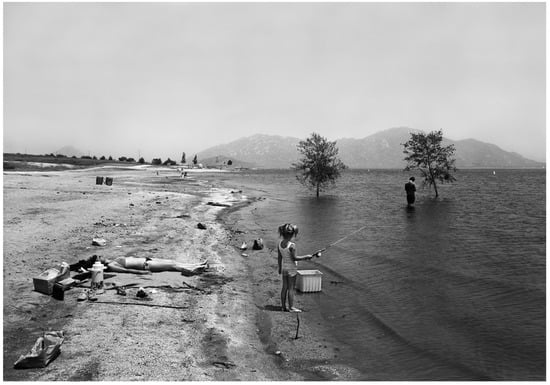

In Public Fishing Areas, for instance, Hernandez takes the habitual, rarely photographed landscapes of a working-class family as its background. Yet, unlike Public Transit Areas, where the landscape is rendered everyday and common, Hernandez’s fishing spots appear all together unworldly, strange, and almost post-apocalyptic. He does not show bucolic images of families sitting along picturesque rivers and lakes throughout Los Angeles County. Instead, he mobilizes the Los Angeles landscape as occupied by invasive industry (Figure 18). One photograph, situated at Legg Lake, figures a Latino family fishing in a dry and polluted river, surrounded by a forest of power lines. At Lake Ferris in the Moreno Valley, a woman and child recline on the water’s edge as a man wades out into a body of water amid two submerged trees (Figure 19).

Figure 18.

Anthony Hernandez, Public Fishing Areas #17 (1979), © Anthony Hernandez.

Figure 19.

Anthony Hernandez, Public Fishing Areas #51 (1982), © Anthony Hernandez.

At Marina Del Mar, along the San Luis Rey River, children and teenagers fish along a concrete bunker, flanked by the ruins of a new condo development. From this perspective, East Los Angeles appears as a sprawling and uneven development, punctuated by concrete embankments, auto-wrecking yards, and landfills. And yet, amid the deadened ruins of a city’s infrastructure—crumbling dams, nightmarish power-lines, and polluted rivers—working-class families assemble and fish. If there is an image of catastrophe found in Hernandez’s series, this photograph is the closest to it. And yet, his series, Public Fishing Areas, is not altogether negative. Hernandez appears to counteract the urban disaster of Los Angeles—sprawl, smog, and segregation—with an image of familial bond. The collective subject appears to have endured such disaster and has found their community and commonality amongst the ruins of late capitalism.

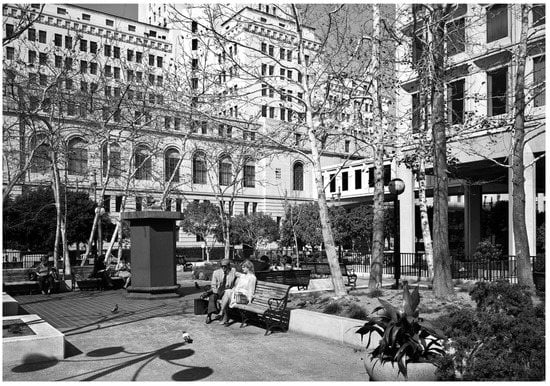

Along a similar trajectory but seen through a different political valence, Hernandez’s series Public Use Areas addresses the other sites and spaces of carceral capitalism—downtown Los Angeles (Figure 20). In the series the sprawling forecourts of the Hall of Records, Los Angeles County Municipal Court, Los Angeles County Criminal Appeals, Caltrans District VII, and the Kenneth Hall of Administration all feature in his work. In contrast to the marginal spaces and sites found in Public Transit Areas, Public Fishing Areas, or even Landscapes for the Homeless, the sites featured in Public Use Areas are the sites and buildings of “official” Los Angeles history—buildings that develop city policies, craft ordinances, fulfill legislative functions, administer tax records, maintain police files, alongside a whole range of other bureaucratic duties. These duties, of course, are not represented in Hernandez’s series. What is remarkable about this series is that he animates the very moment when these bureaucratic activities are suspended. For instance, in its first photograph a woman is shown sitting on a marble embankment eating a bag of crisps surrounded by a forest of tropical palms. Beyond this cultivated garden, the peak of city hall reaches over the skyline. The sitter is situated at the nexus of downtown, between the Kenneth Hahn Hall of Administration, the Hall of Records and the Los Angeles County Municipal Court, which is to say, the sites and spaces which feature as the locus of official municipal history.

Figure 20.

Anthony Hernandez, Public Use Areas #17 (1981), © Anthony Hernandez.

Another photograph from the series Public Use Areas pictures a woman away from downtown in Century City, reading a book while reclining on a grassy knoll above a concrete embankment. The woman sits directly across from the towering glass façade of the Bank of America building. A slight breeze has swept her hair across her face and appears to disturb the long grass on which she lays (Figure 21). A different photograph from the series, posed on the elevated garden within Equitable Plaza, shows two figures sitting in a garden forecourt built above the receding horizon of Mariposa Avenue. One could characterize Hernandez’s photographs from this series as a type of “urban pastoral”—a landscape of tropical palms, rolling fields, reclining figures in nature, enclosed within an imposing corporate structure clad in towering steel and glass. Garry Badger has made this observation in his essay on Hernandez’s photographs: “These walkways and plazas are hardly welcoming. That is, they are not designed for sitting out, as say Italian piazzas are made for sitting out. Rather, they are defensive spaces, moats around corporate castles, and there is little in the way of comfortable seating to encourage their use and genuinely communal spaces” (Badger 2007). In this frame, one can recall Baltz’s photographic series, The new Industrial Parks near Irvine, California (1974), a project which explicitly sought to draw out the contradictions in the expression “industrial park”, an expression, as Sekula has noted, that transforms sites of capitalist production into spaces of imaginary leisure (Sekula 1984, p. 233). Hernandez’s pastoral mode directly confronts how this trope is translated in the context of post-war Los Angeles, characterized by smog, indifference, sprawl, hostility, and waste.

Figure 21.

Anthony Hernandez, Public Use Areas # 25 (1980), © Anthony Hernandez.

The most striking image of this hostility is found in Hernandez’s photograph of a shirtless black figure sitting in the foreground in an empty courtyard, surrounded by the imposing structures of the Los Angeles County Criminal Appeals and City Hall. Although the sitter exudes a sense of freedom and liberty, there is a dark, carceral tone to this image, as if the Los Angeles County Criminal Appeals building and City Hall were bleak new-age fortifications. This carceral condition is symptomatic of Los Angeles generally; as more and more of the urban territory is dominated (and gentrified) by the private interior of the car, freedom becomes the freedom of privatized movement, reinforced by the proliferation of gated communities and armed guards (Davis 2009, pp. 221–65). Local critical geographer Steven Flusty has called the high-rise offices featured in Hernandez’s series as “world citadels”, high-rise offices set back from adjacent properties within an empty plaza usually outfitted with surveillance cameras and their own private security force (Flusty 1994, p. 13). The irreverence of Hernandez’s figure, captured here in the simple gesture of lying down on a park bench, shirtless, holding a stick, is placed in contrast to the severe buildings, sites, and structures situated in the subject’s periphery (Figure 22). To emphasize a point, these are the same buildings that administer and control the accelerated movements of the city and its subjects, most often as we have also seen in Landscapes for the Homeless, through the subtlety of economic enclosure and violence. Hernandez configures the residues of violence and disaster upon which these institutions administer on the sites, spaces, and bodies of working-class Angelinos. In Hernandez’s frame, photography is tasked with the responsibility to marshal the traces and residues of economic violence and class war which remain visible on the landscape of the city, either as an excessive trace (as evidenced in Landscapes for the Homeless) or through sites and spaces of enclosure (as alluded to in Public Use Areas). Hernandez’s photographic work provides shape and texture to the sites of economic hostility found dispersed throughout the streets of Los Angeles.

Figure 22.

Anthony Hernandez Public Use Areas # 24 (1980), © Anthony Hernandez.

5. Waiting for Los Angeles

Hernandez’s project is complicated and historicized when read in dialogue with the writings and photographic work of Sekula, a principle interlocutor of Hernandez throughout the 1990s. Notably, when Hernandez was completing Landscapes for the Homeless, Sekula was also working on his most well-known photographic project, Fish Story (1989–95), which explicitly engaged with the urban histories of eviction and displacement in Los Angeles.16 This thematic was explored further by Sekula more than a decade after completing Fish Story in the exhibition Facing the Music: Documenting Walt Disney Concert Hall and the Redevelopment of Los Angeles in CalArt’s REDCAT gallery, Los Angeles (14 April–29 May 2005). The exhibition’s catalogue was published posthumously by the artist’s friend, Edward Dimendberg in 2015. The catalogue featured an unpublished essay by Sekula, “Los Angeles: Graveyard of Documentary,” which had been previously presented at the Getty Research Institute in March 1997, and revised for the Opler Lecture delivered at Harvard University on April 15, 1999. The essay detailed how Los Angeles, as a city, defied the documentary genre. In his paper, Sekula outlined thirteen theses through which social documentary in Los Angeles seemed “impossible”. “Urban form”, reads one thesis, “resists all traditional forms of social description. Physiognomy is impossible from the automobile. Distance frustrates social comparison”.17 In Sekula’s frame the city, often represented as sprawling and superficial, appears indifferent to the violence of history and the immediacy of social struggle.

To make his argument, Sekula deployed a semiotic understanding of the distinctions between a genre’s “overcoding” and “undercoding”; a distinction between work that operated along existing codes (overcoding) and work that moved within non-existent codes to potential codes (undercoding) (Sekula 2015a, p. 171). For Sekula, previous art historical interpretations have historically overcoded the genre of documentary in particular urban and rural sites—working-class housing and the sidewalks of New York, the steel mill towns of Monongahela valley and the sharecroppers, tenant farmers and migratory agricultural workers of the 1930s Dust Bowl. Meanwhile, the city of Los Angeles appears “undercoded” and “illegible” within the history of photography, unable to account for the condition of working-class culture and representation. For Sekula, the dominant myth of Southern California, as an imagined landscape of perpetual leisure, obscures the conditions of actual exploitive labor and seemingly unending work in the region: “Life is easy”, Sekula writes, “or at least easier than elsewhere, how inappropriate to suggest that it is hard” (ibid., p. 171).

In many ways, Sekula’s argument drew upon an old tenet of the social art history—a concern with the constraints or blind spots of artistic labor and its relation to its public, as much as an inquiry into what permits the conditions of production (or one’s vision) in the first place. In this tradition Sekula’s remarks are meant to be read as rhetorical; social documentary is not impossible, per se, but the genre is imagined as constrained by a series of limits, wherein each limit is imagined as a barrier—a barrier that has been historically and periodically superseded and overcome.18

For Sekula, writing in the late 1990s, the persistence of documentary in Southern California occurred only “marginally and cryptically” as a dead genre, elsewhere understood, in his words, as a type of “zombie realism”. The zombie form, in this instance, was a documentary mode “where the living speak only through the dead, or through those states of being that fall between life and death”, to quote Sekula (2015a, p. 180). His examples are few and far between: Cartier-Bresson’s photographs of the unemployed in Pershing Square (1947), Ruscha’s Real Estate Opportunities (1970), and Maya Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon (1943). For Sekula, these three figures represent three distinctive documentary “undercoders” of Los Angeles that activate or play with the particular afterlives of the image. Hernandez, to my mind, represents the fourth (Figure 23).

Figure 23.

Anthony Hernandez Public Use Areas # 27 (1980), © Anthony Hernandez.

In a posthumously published interview with Edward Dimendberg for the catalogue Facing the Music, Sekula argues that photographic historians need to uncover a forgotten period of social documentary in Los Angeles reaching from the 1930s through to the early 1970s. In this tradition of recovery, Sekula recognizes the work of his colleague at CalArts, Thom Andersen—whose widely acclaimed film Los Angeles Plays Itself (2004) contributed to the revaluation of the films of Charles Burnett, Billy Woodberry and other members of the Los Angeles Rebellion. “Partly this is a question of cultural retrieval”, Sekula states, “but I think the current drive to re-center the city on part of its elites calls for timely and dialectical counter argument. Just as people were evicted, and buildings demolished, so also genres have been discredited and neglected. Los Angeles becomes the graveyard of documentary” (Sekula 2015b, p. 199). What was required in this environment of eviction, displacement, and historical forgetting was not only a type of “cultural retrieval”—a rethinking of works and projects that had been obscured and neglected throughout history (Hernandez’s for instance)—but also a dialectical “counter-argument” that pushed up against the social and political forces of enclosure, eviction, and displacement that reverberated throughout the geography and cultural ecology of Los Angeles (ibid.).

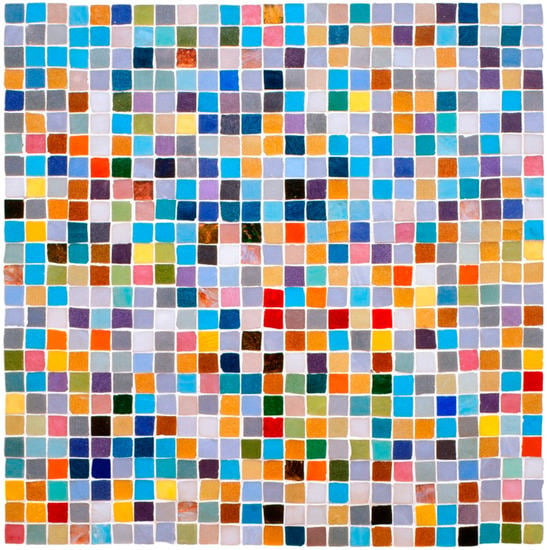

Indeed, five years before Sekula included Hernandez in his exhibition Facing the Music, the photographer was asked to write a short essay for Hernandez’s photobook, Waiting for Los Angeles (2000). This project was dedicated to the surfaces of urban Los Angeles—walls, facades, windows, signs. In this series, Hernandez prioritizes the architectural details of these surfaces so that both the “abstract” details and the abstraction of labor are emphasized. The cover image, for instance, presents a grid of square ceramic tiles in a dizzying array of colors (Figure 24). This diverse palette includes lavender, ochre, seafoam green, grey, fuschia, and many other colors harder to name and classify. In his essay on the artist, Sekula notes how the ceramic-grid tiling reminds him of the erratic rhythms of Mondrian—but a Mondrian intermixed with Seurat—and thus, a work that unexpectedly transits into the realm of landscape (with “drowsy eyelashes diffracting bright summer light”) (Sekula 2002, p. 5). Sekula’s comparison emphasizes the “objectness” of both Mondrian and Seurat, especially the pure material facticity of abstraction, and by implication the realist impulse, over and above its assumption of modernist autonomy. Although the form of the grid is structured and overdetermined as a “readymade” form, what Hernandez finds, however, is always subject to contingency. Sekula argues that these “abstract” qualities have an implicit social significance to the built environment of Los Angeles, similar to the cigarette butts and trash in the photographs featured in Landscapes for the Homeless, but also revisited in his series Waiting for Los Angeles. “The anonymous tile setter, working away on a government facade on Gage Avenue in South Central Los Angeles”, Sekula states, “got something right about the false cheer of the (city’s) smoggy atmosphere”.

Figure 24.

Anthony Hernandez, Waiting in Line #3 (1996), © Anthony Hernandez.

While Sekula was drafting his essay on Hernandez’s work, he visited the Los Angeles County Department of Social Services building where the wall was located. However, the mural was nowhere to be found. Even the veteran security officer had forgotten its existence. The polychromatic wall was covered over with glossy, battleship-grey, enamel anti-graffiti paint.

Even though these surfaces of the city are capable of indexing a social texture, these same “surfaces” can be read in contradictory fashion: more often than not Hernandez foregrounds an architectural form—wall, door, window—which operates as a barrier to perception and social interaction. The wall, door, or gate quite literally blocks the movement of one’s eyes and body much in the same way as a number of photographs from Landscapes for the Homeless foreground opacity through walls of cardboard and other barriers to perception. In the context of Waiting for Los Angeles, however, the wall is often emphasized as an extension of the activity of separation and enclosure. Hernandez’s work underscores how these forms of separation are experienced on registers that are both economic and phenomenological.

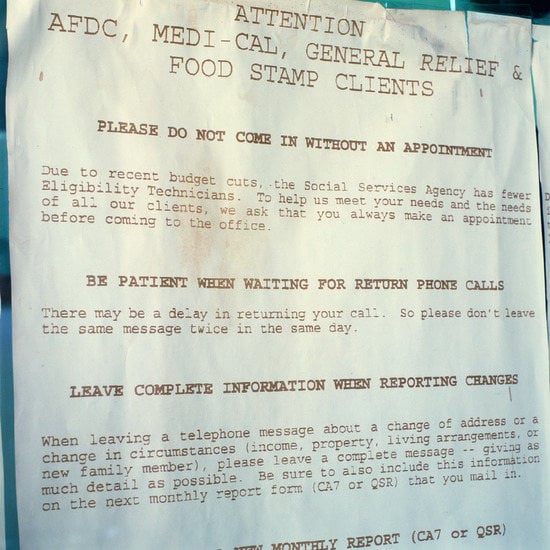

As the historian Peter Linebaugh has repeatedly argued, the process of enclosure, through acts of “closing off and fencing in”, operates as the central current of modern capitalism (Linebaugh 2014, p. I). “Enclosure, like capital”, Linebaugh writes, “is a term that is physically precise, even technical (hedge, fence, wall), and expressive of concepts of unfreedom (incarceration, imprisonment, immurement)” (emphasis in the original).19 Similar to eviction and displacement, the wall is a form of dispossession. Hernandez’s underscores this blockage, textually, in a photograph of a multi-lingual notice posted on the Social Service Agency wall, which notifies its “clients” not to cross the building’s threshold without an appointment (Figure 25). “Due to recent budget cuts”, the notice states, “the Social Services Agency has fewer Eligibility Technicians. To help us meet your needs and the needs of all our clients, we ask that you always make an appointment before coming to the office”. Indeed, one of the more poignant photographs from the series shows a web of diamond metal fencing tightly squished up against a number of palms and other plant life (Figure 26).

Figure 25.

Anthony Hernandez, Waiting in Line #22 (1996), © Anthony Hernandez.

Figure 26.

Anthony Hernandez, After L.A. # 39 (1938), © Anthony Hernandez.

The central activity in these spaces, Sekula argues, is the enforced suspension of one’s activity. In this sense, we are closer to grasping the unique material and temporal shape of these photographs, indexed as a condition of “waiting”, which is of course cited in Hernandez’s title, but also felt throughout his photographic work from the 1970s. Sekula states:

Hernandez’s title suggests something more about his series of pictures of welfare offices, something about the life-world of those who wait. Here are veiled propositions that attentive esthetic impulses can emerge from waiting, that waiting in line can lead one to step out of line.

This activity of “waiting” is also what photographers in Los Angeles do. In Sekula’s frame, “waiting” can also be read as an extension of the activity of “walking”—an activity which no Angelino in the city seems to do. The project’s emphasis on the activity of “waiting” was a return to a topic that the photographer had explored in detail on the streets and sidewalks of Los Angeles in the late 1970s all the way through the 1990s, in his series Landscapes for the Homeless.

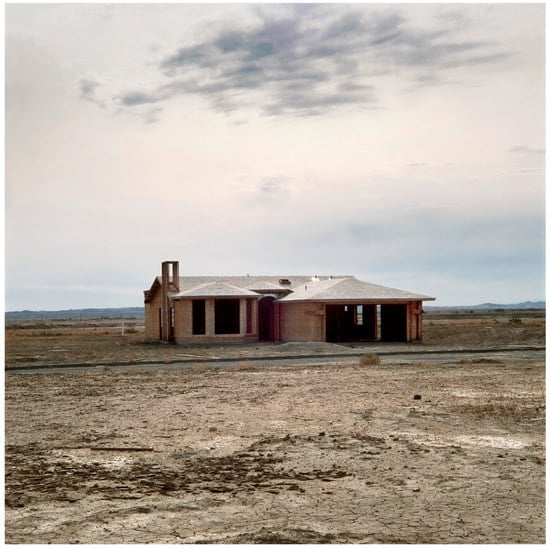

Hernandez’s emphasis on this condition of suspension or abandonment—a peculiar suspension of this street level activity—is reworked in his most recent, and arguably bleakest, photographic series, Discarded (2012)—a project that documented the failed and vacated housing developments devastated by the 2008 economic crash (Figure 27). In Discarded, Hernandez represents these developments as half-built, boarded up, or smashed-in. Unlike in his photographs of bus shelters and homeless camps, it is increasingly difficult to claim that Hernandez’s camera appears firmly planted on “the street”, considering many of the developments, with their boulevards, sidewalks, and roads, appear as extensions of the surrounding desert.

Figure 27.

Anthony Hernandez, Discarded #3 (2012), © Anthony Hernandez.

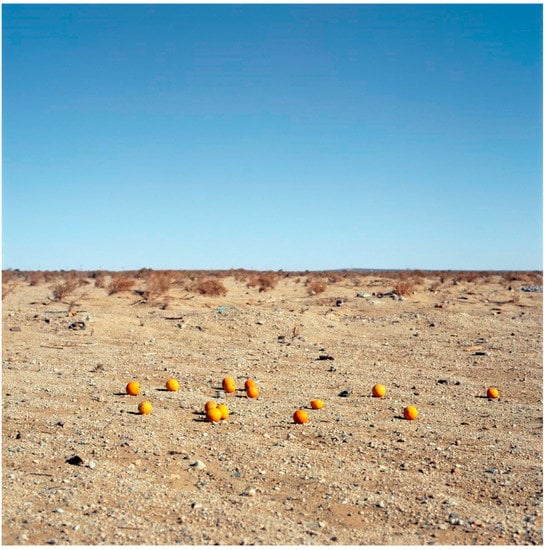

In two photographs from the series, the planted palms scattered across the horizon seem unable to grow any higher, their heads dramatically chopped off at the stem (Figure 28 and Figure 29). In an analogous photograph, a pile of brightly lit oranges left to rot on the barren desert ground stand in dramatic contrast to the glowing blue horizon pictured in the distance (Figure 30).

Figure 28.

Anthony Hernandez, Discarded #12 (2013), © Anthony Hernandez.

Figure 29.

Anthony Hernandez, Discarded #42 (2012), © Anthony Hernandez.

Figure 30.

Anthony Hernandez, Discarded #9 (2013), © Anthony Hernandez.

These three symbols of Californian wealth and prosperity—mansions, palm trees, and oranges—find their negative inverse in Hernandez’s series. Unlike his photographs in Landscapes for the Homeless, which often look down in deep focus at rot and decay, the oranges shown in Discarded #9 are approached from a distance (Figure 30). Hernandez’s oranges have not yet succumbed to mold or rot, and yet we sense that this decay is imminent and entirely present in their strange position—a disaster that appears in the middle-distance and threatens to disperse across the horizon.

On the topic of oranges, it is interesting to return here to Sekula’s last published interview, in which he directly addressed this particular symbol of excessive wealth and prosperity in California. In conversation with Edward Dimenberg, the artist recalls how in John Fante’s depression-era Los Angeles novel, Ask the Dust (1939), the main protagonist, Arturo Bandini, survives only by eating the oranges provided by a Japanese fruit monger, which leads Sekula to conclude that a “sickening surplus toxifies the very symbol of California’s invigorating bounty”.20 The excessive bounty of oranges indexes an actual form of dispossession that lies at the heart of this image. In this mode, photography is tasked with the responsibility to call attention to the modes of dispossession, eviction, and enclosure that actively contribute to this toxic surplus.

Coincidentally, this “toxic surplus of oranges” appears as an image that Hernandez had worked through his earlier work. One photograph not included in either of the editions of Landscapes for the Homeless is an image of a pile of discarded objects, comprising bruised oranges, innumerable lighters, a purse, a half-used box of baking soda, and a crinkled bible that the photographer found piled together outside the wall of a newly constructed apartment development in Los Angeles (Figure 31).21

Figure 31.

Anthony Hernandez, Landscapes for the Homeless (sketch) (1992), © Anthony Hernandez.

The inverse of this image of Californian excess is found in an orange-tinted interior littered with dust, dirt, and shattered glass in Hernandez’s series, Discarded (Figure 32). The afterglow of a Californian sunset permeates the entire texture of the room, as if to suggest that the interior was processed through its opposite, the street. The image distills a blast of light, almost akin to the destructive effect of a bomb that evacuates any presence. Hernandez finally pictures an interior scene, yet the image, similar to many of his photographs, remains without a figure or inhabitant. In contrast to many of the photographs encountered in Landscapes for the Homeless, where the contents of the interior are scattered throughout the far reaches of the city, Hernandez has brought the street within the interior. And yet, similar to many of the photographs in Landscapes for the Homeless, the ground features the same detritus to which Hernandez’s camera is persistently drawn. Composed of dirt, broken glass, and other “discarded” material, the photograph captures a scene without lived value, a scene of deprivation and dispossession. In this mode, the photograph reveals the new geography of modern America—vacant homes evicted of people. Los Angeles: the city of the evicted.

Figure 32.

Anthony Hernandez, Discarded #50 (2014), © Anthony Hernandez.

Funding

This research was funded by the Terra Foundation for American Art Post-Doctoral Teaching Fellowship.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the editor of this Special Issue, Stephanie Schwartz, for the invitation to contribute to this volume. Along the way, Anthony Hernandez has been generous with his time. I thank him for the use of his photographs. In addition, the essay has benefited from the careful reading and incisive criticism of Larne Abse Gogarty, Afonso Dias Ramos, Alexandra Fraser, Amy Kazymerchyk, Rye Holmboe, Bella Ritchie, and Ying Sze Pek. I am grateful for their friendship and encouragement.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Badger, Gerry. 2007. Waiting, Sitting, Fishing, Some Automobiles: Los Angeles. Bethesda: Loosestrife Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, Roland. 1953. Writing Degree Zero. Translated by Annette Lavers, and Colin Smith. London: Jonathan Cape. [Google Scholar]

- Campany, David. 2010. Anonymes: Unnamed America in Photography and Film. Paris: Le Bal. [Google Scholar]

- Campany, David. 2013. Walker Evans: The Magazine Work. Göttingen: Steidl Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Mike. 2000. Magical Urbanism: Latinos Reinvent the US Big City. London: Verso Books. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Mike. 2009. City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles. New York: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Flusty, Steven. 1994. Building Paranoia: The Proliferation of Interdictory Space and the Erosion of Spatial Justice. Los Angeles: Los Angeles Forum for Architecture and Urban Design. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, Anthony. 2016. Interview with Anthony Hernandez. Email, April 28. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, Anthony, and Lewis Baltz. 1995. Forever Homeless: A Dialogue. In Landscapes for the Homeless. Hannover: Sprengel Museum Hannover. [Google Scholar]

- Linebaugh, Peter. 2014. Stop Thief!: The Commons, Enclosures, and Resistance. Oakland: PM Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole, Erin. 2016. A Very Hard Look. In Anthony Hernandez. San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art with D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, Fred R. 1973. Anthony Hernandez. In Untitled. Carmel: Friends of Photography. [Google Scholar]

- Plagens, Peter. 1972. Los Angeles: The Ecology of Evil. Artforum 11. Available online: https://www.artforum.com/print/197210/los-angeles-the-ecology-of-evil-36172 (accessed on 17 May 2019).

- Ribalta, Jorge. 2011. The Worker Photography Movement, 1926–1939: Essays and Documents. Madrid: Museu Centro de Arte Reina Sofia. [Google Scholar]

- Risberg, Debra, and Allan Sekula. 1999. Imaginary Economies: An Interview with Allan Sekula. In Dismal Science: Photo Works 1972–1996. Normal: University Galleries of Illinois State University. [Google Scholar]

- Sartre, Jean-Paul. 2004. Critique of Dialectical Reason. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Schama, Simon. 1997. The Embarrassment of Riches: An Interpretation of Dutch Culture in the Golden Age. London: Vintage. [Google Scholar]

- Sekula, Allan. 1984. School is a Factory. In Photography Against the Grain: Essays and Photo Works 1973–1983. Nova Scotia: The Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design. [Google Scholar]

- Sekula, Allan. 1999. Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary (Notes on the Politics of Representation). In Dismal Science: Photo Works 1972–1996. Normal: University Galleries. [Google Scholar]

- Sekula, Allan. 2002. Waiting for Los Angeles. In Waiting for Los Angeles. Tucson: Nazareli Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sekula, Allan. 2015a. Los Angeles: The Graveyard of Documentary. In Facing the Music: Documenting Walt Disney Concert Hall and the Redevelopment of Downtown Los Angeles. Los Angeles: East of Borneo Books, p. 175. [Google Scholar]

- Sekula, Allan. 2015b. Interview with Allan Sekula by Edward Dimendberg. In Facing the Music: Documenting Walt Disney Concert Hall and the Redevelopment of Downtown Los Angeles. New York: Distributed Art Publishers, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Sekula, Allan, and Jack Tchen. 2004. Interview with Allan Sekula: Los Angeles, California, October 26, 2002. International Labor and Working-Class History: New Approaches to Global Labor History 66: 155–56. [Google Scholar]

- Soja, Edward. 2014. When It First Came Together in Los Angeles (1965–1992). In My Los Angeles: Form Urban Restructuring to Regional Urbanization. Berkeley: University California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon-Godeau, Abigail. 2017a. Introduction. In Photography after Photography: Gender, Genre, History. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon-Godeau, Abigail. 2017b. Harry Callahan: Gender, Genre and Street Photography. In Photography after Photography: Gender, Genre, History. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stimson, Blake. 2009. The Photographic Comportment of Bernd and Hilla Becher. In The Pivot of the World. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, Jeff. 2009. Introduction. In Anthony Hernandez. Vancouver: Vancouver Art Gallery. [Google Scholar]

- Witt, Andrew. 2018. Ask the Dust. Published in American Suburb X (November 24, 2018). Available online: https://www.americansuburbx.com/2018/11/allan-sekula-ask-the-dust.html (accessed on 28 May 2019).

| 1 | Solomon-Godeau reminds us that the art of photographic capture is never innocent, never an act of neutral bystanding. “What seems to be always at stake in the invention of this genre is a certain subject position for the photographer. I refer here to the art photographer, who in this context is producing not landscape, nude, still life, or abstraction—staple subjects of art photography that, by definition, declare their status as art. Instead of such duly consecrated aesthetic motifs, the photographer poaches, so to speak, on the territory of the photojournalist, the documentarian, the magazine photographer, and the commercial purveyor of urban views.” See (Solomon-Godeau 2017b, pp. 88, 93). |

| 2 | Sekula and Rosler both anticipated Solomon-Godeau’s critique of ‘street photography’. “The subjective aspect of liberal aesthetics”, Sekula wrote in 1978, “is compassion rather than collective struggle. Pity mediated by an appreciation of great art, supplants political understanding.” See (Sekula 1999, pp. 53–77). One could even question the photographer’s empathetic or sentimental identification with their sitter, Solomon-Godeau argues, the visual evidence would unequivocally suggest otherwise. |

| 3 | As Solomon-Godeau argues, the gendered conventions of street photography are equally as suspect: a project dictated by the masculinist prerogative of active looking, the predatory and possessive optics of public space (coupled with the relative vulnerability of women in that space), and the aggressive nature of male photographers picturing unwitting (female) subjects—political and ethical aspects that male photographs have rarely acknowledged. See (Solomon-Godeau 2017b, p. 85). |

| 4 | Although Baltz does not explicitly reference Roland Barthes’ Writing Degree Zero (1953), in which the French critic celebrated a new genre of ‘colorless’ and ‘styleless’ writing (“freed from all bondage to a pre-ordained state of language.” See (Barthes 1953). |

| 5 | Baltz makes this argument (rather hyperbolically) in conversation with Hernandez: “Homelessness as a contemporary phenomenon probably began in California in the late Sixties when then Governor Ronald Reagan closed the state mental institutions and turned the mad loose in the streets (a condition Baudrillard likened to the breaking of a Seal of the Apocalypse). Not really the dangerously mad, just the weak, the helpless and the incompetent” (Hernandez and Baltz 1995, p. 12). |

| 6 | After six years in East Los Angeles his family moved into a house behind his grandparents’ place in Boyle Heights (a neighborhood just east of Downtown). |

| 7 | As Erin O’Toole writes in her recent catalogue on the artist, Hernandez’s interest in photography was accidental. His best friend from high school, Albert Cordova, found a basic photography manual published by the navy in the bathroom of ELAC and gave it Hernandez. See (O’Toole 2016, pp. 14–16). |

| 8 | The portraits of the pedestrians of Los Angeles resemble in many ways the “portraits” that Walker Evans produced for Fortune magazine in the 1940s—a practice distinguished by its staging in public, on the street, but also reliant on a series of technical constraints, aleatory encounters and readymade forms. Three particular series come to mind: Evans’ In Bridgeport’s War Factories (1941), Labor Anonymous (1946) and Chicago: A Camera Exploration (1947). Chicago: A Camera Exploration (1947) was republished in U.S. Camera Annual as “Walker Evans: Corner of State and Randolph Streets”). For full-page reproductions of Evans’s magazine work, see (Campany 2013). |

| 9 | This act of intervention and interruption is doubled in the exhibition of Untitled Slide Sequence where Sekula’s twenty-five black-and-white transparencies are projected at thirteen-second intervals propelled by the gaps distinctive of slide carousel projectors—a technology, Sekula argued, which mimicked the simple mechanical action of a bottling machine on an assembly line (Risberg and Sekula 1999, p. 240). |

| 10 | Erin O’Toole makes this observation in her SFMOMA essay. See (O’Toole 2016, p. 18). |

| 11 | Notably, from 1965 to 1983, Los Angeles distinguished itself as the financial hub of the United States as well as the central gateway to the Pacific Rim. See (Soja 2014, p. 43). |

| 12 | The re-branding of Los Angeles by Bradley and his urban coalition was founded partially on the attempt to counter the reputation of Los Angeles as a “cowtown populated by wannabes and hillbillies.” According to Mike Davis, Mayor Bradley was successfully able to integrate foreign capital into the “top rungs” of his urban coalition: Bradley was, Davis writes, “unflagging in his promotion of the movement of free capital across the Pacific while denouncing critics of Japanese power as ‘racists’. His administration has kept landing fees at LAX amongst the lowest in the world, vastly expanded port facilities, given special zoning exemptions and development-right subsidies to foreign investors.” See (Davis 2009, pp. 136–37). |

| 13 | For a similar set of photographic procedures in the work of Bernd and Hilla Becher, see (Stimson 2009, p. 146). |

| 14 | David Campany has recently written on the artist’s work in a short essay for a group exhibition titled, Anonymes: Unnamed America in Photography and Film. Campany argues that Hernandez’s subjects are posed in such a way that the viewer “cannot separate foreground from background, the anonymous subject from the anonymous space.” See (Campany 2010, p. 87). |

| 15 | In Jean-Paul Sartre’s Critique of Dialectical Reason (1960), the philosopher gives the example of people waiting for a bus as an illustration of the “practico-inert”, an inherited structure or activity that prohibits the freedom of an individual or a group. “These people—who may differ greatly in age, sex, class and social milieu”, Sartre writes when looking at a group standing at a bus stop, “realize, within the ordinariness of everyday life, the relation of isolation, of reciprocity and of unification (and massification) from outside which is characteristic of, for example, the residents of a big city in so far as they are united though not integrated through work, through struggle or through any other activity in an organized group common to them all.” Sartre observes a plurality of separations in this particular image. See (Sartre 2004). |

| 16 | “I suppose my sense of Los Angeles was of this space of multiple evictions”, Sekula expressed in an interview with Jack Tchen in the Fall of 2004. (Sekula and Tchen 2004). I address this history of eviction and photography in a short essay, see (Witt 2018). |

| 17 | Sekula’s argument runs, of course, in opposition to the most famous ‘street’ photographer of the city, Ed Ruscha. The artist’s Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966) was produced ‘on the move’, photographed from the seat of his car, as art historian Alexandra Schwartz has noted. In particular, in Every Building on the Sunset Strip, the artist used a motorized camera to photograph the strip from a moving pickup truck. See (Sekula 2015a, p. 175). |

| 18 | This line of argument has been continued, in different contexts, by theorist Jorge Ribalta, who has claimed that the critical documentary practices of the 1930s remained largely illegible and suppressed during the Cold War, a phenomenon that is related to how oppositional political formations, such as communism and socialism, were repressed in the latter half of the twentieth century. See (Ribalta 2011). |

| 19 | “In our time it has been an important interpretive idea for understanding neoliberalism, the historical suppression of women as in Silvia Federici, the carceral archipelago as in Michel Foucault’s great confinement, or capitalist amassment as in David Harvey’s accumulation by dispossession.” See (Linebaugh 2014, p. 142). |

| 20 | “I think Gehry’s aggressiveness as an architect is encoded in that manner. Despite sophisticated design software, no one seems to have calculated that Disney Hall’s complicated lenticular surfaces could momentarily blind bus drivers or elevate by twenty degrees the interior temperature in adjacent buildings. Los Angeles is a city of bright reflective surfaces, so let’s give people more. Let’s give people more oranges.” (Sekula 2015b, p. 197). |

| 21 | This image was sent to me by Hernandez via email, out of the blue on 24 April 2019. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).