Abstract

This article considers photographs of New York by two American radical groups, the revolutionary Workers Film and Photo League (WFPL) (1931–1936) and the ensuing Photo League (PL) (1936–1951), a less explicitly political concern, in relation to the adjacent historiographical contexts of street photography and documentary. I contest a historiographical tendency to invoke street photography as a recuperative model from the political basis of the groups, because such accounts tend to reduce WFPL’s work to ideologically motivated propaganda and obscure continuities between the two leagues. Using extensive primary sources, in particular the PL’s magazine Photo Notes, I propose that greater commonalities exist than the literature suggests. I argue that WFPL photographs are a specific form of street photography that engages with urban protest, and accordingly I examine the formal attributes of photographs by its principle photographer Leo Seltzer. Conversely, the PL’s ‘document’ projects, which examined areas such as Chelsea, the Lower East Side, and Harlem in depth, involved collaboration with community organizations that resulted in a form of neighborhood protest. I conclude that a museological framing of ‘street photography’ as the work of an individual artist does not satisfactorily encompass the radicalism of the PL’s complex documents about city neighborhoods.

Keywords:

street photography; documentary; neighborhood; protest; worker photography; propaganda; museum In the February 1938 issue of the Photo League’s bulletin Photo Notes, a brief notice informed that:

The newly formed Documentary Group announces that it has embarked on a large project, a document on Chelsea. With Consuelo Kanaga’s group working on “Neighborhoods of New York” and the Feature Group working on the Bowery, and Park Avenue, etc., a new slogan for the Photo League might be “We Cover New York”.1

The maxim ‘we cover New York’ conveys the extensive, in-depth analysis of these neighborhoods (also including the Lower East Side and Harlem) by the photographers of the Documentary and Feature Groups, an assemblage of teachers, such as Kanaga and Aaron Siskind, and student members of the Photo League (PL), which was a forum for documentary photography that provided training and exhibition space for young, typically working-class, photographers. Formed in 1936, the PL was an offshoot of the revolutionary Workers Film and Photo League (WFPL), but fostered a broadly radical, albeit non-aligned, form of social documentary. Nonetheless the PL fell victim to blacklisting by the House UnAmerican Activities Committee in 1948, wherein former member Angela Calomiris testified that the Communist sympathies of its revolutionary past persisted; and so it dwindled and expired in 1951.

‘We Cover New York’ is a strikingly less combative slogan than that of the WFPL, which asserted that ‘the camera is a weapon in the class struggle’ (Ward 2011, p. 334). The WFPL operated under the auspices of the Comintern-affiliated Workers International Relief from 1931 to 1936, making agitational films and photographs that witnessed demonstrations against lynching and Fascism, hunger marches, and scenes of hardship in New York and other cities, on behalf of the proletariat as evidence of class oppression to propagate the Communist movement. In 1934 the WFPL dropped ‘worker’ from its title in 1934 in an attempt to augment its appeal amongst fellow-travelers. The fragmentation of the (W) FPL between 1934–1936, beginning with the secession of a group of filmmakers to create Nykino, coincided with the dissolution of Workers International Relief in 1935. Untethered to the Communist movement, the PL shifted towards more sustained and elaborate projects that documented the city’s everyday life in neighborhood streets and tenements. With neither proletarian basis nor agenda, the work appears as slippage from activist militancy to passive coverage according to a generic social documentary model. It is unsurprising therefore that many members of the PL were shocked and confused by the blacklisting.

Yet, despite the PL’s eschewal of Communist invective, there were also important, yet seldom attended, continuities between these organizations. Indeed, the WFPL’s photographs (and film newsreels) involved a type of generative indexicality; as symbiotic witness and broadcast, they also covered New York by recording protests as a means of stimulating further civil unrest. In WFPL works, protests covered the city in crowds and placards, repurposing its thoroughfares as solely revolutionary spaces, siphoning metropolitan life into a sequence of sites of injustice and redress.2 The WFPL image is an instrumental and incidental representation of the modern metropolitan city as simply the impetus and locus for mobilized resistance, a contingent context rather than a place of aesthetic interest. For the WFPL the city was an arena of a class struggle that also included sites of industrial and agricultural labor conflict. The PL’s conception of the city was by contrast at once broader in remit and less ideologically determined, as evident in a Photo Notes bulletin that relayed how a ‘workshop in Documentary photography experimented with photographs of the city’s life; busy street corner, Manhattan side-street, men-at-work, city people’.3

This article does not rehearse the stories of the WFPL and the PL, as there are already several fine accounts available.4 Rather, I focus on the representation of city life in photographs by members of the WFPL and the PL in relation to ‘street photography’, and scrutinize historiographical claims that invoke the category. Such readings use ‘street photography’ to identify key photographers of the latter group with the mythic ‘bystander’, a model of a disinterested, typically covert and therefore detached, camera artist that has a particular museological valorization. In the catalogue to the Jewish Museum’s The Radical Camera exhibition of 2011, Mason Klein writes that the emergence of the PL witnessed a realignment from ‘worker photography’ to ‘street photography’—‘while the League may have initially emphasized a fairly narrow agenda of documentary work—largely a product of the 1930s and the international revolutionary Zeitgeist of the worker-photography movement—its real contributions are far more enmeshed in the period’s transition toward the experimentation and spontaneity that came from using a 35-mm camera in the street’ (Klein 2011, p. 15). I do not disagree with Klein’s narrative arc—the PL undeniably withdrew from propaganda towards a more semantically open documentary mode—but I suggest that ‘street photography’ becomes a problematic figure in assessing these images. I argue that this drive to incorporate the PL into what I term the ‘putative canon of street photography’ is predicated upon an institutional encoding that values the individual photographic artist, the flâneur with camera, in preference to the instrumental, interested production of the collective. Furthermore, the term ‘street photography’, in the above sense, does not sufficiently characterize the activist analysis of the neighborhood documentary projects any more than it does the WFPL’s output.

Klein writes that the PL’s street photography ‘fostered the sense of artistic “presentness” associated with the New York School’, thereby anticipating the roving cameras of Robert Frank, William Klein, Gary Winogrand, and Diane Arbus, which reached an apogee with the 1967 Museum of Modern Art show ‘New Documents’ (ibid, p. 15). His position is not unique in the literature on the PL. Mary Panzer (2011) describes PL members as pioneer street photographers, writing that ‘long before “street photography” had become a popular genre, or 35-millimeter cameras had become widely used, the League sent its students out into the world and asked them to come back with interesting pictures’. In Bystander: A History of Street Photography, Joel Meyerowitz and Colin Westerbeck qualified the politics of photographs by leading PL member and teacher Sid Grossman, one of the few stalwart leftists within the group:

Predictably, much of his work reflects the street shooter’s love of chance formalism and moments. The presence of such qualities not only in Grossman’s work, but in that of many others associated with the League, makes it clear that [Lewis] Hine’s love of street photography for its own sake was as important a component of his influence as his political idealism.(Westerbeck and Meyerowitz 1994, p. 250)

In authoring Bystander, Meyerwitz (himself a leading street photographer) and Westerbeck established the most influential model of street photography by characterizing the proponents of this mode as unseen witnesses of city life. They stated: ‘For the most part, however, the photographers in this book have tried to work without being noticed by their subjects. They have taken pictures of people who are going about their business unaware of the photographer’s presence. They have made candid pictures of everyday life in the street. That, at its core, is what street photography is’ (ibid., p. 34). This principle of ‘candid pictures of everyday life in the street’ is also ubiquitous in museological presentations of street photography. For instance, MoMA’s website defines it as ‘a type of photography nearly as old as the medium itself, in which photographers seek their subjects on the streets and in public places, aiming to capture candid pictures of people and moments of everyday life’.5 Similarly, a display at Tate Britain informs that: ‘Street Photography presents candid depictions of everyday life in the streets, with engaging images that often tell a story that goes beyond the moment captured on film. Whether capturing architecture, people in passing, odd details or intriguing signage, scenes are unmanipulated, with subjects not necessarily aware of the photograph being taken’.6

The unseen witness trope derives from Henri Cartier-Bresson’s (1952) term ‘images à la sauvette’ (‘images on the sly’). Gilles Mora (1998, p. 186) reiterates the centrality of Cartier-Bresson when stating that ‘street photographers pursue the fleeting instant, photographing their models either openly or surreptitiously, as casual passerby or as systematic observers’. Cartier-Bresson’s feted oeuvre balanced photojournalism (he was a founder of Magnum Photos) with the more associative, even uncanny, attributes of Surrealist urban photography, most notably the works of Brassaï and Jacques-André Boiffard (see Walker 2002). There is an allusion to the poetics of automatism in Westerbeck and Meyerowitz’s (1994, p. 35) statement that ‘street photographs have an imaginative life all their own, one that sometimes seems quite independent of whatever intentions the photographer may have had’. The authors allow that ‘the tradition of street photography is a diffuse, fragmented, intermittent one’ (ibid., p. 35). The numerous photographers in Bystander are international and derived from across photography’s history. However, Cartier-Bresson’s work is paramount—a double-spread of ‘Seville, 1932’ opens a suite of representative images (five of the twenty are by Cartier-Bresson) by important exemplars that also includes photographs by Helen Levitt, André Kertész, Eugène Atget, Walker Evans, and William Klein, as well as the lesser known Maurice Bucquet and Charles J. van Schaick. This is the basis of the ‘putative canon of street photography’—the magical urban documentary style of Cartier-Bresson inflected in works from before and during his long career (he died a decade after the publication of Bystander).

If Cartier-Bresson is the lodestar of Bystander, then in the history of American photography the paradigm figure is the Swiss-born Robert Frank. Frank’s photo-book The Americans (1959) is an opaque and gnomic selection of photographs that he made during a Guggenheim funded road trip across the country. In the introduction, Jack Kerouac (2008) penned an evocative tribute: ‘Robert Frank, Swiss, unobtrusive, nice, with that little camera that he raises and snaps with one hand he sucked a sad poem right out of America on film, taking rank among the tragic poets of the world’. Jonathan Green (1984, p. 83) locates the formula of street photography in Frank’s perambulations: ‘he was the archetypal stranger, the carefully observant onlooker’. Moreover, he was ‘bound neither by political nor visual constraints’ (ibid.). As such, Frank’s aesthetic necessitated eschewal of agenda. In the exhibition Open City: Street Photographs Since 1950, Russell Ferguson (2001, p. 9) wrote that ‘Frank’s very unwillingness to put his work in the service of a specific agenda that enraged many of his critics’ distinguished him from ‘the “humanist” photography of the pre-war years [which] began to be seen as merely sentimental, as artists increasingly found themselves at an apparently unbridgeable distance from the societies in which they lived’. Open City is, in effect, a rich and diverse rendition that presents street photography as after Frank—ensuing but also influenced by the photographer. As Philip Brookman observed in the Tate Modern catalogue Exposed: Voyeurism, Surveillance, and the Camera, Frank ‘…subsequently inspired a new generation of artists, not only for their astute visual power, complex narrative structure, and pointed interrogation of authenticity and illusion in the culture, but also because they told a personal story. He had defined a new sort of street photography, one that oscillated between voyeurism and the inside view’ (Brookman 2010, p. 219). This positioning of Frank as the orchestrator of a step change in American photography derives from John Szarkowski’s 1967 MoMA show ‘New Documents’:

In the past decade a new generation of photographers has redirected the technique and aesthetic of documentary photography to more personal ends. Their aim has been not to reform life but to know it, not to persuade but to understand. The world, in spite of its terrors, is approached as the ultimate source of wonder and fascination, no less precious for being irrational and incoherent.7

Therefore, street photography is a museological signifier of an aesthetic that conflates the unseen witness with the poet of the camera, according to terms elaborated by Szarkowski and adapted by Meyerowitz and Westerbeck.

I do not suggest that the ‘personal documentary’ discourse of street photography necessarily marks an evisceration of politics—Blake Stimson’s The Pivot of the World: Photography and Its Nation, for example, offers a nuanced reading of Frank’s The Americans as both a ‘window’ and ‘mirror’ ‘representing something like a social totality’ (Stimson 2006, p. 114). Rather, in Klein’s presentation street photography becomes a means for elevating the PL as a bona fide forum for prototypical ‘new documents’ in distinction from the WFPL’s political cant. He argues that a mature personal vision in Sid Grossman’s 1950s photographs:

Characterized part of the legacy of the Photo League—the highly subjectivized, poetic renderings of social impressions that define the work of the New York School. The transmutation of the documentary mode into an experimental, personal vision, a poetic sequence of documentary images, sees subjective efflorescence in Grossman’s late Provincetown work and reaches its transcendence in Robert Frank’s book The Americans (1958).(Klein 2011, p. 27)

Yet, establishing this through-line from Grossman to Frank risks diminishing the foundation of the PL as a collective formation, albeit one that was fluid, variegated, and in important ways experimental. As I shall establish, the veneration of a subjective vision comes at the expense of the powerful collaborative group practice of neighborhood documentary projects.

In one respect, this reframing was validated by the account by one pivotal PL member. Aaron Siskind: Towards a Personal Vision, 1935–1955 is a 1994 collection of writings and photographs that lionizes his gradual abandonment of social documentary and eventual exploration of photographic abstraction. Having joined the WFPL around 1932, Siskind was the key link between both phases, yet was truculent about the former group’s politics. As he recalled in 1962, the political basis of the WFPL was always a secondary factor in his involvement:

I was interested in this sort of social documentation and I happened to wander into the [WFPL] once, and I saw some pictures and I liked them. They were very moving to me, and so I joined […] Then, after I was there a while […] we began to do these documentary things, I left the [WFPL] after I was there for a few years. I left for certain personal reasons, ideology reasons. Later on, I rejoined on the condition that they would not involve me in any organizational work, that I would just be involved in what we called “production”.(Stephany 1994, p. 41)

He also remembered that the WFPL filtered images according to political remit: ‘Our activity was strongly directed; we focused sometimes on beggars and on poor living conditions. Sometimes we attempted to show the nobility of the workers. We were also responsible to the political bureau for our photographs and some were even excluded from the [WFPL]’ (Gautrand 1978, p. 64). To be sure, hostility to ideological anchorage was one of the key points of divergence in the PL, as evident in a letter to Eliot Elisofon from Beatrice Kosofksy complaining that ‘a batch of our pictures were found at the Daily Worker office’ (and in the ‘Visual Education committee upstairs’), and therefore the Feature Group had removed its photos from the PL file.8

If there were tensions about politics within the PL and the latter phase witnessed a shift to a mode that for some commentators anticipated canonical street photography, it is worth exploring the extent to which the WFPL works equated street photographs. The principle photographer and film cameraman of the WFPL was Leo Seltzer, who retrospectively critiqued the function of photography in the PL, because its ‘membership and activities were much different than those of the [WFPL]. [PL] members were more interested in documentary (still) photography as an art form and were involved in pictorializing aspects of the human condition. The [WFPL], on the other hand, operated mainly in film production and distribution’ (Seltzer 1988, p. 10). As Seltzer noted, it is important to remember that film was its priority and still photography was an adjunct. A film critic, Harry Alan Potamkin, wrote the League’s manifesto, which appeared in Workers Theatre in July 1931, avowing to counter the ‘part the movie plays as a weapon of reaction’ (Potamkin [1931] 1977, p. 5). The WFPL’s films and photographs presented, as Sam Brody explained in the Daily Worker, ‘the view point of the marchers themselves. Whereas the capitalist cameramen who followed the marchers all the way down to Washington were constantly on the lookout for sensational material which would distort the character of the march in the eyes of the masses, our worker cameramen, working with small hand-cameras that permit unrestricted mobility, succeeded in recording incidents that show the fiendish brutality of the police towards the marchers’ (quoted in Campbell 1977). The majority of the films and photographs represent mass demonstrations and brutal police responses from the perspective of the worker in the middle of the crowd, unlike the press photographers who generally observed events from behind police lines or from a safe distance. Seltzer recalled that: ‘The things that I shot were shot from the point of view of a person who participated in the activity rather than, like the commercial newsreel cameramen had their cameras mounted on a truck or building or on a tree, and they had a telephoto lens, and everything was from the same objective point of view’.9 The film Hunger 1932 includes commercial newsreel footage of the police arresting Seltzer at a Scottsboro demonstration, collapsing the distinction of documenter and document. As such, John Roberts’s (1998, p. 92) appellation of ‘hit and run tactics’ to describe Seltzer’s modus operandi is apposite.

The WFPL’s main task was recording and consequently advancing protests from the worker’s perspective as ciphers of solidarity to chronicle and recruit, with a secondary function of raising funds and the group’s profile by selling images to mainstream media. Published in leftist organs such as New Masses, Daily Worker, and Labor Defender, as well as the liberal Survey Graphic, the photographs of protests were interested witnesses to specific events, representing the perspective of the protestors to counteract official media, but were also generative, performing as protesting agents. The placards of protestors act as built-in captions, anchoring the image’s message to the depicted crowd, so that the photograph of the event extends the protest through media dissemination, with a view to its multiplication, photographically and thereby politically. In these pictures, the city is an arena of action, a space for the fomenting crowd and the setting of injustices. The individual photographer’s interpretation of the city in its normal activities is negligible—the city is simply symptom and stage for redress. In a sense, the worker photographer was the anti-flâneur, and did not drift amidst the multitude detached by a membrane of disinterest, but was intractable from the crowd, being there to witness it from within, and to cultivate it further through media dissemination. In this respect, Seltzer was the antithesis of the ‘bystander’. The WFPL photographer represented the crowd in two senses—as representing witness and representative participant—and therefore eradicated the distinction of subject and object in favor of a collective gesture of protest that served to reproduce proletarian consciousness.

The WFPL argued that proletarian photography was formally and thematically as well as ideologically distinct from ‘bourgeois photography’. In opposing the perceived distortion of events by bourgeois media, the WFPL applied a direct form of direct documentation that aligned the camera eye with the unadorned proletarian viewpoint, coupled with a suspicion of aesthetic embellishments. The July 1930 issue of Labor Defender detailed an exhibition of the Labor Defender Photo Group, a forerunner of the WFPL, stressing that ‘the chief value of the group is that with it the photo is not an ornament. It is something to be used as a propaganda weapon in the daily struggles of the workers’.10 In New Masses in February 1930, Frances Strauss admonished Californian comrades for ‘relaxing under a more gentle climate’ which led them deviate from propaganda by photographing ‘water, storm, the changing seasons of the year, nature in its variety of moods. One of the photographers even probes abstractions with photos called “line-study”, “design”, and “still life”’ (Strauss 1930, p. 20). By contrast, in the Daily Worker Brody asserted the proletarian basis of the 1933 WFPL photography exhibition ‘America Today’, which ‘breathes with the fires of workers’ struggles and makes pink-ribbon photographic salon displays look like the last stage of pernicious anemia’ (cited in Campbell 1977, p. 96).

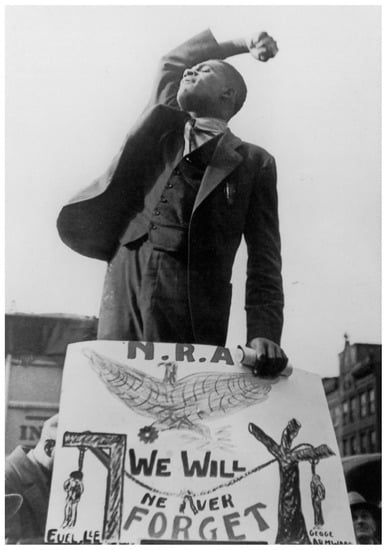

If disinterested representations of the city’s street life had no place in worker photography, then, unlike some of the WFPL’s more literal films such as National Hunger March (1931), Seltzer’s images of orators, marchers, evictees, and the homeless are not merely partial records of protests but are, I argue, good photographs. One of Seltzer’s most striking pictures shows a Harlem street preacher at the stump, declaiming against lynching behind a rudimentary but incisive diagram showing bodies hanging on gallows and a tree astride the National Recovery Act’s blue eagle motif (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Leo Seltzer, ‘Speaker at Demonstration in Harlem, New York City’, 1933, gelatin silver print. © Leo Seltzer.

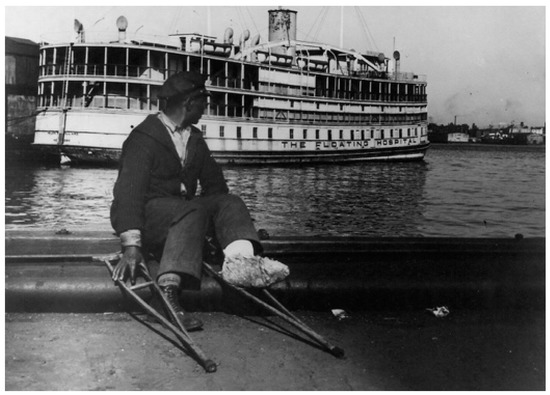

With one arm aloft, curving around his head into a fist, jacket flailing and face turned up, perhaps in anticipation of a grand utterance, the orator bears the aura of gravitas of a representational statue in a civic plaza, lending an ‘almost-staged’ quality to the photograph, offset by the less compositionally balanced, and therefore chance, placement of adjacent figures at ground level. In the case of a picture of a young African-American with a broken leg contemplatively propped on the dockside next to the East River Floating Hospital, the political content is less overt, though the implicit ‘hard times’ narrative, the potential context of display (the radical press), and its intended audience, fix it within the contiguity of Communist iconography (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Leo Seltzer, ‘Floating Hospital, East River Dock, New York City’, 1932, gelatin silver print. © Leo Seltzer.

These photographs demonstrate pictorial understanding in presenting direct polemics through clear composition and framing, and sensitivity to conveying political content through emotional narratives by capturing affecting facial expressions. The difference between WFPL and PL photographs is sometimes negligible. For instance, Seltzer’s 1933 photograph of children participating in an anti-fascist demonstration depicts an array of grinning and shouting kids processing waving placards with legends such as ‘Hands off Spain’, ‘Down with War and Fascism’, and ‘Hearst Wants War’, taken at an oblique angle from a crouch position, thereby creating an off-kilter line to the backdrop buildings that enhance the image’s dynamism (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Leo Seltzer, ‘Anti-War and Anti-Fascist Demonstration, New York City’, 1933, gelatin silver print. © Leo Seltzer.

Alexander Alland’s photograph of a 1938 student demonstration uses the same angle, albeit closer to the subject and therefore steeper, and is in essence an analogous work of protest photography.11

In this respect, though spare and tendentious, Seltzer’s WFPL works are not artless, and are more comparable to coeval street photographs by Walker Evans or Berenice Abbott than a historiographical bifurcation of the WFPL and the PL via street photography would allow.12 Indeed, in 1934 a WFPL fundraising event included an exhibition of photography by a collectively credited WFPL group (which likely included Seltzer’s photographs) alongside works by Abbott (who is also listed as the WFPL’s treasurer), WFPL member Ralph Steiner, fellow traveler Margaret Bourke-White, and the New York photographer and filmmaker Irving Browning. Like Evans’s and Abbott’s street photographs, Seltzer’s WFPL works portray a meaningful provisional encounter with urban citizens. The point of difference is the WFPL agenda—Seltzer sought out scenes of suffering and redress rather than exploring the city’s obscure and mysterious figures and forms. Interest in chance events and alignments is restricted to a predetermined narrative. If one characteristic of street photography is Cartier-Bresson’s ‘images à la sauvette’ model, then WFPL photographs are not candid but collaborative—the photographer is openly participating in as well as recording the crowd—yet the pictures do map onto the more common Anglicization of ‘the decisive moment’ in snapping the ephemeral protest (Cartier-Bresson 1952).

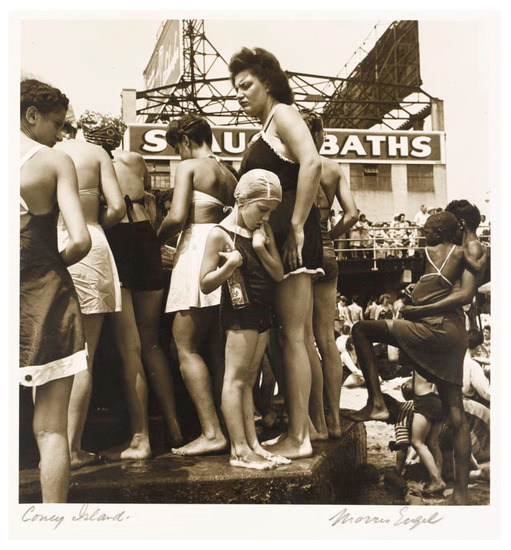

For Paul Strand, the PL’s most prestigious photographer, Cartier-Bresson ‘drives the best reportage beyond momentary interest’.13 He identified a correlate in junior PL member Morris Engel’s work, and wrote a tribute for the latter’s exhibition at the New School for Social Research in 1939:

Great particularity characterizes his most successful photographs. Inasmuch as generalization has been a characteristic weakness of documentary photography, this is a step forward. Engel sees his subjects very specifically and intensely. They are not types, but people in whom the quality of life they live is vivid—unforgettable. And by the quickness of his vision not of his shutter, he has been able to seize this expressiveness of the person as he or she moves down an avenue or street, amid the welter of city movement.14

For Strand, Engel’s achievement was to capture pregnant moments in the everyday life of New York’s working class, from the city streets to the beaches of Coney Island, and therefore to foster a coherent photographic vision (Figure 4). If Strand’s statement is redolent of the personal vision historiographically ascribed to street photography, then crucially he situated Engel within the PL’s auspices as ‘a center in which many young and talented photographers have received their training, where they have been able to get both technical knowledge as well as a contact with the historical development of photography as a medium of expression’ (ibid.). In Strand’s thinking, Engel was amongst the most notable of an emerging generation of photographers who ‘direct our thought and our understanding toward those urgent problems which America through the New Deal has only begun to face and solve’ (ibid.).

Figure 4.

Morris Engel, ‘Water Fountain, Coney Island’, 1938. Gelatin silver print. 19.4 cm × 18.7 cm. © 2019. Photo The Jewish Museum/Art Resource/Scala, Florence.

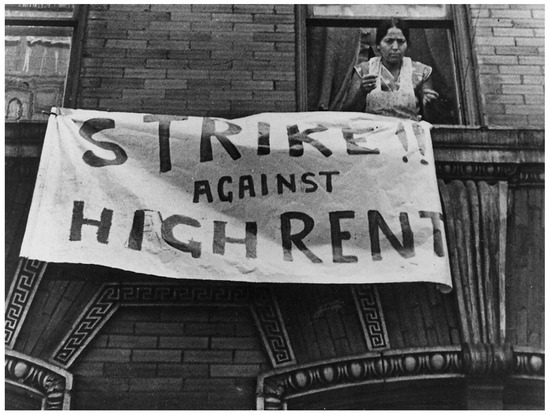

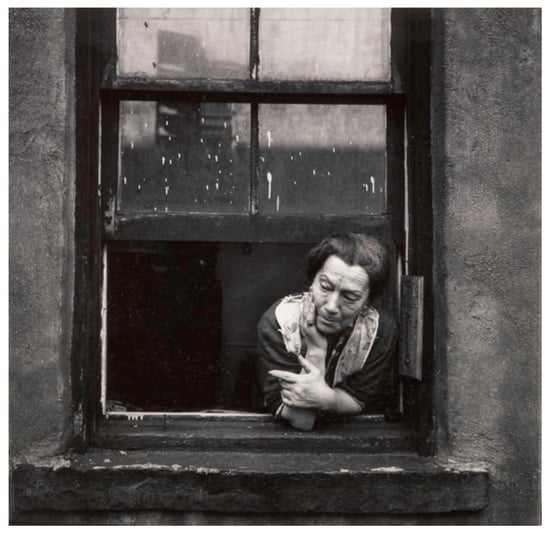

The designation of ‘an unusual capacity not only to see keenly and quickly, but also to integrate plastically what he sees’ could equally apply to Seltzer. To what extent are Seltzer’s subjects ‘types’? The homeless are stock figures of the homelessness crisis, certainly, but an evicted family has a particular expressivity. The legions of marchers are not just the expected young metropolitan radicals, but also include children and elderly protestors, both black and white. However, they are specifically protestors or victims whose plight necessarily engenders protest. An image by Seltzer of a woman in an Upper East Side window beneath a banner with the legend ‘Rent Strike’ 1933 (Figure 5) strongly resembles a Pitt Street Document photo from 1938 by Walter Rosenblum, entitled ‘Disturbed Woman, Pitt Street, New York’ (Figure 6), except that the latter is a picture of a citizen, unlike Seltzer’s protestor, though in its context of production and dissemination is a form of protest.

Figure 5.

Leo Seltzer, ‘Rent Strike, Upper East Side, New York City’, 1933, gelatin silver print. © Leo Seltzer.

Figure 6.

Walter Rosenblum, ‘Disturbed Woman, Pitt Street, New York’, 1938. Gelatin silver print, 19.7 cm × 21.6 cm. © 2019. Photo The Jewish Museum/Art Resource/Scala, Florence.

To position the latter picture as a street photograph requires the eschewal of the image’s contingency to the political aims of the Communist movement, and the emphasis of a personal vision, rather than an ideologically determined collective agenda.

For both the WFPL and the PL, the city was the locus of myriad injustices, as is evident in respective responses by groups to two World Fairs. In 1933, the Chicago branch of the WFPL contributed to a pamphlet published by Herman O. Duncan entitled Chicago on Parade that served as ‘a pictorial representation of certain phases of Chicago life which are to be seen alongside the much-publicized Century of Progress Exposition but from which the attention of the public is being diverted by our political and civic leaders’ (Duncan 1933). The photographs in Chicago on Parade, predominantly taken by Conrad Friberg (who also worked under the name C.O. Nelson for Labor Defender and Der Arbeiter fotograf), showed scenes of suffering and decay masked by the event’s publicity with bald captions about conditions juxtaposed with roseate quotes from the Fair’s President Dawes and Chicago’s Mayor Edward J. Kelly. An array of images of the unemployed sleeping rough in Grant Park, ‘Hoovervilles’ and ‘Rooseveltbergs’, tenements such as a ‘7-story dilapidated, firetrap’ that ‘is a refuge for a few of the thousands of evicted families’, bread lines, hunger marches, demonstrations against police violence, and strikes for higher wages depicted a city in turmoil, coupled with Duncan’s commentaries lambasting the narrative of progress (ibid., p. 7). A tableau of photographs of the West Tower of the World’s Fair Sky Ride taken from the perspective of the slums, with assorted crumbling buildings in the foreground, encapsulates the blunt message of the pamphlet.

Anticipating the New York World’s Fair in 1939, the PL announced ‘an exhibition of New York as YOU see it, as opposed to the way the picture postcards, guidebooks and the rotogravure sections “see” it. All photographers, amateur or professional, Brownie luggers or Contax carriers are invited. The name is unimportant, the picture is. They will be hung in many galleries, and the [PL] will see to it that they are viewed by many people’.15 There was a flurry of notices in Photo Notes outlining how the city’s most famous attractions for outsiders were merely anodyne platitudes: ‘Millions of New Yorkers have never visited the Statue of Liberty or the Empire State Building. Yet the two represent the nation’s picture of our metropolis. To New Yorkers the city means traffic cops and subways, slums and skyscrapers, night clubs and relief bureaus, libraries and jails’ (ibid.). Furthermore, the PL asked ‘will it be the real New York or just a guide book New York that doesn’t attempt to even scratch the surface of our great metropolis.’16 However, the expository ethos shared by the WFPL and PL in counteracting the ideological distortions of the respective Fairs diverged in degrees of propaganda, whereby the latter group aimed to show New York ‘as it really is’ rather than a city in crisis.

In some respect, the difference is attributable to a shift from the imperative of responding to the emergency of the early Depression towards an analysis of more enduring forms of urban poverty. If WFPL photographs, such as Seltzer’s 1933 ‘Rent Strike’, caught the ephemeral moment of a protest, then the PL developed a more sustained and integrated mode of neighborhood documentary. Working with neighborhood grassroots activist groups, the PL engaged in a form of collaborative community protest that was implicitly rather than nominally class oriented. For instance, in 1941 Photo Notes relayed that the East Side Group was collaborating closely ‘with the East Side Tenant’s League on this project […] over a period of from four to six months’, and ‘showing the same class of people’ as the earlier Pitt Street Document, but with more stress on local agency, ‘fighting for their rights thru an organization they have built’, than hopeless suffering.17 The necessarily extended process of preparation and interaction with subjects was almost the antithesis of canonical street photography’s provisionality:

They know the vital importance of a thorough knowledge of their subject before they start shooting. So for several weeks they have spent their time in learning how these people live, and how they organize their fight for a better life. Going over the subject a round table discussion, they were struck by the fine and wonderful qualities of these people, despite an environment which makes every effort to degrade and debase them. This is one of the big themes they intend to show in their pictures. To further cement their relationship with the Tenant’s League, the group sent one of its members down to talk to the Tenant League membership. He explained the Group’s purpose, and the work it wanted to do. Much applause greeted the speaker, which is a good sign that the group is being taken warmly to heart. Members of the production groups are now accompanying Tenant League organizers into the homes of its members, in order to find those people who will fit best into the story they wish to show. Shooting as such has not yet begun, except for a few pictures taken at one of the Tenant League meetings. (Ibid.)

Or as Steiner (1941, p. 47) succinctly summarized, when discussing the Pitt Street Document in PM, in aiming to convey the poverty of the area the group members quickly ‘learned that they couldn’t swallow so big a subject in one gulp’.

This collaborative approach began in the latter days of WFPL. In 1935 Siskind authored an update on ‘the Photo Section of the New York Film and Photo League’ in Film Front that provided information on several projects including ‘a comparative photo exhibit’ on ‘City Streets’, which the WFPL had invited ‘five photographic organizations of the Metropolitan area to join’.18 He also discussed a project on ‘The City Child’, which ‘will show the home, school, and recreational background of the New York City child. The committee, with the assistance of the director of Lavenburg Homes and C.O. of Pen and Hammer, are preparing statistical material which will be presented in the form of charts along with the photos’ (ibid.). ‘The City Child’ clearly echoed the National Child Labor Committee reports by Lewis Hine, the pioneer of documentary who was a lodestar for the PL, as well as anticipating the raft of photo-stories on city children in Ralph Ingersoll’s PM newspaper, such as Engel’s ‘The Problem of Keeping City Kids Off the Streets’ (PM’s Weekly, September 8, 1940) and ‘Many a Beautiful Friendship Has Started on a New York Street…There Are Lots of Good Games Kids Can’t Play Without Supervision’ (PM’s Weekly, June 29, 1941), and affiliate Bourke-White’s ‘These Are Hoboken’s Children: Are They All ‘Dead End’ Kids?’ (PM, August 12, 1940). These stories anchor the photographic representation of children on city streets within a socially oriented editorial ethos that broadly equates the aims of the document projects.

If the documentary process was extended temporally, then the presentation of these documents was also complex, mixing words, text, and statistical data supplied by the tenants’ leagues. The ‘Chelsea Document’ took form as an exhibition of photographs by Sol Libsohn and Grossman printed onto panels designed by Pat Decker and the painter Ad Reinhardt, which was held at the PL’s East 21st Street headquarters, the Chelsea Tenants’ League, and the Hudson Guild. Elizabeth McCausland described how:

Photographs, text, and presentation by visual and graphic means are combined to make these five panels, an expressive witness against the chaos and brutality of housing in New York City today […] This is a rousing plea for the people of Chelsea. In these five 4-by-8-foot panels, photographs, figures, words, symbols, arrows, guidelines, in black and in color, join to accuse the City of New York of its failure to its citizens’.19

A panel with the legend ‘Why do we live this way? We don’t have to—if we organize to fight for…’ anchored the photographs within the Chelsea Tenants’ League’s campaign for improved social housing (ibid.). Roberts (1998, p. 92) argues that the display reveals the PL’s conception of ‘documentary as a constructed mode of representation’ that drew upon the ‘multiperspectival and sequential notions of montage’, as developed in the exhibition design and magazine arrangements of Soviet Constructivists such as Alexander Rodchenko and El Lissitzky. It was, accordingly, a radical type of collective, collaborative, yet also experimental form of documentary. No mere bystanders spying on city life, the PL’s photographers participated in a neighborhood protest against the City.

The most developed, disseminated, and debated project of the PL was the Harlem Document. Between 1938 to 1939, the Feature Group, led by Siskind and including Engel, Kosofksy, Jack Manning, Lucy Ashjian, and Sol Prom, explored life in Harlem with a view to producing a book, with text by the African-American radical Michael Carter. Although none of the photographers were black there was a determined effort to seek the counsel of local groups, as a ‘Symposium on Harlem Document’, detailed in Photo Notes in June 1939, featuring Reverend J. Brown, James Flood of Harlem River Houses, the Communist Party’s James W. Ford (cited as a ‘Negro Trade Union leader’), and A. Palmer of the TB Center in Harlem.20 If the book never transpired, then the photographs appeared in national publications such as Fortune, Look, and US Camera, and in several exhibitions, beginning with ‘Towards a Harlem Document’ at the Harlem YMCA in February 1939, and later at the Harlem Branch Library and the New School for Social Research. The aim was to create ‘a fair and unbiased document of Harlem, and by collecting their comments, to convince publishers that the book will not meet with a hostile reception in Harlem on that score’.21

However, Photo Notes printed the mixed responses of visitors to the exhibition, such Ida Holden’s praise for ‘a collection of documentary evidence that should move all to action’, in contrast to B. Bryan’s complaint that ‘the pictures are true and factual but why show one side of the life of Harlem; what about the intellectual and cultural side such as the thousands at night schools, the various churches and forums, the library and its avid readers, etc.’.22 E.H. Davis strongly cautioned that ‘these pictures lack artistic value. They only show the lower living conditions of Harlem. Get pictures that will show Negroes in a better light’ (ibid.). As Maurice Berger has shown, the pessimistic view of Harlem unwittingly played into negative stereotypes that Look magazine sensationally accentuated in captioning an innocuous group of five young boys as ‘Harlem Delinquents in the Making’, whilst a feature in the Communist organ New Masses extracted political grist in grimly asserting how ‘the children of this great, foul slum lead hard, choked lives’.23

If the PL’s works were available for, if not necessarily amenable to, Communist appropriation, then what were its documentary politics? In reassessing documentary in the 1970s, Martha Rosler (1990, p. 307) coined ‘liberal documentary’ to define the New Deal photography programs, in particular the Historical Section of the Resettlement Administration and Farm Security Administration, wherein ‘poverty and oppression are almost invariably equated with misfortunes caused by natural disasters: causality is vague, blame is not assigned, fate cannot be overcome’. More recently, Jorge Ribalta (2011, p. 15) has considered the accusatory ‘proletarian documentary’ of worker photography, which amassed evidence of ‘misery and injustice’ to expose ‘the widespread, endemic social conditions of capitalism’. The PL frequently identified its documentary ethos with the photography programs of the New Deal, as evident in a 1938 statement that ‘our primary aim will be to further the type of photography exemplified by the [Tennessee Valley Authority] and the Resettlement Administration.’24 A review of US Camera by Engel explained that: ‘These photographs made for the U.S. Government and captioned with appropriate remarks by many people have the intense reality and vitality of life. All tell a story. Honestly and sincerely they picture men, women, and children suffering and struggling’.25 The WFPL, conversely, assailed the New Deal as a ‘social Fascist’ formation in comparing President Roosevelt with Hitler and Mussolini in the newsreel America Today series (1932–1934).

Yet the PL was not simply a ‘liberal documentary’ outfit and importantly defined itself as ‘the only photographic group anti-war and anti-fascist in its sympathies and the only organization fostering Documentary Photography’ in explaining why they were running a symposium on John Heartfield’s photomontages for the recently expired German Communist magazine AIZ (Arbeiter Illustriete Zeitung, Workers Illustrated News, one of the foundational worker photography forums), which were on show at the ACA gallery.26 In Photo Notes, Edward Hunt attacked Life as emblematizing the ‘pro-fascist tendencies of Il Duce’, and called for American documentary photographers to establish their own pictorial magazine similar to the German workers’ AIZ’.27 The acerbic denigration of British fashion photographer Cecil Beaton in Photo Notes for an anti-Semitic ‘slur on the Jewish race in one of his sketches for the February Vogue’ indicates the PL’s positioning political battleground of photography and necessary vigilance against anti-Semitism.28

The struggle against Fascism and its correlate in anti-Semitism was an urgent one for both the WFPL and the PL. Several accounts have assessed the street photography of the PL in relation to the predominantly Jewish ethnicity of its members. Klein makes an interesting point that the PL and New York School photographers shared a notional ‘Jewish lens’, invoking Max Kozloff’s assertion of the prevalence of Jewish figures amongst New York’s most notable photographers in his essay for New York: Capital of Photography, an earlier Jewish Museum exhibition, of 2003. In citing the PL as precursors to the New York School, Deborah Dash Moore (2008, p. 85) also emphasizes the Jewish preponderance of the respective groupings: ‘Street photography by American Jews began with the New York Photo League, which was quite literally the opening class the New York School of Photography’. Max Kozloff (2002, pp. 71, 77) divined an ‘outsider’s perspective to New York experience’ evincing ‘restless, voracious behavior’ not evident ‘among Gentile photographers’ (such as Cartier-Bresson, Evans or Abbott). He distinguishes the Jewish lens and street photography matrix from instrumental variants, claiming that ‘rather than as a place that awaits them for documentary report, they present the city as a formed instant by instant out of their impulsive responses. It is their improvised exchange with their subjects, not a kit of fixed and essential attributes, that distinguishes their work’ (ibid., p. 70). The ‘activist performance’ of the PL, in Kozloff’s reading, marked a diminishment of the Jewish lens’s preoccupations, which returned dynamically with the improvisation and the ‘quixotic discoveries’ of Frank, Arbus, and Winogrand (ibid, p. 71).

Alan Trachtenberg (2003, p. 22) has scrutinized the ‘Jewish eye’ of photography trope as a question that ‘both intrigues and amuses; it seems foolish in its blithe and not a little discomforting essentialism, troubling in the way it evokes stereotypes’. If Trachtenberg finds that the ‘Jewish eye’ conjures diaspora, adaptability, and metropolitanism but is too nebulous and amorphous for firm definition, he identifies a plausible instance in the ‘Jewish socialist humanism’ of the PL’s documentary photographs of New York:

To choose documentary or street or reportage photography as a vocation is to choose to study contemporary American society and culture as a vocation, a way of focusing your attention, your creative and critical abilities, on the here and now […] For Jews, that choice may come out of a pressing need to identify with a world in which you feel partly a stranger and partly a “type,” a way to overcome or to assert your alienation and your exile. Or out of a political hope, or love of excitement, or plain voyeurism (Ibid., p. 25).

Therefore, if one allows that the concept of the Jewish lens is a paradoxically imprecise yet substantive synthesis, it is possible that the PL’s analysis of the city inflected the assorted bystanders of the New York School with the criticality of a legacy of strident resistance to anti-Semitism, formed in the militancy of the WFPL. The fleet, analytical camera work of WFPL photographs could also map onto the conflation of the Jewish lens and street photography, and yet they do not feature in any scholarly elaborations of this conception. After all, the photographers and filmmakers of the WFPL (for instance, Seltzer, Steiner, Brody, Potamkin, and Siskind) were also predominantly Jewish. They arose in a radical milieu in the 1920s that had a diasporic character, namely the clusters of communists and avant-garde writers and artists around New Masses and Daily Worker, with strong residual links to the USSR, due to their origins (or those of their parents) in Russian Empire and specifically the Pale of Settlement, and memories of anti-Semitism.29 Depictions of demonstrations in 1933 against the arrival in the United States of Nazi Emissary Hans Weidemann in the film America Today, and scenes of anti-fascist protests in photographs, witness the view of the WFPL, and later the PL, that it could ‘happen here’, on the streets of New York. About this, the Jewish lens was especially acute and alert.

In developing a mode of social documentary that was combined with community activism, the PL may not have espoused proletarian revolution, but was emblematic of the conciliatory cultural tactics of the Popular Front Era to expand the fight against Fascism. Its ethos of collaborative in-depth investigation of the city, at least in its early incarnation, was not the detached ‘liberal documentary’ representation of ‘the other half’ but a powerful expression of New York as a working-class, multi-ethnic, immigrant and migrant city, and constituted a portfolio of documents produced by photographers of those demographics. In this sense, the PL’s group projects marked an unexpected extension, rather than abandonment, of the former mandate, as a form of deep analysis of aspects of proletarian experience in the city.

The documents were not trouble free—the PL’s attempt to capture Harlem’s specific character was well-intentioned but their grasp was weak and their assessment was low on nuance—yet it is worth remembering that these were experimental projects to enhance students’ photographic understanding as well as socially engaged visualizations of urban conditions. In the post-WWII period the PL jettisoned the Feature and Documentary Groups but retained a strong belief in the group. Against the specter of HUAC, Rosemblum wrote: ‘We are bolstered in our struggle to speak through our art by unity with all other photographers who face the same problems. By remaining isolated, as individuals, we know that the battle is difficult to win’.30 However, in its early days the PL had arrived at a multifaceted documentary examination of everyday life, originated though not fully realized within the WFPL, whose collaborative ethos helped, to an extent, to mitigate the distanced, voyeuristic, and exploitative tendencies of some social documentary work. They were not bystanders but participants whose documents were not mere documentary reportage but collaborative projects that necessitated long-term, rather than momentary, coverage. As an interactive, collective grassroots editorialization of New York’s (primarily disadvantaged) neighborhoods, these potent documents, therefore, cannot comfortably fit within the museological frame of street photography.

Funding

This research was funded by a Terra Foundation Postdoctoral Travel Grant on ‘Skyscrapers and Scrapheaps: American Photographic Culture in the Early Years of the Great Depression, 1929–1933’, grant number 0614-4-2h.

Acknowledgments

This article develops from a paper that I delivered at EBAAS 2018, the 32nd European Association for American Studies and 63rd British Association for American Studies Conference, at King’s College London. I would also like to thank Russell Campbell for generously sharing research materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Alexander, William. 1988. Film on the Left: American Documentary Film From 1931 to 1942. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Maurice. 2011. Man in the Mirror: Harlem Document, Race, and the Photo League. In The Radical Camera: New York’s Photo League, 1936–1951. Edited by Mason Klein and Catherine Evans. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bezner, Lili Corbus. 1999. Photography and Politics in America: From the New Deal into the Cold War. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brookman, Philip. 2010. A Window on the World: Street Photography and the Theater of Life. In Exposed: Voyeurism, Surveillance, and the Camera. Edited by Sandra S. Phillips. London: Tate Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Russell. 1977. ‘Introduction’, Film and Photo League: Radical Cinema in the 30s. In Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media. Available online: https://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/onlinessays/JC14folder/FilmPhotoIntro.html (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- Campbell, Russell. 1979. America: The (Workers) Film and Photo League. In Photography/Politics One. Edited by Terry Dennett and Jo Spence. London: Photography Workshop. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Russell. 1982. Cinema Strikes Back: Radical Filmmaking in the United States 1930–1942. Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cartier-Bresson, Henri. 1952. Images à la Sauvette. Paris: Verve. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, Herman O. 1933. Introduction. In Chicago on Parade. Chicago: Herman O. Duncan. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, Russell. 2001. Open City: The Possibilities of the Street. In Open City: Street Photographs Since 1950. Edited by Kerry Brougher and Russell Ferguson. Oxford: Museum of Modern Art Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Gautrand, Jean-Paul. 1978. Aaron Siskind. Nouveau Photo Cinema, April: 64. [Google Scholar]

- Green, Jonathan. 1984. American Photography: A Critical History 1945 to Present. New York: Harry N. Abrams. [Google Scholar]

- Haran, Barnaby. 2011. Machine, Montage, and Myth: Experimental Cinema and the Politics of Modernism during the Great Depression. Textual Practice 5: 563–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haran, Barnaby. 2016. Watching the Red Dawn: the American Avant-Garde and the Soviet Union. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hemingway, Andrew. 2002. Artists on the Left: American Artists and the Communist Movement. 1926–1956. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, Irving. 1976. World of Our Fathers. New York: Harcourt Brace and Janoanovich. [Google Scholar]

- Kerouac, Jack. 2008. ‘Introduction’, Robert Frank. In The Americans, 1959. Washington: National Gallery of Art and Steidl. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Mason. 2011. Of Politics and Poetry: The Dilemma of the Photo League. In The Radical Camera: New York’s Photo League, 1936–1951. Edited by Mason Klein and Catherine Evans. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kozloff, Max. 2002. New York: Capital of Photography. In New York: Capital of Photography. New York: The Jewish Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Deborah Dash. 2008. On City Streets. Contemporary Jewry 28: 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, Gilles. 1998. PhotoSpeak: A Guide to the Ideas, Movements, and Techniques of Photography, 1839 to the Present. New York: Abbeville Press Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, James. 1991. The Proletarian Moment: The Controversy over Leftism in Literature. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ordinary Miracles: The Photo League’s New York. 2012. Directed by Daniel Allentuck and Nina Rosenblum. New York: The Orchard.

- Panzer, Mary. 2011. This is the Photo League. Aperture 204: 36. [Google Scholar]

- Potamkin, Harry Alan. 1977. Film and Photo Call to Action. In The Compound Cinema: The Film Writings of Harry Alan Potamkin. Edited by Lewis Jacobs. New York: Teachers College Press. First published in 1931. [Google Scholar]

- Ribalta, Jorge, ed. 2011. The Worker Photography Movement (1926–1939): Essays and Documents. Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte, Reina Sofia. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, John. 1998. The Art of Interruption: Realism, Photography, and the Everyday. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosler, Martha. 1990. In, Around, and Afterthoughts (on Documentary Photography). In The Contest of Meaning: Critical Histories of Photography. Edited by Richard Bolton. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer, Leo. 1988. Looking Back—With Your Eyes Wide Open! Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, Ralph. 1941. Young Cameramen Get Under Pitt Street’s Skin. PM, January 5. [Google Scholar]

- Stephany, Jaromir. 1994. ‘Interview with Aaron Siskind’, 1963. In Aaron Siskind: Towards a Personal Vision, 1935–1955. Edited by Deborah Martin Kao and Charles A. Meyer. Chestnut Hill: Boston College Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Stimson, Blake. 2006. The Pivot of the World: Photography and its Nation. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, Frances. 1930. Workers Photo Exhibit. New Masses 5: 20. [Google Scholar]

- Trachtenberg, Alan. 2003. The Claim of a Jewish Eye. Pakn Treger 41: 22. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, Anne Wilkes. 1994. History of the Photo League. History of Photography 18: 174–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, Anne Wilkes, Claire Gass, and Stephen Daiter. 2001. This Was the Photo League: Compassion and the Camera from the Depression to the Cold War. Chicago: Stephen Daiter Gallery. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Ian. 2002. City Gorged with Dreams: Surrealism and Documentary Photography in Interwar Paris. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, Frank. 2011. ‘The Camera is a Weapon in the Class Struggle’, Manuscript, 1934. In The Worker Photography Movement (1926–1939): Essays and Documents. Edited by Jorge Ribalta. Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte, Reina Sofia. [Google Scholar]

- Westerbeck, Colin, and Joel Meyerowitz, eds. 1994. Bystander: A History of Street Photography. London: Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | ‘Documentary Group’, Photo Notes, February 1938, p. 1. |

| 2 | For an excellent short history of the Workers Film and Photo League’s photography, see (Campbell 1979, pp. 92–97). |

| 3 | ‘Student Exhibition Successful’, Photo Notes, December 1938, p. 2. |

| 4 | For an excellent short history of the WFPL’s photography, see (Campbell 1979). For contextual discussion of worker photography, see (Ribalta 2011, pp. 12–23; Haran 2016—in particular, chapter four: ‘Camera Eyes: the Worker Photography Movement and the New Vision in America’, pp. 130–73); Other resources on the WFPL include (Campbell 1982; Alexander 1988; Haran 2011). For histories of the Photo League, see (Tucker 1994; Tucker et al. 2001; Bezner 1999—especially chapters one and two, pp. 16–120). See also the fascinating film by Allentuck and Rosemblum about the PL (Ordinary Miracles: The Photo League’s New York 2012). |

| 5 | ‘Street Photography’, Museum of Modern Art, https://www.moma.org/collection/terms/179 (accessed on 19 March 2019). |

| 6 | https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/display/bp-spotlight-source/street-photography (accessed on 1 February 2019). |

| 7 | ‘New Documents’, press release, New York: Museum of Modern Art, 28 February I967, https://www.moma.org/momaorg/shared/pdfs/docs/press_archives/3860/releases/MOMA_1967_Jan-June_0034_21.pdf (accessed 18 January 2019). |

| 8 | Beatrice Kosofsky to Eliot Elisofon, 28 November 1939, AG 30: 36, Aaron Siskind Papers, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: Tucson. |

| 9 | ‘Interview with Leo Seltzer’, conducted by Blackside, Inc. in 1990, for The Great Depression, Washington University Libraries, Film and Media Archive, Henry Hampton Collection. http://digital.wustl.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=gds;cc=gds;rgn=main;view=text;idno=sel00031.00640.022 (accessed on 12 December 2018). |

| 10 | ‘Our Photo Group’, Labor Defender, July 1930, p. 149. |

| 11 | Alexander Alland, ‘Break the Grip of Exploitation’, 1938, gelatin silver print. https://thejewishmuseum.org/collection/31101-break-the-grip-of-exploitation. |

| 12 | Indeed, in 1934 a WFPL fundraising event included an exhibition of photography by a collectively credited WFPL group (which likely included Seltzer’s photographs) alongside works by members Steiner and Abbott (who is also listed as the WFPL’s treasurer), fellow traveler Margaret Bourke-White, and the New York photographer and filmmaker Irving Browning. Film and Photo League, ‘First Annual Motion Picture and Costume Ball’, Flyer, 1934, Margaret Bourke-White Papers, Syracuse University, Box 17. |

| 13 | Paul Strand, ‘Letter to Art Front’, 1937, AG17: 7/3, Paul Strand Papers, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: Tucson. |

| 14 | Paul Strand, ‘Morris Engel: Photographs of People’, New York: New School for Social Research, December 1939, Paul Strand Papers, Box 7 AG 17: 7/3, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: Tucson; see also Paul Strand, ‘Engel’s One-Man Show’, Photo Notes, December 1939, p. 2. |

| 15 | ‘Believe It or Not!’, Photo Notes, April 1939, p. 3. |

| 16 | ‘Disraeli to Head League Project’, Photo Notes, January 1939, p. 1. |

| 17 | ‘East Side Group’, Photo Notes, March–April 1941, p. 2. |

| 18 | Aaron Siskind, ‘New York Photo Activities’, Film Front, 28 January, p. 14. |

| 19 | ‘The Chelsea Document’, Photo Notes, May 1940, pp. 4–5. |

| 20 | ‘Symposium on Harlem Document’, Photo Notes, June 1939, p. 1. |

| 21 | ‘Harlem Document Meeting Notes’, 9 February 1939, AG 30: 36, Aaron Siskind Papers. |

| 22 | ‘Feature Group’s “Towards a Harlem Document”’, Photo Notes, April 1939, p. 2. |

| 23 | (Berger 2011); ‘Harlem Children’, New Masses, 16 May 1939, p. 10. |

| 24 | ‘For a League of American Photographers’, Photo Notes, August 1938, p. 4. |

| 25 | ‘US Camera Annual, 1939’, Photo Notes, January 1939, p. 4. |

| 26 | ‘John Heartfield’s Photo Montage at ACA Gallery’, Photo Notes, October 1938, p. 1. |

| 27 | ‘Photo Magazine Craze’, Photo Notes, August 1938, p. 2. |

| 28 | ‘Anti-Semitism Laid to Artistic Temper’, Photo Notes, February 1938, p. 2. |

| 29 | See (Haran 2016; Hemingway 2002; Murphy 1991; Howe 1976). |

| 30 | Walter Rosenblum, ‘Some Thoughts about the League’, Photo Notes, November 1947, p. 7. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).