Revisiting Harrison and Cynthia White’s Academic vs. Dealer-Critic System

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Exhaustive Surveys of 1875, 1900 and 1925

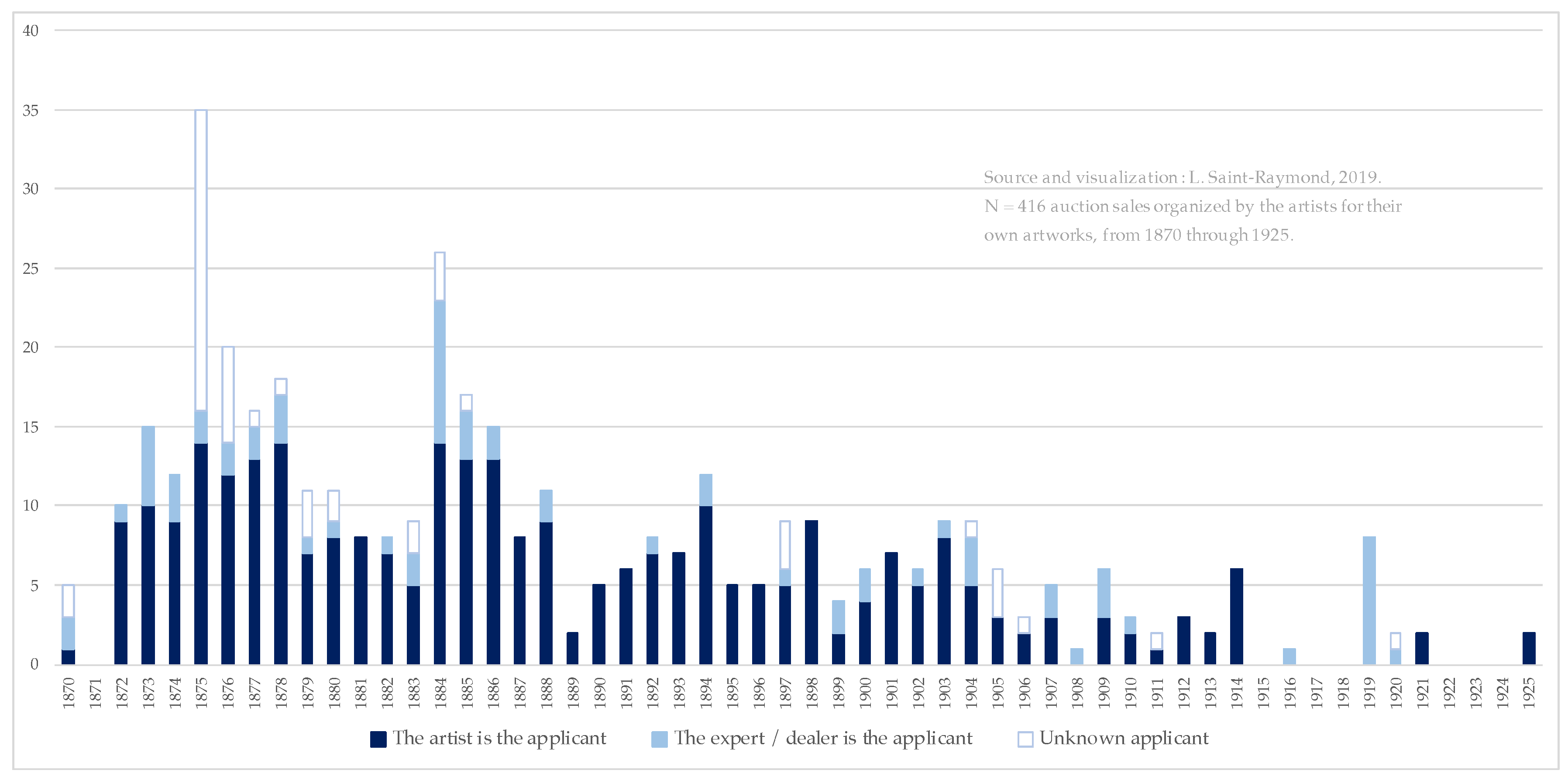

2.2. Auctions Organized to Their Artists for Their Own Works

2.3. Econometric Analysis of These Two Datasets

3. Results

3.1. The Salon And the Market: Complementary and Non-Rival Systems (1850s–1870s)

3.1.1. Evidence from the Global Econometric Regression

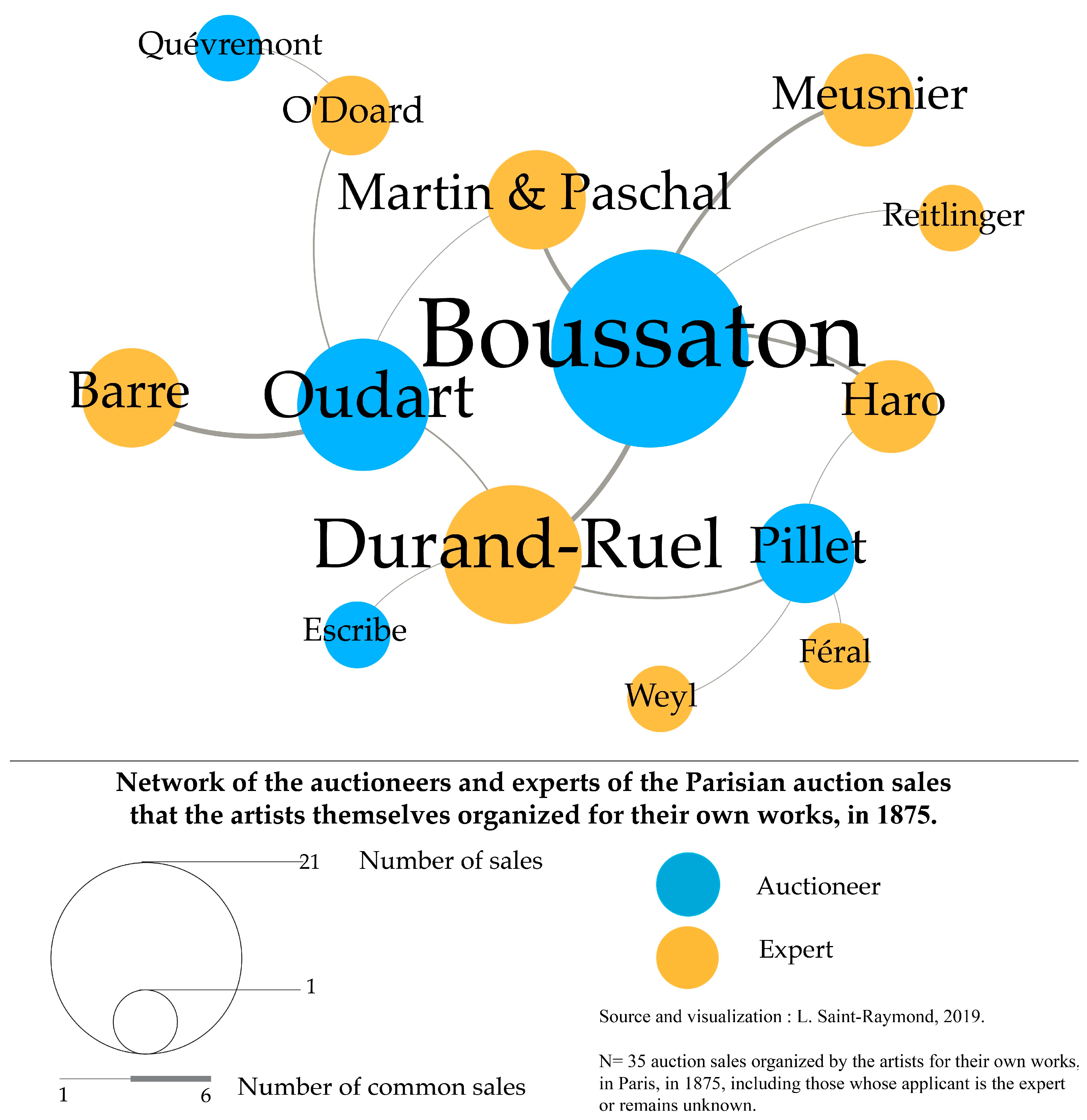

3.1.2. Evidence from the Auction Sales Organized by the Artists Themselves

3.2. The Collapse of the Salon System? (1880s–1910s)

3.2.1. Evidence from the Global Econometric Regression

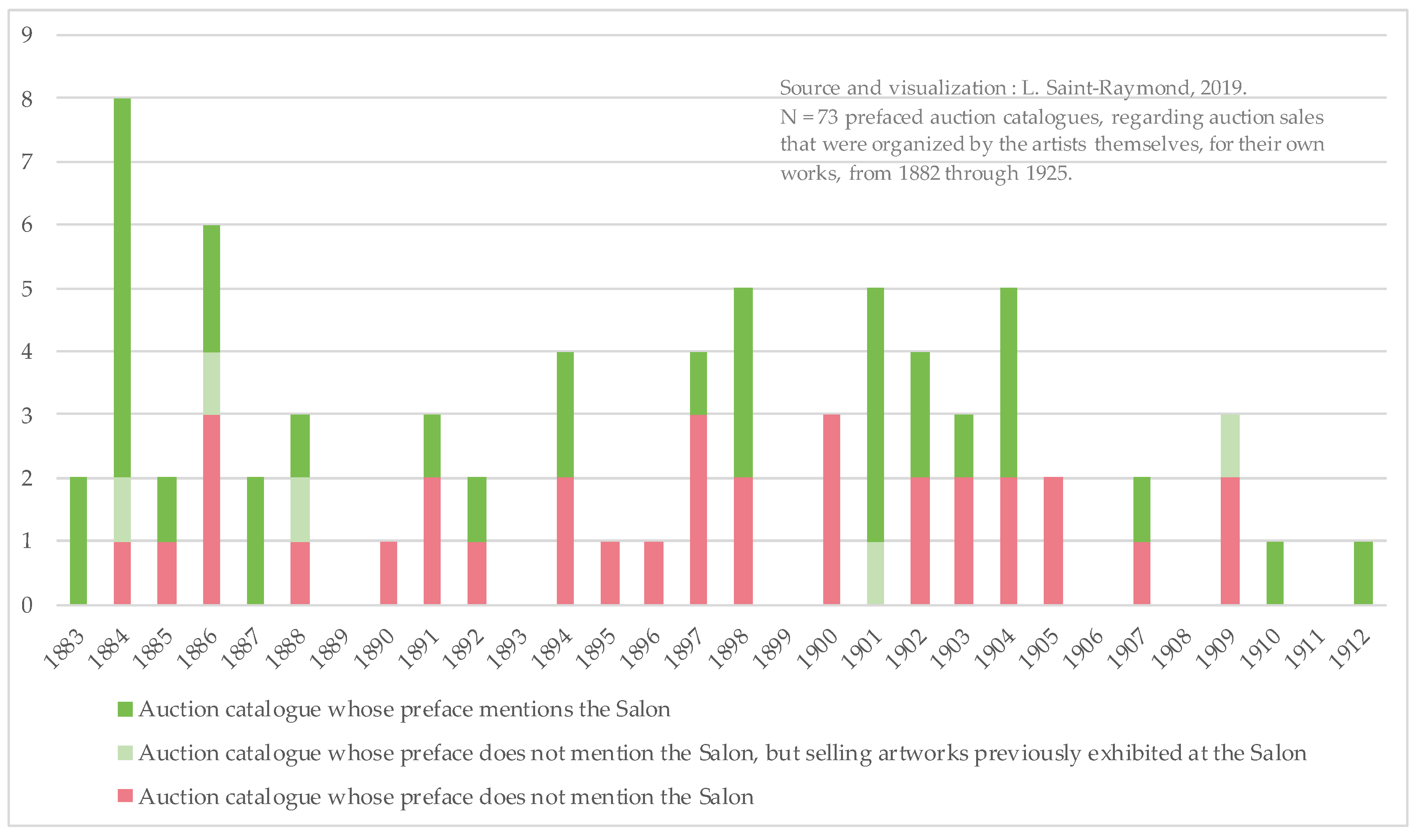

3.2.2. Evidence from the Auction Sales Organized by the Artists Themselves

While visiting the 1887 Salon with a famous painter of my friends, I stopped in front of an attractive painting entitled: Old Memories. […] It was a painting by Mrs. Euphémie Muraton, whose artistic reputation spread so brilliantly. My companion considered this exquisite canvas for a long time, then he said to me: “Here is some painting! […] See how all this sings in a discreet and fair harmony. This is one of the best things at the Salon.” I found this painting among those of Mrs. Muraton who were selected for this sale, and it seemed even more charming to me.39

3.3. The End of the Salon, after the Great War

4. Discussion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | 1875 | 1900 | 1925 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Painting | −2.577577 | 976.6633 *** | 4667.118 *** |

| (291.4905) | (376.4808) | (1132.918) | |

| Sculpture | 1125.333 | 376.4808 | 2290.68 |

| (1565.902) | (2139.733) | (7114.906) | |

| “Made By” | 853.1979 *** | 1253.692 ** | 8.172.804 *** |

| (394.8068) | (596.0833) | (2171.302) | |

| “Style of” | −904.3692 * | 7.201052 | −3212.035 |

| (496.9929) | (677.7574) | (2495.963) | |

| Height | 14.94605 *** | 10.0338 *** | 38.86232 *** |

| (2.168301) | (2.908872) | (12.11977) | |

| Signature | 126.7633 | −100.1319 | −201.1149 |

| (204.9359) | (277.6439) | (1384.687) | |

| Pedigree | 296.1964 | 806.9372 ** | 3969.486 ** |

| (322.3809) | (387.77) | (1831.402) | |

| Salon | 2528.304 *** | 16,209.97 *** | −4689.303 |

| (939.5785) | (1601.941) | (8974.269) | |

| Exhibition | 5790.827 *** | 3069.401 *** | 45,417.9 *** |

| (1291.572) | (670.9129) | (3270.153) | |

| Bibliography | −416.5251 | 8889.937 *** | 18,680.4 *** |

| (911.2249) | (2297.308) | (3127.569) | |

| Engraved? | 1201.144 *** | 1575.31 * | 10,383.6 * |

| (418.404) | (891.4136) | (5608.545) | |

| Nb of words | 41.0335 *** | 25.7238 *** | 288.9323 *** |

| (3.425411) | (2.767241) | (18.35597) | |

| Reproduced | dropped | 3836.237 *** | 5149.076 *** |

| (309.124) | (1306.833) | ||

| Sold by artist? | 392.3854 | dropped | dropped |

| (1039.564) | |||

| cons | −1106.097 ** | −2095.695 *** | −9603.649 *** |

| (462.4755) | (610.9522) | (2153.349) | |

| Nb of obs | 2102 | 2645 | 4853 |

| Nb of groups | 838 | 847 | 1441 |

| R within | 0.2487 | 0.3096 | 0.2649 |

| R between | 0.1327 | 0.2535 | 0.3580 |

| R overall | 0.1619 | 0.3515 | 0.2883 |

| Variables | Model 1 (1870–1881) | Model 2 (1870–1881) | Model 3 (1882–1912) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Already come | −58.58362 | −52.16356 | |

| (78.33594) | (80.08711) | ||

| Sculptor | 405.9364 *** | 526.354 *** | 18.68906 |

| (115.2474) | (101.8726) | (81.08568) | |

| Age | −8.824865 | −9.531771 * | 105.467 ** |

| (5.560554) | (5.738429) | (49.67375) | |

| Experience | 5.417284 | 9.238528 | |

| (5.747833) | (5.592) | ||

| Nb of lots | −1.044642 * | −0.8757923 | −2.458129 |

| (0.5454692) | (0.5519728) | (1.878516) | |

| Hors concours | 201.0647 ** | ||

| (97.29017) | |||

| Medal | 27.92747 | ||

| (239.9008) | |||

| Mention of the Salon | 105.467 ** | ||

| (49.67375) | |||

| Illustrated cat. | dropped | dropped | 91.90935 * |

| (51.13315) | |||

| cons | 634.4661 *** | 613.0044 *** | 218.057 * |

| (221.4988) | (232.1221) | (111.7723) | |

| Nb of obs | 98 | 98 | 66 |

| R | 0.2951 | 0.2622 | 0.2814 |

References

- Ashenfelter, Orley, and Kathryn Graddy. 2003. Auctions and the Price of Art. Journal of Economic Literature, American Economic Association 41: 763–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailly-Herzberg, Janine. 1985. Lettres de Ludovic Piette à Camille Pissarro. Paris: Éditions du Valhermeil. [Google Scholar]

- Bénézit, Emmanuel, ed. 1999. Dictionnaire Critique et Documentaire des Peintres, Sculpteurs, Dessinateurs et Graveurs de tous les temps et de tous les pays, par un Groupe d’écrivains Spécialistes Français et étrangers. Paris: Gründ, vol. 14. First published 1911. [Google Scholar]

- Bouillon, Jean-Paul. 1986. Sociétés d’artistes et institutions officielles dans la seconde moitié du XIXe siècle. Romantisme 54: 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, Géraldine, and Kim Oosterlinck. 2015. War, Monetary Reforms and the Art Market. Financial History Review 22: 157–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maupeou, Félicie, and Léa Saint-Raymond. 2013. Les “marchands de tableaux” dans le Bottin du commerce: Une approche globale du marché de l’art à Paris entre 1815 et 1955. Artlas Bulletin 2. Available online: http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/artlas/vol2/iss2/7/ (accessed on 17 January 2019).

- Fage, André. 1930. Le Collectionneur des Peintures Modernes. Comment Acheter. Comment Vendre. Paris: Editions pittoresques. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, Abram, and Matthew Lincoln. 2016. The Temporal Dimensions of the London Art Auction, 1780–1835. British Art Studies. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galenson, David W., and Robert Jensen. 2002. Careers and Canvases: The Rise of the Market for Modern Art in the Nineteenth Century. Working Paper 9123, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series. National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, Robert. 1994. Marketing Modernism in Fin-de-Siècle Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Joyeux-Prunel, Béatrice. 2009. «Nul n’est prophète en son pays?» L’internationalisation de la Peinture des Avant-Gardes Parisiennes 1855–1914. Paris: Musée d’Orsay/Nicolas Chaudun. [Google Scholar]

- Lugt, Frits. 1938. Répertoire des Catalogues de ventes Publiques Intéressant l’art ou la Curiosité. The Hague: Nijhoff, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Mainardi, Patricia. 1993. The End of the Salon: Art and the State in the Early Third Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maingon, Claire. 2009. Le Salon et ses Artistes. Histoire des expositions du Roi Soleil aux Artistes français. Paris: Hermann. [Google Scholar]

- Maurice, René. 1971. Le commissaire-Preneur et les ventes Publiques de Meubles. Paris: Librairie générale de droit et de jurisprudence. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, Jianping, and Michael Moses. 2002. Art as an Investment and the Underperformance of Masterpieces. The American Economic Review 92: 1656–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnier, Gérard. 1995. L’art et ses Institutions en France de la Révolution à nos jours. Paris: Gallimard. [Google Scholar]

- Moreau-Nélaton, Etienne. 1924. Corot Raconté par lui-même. Paris: Henri Laurens. [Google Scholar]

- Renneboog, Luc, and Christophe Spaenjers. 2012. Buying Beauty: On Prices and Returns in the Art Market. Management Science 59: 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouillon, Pierre. 1928. Le commissaire-priseur et l’hôtel des ventes. Toulouse: Imprimerie languedocienne. [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Raymond, Léa. 2016a. How to Get Rich as an Artist: The Case of Félix Ziem. Evidence from His Account Book from 1850 through 1883. Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 15. Available online: https://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring16/saint-raymond-on-how-to-get-rich-as-an-artist-felix-ziem (accessed on 17 January 2019).

- Saint-Raymond, Léa. 2016b. Le prix des sculptures en vente publique à Paris (1849–1900): Données et résultats des régressions linéaires. Harvard Dataverse. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Raymond, Léa. 2018a. Produit de la bourse commune des commissaires-priseurs parisiens entre 1831 et 1936. Harvard Dataverse. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Raymond, Léa. 2018b. Alberto Pasini, un orientalista italiano al Salon. In Pasini e l’Oriente. Edited by Paolo Serafini and Stefano Roffi. Milan: Silvana Editoriale, pp. 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Raymond, Léa. 2018c. The auction sales of paintings, drawings and sculptures in Paris (1831–1925): Artists, hammer prices and purchasers. Harvard Dataverse. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Raymond, Léa. 2018d. Le pari des enchères: Le lancement de nouveaux marchés artistiques à Paris entre les années 1830 et 1939. Corpus bibliographique des ventes aux enchères publiques considérées. Harvard Dataverse. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Raymond, Léa. 2018e. Les ventes aux enchères organisées par les artistes, à Paris, pour leurs propres œuvres (1826–1925). Harvard Dataverse. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Raymond, Léa. 2018f. Les ventes de tableaux, arts graphiques et sculptures à Paris en 1831, 1850, 1875, 1900 et 1925: Données pour l’analyse économétrique du prix d’adjudication. Harvard Dataverse. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Raymond, Léa. 2018g. Le Pari des Enchères: Le Lancement de Nouveaux Marchés Artistiques à Paris Entre les Années 1830 et 1939. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Paris Nanterre, Nanterre, France. [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Raymond, Léa. 2019. «Ce n’est pas de l’art mais du commerce!». L’ascension du marché comme prescripteur. Marges 28: 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Vaisse, Pierre. 1983. Annexe sur l’image du marchand de tableaux pendant le XIXe siècle. Romantisme 40: 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaisse, Pierre. 1995. La Troisième République et les peintres. Paris: Flammarion. [Google Scholar]

- White, Harrison, and Cynthia Alice White. 1965. Canvases and Careers, Institutional Change in the French Painting World. New York, London and Sydney: J. Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

| 1. | The Salon was biennial from 1798, annual from 1833 to 1851, again biennial from 1853 to 1863, then annual from 1864 (Monnier 1995, p. 124). |

| 2. | “The dealers and critics, one marginal figures to the Academic system, became, with the impressionists, the core of the new system.” (White and White 1965, p. 151). |

| 3. | The bibliography of the art market is very abundant. Nevertheless, the majority of publications do not take this institutional change as the focus of their study—for example, monographic studies of dealers, such as Goupil, Durand-Ruel, Vollard or Kahnweiler. Robert Jensen analyzed the socio-economic profile of dealers (Jensen 1994) and Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel, that of the avant-gardes (Joyeux-Prunel 2009). |

| 4. | This two-fold source is the only one that provides a comprehensive dataset. The private sales between dealers, collectors and artists thus constitute a blind spot, as there is no available and global archive. |

| 5. | I started in 1831 when the total revenue of the Parisian auctioneers become available; I then moved to 1850; taking a sample in 25 year blocks thereafter. |

| 6. | The auction catalogues were collected at the INHA library, at the Département des Estampes of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, on gallica and at the library of the Ecole nationale des beaux-arts. The choice of catalogues is based on the “long” title, and not on the short title of the first cover: this is why I had to carefully examine all the catalogues concerning the years of interest, without stopping at the library search engines which, generally, only take the short title into account. |

| 7. | I separated the following fields into different columns: date and venue of auction sale, names and addresses of the auctioneer and expert, short and long title of the catalogue, name of the seller, amount of buyer fee, total number of lots, number of pages in the catalogue, possible presence of illustrations, presence of a preface and name of any prefacier, name and address of the publisher. |

| 8. | Regarding the artwork, I separated the following fields into different columns: section of the catalogue in which the artwork was sold, catalogue number, name of the artist, title, date, presence of a signature, dimensions, medium, comprehensive description of the work, presence of a reproduction, exhibitions in which it appeared, possible exhibition of the work at the Salon, previous auction sales and collectors—this information forms the “pedigree” of the work-, mention of an engraving of the work and presence of a bibliography documenting the object. The catalogue annotations, if any, were added in separate columns, for the hammer price, the purchaser and, more rarely, the price setting and estimation. |

| 9. | In the other countries, the auctioneers were not considered as ministerial officers, i.e., State representatives, subject to very strict legislation. In England, for instance, there are no regulations on auctions (Maurice 1971, p. 41–56). |

| 10. | The “real” seller can use an intermediary: in this case, the minute of the sale would only mention the name, address and occupation of the latter. Regarding the auction sales with different sellers—”composite sales” or “ventes composées”-, please confirm/ LSR : yes, necessary. the list of all the sellers appeared in the minutes from the 1920 onwards: beforehand, only the name of the expert was mentioned. |

| 11. | The information on the winning bidder’s identity was not mandatory in the minutes, for instance it was absent from the minutes of the Bordeaux auction sales (Rouillon 1928, p. 109). |

| 12. | See, for instance, (Mei and Moses 2002; Ashenfelter and Graddy 2003; Renneboog and Spaenjers 2012; David and Oosterlinck 2015). |

| 13. | A dummy variable equals to 1 if the proposition is true (e.g., the artwork is a painting), 0 otherwise. |

| 14. | In this case, I used a dummy variable (“signature”) which equals to 1 if the catalogue mentions a signature for the artwork put up for sale, 0 otherwise. |

| 15. | The “Exhibition” variable thus includes the mention, by the auction catalogue, of an exhibition in a dealer’s gallery or in an “unofficial” Salon, such as the Salon d’Automne, the Salon of the Société nationale des Beaux-Arts... |

| 16. | The quitus are administrative documents produced by the auctioneers themselves and by the Chambre des Commissaires-priseurs parisiens. These “settling of accounts” made it possible to verify that the previous management of the outgoing auctioneer was in good standing, thus giving him the right to retire and receive reimbursement of his bond. The individual quitus, available in the Paris archives since 1864, are a valuable source for the researcher because they provide an exhaustive list of the auctioneer’s sales during the year in question: the date of the minutes—which corresponds to the date of the sale-, the nature of the minutes—voluntary sale, legal sale, etc.—the name of the seller, and above all, the total amount of the sale in current francs. |

| 17. | I had to check that it was indeed the artist who had put his works on sale, and not a private individual who wanted to market the works of an artist of whom he would have been an amateur. |

| 18. | The hammer price is expressed without using a logarithm transformation, which keeps the reading of Table 1 in current francs, not in percentages. |

| 19. | To highlight causalities, it is necessary to deploy a heavier protocol with instrumental variables, which is difficult for the art market. |

| 20. | The R within gives the part of the intra-individual variability of the left variable explained by those of the right variables. The R between estimates the contribution of the fixed effects to the model. The R overall reflects the overall quality of the regression. |

| 21. | Lugt 35571, lot 56. The bibliographic reference of the auction catalogue is summarized by its number in the repository by Frits Lugt (1938), and it is available online (Saint-Raymond 2018d). |

| 22. | Regarding the sculptures, the exhibition at the Salon was even the strongest variable in the increase in the hammer price (Saint-Raymond 2016b). |

| 23. | Jean-Paul Bouillon (1986, p. 92) confirms that the “public sale system, particularly at the hôtel Drouot”, was one of the three sectors of the “parallel market” at the Salon, along with the network of dealers and the associative formula, which developed in the years 1850–1860. |

| 24. | For instance, Jules Boussaton encouraged Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot to organize an auction sale of his paintings in 1858. (Moreau-Nélaton 1924, p. 117). |

| 25. | Letter from Ludovic Piette to Camille Pissarro, 30 January 1872 (Bailly-Herzberg 1985, p. 70). |

| 26. | Only Louise Adèle Dumoulin, Louise Daru and Berthe Morisot sold their own works at auction between 1852 and 1881. |

| 27. | Lugt 36282, Ernest Chesneau’s, p. 1. This expression is repeated in Louis Énault’s preface for the Hugard sale in 1878 (Lugt 38218, p. 1). |

| 28. | Lugt 35506, Philippe Burty’s preface, p. 1 |

| 29. | This accusation is explicit in Ernest Chesneau’s preface: Lugt 36282, p. 1. |

| 30. | Lugt 36135, Philippe Burty’s preface, p. 1. |

| 31. | Lugt 36282, Ernest Chesneau’s preface, p. 1. |

| 32. | Lugt 35506, Philippe Burty’s preface, p. 1. |

| 33. | Lugt 24157. |

| 34. | Lugt 34703, 35492, 35496 and 35521. |

| 35. | In 1876, Ernest d’Hervilly stated, in the preface to the sale of Jules Héreau, that the artist had obtained “for ten years the medals of the official Jury” (Lugt 36364, p. 1) but the Salon catalogue, this year, did not specify any official reward. |

| 36. | Hervier organized seven sales, from 1856 to 1878, and Navlet, ten, between 1869 and 1885. |

| 37. | Théophile Gautier wrote an article in the Moniteur universel of 11 February 1858, which was included in the preface to the sale of 5 April 1875 (Lugt 35516) and Philippe Burty wrote the preface to the following sale (Lugt 36195). |

| 38. | See (Saint-Raymond 2018e) for more details about these auction sales. |

| 39. | En visitant le Salon de 1887 avec un peintre célèbre de mes amis, je m’arrêtai devant un séduisant tableau intitulé : Vieux Souvenirs. […] C’était une œuvre de Mme Euphémie Muraton, dont le renom artistique s’est si brillamment étendu. Mon compagnon de promenade considéra longuement cette toile exquise, puis il me dit : « Tenez, voilà de la peinture ! […] Voyez comme tout cela chante dans une harmonie discrète et juste. C’est là une des meilleures choses du Salon.» J’ai retrouvé ce tableau parmi ceux de Mme Muraton qui ont été choisis pour être mis en vente, et il m’a paru plus charmant encore. (Author’s translation) |

| 40. | Lugt 47210, lot 1. |

| 41. | These eight paintings did not exceed 500 francs. Lugt 88024 lots 49–53, Lugt 89502 lot 134 et Lugt 89394 lot 141. |

| 42. | Lugt 88024, lots 52, 54 and 40, repurchased respectively 150, 205 and 250 francs excluding fees. |

| 43. | Lugt 88156, lot 8. Lugt 88121, lot 84. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saint-Raymond, L. Revisiting Harrison and Cynthia White’s Academic vs. Dealer-Critic System. Arts 2019, 8, 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030096

Saint-Raymond L. Revisiting Harrison and Cynthia White’s Academic vs. Dealer-Critic System. Arts. 2019; 8(3):96. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030096

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaint-Raymond, Léa. 2019. "Revisiting Harrison and Cynthia White’s Academic vs. Dealer-Critic System" Arts 8, no. 3: 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030096

APA StyleSaint-Raymond, L. (2019). Revisiting Harrison and Cynthia White’s Academic vs. Dealer-Critic System. Arts, 8(3), 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030096