Abstract

Informed by an interesting recent infrastructuralist turn in media studies and by an expanding sense among historians and theorists of photography of what might properly delimit the photographer’s toolkit, this essay considers aspects of the photography of Weegee, as these can be observed to issue from that photographer’s deep professional embeddedness in specific media-infrastructural conditions of the place and time he most productively inhabited: New York City in the early 1940s. This essay prompts questions (and hazards some answers) concerning the stakes of Weegee’s press-photographic engagements with the material, electronic, and atmospheric infrastructures of wartime dairy delivery, underground transport, and, most urgently, policing, so to better understand the fit of his pictures to the world they so cleverly described.

Imagine that the world can be likened to an enormous set of broadcasting stations, each one emitting its signal or its programme at its proper wavelength … The emission is continuous, corresponding to the truism that something is always happening … The set of … events, then, is like the cacophony of sound one gets by scanning the dial of one’s radio receiver … Since we cannot register everything we have to select, and the question is what will strike our attention?()

1. Milk City

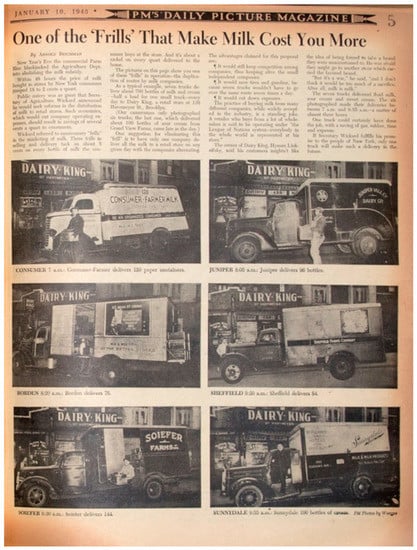

One early one morning in January 1943, the New York City newspaper photographer Weegee positioned himself across the street from Dairy King at 139 Havemeyer St. in Brooklyn and he photographed, within a fixed frame, every truck that stopped between 07:00 and 10:00 to deliver cartons and bottles of milk there (Figure 1). To what end? This slow and watchful procedure yielded six pictures, published by the local tabloid daily PM on January 10, in a captioned grid stacked three upon three. These pictures varied only in the make of trucks and in the company logos they bear, and in the captions’ reported details of time and of number of bottles or cartons delivered: “Borden delivers 76”; “Sunnydale 100 bottles of cream,” and so on. Here was no murder or fire or wreck or brawl, and not even any obvious human interest, such as we have come to expect of this photographer in his later Naked City moment.1 The news was rather more prosaic: a distant regulatory tweak had led to a spike in local milk prices. In their wake, the Agriculture Department had identified an inefficiency and prescribed its cost-saving corrective: to offset a sudden 2¢ jump in the price of a quart of milk, it would be necessary to eliminate the costly “duplication of [delivery] routes by milk companies,” whereby some half-dozen different vendors, as Weegee so dutifully chronicled, might deliver to a single shop on a single day at great and needless expense in “tires and gasoline” (). The remedy was to be these deliveries’ rotation, so that different dairies served different shops on different days, obviating the daily retreading of routes. Of the proposed fix, Dairy King’s proprietor, Hyman Linkoffsky, held a balanced view: “customers mightn’t like the idea of being forced to take a brand they were unaccustomed to … But it’s a war [on] … and I don’t think it would be too much of a sacrifice. After all, milk is milk”.

Figure 1.

Arnold Beichman and Weegee. “One of the ‘Frills’ That Make Milk Cost You More”, PM, 10 January 1943. Image courtesy of the International Center of Photography.

If we might take routine civil disturbance to be Weegee’s news beat, here was a modest if potentially osteoporotic one newly triggered by an aggravated old redundancy in milk delivery routes. On this occasion Weegee had been charged by editors not with picturing sensational urban mayhem (as we might expect) but instead with the compelling visualization of a markedly subtle distribution inefficiency operating just below the threshold of routine visibility: a blip in the optical white noise of metropolitan life.

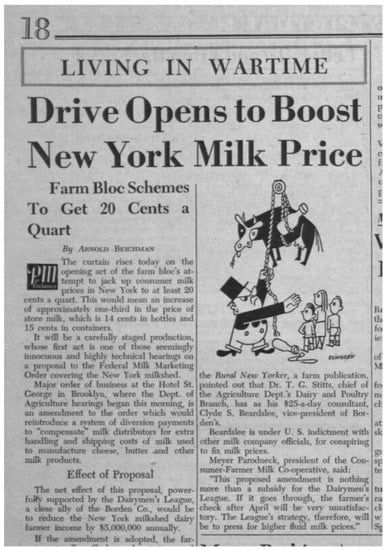

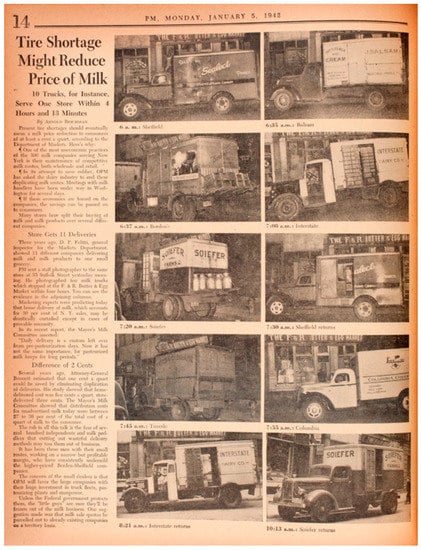

Such was pictorial newsgathering on the local beat in wartime, at least in the pages of Weegee’s principal journalistic gig, PM, which dedicated at least as much ink to disturbances in the local economy as it did to those of criminal violence, national politics, and global war.2 To wit, and to stay with milk for a moment: six days later Weegee’s colleague at PM, Ad Reinhardt, published a cartoon accompanying Beichman’s reporting on the farm bloc mechanisms affecting the point-of-sale price spike at issue. His picture: a robber baron in overalls and top hat hoisting milk and cow up and out of reach of growing children by rope and pulley (Figure 2) (). Milk economy for PM was no passing concern. Two full years before, for the edition of 5 January 1941, an unnamed PM photographer (perhaps Weegee, more likely not), again on assignment with Beichman, set the template for Weegee’s later feature, this time capturing, between 06:00 and 10:00, no fewer than ten dairy trucks belonging to seven distinct vendors, all pictured delivering to the F&R Butter and Egg Market at 35 Suffolk St. in Manhattan (Figure 3) ().3 In the weeks just after Pearl Harbor, the Department of Markets, Beichman reports, had observed a potential boon to milk consumers in the new wartime rationing of rubber, a material deemed more urgently essential to war mobilization than to domestic commerce. Fewer tires for milk trucks would necessitate a laissez-faire reduction in the same kind of delivery inefficiencies Weegee and Beichman inventoried two year later. At play here, again, are the low-visibility technics of a home front city in wartime made to run on the inhibited flow of soft and slippery streams of gasoline, money, milk, and rubber. How to picture such a thing? Amusing and peculiar as this liquid pictorial preoccupation may now seem, it is well worth registering the logic of PM’s tendency in its careful visual description of the hard economics and blunt material infrastructure channelling the city’s essential—if otherwise barely visible—fortifying streams. Infrastructure is and was, so writes John Durham Peters, “in most cases demure. Withdrawal is its modus operandi” (). It is good that a newspaper should restore it to visibility.

Figure 2.

Arnold Beichman and Ad Reinhardt, “Drive Opens to Boost New York’s Milk Price”, PM, 16 March 1942. Image created by the author.

Figure 3.

Arnold Beichman and unnamed photographer, “Tire Shortage Might Reduce Price of Milk”, PM, 5 January 1942. Image Courtesy of the International Center of Photography.

2. Weegee as Bystander

Weegee’s Dairy King sequence, all-but-unpeopled and drab in its informational formal program, registers imperfectly with “street photography” as it has been defined by critics and historians as a genre. Weegee figures importantly within that descriptor’s conjured field, and so we can measure the deviation from its standards with some precision. More an art historical category than a field of practice, “street photography” can, as Abigail Solomon-Godeau recently observed, be reasonably said to originate with the publication of Colin Westerbeck and Joel Meyerowitz’s 1994 survey, Bystander: A History of Street Photography (). For Westerbeck and Meyerowitz, writing in the early 1990s and at a moment of judicious caution concerning the veridical purchase of the documentary image, “street photography”, as a genre, compels and coheres principally in its registration not of the truth of the city but, more modestly, of the character of the medium’s own photographicness, quite as the dynamic sociality of the city might best announce it. “It is a kind of photography”, they write, “that tells us something crucial about the nature of the medium as a whole, about what is unique to the imagery that it produces”. Formally, instantaneity and multiplicity are its key terms, while fragmentation and motion blur emerge as prized genre attributes. “Errant details, chance juxtapositions, odd non sequitors, peculiarities of scale”—these are the qualities of the “candid pictures of everyday life in the street” that permit street photography its art historical identity (). The city street, the authors contend, engenders these effects and the good street photographer gathers and arrays them in prints as pictures. The notion of the city as a good and ready subject, lying in wait for the observant photographer, remains an article of faith in the art historical presentation of street photography as a genre. Russell Ferguson expressed it well: “The city offers itself as ready-made composition, constantly forming new patterns, an endlessly regenerating trove of pictorial opportunity” (). Weegee’s “success” as a “street photographer” obtains, according to this logic, less in his professional aptitude as a newspaper journalist on the beat, with his pictures subject to professional protocol and infrastructural constraint, than in his transcendently artful receptivity to the unpredictable dynamics of light as it bounced from Speed Graphic to city subject and back again: “he shot in the dark, seldom being able to predict what, if anything, he would get”, Westerbeck writes (Westerbeck and Meyerowitz, p. 335).

Weegee’s formal intelligence is exactingly observed in Bystander’s account, as in its author’s smart discussion of one thrilling 1944 picture, identified and dated there as Accident Victim in Shock of 1940 (Figure 4). This tightly framed photograph relates the scene of a police man reaching his hand through the window of an automobile, where it is met by the touch of a woman who has just killed another motorist in an accident: her terrified eyes possess the picture. With their gloss, Bystander’s authors help free us from those eyes’s grip so that we might better observe Weegee’s passive mastery of light, as it beams or fails to beam or splits through glass and steel. “[A] reliance on blind chance to get some of his most effective pictures is obvious in those he had to take through car windows at the scenes of accidents”, the authors write; “He could never be sure whether the flash would bounce off the glass or go through it, or where the reflections and shadows would fall” (Westerbeck and Meyerowitz, p. 335). Weegee’s flashburst, we are helped to see, shines flawlessly through a windshield to offer a sharp, bright view of the terrified woman in her horror; that same flash light is interrupted by the car’s frame to cast an evocative amputating shadow between a policeman and an accidental killer (“the severed hand serves as an image of both the car crash itself and her own disconnection from it at this moment”). Lastly, this light bounces from a police man’s cheek to only half pass through the skewed glass of an open quarter-window, reflecting his fragmented profile back at us. Light and shadow and internal frames and high human drama and affect dance and mingle to conjure an almost impossibly satisfying picture, taken, we are told, virtually by accident (Westerbeck and Meyerowitz, p. 336).

Figure 4.

Weegee, [Police officer talking to Dorothy Reportella after she crashed into a truck, New York], 7 September 1944. © Weegee/International Center of Photography (165.1982).

All value obtains, according to this model, in the insular dynamics of black box, operator, and the evocative subject before its lens, in a closed, aestheticizing system. But the formulation neglects too much of what is meaningfully modern of this photographer’s work—its attention to and membership among the dynamic systems (human and machine) that ionize cities and set them humming.4 This quality is at least as well revealed in photographs as apparently inert as those of the milk trucks outside a Brooklyn Dairy King. A much more expansive notion of street photography will be needed should that nomenclature hope to contain any adequate framework for taking this (and any) professional press photographer’s full measure—and it must, for who, after all, but press photographers have so fully chronicled the modern city in pictures? Abigail Solomon-Godeau has recently decried the interpretive limits coded into the genre’s invention as an “art historical category”, with its outsized emphasis on authorship and style.5 To this indictment add Martha Rosler’s rejection of this mode’s practical “nonresponsibility” toward its nominally extra-aesthetic subject, its “loss of specificity … as its empties information from the image” in the service of the art world’s desired “aestheticization and universalization”, such as we tend to see in conventional discussions of Weegee’s work, where nary a thought is given to the human substance of the news it made, let alone to the procedural or informational texture of its routine journalistic function (). 6 Informed by the revised photographic ontologies of Vilém Flusser and Ariella Azoulay, who insist, each in their way, that photography be understood to analytically contain the fuller technical and psychic infrastructures upon which its functioning depends and into which its image production is inevitably enfolded, much recent scholarship better weaves street photography’s images into the tangled systems of their pictured worlds (; ). Catherine Clark, addressing the commercial variant of the photofilmeur and the postwar French legal structures they troubled, argues explicitly against Bystander’s passive-aggressive register, to insist that “we must reframe the street photographer as a participant in—not a bystander to—the social world” (). Krista Thompson has considered commercial street portrait photography in the United States and Jamaica in terms of the complex social dynamics present in the production of the image over and above the pictorial logic of the image itself (). Likewise, Katherine Bussard and Jennifer Tucker have respectively insisted that street photography be understood as a visual field of the most acute political contestation: a site of constraint and resistance and of surveillance and counter-surveillance (). Tucker compels us to push past the criteria of both aestheticism and “concerned” documentary, to ask of this genre “not only what do the photographs show or discover about urban streets, but how did the politics and social construction of … mobility shape photographic narratives of urban life, and therefore what social meanings and structures do they inflect?” ().7 Tucker here denaturalizes the city’s essential dynamism—its circulatory logic, its fundamental mobility—and so offers a complex sense of documentary’s revelatory potential. Here we are rightly called upon to attend to street photography’s wider expository power—as a participant apparatus woven through the social relations that its images can only too partially mirror, and quite precisely as these relations are governed by kindred technologies of freedom and control. Street photography so re-imagined might thereby emerge as a kind of urban dye test, a bright and sensitive chemistry pumped through a city’s variably operative vital systems—its infrastructure, hard and soft, wet and dry. This will be an infrastructuralist encounter with street photography, one that indulges a fascination, as infrastructuralism must, with “the basic, the boring, the mundane, and all the mischievous work done behind the scenes” ().8

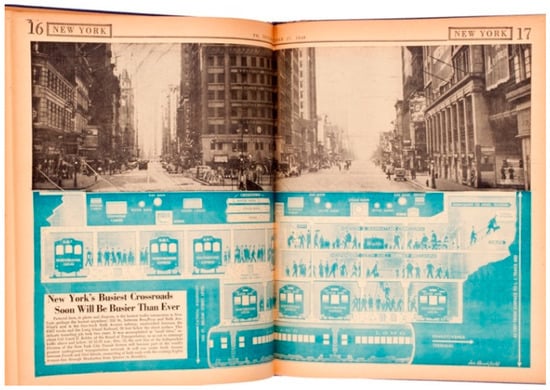

We opened on an encounter with Weegee’s surprising commitment to an analysis of urban dairy infrastructure (as it braids into concerns of federal agricultural policy, global war, and their attending petroleum economies), so to mark his attachment to systems such as these. If kids at rough play in wartime will make for street photography a good subject, we might give a thought to the mechanisms inhibiting their access to calcium. The remainder of this essay will track this attachment further, to consider other dimensions of this photography’s embeddedness into the city’s varied systems of conveyance and transmission. The dairy industry held no monopoly on the paper’s infrastructural pictorial attention: Weegee’s PM milieu was one committed to the rigorous pictorial relation of the conditions of New York City’s otherwise subliminal operating structures as these shaped its readers’ daily lives. Consider staff cartoonist Leo Herschfield’s remarkable, hybrid two-page urban cross-section of “New York’s Busiest Crossroads”, published by the paper 17 October 1940 (Figure 5) (). Here panoramic photograph and substructural diagram combine to excavate no newsy incident—the intersection, at 33rd between Broadway and Sixth, seems to defy the headline by its conspicuous calm—but rather the quieter noise of stacked and braided infrastructure, like a tree as 60′ deep as it is six stories tall, all laid out in an anatomy to true and careful scale. What passes for news here: with the completion of the four-track Sixth Avenue subway route, “sandwiched between the BMT tracks and the Long Island Railroad, 50 feet below the street surface”, New York’s “busiest crossroads” would soon be “busier than ever”. So much ado here but not much to see, at least not for the street-level press photographer on the hunt for incident.

Figure 5.

Leo Hershfield, “New York’s Busiest Crossroads Soon Will Be Busier Than Ever”, PM, 17 October 1940. Image courtesy of the International Center of Photography.

Herschfield’s blue surveyor’s ink unearths the action in the complex dance of pipes and wires and bodies and electrified rails that hum beneath the streets: Edison electric cables and telephone cables; mains for water, gas, steam, and sewage; subway cars and railroad cars, all these media stack and lattice in a carefully managed uptown-downtown/crosstown tangle. Here the living dynamics of the city are shown to unfold as much in the weave of men and women and sewage and drinking water and natural gas and telephony and electricity as they ever could in the taut sociality of the sidewalk traffic, such as some street photographer might trap in a flash for a picture. Hershfield’s is a sanguine vision of Lewis Mumford’s rued modern “megatechnics”, with their “translation of all organic processes, biological functions, and human aptitudes into a … mechanical system”. He expresses the layered city as a medium, a communicative machine, quite as Friedrich Kittler positioned it: “a network made up of intersecting networks dissects and connects the city. Regardless of whether these networks transmit information (telephone, radio …), or energy (water supply, electricity, highway [here subway]), they all represent forms of information” (; ). PM and Hershfield grasp that the newsy business of New York’s busiest crossroads exceeds street-photographic capturability by braiding the transit of solids, gasses, and liquids (including the essential amalgam: people) with the transmission by wire of energy and information: these are dynamic channels that would so busily intersect here.9

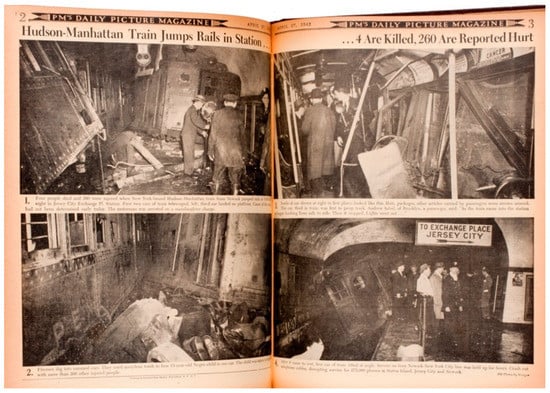

While famously a Chevy driver disinclined toward subway travel, Weegee, in his service to this newspaper, did have vocational occasion to visit Herschfield’s vivid subterranean pathways. PM’s edition of Monday, 27 April 1942 published as its second and third pages the photographer’s reporting on a deadly subway wreck: an especially tragic disturbance to this complex system’s otherwise smooth communicative function. Four dark, dense, and difficult pictures; all scenes of twisted steel and mud and confusion and rescue, all made late the night before (Figure 6) (). The first picture, with the bad joke of its obviated two-bulbed signal at centre top, interrupts the underground darkness to reveal police establishing a chaotic and mangled scene. An instant’s Speed Graphic flash belies the truer condition of an underground lightlessness to be mitigated only by the setting up of a strong lamp, a measure apparently only just then introduced—Weegee, we can surmise, was among the first to arrive to the emergency. That first picture’s caption relates the scope of the disaster: “Four people died and 260 were injured when New York-bound Hudson-Manhattan train from Newark jumped the rails … First two cars of train telescoped, left; third car landed on platform. Cause of crash had not been determined early today.” In explanation of the inscrutably muddy second picture, we find mention of another bright technology applied to good end: “Fireman dig into rammed cars. They used acetylene torch to free 13-year-old Negro child in one car. The child was taken to hospital with more than 200 injured people”.10 The third picture, page opposite, offers a view of investigators aboard a subway car, as they investigate and record with camera and flash. Attending the fourth and final picture, Weegee and PM conclude with an uncanny view from the platform of a charred car askew as it scraped to a stop at the station, like a signal jammed. Its caption literalizes the media analogy: “Crash cut telephone cables, disrupting service for 275,000 phones in Staten Island, Jersey City, and Newark”. The reporter’s deep slice pulls up news of injury and death and heroic rescue; but also the surrounding substance of communicative disruption: calamitous breakdown of the underground’s otherwise smoothly blended communications and transit pathways run through by trains and wires and telephony and the bright but informationally-muted signals of reporters, cops, and firemen with their flash bulbs and lamps and acetylene torches.

Figure 6.

Weegee, “Hudson–Manhattan Train Jumps Rails in Station”, PM, 27 April 1942. Image courtesy of the International Center of Photography.

If the city is a medium, journalists take an interest where the medium fails. “Miscommunication”, Peters writes, “is the scandal that motivates the very concept of communication in the first place” (). Peters urges us to restore to the concept of communication its root associations with material transfer and conveyance, including both locomotive and electronic transmission. “Technologies such as the telegraph and radio refitted the old term ‘communication’, once used for any kind of physical transfer or transmission, into a new kind of quasi-physical connection across the obstacles of space and time” ().11 Weegee and Hershfield anachronistically but helpfully remarry these divorced meanings to articulate the city as not just fit for eventful journalistic remediation in words and pictures, but as itself a primary media structure within which the journalistic image is but one of many intersecting and coterminous signals. In a crisis Weegee and PM both record and, along the way, contribute to the subway wreck as expressly an illuminating failure in a complex subterranean communicative media network otherwise resistant to photographic capture.12

3. Weegee, Standing By

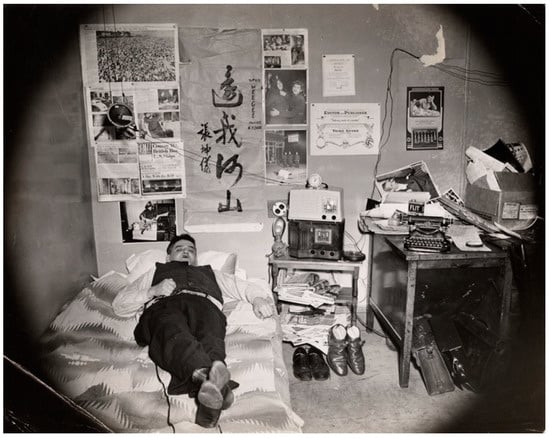

Weegee made it his business to insert himself into just these kinds of urban circulatory systems so to register them in their malfunction, as news. He did this in an important self-portrait taken for PM, and published as part of a long, celebratory 9 March 1941 feature on the photographer written by staff photography columnist Ralph Steiner. Weegee stages himself quite exactly as a relay—as a decisive point in a system of electronic transmission (Figure 7). He lays on his bed, soles of his feet to the camera, surrounded by the paraphernalia of the news trade. A lateral scan of the picture yields one order of evidence: old newspapers, a press award, clippings, a typewriter, a clock, a calendar, radios, various footwear differently designated for distinct working conditions: “’murder shoes’ … and his ‘snow shows’ (). He keeps his ‘fires shoes’ in the car”, according to the caption. But rereading the picture from near to far, along the axis of the photographer’s body, we discover a new vector of evidence: the wire of the shutter release as it extends from the camera that takes the picture and inward toward Weegee’s hand, where it reaches for another wire above, passing from one of Weegee’s two stacked radios. It is fitting that this other wire should be harder to see: “On top of his regular radio”, Steiner explains, “is a police short-wave radio and a loudspeaker attached to it dangles over his head”. Weegee offers himself in this carefully staged picture, as existing, amid wires, at the intersection of photography and radio, as a relay between these distinct but competing high-speed information delivery systems, where he translates the information passed from the invisible, sonic medium of the former, with only modest delay, into the pictorial but silent medium of the latter. From this intermediate station, Weegee taps into the city’s variably material circulatory systems and media pathways. Some such systems, as we have seen, carried (or notably lapsed in their carriage of) milk, or subway cars, or telephone calls, or some combination of these. These forgotten pictures of milk trucks and derailments found their audience among readers for whom such messages bore present and practical purchase: a nutritious beverage too costly, a commute delayed, a phone line down, a friend or neighbour hurt or even killed.

Figure 7.

Weegee, [Weegee lying on bed in his studio, New York], 1941. © Weegee/International Center of Photography (2215.1993).

Weegee’s chroniclers have gleaned considerable insight into this photographer and his moment in photography’s history by reference to the self-portrait just described, especially in its membership to an evolving sequence of similar portraits taken by Weegee over the preceding half decade or so.13 Brian Wallis, not least among them, has noted this sequence’s privileging of photographic equipment and the broader cultural and technological apparatus into which this equipment was embedded (). For Wallis, these pictures speak to Weegee’s situatedness within a moment of pronounced technological change within the profession of press photography, beginning in the early of the 1930s. His compelling inventory includes the introduction the General Electric synchronized flashbulb around 1930, the national proliferation of Wirephoto transmission capability by the Associated Press agency beginning in 1935, and the Graflex Speed Graphic camera, which became the industry standard during these same years. The impact of this trifecta on pictorial journalism can hardly be overstated, and in their union these photographic resources radically expedited press photography’s promise of swift and sharp registration and distribution of the news in pictures, at any time of day or night.14 But why limit the constituents of Weegee’s favoured medium, “photography”, to cameras, flashes, and image-distributions channels?15 What of those other new urban media of newsgathering so central to the performance of Weegee task? What of the police radio itself, whose noisy squawks and chirps he so skilfully recoded as pictures?16 “I had the place wired so that I could pick up police signals right from the radio dispatcher”, the photographer recalls in his memoir (). Might we consider Weegee’s photographs of street level urban disturbances pictorial indices of the police’s all-pervasive but otherwise unrecorded and unseen electromagnetic and sonic infrastructure? Of “the ‘sonic city’—the city of radio waves”, and its artefacts, media historian Shannon Mattern lately asks, “How does one dig into a form of mediation that seemingly has no physical form?” (). Weegee and PM offer one answer.

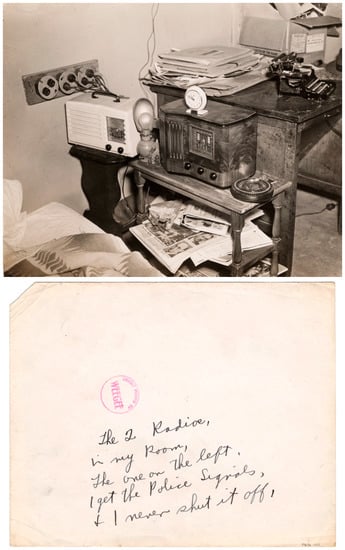

An undated photograph stored among the Weegee Archive at the International Center of Photography, probably taken at about the same time as the self-portrait described above, establishes the radio’s catalytic role within this photographer’s picture-making apparatus. (Figure 8). This photographic tribute to a craftsman’s tool carries a useful description on its back: “The 2 radios, in my room, the on the left, I get the police signals, and I never shut it off,”. The inscriptions ends with a comma: like the radio itself, the recipient of this message must remain speculative, and the message will always be cut short. Weegee has rearranged his radios for this loving portrait. Where they were stacked for the fuller view discussed above, now they are arrayed and set into a kind of orderly and meaningful sequence of electrical and broadcast inputs and outputs woven among media of light and time. A wall socket draws from the Edison grid to deliver power to an Emerson 414 Bakelite set, tuned and brusquely customized for short wave, which draws upon another, now wireless network, police station WPEG (on 2450 kilocycles) with its small, targeted audience of professionals and amateurs.17 This information stream yields in turn, pictorially, to the public broadcast logic of the neighbouring, polished wood Emerson CS-272 consumer tabletop set, where, for example, an emergency call for green radio cars picked up on the Bakelite set might, after some small delay and expedient journalistic processing, be enjoyed in its remediated sonic form, as news.18 Nestled between and stacked upon these points in the information stream are the twinned photographic light/time proxies of lamp and clock, like flash bulb and shutter. In his own responsive activation of Bakelite and flash bulb Weegee will produce the pictures whose “broadcast” (in print) will follow soon after, on the surfaces of new newspapers whose exhausted precursors surround this wired array. It is an assembly resonant with the procedural logic of Weegee’s routine newsgathering operation.

Figure 8.

Weegee, [Police radio in Weegee’s room, New York], recto and verso, ca. 1941. © Weegee/International Center of Photography (19632.1993).

We might safely hazard that the better part of Weegee’s photographs of the freshly dead and injured, made after about 1940, including those photographs for which he has long been best known, are inextricable from and fully a function of the then-still-nascent technology of police radio, which started to augment New York’s telephonic call box and telegraphic teletype systems only in 1932—a strong new strand of the city’s layered media environment.19 It was an excellent news gathering tool. Even where Weegee had and would continue to make use of the earlier teletype system, radio carried considerable built-in advantage. As Jo Ranson, radio editor for the Brooklyn Eagle, where PM handled its printing in its early years, reported in 1937, “only messages of prime importance are handled by radio motor patrolmen. The extensive teletype and telephone systems are used for the transmission of information concerning minor crimes or where a long interval has elapsed between the commission and reporting of a crime” (). The radio was thus not only the fastest path to “live” urban disturbances as they unfolded, precisely as these might be designated by police, but, by privileging only those most urgent crises, it automated the editor’s task, self-selecting assignments for the most news-photogenic incident.

In PM’s pages, Weegee, a journalist invested with considerable editorial agency and never one to shy from showcasing his own “mischievous work done behind the scenes,” frequently amplified police radio’s centrality to his own provision of news pictures. A 30 July 1941 photograph, sometimes called “My Man,” and of some renown at least since its accession into the collection of the Museum of Modern Art already in 1943, might appear (taken in isolation, as a print) as an invasive meditation on loss (Figure 9). As PM presented it, the picture resumes its originary multivalence; as vivid, local news of senseless and sudden violence, to be sure, but also as a reflexive meditation on the very media-infrastructural conditions (of radios, roads, and cameras) allowing that same news’ shocking, radical proximity—in time and place—to the awful trouble at hand (Figure 10). As compelled by efficiency and by his Speed Graphic’s preset focal length, Weegee shot his subject from his customary distance of six to ten feet: an astonishing nearness to such a scene—a woman only just discovering that her husband has been badly shot (he may die), her privacy invaded by the rough reach of cop. Weegee’s flash carries with it something of the unwelcome intimacy of the policeman’s grab. But the terms of that proximity were structured as much by tools for the focusing and transmission of sound as of light—as much by radio and antenna as by optics and lens. “[C]hances are that the layman doesn’t realize these things”, so noted G.A. Murray, of Western Electric, the firm outfitting the New York Police Department with its radios at the time, “he probably still pictures only the catch and is oblivious to the part played by extensive radio … networks in localizing the criminal [incident’s] whereabouts” (). Weegee, this report underscores, responded to the very same police dispatcher’s call that beckoned the pictured “catch”. A correction to the condition of public ignorance alleged by Murray, Weegee opens his own brief narrative account of the affair, published in a text block above his three pictures, this way:

Shortly after 3 o’clock this morning … the dreaded Signal 30 came over the police radio. (That signal means a crime has been committed; and the radio cops, when they arrive on the location, have their guns drawn and ready for action). The address was on West Street at W. 12th Street. I got there in a hurry.()

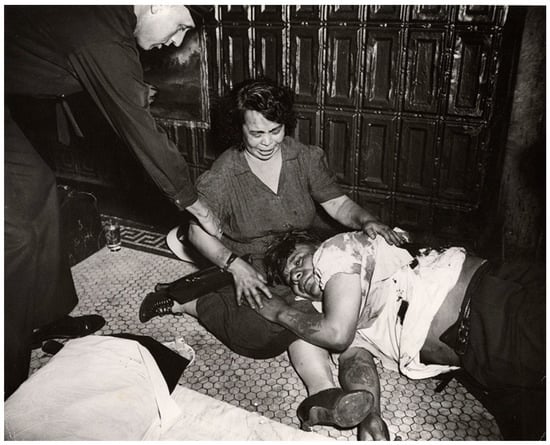

Figure 9.

Weegee, [Manuel Jiminez lies wounded in the lap of Manuelda Hernandez, New York], July 29, 1941. © Weegee/International Center of Photography (163.1982).

Figure 10.

Weegee, “Weegee Covers: A Waterfront Shooting”, PM, 30 July 1941. Image courtesy of the International Center of Photography.

Details of the violence follow, but the plain emphasis here is on the tangled protocols of radiophonic policing and radiophonic journalism in press-photographic production. While the spectacle of human drama does all it might to bury the media-infrastructural lede, PM and Weegee conspire as author and publisher to restore that latter, invisible concern, police radio, to the pictorial foreground.20

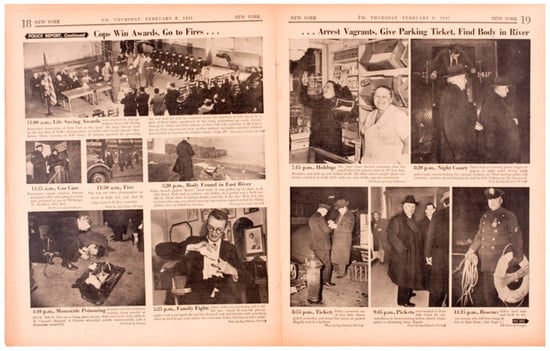

An earlier, more comprehensive, five-page press-photographic immersion into NYPD business, published six months before, had prepared readers to see police pictures by the radio’s light: a “picture story of a New York day—23 hours in the world’s biggest city as its policemen see it” (). Entitled “Police Report”, here PM’s city editor mapped newspaper labour onto the structure of police labour, charging fully sixteen of its photographers “and a staff of reporters”, to replicate that shift work, so to answer “police calls from 12:15 Wednesday morning till 11:15 last night”. Photographs by Irving Haberman, Alan Fisher, Leo Leib, Ray Platnick, and Weegee, among others, detail the modest drama of car thefts, drunkenness, vandalism, and domestic disputes: “The dullest night I can remember”, according to one officer. Following an opening page detailing an ongoing murder investigation, a three-page sequence yields a single day’s newsgathering time as it ticks off across seventeen pictures: “12:15 a.m., Stolen Hearse”; “3:30 a.m., Drunk”; “6:30 a.m., Broken Window”; “5:25 p.m., Family Fight”, and so on, each accompanied by a brief if atmospheric caption. Leo Leib’s entry for 3:20 p.m., “Body Found in East River” is representative. A tightly cropped swath of diminished photographic visibility, perhaps an inch high and an inch and half across on the page, reveals a windswept policeman as he stands over the freshly discovered corpse (Figure 11). The blunt caption: “Police launch spotted ‘floater’—dead body. It was pulled up on shore at E. 12th Street. Body had on rubbers, old clothes. In a pocket was a birth certificate. There were 11 natural deaths yesterday: 10 in bed, one in street. One man was found starving; one woman injured in bed by falling plaster; one cop killed by streetcar”. This caption’s airless density conspires with its picture’s tight cropping to crack the smallest window into the dangerous tedium of police work, and, in the same gesture, to express something of the journalist’s own tightly delimited expository capabilities in its orbit.

Figure 11.

“Police Report”, PM, 6 February 1941. Image courtesy of the International Center of Photography.

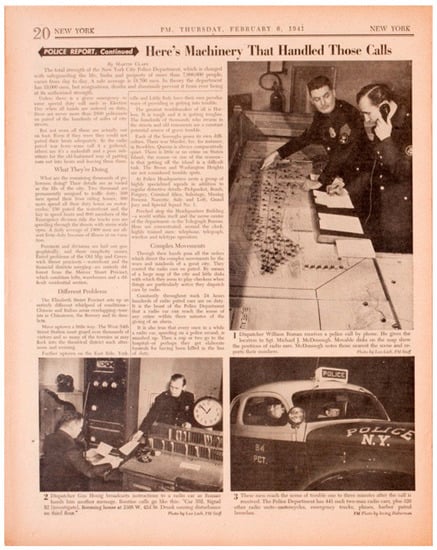

The final page of “Police Report” foregrounds the mechanism by which twenty-three hours’ of city-wide police work, involving some “2800 policemen on patrol of the hundreds of miles of city streets” could be coordinated (Figure 12). “Perched atop the Headquarters Building—a world within itself and the nerve center of the department—is the Telegraph Bureau. Here are concentrated, around the clock, highly trained men: telephone, telegraph, wireless and teletype operators”. Here PM pulls back the operational curtain on the preceding pages’s yield, and by extension on the methods of routine provision of photographic police reporting, to relate both the full organizational complexity of modern urban policing and the means by which that complexity is managed:

Through [the Telegraph Bureau] pass all the orders which direct the complex movements by the woes and misdeeds of a great city. They control the radio cars on patrol. By means of large map of the city and little disks with which they seem to play checkers when things are particularly active they dispatch cars by radio. Constantly throughout each 24 h hundreds of radio patrol cars are on duty. It is the boast of the Police Department that a radio car can reach the scene of any crime within three minutes of the giving of an alarm.()

Figure 12.

“Police Report: Here’s the Machinery That Handled Those Calls”, PM, 6 February 1941. Image courtesy of the International Center of Photography.

Here we discover police cars as checkers in a radio game played by Telegraph Bureau dispatchers and tracked by photographers, Weegee unique among them (so he claimed), in his possession of a licensed automotive police radio. The text is accompanied by a sequence of three photographs relating the unfolding of this procedure at three points along an eventful communicative pathway whose end is the translation of incident, telephonically described, into the arrival of police and their police cars on the scene. The first picture (“1”, by Leo Leib, figures the interposition of police between telephone and map as they recode, from their position over Telegraph Bureau’s “U-Map” of the city, a telephoned report of some urban disturbance into a point of proximity to an available radio car. Dispatcher William Roman conveys a location to Sgt. Michael J. McDonough, who locates the incident, and so the pertinent grid sector, on the map, in order to identify nearby and available units; these marked on the map by small numbered discs. We might note that McDonough seems to point to Harlem in Lieb’s picture; a neighbourhood left otherwise (now conspicuously) unphotographed in the report. In their radiophonic collaboration with New York’s police, PM’s cameras were only willing to chase the dispatcher’s discs so far uptown.21

An account for a 1936 essay by the New York City Police’s Chief Engineer, Thomas Rochester, published in the radio enthusiast magazine Pickups, relates the Telegraph Bureau’s technique with striking clarity that merits extended quotation, if only for its value in explaining the media-infrastructural basis of so much modern crime scene photography. The procedure was this:

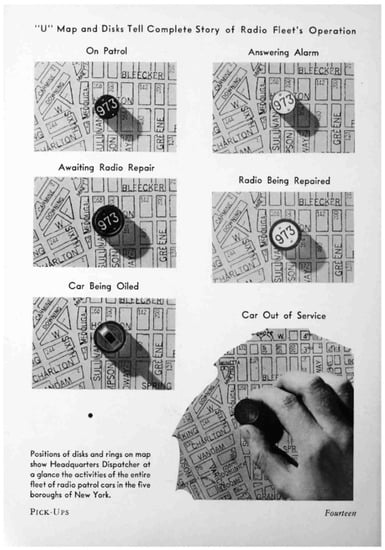

Two men are on duty. One sits before a map mounted on a large “U” shaped table that is covered with glass. He is the dispatcher and the director of a fleet of radio patrol cars which cruise the streets of the five boroughs. To him the cars are black disks spotted over the map. Each disc is numbered. On one side the numerals appear in white designating that the car is ready for action. Red numbers on the reverse side indicated that the car is not available for the call. The second man, the announcer, is stationed before a microphone. A few feet away stands a radio transmitter, now dark and silent … Suddenly the stillness is broken by the tinkle of a telephone bell … The dispatcher takes the receiver. The announcer flips a switch at the microphone. Tubes flash blue as the plate current surges through the transmitter circuits. And police radio goes into action. Is it a robbery, assault, kidnaping, murder that is setting the great network of communication in motion? The dispatcher’s expression tells you nothing. As he takes the call his eyes are on the map noting the location of the scene where the crime has been committed. He jots down the message and ‘923’ and ‘864’—cars assigned to the job—then turns paper over to the announcer. Disks 923 and 864 are turned with red letters showing, indication that these cars are busy. Meanwhile the announcer has sent out the call to attention—a 1000 cycle note lasting three seconds. Every car in the fleet hears it and stands ready. “Calling cars 923 and 864—the address is 142 Bleecker Street, Manhattan, signal 31—station WBEG—tie 1:45 p.m.—No. 60”, says the announcer … Quickly, calmly, efficiently, the tower room has sent out its message. The scene switches to Bleeker Street. Here noise and confusion are rampant. An excited crowd is milling around the little cigar store at No. 142. Within 45 seconds from the time the alarm winged over the air car 923 is at the scene and 864 half a block away … While excitement reigned at Bleeker Street the dispatcher has been busy with his map.()

Chief Rochester describes the electronic remediation of human incident into data: “Is it a robbery, assault, kidnaping, murder that is setting the great network of communication in motion? The dispatcher’s expression tells you nothing.” Red and black discs will be manipulated on a grid (Figure 13), whose coordinates, announced by shortwave radio, will be swiftly tracked by police—and by newspaper photographers. This is the city remade by police and reporters as what Peters calls logistical media, and “the job of logistical media is to organize and orient, to arrange people and property, often into grids” ().22 This grid Weegee navigated as much by radio as by car. And here we gain entry into one of those technologies identified by Stuart Hall and his colleagues in their 1978 study of the pernicious dynamics of law enforcement and the press, whereby an “exceedingly limited circle of mutual reciprocities and re-enforcements” advances the collaborative construction by police and journalists of civilian norms and their policeable deviations ().

Figure 13.

Thomas W. Rochester, “How New York Police Radio System Patrols 317 Square Mile Area”, Pick-Ups, February 1936. Image created by the author.

Returning to that last page of our PM “Police Report”, with its journalistic performance of Rochester’s system, the second picture by Leib (“2”) relates that phase in this communicative process whereby details of a given incident are transmitted via radio to the appropriate radio patrol cars. The invisible process behind the news becomes the news, and the elusive technologies of telephone, map, and red/black disc substitute for journalistically trackable technologies of clock, radio, and car. The caption reports: “Routine calls go like this: “Car 552. Signal 32 [Investigate]. Rooming house at 2308 W. 42nd St. Drunk causing disturbance on third floor”. The third and last photograph in the sequence (“3”), by Irving Haberman, suggests, in its tight portrayal of watchful police in their green and white radio car, the successful receipt of the radioed message and the prompt delivery of perceptive and able police to the scene. What was recoded as information in the service of speedy policing is wholly restored for Haberman to the iconography of human events. Cumulatively PM offers a tidy and efficient circuit here, rendering modern policing as information logistics. Crime fighting and emergency response manifest as both functions of and conditional upon the deft management of time and space by telecommunications. The press photographer eavesdrops and then looks.

We might consider by this measure the photograph that appeared on this edition’s first page, to announce the “Police Report” within (Figure 14): a police rescue picture by Weegee, PM’s star, whose caption anticipates the telecommunicative emphasis of the “Police Report”’s conclusion:

Rescued from the River: This woman is shocked with cold. The husky cops carrying her have just hauled her form the East River and she’s on her way to the hospital. She is Ann Sullivan, 50, and she fell overboard last night from the barge Henry McNamee, tied up at Pier 9. A radio alarm brought the cops to pull her out with a boat hook. Police were unable to learn her address or occupation.()

Figure 14.

Weegee, “23 Hours With New York Police … 5 Pages of Pictures”, PM, 6 February 1941. Image courtesy of the International Center of Photography.

A middle-aged white woman of no particular address or occupation and so of no special station commands the picture’s centre, where she hangs cradled in the hands of the four fast acting police who have saved her from the sure death of February East River waters. This unremarkable picture braids the image of timely and competent policework with the evidence, embedded invisibly into the fact of its own making as a picture, of competent news camera work. Police officer and cameraman encircle the subject in the double embrace of warm safety and blinding flash. A woman is saved, and a picture is made as if in the same gesture and by virtue of the accelerated response afforded by the still novel technology of police radio, to which Weegee listened as keenly and responsively as did the police he pictures—the latter no doubt pleased with the good press.

We might then fairly reimagine Weegee as the press photographer as radio artist, a photographic registrar of signalled disturbances in Hertzian space, tapping in to the police department’s realtime radiophonic grid.23 “All that radio is”, John Cage once remarked to his friend Morton Feldman, “is making audible something which you’re already in. You are bathed in radio waves” (, quoted in ; ).24 The twist: Weegee made the policeman’s electromagnetic bath not audible, but in an array of chemically stabilized light bursts, visible as well. Look again, to end, at Bystander’s Accident Victim in Shock, and at its resonant play of light and shadow and reflection and bodies across apertures and planes (Figure 4). We might reconsider that pictures’s shadowy point of contact between a policeman and an accidental killer, which so interested Bystander’s observant authors. But we might see that shadowy spot now not only as “an image of both the car crash itself and [the drivers] own disconnection from it as this moment”, as Bystander reckons it, but also as the invisible radiophonic centre from which radiates the signal that will summon the necessary players here—the suspect, the police man, the photographer—as if centrifugally, so that they can gather tightly enough in one place, for a moment, to allow us this picture. Radio waves join light waves as they pass and refract through cut glass.

Funding

This article was written with the support of a General University Research Grant from the University of Delaware.

Acknowledgments

Many sincere thanks to Stephanie Schwartz and to my two anonymous readers at Arts. Thanks to Mariola Alvarez, Tiffany Barber, Jessica Horton, Erin Pauwels, Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, and Delia Solomons for their tremendously helpful comments on an early presentation of this argument. Thanks too to Claartje Van Dijk at the ICP.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Azoulay, Ariella. 2012. Civil Imagination: A Political Ontology of Photography. Brooklyn: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Battles, Kathleen. 2010. Calling All Cars: Radio Dragnets and the Technology of Policing. Minneapolis: Minnesota. [Google Scholar]

- Beichman, Arnold, and Ad Reinhardt. 1942. Drive Opens to Boost New York’s Milk Price. PM, March 16, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Beichman, Arnold, and Weegee. 1943. One of the ‘Frills’ That Make Milk Cost You More. PM, January 10, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Beichman, Arnold, and unnamed photographer. 1942. Tire Shortage Might Reduce Price of Milk. PM, January 5, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanos, Christopher. 2018. Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous. New York: Henry Holt. [Google Scholar]

- Rrougher, Kerry, and Russell Ferguson. 2001. Open City: Street Photographs Since 1950. Oxford: MOMA. [Google Scholar]

- Bussard, Katherine A. 2014. Unfamiliar Streets: The Photographs of Richard Avedon, Charles Moore, Martha Rosler, and Philip-Lorca DiCorcia. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cage, John, and Morton Feldman. 1993. Radio Happenings: Conversations/Gespräche. Cologne: MusikTexte. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, James. 1988. Technology and Ideology: The Case of the Telegraph. In Communication as Culture: Essays on Media and Society. New York: Unwin-Hyman, pp. 201–30. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Catherine. 2017. The Commercial Street Photographer: The Right to the Street and the Droit à l’Image in Post-1945 France. Journal of Visual Culture 16: 225–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, Anthony, and Fiona Raby. 2001. Design Noir: The Secret Life of Electronic Objects. Basel: Birkhaüser. [Google Scholar]

- Flint, Kate. 2017. Flash!: Photography, Writing, and Surprising Illumination. New York: Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Flusser, Vilém. 2005. Towards a Philosophy of Photography. London: Reaktion. [Google Scholar]

- Galtung, Johan, and Mari Ruge. 1988. Structuring and Selecting News. In The Manufacture of News: Deviance, Social Problems & The Mass Media. Edited by Stanley Cohen and Jock Young. London: Constable, pp. 52–63. First published 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Gursel, Zeynep. 2015. A Short History of Wire Service Photography. In Getting the Picture: The Visual Culture of the News. Edited by Jason E. Hill and Vanessa R. Schwartz. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 206–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Stuart, Chas Critcher, Tony Jefferson, John Clarke, and Brian Roberts. 1978. Policing the Crisis: Mugging, The State and Law and Order. London: MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Hauptman, Jodi. 1998. FLASH! The Speed Graphic Camera. Yale Journal of Criticism 11: 129–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershfield, Leo. 1940. New York’s Busiest Crossroads Soon Will Be Busier Than Ever. PM, October 17, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Jason. 2018. Artist as Reporter: Weegee, Ad Reinhardt, and the PM News Picture. Oakland: University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, Douglas. 2011. Electrical Atmospheres. In Invisible Fields: Geographies of Radio Waves. Barcelona: Arts Santa Mònica. [Google Scholar]

- Kittler, Friedrich. ; Translated by Matthew Griffin. 1996. The City is a Medium. New Literary History 27: 717–29. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Anthony, and Richard Meyers, eds. 2008. Weegee and Naked City. Los Angeles: University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Leonardi, Nicoletta, and Simone Natale, eds. 2018. Photography and Other Media in the Nineteenth Century. College Park: Penn State. [Google Scholar]

- Luis de Vicente, Jose, and Honor Harger. 2011. There, but Invisible: Exploring the Contours of ‘Invisible Fields’. In Invisible Fields: Geographies of Radio Waves. Barcelona: Arts Santa Mònica. [Google Scholar]

- Luis de Vicente, José, Honor Harger, and Josep Perelló, eds. 2011. Invisible Fields: Geographies of Radio Waves. Barcelona: Arts Santa Mònica. [Google Scholar]

- Mattern, Shannon. 2015. Deep Mapping the Media City. Minneapolis: Minnesota. [Google Scholar]

- Mattern, Shannon. 2017. Code and Clay, Data and Dirt: Five Thousand Years of Urban Media. Minneapolis: Minnesota. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Richard. 2007. Learning from Low Culture. In Weegee and Naked City. Edited by Anthony Lee and Richard Meyer. Los Angeles: Univ. of California. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford, Lewis. 1966. Technics and the Nature of Man. Technology and Culture 7: 303–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, Lisa, and Nicole Starosielski, eds. 2015. Signal Traffic: Critical Studies of Media Infrastructure. Urbana: University of Illinois. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, Andrea G. 1990. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper and Harper’s Weekly: Innovation and Imitation in Nineteenth-Century American Pictorial Reporting. Journal of Popular Culture 23: 81–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, John Durham. 1999. Speaking into the Air: A History of the Idea of Communication. Chicago: University of Chicago, pp. 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, John Durham. 2015. The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Police Report. 1941. Police Report. PM, February 6, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ranson, Jo. 1937. Cops on the Air. Brooklyn: Eagle Library. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Duane. 1945. ‘Mugging’ and the New York Press. Phylon 6: 169–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochester, Thomas W. 1936. How New York Police Radio System Patrols 317 Square Mile Area. Pick-Ups, February. 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Rosler, Martha. 2004. Post-Documentary, Post-Photography [1999]. In Decoys and Disruptions: Selected Writings, 1945–2001. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, Vanessa R. 2017. Networks: Technology, Mobility, and Mediation in Visual Culture. American Art 31: 104–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegert, Bernhard. 2015. Cultural Techniques: Grids, Filters, Doors, and Other Articulations of the Real. New York: Fordham. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon-Godeau, Abigail. 2007. Ontology, Essences, and Photography’s Aesthetics: Wringing the Goose’s Neck One More Time. In Photography Theory. Edited by James Elkins. New York: Routledge, pp. 256–69. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon-Godeau, Abigail. 2017. Harry Callahan: Gender, Genre, and Street Photography. In Abigail Solomon-Godeau. Photography after Photography: Gender, Genre, and History. Edited by Sarah Parsons. Durham: Duke University Press Books, pp. 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, Ralph, and Weegee. 1941. Weegee Lives for His Work and Thinks Before Shooting. PM, March 9, 50–1. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Krista. 2015. Shine: The Visual Economy of Light in African Diasporic Aesthetic Practice. Durham: Duke University Press Books. [Google Scholar]

- Trachtenberg, Alan. 2010. Weegee’s City Secrets. E-rea: Revue électronique d’études sur le monde anglophone 7. Available online: http://journals.openedition.org/erea/1168 (accessed on 13 May 2019). [CrossRef]

- Tucker, Jennifer. 2012. Eyes on the Street: Photography in Urban Public Spaces. Radical History Review 114: 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallis, Brian. 2012. Becoming Weegee. In Weegee: Murder is My Business. Edited by idem. New York: International Center of Photography. [Google Scholar]

- Weegee. 1941a. Weegee Covers: A Waterfront Shooting. PM, July 30, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Weegee. 1941b. 23 Hours With New York Police … 5 Pages of Pictures. PM, February 6, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Weegee. 1942. Hudson-Manhattan Train Jumps Rails in Station. PM, April 27, 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Weegee. 1944. Death Strikes a Driver at Dawn. PM, September 7, 16–7. [Google Scholar]

- Weegee. 1961. Weegee by Weegee. New York: Ziff-Davis. [Google Scholar]

- Westerbeck, Colin, and Joel Meyerowitz. 1994. Bystander: A History of Street Photography. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Wigoder, Meir. 2001. Some Thoughts on Street Photography and the Everyday. History of Photography 25: 368–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Rosalind. 2008. Notes on Underground: An Essay on Technology, Society, and the Imagination. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zelizer, Barbie. 1995. Journalism’s ‘Last’ Stand: Wirephoto and the Discourse of Resistance. Journal of Communication 45.2: 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Weegee, a pioneer in local news photography since the late 1930s, made his name as a photographer at PM between 1940 and 1944, before securing national renown as the author of the 1945 book Naked City, which compiled a selection of his work from PM and other papers. See () and (). |

| 2 | On PM more broadly, see Paul Milkman, PM: A New Deal in Journalism (New Brunswick: Rutgers, 1997), and Jason E. Hill, Artist as Reporter: Weegee, Ad Reinhardt, and the PM News Picture (Oakland: California, 2018). |

| 3 | The geography of milk takes its place in the history of the illustrated press in New York City. For one important, earlier chapter, see (). |

| 4 | Vanessa Schwartz has recently argued for the importance of studying mass media’s networked “techno-aesthetics”, so much better to place “the human-machine continuum at the center of inquiry”. See (). |

| 5 | On this genre’s distinctly shaky definitional footing, and Bystander’s chronologically privileged position in its generic articulation, see (). en passim. To Solomon-Godeau’s recognition, add Mark Wigoder’s: “So much has already been written about street photography that one tends to forget that there is no definite and absolute definition of the topic” (). |

| 6 | Accident Victim, as offered here, jettisons concern for the time, place, and texture of the reporting to which such a picture, as a newspaper picture, belongs. This one emerged not in 1940, but only much later, for PM’s edition of 7 September 1944, as part of shared, earnest, and extended commitment by its photographer and publisher to reporting on the very serious dangers of automobility in New York City (). I consider the art/journalism dichotomy, as it pertains to Weegee’s photographic project, at length in (). |

| 7 | Emphasis added. |

| 8 | Peters develops his “doctrine of infrastructuralism” as an interpretive “doctrine of environments and small differences, of strait gates and the needles eye, of things not understood that stand under our worlds,” (). See also (). |

| 9 | On the city as an expression and accretion of media and otherwise communicative infrastructure, see (). Also, (). |

| 10 | Deviating from PM’s own editorial protocol, which typically avoided racializing identifiers where they were not germane to the substance of the reporting, this caption’s author (possibly Weegee) determined that the race of the rescued child ought to be among the facts dug out from under the wreckage. |

| 11 | “In the nineteenth century United States”, Peters notes, “‘steam communication’ could mean the railroad”. (). On the telegraphic separation of communication from transportation, see (). |

| 12 | On photography and media infrastructure, see (). |

| 13 | See, for example, (). |

| 14 | On the adjoining of flash and Speed Graphic, see, most recently, (). On Weegee and flash, see, in addition to Flint, (; ). On AP Wirephoto and its impact on visual journalism, see () and (). |

| 15 | Here I follow Abigail Solomon-Godeau’s demand (echoing Tagg and Flusser) that we expand our understanding of photography’s proper ontological limits as a medium: “[A]ny conceptual thinking on photography require[s] that we consider all those elements…that exceed the camera, the individual picture, and the individual photographer … [T]his includes the entire social, spatial, temporal, and phenomenological context in which these technological forms are variously viewed and received; the psychic determinations by which modes of spectatorial identification and projection are secured; and, not least, the industrial…structures that underwrite, shape, manufacture, and disseminate them.” From this wide and necessary menu, the present essay follows only one relatively selective path of inquiry. See her important (). |

| 16 | Weegee’s Chevy, which was itself famously outfitted with a radio, will be the subject of another essay. |

| 17 | Concerning Weegee’s customization of the Emerson Bakelite set, note that the top half of the dial on the white has been scraped clean of printed station markers. In a recent exchange with the author on Instagram, SF MoMA Curatorial Assistant Matt Kluk observes: “The top half was for “Broadcast,” or AM band. The bottom half was shortwave, which various police departments (including the NYPD) seem to have used until the end of WWII. So, maybe just his way of designating that the radio was only to be used for shortwave listening?” Recall the additional customization of the loud speaker which Weegee wired up from this radio to hang over his bed. For a detailed account of the logistics prewar police radio in New York, see (). Also see (). |

| 18 | The CS-272 had short wave as well as broadcast capability, but Weegee used this one for music. Thanks to Matt Kluk, Chris George, and Chris Bonanos for their help identifying these Emerson sets. |

| 19 | One indicator of police radio’s lingering novelty at this moment: American City, a remarkable interwar American magazine targeted at municipal administrators and packed with news and notices of infrastructural matters (paving asphalt, street lights, fire hydrants, etc.), was rife in the early 1940s with slick advertisements pitching automotive police radio systems from the likes of Western Electric and Westinghouse. |

| 20 | An anecdote, likely apocryphal, shared in Ranson’s report on police radio of 1937, encourages such an interpretive reversal, whereby the police radio will be understood as a media infrastructure generative of content, rather than simply a trapping “dragnet” mechanism responsive to whatever incident might precede it. A Harlem man was caught robbing a grocery store. ‘The police radio car arrived on the scene just as the holdup man was about to step off the curb. “I’m perfectly satisfied”, he said as the cops nabbed him. “What are you satisfied about?” one of the officers inquired. “You are under arrest”, “I was just testing the efficiency of the radio cars’ (). |

| 21 | According to sociologist Duane Robinson, writing for W.E.B. DuBois’ journal Phylon in 1945, PM “criticized editorially the overemphasis [among New York newspapers] on Negro crime, pointed out the injustice in this overemphasis, and attempted, somewhat unevenly, to set an example of proper journalistic practice”. (). This position may or may not justify this feature’s failure to answer police radio calls issuing from Harlem. |

| 22 | Bernhard Siegert writes of the grid as a cultural technique whose purpose is the “‘enframing’ aimed at the availability and controllability of whatever is thus conceived; it addresses and symbolically manipulates things that have been transformed into data”. (). |

| 23 | On Hertizan space, see (). |

| 24 | In their introduction to the same volume, José Luis de Vicente and Honor Harger credit Kevin Slavin’s pertinent observation that the most compelling “work in this space ‘is not about making the invisible visible: it is about learning to work with the material of the invisible’”. (). |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).