Survival Research Laboratories: A Dystopian Industrial Performance Art

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Destruction, Survival, and Robotics

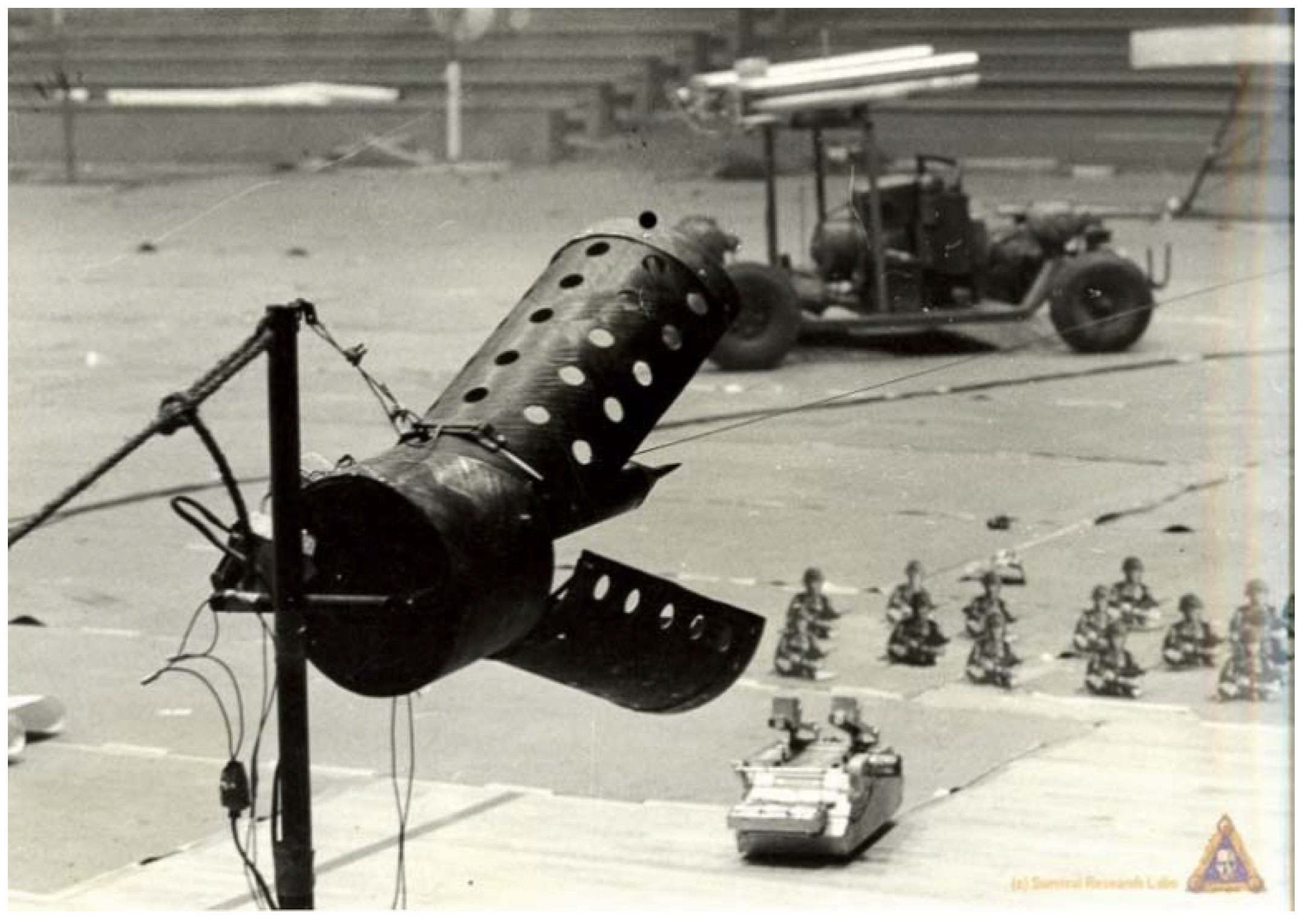

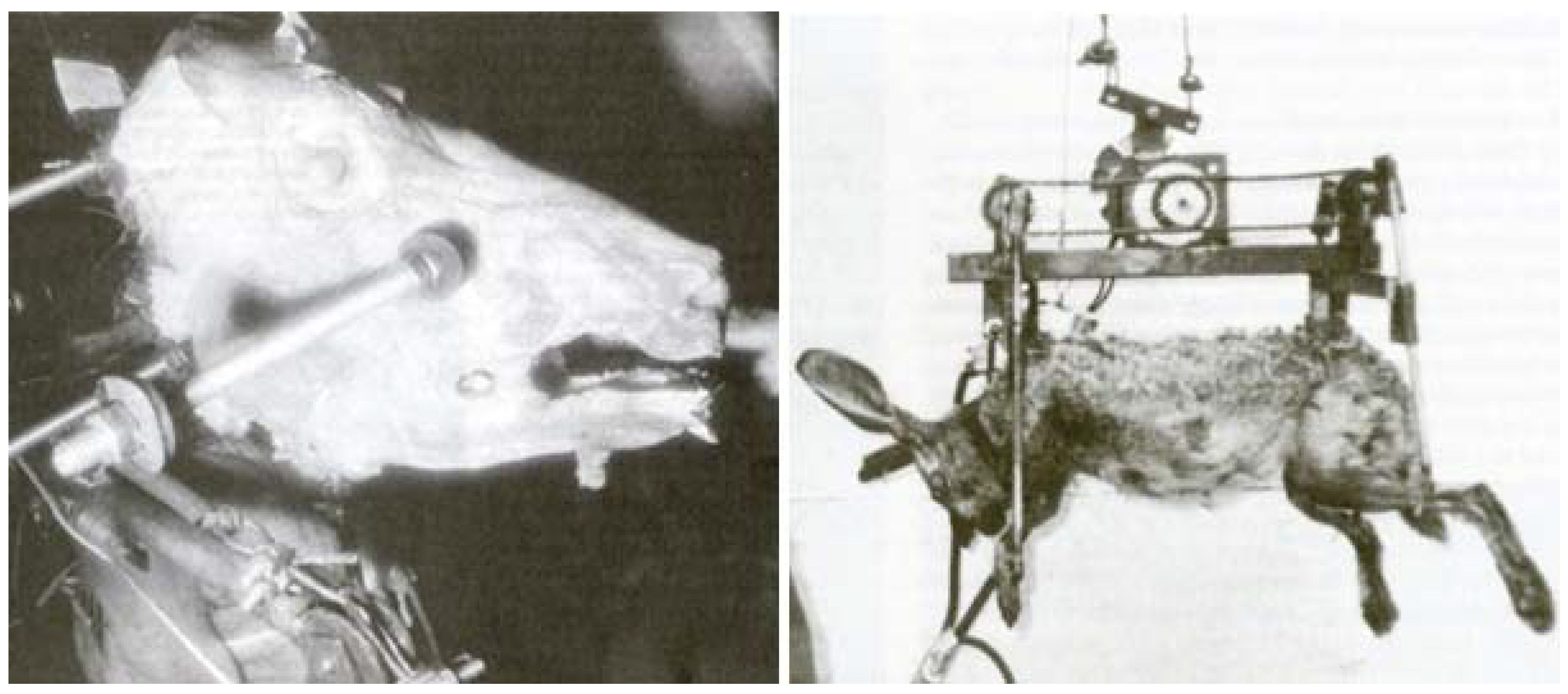

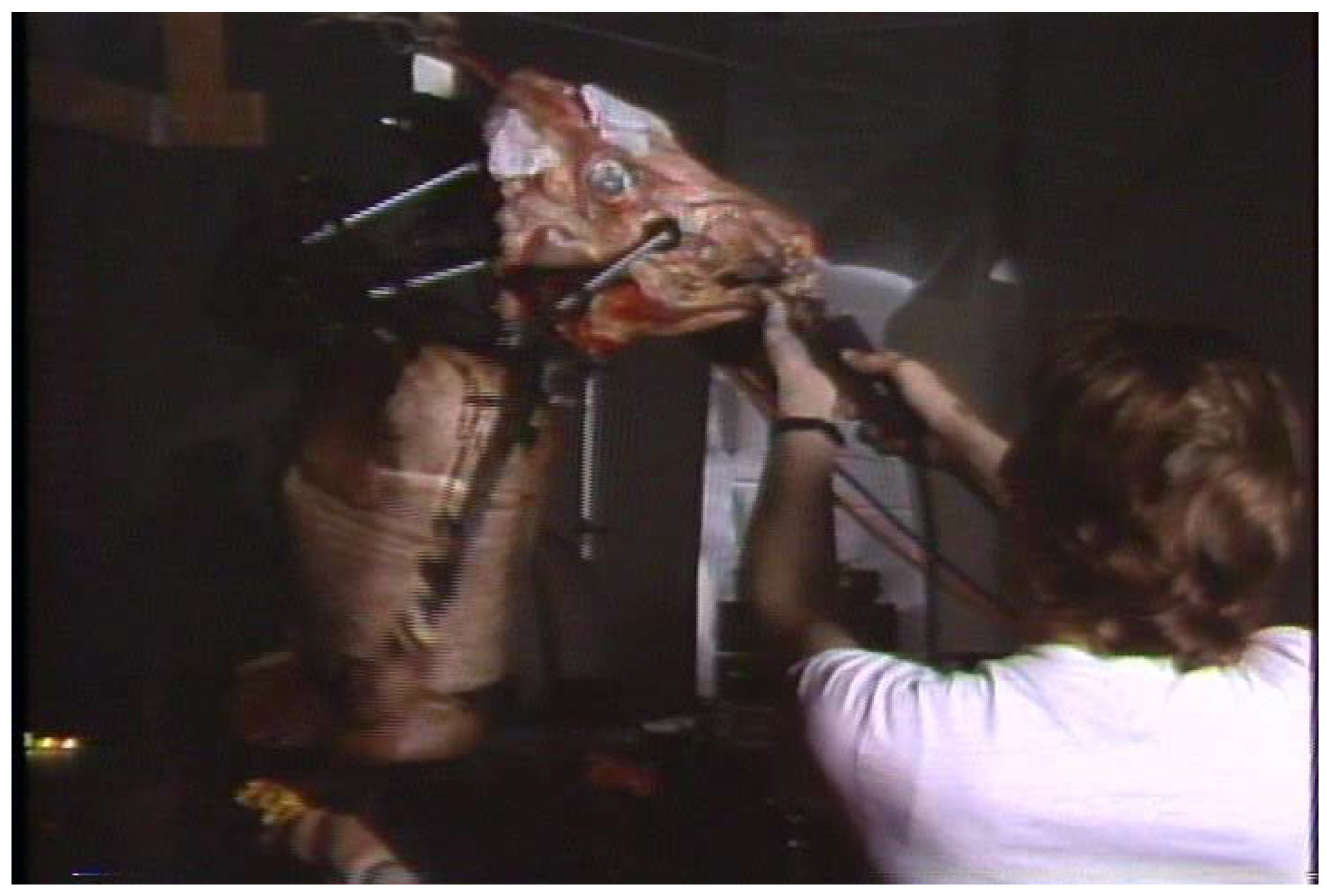

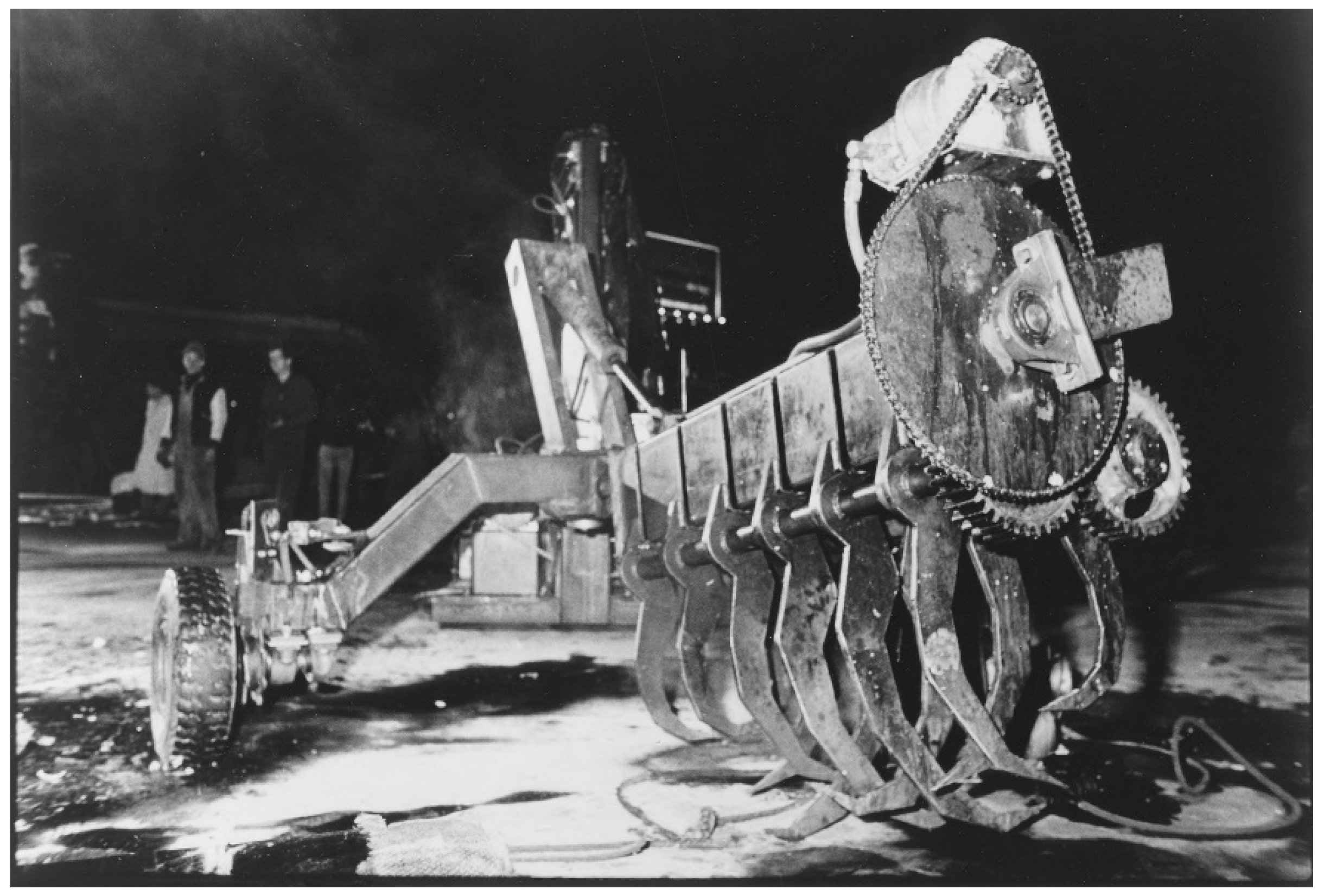

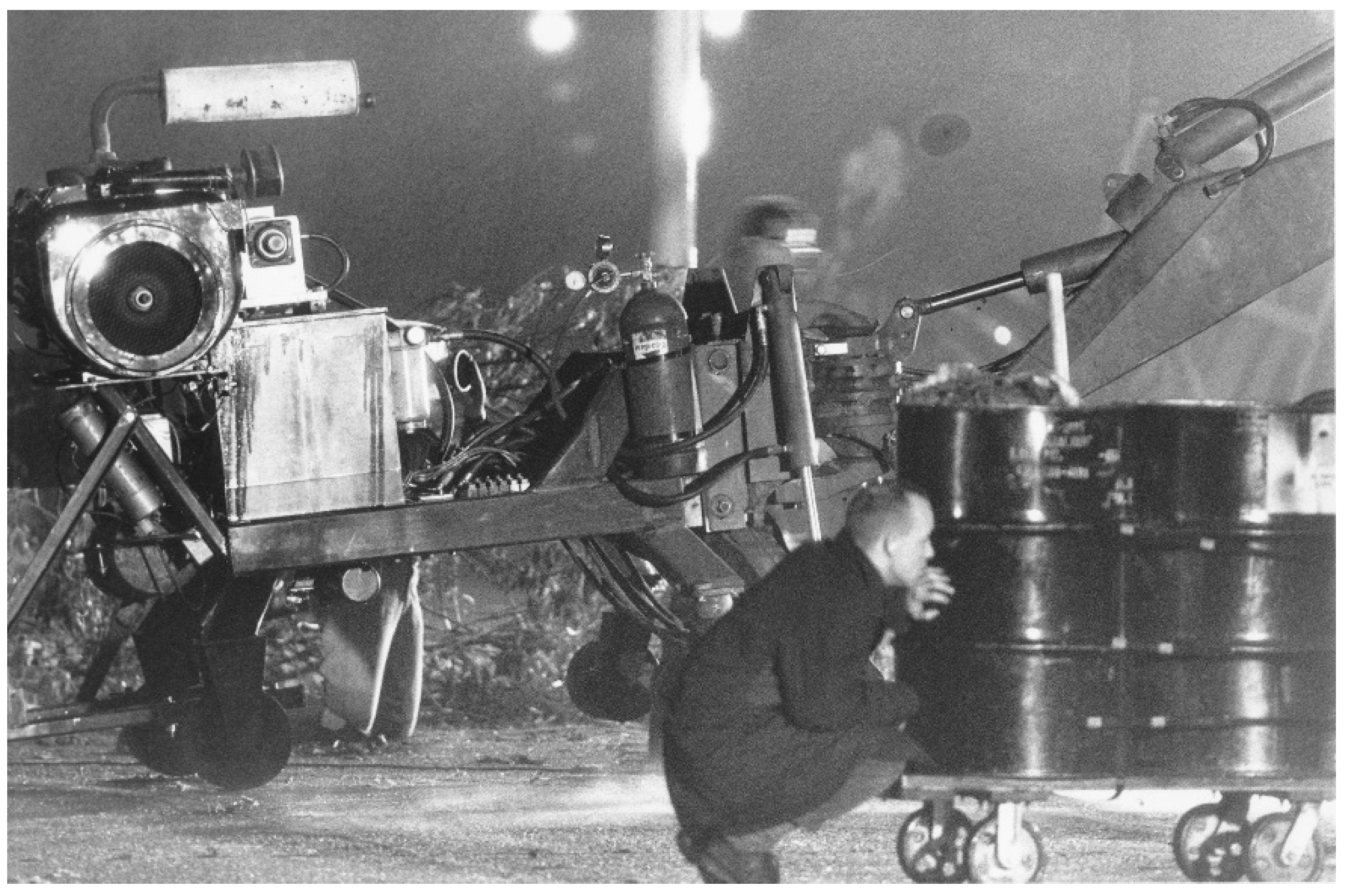

Certain kinds of presentational art forms have demonstrated a predisposition for and an ability to convey the ontological effects of the technology, phenomenology, and epistemology of destruction and the ways in which individuals and the collective negotiate the resulting crisis of survival. These performances and/or public events often feature advanced technology and/or use the body or body surrogates. Robots and other mechanized body substitutes sometimes serve as the aesthetic site for the representation of the conjunction of social and political practices and in interrelationships that collude in destruction.

3. Man-Amplified.10 The End of the Natural Body and Postmodern Cyborgs

4. Crash Biomechanical Sexual Hybridization

Ballard explores in perverse detail the twin leitmotifs of the 20th century: sex and paranoia. […] With a ruthless and sadistic/masochistic honesty, he “reduces the amount of fiction”, forcing us to come face to face with our own ambiguous attitudes. […] What we are forced to realize is that science has become equivalent to pornography in its aim of isolating objects analytically from their context in time and space. […] The obsessions are subjective—the only key in a world deprived of objectivity able to unlock the reality/fiction surrounding each of us.Graeme Revell16

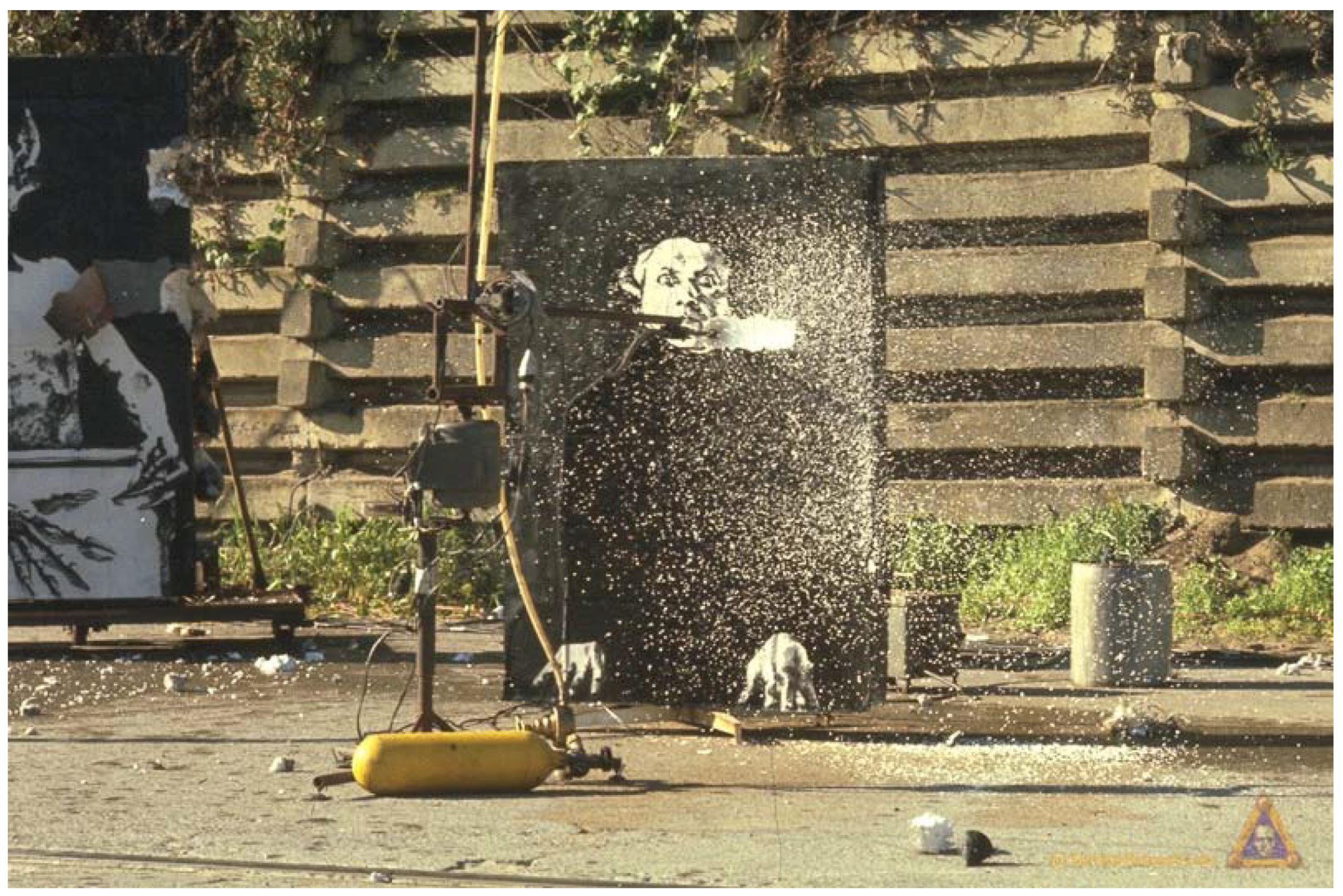

I’d been thinking all along that this should be a show about accidents. That’s kinda what it was about. There was a lot of equipment there that had accidents; a lot of equipment was destroyed. I tried to make sure that the things that were destroyed were as helpless as possible. Things were really tied down, roped up, like the big skeletal man, Flippy Man, that got hauled way up in the air and then crashed… and the robot thing whose heads kept blowing up… and the catapult firing at the huge face. Just all these things, like the guy getting hit in the head with a rock who tried to sue me… breaking the girl’s windshield with the ball-bearings that got thrown into the blower… accidents. I emptied a five-pound bag into this big blower; the bearings went past where people were and broke the windshield of a car.18

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allard, Laurence, Delphine Gardey, and Nathalie Magnan, eds. 2007. Donna Haraway, Manifeste Cyborg et Autres Essais: Sciences, Fictions, Féminismes. Paris: Exils Editeur, p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Alloway, Lawrence. 1956. Technologie et sexe dans la science-fiction. Note sur l’art de la couverture. In Art et Science-Fiction. La Ballard Connection. Edited by Valérie Mavridorakis. Geneva: MAMCO, pp. 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard, James Graham. 1968. Why I Want to Fuck Ronald Reagan. Brighton: Unicorn Bookshop. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard, James Graham. 1973. Crash. London: Jonathan Cape. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard, James Graham. 1984. What I Believe. In RE/Search #8/9: J. G. Ballard. Edited by V. Vale and Andrea Juno. San Francisco: RE/Search Publications, pp. 174–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ballet, Nicolas. 2017. Révolution bioélectronique. Les musiques industrielles sous influence burroughsienne. Les Cahiers du musée National d’art Moderne 140: 74–95. [Google Scholar]

- Baudrillard, Jean. 1990. La Transparence du Mal. Essai sur les Phénomènes Extrêmes. Paris: Éditions Galilée, p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- Biro, Matthew. 2009. The Dada Cyborg: Visions of the New Human in Weimar Berlin. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Celka, Marianne, and Bertrand Vidal. 2011. “Le futur, c’est maintenant”. L’imaginaire dystopique dans l’œuvre de James Graham Ballard. Sociétés 3: 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, Jordi, Rodrigo Fresán, Vicente Luis Mora, V. Vale, and Simon Sellars. 2008. J. G. Ballard. Autopsy of the New Millennium. [Exhibition catalog., Barcelona, Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona, 22 July–2 November 2008]. Barcelona: Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona. [Google Scholar]

- Duboys, Éric. 2009. Industrial Musics. Volume 1. Rosières-en-Haye: Camion Blanc. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel. 1976. Histoire de la Sexualité, vol. 1: La Volonté de Savoir, 2013th ed. Paris: Gallimard, p. 183. [Google Scholar]

- Gamboni, Dario. 1996. The Destruction of Art: Iconoclasm & Vandalism Since the French Revolution. London: Reaktion. [Google Scholar]

- Hattinger, Gottfried. 2014. L’artiste et le robot. Brève histoire d’une relation. In Robotic Art = Art Robotique. [Exhibition catalog., Paris, Cité des sciences et de l’industrie, 8 April 2014–4 January 2015]. Translation from the German by Valentine Meunier, in Olivier Carriguel (dir.). Paris: Art Book Magazine, pp. 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hello! Happy Taxpayers. 1985. No. 4/5 April. Bordeaux: Hello Happy Taxpayer.

- Hottois, Gilbert. 2012. Modernité et postmodernité dans l’imaginaire des sciences et techniques au xxe siècle. In L’idéologie du Progrès dans la Tourmente du Postmodernisme. [Conference proceedings 9–11 February 2012]. Edited by Valérie André, Jean-Pierre Contzen and Gilbert Hottois. Brussels: Académie royale de Belgique, p. 142. [Google Scholar]

- Hougue, Clémentine. 2014. Le Cut-Up de William S. Burroughs. Histoire d’une Révolution du Langage. Dijon: Les presses du réel, p. 357. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, Kevin. 1994. Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems and the Economic World. New York: Basic Books, p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- Kittler, Friedrich. 1995. Aufschreibesysteme 1800–1900, 3rd ed. Munich: Wilhelm Fink Verlag. First published 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Kittler, Friedrich. 1986. Grammophon Film Typewriter. Berlin: Brinkmann & Bose. [Google Scholar]

- Lyotard, Jean-François. 1977. Rudiments Païens. Genre Dissertatif, 2011th ed. Paris: Klincksieck, p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Mavridorakis, Valérie, ed. 2011. Is There a Life on Earth? La SF et l’art, passage transatlantique. In Art et Science-Fiction. La Ballard Connection. Geneva: MAMCO, pp. 9–44. [Google Scholar]

- Museum Tinguely. 2013. Museum Tinguely Basel: The Collection. Heidelberg: Kehrer Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Printz, Neil. 1988. Painting Death in America. In Andy Warhol: Death and Disasters. [Exhibition catalog, Houston, The Menil Collection, 21 October 1988–8 January 1989]. Directed by Walter Hopps. Houston: Houston Fine Art Press, pp. 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Queval, Isabelle. 2015. Corps humain. In Encyclopédie du Trans/Posthumanisme. L’humain et ses Préfixes. Directed by Gilbert Hottois, Jean-Noël Missa, and Laurence Perbal. Paris: Vrin, pp. 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Revell, Graeme. 1984. Essay on J. G. Ballard. In RE/Search #8/9: J. G. Ballard. Edited by V. Vale and Andrea Juno. San Francisco: RE/Search Publications, pp. 144–45. [Google Scholar]

- Sargeant, Jack. 1999. Cinema Contra Cinema. Berchem: Fringecore, p. 134. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Glenn. 2015. Swing Low, Sweet Chariot: Kinetic Sculpture and the Crisis of Western Technocentrism. Arts 4: 75–92. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0752/7/2/15 (accessed on 8 November 2018). [CrossRef]

- Stiles, Kristine. 1992. Selected Comments on Destruction Art. In Book for the Unstable Media. Edited by Alex Adriaansens, Joke Brouwer, Rik Delhaas and Eugenie den Uyl. Bois-le-Duc: Foundation V2, p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- Stiles, Kristine. 2016. Concerning Consequences. Studies in Art, Destruction, and Trauma. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Theweleit, Klaus. 1977. Fantasmâlgories. [Männerphantasien, 2016 Translation by Christophe Lucchese]. Paris: L’Arche, pp. 381–82. [Google Scholar]

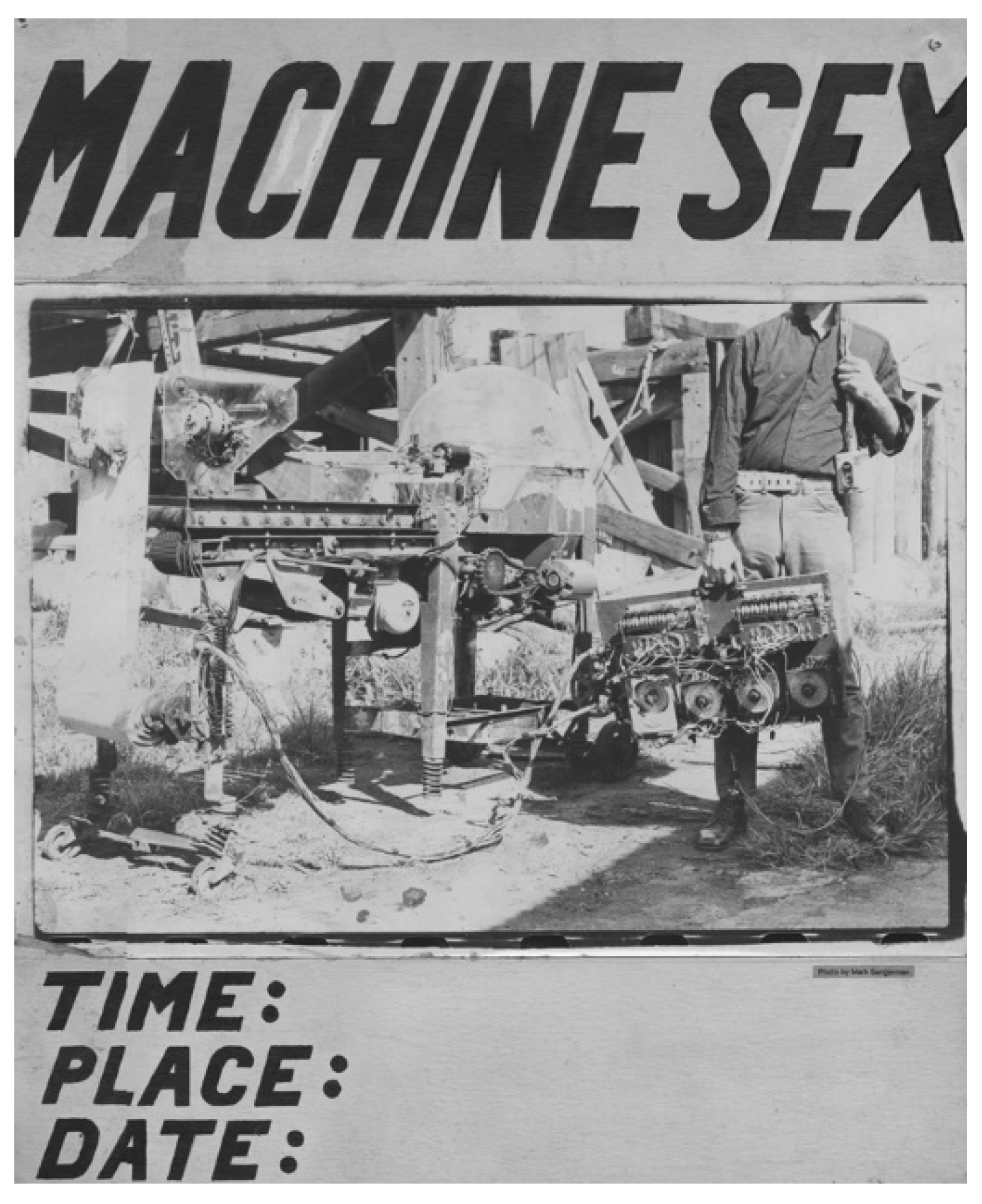

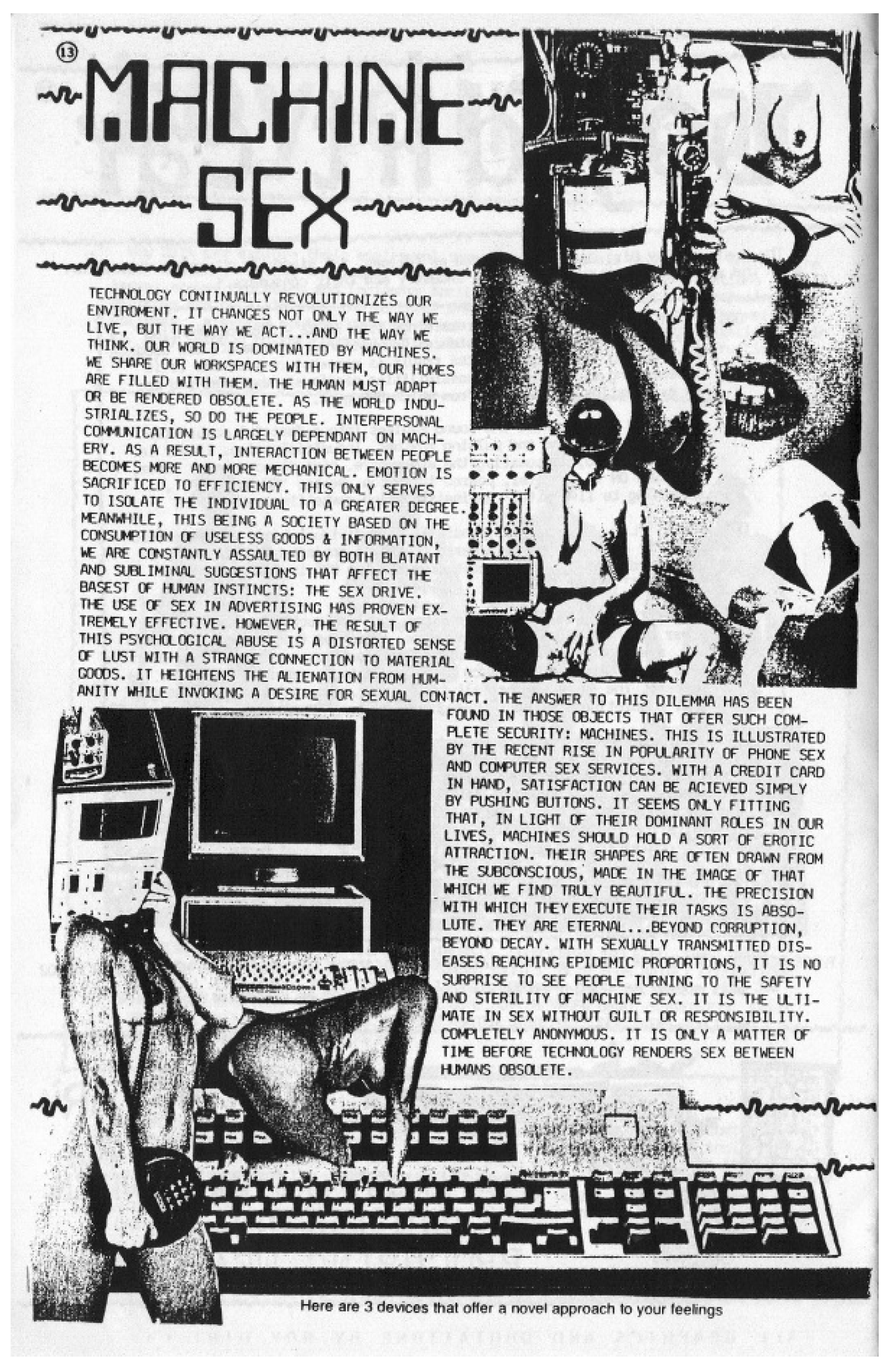

- Thorn, Thomas. 1985. Machine Sex. U-Bahn, No. 2. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Vale, V., and Andrea Juno, eds. 1983. RE/Search #6/7: Industrial Culture Handbook. San Francisco: Re/Search Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Vale, V., and Andrea Juno, eds. 1984. RE/Search #8/9: J. G. Ballard. San Francisco: RE/Search Publications. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | This new form of power was identified by the concept of biopolitics by Michel Foucault, who examined here the theoretical effects of the technology over the body (Foucault 1976). |

| 2 | From Concerning Consequences. Studies in Art, Destruction, and Trauma (Stiles 2016, p. 30). Stiles adds that “destruction art is the kind of performance art where conditions of human emergency are most vividly displayed” (Stiles 2016, p. 42). |

| 3 | For the link between consumerism and technology, see “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot: Kinetic Sculpture and the Crisis of Western Technocentrism”, wherein is documented the fact that a great portion of 20th century consumer goods were machines of some sort (Smith 2015). |

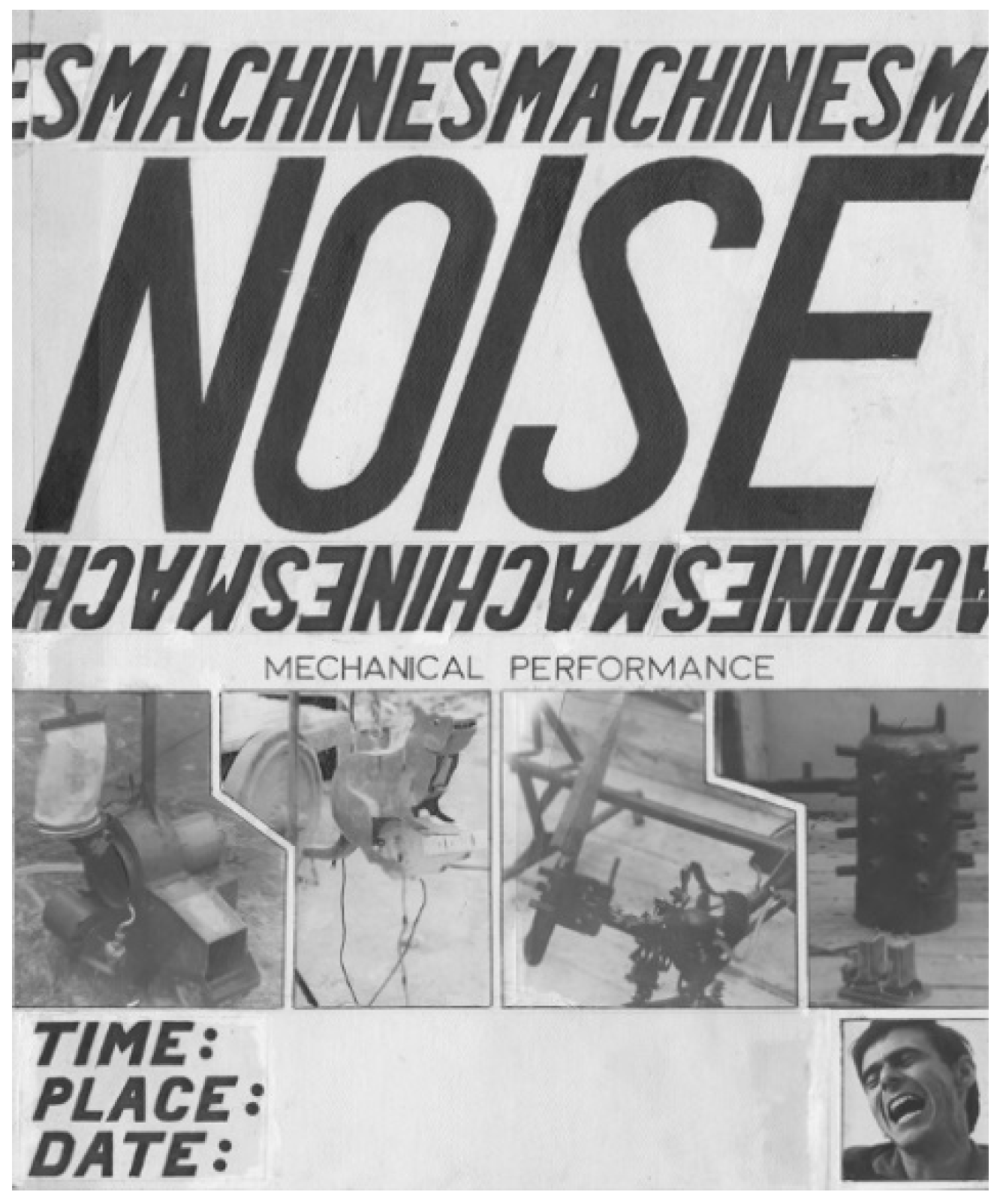

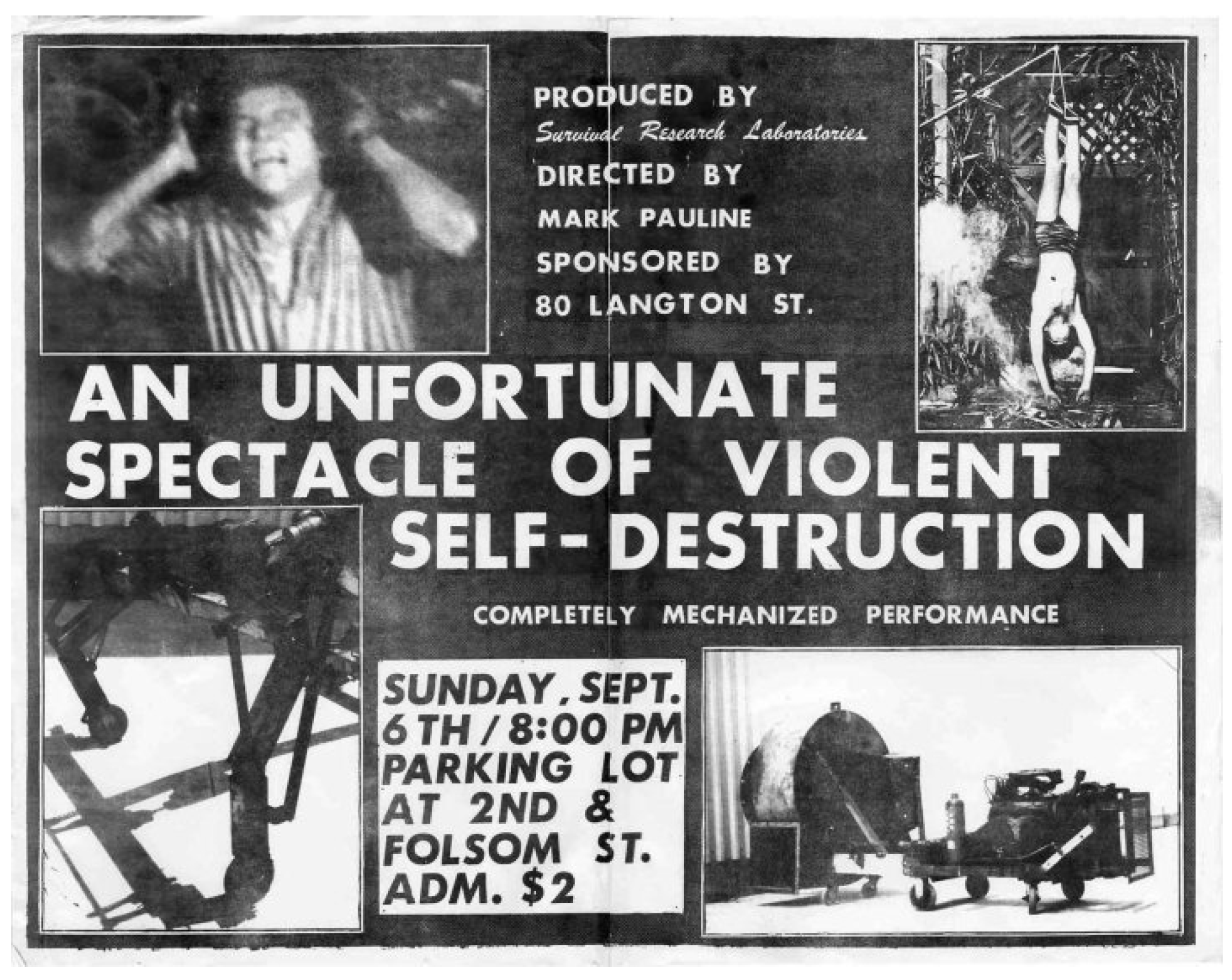

| 4 | Officially formed in 1978, the name of the collective—Survival Research Laboratories—stems from an advertisement published in the far-right magazine Soldier of Fortune. |

| 5 | As an example of the connection between industrial music and mechanical performance art of this kind, members of the British industrial band Throbbing Gristle were present for the occasion. Jean Tinguely, of course, had not only created in 1960 his self-destructing Homage to New York, but also, in 1962, had staged a series of explosions in the deserts of Nevada entitled Study for an End of the World No. 2 (Museum Tinguely 2013). |

| 6 | Mark Pauline as quoted in the Industrial Culture Handbook (Vale and Juno 1983, p. 27). |

| 7 | Among these, one has to mention Letters to Dad (1979) by Scott & Beth B. |

| 8 | The work Terrifying Scenes from The Battlefields of Tomorrow already showed these kinds of collaborations with interventions by Factrix, Monte Cazazza, Tana Emmolo and Cole Palme. |

| 9 | The performance was recorded on a VHS tape on the same year. Several excerpts from the video were used in the film True Gore (1987), directed by Matthew Dixon Causey and Monte Cazazza (credited as “creative consultant”). According to Jack Sargeant, True Gore is “a film which gleefully depicts what many would consider polymorphic sexual dysfunction as home movie […]. The extract presented in True Gore depicts Cazazza digging at a sore on his penis with a metal scalpel, and Smith letting a gigantic black centipede scuttle over her labia” (Sargeant 1999). |

| 10 | From the title of the album composed by the members of Clock DVA in 1991. |

| 11 | From the introduction to the article “Corps Humain” by Isabelle Queval (Queval 2015, pp. 40–41). |

| 12 | From “Technologie et sexe dans la science-fiction. Note sur l’art de la couverture” (Alloway 1956, p. 45). See also Matthew Biro’s The Dada Cyborg: Visions of the New Human in Weimar Berlin (Biro 2009). |

| 13 | Donna Haraway as quoted in Manifeste cyborg et autres essais: sciences, fictions, féminismes (Allard et al. 2007, p. 35). The authors add that “our machines are strangely alive while we are appallingly inert.” |

| 14 | “Through cut-up, the principle of repetition reaches a degree of systematization which transforms it into a mechanical process. One can talk about a technique of cut-up. […] Cut-up can both operate a mechanical (repetitive) and technical writing (a writing that requires a technè, a practice which stems from a kill). Yet, initially, the mechanical is opposed to the organic: cut-up can help conceive the deconstruction of this binary opposition and refashion the links between writing and the mechanical” (Hougue 2014). One should recall the fact that Mark Pauline met William S. Burroughs in the beginning of the 1980s, along with Matt Heckert. For Burroughs’ influence on industrial culture, see “Révolution bioélectronique. Les musiques industrielles sous influence burroughsienne” (Ballet 2017). |

| 15 | Mark Pauline as quoted in the Industrial Culture Handbook (Vale and Juno 1983, p. 27). |

| 16 | From “Essay on J. G. Ballard” (Revell 1984, p. 145). The themes which the British author deals with in his works are driven by his own obsessions: “I believe in my own obsessions, in the beauty of the car crash, in the peace of the submerged forest, in the excitements of the deserted holiday beach, in the elegance of automobile graveyards, in the mystery of multi-storey car parks, in the poetry of abandoned hotels” (Ballard 1984, p. 174). |

| 17 | Valérie Mavridorakis deals with the impact of the Independent Group, especially with its part in the 1956 international exhibition “This is Tomorrow” (London, Whitechapel Art Gallery), in Ballard’s work. This influence partly stems from “a lack of desire” felt by Pop artists during the 1950s, who attempted to restore “a form of ‘cultural libido’ [by resorting to] the themes of the ideology of abundance, linked with consumption and technology and which promised a cultural renewal” (Mavridorakis 2011, p. 16). |

| 18 | Mark Pauline as quoted in the Industrial Culture Handbook (Vale and Juno 1983, p. 27). |

| 19 | Tsukamoto Shin’ya’s themes are also exploited by Shozin Fukui (福居ショウジン) in the films 964 Pinocchio (1991) and Rubber’s Lover (1996). Shozin Fukui had already directed two short films by the end of the 1980s: Gerorisuto (1986), as well as Caterpillar (1988), designed by the Japanese filmmaker when he worked on the filming team of Tetsuo. The two directors then resorted to the same film techniques: depth animation, handheld camera and hyperactive editing. |

| 20 | Graeme Revell in correspondence with Éric Duboys. (Duboys 2009, p. 108). |

| 21 | “The activity of life always covers that of death impulses.” (Lyotard 1977). |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ballet, N. Survival Research Laboratories: A Dystopian Industrial Performance Art. Arts 2019, 8, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8010017

Ballet N. Survival Research Laboratories: A Dystopian Industrial Performance Art. Arts. 2019; 8(1):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8010017

Chicago/Turabian StyleBallet, Nicolas. 2019. "Survival Research Laboratories: A Dystopian Industrial Performance Art" Arts 8, no. 1: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8010017

APA StyleBallet, N. (2019). Survival Research Laboratories: A Dystopian Industrial Performance Art. Arts, 8(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8010017