Abstract

This paper is a metaphorical extension of my practice of intertwining my conceptual/theoretical development with my personal history. Allowing the autobiographical narrative to become the driver of my practice has had a profound influence on my work. This has resulted in changes in the intention and scale of my work and new approaches to making, with a re-evaluation of the hierarchy of processes and materials. Written as a reflective case study, from a practice-led research perspective, the paper illustrates a realignment in creative methodology from a craft-based practitioner specialising in kiln-formed glass, to that of a mixed media sculptor. This transition was made in response to my desire to break free of my perceived confines as a craft practitioner, with a focus on technical excellence and the predominant language of glass, and place the concept at the forefront of my practice. This enabled me to explore the relationship of personal geographies of landscapes, to inform my prevailing concepts of corporeal vulnerabilities, in a more integral way. S-O-T Body Repairs was the title of a solo exhibition that sprang from this body of research and is discussed in this paper.

Keywords:

narrative; materiality; corporeal; auto ethnographic; place; values; art glass; readymade; sculpture; craft 1. Introduction

My father was a panel beater; a specialist ‘technician’, using a traditional dolly and hammer to beat dents out of car bodies, redefining the car’s curved shell. In 1965, the year after I was born, my father established S-O-T (Stoke-on-Trent) Body Repairs with two other colleagues; he acquired a lease from the coal-board in Longton, Stoke-on-Trent.

This paper provides a case study of a transition in practice, charting an auto ethnographic pursuit that has resulted in a realignment from a material driven enquiry with roots in craft, that emerges from a background in studio glass (I have been working with kiln-formed glass for over thirty years), to the production of concept-driven sculpture.

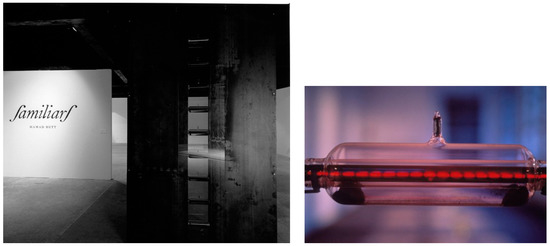

As McLaren described in his survey of studio glass between 1960 and 2000 ‘Matthias’s work is a technical tour de force that combines many of the kiln-forming processes within individual forms. Her ‘Body Series’ of sculptures, for instance, makes use of pate de verre outer shells; crushed, fused, glass lead crystal cellular internal structures and lost wax cast, polished, crystal bases and centre core’ (McLaren 2002) (see Figure 1). This typifies the kind of technical description that still prevails in the world of studio glass critique, but also captures the technical focus of my work up until the late nineties. Since that time, over a period of roughly 16 years, I have transformed my methodology and rationale for making as I began to incorporate found objects in combination with glass, gradually shifting to a more conceptual, mixed media practice, and culminating in a solo exhibition of sculpture, S-O-T Body Repairs in 2016 (see Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Matthias. 1996. Body I.

Figure 2.

S-O-T Body Repairs solo exhibition at the Old Bakery.

The umbrella of craft which houses the studio glass/art glass movement suffers from a ‘fractionalised confusion that prevents those practices placed within its boundaries from forming a cohesive lobby’ (Greenhalgh 1997), encompassing functional and ornamental production, alongside artistic/conceptual outputs and hobbyist pastimes. As a consequence, ‘craft’ struggles to accommodate such divergent practices. Recurrent theoretical debates by critics such as (Greenhalgh 1997; Clark 2010; Adamson 2007) about the definition of craft and the status of craft in relation to fine art and design have been prevalent throughout my life span as a practitioner and educator without any real resolution. According to Elizabeth Donald (2012), ’It appears that this problem emanates from craft itself which has few, if any, practitioners writing from their perspective of practice’.

Garth Clark talks about ‘art envy’ (Clark 2010) by craft practitioners, craft swirls in a world of inferiority/superiority, which I would confess to sometimes succumbing to. Some fine art practitioners appear to be revered and liberated in comparison to insecure craft practitioners who are constantly having to defend and define their craft practice and its value in a postmodern society. You could classify the kind of work that I used to make as ‘art glass’, this term has always struck me as oxymoronic. Connor Wilson expresses a similar frustration with ‘ceramic art’. ‘The term makes me uncomfortable, as it seems blind to the social and epistemological differences that exist between the various disciplines of visual culture. The route to any kind of critical or commercial success in ‘ceramic art’ is remarkably narrow and even when traversed, there is little criticism worthy of the name’ (Wilson 2016), the same can be said for the more youthful studio glass movement.

Dramatically, Clark wrote that the craft movement that desired to establish high craft as a peer of high art, wearied by an artificial self-loathing, died around 1995 in the US. He believed that craft suffered from a diet of sugary nostalgia, conservatism, and was inward looking, also lacking substantial critical analysis and debate (Clark 2010). Although extreme in his provocations, Clark made some valid points about the state of craft that I concur with and inform part of my reasoning for leaving my craft practice behind. In this paper, my intention is to highlight the problems with craft/art glass from a personal perspective.

In 2010, I began a series called ‘Anatomical Deconstruction’, working with broken found objects (sinks and toilets that I acquired from reclamation yards in Stoke on Trent). Exploring the body, as interior and exterior landscape. I was intrigued by the bone-like qualities of the ceramic fragments and started to take moulds from internal slip cast cavities and make real these negative spaces in cast glass which related to Lacan’s theories about the rim and ‘objet petit a’ (Gross 1990). The ceramic and cast stoppers were combined with raw, chipped, sheet glass in an attempt to make ‘sloppy craft’ that edged towards the nonchalant treatment of glass evident in fine art work. I hoped that it would enhance my material language and help me acquire a more diverse gamut of expressions. As the work progressed the fragments of ceramic that represented the sign of the sink became smaller and the work became more pared back, as I tried to capture the essence of my concept in a visually economical way (see Figure 3). However, this was still too restrictive a methodology, as glass always formed part of my visual language, and yet was not always an appropriate material to express my ideas; I adapted my ideas to suit the material.

Figure 3.

Matthias. 2014. Anatomical Deconstruction IX.

In 2015, I made a conscious decision to produce a narrative body of work based on the identity of S-O-T Body Repairs and surrounding landscape that had no association with my glass practice. Repair and creation of damage, waste materials, and industrial objects provided strong associations that are inherent in the geography of my birthplace, its industrial heritage and deterioration in status. I have explored this relationship in response to my personal geography by observing the changing contours of my own flesh and bone due to daily wear and tear and exposure to environmental pollutants; my sensory response to spaces that I have occupied. These analogies between macro and micro geographies have informed my primary concept of corporeal vulnerabilities. In this paper, I wish to discuss the broad application of this research, touching upon the many strands of my investigation, to provide an overview of my change in artistic practice.

The late 1960s onwards saw a revival in the body and the capturing of its physicality, especially with the arrival of Feminist Art. My recent sculptures could be seen to fall into a prominent strand of postmodern art that is the body as metaphor, particularly looking at micro/macro relationships and the absence or remains of the body via body dislocation (Heartney et al. 2007).

I have selected key pieces to discuss from the eighteen sculptures I made for the exhibition.

2. Body Repairs—Space and Place

‘Body Repairs’ is an obscure company title, avoiding the explanatory nomenclature of vehicles, the success of the business equated to the numerical data on insurance claims for scrapes, accidental damage and fatalities on the roads of Staffordshire. The company garage was previously a miners’ baths serving the nearby Mossfield Colliery. My father converted the showers from a dank, cold wet-room to a hot, arid booth to dry the paint sprayed cars (see Figure 4). In some respects, I would like to visit this masculine domain, to see the wrecked cars and spare parts; I was intrigued but wary of this space, the activities that occurred within it, and its animate and inanimate contents. The noxious mix of fibreglass resin and spray paint permeated the building. Though difficult to classify, olfactory or lingering odour memories have strong associations across time and space operating at primordial levels; this felt like a primal place (Hall 1969; Rodaway 1994). The internal premises of the former site of sanitation now seemed to be caked in a compound layer of exhaust grey soot and engine oil, except for the pristinely repaired cars. It also provided a stark contrast to my polished home environment. The body repair garage was a place that housed remnants of death and destruction alongside restoration and rebirth. Offering a strange form of translation whereby the original object appeared to be restored to its previous state.

Figure 4.

The spray booth at S-O-T Body Repairs (left).

Harmful waste gases and toxins that are expelled through exhaust respiratory systems also polluted this space. When isolated, the car exhaust is an alien yet familiar arrangements of pipes and containers with bronchial connotations. Gavin Turk presented a series of cast bronze exhausts, painted to mimic rusty old pipes alongside blown glass versions (This is not a Pipe) in 2012–2013, a nod to Magritte’s painting of the same name. The glass exhaust was fabricated by Venetian master glass blowers at the Berengo Glass Studio for a series of Glasstresse exhibitions that formed part of the Venice Biennale. To showcase the creative potential of glass and raise its material status, Berengo invited fine artists to respond to the material, rather than studio glass artists.

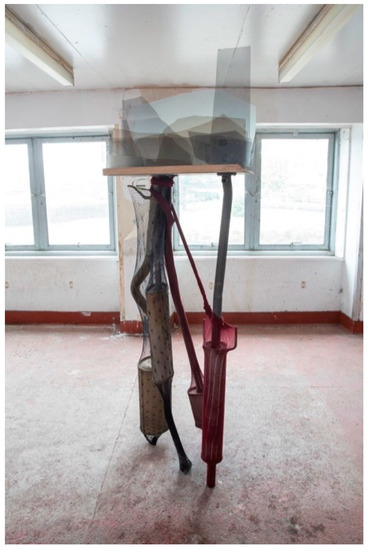

‘For Turk the exhaust pipe represents the transport of air and is a metaphor for both breathing and exhaustion. The “pregnant snake-like object” also holds up an anthropological mirror to society’s reliance on roads and transportation and the consumption of resources at the heart of this’ (Turk 2013). Paradoxically, the extraction of fumes from the exhaust system leading ultimately to the exhaustion of the engine also inhibits our ability to respire effectively. Smashed cars have a similar jumble of spewing innards protruding from their bonnets as an alternative roadkill. In my latest sculptural work, I am appropriating used mechanical parts such as plastic radiator bottles and hoses in mixed media assemblages. I combine a variety of traditional and mechanical modelling processes to extract visual narratives of damage, decay and impermanence in association with the corporeal. For example, the multiple exhaust pipe props in True Skin (one of the few pieces to contain glass) are subcutaneous in nature, supporting the fragile dermis or landscape above (see Figure 5). The work is deliberately low-tech in construction, chipped, scratched glass is left smeared with fingerprints and dirt, synonymous with the post-industrial landscape it represents but also the fragility of the dermis.

Figure 5.

Matthias. 2016. True Skin featured in S-O-T Body Repairs exhibition.

My father’s garage was located in the remnants of the mining industry, based in Longton, one of the main towns of Stoke-on-Trent, epitomized by Arnold Bennett’s ‘Anna of the Five Towns’. The City of Stoke-on-Trent is actually composed of six towns; a centre-less place, it is the only polycentric city in the UK. Visualized on a map, the narrow vertical zig-zag of towns is surrounded by the rugged Peak District and Staffordshire Moorlands, and was once united under the banner of The Potteries. Local collieries, steelworks and Trent Mersey canal systems supported this industry. According to Simeon Shaw (1900) ceramics had been practiced in this region since the Roman invasion of the British Isles and has been fully operational for around three centuries. A steady decline and eventual closure of renowned companies such as Wedgewood (1759–2008), Minton (1796–1990), and Doulton (1815–2005) has eroded The Potteries.

Our family home is situated in Clay Lake in a small valley at the bottom of Brown Edge, names with strong connections to land and materials of manufacture and manipulation, yet part of the ‘picturesque countryside’. Valentine (2001) states that the countryside was historically associated with the feminine, women being inferiorly defined in terms of their biology, making them closer to nature. The countryside was unruly, only to be entered if you worked on the land, a subordinate setting, to be tamed and submerged. It provided a picturesque backdrop, an allegory for the division between masculine and feminine worlds. Therefore, my parents did not embrace the countryside as a site of recreation or restoration from a life in industry; it was viewed remotely via Sunday afternoon drives in our new family car. Hall identified how the car insulates people from kinaesthetic and visual sense of space, adding ‘they permit only the most limited types of interaction, usually competitive, aggressive and destructive’ (Hall 1969). They offer a false sense of security, propelling the inhabitants in a sealed shell that suggests an extension of the home. This aspect of upward mobility was extolled by my family.

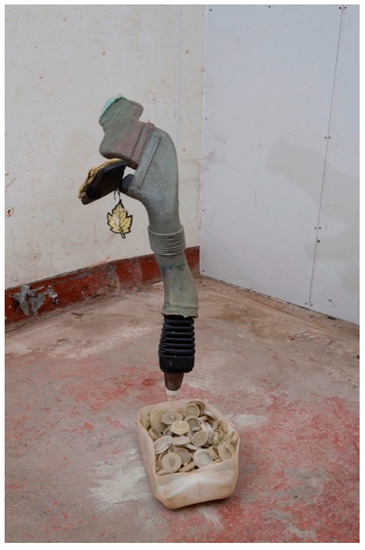

I have appropriated the propelled fragments of near misses, such as discarded car hub caps and wing mirror covers that I collect from the side of the road, into my sculptures, as signs of abjection. I have united the wing mirror cover (masculine) with domestic cleaning materials (feminine) in the production of a phallic symbol, as warped versions of two-pronged mining drill bits, a clash of materials and representations of public and private spaces (see Figure 6). The colour palette for my plasterwork was deliberately restricted to combinations of grey and terracotta found in the raw flint-based materials impregnating the former flint factory, that is now the Industrial Museum of Etruria. Doris Salcedo’s use of domestic objects such as cupboards filled with concrete that partially revealed excavated clothing, exhibited as tomb-like monuments, also come to mind (Salcedo et al. 2000).

Figure 6.

Matthias. 2016. Drill Bits, featured in S-O-T Body Repairs exhibition.

There was a stark contrast between the vibrant pockets of countryside that contained the dreary remnants of mining and ceramic industries. The land used to be rich with an abundance of ‘sought after’ commodities. Being close to the surface, almost in open pits, coal and marls containing different clays were easily accessible and therefore inexpensive. Shaw described the coalfields around this area as having many geological faults resulting in the dispersal of the coal across the district rather than housed in one place (Shaw 1900). This scattergun excavation of the earth has drastically scarred and modified the landscape of The Potteries, a violation of the body of the land. Mineshafts have destabilized the foundations of the area resulting in subsidence, therefore flora-covered slag heaps are reoccurring memorials to the industry, strangely picturesque but inhabitable spaces. The contrast between internal and external structures, visible and invisible features, the possibility of hidden danger evident in this type of landscape also mirror associations with the body, the threat of internal damage, be it emotional or physical, disease and erosion, and form part of my visual language. I make this evident in my work by revealing inner structures through fragmentation of used utilitarian ceramic objects; a glazed ceramic sink can be broken to reveal neglected coarse internal surfaces, dirt and debris (see Figure 7). By taking rubber moulds of these internal cavities I can replicate them as three-dimensional positives that can be manipulated and celebrated as structures through exaggeration in form and scale (see Figure 8).

Figure 7.

Matthias. 2014. Wax models taken from the inside of broken sinks.

Figure 8.

Matthias. 2015. Land Marks II.

Capturing voids as positive spaces is a similar process to Rachel Whiteread’s fine art practice; she and her team of fabricators have taken casts from the underside of domestic objects like beds, chairs, and baths that also have a human vernacular. As Colomina (2001) observes, ‘Casting is an interrogation of space; violently pulling evidence out of it’. These curved forms that emerge from the slip cast spaces are in turn moulded and turned into wax to be replicated and assembled to produce exaggerated elongated phallic stoppers (plugs) or primal tools or bone-like implements that could be reintroduced into a relationship with the ceramic readymade fragment. I choose to juxtapose these two objects together, the old fragment of little worth with the fine cast counterpart as a way to highlight the uniqueness of the fragment and to introduce a new value, in a similar way to Whiteread, ‘those voids of beds and baths were the not-very-special traces of the not-very-special objects, made special’ (Townsend 2004). The ceramic object’s former purpose was to contain waste, and they have now become waste, but there is beauty in this abjection, which is highlighted through the casting of their hidden spaces, making them visible and positive.

3. Waste—Industrial, Cultural, Personal, Aesthetic

Waste and the disposal of waste featured in the invention and production of sanitary ware in The Potteries. Thomas Twyford, a third-generation proprietor of Twyfords pottery in Stoke-on-Trent, became the pioneer in the field of sanitary ware. The fluid ergonomic organ-like nature of the bowl and siphon with the tubular rim containing the flush passage, the clay punctured holes allowing the water to trickle down and flush the bowl have an aesthetic corporeal familiarity. Once broken, both the sink and toilet reveal through autopsy their inner unglazed channels, orifices, smooth and rounded bone-like walls and cavities integral to the slip cast process that reference parts of the cranium, scapula, and sacrum. My use of ready-mades is not just an appropriation of existing objects; I believe I am investigating forms through breakage, moulding and reconfiguration to reveal something about the object in relation to human interaction, similar to Whiteread’s methodology. Baudrillard (1997) states ‘as if art, like history, was recycling its own garbage and looking for its redemption in its own detritus’. Perhaps I am wishing to do the same in my work.

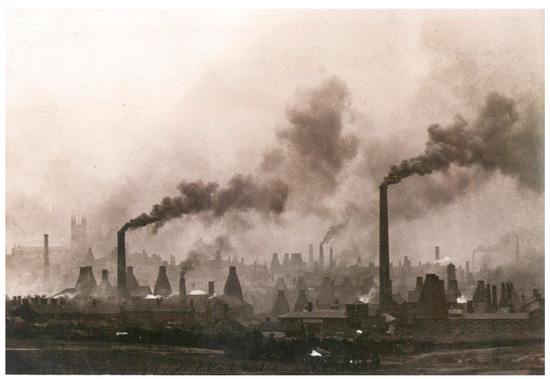

The proliferation of historical waste and marks of destruction evident in the industrial landscape also had an impact on the workforce’s wellbeing. ‘Palls of black smoke hung in the air; trees, hedges and houses were covered with soot fall’ (Denley 1982) (see Figure 9).

Figure 9.

A postcard of bottle kilns in Longton, Stoke-on-Trent early 20th Century.

The personal effects of pollution, ‘industrial diseases known as potter’s asthma or ‘the potter’s rot’—pneumoconiosis was due to poor working conditions. The main cause was the inhalation of sharp particles of silica dust from the calcined flint that was used as a whitening agent in the earthenware body’ (Denley 1982). Rodway cites that the ecological concept of perception, space across which a stimulus crosses from source to sense organ, is not empty; it comprises surfaces, textures and objects that can interfere with the stimulus message (Rodway 1994). These interferences could be extended to include the microscopic world of airborne pollutants and microorganisms made real by advances in magnification in the 1700s evident in disease, intolerances and allergic reactions. I have developed sensitivities to certain fumes and dusts, over the years probably due to prolonged exposure.

Both Respirator (see Figure 10) was named after the iron lung chambers used to originally treat miners with lung disease and which became synonymous with treatment for polio; the respirator was named after the inventor. In my work, the enlarged black plastic heart or lung-like organs have limited capacity, as there is only one connecting eroded, clogged pipe. I imagine a claustrophobic response from this symbiotic or antipathetic relationship, is ‘Both’ healthy or unhealthy? I was originally going to remake these slumped forms in glass, then realised that this was a habitual unnecessary response.

Figure 10.

Matthias. 2016. Both Respirator featured in S-O-T Body Repairs exhibition.

According to Ellman (1990) when defining Kristeva’s theories, ‘abjection refers to waste itself, as well as the act of throwing it away’; however, it can also relate to dejection and despondency. She continues, ‘Waste is what a culture casts away in order to determine what is not itself and thus to establish its own limits. In the same way, the subject defines the limits of his body through the violent expulsion of its own excess’. Industrial waste in all its material forms was previously an emblem of mining and ceramic industry in the Potteries, which provided infrastructure, identity, status and sustenance. The waste in the form of slag heaps is now an emblem of all that was, a past heritage of recognition and worth, worth of a place and worth of a people.

Besides slag, the other main waste product that has filled the landscape in The Potteries is ‘known in the trade as ‘shraff’’ (Harrod 2005), and is compiled of ceramic industrial waste including kiln furniture, saggers, moulds, and rejects. Local ceramicist Neil Brownsword began to photograph the detritus and debris of a by-gone industrial era and in 2003 he recorded the decline of the skilled workforce at the Wedgewood factory where he was once an apprentice, through a series of filmed interviews. Hierarchical divisions within the workforce related to skill and gender, and specialist jobs were lost to automation. Brownsword’s work is influenced by archaeological scavenges of shraff heaps, selecting ambiguous by-products ‘signs of human touch that occur inadvertently’ (Harrod 2005); these remnants epitomize the waste of a whole industry, and for that reason are placed alongside his own manipulations in considered, unsentimentally curated compositions that are sculptural in nature, yet still adhere to a ceramic art practice rooted in a material discipline that maintains a domestic scale (see Figure 11). Brownsword later orchestrated an artistic research project entitled ‘Topographies of the Obsolete’, resulting in a publication made as a response to the derelict site of the Spode factory (2013).

Figure 11.

Brownsword. 2001. SY Series.

Selection of the overlooked, ordinary, especially broken objects resonated with me, by reclaiming, spending time selecting items, combining them with labour-intensive processes and more valued materials, I was enhancing their worth, offering a form of restoration.

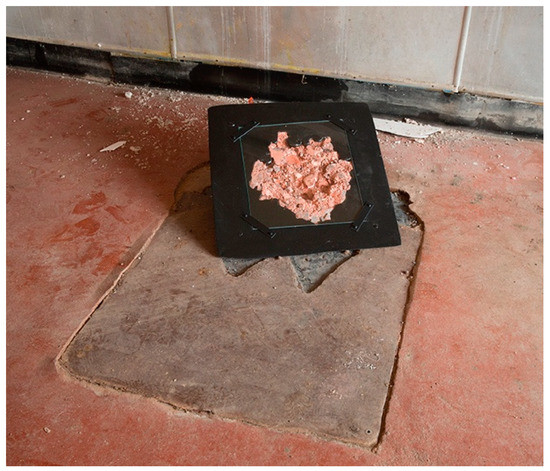

Inspired by Anselm Kiefer’s art processes, I also began to keep and make use of waste materials generated as part of my practice in my assemblages; drilled twirls of silicone rubber, dried clay props and excess mixes of plaster are no longer disposed of, they are vacuum packed (see Figure 12). Kiefer builds many layers of paint onto his canvases over long periods of time, he then hacks through the paint strata to reveal these layers and the stained canvas beneath; an act of destruction/deharmonising a landscape. He keeps all the waste chippings and fragments from his paintings in boxes. Working in a state of construction, demolition and reconstruction. He states that he has to guard against order as it sterilizes, believing that it is important to navigate between chaos and order in his work. The production and collection of waste also seems to be a physical way of achieving this balance. According to Stafford, during the philosophical movement, the Age of Enlightenment (1685–1815) the right angle and/or perpendicular were measures of uprightness, purity and beauty (evident in the Neoclassical paintings of that time), and were informed by prevalent mathematical theories. Vice, on the other hand, was represented by a lack of measurement, acute or obtuse forms equating to unruly ugliness (Stafford 1997). Kiefer grew up surrounded by the rumble and detritus of a bombed Germany after the war, an aesthetic landscape illustrious of vice. Order, which Kiefer wishes to avoid, could be described as geometry.

Figure 12.

Matthias. 2016. Shraff, featured in S-O-T Body Repairs exhibition.

I strive for an asymmetrical or awkward composition in order to create tension and the suggestion of imbalance in my work. I believe that precarious assemblages can offer greater emotional resonance and engagement with the work; or repulsion. Physicist Frank Wilczek (2015) suggests an alternative to beauty/symmetry, whereby ‘the reward is not finding symmetry but finding novelty’, moving beyond the predictable with the entrance of the element of risk. The beautiful thing derives from something that is very close to failure. This way of thinking is something I strive for; seeking to deliberately work in low-tech or rough ways, not because I do not know otherwise, but because I wish to be more expressive, to show my intent. I would interpret this as an act of human connection through a potential revelation of vulnerability (see Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Matthias. 2016. Os Coxa Diaphragm Chamber 142, featured in S-O-T Body Repairs exhibition.

4. Domestic

It is important for me to contrast the setting of manufacture with the domestic, as the domestic was and still is a hidden industry of one, but it was a place that I did not aspire to inhabit. Pollock (1991) defines and compares the mental map of the masculine in terms of the competitive, divisive world of business with that of the feminine, the domestic ‘non-social space of sentiment and duty from which money and power were banished’, these institutionalized roles informed the mind-set of my parents’ generation situated in landlocked Stoke-on-Trent. At the root of such social divisions that organize culture, define roles and social status through the activity of work, are biological distinctions ‘the opposition between productive and reproductive work’ (Chamberlain 2000). My mother had the isolation of domestic life to fill and make worthwhile. An obsession with cleanliness, the creation of order within the domestic setting became my mother’s (pre)occupation. She gave herself endless repetitive tasks to fill her week to keep herself busy. Cleanliness was next to Godliness, dirt was the enemy, it existed in the surrounding countryside, alien environments and industrial settings. Mary Douglas (1966) referred to dirt as a disordered ‘matter out of place’.

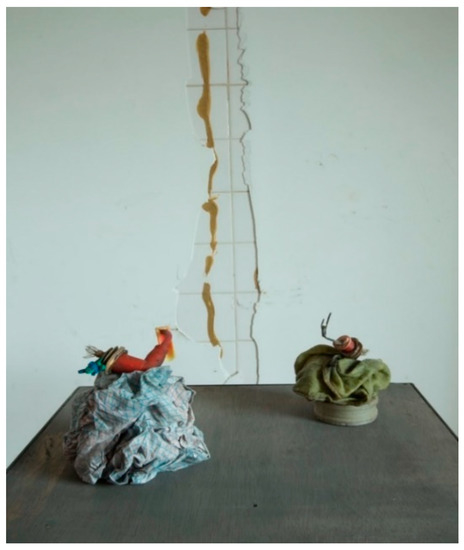

As discussed in Drill Bits (see Figure 6) I began to fill cavities in my work with cleaning cloths, scourers, sponges, etc. they provided a padding rich in colour and texture. It was important that the cleaning materials were dirty to show signs of obsessive cleaning and the collection of debris, stains etc. This introduced the feminine aspect into my work. These cleaning materials symbolize the restrictions imposed by a patriarchal society; the confines of domestic denigration. They also represent hard toil and aspects of making and cleaning in an industrious way. I appreciated the folded forms of the cloth and solidified these folds by dipping the fabric in wax, producing protective bases for small organ-like pieces to nestle in, as evident in Renaissance wax anatomical models that were displayed on protective silk-like cloths (see Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Matthias. 2016. Anatomical Cameo I and II, featured in S-O-T Body Repairs exhibition.

5. The Problem with Art Glass

I later exchanged the post-industrial landscape of the Potteries for the Stourbridge Glass Quarters of the West Midlands in order to study 3D Design: Glass. This landscape is similar to the Potteries, with a decline in local specialist industry evident by the one remaining intact towering glass cone to mark the production of blown glass. Regally named glass companies like Tudor Crystal, Stuart Crystal and Royal Brierley Crystal occupied the landscape of Stourbridge during the late 19th and 20th Centuries.

Glass has a strong direct and indirect intimacy with the body through the vessel, the mirror, laboratory equipment and the microscope/magnifying glass, which reveals the internal corporeal topography and magnifies (im)perfections. The Age of Enlightenment spawned numerous inventions and improvements in optical instruments. Building on anatomical knowledge acquired through dissections and vivisections in the 18th Century, the microscopic landscape revealed strange cellular hyper-real vistas, but it did not ‘exhibit the bedrock of changeless substances to distinguish infallibly between matter and spirit, subjective and objective experience’ as was hoped for (Stafford 1997). It did not offer explanations surrounding the purpose of existence nor provide evidence of a God that would offer reassurance, certainty or hope. It revealed secret cellular mechanisms, raised more questions than answers and magnified mortality.

Glass has a ‘…metaphoric value in the arts, representing fragility and thus the transitory, precarious and impermanent nature of existence’ (Lodognata 2013). Exemplified by artwork such as Hamad Butt’s iodine filled glass rungs in ‘Substance Sublimation Unit’ (see Figure 15) and Robert Smithson and Barry LeVa’s visceral qualities of piled smashed glass. Fine artists seem to employ a wider vocabulary of glass in their work and combine it with a broad range of materials and objects. Therefore, glass as a material is not revered, the technical manipulation of the material is not a concern or motivation, so glass can exist in all states and can be used by fine artists to address wider issues. I believe that on the whole, the broken language of glass is undervalued by most studio glass artists and gallery owners within the world of craft, there appears to be a desire for shiny, fluid, technical prowess. On inspection, the one hundred studio glass images selected for the annual New Glass Review, an international survey published by Corning Museum of Glass, over the past forty years, still deal with this technical fascination, glass artefacts exist in isolation and can in some instances be formulaic across the decades, existing in a timeless void, as museum curator McLendon states, ‘I see far too much replication without evolution’ (McLendon 2017).

Figure 15.

Butt. 1992. Substance Sublimation Unit.

Although there has been a shift within the last decade, the New Glass Review now documents more examples of large-scale installations, such as Jeffrey Sarmiento and Erin Dickson’s Emotional Leak, 2014 and the mixed media work by Simone Fezer in_with_in, 2018; the ‘Glass-Secession’ group (US) and the more recently formed Glass Virus Think Tank have had ambitions to take on the critical debate and reposition art glass; however, as McLendon (2017) suggests, further adaptation is required. Art Glass or ‘Craft is fundamentally conservative’ (Clark 2010) with a tendency for nostalgic backward glances. James Yood (2014) states that the reason gallery owner Berengo no longer exhibits studio glass artists’ work is because ‘it concentrated too much on technique and process and had become a closed and inbred camp’, which is why he invited such artists as Gavin Turk to exhibit in Glasstresse. On the whole, I agree with this observation; the world of glass, with technical pursuit and technical dialogue viewed as ends in themselves, can limit the scope of expression and conceptual development. Any practice with a central material/technical pursuit, even if it is purely expressive in outcome, I would still attribute to a variation of craft. ‘Craft’ is quite often associated with a particular social background, honest hard labour participating in unpretentious production, a nostalgic, romanticised rural/pastoral workshop activity, and defined by material expertise, the quality of the finish, meticulous attention to detail and haptic dexterity. These perceptions have proved difficult to redefine. Contemporary conceptual craft practitioners are chipping away at these preconceptions but while their loyalty remains with the demonstration of technical accomplishment resulting in a restricted aesthetic language, and there remains limited critical discourse on the subject, it is difficult to see how to effect change.

I therefore made a conscious decision to place my conceptual and theoretical investigations and narrative pursuits at the helm, and after an extensive period of research and investigation, I made the S-O-T Body Repairs series of work, which firmly sat in the fine art arena, without ambiguity, apology, or justification attached to it. I wanted to face new challenges; by no longer being restricted by my craft practice, I was able to work in a more freely expressive way. To do this, I had to untangle my aesthetic and technical training so that I could work in a more immediate way with a wide range of appropriate materials, that enabled me to more directly communicate my concepts, a protocol instigated by the Arte Povera group of artists, whose ethos was to achieve poetic statements through the simplest of means, as a matter of convenience (Lumley 2004). I had to re-evaluate the hierarchy of materials and processes in relation to relevance and expediency. I began by elevating the intermediary lost wax casting materials of wax and plaster into the final sculptures. Instead of slumping glass, I would vacuum-form plastic, instead of meticulous joining, I would use plastic car body rivets, tape, expanding foam. I applied my understanding of lost wax casting to metal casting. Combining all of these processes with cheap ‘off the shelf’ materials and expanding my repertoire of found objects, I was able to produce a series of mixed media sculptures that succinctly captured my narrative concerns. Through these means I was also able to respond candidly to my chosen exhibition arena, an old bakery in Truro which aptly echoed some of the rundown qualities of my father’s garage and signified the loss of industry in its own right.

As Sennett (2009) states ‘against the claim of perfection we can assert our own individuality which gives distinctive character to the work we do.’ He continues, ’getting things right be it functional or mechanical perfection is not an option to choose if it does not enlighten us about ourselves’. Through processes of researching, deconstructing, evaluating and redefining I now have a clear understanding of how my past sensory experiences and narratives can be succinctly communicated through my work. I can identify glass as a magnifier of biological realities that inform my aesthetic sensibilities, and its power as a visceral material in my work, but more importantly as an absent material that I no longer need to adhere to.

I have made connections between macro and micro spaces such as the geography of the Potteries that has been scarred by the redundant manufacturing industries and waste materials, the body repair garage (that I have emulated in my glass workshops), the moulding of negative spaces found in car parts and broken utilitarian ceramics, and the pollutants that inhabit such spaces and their impact on the human body. However, more importantly, I have introduced the domestic (feminine) via the use of cleaning materials into my assemblages. I have established a connection with something that I had rejected and now recognise the value in this. The integration of dirty cleaning materials alongside the car body parts has created a more complete composition that clearly reflects my personal identity and inspirations in a way that I could not have achieved if I had remained loyal to a craft centred approach to making.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Figure 1—work is created by the author and photographed by Sarah Hodges; Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8, Figure 10, Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14—work is created by the author, photographed by the author or Simon Cook; Figure 9—the image is in public domain; Figure 11—used by permission; Figure 15—used by permission, photographer Steve Shrimpton (black & white photograph).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Adamson, Glenn. 2007. Thinking Through Crafts. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Baudrillard, Jean. 1997. Objects, Images, and the Possibilities of Aesthetic Illusion. In Art and Artefact. Edited by Nicholas Zurbrugg. London: Sage, pp. 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain, Lori. 2000. Gender and the Metaphorics of Translation. In The Translation Studies Reader. Edited by Laurence Venuti and Mona Baker. London: Routledge, pp. 314–29. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Garth. 2010. How Envy Killed the Crafts. In The Craft Reader. Edited by Glenn Adamson. Oxford: Berg, pp. 446, 449–50. [Google Scholar]

- Colomina, Beatriz. 2001. I Dreamt I Was a Wall. In Rachel Whiteread: Transient Spaces [Exhibition Catalogue]. New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, pp. 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Denley, James. 1982. A History of Twyfords 1680–1982. Available online: http://twyfordshistory.blogspot.co.uk/p/denley-history.html (accessed on 2 November 2018).

- Donald, Elizabeth K. 2012. Mind the Gaps! An Advanced Practice Model for the Understanding and Development of Fine Craft Practice. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Dundee, Dundee, Scotland; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, Mary. 1966. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of the Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. London: Routledge, pp. 36–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ellman, Maud. 1990. Eliot’s Abjection. In Abjection, Melancholia, and Love: The Work of Julia Kristeva. Edited by John Fletcher and Andrew Benjamin. London: Routledge, pp. 178–200. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh, Paul. 1997. The History of Craft. In The Culture of Craft. Edited by Peter Dormer. Manchester: Manchester University Press, p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, Elizabeth. 1990. The Body of Signification. In Abjection, Melancholia, and Love: The Work of Julia Kristeva. Edited by John Fletcher and Andrew Benjamin. London: Routledge, p. 88. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Edward Twitchell. 1969. The Hidden Dimension Man’s Use of Space in Public and Private. London: The Bodley Head Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Harrod, Tanya. 2005. The Memory-Work: Recent Ceramics by Neil Brownsword. In Neil Brownsword: Collaging History [Exhibition Catalogue]. Stoke-on-Trent: Stoke-on-Trent Museums, pp. 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Heartney, Eleanor, Helaine Posner, Nancy Princenthal, and Sue Scott. 2007. After the Revolution: Women Who Transformed Contemporary Art. Munich and London: Prestel. [Google Scholar]

- Lodognata, Mario. 2013. The Truth in Glass. In Fragile? Edited by Mario Codognato. Milano: Skira, pp. 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lumley, Robert. 2004. Movements in Modern Art: Arte Povera. London: Tate Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- McLaren, Graham. 2002. Studio Glass 1960–2000. Risborough: Shire Publications, p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- McLendon, Matthew. 2017. So What if it’s Glass: Rebranding a Medium. The Glass Art Society Journal 46: 73. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, Griselda. 1991. Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism and Histories of Art. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Rodaway, Paul. 1994. Sensuous Geographies: Body, Sense and Place. Abingdon: New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Salcedo, Doris, Nancy Princenthal, Carlos Basualdo, and Andreas Huyssen. 2000. Doris Salcedo. London: Phaidon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sennett, Richard. 2009. The Craftsman. Yale: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, Simeon. 1900. History of the Staffordshire Potteries; and the Rise and Progress of the Manufacturer of Pottery and Porcelain; with References to Genuine Specimens, and Notices of Eminent Potters. London: Scott, Greenwood and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Stafford, Barbara Maria. 1997. Body Criticism: Imagining the Unseen in Enlightenment, Art and Medicine. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, Chris. 2004. When We Collide: History and Aesthetics, Space and Signs, in the Art of Rachel Whiteread. In The Art of Rachel Whiteread. Edited by Chris Townsend. London: Thames and Hudson, pp. 7–33. [Google Scholar]

- Turk, Gavin. 2013. Images. In Gavin Turk. London: Available online: http://gavinturk.com/artworks/image/10933 (accessed on 10 October 2018).

- Valentine, Gill. 2001. Social Geographies: Space and Society. Harlow: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Wilczek, Frank. 2015. Start the Week: Harmony and Balance [Radio Broadcast]. BBC Radio 4, July 6. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Connor. 2016. Writing_Making: Object as Body, Language and Material. London: Royal College of Art, p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Yood, James. 2014. W(h)ither Glass? The Glass Art Society Journal 43: 31–32. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).