Abstract

Displays of art in public or private spaces have long been of interest to curators, gallerists, artists and art historians. The emergence of gallery paintings at the beginning of the seventeenth century and the photographic documentation of (modern) exhibitions testify to that. Taken as factual documents, these images are not only representative of social status, wealth or the museum’s thematic focus, but also contain information about artistic relations and exhibition practices. Digitization efforts of previous years have made these documents, including photographs, catalogs or press releases, available to public audiences and scholars. While a manual analysis has proved to be insufficient, because of the sheer number of available data, computational approaches and tools allowed for a greater access. The following article describes how digital images of exhibitions, as released by the New York Museum of Modern Art in the fall of 2016, are studied with a retrieval system to analyze in which artistic contexts selected artworks were presented in exhibits.

1. Introduction

The invention of photography in the nineteenth century has allowed to capture exhibitions of modern times faster and in large numbers. This has been done by museums, galleries and other cultural institutions for various purposes. The invention of digitization technologies in the late twentieth century has also produced digital repositories of photographic records of museum displays and recently, institutions publish them for everyone to see. For art historians, these collections provide a rich source to study installation practices over time, displayed artworks and their suggested relations to other artworks. The interest in displays of artworks, however, can be traced back to the pre-modern period, when, at the beginning of the seventeenth century, the genre of the gallery painting was established in the Netherlands. Famous examples include David Teniers’ (the Younger, 1610–1690) paintings of archduke Leopold Wilhelm’s (1614–1662) art collection in Brussels, works by Johann Michael Bretschneider, the Francken family, Adriaen Stalbemt, Hendrik Staben or Jean-Antoine Watteau’s ‘The Shop Sign of Gersaint’ (1720–1721) Nicholls (2006). The research presented in this paper makes use of digital records of exhibits and demonstrates how these can be studied with computer-based methods to analyze in which artistic context artworks were shown and ultimately support with provenance research—both important task of art historians. The method further stresses the possibility of a visual instead of a textual reconstruction of exhibition histories and provenance research; the latter strongly relies on the availability of text documents, which are often difficult to access, lack completeness or contain erroneous information. While it is impossible to evaluate these digital exhibition records manually, computer technologies are able to process millions of images, thus allowing to formulate universal statements or to find broader patterns in art—this is one great potential of retrieval systems. For photographs of exhibitions this means that we are able to evaluate a great number of images, to make general statements about exhibition practices for specific artworks and trace its inclusion in shows through time and place. To evaluate images, an interactive interface was used, which was developed within the Computer Vision Group at Heidelberg University1. Since 2009, the group hosts an interdisciplinary project between computer vision and art history, resulting in various projects, which applied various computational methods to art data. The interface enables to object and part retrieval in art datasets, which has been tested on diverse image collections, such as architectural prints, paintings of Christ’s Crucifixion and medieval manuscripts. Preceding works studied legal communication in the Sachsenspiegel (c1220), a medieval law book containing heavily illustrated text sheets Bell et al. (2013), or included a computational analysis of reproduction processes of medieval images Monroy et al. (2011). The present study benefits from previous works and analyzes a set of exhibition photographs, released by the Museum of Modern Art2, by retrieving user-selected artworks. This article hypothesizes that computational tools can correctly retrieve user-selected artworks from exhibition photographs to assist with the reconstruction of exhibition histories. Although object retrieval has been used in humanities research for quite some time now, to the knowledge of the author, prior work has neither demonstrated its usage for exhibition study nor highlighted the possibility of a visual provenance research. Eventually, this interest in art displays highlights the importance of installations for the reading and meaning of individual works Grießer (2013).

Literature Overview

The literary overview consists of two parts, which are a direct result of the thematic focus and selected method of this article: while the first presents past works in art history on the topic of exhibits, the second provides an overview of works done in computer vision on object retrieval. Literature was selected, because it either gives an insight into the great variety of topics relating to exhibits and exhibition history or applications for object retrieval systems. Also, compiled literature is representative of different approaches and interests of scholars in the field of art history, computer vision and its intersection. Art historians have studied museum and exhibition history and installation3 practices in great depth; numerous books and articles are a result of this interest. Previous works discussed historic exhibits, the exhibition space, presented artworks and provided more practical guidelines for curators. Scholars pointed to developments in museum practices, based on changed social or economic values in society and the art world. In 1976, Brian O’Doherty published his influential article ‘Inside the White Cube’ O’Doherty (1999), where he studies the white gallery space and its meaning; he elaborates on the sociological, economic and aesthetic context in which viewers experience art and studies the relation between the content of the image and spatial context. He concluded that the museum space transforms everyday objects into art, that the white cube is a work of art itself and thus not neutral. The question, if artworks can endure without this context, was highly also significant to him. O’Doherty also elaborated on the installation photograph, which is central to this article, and notes the photogenic nature of the white cube and disappearance of the viewer in it; this is also visible in the MoMA records. While this article focuses on artworks and less on the space, future work should also explore the relation between space and images; computer-based tools might be used to examine different modes of hanging or the inclusion of benches, plants and other decor. In 2007, O’Doherty issued his follow-up ‘Studio and Cube’ O’Doherty (2012), focusing on the relation between an artist’s studio and the gallery space; he concludes that both are spaces in which art obtain meaning. O’Doherty dedicated much consideration to the exhibition space and thus is included in this overview. His writings are still relevant; although the present study is more interested in displayed artworks, it should be regarded that the MoMA as a cultural institution and space influences images and that both cannot be separated. Literature also includes practical handbooks on exhibition organization Pöhlmann (2007), Bertron et al. (2006) and more scientific discourses on exhibition histories, practice and discourses in museums. Grießer (2013) write extensively on the history of exhibits and relevant ’fields of action’ in museums. In her essay on ’Museology’, Monika Sommer discusses the origins of museums, its tasks of collecting, categorizing and presenting and the great meaning of museums for society. The term ’display’ is further studied by Christine Haupt-Stummer, who emphasizes the crucial role of art displays for exhibits and states that an increasing awareness of the importance of forms of presentations characterize modern museum practices; beginnings can be traced back to Edgar Degas proposals for the installation of the Paris Salon in 1870. Especially the last essay and accounts on aspects of exhibition organization and curating are relevant for this article, which is also based on the assumption that the way artworks are displayed in exhibitions and in which artistic context is crucial.

Other scholars have focused on individual shows and their importance for a global exhibition history, encompassing the period from the late seventeenth century to the present day. The following are examples of historic accounts of exhibits, which either focus on single or provide an overview of multiple shows. Bruce Altshuler’s ‘Exhibitions that made art history’ is a compendium of shows from 1863 until 2002, divided in two volumes Altshuler (2009). It is inarguably one of the most comprehensive reference books on exhibitions and records the development of modern art through art shows. It includes archival material, historic reviews and installation photographs and gives information on twentieth century art, exhibition design and curatorial practices. By doing so, it combines various aspects: stating historic accounts while also laying out practical recommendations for curators. Its comprehensiveness is exceptional and relevant for every scholar, who studies exhibits, the history of modern art and its display. Similar, Bernd Klüser and Katharina Hegewisch compiled thirty art exhibitions, held throughout the twentieth century for ‘Die Kunst der Ausstellung’ Klüser and Hegewisch (1991). Selected shows are representative of the symbiosis between exhibition room and art; the modern space became a Gesamtkunstwerk, where architecture and decor reflected the thematic scope and style of artworks. Although collected essays mainly provide general information, they elaborate on included artworks and their display. While accounts remain sketchy, they resemble attempts of this article. There is much literature on popular exhibitions, such as the ’Armory Show’ in New York City (1913) or the ’Degenerate Art Show’, held in Munich in 1937 as part of a series of shows Brantl (2007); those shows are well researched—also because photographic records are available—and much information is available about historic context, organization, installation and display of artworks. There would be great potential, if these textual and visual exhibition records, printed partially in books, can be linked, based on a computational analysis of digital images. Although methods exist, missing data is still an issue.

While exhibitions have been a continuous topic in art history, photographic records have not been studied with computational technologies so far. However, the exponentially increasing amount of visual data has resulted in great research activity in image search and retrieval; although approaches exist since the early 1990s, image search with visual queries has experienced great popularity in recent years (Zhou et al. 2017). Also, works in computer vision and digital art history have described the application of retrieval systems on art data. (Crowley and Zisserman 2014, 2016), detected objects in paintings using classifiers, which were trained on object-categories of natural images. However, approaches, which rely on natural images, are insufficient, because they do not adapt to the specific characteristics of art, such as abstraction or unknown object categories and thus, results are not convincing. Schlecht et al. (2011) used a detection system to retrieve identical and similar gestures in medieval manuscripts, also studying compositions and object relations Bell et al. (2013). Other work described the automatic retrieval of illustrations from a set of medieval ballad sheets Chung et al. (2014). A retrieval system to find visual links in artworks was created by Seguin et al. (2016). In 2018, the Google Arts and Culture Lab publicly announced an ongoing project with the MoMA. Scientists developed an algorithm, which searches through the collection of exhibition photographs to find matches with the works included in the MoMA’s online collection Museum of Modern Art, New York (2018). The present article can be assigned to both, to exhibition studies in art history and present work on object retrieval in computer vision. The investigation contributes to the state of research in that it studies photographic records of exhibitions with computational tools, which, to the knowledge of the authors, has not been done before. While the project of the Google Lab and the MoMA resembles the approach taken in this article, it presents completed work, where scholars are not actively engaged and can use the method for their own research. Eventually it has also missed to demonstrate how this can be used for art historical research. The used method in this article is thus very different to previous works, which analyzed exhibition displays manually, and because it mainly relies on visual data. We present a large scale study of exhibition photographs of the MoMA and examine the reappearance of singular artworks in shows over time. An approach, which has been rare in art history. Eventually, we aim to demonstrate that tracing back the exhibition history of artworks is an essential aspect of provenance research and hope to trigger further research in that field.

2. Studying Installation Views with Computational Methods

To examine art datasets, the Computer Vision Group of Heidelberg University has developed an interface for a visual search. Since 2009, the group hosts an interdisciplinary project between computer vision and art history, resulting in various projects, which applied object retrieval methods to art images to find similarities between artworks, identify (visual) patterns over time and reveal artistic networks Lang and Ommer (2018). So far, diverse image collections have been evaluated, including architectural prints, paintings of the Crucifixion of Christ and medieval manuscripts. The project team studied legal communication in the ’Sachsenspiegel’ (c1220) by retrieving most common gestures, determining their spatial relation and occurrence with other objects or motifs Bell et al. (2013), Schlecht et al. (2011), or a computational analysis of reproduction processes of medieval images Monroy et al. (2011). Currently, digital images of street art are being analyzed with the aid of the retrieval system: results will be presented in the following section. The present study benefits from previous works and analyzes a set of exhibition photographs, released by the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The next two sections introduce the interface and also give some additional information on previous projects, including search results and notes on failure cases.

2.1. An Interface for Visual Search

The Computer Vision Group has developed an interactive interface to search for image regions, selected by users, in large art-historical image collections. The interface operates on a search algorithm, where the previously selected query(ies) form the positive exemplar. For every image collection, uploaded and initialized on the interface, a set of generic negatives is created. To perform a search, the user is marking an image region, which is regarded as the one positive query exemplar; hand-crafted HOG features are used to extract the feature from the positive query. The histogram of oriented gradients (HOG) is a feature descriptor in computer vision, which provides edge orientation histograms and is particularly used for detection Dalal and Triggs (2005). An exemplar-based Support Vector Machine (SVM) is then used to train a classifier, where the user-selected query functions as the positive exemplar and the previously gathered generic negatives as negatives. SVMs are commonly used for classification, where a hyperplane is created in a higher dimensional space to separate data in two categories—in object detection, to distinguish between positive and negative retrievals in relation to the query Adankon and Cheriet (2009). A sliding window moves over all images in the dataset and the trained classifier extracts features for every region; the classifier then measures the similarity to the positive query feature for every feature. The highest rated image regions are displayed as results by the interface, thus not only showing identical but also similar regions to the query. A feedback system was introduced to refine the classifier, eventually providing better search results through additional (visual) information Takami et al. (2014). It is also important to note that while for other retrieval systems manual tagging is necessary, the used algorithm purely operates on visual image qualities, which is especially useful for unlabeled data; this is often the case for art image collections, where large number of the data are not labeled. The step-by-step use of the interface and its functions are described in the following section.

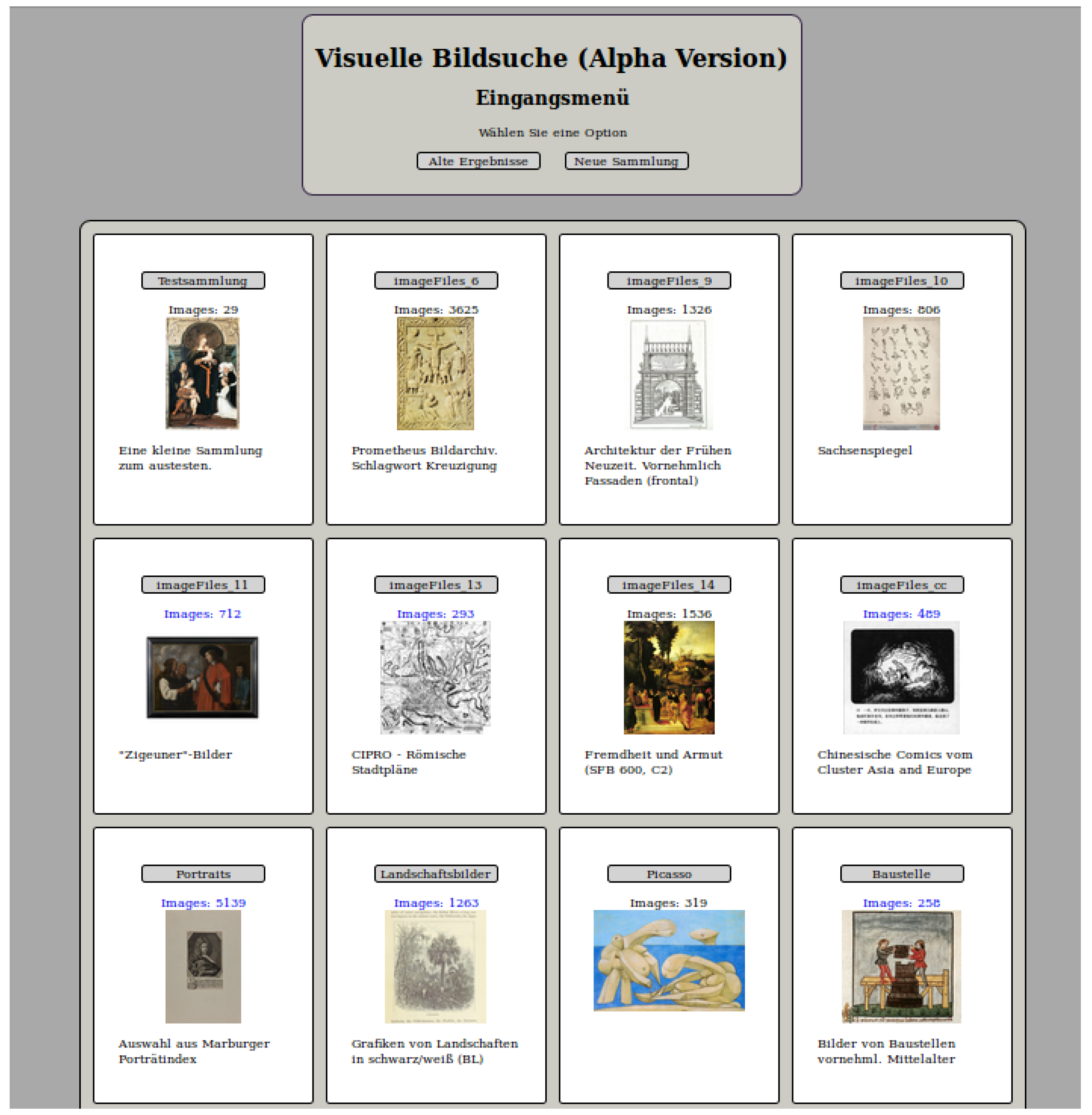

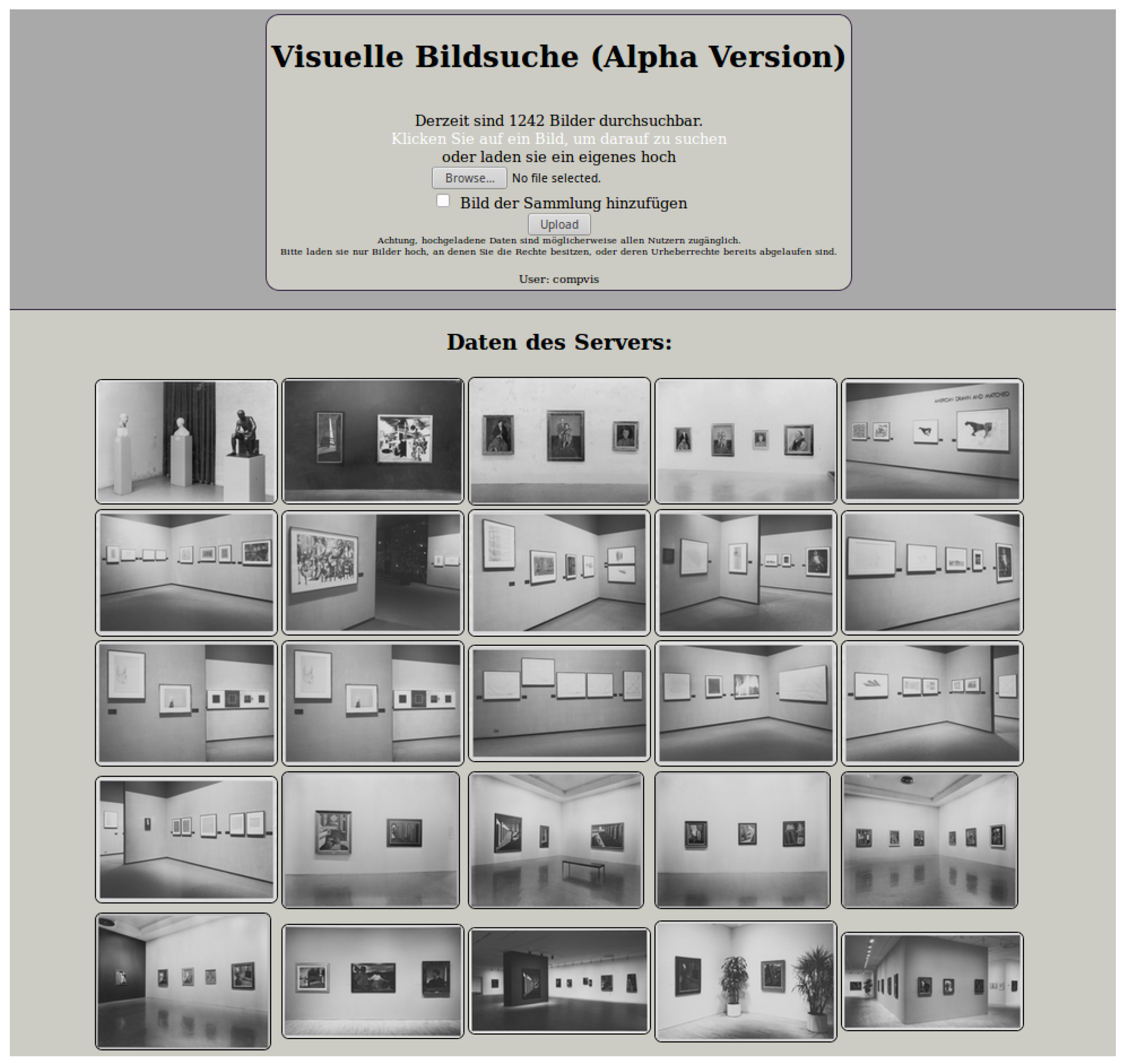

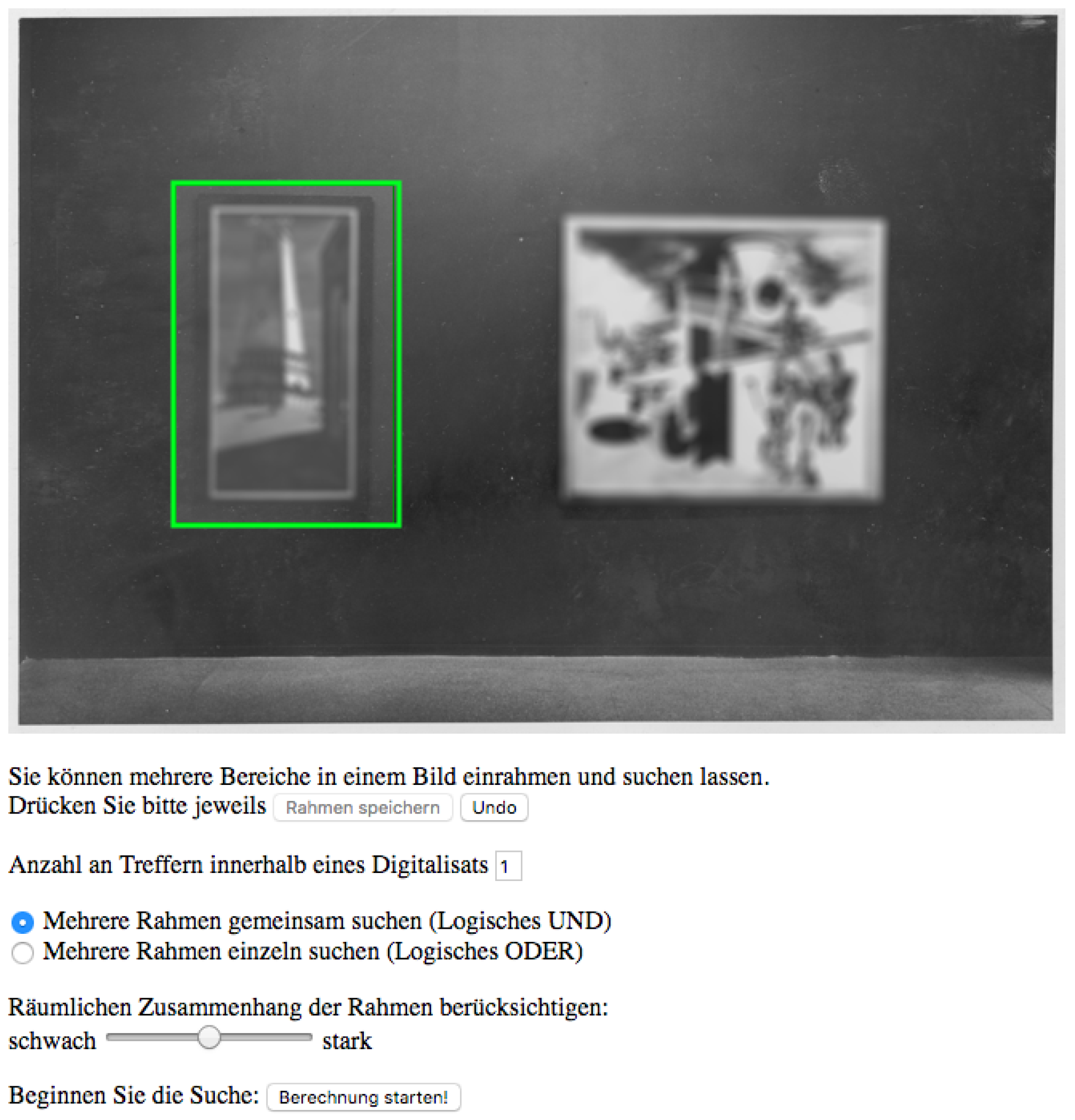

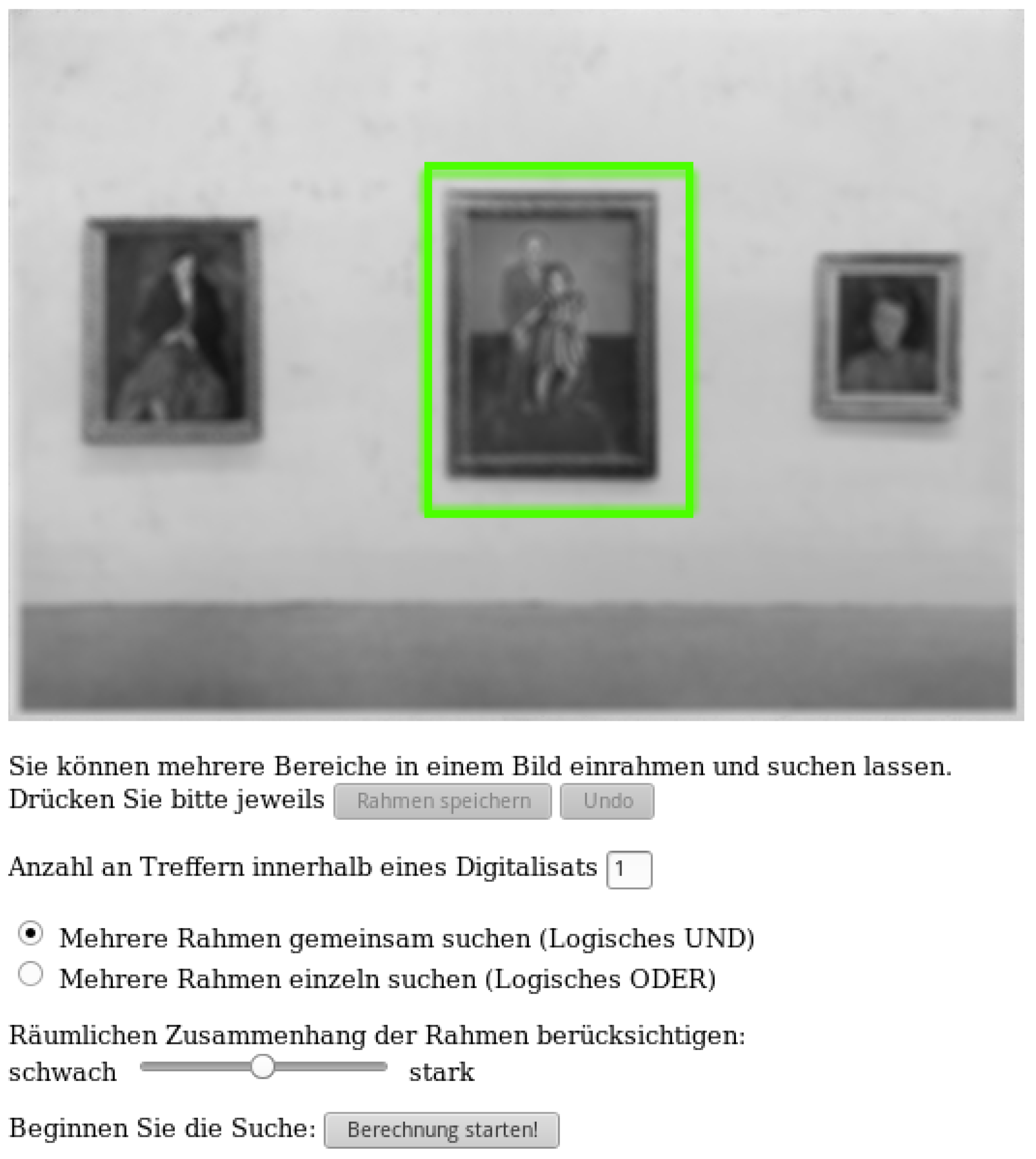

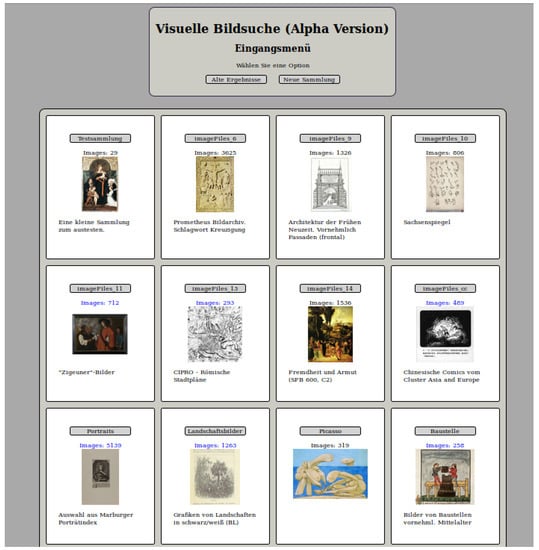

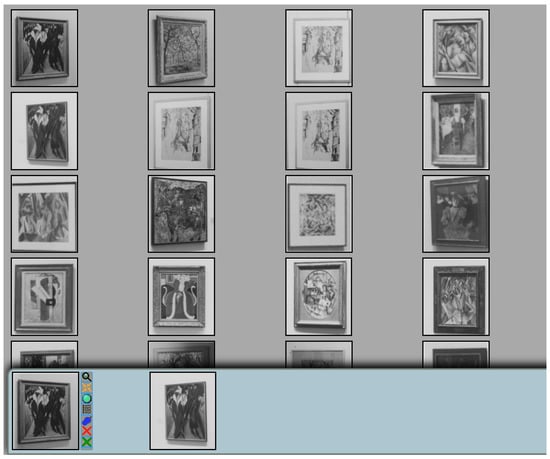

The retrieval system contains various image collections, which are displayed on the front page (Figure 1); the user is able to select one of the existing datasets or upload a new one. The initialization process uploads the images and corresponding metadata. Consequently, the collection can be used for image search; an overview of images included in selected dataset is provided, simplifying the selection process for users. After selecting an image, the user can mark up to five bounding boxes as queries and define spatial relations between individual regions, this is crucial, for example, for an iconographical analysis, which relies on specific compositions of figures and objects. Bounding boxes are tools to mark regions of interest, while also excluding the effect of the background (Zhou et al. 2017); examples of selected regions marked with bounding boxes can be seen in (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

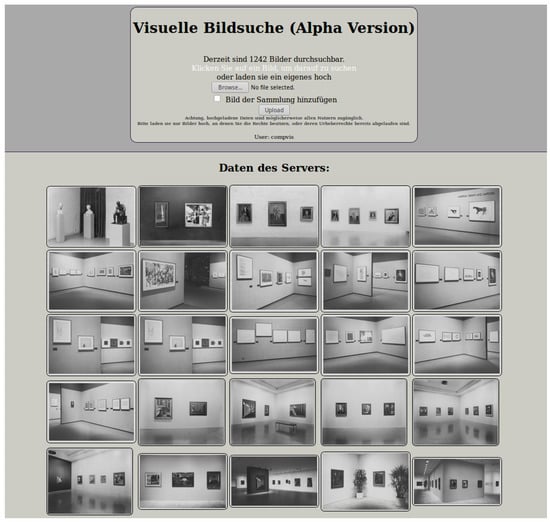

Figure 1.

Current image collections on the interface developed by the Computer Vision Group; the first row shows a test set, a collection of art, depicting the Crucifixion, architectural drawings and medieval manuscripts. Image rights: Computer Vision Group, Heidelberg University.

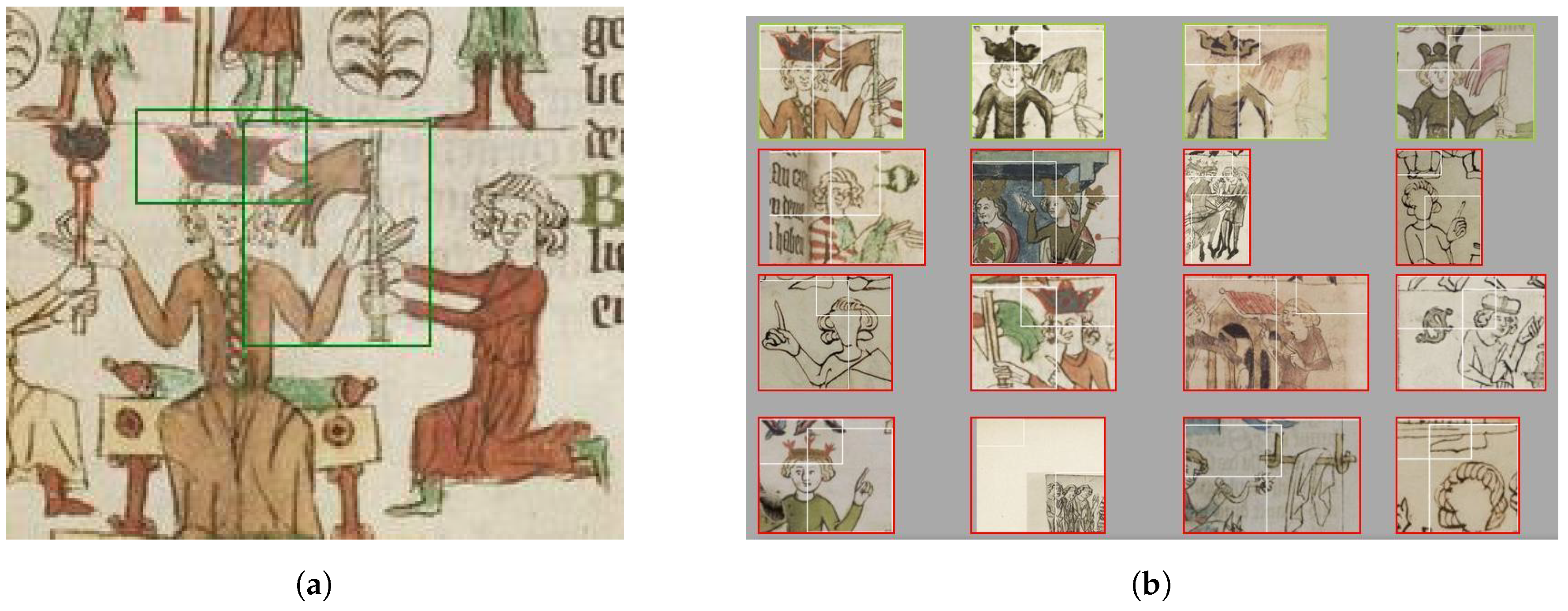

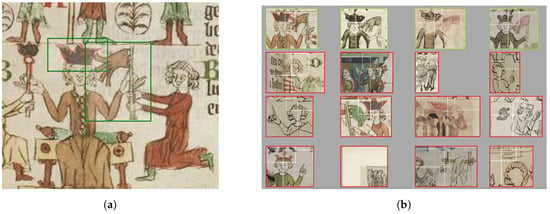

Figure 2.

(a) Shows the user-selected queries on a sheet from the Sachsenspiegel (c1220); (b) presents the obtained search results using the interface. Image rights: Heidelberg University Library, https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/cpg164.

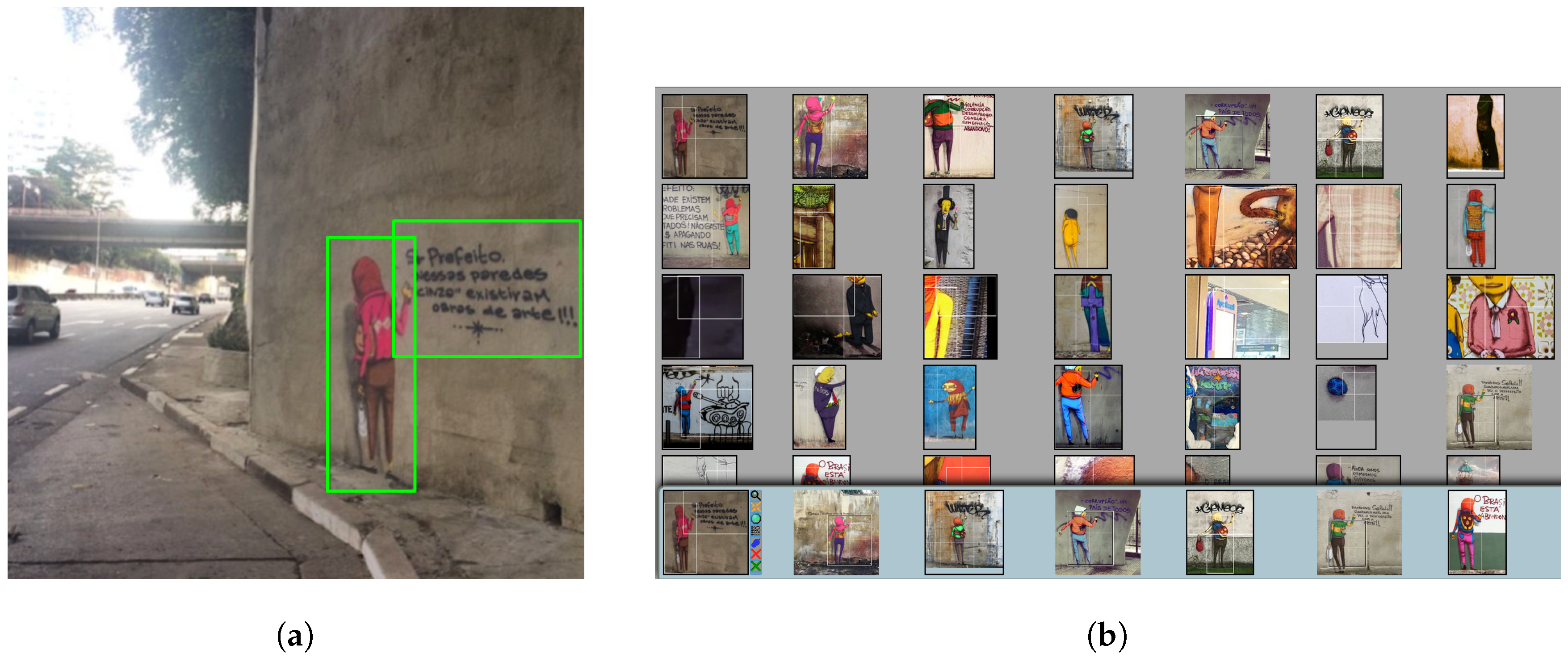

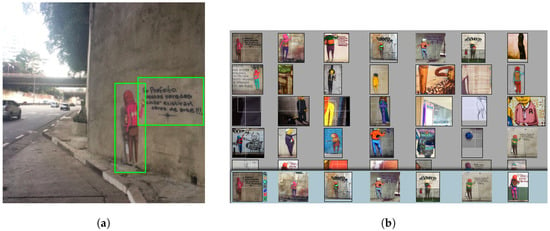

Figure 3.

(a) Shows the user-selected queries; (b) presents the obtained search results after the second training round. Image rights: Computer Vision Group, Heidelberg University. Displayed images are taken from the Instagram page of the artists ’OsGemeos’.

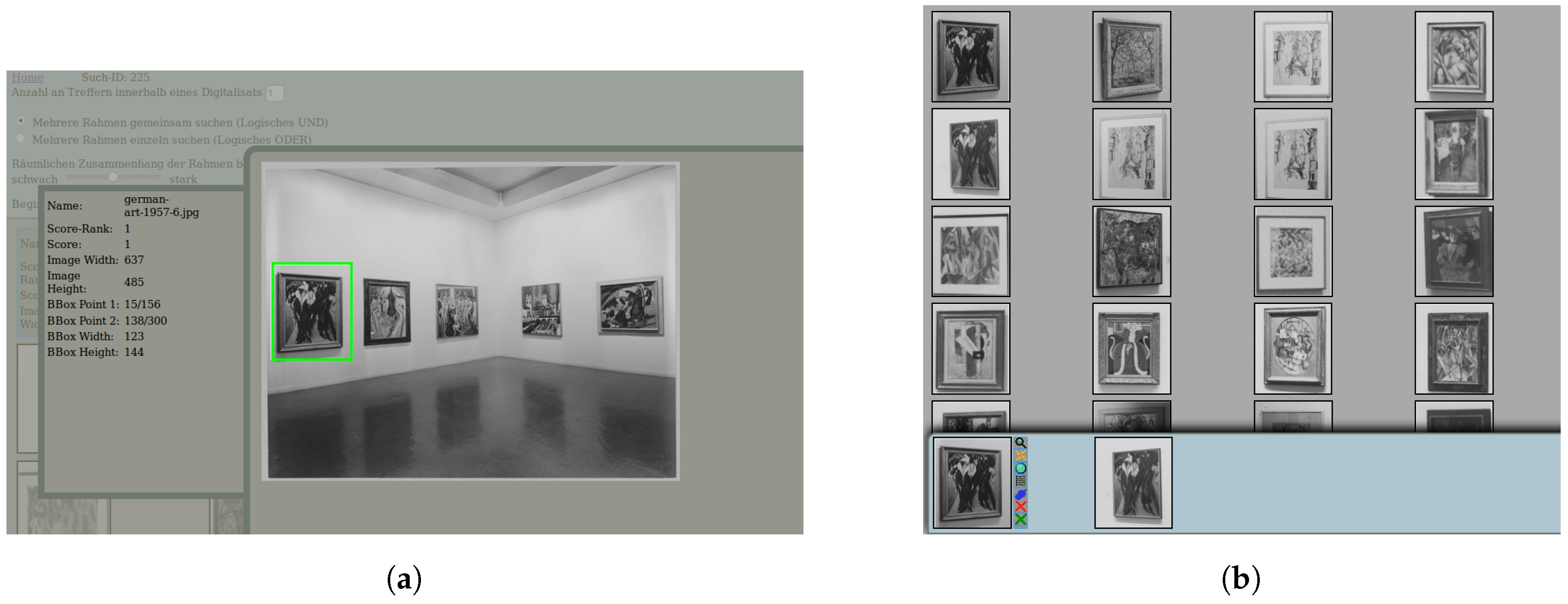

The user then triggers the search process, where results are being displayed in a new window, ordered with decreasing similarity. A user feedback, where positive results are marked in green and negatives in red, retrains the model and refines returned results. The interface offers additional features, such as to enlarge individual results, access metadata and pin positive results, which appear in a separate space and facilitate a comparative analysis (Figure 4). In the past, the tool was successfully tested on diverse image collections, where thematic scope, genre, technique and quality of digital reproductions varied. Despite this variety, the algorithm was able to perform well on all collections and proved its adaptability to different data and search queries. The website of the Computer Vision Group includes an overview of conducted work and shows more results on art data Computer Vision Group, Heidelberg University (2018).

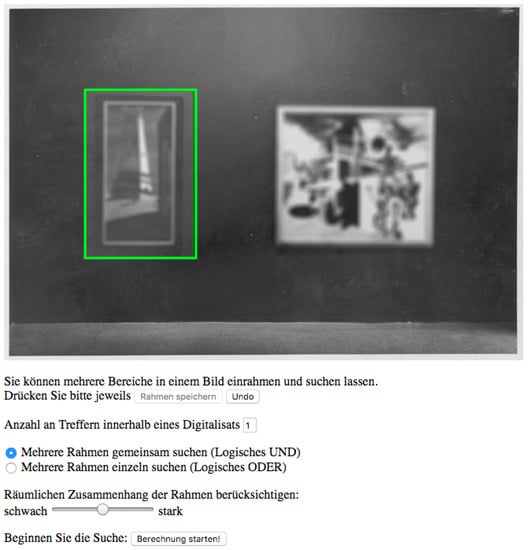

Figure 4.

(a) The interface offers the function to enlarge search results to view entire image and metadata; (b) pin function to separately display correctly retrieved images. Image rights: Computer Vision Group, Heidelberg University. Displayed photographs/details belong to the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

2.2. Performance Results on Other Datasets

Since 2009, the Computer Vision Group carries out interdisciplinary work, applying computational methods and tools—the interface being one—to diverse art historical data, such as medieval manuscripts, architectural drawings, religious paintings, and photographs of street art. This confirmed the efficiency of algorithms and encouraged to test the system on other challenging data: digital exhibition records of the MoMA being examples. However, to further promote the usefulness of retrieval tools for art historical research, and eventually for every visual discipline in the humanities, the following section wants to share additional performance results obtained by the interface on above mentioned data during past projects. Because of the limited scope, this section presents search results from medieval manuscripts and street art photography.

The interdisciplinary project team has analyzed the Sachsenspiegel (c1220), a medieval law book, using the interface to find recurring objects, study compositions and formal changes and developments. The manuscript exists in four versions, named after their current locations in Heidelberg, Dresden, Wolfenbuettel and Oldenburg, and contains heavily illustrated text sheets; the original version was produced by Eike von Repgow (c1180–c1235). Illustrations are standardized and identical and similar figures and objects reappear throughout the manuscript; unarguably, this standardization as well as clear object contours support a good retrieval performance; tests on the interface have shown that algorithms perform less confident on modern styles, such as Impressionism or Expressionism, where outlines are less distinct and objects are highly distorted. Also, reproduction quality is still a major issue, which influence performance and results of retrieval systems. Analyzing the Sachsenspiegel, the group was interested, for example, in gestures to study relations between figures and medieval communication. Because the interface also allows to select multiple regions, the authors also studied compositions: for the present search the user was interested in a crown and flag, which is depicted to the figure’s right (Figure 2). Algorithms retrieved identical and similar image regions to the query, allowing a formal comparison to identify developments or alterations due to, for example, aesthetic preferences of printers Lang and Ommer (2018). It can be concluded that the motif of the crowned figure with flag appears various times throughout the manuscript; while posture and positioning are almost identical, the form of crown and flag vary, also the general appearance of the figure.

The group is currently carrying out a project, using a dataset of street art photographs; the project is interested in repetitions of motifs across time and in different geographical locations, the positioning of street artworks in cities and relations between viewer, urban context and artwork. First tests were carried out to test the usability of the interface, since the data proposes new challenges to algorithms, such as large context regions, a great variety of motifs and styles and distortions due to perspective. Authors, for example, studied street artworks of Brazilian artists OsGemeos; we were interested in the figure seen from behind and a text to its right, where the spatial relation between the regions should be considered by the algorithm (Figure 3). Although first results were already sufficient, user feedback was provided to obtain even better results. Figure 3 displays the results after the second iteration. Relevant details were pined to simplify a comparative analysis; results highlighted that the artists used the figure quite frequently and that its appearance remains relatively similar, despite some color variations: cloths, backpack, posture, raised arm and invisible face are constants; the reading of the texts revealed that the artists addressed issues of their time, mostly relating to their hometown of São Paulo. The group was then interested in the tradition of the figure seen from behind and the use of text in art history. Both examples indicate, how retrieval systems can be used for art historical research and that algorithms perform well, even on challenging datasets; the present investigation will further demonstrate its efficiency.

2.3. The Data: Photographic Records of Exhibitions Held at the MoMA, New York

In the fall of 2016, the MoMA released a large set of archival material, which documents their exhibition history. It includes photographs of exhibitions, catalogs and press releases. Documents provide additional information about artists, displayed artworks, exhibition planning and involved curators; while the photographs are main sources for this article, other material is used to further enrich search results and analysis. Digital photographs of exhibitions give insight into past shows and, because of their sheer number, require new ways of analysis: can we evaluate these images with the help of computer vision? This article demonstrates how computational tools can be used to study the exhibition history of artworks and the artistic context in which they were shown. For evaluation purposes, a collection of exhibition photographs from the publicly available dataset of the MoMA was acquired. As of 30 July 2018, the museum provides digitized material for 4845 exhibitions, including bespoken photographs. The dataset consists of a selection of exhibitions, where each show is represented by a varying number of photographs. 48 exhibitions of the MoMA are included in the collection, which is used for this article, the earliest being the inaugural show ‘Cézanne, Gauguin, Seurat and van Gogh’, which opened on 7 November and closed on 7 December 1929. The latest is the 2013/14 exhibition dedicated to Belgian Surrealist René Magritte, entitled ‘Magritte: The Mystery of the Ordinary 1926–1938’, held from 28 September 2013 to 12 January 2014. The selection is reflective of the great variety of exhibitions staged at the MoMA from 1929 to the present day; it includes a variety of exhibition types, such as monographic and group exhibitions, exhibitions of the permanent collection or shows dedicated to the museum’s newest acquisitions. Also, different genres of art in a range of techniques are presented, such as sculptures, oil paintings, drawings, prints or photographs. Access to such a large dataset enables to ask research questions, which address universal issues and aim to find broader patterns; this requires innovative methods to answer them (Figure 5). Due to the nature of photographs, the data possesses new challenges for algorithms: rooms offer a perspective view and are therefore much more complex to grasp than well-aligned digital images of singular artworks. Also, artworks are multiple in exhibition views, vary in size and are mostly not presented parallel to the image’s margins but distorted, which makes it harder for the algorithm to detect individual works. Searching for single artworks in exhibition photographs is thus aggravated, also by additional decor, benches or plants, which might occlude artworks. Lastly, the lightning of the rooms creates stark contrasts in the photographs and therefore poses an additional challenge. All aspects require the algorithm to be very flexible and adaptable to visual variances in the dataset.

Figure 5.

The interface for visual search holds a collection of exhibition photographs as released by the Museum of Modern Art, New York. As expressed in the top region of the interface, at this point, in order to select a search region, users can either click on an existing image or upload a new one to the collection. Image rights: Computer Vision Group, Heidelberg University. Displayed photographs/details belong to the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

2.4. Studying Exhibition Photographs with Computational Tools

Earlier research has demonstrated the potential of computational object retrieval for art images; while these mainly detected objects, such as dogs, horses, figures or gestures, the present article uses identical models to find artworks. In this way, exhibition histories for artworks can be recreated. The present study demonstrates this, using exhibition photographs provided by the MoMA. Once other museums release comprehensive collections of installation photographs, this task can be significantly enhanced; allowing more detailed and encompassing statements about where and when artworks were shown, among which other artworks and if this varied for different museums. By connecting these exhibition views with additional digitized sources, such as other photographs and auction catalogs, one significantly extends the potential of computer-based methods, also for provenance research.

2.4.1. The Detection of de Chirico’s Nostalgia of the Infinite (c1912–c1913)

A large tower dominates Giorgio de Chirico’s (1888–1978) metaphysical painting ‘The Nostalgia of the Infinite’ (c1912–c1913, oil on canvas, MoMA). Sunlight illuminates the image and cuts it in two halves; the place in front of the tower is deserted with the exception of two figures, whose silhouettes are still visible but soon might disappear. The oil painting was executed in 1912/13 and first sold to the Parisian art dealer Paul Guillaume (1891–1934) in 1918 and was eventually acquired by the MoMA in December 1936 through the Galerie Bonaparte in Paris—as the provenance entry on the museum’s website states. The interface was used to search for de Chirico’s work in the MoMA’s exhibition images; the painting was selected in an installation photograph from the ‘Painting and Sculpture from the Museum Collection’ show, which was held between 23 October 1940 and 12 January 1941 (Figure 6). The archival material for the exhibition also holds a ‘Master Checklist’, where all included works are listed, a press release and four installation photographs.

Figure 6.

User’s selection of Giorgio de Chirico’s The Nostalgia of the Infinite on the Interface. As expressed in the region beneath, users can define, if the algorithm should search for both queries or also for single ones. Image rights: Computer Vision Group, Heidelberg University. Installation view taken from the exhibition “Painting and Sculpture from the Museum Collections.” 23 October 1940– 12 January 1941. Photographic Archive. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. IN110.1B.

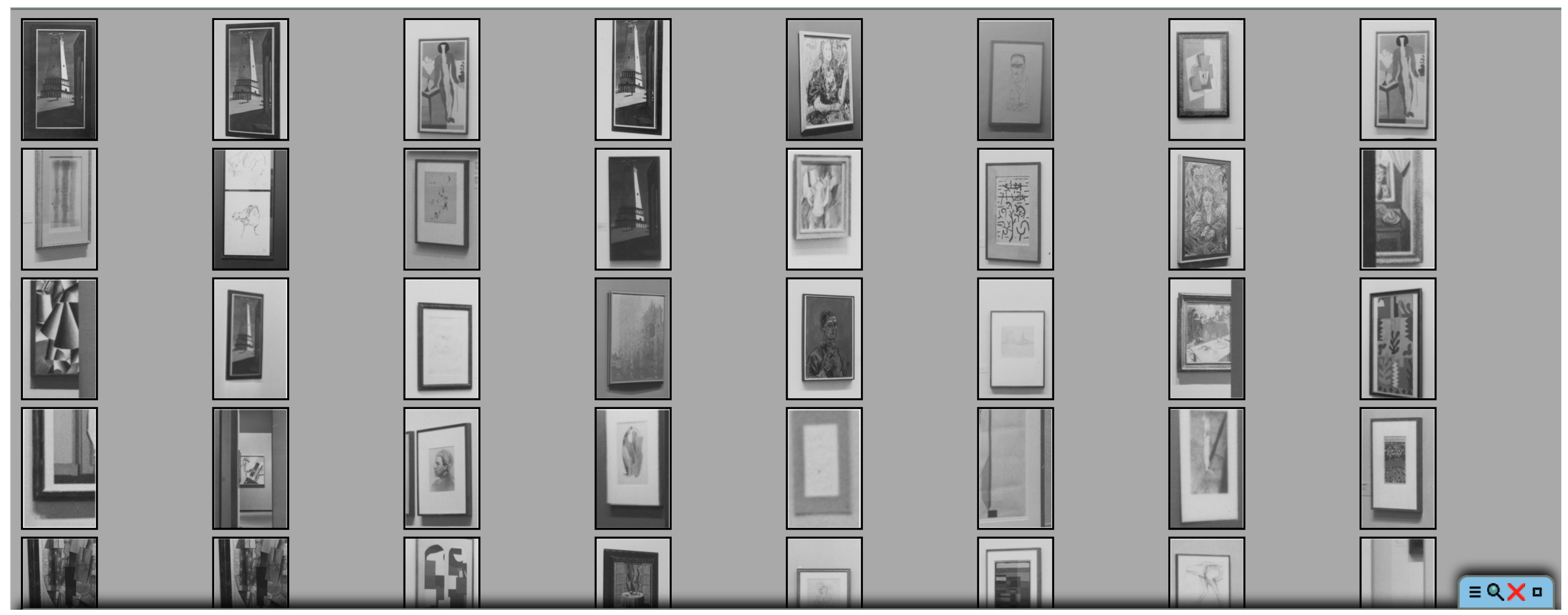

In the query image, de Chirico’s painting is shown next to ‘Parade’ (1930), an oil painting by American artist Peter Blume (1906–1992); the latter was acquired in 1935 and has been a part of the museum’s collection ever since. Blume confronts the viewer with an industrial landscape: the painting is dominated by a surreal factory, positioned along a diagonal line; the sky appears to threaten the scenery, emphasized by contrasting clouds of white and dark color. In the right foreground, we see a man holding a knight’s armor; he is about to leave the image’s reality, thus entering the viewer’s world. The armor suggests his metamorphosis into a mechanical being. Blume used different tones of white and gray and highlights in red and yellow to create his surreal landscape. His works are often linked to Surrealism, which ultimately validates his connection to de Chirico. For the search, the user marked de Chirico’s work with a bounding box; after initializing the search, results are presented in another window, visualized in rows of eight in decreasing similarity (Figure 7): evidently, algorithms were able to retrieve de Chirico’s ‘The Nostalgia of the Infinite’ (1912–13) correctly. His work was found in four other exhibitions, correct retrievals are included in the first three rows of the results’ page. Information about exhibitions can be concluded from the metadata, which is provided for every single image and saved on the interface; once results are given for a search query, this information can be accessed through the system. Besides the 1940 show, ‘Nostalgia of the Infinite’ was included in ‘Paintings, Sculpture, and Graphics form the Museum Collection’ (2 July 1946, until 12 September 1954), ‘Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism’ (7 December 1936, until 17 January 1937), ‘Permanent Collection Exhibition’ (29 March 1972, until 21 April 1980) and the Giorgio de Chirico solo exhibition (6 September until 30 October 1955). The confident findings encourage to look at individual exhibitions in more detail and study in which artistic context the image was shown and if that changed over time. As stated, the query painting is exhibited in the ‘Painting, Sculpture, and Graphics from the Museum Collection’ exhibition; the installation photograph shows it alongside Blume’s ‘Parade’; unfortunately, this is the only link the image reveals, since other artworks are not visible. Because of the relatively small set of photographs for this show (only four), other photographic records provide no further information about other artworks, with which de Chirico’s painting was presented. However, the ‘Master Checklist’ Museum of Modern Art, New York (1940) lists both paintings in the section ‘Magic Realism’; thus, it can be assumed that other works in this category hung in close proximity or indeed formed a group. In this case, ‘The Nostalgia of the Infinite’ would have been displayed alongside Blume’s ‘Parade’, de Chirico’s ‘Toys of a Prince or Evil Genius of a King’ (oil on canvas, 1914–15), Dalí’s ‘The Persistence of Memory’ (oil on canvas, 1931) and ‘Portrait of Gala’ (oil on canvas, 1935), Max Ernst’s ‘The Nymph Echo’ (oil on canvas, 1936), Richard Oelze’s ‘Expectation’ (oil on canvas, 1936), Pierre Roy’s ‘Danger on the Stairs’ (oil on canvas, 1927–28) and ‘Agricultural Conference’ (oil on canvas, c1930), Yves Tanguy’s ‘Mama, Papa is Wounded!’ (oil on canvas, 1927) and Henri Rousseau’s ‘The Sleeping Gypsy’ (oil on canvas, 1897). Creation dates for individual works reveal that most have been painted during the late 1920s and 1930s, with Rousseau’s Gypsy being an exception and that all are linked to Surrealism. In this way, de Chirico’s work was mainly presented alongside contemporaries and precursors. The exhibition introduced him as a forerunner of Surrealism—as such he was viewed by Surrealist artists, who celebrated his mystical, deserted architectural views. Regarding style, de Chirico’s artwork was presented within a homogeneous group of works; assumingly it was not the intention of the curator to display contrasting images in order to highlight differences. However, minor semantic contrasts can be found within the group. Although artists’ nationalities and connections to specific art movements and groups varied, all images exemplified a strong preference for figuration, depicted dream-like worlds and used bright colors—with the exception of Tanguy, who included abstract elements. As an example, the urban landscapes of de Chirico or Blume were opposed to Max Ernst’s nature-dominated representation of the nymph or Rousseau’s depiction of a sleeping gypsy in the desert. Depictions of natural fertility were contrasted against images of desertedness—as seen in the paintings of de Chirico or Dalí.

Figure 7.

Search results using the interface for Giorgio de Chirico’s The Nostalgia of the Infinite. Image rights: Computer Vision Group, Heidelberg University. Displayed photographs/details belong to the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Four years prior to the Museum Collection exhibition, the painting was included in the ‘Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism’ show, which presented an extensive overview of one of the two most important art movements of modernity. At the time of the exhibition’s opening, Dada was already superseded, while Surrealism was internationally established and at a height; Surrealist groups in various European cities and numerous exhibitions, such as the ‘International Surrealist Exhibition’ held in the New Burlington Galleries in London in 1936, exemplify this. The exhibition at the MoMA presented a great number of works, dating back to the sixteenth century, such as Hans Baldung Grien’s ‘Seven Horses Fighting in a Wood’ (woodcut, 1534). De Chirico and his paintings (in total, 10 oil paintings and 16 drawings were shown) were again linked to a Surrealist tradition. Doing so, the show of 1936/1937 already picked up, what would be visible in the ‘Museum Collection’ exhibition in 1940. However, in the section, where de Chirico’s work was shown, organizers exclusively placed him among his own works. An installation shot shows ‘The Nostalgia of Infinite’ next to ‘Toys of a Philosopher’ (1917), ‘The Duo’ (1914–15, MoMA) and ‘Mystery and Melancholy of a Street’ (1914) (see photograph 1). All paintings were executed around the same time and are representative of de Chirico’s classical metaphysical style, showing deserted cityscapes, mannequins and stark contrasts of light. At least within this spatial section, the painting was not positioned within a greater art historical context, but remained positioned within de Chirico’s oeuvre—creating a homogeneous group of works. However, if we consider the entire exhibition, links to the past and to forerunners of modern art movements were certainly emphasized. The next search result links to the ‘Painting, Sculpture, and Graphic Arts from the Museum Collection’ exhibition, which again included de Chirico’s work and opened its doors in 1946; the more permanent show remained on display until 1954. For the first time an exhibition was staged at the newly remodeled galleries on the second floor, where all except for two were used for showcasing the museum’s collection of paintings Museum of Modern Art, New York (1946). Alfred H. Barr Jr. (1902–1981) was responsible for the hanging and organization of the exhibition: “Installing the painting galleries has been a problem of compression. The new space, now permanently set aside on the second floor, has made available three additional galleries for the Museum Collection, yet there is even now room for only 120 paintings. […] In the remaining galleries varieties of lyric fantasy, dream realism, and factual painting include the work of Klee, Masson, Graves, Tanguy, de Chirico Dix, Sheeler, and others” Museum of Modern Art, New York (1946).

Indeed, the installation photograph (see photograph 2) shows two of de Chirico’s works— ‘The Nostalgia’ and ‘The Evil Genius of a King’—on one wall, opposing Tanguy’s abstract painting ‘Slowly Toward the North’ (1942) and Ernst’s ‘Two Children Are Threatened by a Nightingale’ (1924). Similar to the ‘Museum Collection’ show in 1940, the exhibition of 1946 showed de Chirico’s work within a Surrealist tradition. This might indicate that the exhibit—maybe museum collection shows in general—were arranged in homogeneous groups, representing established styles, themes, or artists, rather than in a contrasting manner. This is further validated when looking at other installation photographs of the same exhibition: an image shows a room dedicated to post-Impressionist artists, such as Cézanne and van Gogh, whose ‘Starry Night’ (1889, oil on canvas) is visible in the right corner. This observation is validated by previous remarks on the presentation of de Chirico’s work in shows by the MoMA, which also elaborated on the homogeneity of displays. Scholars have indeed noted that historically group or mono-graphic exhibitions4 were organized chronologically, geographically or according to themes; this structure represented the Western art historical canon and is visible in the mentioned shows, which include the Italian artist’s works. It was not until the 1990s, with the reflexive turn, that traditional practices were criticized and new curatorial approaches were taken: new forms of representation were established, which were interdisciplinary, offered a critical perspective on canonical knowledge and created new contexts for artworks. Also museum collection shows aimed to showcase the quality and diversity of the collection and announce the museum’s identity—this was at least one main purpose of exhibits until the 1990s Grießer (2013). A collection thus had a specific purpose, being aesthetically, economically or because of personal taste, and was gathered accordingly; also, collections seldom remained static, but changed and increased over time. By exhibiting their collection, the MoMA publicly proclaimed their identity and thematic focus. It must be added however that these shows only displayed a small number of the collection, which were additionally curated and picked according to a specific pre-defined purpose Simmons (2016). The ’Master Checklist’ (Museum of Modern Art 1940) of the 1940 show, presenting the museum’s collection, reveals that various artists and styles were included, however, most of them were European; this was representative of the zeitgeschmack. Almost twenty years after the previous show ended, the MoMA staged another exhibition dedicated to its extensive permanent collection (Permanent Collection, 29 March 1972 until 21 April 1980). Again, de Chirico’s image of the infinite tower was displayed; an installation view (see photograph 3) displays it next to ‘The Anxious Journey’ (1913, oil on canvas) and ‘Gare Montparnasse’ (1914, oil on canvas), both painted by the Italian artist. The subsequent walls show Rousseau’s ‘Sleeping Gypsy’ (1897, oil on canvas) and two other paintings, which were not identifiable. However, most likely they are from an earlier period, possibly around the late nineteenth century, because of their stylistic similarity to the works of Odilon Redon. Unfortunately, no archival material is given for this exhibition, so no further information was provided. Exhibiting de Chirico in close proximity to Rousseau resembles the arrangement in the ‘Painting and Sculpture from the Museum Collection’ exhibition (1940). Interestingly, both shows displayed the museum’s own collection but were held under different directors, namely Barr and Richard Oldenburg (1972–1995). For the show in 1940, Barr was again responsible for the hanging, for the exhibition in 1972, it is unclear whether Oldenburg was actively engaged in the installation or if it was the sole responsibility of one of the MoMA’s curators. However, since both displayed works of the museum’s collection, it can be assumed that similar installation practices and forms of representation are employed; not least, because exhibits, dedicated to the collection, had specific aims and purposes, namely to promote the museum’s taste and present masterworks, which testify to the collection’s quality. Other installation photographs of the ‘Permanent Collection’ exhibition (1972) illustrate that rooms were dedicated to Cubism (Braque, Picasso, Roger de la Fresnaye), Expressionism (Kokoschka), ‘Der Blaue Reiter’ or Abstract Art. Artists were mixed and works grouped together according to specific styles. In conclusion, the show presented an overview of the major (European) art movements and some of the most prominent works within the MoMA’s collection. While de Chirico’s ‘The Nostalgia of the Infinite’ was repeatedly shown in group exhibitions so far, the next search result assigns it to a show, which was held in 1955. Entitled ‘Giorgio de Chirico’ (6 September until 30 October 1955), it was solely dedicated to the Italian artist. An exhibition shot (see photograph 4) displays the oil painting ‘The Enigma of a Day’ (1914, oil on canvas) to its left and ‘Ariadne’ (1913, oil on canvas) to its right. This artistic context is highly similar to the ‘Fantastic Art’ exhibition (1936), organized by Barr, where de Chirico’s painting is also exhibited among his own works. The show gathered twenty of his most famous paintings, mainly from his early metaphysical period, visualizing popular characteristics, such as abandoned city streets, mannequins and dark/bright contrasts. The show was directed by James Thrall Soby, curator of the MoMA, and installed by Margaret Miller (Associate Curator of Painting and Sculpture), under the directorship of Rene d’Harnoncourt (1949–1968) Museum of Modern Art, New York (1955).

2.4.2. The Detection of Balthus’ portrait of Joan Miró and his Daughter Dolores (1938)

To demonstrate the consistency of the algorithm, the interface was used to search for Balthus’ (1908–2001) portrait of ‘Joan Miró and his daughter Dolores’ (1938, oil on canvas, MoMA). The Spanish artist is portrayed sitting on a chair with his daughter, who stands between his legs; their gazes directly confront the spectator, captivating him with their undivided attention. The room, in which the scene takes places, seems empty, almost abandoned. The Paris-born artist chose brownish, very muted colors for his double portrait. Again, the interface developed by the group was used to search for the portrait; the same process as described for the example of de Chirico was triggered: the 1940 exhibition of the museum’s collection includes an installation photograph, where Balthus’ work is visible (Figure 8); a bounding box was used to mark the painting and then the search was initiated. Similar to de Chirico’s search, the algorithm performed well and detected the artwork four times, as can be seen on the results’ page, where retrievals are shown in declining similarity (Figure 9). The first three images in the first row show Balthus’ work, followed by an image of another artist and then again followed by the portrait of Miró and his daughter. How incorrect retrievals might be interpreted will be discussed at a later stage in this paper. As stated, the first result is from the 1940 exhibition of the ‘Museum Collection’. To its right, Christian Bérard’s ‘Jean Cocteau’ (1928, oil painting) was exhibited, the left painting could not have been identified. Cocteau is depicted in half-length and parallel to the viewer; he is dressed in an orange shirt, set against a brown background. A loose brush stroke and application of paint suggest a short execution time of the painting. The second search result stems from the same exhibition; the painting was found in another exhibition photograph (see photograph 5). The photograph reveals additional links to other works; the image of Miró and his daughter was shown alongside Franklin Chenault Watkins’ ‘Boris Blai’ (1938, oil on canvas); Blai is shown in half-length, with his body turned to the left and directly looking at the viewer. Similar to Bérard, the artist used muted brownish tones, which he applied very loosely to the canvas. The show of 1940 embedded Balthus’ work within a group of portraits—the ‘Master Checklist’ reveals that the group also included Oskar Kokoschka’s ‘Portrait of Dr. Tietze and his Wife’ (1909, oil on canvas) and ‘Self Portrait’ (1913, oil on canvas) Museum of Modern Art, New York (1940). The group presented a mix of nationalities, where the Expressionistic style and the genre were constants tying works together. This corresponds to historical exhibition practices, where artworks were organized and displayed in homogeneous groups Grießer (2013).

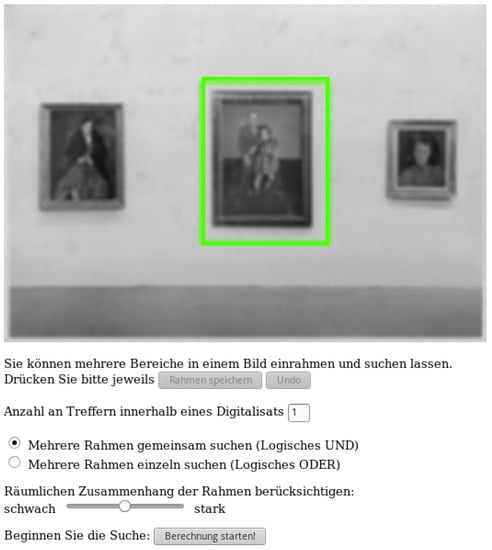

Figure 8.

User’s selection of Balthus’ portrait of Miró and his daughter Dolores on the Interface. Additionally, users can define, if the algorithm should search for both queries or also for single ones. Image rights: Computer Vision Group, Heidelberg University. Installation view taken from the exhibition “Painting and Sculpture from the Museum Collections.” 23 October 1940–12 January 1941. Photographic Archive. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. IN110.2A.

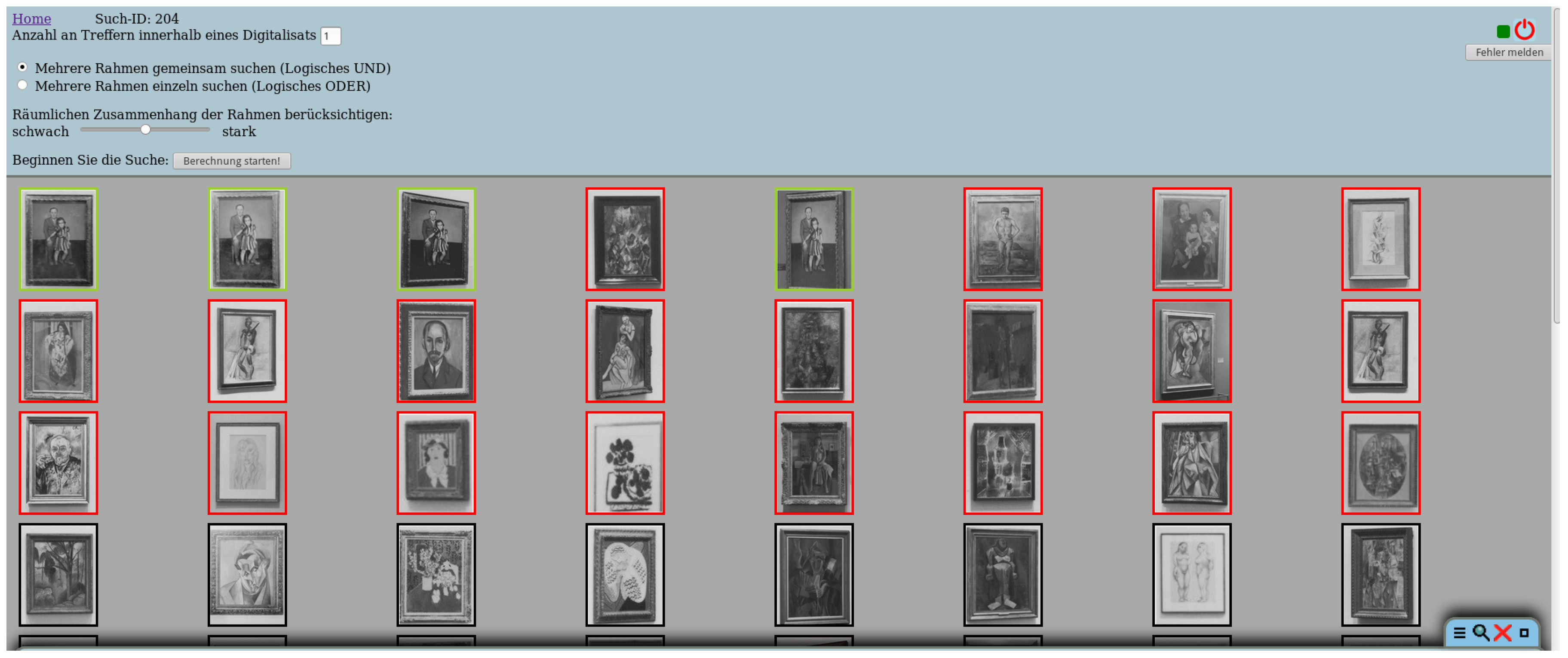

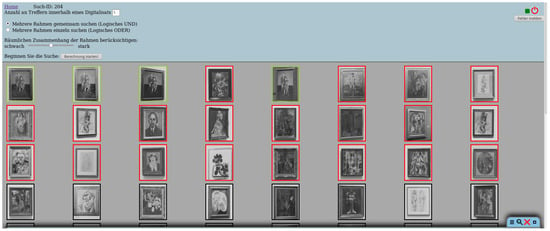

Figure 9.

Search results for Balthus’ Joan Miró and His Daughter Dolores (1937, MoMA), first search process, figure shows user’s feedback, where positive detections are marked in green, negatives in red. Previously defined search constraints are visible at the top. Image rights: Computer Vision Group, Heidelberg University. Displayed photographs/details belong to the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Balthus’ image was again included in the exhibition entitled ‘Portraits from the Museum Collection’ (4 May–18 September 1960) twenty years later. The corresponding installation shot provides further information about the artistic context in which the painting was displayed (see photograph 6). To its right, Balthus’ portrait of André Derain (1936, oil on canvas) was hung, followed by two works by the French artist Christian Bérard ‘On the Beach—Double Self Portrait’ (1933, oil on canvas) and ‘Jean Cocteau’ (1928, oil on canvas). On the far right, the photo shows the portrait of ‘Boris Blai’ (1938, oil on canvas) by Watkins. The exhibition thus showed a group of works, which are very similar in terms of date and style. All paintings were created in the 1930s—with the exception of Bérard’s portrait of Jean Cocteau—and painted in an Expressionistic style. The group is almost identical to the one in the ‘Museum Collection’ exhibition of 1940, where Bérard’s Cocteau and Watkins portrait were also shown alongside the portrait of Miró. The last result shows Balthus’ work in the ‘Modern Masters: Manet to Matisse’ exhibition (5 August–28 September 1975) (see photograph 7). The retrieval of this result is surprising since the painting in the photograph is highly distorted by the perspective and small in scale. However, the algorithm was able to detect it, which testifies to the efficiency of the developed interface. The shot includes a large number of paintings and reveals the following works (from left): Balthus’ ‘The Mountain’ (1936–37, oil on canvas), Yves Tanguy’s ‘Fear’ (1949, oil on canvas), Matisse’s ‘Large Interior in Red’ (1948, oil on canvas), Giacometti’s ‘Peter Watson’ (1953, oil on canvas) and ‘The Apple’ (1937, oil on canvas), Miro’s ‘Maternity’ (1924, oil on canvas) and ‘Diana’ (1931, oil on canvas) by German painter Paul Klee. The exhibition catalog, which is available online, provides additional information: “[the exhibition] surveys almost a century of European painting which starts with Manet in 1861 and closes soon after the death of Matisse in 1954. The selection has been conceived in eight chapters: Impressionism; Post-Impressionism; Matisse […]; Expressionism […]; Cubism […]; the “painted dream”, which in this exhibition refers to painters of fantasy before, during, and after Surrealism; portraits, a personal predilection […] and last […] ten painters of the School of Paris […]” Museum of Modern Art, New York (1975). Groups displayed the full variety of art, suggesting an interconnected reading of the paintings—Balthus’ portrait is seen among Surrealist imagery, abstract as well as figurative paintings. Whereas previous exhibitions mainly exhibited Balthus’ work within a portrait tradition, the present show places it within a less homogeneous group, including different styles, motifs and artists’ nationalities. Assumingly, the aim was to present the variations known in modern art, resembling more modern approaches, which less reflected canonical knowledge Grießer (2013). Previous exhibitions mainly focused on presenting the image among other portraits; ‘Modern Masters’, however, enlarges the artistic context in which the query is shown.

While the interface is able to detect the query image in the set of exhibition photographs correctly, the search process also retrieves results, which are not identical to the query, but regarded as similar by the algorithm. These additional images are not relevant for the exhibition history of the specific artwork, but might suggest new and interesting links. General observations can be obtained from the results (Figure 9): other images mainly consist of portraits, which are characterized by a central alignment of a figure, a simple background or style, similar to Balthus’ Expressionism. The first row shows Paul Cézanne’s ‘The Bather’ (c1885, oil on canvas), presently in the MoMA’s collection; although the painting was executed more than fifty years before the query image, its style and general composition bears resemblance to Miró’s portrait. The bather is shown in the center of the image, accentuating a vertical line, which divides the painting almost in equal parts. This is comparable to Balthus’ portrait, where Miró and his daughter also emphasize strong vertical lines, while the transition between floor and background additionally creates a distinct horizontal line. The background, consisting of different shades of blue and a rocky landscape, is simple and also suggests a horizontal line. Because of its reduced content and central position of the figure, the painting is easy to comprehend and Balthus’ image eventually inherits the same qualities. Cézanne’s image of the bather was exhibited in the 1929 exhibition dedicated to van Gogh, Gauguin and Seurat; an installation shot reveals that it was shown among other portraits, including Cézanne’s ‘Portrait of a Man in a Blue Cap’ (or ‘Uncle Dominique’, c1866, oil on canvas) and ‘Harlequin’ (1890, oil on canvas), Paul Gauguin’s ‘Melancholic’ (1891, oil on canvas), followed by Cézanne’s ‘Self-Portrait with Beret’ (1890, oil on canvas). The show thus presented the male figure of the bather among other portraits, mainly by Cézanne. By identifying Cézanne’s work as similar to Balthus, the algorithm detected an image, which is not only formally similar, but was also displayed among a very homogeneous group of works—an obervation, which has been made for Balthus’ portrait also. The motif of the bather was again detected in Picasso’s ‘Bather’ (1908–09) as shown in the second row, last image on the right. Although executed in a Cubist style and holding a white towel in his left hand, the figure, its composition and background indicate a strong link to Cézanne’s male figure, which was painted almost twenty years prior. Again Picasso’s work displays similar qualities to the paintings of Cézanne and Balthus; it is thus comprehensible why the interface would suggest a similarity between the three paintings. The third image in the second row shows Henri Matisse’s ‘Portrait of Michael Stein’ (1916, oil on canvas), which was included in the ‘Henri Matisse Retrospective’ in 1993, where it was presented among a group of portraits. In contrast to the painting by Balthus, which showed a full-length figure—the present work portrays Stein in half-length. He is positioned parallel to the viewer, his suit and background are painted in different shades of brown. While prior works bore greater resemblance to Balthus’ work, it is less obvious, why the algorithm detected the portrait. When contrasting both images, it is evident that both artists used a similar color palette –mainly brown tones–, style and facial expression. Comparing exhibition photographs highlights that Matisse’s work was embedded within a similar group of artworks than Balthus’ painting. Curators and directors of the MoMA— in this case Richard Oldenburg for ‘Henri Matisse: A Retrospective’, 1992 and Alfred H. Barr for ‘Cézanne, Gauguin, Seurat, van Gogh’, 1929 and ‘Painting and Sculpture form Museum Collection’, 1940—thus preferably hung works of identical genres together. The result page shows another work by Matisse, namely his oil painting ‘Nude with a White Towel’ (1902–1903), which depicts a female nude standing next to a chair in a brightly colored room. The motif is more similar to Cézanne, Picasso and Balthus’ Miró than the portrait of Stein, because it shows a figure in full-length, depicted at a central position in the image. Concluding, it is noticeable that most of the retrieved artworks are full-length portraits, with the exception of Matisse’s ‘Michael Stein’ (1916), characterized by a central alignment and similar in style to Balthus’ portrait; most works presented a reduced visual language and results were considered to be similar to the query image because of formal and semantic qualities.

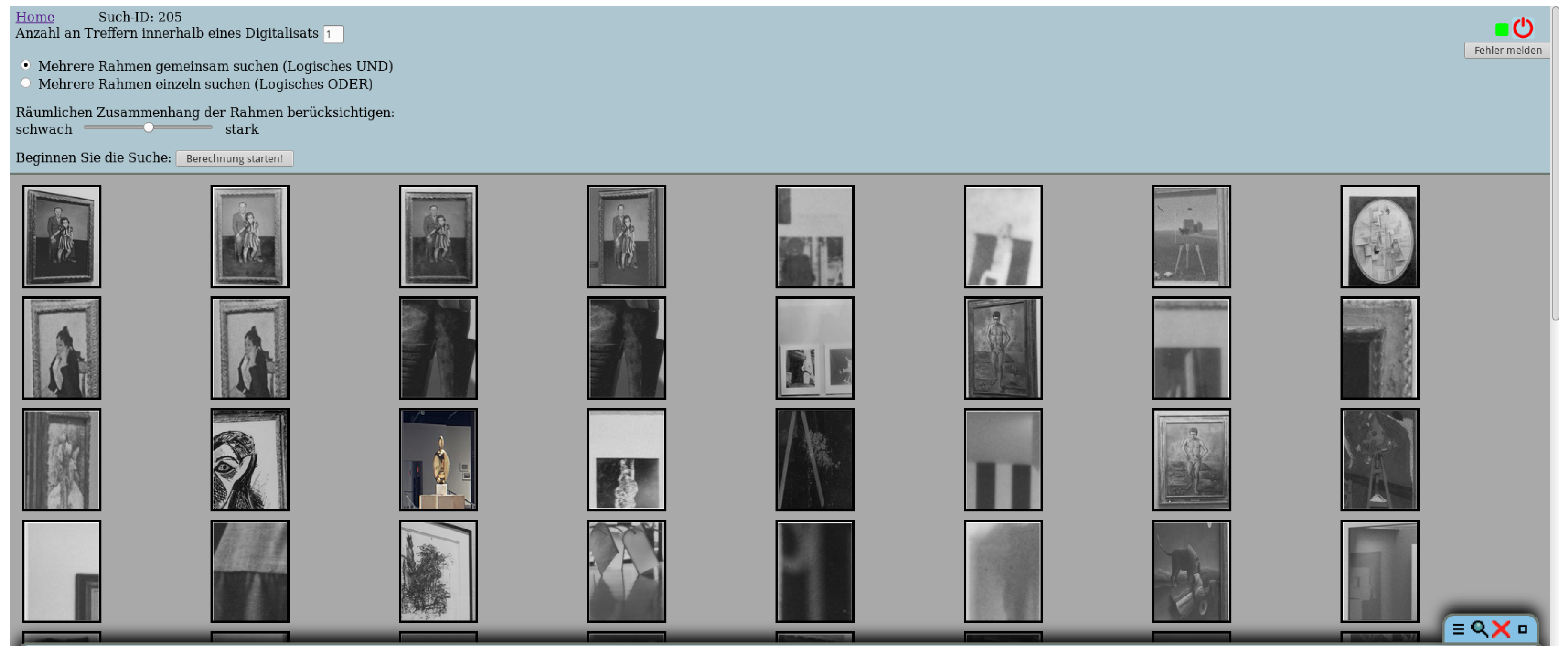

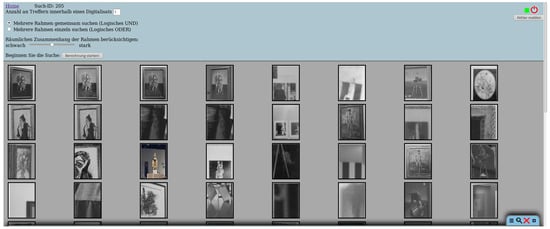

The second search, based on the user’s evaluation of the results, leads to improved results and possibly to new findings and connections. In the case of Balthus’, a second round was initialized to demonstrate the usability of the interface, based on the user’s feedback; the four detected paintings by Balthus were marked as positive, others in red (Figure 9). Results revealed that detections were rather similar to the first round and did not improve significantly, a first search already provided satisfying results (Figure 10). However, it is noticeable that a new work appears: the second row now features Vincent van Gogh’s ‘L’Arlésienne’ (Mme. Ginoux) (1888), which was displayed in the van Gogh exhibition (1935–1936). Again, the algorithm’s detection indicates a strong connection to Balthus’ work, because both are portraits and similar in terms of central alignment and formal qualities.

Figure 10.

Search results for Balthus’ Joan Miró and His Daughter Dolores (1937, MoMA), second search process based on user’s feedback; van Gogh’s painting L’Arlésienne (Mme. Ginoux) (1888) is highlighted. Previously defined search constraints are visible at the top. Image rights: Computer Vision Group, Heidelberg University. Displayed photographs/details belong to the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

3. Discussion

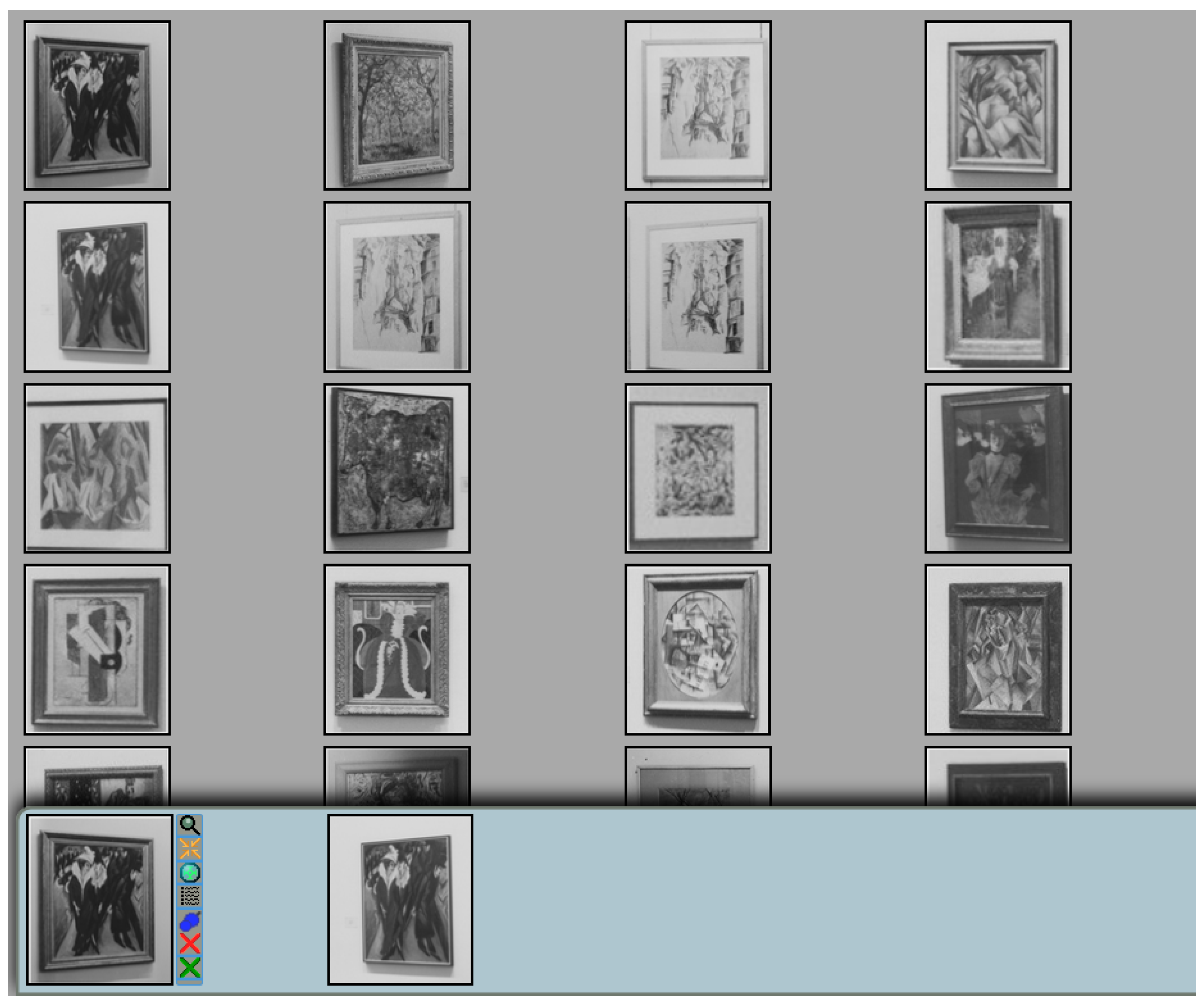

The task of object retrieval is highly relevant for art history to evaluate large datasets, which would be impossible to do manually; the authors have presented an interface for visual search, developed by the Computer Vision Group. In contrast to text searches, it does not rely on metadata, which is often erroneous or completely missing and thus complicates searches. It has been shown that the system of the group is applicable to diverse image sets, including different techniques, genres or styles. Eventually, it was developed to be actively used by scholars, who have different research questions and aims. Tests have proven that the interface can successfully detect artworks in exhibition photographs; this article has demonstrated how this can be used for art historical research: to find exhibitions, where the image was included and study in which artistic context selected artworks were presented. Other results further validate its usefulness: Figure 11 shows search results for Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s ’Street, Berlin’ (1913, oil on canvas, MoMA), which was included in the ’German Art’ show in 1957 and the ’Permanent Collection’ exhibit (29 March 1972 to 21 April 1980). The exemplary search for de Chirico’s ‘The Nostalgia of the Infinite’ revealed that different directors tended to display paintings among a similar group of artworks. In the ‘Museum’s Collection’ (1940) and ‘Permanent Collection’ (1972) shows, ‘The Nostalgia’ was displayed in close proximity to Henri Rousseau’s ‘Sleeping Gypsy’, suggesting a semantic and formal connection; this was also the case for Balthus’ portrait of Miró and his daughter. The homogenity of display groups is a constant throughout the MoMA exhibits, which have been discussed in this article, and are representative of historical practices Grießer (2013).

Figure 11.

Search results for Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s ’Street, Berlin’, 1913. Image rights: Computer Vision Group, Heidelberg University. Displayed photographs/details belong to the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

The previous section has also highlighted, how ‘incorrect’ retrievals can be used for art historical research. Systems for object retrieval might thus be used to study the exhibition history and artistic context of an artwork; the article presented an innovative application of computer-based methods, which is of great assistance to art historians—also with the great potential to propel provenance research. The release of digital archival material, including photographic records of museum displays, catalogs, press-releases and checklists, by the Museum of Modern Art has enabled to ask and answer questions related to exhibition histories and displays with innovative methods. By adding other archival material and connecting, so far, separate digital collections, this method offers the opportunity to study exhibition displays on large scale, over time and space.

This article also aimed to highlight the potentials of applying computational methods to art data and the necessity of interdisciplinary work—in this case computer vision and art history. However, these methods can only work in combination with traditional methods and human efforts. Computer-based methods certainly do not replace, but rather assist art historians with their work, where obtained results must be assessed in order for methods to improve and disciplines to progress. Object retrieval is relevant for many visual disciplines and the article aimed to demonstrate its wide applicability on very diverse data. Eventually, studying objects or image regions is very much related to the issue of establishing links between images and finding similarities and therefore is reflective of similar questions raised in the whole of humanities.

4. Sources

This research article has heavily relied on the availability of exhibition data, as provided by the Museum of Modern Art, New York. An initial dataset was released in the fall of 2016, but has since been extended. As of 27 July 2018, the museum’s website holds data for 4845, including exhibition photographs, catalogs, press releases and other archival documents. All image rights belong to the Photographic Archive, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. The following is a list of all referenced visual archival material and contains accession numbers for images displayed and referred to in this article. Cited written documents are incuded in the reference list, but also belong to the archival material of the MoMA. Also, details (Figure 2a,b) from the medieval manuscript of the Sachsenspiegel have been presented; full digitized images can be found under the following link: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/cpg164, University Library, Heidelberg. Lastly, Figure 3a,b shows images taken from the Instagram page of Brazilian street artists OsGemeos https://www.instagram.com/osgemeos/?hl=en.

Exhibition Photographs

Photograph 1. installation view of the exhibition ’Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism’, 7 December 1936–17 January 1937. Photographic Archive. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. IN55.8A. Photograph by Soichi Sunami [online] https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2823/installation_images/12548?locale=en, accessed 9 May 2018.

Photograph 2. installation view of the exhibition, ‘Paintings, Sculpture and Graphic Arts from the Museum Collection’, 2 July 1946 [unknown closing date]. Photographic Archive. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. IN324.4. Photograph by Soichi Sunami [online] https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2856/installation_images/14618?locale=en, accessed 9 May 2018.

Photograph 3. installation view of the exhibition, ‘Permanent Collection’, 29 March 1972 [unknown closing date]. Photographic Archive. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. IN1002.21. Photograph by Katherine Keller [online] https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1919/installation_images/23497?locale=en, accessed 9 May 2018.

Photograph 4. installation view of the exhibition, ‘Giorgio de Chirico’, 6 September 1955— 30 October 1955. Photographic Archive. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. IN583.2. Photograph by Soichi Sunami [online] https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1967/installation_images/20969?locale=en, accessed 9 May 2018.

Photograph 5. installation view of the exhibition, ‘Painting and Sculpture from the Museum Collections’, 23 October 1940—12 January 1941. Photographic Archive. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. IN110.2B [online] https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2813/installation_images/13112?locale=en, accessed 9 May 2018.

Photograph 6. installation view of the exhibition, ‘Portraits from the Museum Collection’, 4 May 1960—5 July 1960 (Auditorium and First Floor); 6 July 1960—18 September 1960 (Auditorium re-installation). Photographic Archive. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. IN664.2. [online] https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2806/installation_images/17647?locale=en, accessed 9 May 2018.

Photograph 7. installation view of the exhibition, ‘Modern Masters: Manet to Matisse’, 5 August 1975—28 September 1975. Photographic Archive. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. IN1105.10. Photograph by Katherine Keller [online] https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1894/installation_images/23624?locale=en, accessed 9 May 2018.

Author Contributions

S.L. conducted the data collection, analysis using the interface for visual search and the interpretation of obtained results. B.O. contributed to the creation of the interface for visual search, supervision and revisions to the manuscript.

Funding

“This research was partly funded by the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences and Humanities.”

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the Computer Vision Group of Heidelberg University for their support, input regarding computer-based approaches and words of encouragement. In particular, thank you to Nikolai Ufer for his general help and providing information about the method and interface and to Anja Lang for proofreading the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adankon, Mathias M., and Mohamed Cheriet. 2009. Support vector machine. In Encyclopedia of Biometrics. Berlin: Springer, pp. 1303–8. [Google Scholar]

- Altshuler, Bruce. 2009. Exhibitions that made art history. Salon to Biennial 1: 1863–959. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Peter, Joseph Schlecht, and Björn Ommer. 2013. Nonverbal communication in medieval illustrations revisited by computer vision and art history. Visual Resources 29: 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertron, Aurelia, Ulrich Schwarz, and Claudia Frey. 2006. Designing Exhibitions: A Compendium for Architects, Designers and Museum Professionals. Basel: Birkhäuser. [Google Scholar]

- Brantl, Sabine. 2007. Ein Ort und seine Geschichte im Nationalsozialismus. München: Haus der Kunst. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, Joon Son, Relja Arandjelović, Giles Bergel, Alexandra Franklin, and Andrew Zisserman. 2014. Re-presentations of art collections. Paper presented at Workshop at the European Conference on Computer Vision, Zurich, Switzerland, September 6–12; Berlin: Springer, pp. 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Computer Vision Group, Heidelberg University. 2018. Digital Humanities. Available online: https://hci.iwr.uni-heidelberg.de/compvis/projects/digihum (accessed on 31 July 2018).

- Crowley, Elliot J., and Andrew Zisserman. 2014. In search of art. Paper presented at Workshop at the European Conference on Computer Vision, Zurich, Switzerland, September 6–12; Berlin: Springer, pp. 54–70. [Google Scholar]

- Crowley, Elliot J., and Andrew Zisserman. 2016. The art of detection. Paper presented at European Conference on Computer Vision, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 8–16; Berlin: Springer, pp. 721–37. [Google Scholar]

- Dalal, Navneet, and Bill Triggs. Histograms of oriented gradients for human detection. Paper presented at IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2005, San Diego, CA, USA, June 20–26; vol. 1, pp. 886–93.

- Grießer, Martina. 2013. Handbuch Ausstellungstheorie und -Praxis. Cologne and Weimar: Böhlau Vienna. [Google Scholar]

- Klüser, Bernd, and Katharina Hegewisch. 1991. Die Kunst der Ausstellung: Eine Dokumentation Dreissig Exemplarischer Kunstausstellungen Dieses Jahrhunderts. Berlin: Insel Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, Sabine, and Björn Ommer. 2018. Attesting similarity: Supporting the organization and study of art image collections with computer vision. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroy, Antonio, Bernd Carqué, and Björn Ommer. 2011. Reconstructing the drawing process of reproductions from medieval images. Paper presented at 2011 18th IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Brussels, Belgium, September 11–14; pp. 2917–20. [Google Scholar]

- Museum of Modern Art, New York. 2018. Identifying Art through Machine Learning. Available online: https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/history/identifying-art (accessed on 31 July 2018).

- Museum of Modern Art, New York. 1940. Master Checklist of the Exhibition, “Painting and Sculpture from the Museum Collections.” 23 October 1940–12 January 1941. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York [online]. Available online: https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_master-checklist_325192.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2018).

- Museum of Modern Art, New York. 1946. Master Checklist of the Exhibition, “Paintings, Sculpture and Graphic Arts from the Museum Collection.” 2 July 1946 [unknown closing date]. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York [online]. Available online: https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_press-release_325522.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2018).

- Museum of Modern Art, New York. 1955. Master Checklist of the Exhibition, “Giorgio de Chirico”, 6 September 1955–30 October 1955. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York [online]. Available online: https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_press-release_325996.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2018).

- Museum of Modern Art, New York. 1975. Exhibition Catalog of the Exhibition, “Modern Masters: Manet to Matisse.” 5 August 1975–28 September 1975. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York [online]. Available online: https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_1894_300298301.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2018).

- Nicholls, John Anthony. 2006. Das Galeriebild im 18. Jahrhundert und Johann Zoffanys “Tribuna”. Ph.D. dissertation, Universitäts-und Landesbibliothek Bonn, Bonn, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- O’Doherty, Brian. 1999. Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Doherty, Brian. 2012. Atelier und Galerie. Berlin: Merve. [Google Scholar]

- Pöhlmann, Wolfger. 2007. Handbuch zur Ausstellungspraxis von AZ. New York: Mann, vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Schlecht, Joseph, Bernd Carqué, and Björn Ommer. 2011. Detecting gestures in medieval images. Paper presented at 2011 18th IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Brussels, Belgium, September 11–14; pp. 1285–88. [Google Scholar]

- Seguin, Benoit, Carlotta Striolo, and Frederic Kaplan. 2016. Visual link retrieval in a database of paintings. Paper presented at European Conference on Computer Vision, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 8–16; Berlin: Springer, pp. 753–67. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, John E. 2016. Museums: A History. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Takami, Masato, Peter Bell, and Björn Ommer. 2014. An approach to large scale interactive retrieval of cultural heritage. Paper presented at Eurographics Workshops on Graphics and Cultural Heritage, Darmstadt, Germany, October 6–8; pp. 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Wengang, Houqiang Li, and Qi Tian. 2017. Recent advance in content-based image retrieval: A literature survey. arXiv, arXiv:1706.06064. [Google Scholar]

| 1. | The interface is available for other scholars upon request. Inquiries can be send to sabine.lang@iwr.uni-heidelberg.de. |

| 2. | The article is referring to the Museum of Modern Art in New York, when it uses ’Museum of Modern Art’ or the abbreviation ’MoMA’ in the text, also in references to archival material or other sources. |

| 3. | The following article uses the term ’installation’ to refer to museum displays of artworks and not to the modern genre of installation. Also the phrase ’installation views’, in this context, always refers to photographic records of museum displays instead of the genre ’installation’. |

| 4. | Art history and museum studies generally distinguish between group and monographic exhibitions; these can be organized chronologically, thematically or geographically. Museums then display objects from their own collection or items on loan from other institutions. Versions of our modern museums already existed before Christ; then palace rarities, church treasuries and cabinets of curiosities are generally seen as predecessors. The modern museum, however, emerged in the Age of Enlightenment and experienced its first climax around 1800. More information on the (modern) museum and its history can be found in Simmons (2016). |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).