Abstract

Designers are increasingly involved in creating ‘popular’ data visualizations in mass media. Scientists in the field of information visualization propose collaborations between designers and scientists in popular data visualization. They assume that designers put more emphasis on aesthetics than on clarity in their representation of data, and that they aim to convey subjective, rather than objective, information. We investigated designers’ criteria for good design for a broad audience by interviewing professional designers and by reviewing information design handbooks. Additionally, we investigated what might make a visualization aesthetically pleasing (attractive) in the view of the designers. Results show that, according to the information designers, clarity and aesthetics are the main criteria, with clarity being the most important. They aim to objectively inform the public, rather than conveying personal opinions. Furthermore, although aesthetics is considered important, design literature hardly addresses the characteristics of aesthetics, and designers find it hard to define what makes a visualization attractive. The few statements found point at interesting directions for future research.

1. Designing Information Visualizations for a General Audience

This explorative study takes the perspective of the producer of mass media information visualizations and addresses three issues that hitherto have only been amply discussed in theoretical and applied literature on information visualization.1 What is the role and relative importance of clarity and attractiveness? Do designers aim to present objective information or convey subjective meaning? What makes an information visualization attractive? The study is based on a collection of statements and opinions with respect to these issues which have been derived from two sources: interviews with professional designers and information design handbooks which are recommended and frequently consulted by information designers.

Traditionally, information visualization techniques have been developed mainly for science and statistics, and were first and foremost meant to allow expert users to explore and analyze data quickly and accurately. In the past decades, however, many collections of data have become freely available, and so has software for data visualization. As a result, an increasing number of designers have started to apply visualization techniques to create data visualizations for popular purposes. At the same time, the intended audiences of those visualizations has expanded from expert users to include various groups of lay users as well (Vande Moere and Purchase 2011). The increasing popularity of data visualizations is also testified by the growing number of books for non-expert users that provide guidelines for data visualization to be used by non-scientific readers and showcase a huge variety of popular data visualization techniques (e.g., Klanten 2008; McCandless 2009). Among the designers involved in creating popular data visualizations are many graphic designers and other types of designers such as interaction designers, who have been educated at art and design academies2. Novel ways of visualizing data have been developed for business, government, newspapers, magazines, and internet platforms. These popular forms of data visualization are not only meant to allow an efficient and accurate reading of the data, as in science, but also to inform broad audiences about facts and developments in society. Consequently, designing such data visualizations may call for other design criteria than those applied to design graphs meant to serve scientific, analytical purposes. In this study, we are especially interested in those other criteria.

Some researchers in the scientific field of information visualization assume that aesthetic criteria are a key factor in communicating quantitative information to broad audiences (e.g., Judelman 2004; Kosara 2007; Lau and Vande Moere 2007; Vande Moere and Purchase 2011). Studies have shown relationships between aesthetics and usability (Cawthon and Vande Moere 2007). But researchers in this field also propose collaborations between scientists and designers so as to strike an adequate balance between information value on the one hand and aesthetics on the other, i.e., between clarity and attractiveness. They thus implicitly assume that aesthetics is part of the expertise of designers. This discussion may suggest a dichotomy between clarity and attractiveness. That would not do justice to studies which have shown that clarity may lead to attractiveness (e.g., Ngo et al. 2003) or that beauty can be found in a balance between opposites such as order and chaos (e.g., Berlyne 1971). However, scientists in the field of information visualization suggest that designers of popular data visualizations do not seek such a balance, but instead tend to put more emphasis on attractiveness than on clarity. As Vande Moere and Purchase put it: “(…) complex and socially relevant issues might best be communicated to a large audience through popular media using an artistic and engaging visualization (even if its designer knows that such a method is not the most effective or efficient).” (p. 361). According to Kosara (2007, p. 634) ‘artistic’ and ‘pragmatic’ forms of visualizations even seem irreconcilable: “Visual efficiency does not play a role in artistic visualization, quite the contrary. The goal is not to enable the user to read the data, but to understand the basic concern.” Related to this latter quote is the assumption made by several researchers that designers intend to convey subjective meaning underlying the data, rather than objectively presenting data and facilitating insight in the data (e.g., Kosara 2007; Lau and Vande Moere 2007). Designers would employ “ambiguous and interpretative methods” in order to engage the user and provoke personal reflection (Gaver et al. 2003), and their designs are supposed to involve subjective decisions and stylistic influences, and to be highly interpretative (Lau and Vande Moere 2007).

The assumptions described above reflect the way some scientists in the field of information visualization and human–computer interaction think about characteristics of popular information visualizations. But how do designers themselves think about these matters? The way designers visualize information is not well documented. Designers are used to working on the basis of intuition and experience, rather than explicit knowledge. As researchers in the field of InfoVis claim, designers can play an important role in helping a broad audience make sense of the enormous amount of available data nowadays. It would be helpful to know more about their ways of working in order to be able to strike a balance between the art and science of information visualization. But designers are not used to documenting their ways of working and thinking. As Schön (1983, p. 42) states: “When asked to describe their methods of inquiry, they speak of experience, trial and error, intuition, and muddling through.” Science can shed light on the mechanisms at work in design and eventually lead to design guidelines based on empirical evidence, instead of intuition alone. After all, in many cases intuitions and expert opinions about visualizations appear not to be conform their actual effectiveness (Hegarty 2011). At the same time, the design field lacks a self-definition that supports research into design in its own terms (Storkerson 2006). Cross (1982) has convincingly argued that design forms a third culture, besides sciences and humanities, with its own values, beliefs, and ways of knowing. In order to be able to better understand design, and improve design education, it is necessary not only to study design products, but also to gain a better understanding of designers’ ways of thinking. Therefore, in the present study, we take the perspective of the designers as the producers of popular data visualizations as a starting point.

To shed light on the criteria for popular information visualizations from the perspective of designers, we interviewed 10 professional designers. In addition, several handbooks on information design were reviewed in search for criteria for information visualization for a general audience. The selected handbooks can be assumed to reflect ‘best practices’ in information design because they are recommended by the International Institute for Information Design (IIID); an authoritative institution in the field of information design; and because they are frequently consulted by designers.

In particular, we focused on the following three questions:

- 1.

- How do designers look upon the relative importance of clarity and attractiveness in information design?

Any message, be it casted verbally or visually, is created with the objective of being understood by the intended audience. Therefore, the message should, first and foremost, be clear and understandable. At the same time, however, in order to be notified in the first place, the message must attract and hold attention; in other words the message has to be attractive for the intended audience. In this study, we consulted designers about what they consider to be the most important criterion in designing visualizations. Do they consider clarity to be more important or attractiveness? Or do they consider clarity and attractiveness equally important?

- 2.

- What position do designers take in objective representation of data vs. providing subjective interpretation in visualizing information?

When people use language, they have many conventional signals at their disposal to differentiate between expressing objective vs. subjective content (modal verbs, different types of connectives, etc.). When designers communicate messages using the visual modality, they arguably also aim at expressing either objective knowledge or subjective interpretations of it. However, the visual modality may not have a conventionalized set of signals to mark the difference between facts and opinions. So, the question is whether designers differentiate between these two types of information in their designs, and, if so, how they mark this distinction. With the interviews and literature review, we wanted to investigate the opinions of designers with respect to this objective–subjective issue.

- 3.

- What do designers consider the defining characteristics of attractiveness in information design?

Scientific studies in information visualization usually do not offer explicit hypotheses about what might make an information visualization attractive. Aesthetics is a very complex notion, and several theories and studies have been constructed and conducted about features of aesthetics (e.g., Hekkert 2006; Reber et al. 2004). Some studies start from the theoretical assumption that novelty (or related notions like originality, innovativeness, or uniqueness) is a factor ‘causing’ attractiveness (e.g., Lavie and Tractinsky 2004), while others state that especially experts (in art) are attracted to novel and complex, instead of familiar and simple stimuli (McWhinnie 1968; Bourdieu [1979] 1987; Gombrich 1995). Other theories suggest that attractiveness is a matter of striking a balance between, for example, novelty and familiarity, or between simplicity and complexity (e.g., Berlyne 1971). Yet other studies conjecture that attractiveness results from familiarity and experienced ease of use (Zajonc 1968, 1984; Reber et al. 2004), or from specific design features such as being embellished or abstract (e.g., Levy et al. 1996) or using certain color palettes (Fabrikant et al. 2012). We wondered what the designers’ views would be on what characteristics contribute to attractiveness of information visualizations.

The first two questions represent scales with dichotomous terms discussed by researchers as being important criteria for ‘good design’: clarity vs attractiveness, and objectivity vs. subjectivity. In the remainder of the chapter we will refer to these scales using the first term (clarity, objectivity). Of course, there may be other criteria that are possibly important for popular visualizations, such as memorability, but we chose to focus on the criteria as mentioned by these researchers in information visualization. The third question is an open question concerning features of attractiveness in information visualization.

We collected answers from designers in two ways. First, we interviewed 10 professional designers who are regularly involved in information visualization for broad audiences about their standards and ways of working. Second, we selected relevant fragments from recommended and frequently consulted design handbooks.

2. Interviews and Literature Review

2.1. Method

Interviews: 10 semi-structured interviews were conducted with professional designers.

Participants: interviewees were 10 professional designers who are used to designing data visualizations for general audiences. Their educational backgrounds were: graphic design (4), interaction design, computer sciences, industrial design, journalism, mathematics and graphic design, and journalism and industrial design. They were selected for at least one of the following three reasons: (i) having been rewarded with prestigious design prizes (Infographics Jaarprijs (7), Dutch Design Award (1), Malofiej Award (1)); (ii) leading the infographics department of a Dutch national newspaper (2); and (iii) being regular speakers at information design conferences (7), such as the Infographics Jaarcongres (Dutch yearly infographics conference).

Procedure: the designers were approached first by e-mail and then by telephone. They were informed that the goal of the interview was to gain more insight in their working methods and criteria for good design; that the interviews were part of an ongoing PhD research, and that the results would be published anonymously. Interviews took about 45 to 60 min, and were conducted in face-to-face settings. Six designers were interviewed individually while two interviews were held with two designers who work closely together. The interviews were recorded and later transcribed.

Each interview consisted of three parts. The first part was meant to get acquainted with the interviewees and their design practice. Interviewees were asked about their ways of working when designing information visualizations for a general audience. In the second part, they were asked the main questions regarding clarity, objectivity, and attractiveness. Questions were framed in a general way so as to grant interviewees the opportunity to mention other elements than anticipated. In the third part, interviewees were asked if they ever conducted usability tests, if they checked data, what they thought about misleading graphs, and what design literature they consulted. Finally some typical examples from the designer’s portfolio were examined to further illustrate their ideas. The full list of questions appears in Appendix A.

Handbooks: 26 information design handbooks were reviewed. The full list of references is in Appendix B.

Selection: The selection of handbooks was based on at least one of the following three criteria. First, general information design handbooks were selected which are recommended by the International Institute for Information Design (www.iiid.net). From this source we selected all handbooks which focus on information design (n = 8) (and not for example on architecture or urban design). Second, we selected all design handbooks that the interviewees had reported to consult regularly (n = 12). Third, we selected the 15 information design and data visualization books that, according to library loan statistics, are most frequently consulted by design students at AKV|St.Joost academy of art and design, Avans University (the first author’s affiliation). In sum, this search resulted in 26 design books that were reviewed (see Appendix C for full references).

Review procedure: the indexes and tables of content were inspected for relevant terms (aesthetics, attractiveness, clarity, principles, and related criteria terms). If they were found, the referenced sections were reviewed. Because explicit references to the terms as mentioned were hardly ever found in the indexes and tables of content, we also consulted the introductory sections and chapters of the handbooks. In those cases where a handbook was divided into parts that contained separate introductions, we reviewed the introductions of each part.

2.2. Analyses

Transcriptions and selected excerpts from handbooks were analyzed in three steps. First, we selected all statements that somehow appeared to include an answer to one of the three questions or expressed an opinion with regard to these questions. This way the materials were made manageable in terms of size and focus. Next, we presented statements concerning the first two questions, i.e., clarity and objectivity, in a forced choice task to respondents, so as to collect intersubjective validation of the designers’ position on these two questions. Finally, we conducted an additional qualitative analysis of the fragments, including those addressing the third question concerning attractiveness, thereby taking into account the data collected in the previous steps.

2.2.1. Step 1: Selecting Relevant Statements

Interviews

The interviews yielded 25 statements and excerpts that explicitly addressed the itemized issues: 9 on the importance of clarity and attractiveness, 9 about objectivity vs. subjectivity, and 7 about features contributing to attractiveness.

Handbooks

From the 26 selected handbooks, statements were taken that contained explicitly marked normative expressions with regard to the criteria and objectives of information visualization design. These statements typically contain modal verbs such as ‘must’ or ‘should’ in relation to information design, e.g., “Information displays should be […]”, or normative markers such as ‘the first priority of an information designer is […]’; ‘principles of analytic design: […]’; ‘the purpose of visualization is […]’, or ‘excellence consists of […]’. This selection resulted in 28 normative statements coming from 22 handbooks (4 handbooks contained no normative statements regarding criteria and objectives). Of these statements, 19 addressed the clarity question, 7 the objectivity question, and 2 the attractiveness question.

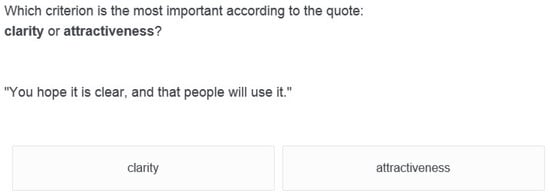

2.2.2. Step 2: Explorative Survey

Before the statements from the interviews and design handbooks were analyzed, a separate survey was conducted in order to obtain an intersubjective agreement on the interpretation of the 44 clarity and objectivity statements. The statements were presented to an independent group of 39 participants in a forced choice task survey. For each statement, these independent participants were asked to judge the position of the statement’s author on a dichotomous scale (clarity or attractiveness, subjectivity or objectivity. Figure 1 shows an example of a clarity statement as it was presented in the survey.

Figure 1.

Example of statement and scale from the interpretation survey.

The survey was constructed in Qualtrics and distributed via email to teachers of various disciplines and master of design students of Avans University. The survey was taken by 39 respondents (22 designers, 17 design lays), all with higher vocational- or university-level education. Table 1 shows the results from the survey (see Appendix B for all statements and scores per statement). A statement was considered to represent a certain position on the scale (e.g., either clarity or attractiveness), when at least two-third of the respondents selected this position (66.66% or more). Otherwise, the statement was considered undecided.

Table 1.

Number of statements in which each criterion is judged as most important.

The results show that in the majority of the ‘clarity’ statements from the interviews and the handbooks clarity is considered to be the most important criterion (20/28). Moreover, there is broad agreement on this choice, as is shown in Appendix C, listing the percentages of the respondents choosing clarity as main criterion. In 16 of the 20 cases, more than 80% of the respondents agreed on this interpretation of clarity being the main criterion.

As for the objectivity–subjectivity statements, results are undecided for half of the statements (8/16). In 6 of the remaining 8 cases the statements are interpreted as objectivity being the main communicative goal. Only a small minority of statements (2/16) is interpreted as subjectivity being the main goal.

2.2.3. Qualitative Analysis

In this section we answer the three research questions by analyzing the answers and fragments addressing them. To exemplify analyses, several statements will be provided with relevant passages put in italics and each of them accompanied by the source (I = interviews; H = handbooks) and the percentage of respondents in the survey (as given in Appendix C) which agreed on its interpretation.

Clarity vs. attractiveness

With respect to the main criteria for good information visualizations for a general audience, handbooks and interviews offer a consistent picture: clarity and attractiveness are considered by far the most important criteria. Of these two, clarity is considered the most important criterion, both in the interviews and in the handbooks. In interview statements, it is often mentioned first, given more emphasis, and often more elaborated upon, as is testified by (1).

- (1)

- “Relevance. […] Meaning the infographic has to contribute to conveying information. It must be clear. That means you have to make choices with which you guide your reader through the infographic. Accessibility. The reader must not give up because of complexity or because he doesn’t know where to begin. And attractiveness. [,…] It must surprise, excite, make curious.” (I; clarity: 96.4 %)

Also, when attractiveness is mentioned as being important, statements to this effect are immediately moderated by a ‘but‘ or ‘however’ phrase stating that clarity is more important. See the following statements:

- (2)

- “I think you must be able to see what the subject is. Quickly see where you have to search. Not simplify by leaving out, but clarify by layering. Attractiveness tops. But I am not an artist. Form follows content. If the image is pretty but non-informative, than that is not sufficient for me. Not more image than content.” (I; clarity: 100%)

- (3)

- “The purpose of visualization is insight, not pictures. A visualization’s function is to facilitate understanding. Form has to follow this function. This does not mean that aesthetics are not important—they are. […] However, it is not only aesthetics that help to increase the information flow.” (H: Scheiderman, in Klanten 2010, p. 8; clarity: 82.1%)

In other cases, the priority is obvious, since the statements only mention efficiency or clarity (e.g., 4):

- (4)

- “Information design as a discipline has the efficient communication of information as its primary task.” (H: Wildbur and Burke 1998, p. 6; clarity: 96.4%)

In only 3 of the statements (all from the interviews) attractiveness is considered most important, as in statement (5).

- (5)

- “Clarity and aesthetics. Where the emphasis is put, depends on the target group and the assignment. If it is for a newspaper for a broad non-expert audience, you have to tell a story that is engaging; then it is not all about efficiency.” (I; clarity: 21.4%)

In some statements, attractiveness and clarity are mentioned as equally important, which results in the interpretations being undecided, as in the following cases:

- (6)

- “The only conclusion possible is that design always involves three inextricably related elements, however much their relative proportions may differ from one application to the next, namely: durability, usefulness, and beauty.” (H: Mijksenaar 1997, p. 18; clarity: 46.4%)

- (7)

- “The optimum synthesis of aesthetics and information value remains the essential objective in every type of diagrammatic presentation.” (H: Herdeg 1981, p. 6; clarity: 64.4%)

Several interviewees and design handbooks also stress that striving for clarity does not mean that information should be simplified by leaving things out. Instead, complex information should be made accessible and understandable by design means such as layering: a visual ordering of information that allows both overview and detailed reading, and that highlights what is important (e.g., Few 2004; Tufte 1990).

Despite the value they assign to clarity, most of the interviewees indicate in their answers to the additional question in this regard, that they hardly ever test if their audience understands their designs. If they test their designs before publication at all, this is usually done informally among fellow designers.

Objectivity vs. subjectivity

The second main question was if designers aim to communicate objective or subjective information. The dichotomy objective vs. subjective suggests a sharp contrast between the two, but the answers and fragments addressing this issue show a more nuanced picture. In the statements, subjectivity does not mean that readers are forced to swallow the designer’s truth or opinions. Rather, it covers the idea that most of the designers aim to do more than just present data. They feel they need to add elements enabling viewers to arrive at an adequate or intended interpretation of the data. More than in the previous questions, the interpretation of the statements in this section is undecided (8/16). See for example the following statements:

- (8)

- “Complete objectivity doesn’t exist, you always make choices. But it is not our aim to give our personal opinion.” (I; objectivity: 60.7%)

- (9)

- “I do not give my own judgment. You have to interpret. But people have to make their own judgment.” (I; objectivity: 57.1%)

- (10)

- “You have to interpret; simply providing data is pointless. But people have to make their own judgment.” (I; objectivity: 28.6%)

Complete objectivity would mean presenting raw data, which is something designers feel is of no use for non-expert users. For these audiences in particular, the designer needs to choose which data are relevant and which patterns and relationships to show in order to convey the intended message. Furthermore, the designer needs to choose design elements that help to explain what the visualization shows, such as labels, pointers, line width and colors that direct the eyes to what is important (Yau 2011). ‘Making choices’ in (8) and ‘interpret’ in (9) and (10), therefore, most likely refer to this kind of decisions and choices. Apparently, survey respondents had difficulty to decide if these statements should be interpreted as intending to be objective (no opinions, no judgments) or subjective (interpret). While these statements seem to have similar meaning (“interpretation, but no judgment”), the interpretation of (8) and (9) is rather undecided (60.7% and 57.1% objectivity respectively), whereas (10) is interpreted as subjective (28.6% objectivity). It may be the case that the difference between undecided and subjective results from the way the word ‘interpret’ is embedded in the sentences. In (8) and (9) subjectivity (‘you always make choices’ and ‘give my own judgment’) is construed as inevitable but explicitly denied to be the aim of designs, or it is first denied, followed by the need to interpret (9; ‘subjectivity’). In statement (10) on the other hand the need to interpret is mentioned first. Besides these undecided cases, 6 of the 16 statements were interpreted as objectivity, as in (11):

- (11)

- “Show the data; […] avoid distorting what the data have to say.” (H: Tufte 2001, p. 13; objectivity: 92.9%)

Only 2 of the 16 statements were interpreted as subjectivity being the main goal. An example is (12) In which the terms ‘engage’, ‘feeling’, and ‘atmosphere’ are mentioned and apparently associated with subjectivity.

- (12)

- “Then you must be able to experience the story. Make the story manifest. Engage people. [The question is:] how to translate a feeling, an atmosphere, into something visual?” (I; objectivity: 10.7%)

Apart from the question what subjectivity means exactly (ranging from allowing readers their own interpretation of the data to conveying personal opinions on the part of the designer), an interesting other question is whose interpretation is expressed in the designs. For example in (13), it is suggested that it is not the designer’s personal opinion that counts, but his clients’ messages:

- (13)

- “I try to make things visual as soon as possible, and then discuss with the client what exactly it is they want to tell. It is not about my own message.” (I; objectivity: 64.3%)

This response raises two issues: the source and correctness of the data, and the relationship between what the data have to say and the message that the client wishes to convey. From the answers to the additional questions in the interviews, it becomes apparent that designers are well aware of these issues, and of their responsibility in the way information is interpreted and visualized. As for the source and correctness of the data, in many cases the data are supplied by the client (business, government, or editorial), but in 4 of the interviewees’ practices it regularly occurs (mostly in journalism) that the designers collect the data themselves. In all those cases, designers emphasize that they assign much value to correctness of the data. If they have access to the sources, they check them, and if they come across mistakes, omissions or inconsistencies, they contact the client and correct them. When it comes to the interpretation of the data, there are roughly two scenarios. In 6 of the interviewees’ design practices, the situation occurs that the client has no clear message to convey. In particular, governmental and business clients sometimes supply data, but leave it to the designer to interpret them. In these cases the designer discusses with the client what s/he believes to be the most important information and what s/he thinks the message is that the client might want to convey. See for example the following statement:

- (14)

- “Sometimes the message is clear, but not always. These days I am increasingly employed by businesses, and then the assignment is often very vague. I take an active role then to find out: what is the message? They often don’t know. (…) Or governments have made analyses and want to show something about them to managers or to the public. Then they come to us with piles of reports full of important information: can you make a graphic of this? (…) Then we have to extract the essence ourselves.”

In the other scenario, also mentioned as occurring regularly in half of the interviewees’ design practices, the client has a clear conception of the message s/he wants to transmit. In these cases the designers all state that this message has to be in accordance with the data provided. None of them are prepared to ‘lie’ or deceive with information visualizations by manipulating data, distorting scales or whatever means, and clients, they say, hardly ever ask them to do so purposefully. See for example statement 15:

- (15)

- “It only happened once, with a big international non-profit organization (…). When the data did not fit the story, they would just make another selection from the data. I will never work for them again.”

In another example the designer was asked not so much to ‘lie’, but to upscale an organization’s role in a decision process as being central, while in reality, to go by the data, their role was only marginal. The designer’s reaction:

- (16)

- “When something is not right in a graphic, people notice that quicker than in a text. (…) You cannot visualize what is not there. [Referring to the example:] We reached a compromise: the organization on top instead of at the bottom, the process reversed. If I had given them what they wanted and had put them literally in the center, it would have become a very bad visualization with a weird twist in it, and people notice that.”

In this designer’s opinion, it is hard to deceive viewers with visualizations. Many researchers and designers would disagree with this, such as Tufte (1983), who showed excellent examples of how to ‘lie’ with graphs in ways that are still ubiquitous. We will not further elaborate on this matter in the framework of this study, but it is an interesting research question to what extent people are visually literate enough nowadays to not let themselves be tricked by distorted or manipulated data visualizations.

In the case of newspapers-as-clients, designers sometimes find themselves in a position where editors reject a graphic if it does not fit the story they intend to tell. Also, then, the designers report they refuse to create a graphic that does not fit the data.

Attractiveness features

We also searched in the handbooks and interviews for fragments that offer information on what determines or characterizes attractiveness. The results illustrate how difficult it is to put into words what makes a design—or any artifact—attractive. See for example the following statements from the interviews:

- (17)

- “That is in the design. I think in metaphors, which I try to use as an illustrative element. […] I use associations between subject and form […]. It is mainly about information density.”

- (18)

- “That follows from the process. It designs itself. Beauty that you see in it is a bit of intuition that you are doing alright. I don’t think we have a visual language of our own.”

- (19)

- “We start from what we consider good ourselves. That is hard to define. Data visualization is usually clear in terms of archetype. Then look at contrast, define archetype, and then the subject, and then you come in an atmosphere, and aesthetics. Aesthetics is important. We do what we like.”

None of the interviewees suggests that attractiveness might be found in familiarity, as is assumed in several theories (Zajonc 1968, 1984; Reber et al. 2004). Some, however, refer to notions such as novelty (something unique, or surprising), as in the following examples:

- (20)

- “In interactive visualizations: playful movement, something surprising… Use of color… More feeling. Just as much information, but beautifully designed.”

- (21)

- “(…) something that is unique and tells a story, that attracts attention and is remembered.”

In the design handbooks, explicit statements concerning features that might define attractiveness turn out to be hard to find, despite the importance that is attached to attractiveness. Two statements seem to attempt to define what makes an information visualization attractive:

- (22)

- “Graphical elegance is often found in simplicity of design and complexity of data.” (Tufte 2001, p. 177)

- (23)

- “Elegance is a measure of the grace and simplicity of the designed product relative to the complexity of its functions.” (Herdeg 1981, p. 8)

These statements are in accordance with theories describing attractiveness in terms of a balance between extremes, in this case between simplicity and complexity. Furthermore, this idea that people would be attracted to ‘simplicity in complexity’ resembles an assumption in simplicity theory stating that people find it pleasing when seemingly difficult information is surprisingly easy to understand (Chater 1999). This suggests that attractive information design results not from simplifying things, but from clarifying complex information, as is also reflected in one statement from the interviews concerning the importance of clarity:

- (24)

- “(…) Not simplify by leaving out, but clarify by layering. (…)”

and in one interviewee’s response to the question concerning features of attractiveness:

- (25)

- “(…) many data that show patterns. (…)”

In sum, novelty and simplicity in complexity seem to play a role in attractiveness, but taken together, the statements from the interviews and the design handbooks offer too little explicit information to draw conclusions about what designers consider features determining attractiveness of information visualizations.

3. Discussion and Conclusions

According to designers, data visualizations for non-expert audiences should be attractive and, most importantly, clear. Contrary to what is sometimes conjectured by scientists, designers do not put more emphasis on appearance than on understandability. On the contrary, attractiveness is considered important, but clarity is paramount. Interestingly, despite the importance they assign to clarity, the designers indicate in the interviews that they hardly ever test their designs among the intended audiences. If they test them at all, they usually do this among fellow designers. Therefore, it would be interesting to test if popular data visualizations are indeed understood by a general audience of non-designers.

Furthermore, it becomes apparent from the design handbooks and especially the interviews that designers act very responsibly in the way they visualize information. They attach much importance to correctness of data, and they are careful not to deceive their audience. Messages conveyed through visualizations should fit the data. They feel no need to convey personal opinions or judgment, but they do feel that they need to help their readers to interpret visualizations.

Concerning attractiveness, it is striking how little information can be found about what might contribute to the attractiveness of visualizations. Hardly any information can be found on this matter in design handbooks, and designers find it hard to describe what features might make their designs attractive. This is not surprising, of course. Also in other disciplines, such as literature, it will be hard to find a discourse that explains what makes a text or some other artifact attractive, and it will be equally hard for other practitioners to put into words what makes their works appealing. Designers mention features such as novelty, which might be expected, considering that it is a designer’s job to create new things. This is also shown in studies investigating differences between designers and laymen in design in the ways they appreciate and understand visual information. Laymen find familiar visualizations attractive, whereas designers consider novel types of visualizations attractive (Quispel et al. 2016).

In all, the fragments and statements about aesthetic factors are too few in number to base conclusions on. Yet, designers and both scientific and design literature agree that aesthetics play an important role in information visualization, equally important to understandability, and research has shown interactions between aesthetics and (perceived) usability. It would, therefore, be an interesting direction for future research to further investigate the characteristics of aesthetics in information visualization, and its relationships with usability. Furthermore, the scarce handbook fragments and interview statements which we did find support existing theories about simplicity in complexity (or unity in variety) as an aesthetic factor, which certainly deserves further empirical research.

Author Contributions

This article was written by A.Q. as part of her PhD research into visual communication, supervised by co-authors A.M. and J.S.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Interview questions:

Introductory questions:

- Can you briefly describe your educational background and professional career/experience?

- What kind of clients do you usually work for and prefer to work for? (e.g., editorial, government, business)

- Can you describe a typical work process? How are you provided with the data, who is responsible for the analysis, who constructs the message, and how do you communicate with the client about the design?

Main questions:

- What are the main criteria for a good data visualization for a general audience?

- What makes a data visualization attractive?

- Do you show opinions in your data visualization designs?

Additional questions:

- What is your opinion about misleading with graphs? Do clients ever ask you to lie with graphs, and have you ever done that? Do you check the data you are supplied with?

- Do you test your designs before they get published?

- Do you consult design handbooks, and if so, which?

Appendix B

Reviewed design handbooks:

- LL = library loan

- IW = interviewees’ literature

- IIID = recommended by IIID

Bertin, J. (2011). Semiology of Graphics: diagrams, networks, maps. Redlands, CA: ESRI. [IW]

Brückner, H. (2004). Informationen Gestalten. Bremen: Hauschild. [LL; IIID]

Cairo, A. (2013). The functional art: an introduction to information graphics and visualization. Berkeley, CA: New Riders. [IW]

Few, S. (2004). Show me the numbers: designing tables and graphs to enlighten. Oakland, CA: Analytics Press. [IW]

Harris, R. (1999). Information graphics: a comprehensive illustrated reference. Atlanta, GA: Management Graphics. [IW]

Herdeg, W. (ed.) (1981). Diagrams: the graphic visualization of abstract data. Zürich: Graphis Press. [LL]

Holmes, N. (2005). Wordless Diagrams. New York: Bloomsbury. [LL]

IIID Japan (ed.) (2005). Information Design Source Book. Basel: Birkhauser-Publishers for Architecture. [IIID]

Jacobson, R.E. (ed.) (1999). Information design. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [IIID]

Klanten, R. (ed.) (2008). Data Flow—Visualising Information in Graphic Design. Berlin: Gestalten. [LL]

Klanten, R. (ed.) (2010). Data Flow 2: visualizing information in graphic design. Berlin: Gestalten. [LL; IW]

Klanten, R. (ed.) (2011) Visual Storytelling: inspiring a new visual language. Berlin: Gestalten. [LL]

Lima, M. (2011). Visual complexity: Mapping patterns of information. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. [LL]

Maeda, J. (1999). Design by numbers. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [IW]

McCandless, D. (2009). Information is beautiful. London: Collins. [LL; IW]

Mijksenaar, P. (1997). Visual Function: an introduction to Information Design. Rotterdam: 1010 Publishers. [IIID; IW]

Neurath, O. (2010). From hieroglyphics to Isotype: a visual autobiography. London: Hyphen. [IW]

Tufte, E. R. (1990). Envisioning Information. Cheshire, Connecticut: Graphics Press. [LL; IIID]

Tufte, E. R. (1997). Visual Explanations. Cheshire, Connecticut: Graphics Press. [LL; IIID]

Tufte, E. R. (2001). The Visual Display of Quantitive Information. Cheshire, Connecticut: Graphics Press. [LL; IIID; IW]

Tufte, E.R. (2006). Beautiful Evidence. Cheshire, Connecticut: Graphics Press. [LL]

Ware, C. (2004). Information Visualization—Perception for Design. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann. [IW]

Ware, C. (2008). Visual Thinking for Design. Amsterdam: Elsevier/Morgan Kaufmann. [IW]

Wildbur, P. (1989). Information Graphics. Houten: Gaade. [LL]

Wildbur, P. & Burke, M. (1998). Information Graphics—Innovative Solutions in Contemporary Design. London: Thames and Hudson. [LL; IIID]

Woolman, M. (2002). Digital Information Graphics. London: Thames & Hudson. [LL]

Appendix C. Statements and Their Scores (Percentages of Choices for Clarity and Objectivity)

- I = statement from interview

- H = statement from design handbook

| Statements on clarity vs. attractiveness | ||

| Statements judged to express clarity as main criterion (>66.66%) | % clarity | |

| I | “I think you must be able to see what the subject is. Quickly see where you have to search. Not simplify by leaving out, but clarify by layering. Attractiveness tops. But I am not an artist. Form follows content. If the image is pretty but non-informative, then that is not sufficient for me. Not more image than content.” | 100.0 |

| H | “To communicate quantitative information effectively first requires an understanding of the numbers, then the ability to display their message for accurate and efficient interpretation by the reader.” (Few 2004, p. 10) | 100.0 |

| H | “Our goal is to enable the user to understand and find his way […]. Accuracy always takes priority over esthetics.” (Brückner 2004, p. 11) | 100.0 |

| I | “Relevance. […] Meaning the infographic has to contribute to conveying information. It must be clear. That means you have to make choices with which you guide the reader through the infographic. Accessibility. The reader must not give up because of complexity or because he doesn’t know where to begin. And attractiveness. […] It must surprise, excite, make curious.” | 96.4 |

| I | “It must be legible. And the reader must be able to read his own story: can you compare things, zoom in on details, etc. You often see beautiful images with a lot of data without the story being clear. That is not good.” | 96.4 |

| H | “A graphic designer is expected to convey a message as clear as possible by creating order in text and image. Information design is a spectrum of design that is mainly occupied with giving consumers information in the clearest and most direct manner.” (Wildbur 1989, inside cover) | 96.4 |

| H | “The challenge is to develop ways of arranging the most relevant data in the clearest manner and the smallest amount of space.” (Woolman 2002, p. 11) | 96.4 |

| H | “Information design as a discipline has the efficient communication of information as its primary task.” (Wildbur and Burke 1998, p. 6) | 96.4 |

| H | “Excellence in statistical graphics consists of complex ideas communicated with clarity, precision, and efficiency.” (Tufte 2001, p. 13) | 92.9 |

| H | “Its [information design] purpose is the systematic arrangement and use of communication carriers, channels, and tokens to increase the understanding of those participating in a specific conversation or discourse.” (Jacobson 1999, p. 4) | 89.3 |

| I | “You hope it is clear, and that people will use it.” | 85.7 |

| H | “The first goal of an infographic is not to be beautiful just for the sake of eye appeal, but, above all, to be understandable first, and beautiful after that, or to be beautiful thanks to its exquisite functionality. A good graphic realizes two basic goals: it presents information, and it allows users to explore that information.” (Cairo 2013, p. xx) | 85.7 |

| H | “Although aesthetics are taking on an increasingly important role, we must always ensure that visualizations make things easier to understand.” (Richli in Klanten 2008, p. 185) | 85.7 |

| H | “The goal of information design must be to design displays so that visual queries are processed both rapidly and correctly for every important cognitive task the display is intended to support.” (Ware 2008, p. 14) | 85.7 |

| H | “The purpose of visualization is insight, not pictures. A visualization’s function is to facilitate understanding. Form has to follow this function. This does not mean that aesthetics are not important—they are. […] However, it is not only aesthetics that help to increase the information flow. Narrative is a very powerful tool as well.” (Schneidermann in Klanten 2010, p. 8) | 82.1 |

| H | “The idea is to make designs that enhance the richness, complexity, resolution, dimensionality, and clarity of the content.” (Tufte 1997, pp. 9–10) | 82.1 |

| I | “It must tell a story. Provide insight into something. No info no graphic. Aesthetics is also important, if it does not distract.” | 75.0 |

| I | “The data set is important. It must tell something, provide a different insight than with Excel. It starts with the analysis of what you could give insight in.” | 71.4 |

| H | “Certain [design] choices become compelling because of their greater efficiency.” (Bertin 2011, p. 9) | 71.4 |

| H | “It is an essential element […] that the design of symbols in themselves, as well as their arrangement, should be attractive. Yet, line, color and shade are not to be employed merely for the pleasure we take in them, but for informative purposes.” (Neurath 2010, p. 106) | 67.9 |

| Statements undecided (66.66–33.33%) | % clarity | |

| H | “When consistent with the substance and in harmony with the content, information displays should be documentary, comparative, causal and explanatory, quantified, multivariate, exploratory, skeptical.” (Tufte 1997, p. 53) | 64.3 |

| H | “The optimum synthesis of aesthetics and information value remains the essential objective in every type of diagrammatic presentation.” (Herdeg 1981, p. 6) | 64.3 |

| H | “Too many data presentations, alas, seek to attract and divert attention by means of display apparatus and ornament.” (Tufte 1990, p. 33) | 60.7 |

| H | “The only conclusion possible is that design always involves three inextricably related elements, however much their relative proportions may differ from one application to the next, namely: durability, usefulness, and beauty.” (Mijksenaar 1997, p. 18) | 46.4 |

| H | “Combining beauty and truth, they [data visualizations] are, at their best, inspiring, fascinating, visually interesting and easy to read, while conveying complex levels of information in an impactful way.” (Losowsky in Klanten 2011, p. 6) | 39.3 |

| Statements judged to express dominance of attractiveness as main criterion (<33.33%) | % clarity | |

| I | “It starts with the data. A design cannot transcend the content. […] Then you must be able to experience the story. Make the story manifest. Engage people. It must contain something intriguing that attracts.” | 25.0 |

| I | “Clarity and aesthetics. Where the emphasis is put, depends on the target group and the assignment. If it is for a newspaper for a broad non-expert audience, you have to tell a story that is engaging; then it is not all about efficiency.” | 21.4 |

| I | “Data must be correct, fit the story, and it must provide an extra or different insight into the story that accompanies it. You don’t have to be able to see immediately what it is about—that is too difficult with some financial constructions. But I do try to make something stand out, as a sort of hook.” | 10.7 |

| Statements on objectivity vs. subjectivity | ||

| Statements judged to express dominance of objectivity as main goal (>66.66%) | % objectivity | |

| H | “Show the data; […] avoid distorting what the data have to say.” (Tufte 2001, p. 13) | 92.9 |

| H | “The first priority of information design is the correct communication of serious subject matter.” (Brückner 2004, p. 7) | 89.3 |

| H | “A good graphic realizes two basic goals: it presents information, and it allows users to explore that information.” (Cairo 2013, p. 73) | 85.7 |

| H | “Show comparisons, contrasts, differences. Show causality, mechanism, explanation, systematic structure.” (Tufte 2006, p. 127) | 75.0 |

| I | “I think the essence is that you confine yourself to facts and figures and let the reader draw his own conclusions. I don’t feel the need to give my own viewpoints, I rather do it the other way around.” | 71.4 |

| I | “We don’t need to bring our own truth, we rather map everything, so that people can form their own opinion.” | 67.9 |

| Statements undecided (66.66–33.33%) | ||

| I | “I try to make things visual as soon as possible, and then discuss with the client what exactly it is they want to tell. It is not about my own message.” | 64.3 |

| H | “Evidence presentations [=data visualizations] should be created in accord with the common analytical tasks at hand, which usually involve understanding causality, making multivariate comparisons, examining relevant evidence, and assessing the credibility of evidence and conclusions.” (Tufte 2006, p. 9) | 64.3 |

| I | “Complete objectivity doesn’t exist, you always make choices. But it is not our aim to give our personal opinion.” | 60.7 |

| H | “Contemporary information designers seek to edify more than persuade, to exchange ideas rather than foist them on us.” (Jacobson 1999, pp. 1–2) | 60.7 |

| I | “I do not give my own judgment. You have to interpret. But people have to make their own judgment.” | 57.1 |

| I | “I need to agree with the message and the visualization. But I do not show political messages.” | 46.4 |

| I | “Telling the story is the starting point. You make something with a goal. In the visualization you have to help people in the interpretation. Not simply show something. But I do not judge.” | 42.9 |

| H | “A successful visualization […]: it informs, it makes the reader think about the world around them, and about our own lives. It stirs emotions, it encourages action, it equips us, it inspires us.” (Losowsky in Klanten 2011, p. 7) | 39.3 |

| Statements judged to express dominance of subjectivity as main goal (<33.33%) | % objectivity | |

| I | “You have to interpret; simply provide data is pointless. But people have to make their own judgment.” | 28.6 |

| I | “Then you must be able to experience the story. Make the story manifest. Engage people. [The question is:] how to translate a feeling, an atmosphere, into something visual?” | 10.7 |

| Statements on the characteristics of attractiveness | ||

| I | “In interactive visualizations: playful movement, something surprising… Use of color… More feeling. Just as much information, but beautifully designed.” | |

| I | “Quantity matters; many data that show patterns. And then find a good form. You must be able to see information, but also an interesting form. […]. But something that is unique and tells a story, that attracts attention and is remembered.” | |

| I | “For me that is in quiet, balance between text and image, about 80/20. It must contain air. It must surprise, tickle, make curious. […] The main image must make curious. There is information everywhere, so it must have a hook in the image to which the eye lingers. […] Quiet ordering, hierarchy in typography. Colors in a limited palette, so that you can put accents for attention.” | |

| I | “Exciting design, whatever that is, surprising forms.” | |

| I | “That is in the design. I think in metaphors, which I try to use as an illustrative element. […] I use associations between subject and form […]. It is mainly about information density.” | |

| I | “That follows from the process. It designs itself. Beauty that you see in it is a bit of intuition that you are doing alright. I don’t think we have a visual language of our own.” | |

| I | “We start from what we consider good ourselves. That is hard to define. Data visualization is usually clear in terms of archetype. Then look at contrast, define archetype, and then the subject, and then you come in an atmosphere, and aesthetics. Aesthetics is important. We do what we like. Newspapers have guidelines, of course. Within those we search for freedom. We try to use limited colors. And silhouette: […] try to lift the form out of the page. […].” | |

| H | “Graphical elegance is often found in simplicity of design and complexity of data.” (Tufte 2001, p. 177) | |

| H | “Elegance is a measure of the grace and simplicity of the designed product relative to the complexity of its functions.” (Herdeg 1981, p. 8) |

References

- Berlyne, Daniel E. 1971. Aesthetics and Psychobiology. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. [Google Scholar]

- Bertin, Jacques. 2011. Semiology of Graphics: Diagrams, Networks, Maps. Redlands: ESRI. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1987. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. First published 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Brückner, Hartmut. 2004. Informationen Gestalten. Bremen: Hauschild. [Google Scholar]

- Cairo, Alberto. 2013. The Functional Art: An Introduction to Information Graphics and Visualization. Berkeley: New Riders. [Google Scholar]

- Card, Stuart K., Jock MacKinlay, and Ben Shneiderman, eds. 1999. Readings in Information Visualization: Using Vision to Think. Burlington: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Cawthon, Nick, and Andrew Vande Moere. 2007. The Effect of Aesthetic on the Usability of Data Visualization. Paper presented at 11th International Conference Information Visualization (IV’07), Zürich, Switzerland, July 4–6; pp. 631–36. [Google Scholar]

- Chater, Nick. 1999. The search for simplicity: A fundamental cognitive principle? The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 52A: 273–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, Nigel. 1982. Designerly Ways of Knowing. Design Studies 3: 221–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrikant, Sara Irina, Sidonie Christophe, Georgios Papastefanou, and Sara Maggi. 2012. Emotional response to map design aesthetics. Paper presented at GIScience Conference 2012, Columbus, OH, USA, September 18–21; Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Few, Stephen. 2004. Show Me the Numbers: Designing Tables and Graphs to Enlighten. Oakland: Analytics Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gaver, William W., Jacob Beaver, and Steve Benford. 2003. Ambiguity as a resource for design. In Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI). Ft. Lauderdale: ACM Press, pp. 233–40. [Google Scholar]

- Gombrich, Ernst H. 1995. The Story of Art. London: Phaidon. [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty, Mary. 2011. The Cognitive Science of Visual-Spatial Displays: Implications for Design. Topics in Cognitive Science 3: 446–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hekkert, Paul. 2006. Design aesthetics: Principles of pleasure in design. Psychological Science 48: 157–72. [Google Scholar]

- Herdeg, Walter, ed. 1981. Diagrams: The Graphic Visualization of Abstract Data. Zürich: Graphis Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, Robert E., ed. 1999. Information Design. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Judelman, Greg. 2004. Aesthetics and Inspiration for Visualization Design: Bridging the Gap between Art and Science. Paper presented at Eighth International Conference on Information Visualisation (IV’04), London, UK, July 14–16; pp. 245–50. [Google Scholar]

- Klanten, Robert, ed. 2008. Data Flow—Visualising Information in Graphic Design. Berlin: Gestalten. [Google Scholar]

- Klanten, Robert, ed. 2010. Data Flow 2: Visualizing Information in Graphic Design. Berlin: Gestalten. [Google Scholar]

- Klanten, Robert, ed. 2011. Visual Storytelling: Inspiring a New Visual Language. Berlin: Gestalten. [Google Scholar]

- Kosara, Robert. 2007. Visualization Criticism—The Missing Link Between Information Visualization and Art. Paper presented at 11th International Conference on Information Visualisation (IV’07), Zürich, Switzerland, July 4–6; pp. 631–36. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, Andrea, and Andrew Vande Moere. 2007. Towards a Model of Information Aesthetic Visualization. Paper presented at 11th International Conference on Information Visualization (IV’07), Zürich, Switzerland, July 4–6; pp. 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Lavie, Talia, and Noam Tractinsky. 2004. Assessing dimensions of perceived visual aesthetics of Web sites. International Journal of Human Computer Studies 60: 269–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, Ellen, Jeff Zacks, Barbara Tversky, and Diane Schiano. 1996. Gratuitous graphics? Putting Preferences in Perspective. Paper presented at SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI’96), Vancouver, BC, Canada, April 13–18; pp. 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- McCandless, David. 2009. Information Is Beautiful. London: Collins. [Google Scholar]

- McWhinnie, Harold J. 1968. A review of research on aesthetic measure. Acta Psychologica 28: 363–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijksenaar, Paul. 1997. Visual Function: An Introduction to Information Design. Rotterdam: 1010 Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Neurath, Otto. 2010. From Hieroglyphics to Isotype: A Visual Autobiography. London: Hyphen. [Google Scholar]

- Ngo, David, Lian Teo, and John Byrne. 2003. Modelling interface aesthetics. Information Science 152: 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quispel, Annemarie, Alfons Maes, and Joost Schilperoord. 2016. Graph and chart aesthetics for experts and laymen in design: The role of familiarity and perceived ease of use. Information Visualization 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reber, Rolf, Norbert Schwartz, and Piotr Winkielman. 2004. Processing Fluency and Aesthetic Pleasure: Is Beauty in the Perceiver’s Processing Experience? Personality and Social Psychological Review 8: 364–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schön, Donald A. 1983. The Reflective Practitioner. How Professionals Think in Action. London: Templer-Smith. [Google Scholar]

- Storkerson, Peter K. 2006. Communication Research: Theory, Empirical Studies, and Results. In Design Studies—Theory and Research in Graphic Design. Edited by Audrey Bennet. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tufte, Edward R. 1983. The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. Cheshire: Graphics Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tufte, Edward R. 1990. Envisioning Information. Cheshire: Graphics Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tufte, Edward R. 1997. Visual Explanations. Cheshire: Graphics Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tufte, Edward R. 2001. The Visual Display of Quantitive Information. Cheshire: Graphics Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tufte, Edward R. 2006. Beautiful Evidence. Cheshire: Graphics Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vande Moere, Andrew, and Helen Purchase. 2011. On the role of design in information visualization. Information Visualization 10: 356–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, Colin. 2008. Visual Thinking for Design. Amsterdam: Elsevier/Morgan Kaufmann. [Google Scholar]

- Wildbur, Peter. 1989. Information Graphics. Houten: Gaade. [Google Scholar]

- Wildbur, Peter, and Michael Burke. 1998. Information Graphics—Innovative Solutions in Contemporary Design. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Woolman, Matt. 2002. Digital Information Graphics. London: Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Yau, Nathan. 2011. Visualize This. The Flowing Data Guide to Design, Visualization, and Statistics. Indianapolis: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Zajonc, Robert B. 1968. Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology Monograph Supplements 9 Pt 2: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajonc, Robert B. 1984. On the primacy of affect. American Journal of Psychology 39: 117–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | In the scientific field of information visualization, the term information visualization refers to the computer-aided interactive visualization of big data with the aim of amplifying cognition (Card et al. 1999). In graphic design, the term refers to a broader category of visualizations meant to inform or instruct people, including data visualization. In this article, the term information visualization refers to the visualization of quantitative data, be it limited or big, static or interactive. |

| 2 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).