Abstract

A work of Vietnamese art crossed the million-dollar mark in the international art market in early 2017. The event was reluctantly seen as a sign of maturity for Vietnamese art amidst many problems. Even though the media in Vietnam has discussed the problems enthusiastically, there is a lack of literature from Vietnamese academics on the subject, especially from the market perspective. This paper aims to contribute an insightful perspective on the Vietnamese art market through the lens of art frauds. Thirty-five cases of fraudulent paintings were found on the news and in stories told by art connoisseurs. The qualitative analysis of the cases has shown that the economic value of Vietnamese paintings remains high despite the controversial claims about their authenticity. Here, the Vietnamese authority seems indifferent to the problem of art frauds, which make the artists more powerless. While the involvement of foreign actors in the trading of Vietnamese art does not reduce the intensity of the problem, it seems to continue to drive the price higher. The results have implications on the system of art in Vietnam, the current state of art theft in Vietnam, and the perception of Vietnamese people on art.

1. Introduction

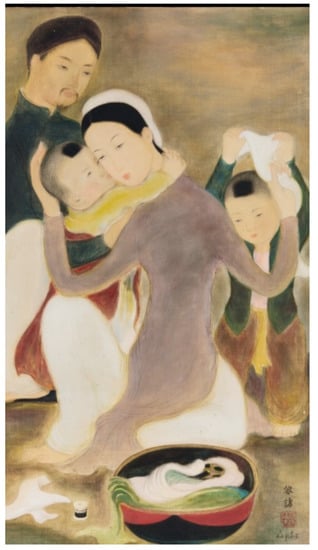

On April 2, 2017, the famous auction house Sotheby’s Hong Kong hammered a painting named Family Life by Le Pho at US$1.2 million. The painting became the first Vietnamese artwork to ever cross the million-dollar mark in the international art market. According to local press, the breakthrough of Family Life is an important recognition of the values of Vietnamese modern and contemporary arts (Bay 2017; Uu 2017). The high price is believed by many to signify a promising future for Vietnamese art as a profitable investment. In reality however, art investment differs from standard financial investment in that its “profitability” included aesthetic pleasures rather than mere financial returns (Kraeussl and Logher 2010). In the case of Vietnamese art, its rich historical and cultural background and its record of assuring financial returns make investing in its emerging market attractive. Yet, the achievement of Family Life also raised worries, as the Vietnamese art market is still ridden with art frauds, which could easily destroy buyers’ trust (Uu 2017). And, as the Vietnamese economy is likely to continue expanding in the future, the art market, too, will grow. In order to ensure a sustainable development of this market, a thorough investigation into the dynamics of the art fraud problem is necessary.

The history of Vietnamese art and painting could be dated back to the 12th century with the prominence of various traditional forms of painting. Traditional painting, though struggling to survive today (Anh 2016; Hieu 2008; Phuong 2005), continues to inspire modern and contemporary art, whose foundation was laid by the French-established Indochina School of Fine Arts in 1925. According to Viet (2018), with the help of Victor Tardieu, founder and first headmaster of the School, it was often alumni of the Indochina School of Fine Arts who went on to become the most famous artists of Vietnam, before attention from European audiences through several exhibitions in Paris. However, their careers were interrupted by the Indochina wars and their works only reemerged in the international market after the country opened up its economy in 1986 with the Đổi Mới (“Renovation”) reforms. This is understandable given that before 1986, Vietnam was a victim of war and the central planned economy. According to Pham and Vuong (2009), the Vietnamese per capita income in this period was around US$125–US$200. It was only due to the gradually emerging market mechanisms in the then-socialist economy, from around 1981, that the income started to increase. In another study, Vuong (2014) shows that from 1991 to 2000, the average annual growth rate of the economy was 7.5%; and after the World Trade Organization full membership initiation in 2007, foreign direct investment peaked at US$71.7 billion in 2008. Currently, Vietnam’s GDP per capita is around US$2,300 (Vuong 2014, 2018a). The rapid economic expansion coupled with the high demand for Vietnamese paintings from international buyers in the 1990s has led to the opening of many art galleries (Trang 2018).

It is appropriate to say that better economic conditions have paved the way for a Vietnamese paintings market. Within only three decades, the Vietnamese people have gone from living off rations to going to McDonald’s whenever they want. The role of money is now even more important because everyone wants to be rich (Napier and Vuong 2013). Artists are no exception. According to Thi Minh (2017), the top four Vietnamese artists who settled in France—Le Pho, Vu Cao Dam, Mai Trung Thu, and Le Thi Luu—started from the same place, but only Le Pho continued to see his paintings surging in price thanks to his artistic originality. On the other hand, the other three artists had, after early successes, begun mass-producing their paintings for profit. Eventually, the value of their paintings stagnated and fell behind that of Le Pho’s, possibly because people can choose the copy version of their paintings.

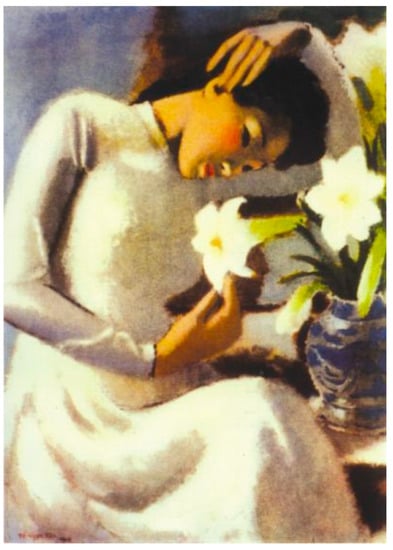

Money motivates not only artists but also collectors and museums to aim for profit without regards for ethics. The story of Thieu nu ben hoa hue (Young Woman with Lily) by To Ngoc Van (Case No. 20, Appendix A, Figure 1) is one example of the complex socioeconomic context behind the scene of Vietnamese fine art. Originally, the painting belonged to Duc Minh, a famous Vietnamese art collector. He lent the painting to the Vietnam Museum of Fine Arts for exhibition purposes only, but the Museum copied it without any formal consent, and later even turned down the collector’s request to donate his collection. The painting had been copied several times. After the collector passed away, one of his sons sold the painting for US$15,000 to an overseas buyer. Since then, there has been no information on the whereabouts of the original Thieu nu ben hoa hue (NLH 2014). On the other hand, according to Ha (2017), another copy of Thieu nu ben hoa hue was sold overseas for US$200,000 before being bought back to Vietnam later at US$400,000.

Figure 1.

Thieu nu ben hoa hue (Young woman with Lily)—To Ngoc Van. The image was sourced from website CINET.VN (NLH 2014).

Today, Vietnamese fine art has a unique identity for its blending of traditional roots and colonial legacy. At the same time, its growth is thwarted by a series of problems, such as the lack of art curators, art consultants, domestic buyers, art investment funds, a legal system to build a sustainable art system, in addition to the societal perception of art and art fraud (Hien 2016; Phuc 2017; Minh 2017; Thong 2017; Trang 2018).

Among all the problems, art fraud is the most reported and discussed problem in Vietnamese media (An 2011; Bay 2016a; Ly 2008), and even The New York Times has dedicated an article to exploring it (Paddock 2017). Scholars have long considered art fraud as a type of art crime, which is legally punishable (Conklin 1994; Durney and Proux 2011). In Vietnamese context, as the above two stories suggest, the problem of art fraud has persisted for long time and it is affecting Vietnamese art. Thus, through the stories of art fraud that we collected as our primary data, the research hopes to answer the following questions and provide an informed opinion to the academic dialogue about Vietnamese art from an emerging market viewpoint:

- How is the economic value of Vietnamese paintings affected by art frauds?

- How do international and domestic actors of Vietnamese art react to the problems?

- What does it mean for the development of Vietnamese art?

2. Literature Review

2.1. The International Art Market

The Vietnamese art market operates similar to the global art market, only on a smaller scale. For instance, auction is the dominant method of transaction and the role of an auction house is very important. Given that famous international auction houses, such as Sotheby’s or Christie’s, have been involved in the bidding of the most expensive Vietnamese paintings, it is imperative to understand the international art market.

What is most noteworthy is the fact that the art market, despite being well-established, has significant ambiguity in its modus operandi. Gérard-Varet (1995) divides the art market into a hierarchy of three submarkets: the primary market, the dealer market, and an international market. The first one is where new artists find opportunities to penetrate the market through galleries, local art patrons, or local exhibition. In the dealer market, new artists will try to move from local to more widely known museums, collectors, and investors. Finally, prestigious auctions controlled by Sotheby’s or Christie’s figure largely in the international market. However, this structure is constantly changing over time. Horvitz (2009) suggests a few key elements to define an art market: (i) profits may not be the primary motivation as historical and psychological values matter when it comes to works of art; (ii) the information on the art market is limited; and (iii) said scarcity of information makes the art market self-categorize into different segments, each with its own characteristics and definition of an investable artwork. The art market, thus, is not always defined by economic factors. Plattner (1996) also agrees with the above hierarchy of the art market and the dominance of wealthy art patrons in the international market. He further investigates how social, psychological, and cultural factors also contribute to the value of an artwork and build up the constant conflict of perspective between art as a commodity and art as art, which creates the paradox that high quality does not equal high price. Within the scope of this paper, as we want to focus on the economic factor of the Vietnamese art market, our argument will be centered around the economic value.

Most scholars seem to agree that art is a good investment. Campbell (2009) suggests that having an artwork in an investment portfolio would generate a small diversification benefit for the investors. Petterson and Williams (2009) argue that investment in art is long-term and has a positive effect on the wealth growth of high net-worth individuals. However, caution is necessary. For example, David et al. (2013) suggest that, due to a lack of transparency in price formation, the art market is inefficient. In a later study, Kräussl et al. (2016) find bubbles in four different fine art market segments from 1970 to 2014.

The conventional economic assumption that the authenticity of a product will determine its value does not seem to ring true in the art market. Bocart and Oosterlinck (2011) discover that an artwork is less likely to be auctioned at major auction houses before it is found to be fake. Moreover, the discovery of fraud usually does not affect the tradability of an artwork, only the price, and slightly so. Day (2014) advocates for a thorough reformation of the art market, which so far has been going against the rules of economics and law and in favor of the art dealers.

2.2. Art Crime and Art Fraud

As the art market is ambiguous but generates a significant amount of wealth (Campbell 2009; Horvitz 2009), art is easily involved in criminal activities. Scholars agree that there are three main types of art crime: art frauds, art theft and confiscation, and destruction of art (Charney 2016; Conklin 1994; Durney and Proux 2011; Fletcher 2017; Hill 2008; Passas and Proulx 2011). Similar to art market, art crime has various motivations, and the aim is never purely economic. Usually, there is also the desire to possess, to show social status or knowledge, or simply for aesthetic pleasure (Durney and Proux 2011). According to Piano (1993), art crime is also often connected to money laundering by criminal organizations. Hill (2008) suggests art theft is a way for criminals to declare their egos, especially when it involved high-profile artworks.

Among all types of art crime, art fraud is the most pressing problem for the art market (Alder and Polk 2007), because it generates the most benefit and is hard to discover. There are several types of art fraud including fakes, forgery, copy, and plagiarism arts. Durney and Proux (2011) define fakes and forgeries according to the methods: fakes replicate the style of an artist while forgeries copy the painting. While fakes and forgeries is clearly art fraud, copies are harder to define as a type of art fraud because in some cultures, copying is not out of the norm (Han 2018). Benhamou and Ginsburgh (2002) distinguish copies and forgeries by their intention, and call for a separate market for copies as the latter pays tribute, reinterprets, and adds value to the originals, whereas forgeries and fakes are only made to deceive. Similarly, Grasset (1998), through an analysis of fake art from three perspectives—aesthetics, art history, and economics—notes that fake art might be a problem from a market perspective but in no way affects the aesthetic perception of the audience. Plagiarism, by comparison, is not so well defined in art research because in the creation process, an artist could be inspired by the works of others (Ashworth et al. 2003; Purtee 2016). The phenomenon, then, is described as “intermediality, synthesis of arts, fusion of arts, copying, and adaptation” (Unicheck 2015). The term “plagiarism” is mentioned more often when it comes to copyright or education issue.

Preventing art crime is crucial for the protection of humanity values and wealth (Alder and Polk 2007; Durney and Proux 2011; Fletcher 2017; Hill 2008). In the context of a small and emerging art market such as that of Australia, James (2000) claims that forgery and fakes make Australian art untrustworthy to the international art market, damage its reputation and reduce its economic value; meanwhile, the current Australian legal system is incapable of dealing with the ambiguity of art fraud (Alder et al. 2011). Similarly, Vietnamese art is currently facing the poisoning effect of art fraud but there is almost no thorough investigation into this problem.

2.3. The Vietnamese Art and Its Market

Unlike the voluminous studies on the international art market, the Vietnamese art market has rarely been explored. Much of the literature on Vietnamese art only briefly discusses the art market while examining topics such as history, identity, or law separately. This part will provide an overview of the historical development of Vietnamese fine art.

The establishment of the Indochina School of Fine Arts in 1925 is said to mark the beginning of modern and contemporary Vietnamese art for it cultivated an environment for Vietnamese culture and French style to blend together in a way that reflected both patriotism and anti-colonialism (Safford 2015; Taylor 1997, 2007, 2012). One recent study (Van Doan 2017) diverges from the literature and instead argues that before the Indochina school, Le Van Mien (1873–1943), Nam Son (1890–1973) and Thang Tran Phenh (1890–1972) already stood out as artists in the time when painters were commonly called artisans. The author claims that these three artists should be seen as the foundation of modern and contemporary Vietnamese art. According to Quoc (2014), Nam Son was one of the founders and also a teacher of the Indochina School of Fine Arts. He also achieved recognition in 1923 when he and Thang Tran Phenh joined one of the first art exhibitions in Vietnam, and later in 1930 when a china-ink painting of Nam Son was exhibited in Paris. Nonetheless, it was Victor Tardieu, the French founder of the Indochina school, that had transformed Vietnamese students with his progressive ideas (Taylor 1997; Viet 2018). To sum up, the foundations for Vietnamese fine art were first laid down by the individual efforts of prominent artists, such as Nam Son, Thang Tran Phenh and Le Van Mien, and from 1925 onwards, the Indochina school and its students pushed for substantial changes in the modern Vietnamese art scene.

What should be noted is the different opinions among Vietnamese and Western scholars on the impact of the Indochina School of Fine Arts. Curiously enough, the Vietnamese scholars consider the Indochina school as the beginning of a new era for Vietnamese art, while the Western scholars reject the school’s contribution to Vietnamese culture and regard it as a tool of colonial and cultural assimilation. Despite this lack of consensus, it is clear that the colonial art school, with its fusion of French art style and Indochinese cultural values, did help bring about a unique identity to Vietnamese fine art and, in turn, benefitted Vietnamese artists in the international market (Safford 2015; Taylor 1997, 1999).

On this identity, it is the constant yearning for the motherland, the Vietnamese root that has inspired numerous Vietnamese artists to paint and tell their stories. Such a strong sense of national identity has become so widely accepted that artists of Vietnamese origins are often subject to their Vietnamese identity regardless of their current nationality or residency (Taylor 2001, 2007). However, this convention might hinder creativity and drive Vietnamese artists to play safe rather than aiming for riskier subjects (Taylor 2005). In the contemporary context, researchers argue that Vietnamese artists have created a new individualistic identity as they tried to navigate between the traditional and the new and experimental schools of art (Kraevskaia 2009; Leigh 2001). Moreover, Taylor (2012) suggests that Vietnamese artists, as a collective class, was the “key players in the movement toward a civil society,” as it was a class that continuously helped to define and strengthen not only art but also Vietnamese cultural and social values. They are in fact representative of the middle-class and intellectual elites of Vietnam despite the economic situation or political atmosphere in the country. The cultural identity of Vietnamese art also helped heal the aftermath of the Vietnam War (Granzow n.d.). Many scholars have advocated for Vietnamese fine art to be recognized as a main part rather than an outlier of the global art scene and for Vietnamese artists to make use of outside opinions to earn their place in the international art market (Taylor 2001, 2005).

If identity is key to the development of Vietnamese art, then art frauds are the obstacle that keeps Vietnamese art from greater success. Taylor (1999) explores the case of Bui Xuan Phai and his Hanoi’s Old Quarters paintings to understand why fake paintings of his works are abundant in the market. She attributes the demand for Phai’s paintings and also Vietnamese art in general to the Western depiction of Vietnam as an “authentic” Asian country. The nostalgic image of the Old Quarter streets that originated from Phai’s works came close to the aforementioned ideal and fulfilled the demand regardless of whether the painting depicting this was authentic or fake. From a formal perspective, Bosch (2004, 2010) argues that Vietnamese artists, despite their potentials, lack the professional skills and expertise to create a fully-fledged art world. More importantly, from a legal perspective, the law does not protect Vietnamese artists as it is supposed to, which results in frequent violations of intellectual property law, and Vietnamese artists’ reliance on foreigners to sell their paintings.

2.4. Research Questions

Studies have shown characteristics and existing problems of the art market (Bocart and Oosterlinck 2011; David et al. 2013; Horvitz 2009). Among existing problems, art crimes need to be prevented because they harm art economically, historically, and culturally. For small, nascent art markets, art crime, and especially art fraud, can be detrimental to the image of entire said art markets and cause trouble for the art system (Alder et al. 2011; James 2000).

In Vietnam, studies have shown that the demand for Vietnamese art mainly came from the West, with little attention paid to the authenticity and instead directed towards only the images portrayed in the paintings (Taylor 1999). When Vietnamese art is more integrated to the world, the market arisen from that demand has become defective and the artists become the victims (Van den Bosch 2004, 2010).

In recent years, the value of Vietnamese art has been rising steadily in the international market, along with stable growth of the domestic market. Yet, the problem of art frauds is still rampant and exerts negative impacts on both markets, and eventually the Vietnamese art. In order to foster a more sustainable development of the Vietnamese art, first, it is important have a thorough understanding of this multi-faceted problem. Hence, this paper aims to answer the three following questions:

- How is the economic value of Vietnamese paintings affected by art frauds?

- How do international and domestic actors of Vietnamese art react to the problems?

- What does it mean for the development of Vietnamese art?

In order to answer these questions, we use a dataset that contains 35 cases of art fraud that we have collected from news outlets. From our observation, the local media only gives brief coverage on the art itself, while a thorough discussion is often focused on the economic values of Vietnamese art and serious problems like art frauds. For instance, when a Vietnamese painting was suspected as fraudulent but still made it to a major auction house, the press paid extra attention and discussed the problem in detail. Therefore, we have decided to collect data in this direction and used it as a proxy to explore Vietnamese art and its market.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

The dataset contained 35 cases of art frauds collected from Vietnamese news outlets. We looked up cases of art frauds on popular newspapers such as Tuổi Trẻ, Thể thao & Văn hóa, or Dân Trí, as well as an underground blog on Vietnamese art: soi.com.vn. Keywords such as “forged painting,” “fake painting,” “forgery artwork,” “fake artwork,” and “Vietnamese art market” were used on the Google search engine to find data. Additionally, an article that covers a particular case usually mentions similar cases as well. Therefore, we use that information as starting points to search for new cases and complete the data on those cases. Even if we could not find complete information on a case, it would still be included in the final data sheet. Eventually, we were able to complete missing data through the information provided by interviewed experts. Moreover, our interviewed experts also gave their opinions on Vietnamese art and its problems. The opinions are used throughout the article to better illustrate the result and discussion.

We recorded 35 cases of art frauds including forgery, fakes, plagiarism, and copy. The final data sheet is in Appendix A, with complementary visual images in Appendix B, Appendix C, Appendix D, Appendix E, Appendix F, Appendix G, Appendix H, Appendix I, Appendix J, Appendix K, Appendix L, Appendix M, Appendix N, Appendix O, Appendix P, Appendix Q, Appendix R, Appendix S, Appendix T, Appendix U and figures in the article. The images in the article are used under the permission to use published works without obtaining permission and paying royalties, remuneration according to the Article 25, Vietnam Law on Intellectual Property of Vietnam 2005 as amended in 2009 (Link: cov.gov.vn). The final data sheet consists of 35 lines of data representing 35 cases. Each line consists of the information that is necessary for analysis: name of the painting, the author, the time that the case happened; types of transaction: auction, direct trading, or exhibition, estimated and sold price, seller, and buyer; agency: museum or auction house, the people who guarantee or doubt the authenticity of the painting; and types of art frauds: fake, forgery, copy, or plagiarism, whether the fraud is suspicion or confirmed, what had been done, and the source of the cases’ information.

3.2. Methods

The research mainly employed qualitative analysis and comparison of cases in our dataset in order to draw answers to our research questions, which would later be discussed for further insights. To answer the first question, the economic values of Vietnamese paintings involved in frauds were determined based on information regarding transactions. Next, the second question revolved around the reaction of actors in the Vietnamese art market to art frauds, analyzed based on the status of cases, as well as the response from people involved in the cases of art frauds and transactions of fraudulent paintings. Finally, after examining findings from the first two questions, combined with expert opinions, we aimed to provide an insightful discussion and forecast the future for the Vietnamese art. Expert A is Bui Quang Khiem (Hanoi College of Arts); Expert B is Nguyen Hai Yen, a retired art critic who spent her entire life studying Vietnamese fine arts while working for The Vietnam Museum of Fine Arts.

The decision to use this method was based on the small number of the cases that allows the authors to analyze the content of each case in more details. Opinions from Vietnamese art experts are also included in the discussion.

Records of our interviews with art experts were edited following the methods employed in the work of Joseph Prögler (1991). All interviews and related data will be deposited for open-access, based on the principles suggested by Nature Scientific Data (Vuong 2017).

3.3. Materials

Based on the information, the data had some notable characteristics. First, each of the paintings belongs to one of three main types of transaction:

- 18 cases through auction (5, 6, 7, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 22, 24, 26, 27, 28, 32);

- 8 cases through exhibition (1, 8, 9, 25, 29, 31, 33, 35);

- 8 cases through direct selling (2, 3, 4, 10, 20, 21, 23, 30).

Secondly, auction cases have the highest prices among the three types of transaction, ranging from US$12,500 to US$535,207. While the estimated and sold price of an auction is disclosed on the website of the corresponding auction house, the price of the directly sold paintings is mainly a mere estimation or completely unknown.

Finally, there are some cases with very little information, and are often historical. The newspapers provided detail information on cases that happened from 2016 onward. On the other hand, older cases, such as the two frauds in 1997 and 1983, were only briefly mentioned. Our interviewed expert provided information on seven cases (26, 28, 29, 32, 33, 34 35), and the authors were able to cross-check only three cases with information from the news report. Four cases (33, 34, 35, 36) were not reported by the media at all.

Five significant cases will be described in detail in the following sections.

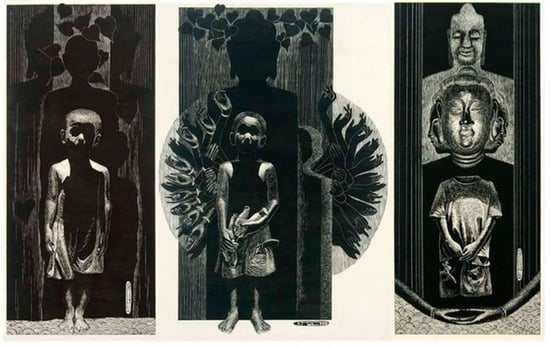

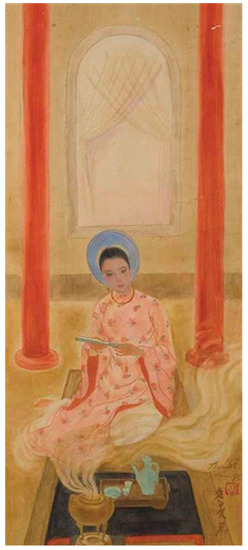

3.3.1. An Lac (Serenity) by Nguyen Truong An Plagiarized A di da phat (Amitabha Buddha) by Nguyen Khac Han (1)

The lacquer painting An Lac (Serenity) (Figure 2) by young artist Nguyen Truong An won a prize of five million VND (around US$250), and being exhibited from August 22 to September 6, 2017. at the Ho Chi Minh City Museum of Fine Art.

Figure 2.

An Lac—Nguyen Truong An painted in 2017. The image was sourced from Tuoi Tre Newspaper (Diep 2017a).

However, Le The Anh, a lecturer, found out that the painting plagiarizes a woodcarving painting A di da Phat (Amitabha Buddha) (Figure 3) by Nguyen Khac Han—which won a gold medal in the Vietnam Fine Art Exhibition in 2015. After the revelation was posted on Facebook and reported by news media, the Museum removed An Lạc from the exhibition. According to the Vice President of Ho Chi Minh City Fine Arts Association, Nguyen Truong An admitted his wrongdoing and had sought forgiveness through an apology letter (Thi et al. 2017).

Figure 3.

A di da Phat—Nguyen Khac Han painted in 2015. The image was sourced from Tuoi Tre Newspaper (Diep 2017a).

3.3.2. The Fake Paintings of Pham An Hai (2, 3, 4; Appendix B and Appendix C)

The collector C.H.L bought five paintings in May 2017 for the price of 285 million VND (around US$12,497) from Bao Khanh, an acquaintance of the painter Pham An Hai. After that, the collector sent the paintings to a frame-maker. It was the latter who found out the paintings were fake and contacted Pham An Hai immediately.

Among of the five artworks, a painting named Du am pho co (The repercussion of the Old Quarter) (Figure 4 and Figure 5) was still in the possession of Pham An Hai at that time. Two of them were the work of a painter named Nguyen Ro Hung, carrying the forged signature of Pham An Hai.

Figure 4.

Fake Pham An Hai’s Du am pho co. The image was sourced from Tuoi Tre Newspaper Thi Minh (Viet 2017).

Figure 5.

Authentic Pham An Hai’s Du am pho co. The image was sourced from Tuoi Tre Newspaper (Viet 2017).

After that, Pham An Hai called the collector to explain the situation, and also shared the story on Facebook.

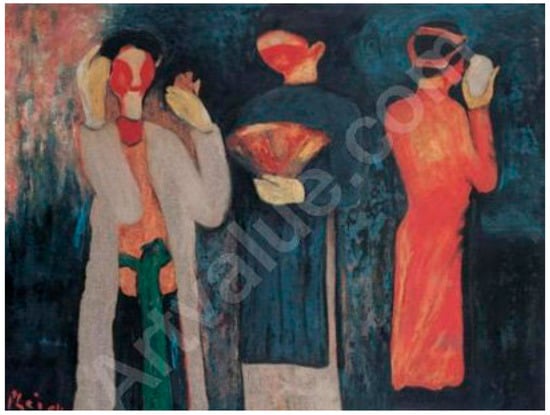

3.3.3. Truu Tuong (Abstract) by Thanh Chuong and 17 Paintings of Vu Xuan Chung (8, 9, 10; Appendix F)

A painting named Truu Tuong (Abstract) (Figure 6) with a signature of Ta Ty (1922–2004), a famous Vietnam War artist, and 16 other paintings were shown in the exhibition “Paintings Returned from Europe”. The exhibition was a collaboration between Ho Chi Minh City Museum of Fine Arts and Vu Xuan Chung, the owner of the exhibited collection. Vu Xuan Chung bought the 17 paintings from Jean-François Hubert, a controversial Vietnamese art expert.

Figure 6.

Truu Tuong—Thanh Chuong (signed Ta Ty). The image was sourced from Tuoi Tre Newspaper (Khoa 2016).

The introduction of Truu Tuong claimed it was drawn by Ta Ty in 1952. However, Thanh Chuong, a well-known contemporary painter, recognized that was a painting which he drew in the 1970s. After the accusation from Thanh Chuong, Jean-François Hubert sent a doctoring image (Figure 7) to the media in order to show the authenticity of the painting. To counter the doctoring image, Thanh Chuong showed the draft of the painting to the public. Both Vu Xuan Chung and Jean-François Hubert had no comment about it.

Figure 7.

The doctoring image from Jean-François Hubert. The image was sourced from Tuoi Tre Newspaper (Vy 2016).

At first, Ho Chi Minh City Museum of Fine Arts concluded that 15 out of the 17 paintings exhibited were not created by the introduced artist, and two paintings had forged signatures of painters Ta Ty and Sy Ngoc. Therefore, they temporarily held the paintings for further examination. However, on July 22, 2016, the Museum returned the painting to Vu Xuan Chung (Bay 2016c; Quan 2016). In 2017, according to New York Times, Chung was able to sell one of those paintings for US$60,000 (Paddock 2017).

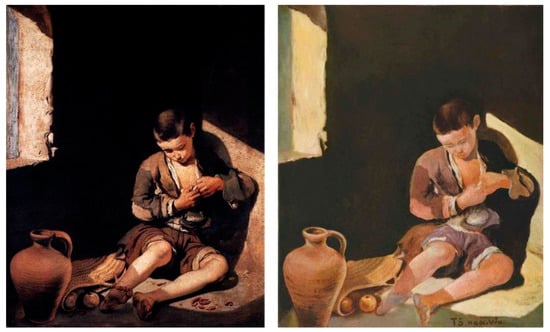

3.3.4. Mo ve mot ngay mai (Dreaming of Tomorrow) by To Ngoc Van (5)

The painting Mo ve mot ngay mai (Dreaming of Tomorrow) by To Ngoc Van (Figure 8, Oil on canvas, 47.5 cm × 40 cm, painted circa 1940, Signed “To Ngoc Van” on lower right) was auctioned at Christie’s Hong Kong. According to their website, the auction house estimated the price was around US$9000–US$11,000USD and finally hammered at US$44,591. However, a Vietnamese newspaper wrongly reported the final price as up to US$350,000 (Thi 2017). According to the information on the painting, Claude Mahoudeau acquired the painting directly from To Ngoc Van in Hanoi in 1943. Jean-Francois Hubert even wrote essays on the painting.

Figure 8.

The young beggar (Left) and Mo ve mot ngay mai (Right with signature). The image was sourced from The Thao & Van Hoa Newspaper (Diep 2017b).

After the painting was hammered, a Vietnamese art expert named Pham Long found a striking similarity between the painting and The Young Beggar by Bartolome Esteban Murillo, a 17th-century Spanish painter. Because of the case’s severity, the Vietnam Fine Arts Association have reported to the Ministry Of Culture, Sport and Tourism, yet received no response (Diep 2017b).

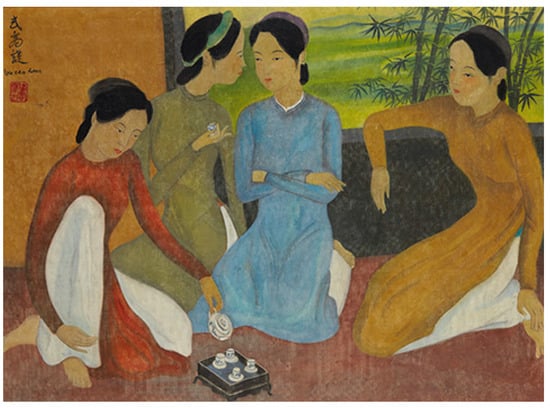

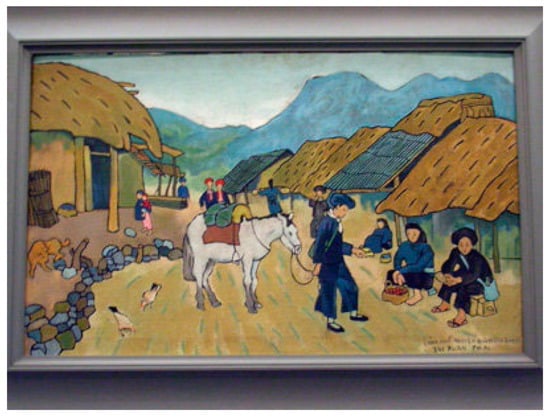

3.3.5. Thieu nu uong tra (Ladies Tea Time) by Vu Cao Dam (15)

The auction website Auction.fr posted the painting Thieu nu uong tra (Ladies Tea Time) (Figure 9) by Vu Cao Dam (gouache and ink on silk, 59 cm × 80 cm) on May 12, 2016. The estimated price of the painting was from US$18,000 to US$25,000. Art expert, Ngo Kim Khoi, found out this painting was fake. The real painting (Figure 10) is larger (78 cm × 114 cm), and was exhibited at Cernuschi Museum in 2013. The painting has a clear background so the Auction.fr had been obligated to refund the buyer’s money in full (Hoa 2016).

Figure 9.

Thieu nu uong tra—Vu Cao Dam (fake); auctioned at Auction.fr, May 2016. The image was sourced from The Thao & Van Hoa Newspaper (Bay 2016b).

Figure 10.

Thieu nu uong tra—Vu Cao Dam (real). Exhibited at Cernuschi museum, September 2012–January 2013. The image was sourced from The Thao & Van Hoa Newspaper (Bay 2016b).

3.3.6. Organized Frauds by Xuongtranh.vn (21)

In early 2018, the website xuongtranh.vn started to publicly sell many faked and copied paintings. Painters found out about the situation and raised complaints and public service announcements on Facebook, with palpable evidences: the original paintings were still stored in their atelier, yet copies were already up for sale on xuongtranh.vn. A few days after that, xuongtranh.vn posted a public apology and took down all of their offers.

4. Results: Induction from the Cases

4.1. The Economic Value of Vietnamese Artworks

The economic value of Vietnamese artworks that have unfortunately gotten involved in frauds remains quite unaffected. Among the 35 cases we have recorded, 18 were proven to be fraudulent, while the 17 remaining paintings retained a status of suspected art frauds, as no concrete evidence could be found to prove that the paintings were fraudulent besides the visual and technical analysis from experts (usually Vietnamese). Besides this, auction houses as well as private buyers did not hesitate to overlook the controversial nature of these artworks in favor of obtaining them.

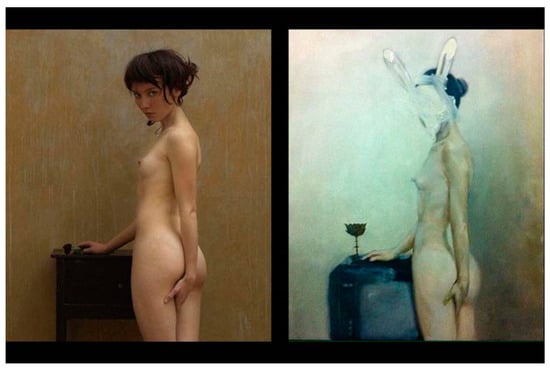

For instance, Le Pho’s Gia dinh (The Family) (19; Appendix M) was hammered at US$535.207, or Phong canh (Paysage) by Nguyen Gia Tri was bought for US$381,559 (27; Appendix R). A Vietnam actress spent US$210,000 on a painting drawn by Le Pho (23) in Hong Kong. The painting has been through several auctions, therefore, people are unable to dismiss the authenticity of the painting (Bay 2016a). In 2017, the CEO of Playboy Vietnam paid US$25,000 for Co gai tho (Rabbit Girl) by Nguyen Phan Bach (28). The problem is Co gai tho strikingly resembled a French painting, at least 80–90% similar (Figure 11). Phan Chanh clumsily defended against the criticism of plagiarism by saying his painting is a remake of the French painting, and it is about the concept rather than the concrete object depicted in the painting, such as the model’s posture (Nguyen 2017a, 2017b). In the case of Vu Xuan Chung’s collection (8, 9, 10; Appendix F), despite its infamous reputation, Xuan Chung was still able to sell one of the paintings in the collection for US$60,000 a year later (Paddock 2017).

Figure 11.

(Left) The French artist’s painting. (Right) Co gai tho—Nguyen Phan Bach. The image was sourced from Thanh Nien Newspaper (Nguyen 2017a).

In short, as it seems, the Vietnamese art market did not suffer from any economic damage resulting from art frauds. In almost all 35 cases in our dataset, transactions occurred, either initiated by auction houses or private buyers. Given that economic profit has become very crucial to artists today, as we have demonstrated in previous sections, the fact that there is almost no economic penalty to art frauds might tempt some artists to make ends meet using fraudulent methods.

4.2. The Attitude of Artists and Institutions of Authority

Because market powers did nothing to deter artists from committing art frauds in the Vietnamese art market, as demonstrated above, the attitude of artists and institutions of authority faced with fraudulent art scandals is a key determinant in solving the problem of art frauds. Unfortunately, as will be shown with our data, seniority, youth, and other reasons are prioritized over authenticity. In fact, three plagiarized paintings have been allowed to participate in the Fine Art Awards and be exhibited: An Lac by Nguyen Truong An (1), Binh minh tren cong truong (Dawn on the Construction Site) by Luong Van Trung (29; Appendix S), and Bien chet (Dead Sea) by Nguyen Nhan (31; Appendix U). Despite the formality of the Fine Art Awards, it was only during the exhibitions that the audience found out the similarity between the exhibited paintings and certain works done by other artists. The Binh minh tren cong truong and Bien chet cases received rightful penalties, but in the case of An Lac, the Vice President of the Ho Chi Minh City Fine Arts Association had tried to rationalize the painter’s misconduct by bringing up his young age and forgave him under the pretext that he can learn from this misstep and grow in the future (Thi et al. 2017). In the Mo ve mot ngay mai (5) case, the Ministry of Culture, Sport and Tourism did not respond to the plea for help from the Vietnam Fine Arts Association (Diep 2017b). This brings into question how the screening and judging process of the Fine Art Awards has been carried out, especially considering its perceived prestige as a national level award.

For a senior artist like Pham An Hai (2, 3, 4), he would prefer a stronger action but the legal system was inadequate at protecting the intellectual property of artworks and hindered him from taking further legal actions (Van den Bosch 2004, 2010; Viet 2017). Painter Le The Anh (Nguyen 2017a) expressed his concern for how most cases are resolved: “once the art thief came and apologized, it was deemed good enough. The reason is that they are usually family, and you can only drink to express your frustration. But I don’t think it’s a good way to go about it. It’s a persisting bad attitude that turns us all into cowards.” The evidence supports Bosch’s (2004, 2010) findings on the lack of an authoritative system to support Vietnamese artists.

As Vietnamese paintings continued to reach higher prices in the art market, the Vietnamese artist is more motivated by the thirst for wealth and fame. Young artists were tempted to take illicit “shortcuts” in the early stages of their career, while senior artists, despite being aware that art fraud is unethical and harmful to the growth of Vietnamese art, were helpless against the circumstances. The inappropriately forgiving attitude towards art fraud in Vietnam, as shown in the Vice President’s comment on the case of An Lac (1), seems to be linked to the tolerance aspect of cultural additivity in Vietnamese culture (Vuong et al. 2018a). The attitude is also a direct result of years of self-copying. There are famous artists who remade their own paintings (Minh 2017). According to the Expert B (An 2016), the Vietnam Museum of Fine Arts used to replicate paintings for the purposes of exhibiting overseas and protecting originals during the war. In fact, Art Expert A had witnessed his peers self-copying many times such as the story of the Vice President of Vietnam University of Fine Arts (34). In his opinion, it shows that Vietnamese artists have no self-discipline. This is especially true when compared to China; for example, in a similar case of art plagiarism, the offender lost his job and got banned from art competitions for life despite being a high-status professor (Leng 2018). However, culture, seniority, or any other reason, must not tone down or dismiss the gravity of art frauds.

In other words, official authority in the art system of Vietnam, such as institutions of higher education in fine arts, management boards of art museums, ministerial authority, artists associations, etc., tend to turn a blind eye to art frauds. Their reasons varied: lack of incentive to take matters seriously, indulgence due to close relationships within artist circles, and conformism to a culture that has learned to accept and absorb behaviors that could have been previously considered deviant or foreign (cultural additivity). As a result, the institutional and legal system offered no help for artists who wished to reclaim their intellectual property rights, nor does it act as a counter power to the art market that does not penalize fraudulent paintings.

4.3. The Role of Foreign Actors

The interest from famous auction houses and international experts in Vietnamese art is a good sign of development. Nonetheless, their presence does not seem to help Vietnamese art growing in a positive direction. Christie’s and Sotheby’s appear in a total of 13 fraud cases: Christie’s in 4 cases (5, 6, 7, 18; Appendix D and Appendix E) and Sotheby’s in 7 cases (11, 12, 16, 17, 19, 24, 27; Appendix G, Appendix H, Appendix K, Appendix L, Appendix M, Appendix O and Appendix R). There are two other lesser-known auction houses: Auction.fr from France (15, 22; Appendix N) and Lasarati from Singapore (26; Appendix Q). Among these, all the cases from 2008 to 2017 remained suspicious without concrete evidence.

The so-called Vietnamese art expert Jean François Hubert has written many essays on three Vietnamese paintings at Christie’s Hong Kong auctions (5, 6, 7). However, he becomes a scandalous figure with his involvement as the seller who sold fraudulent paintings to Vu Xuan Chung (8, 9, 10), despite a clear conflict of interests. When the suspicions on Truu Tuong and the collection arose, he authenticated the collection himself to justify the transactions using forged documents like the doctoring image as shown in Figure 7 (Nguyen 2016b; PV 2016).

There were two cases—Song Da (Da river) (18) and Thieu nu uong tra (15)—in which the auction houses finally had to apologize and refund to the buyers. In the Thieu nu uong tra case, a record of an exhibition at Cernuschi Museum in 2013 had proved the fake status of the auctioned painting (Bay 2016b). In the case of Song Da, the press only reported the final outcome of the painting without detailed information. The case happened in 1997, when Vietnamese art was still new to the international auction, so it was possible that the auction house wanted to avoid controversy and media attention. In addition to this case, according to Taylor (1999), Sotheby’s and Christie’s put away 60 percent of Bui Xuan Phai’s paintings that were ready for auctioning due to their dubious origins. Hence, the controversial nature of so many of Vietnamese paintings was a serious problem to overseas auction houses in the past. However, in 2008, Sotheby’s still ended up auctioning four paintings by Bui Xuan Phai. All of this shows that the international auction houses have gotten accustomed to the controversial nature of Vietnamese art. According to Art Expert A, the attention from international auction houses only increases the price of Vietnamese paintings, not the quality.

In that circumstance, the rise of Vietnamese auction houses like Chon or Ly Thi might be the opportunity for Vietnamese art to improve. However, one must not forget that Chon was the agency that organized the auctions of Pho cu (13) and Co gai tho (28), the two copied and plagiarized paintings. Furthermore, according to Art Expert B, during an auction of a painting supposedly created by Nguyen Van Ty at Chon, the daughter of the artist came and confirmed that the paintings were not authentic (32).

Art Expert A admitted that, motivated by financial benefits, artists are willing to self-plagiarize and dealers are willing to sell frauds. In a transition economy like Vietnam, such motivation is even stronger as most Vietnamese people are striving for wealth, which explained the high price of the Vietnamese paintings despite the suspicion on their authenticity.

5. Discussion

5.1. A Significant Lack of Art Investors

Vietnam is seeing more and more people become millionaires, yet few cared to invest in art because of the dysfunctional art system characterized by the problems above. In the past, there were art collectors who stood out, the most famous being Bui Dinh Than, also known as Duc Minh, owner of a well-known gallery in Ha Noi. He was a wealthy businessman and a proud art lover who spent his time collecting paintings as a hobby. Another example would be Nguyen Van Lam, who also owned a famous collection as well as a café, Café Lam, which acted as a gathering place of artists. Both of them had close relationships with famous painters. Before Đổi Mới, they preserved paintings out of friendship and appreciation for art. Artists often came to Café Lam and paid for the coffee in paintings. After Đổi Mới, the economic atmosphere was not as rigid as it used to be. Paintings started to generate a fair amount of wealth for the owner, and the Vietnamese art market began to grow. Yet, devoted art collectors, such as Duc Minh or Nguyen Van Lam, seemed to have disappeared.

There are a few possible reasons for the disappearances of art collectors in the Vietnamese art market. Firstly, in the stories of Co gai tho (28), the actress’ Le Pho painting (23), or Pham An Hai’s paintings (2, 3, 4), and especially the Vu Xuan Chung cases (8, 9, 10), the buyers were willing to pay a lot of money for art, only to be deceived. There was also no legal measure or insurance policy to protect them from art fraud, which is highly discouraging to art lovers. It is not a surprise that only the most passionate art collectors would continue. Given how toxic the local market is, the international market had become a trusted destination for Vietnamese art collectors. However, as the results of our data have suggested, being handled at international auction houses does not necessarily mean a painting is immune from suspicion. Finally, financial capacity is also a problem to Vietnamese buyer, especially in the international market. Vietnamese paintings are worth more than thousand dollars nowadays; it is not easy for Vietnamese buyers to compete with foreign buyers.

5.2. Unhealthy Art System

The modest number of art collectors in Vietnam is symptomatic of an art system that lacks important components to create a healthy environment. The influence of art experts in Vietnam is extremely limited when their opinion is often “lost in time like tears in the rain” (Scott 1982). In the cases of buyers C. H. L (3, 4, 5) and Vu Xuan Chung (8, 9, 10), they bought the paintings merely based on the reputation of the sellers rather than an insightful opinion of expertise. While Vietnamese art experts often analyze and share insights about Vietnamese paintings on the news media. However, in an international context, their concerns are rarely acknowledged by international auction houses, not to mention the majority of mainstream essays on Vietnamese paintings have been written by a foreigner.

The art institutions, such as museums and galleries, are only for exhibition. Duc Minh and his collection had been borrowed multiple times by the Vietnam Museum of Fine Arts, and the latter had copied these paintings without permission from the owner or the artist. As another example, the painter Van Tho once sent his original painting to Gallery Viet Fine Arts, but the gallery swapped the original with a fake one to put on display, which made Van Tho so angry that he slashed the fake one right in the gallery (Huong 2016) (25).

Finally, the art scene in Vietnam suffers from a small but complex web of personal relationships, which formed an almost impenetrable circle. In the case of Pham An Hai, the seller and the frame-maker were acquaintances of the artist. Moreover, many art experts turned out to be children of famous artists: Bui Thanh Phuong is Bui Xuan Phai’s son, and To Ngoc Thanh is To Ngoc Van’s son. The complexity of these relationships in Vietnam might be strange to the outsider, but it feels natural to most Vietnamese: ”Sometimes Vietnamese sign a commercial contract with each other just to start establishing a new relationship” (Napier and Vuong 2013). Once a personal relationship is involved, it is harder to solve the problem rationally. Even though institutions, such as galleries, museums, and local auction houses, as well as figures of authority, such as art experts or university direction board members, were supposed to strengthen the growth of Vietnamese fine art, it seems as if the price of Vietnamese paintings, be they fraudulent or authentic, was the only thing doing the growing.

5.3. Art Fraud as the Enemy of Art Theft in Vietnam

On a “bright” side, the dubious authenticity of so many Vietnamese paintings is a potential reason for why Vietnamese galleries or museums did not face the issue of art heist. On one hand, Vietnamese paintings are relatively inexpensive and unpopular compared to artworks done by artists from other countries throughout the history of art. Art thieves often targeted high-value paintings, examples being the heist of Leonardo Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa in 1911, Edward Munch’s The Scream in 1994, or the stolen 500-million-dollars worth of artworks from Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, mainly for the purpose of ransom or resale. It was safe to say that Vietnamese art would not be on the target list anytime soon. On the other hand, and strangely enough, it is actually the serious issue of art fraud that prevents art heists from happening. In fact, art heists always aim for paintings that are highly regarded and unique, while in Vietnam, even a national award-winning painting would have at least one identical version.

5.4. Lessons from Other Markets

In the rest of the world, there are other local art markets that face the same problem as the Vietnamese art market. In Australia, their acrylic paintings suddenly became “contemporary Aboriginal art” when the artists sought for outside audience and different people bring it to the international art market (Myers 2002). The jump from the local market to the international one has made Aboriginal art face the problem of art fraud that the Australian legal system is not ready to deal with (Alder et al. 2011). In the United States, the prestige of a cultural hub like New York dwarfs the small art community like in St. Louis, and Plattner (1996) shows that profit was never the main motivation for the artist. The experiences of these local art markets are valuable lessons for Vietnamese art including the battle against art frauds and the way art functions in a local market.

5.5. Future Direction for Vietnamese Artists and Investors

The results of this study has shown there are many economic incentives and cultural excuses for art frauds. Look at a wider context, to Vietnamese people, at least traditionally, paintings were never the objects of value, but mere decorations. Vietnamese has an old saying: “First calligraphy, second painting, third stoneware, fourth woodwork,” referring to the four common decorative items traditionally present in every household, especially during Tet holiday. The artist, therefore, was seen as a mere maker of decorative items. Many artists make ends meet through commissions. For instance, Thanh Chuong has produced 600 paintings for Daewoo hotels in Hanoi (VnExpress 2002). Those paintings might become valuable as time goes by; however, uncertain as the future is, instant income from contracts or copied, even self-copied, paintings is much more desirable. Art Expert A points out that the perception of the people on Vietnamese fine arts is often misled by wistful, baseless proclamations, such as the “consensus” that Vietnamese lacquer painting is among the best in the world, despite modest prices and share of Vietnamese works in the international lacquer painting market. He agrees that many problems, both subjective and objective, have reduced the quality of Vietnamese art. At some point, art in Vietnam has become almost stripped of philosophical values and artistic self-expression.

When the Vietnamese economy opened up and embraced market mechanisms, the livelihood of people changed and the Vietnamese had to again learn to get used to the new ways of life. Napier and Vuong (2013) suggested that since the mid-1990s, Vietnamese people have had a profound lesson to learn: “Money = hard work” first, and “being rich” only comes later, if at all. Regarding the art market, the lesson to learn is that art is not and should not be a just quick and easy way to reach the “being rich” part; not when “creating is living doubly” (Camus 2005). If Vietnamese art had any chance to improve at its core, it would have to be the artists themselves who pioneer for changes by being innovative. That being said, artists alone could not change the whole system; every other actor, such as art experts, curators, museums, galleries, etc., must also be willing to change for the better. This kind of action-taking, both by artists and art institutions, is still lacking. As an implication to the authority and policy makers, this should be a cue to refine the legal foundations of the art system of Vietnam. In term of the art market, as the GDP per capita in Vietnam amounts to just around US$2000, it is understandable that Vietnamese people would rather minimize risks with familiar investments, such as real estate, or periodic health examination (Vuong et al. 2018b), than venturing a fortune on a work of art. However, if the GDP per capita rises to US$5000 and the super-rich population increases, the art market of Vietnam might live up to its potential.

6. Conclusions

Vietnamese paintings have become high-price commodities in the international art market. However, the good characteristics of Vietnamese art, such as rich cultural elements and skillful techniques, may be obscured by many problems, especially art frauds. In this research, we highlighted the gravity of art frauds through an exploration of 35 cases in Vietnamese fine art. We found that regardless of the suspicion on the paintings’ authenticity, the fraudulent paintings are still able to trade because of the willingness from auction houses and buyers, as well as the lack of control from the authority. In this situation, the artists are powerless. The result also implies the absence of art investors, the limited influence of art connoisseurs, or the close circle of relationship among artists and friends. Finally, the tolerant attitude towards plagiarism and fraud seems to be deeply rooted in the Vietnamese culture as well as in the traditional education, which has, for a long time, prioritized rote learning over original and critical thinking (Do Ba et al. 2017; Vuong 2018b; Vuong et al. 2018a). Therefore, Vietnamese people need to change their perception on art and realize the philosophy in art.

Cultural richness is the core identity of Vietnamese art and what makes it attractive. However, Vietnamese culture is also the source of many problems on the art scene of Vietnam, namely, art frauds and the attitude towards it. Both the good and bad sides of the culture of Vietnamese art have emerged in a transition economy and created new problems along with the old ones. Vietnamese paintings might be popular in the international market at the moment, but the attraction would not be sustainable if the fraud-tolerant attitude of the Vietnamese art market persists. While many Vietnamese artists are advocating for improvement, many unethical behaviors that stained artistic dignity still go unpunished. The current situation of Vietnamese art presents the need for a reformation from a cultural level, for efforts to carry on the legacy of artists from the Indochina era, and to promote the Vietnamese artistic identity to the world.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.-H.V.; Writing-Original Draft Preparation, M.-T.H. (Manh-Toan Ho); Writing-Review & Editing, M.-T.H. (Manh-Toan Ho), M.-T.H. (Manh-Tung Ho), T.-T.V., Hong-Kong To Nguyen, and K.T.; Supervision, Q.-H.V.; Project Administration, Q.-H.V. and M.-T.H. (Manh-Toan Ho).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. 35 Cases of Art Fraud in Vietnam

PDF File (deposited at OSF; DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/R572M).

Appendix B. Case 2—Nguyen Ro Hung’s Copied Painting with Pham An Hai’s Signature 1

Figure A1.

Nguyen Ro Hung’s copied painting with Pham An Hai’s signature 1. The image was sourced from Tuoi Tre Newspaper (Viet 2017).

Figure A2.

Nguyen Ro Hung original painting 1. The image was sourced from Tuoi Tre Newspaper (Viet 2017).

Appendix C. Case 3—Nguyen Ro Hung’s Copied Painting with Pham An Hai’s Signature 2

Figure A3.

Nguyen Ro Hung’s copied painting with Pham An Hai’s signature 2. The image was sourced from Tuoi Tre Newspaper (Viet 2017).

Figure A4.

Nguyen Ro Hung’s copied painting with Pham An Hai’s signature 2. The image was sourced from Tuoi Tre Newspaper (Viet 2017).

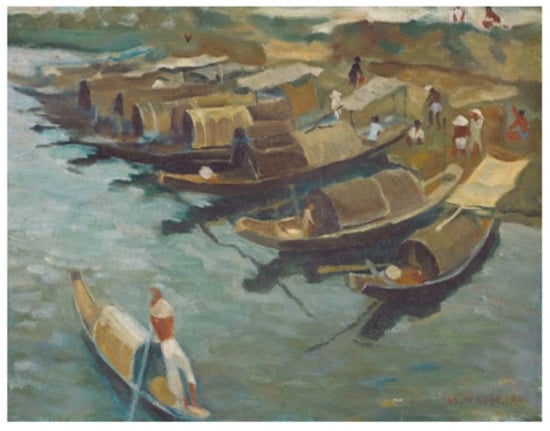

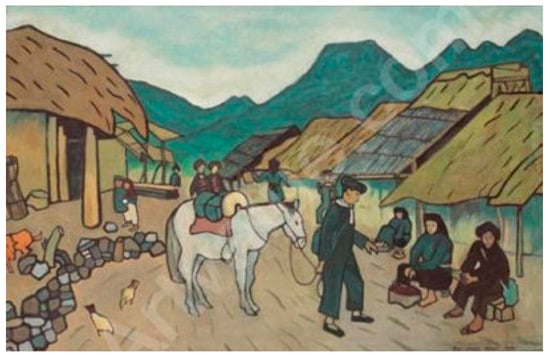

Appendix D. Case 6—Thuyen tren song Huong (Boats on the Perfume River)—To Ngoc Van. Auctioned at Christie’s, May 2016

Figure A5.

The auctioned Thuyen tren song Huong—To Ngoc Van. Auctioned at Christie’s, May 2016. The image was sourced from website nghethuatxua.vn (Anthony 2016).

Figure A6.

The Thuyen tren song huong—To Ngoc Van hang at the Vietnam Museum of Fine Arts. The image was sourced from website nghethuatxua.vn (Anthony 2016).

Appendix E. Case 7—Lady of Hue—Le Van De. Auctioned at Christie’s, May 2016

Figure A7.

Lady of Hue—Le Van De. The image was sourced from Thanh Nien Newspaper (An 2016).

Appendix F. Case 9—Vu Xuan Chung Collection

Figure A8.

Paintings in Vu Xuan Chung’s collection. The images were sourced from Tuoi Tre Newspaper (Khoa 2016).

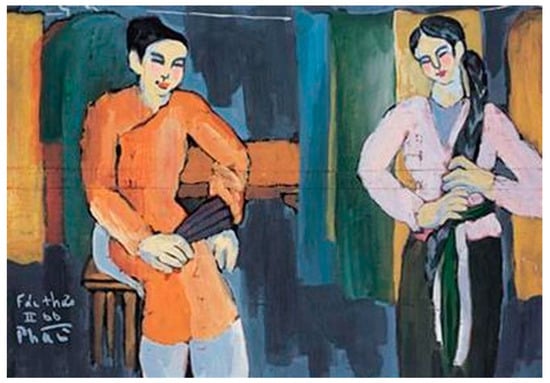

Appendix G. Case 11—Fac Thao (Opera Singers)—Bui Xuan Phai. Auctioned at Sotheby’s, October 2008

Figure A9.

Fac Thao—Bui Xuan Phai. Auctioned at Sotheby’s, October 2008. The images were sourced from Tien Phong Newspaper (Luong 2008).

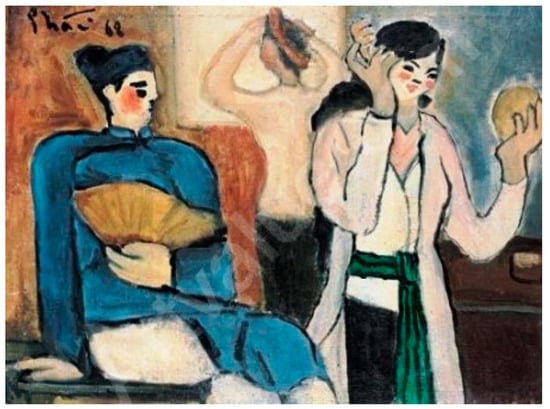

Appendix H. Case 12—Cheo Actor—Bui Xuan Phai. Auctioned at Sotheby’s, October 2008

Figure A10.

Cheo Actor—Bui Xuan Phai. Auctioned at Sotheby’s, October 2008. The image was sourced from Thanh Nien Newspaper (Nguyen 2016a).

Figure A11.

Where Cheo Actor supposedly copied from. The image was sourced from Thanh Nien Newspaper (Nguyen 2016a).

Appendix I. Case 13—Pho Cu (Street of the Past)—Bui Xuan Phai. Auctioned at Chon’s, July 2017

Figure A12.

Pho Cu—Bui Xuan Phai. Auctioned at Chon’s, July 2017. The images were sourced from Tien Phong Newspaper (Khanh 2017).

Appendix J. Case 14—Pho Co Ha Noi (Ha Noi’s Old Quarter)—Bui Xuan Phai. Philanthropy Auction, October 2016

Figure A13.

Pho Co Ha Noi—Bui Xuan Phai. Philanthropy auction, October 2016. The images were sourced from Tuoi Tre Newspaper (Thi 2016).

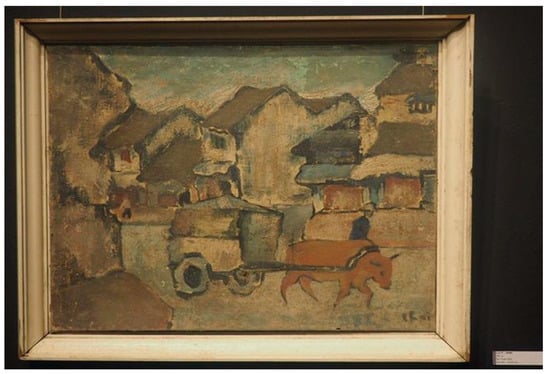

Appendix K. Case 16—Canh pho Nguyen Binh (Village)—Bui Xuan Phai. Auctioned at Sotheby’s, April 2008

Figure A14.

Canh pho Nguyen Binh—Bui Xuan Phai. Auctioned at Sotheby’s, April 2008. The images were sourced from Tuoi Tre Newspaper (Ly 2008).

Figure A15.

Canh pho Nguyen Binh—Bui Xuan Phai. Hang at Vietnam Fine Arts Museum. The images were sourced from Tuoi Tre Newspaper (Ly 2008).

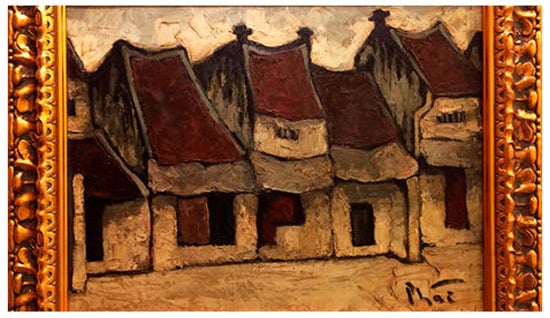

Appendix L. Case 17—Truoc gio bieu dien (Cheo Actors)—Bui Xuan Phai. Auctioned at Sotheby’s, April 2008

Figure A16.

Truoc gio bieu dien (Cheo Actors)—Bui Xuan Phai. Auctioned at Sotheby’s, April 2008. The images were sourced from Tuoi Tre Newspaper (Ly 2008).

Figure A17.

Truoc gio bieu dien (Cheo Actors)—Bui Xuan Phai. Hang at Vietnam Fine Arts Museum. The images were sourced from Tuoi Tre Newspaper (Ly 2008).

Appendix M. Case 19—Gia dinh (The Family)—Le Pho. Auctioned at Sotheby’s, September 2017

Figure A18.

Gia dinh—Le Pho. Auctioned at Sotheby’s, September 2017. The images were sourced from Tuoi Tre Newspaper (Thuy 2017).

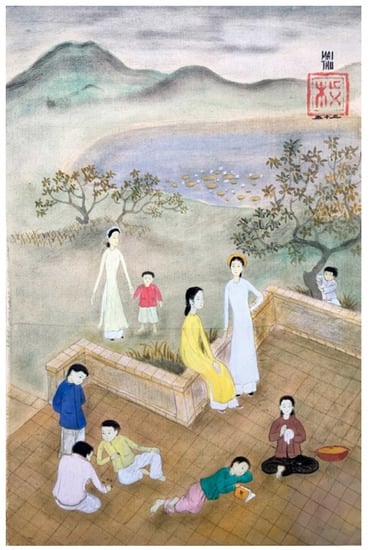

Appendix N. Case 22—Ra choi (La Recreation)—Mai Trung Thu. Auctioned at Auction.fr, May 2016

Figure A19.

Ra choi—Mai Trung Thu. Auctioned at Auction.fr, May 2016. The image was sourced from The Thao & Van Hoa Newspaper (Vu 2016).

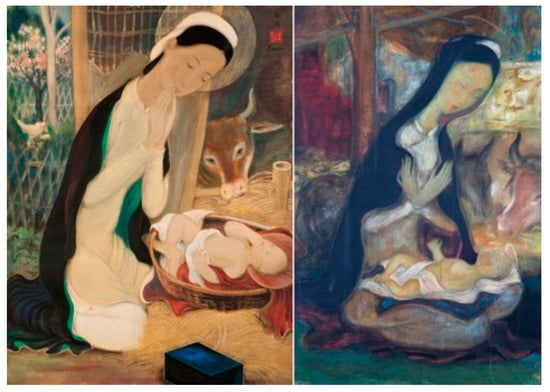

Appendix O. Case 24—Giang sinh (the Nativity)—Le Pho. Auctioned at Sotheby’s. April 2016

Figure A20.

Giang sinh—Le Pho. On the left auctioned at Christie’s, May 2011 and then November 2015. On the right auctioned at Sotheby’s, April 2016. The image was sourced from The Thao & Van Hoa Newspaper (Bay 2016a).

Appendix P. Case 25—Ong gia cong nhan (The Old Worker)—Van Tho. Hang at Gallery Viet Fine Arts

Figure A21.

Ong gia cong nhan—Van Tho. The image was sourced from Nhan Dan Newspaper (An 2011).

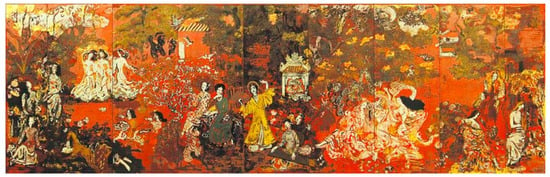

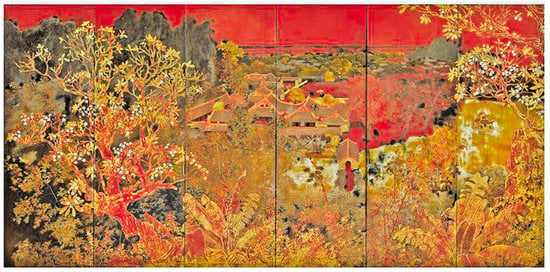

Appendix Q. Case 26—Trong vuon (In the Garden)—Nguyen Gia Tri. Auctioned at Larasati, July 2015

Figure A22.

Trong vuon—Nguyen Gia Tri. Auctioned at Larasati, July 2015. The image was sourced from website soi.today (Long 2015).

Figure A23.

Vuon xuan Bac Trung Nam (The Bac Trung Nam garden in spring)—Nguyen Gia Tri. Where the expert suspected the auctioned Trong vuon copied from. The image was sourced from website soi.today (Long 2015).

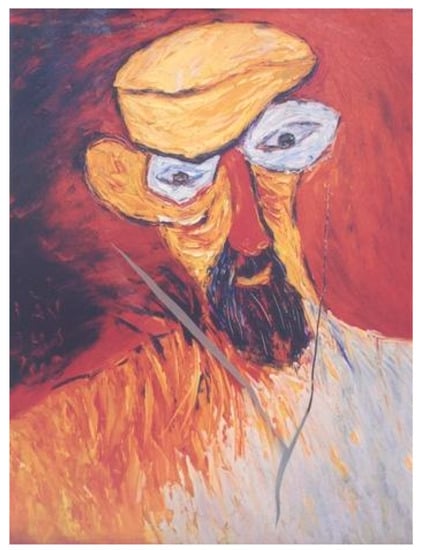

Appendix R. Case 27—Phong canh (Paysage)—Nguyen Gia Tri. Auctioned at Sotheby’s, September 2017

Figure A24.

Phong canh—Nguyen Gia Tri. Auctioned at Sotheby’s, September 2017. The image was sourced from Thanh Nien Newspaper (Nguyen 2017c).

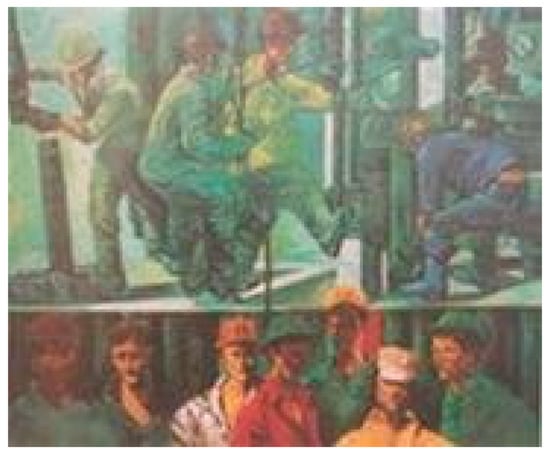

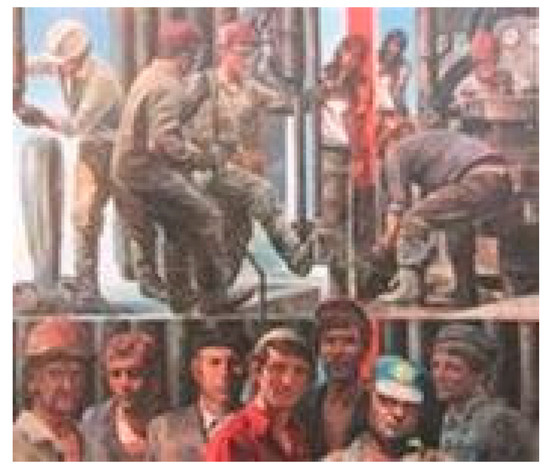

Appendix S. Case 29—Binh minh tren cong truong (Dawn on the Construction Site)—Luong Van Trung

Figure A25.

Binh minh tren cong truong—Luong Van Trung painted in 2005. The image was sourced from Tuoi Tre Newspaper (TuoiTre 2005).

Figure A26.

Brigada (The group of workers)—Cuznhexov painted in 1981. The image was sourced from Tuoi Tre Newspaper (TuoiTre 2005).

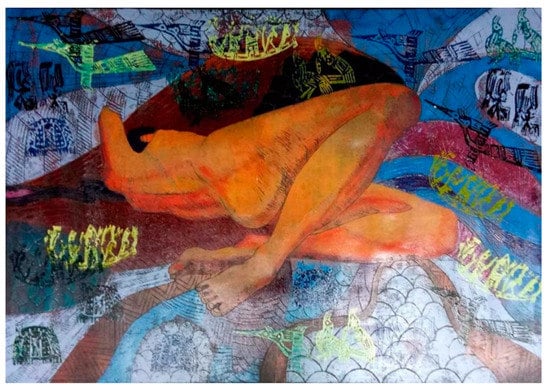

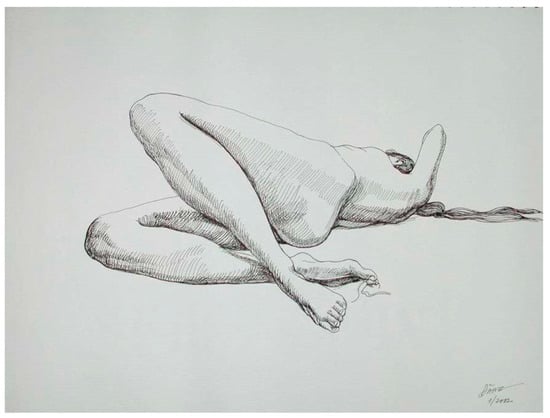

Appendix T. Case 30—Cau chuyen tram trung (Story of the Hundred Eggs)—Dam Van Tho

Figure A27.

Cau chuyen tram trung—Dam Van Tho painted in 2017. The image was sourced from Thanh Nien Newspaper (Nguyen 2017b).

Figure A28.

Khoa than 5 (Nude 5)—Nguyen Dinh Dang painted in 2002. The image was sourced from Thanh Nien Newspaper (Nguyen 2017b).

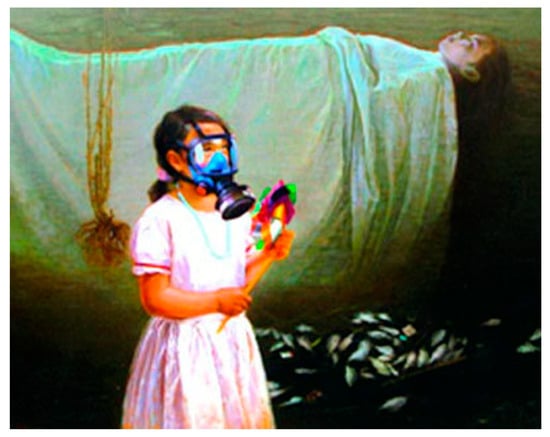

Appendix U. Case 31—Bien chet (Dead Sea)—Nguyen Nhan

Figure A29.

Bien chet—Nguyen Nhan painted in 2017. The image was sourced from VnExpress (Thanh 2017).

Figure A30.

The picture Dieu dung vi bien chet (Distress because of the dead sea)—the group of journalists PVT—Thanh Quang. Where the Bien chet plagiarized from. The image was sourced from VnExpress (Thanh 2017).

Figure A31.

The painting Song chet (The dead river)—Le The Anh. Where the Bien chet plagiarized from. The image was sourced from VnExpress (Thanh 2017).

References

- Alder, Christine, and Kenneth Polk. 2007. Crime in the World of Art. In International Handbook of White-Collar and Corporate Crime. Edited by Henry N. Pontell and Gilbert Geis. Boston: Springer, pp. 347–57. [Google Scholar]

- Alder, Christine, Duncan Chappell, and Kenneth Polk. 2011. Frauds and Fakes in the Australian Aboriginal Art Market. Crime, Law and Social Change 56: 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Ngan. 2011. Phạt Gallery Bán Tranh Giả Của Hoạ Sĩ Văn Thơ: Đã Đúng Và Đủ Sức Răn Đe ? [Fined the Gallery Which Sold the Fake Painting of Van Tho: Is It Good Enough?]. Available online: http://nhandan.com.vn/vanhoa/item/15938102-.html (accessed on 30 May 2011).

- An, Ngoc. 2016. Tranh Đấu Giá Ở Hồng Kông Có ‘Phiên Bản’ Tại Vn [Auctioned Painting in Hong Kong Has Another “Version” in Vietnam]. Available online: https://thanhnien.vn/van-hoa/tranh-dau-gia-o-hong-kong-co-phien-ban-tai-vn-724236.html (accessed on 15 May 2016).

- Anh, Viet. 2016. Vietnamese Traditional Folk Painting and Its Preservation. Available online: http://vovworld.vn/en-US/sunday-show/vietnamese-traditional-folk-painting-and-its-preservation-478421.vov (accessed on 9 August 2016).

- Anthony, Nguyen. 2016. Vài Nhận Xét Về Bức Tranh “Thuyền Trên Sông Hương” Đấu Giá Trên Sàn Christie’s Ngày 10 Tháng 5 Năm 2016 [Discussions on the Painting “Boats on the Perfume River” Auctioned at Christie’s on May 10 2016]. Available online: http://nghethuatxua.com/vai-nhan-xet-ve-buc-tranh-thuyen-tren-song-huong-cua-hoa-si-to-ngoc-van/ (accessed on 25 May 2016).

- Ashworth, Peter, Madeleine Freewood, and Ranald Macdonald. 2003. The Student Lifeworld and the Meanings of Plagiarism. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology 34: 257–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bay, Van. 2016a. Buồn Trông Tranh Giả Việt Nam [Witnessing Fake Vietnamese Painting in Sadness]. Available online: https://thethaovanhoa.vn/van-hoa-giai-tri/buon-trong-tranh-gia-viet-nam-n20160511151442732.htm (accessed on 21 May 2016).

- Bay, Van. 2016b. Làm Giả Kiệt Tác Của Danh Họa Vũ Cao Đàm Để Bán Đấu Giá Tại Pháp? [Faking Vu Cao Dam’s Masterpiece to Auction in France?]. Available online: https://thethaovanhoa.vn/van-hoa-giai-tri/lam-gia-kiet-tac-cua-danh-hoa-vu-cao-dam-de-ban-dau-gia-tai-phap-n20160504201009284.htm (accessed on 30 May 2016).

- Bay, Van. 2016c. Tiếp Theo Vụ Lùm Xùm Tranh Giả—Tranh Nhái: Đã Đến Lúc Để Bảo Tàng Đưa Ra Kết Luận [Following the Fake Paintings Incident: It Is Time for the Museum to Draw a Conclusion]. Available online: https://thethaovanhoa.vn/van-hoa-giai-tri/tiep-theo-vu-lum-xum-tranh-gia-tranh-nhai-da-den-luc-de-bao-tang-dua-ra-ket-luan-n20160720060204053.htm (accessed on 15 May 2016).

- Bay, Van. 2017. Sốc: Tranh Lê Phổ Đã Vượt Ngưỡng 1 Triệu Usd [Shock: Le Pho’s Painting Passed a Million-Dollar Mark]. Available online: https://thethaovanhoa.vn/van-hoa-giai-tri/soc-tranh-le-pho-da-vuot-nguong-1-trieu-usd-n20170402231033655.htm (accessed on 30 April 2017).

- Benhamou, Françoise, and Victor Ginsburgh. 2002. Is There a Market for Copies? The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 32: 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocart, Fabian, and Kim Oosterlinck. 2011. Discoveries of Fakes: Their Impact on the Art Market. Economics Letters 113: 124–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Rachel J. 2009. Art as a Financial Investment. In Collectible Investments for the High Net Worth Investor. Edited by Stephen Satchell. Oxford: Elsevier, pp. 119–50. [Google Scholar]

- Camus, Albert. 2005. The Myth of Sisyphus. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Charney, Noah, ed. 2016. Art Crime: Terrorists, Tomb Raiders, Forgers and Thieves. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Conklin, John. 1994. Art Crime. Westport: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- David, Géraldine, Kim Oosterlinck, and Ariane Szafarz. 2013. Art Market Inefficiency. Economics Letters 121: 23–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, Gregory. 2014. Explaining the Art Market’s Thefts, Frauds, and Forgeries (and Why the Art Market Does Not Seem to Care). Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Technology Law 16: 457–95. [Google Scholar]

- Diep, Ngoc. 2017a. An Lạc Trắng Trợn Đạo Khắc Gỗ a Di Đà Phật [an Lac Shamelessly Plagiarized a Di Da Phat]. Available online: https://tuoitre.vn/an-lac-trang-tron-dao-khac-go-a-di-da-phat-20170905112854264.htm (accessed on 25 May 2017).

- Diep, Ngoc. 2017b. Nghi Vấn Đấu Giá Tranh Giả, Mạo Danh Tô Ngọc Vân: Xâm Phạm Đến ‘Bàn Thờ’ Của Mỹ Thuật Việt Nam! [Suspicion on Auctioning a Fake, Impersonated Tô Ngọc Vân’s Painting: Insulting the Vietnamese Fine Arts’ Symbolic Artist!]. Available online: https://thethaovanhoa.vn/van-hoa-giai-tri/nghi-van-dau-gia-tranh-gia-mao-danh-to-ngoc-van-xam-pham-den-ban-tho-cua-my-thuat-viet-nam-n20170608070455297.htm (accessed on 3 May 2017).

- Do Ba, Khang, Khai Do Ba, Quoc Dung Lam, Dao Thanh Binh An Le, Phuong Lien Nguyen, Phuong Quynh Nguyen, and Quoc Loc Pham. 2017. Student Plagiarism in Higher Education in Vietnam: An Empirical Study. Higher Education Research & Development 36: 934–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durney, Mark, and Blythe Proux. 2011. Art Crime: A Brief Introduction. Crime, Law and Social Change 56: 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, Gareth. 2017. Theft, Fakes and Forgery...Understanding Art Crime in a Global Art Market. Available online: https://www.sothebysinstitute.com/news-and-events/news/understanding-art-crime-in-a-global-art-market/ (accessed on 28 August 2017).

- Gérard-Varet, Louis-André. 1995. On Pricing the Priceless: Comments on the Economics of the Visual Art Market. European Economic Review 39: 509–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granzow, Swenja. n.d. Finding Peace through Painting War? American and Vietnamese Art Depicting the Vietnam War. Available online: https://www.svsu.edu/media/writingcenter/Granzow_article.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2017).

- Grasset, Constance Dedieu. 1998. Fakes and Forgeries. Curator: The Museum Journal 41: 265–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Nhu. 2017. Tranh Việt: Thị Trường Ngầm Triệu Đô [Vietnamese Painting: A Million-Dollar Black Market]. Available online: http://phunuonline.com.vn/van-hoa-giai-tri/tranh-viet-thi-truong-ngam-trieu-do-101936/ (accessed on 1 May 2017).

- Han, Byung-Chul. 2018. The Copy Is the Original. Available online: https://aeon.co/essays/why-in-china-and-japan-a-copy-is-just-as-good-as-an-original (accessed on 4 May 2018).

- Hien, Doan Thu. 2016. Tranh Việt—Chơi Và Ngẫm [Vietnamese Painting—Play and Think]. Available online: http://enternews.vn/tranh-viet-choi-va-ngam-102393.html (accessed on 1 May 2016).

- Hieu, Trung. 2008. Keeping an Ancient Art Form Alive. Available online: https://vietnamnews.vn/life-style/179975/keeping-an-ancient-art-form-alive.html#OUeOQOrIsOk8hWsr.97 (accessed on 8 August 2008).

- Hill, Charles. 2008. Art Crime and the Wealth of Nations. Journal of Financial Crime 15: 444–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoa, Hien. 2016. Nạn Tranh Giả Ở Vn—Kỳ 3: Không Rõ Thì Đừng Mua [the Problem of Fake Painting in Viet Nam: Not Sure, Do Not Buy]. Available online: https://cvdvn.net/2017/08/15/nan-tranh-gia-o-vn-4-ky/ (accessed on 13 August 2016).

- Horvitz, Jeffrey E. 2009. An Overview of the Art Market. In Collectible Investments for the High Net Worth Investor. Edited by Stephen Satchell. Oxford: Elsevier, pp. 85–117. [Google Scholar]

- Huong, Hoai. 2016. Tranh Thật Hay Tranh Giả Chỉ Là Cảm Tính? [Fake or Authentic Painting Is Just Feeling]. Available online: https://vov.vn/blog/tranh-that-hay-tranh-gia-chi-la-cam-tinh-529632.vov (accessed on 30 May 2016).

- James, Marianne. 2000. Art Crime. Territory: Australian Institute of Criminology. [Google Scholar]

- Khanh, Nguyen. 2017. Lo ‘Phố Cũ’ Của Bùi Xuân Phái Là Giả [Worrying Bui Xuan Phai’s Pho Cu Is Fake]. Available online: https://www.tienphong.vn/van-nghe/lo-pho-cu-cua-bui-xuan-phai-la-gia-1170013.tpo (accessed on 30 May 2017).

- Khoa, Huu. 2016. Xem 17 Bức Tranh Gây Tranh Cãi Thật, Giả [17 Controversial Paintings]. Available online: https://tuoitre.vn/xem-17-buc-tranh-dang-gay-tranh-cai-ve-gia-that-1137448.htm (accessed on 25 May 2016).

- Kraeussl, Roman, and Robin Logher. 2010. Emerging Art Markets. Emerging Markets Review 11: 301–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraevskaia, Natalia. 2009. Collectivism and Individualism in Society and Art after Doi Moi. In Essays on Modern and Contemporary Vietnamese Art. Edited by Nhu Huy Nguyen and Sarah Lee. Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, pp. 103–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kräussl, Roman, Thorsten Lehnert, and Nicolas Martelin. 2016. Is There a Bubble in the Art Market? Journal of Empirical Finance 35: 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, Bobbie. 2001. Romance with Vietnam Contemporary Vietnamese Art and Some of Its Most Talented Creators Are the Newest Collecting Trend. Art and Antiques 24: 67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, Sidney. 2018. Chinese Art Professor Sacked after Award-Winning Poster Series Found to Be Plagiarised. Available online: http://www.scmp.com/news/china/society/article/2143909/chinese-art-professor-sacked-after-award-winning-poster-series (accessed on 4 May 2018).

- Long, Pham. 2015. Tranh Nguyễn Gia Trí Giả: Quá Đắt! Tranh Nguyễn Gia Trí Thật: Quá Rẻ! [Fake Nguyen Gia Tri’s Paiting: Too Expensive! Real Nguyen Gia Tri’s Painting: Too Cheap!]. Available online: http://soi.today/?p=183838 (accessed on 30 May 2015).

- Luong, Ngoc. 2008. Con Trai Bùi Xuân Phái Muốn Kiện Sotheby’s [Bui Xuan Phai’s Son Wants to Sue Sotheby’s]. Available online: https://www.tienphong.vn/van-nghe/con-trai-bui-xuan-phai-muon-kien-sothebysnbspnbsp-139318.tpo (accessed on 29 May 2008).

- Ly, U. 2008. Tìm Thấy Bằng Chứng Tranh Giả Bùi Xuân Phái [Found Evidence to Prove Some Bui Xuan Phai’s Paintings Are Fake]. Available online: https://tuoitre.vn/tim-thay-bang-chung-tranh-gia-bui-xuan-phai-284935.htm (accessed on 30 May 2008).

- Minh, Thi. 2017. Mở Cửa Thị Trường Tranh Việt Nam Thế Nào? [How to Open Vietnamese Art Market?]. Available online: https://nhatbaovanhoa.com/a5429/thi-truong-tranh-viet-nam-nhu-the-nao- (accessed on 1 May 2017).

- Myers, Fred R. 2002. Painting Culture: The Making of an Aboriginal High Art. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Napier, Nancy K., and Quan Hoang Vuong. 2013. What We See, Why We Worry, Why We Hope: Vietnam Going Forward. Boise: Boise State University CCI Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, Lucy. 2016a. Có Hay Không Đường Dây Rửa Tranh Ra Nước Ngoài? [Is It a System of Vietnamese Painting Laundering?]. Available online: https://thanhnien.vn/van-hoa/co-hay-khong-duong-day-rua-tranh-ra-nuoc-ngoai-727055.html (accessed on 29 May 2016).

- Nguyen, Lucy. 2016b. Họa Sĩ Thành Chương Tung Phác Thảo Chứng Minh Bức ‘Trừu Tượng’ Của Mình [Thanh Chuong Showed a Draft to Prove the ‘Abstract’ Painting Is His]. Available online: https://thanhnien.vn/van-hoa/hoa-si-thanh-chuong-tung-phac-thao-chung-minh-buc-truu-tuong-cua-minh-724105.html (accessed on 3 May 2016).

- Nguyen, Lucy. 2017a. Lập Lờ Đạo Tranh Và ‘Remake’ Tranh [Confusion between Plagiarism and ‘Remake’ Paintings]. Available online: https://thanhnien.vn/van-hoa/lap-lo-dao-tranh-va-remake-tranh-875363.html (accessed on 3 May 2017).

- Nguyen, Lucy. 2017b. Nạn Đạo Ý Tưởng Trong Mỹ Thuật Việt [the Problem of Copying Idea in Vietnamese Art]. Available online: https://thanhnien.vn/van-hoa/nan-dao-y-tuong-trong-my-thuat-viet-872694.html (accessed on 21 May 2017).

- Nguyen, Lucy. 2017c. Tranh Việt Đấu Giá Tại Sotheby’s Tiếp Tục Gây Tranh Cãi [Vietnamese Painting Auctioned at Sotheby’s Continued Raising Controversy]. Available online: https://thanhnien.vn/van-hoa/tranh-viet-dau-gia-tai-sothebys-tiep-tuc-gay-tranh-cai-881074.html (accessed on 30 May 2017).

- NLH. 2014. “Thiếu Nữ Bên Hoa Huệ”—Kiệt Tác Hội Họa Việt Nam Đang Ở Đâu? [“Thieu Nu Ben Hoa Hue”—Where Is the Vietnamese Masterpiece?]. Available online: http://cinet.vn/my-thuat-nhiep-anh-trien-lam/thieu-nu-ben-hoa-hue-kiet-tac-hoi-hoa-viet-nam-dang-o-dau-313547.html (accessed on 1 May 2014).

- Paddock, Richard C. 2017. Vietnamese Art Has Never Been More Popular. But the Market Is Full of Fakes. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/11/arts/design/vietnamese-art-has-never-been-more-popular-but-the-market-is-full-of-fakes.html (accessed on 3 May 2017).

- Passas, Nikos, and Blythe Bowman Proulx. 2011. Overview of Crimes and Antiquities. In Crime in the Art and Antiquities World. Edited by Stefano Manacorda and Duncan Chappell. New York: Springer, pp. 51–67. [Google Scholar]

- Petterson, A., and O. Williams. 2009. Art Investing and Wealth Accumulation. In Collectible Investments for the High Net Worth Investor. Edited by Stephen Satchell. Oxford: Elsevier, pp. 151–74. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, Minh Chinh, and Quan Hoang Vuong. 2009. Kinh Tế Việt Nam: Thăng Trầm Và Đột Phá [Vietnam Economy: Ups and Downs, and Breakthrough]. Hanoi: Nha xuat ban tri thuc. [Google Scholar]

- Phuc, Dang Van. 2017. Thị Trường Tranh Nghệ Thuật Việt Nam Ở Đâu? [Where Does Vietnamese Art Market Open?]. Available online: http://dantri.com.vn/van-hoa/thi-truong-tranh-nghe-thuat-viet-nam-o-dau-20170719234339854.htm (accessed on 1 May 2017).

- Phuong, Mai. 2005. Rooster Woodprints Crow in the New Year. Available online: http://vietnamnews.vn/life-style/arts-craft/139951/rooster-woodprints-crow-in-the-new-year.html#ErWGd3aW8Hx4Tcf5.99 (accessed on 9 August 2005).

- Piano, Anthony J. Del. 1993. The Fine Art of Forgery, Theft, and Fraud: Corruption in the World of Art Antiquities. Criminal Justice 8: 16–57. [Google Scholar]

- Plattner, Stuart. 1996. High Art Down Home: An Economic Ethnography of a Local Art Market. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Prögler, Joseph. A. 1991. Choices in Editing Oral History: The Distillation of Dr. Hiller. The Oral History Review 19: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purtee, Melissa. 2016. How to Deal with Copyright, Plagiarism, and Original Ideas in Art Education. Available online: https://www.theartofed.com/2016/07/07/please-copy-copyright-plagiarism-original-ideas-art-education/ (accessed on 21 August 2016).

- PV. 2016. Họa Sĩ Thành Chương Mới Là Tác Giả Đích Thực Của Bức Tranh \’Trừu Tượng\’ [Thanh Chuong Is the Real Author of the Painting ‘Abstract’]. Available online: http://daidoanket.vn/van-hoa/hoa-si-thanh-chuong-moi-la-tac-gia-dich-thuc-cua-buc-tranh-truu-tuong-tintuc110466 (accessed on 3 May 2016).

- Quan, Nho. 2016. Họa Sĩ Buồn Lòng Nạn Tranh Giả Hoành Hành Ở Việt Nam [Vietnamese Artists Are Depressed Because of the Fake Art Problem in Vietnam]. Available online: https://tuoitre.vn/hoa-si-buon-long-nan-tranh-gia-hoanh-hanh-o-viet-nam-1142260.htm (accessed on 15 May 2016).

- Quoc, Le Minh. 2014. Người Đặt Nền Móng Cho Mỹ Thuật Hiện Đại Vn [the Person Who Set the Foundation for Vietnamese Modern Art]. Available online: https://thanhnien.vn/chinh-tri-xa-hoi/nguoi-viet-tai-tri/nguoi-dat-nen-mong-cho-my-thuat-hien-dai-vn-467602.html (accessed on 15 May 2014).

- Safford, Lisa Bixenstine. 2015. Art at the Crossroads: Lacquer Painting in French Vietnam. Transcultural Studies 1: 126–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, Ridley. 1982. Blade Runner. Burbank: Warner Bros. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Nora A. 1997. Orientalism/Occidentalism: The Founding of the Ecole Des Beaux-Arts D’indochine and the Politics of Painting in Colonial Việt Nam, 1925–1945. Crossroads: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 12: 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Nora A. 1999. ‘Pho’ Phai and Faux Phais: The Market for Fakes and the Appropriation of a Vietnamese National Symbol. Ethnos 64: 232–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]