Abstract

Historiography and archaeological research have traditionally defined mosques mainly as religious spaces or places to pray, without further specifications. This simplification has usually dominated the analyses of mosques, while other uses or functional aspects of these buildings were put aside. The scarcity of material information available for years to approach these buildings, together with the dominance of the more monumental examples—such as the great mosque of Córdoba—provoked that analyses about other more modest mosques were scarce or almost inexistent. However, in recent decades, the proliferation of real estate building activities has led to the recovery of many new and fresh archaeological data related to other mosques different from the Friday ones. Specifically, in Córdoba, the volume of information recovered has been enormous, and concerns not only mosques as isolated buildings, but also their urban environments, construction processes, and evolution along the centuries. Therefore, in this paper, we offer a summarized overview of the state of the arts about research on mosques in al-Andalus, presenting the main problems and limitations of the topic until now, and also the case of Córdoba and the main results achieved there as a reference for further actions to be undertaken in the rest of the territory.

1. Introduction: Mosques, Beyond Religion

Religion is one of the main modelers of Islamic civilization and Muslim lifestyles. The need to perform daily prayers explains why mosques, as hearts of the quotidian religious activity, are usually preeminent elements in the arrangement of settlements and cities. Not only were they the place for the congregation of believers, but also means of monumental display for the benefit of ruling authorities. Together with this, the non-confessional use that they received from the inhabitants also constituted an important part for their raison d’être.

Such a concurrence of factors has been frequently derived in the affirmation that there is no Islamic city without mosques. However, whereas the notion of an ‘Islamic city’ has been rethought and reformulated in recent decades (see, for instance, Abu Lughod 1987; Behrens-Abouseif 2000; Neglia 2008; or Brogiolo 2011), the term ‘mosque’ has remained unreviewed. Mudun are no longer conceived as non-planned sites, produced by a chaotic society, but as organic living realities that change according to the needs and ways of life of those who inhabit and build them. In other words, the Muslim city is not defined through its morphological characteristics any more, but through the functions it performs along time.

In stark contrast, mosques have barely been explained beyond their formal aspects. This is quite contradictory, given that the Quran refers to a ‘mosque’ as the place for prayer for the Islamic community, without stipulating specific architectural characteristics apart from the orientation towards Mecca (The Quran, II, 144–150; Grabar 1979, p. 119). In fact, from the very beginning of the Islamic expansion, the architectural forms of these buildings were multiplied according to diverse building traditions and to the personalities of the different regions. Because of this formal variety, there have been several intents to classify existing mosques in certain typological groups.

One classification is suggested in The Encyclopedia of the Quran, where mosques are arranged according to their morphological characteristics and geographical locations.1 The Encyclopedia of Islam also systematizes mosques, but considers the reasons that promoted their foundation.2 All of these criteria allow a primary organization of mosques despite their strong architectural plurality, but this current overview is insufficient to understand all their functions in urban scenarios or in Muslim ideology.3 The panorama becomes more complex when it comes to the explanation of what a mosque is beyond its material form. The Encyclopedia of Islam (Bosworth 2010) defines “mosque” as the place where Muslims prostrate during the religious service. This comes from the etymological origin of the word mosque— in Arabic masŷid or masgid, plural masāŷid—which derives from the verb sadjada, that is to say, to prostrate. Thus, ‘mosque’ alludes to the ritual followed by the faithful when they perform the prayer: standing in parallel rows, believers execute a series of positions that culminate in the total prostration as a symbol of submission to Allah. This explanation4 is mainly focusing on the religious facet of mosques and defining them as a place for worship, but disregards many others aspects. It has been also stated that at least at the beginning of the Islamic conquest mosques were built as territorial landmarks as well, located in strategic spots where they could show the presence of the Islam in the conquered lands (Calvo 2014, p. 28). Mosques were designed to represent and maintain the memory of certain historical episodes or people too, and they were sometimes linked to the policies of Arabization and Islamization of the new territories (Calvo 2014, p. 41).

Together with this, at least during the medieval centuries, rulers used masāŷid as propagandistic scenarios to launch certain messages. These large architectural works served to establish signs of political legitimacy too, through carefully designed architectural and decorative programs. First in the Syrian area, the appearance of mosques was progressively regularized through a “direct imperial patronage” (Ettinghausen and Grabar 1987, p. 54). Later, similar processes will be undertaken in al-Andalus (Almagro 2001; Juez 1999, pp. 86–ff.). In this region, the great mosque of Córdoba is considered the best example of monumental religious architecture to the service of political legitimization and propaganda.

Apart from these official intentions, mosques were also modeled by the normal and daily use that the inhabitants of the cities gave to them. Regarding this, it is well documented that, at least in al-Andalus, the attendance of Muslims to mosques was not only to perform the daily prayers there, but also to solve other issues, such as those related to justice or neighborhood conflicts (see Juez 1999, pp. 116–17; Peláez 2000; Al-Jusani 2005). This social interaction turned mosques into a stage in which the pretensions of the power and the habits of the daily life concurred.

2. Masāŷid in Al-Andalus: Friday Mosques and Other Examples

The Encyclopedia of Islam points out that mosques which housed the noon Friday prayer could receive the rank of major or “Friday mosques” (Bosworth 2010, pp. 325–26). Conversely to daily prayers, which could be practiced almost anywhere (Hillenbrand 1994, p. 31), Friday prayer in the mosque was of compulsory assistance for all adult male belonging to highest classes. It was not only a religious duty, but an official instrument through which inhabitants expressed their community membership and their adhesion and support to certain political regimes. This is the reason why many main mosques became a clear sign of the authority and position of the ruling dynasty. In the case of al-Andalus, the Umayyads were the first encouragers of the Islamic faith. Since they also had the need to legitimate their commanding position and to manifest their building capacity, they became the highest promoters of these masāŷid al-Jami’(Juez 1999, p. 86).5 In these buildings, they could arrange official and political ceremonies, as well as to check adhesion of the umma to the regime (see Juez 1999; Calvo 2014, pp. 62–ff.). As a consequence, these facilities showed great monumentality and artistic quality which were interpreted by the believers as the material expression of the unity of the community, and by the non-believers as a manifest sign of the hegemony of Islam.

Their eye-catching and attractive formal characteristics turned mosques, in the opinion of P. Wheatley and especially between the 7th and 10th centuries, into the most striking structures on the Islamic cities6 (Wheatley 2001, p. 231). Because of this, Friday mosques in urban areas have usually received the most of the attention in research, which has tended to leave other minor prayer spaces aside. However, those monumental features are not perceptible in all andalusí cases nowadays, often due to the frequent transformation of mosques into later churches. The case of Jaén may be very illustrative. Only after a hard architectural study in the current Iglesia de la Magdalena it was possible to recognize the Islamic mosque that remains underneath (first Berges (2007), recently reviewed by Rütenik (2017, pp. 249–57). In some other cities, basic data such as the location and fundamental structure of the main mosque are still being the subject of scientific discussion (in Granada, for example, (Torres Balbás 1945; Fernández Puertas 2004); or Toledo, where only the location of its main mosque is barely known).

In the cases mentioned above, readjustments to the Christian cult and the continued use produced strong modifications in the original structures of these buildings, which are nowadays difficult to perceive. Nevertheless, in some other cases several fundamental traces can be still identified in spite of the Christian modifications. At this respect, the Friday mosque of Zaragoza, currently called Seo de San Salvador, is a highlighted example. For a long time, the mosque was only approachable through written information, and barely recognized in some reused structures, such as its minaret (Souto 1989; Almagro 1993). However, the use of techniques related to the archaeology of architecture has led to the documentation of other archaeological traces, allowing a more complete formal and typological knowledge of the old mosque (Souto 1993a, 1993b; Hernández Vera 2004).

Similar situations can be observed in Huesca (Carrero 2005); Tudela (Gómez Moreno 1945), Málaga (González Sánchez 1996), Mértola (Torres Balbás 1955; Ewert 1973; Macías 2006; Macías et al. 2011), Carmona (Anglada et al. 2017; Jiménez Hernández 2018) or Sevilla see (Valor 1993) or (Cómez 1994) for the Ibn Adabbas mosque, (Jiménez Sancho 2016) for the Almohad mosque), where Friday mosques are progressively being discovered or better documented. In addition, in this last city the Almohad mosque has been addressed from new viewpoints, in regard to its urban insertion and its impact in the nearest urban fabric (Almagro 2007; Arévalo 2011; Jiménez Sancho 2016).7

The variability in the better or worse knowledge of andalusí Friday mosques becomes clearer when it comes to the great mosque of Córdoba. This complex is considered by many scholars the most emblematic building of those erected in al-Andalus due to its forms, functions and meanings (Souto 2009, p. 9). Its significance, together with its state of conservation, has produced great fascination among researchers and other authors, who have widely written about it. As a consequence, Córdoba’s mosque has received plenty of attention, materialized in a wide range of existing bibliography of different nature.8

While research has been traditionally concentrating more on these principal mosques, for which there is a considerable amount of literature available, less monumental ones have barely appeared in the scientific discussion. Recent historiography has popularized the names ‘neighborhood’, ‘secondary’, or ‘minor’ mosques for these oratories, which were built all along the cities and which do not seem to fit properly in the typologies provided by the Encyclopedia of Islam (see above).

Written sources transmit first order information about the juridical and legal details of these foundations—internal maintenance, methods of financing, and economic sustainability, among other aspects—can be studied through the documents related to awqāf. The works by A. García Sanjuán (2002) and A. Carballeira (2002) have shed new light on this pious institution, and on how these foundations were engaged with the social life of cities’ inhabitants. In this respect, texts reveal how these smaller mosques were places for justice, social gathering, teaching, for hosting different social ceremonies and, even in certain cases, scenarios for funerary activities as well (see some examples in González Gutiérrez 2016a, pp. 419–ff.).

Unfortunately, these textual data are too undetailed to allow approaches to the formal aspect and the functions performed by these buildings. Written sources rarely transmit enough information about the appearance of these buildings, but only bare mentions, without descriptions, related to further narration or other events. In the best of the cases, some inaccurate counts have been made.9 Texts’ inaccuracy turns archaeological information into an indispensable source to reach a better knowledge about mosques. Nevertheless, archaeological data may also be hard to process frequently due to insufficient registration, the poor state of conservation of the remains found, or the difficulties to identify them as mosques. Because of this, in the former urban territory of al-Andalus there are still many mosques to be detected.

Regarding Seville, for instance, it has been conventionally assumed that medieval mosques played a very important role in the arrangement of the later Christian parish districts in the city, even though there is very little archaeological news of other Islamic religious buildings rather than the principal mosques (Valor 2008). Difficulties when it comes to the identification of mosques—which is not exclusive for the Sevillian area—are too often related to their almost total remodeling after the Castilian conquest, and to the scarcity of adequate urban archaeological interventions to document them. The frequent lack of publications derived from the few interventions made should be added to this problem (Valor 2008, pp. 142–45).

Jerez de la Frontera may be taken as another example. Christian sources written after the Conquest register the existence of 18 mosques in the city—some of them turned into parish churches—not registered by archaeology until now (Calvo 2014, pp. 308–9)10. Some minor mosques have been located in former cities, currently abandoned, such as in Madīnat al-Zahrā’ (Vallejo 2009) or in Vascos, Toledo (Izquierdo and Prieto 1993–1994). There is also evidence of other religious spaces different from Friday mosques located in citadels or palaces, instead of in neighborhoods. These are the cases of the small mosques excavated in the citadels of Vascos (Izquierdo and Prieto 1993–1994; Izquierdo 1990; Izquierdo and Ares 2004), Murcia (Sánchez and García 2007), Badajoz (Valdés 1999), the Aljafería palace in Zaragoza (Borrás and Cabañero 2012; Cabañero 2007), and probably in the citadel of Merida as well (Féijoo and Alba 2002),11 among others (Calvo 2014, pp. 445–ff.). These locations point towards a private or restricted use of these spaces by specific collectives rather than by the majority of the population, and it is also confirming the existence of places for prayer different from Friday mosques or from neighborhood mosques. The clearest example may be the renowned Cristo de la Luz mosque at Toledo (Calvo 1999; Jurado Jiménez 2000; or Romero 2006). Even though it was not strictly located at the Alcázar enclosure, its constructive characteristics point towards a possible private use as well.

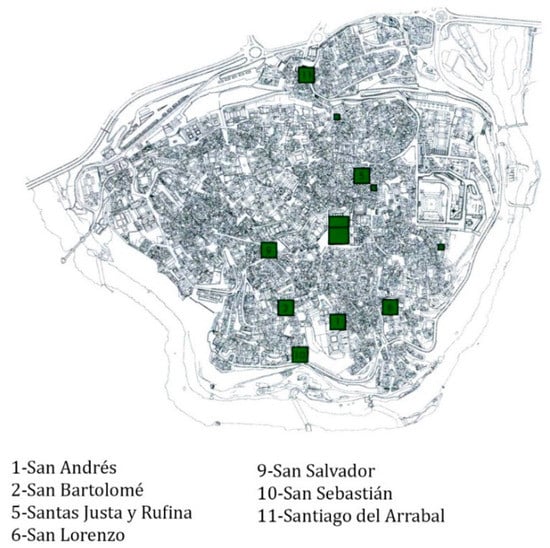

This infrequent discovery of other smaller mosques in al-Andalus urban areas has, fortunately, two very important counterpoints. The first of them is Toledo, where many smaller places of prayer have been identified so far, exhaustively compiled by A. Romero (2006). In addition, the application of innovative techniques when analyzing these buildings’ elevations is leading to suggest diachronic readings of their evolution and, in many cases, subsequent conversion into churches. The main example in this regard is the work of T. Rütenik (2008, 2017), who has raised the number of mosques documented in the city to almost a dozen (see Figure 1).12

Figure 1.

Plan of Toledo with the location of mosques identified in current churches (Used by permission of T. Rütenik, with modifications. The original can be found at Rütenik 2008, p. 30).

The second one is Córdoba, where, from the end of the 20th century, urban archeology is revealing numerous archaeological remains of former secondary mosques, inserted into very wealthy urban contexts.

3. The Case Study of Córdoba: Secondary Mosques for Al-Andalus

Major archaeological evidence about neighborhood mosques in Córdoba did not arise until the end of the 1990s. However, and despite the vast shadow casted by the Friday mosque, from the beginning of that same century some researchers began to raise questions about the possible presence of other simpler mosques in the landscape of the city. We are referring to authors such as R. Castejón (1929) or E. Lévi-Provençal (1932, etcetera), who aimed to recreate the image of the caliphal city in the 10th century. To do so, they combined the information contained in written sources with the observation of the heritage remains preserved in the present city.13 Approaches to the surviving Islamic remains were scarce but of great value. Among them, we should highlight the efforts made by V. Escribano (1964–1965), B. Pavón (1976), L. Golvin (1979) and, most of all, F. Hernández (1975), who intended to approach the basic structure and organization of former mosques. Hernández also tried to distinguish different minaret typologies, which led him to suggest a possible Cordobesian building school and style tendencies depending on chronological moments. However, further conclusions should wait, according to Hernández, pending further archaeological evidence.

This state of the arts had to wait until the second half of the 20th century and the first years of the 2000, when Córdoba experienced a rapid increase of real estate activities which provoked the progressive and quick exhumation of enormous areas of the Islamic city. These excavations, mainly developed in areas located outside the medieval walled enclosure, meant the discovery of archaeological evidence of great quantity and quality. Among others, multiple vestiges interpreted as the remains of mosques were uncovered, which were rapidly compiled into a specific article (López Guerrero and Valdivieso 2001)14 and progressively incorporated into the urban-diachronic and landscape studies of the Islamic city. Acién and Vallejo (1998), Murillo et al. (2004), Casal et al. (2006) or Vaquerizo and Murillo (2010) published works which rose awareness about these elements, often disregarded when speaking about the urbanism and landscape of Madinat Qurtuba.

The historiographical precedents and the availability of this new archaeological information motivated our study about secondary mosques in Islamic Córdoba. Our main aim was to try to give answer to a whole series of questions related to the appearance, function, and continuous evolution of the city: how were these mosques structured and organized, and why? What were the typologies? How did these mosques act in the Islamizing work promoted by the Umayyads? What urban and social transformations aroused in the neighborhoods in which they were founded? etcetera.15

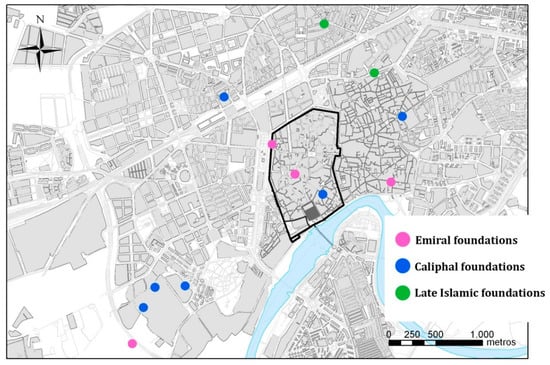

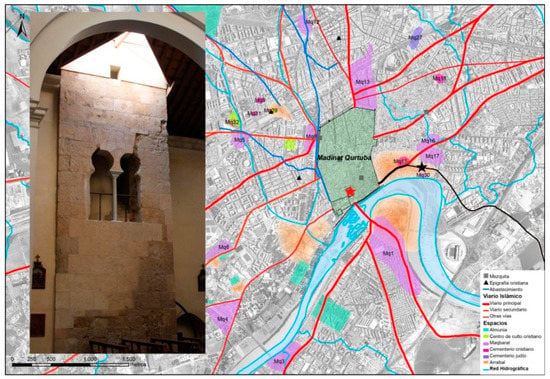

For achieving this, the study of these buildings per se was required first. This involved the identification of all the former mosques and the analysis of their structure and general arrangements, typologies, and layouts, and their chronological identification as well. Despite the number of mosques identified in Córdoba at present is lesser than the figures transmitted by written sources (see González Gutiérrez 2014, pp. 298–99), up to date scarcely a dozen of complexes have been identified as former secondary mosques (see Figure 2). Their states of documentation and conservation are, besides, quite uneven.

Figure 2.

Dispersion map of mosques documented in Córdoba through archaeological methodologies (Created by author).

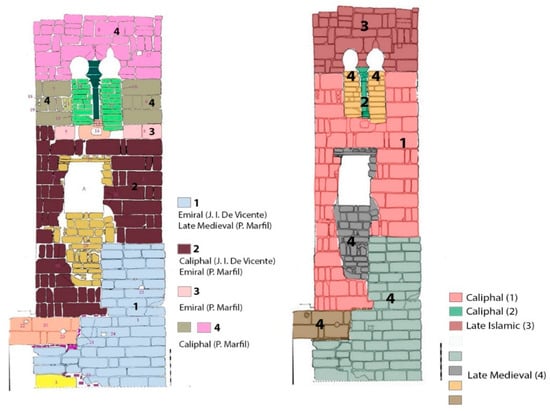

There are still standing remains of some of these mosques, specifically several minarets which were transformed into bell towers. Even though most of them have been recently restored and, therefore, the observation of the medieval Islamic techniques becomes hard, there are still some examples in which the traditional wall-reading techniques can be applied. It is the case of the minaret reused as bell tower in the church of San Lorenzo, whose chronological evolution has been reinterpreted through the architectural analysis of its visible faces (González Gutiérrez 2016a, pp. 293–96). Its possible foundational plaque states that the minaret was erected or refurbished in caliphal times, during the rule of al-Hakam II. Nevertheless, recent research has suggested a possible emiral origin of the tower (Marfil 2010, p. 54; De Vicente 2014, p. 27). Our revision on these readings, put in relation with other andalusí examples, has brought different results16 that are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Drawing of the southern face of San Lorenzo minaret (basis from Marfil 2010, p. 55, lám. 5, used with his permission. Colors are added by author according to the different interpretations given to the minaret). To the left side, interpretations by De Vicente (2014, p. 145) and Marfil (2010, p. 55). To the right side, author’s own interpretation.

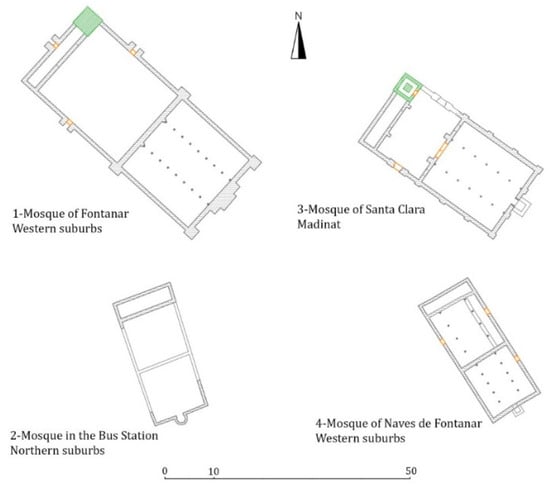

These analyses could be only applied in very specific cases, because usually mosques are documented just partially. There is also a very frequent lack of other architectural or ornamental material, as well as a shortage of accurate stratigraphic information in many cases. Given these conditions, an approach to their structure and architectural design should be made through new methodological techniques. We proposed a metrological and modulation study tested in four mosques documented in Córdoba (further methodology and results at (González Gutiérrez 2017)). Results obtained suggest the possible existence of a building scheme for caliphal mosques, which consisted of a squared prayer hall and a quadrangular patio on the west side, equal or slightly bigger than the haram’s square (see Figure 4). This type of masŷid roughly reproduces the scheme established by the Great Mosque during the Caliphate, which consists of two equal squares as well.

Figure 4.

Caliphal mosques in Córdoba. Their plant consists on a squared prayer room, followed by an also squared courtyard often provided with a minaret (Created by Author).

We have not managed to calculate overall proportions that determined the general dimensions chosen for each building. It is probable that the size of these mosques depended more on the conditions of the plots where they were erected. Given that three of the four mosques analyzed were caliphal, it has not been possible to suggest a wider chrono-typology beyond the limits of the caliphate. Thus, new archaeological evidence is required to complete our vision and clarify our hypotheses.

Although the Qu’ran, as we said at the introduction, does not dictate rules that determine the morphological appearance of masāŷid beyond their orientation towards Mecca, Cordobesian mosques soon defined their basic structure around two main parts. Both, prayer hall and courtyard, had apparently simple features, but they were also very easy to combine and model. They were, in short, highly elastic and plastic spaces that could be built almost anywhere. The type of caliphal oratory identified for Córdoba is flexible and its design could be changed according to the plots or spaces where the mosques would be built. This plasticity is not confined to Córdoba. In al-Andalus, many ‘transgressions’ of this common scheme are detected, probably favored by the absence of quranic guidelines. Thus, we have mosques whose mihrabs are not inserted in the center of the qiblas, as in the mosque of Córdoba, or the citadel of Badajoz; apparently random ground plans as the one drawn by the mosque in citadel of Vascos, or the generalized differential position of minarets. This adaptation ability also means that there were no strict buildings rules that can be extrapolated for all al-Andalus, and it is of paramount importance because it turned mosques into one of the most versatile and multifunctional buildings in the Islamic city.

Concerning their orientations, and despite being this the only characteristic imposed by the Quran, it has been revealed to be imprecise in all cases. Its accuracy, which is being subject of intense debate in historiography, did not seem to have capital relevance in Córdoba. Directions displayed by qiblas in Madinat Qurtuba were unrelated to their chronologies, situation repeated in the rest of al-Andalus; nor was a predominating trend over others. Our recent analyses, summarized in Table 1, suggest that the degree of accuracy of Cordobesian mosques’ orientation was more influenced by topography and by the inherited road networks (González Gutiérrez 2016a, pp. 454–ff.), as is the case in certain Moroccan cities (Bonine 1990).

Table 1.

Mosques documented in Córdoba: relation among their locations, chronologies and qibla orientations.

The deepening in the structural knowledge of Madīnat Qurṭuba’s masāŷid led to approach the forms and lifestyles of the society that used them, as well as to a better understanding of the associated urban phenomena. The interpretation of information contained in written sources in the light of archaeological data confirms the functional ambivalence of mosques. Far from being places exclusively dedicated to prayer and worship, several texts speak of other activities such as the administration of justice, the education in specific disciplines or the development of some commercial operations. All this turned them into true centers for social meeting. Their material relevance has been confirmed through their spatial analysis from a diachronic perspective. As we will see, mosques were generally located in close relation with historic paths, major roads and the gates of the city. Sometimes, their topographic prominence has also been verified.

Documentary sources register numerous mosques’ foundations during the Emirate. Promoted by the sovereign and his closest social circle, they played an important role in the emergence and development of the earliest neighborhoods.17 Archaeology has not been able to find all these examples, but has noted the existence of some whose location does not seem casual, but the result of a pre-planned project. We are referring to mosques close to the walled city’s gates, or placed on entity roads leading to it. They may respond to the Umayyad government’s desire to provide Madīnat Qurtuba with the needed infrastructure to develop very specific ways of life, and to create a determined landscape (González Gutiérrez 2016b, pp. 280–84). Perhaps the clearest example of the Islamization and proselytism policy developed by the Umayyad dynasty is the mosque of Santiago (see Figure 5). Probably built at the request of the emir Hišām I along a road with Roman origins, near the Bāb al-Ḥadīd, it was located in a neighborhood already populated during the Late Antiquity, very close to a dhimmi cemetery. Thus, its erection would have been conceived to encourage urban dynamics and Islamization in a vernacular area (González Gutiérrez 2016b, pp. 280–84).

Figure 5.

Location of the mosque currently visible in the church of Santiago (black star) in relation to the historical road (in black) and the Friday mosque (red star) (Created by author over the plan by Vaquerizo and Murillo 2010, p. 529, fig. 249. Used by their permission).

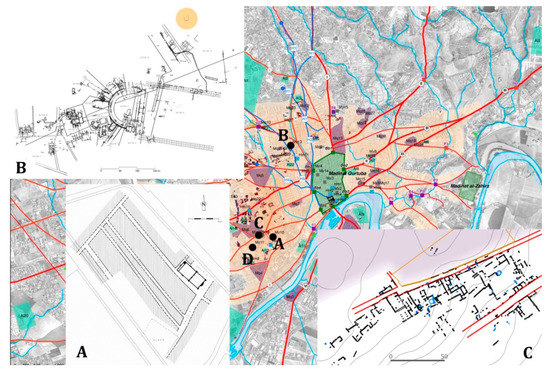

The cited patterns were respected during the Caliphate, in which mosques continued to occupy a prominent place in road networks and neighborhoods. The ultimate expression of the latter is documented in the western suburbs. Here, there were mosques built before the rest of the infrastructure, as it is the case of the mosque in Fontanar (see Figure 6a). Placed at the confluence of the neighborhood’s main streets, this area probably experienced dense traffic of people and activities. Next to it, another masŷid was built in the most topographically prominent spot of the suburb (mosque in the Centro de Transfusión, see Figure 6d, (Sánchez Madrid 2005)). In addition, some sectors already emerged during the Emirate will be now provided with new infrastructure, among which mosques can be detected (mosque of Naves de Fontanar, see Figure 6c). Emiral mosques continued to be active, and even some of them were renovated or enlarged. The continuation of the Islamization policy initiated then will be continued now as well. It can be detected, for instance, in the Christian suburb located north of the walled perimeter, which was provided with a mosque in the 10th century. The introduction of this building brought the urban regression of the Christian areas in benefit of the new Islamic suburb, which experienced a notable growth from this moment on.

Figure 6.

New mosques built during the Caliphate in the western and northern suburbs. (a) Mosque of Fontanar (Luna and Zamorano 1999, p. 168, Figure 2). (b) Mosque in the bus station (González Gutiérrez 2016a, p. 442, Figure 238). (c) Mosque of Naves de Fontanar (Vaquerizo and Murillo 2010, p. 665, Figure 350). (d) Mosque in Centro de Transfusión. Basis plan: Vaquerizo and Murillo 2010, p. 541, Figure 251. All images used by the permission of authors.

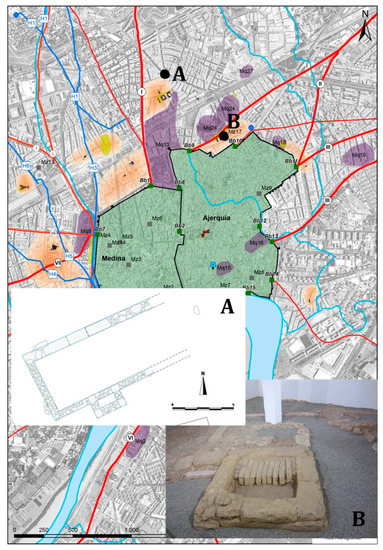

The fall of the Caliphate meant the destruction and abandonment of Western mosques, as well as few new foundations. These were more modest than the complexes projected during the Umayyad centuries (see Figure 7). At the same time, the ones that remained in the Medina and the Axerquía do not show significant changes in this period. Their functional continuity along the centuries is more related to the symbolic, emblematic, and territorial meaning that they acquired in each of the districts than to their architectural characteristics. These ideological implications in the urban fabric probably also favored the transformation of some of these mosques in churches after the Christian conquest in the 13th century. Some of them, in certain cases emerged in emiral times, reached an extraordinary longevity that might have depended on their condition of pious foundation. However, this statement does not mean that all the late-Islamic mosques were transformed into churches. Such a transformation was fruit of a different cultural group that transformed the city according to new needs and stimuli. Therefore they must be addressed and studied from other approaches and objectives henceforth (González Gutiérrez 2016b, pp. 285–87).

Figure 7.

Mosques built after the fall of the Caliphate. (A) Mosque in Santa Rosa. (B) Mosque in Ollerías neighborhood (picture by author). Basis plan: Vaquerizo and Murillo 2010, p. 707, Figure 369. All images used by the permission of authors.

4. Final Remarks

We have shown how research on religious urban spaces in al-Andalus has been concentrating mainly on Friday mosques. Among all of them, the Great Mosque of Córdoba has stood out. The sponsors of these mosques were commonly the rulers, who legitimized and displayed the power of their dynasties through them. However, there were other smaller mosques, usually disregarded by research, which had a multifunctional nature and were key to understanding the arrangement of cities and their meaning in the Umayyad building strategies. The great variety of these mosques in terms of formal appearance and, more specifically, in terms of functions performed, does not fit in the existing typologies.

Because of this, we suggest a new classification in which the andalusí examples can be arranged more accurately. This classification, which prioritizes functions over architectural appearance, is only composed of two main groups. The first one is for major or Friday mosques, that is to say, the ones that congregate the Muslim community for the noon Friday prayer. The second one includes all the so-called secondary mosques, in different categories: neighborhood mosques, which were at the general service of all the inhabitants; private masāŷid, only for the use of specific groups; and others, such as funerary mosques, for more delimited uses. This classification is flexible and, therefore, able to be extended and enriched from now on in the light of future discoveries.

Surely, the number of mosques that existed in al-Andalus was far higher than the figures documented by archaeology to date. However, the cases located in Córdoba and Toledo show that the general unawareness about mosques and their importance in the urban fabric is not due to researchers’ apathy or to the lack of buildings to be analyzed, but to the need of new viewpoints to be applied. Remains of many former masāŷid are still to be uncovered, but this task requires new approaches that are able to go beyond architectural styles, and landscape analyses to help us understand the role performed by mosques in the cities.18

The erection of mosques in the Umayyad capital was directly related to the development of Islamization policies. They also served to manifest the presence and hegemony of the Umayadd dynasty. Their locations were usually chosen to encourage the development and growth of new Islamic neighborhoods, especially in areas far from the walled perimeter. Understanding mosques in their urban context has been, indeed, key to comprehending the historical processes occurred in Córdoba during the Islamic stage.

Because all of these reasons, we believe that developing these analyses in other Islamic cities, even beyond the al-Andalus area, will be surely fruitful for a better knowledge of mosques, but also of cities themselves. Studying mosques addressing all their multi-functional aspects and their impact in the urban fabric is crucial to transcending the historicist and descriptive vision of the Islamic city and its elements, and also encourages understanding urbanism from an evolutionary and functional perspective. We are not able to determine whether the urban insertion of Qurṭuba’s mosques constituted a pattern for other Muslim settlements, but this study case may be a reference for other cities, in which the diachronic study of urban processes, with mosques as the focal point, should be undertaken.

Consequently, we hope that our results help to stimulate research on mosques not as an isolated architectural element, but as key pieces to define Islamic cities and the urban dynamics associated with them. Since mosques are the unmistakable symbol of Islam, they should have a privileged position in urban, global, and diachronic analyses of Medieval Islamic urbanism.

Funding

This research was partially funded by Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (Gobierno de España), Programa de Becas FPU convocatoria 2008 (Programa Nacional de Formación de Recursos Humanos de Investigación, del Plan Nacional de Investigación Científica, Desarrollo e Innovación Tecnológica 2088-2011).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Abu Lughod, Janet. L. 1987. The Islamic city. Historic myth, Islamic essence, and contemporary relevance. Journal of Middle East Studies 19: 155–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acién, Manuel, and Antonio Vallejo. 1998. Urbanismo y Estado Islámico. De Corduba a Qurtuba—Madinat al-Zahra. In Genèse de la ville islamique en Al-Andalus et au Maghreb Occidental. Edited by Patrice Cressier and Mercedes García Arenal. Madrid: Casa de Velázquez, pp. 107–36. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jusani, Ibn Harit. 2005. Historia de los jueces de Córdoba. Córdoba: Ayuntamiento de Córdoba. [Google Scholar]

- Almagro, Antonio. 1993. El alminar de la mezquita aljama de Zaragoza. Madrider Mitteilungen 34: 251–66. [Google Scholar]

- Almagro, Antonio. 2001. La arquitectura en al-Andalus en torno al año 1000: Medina Azahara. In La Península Ibérica en torno al año 1000. VII Congreso de Estudios Medievales. Ávila: Fundación Sánchez Albornoz, pp. 165–91. [Google Scholar]

- Almagro, Antonio. 2007. De mezquita a Catedral. Una adaptación imposible. In La piedra postrera. V Centenario de la conclusión de la Catedral de Sevilla 1, Ponencias. Edited by Alfonso Jiménez Martín. Sevilla: Taller Dereçeo, pp. 13–45. [Google Scholar]

- Anglada, Rocío, Alejandro Jiménez Hernández, and María Trinidad Gómez Saucedo. 2017. Cementerios, mezquitas y lugares de culto de la Carmona andalusí. In Religión y espiritualidad en Carmona: De la Prehistoria a los tiempos contemporáneos. Edited by Manuel González and Antonio Caballos. Sevilla: Universidad de Sevilla y Ayuntamiento de Carmona, pp. 199–228. [Google Scholar]

- Arévalo, Federico. 2011. El amurallamiento externo de la mezquita aljama de la Sevilla almohade: una hipótesis a partir de una muralla fosilizada, de las excavaciones arqueológicas y del análisis gráfico del parcelario. In La Catedral sin la Catedral. Edited by Alfonso Jiménez Martín. Sevilla: Aula Hernán Ruiz: Catedral de Sevilla, pp. 5–56. [Google Scholar]

- Behrens-Abouseif, Doris. 2000. La conception de la ville dans la pensé arabe du Moyen Âge. In Mégapoles méditerranéennes. Géographie urbaine retrospective. Edited by Claude Nicolet, Robert Ilbert and Jean Charles Depaule. París: École française de Rome, pp. 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Berges, Luis. 2007. La iglesia de la Magdalena (Jaén). De mezquita islámica a templo cristiano. Arqueología yTerritorio Medieval 14: 69–102. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, Jonathan. 1993. On the transmission of design in Early Islamic Architecture. Muqarnas 10: 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonine, Michael. 1990. The sacred direction and city structure: A preliminary analysis of the Islamic cities of Morocco. Muqarnas 7: 50–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrás, Gonzalo, and Bernabé Cabañero. 2012. La Aljafería y el Arte del Islam Occidental en el siglo XI, Actas del Seminario Internacional celebrado en Zaragoza los días 1, 2 y 3 de diciembre de 2004. Zaragoza: Institución Fernando el Católico. [Google Scholar]

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund. 2010. Mosque. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed. Brill Electronic edition. Leiden: Brill, vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Brogiolo, Gian Pietro. 2011. Le origini della città medievale. Mantova: SAP Società Archeologica. [Google Scholar]

- Cabañero, Bernabé. 2007. La Aljafería de Zaragoza. Artigrama 22: 103–29. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, Susana. 1999. La mezquita de Bab al-Mardum y el proceso de consagración de pequeñas mezquitas en Toledo (S. XII–XIII). Al-Qantara 20: 299–330. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, Susana. 2004. Las mezquitas de pequeñas ciudades y núcleos rurales de al-Andalus. Ilu. Revista de Ciencia de las Religiones. Anejos 10: 39–64. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, Susana. 2014. Las mezquitas de al-Andalus. Almería: Fundación Ibn Tufayl. [Google Scholar]

- Carballeira, Ana María. 2002. Legados píos y fundaciones familiares en al-Andalus (siglos IV/X-VI/XII). Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas de España. [Google Scholar]

- Carrero, Eduardo. 2005. De mezquita a catedral. La Seo de Huesca y sus alrededores entre los siglos XI y XV. In Catedral y ciudad medieval en la Península Ibérica. Edited by Eduardo Carrero and Daniel Rico. Murcia: Marcial Pons, pp. 293–317. [Google Scholar]

- Casal, María Teresa, Alberto León, Rosa López, Ana Valdivieso, and Patricio Soriano. 2006. Espacios y usos funerarios en la Qurtuba islámica. Anales de Arqueología Cordobesa 17: 257–90. [Google Scholar]

- Castejón, Rafael. 1929. Córdoba Califal. Boletín de la Real Academia de Córdoba 25: 255–339. [Google Scholar]

- Cómez, Rafael. 1994. Fragmentos de una mezquita sevillana: la aljama de Ibn Adabbas. Laboratorio de Arte, Revista del Departamento de Historia del Arte 7: 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Cressier, Patrice. 1984. Les chapiteaux de la grande mosquée de Cordoue (oratoires d’ ‘Abd al-Raḥmān I et d’ ‘Abd al-Raḥmān II) et la sculpture de chapiteaux à l’époque émirale: première partie. Madrider Mitteilungen 25: 216–81. [Google Scholar]

- Cressier, Patrice. 1985. Les chapiteaux de la grande mosquée de Cordoue (oratoires d’ ‘Abd al-Raḥmān I et d’ ‘Abd al-Raḥmān II) et la sculpture de chapiteaux à l’époque émirale: deuxième partie. Madrider Mitteilungen 26: 257–313. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, Keppel Archibald Cameron. 1979. Early Muslim Architecture Volume II: Early ‘Abbasids, Umayyads of Cordova, Aghlabids, Tulunids, and Samanids, A. D. 751–905. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Vicente, Juan Ignacio. 2014. La iglesia fernandina de San Lorenzo de Córdoba. Estudio histórico-arqueológico. Master’s thesis, University of Córdoba, Córdoba, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Dickie, James. 1985. Dios y la Eternidad: Mezquitas, madrasas y tumbas. In La arquitectura del mundo islámico; su historia y significado. Edited by George Michell and Ernst Grube. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, pp. 15–47. [Google Scholar]

- Escribano, Víctor. 1964–1965. La mezquita de la calle Rey Heredia. Al-Mulk 4: 83–101. [Google Scholar]

- Ettinghausen, Richard, and Oleg Grabar. 1987. Arte y Arquitectura del Islam, 650–1250. Madrid: Cátedra. [Google Scholar]

- Ewert, Christian. 1973. La mezquita de Mértola (Portugal). Cuadernos de la Alhambra 9: 3–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ewert, Christian. 1987. Tipología de la mezquita en Occidente: de los Omeyas a los Almohades. In Arqueología Medieval Española, Congreso Madrid 19–24 enero 1987 tomo I: Ponencias. Madrid: Consejeria de Cultura, pp. 180–204. [Google Scholar]

- Ewert, Christian. 1995. Precedentes de la arquitectura nazarí: La arquitectura de al-Andalus y su exportación al Norte de África hasta el siglo XII. In Arte Islámico en Granada. Propuesta para un Museo de la Alhambra. Granada: Patronato de la Alhambra y el Generalife, pp. 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Féijoo, Santiago, and Miguel Alba. 2002. El sentido de la alcazaba emiral de Mérida: su aljibe, mezquita y torre de señales. Mérida. Excavaciones arqueológicas 8: 565–86. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Puertas, Antonio. 2004. La mezquita aljama de Granada. Miscelánea de estudios árabes y hebraicos 53: 39–76. [Google Scholar]

- Frishman, Martin, and Hasan-Uddin Khan. 1994. The mosque: History, architectural development and regional diversity. Nueva York: Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- García Sanjuán, Alejandro. 2002. Hasta que Dios herede la Tierra: Los bienes habices en al-Andalus (siglos X–XV). Huelva: Universidad de Huelva. [Google Scholar]

- Golvin, Lucien. 1960. La mosquée: Ses origines, sa morphologie, ses diverses fonctions, son rôle dans la vie musulmane, plus spécialement en Afrique du Nord. Argelia: Institut d’études supérieures islamiques d’Alger. [Google Scholar]

- Golvin, Lucien. 1979. Essai Sur l’Arquitecture Religieuse Musulmane, vol. 4, L’Art Hispano-Musulman. Paris: Klinksieck. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Moreno, Manuel. 1945. La mezquita mayor de Tudela. Príncipe de Viana 18: 9–27. [Google Scholar]

- González Gutiérrez, Carmen. 2012. Las mezquitas de barrio de Madinat Qurtuba: una aproximación arqueológica. Córdoba: Diputación Provincial de Córdoba. [Google Scholar]

- González Gutiérrez, Carmen. 2014. Las mezquitas secundarias de Madinat Qurtuba. Propuesta de análisis arqueológico. In La Ciutat Medieval i Arqueologia: VI Curs Internacional d’Arqueologia Medieval. Edited by Flocel Sabaté and Jesús Brufal. Lleida: Pagès editors, pp. 293–317. [Google Scholar]

- González Gutiérrez, Carmen. 2015. Arqueología y mezquitas urbanas en al-Andalus: Estado de la cuestión. In Arqueologia Medieval. Els espais sagrats, VII Curs Internacional d’Arqueologia Medieval. Edited by Flocel Sabaté and Jesús Brufal. Lleida: Pagès editors, pp. 177–94. [Google Scholar]

- González Gutiérrez, Carmen. 2016a. Las mezquitas de la Córdoba islámica: Concepto, tipología y función urbana. Córdoba: UCOPress. Available online: https://helvia.uco.es/xmlui/handle/10396/13194?show=full (accessed on 18 June 2018).

- González Gutiérrez, Carmen. 2016b. Las mezquitas de barrio de Madinat Qurtuba 15 años después: espacios religiosos urbanos en la capital andalusí. Anales de Arqueología Cordobesa 27: 267–92. [Google Scholar]

- González Gutiérrez, Carmen. 2017. Madinat Qurtuba, urban development and islamization: The evidence of minor mosques. Beiträge zur Islamischen Kunst und Archäologie 5: 12–27. [Google Scholar]

- González Sánchez, Vidal. 1996. De mezquita mayor de Málaga a catedral renacentista. Descubrimiento de elemento revelador de una metamorfosis, pasando por la “Iglesia Vieja”. Isla de Arriarán, revista científica y cultural 7: 93–116. [Google Scholar]

- Grabar, Oleg. 1979. La formación del arte islámico. Madrid: Cátedra. [Google Scholar]

- Grabar, Oleg. 2004. Arte y cultura en el mundo islámico. In Islam. Arte y Arquitectura. Edited by Markus Hattstein and Peter Delius. San Mauro: Könemann, pp. 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Vera, José Antonio. 2004. La mezquita aljama de Zaragoza a la luz de la información arqueológica. Ilu. Revista de ciencias de las religiones. Anejos 10: 65–91. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, Félix. 1975. El alminar de Abd al-Rahman III en la Mezquita Mayor de Córdoba: génesis y repercusiones. Granada: Patronato de la Alhambra. [Google Scholar]

- Hillenbrand, Robert. 1994. Islamic Architecture. Form, functions and meaning. Edimburgo: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hillenbrand, Robert. 2010. Islamic Art and Architecture. Londres: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo, Ricardo. 1990. Excavaciones de Vascos: resultados y planificación. In Actas del primer Congreso de Arqueología de la provincia de Toledo. Toledo: Diputación Provincial de Toledo, pp. 433–58. [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo, Ricardo, and Jorge de Juan Ares. 2004. Excavaciones en la Alcazaba de Vascos (Navalmoralejo, Toledo). In Investigaciones arqueológicas en Castilla La Mancha, 1996–2002. Toledo: Junta de Comunidades de Castilla La Mancha, pp. 423–36. [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo, Ricardo, and Germán Prieto. 1993–1994. Una pequeña mezquita encontrada en Vascos (Navalmoralejo, Toledo). Cuadernos de la Alhambra 29–30: 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Hernández, Alejandro. 2018. Antes de Santa María: ensayo de restitución de la mezquita aljama a través de un análisis arqueológico. In La obra gótica de Santa María de Carmona: Arquitectura y ciudad en la transición a la edad Moderna. Edited by Antonio Luis Ampliato and Juan Clemente Rodríguez Estévez. Sevilla: Universidad de Sevilla, pp. 49–68. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Sancho, Álvaro. 2016. La mezquita mayor almohade de Sevilla: Análisis arqueológico de su construcción. Tesis Doctoral, Universidad de Sevilla, Seville, Spain. Available online: https://idus.us.es/xmlui/handle/11441/39118 (accessed on 18 June 2018).

- Juez, Francisco. 1999. Símbolos del poder en la arquitectura de al-Andalus. Tesis Doctoral, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Jurado Jiménez, Francisco. 2000. Estudios previos a la restauración de la ermita del Cristo de la Luz, antes mezquita de Bab-al-Mardum. Tulaytula 6: 15–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kuban, Dogan. 1974. Muslim religious architecture, Part I: the mosque and its early development. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Lévi-Provençal, Evariste. 1932. L’Espagne musulmane au Xème siècle. París: Maisonneuve. [Google Scholar]

- Longhurst, Christopher. 2012a. Theology of a mosque. The sacred inspiring form, function and design in Islamic Architecture. Lonaard Magazine 8-II: 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Longhurst, Christopher. 2012b. How to Read a Mosque. Encounter 374: 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- López Guerrero, Rosa, and Ana Valdivieso. 2001. As mezquitas de barrio en Córdoba: Estado de la cuestión y nuevas líneas de investigación. Anales de Arqueología Cordobesa 12: 215–39. [Google Scholar]

- Luna, Dolores, and Ana Zamorano. 1999. La mezquita de la antigua finca El Fontanar (Córdoba). Cuadernos de Madinat al-Zahra 4: 145–73. [Google Scholar]

- Macías, Santiago. 2006. Mértola: le dernier port de la Méditerrannée. Catalogue de l’exposition Mértola, histoire et patrimoine (Ve-XIIIe siècles), tome I. Mértola: Campo Arqueológico de Mértola. [Google Scholar]

- Macías, Santiago, Claudio Torres, Joaquim Manuel Ferreira, María de Fátima Rombouts, and Susana Gómez. 2011. Mesquita: igreja de Mértola. Mértola: Campo Arqueológico de Mértola. [Google Scholar]

- Marfil, Pedro. 2010. Las puertas de la Mezquita de Córdoba durante el Emirato omeya. Doctoral thesis, University of Córdoba, Córdoba, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Mcauliffe, Jane Dammen. 2001–2006. Encyclopaedia of the Qu’ran. Available online: www.brill.com (accessed on 30 November 2010).

- Murillo, Juan Francisco, María Teresa Casal, and Elena Castro. 2004. Madinat Qurtuba. Aproximación al proceso de formación de la ciudad emiral y califal a partir de la información arqueológica. Cuadernos de Madinat al-Zahra 5: 257–90. [Google Scholar]

- Neglia, Giulia Annalinda. 2008. Some historiographical notes on the Islamic city, with particular references to the visual representation of the built city. In The city in the Islamic world. Edited by Salma Khadra Jayyusi, Renata Holod, Antillio Petruccioli and André Raymond. Leiden: Brill, vol. I, pp. 3–46. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulo, Alexandre. 1977. El Islam y el Arte Musulmán. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili. [Google Scholar]

- Pavón, Basilio. 1966. Memoria de la excavación de la mezquita de Madinat al-Zahra. Madrid: Dirección General de Bellas Artes. [Google Scholar]

- Pavón, Basilio. 1976. Alminares cordobeses. Boletín de la Asociación Española de Orientalistas 12: 181–210. [Google Scholar]

- Pavón, Basilio. 2009. Tratado de arquitectura hispanomusulmana vol. IV: “Mezquitas. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. [Google Scholar]

- Peláez, David. 2000. El proceso judicial en la España musulmana (siglos VIII–XII), con especial referencia a la ciudad de Córdoba. Córdoba: Ediciones El Almendro. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, Antonio. 2006. Mezquitas en Toledo, a la luz de los nuevos descubrimientos. Los Monográficos del Consorcio, 5. Toledo: Consorcio de Toledo. [Google Scholar]

- Rütenik, Tobias. 2008. Transformación de mezquitas a iglesias en Toledo. Berlín: Technische Universität Berlin. [Google Scholar]

- Rütenik, Tobias. 2017. Transformation von Moscheen zu Kirchen auf der iberischen Habinsel. Petesberg: Berliner Beiträge zur Bauforschung und Denkmalpflege 14. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Madrid, Sebastián. 2005. Actividad Arqueológica Preventiva: Proyecto de ampliación del centro de transfusión sanguínea de Córdoba (Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía), Córdoba, Unpublished manuscript.

- Sánchez, José Antonio, and Luis García. 2007. Fulgor en el Alcázar musulmán de Murcia: El conjunto religioso funerario de San Juan de Dios. In Las artes y las ciencias en el Occidente musulmán. Edited by Maribel Parra and Alfonso Robles. Murcia: Museo de la Ciencia, pp. 234–50. [Google Scholar]

- Souto, Juan Antonio. 1989. Textos árabes relativos a la mezquita aljama de Zaragoza. Madrider Mitteilungen 39: 391–426. [Google Scholar]

- Souto, Juan Antonio. 1993a. Excavaciones en la Seo del Salvador de Zaragoza (1984–1986). Actividades realizadas e inventario de los hallazgos. Boletín de Arqueología Medieval 7: 249–67. [Google Scholar]

- Souto, Juan Antonio. 1993b. Restos arquitectónicos de época islámica en el subsuelo de La Seo del Salvador (Zaragoza): Campañas de 1984 y 1985. Madrider Mitteilungen 34: 308–50. [Google Scholar]

- Souto, Juan Antonio. 2004. La mezquita: definición de un espacio. Ilu. Revista de ciencias de las religiones. Anejos 10: 103–9. [Google Scholar]

- Souto, Juan Antonio. 2009. La mezquita aljama de Córdoba: De cómo Alandalús se hizo edificio. Zaragoza: Instituto de Estudios Islámicos y Oriente Próximo. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, Henri. 1976. Les mosaiques de la grande mosquée de Cordoue. Berlín: Walter de. Gruyter & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Terrasse, Henri. 1932. L’art hispano-mauresque des origines aux XII siécle. París: Institut des Hautes Études Marocaines. [Google Scholar]

- Torres Balbás, Leopoldo. 1945. La mezquita mayor de Granada. Al-Andalus 10: 409–32. [Google Scholar]

- Torres Balbás, Leopoldo. 1955. El mihrab almohade de Mértola (Portugal). al-Andalus 20: 188–195. [Google Scholar]

- Valdés, Fernando. 1999. La mezquita privada de ‘Abd al-Raḥmān Ibn Marwan al-Yilliqi en la alcazaba de Badajoz. CuPAUAM 25: 267–90. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo, Antonio. 2006. Madīnat al-Zahrā’. Guía oficial del conjunto arqueológico. Córdoba: Junta de Andalucía. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo, Antonio. 2009. Intervención arqueológica en el tramo sur de la muralla de Madīnat al-Zahrā’ 2007–2008. Patrimonio cultural de España 0: 215–24. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo, Antonio. 2010. La ciudad califal de Madīnat al-Zahrā’. Arqueología de su excavación. Córdoba: Almuzara. [Google Scholar]

- Valor, Magdalena. 1993. La mezquita de Ibn Adabbas de Sevilla: estado de la cuestión. Estudios de historia y de arqueología medievales 9: 299–314. [Google Scholar]

- Valor, Magdalena. 2008. Sevilla almohade. Málaga: Editorial Sarriá. [Google Scholar]

- Vaquerizo, Desiderio, and Juan. Francisco Murillo. 2010. El anfiteatro romano de Córdoba y su entorno urbano. Análisis arqueológico (ss. I–XIII). Córdoba: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Córdoba, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Vogt-Göknil, Ulya. 1975. Mosquées. Grands courants de l’architecture islamique. París: Chêne. [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley, Paul. 2001. The places where men pray together. Cities in Islamic lands, Seventh through the Tenth Centuries. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | This Encyclopedia (Mcauliffe 2001–2006) classifies mosques concerning their architectural, morphological, and geographical features (see review at (González Gutiérrez 2016a, pp. 56–57)). This physical ordering has also been followed, corrected and modified by authors such as Vogt-Göknil (1975); Dickie (1985); Frishman and Khan (1994); Souto (2004); or Bloom (1993), among others. |

| 2 | Summarized at González Gutiérrez 2016a, pp. 57–58. |

| 3 | Further discussion about this, especially regarding al-Andalus’ circumstances, has already been published (see González Gutiérrez 2015). |

| 4 | This is the most widespread an accepted explanation for the term ‘mosque’. It has been assumed and expanded by many other authors (Golvin 1960; Kuban 1974; Grabar 1979, 2004; Souto 2004; Longhurst 2012a, p. 4; 2012b, p. 3, etcetera). However, it is not the only one available, as the Islamic doctrine also records, since the time of the Prophet, the term mosque as “House of God” (bayt Allāh) (García Sanjuán 2002, p. 216). |

| 5 | Mosques from Late Islamic and Nasrid times still showed monumentality and splendour. The need for an austere appearance as a sign of their pious purposes entered very often in contradiction with the strong ostentation manifested by the rulers (Juez 1999; Longhurst 2012a, 2012b). |

| 6 | This work is focused on urban areas. For further information on rural spaces, see (Calvo 2004, 2014). |

| 7 | However, not all urban main mosques were transformed into Christian temples, since not all the Islamic settlements have survived until present days. It is the case of, for example, Madīnat al-Zahrā’ (Vallejo 2006, 2010), where the damage caused by the continued plunder has severely undermined the vestiges of its Friday mosque (Pavón 1966). |

| 8 | Publications on the great mosque of Córdoba are countless, and offer different approaches in terms of focus, depth and quality. Without the will to be exhaustive, the works of H. Terrasse (1932); F. Hernández (1975); H. Stern (1976); K. A. C. Creswell (1979); A. Papadopoulo (1977); O. Grabar (1979) alone and with R. Ettinghausen and Grabar (1987); C. Ewert (1987, 1995); P. Cressier (1984, 1985) or R. Hillenbrand (2010), among many others, should be always regarded. |

| 9 | There are several counts for Córdoba (see González Gutiérrez 2012, pp. 51–ff.) which reflect an excessive number of mosques for the city. These exaggerations have been interpreted as the intent to show the great monumentality of the city made by chroniclers, as well as to reflect the importance that mosques had for its imperial image. |

| 10 | The remains of a former mosque were identified at the Alcazaba, but it was not corresponding to a secondary or neighborhood mosque, open to the majority of the population (Calvo 2014, pp. 546–51). |

| 11 | This study is also suggesting a possible use of this mosque as a signal tower. |

| 12 | However, a study which tries to analyze the role of these mosques in the urban landscape still remains to be conducted. |

| 13 | Among them, they included some minarets reused as belfries after the Christian conquest, which still are a popular part of Córdoba’s heritage and cultural landscape (González Gutiérrez 2017b). |

| 14 | This compilation article has been, for many years, the only publication available on this specific subject. However, even though discoveries continued to emerge from 2001 onwards, no author considered necessary to review or enlarge this contribution. Despite that, it continued to raise awareness not only about how these buildings were, but about their role in the city and their importance in people’s lives |

| 15 | First through our master’s thesis (González Gutiérrez 2012), and finally with our doctoral work (González Gutiérrez 2016a). |

| 16 | The detailed observation of the face of the minaret in which the window is still conserved has been put in relation with the study of other pieces. Ashlars used in Córdoba can be compared with others used to build several emiral minarets in al-Andalus, such as San Juan or Santiago, both in Córdoba, or even the minaret of Ibn ‘Adabbas in Seville or El Salvador in Toledo. Other elements taken into account are related with the typologies and dimensions of the windows. |

| 17 | On many occasions, they were erected as pious foundations. There are many written testimonies of relatives of the Emirs or the Caliphs, or by members belonging to the Court, defraying these constructions. This was made to encourage the social support to the Umayyads’ regime and to increase the policies of Islamization. |

| 18 | At this respect, it is fair to say that there are at least two compendiums about andalusí mosques. The first one was published by B. Pavón (2009), who collects data from many different mosques documented in al-Andalus. Nevertheless, it lacks a typological organization and it does not develop any global analysis. In other words, this is an important compiling of previous works, but does not bring new perspectives nor results to the topic. Very recently, the monograph Las mezquitas de al-Andalus has been published (Calvo 2014). Result of her Doctoral Thesis, the book of Calvo also includes a catalog or corpus of mosques in al-Andalus and updates the one offered by Pavón in light of new archaeological information. It also goes further by exploring the role of different types of mosques in the lives of urban and rural areas’ inhabitants, and in the creation of urban spaces themselves. Even though it does not address monographic urban studies like the one we are suggesting, it is an important starting point for analyses like ours. |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).