Fortified Construction Techniques in al-Ṭagr al-Awsaṯ, 8th–13th Centuries

Abstract

:1. Introduction, State of the Art, Objectives, and Methodology

- To understand the specificity of Islamic fortified construction in central al-Andalus up until the invasion of the North African Empires of Almoravids and Almohads.

- To study the building characteristics of the two main techniques employed—bonded masonry (with stone) and formworked masonry (with earth or concrete)—through several examples.

- To show other study cases beyond the classical ones in order to increase the knowledge of Islamic fortifications in Spain, explained by means of the current research by the authors.

- To organize and define a series of phases (according to technique) in order to understand their geographical and chronological distribution.

2. Islamic Fortified Construction: The Territory and the Actors

The Berbers have no skills in the siege of cities and the taking of fortresses with the use of military devices, so they cannot do it, and only the Arabs can do this as they are experts of the cities with all their armament, materials and tools, and they know how to build fortresses and all that is convenient to punish the enemies.

The lord of Badajoz, ‘Abdalláh b. Muhammad, was afraid of some Berbers entered Evora when it had been deserted. So, along with his men, he destroyed the towers and demolished the rest of its walls, until they were brought down.

After, an-Nāsir received several letters from him [Mūsá b. Abī l-’Āfiya] asking for help to build the castle of Yara, where he had retired to, and asking for workers and material.…an-Nāsir answered him with kind words … and supported his request to build his fortress. And he sent his proto-architect Muḥammad b. Walīd b. Fuštayq, with 30 masons, 10 carpenters, 15 diggers, six competent lime mortar makers, and two matting makers, chosen amongst the most skillful of their profession, accompanied by certain number of tools and accessories for the works. All this was sent by the sultan for the period that the works required. He also sent to Musa many provisions for him and his people.

Also in this campaign, Aḥmad b. Muḥammad b. Ilyās started the building of the ruined city of Saktan in the central border, fortifying its flat areas with a great number of workers with building works which very soon made a strong city.

After this, Muḥammad b. Ibrāhīm b. Ḥāŷŷāŷ, lord of Carmona, returned to Cordoba to subdue himself … he was associated with the police chief Qāsim b. Walīd al-Kalbī, who he was friends with. Both of them went towards Carmona and, close to Seville near the Tocina Gate, mercenaries entered the Lora fortresses and then went to Aljarafe, where they built the fortress of Cabra.…He ordered the city called Madinat al-fath (City of the Conquest) be built on the mount of Chalencas, his first stop, to which he brought tools and workers to finish it rapidly.…He [the Caliph] assigned an army to Durrí as caíd [a kind of judge who represents the supreme authority of the Caliph] of the Medium Mark. He had to go around the Muslim fields and ways from Atienza to Talavera, distributing men in these areas to build and repair with excellent quality the damaged fortresses, towers, and watchtowers, supplying them with food and many tools.

‘Abdallād b.Marwān was the first to capture the city of Evora, rebuilding it with men and tools and accessories, bringing builders with materials and beginning to rebuild the demolished wall, closing breaches and reinforcing corners and closing then its strong gates.

3. Fortified Systems in the Territories of al-Andalus and the Medium Mark (al-Ṭagr al-Awsaṯ)

4. Stone Techniques in the Fortified Buildings of al-Ṭagr al-Awsaṯ

The fortress of Ma’zūna … was excellently built and, when he [the jew ‘Abdarraḥmān] learnt this, he sent many teams of workers to demolish it and, with the wood and the stones, he built a tall fortress in the place called H.nd.r.ŷ, garrisoned with men and supplies.

- Materials (origin and type)

- Disposition in the wall

- Binding element (type of mortar)

- Finishings (interstice—curb, plaster)

4.1. Materials: Origin and Type

- Ashlar

- 1.1.

- Square on all sides

- 1.2.

- Squared only on visible faces

- 1.3.

- Reused materials

- Irregular ashlar

- 2.1.

- Beveled

- 2.2.

- Only faceted

- 2.3.

- Very irregular ashlar—characterized by poor construction

- Masonry

- 3.1.

- Squared masonry

- 3.2.

- Masonry extracted from a quarry and faceted

- 3.3.

- Raw large masonry

- 3.4.

- Raw medium/small sized masonry

- Small masonry: between 10 cm × 15 cm × 10 cm and 20 cm × 15 cm × 10 cm;

- Average masonry: between 25 cm × 25 cm × 15 cm and 35 cm × 25 cm × 15 cm;

- Large masonry: between 40 cm × 35 cm × 25 cm and 60 cm × 35 cm × 25 cm.

4.2. Disposition in the Wall

- In regular courses

- Alternating courses

- 2.1.

- With engatillados (any angle to adapt to the course the ashlar)

- 3.2.

- With different materials (masonry)

- Irregular courses

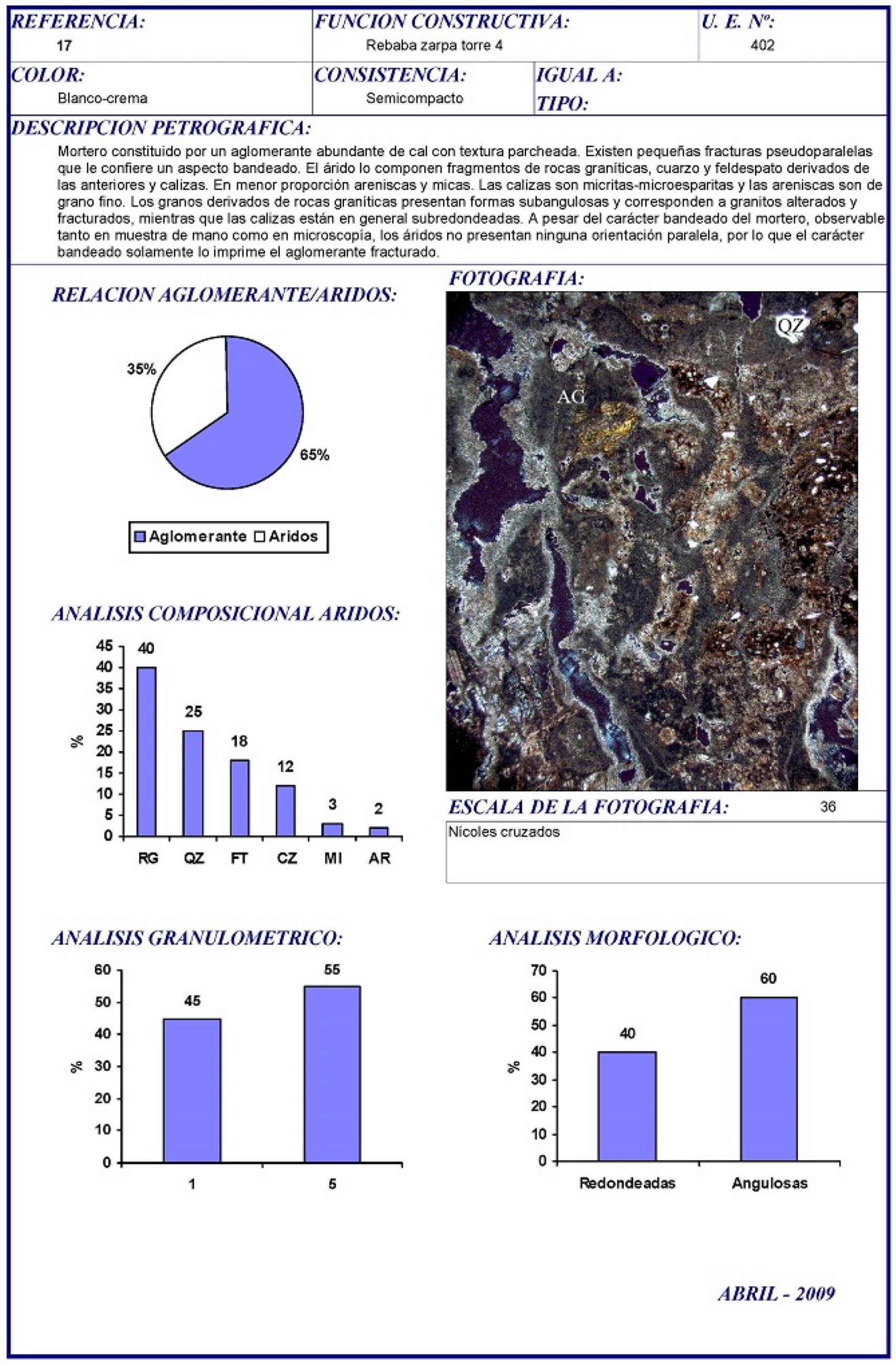

4.3. Binding Element

4.4. Stone Finishing

5. Formworked Masonries in the Fortifications of al-Ṭagr al-Awsaṯ

5.1. Rammed Earth Masonries

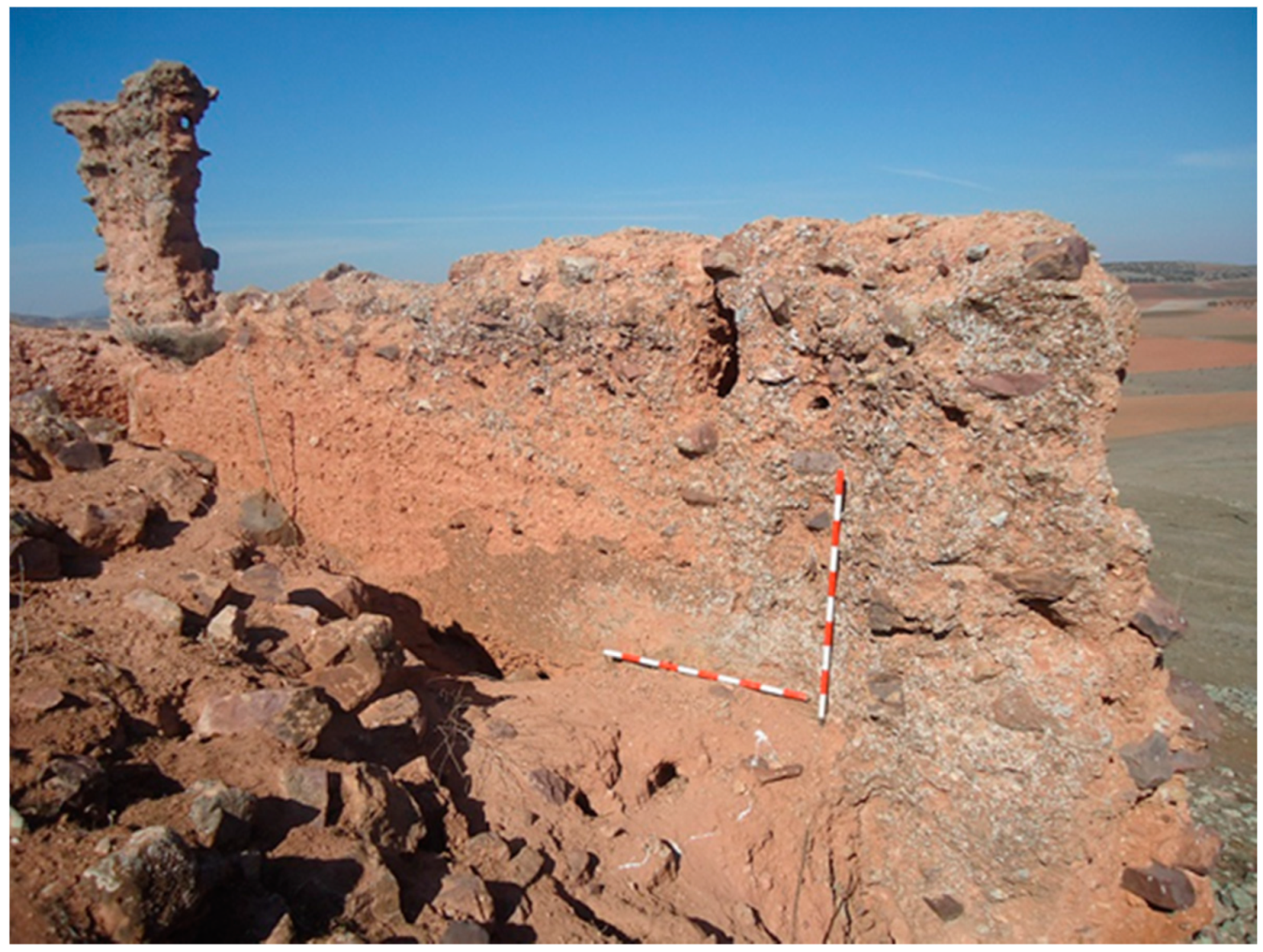

5.2. Concrete Masonries

6. Conclusions

6.1. Phase 1: From the 8th Century to the Middle of the 9th Century

6.2. Phase 2: The 9th to 10th Centuries

6.3. Phase 3: The 11th Century

6.4. Phase 4: The 12th and 13th Centuries

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ‘Abd Allah b., Buluggin. 2010. El siglo XI en 1a persona: Las memorias de ‘Abd Allah, último rey zirí de Granada destronado por los almorávides (1090). Translated by Emilio García Gómez y E. Lévi-Provençal. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, AEAM-Publicaciones. s. f. Asociación Española de Arqueología Medieval. Accedido 23 de agosto de 2018. Available online: http://aeam.es/category/publicaciones-de-la-aeam-2/ (accessed on 20 July 2018).

- Acién Almansa, Manuel Pedro. 2002. De nuevo sobre la fortificación del emirato. In Mil Anos de Fortificaçoes na Península Ibérica e no Magreb (500-1500): Simpósio Internacional sobre Castelos 2000. Lisboa: Colibrí. [Google Scholar]

- Almagro Basch, Martín, Luis Caballero Zoreda, Juan Zozaya Stabel-Hansen, and Antonio Almagro. 2002. Qusayr ‘Amra. Residencia y baños omeyas en el desierto de Jordania. Granada: Legado Andalusí. [Google Scholar]

- Almagro Gorbea, Antonio. 2008. La puerta califal del castillo de Gormaz. Arqueología de la Arquitectura 5: 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arce, Ignacio. 2006. De la ciudadela de Amman a Qasr Hallabat (1995–2006): Once años de investigación e intervenciones en el patrimonio omeya de Jordania. In La aventura española en Oriente (1166–2006), Vol. 2, 2006 (La arqueología española en Oriente: Nacimiento y desarrollo de una nueva ciencia). Subdirección General de Publicaciones, Información y Documentación. Madrid: Dialnet, pp. 107–15. [Google Scholar]

- Arce, Ignacio. 2009. De Roma al Islam. Tecnología y tipología arquitectónica en transición. Campaña de 2008. Informes y Trabajos 3: 151–60. [Google Scholar]

- Arce, Ignacio. 2010. Qasr Hallabat, Qasr Bshir aand Deir El Kahf. Building techniques, architectural typology and change of use of three quadriburgia from the limes arabicus. Interpretation and significance. In Arqueología de la Construcción II, los procesos constructivos en el mundo romano: Italia y provincias. Anejos de AEspA LVII. Mérida-Madrid: CSIC, pp. 456–81. [Google Scholar]

- Azuar Ruiz, Rafael. 2005. Las técnicas constructivas en la formación de al-Andalus. Arqueología de la arquitectura 4: 149–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuar Ruiz, Rafael, and Isabel Cristina Ferreira Fernandes. 2014. La fortificación del califato almohade. In Las Navas de Tolosa 1212–2012: Miradas cruzadas. Jaén: Universidad de Jaén. [Google Scholar]

- Azuar Ruiz, Rafael, Francisco José Lozano Olivares, María Teresa Llopis García, and Jose Luis Menéndez Fueyo. 1996. El falso despiece de sillería en las fortificaciones de tapial de época almohade en el Al-Andalus. Estudios de historia y de arqueología medievales 11: 245–78. [Google Scholar]

- Barrucand, Marianne, and Achim Bednorz. 1992. Arquitectura islámica en Andalucía. Colonia: Taschen. [Google Scholar]

- Bazzana, André. 2009. Castillos y sociedad en al-Ándalus: Cuestiones metodológicas y líneas actuales de investigación. In El castillo medieval en tiempos de Alfonso X el Sabio. Eiroa Rodríguez. Murcia: Universidad de Murcia. [Google Scholar]

- Bazzana, Andrè, Pierre Guichard, and Patrice Cressier. 1988. Les châteaux ruraux d’al-Andalus. Histoire et archéologie des husun du sud-est de l’Espagne. Madrid: Collection de la Casa de Velázquez, vol. 137. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco García, Juan Francisco, Miguel Angel Hervás Herrera, and Manuel Retuerce Velasco. 2012. Una primera aproximación arqueológica al oppidum oretano de Calatrava la Vieja (Carrión de Calatrava, Ciudad Real). Real Académia de Cultura Valenciana: Sección de estudios ibéricos D. Fletcher Valls. Estudios de lenguas y epigrafía antiguas—ELEA 12: 85–150. [Google Scholar]

- Bru Castro, Miguel Ángel. 2016a. Evidencias materiales y análisis sobre el origen del yacimiento andalusí de Vascos. Debates de Arqueología Medieval 6: 155–81. [Google Scholar]

- Bru Castro, Miguel Ángel. 2016b. La arquitectura fortificada de la Madīna de Vascos. Análisis arqueológico de un enclave andalusí. Madrid: Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Available online: http://purl.org/dc/dcmitype/Text (accessed on 20 July 2018).

- Canivell, Jacinto, Amparo Graciani, and Jesús Bermejo Tirado. 2015. Caracterización constructiva de las fábricas de tapia en las fortificaciones almohades del antiguo Reino de Sevilla. Arqueología de la Arquitectura 11: e025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmeta Gendrón, Pedro. 2003. Invasión e islamización. La sumisión de Hispania y la formación de al-Andalus. Jaén: Universidad de Jaén. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, K. A. C., Sir. 1979. Compendio de arquitectura paleoislámica. Anales de la Universidad Hispalense. Arquitectura. Sevilla: Sevilla Universidad. [Google Scholar]

- Daza Pardo, Enrique. 2003. Xadrach y Casteion. Castillos de España: Publicación de la Asociación Española de Amigos de los Castillos 131: 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- de Juan Ares, Jorge, and Jacobo Fernández del Cerro. 2005. El albacar islámico del castillo de Consuegra (Toledo). In Actas del III Congreso de Castellología Ibérica: 28 de octubre—1 de noviembre, Guadalajara de 2005. Madrid: Asociación Española de Amigos de los Castillos, Diputación Provincial de Guadalajara, pp. 123–32. [Google Scholar]

- Enderlein, V. 2001. Siria y Palestina: El califato de los Omeya. In El Islam. Arte y Arquitectura. Edited by Markus Hattstein and Peter Delius. Torino: Könemann, pp. 59–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ewert, Christian. 1968. Spanisch-islamische Systeme sich kreuzender Bögen: Die senkrechten ebenen Systeme sich kreuzender Bögen als Stützkonstruktionen der vier Rippenkuppeln in der ehemaligen Hauptmoschee von Córdoba.-v.2. Edited by Madrider Forschungen. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Puertas, Antonio. 2008. II. Mezquita de Córdoba: Abd al-Rahman I (169/785-786). El trazado proporcional de la planta y alzado de las arquerías del oratorio. La “qibla” y el “mihrab” del siglo VIII. Archivo español de arte 81: 333–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego Valle, David. 2016. La fortificación medieval en el Campo de Montiel (ss. VIII-XVI). Análisis de su secuencia histórica y constructiva. Espacio Tiempo y Forma. Serie III, Historia Medieval 29: 337–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego Valle, David, Jesús Molero García, and José Luis Sánchez Sánchez. 2015. Arqueología de la Arquitectura y construcción almohade. El ejemplo del Castillo de Miraflores (Piedrabuena, Ciudad Real). Cuadernos de Arquitectura y Fortificación 2: 9–42. [Google Scholar]

- Gallego Valle, David, Jesús Molero García, Francisco Javier Castilla Pascual, Cristina Peña Ruiz, and David Sanz Martínez. 2016. El uso del tapial en las fortificaciones medievales de Castilla-La Mancha: Propuesta de estudio y primeros resultados de la investigación. In Actas de las segundas jornadas sobre historia, arquitectura y construcción fortificada: Madrid, 6–7 de octubre de 2016. Madrid: Instituto Juan de Herrera, Fundación Cárdenas, Centro de Estudios José Joaquín de Mora, cop. [Google Scholar]

- Gil Crespo, Ignacio Javier. 2013. El debate de las influencias orientales en la arquitectura militar medieval española: Casos en la fortificación bajomedieval soriana. In Actas del Octavo Congreso Nacional de Historia de la Construcción. Madrid: Instituto Juan de Herrera. [Google Scholar]

- Gil Crespo, Ignacio Javier. 2016a. Islamic fortifications in Spain built with rammed earth. Construction History. International Journal of the Construction History Society 31: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gil Crespo, Ignacio Javier. 2016b. Castillos y villas de La Raya. Fortificación fronteriza bajomedieval en la provincia de Soria. Soria: Excelentísima Diputación Provincial de Soria. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Moreno Martínez, Manuel. 1951. El Arte Árabe español hasta los almohades. Arte mozárabe. Plus-Ultra. Madrid: Ars Hispaniae, Historia Universal del Arte Hispánico, vol. III. [Google Scholar]

- Grabar, Oleg. 1986. La formación del arte islámico, 4a ed. Arte. Grandes temas. Madrid: Cátedra. [Google Scholar]

- Grabar, Oleg. 2007. The Architecture of Power: Palaces, Citadels and Fortifications. In Architecture of the Islamic World. Its History and Social Meaning. Edited by George Michell. London: Thames and Hudson, pp. 48–79. [Google Scholar]

- Graciani, Amparo. 2009. La técnica del tapial en Andalucía occidental. In Construir en al-Andalus. Sevilla: Junta de Andalucía, Dirección General de Bienes Culturales. [Google Scholar]

- Graciani García, Amparo. 2009. Improntas y oquedades en fábricas históricas de tapial. Indicios constructivos. In Actas del Sexto Congreso Nacional de Historia de la Construcción. Edited by Santiago Huerta, Rafael Marín, Rafael Soler and Arturo Zaragozá. Madrid: Instituto Juan de Herrera, pp. 683–92. [Google Scholar]

- Gurriarán Daza, Pedro, and y Angel J. Sáez Rodríguez. 2002. Tapial o fábricas encofradas en recintos urbanos andalusíes. In En II Congreso Internacional "La Ciudad en Al-Andalus y el Magreb. Granada: Fundación El Legado Andalusí, pp. 561–625. [Google Scholar]

- Gurriarán Daza, Pedro. 2004. Hacia una construcción del poder. Las prácticas edilicias en la periferia andalusí durante el Califato. Cuadernos de Madinat al-Zahra: Revista de difusión científica del Conjunto Arqueológico Madinat al-Zahra 5: 297–325. [Google Scholar]

- Gurriarán Daza, Pedro. 2008. Una arquitectura para el califato: Poder y construcción en al-Andalus durante el siglo X. Anales de Arqueología Cordobesa 19: 261–76. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez Lloret, Sonia. 1998. El fin de las ciuitates y el génesis de las mudun. In Genèse de la ville islamique en al-Andalus et au Maghreb occidental. Madrid: Casa de Velazquez, pp. 137–57. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Giménez, Félix. 1961. El codo en la historiografía árabe de la mezquita mayor de Córdoba. Madrid: Imprenta y editorial Maestre. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Giménez, Félix. 1975. El alminar de ‘Abd al-Raḥmān III en la mezquita mayor de Córdoba. Génesis y repercusiones. Granada: Patronato de la Alhambra. [Google Scholar]

- Hervás Herrera, Miguel Ángel. 2016. Conservación y restauración en Calatrava La Vieja (1975–2010). Ph.D. thesis, Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, Castilla-La Mancha, Spain. María Esther Almarcha Núñez-Herrador (dir). Available online: https://ruidera.uclm.es/xmlui/handle/10578/8711 (accessed on 20 July 2018).

- Ibn, Ḥayyān. 1981. Crónica del califa ‘Abdarramān III an-Nāsir entre los años 912 y 942 (al-Muqtabis V). Translated by María Jesús Viguera, and Federico Corriente. Zaragoza: Instituto Hispano-Árabe de Cultura. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Esteban, Jorge. 1992. Castillos de Guadalajara. Madrid: Penthalón, vols. I, II. [Google Scholar]

- León Muñoz, Alberto, and Juan Francisco Murillo Redondo. 2009. El complejo civil tardoantiguo de Córdoba y su continuidad en el Alcázar Omeya. Madrider Mitteilungen 50: 399–432. [Google Scholar]

- Lévi-Provençal, Évariste. 1957. Instituciones y cultura. In España musulmana: Hasta la caída del Califato de Córdoba (711–1031 d. J.C.). Translated by Emilio García Gómez. Historia de España dirigida por R. Menéndez Pidal. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, vol. 9, pp. 3–330. [Google Scholar]

- Lewcock, Ronald. 1978. Materials and techniques. In Architecture of the Islamic World. Its History and Social Meaning. Edited by George Michell. London: Thames and Hudson, pp. 129–43. [Google Scholar]

- Manzano Moreno, Eduardo. 2006. Conquistadores, emires y califas. Los Omeyas y la formación de al-Andalus. Barcelona: Crítica. [Google Scholar]

- Márquez Bueno, Samuel, and Pedro Gurriarán Daza. 2008. Recursos formales y constructivos en la arquitectura militar almohade de al-Andalus. Arqueología de la arquitectura 5: 115–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molero García, Jesús. 2007. Entre el Islam y el Cristianismo: Fortificaciones y poblamiento en el sector suroccidental del Campo de Calatrava. In Saceruela, Puente de Culturas: Ciudad Real: Diputación Provincial. Saceruela (Ciudad Real): Ayuntamiento, D.L. [Google Scholar]

- Molero García, Jesús. 2016. Los primeros castillos de Ordenes Militares. Actividad edilicia y funcionalidad en la frontera castellana (1150–1195). In Ordenes Militares y Construcción de la Sociedad Occidental: (siglos XII–XV). Madrid: Sílex. [Google Scholar]

- Pavón Maldonado, Basilio. 1999. Tratado de arquitectura hispanomusulmana. II. Ciudades y fortalezas. Madrid: CSIC, vol. II. [Google Scholar]

- Peña Ruiz, Cristina, David Gallego Valle, Jesús Molero García, Francisco Javier Castilla Pascual, and David Sanz Martínez. 2017. Estudio de las técnicas y secuencia constructiva e histórica del recinto amurallado de Jorquera. Caracterización de materiales y levantamiento fotogramétrico. Albacete: Instituto de Estudios Albacetenses “Don Juan Manuel”, Excma, Albacete: Diputación de Albacete. [Google Scholar]

- Retuerce Velasco, Manuel, and Miguel Ángel Hervás Herrera. 2009. Calatrava la Vieja, primera sede de la Orden Militar de Calatrava. In El nacimiento de la orden de Calatrava. Primeros tiempos de expansión (siglos XII y XIII): actas del I Congreso Internacional de la Orden de Calatrava. Almagro: Instituto de Estudios Manchegos. [Google Scholar]

- Retuerce Velasco, Manuel, and Luis Alejandro García García. 2013. Intervención arqueológica en el sector de la Puerta de Daroca, en la muralla urbana de Huete (Cuenca). Un ejemplo hispano de murallas adosadas. In Fortificações e território na Península Ibérica e no Magreb (séculos VI a XVI). Lisboa: Ediçoes Colibri, Campo Arqueológico de Mértola. [Google Scholar]

- Sáez Lara, Fernando. 1993. Castillos, Fortificaciones y Recintos Amurallados de la Comunidad de Madrid. Edited by Alicia Cámara Muñoz, Javier Gutiérrez Marcos and Julio Valdeón Baruque. Guías de Patrimonio histórico 1. Madrid: Consejería de Educación y Cultura, Dirección General de Patrimonio CulturalSalvatierra, Vicente. s. f. Arqueología y Territorio Medieval. Revista Científica- Arqueología y Territorio Medieval. Accedido 23 de agosto de 2018. Available online: http://revistaselectronicas.ujaen.es/index.php/ATM DOI: 10.17561/aytm (accessed on 20 July 2018).

- Torres Balbás, Leopoldo. 1957. Arte hispanomusulmán. Hasta la caída del califato de Córdoba. In España Musulmana: Hasta la caída del Califato de Córdoba (711–1031 d. J.C.). Historia de España dirigida por R. Menéndez Pidal. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, pp. 331–788. [Google Scholar]

- Valdés Fernández, Fernando. 1988. Arqueología de Al-Andalus. De la conquista árabe a la extinción de las primeras Taifas. Historia General de España y América III: 545–617. [Google Scholar]

- Vallbé Bermejo, Joaquín. 1976. Notas de metrología hispano-árabe. El codo en la España musulmana. Al-Andalus, Revista de Estudios Árabes de Madrid y Granada 51: 339–54. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo Triano, Antonio. 2010. La ciudad califal de Madinat al-Zahra. Arqueología de su arquitectura. Córdoba: Almuzara. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo Triano, Antonio, and Ramón Fernández Barba. 2010. Una aproximación a las canteras de piedra calcarenita de Madinat al-Zahra’. Cuadernos de Madinat al-Zahra: Revista de difusión científica del Conjunto Arqueológico Madinat al-Zahra 7: 405–19. [Google Scholar]

- Viguera Molins, María Jesús. 2000. La Taifa de Toledo. In Entre el Califato y la Taifa. Mil años del Cristo de la Luz. Actas del Congreso Internacional, Toledo, 1999. Toledo: Asociación de Amigos del Toledo Islámico, pp. 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Zozaya Stabel-Hansen, Juan. 1991. Fortification Building in al-Andalus. In Spanien und der Orient im frühen und Hohem Mittelalter. Kolloquium Berlin, 1991. Madrider Beiträge. Wiesbaden: Band, vol. 24, pp. 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Zozaya Stabel-Hansen, Juan. 2009. VI-Arquitectura Militar en Al-Andalus. XELB 9, Actas do 6o Encontro de Arqueología do Algarve, Homenagem a José Luís de Matos. pp. 75–126. Available online: digital.csic.es/bitstream/10261/13849/1/navarro_cora_tudmir.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2018).

- Zozaya Stabel-Hansen, Juan, Juan Manuel Rojas Rodríguez-Malo, and J. Ramón Villa González. 2005. El alcázar medieval de Toledo. In Congreso Espacios Fortificados de la Provincia de Toledo. Toledo: Diputación Provincial, pp. 199–230. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gil Crespo, I.J.; Bru Castro, M.Á.; Gallego Valle, D. Fortified Construction Techniques in al-Ṭagr al-Awsaṯ, 8th–13th Centuries. Arts 2018, 7, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040055

Gil Crespo IJ, Bru Castro MÁ, Gallego Valle D. Fortified Construction Techniques in al-Ṭagr al-Awsaṯ, 8th–13th Centuries. Arts. 2018; 7(4):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040055

Chicago/Turabian StyleGil Crespo, Ignacio Javier, Miguel Ángel Bru Castro, and David Gallego Valle. 2018. "Fortified Construction Techniques in al-Ṭagr al-Awsaṯ, 8th–13th Centuries" Arts 7, no. 4: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040055

APA StyleGil Crespo, I. J., Bru Castro, M. Á., & Gallego Valle, D. (2018). Fortified Construction Techniques in al-Ṭagr al-Awsaṯ, 8th–13th Centuries. Arts, 7(4), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040055