Decolonizing Photography

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Photography and Colonial Language

2.1. Define Colonialism

2.2. Shooting

2.3. Kodak Advertisement

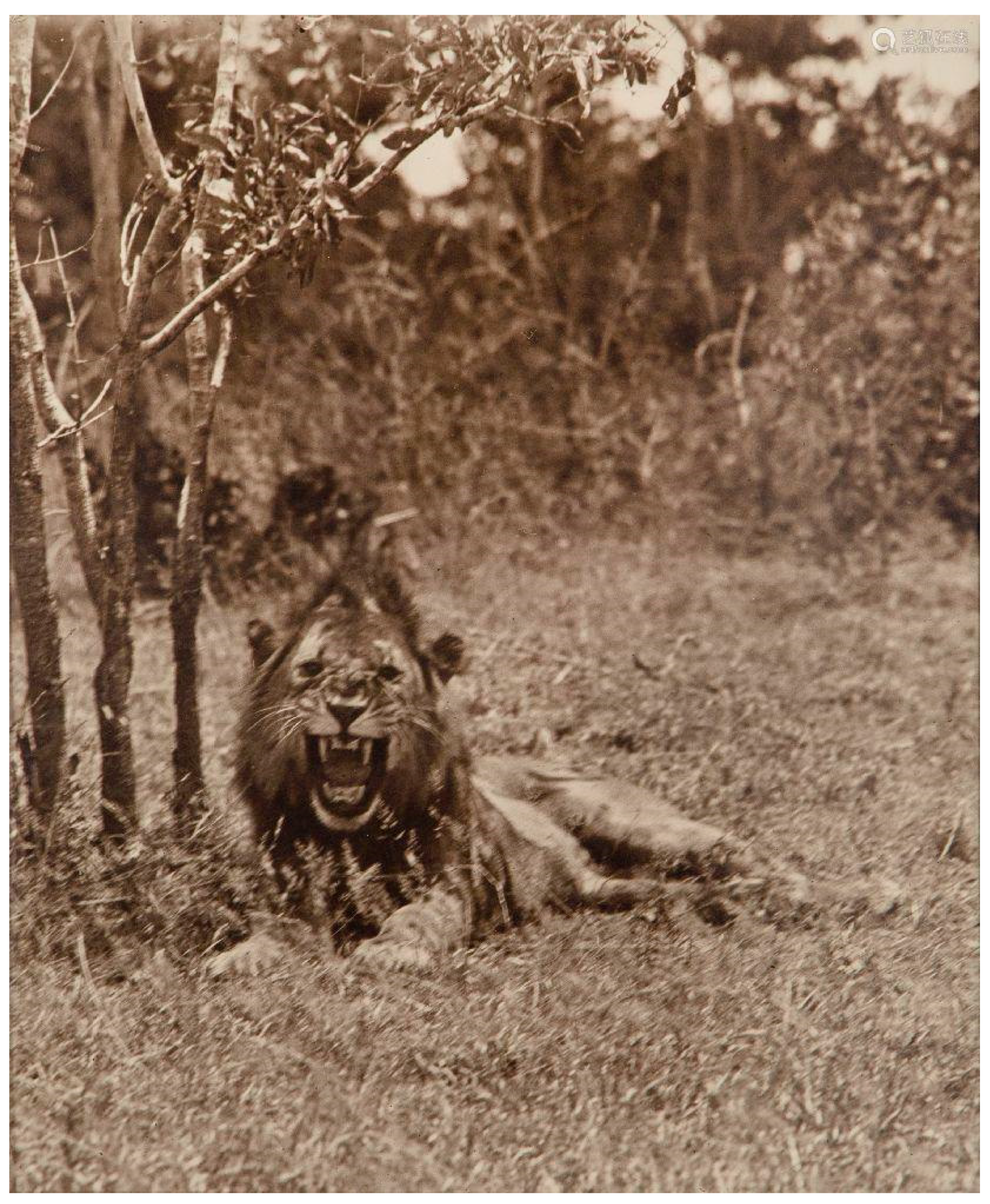

2.4. “Wounded Lion” by Arthur Radclyffe Dugmore

3. Contemporary Photography: Decolonizing by Challenging Anthropocentrism

3.1. Define Anthropocentrism and Decolonization

- Rediscovery and Recovery. This is where one rediscovers their culture by connecting with what remains.

- Mourning. This step involves grief and anger. Laenui notes that lashing out may be part of this stage.

- Dreaming. This is where the new possibilities of a different social order are imagined. Laenui poetically likens this phase to a fetus developing in the womb.

- Commitment. In this stage, a mission statement and/or clear direction forward is established. It is essential that this commitment comes from a consensus among the colonized people.

- Action. This is the last step where actions are taken. Laenui writes “The responsive action is one for survival. The action called for in the fifth phase of decolonization is not a reactive but a proactive step taken based on consensus of the people” (Laenui 2000, p. 158).

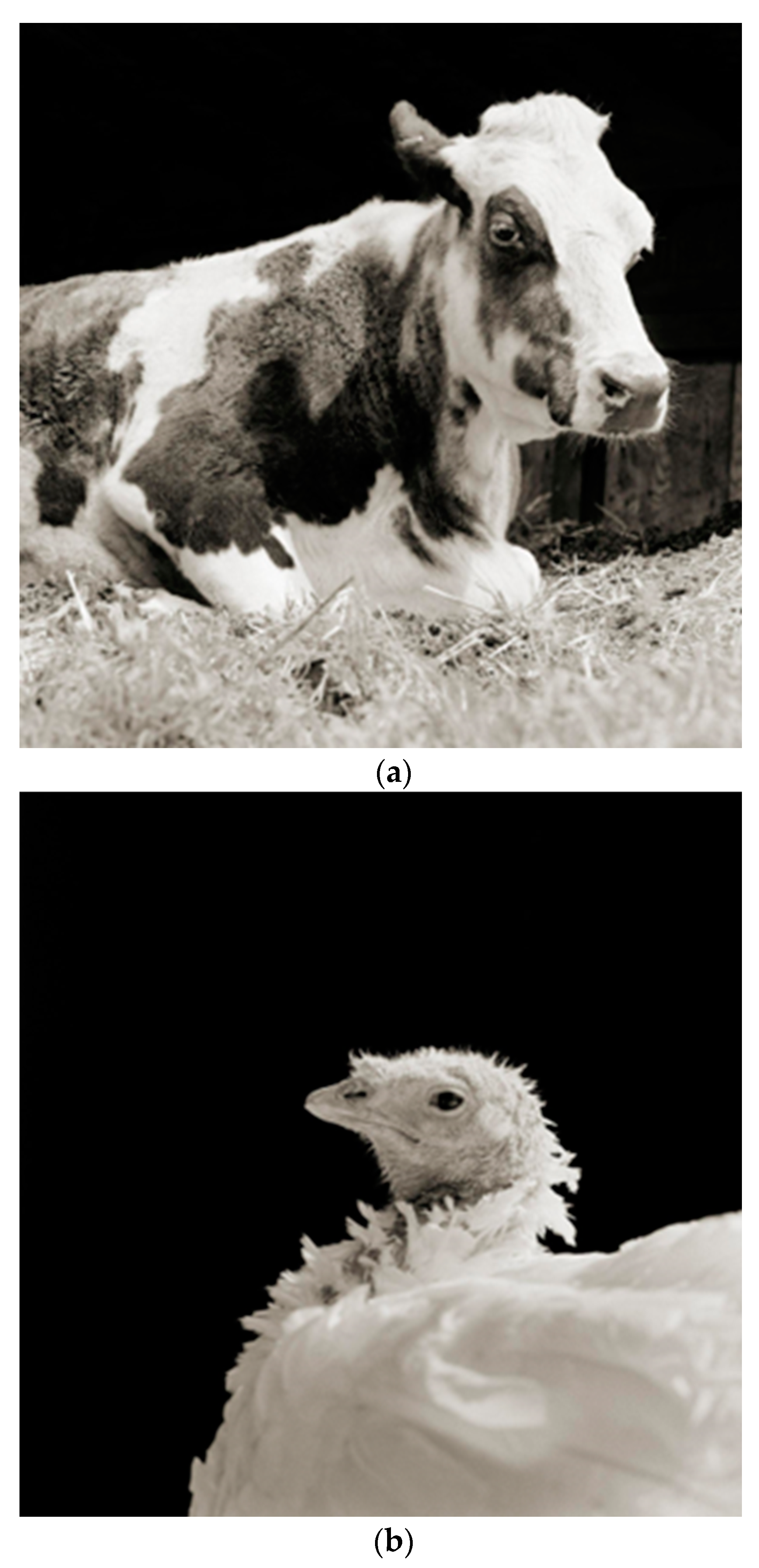

3.2. We Animals

3.3. Allowed to Grow Old

3.4. Thirty Times A Minute

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | This definition of colonization draws from Smith (2021); Hooks (1992), and multiple essays found in the anthology “Imagining Decolonization” (Kiddle 2020). (Please see the bibliography section for the full list of authors and essay titles found in this anthology). |

| 2 | Recently there has been a push from photographers, historians, and scholars to remove this language and replace it with more accurate descriptions. In particular, the terms “master” and “slave” have received quite a bit of attention. Here are three examples.

|

| 3 | Language usage that shapes meaning has been widely researched through different academic lenses in the fields of business, computer science, philosophy, psychology, marketing, and sociology. Within photography, Andy Grundberg offers a clear summary of how structuralist linguistic theory has shaped postmodernism (Grundberg 2019, p. 245). |

| 4 | James Ryan also discusses Dugmore’s photography in his essay “Talking Pictures: Interviews with Photographers Around The World” (Ryan 2000, p. 214–15). |

| 5 | In Decolonizing Methodologies, Linda Tuhiwai Smith succinctly explains “… colonialism is but one expression of imperialism” (Smith 2021, p. 23). |

| 6 | In this context, the terms “borrowing” and “applying” are attributed to an insight by Dr. Nik Taylor (Personal communication, 30 March 2023). |

| 7 | This definition is synthesized and adapted from Weitzenfeld and Joy (2014). |

| 8 | A few important texts include “Decolonizing Methodologies 3rd Edition” (Smith 2021); “Reclaiming Indigenous Voice and Vision” (Battiste 2000); and “Imagining Decolonization” (Kiddle 2020). |

References

- Alloula, Malek. 1986. The Colonial Harem. Translated by Myrna Godzich, and Wlad Godzich. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, Roland. 1981. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Translated by Richard Howard. New York: Hill and Wang. [Google Scholar]

- Battiste, Marie. 2000. Reclaiming Indigenous Voice and Vision. Vancouver: UBC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bear, Theresa. 2020. It’s Time to End the Terms ‘Slave’ and ‘Master’ in Photography. PetaPixel, June 6. Available online: https://petapixel.com/2020/06/06/its-time-to-end-the-terms-slave-and-master-in-photography/ (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Borge, Michelle. 2019. Documentary Photography Reconsidered: History, Theory and Practice. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Brower, Matthew. 2011. Developing Animals: Wildlife and Early American Photography. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, Teju. 2019. On Photography: When the Camera Was a Weapon of Imperialism. (And When It Still Is.). The New York Times Magazine, February 6. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/06/magazine/when-the-camera-was-a-weapon-of-imperialism-and-when-it-still-is.html (accessed on 12 February 2022).

- Cooke, Julia. 2016. Thirty Times A Minute: Photography by Colleen Plumb. Virginia Quarterly Review 92: 128–46. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1989. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum 1989: 139–67. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, J. Keri, and Lisa A. Kramer. 2018. Challenging the Iconography of Oppression in Marketing: Confronting Speciesism Through Art and Visual Culture. Journal of Animal Ethics 8: 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deckha, Maneesha. 2012. Toward a Postcolonial, Posthumanist Feminist Theory: Centralizing Race and Culture in Feminist Work on Nonhuman Animals. Hypatia 27: 527–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeRoo, Rebecca J. 2002. Colonial Collecting: French Women and Algerian Cartes Postales. In Colonialist Photography: Imag(in)ing Race and Place. Edited by Eleanor Hight and Gary Sampson. New York: Routledge, pp. 159–71. [Google Scholar]

- Dugmore, Arthur Radclyffe. 1910. Camera Adventures in the African Wild. New York: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, Bianca, and Jennie Smeaton. 2020. Introduction. In Imagining Decolonisation. Edited by Rebecca Kiddle. Wellington: Bridget Williams Books, pp. iii–ix. [Google Scholar]

- Greco, Brian J., Cheryl L. Meehan, Jennifer L. Heinsius, and Joy A. Mensch. 2017. Why Pace? The Influence of Social, Housing, Management, Life History, and Demographic Characteristics on Locomotor Stereotypy in Zoo Elephants. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 194: 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundberg, Andy. 2019. The Crisis of the Real: Photography and Postmodernism. In The Photography Reader: History and Theory, 2nd ed. Edited by Liz Wells. New York: Routledge, pp. 242–59, [First edition 2003, Originally published in The Crisis of the Real, 1990]. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, Donna. 1984. Teddy Bear Patriarchy: Taxidermy in the Garden of Eden, New York City, 1908–1936. Social Text 11: 20–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hight, Eleanor M., and Gary D. Sampson. 2002. Introduction: Photography, ‘Race’, and Post-Colonial Theory. In Colonialist Photography: Imag(in)ing Race and Place. Edited by Eleanor Hight and Gary Sampson. New York: Routledge, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, Robert. 2009. Seizing The Light: A Social History of Photography, 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Hooks, Bell. 1992. Black Looks: Race and Representation. Boston: South End Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hosey, Geoff, Vickey Melfi, and Shelia Pankhurst. 2013. Glossary. In Zoo Animals: Behavior, Management, and Welfare, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Moana. 2020. Where To Next? Decolonisation and the Stories in the Land. In Imagining Decolonisation. Edited by Rebecca Kiddle. Wellington: Bridget Williams Books, pp. 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson, Dale. 2006. Against Zoos. In In Defense of Animals: The Second Wave. Edited by Peter Singer. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 132–143. [Google Scholar]

- Kiddle, Rebecca. 2020. Colonisation Sucks for Everyone. In Imagining Decolonisation. Edited by Rebecca Kiddle. Wellington: Bridget Williams Books, pp. 30–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs, Arpad. 2015. Sit, Stay, Pose: Photographing Animals. In Animals in Photographs. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, pp. 6–15. [Google Scholar]

- Krauss, Rosalind. 1982. Photography’s Discursive Spaces: Landscape/View. Art Journal 42: 311–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laenui, Poka. 2000. Process of Decolonization. In Reclaiming Indigenous Voice and Vision. Edited by Marie Battiste. Vancouver: UBC Press, pp. 150–60. [Google Scholar]

- Landau, Paul S. 1998. Hunting with Gun and Camera: A Commentary. In The Colonizing Camera: Photographs in the Making of Namibian History. Edited by Wolfram Hartmann, Jeremy Silvester and Patricia Hayes. Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press, pp. 151–55. [Google Scholar]

- Leshko, Isa. 2023. Isa Leshko Allowed to Grow Old Artist Statement. Available online: https://www.isaleshko.com/allowed-to-grow-old-project-info (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Lippard, Lucy R. 2019. DoubleTake: The Diary Of A Relationship With An Image. In The Photography Cultures Reader: Representation, Agency, and Identity. Edited by Liz Wells. New York: Routledge, pp. 42–52. First published 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lorde, Audre. 1984. Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Berkeley: Crossing Press. [Google Scholar]

- Malamud, Randy. 2012. An Introduction to Animals and Visual Culture. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- McArthur, JoAnne. 2023. JoAnne McArthur About Bio. Available online: https://joannemcarthur.com/about/ (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Mercier, Ocean Ripeka. 2020. What is Decolonsation? In Imagining Decolonisation. Edited by Rebecca Kiddle. Wellington: Bridget Williams Books, pp. 10–29. [Google Scholar]

- O’Rielly-Conlin, Jessie. 2021. Decolonizing the Language of Photography. Photographers without Borders, June 21. Available online: https://www.photographerswithoutborders.org/online-magazine/decolonizing-the-language-of-photography (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Parnell-Brookes, Jason. 2020. Canon Has Officially Dropped ‘Master’ and ‘Slave’ Terms. Fstoppers, July 2. Available online: https://fstoppers.com/gear/canon-has-officially-dropped-master-and-slave-terms-497389 (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Plumb, Colleen. 2023. Colleen Plumb: Thirty Times A Minute. Available online: https://colleenplumb.com/thirtytimesaminute-video-htm/ (accessed on 31 March 2023).

- Ryan, James R. 2000. ‘Hunting with the Camera’: Photography, Wildlife and Colonialism in Africa. In Animal Spaces, Beastly Places: New Geographies of Human-Animal Relations. Edited by Chris Philo and Chris Wilbert. London: Routledge, pp. 205–22. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Linda T. 2021. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, 3rd ed. New York: Zed Books. [Google Scholar]

- Sontag, Susan. 1977. On Photography. New York: Picador. [Google Scholar]

- Szarkowski, John. 1978. Mirrors and Windows: American Photography Since 1960. New York: The Museum of Modern Art. [Google Scholar]

- Tagg, John. 2019. Evidence, Truth and Order: Photographic Records and the Growth of the State. In The Photography Reader: History and Theory, 2nd ed. Edited by Liz Wells. New York: Routledge, pp. 307–10, [First Edition 2003, Also Published in The Burden of Representation: Essays on Histories and Photographies, 1988]. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Amanda. 2020. Pākehā and Doing the Work of Decolonisation. In Imagining Decolonisation. Edited by Rebecca Kiddle. Wellington: Bridget Williams Books, pp. 42–54. [Google Scholar]

- Watt, Yvette. 2011. Making Animals Matter: Why the Art World Needs to Rethink the Representation of Animals. In Considering Animals: Contemporary Studies in Human-Animal Relations. Edited by Carol Freeman, Elizabeth Leane and Yvette Watt. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing, pp. 119–134. [Google Scholar]

- Weitzenfeld, Adam, and Melanie Joy. 2014. An overview of anthropocentrism, humanism, and speciesism in critical animal theory. Counterpoints 448: 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- What Is Animal Photojournalism? 2023. We Animals Media. Available online: https://weanimalsmedia.org/about/what-is-animal-photojournalism/ (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Wisch, Rebecca F. 2003. Overview of the Lacey Act. Animal Legal & Historical Center. Available online: https://www.animallaw.info/intro/lacey-act (accessed on 3 March 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Johnstone, M.S. Decolonizing Photography. Arts 2023, 12, 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12040140

Johnstone MS. Decolonizing Photography. Arts. 2023; 12(4):140. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12040140

Chicago/Turabian StyleJohnstone, Mary Shannon. 2023. "Decolonizing Photography" Arts 12, no. 4: 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12040140

APA StyleJohnstone, M. S. (2023). Decolonizing Photography. Arts, 12(4), 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12040140