Post-Byzantine Cretan Icon Painting: Demand and Supply Revisited

Abstract

1. Introduction

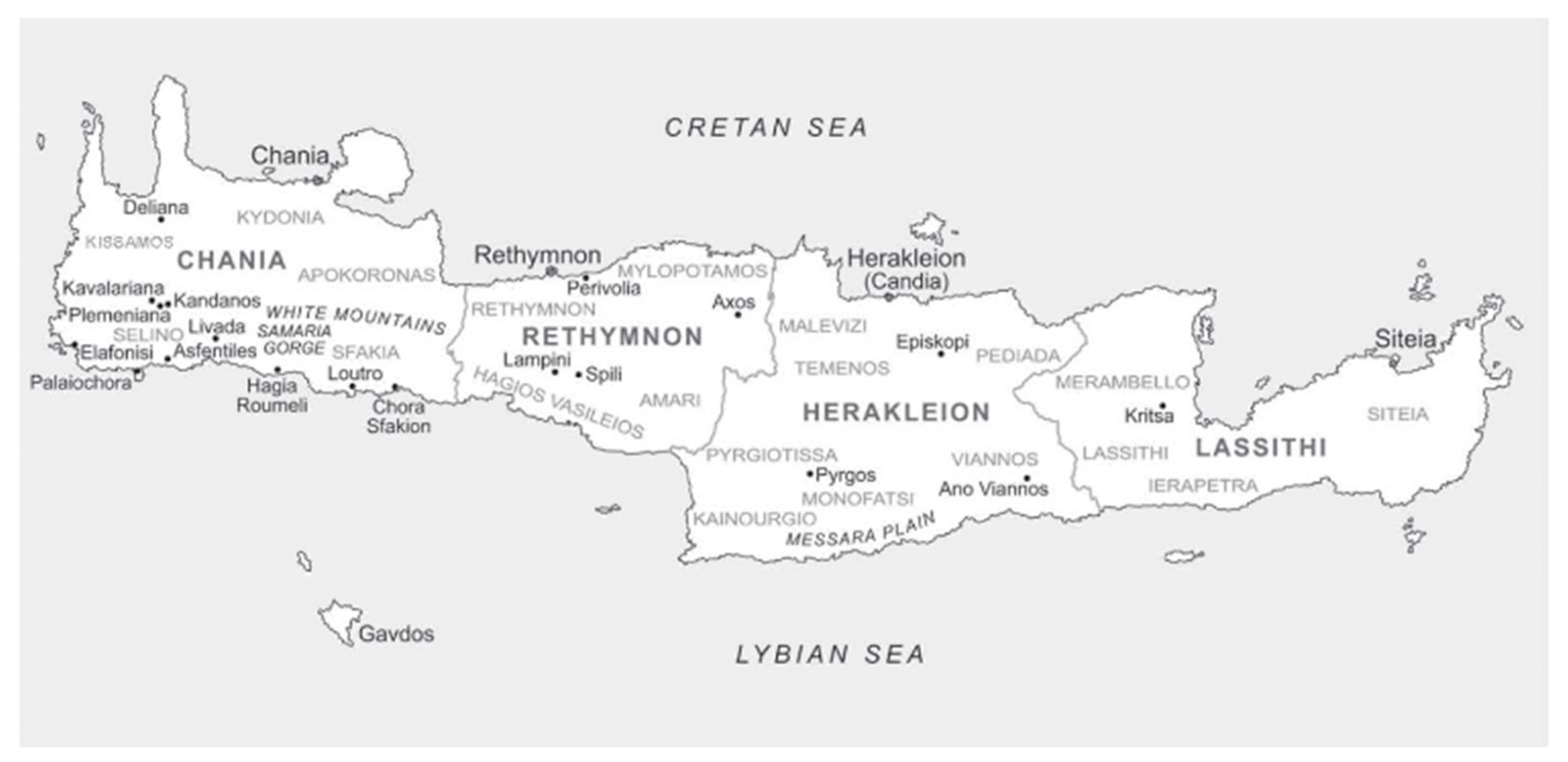

2. The Contract and Its Context

3. The Painters

4. The Commission and Its Value

Although in three separate parts, the contract seems to be interlinked; in other words, this was a single commission with a division of labour.

It could be suggested that each painter had a ‘specialisation’.

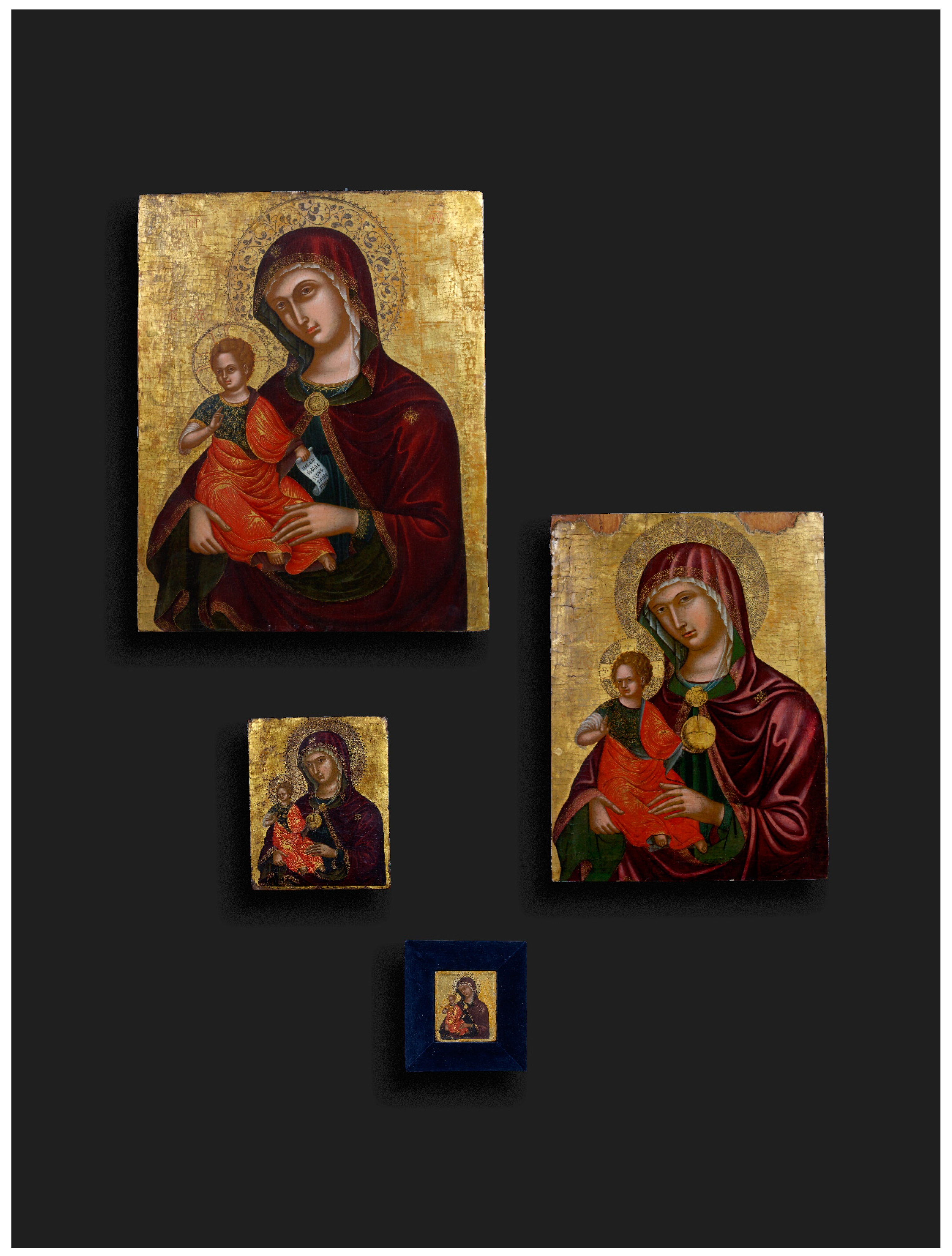

The contract refers to ‘first’, ‘second’ and ‘third’ types of icons.

The advance payment each painter received differs.

Money

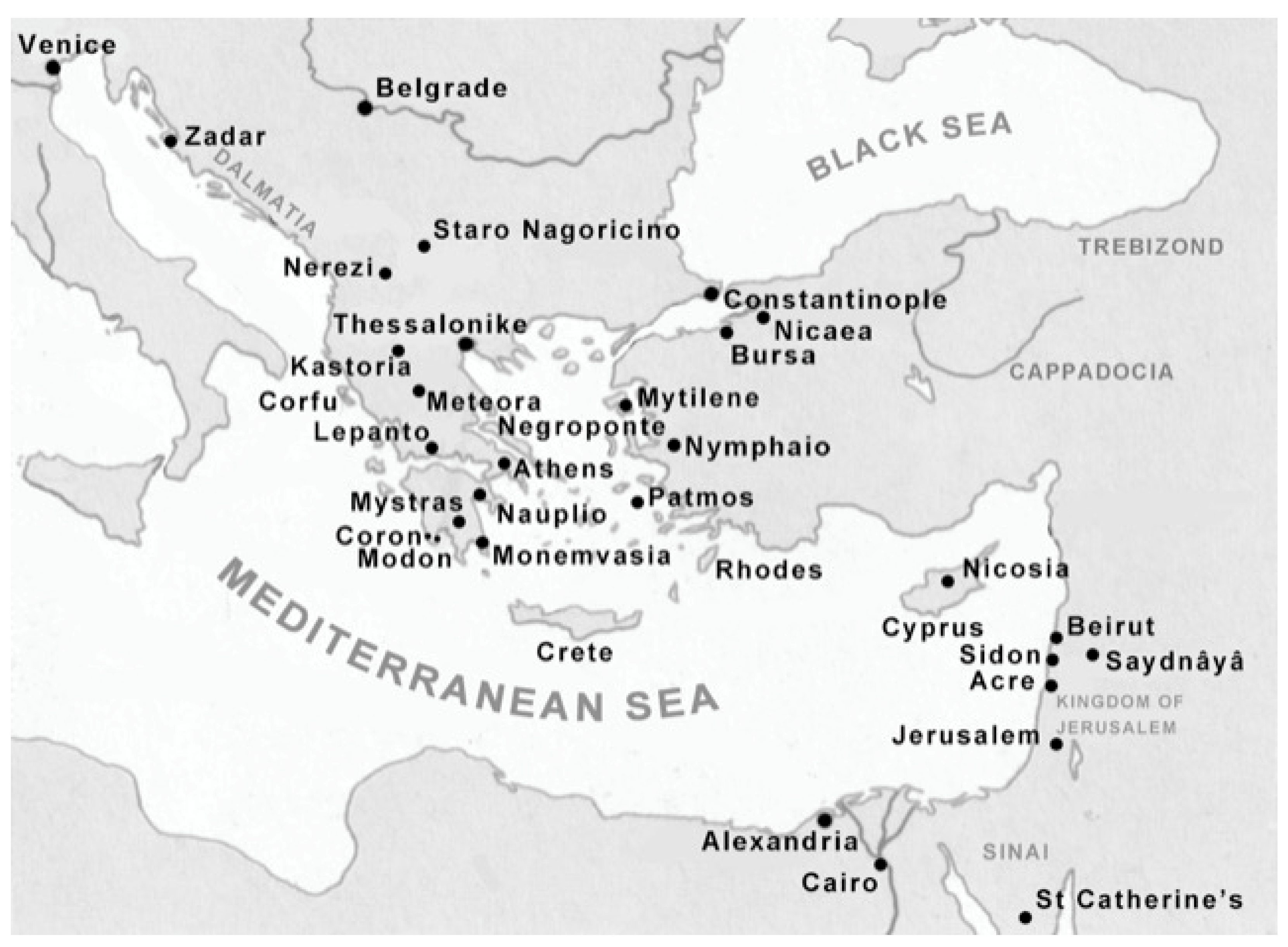

5. Icon Market

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Document Originally Published in (Cattapan 1972, pp. 211–12, no. 6)

Appendix A.2. Translated in (Richardson et al. 2007, pp. 371–72, 3.5.3 (1))

Appendix A.3. Document Originally Published in (Cattapan 1972, p. 212, no. 7)

Appendix A.4. Translated in (Richardson et al. 2007, p. 372, 3.5.3 (2))

Appendix A.5. Document Originally Published in (Cattapan 1972, pp. 212–13, no. 8)

Appendix A.6. Translated in (Richardson et al. 2007, pp. 372–73, 3.5.3 (3))

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. Document Originally Published in (Cattapan 1972, p. 211, no. 4)

Appendix B.2. Translated into English by Angeliki Lymberopoulou and Rembrandt Duits

| 1 | I am among those who have benefitted from the evidence that the close reading of the document provides regarding the production and dissemination of Cretan post-Byzantine icons in Western Europe, and I have assessed it in two of my previous publications (Lymberopoulou 2007a, 2023). |

| 2 | ‘Hellenic patriotism’ was underlined by Georgios Gemistos Plethon (c. 1360–1452) in his address to the Emperor Manuel II (r. 1391–1425), see (Kazhdan 1991, vol. 3, p. 1685). In fact, ‘Byzantium’ a term coined in 1557 by the German scholar Hieronymus Wolf (1516–1580), is an acknowledgement of the Greek origins of the long-lasting Empire, see (Evans 2004, p. 5). |

| 3 | The historic, socio-economic, religious and cultural development on Venetian Crete over the course of more than four and a half centuries has attracted a lot of interest in scholarship, which intensified in the second half of the twentieth century, following Manolis Chatzidakis’s publications, as mentioned at the beginning of this paper. For a general overview of Venetian Crete’s organisation and living circumstances, with further bibliography, see indicative (Maltezou 1988, 1991; McKee 2000; Georgopoulou 2001; Lymberopoulou 2007a, 2010a, 2010b, 2013; Gasparis 2020). |

| 4 | The information on the origins of the two dealers is provided in (Cattapan 1972, pp. 214–15) without, however, any further indication of its source. |

| 5 | Only scant information exists on the notaries of Candia, a rich field that still awaits systematic research: https://asve.arianna4.cloud/patrimonio/0dc6c8bc-6000-4a3e-8c9c-1dc7365334ae/433-%C2%ABnotai-di-candia%C2%BB-1961-1992 (accessed 9 June 2023). I would like to thank Charalambos Gasparis for providing this information. |

| 6 | Nicolò had a son, Ioanni (Tzani, Tzouane) Gripioti, who was an important painter in Candia in the sixteenth century; see (Constantoudaki 1976). |

| 7 | My price conversions differ from those in (Vassilaki 2009b, p. 313). |

| 8 | For painting gold brocade, see (Duits 2008, esp. 5–13). |

| 9 | (Vincent 2007, pp. 285–95), in his discussion of Cretan money, notes that soldo and soldino were the same on the island. For the purposes of this present paper, I would like to note that the conversions I have provided, based on the invaluable work by (Vincent 2007), are very broad, primarily aiming at placing the contract in its wider financial context and therefore can only be regarded as an oversimplification of a very complicated monetary system. |

| 10 | There were different types of red: vermillion (a bright red) was a mineral-based, but still not very expensive, pigment; the red obtained from fabrics was red lake (a dark, purplish red), which was used most frequently for glazing (painting in thin layers). I would like to thank Rembrandt Duits for providing this information. |

| 11 | My translation of the document provided in Appendix B differs from the reading in (Vassilaki 2009b, p. 311) and, as such, Tajapiera would have produced either 210 or a maximum of 217 (in one 31-day month) underdrawings, not 350. |

| 12 | The topic has attracted a lot of attention and discussion; see indicative (Gratziou 2012; Drandaki 2014). See also (Bacci 2020; Lymberopoulou 2023). |

| 13 | I would like to thank Yanni Petsopoulos for this observation, which he very kindly shared with me in an email communication (14 June 2023). |

| 14 | While Evelyn Welch suggests that fairs were mostly composed of local traders, she nevertheless mentions that the traded goods were not (Welch 2005, p. 173); in other words, one way or another, travel and transportation was an important and integral part of fairs. |

| 15 | (McKee 2000, p. 20) mentions that Crete was approximately a month away from Venice by galley, but without providing a basis for this time frame. |

| 16 | El Greco owned a copy of the second, enlarged edition of Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects, published in 1568: (De Vere 1996). On Vasari’s views on the Greek style: (Richardson et al. 2007, pp. 376–378, 3.5.7). For El Greco’s comment: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/12/081218132252.htm (accessed 15 June 2023); published by (Hadjinicolaou 2008); for a general overview of El Greco’s Cretan artistic roots, see (Lymberopoulou 2012). |

References

- Angelidi, Christine, and Titos Papamastorakis. 2000. Mother of God Representations of the Virgin in Byzantine Art. Edited by Maria Vassilaki. Benaki Museum: Athens, Skira Editore: Milan, pp. 373–87. [Google Scholar]

- Bacci, Michele. 2020. On the Prehistory of Cretan Icon Painting. Frankokratia 1: 108–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltoyanni, Chrysa. 1994. Εικόνες Μήτηρ Θεού Βρεφοκρατούσα στην Ενσάρκωση και το Πάθος. Athens: Adam. [Google Scholar]

- Casson, Lionel. 1951. Speed Sail of Ancient Ships. Transactions of the American Philological Association 82: 136–48. Available online: https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Journals/TAPA/82/Speed_under_Sail_of_Ancient_Ships*.html (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Cattapan, Mario. 1972. Nuovi Elenchi e Documenti dei Pittori in Crtea dal 1300 al 1500. Θησαυρίσματα 9: 202–35. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzidakis, Manolis. 1974a. Essai sur l’ école dite ‘Italogrecque’ précédé d’ une note sur les rapports de l’ art vénitien avec l’ art crétois jusqu’ à 1500. In Venezia e il Levante fino al secolo XV. Edited by Agostino Pertusi. Florence: Fondazione Giorgio Cini., vol. 2, pp. 69–124. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzidakis, Manolis. 1974b. Les débuts de l’école crétoise et la question de l’école dite italogrecque. In Μνημόσυνον Σοφίας Aντωνιάδη. Venice: Hellenic Insitute for Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Studies, pp. 169–211. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzidakis, Manolis. 1977. La peinture des ‘Madonneri’ ou ‘vénéto-crétoise’ et sa destination. In Aspetti e problemi Atti del II Convengno internazionale di storia della civiltà veneziana. Edited by Hans-Georg Beck. Florence: Manoussos Manoussacas and Agostino Pertusi, pp. 673–90. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzidakis, Manolis. 1987. Έλληνες Ζωγράφοι μετά την Άλωση (1450–1830). Με Εισαγωγή στην Ιστορία της Ζωγραφικής της Εποχής. Athens: Κέντρο Νεοελληνικών Ερευνών. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzidakis, Manolis, and Eugenia Drakopoulou. 1997. Έλληνες Ζωγράφοι μετά την Άλωση (1450–1830). Με Εισαγωγή στην Ιστορία της Ζωγραφικής της Εποχής. Athens: Κέντρο Νεοελληνικών Ερευνών. [Google Scholar]

- Constantoudaki, Maria. 1973. «Oι Ζωγράφοι του Χάνδακος κατά το πρώτο μισό του 16ου αιώνος οι μαρτυρούμενοι εκ των νοταριακών αρχείων». Thesaurismata 10: 291–380. [Google Scholar]

- Constantoudaki, Maria. 1976. «Aνέκδοτα Έγγραφα για το Ζωγράφο του 16ου αι. Ιωάννη Γριπιώτη». Thesaurismata 13: 284–96. [Google Scholar]

- De Vere, G., trans. 1996. Giorgio Vasari. In Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects. 2 vols. London: Macmillan and Co., Ltd. & The Medici Society, Ltd., pp. 1912–15. [Google Scholar]

- Derbes, Anne, and Amy Neff. 2004. Itlay, the Medicant Orders, and the Byzantine Shere. In Byzantium Faith and Power (1261–1557). Edited by Helen Evans. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, pp. 449–61. [Google Scholar]

- Dermitzaki, Argyri. 2021. Shrines in a Fluid Space: The Shaping of New Holy Sites in the Ionian Islands, the Peloponnese and Crete under Venetian Rule (14th–16th Centuries). Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Drandaki, Anastasia. 2014. A Maniera Greca: Content, Content and Transformation of a Term. Studies in Iconography 35: 39–72. [Google Scholar]

- Duits, Rembrandt. 2008. Gold Brocade and Renaissance Painting A Study in Material Culture. London: Pindar Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duits, Rembrandt. 2011. “Una icona pulchra”: The Byzantine icons od Cardinal Pietro Barbo. In Mantova e il Rinascimento italiano: Studi in onore di David S. Chambers. Edited by Philippa Jackson and Guido Rebecchini. Mantua: Sometti, pp. 127–42. [Google Scholar]

- Duits, Rembrandt. 2013. Byzantine Icons in the Medici Collection. In Byzantine Art and Renaissance Europe. Edited by Angeliki Lymberopoulou and Rembrandt Duits. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 157–88. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Helen, ed. 2004. Byzantium: Faith and Power (1261–1557). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Gasparis, Charalambos. 2020. Venetian Crete. The Historical Context. In Hell in the Byzantine World: A History of Art and Religion in Venetian Crete and the Eastern Mediterranean, Volume 1 Essays. Edited by Angeliki Lymberopoulou. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 60–116. [Google Scholar]

- Georgopoulou, Maria. 2001. Venice’s Mediterranean Colonies: Architecture and Urbanism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gratziou, Olga. 2012. A La Latina. Ζωγράφοι Εικόνων Προσανατολισμένοι Δυτικά. Δελτίον Χριστιανικής Aρχαιολογικής Εταιρείας 12: 357–68. [Google Scholar]

- Hadjinicolaou, Nicos. 2008. La defensa del arte bizantino por El Greco: Notas sobre una paradoja. En Archivo Español de Arte 323: 217–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazhdan, Alexander P., ed. 1991. The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. 3 vols. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lymberopoulou, Angeliki. 2003. The Madre della Consolazione icon in the British Museum: Post-Byzantine Painting, Painters, and Society on Crete. Jahrbuch der Österreichischen Byzantinistik 53: 239–55. [Google Scholar]

- Lymberopoulou, Angeliki. 2006. The Church of the Archangel Michael at Kavalariana: Art and Society on Fourteenth-Century Venetian-Dominated Crete. London: Pindar Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lymberopoulou, Angeliki. 2007a. Audiences and Markets for Cretan Icons. In Viewing Renaissance Art. Edited by Kim W. Woods, Carol M. Richardson and Angeliki Lymberopoulou. New Haven and London: Yale University Press in association with the Open University, pp. 171–206. [Google Scholar]

- Lymberopoulou, Angeliki. 2007b. The Painter Angelos and post-Byzantine Art. In Locating Renaissance Art. Edited by Carol M. Richardson. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, pp. 174–210. [Google Scholar]

- Lymberopoulou, Angeliki. 2010a. Fourteenth-century Regional Cretan Church Decoration: The Case of the Painter Pagomenos and his Clientele. In Towards Rewriting? New Approaches to Byzantine Art and Archaeology. Edited by Piotr L. Grotowksi and Sławomir Skrzyniarz. Warsaw: The Polish Society of Oriental Art, pp. 159–75. [Google Scholar]

- Lymberopoulou, Angeliki. 2010b. Late and Post-Byzantine Art under Venetian Rule: Frescoes versus Icons, and Crete in the Middle. In A Companion to Byzantium. Edited by Liz James. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 351–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lymberopoulou, Angeliki. 2012. From Candia to Toledo: El Greco and his Art. In Art and Visual Culture 1100–600. Medieval to Renaissance. Edited by Kim W. Woods. London: Tate Publishing in association with the Open University, pp. 282–325. [Google Scholar]

- Lymberopoulou, Angeliki. 2013. Regional Byzantine Monumental Art from Venetian Crete. In Byzantine Art and Renaissance Europe. Edited by Angeliki Lymberopoulou and Rembrandt Duits. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 61–99. [Google Scholar]

- Lymberopoulou, Angeliki. 2023. Maniera Greca and Renaissance Europe: More than meets the eye. Paper presented at Global Byzantium, papers from the 50th Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies, Birmingham, UK, March 25–27; Edited by Leslie Brubaker, Rebecca Darley and Daniel Reynolds. London: Routledge, pp. 155–71. [Google Scholar]

- Lymberopoulou, Angeliki, and Rembrandt Duits, eds. 2013. Byzantine Art and Renaissance Europe. Farnham: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Maltezou, Chryssa A. 1988. H Κρήτη στη Διάρκεια της Περιόδου της Βενετοκρατίας (1211–1669). In Κρήτη: Ιστορία καί Πολιτισμός. Edited by Ν. Μ. Παναγιωτάκης. Herakleion. vol. 3, pp. 105–61. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/37090561/%CE%91%CE%BD%CE%B1%CE%B3%CF%81%CE%B1%CF%86%CE%AE_%CE%B4%CE%B7%CE%BC%CE%BF%CF%83%CE%B9%CE%B5%CF%85%CE%BC%CE%AC%CF%84%CF%89%CE%BD_%CE%A7%CF%81%CF%8D%CF%83%CE%B1%CF%82_%CE%91_%CE%9C%CE%B1%CE%BB%CF%84%CE%AD%CE%B6%CE%BF%CF%85_List_of_publications_of_Chryssa_A_Maltezou (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Maltezou, Chryssa. 1991. The Historical and Social Context. In Literature and Society in Renaissance Crete. Edited by David Holton. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 17–47. [Google Scholar]

- McKee, Sally. 1993. Greek Women in Latin households of fourteenth-century Venetian Crete. Journal of Medieval History 19: 229–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, Sally, ed. 1998. Wills from Late Medieval Venetian Crete 1312–1420. 3 vols. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. [Google Scholar]

- McKee, Sally. 2000. Uncommon Dominion. Venetian Crete and the Myth of Ethnic Purity. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Newall, Diana. 2013. Candia and Post-Byzantine Icons in the Late Fifteenth-century Europe. In Byzantine Art and Renaissance Europe. Edited by Angeliki Lymberopoulou and Rembrandt Duits. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 101–34. [Google Scholar]

- Papadaki, Irene. 2016. From Crete to Venice: The Transfer of the Archives. Thesaurismata 46: 235–306. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, Carol, Kim W. Woods, and Michael W. Franklin, eds. 2007. Renaissance Art Reconsidered. An Anthology of Primary Sources. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing in the association with the Open University. [Google Scholar]

- Vassilaki, Maria. 1995. Aπό τους εικονογραφικούς οδηγούς στα σχέδια εργασίας των μεταβυζαντινών ζωγράφων. Το τεχνολογικό υπόβαθρο της Βυζαντινής εικονογραφίας. Athens: Foundation Goulandri-Chorn. [Google Scholar]

- Vassilaki, Maria. 2009a. ‘On the Technology of Post-Byzantine Icons’ in Maria Vassilaki. In The Painter Angelos and Icon-Painting in Venetian Crete. Farnham: Ashgate Variorum, pp. 333–44, no. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Vassilaki, Maria. 2009b. The Painter Angelos and Icon-Painting in Venetian Crete. Farnham: Ashgate Variorum. [Google Scholar]

- Vassilaki, Maria. 2009c. ‘Workshop Practices and Working Drawings of Icon-painters’ in Maria Vassilaki. In The Painter Angelos and Icon-Painting in Venetian Crete. Farnham: Ashgate Variorum, pp. 317–32, no. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent, Alfred. 2007. Money and Coinage in Venetian Crete, c. 1400–669: An Introduction. Thesaurismata 37: 267–36. [Google Scholar]

- Voulgaropoulou, Margarita. 2019. From Domestic Devotion to the Church Altar: Venerating Icons in the Late Medieval and Early Modern Adriatic. Religions 10: 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voulgaropoulou, Margarita. 2021. A ‘Lost’ Panel and a Missing Link: Angelos Bitzamanos and the Case of the Scottivoli Altarpiece for the Church of San Francesco Delle Scale in Ancona. Arts 10: 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, Evelyn. 2005. Shopping in the Renaissance. Consumer cultures in Italy 1400–600. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, Kim W. 2013. Byzantine Icons in the Netherlands, Bohemia and Spain during the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries. In Byzantine Art and Renaissance Europe. Edited by Angeliki Lymberopoulou and Rembrandt Duits. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 135–55. [Google Scholar]

- Zachariadou, Elizabeth A. 1983. Trade ad Crusade Venetian Crete and the Emirates of Menteshe and Aydin (1300–1415). Venice.

| Painter | Migiel Fuca | Nicolò Gripioti | Giorgio Miçocostantin (Son of Priest Andrea) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of icons | 200 | 300 | 200 |

| Specifications | 100 in the Latin fashion (in forma a la Latina, all three types and based on Nicolò Gripioti’s models) 50 in deep blue gold brocade (first type) 50 in purple gold brocade (first type) | all in the Latin fashion (in forma a la latina, all three types, models for Migiel Fuca’s 100 icons in the Latin fashion) all painted on a gold background | 100 in the Latin fashion (in forma latina, all three types) 100 in the Greek fashion (in forma greca, all three types) 170 painted on a gold background 30 painted on a red background |

| Price7* * Based on (Vincent 2007), I have converted the prices to soldi, the coinage at the heart of the Venetian monetary system, in an attempt to provide a uniform value that allows for a better comprehension of the types (see below, 4. The Commission and its Value): 1 bezzo = half soldo; 1 yperpyron = 32 soldi; 1 marçelo = 10 soldi | Latin fashion: first type = 42 bezzi each (conversion = 21 soldi) second type = 1 yperpyron each (conversion = 32 soldi) third type = 1 marçelo each (conversion = 10 soldi) gold brocade (first type) = 48 bezzi each (conversion = 24 soldi) | Latin fashion: first type = 40 bezzi each (conversion = 20 soldi) second type = 1 yperpyron each (conversion = 32 soldi) third type = 1 marçelo each (conversion = 10 soldi) | Latin and Greek fashion: first type = 2 marçeli each (conversion = 20 soldi) second type = 34 bezzi each (conversion = 17 soldi) third type = 1 marçelo each (conversion = 10 soldi) |

| Advance payment | 5 ducats | 5 ducats and 600 golden leaves @ 12 yperpyri per 100 golden leaves | 117 yperpyri, 14 piçoli equal to 14 ducats and 6 bezzi |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lymberopoulou, A. Post-Byzantine Cretan Icon Painting: Demand and Supply Revisited. Arts 2023, 12, 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12040139

Lymberopoulou A. Post-Byzantine Cretan Icon Painting: Demand and Supply Revisited. Arts. 2023; 12(4):139. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12040139

Chicago/Turabian StyleLymberopoulou, Angeliki. 2023. "Post-Byzantine Cretan Icon Painting: Demand and Supply Revisited" Arts 12, no. 4: 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12040139

APA StyleLymberopoulou, A. (2023). Post-Byzantine Cretan Icon Painting: Demand and Supply Revisited. Arts, 12(4), 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12040139