1. Introduction

Driven by the escalating global energy crisis and environmental degradation, there is a widespread consensus on the urgent need to enhance energy efficiency and mitigate carbon emissions [

1]. Regional Integrated Energy Systems (RIESs) have emerged as a pivotal solution for low-carbon transition, enabling the cascade utilization and synergistic carbon sink complementation among different energy forms [

2,

3]. Hospitals, with their continuous 24/7 demands, substantial load volatility, and stringent reliability standards, are ideal candidates for RIES deployment [

4,

5].

In recent years, extensive research has been conducted on RIES optimization. Early work primarily focused on single economic objectives [

6,

7,

8,

9], which failed to meet increasingly stringent environmental regulations. Subsequent research shifted towards multi-objective optimization (MOO) to balance economic costs, energy consumption, and environmental emissions. MOO methods are generally categorized into no-preference, a priori, and a posteriori methods [

10]. No-preference methods (e.g., global criterion method) do not rely on decision-maker preferences but focus on neutral compromise solutions, thus having limited application in energy systems. A priori methods require preference articulation before solving, commonly using the weighted sum or ε-constraint methods. For example, Zeng et al. [

11] combined the weighted sum method with genetic algorithms for CCHP optimization. Liu et al. [

12] used the ε-constraint method to quantify the trade-off between economic and environmental goals, finding that a 57% reduction in carbon emissions increased costs by 15.1%, while also highlighting that shared energy storage can significantly reduce both investment and emissions. A posteriori methods aim to generate a Pareto solution set [

13]. For example, Qiao et al. [

14] achieved an 8.16% emission reduction and 2.25% efficiency improvement using the Fruit Fly Optimization Algorithm. Chen et al. [

15] proposed a gas turbine/PV/storage system, using multi-objective optimization to achieve a balance among energy efficiency (PESR up to 53.08%), power supply reliability (EMR reaching 99.88%), and environmental economy. While comprehensive, they leave the difficult task of selecting the final “best” solution to the decision-maker, often leading to confusion when the Pareto front is dense [

16,

17].

Despite these advancements, critical gaps remain in the existing literature regarding the handling of objective weights and environmental valuation. First, traditional weighted sum methods rely heavily on expert experience or the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), where minor subjective fluctuations in weights can lead to vastly different “optimal” configurations. Second, most studies optimize for a fixed set of weights, failing to account for preference robustness. In practice, decision preferences often shift due to external policy changes (e.g., carbon tax implementation) or internal budget constraints, and a configuration optimized for a single weight set may perform poorly if priorities change. Third, environmental objectives are often treated as physical quantities (e.g., tons of CO2), making them mathematically incommensurable with economic objectives, which leads to the use of arbitrary scaling factors.

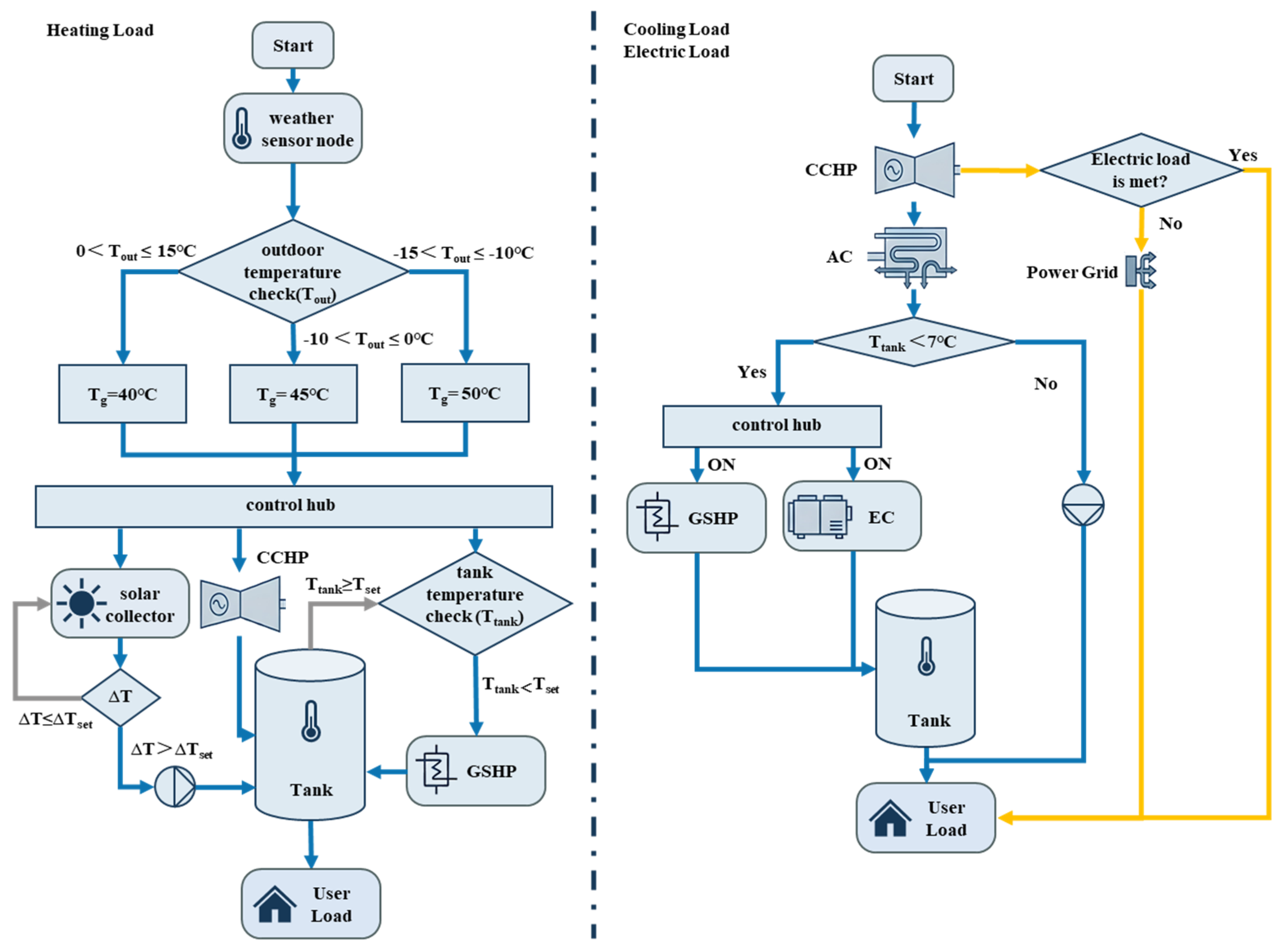

To address these limitations, this paper proposes an optimization method that quantifies environmental value based on “shadow costs” and ensures robustness through “multi-scenario weight scanning.” First, a dynamic simulation model of the hospital Renewable Integrated Energy System (RIES) was constructed using TRNSYS 17. Shadow cost theory is introduced to monetize the emissions of CO2, NOx, and SO2 into social marginal abatement costs. A weighted optimization model is established targeting the Annualized Cost Saving Rate (ACSR), Primary Energy Saving Rate (PESR), and Shadow Cost Saving Rate (SCSR). Second, to address the lack of preference robustness, a multi-scenario weight scanning strategy is implemented. Instead of identifying a single optimal point based on fixed weights, the system is optimized across ten distinct preference scenarios spanning the decision space to identify a configuration that remains optimal regardless of whether the priority is cost or environment. Finally, the Hooke–Jeeves algorithm is employed to identify the configuration that appears most frequently and is least sensitive to weight changes. This solution is proposed as the robust optimal configuration balancing economy, energy saving, and environmental protection, and is compared and analyzed with the reference system.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Sensitivity Analysis of Weights and Configurations

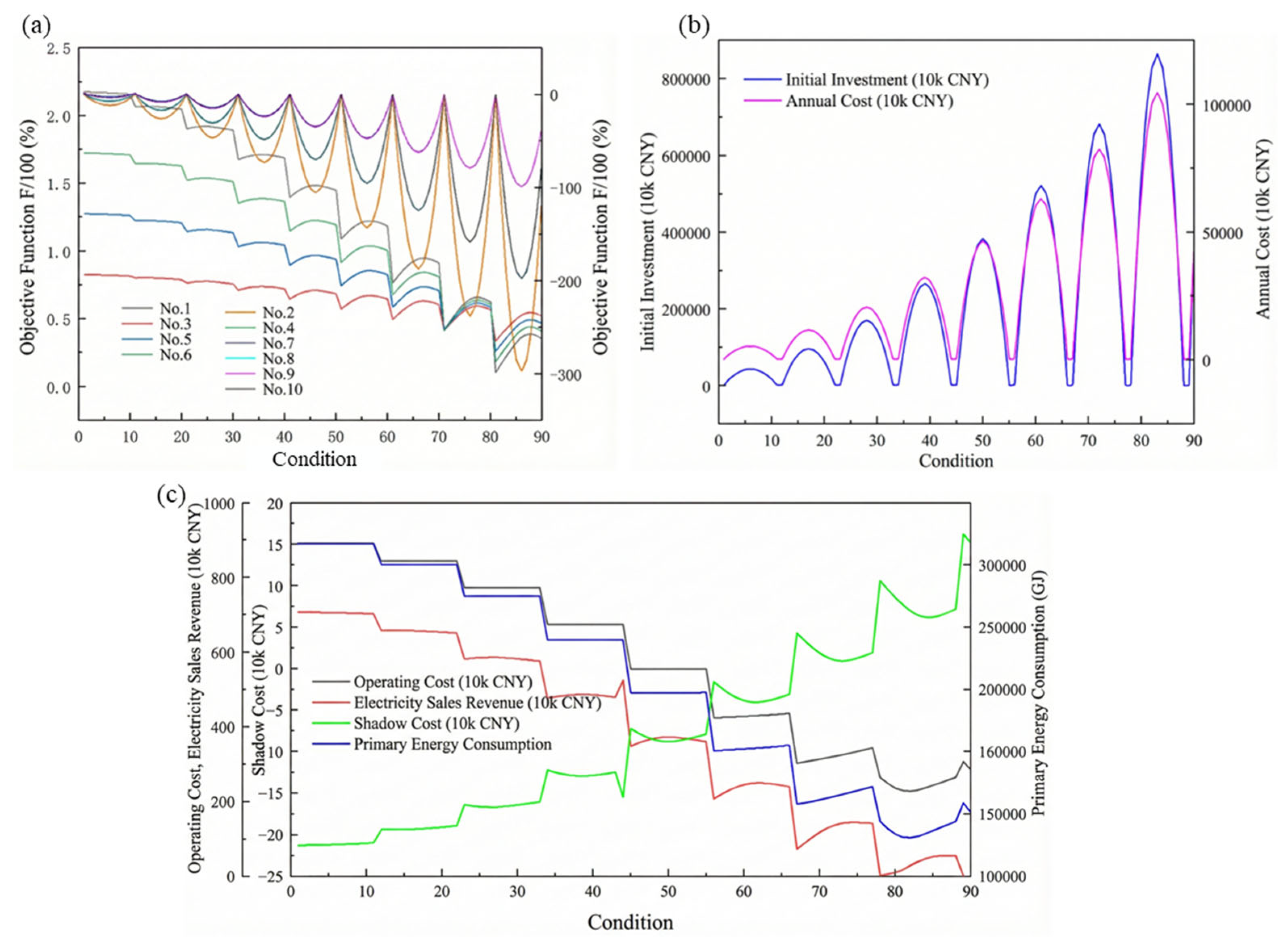

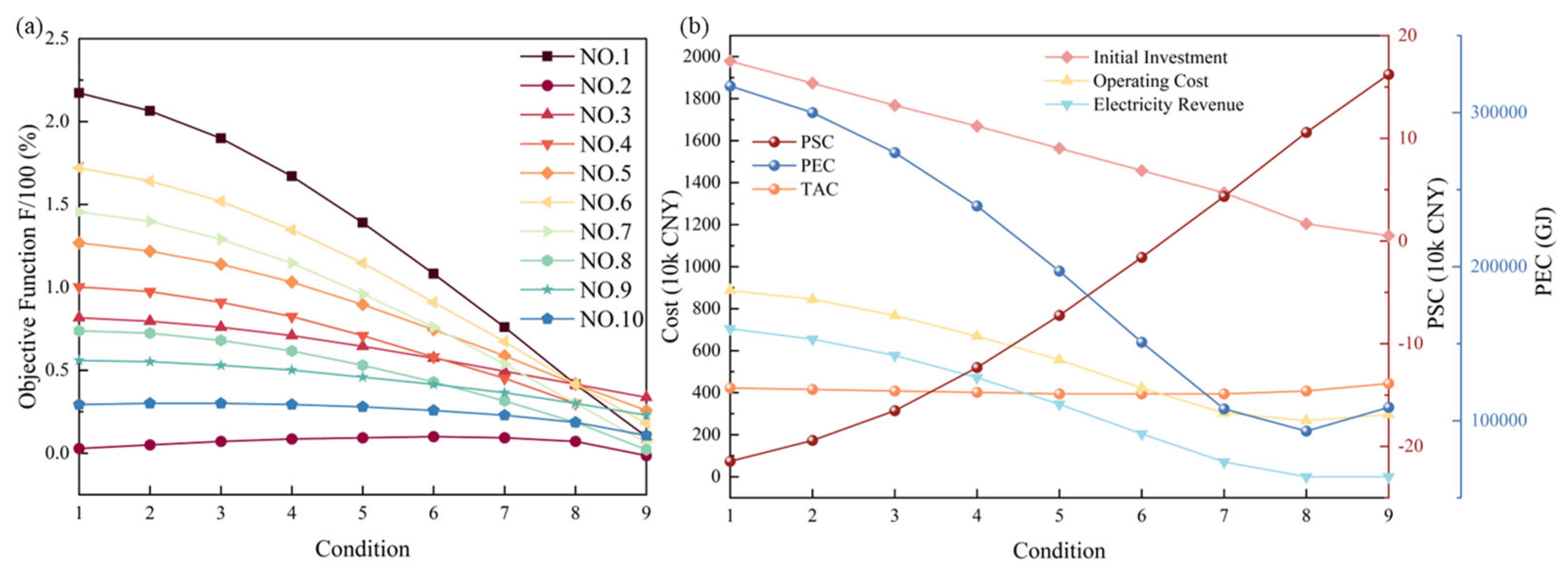

The trends of the comprehensive objective function values under different weight combinations, with respect to system configurations (centered on GT rated power), are illustrated in

Figure 5a. Generally, as the gas turbine (GT) power decreases (corresponding to operating conditions 1 to 90), the objective function

F shows a downward trend. It is worth noting that the rate of decline and the position of inflection points vary across different weight preferences. For instance, in economy-oriented scenarios (where weights favor cost saving), the objective function is highly sensitive to the reduction in GT power; conversely, in environment-oriented scenarios, the curve is relatively flat, indicating that the system maintains environmental benefits within a certain range through the compensation of other low-carbon equipment.

The intricate trade-off between economics and primary energy consumption is depicted in

Figure 5c. As GT power decreases, annual operating costs, electricity sales revenue, and primary energy consumption all exhibit a fluctuating downward trend; in contrast, the environmental shadow cost gradually increases. Unlike operating costs, the initial investment and annual cost of the system generally show a fluctuating upward trend (

Figure 5b). This is primarily because, to compensate for the power and heat deficit caused by GT downsizing, the system must rely on or enlarge other equipment (e.g., GSHPs, ECs), which often possess higher unit capital costs or operational electricity expenses. Notably, under most weight combinations, the local optimum for annualized cost occurs when the SC area is 0 m

2. This indicates that under the current boundary conditions (investment costs vs. energy prices), solar heating lacks a competitive advantage. This is attributed to the cooling–heating coupling constraint. The crowding-out effect of solar energy on winter heating reduces the requisite GSHP capacity. However, this downsizing constrains the GSHP’s cooling potential in summer, necessitating a compensatory expansion of the EC capacity. Consequently, the incremental costs for summer cooling negate the winter heating savings, eroding overall system viability.

Consequently, configurations with SC were discarded. The remaining nine distinct configurations are summarized in

Table 6.

Figure 6 presents the multi-scenario weight scanning results. As seen in

Figure 6a, a robust positive correlation is evident between the objective function

F and GT-rated power across all weight scenarios. The monotonic decline in

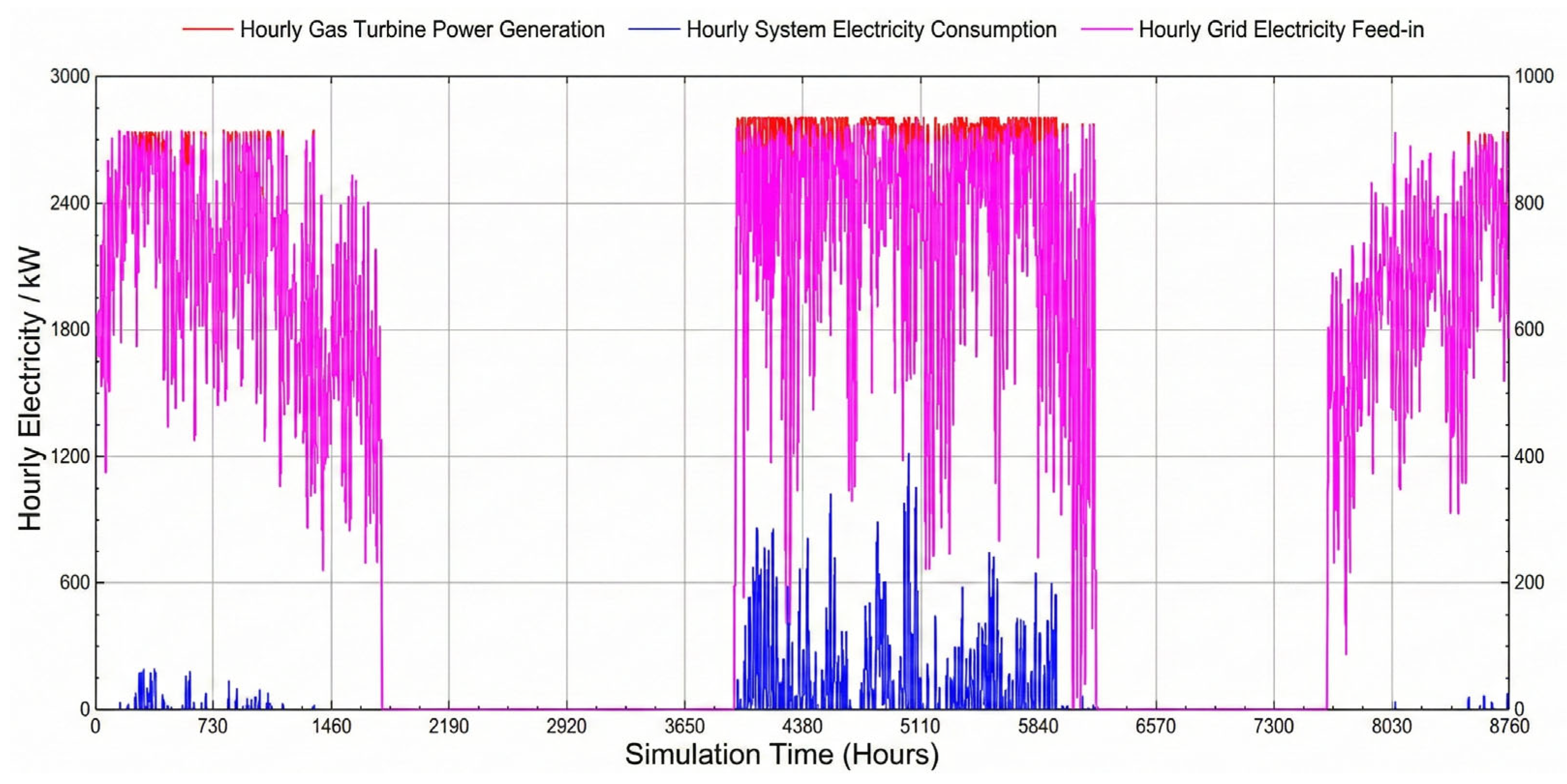

F with reduced GT power implies that, within the defined constraints, maximizing GT capacity optimizes the comprehensive utility of the RIES. This phenomenon is driven by the grid-interaction mechanism. Maximizing GT capacity amplifies grid-exported electricity (

Figure 6b). On one hand, high electricity sales revenue offsets operating costs; on the other hand, exporting clean electricity (substituting conventional coal power) generates significant environmental benefits (negative shadow costs). Although natural gas consumption increases, the electricity revenue and emission reduction benefits dominate the comprehensive evaluation.

Statistical analysis of the 10 weight scenarios reveals that Configuration 1 (GT 2790 kW, GSHP 1056 kW, EC 3479 kW) is identified as the optimal solution in over 80% of the scenarios. This confirms the preference robustness of this configuration, implying that regardless of whether the decision-maker prioritizes economy or environment, the “large-capacity GT + moderate-scale GSHP” scheme is the best choice for this hospital campus.

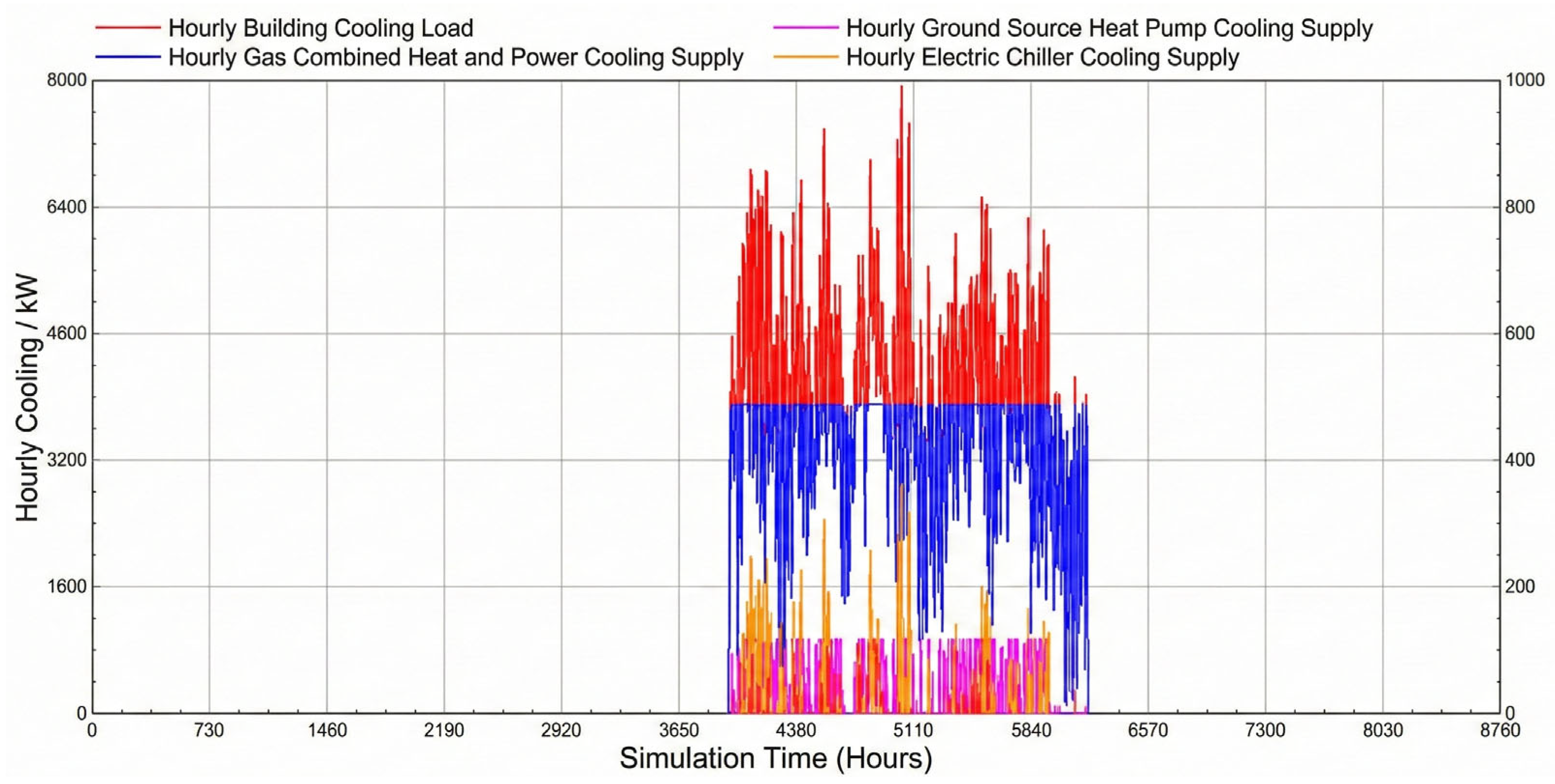

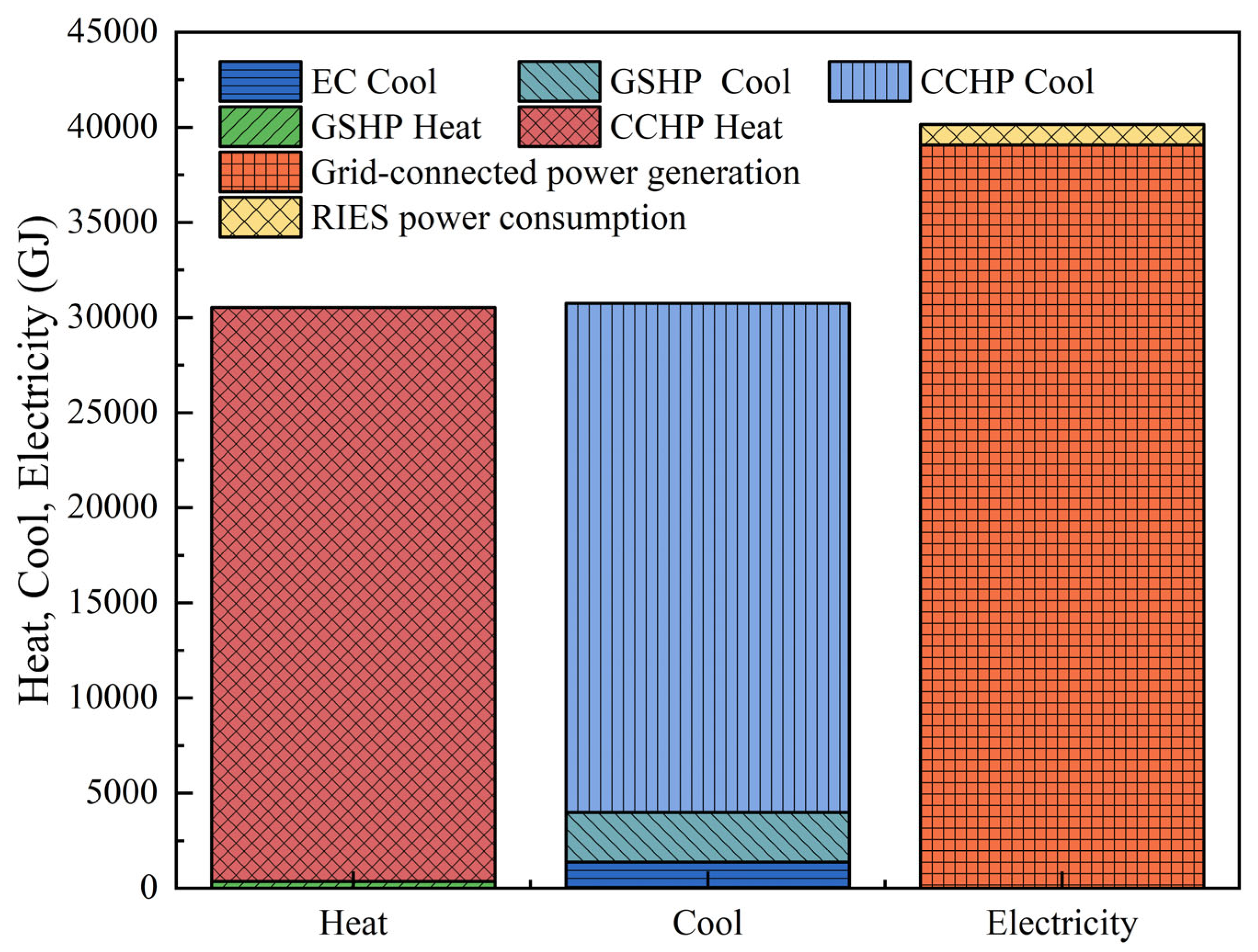

The load distribution under this optimal configuration is detailed in

Appendix A. As shown in

Figure 7, the CCHP system covers the vast majority of loads: 99% of the heating load and 86% of the cooling load. Of the remaining cooling load, the GSHP contributes 8.6%, with the rest supplemented by the EC. Notably, the high GT capacity enables the system to export 94% of its generation, functioning effectively as a distributed power plant.

4.2. Comprehensive Benefit Comparison

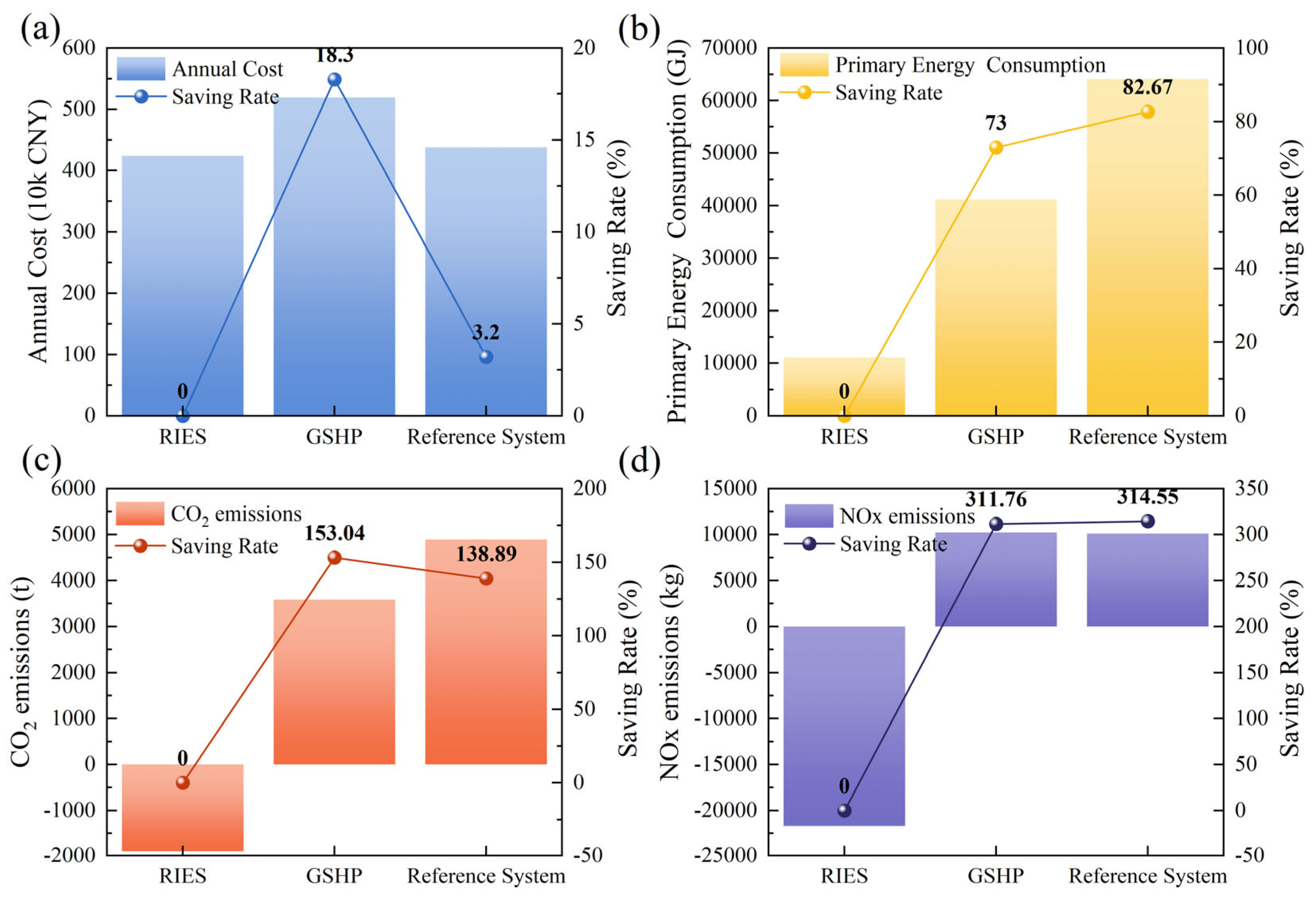

A comparative assessment of the robustly optimized RIES (Configuration 1) against the Standalone GSHP and reference systems was conducted to quantify annual performance. The results are summarized in

Table 7 and

Figure 8.

The comparison results demonstrate that the proposed RIES achieves a balance of “economic feasibility and environmental excellence.” Although the Annualized Total Cost (ATC) of the RIES is only slightly reduced by 3.2% compared to the reference system (constrained by higher initial capital costs), it still outperforms the Standalone GSHP System, verifying its economic viability. However, the environmental benefits are transformative. After accounting for the offset effect of exported electricity on the regional grid, the RIES effectively achieves net-negative emissions. Compared to the reference system and the Standalone GSHP System, the RIES achieves CO2 reduction rates of 153.04% and 138.89%, respectively. Furthermore, the NOx reduction rates reach remarkable levels of 311.76% and 314.55%. These significant reductions are primarily attributed to the cascade utilization of energy and the substitution of grid electricity (with higher marginal emissions) by efficient distributed generation. In addition, the energy-saving effect is substantial. The PESR is 82.67% and 73.00% relative to the reference system and Standalone GSHP System, respectively. This makes the system highly attractive for medical institutions committed to achieving ESG (environmental, social, and governance) goals.

4.3. Limitations and Sensitivity Analysis

While the “large-capacity GT + moderate-scale GSHP” configuration demonstrates superior performance, the interpretation of these results requires a critical examination of underlying assumptions and boundary conditions. First, the reported “net-negative emissions” are heavily predicated on the current carbon intensity of the regional grid, where exported electricity is assumed to displace high-carbon, coal-dominated power. Consequently, this environmental benefit represents a theoretical maximum. As the grid progressively decarbonizes with increased renewable penetration, the “offset” credit inevitably diminishes. Second, the economic robustness of the proposed configuration is sensitive to the spread (the margin between electricity feed-in tariffs and natural gas prices). The optimization currently favors maximizing exports under the assumption of unconstrained grid access; however, significant fluctuations in gas prices, reductions in distributed generation subsidies, or local grid export limits could shift the optimal capacity of the GT downwards. Finally, the exclusion of SC reflects current cost structures, the specific load characteristics of medical building campuses (high reliability and continuous thermal demand), and specific load-coupling dynamics. The economic viability of SCs remains subject to potential capital cost reductions or policy subsidies.