Shear Performance of Reinforced 3DPM-NM Specimens with Different Interface Locking Designs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Program

2.1. Materials and Specimen Design

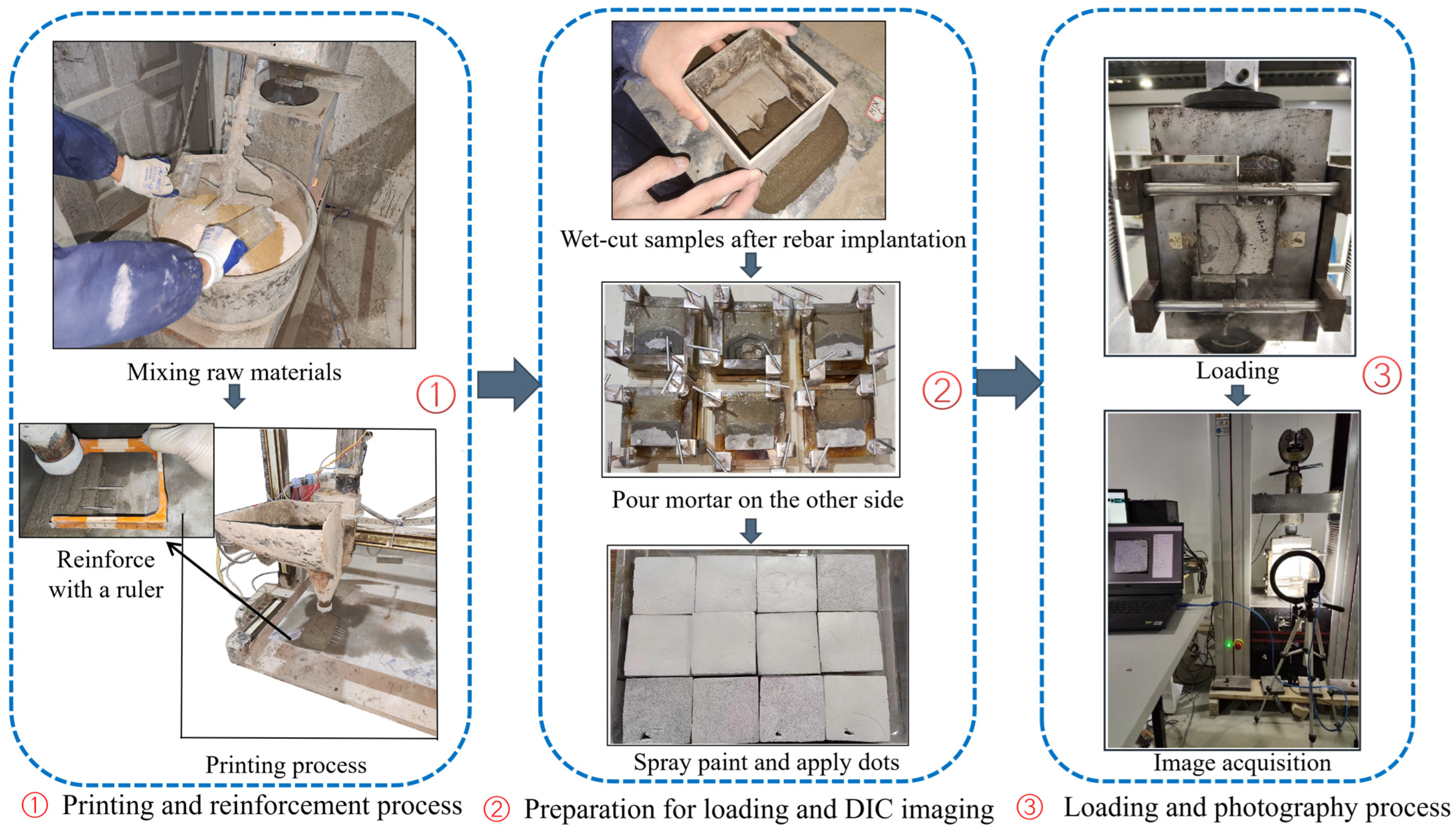

2.2. Printing Method and Reinforcement Process

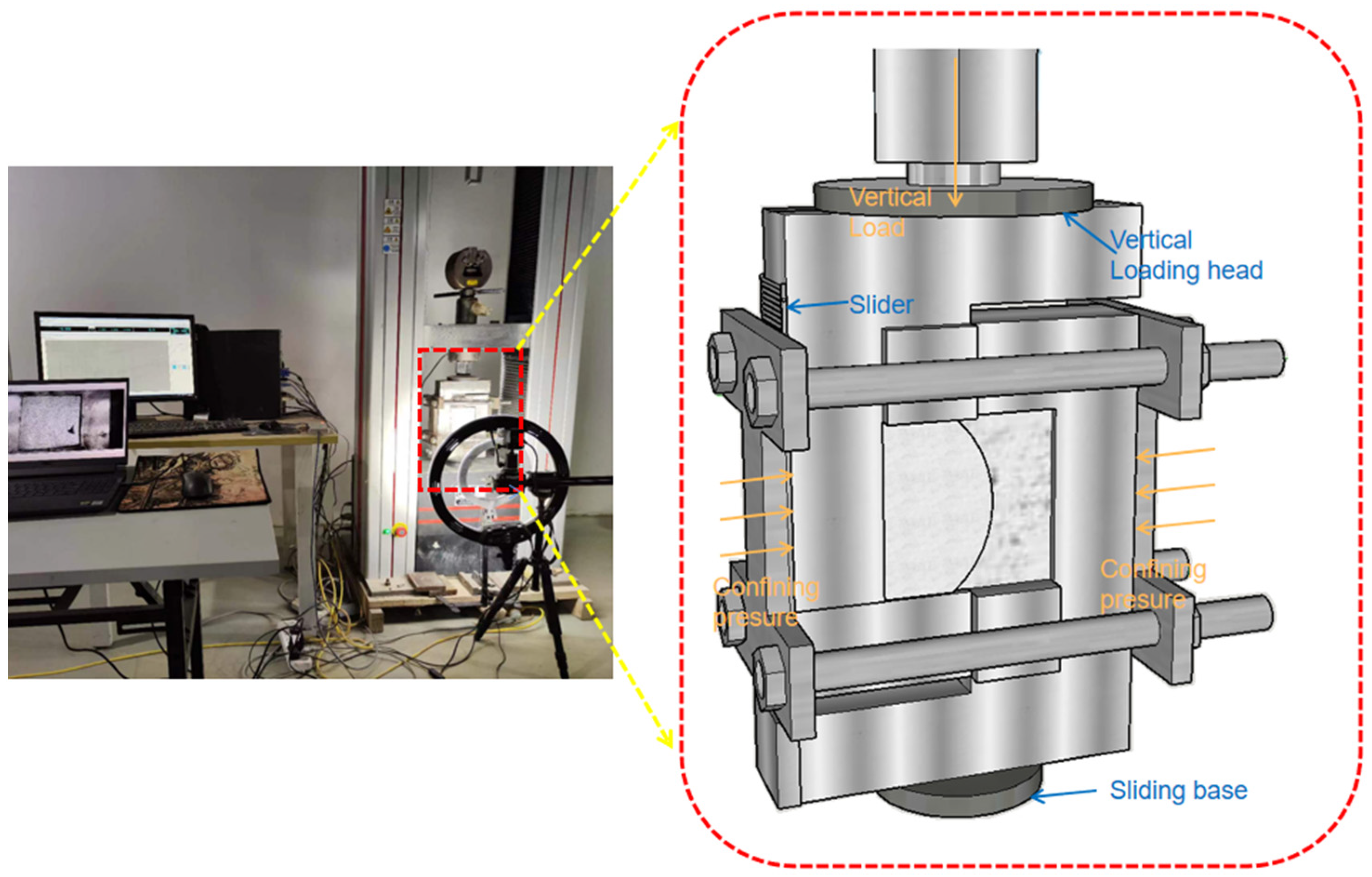

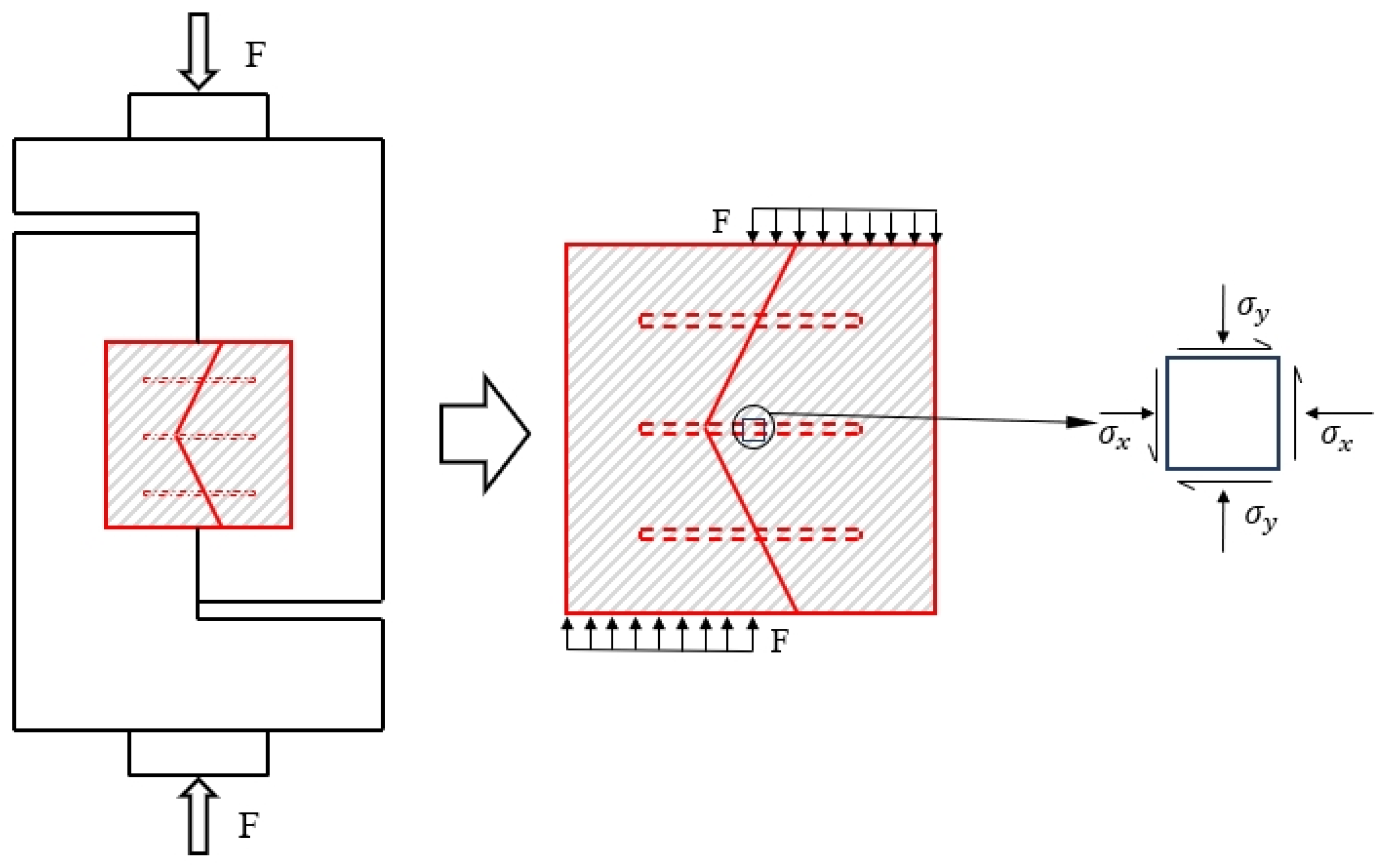

2.3. Test Procedure

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Test Results

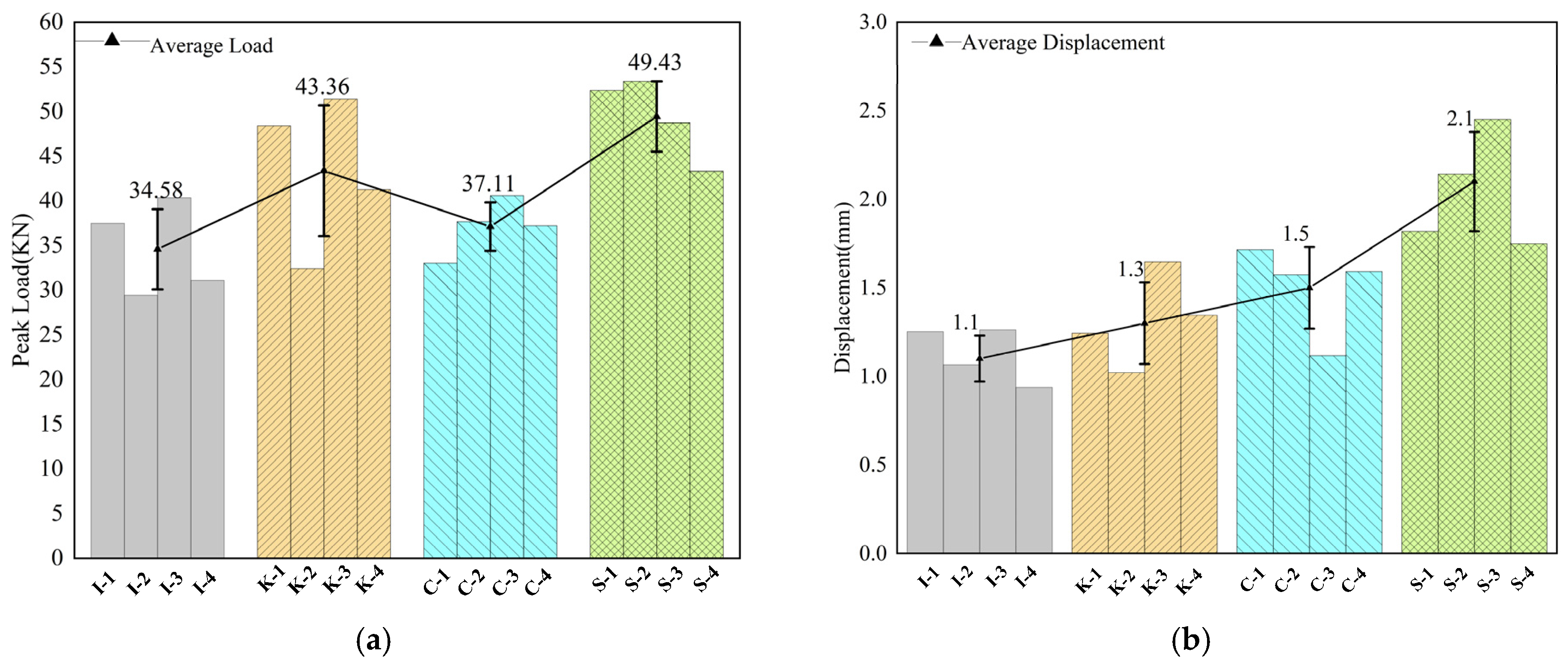

3.1.1. Peak Load and Corresponding Displacement at Peak Load

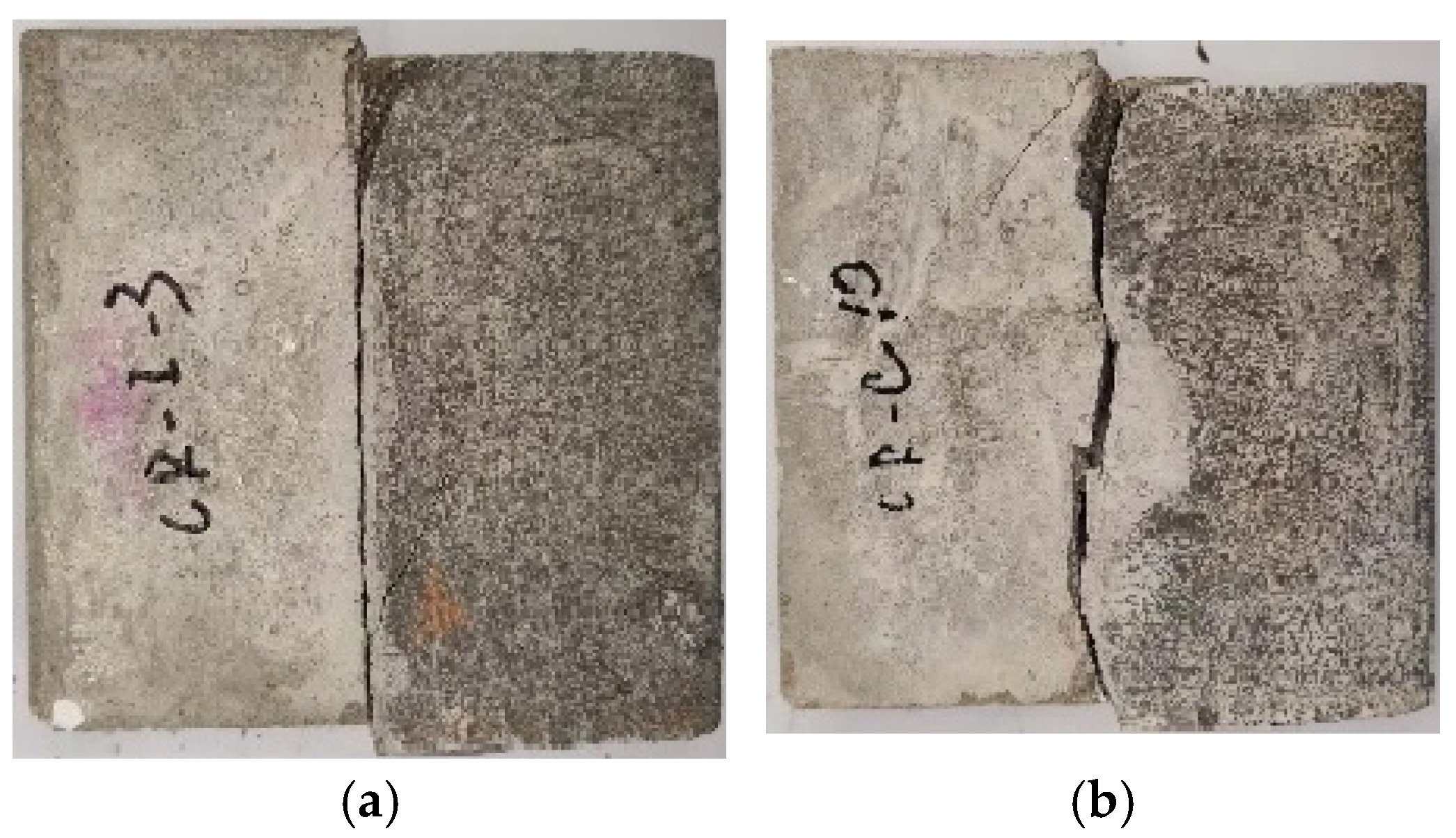

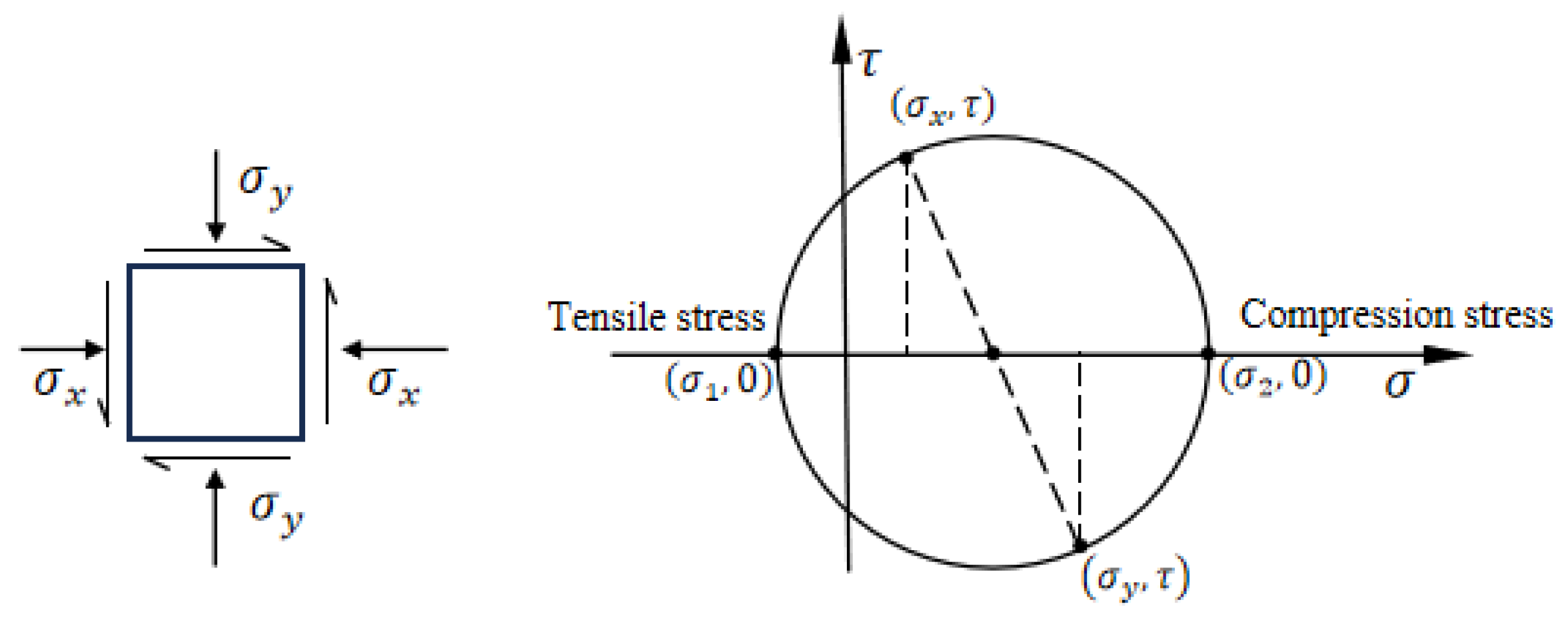

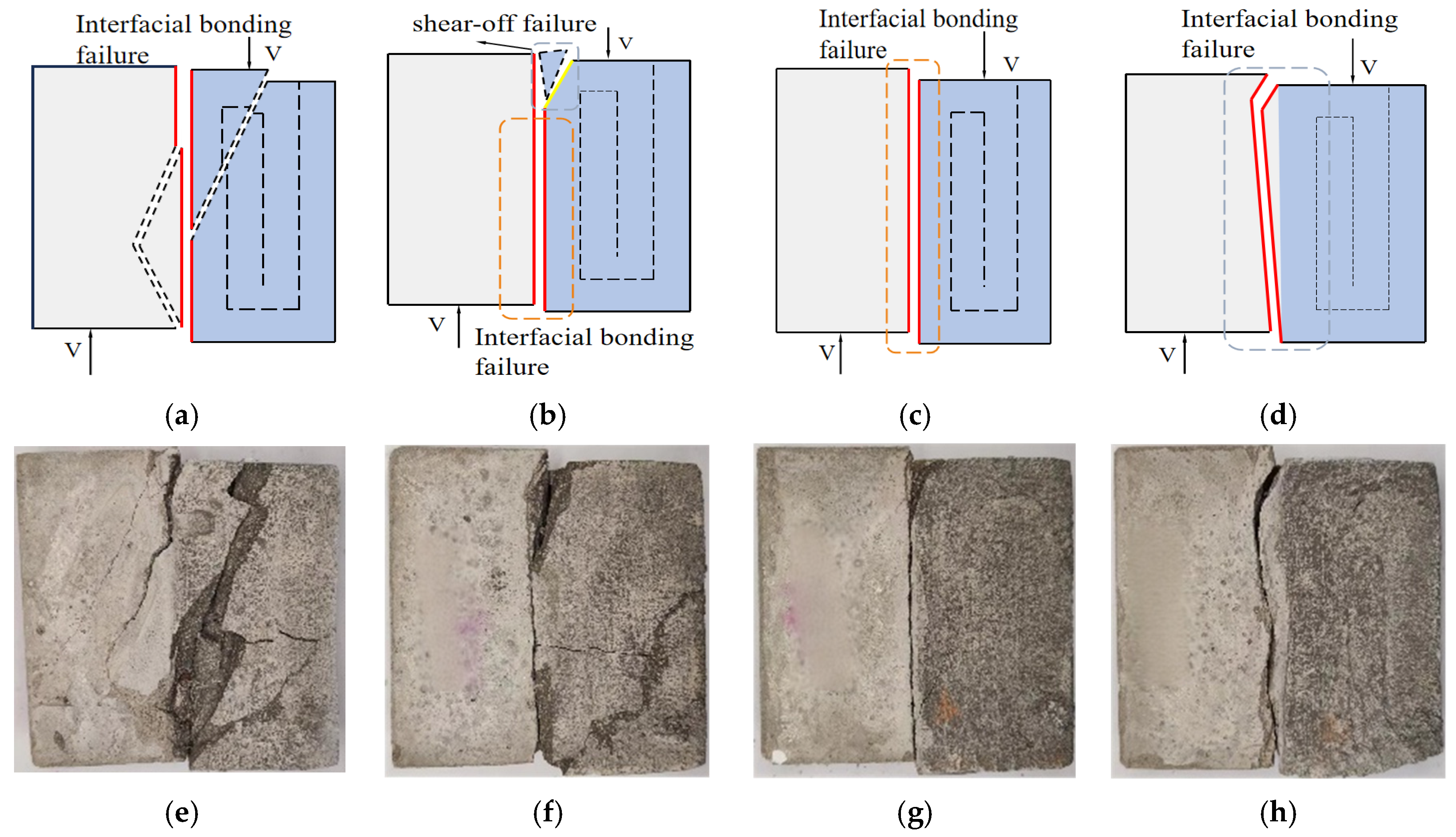

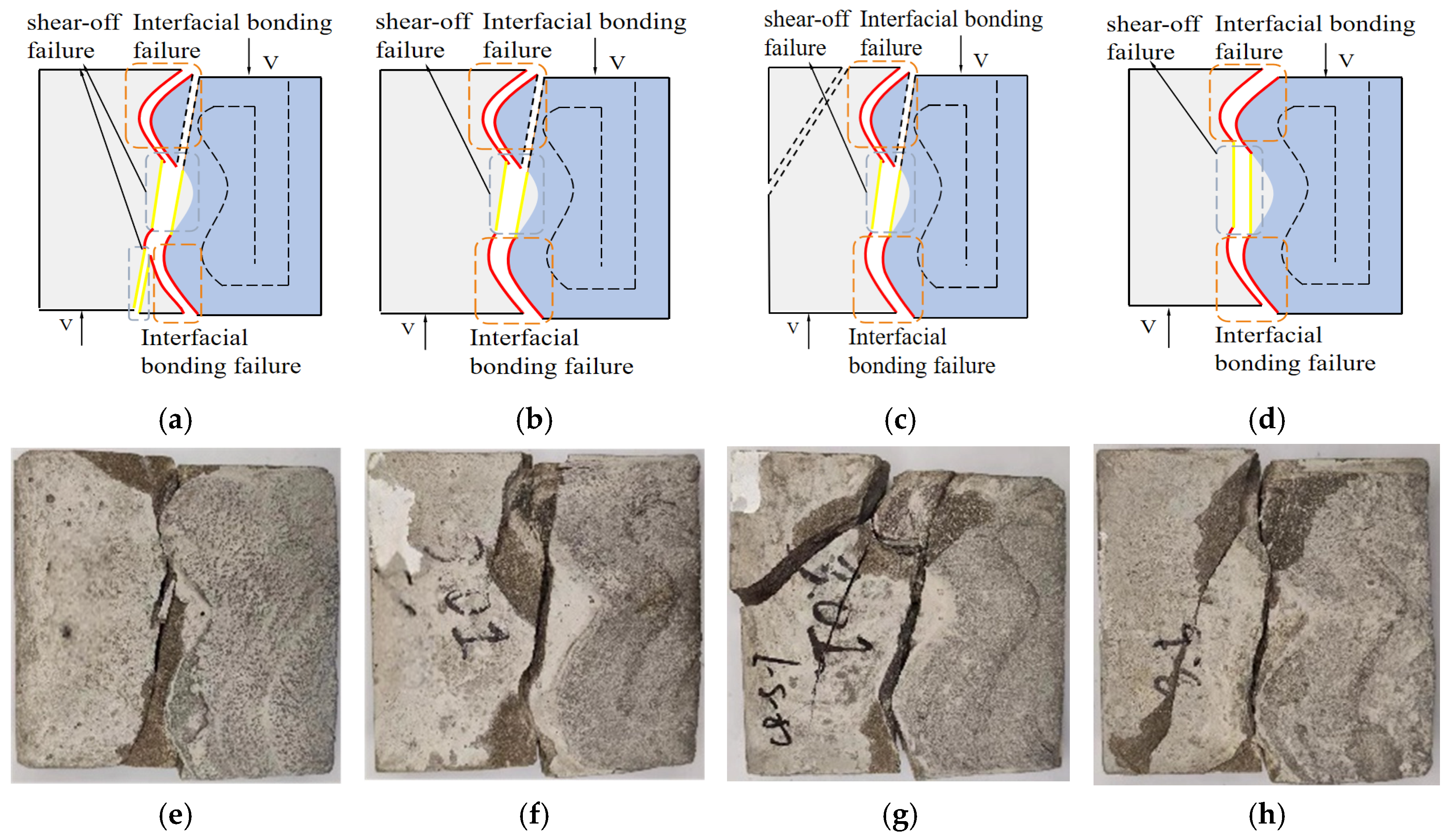

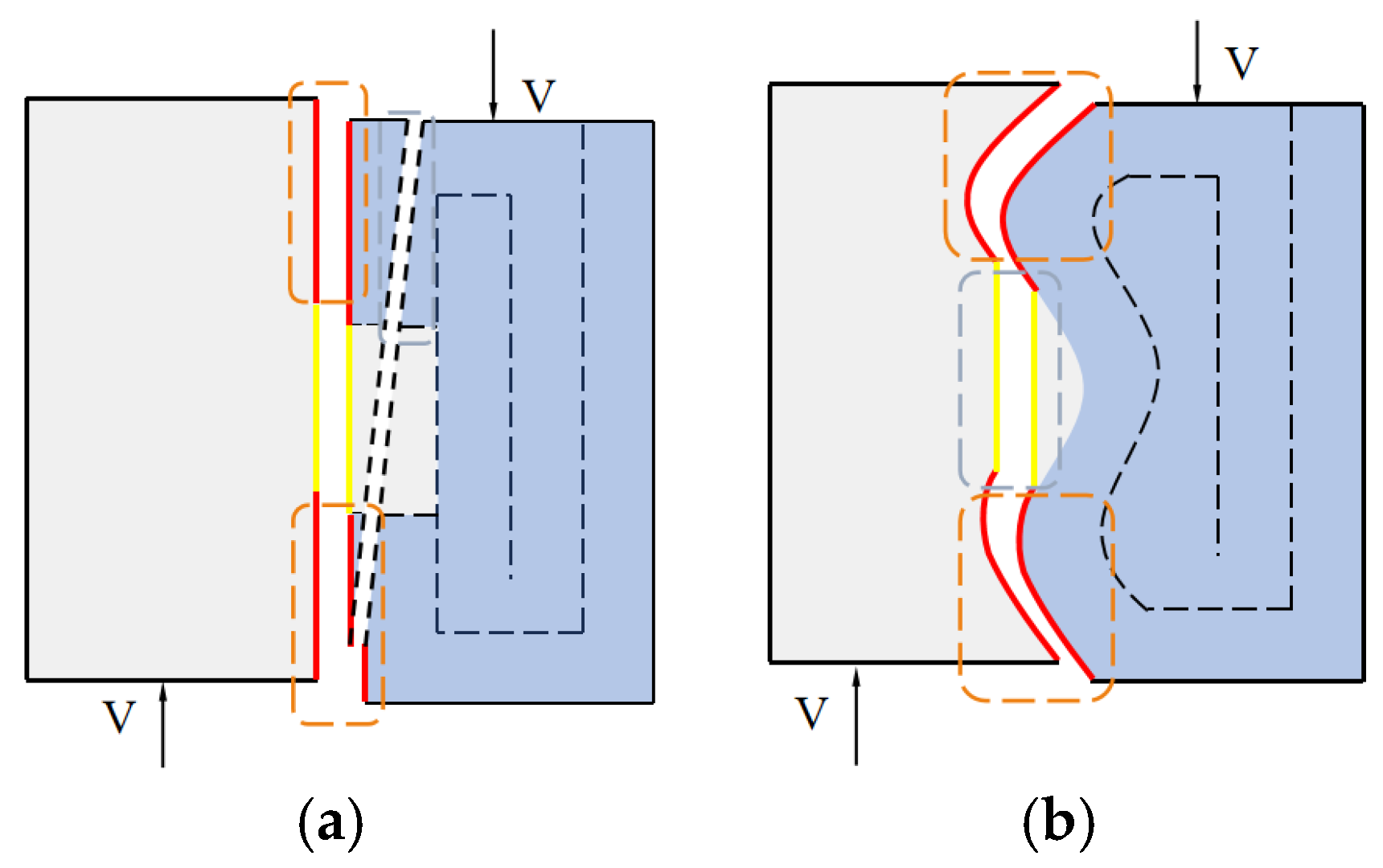

3.1.2. Failure Modes

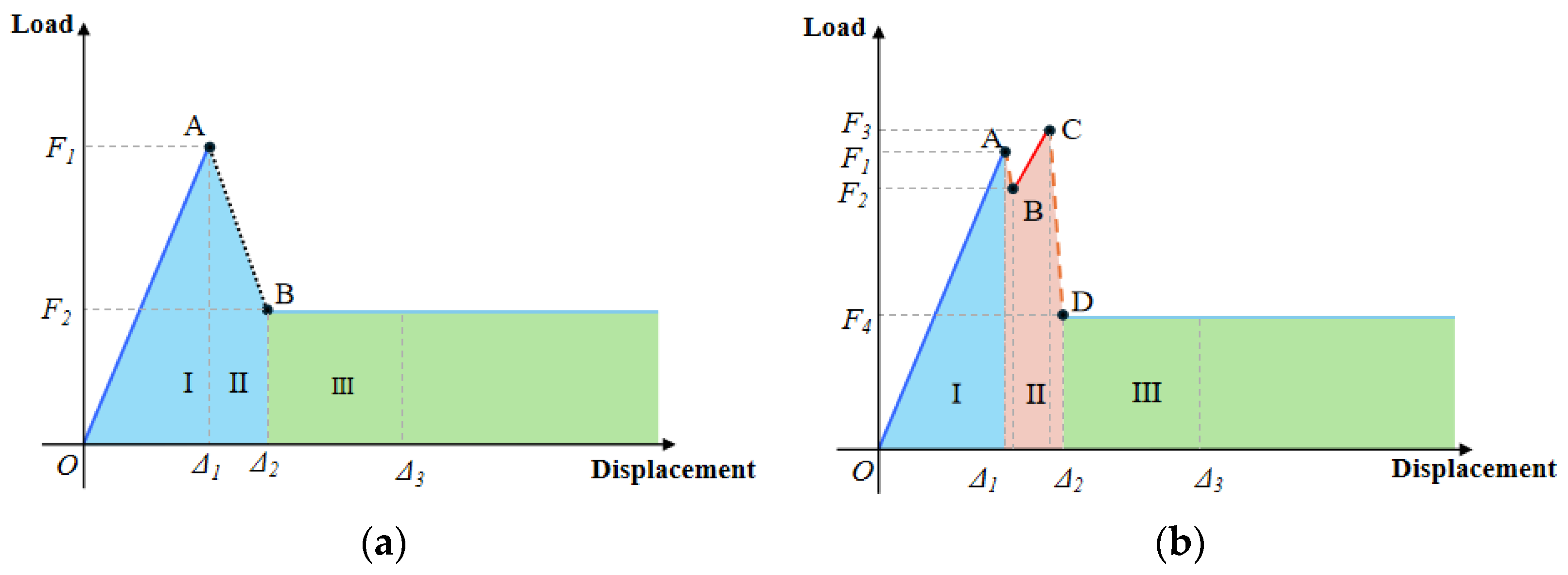

3.1.3. Simplified Formula and Shear Mechanism

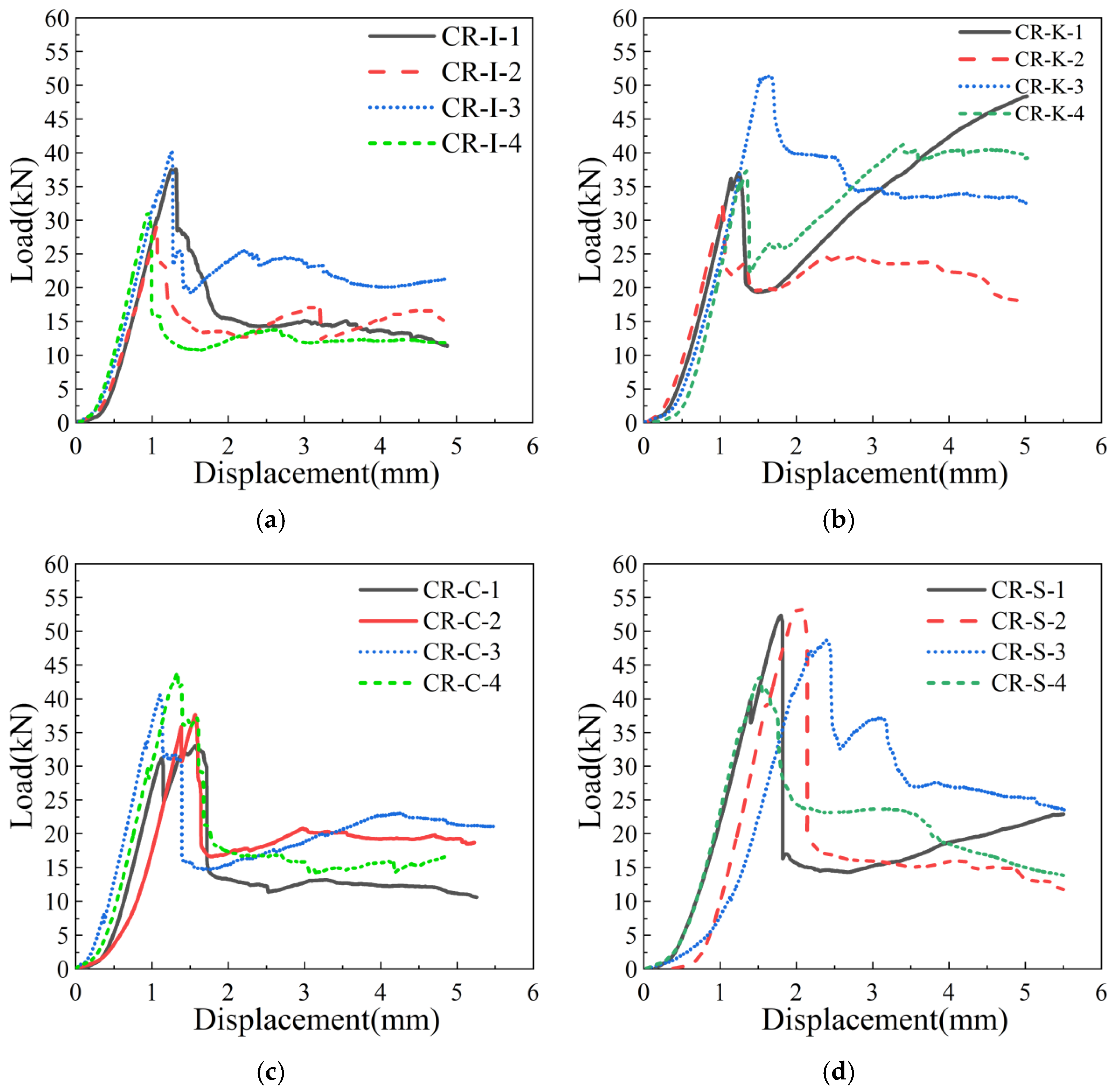

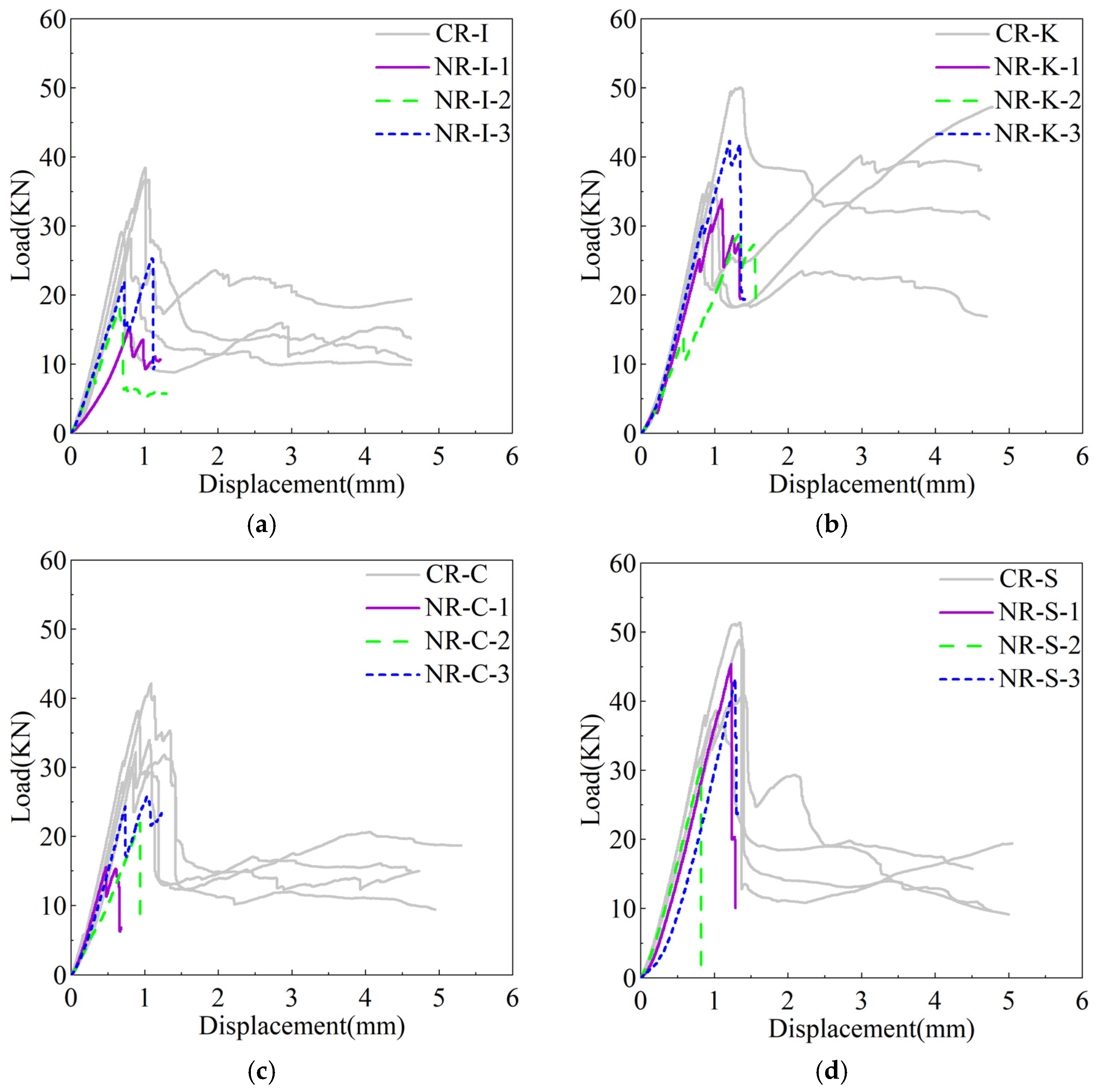

3.1.4. Load–Displacement Curve Analysis

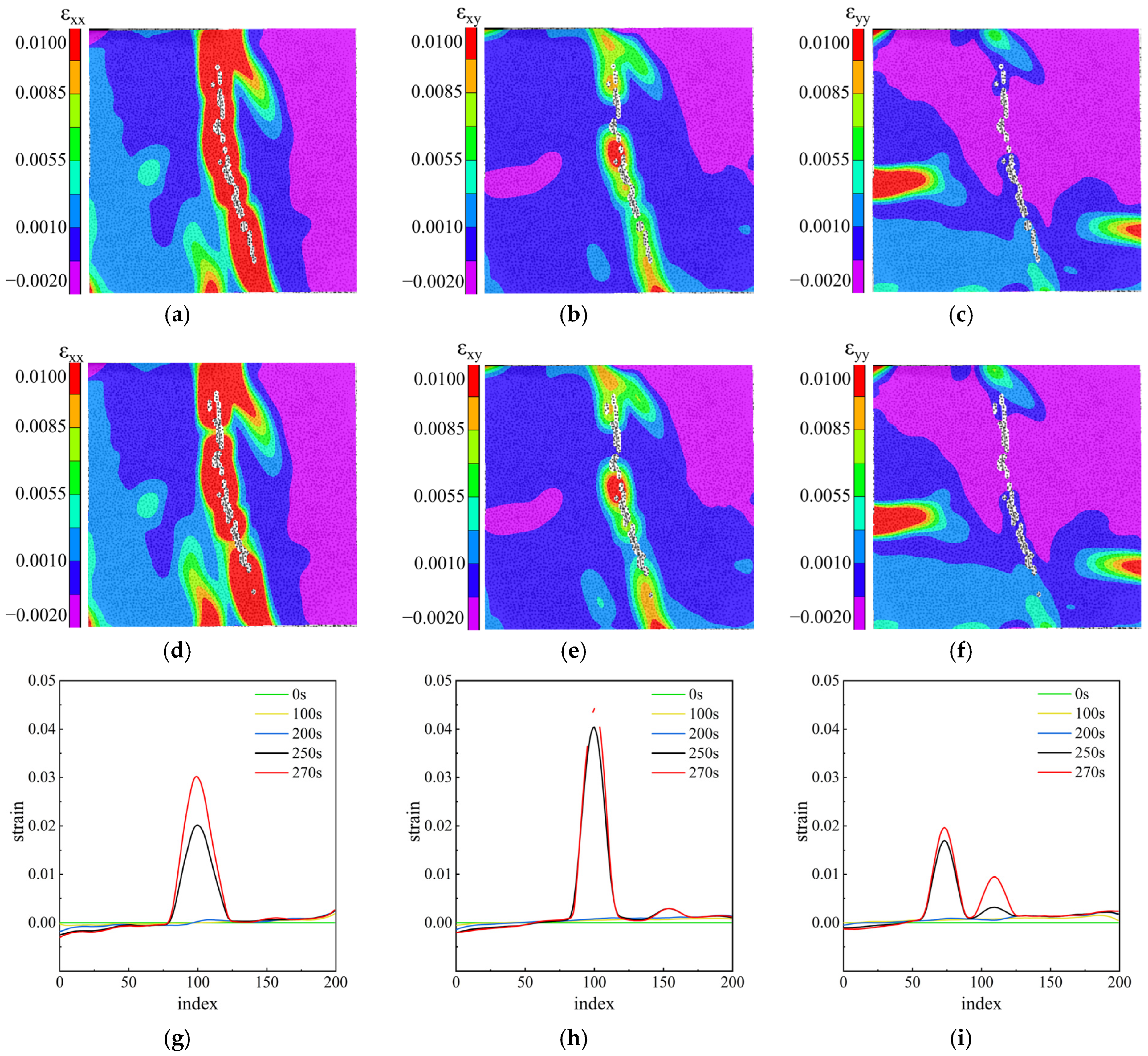

3.2. Shear Cracking Characteristics Based on DIC Analysis

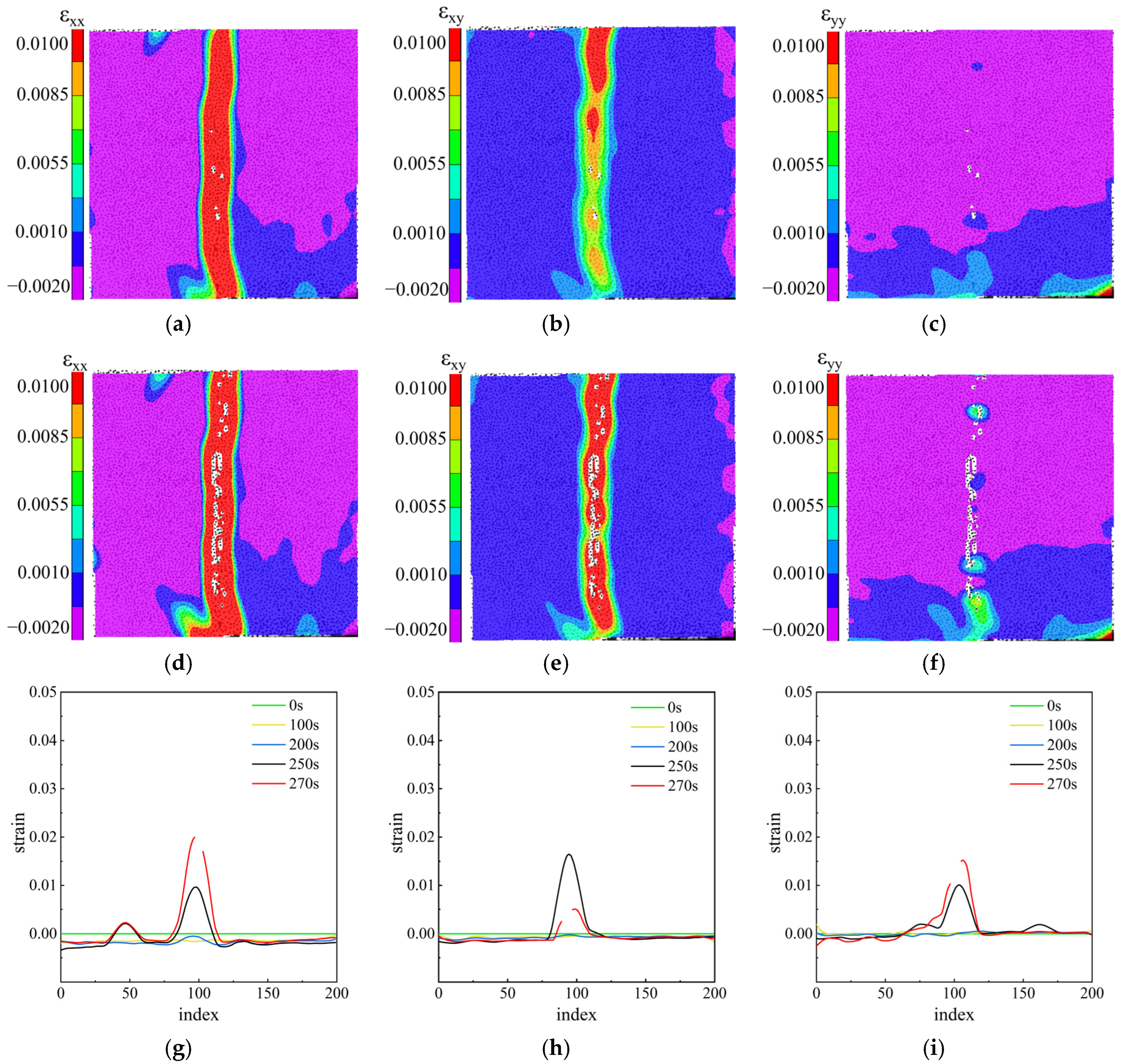

3.2.1. CR-I

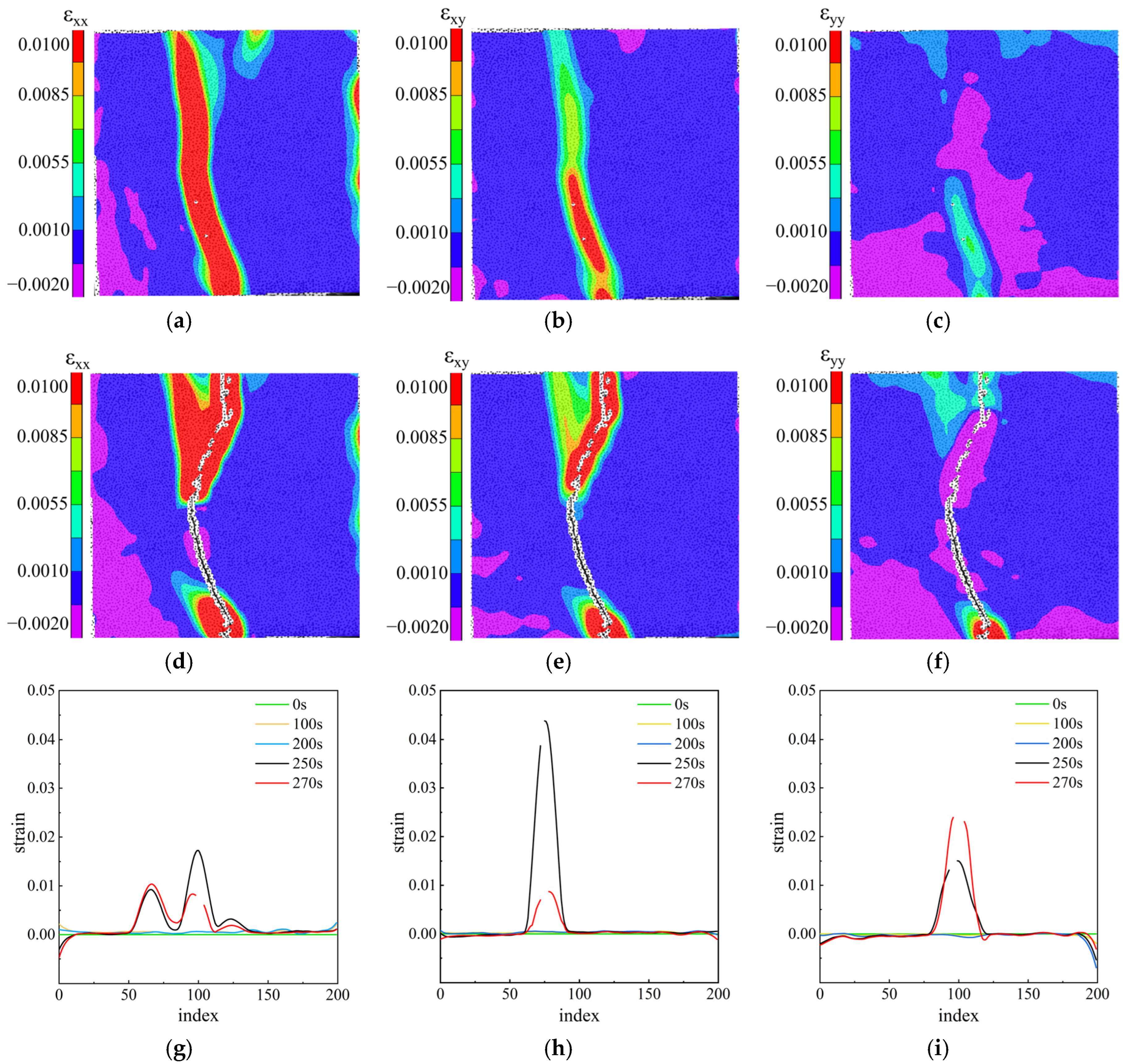

3.2.2. CR-K

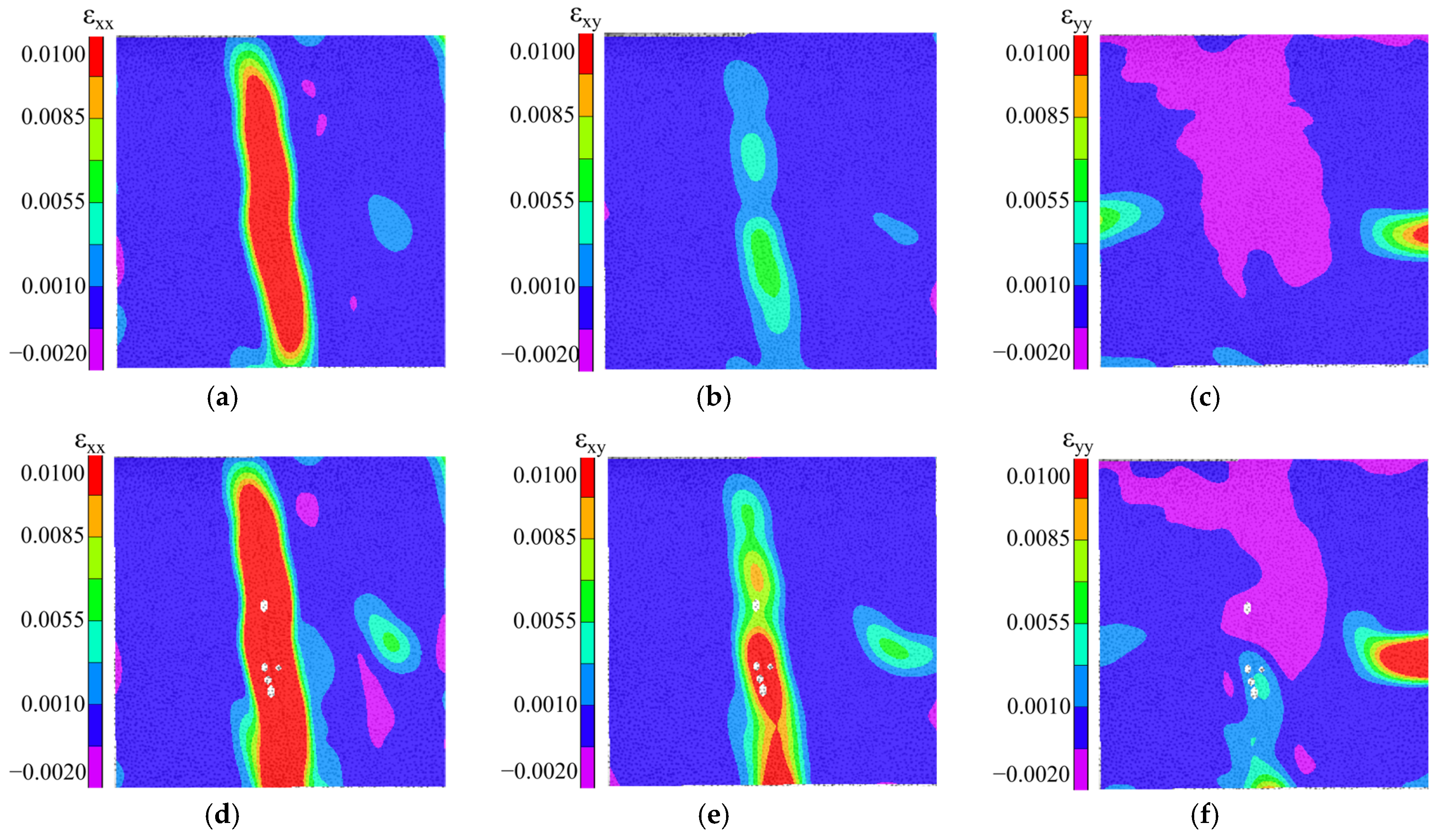

3.2.3. CR-C

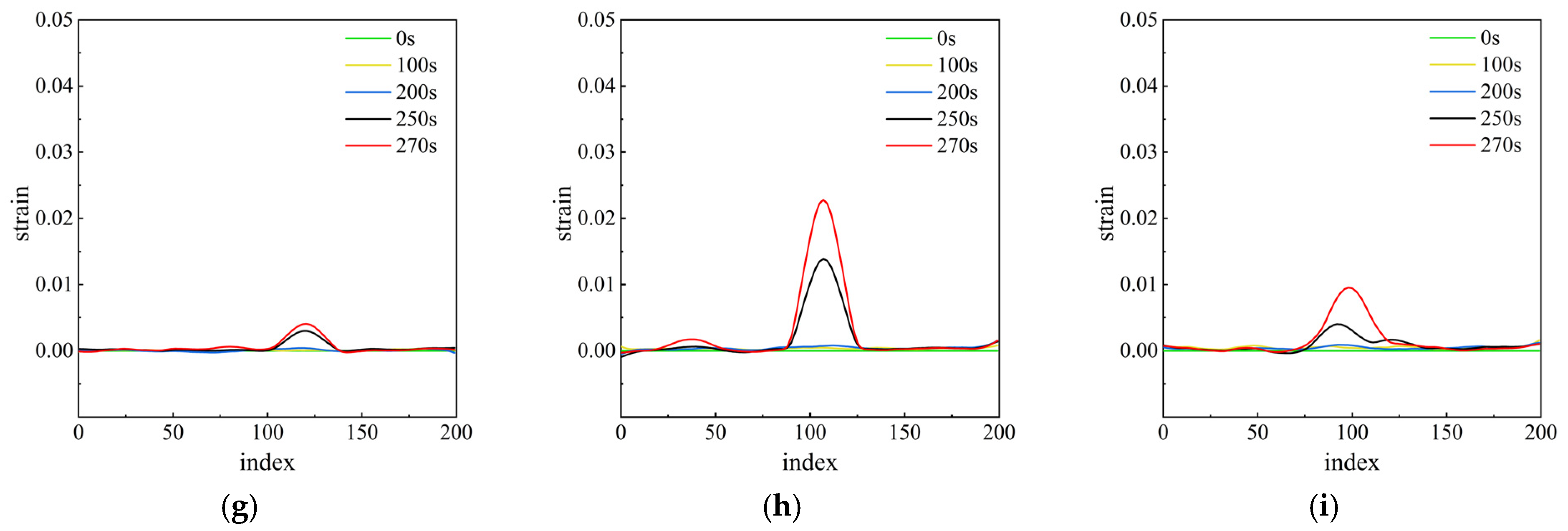

3.2.4. CR-S

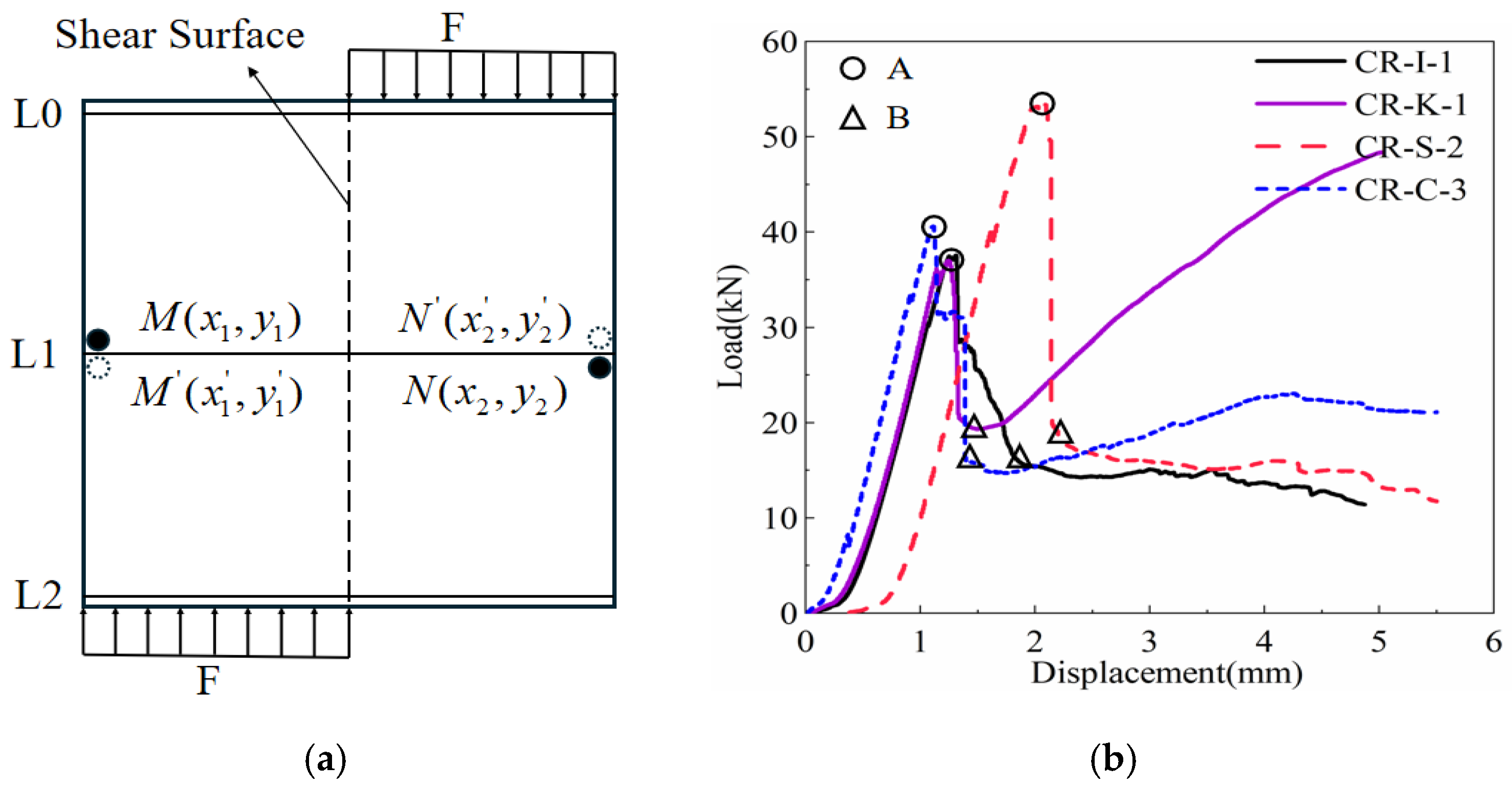

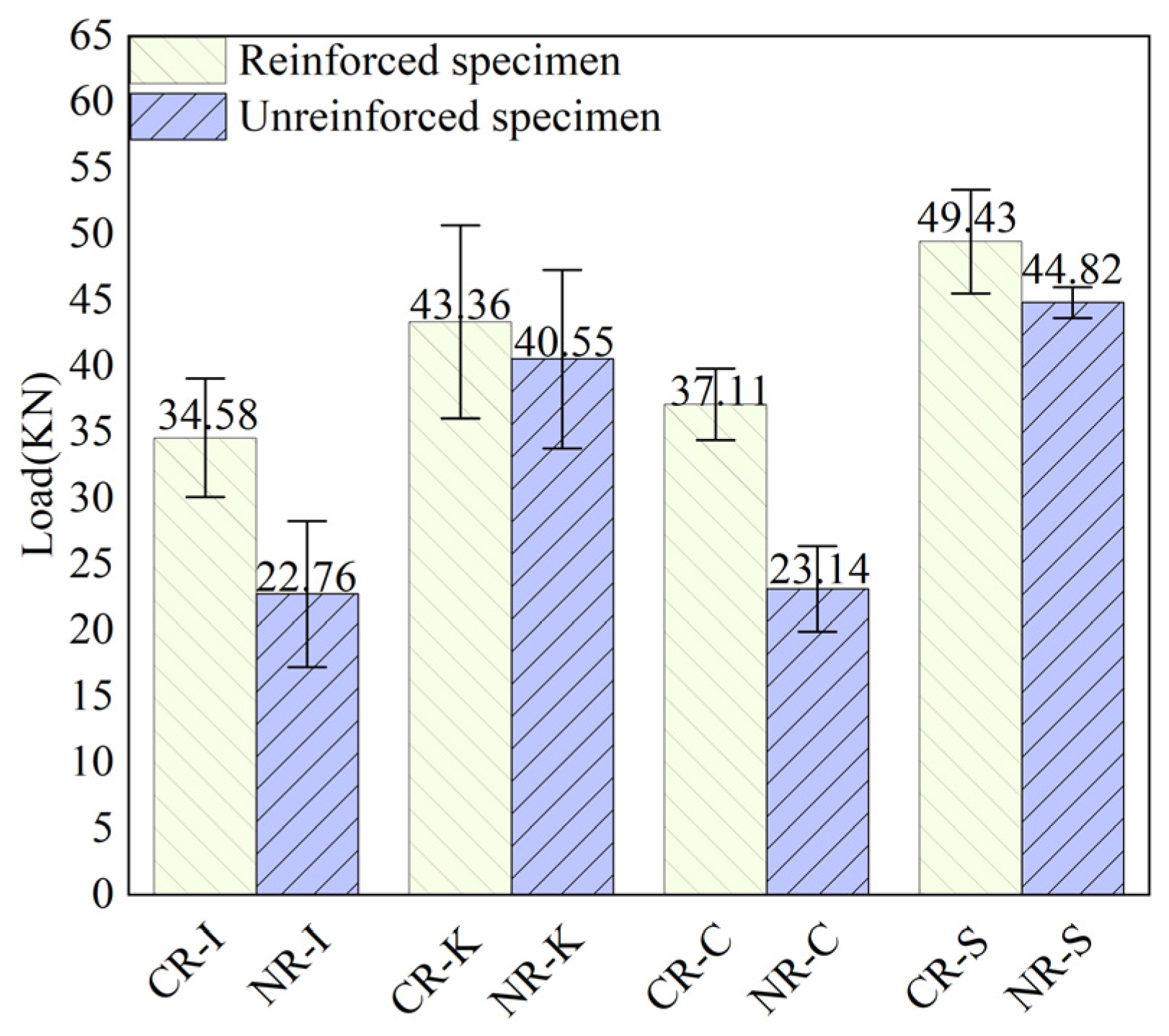

3.3. Comparative Analysis of Reinforced and Non-Reinforced Specimens

3.3.1. Peak Load

3.3.2. Energy Dissipation Capacity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lim, S.; Buswell, R.A.; Le, T.T.; Austin, S.A.; Gibb, A.G.F.; Thorpe, T. Developments in construction-scale additive manufacturing processes. Autom. Constr. 2012, 21, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharat, V.J.; Singh, P.; Raju, G.S.; Yadav, D.K.; Satyanarayana, M.; Arun, V.; Majeed, A.H.; Singh, N. Additive manufacturing (3D printing): A review of materials, methods, applications and challenges. Mater. Today Proc. 2023; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Schutter, G.; Lesage, K.; Mechtcherine, V.; Nerella, V.N.; Habert, G.; Agusti-Juan, I. Vision of 3D printing with concrete—Technical, economic and environmental potentials. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 112, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takva, Ç.; Top, S.M.; Gökgöz, B.İ.; Gebel, Ş.; İlerisoy, Z.Y.; İlcan, H.; Şahmaran, M. Applicability of 3D concrete printing technology in building construction with different architectural design decisions in housing. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 111257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, A.; Reiter, L.; Wangler, T.; Frangez, V.; Flatt, R.J.; Dillenburger, B. A 3D concrete printing prefabrication platform for bespoke columns. Autom. Constr. 2021, 122, 103467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murad, Y.; Abu-AlHaj, T. Novel 3D printed bars for retrofitting heat damaged RC beams. Structures 2021, 34, 3427–3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, G.H. A review of “3D concrete printing”: Materials and process characterization, economic considerations and environmental sustainability. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 66, 105863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Li, Z.; Wang, L. Printable properties of cementitious material containing copper tailings for extrusion based 3D printing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 162, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjayan, J.G.; Nematollahi, B.; Xia, M.; Marchment, T. Effect of surface moisture on inter-layer strength of 3D printed concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 172, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, F.; Sanjayan, J. Mechanical anisotropy of aligned fiber reinforced composite for extrusion-based 3D printing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 202, 770–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, O.; Mishra, A.; Isam, F. An overview of 3D printed concrete for building structures: Material properties, sustainability, future opportunities, and challenges. Structures 2025, 78, 109284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Sanchez, F.; Zhou, H. 3-D printing of concrete: Beyond horizons. Cem. Concr. Res. 2020, 133, 106070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Z.; She, W.; Zuo, W.; Lyu, K.; Pan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Miao, C. Layer-interface properties in 3D printed concrete: Dual hierarchical structure and micromechanical characterization. Cem. Concr. Res. 2020, 138, 106220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Carlo, T.; Khoshnevis, B.; Carlson, A. Experimental and Numerical Techniques to Characterize Structural Properties of Fresh Concrete, ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition. In Proceedings of the ASME 2014 International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition (IMECE2014); American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Liu, Q.; Xiao, J.; Lyu, Q. Mechanical and macrostructural properties of 3D printed concrete dosed with steel fibers under different loading direction. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 323, 126616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moelich, G.M.; Kruger, J.; Combrinck, R. Modelling the interlayer bond strength of 3D printed concrete with surface moisture. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 150, 106559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thamboo, J.A.; Dhanasekar, M.; Yan, C. Flexural and shear bond characteristics of thin layer polymer cement mortared concrete masonry. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 46, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jin, K.; Tao, J. Improving the interfacial shear strength of carbon fibre and epoxy via mechanical interlocking effect. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2020, 200, 108423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javan, A.R.; Seifi, H.; Lin, X.; Xie, Y.M. Mechanical behaviour of composite structures made of topologically interlocking concrete bricks with soft interfaces. Mater. Des. 2020, 186, 108347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, A.; Xu, Y.; Kartal, M.E.; Gadegaard, N.; Mulvihill, D.M. Enhancing strength and toughness of adhesive joints via micro-structured mechanical interlocking. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2021, 105, 102775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, J.; Xu, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, J.; Wang, X. Utilization of antimony tailings in fiber-reinforced 3D printed concrete: A sustainable approach for construction materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 408, 133689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahul, A.V.; Santhanam, M.; Meena, H.; Ghani, Z. Mechanical characterization of 3D printable concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 227, 116710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhao, X. Interlayer Bond Strength of 3D Printing Cement Paste by Cross-Bonded Method. Kuei Suan Jen Hsueh Pao/J. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2019, 47, 648–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Ye, B.; Lin, K.; Wang, H. Shear performance of 3D printed concrete reinforced with flexible or rigid materials based on direct shear test. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 48, 103860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shao, J.; Zhang, J.; Zou, D.; Sun, X. Bond shear performances and constitutive model of interfaces between vertical and horizontal filaments of 3D printed concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 316, 125819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Bai, M. Bonding performance of 3D printing concrete with self-locking interfaces exposed to compression–shear and compression–splitting stresses. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 42, 101992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Yu, P.; Law, S.S. Load resisting mechanism of the mortise-tenon connection with gaps under in-plane forces and moments. Eng. Struct. 2020, 219, 110755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Wu, Y.; Yu, S.; He, C.; Liang, Z. Interlayer reinforced 3D printed concrete with recycled coarse aggregate: Shear properties and enhancement methods. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 94, 104507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, Q.; Li, F. Interfacial bond effects on the shear strength and damage in 3D-printed concrete structures: A combined experimental and numerical study. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2025, 315, 110840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Zhao, H.; Liu, Q.; Pan, F. Shear behavior of 3DPM-NM specimens with different interfacial locking designs. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 425, 136021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50367-2013; Code for Design of Reinforcement of Concrete Structures. The National Standards of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2013.

- GB/T 11253-2019; Cold-Rolled Carbon Structural Steel Plates and Strips. The National Standards of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Tian, J.; Wu, X.; Zheng, Y.; Hu, S.; Du, Y.; Wang, W.; Sun, C.; Zhang, L. Investigation of interface shear properties and mechanical model between ECC and concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 223, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hao, H.; Zheng, J.; Hernandez, F. The mechanical performance of concrete shear key for prefabricated structures. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2021, 24, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AASHTO GSCB-2-M; Guide Specifications for Design and Construction of Segmental Concrete Bridges, 2nd Edition, and 2003 Interim. American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials: Washington, DC, USA, 1999.

| Cement | Sand | SF | Water | Def | HPMC | SP | NC | SG | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3DPM | 1000 | 1000 | 230 | 260 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| Series | (mm2) | (mm2) | (mm2) | (kN) | (kN) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR-I-1 | 4000 | 0 | 0 | 32.56 | 37.55 | 0.87 | 0.95 |

| CR-I-2 | 3200 | 0 | 800 | 33.69 | 29.43 | 1.14 | |

| CR-I-3 | 4000 | 0 | 0 | 32.56 | 40.35 | 0.81 | |

| CR-I-4 | 4000 | 0 | 0 | 32.56 | 31.09 | 1.05 | |

| CR-K-1 | 0 | 800 | 3417 | 38.56 | 37.02 | 1.04 | 1.00 |

| CR-K-2 | 0 | 800 | 3417 | 38.56 | 32.43 | 1.19 | |

| CR-K-3 | 0 | 800 | 3417 | 38.56 | 51.39 | 0.75 | |

| CR-K-4 | 2480 | 400 | 1709 | 39.21 | 37.02 | 1.06 | |

| CR-C-1 | 2668 | 1333 | 0 | 31.78 | 33.01 | 0.96 | 0.94 |

| CR-C-2 | 2668 | 1333 | 0 | 31.78 | 37.65 | 0.84 | |

| CR-C-3 | 2668 | 1333 | 0 | 31.78 | 30.40 | 1.05 | |

| CR-C-4 | 2668 | 1333 | 0 | 31.78 | 37.10 | 0.86 | |

| CR-S-1 | 6000 | 0 | 0 | 47.73 | 52.34 | 0.91 | 0.98 |

| CR-S-2 | 6000 | 0 | 0 | 47.73 | 53.37 | 0.89 | |

| CR-S-3 | 6000 | 0 | 0 | 47.73 | 48.70 | 0.98 | |

| CR-S-4 | 4000 | 2000 | 0 | 46.56 | 41.29 | 1.13 |

| Series | εxx | εxy | εyy |

|---|---|---|---|

| CR-I | 0.0169 | 0.0050 | 0.0018 |

| CR-K | 0.0131 | 0.0063 | 0.0028 |

| CR-C | 0.0281 | 0.0094 | 0.0062 |

| CR-S | 0.0232 | 0.0063 | 0.0115 |

| Series | (kN·mm) | (kN·mm) | (kN·mm) | (kN·mm) | (kN·mm) | (kN·mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR-I-1 | 18.72 | 14.49 | 42.28 | 31.73 | 61.00 | 46.22 |

| CR-I-2 | 9.75 | 30.19 | 39.94 | |||

| CR-I-3 | 18.77 | 30.96 | 49.73 | |||

| CR-I-4 | 10.70 | 23.51 | 34.21 | |||

| NR-I-1 | 7.36 | 9.53 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 7.36 | 9.53 |

| NR-I-2 | 6.25 | 0.00 | 6.25 | |||

| NR-I-3 | 14.98 | 0.00 | 14.98 | |||

| CR-K-1 | 21.85 | 26.01 | 45.72 | 48.01 | 67.57 | 74.02 |

| CR-K-2 | 19.87 | 58.86 | 78.73 | |||

| CR-K-3 | 44.25 | 47.72 | 91.97 | |||

| CR-K-4 | 18.06 | 39.74 | 57.80 | |||

| NR-K-1 | 23.85 | 23.77 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 23.85 | 23.77 |

| NR-K-2 | 23.96 | 0.00 | 23.96 | |||

| NR-K-3 | 23.50 | 0.00 | 23.50 | |||

| CR-C-1 | 24.73 | 26.89 | 25.94 | 23.24 | 50.67 | 50.13 |

| CR-C-2 | 18.88 | 28.00 | 46.88 | |||

| CR-C-3 | 28.36 | 18.08 | 46.44 | |||

| CR-C-4 | 35.58 | 20.93 | 56.51 | |||

| NR-C-1 | 5.84 | 10.16 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.84 | 10.16 |

| NR-C-2 | 9.43 | 0.00 | 9.43 | |||

| NR-C-3 | 15.34 | 0.00 | 15.34 | |||

| CR-S-1 | 32.33 | 32.91 | 37.18 | 28.16 | 69.51 | 61.07 |

| CR-S-2 | 32.66 | 19.42 | 52.08 | |||

| CR-S-3 | 38.32 | 22.97 | 61.29 | |||

| CR-S-4 | 28.33 | 33.06 | 61.39 | |||

| NR-S-1 | 25.32 | 19.28 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 25.32 | 19.28 |

| NR-S-2 | 10.89 | 0.00 | 10.89 | |||

| NR-S-3 | 21.64 | 0.00 | 21.64 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sun, C.; Chu, Z.; Luo, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, Q.; Singh, A. Shear Performance of Reinforced 3DPM-NM Specimens with Different Interface Locking Designs. Buildings 2026, 16, 626. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030626

Sun C, Chu Z, Luo Y, Li L, Liu Q, Singh A. Shear Performance of Reinforced 3DPM-NM Specimens with Different Interface Locking Designs. Buildings. 2026; 16(3):626. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030626

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Chang, Zhipeng Chu, Yijing Luo, Long Li, Qiong Liu, and Amardeep Singh. 2026. "Shear Performance of Reinforced 3DPM-NM Specimens with Different Interface Locking Designs" Buildings 16, no. 3: 626. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030626

APA StyleSun, C., Chu, Z., Luo, Y., Li, L., Liu, Q., & Singh, A. (2026). Shear Performance of Reinforced 3DPM-NM Specimens with Different Interface Locking Designs. Buildings, 16(3), 626. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030626