1. Introduction

The built environment, as a primary setting for human activity, plays a pivotal role in shaping occupants’ health, well-being, and overall quality of life. Numerous studies have demonstrated that indoor environmental factors, including acoustic [

1], light [

2], thermal [

3,

4], and air quality [

5], significantly impact students’ cognitive performance and mental health. For instance, Pellegatti et al. indicated that ventilation-related noise in classrooms interferes with speech perception and attention, negatively affecting learning outcomes [

6]. Bhattacharya et al. emphasized that optimizing educational space lighting is a key factor influencing student cognitive performance [

7]. Du et al. found that the school ventilation systems directly impact indoor air quality and student health [

8]. These studies reveal the importance of Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ) in educational settings, where suboptimal conditions can harm physical health [

9], induce psychological stress, and decrease academic performance [

10,

11]. However, such research has predominantly focused on learning spaces such as classrooms and libraries, with far less attention given to dormitory environments. University dormitories, as essential components of the higher education environment, serve not only as core living spaces for students [

12,

13] but also as crucial venues for studying, socializing, and personal development [

14]. Consequently, contemporary dormitory design has evolved from merely “economical and practical” [

2] to broader consideration of IEQ’s comprehensive impact on occupants’ well-being and learning efficiency [

13,

14,

15].

Existing research on dormitory environments has primarily concentrated on assessing IEQ. For example, Liu et al. investigated the influence of window orientation, floor level, and time on indoor ventilation rates in dormitories, identifying window orientation and seasonal variations as key determinants of natural ventilation effectiveness [

16]. Yang et al. analyzed ventilation conditions in dormitory corridors, finding that natural ventilation was superior in external corridors compared to internal ones [

14]. Wu et al. explored the effect of long-term indoor thermal history on students’ physiological and psychological responses, finding no significant impact of thermal history on physiological reactions or induced psychological adaptation [

17]. And Wang et al. studied PM2.5-related heavy metal components in dormitories, indicating that heavy metals primarily originated from coal and industrial combustion [

12]. While these studies have enhanced our understanding of dormitory IEQ from various perspectives, they primarily address the environment at a macro-scale. Potential micro-environmental variations and their corresponding physiological and perceptual impacts, particularly those arising from ubiquitous bunk bed layouts, remain inadequately investigated.

Bunk beds are a prevalent spatial arrangement in Chinese university dormitories, addressing high-density accommodation needs [

18]. This layout creates potential micro-environmental differences between the upper bunk and lower bunk, which may include, but are not limited to (1) thermal gradients [

19,

20], where warmer air may accumulate near the ceiling (closer to the upper bunk) and cooler air settles near the floor (closer to the lower bunk), potentially affecting thermal comfort; (2) light exposure intensity and distribution [

2,

21], as the upper bunk is typically closer to overhead lighting, which may influence circadian rhythms and alertness; (3) local airflow and ventilation rates [

16,

22], which may vary with vertical position, impacting air quality perception; (4) the acoustic environment [

23,

24], where the upper bunk might be farther from floor-level noise sources; and (5) spatial perception and privacy [

25,

26], with the upper bunk offering a more elevated, overarching field of view. These physical disparities might exert distinct physiological effects and influence psychological perception, ultimately affecting overall comfort. However, current research involving bunk beds often focuses on their impact on infectious diseases and mental health issues [

27] or explores satisfaction solely from a spatial layout perspective. For example, Loder et al. showed that bunk bed use is associated with fall risks, particularly in prison settings for individuals with conditions like epilepsy [

28]. Zhao et al. evaluated various dormitory types, including those with bunk beds, finding higher student satisfaction with single and double rooms with balconies [

13]. Consequently, while the existing literature addresses the overall dormitory environment or the macro-design of bunk beds, a critical gap exists in systematically quantifying and comparing the physiological and psychological comfort experienced by occupants of the upper versus lower bunk, taking into account the integrated effect of these micro-environmental factors.

To explore the specific impact of this particular spatial layout on students, a review of prevalent research methodologies is warranted. Current methodologies can be broadly categorized into subjective reporting and objective measurement. For instance, van den Bogerd et al. used questionnaires to measure students’ perceptual evaluations in three natural classroom environments, finding a preference for classrooms with indoor plant properties [

29]. Liu et al. employed questionnaires to investigate student perceptions of temperature and air quality in seven different classroom types, suggesting that occupants’ acceptability of indoor air quality is primarily influenced by thermal sensation [

30]. While these methods effectively capture user satisfaction with spaces, they are susceptible to social desirability bias, transient mood fluctuations, and recall bias [

31]. On the other hand, some studies focus on objective physiological indicators. For example, C.A. Tamura et al. analyzed the potential effects of different lighting conditions on human skin temperature (Tsk), finding that suppressing the brightness and color temperature of natural light affected the Tsk change rate [

32]. Kim et al. investigated the association between indoor thermal environment and human blood glucose and cortisol levels to propose a high-accuracy thermal comfort prediction model [

33]. A key limitation of the existing research is the predominant reliance on either subjective or objective methods, seldom combining them. This disconnect hinders a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms underlying environmental impacts on users’ psychophysiological responses.

To bridge this gap and capture a more holistic response, the present study introduces a methodological approach by combining immersive virtual reality (VR) simulation with synchronized multimodal measurement. This approach aims to overcome the limitations of singular research methods and achieve a synergistic analysis of subjective perception and objective physiological responses. Specifically, this study addresses the following core questions: (1) Do bunk bed positions (upper bunk versus lower bunk) induce significantly different physiological reactions in users? (2) How does bed position affect users’ psychological states? (3) Are there correlations between the measured physiological and psychological indicators? To this end, this study integrates subjective psychological scales with objective physiological indicators for data triangulation and cross-validation. Recent interdisciplinary studies have successfully combined EEG, HRV, and POMS to assess human responses to indoor environments [

34,

35,

36,

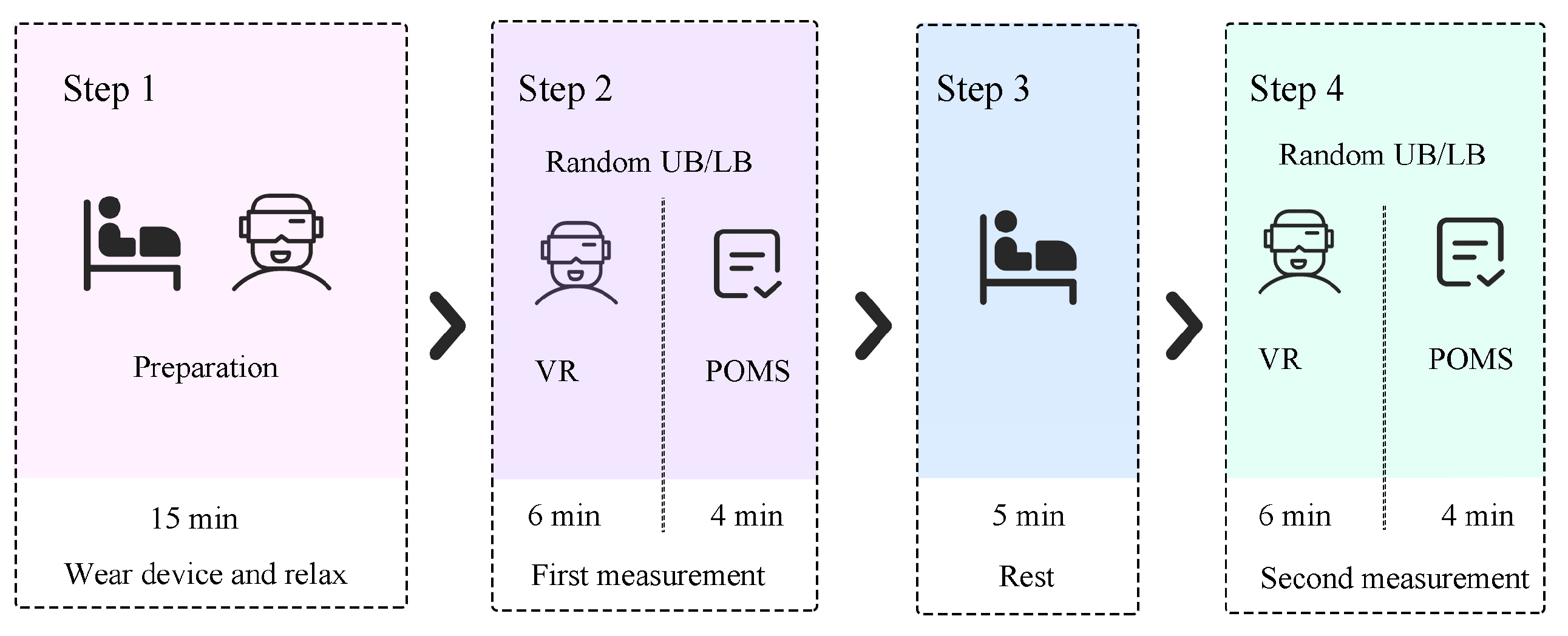

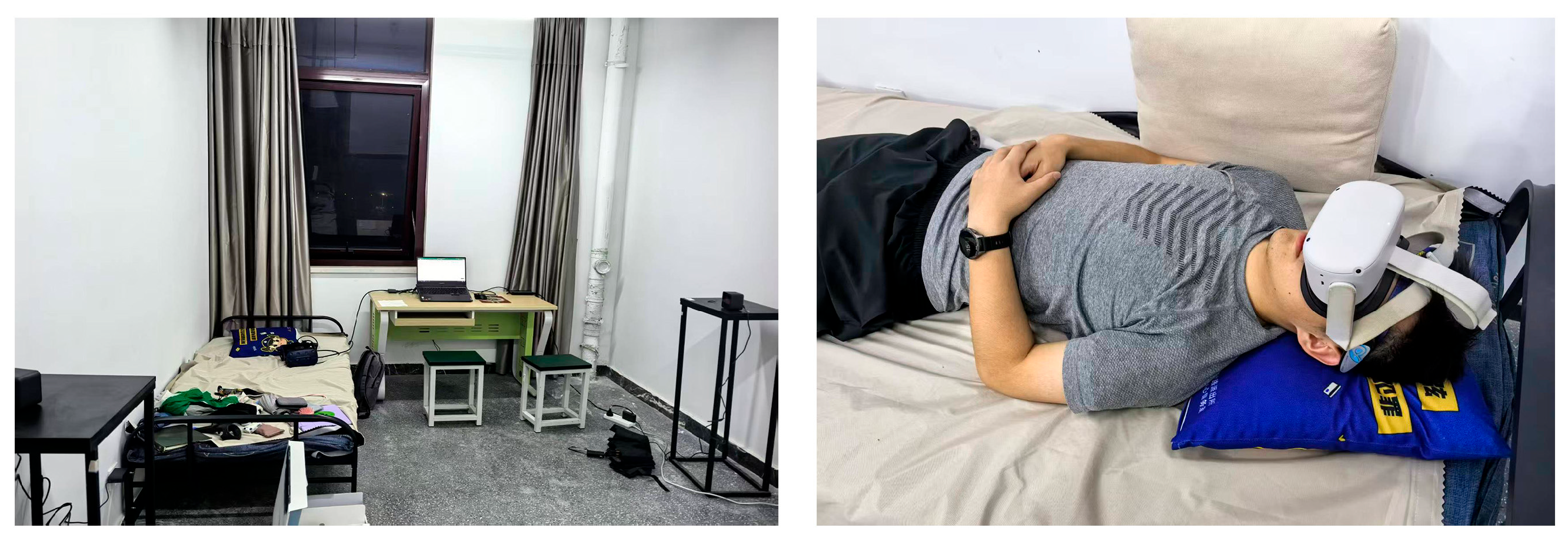

37]. Following this integrative paradigm, the study employs electroencephalography (EEG), heart rate variability (HRV), and the Profile of Mood States (POMS) to holistically investigate the impact of bunk bed position on users’ physical and psychological comfort. Through a controlled experiment, differences in various indicators were compared among participants in simulated upper bunk and lower bunk environments. Twenty-eight healthy university students were recruited, and a crossover design was employed to control for inter-individual variability. Ultimately, it tested whether there were statistically significant differences in the physiological and psychological indicators of participants under different bunk conditions. The detailed experimental design, key findings regarding physical and psychological comfort, and their implications are discussed in subsequent sections.

4. Discussion

By measuring physiological (EEG, HRV, HR) and psychological (POMS) indicators of participants in the UB and LB, this study systematically revealed the differential impact of bed position on physical and psychological comfort. The results suggest that the UB is associated with significant advantages in promoting physiological relaxation and positive psychological emotions under the experimental conditions. These associations may contribute to enhanced overall student comfort. Furthermore, gender was found to moderate individual comfort responses to the UB and LB to some extent.

To provide a clear overview of the differential impact of bunk position,

Table 8 synthesizes the physiological and psychological indicators that showed statistically significant differences between the UB and LB. Indicators without significant differences are not included for conciseness.

In the physiological dimension, the UB significantly enhanced the relaxation state. It is proposed that the top-down view from the UB provides occupants with visual dominance over the room, potentially enhancing their sense of environmental control. This, in turn, may reduce sympathetic nervous system excitation and promote physiological calm [

60], a mechanism consistent with the observation of a significantly lower HR in the UB (

p = 0.042). Additionally, compared to the obstructed LB, the UB typically enjoys more sufficient lighting conditions. The significant increase in Delta waves in the UB (

p = 0.039) suggests a more relaxed state in this environment. This finding aligns with the concept of Perceived Environmental Control, which posits that a sense of mastery over one’s surroundings—such as the broader visual field and greater spatial dominance afforded by the UB—can reduce stress and promote relaxation [

61], offering a coherent explanation for the observed neural state within the context of our short-term, visually driven experiment. Conversely, the LB, due to its lower ceiling height and greater openness, may cause individuals to maintain a vigilant state to guard against potential disturbances, potentially activating neural pathways related to spatial pressure [

62,

63], manifested as a significant increase in High Beta (

p = 0.009) and elevated HR. Furthermore, although the environmental change between UB and LB did not cause significant changes in HRV indicators in this experiment, the observed trend of a higher mean HRV in the UB could be interpreted as it being more conducive to autonomic balance, consistent with restorative environment theories. The significant change in HR, however, might suggest that HR is a more immediately sensitive indicator to the specific visual-spatial change manipulated in this study [

64].

Psychologically, the UB was found to help enhance positive emotions and psychological vitality. The significant increase in Vigor (

p = 0.032) and significant decrease in TMD (

p = 0.038) in the UB indicate that students felt psychologically more at ease. This could be because the relative isolation of the UB distances individuals from activity interference in the dormitory aisle, helping to alleviate psychological fatigue caused by the overuse of directed attention [

65], thereby enhancing psychological comfort. Conversely, the increased average Depression and TMD values for participants in the LB further indicate the LB’s negative impact on emotional comfort.

This study also found that gender moderate the perception of comfort in bunks. Physiologically, males exhibited more stable physiological states in the UB, but their HR fluctuation amplitude between UB and LB was greater than that of females. This suggests that males’ physiological responses to environmental changes may be more sensitive, a result consistent with the findings of Jin’s study [

34]. Psychologically, males’ emotional changes were relatively moderate, while females showed increased Depression and TMD values in the LB, and the gender difference in ΔVigor reached a significant level (

p = 0.045), reflecting females’ higher emotional sensitivity to spatial openness and social exposure. This finding aligns with Taylor et al.’s “tend-and-befriend” stress model [

66], which posits that females have evolved a heightened sensitivity to environmental threats, potentially explaining the greater limbic system sensitivity to exposed spaces like the LB observed here.

Although some indicators in this study did not reach statistical significance, the observed trends in the data allow for exploratory discussion and may generate hypotheses for understanding the impact of UB and LB. For example, High Alpha waves (associated with relaxation) showed a non-significant but notable tendency to be higher in the UB than the LB (

p = 0.075). This trend, while requiring cautious interpretation, might tentatively align with findings from Jin et al.’s study, which found significantly enhanced High Alpha activity in participants in perceived more “harmonious” indoor environments when investigating Fengshui layouts [

34]. One plausible explanation for the lack of statistical significance could be that the VR technology replicating the visual space but failing to fully restore multidimensional experiences like material sensation and security in real living environments, limiting its stimulation intensity for brain relaxation states. Similarly, the mean HRV was higher in the UB, suggesting that the UB might be more conducive to autonomic nervous system balance, as restorative environments can increase HRV, consistent with Ulrich’s findings [

51]. However, compared to Wu et al.’s study tracking participants’ states over the long term in real dormitories [

17], this study found fewer physiological indicators reaching significance. This difference might be attributed to the experimental duration: as a short-term experiment, this study might be insufficient to induce significant changes in the autonomic nervous system, whereas the cumulative effect of micro-environmental differences over long-term residence is more pronounced. These near-significant trends indicate that the differential impact of UB and LB objectively exists, but its effect size might be influenced by the realism of the simulation, experimental duration, and individual differences.

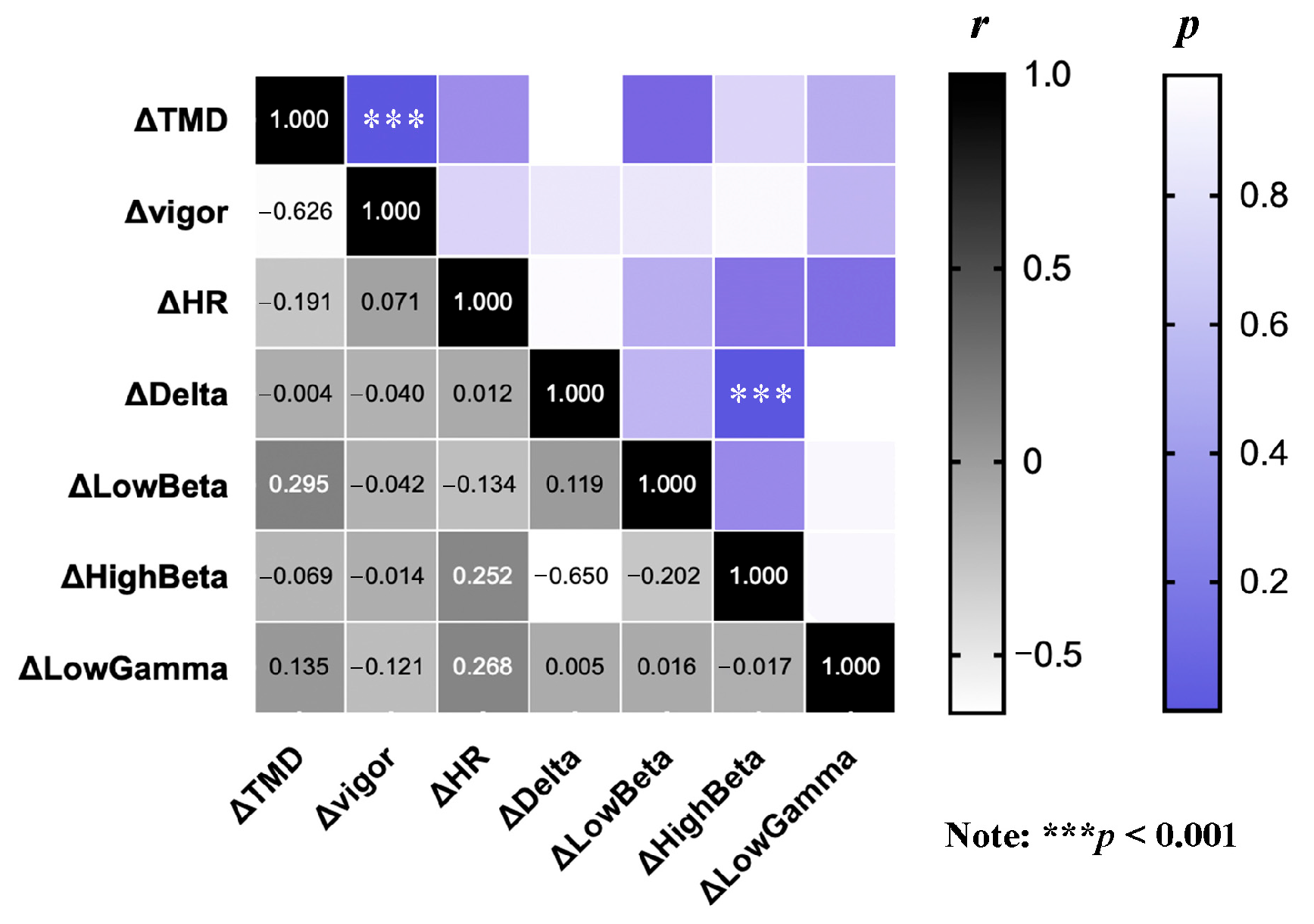

Finally, correlation analysis showed significant co-variation relationships within psychological indicators (between ΔTMD and ΔVigor) and within physiological indicators (between ΔDelta and ΔHigh Beta). However, in the current study, no statistically significant correlation was detected between psychological and physiological indicators. This result suggests that UB and LB environments might affect users through two relatively independent pathways: one is a physiological pathway, where factors such as better lighting and broader view in the UB trigger physiological recovery through fast physiological pathways [

67]; the other is a psychological cognitive pathway, where the privacy and sense of control provided by the UB are perceived by the individual, subsequently enhancing psychological vitality [

65]. The dissociation observed between subjective comfort and objective physiological measurements suggests that these dimensions may be influenced by indoor environments through partially independent pathways. Therefore, future research could employ more complex models to explore the interaction mechanisms between environment, physiology, and psychology. Furthermore, the absence of significant correlations between the psychological and physiological indicators should be interpreted with consideration of statistical power. While this does not invalidate the observed dissociation between these measurement domains, it suggests that a larger sample might have detected weaker relationships. Future studies with larger cohorts are warranted to confirm the independence of these pathways.

5. Conclusions

As core areas for students’ long-term living and learning, the spatial design of dormitories impacts their daily life and academic performance. However, the implications of micro-environmental differences inherent in bunk beds, a common configuration in Chinese dormitories, for student comfort have not been sufficiently explored. This study systematically analyzed differences in users’ physiological and psychological comfort in UB and LB spaces by combining point cloud scanning, VR technology, and physiological and psychological data assessment.

In summary, the quantitative data provide evidence for several key findings. First, the UB space was associated with significantly higher EEG Delta activity (p = 0.039) and lower heart rate (p = 0.042) than the LB, suggesting a physiological state of greater relaxation. Second, psychologically, participants reported significantly higher Vigor scores (p = 0.032) and lower Total Mood Disturbance (p = 0.038) in the UB, indicating better emotional well-being. Third, the LB environment tended to induce higher neural alertness, as shown by significantly elevated High Beta waves (p = 0.009). Furthermore, gender appeared to moderate individual responses in sample: males tended to show greater physiological reactivity to the environmental change, while females exhibited more pronounced changes in emotional state, particularly in Vigor (p = 0.045).

To enhance student well-being in high-density living environments, future dormitory designs should prioritize micro-environmental privacy and personalization. Specifically, for the LB, design interventions such as retractable privacy screens or curtains should be incorporated to mitigate the visual exposure and neural alertness associated with lower-level occupancy. Designers should also include entrance buffer zones or hallways to prevent the main living area from being directly exposed upon entry, which addresses a significant source of psychological discomfort for residents. For the UB, designs should ensure direct lighting to maintain an unobstructed visual field to enhance the occupant’s sense of environmental control and relaxation. Finally, integrating flexible elements like pin-up boards and modular storage solutions can foster a sense of user autonomy, allowing students to successfully negotiate spatial limitations and express their personal identity.

However, the study has several limitations. Firstly, the experiment was conducted in a highly controlled virtual reality scene. While this effectively excluded interference from real environments, the experience was primarily visual and could not fully simulate tactile, olfactory, and other sensory experiences of real dormitory environments. Furthermore, although environmental factors such as air quality, temperature, and humidity were not measured in real-time during the experiment, we ensured that these conditions remained constant and within a comfortable range (maintained by the building’s HVAC system) for each participant across both the UB and LB sessions. This control was implemented to isolate the effect of visual-spatial perspective, which was the primary variable of interest. Consequently, participants’ psychophysiological responses might differ from those in real scenarios. Furthermore, due to constraints of experimental equipment and duration, tracking physiological data for long-term effects was challenging. Future studies should aim to expand sample size, allowing participation of students with different ages, majors, or physiological characteristics. Finally, the conclusions of this study are based on the Chinese university dormitory environment, and their generalizability needs verification considering the spatial layout characteristics of different countries.