1. Introduction

With the deepening advancement of China’s “Transport Power” strategy, the construction of transportation infrastructure represented by expressways is transitioning from large-scale expansion to high-quality development. Due to their long alignment and numerous bridges and culverts, expressways impose extremely stringent requirements on the bearing capacity and stability of their substructure foundations [

1,

2]. Bored piles have become the preferred pile type for critical sections such as expressway bridges and interchanges, owing to their advantages such as flexible adaptability in pile length and diameter, high bearing capacity, and convenient construction [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. However, the economically developed eastern region of China carries heavy traffic volumes and is widely underlain by thick, highly compressible, and low-strength mucky soft soil layers. The unique engineering–geological characteristics of these deposits pose severe challenges to the application of bored piles. First, during pile construction, the borehole wall in such soft strata is prone to diameter reduction and collapse, the thickness of the sediment at the pile base is difficult to control effectively, and a relatively thick mud cake commonly forms along the pile side. These inherent shortcomings of the bored pile construction process significantly weaken the mobilization of both tip bearing and side resistance [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

If the demand for enhanced foundation bearing capacity is met simply by increasing pile length, pile diameter, or the number of piles, the project will not only face the risk of cost overruns but also encounter substantial construction challenges and quality uncertainties due to the difficulties associated with drilling extremely long or large-diameter piles and controlling their verticality [

13,

14]. This may lead to both a waste of material performance and potential safety hazards in engineering practice. Therefore, under the premise of ensuring the structural safety and economy of expressway projects, how to effectively improve the bearing performance of bored piles in deep soft soil layers through new technologies and innovative solutions has become one of the key technical issues urgently needing to be addressed in current expressway construction.

Post-grouting is an active, resource-intensive pile enhancement technique [

15,

16,

17]. Its core mechanism is to inject cement grout under high pressure into the soil at the pile tip and along the pile side through grout pipes pre-installed prior to the casting of the bored pile. Through the penetration, fracturing, and compaction effects of the grout within the surrounding soil, the technique effectively eliminates the adverse influence of pile-tip sediment and side mud cake while improving the physical and mechanical properties of both the pile–soil interface and the soil beneath the pile base. Consequently, it can significantly increase the bearing capacity of a single pile and reduce settlement [

18,

19].

In recent years, with advances in grouting devices and construction techniques, post-grouting has evolved from single-tip or single-side grouting into combined tip-side grouting (CTS grouting) technology [

20]. This integrated approach has demonstrated substantial engineering benefits and strong practical applicability in engineering practice. Therefore, the research and application of post-grouting technology are of significant importance for promoting technological progress and innovation in pile foundation design and construction, and the technique has consequently attracted increasing attention from researchers [

21,

22]. The findings of Zou et al. demonstrate that, during pile tip grouting, the injected grout pre-compresses and densifies the soil within the confined space and subsequently permeates into the surrounding soil to reinforce the pile tip strata [

23]. Ali Mahdavi et al. proposed an improved post-grouted helical pile and demonstrated, through static load tests in sandy soils, the superior bearing performance of post-grouted helical piles [

24]. Zheng et al. employed static load testing and fiber-optic sensing technologies to obtain precise measurements of post-grouted piles, and the experimental data revealed the reinforcement mechanisms associated with post-grouting [

25]. Yu et al. [

26] strengthened full-scale bored piles using post-grouting and subsequently conducted static load tests. The recorded stress–strain data during loading indicated an asynchrony between the mobilization of side resistance and tip bearing in post-grouted piles and further showed that soil depth exerts a significant influence on the side friction mobilized within the same soil layer. Zhou et al. [

27] performed static load tests on post-grouted prestressed high-strength concrete (PHC) pipe piles and compared their bearing characteristics with those of conventional bored piles. The analysis demonstrated that post-grouting markedly increases both side resistance and tip bearing by forming a grout bulb around the pile. In another study, Zhou et al. carried out field tests on piles in highway bridge foundation projects to examine the influence of different drilling methods on the bearing performance of post-grouted piles and provided detailed insights into the mobilization patterns of side and tip resistances [

28]. Liu et al. [

29], focusing on the engineering characteristics of collapsible loess, used large-scale physical model tests to investigate the load-transfer behavior of post-grouted piles in loess regions. Based on these results, they established load-transfer curves applicable to post-grouted piles in collapsible loess, offering technical guidance for engineering practice in such areas. Based on experimental data, Wu et al. developed a pile tip resistance-displacement model for post-grouted piles that innovatively incorporates both the grout-induced reinforcement effect and the modulus-degradation effect of the surrounding soil [

30].

Extensive research and engineering practice have demonstrated that post-grouting is an effective pile-reinforcement technique capable of significantly enhancing the bearing capacity of bored piles, with increasing attention being paid to CTS grouting in recent years [

31]. However, existing studies largely focus on the overall improvement in service performance brought about by post-grouting, while systematic analyses of different grouting modes and their underlying mechanisms remain limited. In particular, the mechanisms by which various grouting approaches influence the bearing performance of piles in coastal soft soil areas have yet to be fully elucidated.

To address these issues, this study conducts comprehensive field tests on post-grouted piles in coastal soft soil to examine the enhancement effects of different grouting modes on pile bearing performance. On this basis, the influences of distinct grouting approaches on the mobilization of pile-tip resistance and side resistance are further investigated. Subsequently, the underlying mechanisms associated with each grouting mode are revealed through the standard penetration test (SPT) and borehole coring test. Finally, PLAXIS finite element simulations are employed to analyze the effects of pile-tip grouting parameters on the bearing behavior of tip-grouted piles.

2. Site Information and Testing Program

2.1. Site Information

The project is located in the eastern Zhejiang coastal alluvial plain, characterized by flat terrain typical of alluvial plain geomorphology. The upper strata, from top to bottom, consist of soft plastic mucky clay, mucky silty clay, hard plastic silty clay, clay, medium-dense silt, medium-dense fine sand, medium-dense medium sand, and medium-dense coarse sand (locally interbedded with medium-dense fine sand). These soils exhibit poor engineering properties, with a thickness of approximately 12–45 m, and are unsuitable as bearing layers for foundations.

The underlying strata comprise gravelly sandstone and rounded gravel. The gravelly sandstone is completely to moderately weathered, while the rounded gravel deposits exhibit medium-dense to dense conditions, interbedded locally with medium-dense fine sand, medium-dense sand, and plastic cohesive soil. These layers possess favorable engineering characteristics and are suitable as bearing strata for pile foundations. The site is situated within a gently inclined bedrock zone, where the bedrock surface lies at a relatively stable depth of 50–60 m.

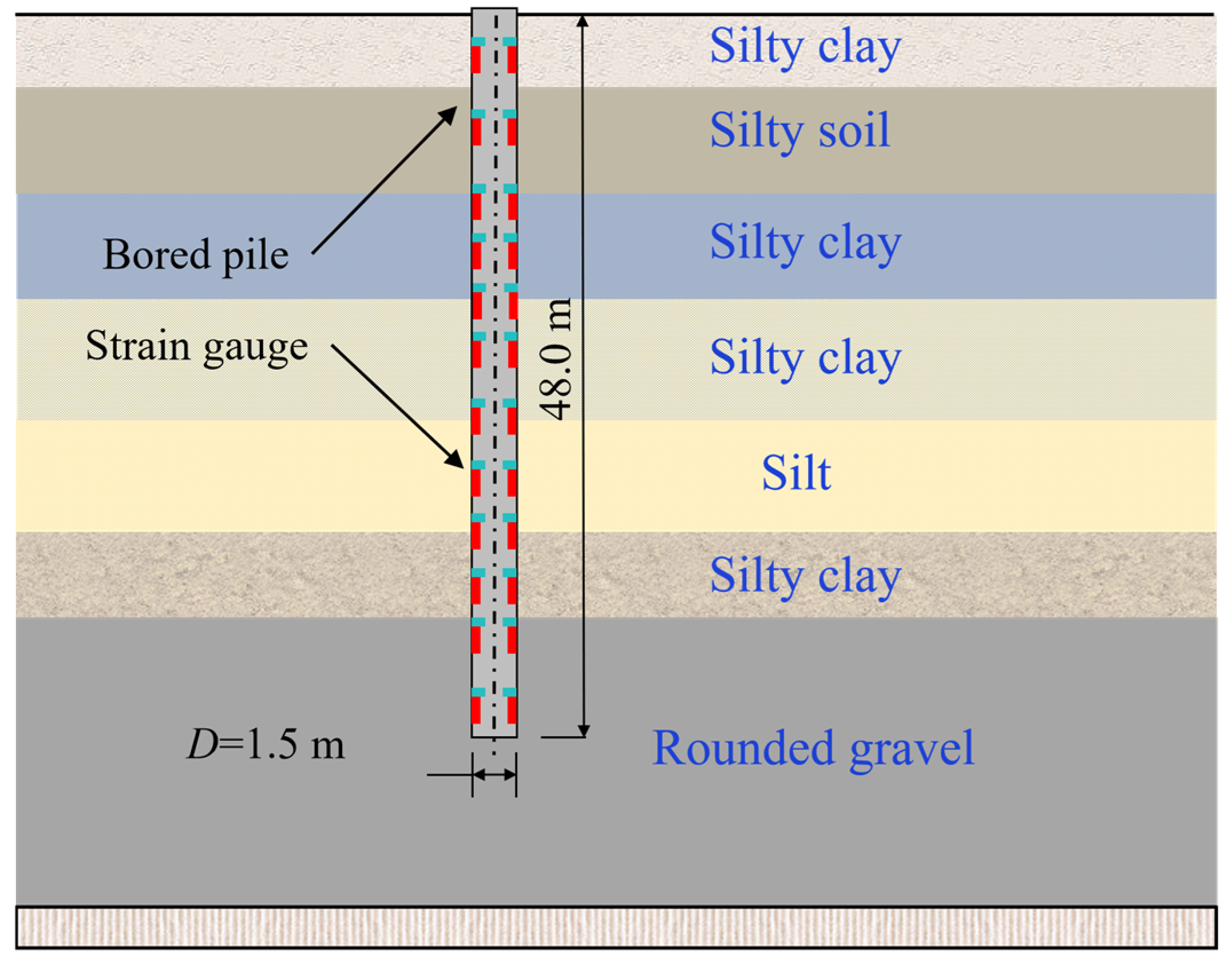

Figure 1 and

Table 1 present the geological conditions of the project site. The stratigraphic information revealed by boreholes adjacent to the pile test areas in the geological data is basically consistent; therefore, the variability of soil layer parameters across different pile test areas can be largely neglected.

2.2. Grouting Scheme

The piles used in the static load tests in this study were all single piles, each with a length of 48 m. Based on geological survey information and the conditions encountered during bored pile construction, it is judged that increasing the length (

L) or diameter (

D) to improve pile bearing capacity would be of very limited effectiveness while substantially increasing construction difficulty and resulting in borehole collapse. To verify the positive effects of post-grouting on the bearing performance of bored piles in coastal soft soil areas and to further conduct a refined analysis on the applicability of different grouting modes, three post-grouted test piles were constructed in this project, each employing a distinct grouting approach. The detailed grouting design parameters for each test pile are presented in

Table 2. Specifically, test pile PT1 adopted tip grouting, PS2 adopted side grouting, and PC3 employed a CTS grouting scheme.

For the execution of tip grouting, straight grout pipes were first connected to grouting valves, then securely bound to the inner side of the reinforcement cage, and were ultimately positioned at the pile tip zone to complete the grouting setup. For side grouting, an annular pipe system was used, with grouting valves uniformly distributed around the pile circumference; its installation method was similar to that of the straight pipes used for tip grouting. The key grouting parameters are presented in

Table 3. The cement type adopted for grouting was Portland cement, with a designed water-cement ratio of 0.6.

To guarantee that the grouting work meets required quality standards, it is essential to finish all necessary preparatory tasks before commencing the formal operation. High-pressure water flushing is first conducted to clean the grout pipes and ensure unobstructed flow throughout the system. For CTS grouting, the operation generally follows the sequence of side grouting first and tip grouting thereafter. If multiple annular grouting pipes are installed along the pile side, the grouting should proceed sequentially from top to bottom. The grout used in this project was prepared with the cement. In the preparation stage, the cement slurry underwent thorough mixing. The slurry tank and on-site grouting processes are illustrated in

Figure 2.

Prior to grouting, the grout pipes must be opened. This operation is typically carried out 12–24 h after concrete casting by injecting high-pressure water into the pipes to activate the grout outlets and clear the grouting channels. Grouting can only be performed after the pile concrete has reached 80% of its design strength and the pile integrity test has confirmed acceptable quality. To guarantee construction quality in the course of grouting, a combined control approach grounded in both grout volume and grouting pressure was employed, with grout volume acting as the primary control parameter and grouting pressure as a secondary control means.

2.3. Field Loading Method and Testing Scheme

The bearing capacity tests for all three test piles were conducted using the Osterberg Cell (O-cell) self-balanced loading method. The self-balanced method is a relatively new approach to static load testing [

32,

33]. In this approach, a custom-designed load cell functions as the loading apparatus and is welded to the reinforcement cage prior to its embedment within the pile. The high-pressure hydraulic pipeline of the load cell is routed to the ground surface, following which concrete placement for the bored pile is carried out. During testing, a high-pressure oil pump is used to pressurize the load cell from the ground surface. The load cell transfers the applied force to the pile body, where the upward resistance mobilized by the upper side resistance and the pile self-weight is balanced by the downward resistance mobilized by the lower side resistance and the ultimate tip resistance [

34,

35]. This internal force equilibrium enables the application of load without external reaction systems.

The O-cell was fabricated concurrently with the rebar cage. During installation, the O-cell was positioned horizontally at the center of the cage to ensure that it remained essentially perpendicular to the rebar cage. The main rebar of the upper cage segment was firmly welded to the upper portion of the O-cell, while that of the lower cage segment was securely welded to the lower portion of the O-cell. All welds were required to meet the strength specifications for O-cell installation to prevent detachment during construction. During the loading test, commercially available vibrating-wire rebar load cells were employed for strain measurement of the pile. These sensing devices were directly welded to the main rebar bars of the cage, thereby ensuring dependable transmission of strain.

2.4. In Situ Testing

The borehole coring test is a widely used inspection method in foundation engineering [

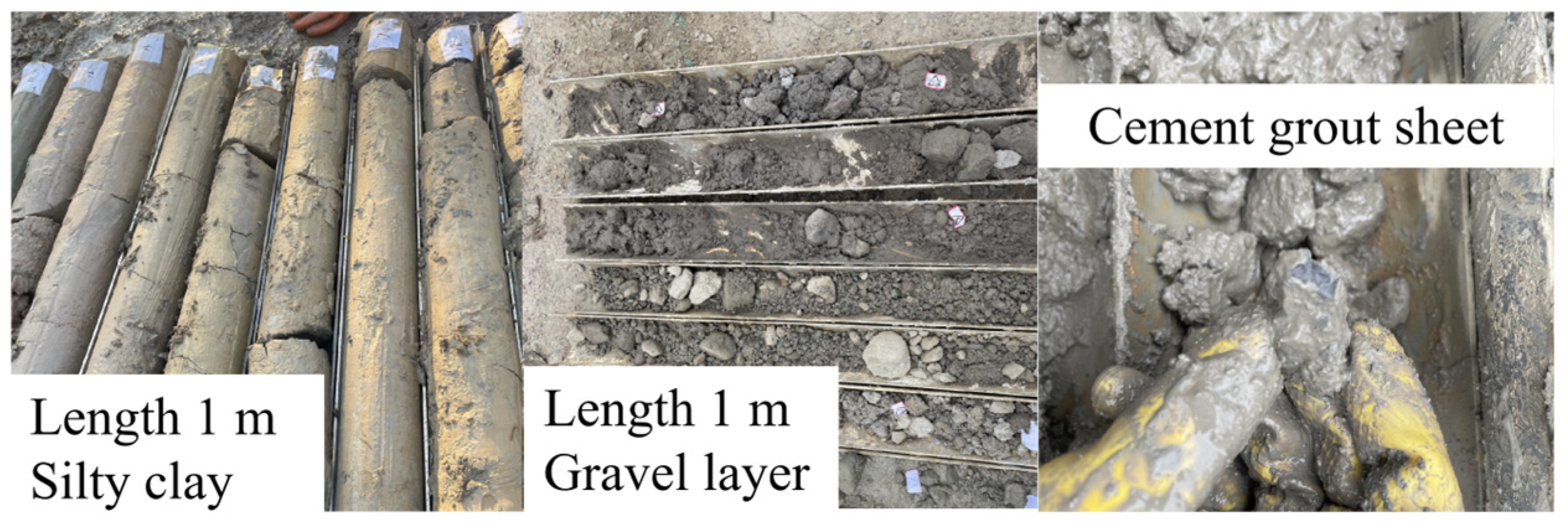

36]. Its principle is based on drilling technology, whereby cylindrical core samples are extracted from the soil adjacent to the pile using specialized drilling equipment, allowing for direct observation and analysis of the soil conditions along the pile side. When applied to post-grouted pile engineering, the borehole coring test plays a critical role owing to its combination of intuitiveness and precision. The recovered core samples enable direct evaluation of the grouting reinforcement effects, including the extent of grout penetration, the spatial distribution of the grout-soil cemented mass, and the predominant modes of grout action. The borehole coring test is shown in

Figure 3.

The SPT is also an important technique for evaluating post-grouted piles, as it can be used to assess improvements in soil mechanical properties before and after grouting [

37,

38]. Post-grouting enhances pile bearing capacity by injecting high-pressure grout to fill soil pores and cement soil particles, and its reinforcement effects on the surrounding strata must be verified through quantitative indicators. The SPT measures the number of hammer blows (

Ns value) required to drive a sampler into the soil at various depths. By comparing

Ns values at the same depth before and after grouting, the improvement in soil density and the increase in soil strength can be directly inferred. The SPT is often used in conjunction with borehole coring, forming a combined qualitative-quantitative assessment system that enables a comprehensive evaluation of the construction quality and bearing reliability of post-grouted piles. The hammer for the SPT is shown in

Figure 4.

3. Test Results and Analysis

3.1. Load-Settlement Response

The load-settlement (

Q-

S) curves of the test piles are shown in

Figure 5. Before grouting, the

Q-

S curves of all three tested piles displayed a linear elastic response during the initial loading period, with the curve slope undergoing a relatively minor variation. With the gradual increase in applied load, the slope of the curves progressively increased, indicating that smaller load increments corresponded to increasingly larger settlement increments. After grouting, the initial gradient of the

Q-

S curves for every grouted pile proved notably higher in comparison to the ungrouted one. In the later stage of loading, the increase in curve slope became more moderate, and the pronounced slope reduction observed in the ungrouted pile during the late loading stage did not occur. Throughout the entire loading process, under the same incremental load, the settlement increments of the grouted piles were significantly smaller than those of the ungrouted pile. Moreover, at the same load level, the absolute settlement of the grouted piles was consistently smaller.

These results clearly demonstrate that post-grouted piles exhibit superior vertical load-bearing performance. Specifically, the ultimate bearing capacities of the three ungrouted piles were 16.31 MN, 15.80 MN, and 16.10 MN, respectively. After applying different post-grouting schemes, all three grouted piles exhibited notable enhancements in bearing capacity. Among them, the bearing capacities of PT1 and PS2 increased by 58.12% and 37.90%, respectively. A comparative analysis of the improvement ratios indicates that tip grouting provides a more pronounced enhancement in the bearing capacity of bored piles. In addition, the bearing capacity of pile PC3 increased by 73.54% after grouting, representing the greatest improvement among the three grouted piles. This is because PC3 adopted a CTS grouting scheme, and thus its improvement in bearing capacity was more significant than that achieved by either tip grouting or side grouting alone.

3.2. Distribution of Side Resistance

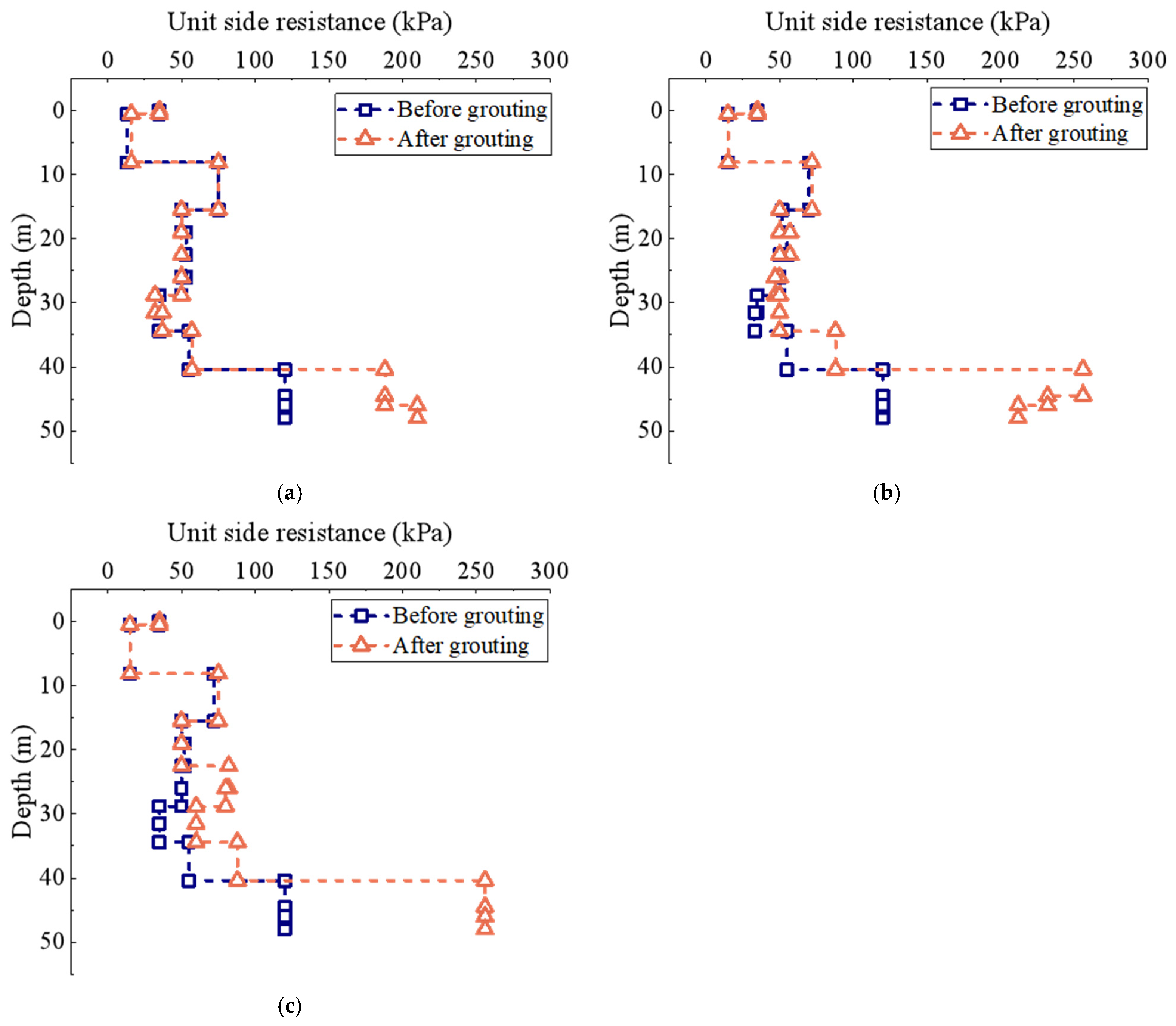

The distribution of side resistance along the three test piles is illustrated in

Figure 6. As shown, different grouting schemes exert distinct influences on the side resistance profiles. Although PT1 adopted a tip-grouting scheme, its side resistance near the pile tip still exhibited a noticeable increase. This is attributed to the fact that the bearing stratum consists of a gravel layer with large pore spaces, which provides favorable conditions for the upward diffusion and downward infiltration of the grout. The grout injected at the pile tip migrated upward through the voids between gravel particles, resulting in enhanced side resistance in the vicinity of the pile tip.

For PS2, the side resistance began to increase at approximately 19 m above the pile tip after grouting, and the side resistance at various elevations along the pile showed improvements of different magnitudes. This can be explained by the upward and downward seepage of cement grout along the pile-soil interface under high pressure. After hardening, the grout improved the mechanical properties of the interface, thereby increasing side resistance. PC3 adopted a CTS grouting approach. After grouting, the side resistance began to increase at about 26 m above the pile tip, and the resistance within the affected zone was significantly enhanced.

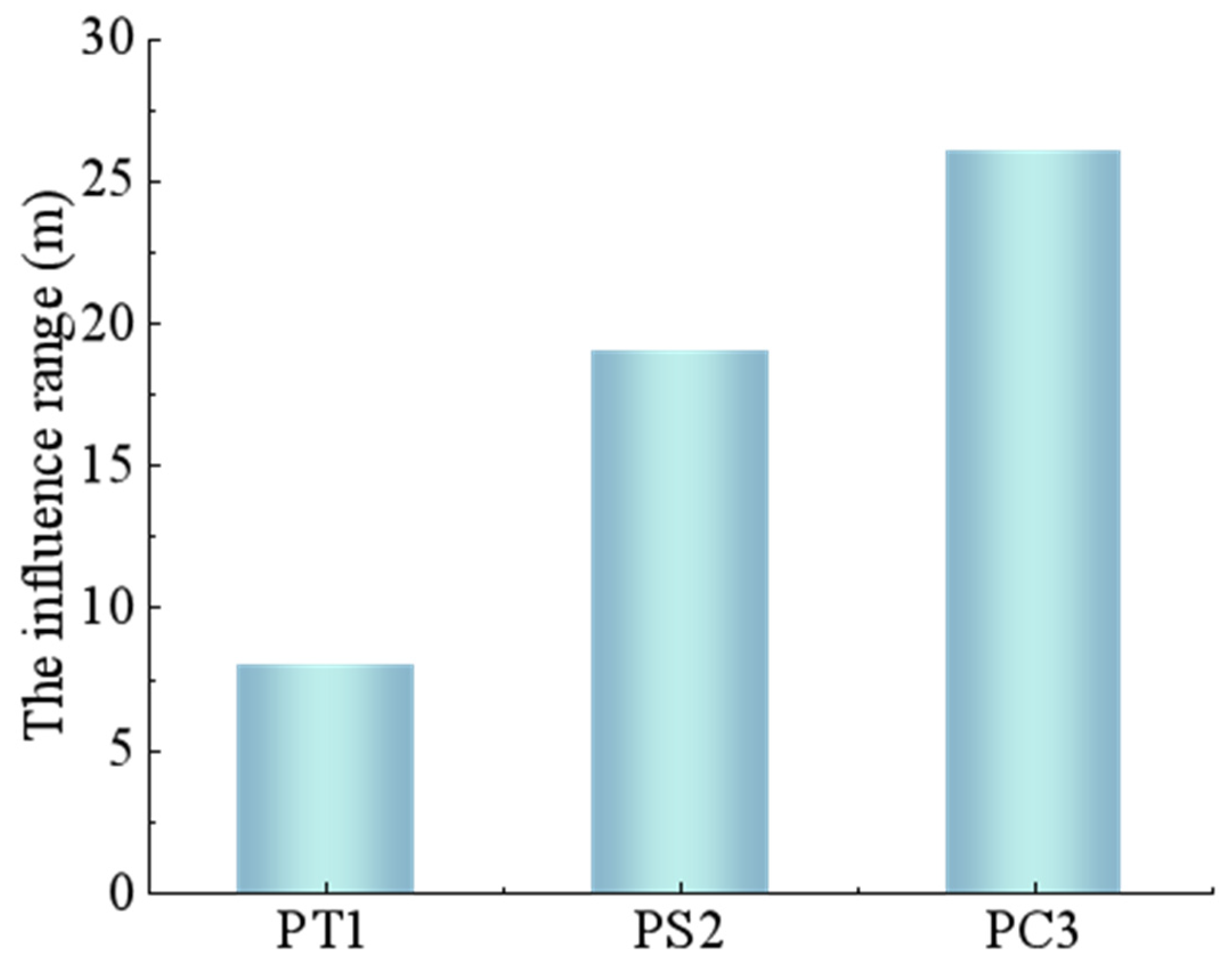

It is noteworthy that different grouting methods exhibit distinct influence ranges and degrees of effectiveness on the pile side resistance. The side resistance improvement ranges for PT1, PS2, and PC3 are 8 m, 19 m, and 26 m, respectively. Clearly, combined grouting exerts the greatest influence on the side resistance, followed by side grouting and then tip grouting. This is because the effect of tip grouting on side resistance relies only on partial reverse diffusion of the grout. To more clearly quantify the degree of influence on side resistance, the depth range of 22.5–40.5 m is uniformly defined as the soil layer, and the range of 40.5–48 m is defined as the gravel layer. Through computing the weighted average side resistance of the soil and gravel layers before and after the grouting process, the influence exerted by different grouting methods on pile side resistance can be separately measured quantitatively.

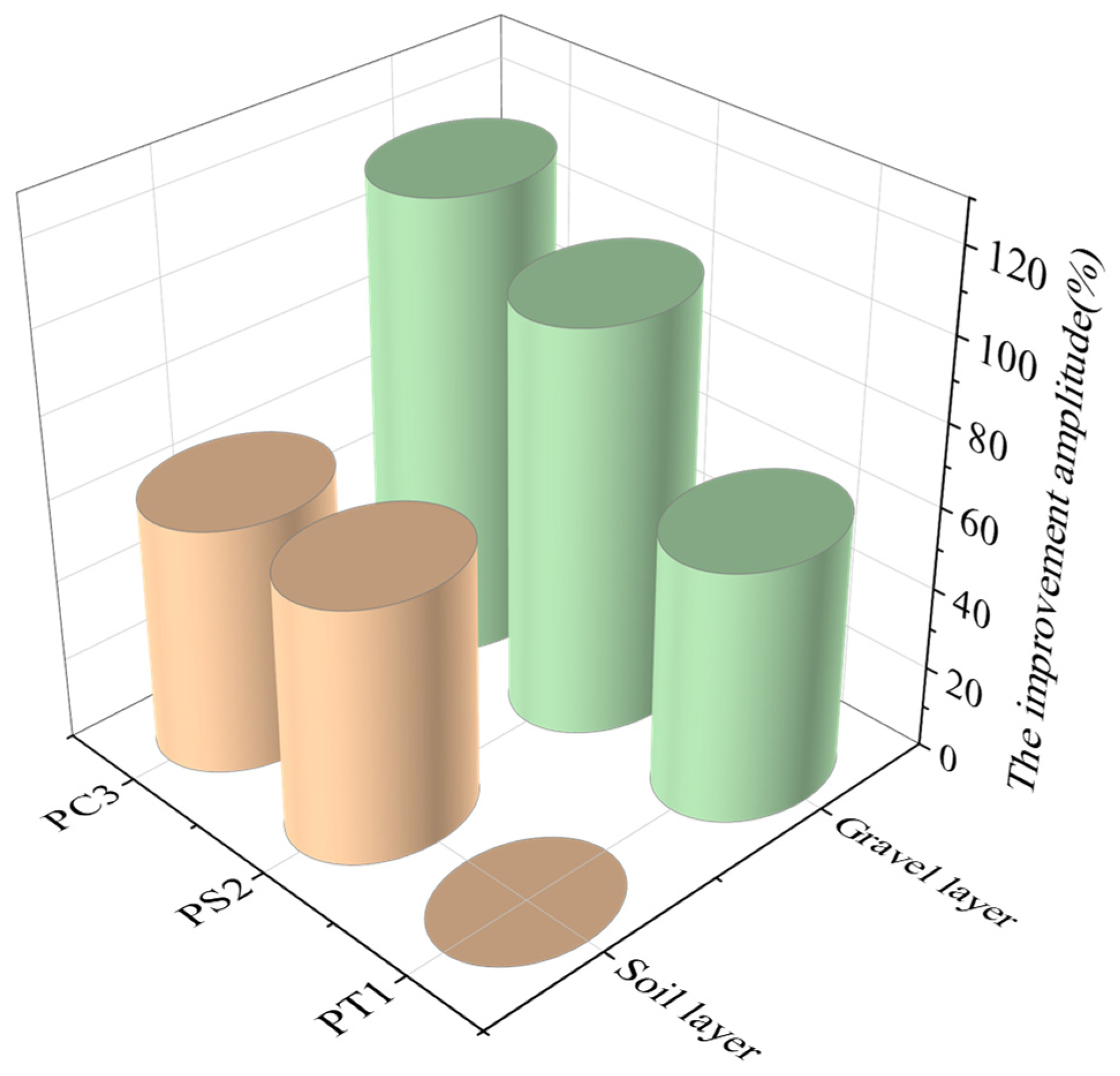

As shown in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, PT1 has a limited influence range on side resistance. For the soil layer in the depth range of 22.5–40.5 m, PS2 and PC3 enhance the side resistance by 62.32% and 60.56%, respectively, with no significant difference between them. As for the gravel layer in the depth range of 40.5–48 m, the side resistance improvement rates for PT1, PS2, and PC3 are 61.55%, 99.56%, and 113.3%, respectively. Among them, PC3 achieves the highest side resistance enhancement, followed by PS2. This indicates that in the CTS grouting method adopted by PC3, not only does the reverse infiltration from tip grouting improve the side resistance near the gravel layer, but the side grouting also enhances the side resistance within the gravel layer, resulting in a compounded strengthening effect on the side resistance in the gravel layer.

3.3. Mobilization of Tip Resistance

The O-cell method was employed, enabling direct measurement of the actual mobilization of tip bearing resistance from the lower O-cell.

Figure 9 illustrates the existing differences regarding the effects of various grouting methods on pile tip resistance. Ungrouted stage, the ultimate tip resistance values of PT1, PS2, and PC3 were determined to be 3.55 MN, 3.20 MN, and 3.52 MN in sequence. After grouting, their ultimate tip bearing resistances increased to 9.14 MN, 6.08 MN, and 9.58 MN, representing enhancements of 157.46%, 90%, and 172.16%, respectively. Evidently, tip resistance was substantially improved for all test piles following grouting.

In the ungrouted stage, the tip settlements of piles PT1, PS2, and PC3 under their ultimate loads were 31.02 mm, 31.56 mm, and 30.63 mm, respectively. After grouting, the corresponding tip settlements at the same ultimate load decreased to 21.36 mm, 22.88 mm, and 19.26 mm, representing reductions of 31.14%, 27.50%, and 37.12%, respectively.

3.4. Analysis of Borehole Coring Test Results

Figure 10 shows partial core samples extracted from the test piles. Cement grout was observed in all core samples, although its form, spatial distribution, and pattern varied among the piles. In terms of form, cement grout appeared as thin sheets within the pile-side soil of PS2 and PC3, indicating that side grouting acted on the pile side soil primarily through a splitting grouting mechanism. At the pile tips of PT1 and PC3, cement grout occurred in the form of cement-gravel agglomerates, suggesting that tip grouting acted on the gravel layer predominantly through permeation. Regarding spatial distribution, PT1 and PS2 exhibited cement grout sheets at positions ranging from near to relatively far from the pile tip, reflecting the differences in spatial location between tip and side grouting. In PC3, which employed a CTS grouting scheme, cement grout was observed at both the pile-tip and pile-side locations. With respect to distribution patterns, the number of cement grout sheets observed along the pile side of PC3 was significantly greater than that of PS2. In particular, at the interface between the soil layer and gravel layer near the pile tip, the grout sheets extracted from the pile side of PC3 were larger and more intact, indicating that the CTS grouting scheme provides a composite reinforcement effect on the pile-side soil near the pile tip.

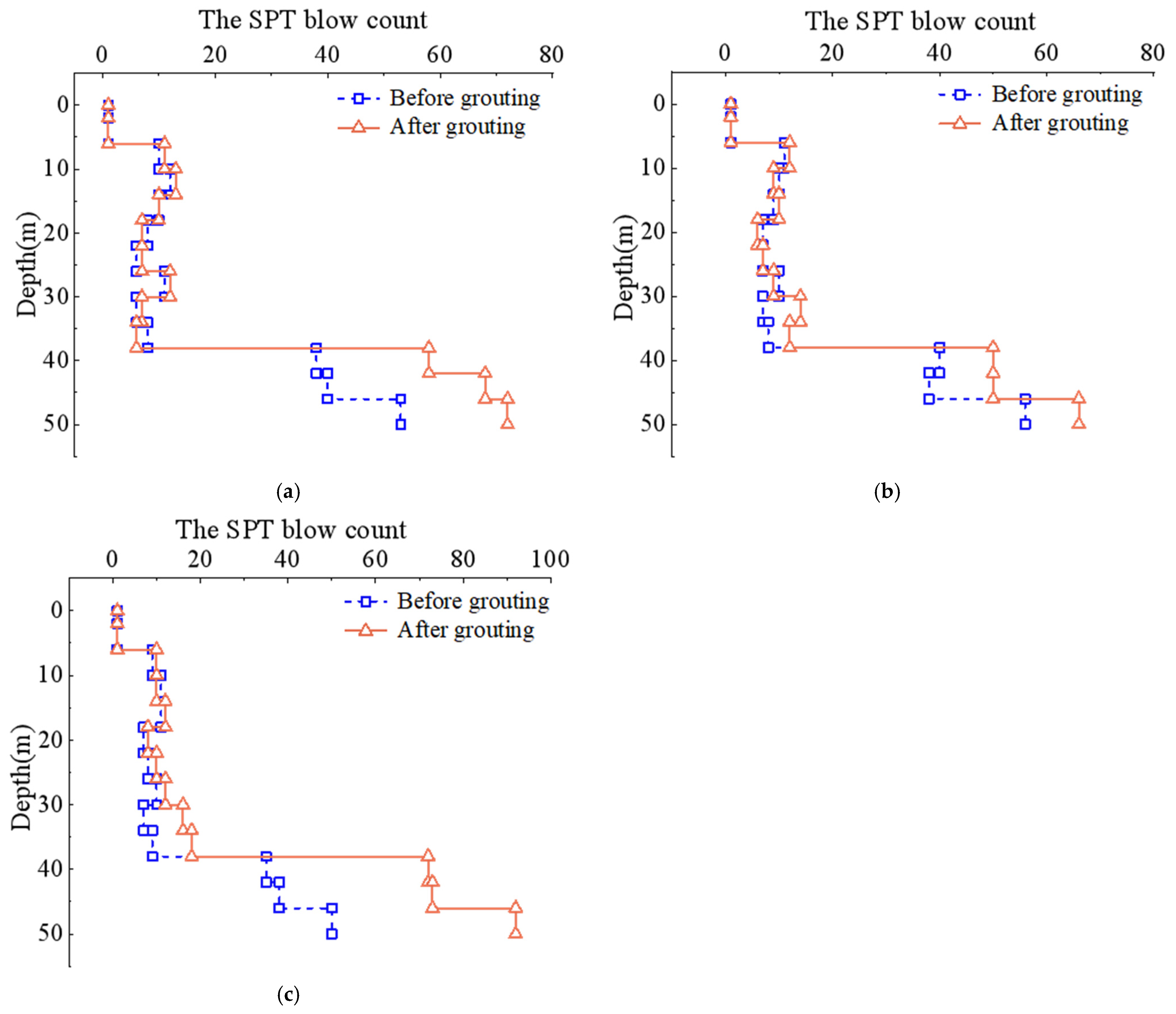

3.5. Analysis of SPT Results

The comparison of

Ns values for piles PT1, PS2, and PC3 before and after grouting is shown in

Figure 11. For the ungrouted piles, the

Ns values generally increased with depth, exhibiting similar trends, with notably high values near the gravel layer. After grouting, all test piles showed significant increases in

Ns values near the pile tip. Specifically, the

Ns values at the pile tip region (42–50 m) for PT1, PS2, and PC3 increased by 85.71%, 31.58%, and 83.9%, respectively. Additionally, for PS2, the

Ns values were enhanced at the location of the side grouting ring pipe, approximately 10 m from the pile tip. For PC3, the

Ns values were improved to varying degrees throughout the 18–40 m depth interval. This result demonstrates that the cement grout delivered through the side grouting pipes has efficiently filled in the defects at the pile-soil interface. After hardening, the grout improved the boundary conditions at the interface and altered the physical and mechanical properties of the surrounding soil, thereby increasing the strength and stiffness of the pile-side soil. As a result, the side

Ns values after grouting were significantly higher than those measured before grouting.

It is noteworthy that the locations along the side of PS2 and PC3 where the Ns values increased most significantly correspond closely to the positions where abundant cement grout sheets were observed. This suggests that side grouting enhances soil strength by forming cement sheets within the soil layers, which function similarly to a “splitting reinforcement” mechanism.

4. Finite Element Analysis

A comparative assessment of the bearing capacity enhancement achieved by the three post-grouted piles reveals that tip grouting exerts a more notable influence on improving pile bearing capacity than side grouting does. Although the CTS grouting achieves the highest increase in bearing capacity, its procedure is more complex and requires more resources than tip grouting alone. Therefore, tip grouting was recommended for this project, making it necessary to further investigate the influence of key tip-grouting parameters on pile load-bearing performance.

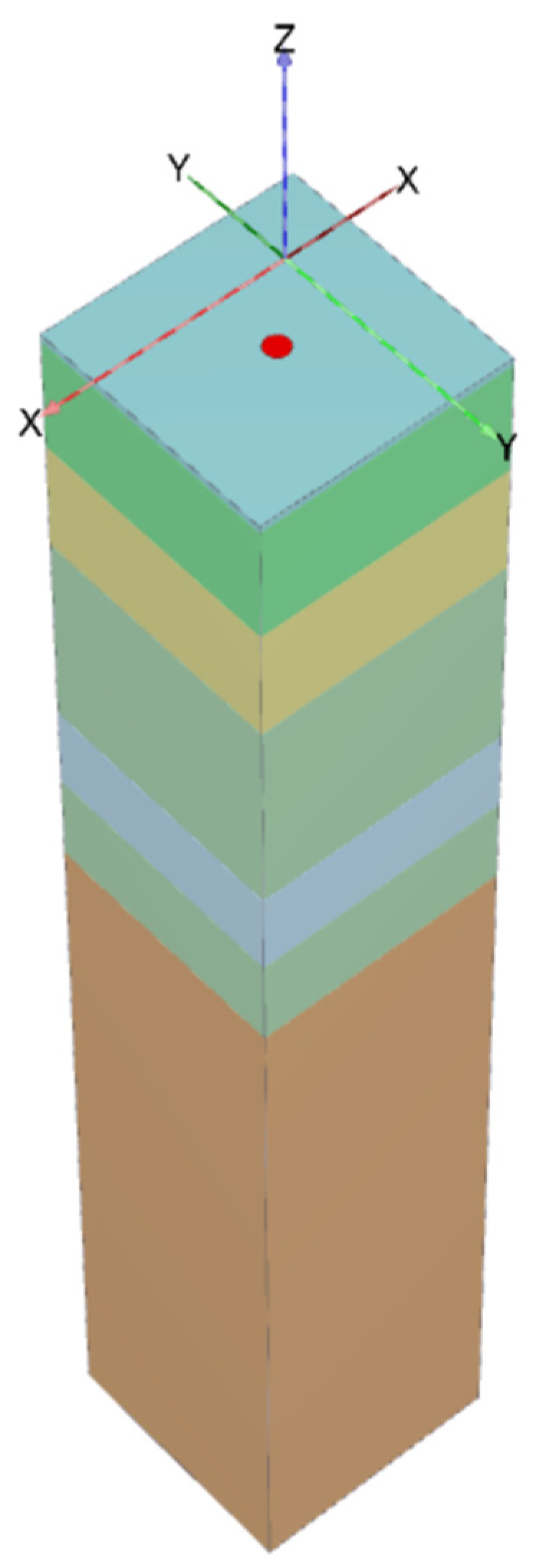

In this section, the geotechnical finite element software PLAXIS 3D CONNECT Edition V22 was used to study the mechanical response of tip-grouted piles. A numerical model was constructed by taking the tip-grouted pile PT1 as the reference scenario, aiming to further explore the impacts of critical parameters on the vertical bearing performance of such grouted piles.

Within practical engineering applications, the reinforcement performance of grouting for bored piles is primarily determined by the strength of the grouting material and the diffusion range of the grout. Concerning the spatial propagation of the grout, earlier studies have demonstrated that the radius of the spherical grout body generated at the pile tip is approximately 1.15–1.9 times the pile’s radius (

R). Based on the grout material strength and grout diffusion range, the modeling cases established for numerical simulation are summarized in

Table 4.

The overall numerical model of the post-grouted pile foundation has dimensions of 12 m × 12 m × 100 m. Based on the results of on-site coring tests, the radius of the solid spherical grout body at the pile tip was set to 1.05 m (1.4

R). The finite element model is shown in

Figure 12. From the perspective of material properties, the Mohr–Coulomb constitutive model was adopted to describe the behavioral characteristics of the soil. The values of the relevant parameters are presented in

Table 1 and

Table 5.

Considering both the rationality of the numerical model and practical engineering feasibility, and in order to focus on the influence of tip-grouting parameters, the following idealized assumptions were introduced in the numerical modeling to simplify model construction and improve computational accuracy and efficiency: (a) The effect of tip grouting on the pile side through upward and downward seepage near the pile tip is not considered [

39,

40]; (b) The cement grout injected at the pile tip is assumed to diffuse uniformly within the gravel stratum and, after cementation and hardening, forms a solid spherical enlargement body. (c) Given the high water content of soft soil strata and the substantial confining pressure exerted by the overlying soil, the stresses induced by autogenous shrinkage and temperature shrinkage of cement are counteracted by the plastic deformation of the soil. Consequently, the risk of cement cracking and the possibility of pile-soil interface debonding are extremely low, justifying the neglect of the effects caused by the shrinkage characteristics of cement materials [

41,

42].

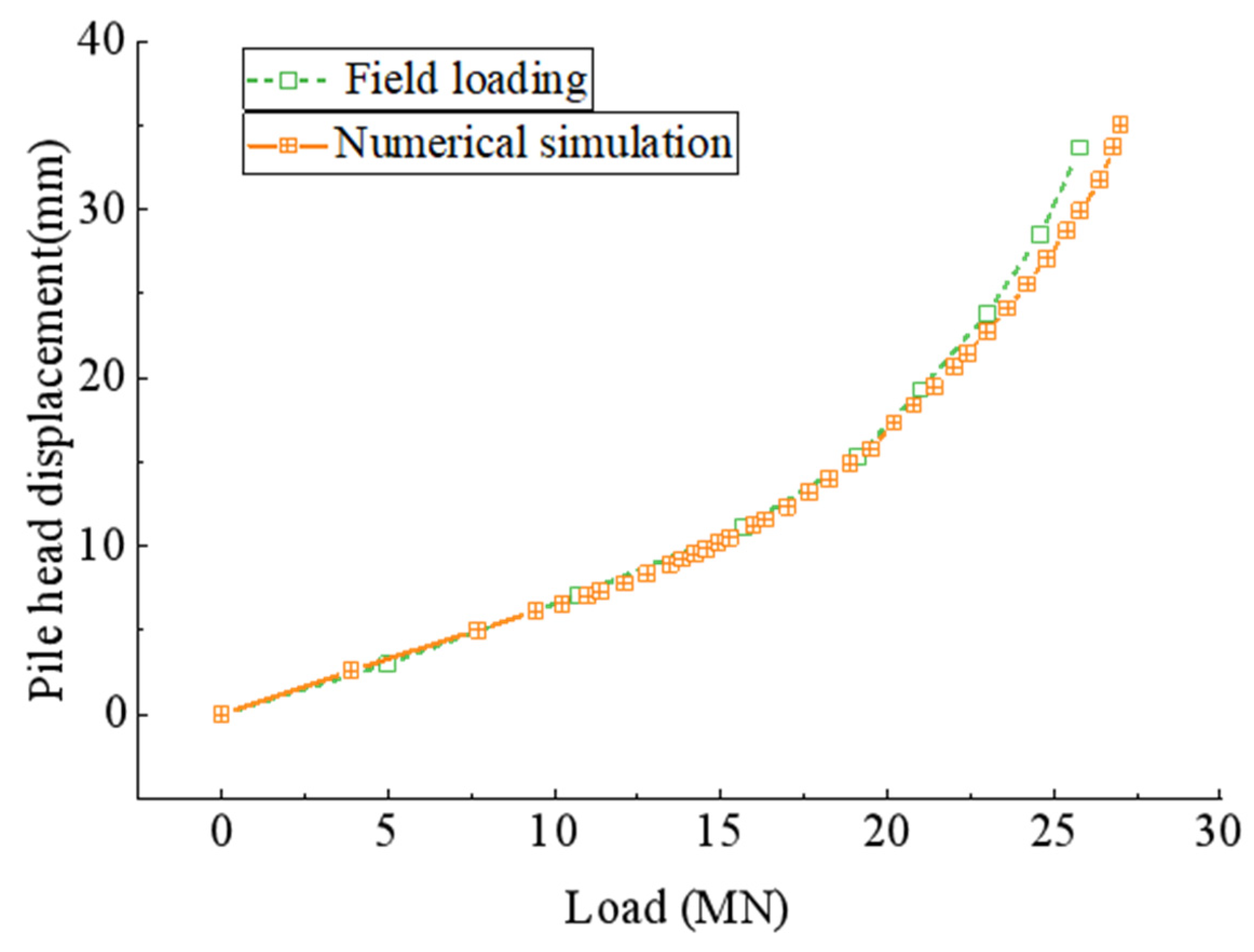

The

Q-

S curve obtained from the finite element analysis of the tip-grouted pile PT1 was compared with the

Q-

S curve measured during the static load test, as shown in

Figure 13. The

Q-

S curve obtained from finite element model analysis exhibits a generally consistent trend with the field-measured

Q-

S curve. During the initial loading stage, pile-head settlement gradually develops with increasing load, and the rate of settlement accelerates as the load continues to increase. Under the same loading conditions, the pile-top settlement predicted by the numerical simulation differs from the measured value by approximately 6%. This level of agreement indicates that the finite element model provides a reasonable validation of the numerical simulation for the pile foundation. Therefore, the tip-grouted pile numerical model can be further used to analyze the influence of different tip-grouting parameters on the bearing performance of post-grouted piles.

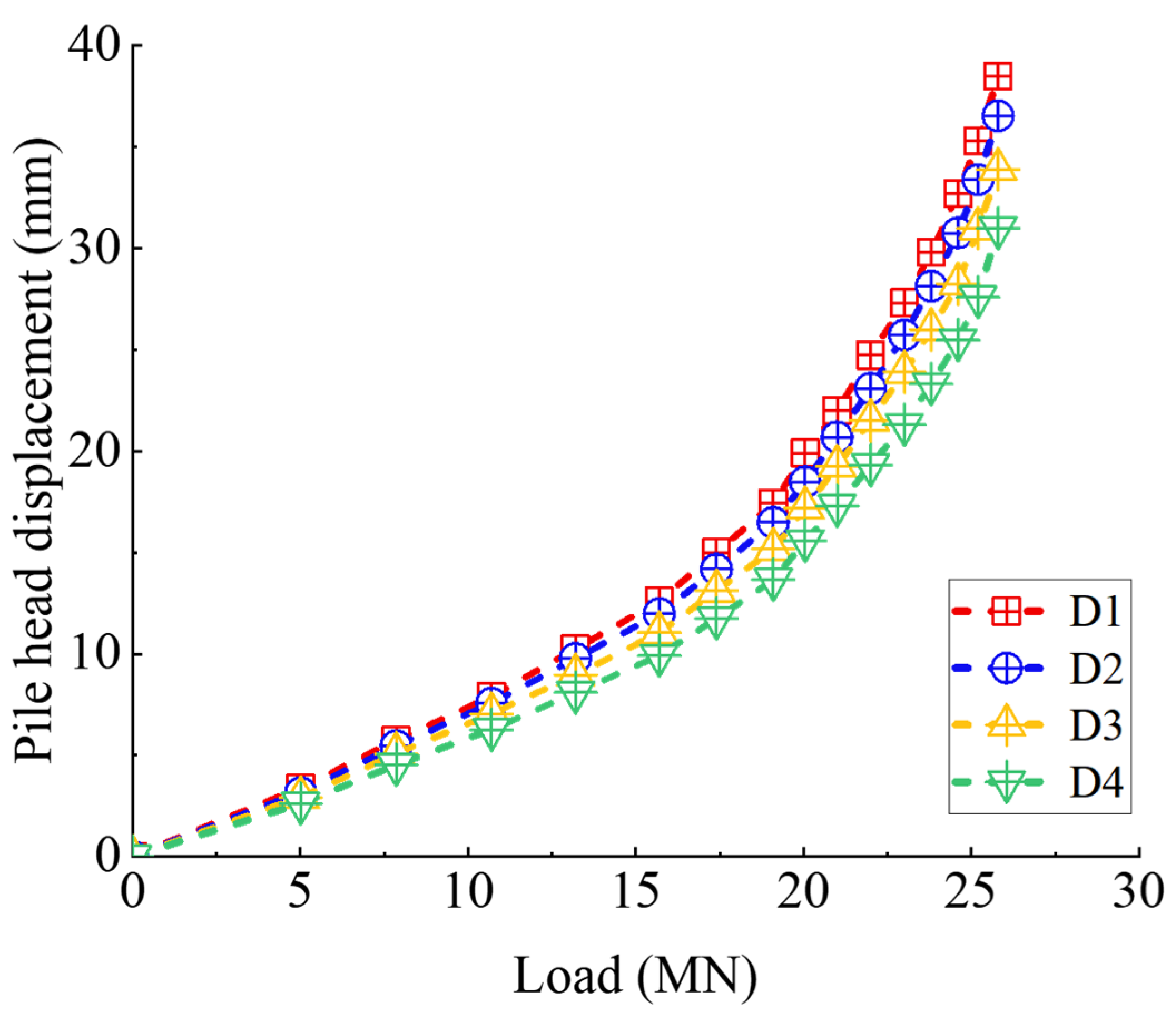

4.1. Grout Material Strength

The

Q-

S curves of tip-grouted piles with different strengths of spherical grout bodies are shown in

Figure 14. As the strength of the hardened grout spheres increases, the bearing capacity of the tip-grouted piles shows slight improvement, and pile-top settlement under the same load is marginally reduced. Although increasing the strength of the grout spheres has a limited effect on enhancing the bearing performance of tip-grouted piles, this result is still positive.

In the meantime, it is indicated that modifying the strength of cement-based grout materials exerts barely noticeable effects on improving the bearing capacity of tip-grouted piles, thereby resulting in restricted practical benefits when applied extensively in engineering projects.

4.2. Grout Diffusion Range

The volume of the hardened spherical grout body can be controlled by adjusting the grout injection volume and pressure. In particular, in gravel layers with high porosity, increasing the grout volume and injection pressure can expand the diffusion range of the grout, i.e., increase the radius of the spherical grout body. The

Q-

S curves of tip-grouted piles with different radii of spherical grout bodies are shown in

Figure 15. As the radius of the hardened grout body increases, the bearing capacity of tip-grouted piles improves, and pile-tip settlement is effectively controlled. When the radius reaches 1.8

R, the pile-top settlement of the tip-grouted pile is 31 mm, representing 15.16% reduction compared with the baseline condition. It is worth noting that the numerical model assumes that the grout at the pile tip diffuses uniformly in the gravel layer to form an ideal spherical tip bulb, which may lead to a slight overestimation of the pile tip bearing capacity.

This indicates that expanding the diffusion range of the grout by adjusting the injection volume and pressure can significantly control pile settlement, while the associated costs are relatively limited. Therefore, this approach has practical potential for widespread engineering applications.

5. Conclusions

In this study, three test piles were treated with different grouting methods. The effects of tip grouting, side grouting, and CTS grouting on pile bearing performance were analyzed through static load tests. Subsequently, in situ tests were carried out to disclose reinforcement mechanisms associated with various grouting techniques, and ultimately, numerical simulation analyses were performed to explore how tip-grouting parameters affect bearing capacity. On the basis of the aforementioned analysis, the conclusions below were derived:

- (a)

The results of the field static load tests indicate that all grouting methods can significantly enhance the bearing capacity of bored piles in soft soil areas. Compared with side grouting, tip grouting achieves better improvement in pile bearing capacity by significantly enhancing the properties of the soil at the pile tip.

- (b)

Side grouting can improve performance and mobilization of pile side resistance, thereby enhancing the bearing capacity of bored piles. It is noteworthy that tip grouting can also increase side resistance near the pile tip through upward and downward seepage of the grout.

- (c)

Compared with single grouting methods, the combined tip-and-side grouting method, which modifies properties of the tip-bearing layer and simultaneously improves side resistance mobilization, provides the most significant enhancement of bearing performance for bored piles in soft soil areas.

- (d)

In situ test results demonstrate that side grouting enhances pile bearing performance via upward and downward seepage along the pile side, as well as splitting grouting in the surrounding soil. Tip grouting boosts bearing capacity by compacting and penetrating cement grout into the gravel layer at the pile tip, which forms a cement-gravel mixture to expand the pile tip.

- (e)

Results from the finite element model analysis indicate that, for tip-grouted piles, enhancing the material strength of the pile exerts an extremely limited effect on improving its bearing capacity. On the contrary, expanding the diffusion scope of the grout can remarkably boost the vertical bearing capacity of post-grouted piles.

Field tests on pile foundations are recognized as an effective approach to investigating the bearing performance of pile foundations. However, constrained by the substantial resources required for field tests, only three test piles were designed in this study, though this may limit the generalization of the research findings. It is worth noting that this study provides important implications for the design and construction of post-grouting pile foundation engineering, helping designers and constructors select grouting methods and parameters with better reinforcement effects based on project requirements and characteristics.