Analysis of Government-Led OSC Industrialization Index: Focusing on Singapore’s Buildability Score

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Research Objectives and Scope

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Background and Terminological Framework

2.1.1. Evolution: From Industrialized Construction to OSC

2.1.2. Regional Terminologies Under the OSC Umbrella

- Off-Site Manufacturing (OSM): Often used interchangeably with OSC in academic literature, emphasizing the manufacturing aspect of the process [17].

- Industrialised Building System (IBS): Predominantly used in Malaysia, emphasizing the systematic industrialization of the process through standardized components [11].

2.1.3. Justification for Focusing on OSC

2.2. Benefits and Challenges: The Justification for Policy Intervention

2.2.1. Potential Benefits of OSC

2.2.2. Market Barriers and the ‘Chicken and Egg’ Dilemma

2.2.3. The Necessity of Government-Led Policy

2.3. Theoretical Framework for Policy Evaluation

2.3.1. Policy Instruments Theory: Carrots, Sticks, and Sermons

- Regulations (Legal Mandate & Scope): These are mandatory rules that define the ‘scope’ of compliance and the legal ‘binding force’. In the context of OSC, this corresponds to whether the index is legally required for building permits.

- Economic Means (Incentives): These involve financial inducements or penalties to guide behavior. This aligns with the ‘Enforcement Mechanism’ of the index (e.g., GFA bonuses or levy exemptions).

- Information (Indicator Composition): This refers to the transfer of knowledge. A sophisticated ‘Indicator’ serves as a standard for information, guiding the industry on how to implement OSC effectively.

2.3.2. Policy Maturity and Effectiveness

- Maturity of Mandate: A mature policy shifts from ‘voluntary recommendations’ to ‘mandatory obligations’.

- Maturity of Specificity: A mature index moves from ‘simple quantitative volume checks’ to ‘qualitative evaluations of technological levels’ (e.g., distinguishing between simple PC and advanced DfMA).

3. Materials and Methods

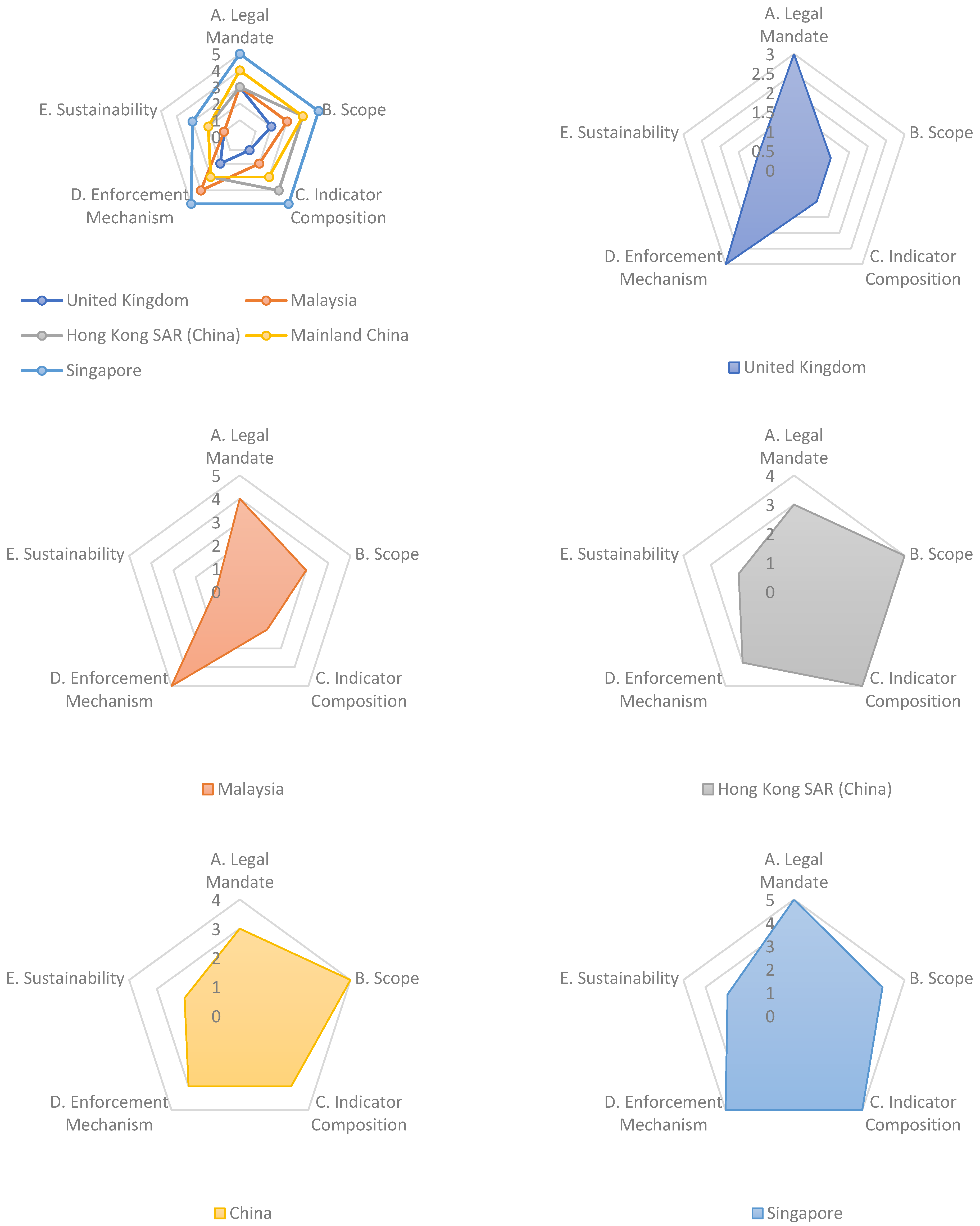

3.1. Analysis Framework: Policy Maturity Assessment

- A. Legal Mandate (Regulation/Stick): Measures the ‘enforceability’ of the policy.

- B. Scope (Regulation/Stick): Evaluates the ‘comprehensiveness’ of the evaluation target.

- C. Indicator Composition (Information/Sermon): Assesses the ‘qualitative level’ and technological specificity of the system.

- D. Enforcement Mechanism (Incentive/Carrot): Analyzes the means that secure its ‘effectiveness’ through penalties or incentives.

- E. Sustainability (Future-orientation): Evaluates the integration of environmental values.

3.2. Case Selection Criteria and Data Collection

3.2.1. Exclusion Criteria: Market-Driven Markets

- Reason for Exclusion: In these regions, high labor costs, harsh climatic conditions, and established supply chains naturally drive OSC adoption without the need for strong regulatory mandates or specific ‘Industrialization Indices’. As the primary mechanism for OSC adoption here is endogenous market demand rather than exogenous government policy, they are unsuitable for analyzing the effectiveness of “government-led industrialization indices,” which is the core objective of this study.

3.2.2. Inclusion Criteria: Policy-Driven Markets

- Reason for Selection: These are markets where the ecosystem is nascent or developing, and the government utilizes specific ‘Industrialization Indices’ as core policy instruments to mandate or incentivize productivity improvements.Selected Cases: Based on this criterion, five representative institutional frameworks across four nations were selected

- −

- United Kingdom: Utilizing Pre-Manufactured Value (PMV) to drive modernization in public infrastructure.

- −

- Malaysia: Implementing the IBS Score to systematically industrialize its developing construction sector.

- −

- Hong Kong SAR (China): Promoting MiC (Modular Integrated Construction) as a distinct regulatory jurisdiction to address high-density housing needs.

- −

- Mainland China: Enforcing the Assembly Rate to manage massive urbanization and environmental goals.

- −

- Singapore: Operating the Buildability Score to overcome severe reliance on foreign labor.

3.2.3. Data Collection

4. Comparative Analysis Results

4.1. Overview of National Industrialization Indices

4.1.1. United Kingdom: Pre-Manufactured Value (PMV)

4.1.2. Malaysia: Industrialised Building System (IBS) Score

- Part 1: Structural Systems (Max 50 points): Points awarded based on the area percentage of IBS structural elements (e.g., precast concrete, steel).

- Part 2: Wall Systems (Max 20 points): Points awarded based on the area percentage of IBS wall systems (e.g., precast walls, drywalls).

- Part 3: Other Simplified Solutions (Max 30 points): Points for standardized components like prefabricated staircases or roof trusses [11].

4.1.3. Hong Kong SAR (China): Modular Integrated Construction (MiC)

4.1.4. Mainland China: Prefabrication Assembly Rate

4.1.5. Singapore: Buildability Score (B-Score)

- Structural System: Points for labor-saving methods (e.g., steel, precast).

- Architectural System: Points for standardized components (e.g., drywalls, unitized windows).

- MEP System: Points for integrated modules like Prefabricated Bathroom Units (PBUs).

4.2. Comparative Assessment Results

Analysis by Policy Dimension

- UK (Level 3): PMV targets are recommended in The Construction Playbook as procurement guidance, but this does not constitute a legal mandate; it is limited to central government procurement and does not legally bind the private housing market [10].

- Malaysia (Level 3): The use of IBS is mandatory for government projects worth over RM 10 million, requiring a minimum IBS Score of 70, but private sector adoption remains largely voluntary or incentive-based [11].

- Singapore (Level 5): The index evaluates the entire building system, comprehensively covering Structural, Architectural, and MEP systems under a unified framework defined in the legislation [16].

- Mainland China (Level 4): The Assessment Standard (GB/T 51129) covers structure, enclosure, and fit-out, but the evaluation is often criticized for focusing on the physical volume of components rather than system integration [45].

- Malaysia (Level 3): The IBS Manual heavily skews points towards Structural (50 pts) and Wall systems (20 pts), with limited emphasis on complex MEP integration compared to Singapore [11].

- UK (Level 2): PMV measures the financial value (cost). As noted in the PMV Guidance, high-cost items can inflate the score regardless of the technical extent of prefabrication, limiting its technical comprehensiveness [10].

- Singapore (Level 5): The system has evolved from the original Labor Saving Index (LSI) coefficient to the current ‘Allocated Points’ system (2022 Edition), which structurally favors advanced technologies. For example, PPVC (Modular) receives significantly higher allocated points than simple precast components, promoting qualitative technological advancement [16].

- Mainland China (Level 3): It employs a hybrid approach but relies heavily on quantitative volume ratios (e.g., precast concrete volume > 50%), which does not necessarily distinguish between simple and advanced manufacturing techniques [45].

- UK (Level 1): It relies on a single quantitative metric based on financial cost (%). This can be influenced by market price fluctuations (e.g., rising material costs) rather than actual productivity gains [10].

- Singapore (Level 3): The Code of Practice links productivity scores with the Green Mark certification. High buildability scores can contribute to achieving higher environmental ratings, demonstrating partial policy integration [16].

- Environmental cost–benefit analyses of prefabricated public housing have demonstrated that productivity improvements can be achieved alongside environmental benefits [26].

4.3. Selection of In-Depth Case Study

5. Analysis of Singapore’s Buildability Appraisal System

5.1. Introduction and Evolution of the System for Productivity Innovation

5.2. Analysis of Buildable Design and Constructability Score Systems

5.2.1. Calculation Method for Buildable Design Score (B-Score)

- Structural System: For instance, in a residential project, applying ‘Structural Steel’ (allocated 35 points) to 80% of the total floor area would yield approximately 28 points [16].

- Architectural System: Points are awarded based on the usage of high-productivity methods like drywalls or curtain walls. For example, using dry construction methods for 90% of the total wall length can secure a high score of over 36 points [16].

- MEP System: Unlike previous versions, the MEP system is now a reinforced independent assessment category. Points are earned by adopting prefabricated vertical/horizontal modules or prefabricated pump skids [16].

- In addition to the basic systems, projects can secure up to 20 additional points under the ‘Innovation and Others’ category by adopting technologies that significantly enhance productivity. Bonus points are awarded for modular components like Prefabricated Kitchen Units (PKU) and Prefabricated Common Toilets (PCT), or for new technologies that achieve at least 20% manpower savings. Advanced DfMA technologies, such as PPVC, are critical for maximizing the total score, as they garner high points across Structural, Architectural, and MEP systems, as well as in the Innovation category [16].

- The final B-Score is the summation of the scores from these four categories (Structural + Architectural + MEP + Innovation), and the total score is capped at 120 points [16].

- Residential Projects: Due to the high volume of partition walls, finishes, and interior works, the Architectural System (AN) carries the highest weightage (up to 40 points). Conversely, MEP weighting (15–20 points) is relatively low due to the repetitive nature of standard units.

- Commercial Projects: Given the necessity for complex HVAC, fire protection, and IT infrastructure, the weightage for the MEP System (MN) is set at 35 points—more than double that of residential projects. This highlights the critical impact of MEP modularization on overall productivity in commercial buildings.

- Industrial Projects: Characterized by high ceilings, long spans, and heavy loading requirements, the Structural System (SN) is allocated 50 points, accounting for nearly half of the total score, thereby prioritizing productivity in structural works.

5.2.2. Calculation Method for Constructability Score (C-Score)

- Structural System: Points are awarded for using technologies and equipment that increase on-site productivity, such as system formwork, automated rebar fabrication, and high-strength concrete [16].

- Architectural, Mechanical, Electrical, and Plumbing (AMEP) Systems: Points are given for applying advanced technologies like prefabricated components, on-site automation equipment (e.g., painting robots), and non-destructive testing (NDT) [16].

- Good Industry Practices: Additional points are awarded for the level of smart construction technology adoption, including process management using BIM (Building Information Modeling), on-site surveying with drones and laser scanning, and the application of Integrated Digital Delivery (IDD) platforms [16].

5.3. Virtual Data Simulation

5.3.1. Simulation Overview and Allocated Points

- Project A (Public Housing, HDB): Accounts for a large proportion of Singapore’s housing supply and is characterized by high standardization. The baseline assumes the adoption of the highly productive Advanced Precast Concrete System (APCS), drywalls, and Prefabricated Bathroom Units (PBUs), which are strongly recommended by government policy.

- Project B (Office Building): Represents a private commercial building where diverse methods are mixed for design flexibility. The baseline assumes a Steel Frame and Curtain Wall for the main structure and envelope, but incorporates traditional wet-trade blockwork for internal partitions, reflecting common practices.

| Category | Project A: Public Housing (HDB) | Project B: Office Building |

|---|---|---|

| Category & Weight | Public Residential (S1: 45, A1: 40, M1: 15) | Commercial (S3, A3, M3) (S3: 35, A3: 30, M3: 35) |

| Scale | GFA 15,000 m2, 20 stories | GFA 20,000 m2, 15 stories |

| Baseline Methods (Assumed) | - Structure: APCS (80%), Cast-in situ (20%) - Arch: Precast/Drywall (75%), PBU Wall (25%) - MEP: Prefab Modules (Vertical/Horizontal, 50%) - PBU Adoption: 80% of total bathrooms - Feature: High standardization & PBU | - Structure: Steel Frame (80%), Cast-in situ (20%) - Arch: Curtain Wall (50%), Blockwall (50%) - MEP: Conventional (On-site, 100%) - Feature: Flexible design & Mixed wet trades |

5.3.2. Baseline Score Calculation

5.3.3. Sensitivity Analysis: Method Change Scenarios

- Scenario A-1 (Structure): Changing APCS (modern precast) to traditional Cast-in situ concrete to verify the impact of structural system selection.

- Scenario A-2 (Integrated): Replacing PBUs (prefabricated bathrooms) with conventional on-site wet bathrooms. This change not only reduces the direct coverage score but also disqualifies the project from PBU-related bonus points (Industry Standard PBU and PBU Repetition), demonstrating the compounding impact of DfMA technologies.

- Scenario B-1 (Architecture): Switching from Curtain Wall (dry) to Brickwall (wet) to measure the sensitivity of the score to the dry-process adoption in facade works.

5.4. Analysis of Design and Construction Behaviors Induced by the Buildability Score System

5.4.1. Behaviors Induced in the Design Stage (Impact on Design)

- Preference for Standardized and Modularized Designs: Achieving a high B-Score necessitates the use of standardized components that carry high allocated points (SN, AN, MN) [16]. This incentivizes designers to favor simple, grid-based layouts over complex, irregular forms. Furthermore, adopting ‘Industry Standard Dimensions’ for components such as windows, doors, and PBUs grants additional bonus points, compelling designers to prioritize standardized specifications over bespoke designs [16].

- Emphasis on ‘Dry’ Construction Methods: In the architectural system evaluation, traditional on-site ‘wet’ trades like brickwork and plastering are assigned zero or very low allocated points [45]. As confirmed by the simulation results (Scenario B-1), adopting wet methods results in a failure to secure points. Consequently, designers naturally gravitate towards ‘dry’ construction methods with high allocated points, such as drywall partitions and prefabricated panels, which are manufactured off-site and installed quickly on-site.

- Proactive Integration of DfMA Technologies: The ‘Innovation’ category of the B-Score strongly motivates the integration of high-value DfMA technologies, such as Prefabricated Bathroom Units (PBUs), modular MEP systems, and PPVC, into the design from the early stages. The significant score difference of over 13 points observed in the simulation (Scenario A-2) depending on PBU adoption—comprising both the direct coverage score (7.0 points) and the associated bonus points for industry standardization and repetition (6.5 points)—highlights that these technologies function almost as mandatory requirements rather than mere options [16].

5.4.2. Behaviors Induced in the Construction Stage (Impact on Construction)

- Maximization of Off-site Production: The precast concrete, steel components, and various prefabricated modules adopted during the design phase to achieve a high B-Score inevitably increase the proportion of work carried out in factories by the builder. This serves as a key driver for shifting the construction process from traditional on-site work towards a model centered on ‘off-site manufacturing + site assembly’.

- Simplification of On-site Work and Adoption of Smart Technologies: When precisely manufactured components arrive on-site, the role of the construction site shifts away from complex processing and fabrication towards simpler tasks focused on erection and assembly. Concurrently, the C-Score encourages builders to actively invest in smart construction technologies such as System Formwork, BIM-based process management, Integrated Digital Delivery (IDD), and other Good Industry Practices, thereby enhancing both on-site productivity and safety [16].

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Summary of Key Findings

6.2. Effectiveness of Government-Led Policy Intervention

6.3. Design Principles for Effective OSC Industrialization Indices

- Dual Enforcement Mechanism: Combining ‘sticks’ (mandatory baseline for permit approval) and ‘carrots’ (incentives like GLS requirements) is essential to ensure universal compliance while driving innovation.

- Technology-Weighted Scoring (Value over Volume): This is critical for promoting qualitative advancement. Unlike simple volume-based metrics (e.g., prefabrication percentage) that treat all precast components equally, Singapore’s allocated points system assigns significantly higher weights to advanced DfMA technologies (e.g., PPVC, PBU). This structural preference ensures the metric measures “Labor Saving Value” rather than just physical volume.

- Differentiated Weightings by Building Type: Allocating different maximum points to Structural, Architectural, and MEP systems based on the specific manpower consumption patterns of each building type allows for targeted management of critical labor-intensive trades.

- Integration with Industry Standardization: Bonus points for industry standard dimensions and components promote supply chain efficiency and reduce customization costs, creating a virtuous cycle for manufacturers and developers.

6.4. Limitations and Future Research

6.5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barbosa, F.; Woetzel, J.; Mischke, J. Reinventing Construction: A Route to Higher Productivity; McKinsey Global Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. Shaping the Future of Construction: A Breakthrough in Mindset and Technology; WEF: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Wang, C.C.; Sepasgozar, S.; Zlatanova, S. A Systematic Review of Digital Technology Adoption in Off-Site Construction: Current Status and Future Direction towards Industry 4.0. Buildings 2020, 10, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M.; Eltoukhy, A.E.E.; Karam, A.; Shaban, I.A.; Zayed, T. Modelling in Off-Site Construction Supply Chain Management: A Review and Future Directions for Sustainable Modular Integrated Construction. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 310, 127503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuni, I.Y.; Shen, G.Q. Holistic Review and Conceptual Framework for the Drivers of Offsite Construction: A Total Interpretive Structural Modelling Approach. Buildings 2019, 9, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuni, I.Y.; Shen, G.Q. Barriers to the Adoption of Modular Integrated Construction: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, Integrated Conceptual Framework, and Strategies. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 249, 119347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Gibb, A.G.F.; Dainty, A.R.J. Perspectives of UK Housebuilders on the Use of Offsite Modern Methods of Construction. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2007, 25, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.H.N.; Moon, H.; Ahn, Y. Critical Review of Trends in Modular Integrated Construction Research with a Focus on Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali, M.; Hewage, K. Life Cycle Performance of Modular Buildings: A Critical Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 62, 1171–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HM Government. The Construction Playbook: Government Guidance on Sourcing and Contracting Public Works Projects and Programmes; Cabinet Office: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Construction Industry Development Board (CIDB). IBS SCORE Manual; CIDB Malaysia: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Zayed, T.; Niu, Y. Comparative Analysis of Modular Construction Practices in Mainland China, Hong Kong and Singapore. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bemelmans-Videc, M.L.; Rist, R.C.; Vedung, E. Carrots, Sticks & Sermons: Policy Instruments and Their Evaluation; Transaction Publishers: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Policy Framework for Investment; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Park, M.; Ingawale-Verma, Y.; Kim, W.; Ham, Y. Construction Policymaking: With an Example of Singaporean Government’s Policy to Diffuse Prefabrication to Private Sector. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2011, 15, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Building and Construction Authority (BCA). Code of Practice on Buildability: 2022 Edition; BCA: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Goodier, C.; Gibb, A. Future Opportunities for Offsite in the UK. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2007, 25, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Building Sciences (NIBS). Off-Site Construction Council Report; NIBS: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, C.; Oyekan, J.; Stergioulas, L.K. Distributed Manufacturing: A New Digital Framework for Sustainable Modular Construction. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatunji, K.K.; Olawumi, T.O.; Odeyinka, H.A. Integration of Building Services in Modular Construction: A PRISMA Approach. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, M. The Farmer Review of the UK Construction Labour Model: Modernise or Die; Construction Leadership Council: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, W.; Hon, C.K. Briefing: Modular Integrated Construction for High-Rise Buildings. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Munic. Eng. 2020, 173, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Development Bureau (DEVB). Construction 2.0: Time to Change; DEVB, The Government of the HKSAR: Hong Kong, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W.; Tan, T.; Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, K.; Gao, S.; Xue, F. Design for Manufacture and Assembly (DfMA) in Construction: The Old and the New. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2021, 17, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhao, D.; Wang, D.; Xing, Y. Sustainable Performance of Buildings through Modular Prefabrication in the Construction Phase: A Comparative Study. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yu, Y. Environmental Cost-Benefit Analysis of Prefabricated Public Housing in Beijing. Sustainability 2019, 11, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, X.; Chang, R.; Zuo, J.; Wen, T.; Zillante, G. Barriers to the Transition Towards Off-Site Construction in China: An Interpretive Structural Modeling Approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blismas, N.; Wakefield, R. Drivers, Constraints and the Future of Offsite Manufacture in Australia. Constr. Innov. 2009, 9, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agapiou, A. Barriers to Offsite Construction Adoption: A Quantitative Study among Housing Associations in England. Buildings 2022, 12, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, P.F.V.; Sánchez-Garrido, A.J.; Godinho-Ferreira, I.; Yepes, V. Barriers to the Adoption of Modular Construction in Portugal: An Interpretive Structural Modeling Approach. Buildings 2022, 12, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinelli, M.; Konanahalli, A.; Dwarapudi, R.K. Assessment of Barriers and Strategies for the Enhancement of Off-Site Construction in India: An ISM Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, C.; Shen, Q.; Pan, W.; Ye, K. Major Barriers to Off-Site Construction: The Developer’s Perspective in China. J. Manag. Eng. 2015, 31, 04014043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Shen, G.Q.; Li, Z.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, W. Barriers to Promoting Prefabricated Construction in China: A Cost–Benefit Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhardt, D.A.; Manley, K. Adoption of Prefabricated Housing: The Role of Country Context. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2016, 22, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Le, Y.; Li, H.; Jin, R.; Piroozfar, P.; Liu, M. A Study on the Incentive Policy of China’s Prefabricated Residential Buildings Based on Evolutionary Game Theory. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, H.; Kim, H.-G.; Kim, J.-S. Integrated Off-Site Construction Design Process including DfMA Considerations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Sun, C.; Wang, Y. Design for Manufacture and Assembly-Oriented Parametric Design of Prefabricated Buildings. Autom. Constr. 2018, 88, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infrastructure and Projects Authority (IPA). Transforming Infrastructure Performance: Roadmap to 2030; IPA: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ofori-Kuragu, J.K.; Osei-Kyei, R.; Wanigarathna, N. Offsite Construction Methods—What We Learned from the UK Housing Sector. Infrastructures 2022, 7, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamar, K.A.M.; Azman, M.N.A.; Nawi, M.N.M. IBS Survey 2010: Drivers, Barriers and Critical Success Factors in Adopting Industrialised Building System (IBS) Construction by G7 Contractors in Malaysia. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2014, 9, 490–501. [Google Scholar]

- Loo, B.P.Y.; Wong, R.W.M. Towards a Conceptual Framework of Using Technology to Support Smart Construction: The Case of Modular Integrated Construction (MiC). Buildings 2023, 13, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Yu, R.; Liu, T.; Guan, H.; Oh, E. Drivers towards Adopting Modular Integrated Construction for Affordable Sustainable Housing: A Total Interpretive Structural Modelling (TISM) Method. Buildings 2022, 12, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, M.; Ping, T. Evaluating Modular Healthcare Facilities for COVID-19 Emergency Response—A Case of Hong Kong. Buildings 2022, 12, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Z.; Hong, J.; Xue, F.; Shen, G.Q.; Xu, X.; Mok, M.K. Schedule Risks in Prefabrication Housing Production in Hong Kong: A Social Network Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 134, 482–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the PRC. Standard for Assessment of Assembled Buildings (GB/T 51129-2017); China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, J.; Han, Y. Comparative Analysis and Empirical Study of Prefabrication Rate Calculation Methods for Prefabricated Buildings in Various Provinces and Cities in China. Buildings 2023, 13, 2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Yang, X.; Chen, Y.; Liao, Y.; Li, H. Analysis of Provincial Policies on the Development of Prefabricated Construction in China. Infrastructures 2023, 8, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Luo, L.; Wu, Z.; Fei, J.; Antwi-Afari, M.F.; Yu, T. An Investigation of the Effectiveness of Prefabrication Incentive Policies in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Wu, G. The Efficiency of the Chinese Prefabricated Building Industry and Its Influencing Factors: An Empirical Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Gong, Z.; Li, N.; Liu, C. Policy Framework for Prefabricated Buildings in Underdeveloped Areas: Enlightenment from the Comparative Analysis of Three Types of Regions in China. Buildings 2023, 13, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corporación de Desarrollo Tecnológico (CDT). OptimizIA: Sistema de Evaluación de Proyectos; Chilean Chamber of Construction (CChC): Santiago, Chile, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, C.; Xie, F.; Hou, L.; Wu, P.; Wang, J.; Wang, X. Cost Analysis for Sustainable Off-Site Construction Based on a Multiple-Case Study in China. Habitat Int. 2016, 57, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pheng, L.S.; Abeyegoonasekera, B. Integrating Buildability in ISO 9000 Quality Management Systems: Case Study of a Condominium Project. Build. Environ. 2001, 36, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, R.M.; Ogden, R.G.; Bergin, R. Application of Modular Construction in High-Rise Buildings. J. Archit. Eng. 2012, 18, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.O.; Chen, X.B.; Kim, T.W. Opportunities and Challenges of Modular Methods in Dense Urban Environment. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2019, 19, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criteria | Level 1 (Low/Voluntary) | Level 3 (Moderate/Mixed) | Level 5 (High/Mandatory) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Legal Mandate | Voluntary guideline or recommendation only. | Mandatory for specific public projects. | Strictly mandatory for both public & private sectors; linked to building permits. |

| B. Scope | Evaluates a single aspect (e.g., structure only). | Covers structure and partial architectural finishes. | Comprehensive evaluation (Structure + Architecture + MEP) covering the entire building system. |

| C. Indicator Composition | Simple quantitative metric (e.g., % of components). | Hybrid of quantitative and qualitative measures. | Advanced metric with weighted scores for technological complexity (e.g., DfMA) and innovation. |

| D. Enforcement Mechanism | No specific enforcement or simple promotion. | Incentive-based (Bonus GFA, subsidies) or Penalty-based only. | Dual mechanism combining strong penalties (permit denial) with financial incentives. |

| E. Sustainability | No consideration of environmental values. | Indirect environmental benefits mentioned. | Integrated evaluation where productivity scores are linked to environmental ratings (e.g., Green Mark). |

| Region (Index Name) | A. Legal Mandate | B. Scope | C. Indicator Composition | D. Enforcement Mechanism | E. Sustainability | Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singapore (Buildability Score) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 23 |

| Main land China (Assembly Rate) | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 16 |

| Hong Kong SAR (MiC Acceptance) | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 16 |

| Malaysia (IBS Score) | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 13 |

| UK (PMV) | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 9 |

| System | Specific Method | Allocated Points (HDB) | Allocated Points (Office) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural (SN) | - APCS (Advanced Precast Concrete) | 39 (S1) | N/A |

| - Structural Steel | N/A | 33 (S3) | |

| - Cast-in situ Concrete | 10 (S1) | 15 (S3) | |

| Architectural (AN) | - Precast/Drywall | 26 (A1) | N/A |

| - Curtain Wall | N/A | 16 (A3) | |

| - PBU (Prefabricated Bathroom) | 28 (A1) | N/A | |

| - Brick/Blockwall (Wet) | 0 (A1) | 0 (A3) | |

| MEP (MN) | - Prefab Modules | 12 (M1) | 20 (M3) |

| - Conventional (On-site) | 0 | 0 |

| Evaluation Component | Specific Method | Application Ratio | Allocated Points | Calculation | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural (max 45) | APCS | 80% | 39 | 0.8 × 39 | 31.2 |

| Cast-in situ | 20% | 10 | 0.2 × 10 | 2.0 | |

| Architectural (max 40) | Precast/ Drywall | 75% | 26 | 0.75 × 26 | 19.5 |

| PBU (Bathroom) | 25% | 28 | 0.25 × 28 | 7.0 | |

| MEP System (max 15) | Prefab Modules | 50% | 12 | 0.5 × 12 | 6.0 |

| Others | Innovation/ Bonus | - | - | (Assumed) | +15.0 |

| Total Score | 80.7 |

| Evaluation Component | Specific Method | Application Ratio | Allocated Points | Calculation | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural (max 35) | Steel Frame | 80% | 33 | 0.8 × 33 | 26.4 |

| Cast-in situ | 20% | 15 | 0.2 × 15 | 3.0 | |

| Architectural (max 30) | Curtain Wall | 50% | 16 | 0.5 × 16 | 8 |

| Blockwall (Wet) | 50% | 0 | 0.5 × 0 | 0.0 | |

| MEP System (max 35) | Conventional | 100% | 0 | 1.0 × 0 | 0.0 |

| Others | Innovation/ Bonus | - | - | (Assumed) | +5.0 |

| Total Score | 42.4 |

| Category | Project A (HDB) | Project B (Office) |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Score | 33.2 (max 45) | 29.4 (max 35) |

| Architectural Score MEP Score | 26.5 (max 40) 6.0 (max 15) | 8.0 (max 30) 0.0 (max 35) |

| Other Bonus | 15.0 (incl. PBU bonus 6.5) | 5.0 |

| Total Estimated Score | 80.7 | 42.4 |

| Scenario | Change Description (High Pts→Low Pts) | Resulting Component Score | Change in Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| A-1: HDB Structure | APCS (39 pts)→Cast-in situ (10 pts) | Structure: 33.2→10.0 | ▼ 23.2 pts |

| A-2: HDB PBU | PBU (28 pts)→(loses 80% PBU adoption) | Arch: 26.5→19.5, Bonus:15.0→8.5 | ▼ 13.5 pts |

| B-1: Office Facade | Curtain Wall (16 pts)→Brick (0 pts) | Arch: 8.0→0.0 | ▼ 8.0 pts |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Seol, W.; Baek, C.; Hwang, J.-e. Analysis of Government-Led OSC Industrialization Index: Focusing on Singapore’s Buildability Score. Buildings 2026, 16, 574. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030574

Seol W, Baek C, Hwang J-e. Analysis of Government-Led OSC Industrialization Index: Focusing on Singapore’s Buildability Score. Buildings. 2026; 16(3):574. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030574

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeol, Wookje, Cheonghoon Baek, and Jie-eun Hwang. 2026. "Analysis of Government-Led OSC Industrialization Index: Focusing on Singapore’s Buildability Score" Buildings 16, no. 3: 574. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030574

APA StyleSeol, W., Baek, C., & Hwang, J.-e. (2026). Analysis of Government-Led OSC Industrialization Index: Focusing on Singapore’s Buildability Score. Buildings, 16(3), 574. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030574