1. Introduction

Industrialised construction (IC) is an approach aimed at improving productivity, predictability, and overall performance by applying standardised, repeatable, and modular manufacturing and assembly processes to building and infrastructure delivery, primarily through modern methods of construction (MMC). IC represents a shift away from traditional labour-intensive practices toward a manufacturing-oriented model for housing production. Construction contributes to roughly 13% of global GDP (9% in Australia) yet remains criticised for inefficiency, safety risks, and environmental impact [

1]. Off-site manufacture promises faster, safer, and cleaner delivery, although it is not universally cheaper. Standardisation through platform-based rules can improve customisation and productivity when coherently designed [

2]. Platform-based DfMA reframes productivity as repeatable rule-driven design enabling variety, predictable logistics, and rapid assembly [

3].

Housing has become central to this transformation as governments address converging crises of affordability, productivity, and carbon reduction. Growing urbanisation and population have intensified housing demand beyond traditional capacity, especially across OECD and Asia–Pacific regions. The resulting supply–demand imbalance drives affordability decline and social inequality, while construction remains one of the least digitised sectors, marked by cost overruns and poor resource efficiency. IC offers scalable, low-waste, digitally integrated delivery models that are capable of reducing embodied carbon [

4].

Despite these advantages, adoption remains inconsistent. Singapore, Japan, and Sweden exhibit mature modular ecosystems supported by coordinated policy and manufacturing pipelines, whereas Australia, the UK, and the US experience fragmented uptake due to high upfront costs, uncertain demand, regulatory ambiguity, and limited design flexibility. A lack of interoperable digital ecosystems linking design, production, and business operations further constrains efficiency at scale.

Advances in Building Information Modelling (BIM), Design for Manufacture and Assembly (DfMA), and platform-based approaches have reignited global interest in modular construction. These innovations promise operational efficiency and a new industrial logic that integrates digital design with mass customisable production. Realising this potential requires coherent frameworks aligning policy, finance, regulation, and digital systems [

4].

UK Research and Innovation [

5] identifies a productivity lag of up to 40% lower output per hour than manufacturing as a key barrier to national growth, proposing product platforms as a structural reform to achieve economies of repetition, waste reduction, and sustainable productivity gains.

This study systematically reviews the evolution and current state of IC for housing, focusing on the intersection of technology and systemic barriers. It (1) synthesises the global adoption trends and performance evidence from 2002 to 2025, (2) examines structural, financial, regulatory, and cultural impediments to scalability, and (3) evaluates emerging enablers, such as P-DfMA, lifecycle digital integration, and policy–finance innovations. The review aims to identify the conditions under which IC can transition from isolated pilot projects to a resilient mainstream model that is capable of delivering affordable, sustainable, and productive housing. Accordingly, this study is positioned as a systematic literature review with thematic synthesis, aiming to consolidate and structure evidence rather than provide a philosophical critique of research paradigms.

2. Research Methodology

This systematic literature review employs a systematic and transparent research approach to map the global state of industrialised construction for housing. The aim was to identify, analyse, and synthesise peer-reviewed and grey-literature sources that collectively illustrate adoption patterns, performance outcomes, and digital-platform innovations across the modular and off-site construction domain.

2.1. Databases and Search Strategy

The primary databases consulted were Google Scholar, Scopus, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect, complemented by industry and policy repositories, including the UK Construction Innovation Hub, Australian ABCB reports, and Singapore’s Building and Construction Authority. This multi-source approach ensured coverage of both academic and professional discourse, bridging the gap between theoretical models and applied industrial practice. Google Scholar and targeted industry/policy repositories were included to partially mitigate indexing bias and capture practice-oriented and regionally disseminated evidence that may be underrepresented in Scopus and Web of Science. All databases and repositories were last searched on 1 December 2025.

2.2. Search Terms and Keywords

Combinations of controlled and free-text terms were used, reflecting both historical and emerging terminology. The final query string included “modular construction”, “off-site manufacturing”, “prefabrication”, “industrialised construction”, “modern methods of construction (MMC)”, “platform-based design”, “design for manufacture and assembly (DfMA)”, “BIM integration”, “product platforms”, “mass production”, “mass customisation”, and “lean manufacturing”. Boolean operators were applied to capture cross-disciplinary studies linking these topics to the housing sector.

2.3. Timeframe

The review covers studies published between 2000 and 2025, capturing the period when digital transformation, BIM standardisation, and DfMA adoption became dominant in both research and industry practice. Earlier studies were included selectively when they were foundational to current theory or practice.

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were retained if they (a) focused primarily on residential or housing applications of industrialised construction, (b) were published in English, and (c) were peer-reviewed journal articles, conference papers, or authoritative industry or government reports. Excluded materials included purely commercial case studies, non-English reports without translation, and non-housing infrastructure research. The English-language restriction was applied to ensure consistent screening and reproducibility within available resources; however, it may underrepresent region-specific evidence from countries where industrialised construction is advanced but commonly disseminated in local-language outlets. Industry and policy documents were included only where the issuing organisation had recognised sector authority and where the document provided a traceable scope and evidence basis. Documents that were primarily promotional, vendor-specific marketing, or single-project commercial showcases without methodological disclosure were excluded. Where multiple versions existed, the most recent and complete edition was retained. In synthesis, peer-reviewed studies were prioritised for comparative or causal performance claims, while industry/policy sources were used primarily to contextualise adoption pathways, regulatory settings, and implementation mechanisms.

2.5. Data Screening and Analysis

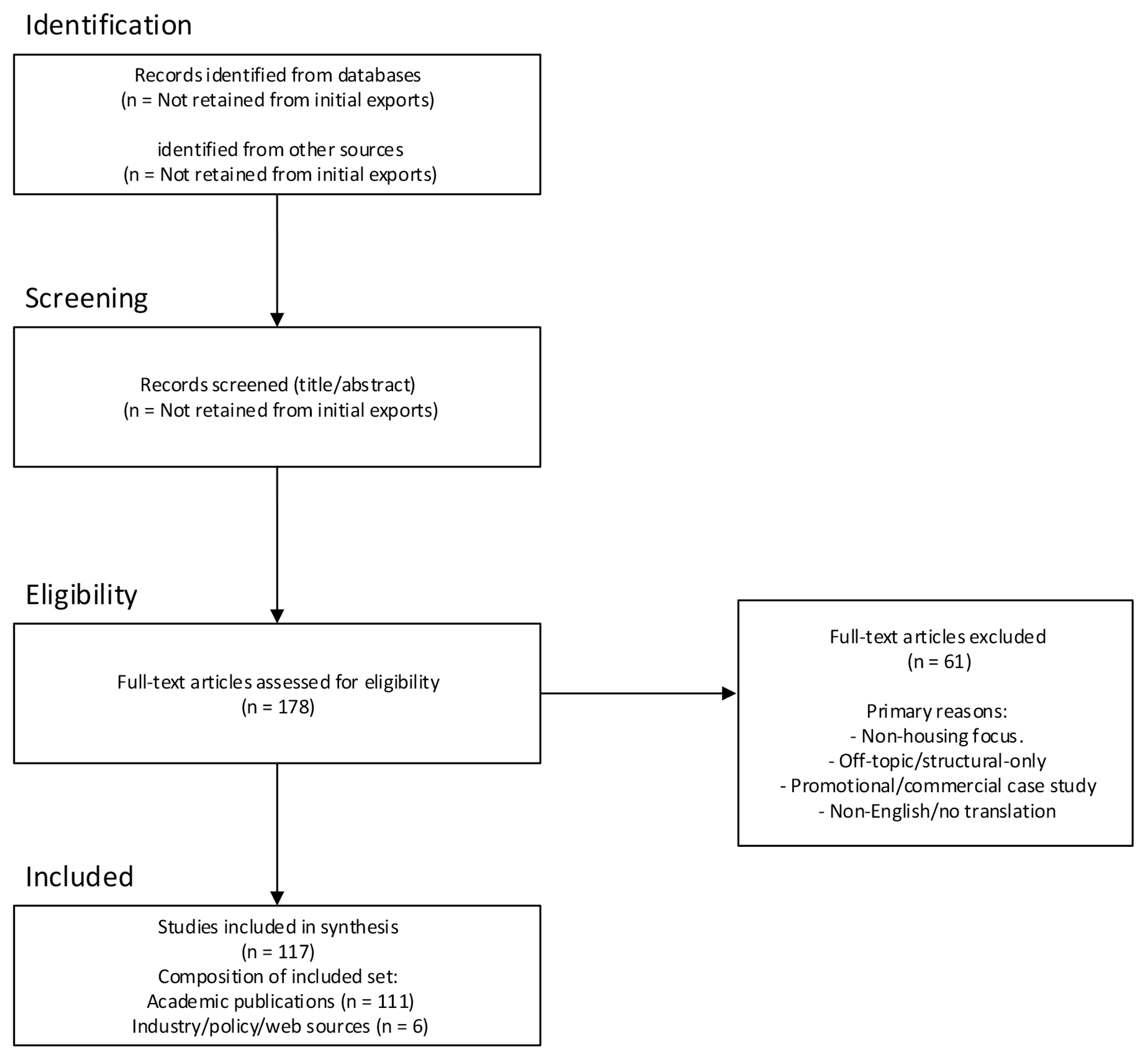

An initial pool of studies was identified across the selected databases and repositories. After duplicate removal and title–abstract screening, 178 papers remained for full-text review. The final dataset comprised 117 sources. To structure synthesis, the included sources were classified into five analytical categories aligned with the review focus: (1) adoption and market trends, (2) comparative performance metrics, (3) barriers and enablers, (4) digital platform integration, and (5) sustainability and policy frameworks. Category definitions were refined during full-text review to minimise overlap and ensure each category captured a distinct aspect of the evidence base. Where studies spanned multiple areas, they were assigned to the best-fit primary category and cross-referenced in other relevant categories during synthesis. Findings were then synthesised narratively within and across categories, highlighting convergence and divergence across geographic contexts and methodological approaches. These categories were chosen to mirror the main analytic dimensions of the review (uptake, performance evidence, implementation determinants, digital integration, and policy/sustainability context) and to provide complete non-redundant coverage of the included literature. A PRISMA-style flow diagram (

Figure 1) summarises the identification, screening, eligibility assessment, inclusion counts, and primary exclusion reasons.

Titles and full-text eligibility were screened by four reviewers. Screening was conducted independently, and disagreements were resolved through discussion. No automation tools were used. Data were extracted from the included sources. Extraction was completed by all four reviewers and cross-checked by them.

Extracted outcome domains included the following: adoption/uptake patterns, reported performance outcomes (time, cost, predictability, quality, safety, waste, and carbon), barriers and enablers, digital integration maturity, and policy mechanisms. Additional variables extracted (where reported) included publication year, country/region, housing context/typology, IC approach (e.g., 2D/3D/hybrid where stated), and evidence type (peer-reviewed study vs. industry/policy report).

Given the heterogeneity of study designs and the inclusion of policy/industry sources, a formal risk-of-bias tool was not applied; however, peer-reviewed studies were prioritised for comparative performance claims, and non-peer-reviewed sources were used primarily for contextual evidence. No quantitative effect measures were calculated because the review used narrative/thematic synthesis rather than meta-analysis. A narrative/thematic synthesis approach was adopted due to heterogeneity in study types, contexts, and reported metrics; meta-analysis was not performed. Because no quantitative synthesis was performed, heterogeneity exploration, sensitivity analyses, and reporting-bias assessment were not undertaken. Certainty of evidence was not formally graded because the review synthesised diverse qualitative, quantitative, and policy sources.

Where quantitative results were inconsistently reported, findings were synthesised as reported ranges and qualitative trends without converting units.

A PRISMA-style flow diagram (

Figure 1) is provided to summarise identification, screening, eligibility assessment, inclusion counts, and primary exclusion reasons. Counts for the identification and title–abstract screening stages were not retained from the initial search exports; therefore,

Figure 1 reports confirmed eligibility and inclusion-stage counts. This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines, and the checklist is provided as

Supplementary Materials.

3. Adoption and Market Trends

The global off-site construction market was valued at USD 155.3 billion in 2023 and is projected to grow at a compound annual rate of 5.7% from 2024 to 2032 [

6]. However, IC for housing shows uneven adoption shaped by local regulation, industrial capacity, and cultural attitudes toward prefabrication. While modular methods have expanded in the commercial and institutional sectors, residential adoption has been slower due to fragmented demand, limited design flexibility, and regulatory complexity.

The transition to industrialised housing relies on effective integration of automation, AI, and BIM-driven workflows, yet high investment costs and variable digital literacy among professionals persist. The research output on IC grew from approximately seven publications per year (2004–2018) to approximately fourteen per year (2019–2023), peaking at thirty-eight in 2023; China accounts for 24% of the studies, followed by the UK, US, Australia, and Germany [

7].

3.1. North America and Canada

In North America, industrialised housing has experienced rapid growth driven by critical housing shortages and rising construction costs. In the United States, the private-sector participation in modular multifamily projects has increased noticeably, with 68% of IC firms targeting housing and 52% utilising volumetric modular systems. This growth is propelled by increasing venture capital investment and the rise of design–manufacture startups such as Factory_OS and Vantem, which together account for approximately 44% of companies in the industrial construction sector [

8]. Despite this development, scaling remains difficult due to inconsistent approval pathways and supply chain variability [

9]. Industry practitioners further highlight high capital costs, a lack of software interoperability, and cultural resistance as critical barriers to adopting advanced technologies that are essential for IC at scale [

10]. In contrast, Canada’s modular housing sector has expanded more consistently due to stronger governmental involvement, particularly through social housing and rapid-deployment initiatives that leverage volumetric modular systems for urban infill and emergency accommodation. Federal programmes such as the Rapid Housing Initiative and Build Canada Homes prioritise IC, aggregating demand and streamlining procurement to enable scalable factory-controlled delivery across urban, suburban, and remote contexts [

11]. Collaborative approaches involving federal, provincial, and municipal governments, together with Indigenous communities, have further enabled rapid implementation through design–build models and reference residential solutions tailored to specific project needs [

12].

3.2. United Kingdom and Europe

The United Kingdom presents one of the most studied yet unstable ecosystems for MMC. Policy frameworks such as the Construction 2025 Strategy and MMC Definition Framework have generated substantial momentum, and major contractors have invested in dedicated off-site manufacturing facilities. Nevertheless, several MMC manufacturers have stopped production or gone bankrupt since 2022, raising concerns about how MMC housing projects are governed [

13]. While MMC can improve speed, efficiency, and quality in UK housing delivery, the approach’s potential to address supply shortages is constrained by systemic barriers, including traditional business models, fragmented supply chains, unclear regulation, high upfront costs, and limited skills, meaning MMC must be integrated into broader housing-system reforms to be truly effective [

14]. Across continental Europe, countries such as Germany and France (9–10% of total housing), the Netherlands (50%), and parts of Scandinavia have well-established MMC sectors, with Sweden at the forefront of MMC innovation [

15]. Ireland integrates MMC into its “Housing for All” plan with funding, standardised designs, and skills development. Spain’s MMC sector is underdeveloped but growing via government plans and clusters such as iCONS, although gaps regarding the supply chain and skills remain. Sweden leads globally, with 90% of small homes prefabricated and strong institutional support, sustainability, and timber use, exemplified by BoKlok [

16]. Europe’s success is attributed to decades of housing standardisation, vertically integrated supply chains, and strong collaboration between housing providers and manufacturers, demonstrating that policy continuity and cultural acceptance are decisive enablers of resilience.

3.3. Asia–Pacific Region

Asia’s modular evolution reflects a more government-led trajectory. Singapore’s Prefabricated Prefinished Volumetric Construction (PPVC) mandate and its digital rule-checking platform have positioned it as a global benchmark for integrated policy and technology adoption. Since 2014, the inclusion of PPVC requirements in selected land sale conditions has encouraged broader industry participation. As a result, an increasing number of residential, commercial, and industrial buildings in Singapore are now being developed using PPVC methods. Japan and China have likewise embedded industrialisation into national housing strategies: Japan through its Sekisui House model of precision modular production and China through state-backed industrial parks that promote prefabricated concrete and hybrid modular systems.

The Hong Kong SAR Government has committed to advancing Modular Integrated Construction (MiC) as part of its broader innovation agenda. Through significant investment via the Construction Innovation and Technology Fund (CITF), the government aims to accelerate technological adoption and support pilot projects such as modular elderly homes. In China, the use of modular building technologies has progressively expanded to include multi-storey and high-rise developments. Since 2007, both enterprises and academic institutions have actively collaborated to adapt modular construction systems to meet national regulatory requirements [

17]. Project-level plan analysis in Hong Kong suggests developments: standardised spaces and modules were reused across multiple residential projects, indicating an industrialised supply chain capable of repeating solutions at scale [

18].

Overall, Singapore exhibits the most advanced and well-structured implementation of modular construction in the region, while China continues to proceed steadily through supportive policies, industry initiatives, and research collaboration.

Australia, by contrast, remains in an emergent stage, with growing policy recognition but limited manufacturing depth. State-led initiatives such as Victoria’s Off-Site Construction Framework and New South Wales’ Modern Methods of Construction Roadmap (2023) signal a policy shift toward mainstreaming IC, although industry fragmentation and inconsistent demand continue to slow progress. Survey data in Australia’s low-rise sector show that most respondents are willing or strongly willing to adopt OSC, with a majority expecting a small to significant uptake within 1–3 years. Consultancies and builders report stronger enthusiasm than architectural firms [

6].

3.4. Emerging Markets and Developing-Economy Contexts

Evidence from emerging markets indicates that the same ecosystem conditions observed in mature IC regions—policy coordination, stable production pipelines, and supporting infrastructure—remain decisive but are often harder to secure due to higher capital costs, weaker supply chain depth, and more volatile demand. In China, national policy has set targets that accelerate prefabrication uptake in new construction, indicating an explicitly state-driven pathway to scale [

19]. In Malaysia, national IBS monitoring shows adoption in both government and private projects but still at moderate penetration levels, highlighting the gap between policy ambition and market-wide diffusion [

20]. India’s Global Housing Technology Challenge illustrates an alternative emerging-market approach focused on piloting and mainstreaming a portfolio of construction technologies through lighthouse demonstration projects [

21]. Consistent with these patterns, developing-economy risk studies show that inadequate modular expertise, limited manufacturer capacity, restricted late-stage design flexibility, and transport constraints can amplify schedule and quality risks when IC is introduced into underdeveloped delivery ecosystems [

22].

3.5. Comparative Insights

Cross-regional evidence shows that IC succeeds when policy, finance, supply chain integration, and digital infrastructure align. Markets that are dependent on speculative or project-based procurement struggle to sustain factory utilisation. Conversely, countries embedding IC in housing and sustainability strategies—Singapore, Sweden, and Japan—demonstrate stronger resilience and investor confidence (

Table 1). Adoption is still limited by inconsistent regulation, digital-skills shortages, and cultural resistance to prefabrication. National standards and shared data protocols could close these gaps and accelerate approvals [

4].

3.6. Key Takeaway

The global adoption patterns show that IC thrives through coordinated ecosystems, not isolated technologies. Policies that stabilise demand, reduce investment risk, and foster vertically integrated data-connected pipelines are crucial. Even leading markets continue to face business model fragility, workforce inertia, and policy inconsistency—challenges explored in the next section, Comparative Performance and Critical Challenges.

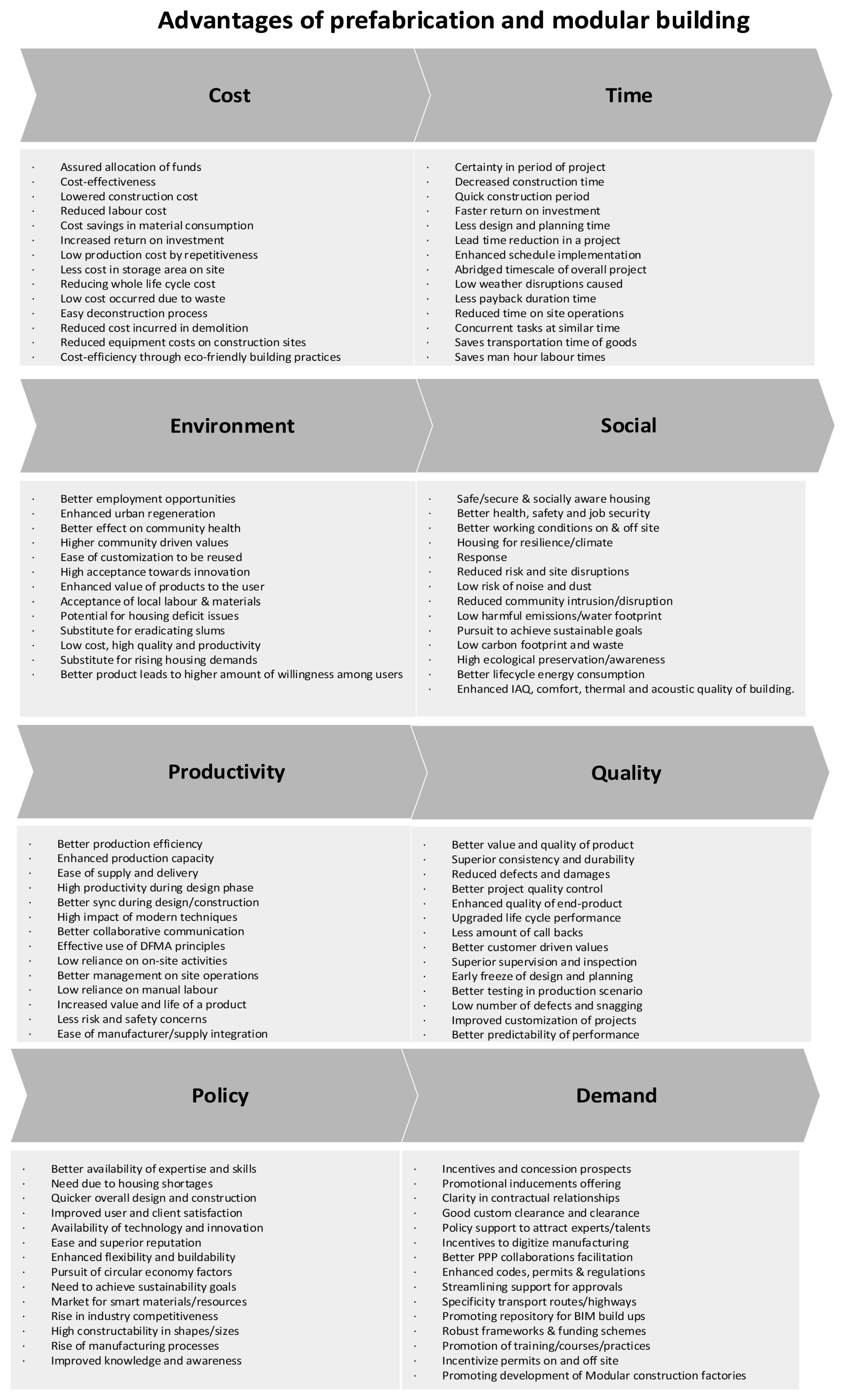

4. Comparative Performance: Industrialised vs. Traditional

Comparative studies consistently demonstrate that IC outperforms traditional on-site delivery in project-level metrics—time, cost predictability, quality, safety, and environmental performance (

Figure 2). However, translating these efficiencies into long-term business resilience remains a challenge.

To strengthen comparability across the evidence base,

Table 2 summarises the most frequently reported performance indicators for IC relative to traditional delivery. The reported values vary by building type, production maturity, logistics distance, and procurement continuity; therefore, ranges are presented where studies provide quantification, and qualitative indicators are noted where reporting is inconsistent.

4.1. Time and Schedule Performance

One of the most widely documented advantages of modular and off-site systems is significant schedule compression. Controlled factory environments enable parallel off-site fabrication and on-site preparation, reducing project timelines typically by 25–60%, with isolated cases reporting up to 70% reduction for fully volumetric systems compared with conventional sequencing [

7]. Studies in North America and Asia report even greater gains in large-scale housing projects, where modular fabrication allows predictable takt-time scheduling. This temporal efficiency translates directly into lower financing costs and faster revenue generation, critical in high-interest or speculative markets.

4.2. Cost and Economic Efficiency

OSC can lower total project costs compared to conventional methods, primarily due to reduced material waste, decreased labour requirements, minimal on-site work, fewer defects, lower risks and delays, and the efficiencies gained through controlled factory manufacturing [

6]. Nevertheless, cost outcomes are more variable. Across 41 comparative studies, most reported savings from industrialised systems, with cost reductions ranging from 7% to 50%; however, some projects experienced increases of 26–72% where learning curves or transport inefficiencies dominated [

7]. Yet, these savings depend heavily on utilisation rates and logistics efficiency. High initial investment for factory setup, transportation costs, and the need for precision-fit tolerances can offset unit savings when production volumes fall below breakeven thresholds. Consequently, while modular delivery demonstrates strong cost predictability, it has not universally achieved cost reduction at the enterprise level.

4.3. Quality and Precision

Quality improvement is one of the proven advantages of IC. Controlled factory environments enable rigorous supervision, consistent workmanship, and repeatable production, reducing defects and on-site rework [

24,

25]. Continuous refinement through standardisation supports long-term quality management and lifecycle durability, strengthening client confidence and compliance in performance-rated markets such as Europe and Australia.

4.4. Safety and Labour Productivity

Off-site manufacturing significantly improves worker safety by reducing hazardous on-site exposure. Studies reported up to 80% fewer accidents. Productivity also rises as repetitive factory tasks increase efficiency and limit weather-related delays [

26]. However, these gains rely on sustained investment in workforce training as the shift from craft-based to process-driven work requires new technical skills.

4.5. Waste, Carbon, and Environmental Performance

A growing body of research demonstrates that IC practices, such as prefabrication and modular methods, consistently achieve superior outcomes in waste reduction, energy efficiency, and overall sustainability performance compared to conventional construction approaches [

32]. Studies analysing waste generation rates (WGRs) reveal that prefabrication consistently produces less waste per unit area when compared to conventional construction techniques. For example, a cross-sectional study found that the average WGR for prefabricated buildings was 0.77 ton/m

2, significantly lower than the 0.91 ton/m

2 recorded for conventional buildings [

27]. Prefabrication’s controlled factory processes, material standardisation, and just-in-time (JIT) logistics minimise offcuts, contamination, and landfill burden [

28,

33,

34]. Moreover, factory-based manufacturing improves energy efficiency, allows cleaner energy use, and supports modular designs that are suitable for reuse and recycling, lowering embodied carbon [

28,

29,

30]. However, it is essential to recognise that the scale of improvement depends on the local manufacturing practices, logistics, and the degree of supply chain integration [

31]. In some cases, the transportation of prefabricated modules could partially offset carbon savings if not managed efficiently [

30,

35]. Nevertheless, IC offers a context-dependent but promising pathway toward sustainable circular building practices [

30].

4.6. Business Model Advantages of Industrialised Construction

A business model is characterised by the combination of content, structure, and transaction management within a company, allowing value generation, provision, and retention [

36]. Traditionally, construction has operated under a project-by-project logic, where each contract is treated as a discrete undertaking with unique specifications, temporary teams, and fragmented supply chains. Revenue is usually based on either reimbursing the builder’s actual costs plus a set fee or paying a single fixed price agreed upfront for the whole job. Design changes are common during construction, often driven by client requests or site conditions, which can lead to rework, delays, and adversarial relationships among stakeholders. Projects may also fail due to inadequate project management practices [

37,

38].

In contrast, IC introduces a fundamentally different economic architecture. When implemented through platform-based systems, particularly those aligned with DfMA principles, housing is treated as a repeatable product family rather than a custom-made object [

39]. Standardised interfaces and modular component libraries allow multiple architectural configurations while maintaining manufacturing efficiency [

40]. This approach spreads design and tooling costs across multiple projects, reduces marginal costs, and enables operational efficiencies that are absent in traditional models [

41].

4.7. Key Message

IC consistently delivers measurable gains in efficiency, quality, and sustainability at the project level but struggles to convert these into durable business-level advantages. The following section examines the systemic financial, regulatory, logistical, and socio-cultural barriers that underpin this persistent misalignment between operational success and market resilience.

5. Key Challenges in Industrialised Housing

In Australia’s low-rise housing market, stakeholder surveys identify seven “critical” barriers: business models misaligned with OSC, on-site interface and tolerance issues, weak market demand for prefabricated products, and slightly higher perceived costs, among others (with workforce shortages and job loss concerns ranking comparatively lower). These findings point to commercial fit and site-interface management as the most immediate levers for uptake [

6].

A recent risk-assessment study of modular construction projects in developing economies identified twelve recurring critical risks, ranked through a Fuzzy Delphi–FUCOM framework. The top factors included inadequate skills and experience in modular delivery, limited capacity of local manufacturers, restricted flexibility for design changes once fabrication begins, and transportation constraints. The findings emphasise that insufficient expertise and manufacturing infrastructure amplify schedule and quality risks when off-site production is introduced into underdeveloped supply chains [

22].

Despite growing policy attention and technological maturity, IC for housing continues to face systemic barriers that constrain scalability and long-term viability. These challenges are multi-dimensional, spanning finance, design, logistics, regulation, and human capability [

4], and collectively explain why industrialisation remains a niche rather than a mainstream delivery model in most regions.

5.1. Financial Barriers and Business Model Fragility

High capital requirements and unstable demand remain the most significant impediments to industrialised housing. Establishing off-site manufacturing facilities requires substantial upfront investment in plant, equipment, and digital infrastructure, while financial returns depend on maintaining a continuous production pipeline. Market volatility, speculative development cycles, and fragmented procurement practices often lead to underutilisation of factories, eroding profitability. Many modular manufacturers operate with thin margins and limited cash flow resilience, rendering them vulnerable to short-term demand shocks.

A promising mitigation strategy lies in government-backed bundled procurement and long-term framework agreements. By aggregating demand across public-sector housing programmes such as those implemented in the UK, Singapore, and Japan, governments can stabilise production volumes and justify capital expenditure. Complementary financing mechanisms, including low-interest manufacturing loans and insurance-backed assurance schemes, can further de-risk private investment in modular pipelines.

The reviewed literature indicates that scaling industrialised construction depends not only on technical solutions but also on delivery and finance arrangements that stabilise demand, allocate risk, and reduce coordination overheads. Across the studies examined, three recurring model directions can be identified. First, pipeline and demand-aggregation approaches are used to reduce factory underutilisation risk and enable repeatable production. Second, de-risking and assurance mechanisms are reported as pathways to improve insurer confidence by making quality and delivery risks more transparent and transferable. Third, platform and data-enabled delivery approaches are discussed as mechanisms to reduce redesign and transaction costs by improving information continuity from configuration and design through manufacturing and installation.

5.2. Design Flexibility and Mass Customisation Tensions

The repetitive nature of DfMA processes limits design freedom, particularly in small-scale residential projects requiring site-specific adaptation [

6,

25]. Current modular catalogues rarely meet diverse client needs without bespoke design effort, undermining the anticipated time and cost advantages [

23].

Industrialisation inherently depends on standardisation, yet housing markets demand diversity and architectural individuality. This tension between efficiency and flexibility has historically constrained client acceptance [

35]. Rigid modular grids often fail to accommodate varied site conditions, regulatory nuances, and consumer preferences. As a result, developers and designers perceive IC as limiting creativity and adaptability.

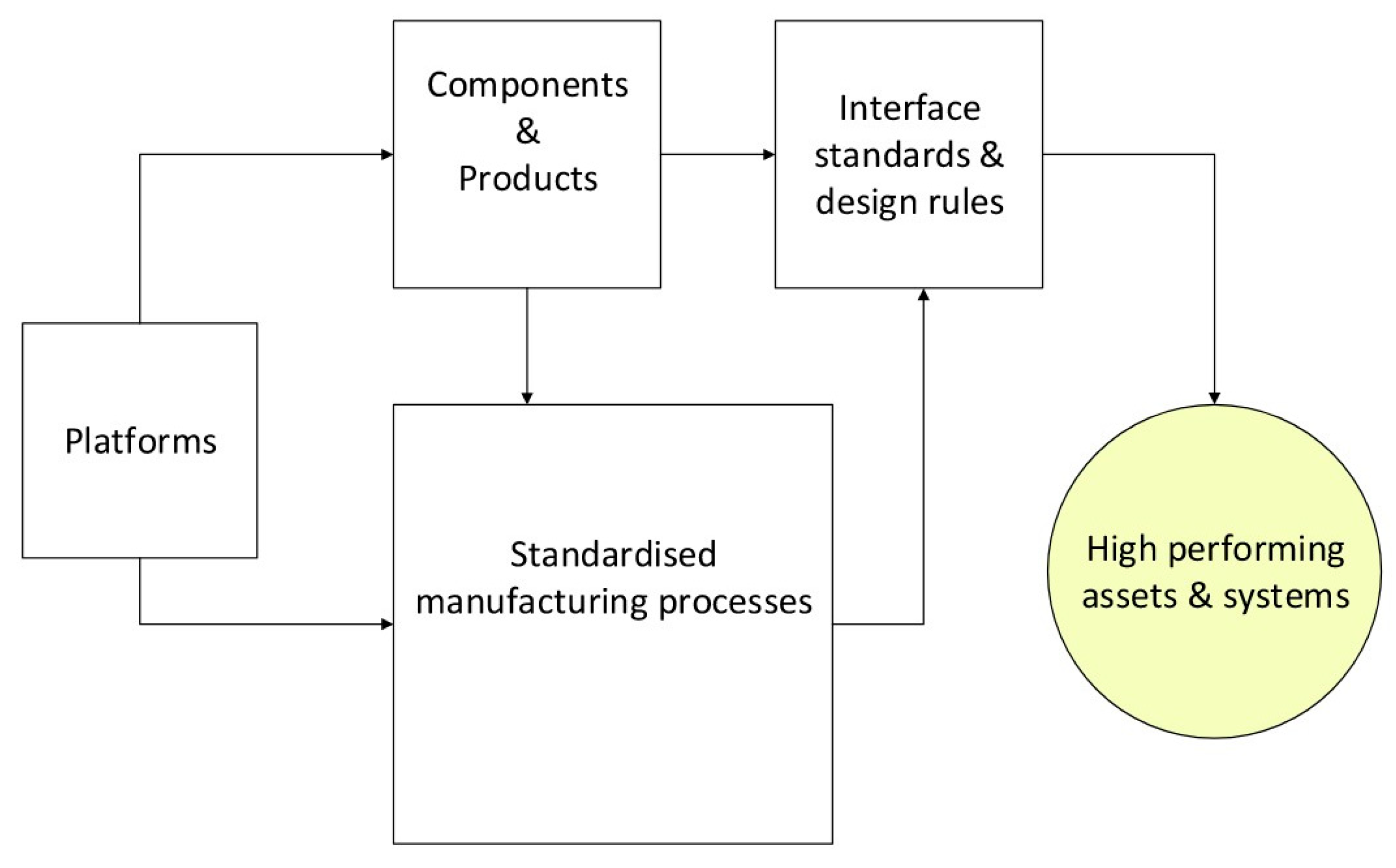

Emerging platform-based DfMA (P-DfMA) approaches offer a pathway to balance this trade-off. By standardising component interfaces rather than entire building forms, P-DfMA frameworks enable multiple configurations within a controlled ruleset. This allows mass customisation, offering variety through the recombination of standard parts while preserving manufacturing efficiency. Laovisutthichai et al. [

18], through an empirical pattern analysis in residential modules, show that mass customisation emerges from stable dimension-coordinated modules and repeatable space sets, enabling variety without sacrificing repetition and scale. Nevertheless, achieving widespread adoption requires open digital libraries, parametric configurators, and design-to-manufacture workflows that allow architects to engage creatively within industrial constraints (

Figure 3) [

35].

5.3. Logistics and Transportation Constraints

The physical limitations of module size, weight, and transport regulations pose ongoing challenges to scalability [

25,

43]. Oversized modules require special-purpose permits, escorts, and route planning, significantly increasing freight costs and the risk of damage during transit. Geographic dispersion between factories and construction sites further compounds logistics complexity, particularly in countries like Australia and Canada with large spatial territories. As an illustrative benchmark, US oversize transport permits typically trigger above 2.59 m wide, 4.27 m high, or a gross vehicle weight over 36.3 tonnes; permit routes can also restrict travel times and require pilot cars and bridge-clearance checks [

44]. In Australia, general heavy-vehicle dimension limits without a special permit are around 2.5 m wide and 4.3 m high. Loads exceeding those limits are typically classed as oversize/overmass and require a special permit. For example, in Western Australia, oversize/overmass permits may allow loads up to about 5.5 m wide and 5.5 m high when classified as large indivisible items [

45]. A growing trend toward hybrid “kit-of-parts” systems seeks to alleviate these issues by breaking volumetric modules into transportable sub-assemblies or 2D panelised elements that can be efficiently transported and assembled on site. Digital logistics modelling and parametric scheduling tools can further optimise delivery sequences, reduce idle time, and improve material-handling efficiency. However, the transition to such hybrid systems requires harmonised design standards and robust digital traceability between factory and site. Reviews show repeated use of volumetric bathroom pods (and some kitchens) across modular and mixed systems, reinforcing the practical value of pods within hybrid kits of parts [

46].

5.4. Design Complexity and Late-Stage Changes

IC depends on early design freeze for manufacturing precision, whereas traditional delivery often allows late revisions. Modular projects incur high penalties for design changes once fabrication starts [

47]. Adopting rule-based DfMA frameworks allows limited adjustment within shared parameters. Linking BIM with Manufacturing Execution Systems (MESs) ensures that authorised design changes update procurement and production data automatically, reducing the risk of mismatch.

5.5. Regulatory and Approval Barriers

The existing planning and building-code frameworks are often calibrated for traditional construction, creating uncertainty for modular systems. In many jurisdictions, approval processes lack clear pathways for factory-produced components, resulting in duplicated inspections and elongated lead times. Comparative evidence shows that policy by itself is not enough; adoption improves when authorities also codify the legal and contractual protocols for BIM data ownership, standard collaboration procedures, and DfMA-ready codes across the supply chain. National bodies (e.g., the ABCB in Australia; the UK HSE) are widely recognised as critical to coordinating this alignment, which reduces duplicated approvals and de-risks factory pipelines [

4]. Differences in state and local regulations further discourage investment in nationwide modular supply chains.

Progressive policy models demonstrate how digital rule-checking can streamline compliance. Singapore’s PPVC framework, for example, uses machine-readable codes to automate regulatory validation during design submission, reducing approval time significantly. Similar digital-approval pilots are emerging in the UK and Australia, yet broader adoption requires coordinated legislative reform and mutual recognition of prefabrication standards across agencies.

Evidence across 189 BIM–OSC studies shows that multi-stakeholder coordination is critical, with government incentive schemes specifically linked to growth in BIM–OSC adoption. Beyond policy intent, implementation hinges on common protocols: standardised component coding, agreed CDE data formats, and practical guidance for manufacturers and contractors. Evidence also emphasises the role of public-sector rules and incentives in normalising BIM-enabled OSC submissions and collaboration [

48].

5.6. Social and Capability Barriers

Beyond technical and regulatory challenges, the industrialisation of housing faces deep cultural and skill-related obstacles. Many architects, engineers, and contractors still associate prefabrication with low-quality or temporary structures, reinforcing outdated stereotypes [

6]. Additionally, education and training systems remain heavily oriented toward on-site construction trades, producing a workforce that is unprepared for data-driven manufacturing environments.

Building public and professional confidence demands targeted awareness programmes, demonstration projects, and accessible digital tools. Simplified gamified design interfaces can help to demystify modular design processes and allow broader participation by non-specialist stakeholders. Upskilling initiatives must likewise focus on developing cross-disciplinary competencies that combine design, manufacturing, and digital literacy to support the next generation of industrialised-construction professionals.

5.7. Enterprise Resilience and Lean Integration in Industrialised Construction

Operational advantages such as accelerated schedules, enhanced quality, improved safety, and reduced waste are evident in IC. However, these project-level efficiencies rarely translate into sustained commercial viability at the enterprise level [

49]. This disconnect arises partly from a persistent lack of research and strategic focus on business model innovation in housebuilding, where firms struggle to deliver housing that is affordable, scalable, high-quality, and sustainable [

50,

51].

A key factor in this fragility is the limited adoption of lean manufacturing principles. Lean-driven models prioritise flow, waste elimination, and customer-centric delivery [

52,

53]. Yet, many ventures fail to integrate these principles effectively due to limited knowledge and a project-focused approach that hinders the development of scalable platforms [

54,

55,

56]. Lean construction aims to reduce waste, maintain workflow, and maximise value delivery, with JIT methods enabling materials and components to arrive exactly when needed [

57,

58,

59].

Additional barriers include delays from manufacturers, inadequate machinery, limited workforce expertise, high initial costs, narrow margins for error, fragmented supply chains, and resistance to change [

60]. Leadership support, lean training, and digital integration are essential for establishing resilient and repeatable business models.

5.8. Synthesis

These interlinked challenges show that the barriers to scaling industrialised housing are systemic rather than purely technological [

61]. Addressing them will require closer coordination between finance, policy, design, logistics, and workforce capability, not only new tools. The next section, Industrialised Construction Systems and Digital Platforms, examines how specific digital frameworks and hybrid modular strategies may help to reduce these barriers.

6. Industrialised Construction Systems and Digital Platforms

The transition from traditional modular construction toward fully integrated platform-based systems represents a defining shift in the industrialisation of housing. Overcoming the barriers outlined in the previous sections requires more than incremental technological upgrades; it necessitates a systemic reconfiguration of how design, manufacturing, and business processes interconnect through digital platforms [

61]. These platforms transform IC from fragmented project-specific applications into unified ecosystems of components, data, and services.

In this review, “platform” is understood not just as prefabrication but as a structured system and approach comprising assets (components, processes, rules, and interfaces) that can be recombined to produce different housing outcomes. Practically, interview evidence shows that platform work is anchored in three principles [

62].

Organisational: shifting from one-off project teams to platform teams that curate shared component libraries, rules, and interfaces.

Technological: coordinating digital tools for configuration, rule sets, and manufacturing data.

Procedural: standardised workflows with feedback loops that reinforce repeatability.

IC can be understood through a “construction platform value chain” that includes five iterative stages: Initiate, Standardise, Design, Construct, and Operate [

61]. Key frameworks such as the RIBA Plan of Work (DfMA Overlay, 2nd Edition), Monash University’s Handbook for Design of Modular Structures, and the TfNSW Digital Engineering Framework, emphasise that early-stage standardisation, lifecycle data integration, and cross-disciplinary feedback are essential to achieving scalable and resilient construction platforms [

61].

Construction platforms can be classified as physical, digital, or hybrid based on how supply chain nodes, suppliers, manufacturers, distributors, and clients exchange information, material, financial, and emerging carbon flows [

61].

Physical platforms focus on manufacturing data and one-directional material flow [

61].

Digital platforms coordinate people and data across supply chain nodes through bidirectional information exchange [

61].

Hybrid platforms integrate cyber–physical systems, where real-world conditions are mapped to digital twins using embedded sensors and actuators. These systems demand stronger governance on intellectual property, data privacy, liability, and security as they link digital control with physical production [

61].

Prefabrication refers to the factory manufacturing and preassembly of building components, with the site mainly used for assembly. Modular construction is a subset of prefabrication using standardised modules. Modular systems fall into two categories: 2D (panelised) and 3D (volumetric). Three-dimensional modules achieve higher factory completion and time savings for repetitive programmes such as hotels or hospitals but face transport and flexibility limits; 2D panels are easier to transport and adapt to site-specific design, although more assembly occurs on site [

61].

6.1. System Typologies: 2D, 3D, and Hybrid Modular Approaches

IC can be broadly categorised into three system types: 2D panelised, 3D volumetric, and hybrid modular systems, each offering unique performance characteristics.

The 2D panelised system consists of prefabricated wall, floor, and roof components manufactured off site and transported to the construction site for assembly. These systems can be preassembled by up to 70% before delivery, thereby reducing on-site construction time and achieving cost savings of approximately 17%. In addition to improved efficiency, the 2D approach offers enhanced flexibility in transportation and facilitates integration with conventional building methods. In contrast, the 3D volumetric system comprises fully fabricated structural and service modules that are transported as complete units and assembled on site. This method enables superior quality control and accelerated installation but is often constrained by transportation logistics and design adaptability. Nonetheless, 3D volumetric construction can reduce overall costs by approximately 24% compared to conventional techniques. When 2D and 3D methods are combined to take advantage of both prefabrication approaches, the result is a hybrid system [

47]. This configuration optimises transport efficiency, installation speed, and design flexibility, offering a scalable model for both low-rise and mid-rise housing.

6.2. From Modular Products to Digital Platforms

Digitally integrated construction platforms mark a shift from one-off project execution to continuous product–service ecosystems. In these systems, the platform functions as a shared environment where design data, manufacturing parameters, and component libraries are standardised and interconnected. Rather than producing bespoke designs for each project, platform logic allows the reuse and recombination of validated modules, ensuring consistency and scalability [

61]. This mirrors the evolution of the automotive and aerospace industries, where product platforms underpin mass customisation and lifecycle profitability. Within construction, such platforms enable interoperability across disciplines, linking architects, engineers, fabricators, and supply chain partners within a unified data environment.

A recent systematic review of 52 studies on digital platforms in the AEC industry conceptualises these platforms as socio-technical systems that combine technological infrastructure with organisational governance mechanisms [

63]. The review distinguishes different types of platforms and identifies several thematic dimensions that shape platformisation in construction, including design and development, business models, governance, optimisation, complementors, sustainability, and collaboration. It also proposes an integrative model that links phases of platform adoption and integration with the challenges and benefits experienced by different stakeholders across the construction supply chain, which aligns with the multi-layered logic developed in this review.

6.3. Component Marketplaces and Configurators

An essential feature of digital IC ecosystems is the component marketplace, a structured repository where validated building elements such as wall panels, façade modules, mechanical pods, or structural connectors are stored, shared, and procured. These marketplaces promote transparency, reduce duplication, and facilitate collaborative innovation. Designers can access parametric objects embedded with manufacturing and compliance data, enabling real-time cost, carbon, and constructability feedback during design exploration.

Configurable design interfaces further democratise this process. By using visual parametric configurators (e.g., web-based or BIM-integrated tools), designers and clients can assemble building layouts through rule-based logic, much like configuring a digital product. Such tools streamline design workflows, reduce rework, and accelerate early-stage decision-making while maintaining compatibility with factory production data.

Practitioner insights emphasise that standardisation conducted by those close to construction realities releases design capacity and amplifies benefits through repetition. In parallel, productisation operationalises the platform by making supply engagement reliable, provided that the procurement frameworks are aligned [

62].

6.4. Business Model Transformation

A shift from project-based delivery to product–service platform models is evident in IC [

64,

65,

66]. Housing is redefined as a configurable product family built from standardised interoperable components [

65,

67]. This transformation enables firms to distribute design and tooling costs across multiple projects, thereby reducing marginal costs over time and promoting repeatability and scalability [

39,

40,

41].

This evolution aligns with lean construction principles, emphasising value stream optimisation, waste reduction, and pull-based production [

68]. Standardised component interfaces and design rules enable end-to-end value stream mapping, mitigating construction wastes, such as rework, waiting, and over-processing. Digital platforms integrating BIM, DfMA libraries, and Manufacturing Execution Systems create closed-loop feedback mechanisms, supporting continuous improvement and turning each project into a data-rich learning opportunity [

46,

69,

70,

71].

Revenue extends beyond construction to include design-as-a-service, performance-based maintenance contracts, and monetisation of lifecycle data [

66]. This shift enables the firm to transition from a traditional contractor to an integrated long-term service provider, emphasising standardisation, collaboration, and lifecycle value creation over short-term project margins [

66].

6.5. Benefits, Limitations, and Risks

Platformisation offers clear advantages: scalability, repeatability, quality assurance, and reduced waste. However, it also introduces new forms of dependency and concentration risk. Proprietary platform ecosystems risk monopolising market access and stifling innovation if not governed through open standards [

72]. Data interoperability, intellectual-property rights, and cybersecurity remain critical challenges. Moreover, standardisation can inadvertently suppress design diversity and regional adaptability if implemented rigidly. To balance efficiency with inclusivity, future IC platforms must embrace open-source data schemas, transparent rule sets, and shared component libraries that allow broad participation across the industry.

7. Emerging Enablers and Solutions

IC is undergoing a fundamental transformation driven by digitalisation, platform thinking, and policy reform. The enablers shaping this transition can be broadly grouped into three interrelated domains: (a) design and platform innovation, (b) digital integration and lifecycle traceability, and (c) policy, financial, and sustainability frameworks. Together, these form the foundation for scaling modular and off-site construction from isolated exemplars to a resilient data-connected ecosystem.

7.1. Design and Platform Innovation

7.1.1. Platform-Based DfMA (P-DfMA)

At the design and manufacturing interface, the most influential innovation is the evolution of Platform-Based P-DfMA. This approach standardises component interfaces while allowing layout flexibility [

61], enabling buildings to be assembled from interoperable parts rather than bespoke designs. The platform operates as a “kit-of-parts” system where structural, envelope, and service components follow shared dimensional and connection rules. This framework enhances interchangeability, facilitates automated design validation, and supports mass customisation without sacrificing manufacturing efficiency.

It is important to distinguish product platforms from DfMA. Product platforms emphasise modularity, standardised interfaces, and mass customisation, enabling complementors to innovate around a stable core; by contrast, DfMA typically pursues integrality, reducing part counts, and simplifying assembly to improve quality and productivity. These logics are not mutually exclusive, but they carry different organisational implications: product platforms favour loosely coupled ecosystems and scalable variety, whereas DfMA favours tighter integration and design control. In practice, firms often combine both, using platform families for most components and reserving DfMA for specific sub-systems that benefit from integrality [

72]. Recent studies have begun to formalise DfMA as a design methodology rather than a construction management tool. Laovisutthichai and Lu [

18] developed an analytical framework that visualises modular building design patterns through several dimensions, including nomenclature, spatial relations, module shape, module dimension, and convex break-up. Their findings from 39 Hong Kong residential projects highlight that mass customisation can emerge from rigorous dimensional coordination and repetitive standardisation rather than bespoke variation. This aligns closely with the argument that architectural creativity in modular construction stems from the controlled recombination of fixed components, not their unrestricted alteration.

Recent research highlights that product platforms defined as modular systems combining shared technical, process, and knowledge domains can act as a bridge between IC and Circular Economy (CE) objectives. By standardising components and workflows, platforms can increase resource efficiency, enhance reuse potential, and reduce the fragmentation that typically limits innovation in construction supply chains [

73].

7.1.2. Middle-Out Design Logic

Recent research highlights the limitations of purely top-down (concept-driven) and bottom-up (component-driven) modular strategies. A “middle-out” design logic enabled by parametric and rule-based platforms bridges the gap by coordinating design intent at the building scale while preserving component-level flexibility. This dual hierarchy aligns architectural design freedom with factory precision and logistics efficiency, representing a step-change in how modular buildings are conceived and managed across disciplines.

7.1.3. Gamified Modular Design Tools

Another emerging trend is the use of gamified configurators that enable both designers and clients to interactively explore modular layouts. These tools convert complex parametric relationships into intuitive visual interfaces, reducing the technical barriers for non-experts. They boost early-stage engagement, speed up decision-making, and promote public understanding of modular principles. Such tools also play an educational role, helping stakeholders to visualise how design choices impact manufacturability, material use, and environmental performance.

7.1.4. Gamified Sustainability Awareness

Gamification can further be extended to sustainability learning by integrating game-based educational tools that both enhance motivation and reinforce sustainability knowledge, subsequently fostering environmentally responsible behaviours among learners. Interactive dashboards that display real-time estimates of carbon footprint, energy efficiency, and material waste for different configurations empower users with feedback mechanisms grounded in game-based learning approaches and stimulate critical thinking and engagement while supporting a deeper understanding of sustainability impacts and motivating more sustainable decision-making practices [

74]. In addition, incorporating elements such as rewards, story-driven scenarios, and customisable roles within these dashboards can further enhance learner motivation and engagement, echoing findings on the effectiveness of immersive gamified educational experiences for sustainability education [

75]. Also, research highlights that simulation-based gamification, when merged with collaborative problem-solving and adaptive scaffolding, yields statistically significant gains in sustainability literacy and environmental awareness, particularly when tailored to diverse cultural contexts and learner backgrounds. It not only encourages sustainable design thinking but also enhances understanding of the compromises involved in industrialised housing systems.

7.1.5. Integrating Lean and JIT

Lean and JIT principles improve flow efficiency and reduce waste. Practical enablers include digital coordination tools, integrated delivery models, cross-disciplinary training, and standardised operational frameworks [

58,

76]. In manufacturing-oriented projects, JIT enables precise scheduling of prefabricated components and materials. Combined with lean processes and digital planning, this enhances predictability, reduces inventory costs, and improves project flow [

77,

78]. Strengthening industry–academia collaboration, developing operational standards, and promoting digital integration are crucial for translating lean–JIT principles from theory into routine practice.

7.1.6. Hybrid Modular Systems

A practical innovation gaining momentum in IC is the hybrid use of 2D panelised and 3D volumetric systems, designed to balance production efficiency with transport and on-site adaptability [

43]. In these systems, flat wall and façade panels can be easily transported and assembled on site, while fully finished 3D modules, such as bathrooms or kitchens, are manufactured in controlled factory settings where precision and quality are crucial. This hybridisation enhances scalability and allows industrialised methods to penetrate diverse housing typologies [

79].

7.2. Digital Integration and Lifecycle Traceability

Achieving the intended efficiencies of IC requires seamless digital collaboration from conceptual design to final delivery. Digital integration technologies such as Blockchain, the Internet of Things (IoT), and digital twins (DTs) play a critical role in improving lifecycle traceability, transparency, and data interoperability within the industrial housing sector. These technologies enhance information management across all the stages of the asset lifecycle, supporting CE principles and more efficient decision-making [

80,

81]. Blockchain ensures secure and transparent traceability of information, addressing persistent issues like data fragmentation and interoperability in construction projects [

80,

81]. The adoption of the IoT enables real-time tracking and management of lifecycle data, thereby strengthening the implementation of CE strategies in housing [

81]. DTs further enhance asset management by improving the integration between digital and physical models, facilitating more effective lifecycle management and performance monitoring [

82].

Furthermore, recent research suggests that BIM plays a key role in enhancing environmental performance and decreasing the carbon emissions of industrial housing projects. By automating and integrating design and construction data, BIM enables faster and more accurate LCA and helps to identify areas for design improvement [

83]. In prefabricated projects, this improvement leads to a realistic environmental advantage of industrial construction over traditional methods, including a significant reduction in greenhouse gas emissions over the life of the building [

84]. These achievements in large-scale construction could reduce the contribution of the building sector to climate change and make sustainable goals related to clean energy, climate, and sustainable cities more achievable. However, to fully exploit the potential of BIM–LCA, there is a need to develop standards and documented procedures to ensure that assessments are carried out with sufficient accuracy and detail at all stages (especially operation and end of life) using real-time assessments [

85]. In addition, training experts in BIM–LCA tools and strengthening digital infrastructure in prefabricated factories are essential steps ahead [

86].

Despite these advancements, challenges related to technology standardisation and regulatory frameworks remain barriers to broader implementation in industrialised housing projects [

87]. Integrating emerging technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI) and big data analytics is expected to optimise LCA and deepen the understanding of environmental impacts across the construction process [

88,

89].

Overall, integrating digital technologies with industrial construction approaches will not only reduce carbon footprints and promote sustainability but will also bring innovation and efficiency to the construction industry of the future.

7.3. Policy, Financial, and Sustainability Enablers

While technological progress underpins industrialisation, policy and finance remain decisive in determining scalability. Clear assurance mechanisms, such as the Australian Building Codes Board (ABCB) guidelines, can increase investor and insurer confidence by providing consistent quality and compliance benchmarks for modular systems.

The evidence indicates a persistent mismatch between governance settings and disassembly practice. While design-stage enablers proliferate, regulations, permitting, and procurement rarely anticipate planned disassembly or material reuse, creating friction precisely where circular value is realised. The imbalance reinforces a design-centric focus and slows circular adoption in housing. A policy shift toward performance-based codes, reuse-ready permitting, and transparent public procurement would better connect re-planning and disassembly with industrialised delivery [

90].

7.3.1. Aggregated Procurement Pipelines

Large-scale framework agreements, exemplified by the UK’s MMC programmes and Singapore’s BCA procurement model, mitigate market volatility by aggregating demand across multiple projects and agencies. Such predictable pipelines justify long-term capital investment in factories and encourage private-sector participation.

7.3.2. Targeted Sustainability Strategies

Early-stage lifecycle assessments, modular waste reduction targets, and carbon-accounting frameworks can establish sustainability as a measurable performance criterion rather than a competitive marketing feature. Early assessments can influence design decisions significantly, maximising environmental performance even with limited data [

91]. Designing sustainable products requires overcoming information deficits and enhancing eco-design thinking in early decision-making processes [

92]. Incorporating rigorous LCA and carbon footprint investigation methodologies equips decision-making processes with quantifiable environmental insights, thereby promoting the selection of low-carbon materials and practices that are consistent with CE principles and climate goals [

93].

Moreover, examining policy mechanisms aimed at incentivising circular design practices in industrialised housing reveals diverse strategies that can effectively advance sustainability across the sector. The reviewed studies emphasise mechanisms such as targeted industrial policies, specialised economic zones, and innovative voluntary initiatives that collectively facilitate the housing sector’s transition toward more sustainable and resource-efficient practices. Active industrial policy is crucial for driving the green transition, demonstrating that government intervention, through instruments such as tax regulations, fiscal incentives, and targeted subsidies, can effectively shape sustainable practices across sectors, including housing [

94]. Special economic zones can facilitate development and promote innovative design practices by creating specialised locational advantages that adapt over time, enhancing sustainability efforts in industrialised housing [

95]. Voluntary environmental programmes, can provide businesses with additional incentives to adopt circular design principles, demonstrating that non-mandatory approaches can lead to improved environmental performance [

96]. Adopting comprehensive policy frameworks that integrate these diverse mechanisms is essential for supporting a broader transition toward circular design within the housing industry, ensuring that sustainability becomes a priority at all levels of governance [

97].

7.3.3. Planning and Regulatory Reform

Recent pilots in Singapore and the United Kingdom are testing a shift from the conventional design–approval–build sequence to design–build–approval workflows supported by digital rule-checking. In these systems, planning and building codes are encoded as machine-readable rules that check compliance during design rather than only after drawings are complete. Early evidence suggests that this approach can shorten approval times and reduce uncertainty, but it also raises questions about accountability, data governance, and the role of regulators. Further work is needed to understand how these tools can be integrated into existing planning systems without undermining transparency or public trust.

In Australia, prefabricated bathroom pods have been formally accepted across plumbing jurisdictions under the NCC, and federal policy in 2024 explicitly recognised MMC/OSC as part of the response to the national housing shortage, signalling that approvals and standards frameworks are adapting to off-site delivery [

6].

7.3.4. Policy Sandboxes and Institutional Alignment

To achieve a lasting impact, governments should establish policy sandboxes—controlled environments where new digital-approval systems and modular standards are tested collaboratively with regulators and industry. This approach de-risks innovation and builds institutional confidence in industrialised methods. Consistent policy alignment across housing, sustainability, and infrastructure departments is equally critical for achieving systemic transformation.

8. Research Gaps and Future Directions

Although industrialised construction has made notable progress in technological capability and policy recognition, several critical research and implementation gaps persist. Bridging these gaps is essential for transitioning from fragmented innovation to cohesive data-driven ecosystems that support scalable low-carbon housing delivery.

8.1. Data Continuity and Digital Fragmentation

Despite widespread adoption of digital tools such as BIM, data exchange between design, manufacturing, logistics, and operations remains fragmented. Current workflows often rely on manual file transfers and incompatible software ecosystems, leading to information loss and duplicated effort. This disconnection undermines the traceability and reliability that IC aims to achieve.

Although BIM is often discussed as a multi-dimensional environment, most of the literature reviewed still relies heavily on 3D modelling. Work that extends BIM into 4D, 5D, or beyond is present but generally limited to isolated case studies rather than continuous repeatable workflows. As a result, time, cost, environmental data, and operational information are rarely linked back to the core model, and the digital chain breaks once fabrication or site work begins. This suggests that the challenge is not simply improving BIM capability but establishing a data environment that remains connected across design, manufacturing, and operation [

48].

Future research should prioritise data continuity frameworks that enable seamless interoperability between BIM, MES, ERP, and asset management systems. Open-standard data environments built on IFC, ISO 19650, and API-based integration can ensure consistent information flow across all project stages. Establishing industry-wide protocols for data governance, security, and ownership will also be critical for achieving a truly connected construction ecosystem.

8.2. Artificial Intelligence and Automated Design Optimisation

The increasing adoption of AI technologies in the AEC industry is making project management more efficient and improving how construction projects are planned and executed [

98]. Current applications include platforms that use machine learning and predictive analytics to automate parts of planning and control. These tools can, for example, help to configure modular layouts, optimise structural systems, support project management and supply chain risk analysis, and assist with lifecycle assessment [

99]. Integrating AI into platform-based DfMA workflows could also facilitate multi-objective optimisation, balancing cost, carbon, and comfort simultaneously during the early design phase.

While AI-enabled platforms hold great potential for the AEC industry, they are still in the early stages of development and require further research to meet the practical demands of real-world construction projects. The key challenges include the scarcity of training data, high computational costs, and the limited ability of deep learning models to generalise across different scenarios [

98]. Collaborative studies between academia, software developers, and policymakers could help to translate AI capabilities into verifiable code-compliant workflows.

DTs and Lifecycle Integration

DTs, which serve as dynamic virtual counterparts to physical systems, have become an essential tool for strengthening lifecycle integration across industries. When combined with lifecycle management, they support more informed decision-making, smoother data connections, and more sustainable practices. This integration also helps to tackle the ongoing challenges around interoperability and data fusion, making the overall process more coherent and effective.

Interoperability is essential for DTs to work seamlessly across all the stages of the lifecycle, enabling coordinated decision-making and smoother operational performance through unrestricted information exchange [

82,

100]. Data fusion across different DT models in life cycle settings creates a real-time link between virtual and physical assets, helping to manage the complexities that arise in dynamic processes [

101,

102]. Also, cognitive DTs use advanced technologies such as AI and machine learning to improve decision-making across the building lifecycle, demonstrating how automation and enhanced processes can strengthen overall building lifecycle management [

100]. Moreover, data integration frameworks help to tackle the challenges associated with urban DTs, emphasising the need for structured methods that support effective data coordination across the different phases of the lifecycle [

103].

Most existing applications, however, are still confined to pilot-scale use. Expanding the role of DTs in modular construction will depend on establishing standardised data structures, linking them with manufacturing databases, and deploying cloud systems that can handle high-frequency sensor inputs. Integrating DTs with policy tools, such as performance-based codes, could further enhance accountability and encourage higher-quality outcomes.

8.3. Machine-Readable Codes and Automated Compliance

Regulatory compliance remains one of the most time-consuming and uncertain aspects of modular project delivery. While digital rule-checking prototypes exist, such as Singapore’s CORENET X or the UK’s automated planning pilots, there is no universal framework for encoding building regulations into machine-interpretable formats.

Future research should focus on developing machine-readable regulatory ontologies that can be embedded directly within design software. This would allow real-time validation of design decisions against planning, building, and environmental codes, reducing rework and approval delays. Collaboration between standards bodies, software vendors, and government agencies will be necessary to establish consistent data structures and legal recognition of automated code validation.

8.4. Lifecycle Assessment (LCA) and Lifecycle Costing (LCC) Integration

The current trends in LCA and LCC within the industrialised building sector reflect a shift towards integrating sustainability considerations into cost and environmental impact evaluations. However, there is a notable gap in the integration of necessary data for effective sustainability assessments in the construction sector, which hampers comprehensive evaluation processes [

104]. Recent research emphasises the development of frameworks that promote sustainable construction practices and enhance decision-making through comprehensive cost estimations. Recent developments in LCC emphasise integrating economic, social, and environmental factors to enhance sustainable building practices [

105,

106]. Nevertheless, comprehensive reviews indicate variability in LCA methods and assessments across the sector, highlighting the need for standardised practices [

107]. Also, future research is encouraged to explore an integrated LCA and LCC at the urban scale to assess the environmental [

107] and economic impacts of industrialised methods comprehensively.

Moreover, integrating Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) into BIM platforms significantly enhances the assessment of embodied emissions associated with construction materials and assemblies. The reviewed literature supports the idea that such integration can dynamically streamline data analysis to facilitate a more effective evaluation of environmental impacts throughout the building lifecycle. Integrating EPDs into BIM allows designers to see real-time updates and run dynamic assessments of material and assembly emissions. When this is paired with a whole-building LCA framework, it becomes possible to optimise design choices more effectively, leading to more accurate evaluations and more sustainable construction outcomes [

108]. Studies indicate that establishing a clear framework for embedding EPDs into BIM can lead to meaningful reductions in embodied impacts through iterative design improvements [

109].

In addition, the rise of digital twin technologies opens up new possibilities that have not yet been fully explored. A significant gap identified is the lack of data integration necessary for effective LCA and LCC, which can be addressed through the synergistic use of DTs [

104,

110]. Inconsistent system boundaries within LCA frameworks often lead to disputable results; digital twins can mitigate this by supplying more consistent and standardised data sources [

111]. Integrating DTs with dynamic LCA methodologies also strengthens real-time monitoring and predictive analysis, advancing the overall quality of sustainability assessments [

112]. However, despite the potential of DTs in improving LCA and LCC assessments, challenges such as data interoperability and standardised methods remain significant barriers to implementation [

110,

113].

8.5. Interdisciplinary and Policy-Oriented Research

Finally, advancing IC requires interdisciplinary collaboration that bridges engineering, digital technology, economics, and governance. Research should move beyond isolated technical optimisation to encompass the socio-institutional frameworks that enable industrialisation. This includes developing metrics for CE performance, new education pathways for hybrid digital–manufacturing professionals, and models for cross-sector collaboration between government, academia, and industry.

9. Discussion

Industrialised construction continues to demonstrate clear advantages over traditional site-based delivery in areas such as construction time, predictability, quality, and waste reduction. However, these performance gains are not universal. They fluctuate across markets and project types, particularly when it comes to cost and long-term commercial resilience. In some cases, modular and off-site systems reduce overall expenditure, while in others the benefits are offset by high capital requirements, transport complexity, or steep learning curves. This suggests that industrialisation is not a uniform solution but a method whose success depends heavily on the maturity of supply chains, consistency of demand, and the wider economic and regulatory environment that surrounds it.

A comparison across different regions reinforces this point. Jurisdictions with coordinated policy settings, stable production pipelines, and well-established manufacturing capacity have generally achieved stronger outcomes and greater continuity in industrialised housing. Regions where procurement is fragmented, regulation shifts frequently, or demand rises and falls unpredictably tend to experience cycles of expansion, contraction, and factory failure. These patterns indicate that adoption is shaped less by the inherent qualities of modular systems and more by the alignment or misalignment between policy, industry structure, development finance, and risk distribution.

Across the literature, platform-based approaches appear to offer a promising response to this misalignment. When housing is treated as a product family with standardised interfaces rather than a series of bespoke projects, it becomes possible to combine repeatability with controlled variation. Hybrid 2D–3D systems, structured kits of parts, and component marketplaces are all attempts to balance the efficiency of manufacturing with the need for site-specific adaptation. Yet even in these examples, success is inconsistent. Technical innovation alone is not sufficient if data environments remain siloed, approvals are slow, or business models continue to operate on short project cycles rather than long production horizons.

Digital integration emerges as a recurring theme in this landscape, but it is also one of the weakest links. There is growing interest in AI-assisted configuration, rule-based design automation, lifecycle assessment tools, and digital twins, but these capabilities are rarely connected through a continuous data stream that extends beyond design. Models often lose value once fabrication begins, and operational information seldom feeds back into the system. The result is a digital stack that looks advanced on the surface but functions as a series of disconnected layers in practice. If industrialised construction is to function as a genuine platform, the connection between design data, manufacturing, logistics, and long-term performance will need to be strengthened dramatically.