Numerical Modelling and Experimental Validation of FRCM-Reinforced Concrete Beams Using Macro-Modelling Techniques

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review of Experimental Tests

2.1. Materials

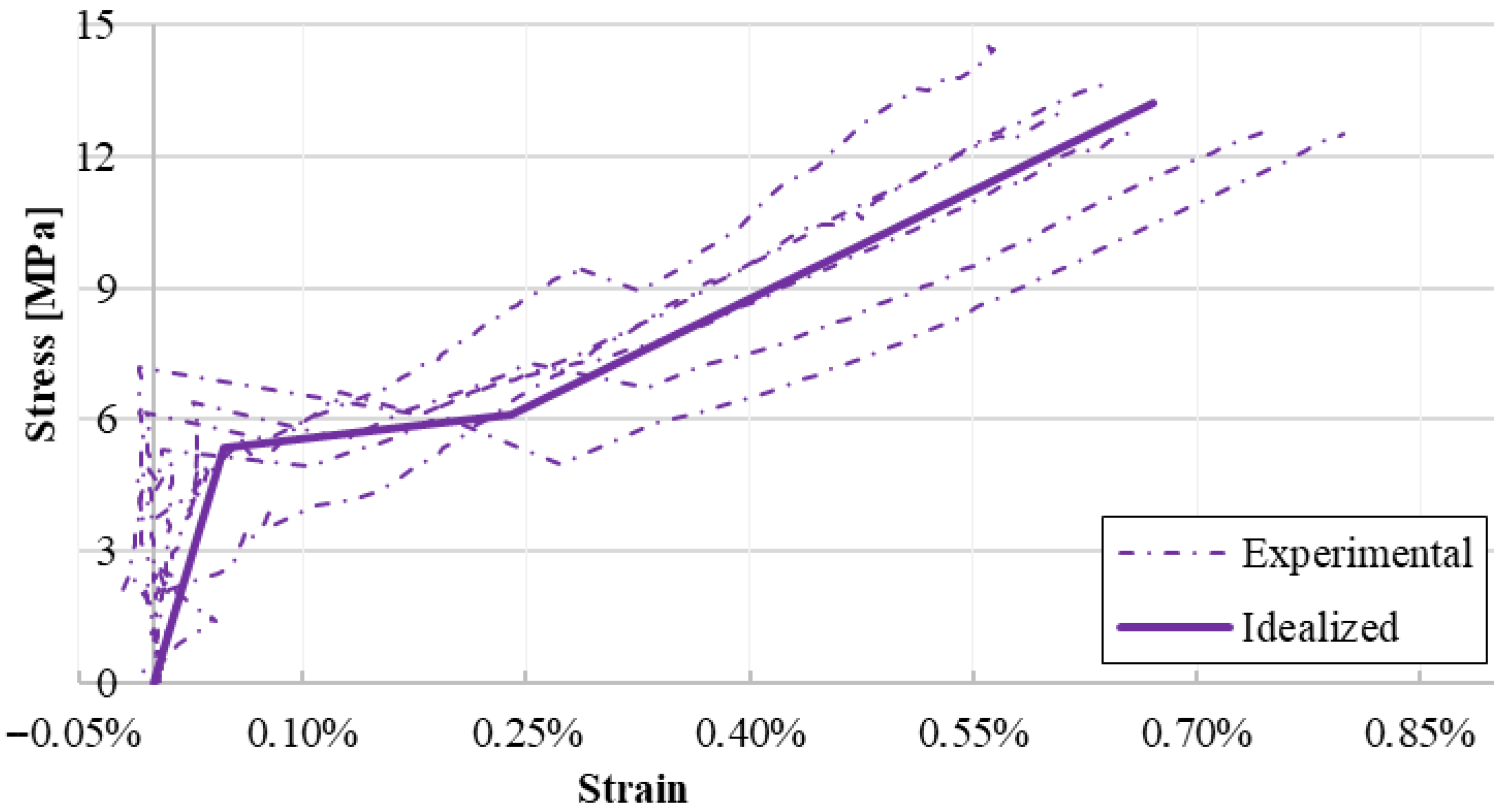

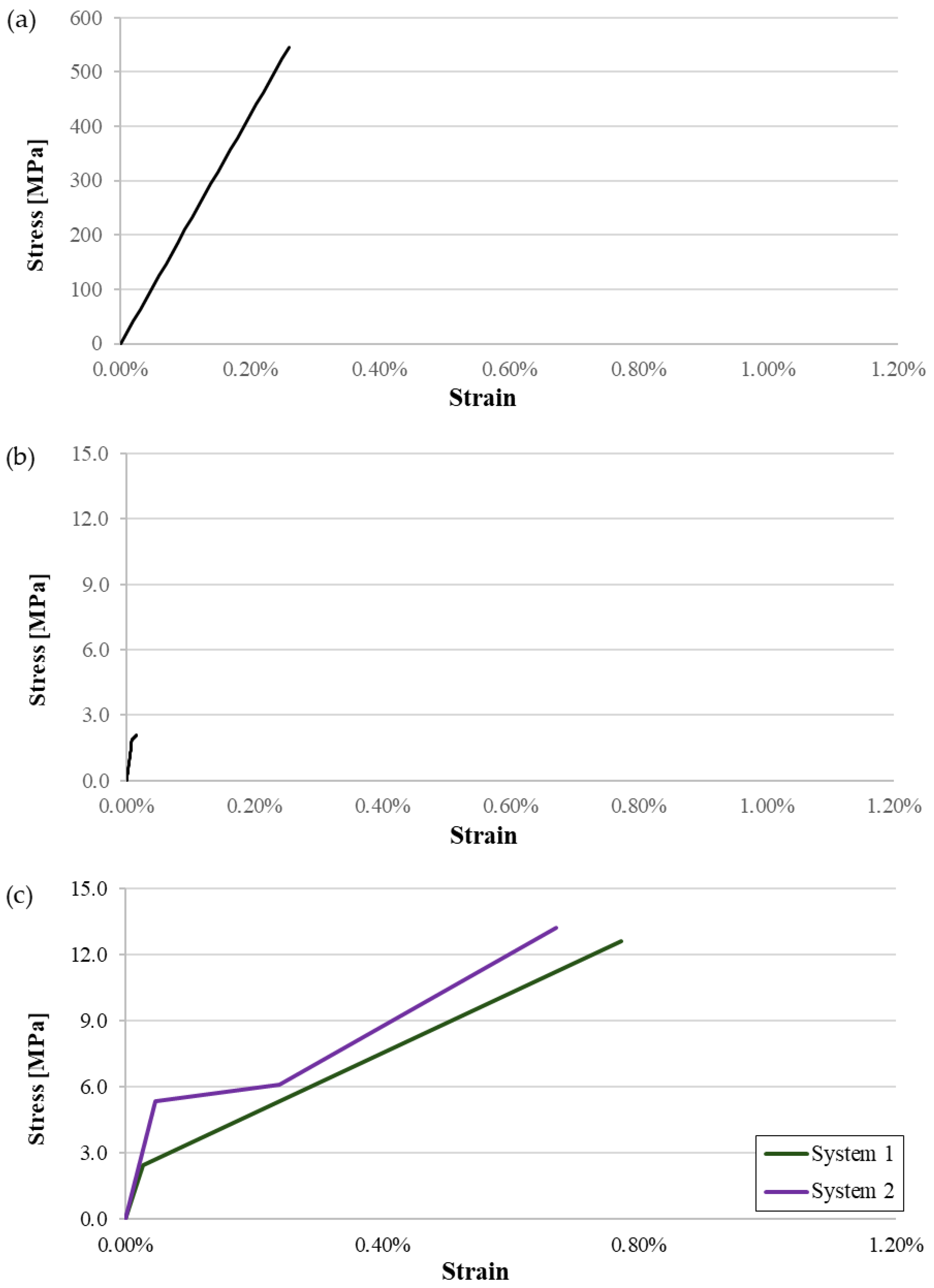

2.2. Direct Tensile Tests

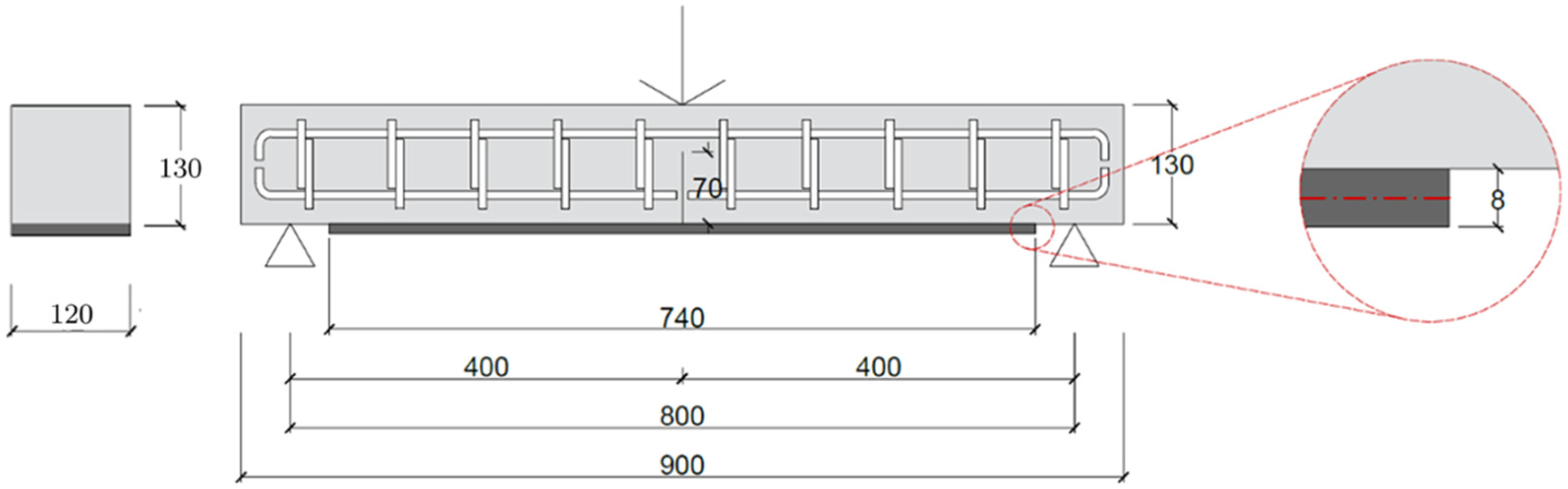

2.3. Bending Tests

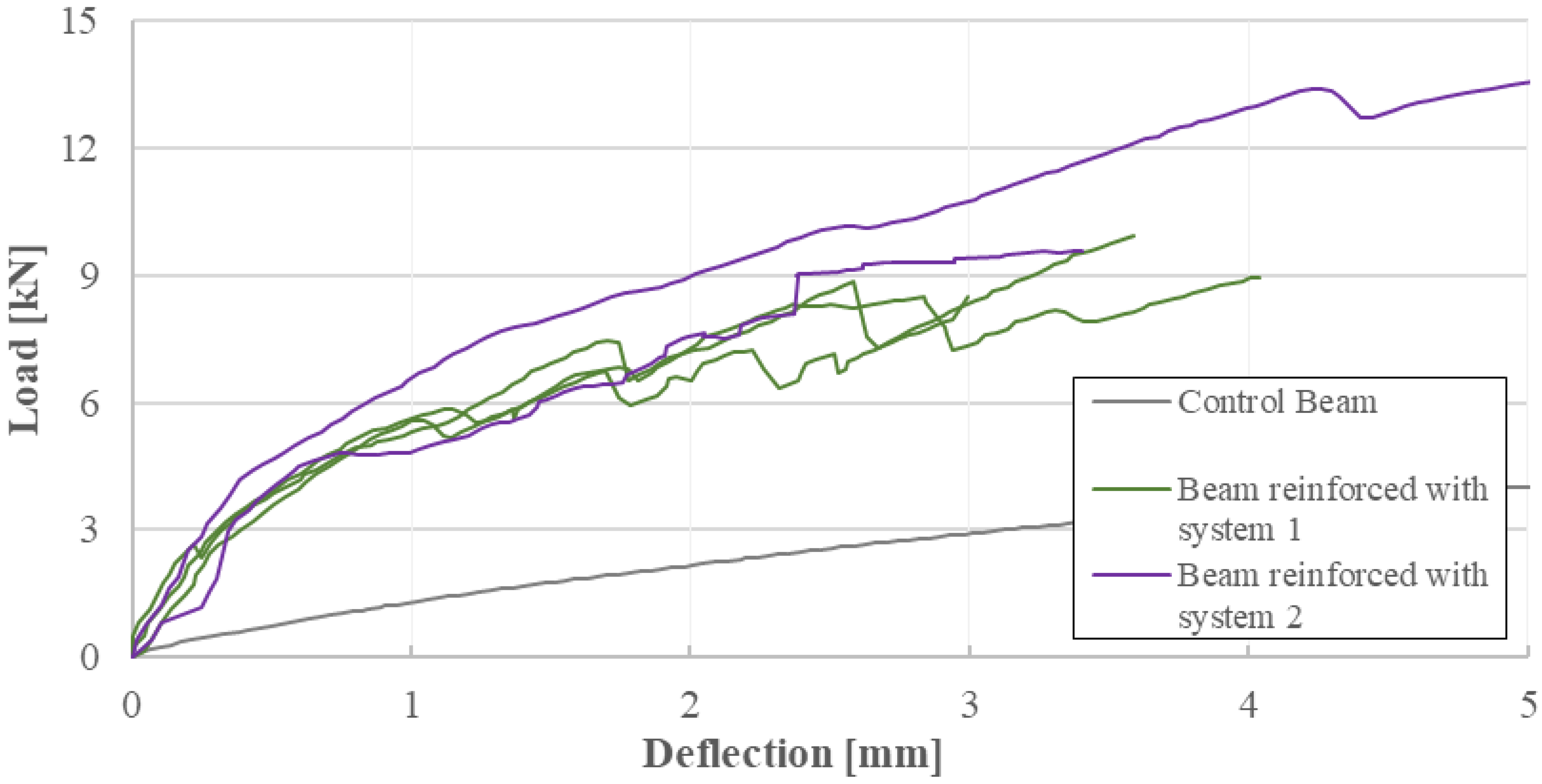

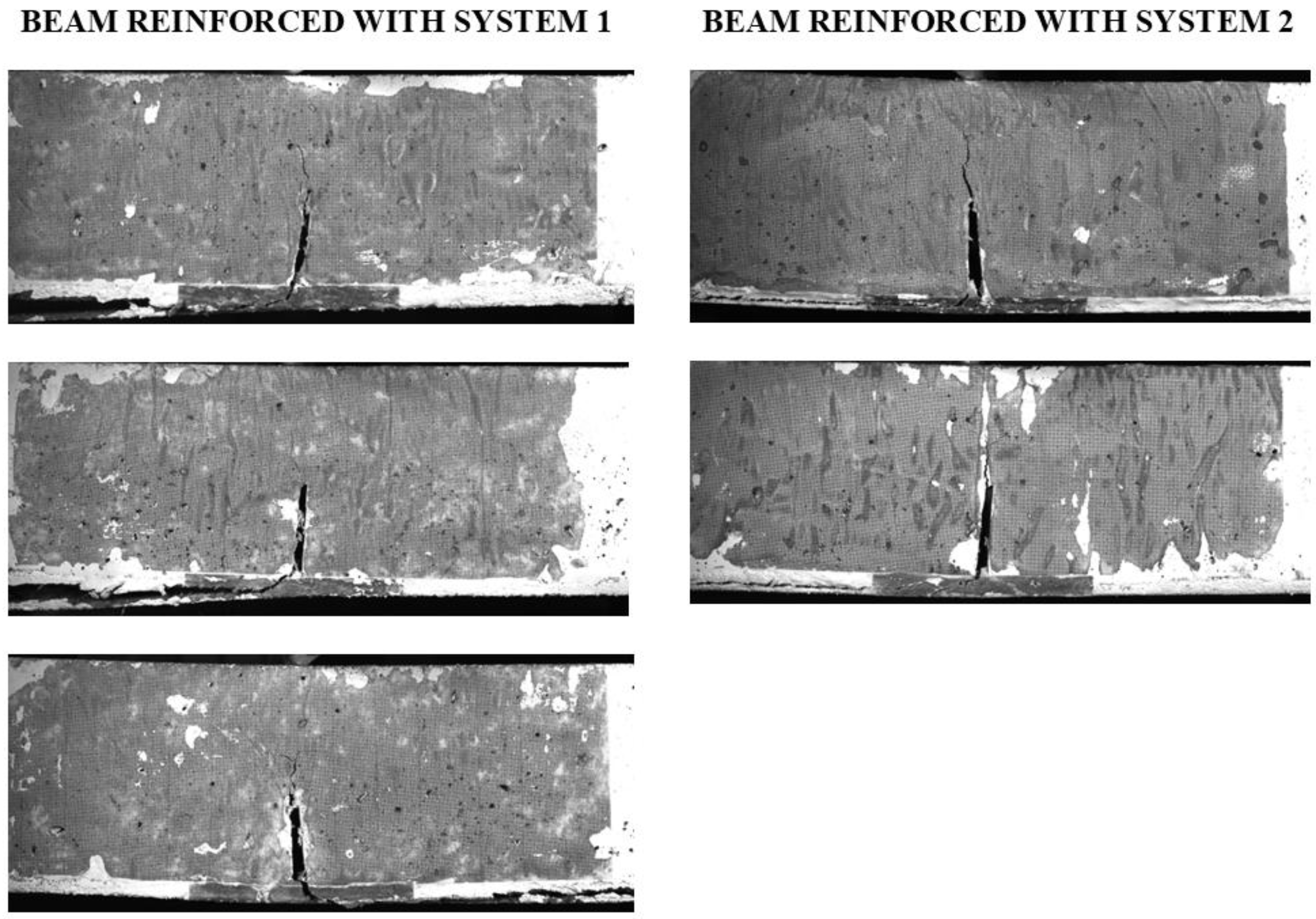

2.4. Main Results

3. Modelling of the FRCM-Reinforced Beams

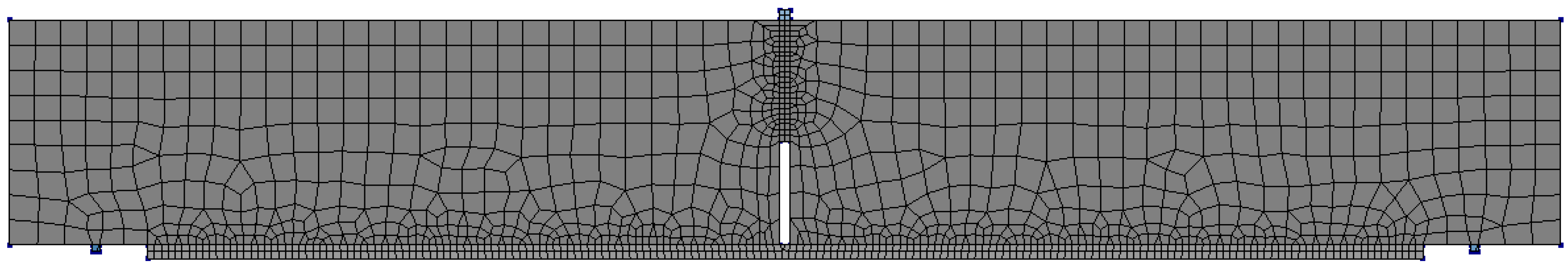

3.1. Element Type and Size

3.2. Boundary Conditions

3.3. Loading Scheme

3.4. Constitutive Material Models

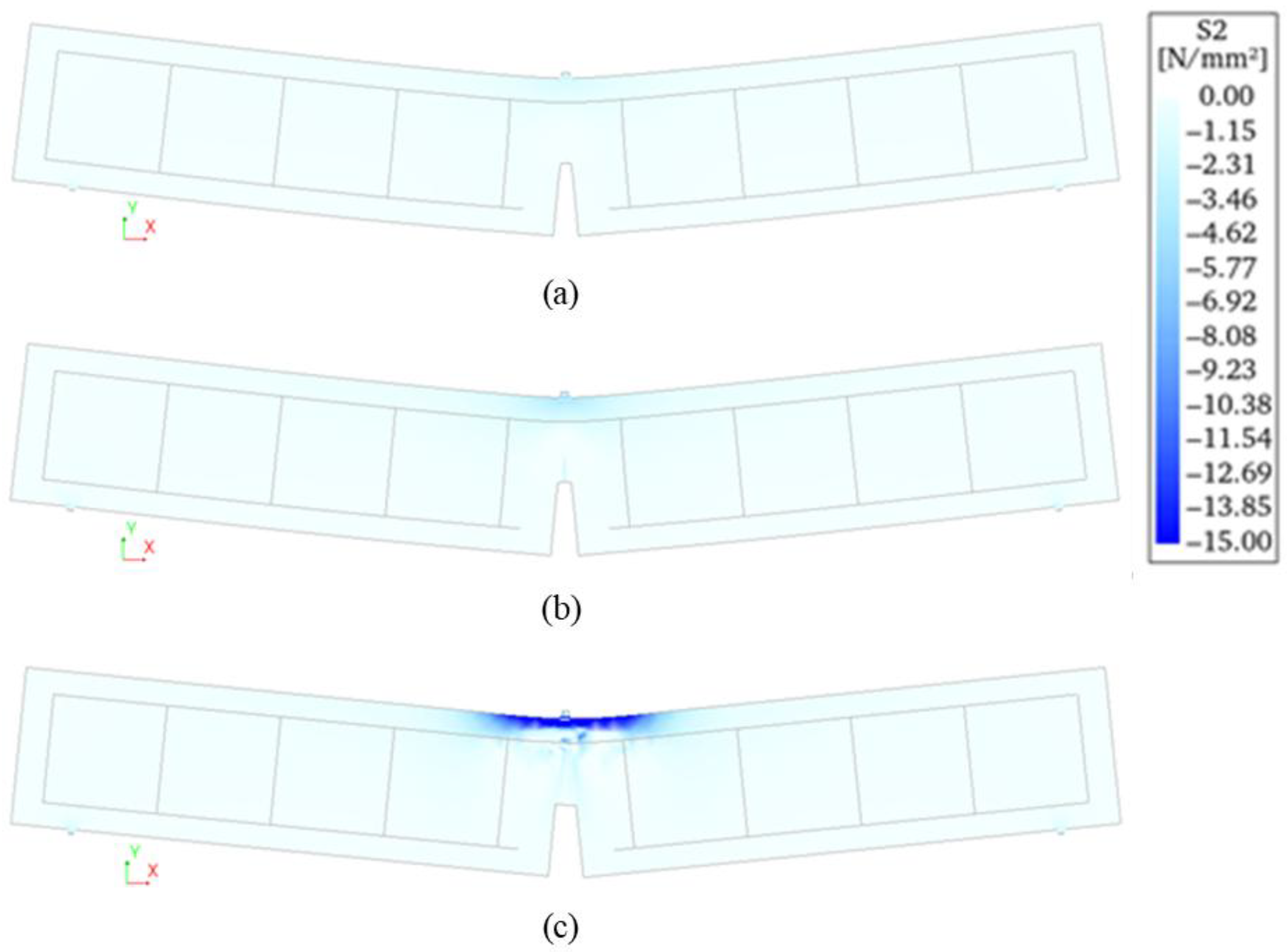

4. Numerical Performance of FRCM-Reinforced Beams

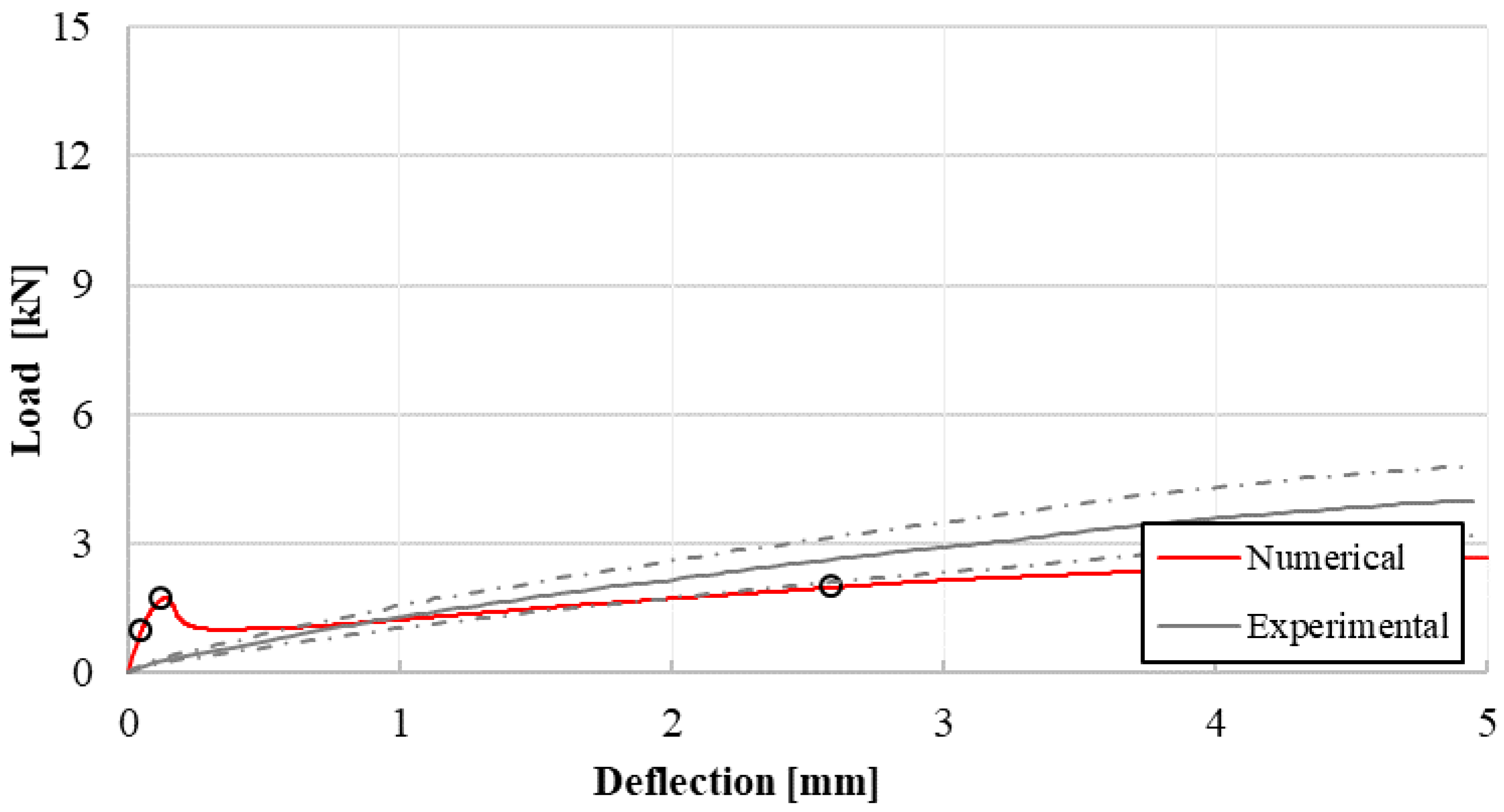

4.1. Reinforced Concrete Beam

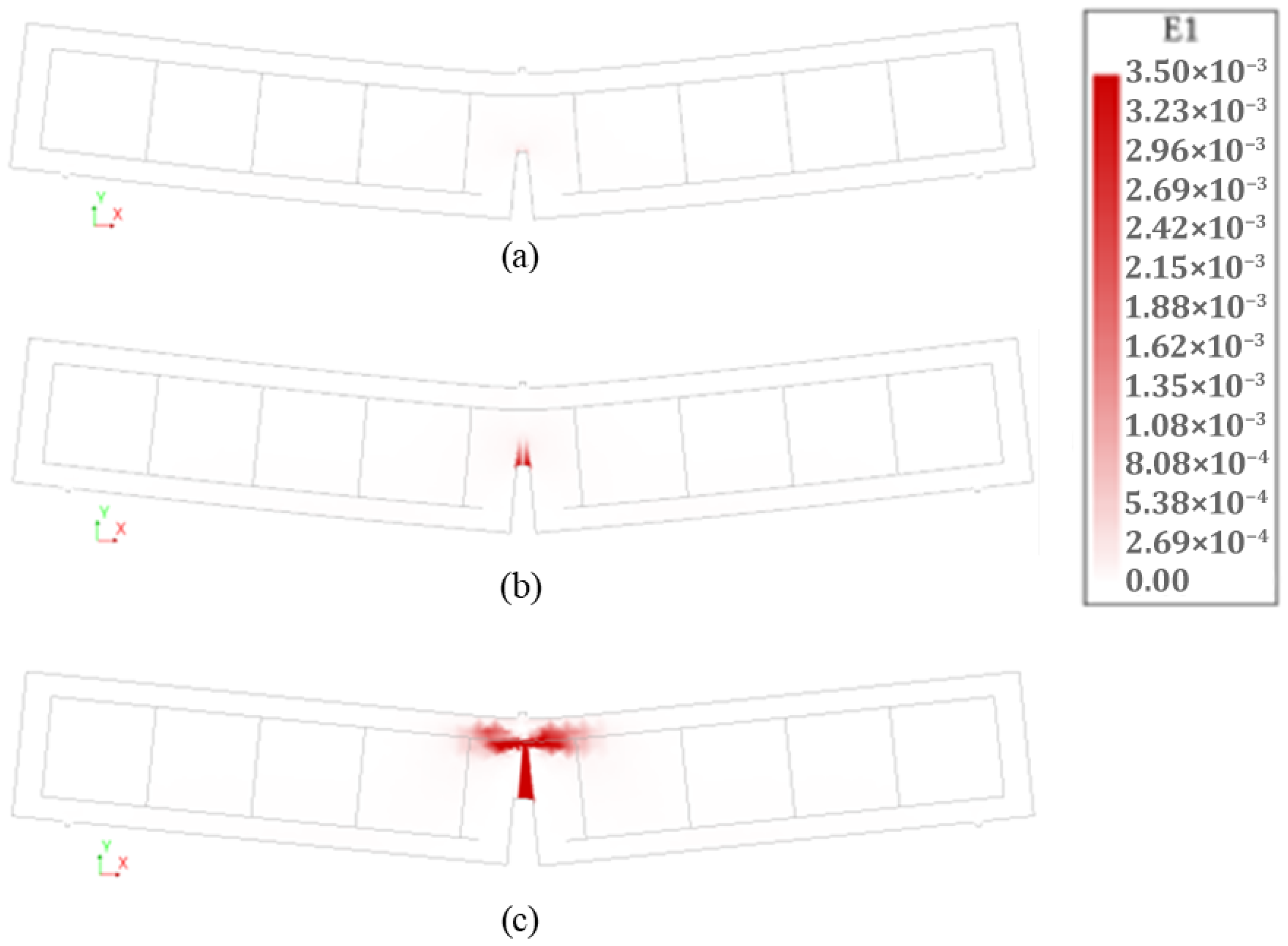

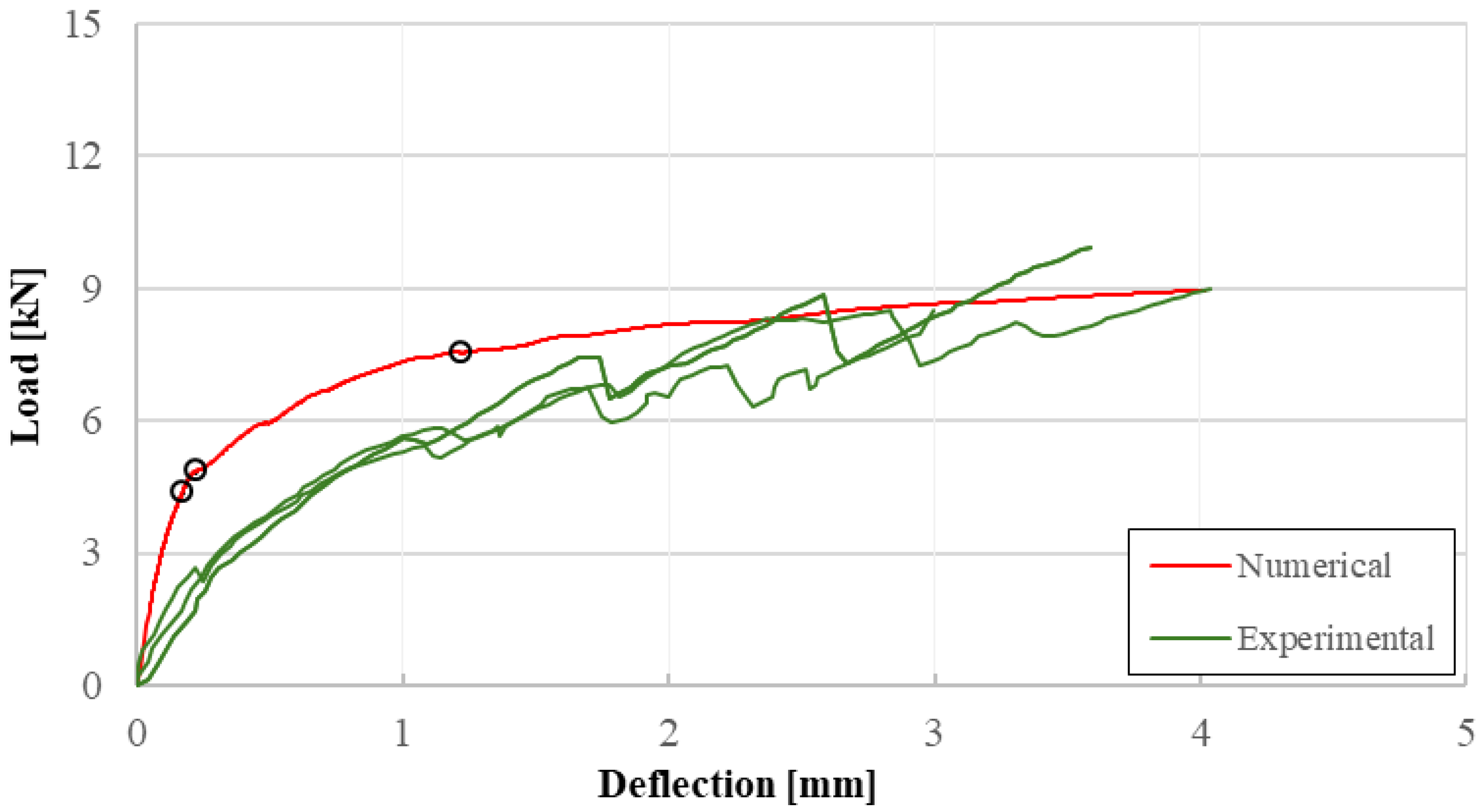

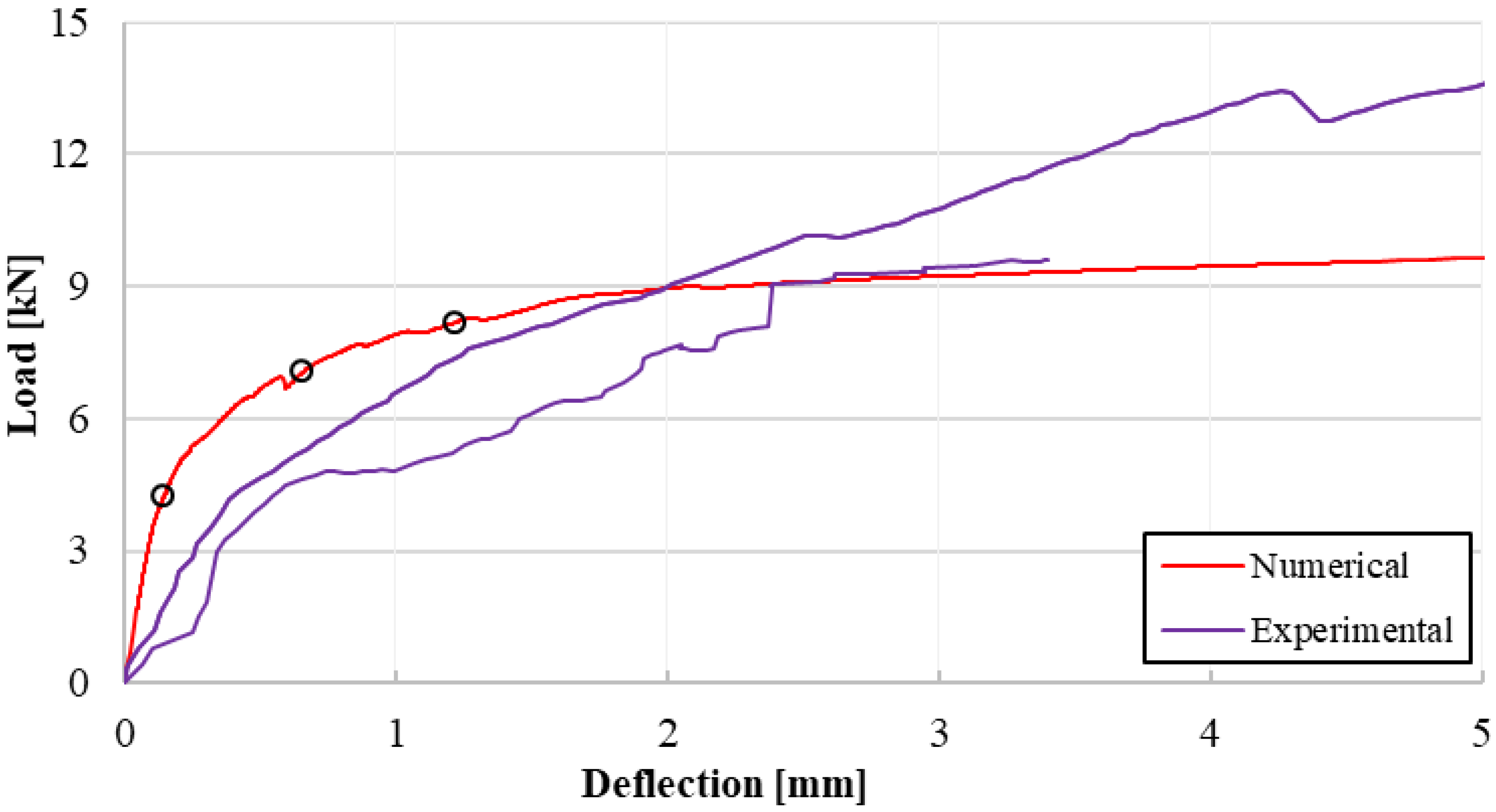

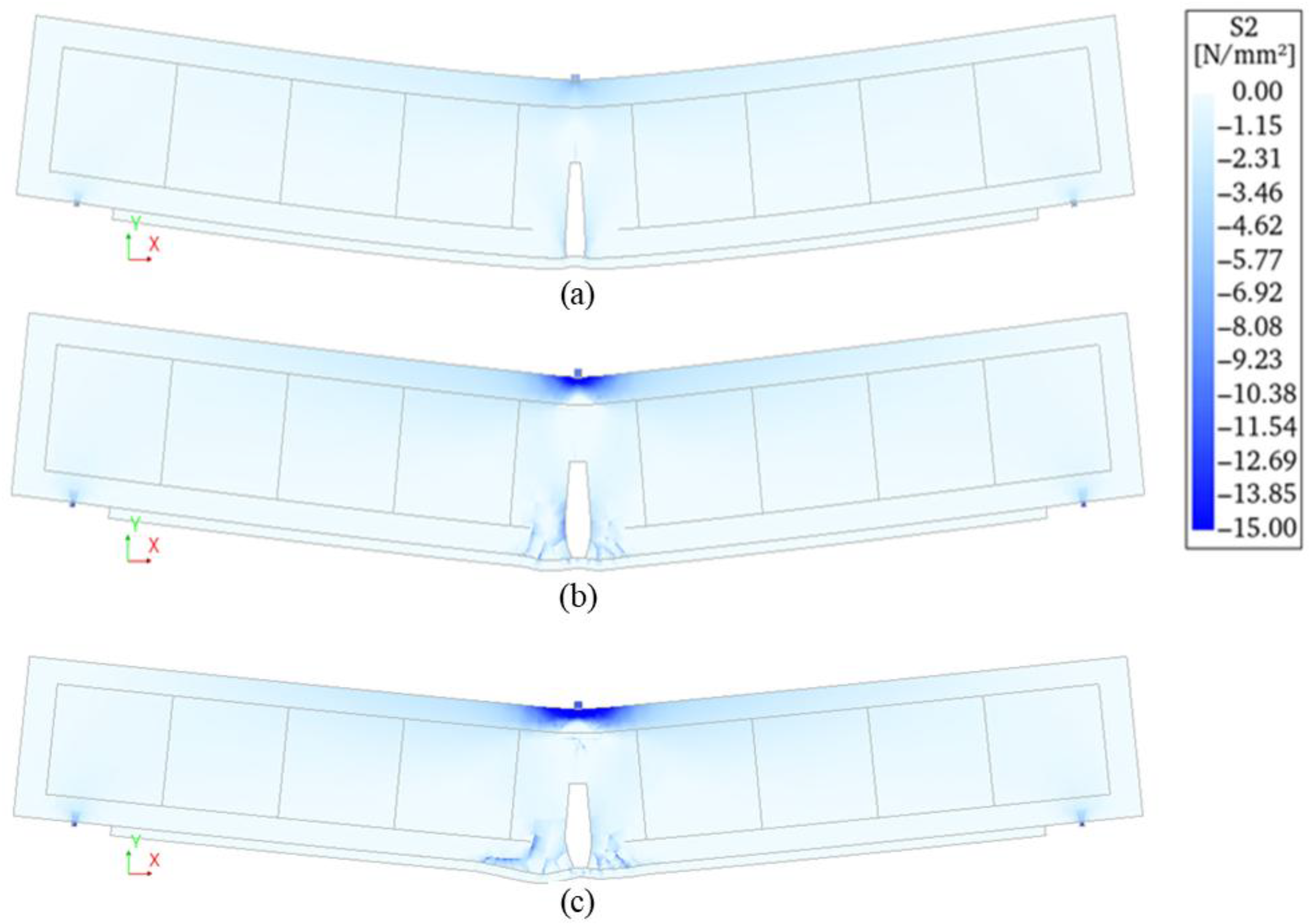

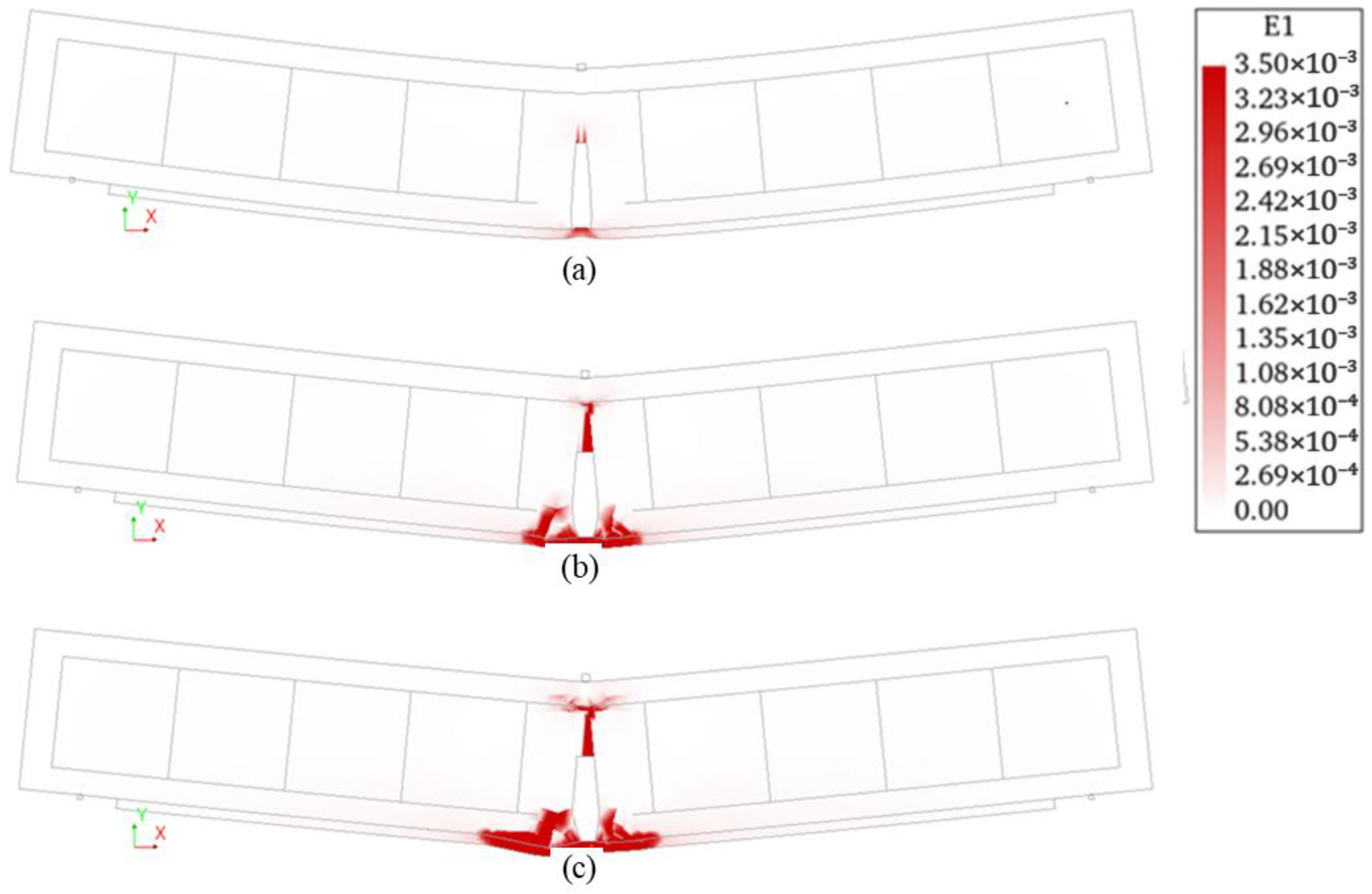

4.2. Reinforced Concrete Beam Retrofitted with FRCM System 1

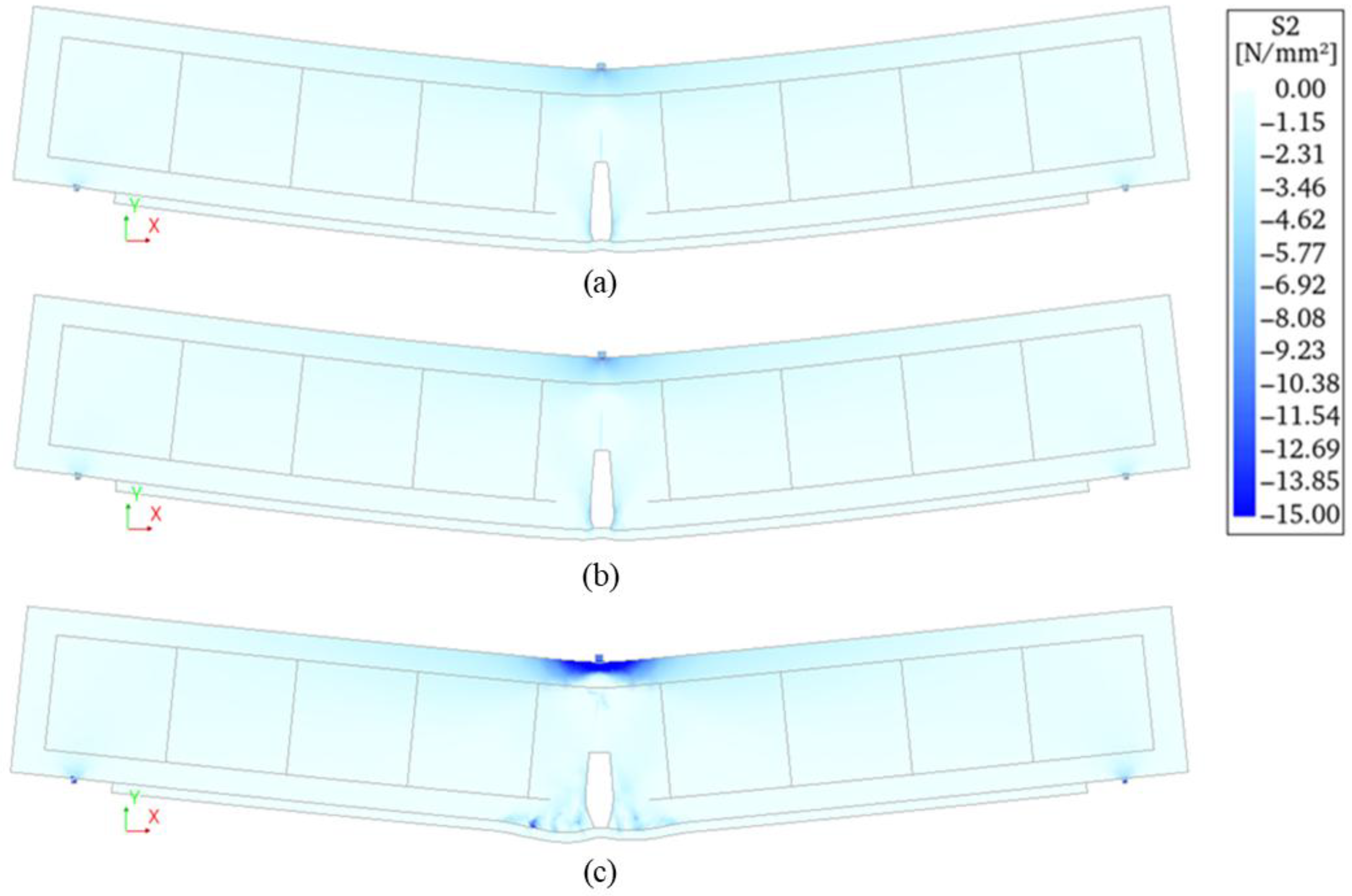

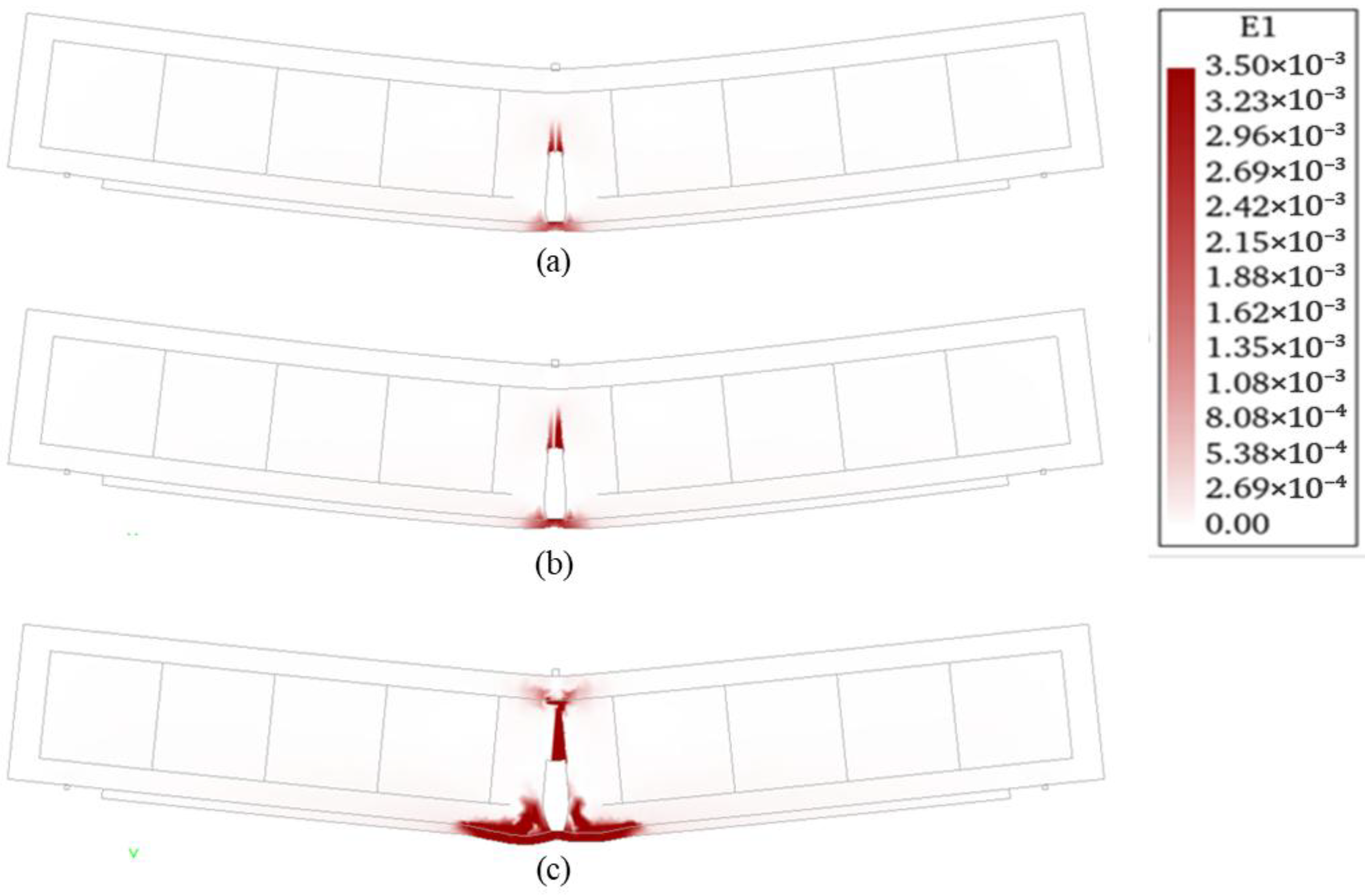

4.3. Reinforced Concrete Beam Retrofitted with FRCM System 2

5. Conclusions

- The adopted macro-modelling approach enables a reliable estimation of the behaviour of concrete beams retrofitted with FRCM systems when the failure initiates within the composite.

- The model demonstrates sufficient accuracy for beam simulation at the ultimate limit state. The material characterisation of FRCM through idealised stress–strain from tensile tests of coupons provide a cost-effective and practical alternative to bending tests on retrofitted beams.

- For the control beam, the load drops when the concrete tensile strength is reached and then it starts to rise slightly. In beams strengthened with FRCM, there is no decrease in load; the stiffness simply decreases. Comparing the two FRCM systems, both show similar load–deflection curve shapes, but beams retrofitted with system 2 support higher loads, which is consistent with tensile test results and experimental results on beams.

- The model achieves a sufficient level of accuracy in simulating the beam behaviour, adequate for engineering applications, relying solely on the constitutive models of concrete and FRCM and assuming a perfect bond between the reinforcement and the substrate.

- The tailored combination of macro-modelling approach, perfect bond assumption between concrete and FRCM, and use of tensile test data for each composite system, significantly reduces computational cost and the need for extensive bending tests.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nunes, V.A.; Borges, P.H.R.; Zanotti, C. Mechanical compatibility and adhesion between alkali-activated repair mortars and Portland cement concrete substrate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 215, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilly, G.; Jacobs, J. Concrete Repairs-Performance in Service and Current Practice; IHS Bre Press: Watford, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-1-86081-974-2. [Google Scholar]

- D’Antino, T.; Carloni, C.; Sneed, L.H.; Pellegrino, C. Matrix-fiber bond behavior in PBO FRCM composites: A fracture mechanics approach. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2014, 117, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carozzi, F.G.; Milani, G.; Poggi, C. Mechanical properties and numerical modeling of Fabric Reinforced Cementitious Matrix (FRCM) systems for strengthening of masonry structures. Compos. Struct. 2014, 107, 711–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arboleda, D.; Carozzi, F.G.; Nanni, A.; Poggi, C. Testing Procedures for the Uniaxial Tensile Characterization of Fabric-Reinforced Cementitious Matrix Composites. J. Compos. Constr. 2016, 20, 04015063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanicolaou, C.G.; Triantafillou, T.C.; Papathanasiou, M.; Karlos, K. Textile reinforced mortar (TRM) versus FRP as strengthening material of URM walls: Out-of-plane cyclic loading. Mater. Struct. Constr. 2008, 41, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Felice, G.; De Santis, S.; Garmendia, L.; Ghiassi, B.; Larrinaga, P.; Lourenço, P.B.; Oliveira, D.V.; Paolacci, F.; Papanicolaou, C.G. Mortar-based systems for externally bonded strengthening of masonry. Mater. Struct. Constr. 2014, 47, 2021–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetta, Z.C.; Bournas, D.A. TRM vs. FRP jacketing in shear strengthening of concrete members subjected to high temperatures. Compos. Part B Eng. 2016, 106, 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valluzzi, M.R.; Modena, C.; de Felice, G. Current practice and open issues in strengthening historical buildings with composites. Mater. Struct. Constr. 2014, 47, 1971–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santis, S.; De Felice, G. Tensile behaviour of mortar-based composites for externally bonded reinforcement systems. Compos. Part B Eng. 2015, 68, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnini, J.; Corinaldesi, V.; Nanni, A. Mechanical properties of FRCM using carbon fabrics with different coating treatments. Compos. Part B Eng. 2016, 88, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, S.; Abed, F.; El, A.; Alhoubi, Y.; Ramzi, S.; Hajiloo, H. PBO-FRCM and CFRP strengthened reinforced concrete columns: In fire and post-fire behavior. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 489, 142306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ombres, L.; Mazzuca, P.; Ph, D.; Micieli, A.; Candamano, S.; Campolongo, F. FRCM–Masonry Joints at High Temperature: Residual Bond Capacity. J. Mater. Civil Eng. 2025, 37, 04025012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantafillou, T.C.; Papanicolaou, C.G. Textile reinforced mortars (TRM) versus fiber reinforced polymers (FRP) as strengthening materials of concrete structures. In Proceedings of the American Concrete Institute; ACI Special Publication: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2005; Volume SP-230, pp. 99–117. [Google Scholar]

- Lignola, G.P.; Caggegi, C.; Ceroni, F.; De Santis, S.; Krajewski, P.; Lourenço, P.B.; Morganti, M.; Papanicolaou, C.; Pellegrino, C.; Prota, A.; et al. Performance assessment of basalt FRCM for retrofit applications on masonry. Compos. Part B Eng. 2017, 128, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caggegi, C.; Carozzi, F.G.; De Santis, S.; Fabbrocino, F.; Focacci, F.; Hojdys, Ł.; Lanoye, E.; Zuccarino, L. Experimental analysis on tensile and bond properties of PBO and aramid fabric reinforced cementitious matrix for strengthening masonry structures. Compos. Part B Eng. 2017, 127, 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caggegi, C.; Lanoye, E.; Djama, K.; Bassil, A.; Gabor, A. Tensile behaviour of a basalt TRM strengthening system: Influence of mortar and reinforcing textile ratios. Compos. Part B Eng. 2017, 130, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilotta, A.; Ceroni, F.; Lignola, G.P.; Prota, A. Use of DIC technique for investigating the behaviour of FRCM materials for strengthening masonry elements. Compos. Part B Eng. 2017, 129, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Felice, G.; D’Antino, T.; De Santis, S.; Meriggi, P.; Roscini, F. Lessons Learned on the Tensile and Bond Behavior of Fabric Reinforced Cementitious Matrix (FRCM) Composites. Front. Built Environ. 2020, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, M.; Aiello, M.A.; Balsamo, A.; Carozzi, F.G.; Ceroni, F.; Corradi, M.; Gams, M.; Garbin, E.; Gattesco, N.; Krajewski, P.; et al. Glass fabric reinforced cementitious matrix: Tensile properties and bond performance on masonry substrate. Compos. Part B Eng. 2017, 127, 196–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carozzi, F.G.; Bellini, A.; D’Antino, T.; de Felice, G.; Focacci, F.; Hojdys, Ł.; Laghi, L.; Lanoye, E.; Micelli, F.; Panizza, M.; et al. Experimental investigation of tensile and bond properties of Carbon-FRCM composites for strengthening masonry elements. Compos. Part B Eng. 2017, 128, 100–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascione, L.; de Felice, G.; De Santis, S. A qualification method for externally bonded Fibre Reinforced Cementitious Matrix (FRCM) strengthening systems. Compos. Part B Eng. 2015, 78, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellini, A.; Bovo, M.; Mazzotti, C. Experimental and numerical evaluation of fiber-matrix interface behaviour of different FRCM systems. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 161, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Vachirapanyakun, S.; Ochirbud, M.; Naidangjav, U.; Ha, S.; Kim, Y. Tensile Performance, Lap-Splice Length and Behavior of Concretes Confined by Prefabricated C-FRCM System. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2021, 15, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CNR-DT 215/2018; Guide for the Design and Construction of Externally Bonded Fibre Reinforced Inorganic Matrix Systems for Strengthening Existing Structures. Italian National Research Council: Rome, Italy, 2018; p. 144.

- Rodríguez-Marcos, M.; Villanueva-Llaurado, P.; Fernández-Gómez, J.; López–Rebollo, J. Improvement of tensile properties of carbon fibre-reinforced cementitious matrix composites with coated textile and enhanced mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 369, 130552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Antino, T.; Papanicolaou, C. Comparison between different tensile test set-ups for the mechanical characterization of inorganic-matrix composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 171, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, V.D.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, D.J. Effects of different grips and surface treatments of textile on measured direct tensile response of textile reinforced cementitious composites. Compos. Struct. 2021, 278, 114689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, A.; Ebead, U.; Shrestha, K. Tensile characterization of multi-ply fabric-reinforced cementitious matrix strengthening systems. Struct. Concr. 2020, 21, 713–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AC434; Acceptance Criteria for Concrete and Masonry Strengthening Using Fabric-Reinforced Cementitious Matrix (FRCM). ICC Evaluation Service, LLC: Whittier, CA, USA, 2018.

- Su, M.N.; Wang, Z.; Ueda, T. Optimization and design of carbon fabric-reinforced cementitious matrix composites. Struct. Concr. 2022, 23, 1845–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams Portal, N.; Flansbjer, M.; Johannesson, P.; Malaga, K.; Lundgren, K. Tensile behaviour of textile reinforcement under accelerated ageing conditions. J. Build. Eng. 2016, 5, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Domenico, D.; Maugeri, N.; Longo, P.; Ricciardi, G.; Gullì, G.; Calabrese, L. Clevis-Grip Tensile Tests on Basalt, Carbon and Steel FRCM Systems Realized with Customized Cement-Based Matrices. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACI 549.4R-20; Guide to Design and Construction of Externally Bonded Fabric-Reinforced Cementitious Matrix and Steel-Reinforced Grout Systems for Repair and Strengthening of Concrete Structures. ACI Committee 549: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2020; p. 36.

- ACI 549.6R-20; Guide to Design and Construction of Externally Bonded Fabric-Reinforced Cementitious Matrix (FRCM) and Steel-Reinforced Grout (SRG) Systems for Repair and Strengthening Masonry Structures. ACI Committee 549: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2012; p. 162.

- Calabrese, A.S.; D’Antino, T.; Colombi, P. Experimental and analytical investigation of PBO FRCM-concrete bond behavior using direct and indirect shear test set-ups. Compos. Struct. 2021, 267, 113672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Antino, T.; Focacci, F.; Sneed, L.H.; Carloni, C. Relationship between the effective strain of PBO FRCM-strengthened RC beams and the debonding strain of direct shear tests. Eng. Struct. 2020, 216, 110631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elghazy, M.; El Refai, A.; Ebead, U.; Nanni, A. Effect of corrosion damage on the flexural performance of RC beams strengthened with FRCM composites. Compos. Struct. 2017, 180, 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Antino, T.; Colombi, P.; Carloni, C.; Sneed, L.H. Estimation of a matrix-fiber interface cohesive material law in FRCM-concrete joints. Compos. Struct. 2018, 193, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wozniak, M.; Tysmans, T.; Vantomme, J.; De Sutter, S. Experimental bond behaviour between Textile Reinforced Cement and Concrete. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Construction Materials and Structures-ICCMATS-1, Johannesburg, South Africa, 24–26 November 2014; Ekolu, S.O., Dundu, M., Gao, X., Eds.; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 932–939. [Google Scholar]

- Ebead, U.; Shrestha, K.C.; Afzal, M.S.; El Refai, A.; Nanni, A. Effectiveness of Fabric-Reinforced Cementitious Matrix in Strengthening Reinforced Concrete Beams. J. Compos. Constr. 2017, 21, 04016084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elghazy, M.; El Refai, A.; Ebead, U.; Nanni, A. Corrosion-Damaged RC Beams Repaired with Fabric-Reinforced Cementitious Matrix. J. Compos. Constr. 2018, 22, 04018039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabr, A.; El-Ragaby, A.; Ghrib, F. Effect of the Fiber Type and Axial Stiffness of FRCM on the Flexural Strengthening of RC Beams. Fibers 2017, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoof, S.M.; Bournas, D.A. TRM versus FRP in flexural strengthening of RC beams: Behaviour at high temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 154, 424–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoof, S.M.; Koutas, L.N.; Bournas, D.A. Textile-reinforced mortar (TRM) versus fibre-reinforced polymers (FRP) in flexural strengthening of RC beams. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 151, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Antino, T.; Papanicolaou, C. Mechanical characterization of textile reinforced inorganic-matrix composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2017, 127, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencardino, F.; Carloni, C.; Condello, A.; Focacci, F.; Napoli, A.; Realfonzo, R. Flexural behaviour of RC members strengthened with FRCM: State-of-the-art and predictive formulas. Compos. Part B Eng. 2018, 148, 132–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peled, A.; Bentur, A. Geometrical characteristics and efficiency of textile fabrics for reinforcing cement composites. Cem. Concr. Res. 2000, 30, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awani, O.; El-Maaddawy, T.; Ismail, N. Fabric-reinforced cementitious matrix: A promising strengthening technique for concrete structures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 132, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Marcos, M.; Villanueva-Llaurado, P.; Fernández-Gómez, J.; López-Rebollo, J. Effectiveness of coated carbon fibre cementitious matrix systems for flexural strengthening of concrete beams. Eng. Struct. 2025, 325, 119443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Focacci, F.; D’Antino, T.; Carloni, C. Tensile Testing of FRCM Coupons for Material Characterization: Discussion of Critical Aspects. J. Compos. Constr. 2022, 26, 04022039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, E.; Milani, G. Procedure for the numerical characterization of the local bond behavior of FRCM. Compos. Struct. 2021, 258, 113404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgo, F.S.; Ferretti, F.; Mazzotti, C. A Discrete-Cracking Numerical Model for the in-Plane Behavior of FRCM Strengthened Masonry Panels; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 19, ISBN 0123456789. [Google Scholar]

- Awani, O.; El Refai, A.; El-Maaddawy, T. Bond characteristics of carbon fabric-reinforced cementitious matrix in double shear tests. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 101, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askouni, P.D.; Papanicolaou, C.G. Experimental investigation of bond between glass textile reinforced mortar overlays and masonry: The effect of bond length. Mater. Struct. Constr. 2017, 50, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ambrisi, A.; Feo, L.; Focacci, F. Experimental and analytical investigation on bond between Carbon-FRCM materials and masonry. Compos. Part B Eng. 2013, 46, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsamak, G.; Ghalla, M.; El-Naqeeb, M.H.; Iskander, Y.; Bazuhair, R.W.; Yehia, S.A. Assessment of FRCM jacket configurations for enhancing shear strength of deficient RC beams. Structures 2025, 80, 109846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabzi, J.; Asadi Shamsabadi, E.; Esfahani, M.R.; Ozbakkaloglu, T. A study on reinforced concrete beams strengthened with FRP and FRCM. Eng. Struct. 2025, 329, 119687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elghazy, M.; El Refai, A.; Ebead, U.; Nanni, A. Post-repair flexural performance of corrosion-damaged beams rehabilitated with fabric-reinforced cementitious matrix (FRCM). Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 166, 732–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, E.; Randl, N.; Harsányi, P.; Mészöly, T. Experimental study of fibre-reinforced TRC shear strengthening applications on non-stirrup reinforced concrete T-beams. Eng. Struct. 2022, 256, 113923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro Silva, R.M.; Silva, F.d.A. Flexural strengthening efficiency of small-scale RC beams using textile reinforced concrete (TRC) with mineral-impregnated carbon fabrics. Structures 2025, 77, 109056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolesi, E.; Carozzi, F.G.; Milani, G.; Poggi, C. Numerical modeling of Fabric Reinforce Cementitious Matrix composites (FRCM) in tension. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 70, 531–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urso, S.; Hadad, H.A.; Borsellino, C.; Recupero, A.; Yang, Q.D.; Nanni, A. Numerical Modelling of FRCM Materials Using Augmented-FEM. Key Eng. Mater. 2019, 817, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaco, A.; D’anna, J.; Oddo, M.C.; Minafò, G.; La Mendola, L. Numerical modelling of the tensile behaviour of BFRCM strips. Key Eng. Mater. 2019, 817, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaco, A.; Minafò, G.; D’Anna, J.; Oddo, M.C.; La Mendola, L. Constitutive Numerical Model of FRCM Strips Under Traction. Front. Built. Environ. 2020, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddo, M.C.; Minafó, G.; Di Leto, M.; La Mendola, L. Numerical Modelling of the Constitutive Behaviour of FRCM Composites through the Use of Truss Elements. Materials 2023, 16, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minafò, G.; Oddo, M.C.; Camarda, G.; Leto, M.D.; La Mendola, L. Effect of interface model parameters on the numerical response of a FE model for predicting the FRCM-to-masonry bond. Acta Mech. 2024, 235, 1669–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minafò, G.; Di Leto, M.; Camarda, G.; La Mendola, L. A GA-based model updating procedure for the numerical simulation of FRCM-to-masonry bond. Eng. Struct. 2024, 303, 117512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljazaeri, Z.R.; Al-Jaberi, Z. Numerical study on flexural behavior of concrete beams strengthened with fiber reinforced cementitious matrix considering different concrete compressive strength and steel reinforcement ratio. Int. J. Eng. Trans. A Basics 2021, 34, 796–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lignola, G.P.; Bilotta, A.; Ceroni, F. Assessment of the effect of FRCM materials on the behaviour of masonry walls by means of FE models. Eng. Struct. 2019, 184, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsanadedy, H.M.; Almusallam, T.H.; Alsayed, S.H.; Al-Salloum, Y.A. Flexural strengthening of RC beams using textile reinforced mortar-Experimental and numerical study. Compos. Struct. 2013, 97, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercedes, L.; Escrig, C.; Bernat-Masó, E.; Gil, L. Analytical approach and numerical simulation of reinforced concrete beams strengthened with different frcm systems. Materials 2021, 14, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, R.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Zhu, J.-H. Interface behaviour of carbon-fabric-reinforced cementitious matrix composites with ICCP technique. Mag. Concr. Res. 2022, 74, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattak, N.; Mansour, M.; El-Maaddawy, T.; Ismail, N. Continuous Reinforced Concrete Beams Strengthened with Fabric-Reinforced Cementitious Matrix: Experimental Investigation and Numerical Simulation. Buildings 2021, 12, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sika. Product Data Sheet Sika CarboDur ® -300 Grid 2020. Available online: https://can.sika.com/dms/getdocument.get/34061b19-4c8c-42cc-84ba-af5ab0540ef8/sika-carbodur-300grid.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2025).

- UNE-EN 197-1:2011; Cemento. Parte 1: Composición, Especificaciones y Criterios de Conformidad de los Cementos Comunes. AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 2011.

- UNE-EN 1504-3:2006; Productos y Sistemas Para la Protección y Reparación de Estructuras de Hormigón. Definiciones, Requisitos, Control de Calidad y Evaluación de la Conformidad. Parte 3: Reparación estructural y no Estructural. AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 2006.

- EN 12190; Products and Systems for the Protection and Repair of Concrete Structures–Test Methods–Determination of Compressive Strength of Repair Mortar. EN: Brussels, Belgium, 1999; p. 8.

- EN 13412; Products and Systems for the Protection and Repair of Concrete Structures. Test Methods. Determination of Modulus of Elasticity in Compression. EN: Brussels, Belgium, 2008; p. 9.

- UNE-EN12390-3:2020; Testing Hardened Concrete-Part 3: Compressive Strength of Test Specimens. AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 2020.

- Almeida, J.A.P.P.; Pereira, E.B.; Barros, J.A.O. Numerical modelling of failure on brick masonry strengthened with FRCM overlays. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019; Volume 596, p. 012026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contamine, R.; Si Larbi, A.; Hamelin, P. Contribution to direct tensile testing of textile reinforced concrete (TRC) composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2011, 528, 8589–8598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobasher, B.; Peled, A.; Pahilajani, J. Distributed cracking and stiffness degradation in fabric-cement composites. Mater. Struct. Constr. 2006, 39, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raupach, M.; Orlowsky, J.; Büttner, T.; Dilthey, U.; Scheleser, M. Epoxy-impregnated textiles in concrete—Load bearing capacity and durability. In Proceedings of the Internacional Conference Textile Reinforced Concrete; RILEM Publications SARL: Paris, France, 2006; pp. 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Singla, N. Experimental and Theoritical Study of Fabric Cement Composites for Retrofitting Masonry Structures. Ph. D. Thesis, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mininno, G.; Ghiassi, B.; Oliveira, D.V. Modelling of the in-plane and out-of-plane performance of TRM-strengthened masonry walls. Key Eng. Mater. 2017, 747, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.V.; Ghiassi, B.; Allahvirdizadeh, R.; Wang, X.; Mininno, G.; Silva, R.A. Macromodeling approach for pushover analysis of textile-reinforced mortar-strengthened masonry. In Numerical Modeling of Masonry and Historical Structures; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2019; pp. 745–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, A.; Fraddosio, A.; Oliveira, D.V.; Piccioni, M.D.; Ricci, E.; Sacco, E. An effective numerical modelling strategy for FRCM strengthened curved masonry structures. Eng. Struct. 2023, 274, 115116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, J.; Jesse, F.; Schicktanz, K.; Häußler-Combe, U. Influence of experimental setups on the apparent uniaxial tensile load-bearing capacity of Textile Reinforced Concrete specimens. Mater. Struct. Constr. 2012, 45, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, V.D.; Kim, D.J. A review paper on direct tensile behavior and test methods of textile reinforced cementitious composites. Compos. Struct. 2021, 263, 113661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Peled, A.; Mobasher, B. Dynamic tensile testing of fabric-cement composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santis, S.; Carozzi, F.G.; de Felice, G.; Poggi, C. Test methods for Textile Reinforced Mortar systems. Compos. Part B Eng. 2017, 127, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Felice, G.; Aiello, M.A.; Caggegi, C.; Ceroni, F.; De Santis, S.; Garbin, E.; Gattesco, N.; Hojdys, Ł.; Krajewski, P.; Kwiecień, A.; et al. Recommendation of RILEM Technical Committee 250-CSM: Test method for Textile Reinforced Mortar to substrate bond characterization. Mater. Struct. Constr. 2018, 51, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Li, Y.; Zhu, J.-H. Numerical study and seismic design of corroded circular RC columns strengthened by C-FRCM. Mag. Concr. Res. 2022, 74, 1065–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carozzi, F.G.; Poggi, C. Mechanical properties and debonding strength of Fabric Reinforced Cementitious Matrix (FRCM) systems for masonry strengthening. Compos. Part B Eng. 2015, 70, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreier, H.; Orteu, J.-J.; Sutton, M.A. Image Correlation for Shape, Motion and Deformation Measurements; Springer US: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-387-78746-6. [Google Scholar]

- García-Martin, R.; López-Rebollo, J.; Sánchez-Aparicio, L.J.; Fueyo, J.G.; Pisonero, J.; González-Aguilera, D. Digital image correlation and reliability-based methods for the design and repair of pressure pipes through composite solutions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 248, 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teijón-López-zuazo, E.; López-Rebollo, J.; Sánchez-Aparicio, L.J.; Garcia-Martín, R.; Gonzalez-Aguilera, D. Compression and strain predictive models in non-structural recycled concretes made from construction and demolition wastes. Materials 2021, 14, 3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.; Villanueva, P.; Fernández, J. FRCM Composites para aplicaciones estructurales: Una revisión sistemática FRCM Composites for structural applications: A systematic review. An. Edif. 2024, 10, 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- López-Rebollo, J.; Cárdenas-Haro, X.; Parra-Vargas, J.P.; Narváez-Berrezueta, K.; Pino, J. Improvement of Mechanical Properties of Compressed Earth Blocks with Stabilising Additives for Self-Build of Sustainable Housing. Buildings 2024, 14, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Marcos, M.; Villanueva-Llaurado, P.; Fernández-Gómez, J.; Abellán-García, J.; Sisa-Camargo, A. Predicting the Tensile Properties of Carbon FRCM Using a LASSO Model. Fibers 2024, 12, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S. Comparison of Nonlinear Finite Element Modeling Tools for Structural Concrete. Ph. D. Thesis, University of Illinois Urbana–Champaign, Champaign, IL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, C.T.; Pham, M.; Dinh, N.H. Sensitivity analysis of parameters affecting the seismic performance of RC columns strengthened by fabric-reinforced cementitious mortar. Mater. Res. Express 2024, 11, 055602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, S. Finite Element Analysis for Civil Engineering with DIANA Software; Springer: Singapore, 2020; ISBN 978-981-15-2944-3. [Google Scholar]

- FIB. FIB Model Code for Concrete Structures 2010; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; ISBN 9783433030615. [Google Scholar]

| Mortar | M1 (Conventional) | M2 (Repair) |

|---|---|---|

| fm,c [MPa] | 41.2 | 51.9 |

| fm,f [MPa] | 7.2 | 10.0 |

| Em [GPa] | 15.0 | 20.0 |

| System | Stage | fFRCM | εFRCM | EFRCM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (MPa) | (%) | (GPa) | ||

| System 1 Mortar M1 | A | 2.47 | 0.03 | 8724 |

| B | 12.62 | 0.77 | 1363 | |

| C, ultimate | ||||

| System 2 Mortar M2 | A | 5.35 | 0.05 | 11,321 |

| B | 6.10 | 0.24 | 389 | |

| C, ultimate | 13.20 | 0.67 | 1650 |

| Beam | Load Pu | Deflection | Stress Max FRCM | Peak Strain FRCM | Load Increment | Failure Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (kN) | (mm) | (MPa) | (%) | (%) | ||

| Control beam | 4.53 | 5.13 | - | - | - | - |

| Reinforcement with system 1 | 9.17 ± 0.55 | 3.49 ± 0.50 | 15.04 ± 0.91 | 1.71 ± 0.05 | 203 ± 12 | Debonding at the matrix-to-textile interface |

| Reinforcement with system 2 | 12.19 ± 2.58 | 4.17 ± 0.89 | 19.97 ± 4.21 | 1.51 ± 0.93 | 269 ± 57 | Debonding at the matrix-to-textile interface |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rodríguez-Marcos, M.; Villanueva-Llaurado, P.; Fernández-Gómez, J.; Oliveira, D.V. Numerical Modelling and Experimental Validation of FRCM-Reinforced Concrete Beams Using Macro-Modelling Techniques. Buildings 2026, 16, 551. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030551

Rodríguez-Marcos M, Villanueva-Llaurado P, Fernández-Gómez J, Oliveira DV. Numerical Modelling and Experimental Validation of FRCM-Reinforced Concrete Beams Using Macro-Modelling Techniques. Buildings. 2026; 16(3):551. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030551

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodríguez-Marcos, María, Paula Villanueva-Llaurado, Jaime Fernández-Gómez, and Daniel V. Oliveira. 2026. "Numerical Modelling and Experimental Validation of FRCM-Reinforced Concrete Beams Using Macro-Modelling Techniques" Buildings 16, no. 3: 551. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030551

APA StyleRodríguez-Marcos, M., Villanueva-Llaurado, P., Fernández-Gómez, J., & Oliveira, D. V. (2026). Numerical Modelling and Experimental Validation of FRCM-Reinforced Concrete Beams Using Macro-Modelling Techniques. Buildings, 16(3), 551. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030551