Model Test Study on Group Under-Reamed Anchors Under Cyclic Loading

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Model Test System for Anchors

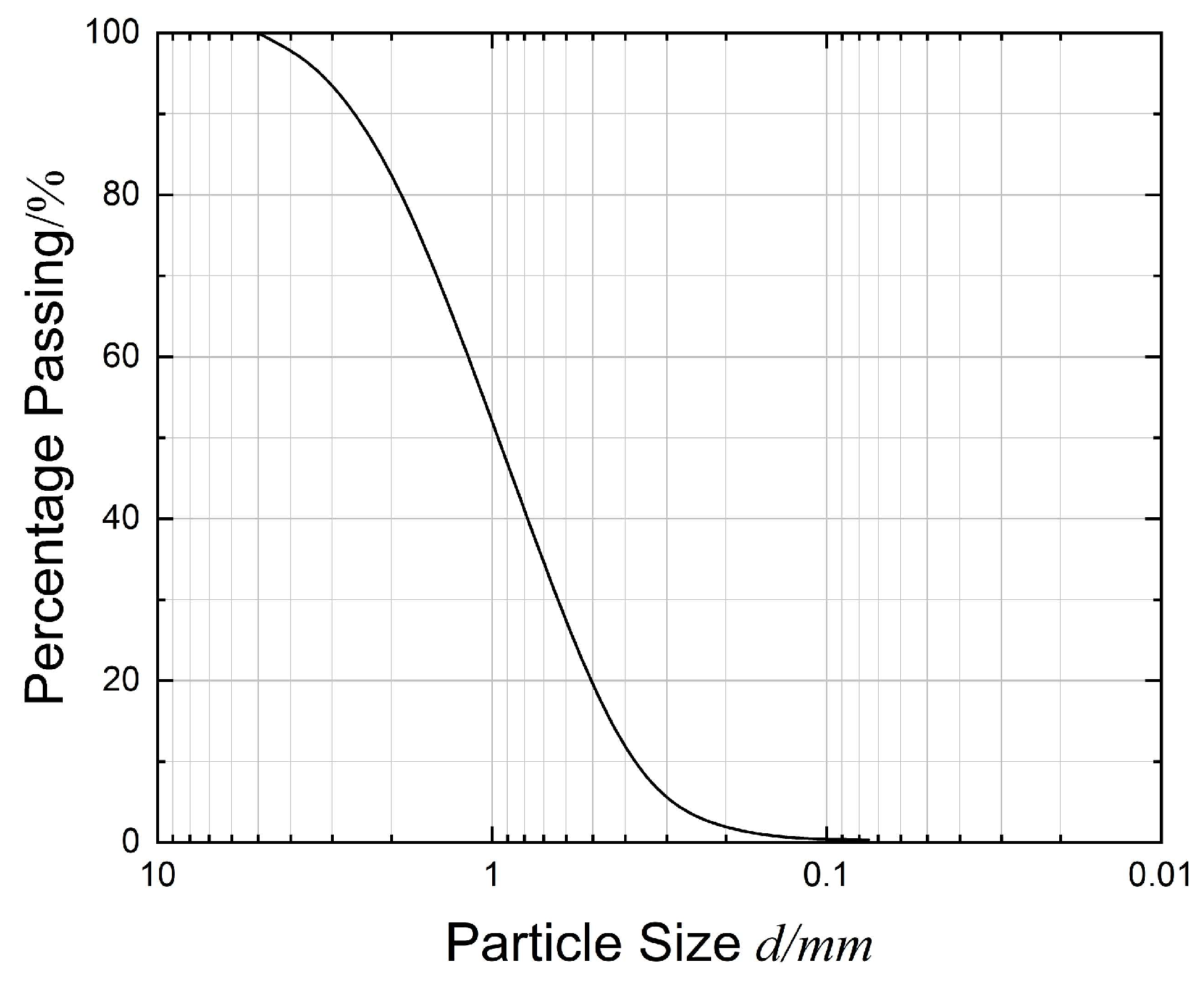

2.1. Physical Properties of the Model Soil

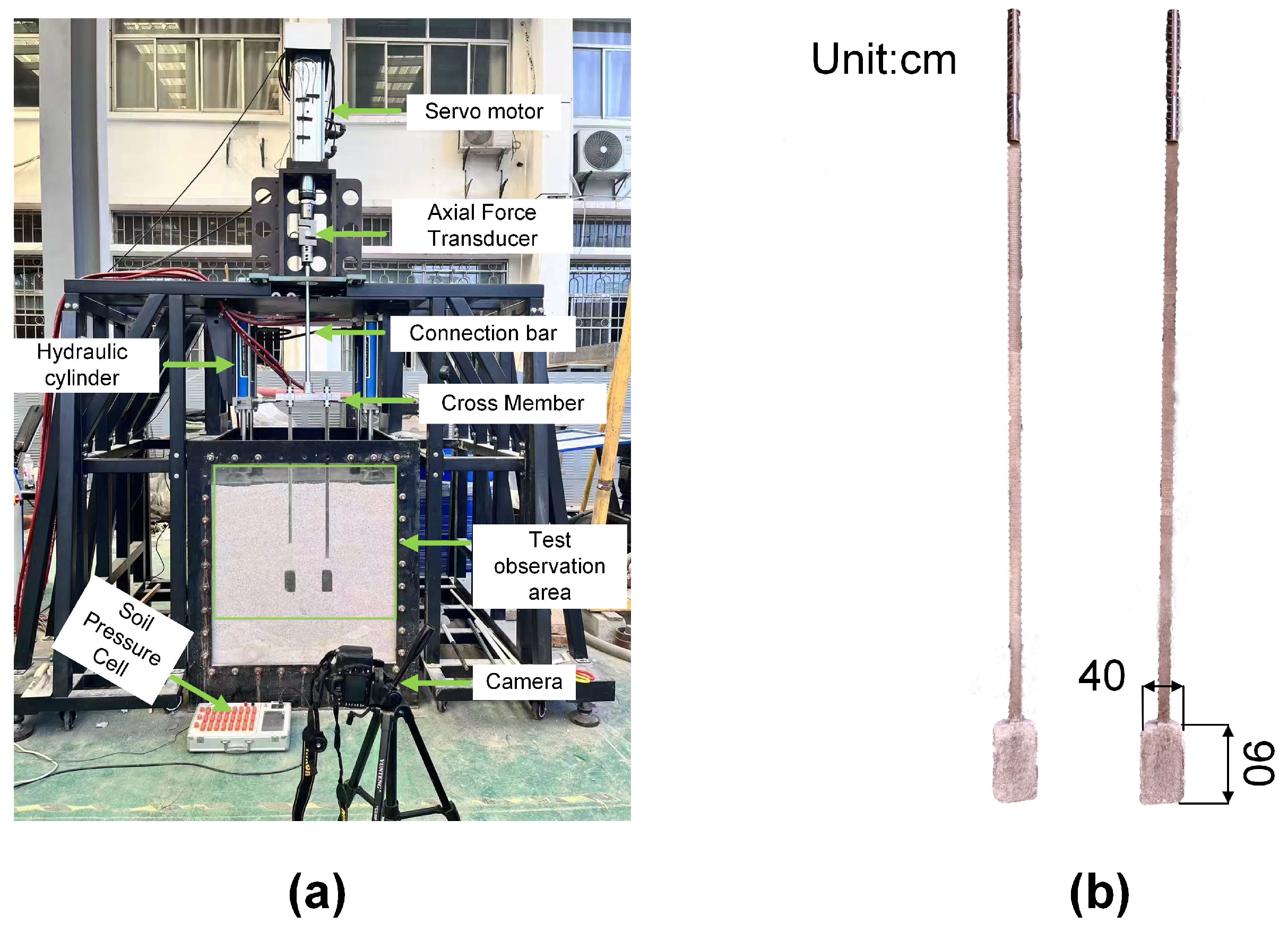

2.2. Cyclic Loading Testing Equipment

2.3. Test Plan

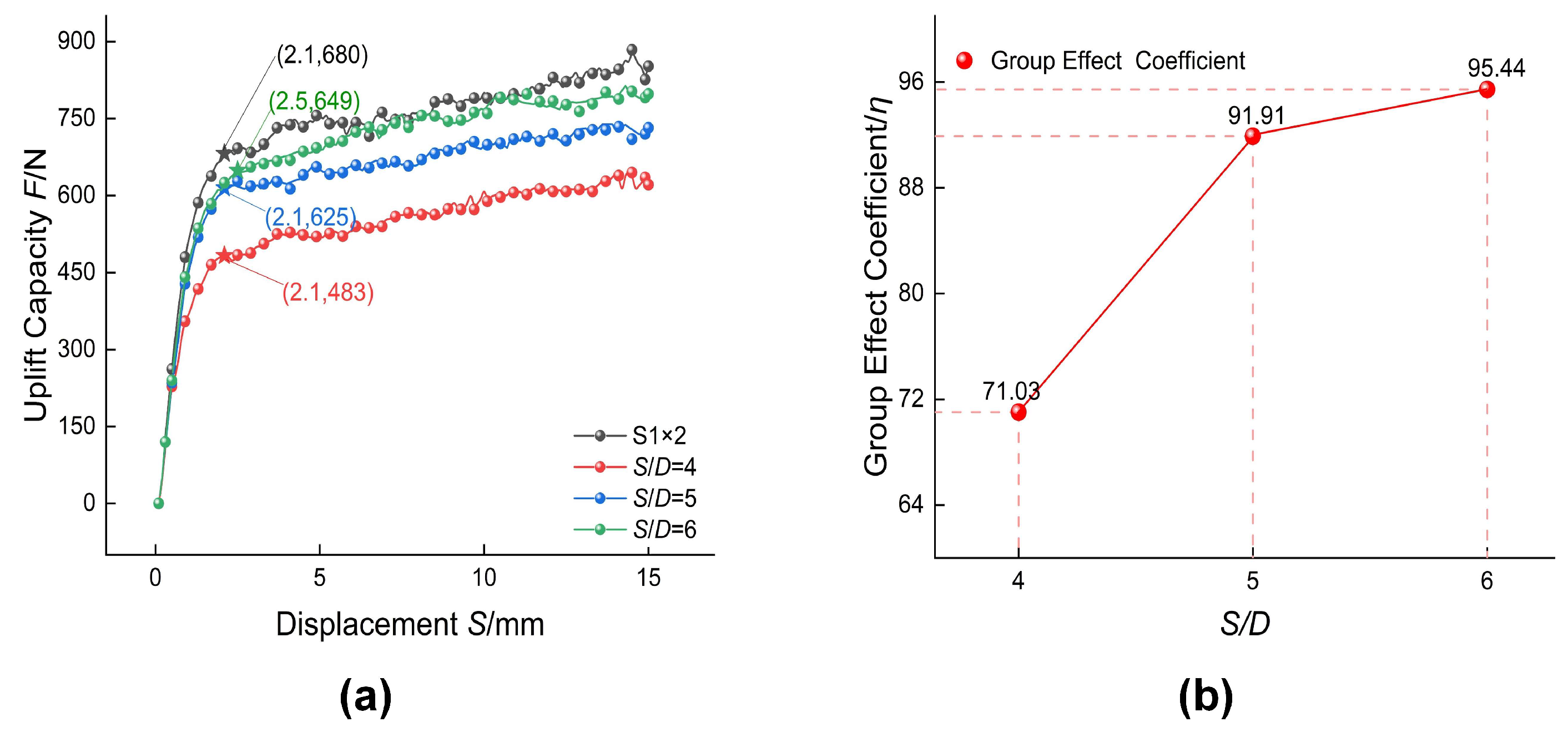

3. Spacing Ratio Effects in Single Pull-Out Tests

3.1. Variation in Anchor Group Uplift Bearing Capacity with Spacing Ratio

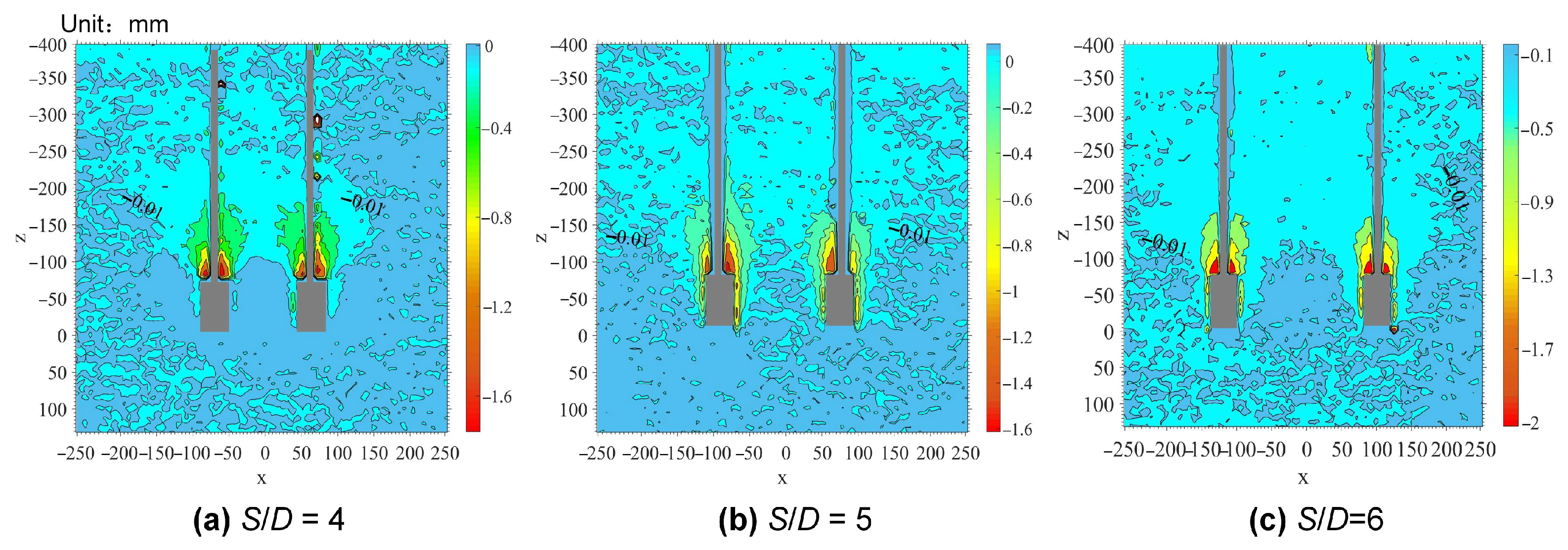

3.2. Displacement Contours Under Different Spacing Ratios

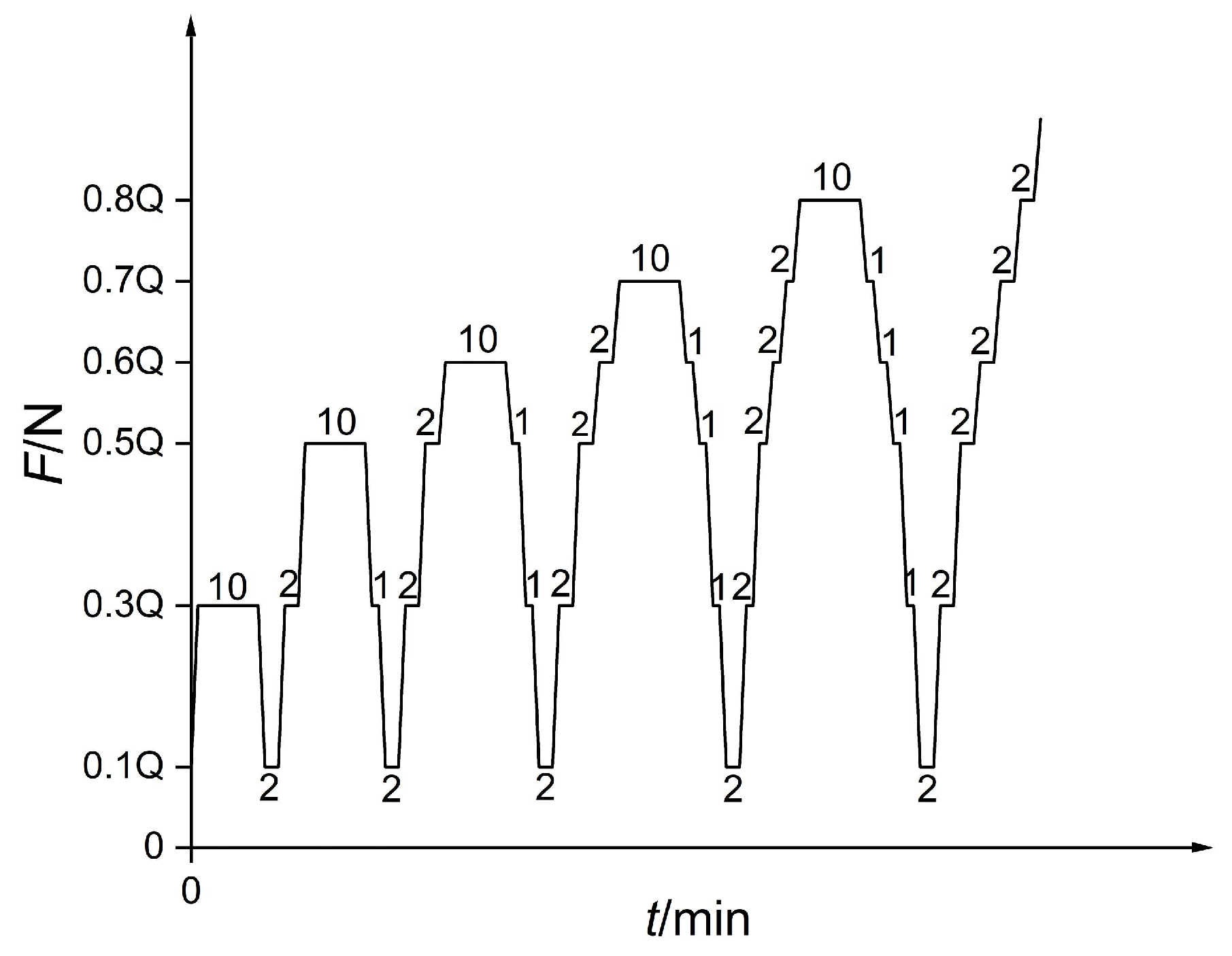

4. Cyclic Amplitude Effects

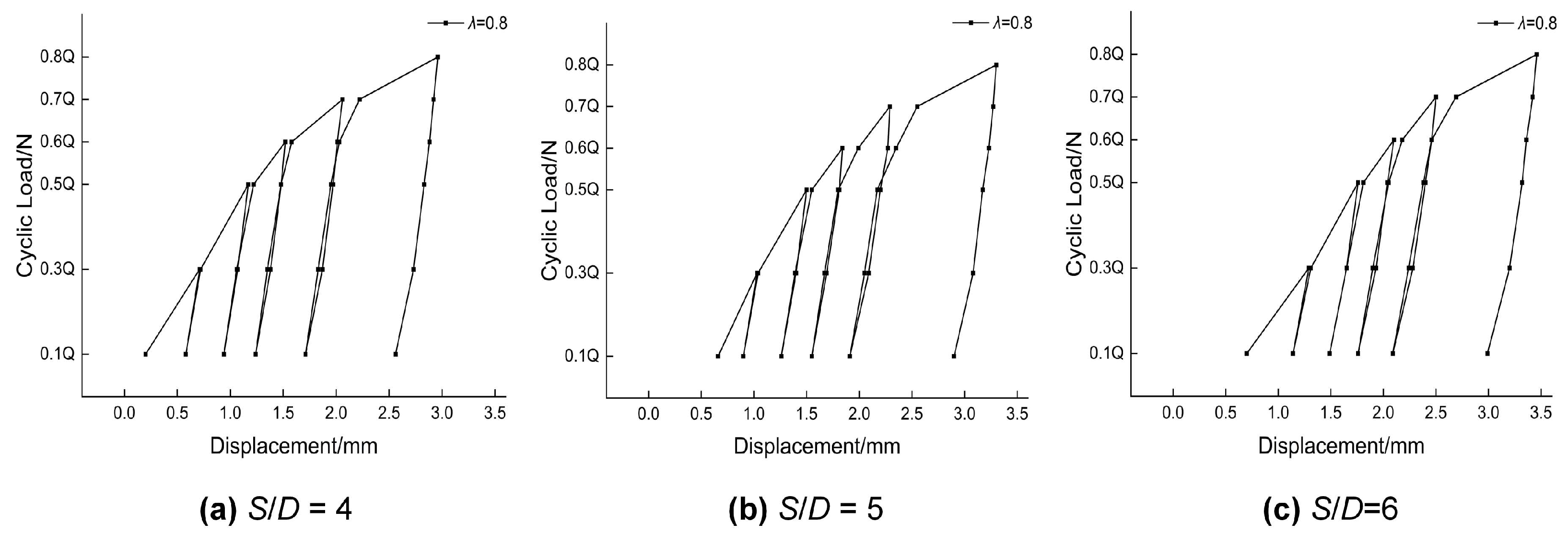

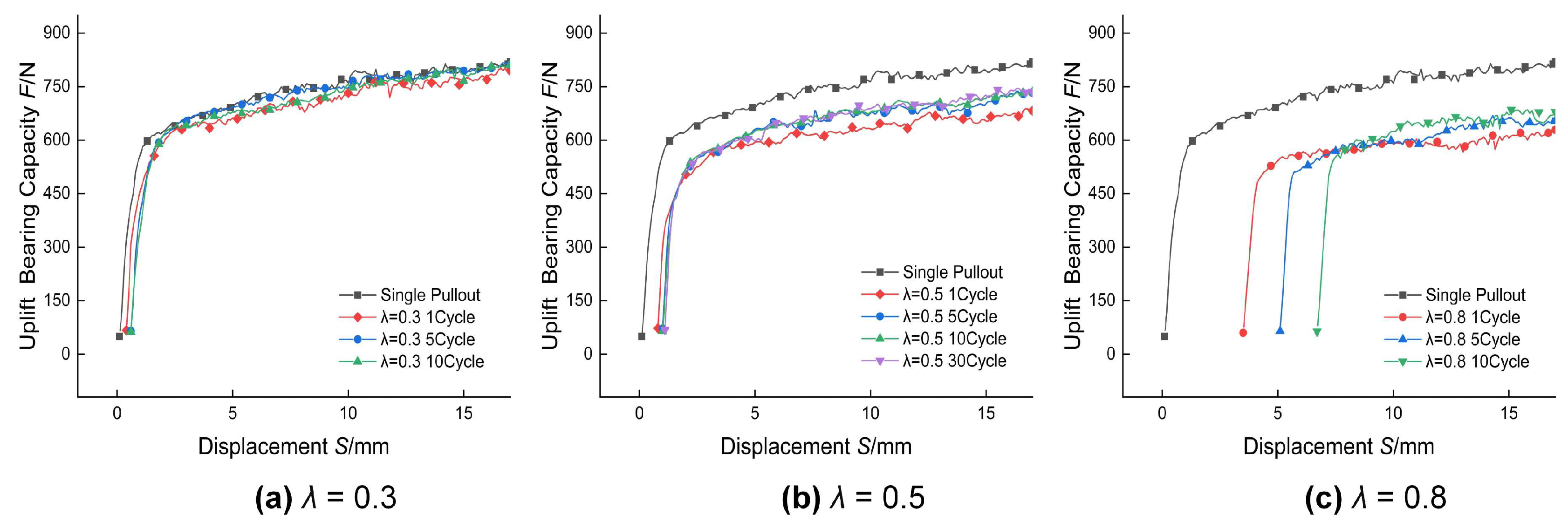

4.1. Load–Displacement Curves Under Different Cyclic Amplitude Ratios

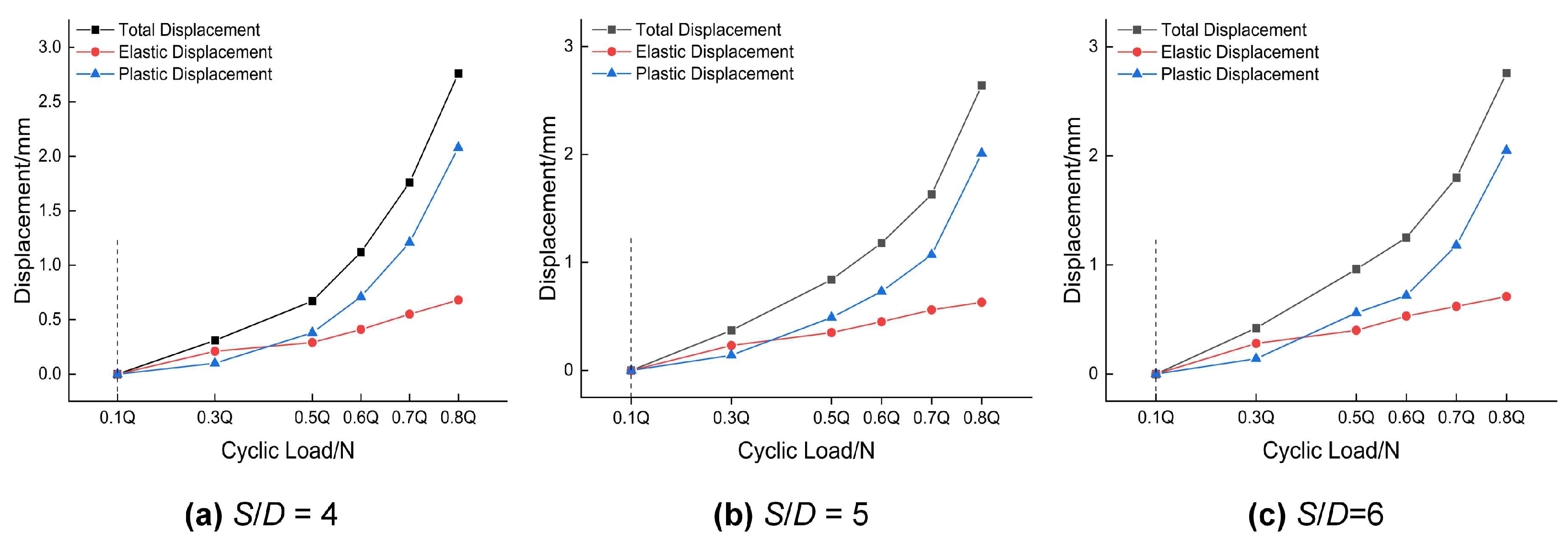

4.2. Post-Cyclic Amplitude Effects

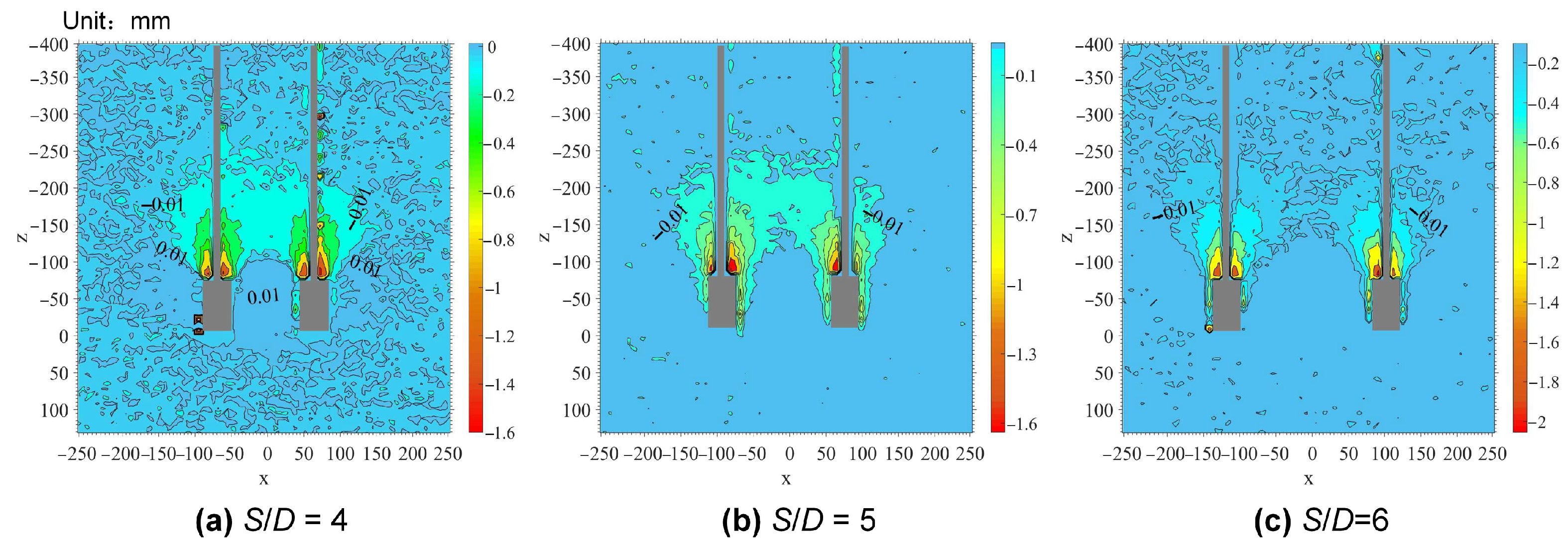

4.3. Post-Cyclic Displacement Contours

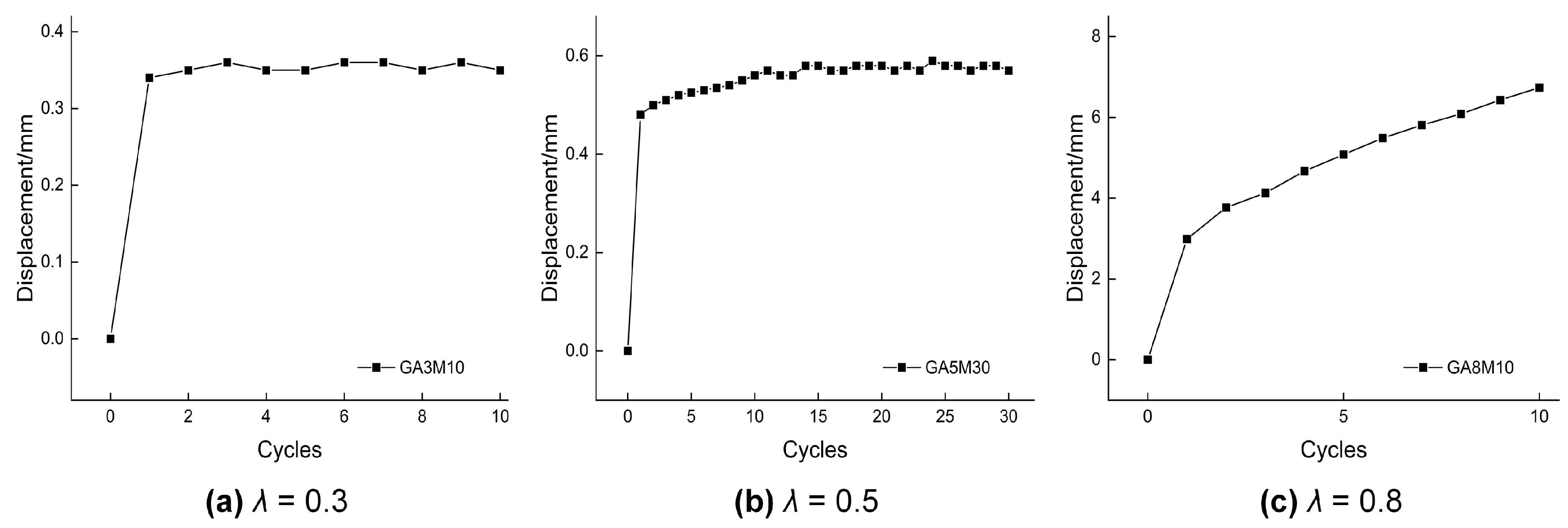

5. Cyclic Times Effects

5.1. Load–Displacement Curves Under Various Cyclic Times

5.2. Effects After Various Cyclic Times

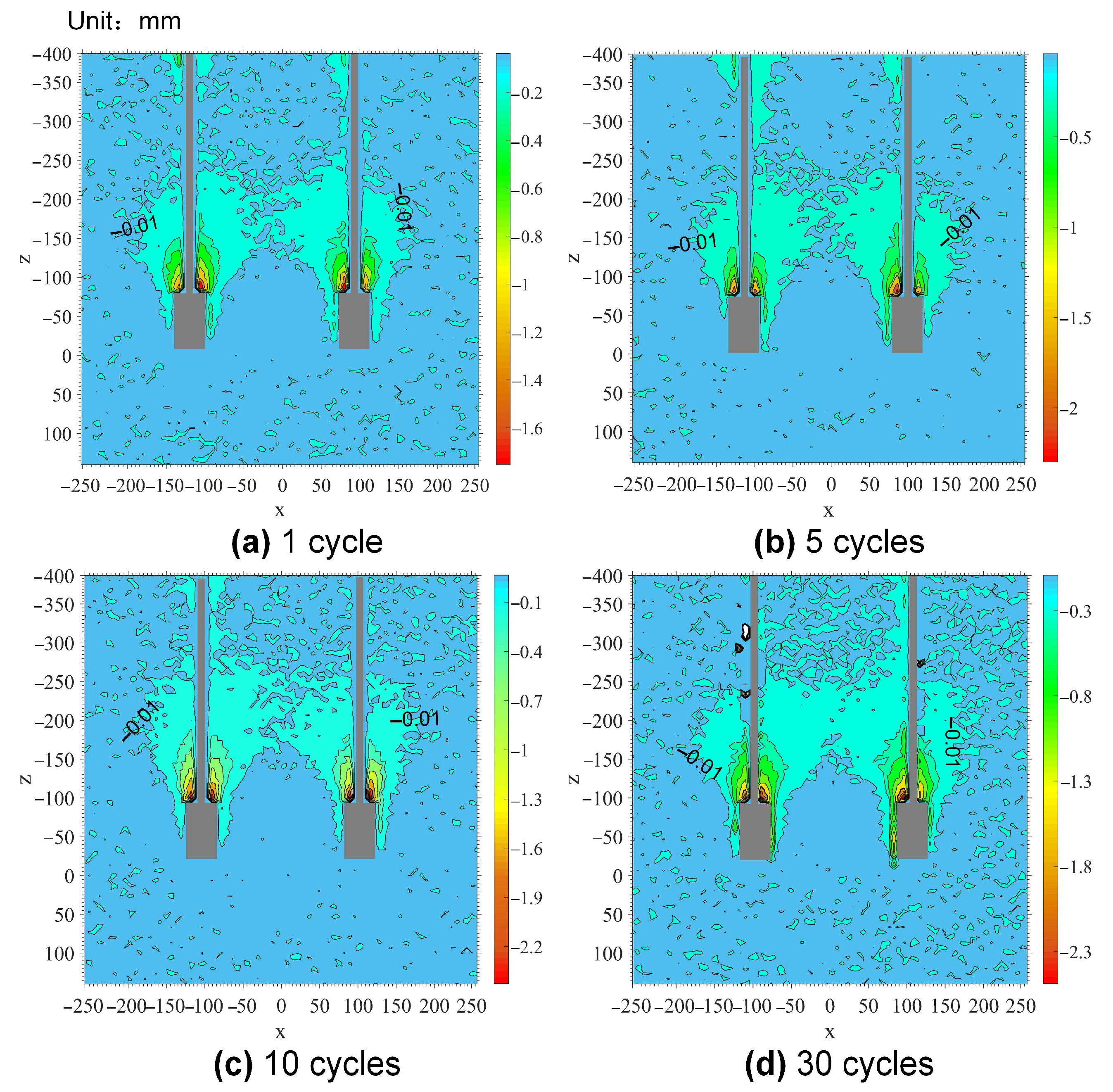

5.3. Post-Cyclic Displacement Contours

6. Discussion

7. Limitations and Future Recommendations

8. Conclusions

- (1)

- The optimal spacing ratio for anchor groups was dependent on anchor type. For under-reamed anchor groups investigated in this study, the optimal spacing ratio was identified as 5.

- (2)

- During the elastic stage, the uplift bearing capacity of the anchor group was negligibly affected by the spacing ratio. The group effect emerged in the elastoplastic stage and became significant in the plastic stage.

- (3)

- Both the cyclic amplitude ratio and the number of cyclic times influenced the ultimate uplift bearing capacity, with the cyclic amplitude ratio exerting a more pronounced effect. When λ < 0.5, the ultimate uplift bearing capacity degraded by only 1.39% (λ = 0.3). For 0.5 ≤ λ ≤ 0.7, the maximum degradation did not exceed 1%. At λ > 0.7, anchor failure occurred during both the cyclic process and the subsequent pull-out test, with the ultimate uplift bearing capacity degradation reaching 16.8% (λ = 0.8).

- (4)

- The degradation of the ultimate uplift bearing capacity of under-reamed anchor groups following cyclic loading was primarily attributed to the deterioration of the shear strength at the anchor-soil interface along the sidewall of the under-reamed body.

- (5)

- The influence of the number of cyclic times on anchor performance depended on whether anchor failure occurred. Under non-failure conditions, the influence of the number of cyclic times was marginal, and the ultimate uplift bearing capacity essentially stabilized after the first cycle. Conversely, under failure conditions, the maximum fluctuation in the ultimate uplift bearing capacity due to the number of cyclic times could reach 7.71%.

- (6)

- In specific cases, compared to a single cycle, the ultimate uplift bearing capacity of the anchor group showed a slight improvement after 10 cycles, but the maximum increase did not exceed 7.25%.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, J.; Deng, H.; Liu, Z.; Dai, G.; Ke, L.; Guo, X.; Zhang, Z. Protection of Low-Strength Shallow-Founded Buildings Around Deep Excavation: A Case Study in the Yangtze River Soft Soil Area. Buildings 2025, 15, 4094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Xia, Y.Y.; Li, C.Q.; Ni, Q. Experimental investigations of end bearing anchors under uplift load using transparent soil and numerical simulation. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2020, 45, 3743–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.G.; Wang, B.T.; Le, J.; Ma, Y.Q.; Zhang, M.L. Experimental investigation on the anchorage performance of a tension-compression-dispersed composite anti-floating anchor. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Xia, Y.Y.; Ni, Q. Investigation on the working mechanism and structural parameters optimization of multiple ball shaped nodular anchors. Soil Mech. Found. Eng. 2020, 57, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyuiwoong, K.; Kwangkuk, A. Behavior characteristics of under-reamed ground anchor through field test and numerical analysis. J. Korean Geo-Environ. Soc. 2013, 14, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Ye, S.L. A field study on the behavior of a foundation underpinned by micropiles. Can. Geotech. J. 2011, 43, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Zhu, R.; Huang, Z.; Xiao, F.; Yin, H.; Zhao, T.; Huang, M. Mechanical Analysis and Prototype Testing of Prestressed Rock Anchors. Buildings 2025, 15, 3952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatar, W.; Xiao, F.; Chen, G.; Nghiem, H. Assessment of the Conditions of Anchor Bolts Grouted with Resin and Cement Through Impact-Echo Testing and Advanced Spectrum Analysis. Buildings 2025, 15, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Chen, R.; Ji, Y.; Li, P.; Ma, Z.; Jiang, X. Mechanical Properties of Reinforcement Cage Underreamed Anchor Bolts and Their Application in Soft Rock Slope Stabilization. Buildings 2025, 15, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geddes, J.D.; Murray, E.J. Plate anchor group pulled vertically in sand. J. Geotech. Eng. 1996, 122, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, M.; Chakraborty, D.; Kumawat, V. Model test study on single and group under-reamed piles in sand under compression and tension. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2022, 7, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tistel, J.; Grimstad, G.; Eiksund, G. Testing and modeling of cyclically loaded rock anchors. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2017, 9, 1010–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Lee, S.R.; Kim, N.K.; Kim, T.H. A numerical study of the pullout behavior of grout anchors under-reamed by pulse discharge technology. Comput. Geotech. 2013, 47, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.H.; Jia, P.S.; Sun, J.P.; Jiang, Z.B.; Yang, F.; Yang, G.R.; Shao, G.B. Research and application of new anti-floating anchor in anti-floating reinforcement of existing underground structures. Front. Earth Sci. 2024, 12, 1364752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Douri, R.H.; Poulos, H.G. Predicted and Observed Cyclic Performance of Piles in Calcareous Sand. J. Geotech. Eng. 1995, 121, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, D.; Che, J.; Chen, R.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, C.; Chen, X. Experimental Investigation on Behavior of Single-Helix Anchor in Sand Subjected to Uplift Cyclic Loading. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, M.; Liu, Y. Model tests on a single pile considering influence of sand density under cyclic axial loading. Rock Soil Mech. 2016, 37, 1914. [Google Scholar]

- Rui, R.; Xiao, F.Y.; Cheng, Y.H.; Gao, F.; Hu, S.G.; Ding, Y.H.; Sun, T.J. Experimental study on pull-out resistance of plate anchors at different buried depths. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2023, 45, 2032–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgari, A.; Arjomand, M.A.; Bagheri, M.; Ebadi-Jamkhaneh, M.; Mostafaei, Y. Assessment of Experimental Data and Analytical Method of Helical Pile Capacity Under Tension and Compressive Loading in Dense Sand. Buildings 2025, 15, 2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JGJ476—2019; Technical Standard for Building Engineering Against Uplift. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2020.

- Guo, G.; Liu, Z.; Tang, A.P. Model test research on bearing mechanism of underreamed ground anchor in sand. Math. Probl. Eng. 2018, 2018, 9746438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liang, W.P.; Ying, H.W. Experimental and numerical research on proper interval of large diameter soil-cement anchor cables. Rock Soil Mech. 2018, 39, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, D.J.; Take, W.A.; Bolton, M.D. Soil deformation measurement using particle image velocimetry (PIV) and photogrammetry. Géotechnique 2003, 53, 619–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yue, J.C.; Liu, H.D. Experimental study of soil deformation around group anchors in sand. Rock Soil Mech. 2016, 37, 240–248. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.K.; Bai, X.Y.; Sun, G.; Wang, F.J.; Yan, N.; Dong, X.G. Field test of anchorage performance of BFRP anti-floating anchor under multiple cyclic loads. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2024, 43, 2314–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, J.W.; Zhu, N.; Zhao, G.X. Dynamic response of open pipe pile under vertical cyclic loading in sand and clay. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2020, 139, 106364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehane, B.; White, D. Friction fatigue on displacement piles in sand. Geotechnique 2004, 54, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.M.; Zhang, C.R.; Zhang, K. Model tests of large-diameter single pile under horizontal cyclic loading in sand. Rock Soil Mech. 2021, 42, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.; Yan, W.M. A multidirectional p–y model for lateral sand–pile interactions. Soils Found. 2013, 53, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ρ, g/cm−3 | ω, % | Cu | Dr | c, kPa | φ, ° | ρmax, g/cm−3 | ρmin, g/cm−3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.839 | 0 | 2.69 | 0.76 | 0 | 42.3 | 1.97 | 1.52 |

| Anchor Type | S/D | D, mm | Unbonded Length, mm |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | - | 40 | 810 |

| G1 | 4 | ||

| G2 | 5 | ||

| G3 | 6 |

| Test No. | Cyclic Amplitude Ratio/λ | Cyclic Times/M | S/D | D, mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GA3M1 | 0.3 | 1 | 6 | 40 |

| GA3M5 | 5 | |||

| GA3M10 | 10 | |||

| GA5M1 | 0.5 | 1 | 6 | 40 |

| GA5M5 | 5 | |||

| GA5M10 | 10 | |||

| GA5M30 | 30 | |||

| GA6M1 | 0.6 | 1 | 6 | 40 |

| GA7M1 | 0.7 | 1 | 6 | 40 |

| GA8M1 | 0.8 | 1 | 4 | 40 |

| GB8M1 | 1 | 5 | ||

| GC8M1 | 1 | 6 | ||

| GA8M5 | 5 | 6 | ||

| GA8M10 | 10 | 6 |

| Test No. | Qg, N | δ, mm | S/D | η, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 340 | 2.1 | - | - |

| G1 | 483 | 2.1 | 4 | 71.03 |

| G2 | 625 | 2.1 | 5 | 91.91 |

| G3 | 649 | 2.5 | 6 | 95.44 |

| Test No. | Cyclic Amplitude Ratio/λ | δ, mm | Qg, N | η, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GA3M1 | 0.3 | 2.6 | 640 | 1.39 |

| GA5M1 | 0.5 | 2.9 | 611 | 5.86 |

| GA6M1 | 0.6 | 3.2 | 605 | 6.78 |

| GA7M1 | 0.7 | 3.3 | 604 | 6.93 |

| GA8M1 | 0.8 | 4.3 | 540 | 16.8 |

| Test No. | Cyclic Amplitude Ratio, λ | Cyclic Times, M | δ, mm | Qg, N | η, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GA3M1 | 0.3 | 1 | 2.6 | 640 | 1.39 |

| GA3M5 | 5 | 2.7 | 653 | −0.62 | |

| GA3M10 | 10 | 2.7 | 655 | −0.92 | |

| GA5M1 | 0.5 | 1 | 2.9 | 611 | 5.86 |

| GA5M5 | 5 | 3.3 | 614 | 5.39 | |

| GA5M10 | 10 | 3.3 | 615 | 5.24 | |

| GA5M30 | 30 | 3.3 | 613 | 5.55 | |

| GA8M1 | 0.8 | 1 | 4.3 | 540 | 16.8 |

| GA8M5 | 5 | 5.8 | 537 | 17.26 | |

| GA8M10 | 10 | 7.6 | 587 | 9.55 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, C.; Liu, Z.; Yang, J. Model Test Study on Group Under-Reamed Anchors Under Cyclic Loading. Buildings 2026, 16, 540. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030540

Chen C, Liu Z, Yang J. Model Test Study on Group Under-Reamed Anchors Under Cyclic Loading. Buildings. 2026; 16(3):540. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030540

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Chen, Zhe Liu, and Junchao Yang. 2026. "Model Test Study on Group Under-Reamed Anchors Under Cyclic Loading" Buildings 16, no. 3: 540. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030540

APA StyleChen, C., Liu, Z., & Yang, J. (2026). Model Test Study on Group Under-Reamed Anchors Under Cyclic Loading. Buildings, 16(3), 540. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030540