1. Introduction

The ongoing development of geotechnical engineering has spurred the advancement of new bolt technologies [

1,

2,

3]. Compared to traditional metal bolts, Basalt Fiber Reinforced Polymer (BFRP) bolts offer advantages such as a light weight and high strength, making them increasingly popular in tunnel excavation and geotechnical support applications [

4,

5]. As a new type of composite material, BFRP bolts are particularly notable for their excellent corrosion resistance. However, their mechanical properties [

6] differ significantly from those of conventional bolts, which has hindered their widespread adoption. Therefore, conducting effective quality inspections of BFRP bolts is essential for promoting their application and ensuring the safety and reliability of support systems in mining and geotechnical engineering.

Traditional methods for evaluating the quality of metal bolt anchorages, such as pull-out tests and core sampling [

7], are destructive in nature, costly, and inefficient. With the advancement of non-destructive testing (NDT) technologies, methods based on stress waves [

8] and ultrasonic guided waves [

9,

10] have attracted increasing attention. In the field of stress wave detection, Yang et al. [

11] conducted NDT of anchorage defects using the transmission and reflection characteristics of stress waves and applied wavelet transform to analyze the test signals. Their results demonstrated the method’s ability to accurately detect grouting length, defect length, and defect location. Li et al. [

12] studied and analyzed the waveform characteristics of steel bolts with different grouting densities through laboratory tests and established the acceptance criteria for the non-destructive testing of bolts in the project. Zhao [

13] employed numerical simulation and experimental methods to study the propagation of stress waves in bolts under impact loading, and applied the method to inspect BFRP bolt anchorage quality. The results confirmed that the elastic wave method can effectively determine bolt length with a sufficient accuracy for engineering requirements. Regarding ultrasonic guided wave detection, Mu [

14] used the semi-analytical finite element (SAFE) method to model guided wave propagation in hollow cylinders with viscoelastic layers and provided dispersion curves and attenuation characteristics for both axisymmetric and flexural modes. Wang et al. [

15,

16] and He et al. [

17,

18] investigated the generation mechanisms of guided waves in bolt anchorage structures and, through numerical simulations, analyzed the propagation characteristics of low-frequency guided waves. They identified a frequency range where clear reflection signals occur at the bolt–end interface and concluded that torsional modes are unsuitable for long-distance bolt detection. Zhang et al. [

19,

20,

21] used numerical simulation to evaluate the influence of mesh size on longitudinal guided wave propagation in bolt anchorage structures and proposed a mesh refinement criterion. They determined an optimal excitation frequency of 25 kHz for low-frequency guided wave detection. Li et al. [

22] tested bolt anchorage structures with different configurations and grouting qualities using both low- and high-frequency guided waves, revealing that grouting quality significantly affects wave velocity. Zima [

23] investigated guided wave propagation in bolt anchorage systems both numerically and experimentally and observed energy transfer phenomena within the anchorage structure. Furthermore, Song et al. [

24] derived coupled wave equations for longitudinal guided waves in orthotropic anisotropic materials, calculated the dispersion curves of flexural modes for different radius-to-thickness ratios, and analyzed how these ratios affect dispersion behavior. Rong et al. [

25] assessed bolt anchorages under complete and partial grouting loss conditions using NDT techniques to evaluate the effectiveness of waveform interpretation methods.

The above studies have laid a solid foundation for the NDT of bolt anchorage structures. However, it is worth noting that intelligent structural health monitoring methods based on ultrasonic guided waves are receiving increasing attention, especially when combined with machine learning to improve damage detection and feature extraction in complex structures [

26]. In a recent study, Xing et al. [

27] proposed a waveguide time spectrum and gated attention residual network (GA-ResNet) to solve the problem of the difficult feature extraction of anchorage defects. Han et al. [

28] proposed a multi-scale convolutional neural network (MS-CNN) to assess the degree of corrosion of metal bolts. The results showed that this method can effectively detect and diagnose the degree of corrosion of bolts. To address the issue of bolted joints being susceptible to various types of damage, Liao et al. [

29] proposed a high-level robust Random Forest Generalized Regression Neural Network (RF-GRNN) algorithm, which solves the problems of damage classification and quantification. Huang et al. [

30]. demonstrated that variations in environmental and structural temperatures significantly alter the dynamic properties of materials and structures. They proposed a temperature-compensated damage detection method based on time-series models and neural networks to reliably identify damage. In addition, swarm intelligence optimization algorithms [

31,

32] have been extensively applied to engineering optimization problems involving multi-parameter coupling in recent years and have gradually been introduced into the field of non-destructive testing. The existing research indicates that an optimization framework based on objective functions [

33], combined with swarm intelligence algorithms, can effectively enhance damage-sensitive features and obtain optimal parameters. This holds significant importance for the damage detection of BFRP bolts.

The above studies demonstrate a growing body of research on the NDT of metal bolts, while relatively few investigations have focused on BFRP bolt anchorage structures. To address this gap, this study systematically investigates the propagation characteristics of guided waves in BFRP bolt anchorage structures through a combination of experimental testing and numerical simulation. This research provides a scientific basis and methodological references for the effective non-destructive testing of BFRP bolts.

The structure of this paper is as follows:

Section 2 investigates the influence of different excitation frequencies on the guided wave propagation characteristics in BFRP bolts and anchorage bolts through experimental studies, identifying the optimal parameters for guided wave testing.

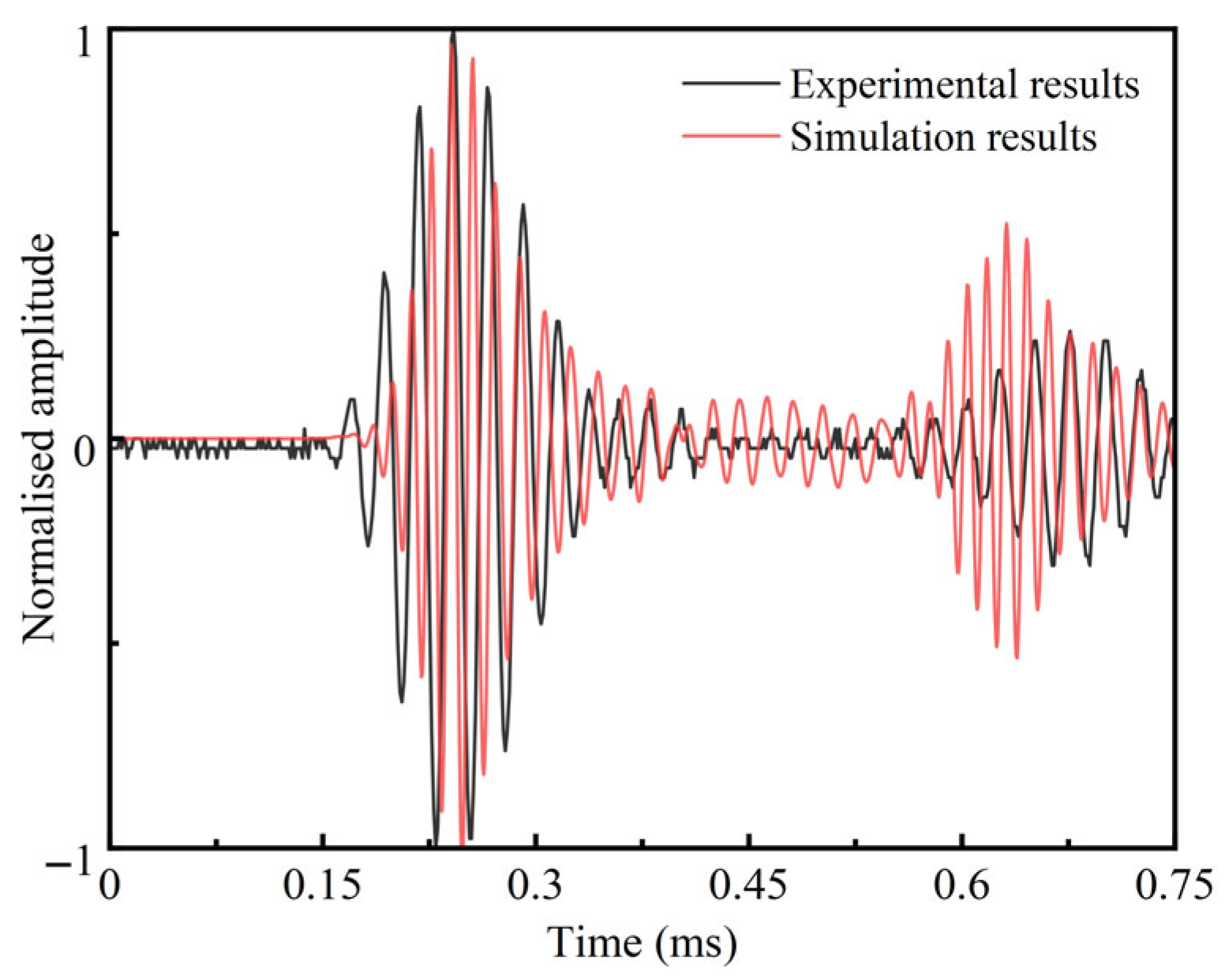

Section 3 establishes a numerical model for the BFRP bolt anchorage structure, verifying the model’s validity by analyzing experimental and numerical simulation results.

Section 4 investigates the effects of material parameter variations and anchorage defect characteristics on guided wave responses. Finally,

Section 5 summarizes the key findings of this study.

4. Numerical Simulation Results

Based on ABAQUS finite element software, the propagation characteristics of guided waves in anchorage structures are systematically investigated by changing the material parameters, geometric structure, and anchorage defects. The study revealed the effects of these factors on wave dispersion, attenuation, wave velocity, radial inhomogeneity, and echo response characteristics. These simulation results help address the limitations of the theoretical analyses and experimental conditions, providing deeper insights into the behavior of guided waves in such complex structures. It should be emphasized that the objective of this section is not to conduct formal engineering optimization, but to investigate the sensitivity of guided wave responses to key material parameters and defect-related parameters.

4.1. Effect of Anchorage Medium Parameters on the Propagation Characteristics of Guided Waves

The propagation characteristics of guided waves in bolts are affected by the anchorage medium. The bolt anchorage model was simulated and analyzed using finite element software [

43,

44], and its effect on the wave velocity, attenuation, waveform characteristics, and the inhomogeneity of the distribution along the bolt cross-section of the guided wave in the bolt was investigated by changing the material parameters of the anchorage medium.

4.1.1. Effect of Anchorage Medium Density on the Propagation Characteristics of Guided Waves

Keeping the other basic parameters constant, we changed the density of the anchorage medium (

ρ1 = 2000 kg/m

3,

ρ2 = 2100 kg/m

3,

ρ3 = 2200 kg/m

3,

ρ4 = 2300 kg/m

3). The received waves of the bolt anchorage models with different anchorage medium densities are shown in

Figure 10. As observed, two distinct signals were recorded within the time interval of 0.3 ms to 1.2 ms. Significant differences in the propagation characteristics of the guided waves were evident across models with different densities, indicating that the density of the anchorage medium has a notable influence on guided wave propagation. As the density of the anchorage medium increases, the arrival time of the first guided wave at the receiver end becomes longer, indicating a decrease in wave velocity. This effect is even more pronounced in the second received signal, where the influence of density on wave velocity is more clearly observed. The relationship between the anchorage medium density and both wave velocity and attenuation was further analyzed using the corresponding theoretical formulas, as shown in

Figure 11. The results reveal a consistent trend: both the guided wave velocity and attenuation decrease as the density of the anchorage medium increases. The guided wave velocity and attenuation are calculated using Equations (5) and (6):

where

V is the guided wave velocity,

L is the guided wave propagation distance, and ∆

T is the time difference between the peak of the excited wave and the peak of the received wave.

where

At is the attenuation value of the guided wave,

P is the peak-to-peak value of the received wave, and

Pref is the peak-to-peak value of the excited wave.

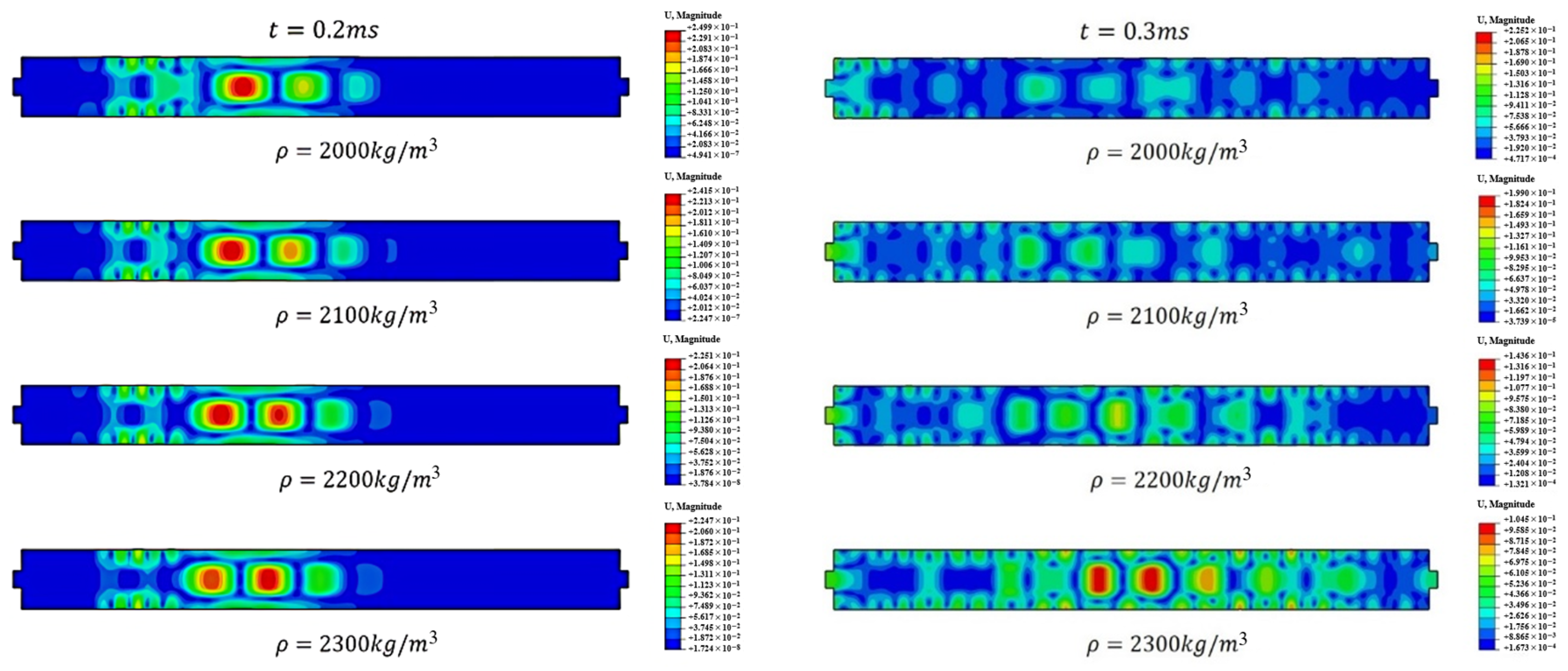

Figure 12 presents displacement cloud maps of the guided wave at 0.2 ms and 0.3 ms under varying anchorage medium densities. At

t = 0.2 ms, the guided wave has propagated to the midsection of the bolt and primarily travels within the bolt itself, with only a minor portion diffusing into the anchorage medium. At this stage, the guided wave exhibits a good directivity. As the density of the anchorage medium increases, the main displacement magnitude shown in the cloud maps decreases. At

t = 0.3 ms, the guided wave reaches the receiver end of the bolt. The displacement cloud maps at this time indicate that an increasing anchorage medium density intensifies the diffusion, internal reflection, and dispersion phenomena within the bolt anchorage structure. Similarly to the situation when

t = 0.2 ms, the displacement in the displacement cloud map tends to decrease as the density of the anchorage medium increases.

4.1.2. Effect of the Elastic Modulus of the Anchorage Medium on the Propagation Characteristics of Guided Waves

Keeping other basic parameters unchanged, the elastic modulus of the anchorage medium (

E1 = 10 GPa,

E2 = 15 GPa,

E3 = 20 GPa,

E4 = 25 GPa) is varied. The received waves of the bolt anchorage model with different elastic moduli of the anchorage medium are shown in

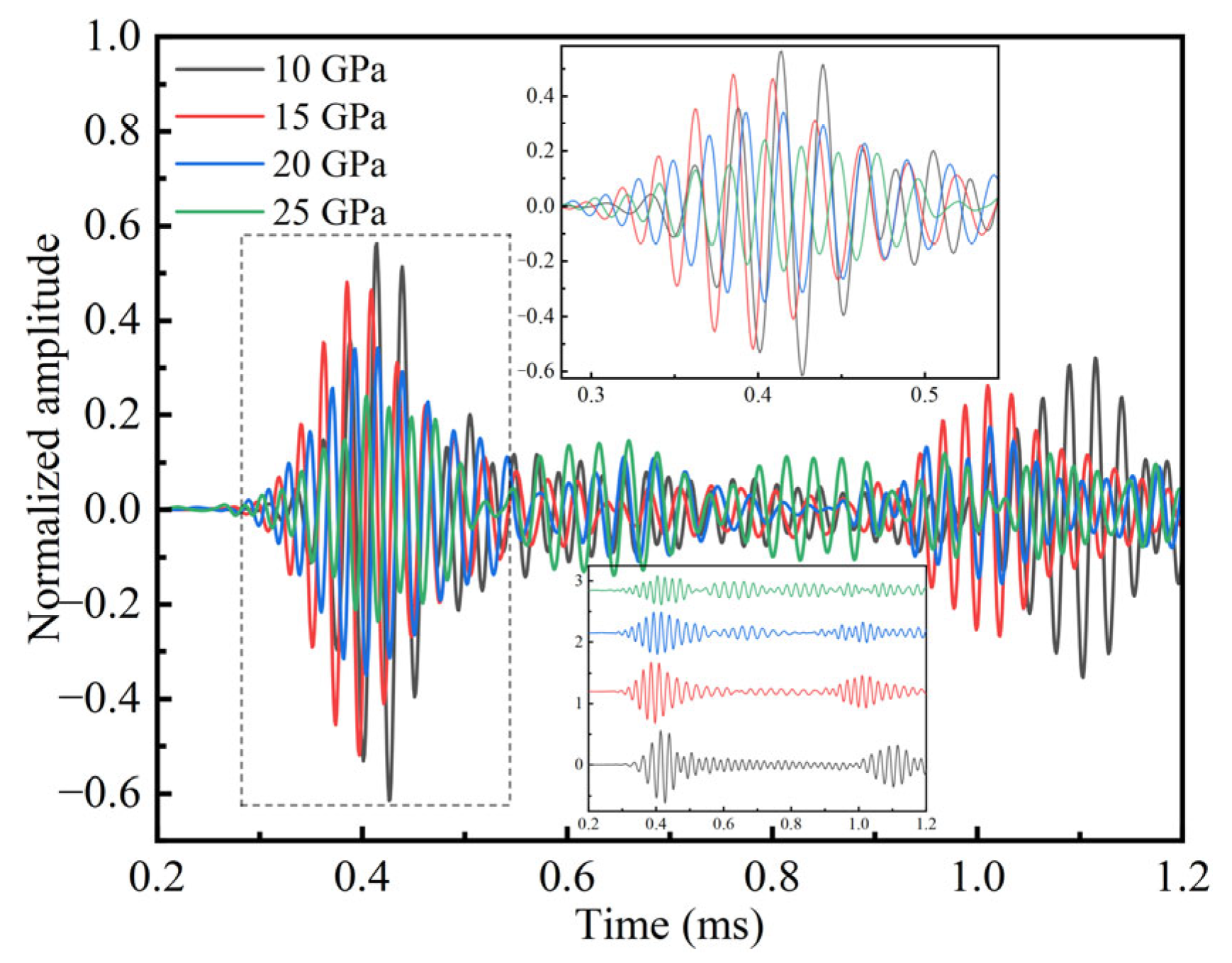

Figure 13.

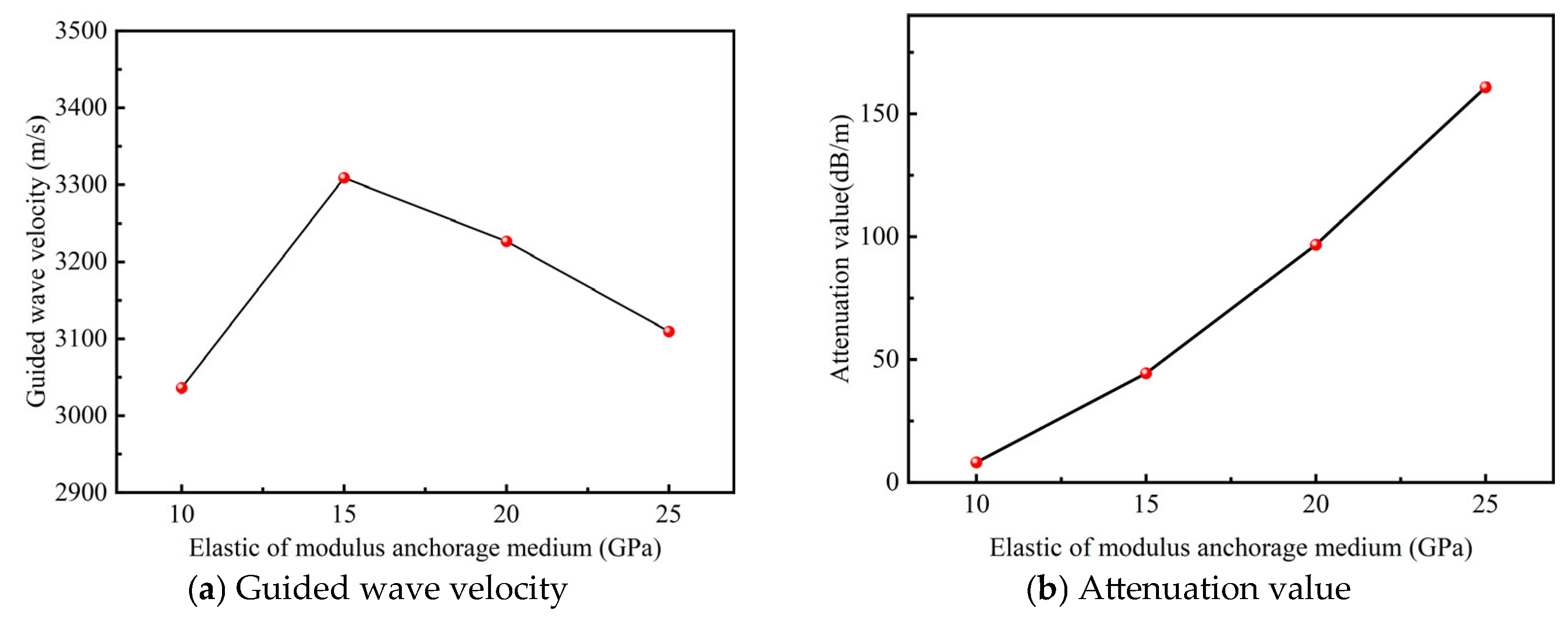

The amplified received waves shown in

Figure 13 indicate that the elastic modulus of the anchorage medium significantly affects guided wave propagation in the bolt. As the elastic modulus increases, the amplitude of the signal detected at the receiver end exhibits a clear decreasing trend. Based on the formulas for guided wave velocity and attenuation, the relationship between the elastic modulus of the anchorage medium and guided wave velocity and attenuation is illustrated in

Figure 14. From the figure, it can be seen that, within the bolt anchorage model, as the elastic modulus increases, the guided wave velocity initially rises and then decreases, while the attenuation of the guided wave increases markedly with the increasing elastic modulus. This demonstrates that variations in the anchorage medium’s elastic modulus have a pronounced impact on guided wave propagation in bolts. An elastic modulus of approximately 15 GPa appears to be the most suitable for guided wave testing of BFRP bolts.

Figure 15 presents the displacement cloud map of guided waves at 0.2 ms and 0.3 ms for models with a different anchorage medium elastic modulus. At

t = 0.2 ms, when the guided wave has propagated to the midsection of the bolt, noticeable differences are observed in the radial distribution of guided wave energy. As the elastic modulus of the anchorage medium increases, the guided wave experiences enhanced diffusion, internal reflection, and dispersion within the anchorage structure. Additionally, the amplitude of the primary displacement cloud maps decreases with the increasing elastic modulus, which can be attributed to the stronger attenuation effect of stiffer materials on wave propagation. At

t = 0.3 ms, the guided wave reaches the receiver end of the bolt. The displacement cloud reveals that the guided wave is more uniformly distributed in models with a higher elastic modulus compared to those with a lower modulus. At this moment, the maximum displacement cloud map further confirms that a greater elastic modulus leads to more pronounced diffusion and dispersion during wave propagation. This enhanced scattering effect is the primary reason for the observed reduction in the waveform amplitude.

4.1.3. Effect of Poisson’s Ratio of Anchorage Medium on Propagation Characteristics of Guided Waves

Keeping the other basic parameters unchanged, the Poisson’s ratio of the anchorage medium was varied (

v1 = 0.2,

v2 = 0.225,

v3 = 0.25,

v4 = 0.275,

v5 = 0.3). The received waves of the bolt anchorage model with different Poisson’s ratios for the anchorage medium are obtained as in

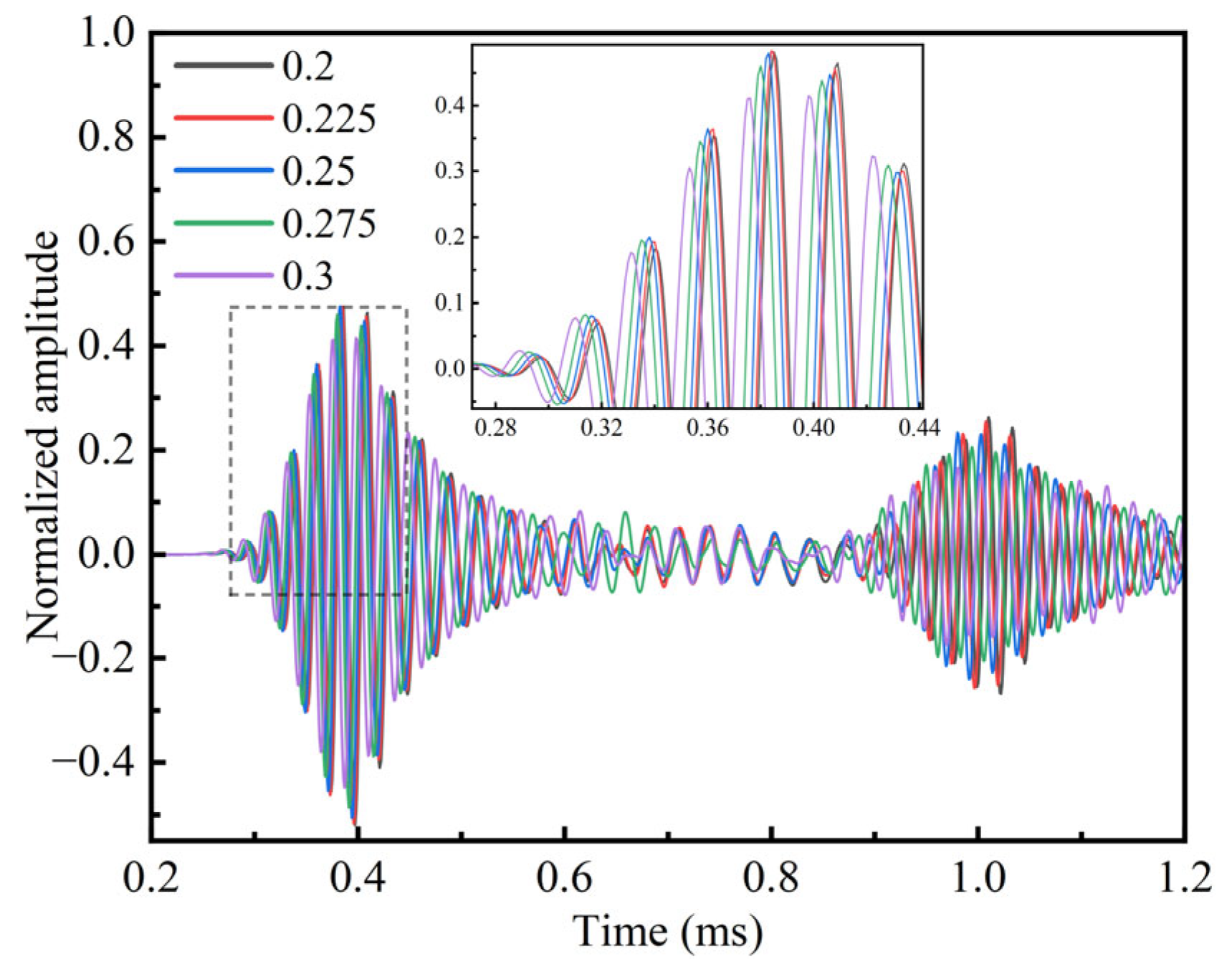

Figure 16.

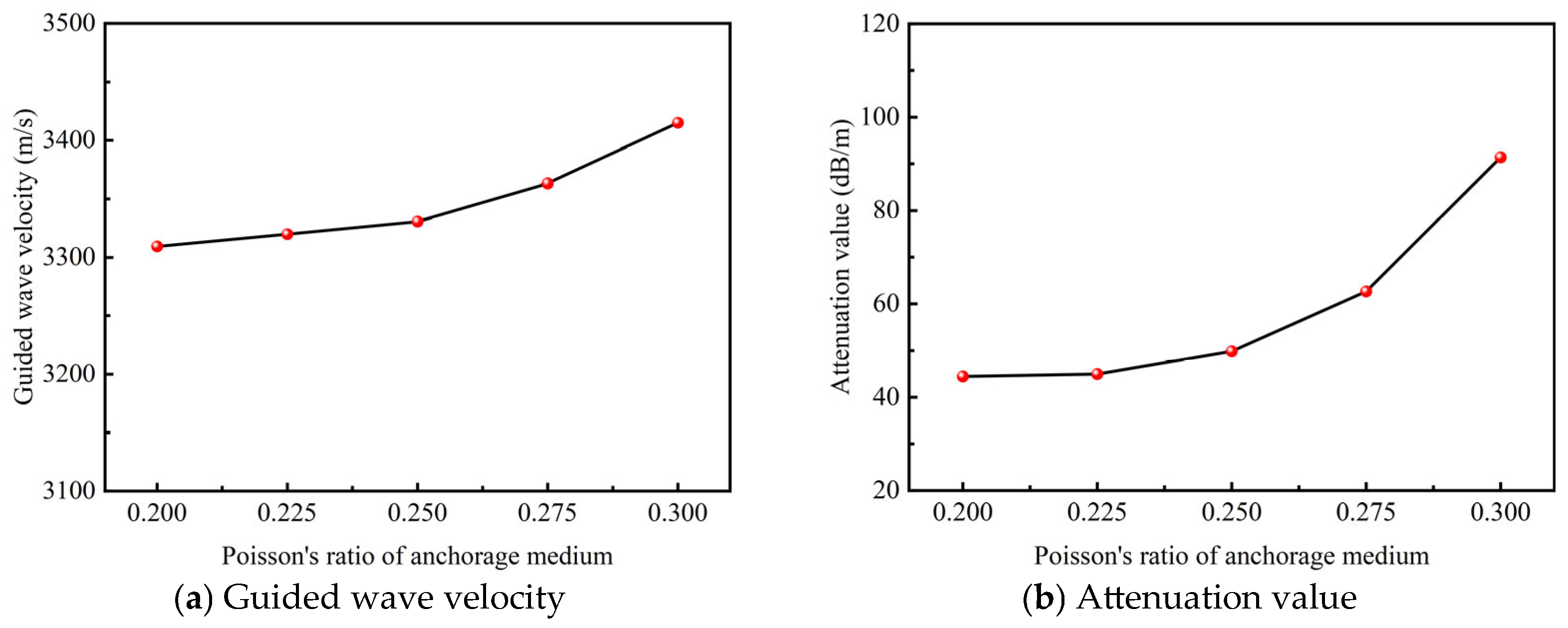

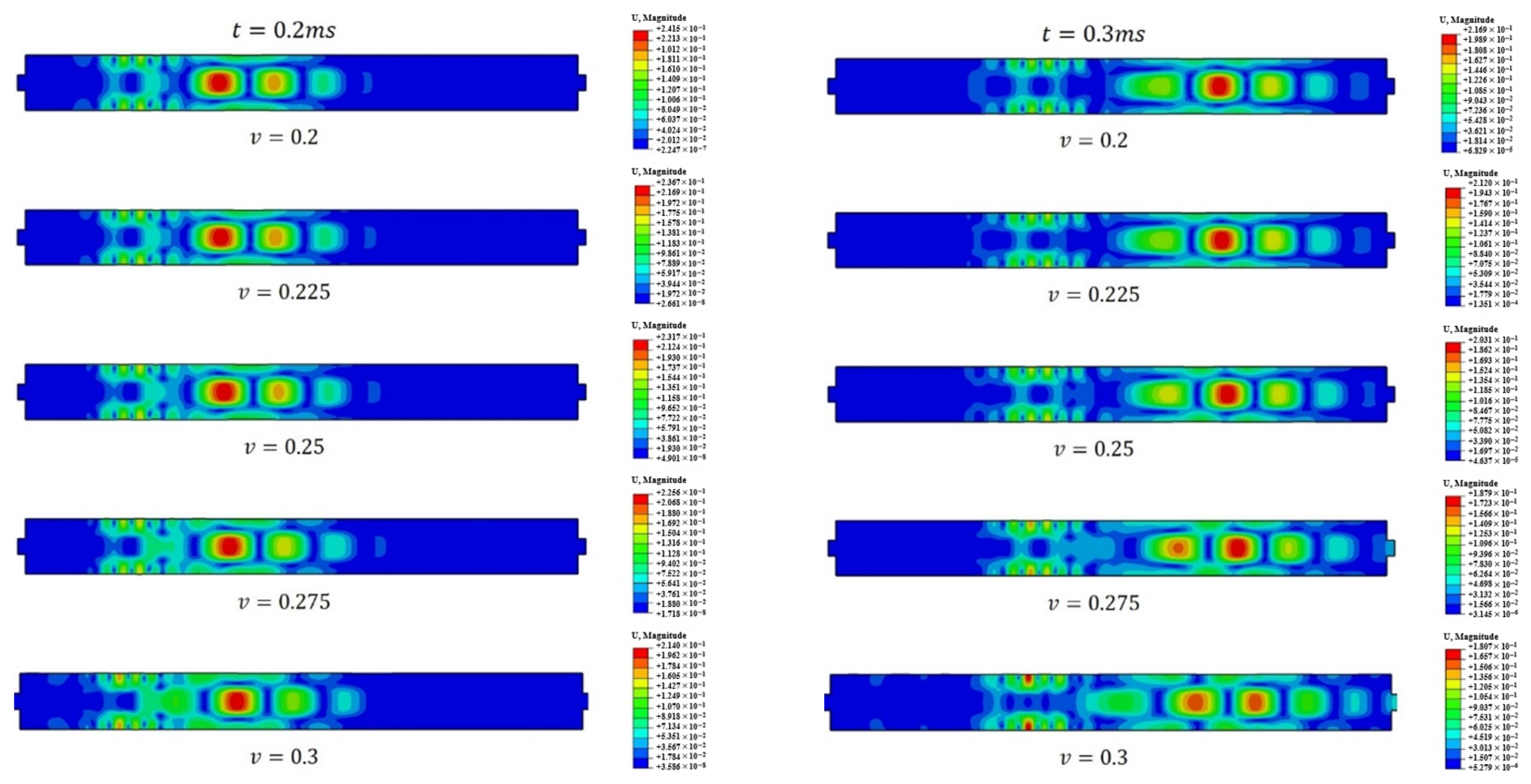

The amplification of the first received wave in

Figure 16 reveals that variations in the Poisson’s ratio lead to noticeable differences in the waveform characteristics of the guided waves. This indicates that changes in the Poisson’s ratio of the anchorage medium influence guided wave propagation behavior. By calculating the relationships between Poisson’s ratio and guided wave velocity and attenuation, it is evident from

Figure 17 that both the wave velocity and amplitude increase with the increasing Poisson’s ratio. This trend becomes more pronounced within

v = 0.25~0.3. The reason for this behavior is that higher Poisson’s ratios promote the greater diffusion and dispersion of guided waves within the anchorage model. This phenomenon is further illustrated and verified by the displacement cloud maps shown in

Figure 18.

Figure 18 shows the displacement cloud maps at 0.2 ms and 0.3 ms for models with different Poisson’s ratios for the anchorage medium. At

t = 0.2 ms, the guided wave has propagated to the midsection of the bolt. In the first half of the bolt, the distribution characteristics of the guided wave remain relatively consistent across different models. However, in the second half, a clear trend emerges: as the Poisson’s ratio of the anchorage medium increases, diffusion and dispersion within the bolt anchorage structure become more pronounced. Correspondingly, the main displacement amplitudes in the cloud maps decrease with the increasing Poisson’s ratio. At

t = 0.3 ms, when the guided wave reaches the receiver end, the displacement distribution in the model with a lower Poisson’s ratio of

v1 = 0.2 is more concentrated compared to that in the model with a higher Poisson’s ratio of

v5 = 0.3. This demonstrates that higher Poisson’s ratios lead to the more significant diffusion and dispersion of guided waves, which is the primary cause of increased attenuation.

4.2. Effect of Bolt Material Parameters on the Propagation Characteristics of Guided Waves

The material parameters of the bolts themselves also influence the propagation characteristics of guided waves. Using finite element simulations, a bolt anchorage model was developed to investigate the effects of these parameters. By varying the material properties of the bolt while keeping all other parameters constant, their impact on wave velocity, attenuation, and the inhomogeneous distribution of guided waves across the bolt cross-section was systematically analyzed.

4.2.1. Effect of Bolt Density on Guided Wave Propagation Characteristics

Keeping other basic parameters unchanged, the density of the bolt (

ρ1 = 2050 kg/m

3,

ρ2 = 2250 kg/m

3,

ρ3 = 2450 kg/m

3,

ρ4 = 2650 kg/m

3) is varied. The received wave of the bolt anchorage model with different bolt densities is obtained, as shown in

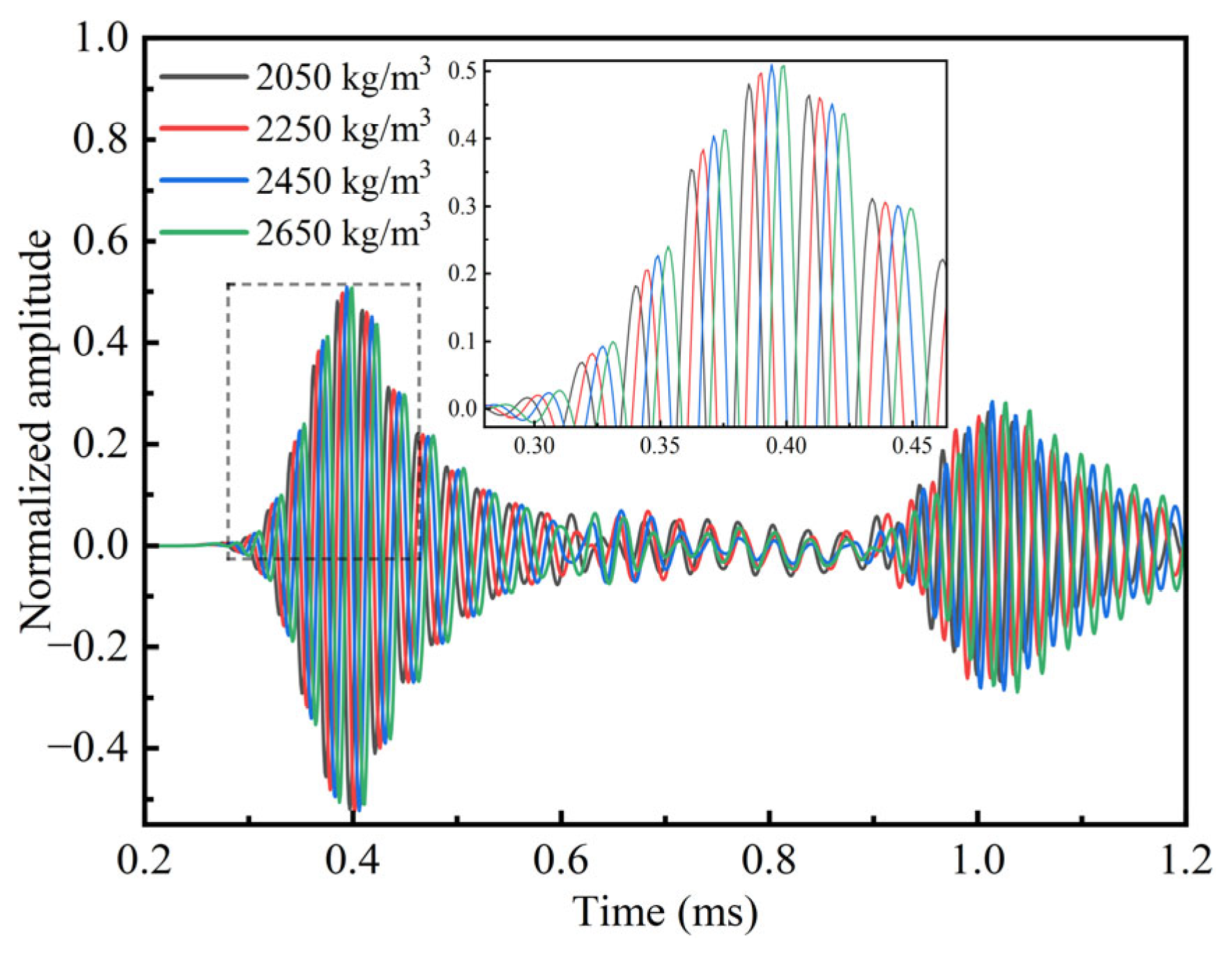

Figure 19.

As observed, two distinct signals were received within the time interval of 0.3 ms to 1.2 ms. The amplification of the first received wave reveals that, with increasing bolt density, the arrival time of the guided wave is gradually delayed, and the signal amplitude increases accordingly. The relationship between the bolt density and guided wave velocity and attenuation is further analyzed in

Figure 20. The results show that both the wave velocity and attenuation decrease progressively as the bolt density increases.

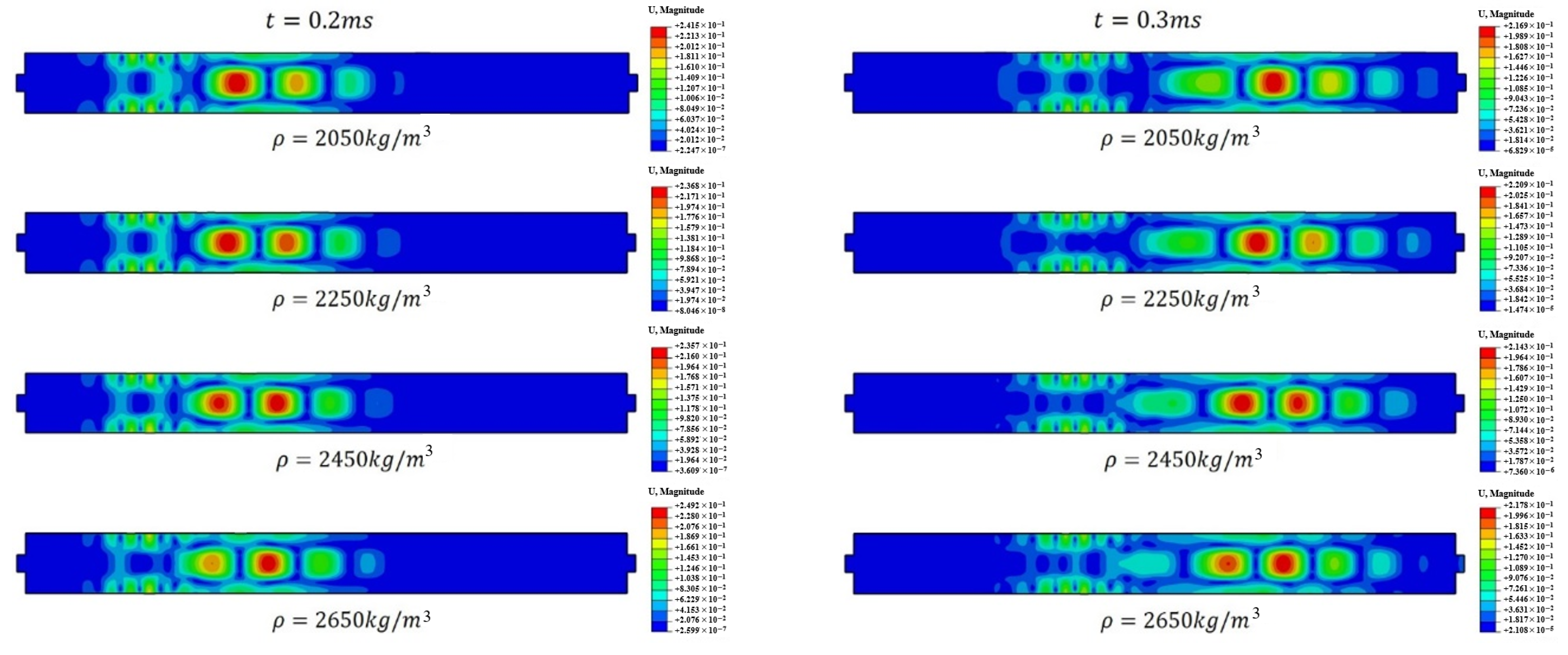

Figure 21 presents the displacement cloud maps at 0.2 ms and 0.3 ms for models with different bolt densities. As shown in the figure, at

t = 0.2 ms, the guided wave propagates to the midsection of the bolt, where the primary displacement occurs, with minor diffusion into the anchorage medium. At this moment, the guided wave in the bolt exhibits a good directivity. As the density of the anchorage medium increases, the distance between the main displacement concentration and the excitation end gradually decreases, indicating a trend of reduced wave velocity under these conditions. At

t = 0.3 ms, the receiver end of the bolt begins to detect the guided wave. The displacement cloud map at this moment shows that, with the decrease in bolt density, the diffusion, internal reflection, and dispersion phenomena in the anchorage structure become more pronounced. Compared with the displacement cloud map at 0.2 ms, the distance between the maximum displacement location and the receiver end increases with the rise in the bolt density, further confirming that the wave velocity decreases as the blot density decreases.

4.2.2. Effect of the Elastic Modulus of the Bolt on the Propagation Characteristics of Guided Waves

Keeping the other basic parameters unchanged, the elastic modulus of the bolt in the axial direction (

E1 = 40 GPa,

E2 = 50 GPa,

E3 = 60 GPa,

E4 = 70 GPa) was varied. The received waves of the bolt anchorage model with different elastic moduli for the bolt are obtained as in

Figure 22.

From the figure, it can be observed that two distinct signals—the first and second received waves—were captured at the bottom of the bolt within the time interval from 0.3 ms to 1.2 ms. The amplified view of the first received wave reveals significant differences in the waveform characteristics across bolt anchorage models with varying elastic moduli. As the elastic modulus of the bolt increases, the time required for the guided wave to reach the receiver end decreases, while the amplitude of the received signal tends to diminish. These effects become even more pronounced in the second received wave, further highlighting the strong influence of the bolt’s elastic modulus on both the velocity and amplitude of the guided wave. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that the bolt serves as the primary medium for guided wave propagation. Variations in its elastic modulus substantially alter the wave behavior. Moreover, as the bolt’s elastic modulus increases, the acoustic impedance mismatch between the bolt and the surrounding anchorage medium also increases, intensifying wave diffusion and dispersion and thereby reducing the amplitude of the received signal. Further analysis, as shown in

Figure 23, demonstrates that both the guided wave velocity and attenuation increase progressively with higher elastic modulus values in the bolt anchorage models. This confirms that the elastic modulus of the bolt plays a critical role in shaping guided wave propagation characteristics.

Figure 24 presents the displacement cloud maps at 0.2 ms and 0.3 ms for models with different bolt elastic moduli. At

t = 0.2 ms, the guided wave has propagated to the midsection of the bolt. At this moment, notable differences in the radial distribution characteristics of the guided wave can be observed. As the elastic modulus of the bolt increases, the phenomena of wave diffusion, internal reflection, and dispersion within the anchorage structure become increasingly pronounced, indicating that bolts with a higher elastic modulus have a more complex impact on guided wave propagation. Additionally, with an increasing elastic modulus, the distance between the main displacement concentration and the excited end becomes larger, suggesting that guided waves travel faster in bolts with a higher stiffness. This is because materials with a higher elastic modulus exhibit better wave propagation capabilities, enabling a more efficient energy transmission.

At t = 0.3 ms, the receiver end of the model begins to detect the guided waves. Similarly to the case at t = 0.2 ms, the displacement cloud maps show that, as the elastic modulus of the bolt increases, the distance between the location of maximum displacement and the receiver end gradually decreases. This indicates an increase in the guided wave propagation velocity with higher elastic moduli. At this stage, the cloud maps further reveal that bolts with a higher elastic modulus exhibit a more pronounced wave diffusion, internal reflection, and dispersion within the anchorage structure. These effects are the primary reasons for the observed reduction in the waveform amplitude. This phenomenon can be attributed to the influence of material stiffness on the guided wave behavior. Although materials with a high elastic modulus support faster wave propagation due to their superior energy transmission properties, they are also more susceptible to dispersion and energy scattering. As a result, greater wave diffusion and internal reflections occur, leading to energy loss and a reduced signal amplitude at the receiver end.

4.2.3. Effect of Poisson’s Ratio of Bolts on the Propagation Characteristics of Guided Waves

The Poisson’s ratio was changed along the axial direction of the bolt (

v1 = 0.2,

v2 = 0.25,

v3 = 0.3). The received waves of the bolt anchorage model with different Poisson’s ratios for the bolts are obtained as in

Figure 25.

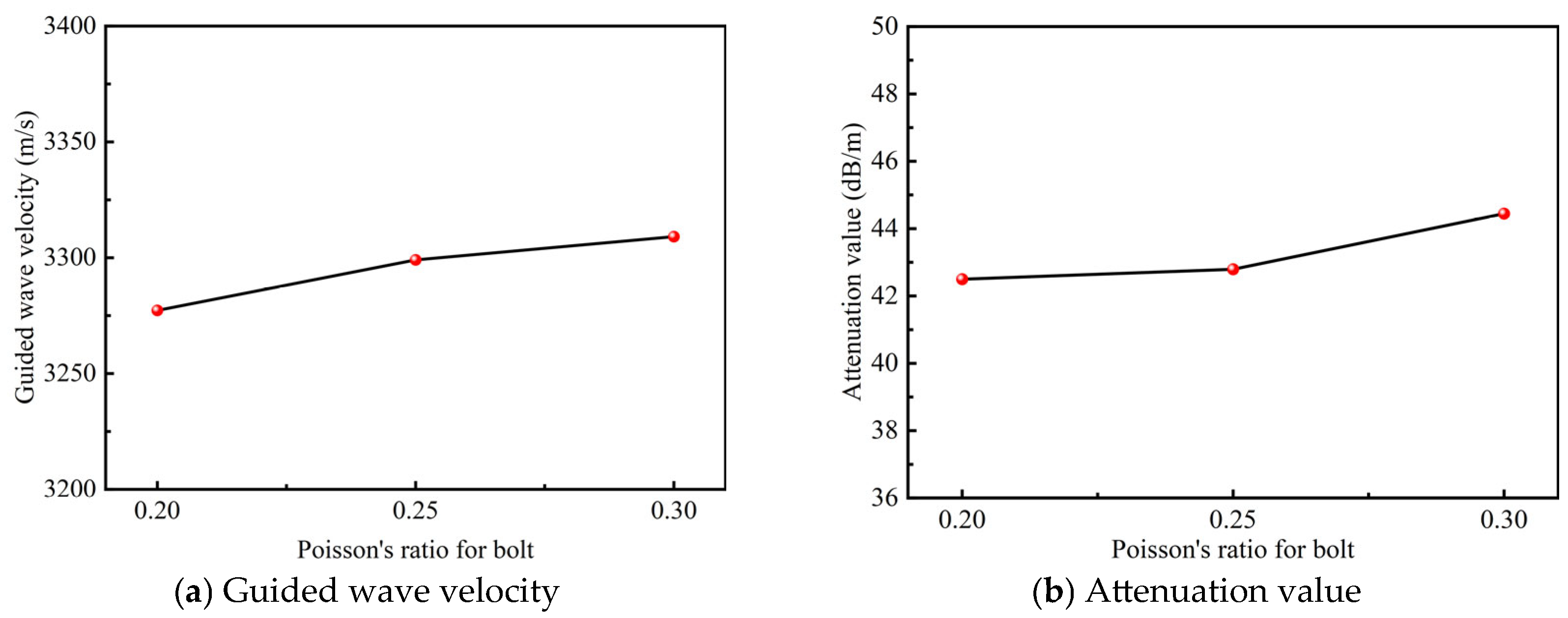

From the figure, it can be observed that, in the BFRP bolt anchorage model, variations in the Poisson’s ratio of the bolt have a relatively minor effect on the propagation of guided waves. The amplified analysis of the received waveforms shows a slight decreasing trend in the wave amplitude as the Poisson’s ratio increases. Although the difference in amplitude is not particularly significant in the first received wave, the second received wave more clearly confirms this trend. These results suggest that, while the Poisson’s ratio has some influence, its impact on the guided wave amplitude and propagation characteristics is comparatively limited.

Based on the guided wave velocity and attenuation formulas, the relationship between the Poisson’s ratio of the bolt and the guided wave velocity and attenuation was calculated, as shown in

Figure 26. The results indicate that, in the bolt anchorage models with varying Poisson’s ratios, the guided wave velocity gradually increases with the increase in the Poisson’s ratio. Conversely, the attenuation of the guided wave tends to decrease as the Poisson’s ratio increases. This suggests that a higher Poisson’s ratio enhances wave propagation efficiency while reducing energy loss during transmission.

Figure 27 shows the displacement cloud maps at 0.2 ms and 0.3 ms for bolt models with different Poisson’s ratios. As observed in the maps at

t = 0.2 ms, the guided wave has propagated to the midsection of the bolt. While the distribution characteristics of the main displacements in the first half of the bolt remain relatively consistent across different Poisson’s ratios, notable differences emerge in the second half. Specifically, as the Poisson’s ratio increases, the displacement distribution changes significantly, with more pronounced diffusion and dispersion phenomena occurring within the anchorage structure. At

t = 0.3 ms, the receiver end begins to register the guided waves. Similarly to the behavior observed at

t = 0.2 ms, the distance between the region of maximum displacement and the receiver end decreases as the Poisson’s ratio increases, indicating an increase in wave propagation velocity. Moreover, the displacement maps reveal that higher Poisson’s ratios result in intensified wave diffusion, internal reflection, and dispersion. These effects lead to a greater energy loss during wave propagation, which in turn causes a noticeable reduction in the amplitude of the received waveform.

4.3. Effect of De-Bonding Defects on the Propagation Characteristics of Guided Waves

The propagation characteristics of guided waves in bolts are influenced not only by the parameters of the anchorage medium and the bolt itself, but also by the presence, location, and extent of de-bonding defects. In this study, finite element simulations were employed to investigate the impact of such defects on guided wave behavior. By varying the position and length of the de-bonding defects, their effects on guided wave velocity, attenuation, and waveform characteristics were systematically analyzed.

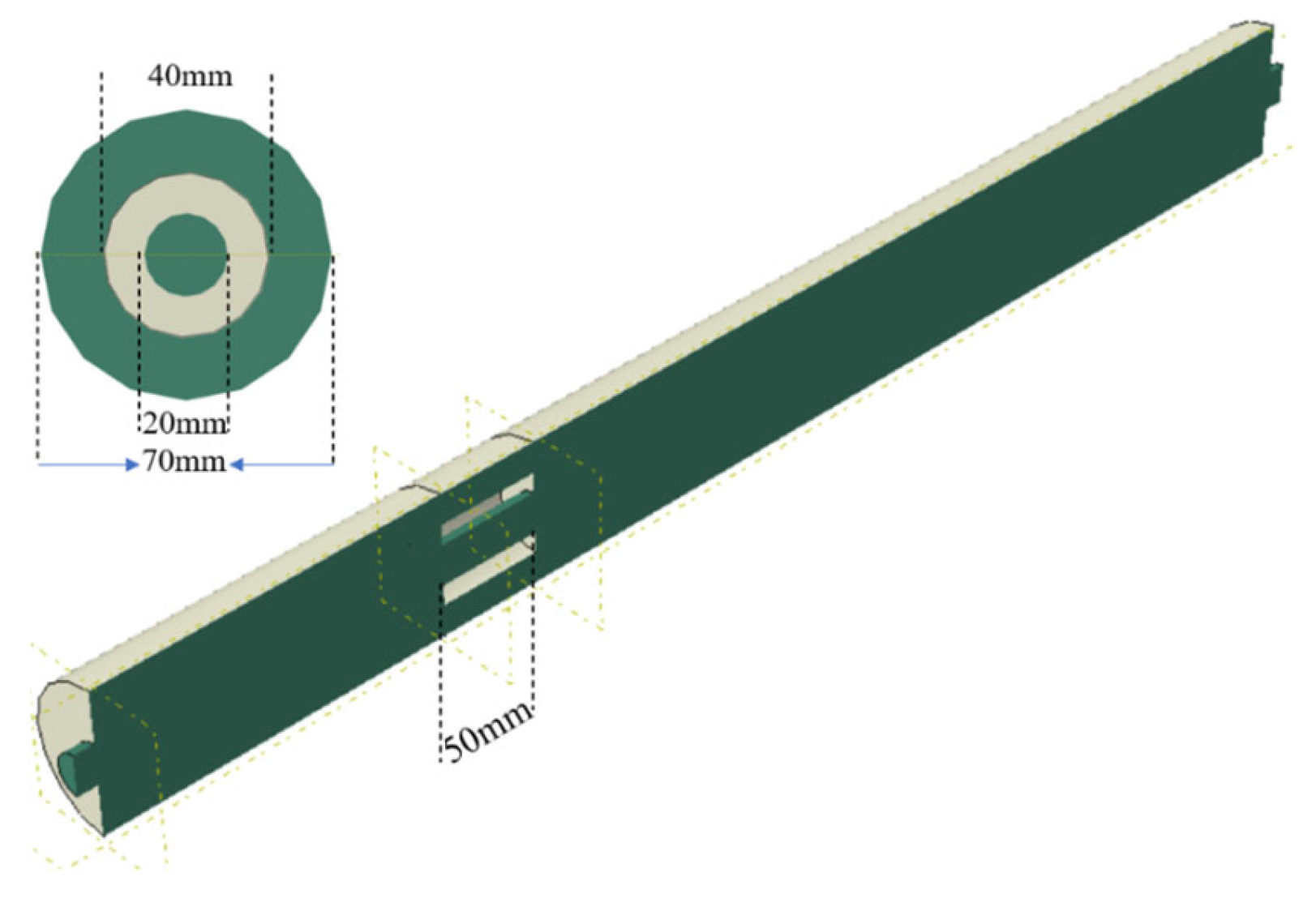

For the bolt anchorage models with varying de-bonding defect locations, a de-bonding layer with a thickness of 10 mm and a length of 50 mm was introduced circumferentially around the bolt at positions corresponding to 2/7, 3/7, 4/7, and 5/7 of the total model length. For models with different defect lengths, de-bonding layers of 10 mm thickness and lengths of 150 mm and 250 mm were introduced around the bolt at 2/7 of the model length. The schematic diagrams of the de-bonding defect location model and the varying defect length models are shown in

Figure 28 and

Figure 29, respectively.

4.3.1. Effect of Defect Location the Propagation Characteristics of Guided Wave

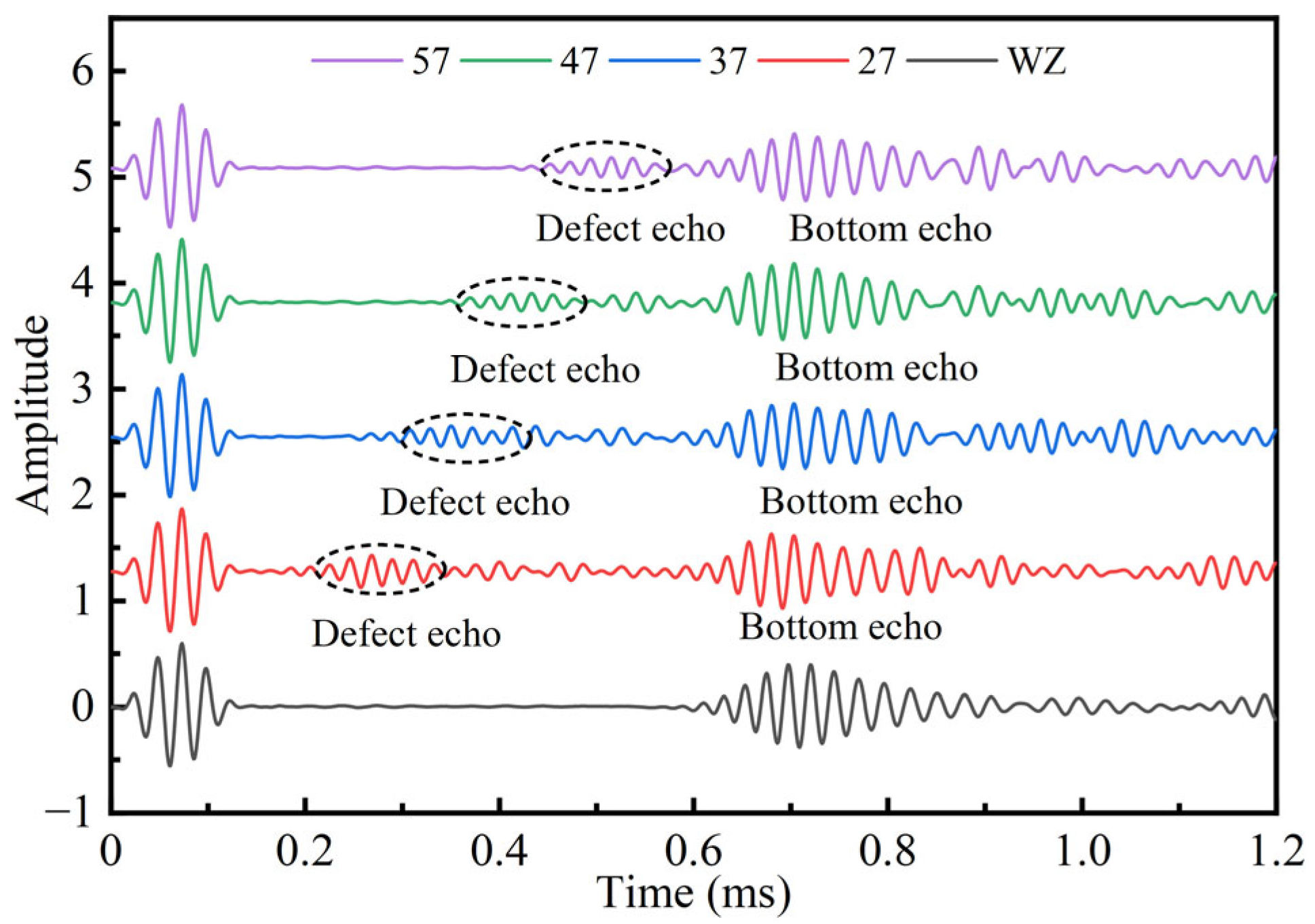

Keeping all other parameters constant, the defect location was varied along the bolt length at positions corresponding to 2/7, 3/7, 4/7, and 5/7, and the received waveforms for each de-bonding model were obtained, as shown in

Figure 30. From the figure, it is observed that, in the defect-free bolt anchorage model (WZ), two primary signals are detected at the excited end within the time window of 0 ms to 1.2 ms—corresponding to the initial excited wave and the bottom-end reflection. In contrast, in the presence of de-bonding defects, three distinct signals are observed: the excited wave, the defect echo, and the bottom echo.

A comparison of the four defect models reveals a clear relationship between the defect location and the echo waveform characteristics. Specifically, as the defect location moves further from the excited end, the arrival time of the defect echo at the excited end increases accordingly. This indicates that the location of de-bonding defects within the anchorage structure can be effectively identified using guided wave testing. Notably, the defect echoes for all four models fall approximately along a straight diagonal line, suggesting a strong linear correlation between defect echo time and defect location.

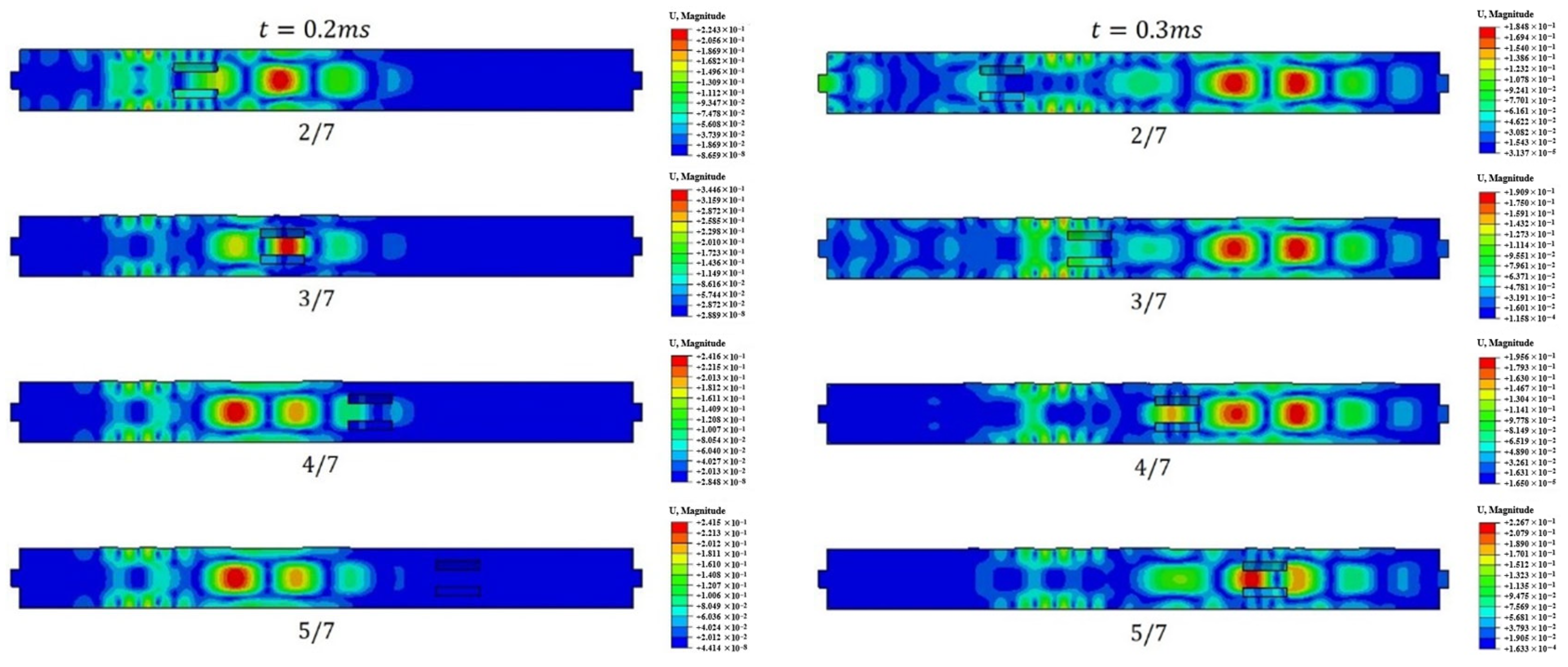

Figure 31 presents the displacement cloud maps at 0.2 ms and 0.3 ms for different defect location models. At

t = 0.2 ms, the guided wave propagates to the middle section of the bolt, with the maximum displacement observed in the region between the 3/7 and 4/7 positions. During this stage, the wave primarily travels along the bolt, accompanied by energy diffusion and dispersion. Among the four defect location models, the maximum displacement follows the trend 3/7 > 2/7, 4/7, and 5/7. This indicates that the guided wave experiences a lower attenuation when propagating through a free bolt compared to a fully bonded bolt anchorage structure. The presence of de-bonding defects significantly influences the propagation velocity of the guided wave.

At t = 0.3 ms, the guided wave approaches the receiver end, and the maximum displacement is located between the 4/7 defect and the receiver end. Similarly to the trend at t = 0.2 ms, the position of maximum displacement continues to shift toward the receiver end as the wave propagates. The displacement amplitude at this moment follows the order 5/7 > 2/7, 3/7, and 4/7. Additionally, for the 2/7 and 3/7 defect cases, the corresponding defect echoes are detected at the excited end of the bolt. This confirms that the defect location has a direct and significant impact on the waveform characteristics of the received signal.

4.3.2. Effect of Defect Length on the Propagation Characteristics of Guided Waves

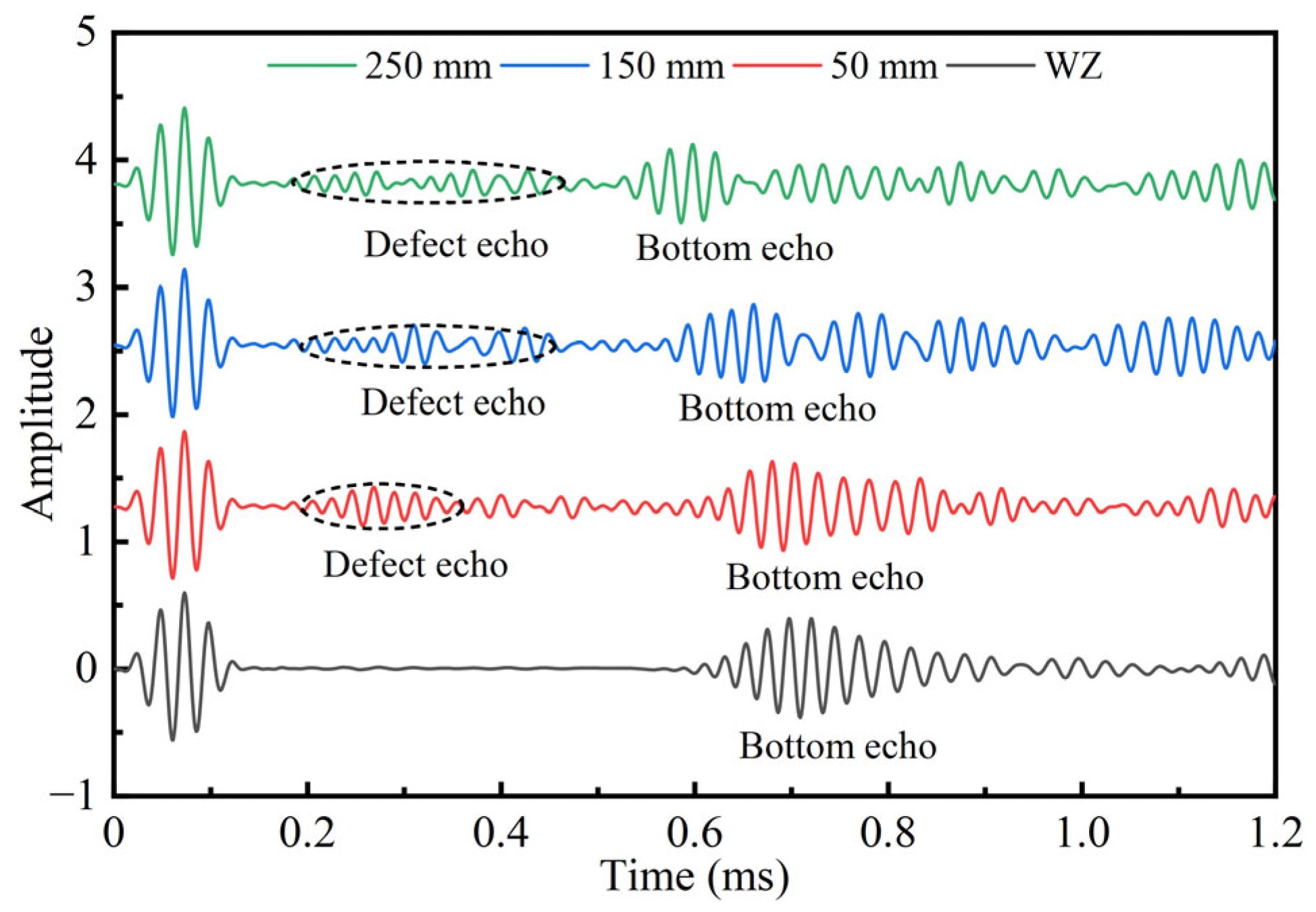

Keeping other parameters constant and varying the length of de-bonding defects (50 mm, 150 mm and 250 mm), the received waves of the bolt anchorage model with different defect lengths are obtained as in

Figure 32.

From the figure, it can be observed that, in the defect-free bolt anchorage model, two primary signals are received within the time interval of 0 ms to 1.2 ms—namely, the excited wave and the bottom echo. In contrast, for the models with de-bonding defects, three distinct signals are recorded in the same time interval: the excited wave, the defect echo, and the bottom echo. By comparing the models with different defect lengths, a clear relationship between defect length and waveform characteristics is evident. As the defect length increases, the arrival time of the defect echo at the excited end also increases. This indicates that the guided wave signal is highly sensitive to the length of de-bonding defects, and the approximate extent of internal de-bonding within the anchorage system can be inferred using guided wave detection techniques. It is also noteworthy that, with increasing defect length, the arrival time of the bottom reflection at the excited end slightly decreases. This is attributed to the fact that the bolt behaves more like a free bar within the de-bonded region, where wave propagation is subject to reduced diffusion and dispersion effects, resulting in a relatively higher wave velocity.

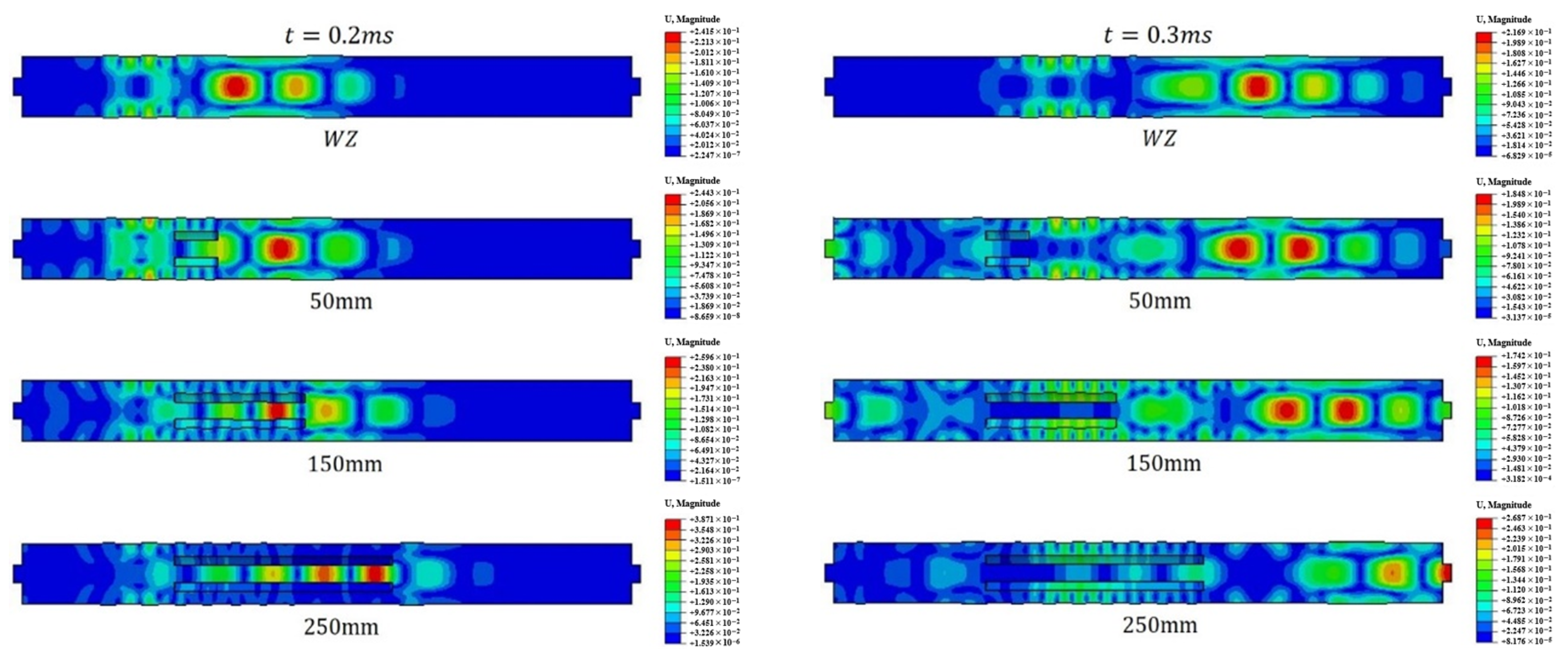

Figure 33 presents the displacement cloud maps at 0.2 ms and 0.3 ms for models with different de-bonding defect lengths. At

t = 0.2 ms, the guided wave has propagated to the middle section of the bolt. The radial distribution of displacements within the bolt anchorage structure exhibits significant variation. As the defect length increases, the concentration zone of the main displacement moves closer to the receiving end, indicating a higher wave velocity. At

t = 0.3 ms, the guided wave begins to reach the receiver end. Similarly to the observations at 0.2 ms, the location of the maximum displacement shifts closer to the receiver end as the defect length increases, further confirming the increase in wave velocity. Additionally, the maximum displacement cloud maps reveal that longer defects lead to more pronounced wave reflections within the anchorage structure, which is the primary cause of the observed differences in the waveforms at the excited end.

5. Conclusions

Based on experimental testing and numerical simulations, this study investigates the optimal excited wave for guided wave propagation in BFRP bolt anchorage structures. Subsequently, numerical simulations were conducted by varying the material parameters of the BFRP bolts and anchorage medium, as well as the locations and lengths of de-bonding defects. The study reveals the propagation laws of guided waves in BFRP bolt anchorage systems, including dispersion, attenuation, wave velocity, inhomogeneous radial distribution, and echo response characteristics. The following conclusions are obtained:

- (1)

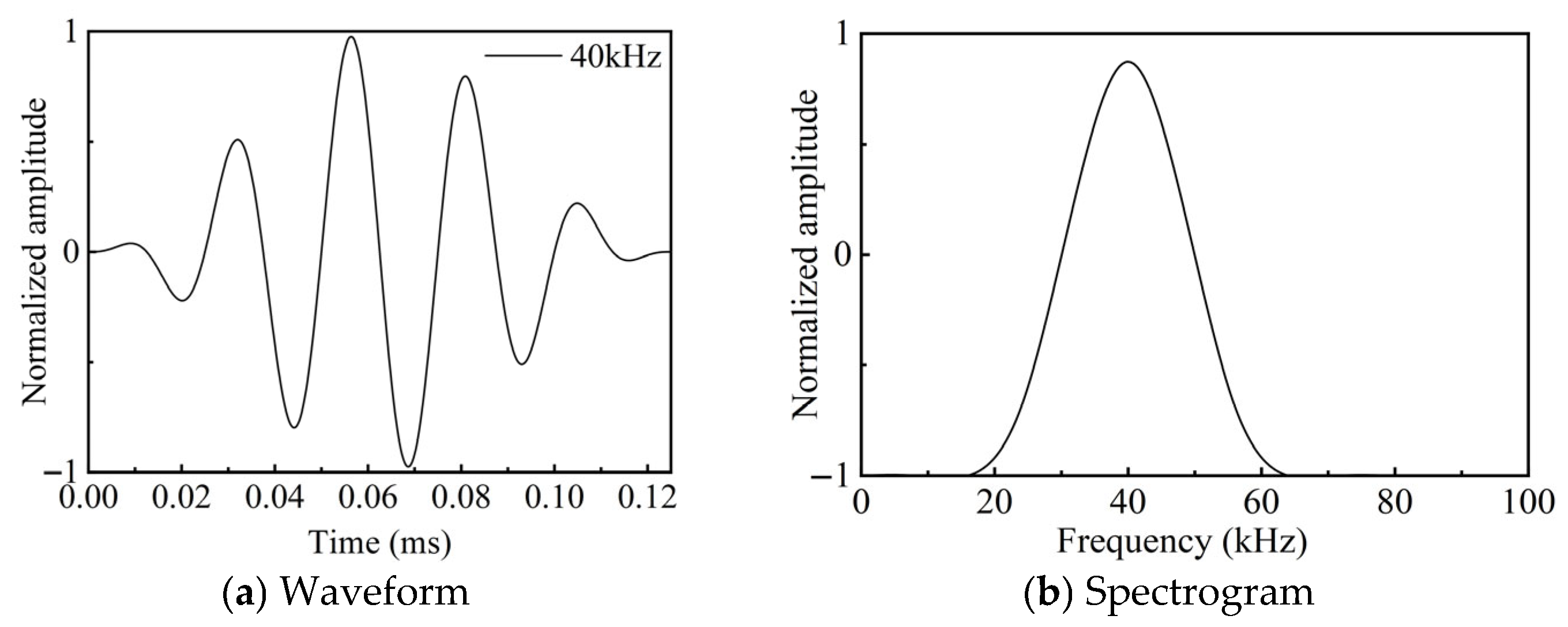

Changes in the excitation frequency will cause corresponding changes in the waveform structure, and the amplitude of the received wave will generally decrease with the increase in the excitation frequency. In the frequency band of 35~50 kHz, the signal wave packet corresponding to the received wave has a more ideal shape, while, in the frequency band of 60~100 kHz, the attenuation of the guided wave in the propagation process increases and the dispersion phenomenon is serious. Among them, the peak-to-peak value of the received wave signal at a 40 kHz excitation frequency reaches a maximum of 0.31 V, and the bottom reflection is the clearest and is most suitable for the guided wave testing of BFRP bolt anchorage structure frequency.

- (2)

The propagation characteristics of the guided wave in the bolt are affected by the parameters of the anchorage medium. With the increase in the density of the anchorage medium, the wave velocity decreases, the attenuation decreases, and the inhomogeneous distribution within the model is intensified; with the increase in the modulus of elasticity of the anchorage medium, the amplitude of the received wave decreases and the attenuation increases; with the increase in the Poisson’s ratio of the anchorage medium, the guided wave velocity and the attenuation appear to have a tendency to increase.

- (3)

The propagation characteristics of the guided wave in the bolt are affected by the material parameters of the bolt. With the increase in the density of the bolt, the guided wave velocity and attenuation appear to decrease; with the increase in the modulus of elasticity of the bolt, the guided wave velocity and attenuation appear to increase; with the increase in the Poisson’s ratio of the bolt, the guided wave velocity and attenuation appear to have a small increase in their trends.

- (4)

The propagation characteristics of guided waves in the bolt are also affected by the location and length of the de-bonding defect, and the defect echo time is linearly related to the defect location. And, as the defect length increases, the guided wave velocity increases and the amplitude decreases.

Despite the encouraging results obtained in this study, future work will focus on extending the experimental program to include multiple anchorage configurations and material parameters for further validation. Moreover, the potential influence of environmental and structural temperature variations on material properties and guided wave propagation characteristics will be investigated. Based on the parameter sensitivity and propagation characteristics identified in this study, future research may also explore the construction of objective functions and the integration of swarm intelligence optimization algorithms for guided wave-based inspection. These efforts are expected to further improve the applicability of the proposed method in structural health monitoring.