Biophilic Design Interventions and Properties: A Scoping Review and Decision-Support Framework for Restorative and Human-Centered Buildings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Methodology

2.1. Scope and Objectives

2.2. Keyword Development and Search Strategy

2.3. Search Process and Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Extraction and Analysis Framework

- Within-category analysis identified recurring design properties and associated human responses for each intervention type, informing preliminary guidelines.

- Cross-category analysis examined studies comparing multiple interventions or combining them, highlighting relative restorative potential and synergistic effects.

3. Results

3.1. Within-Category Analysis

3.1.1. Green Wall

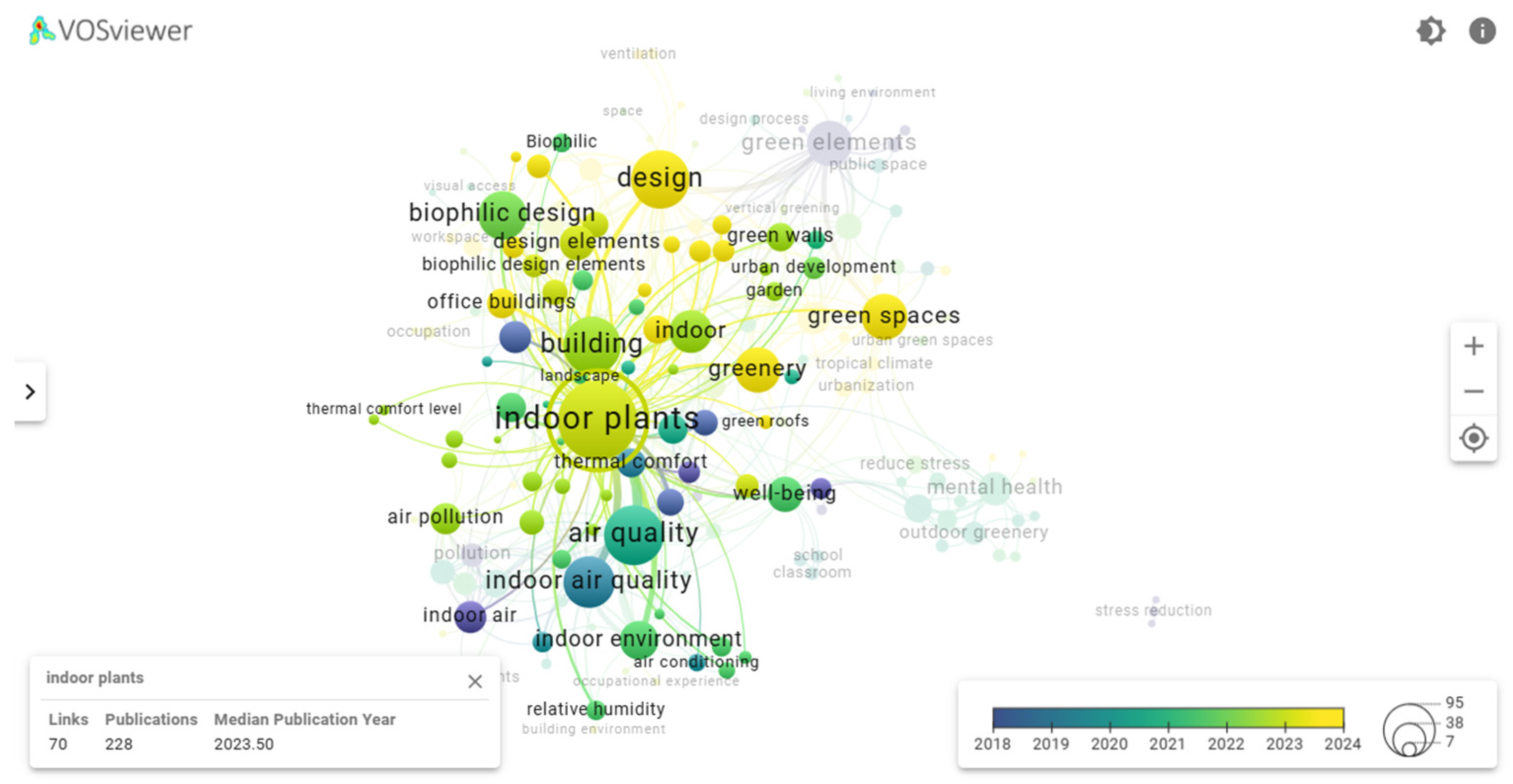

3.1.2. Indoor Plants

3.1.3. Window View

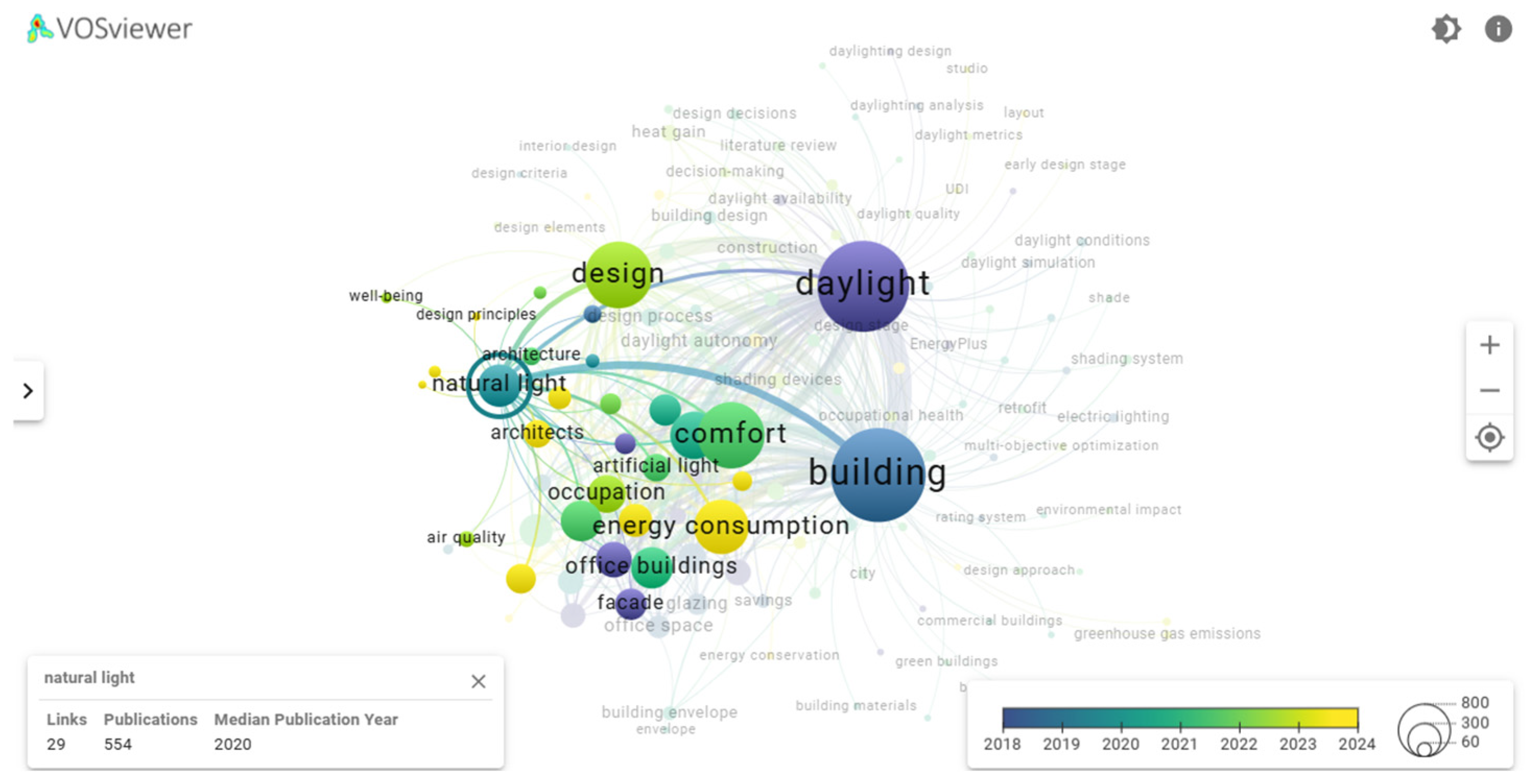

3.1.4. Natural Light

3.1.5. Natural Materials

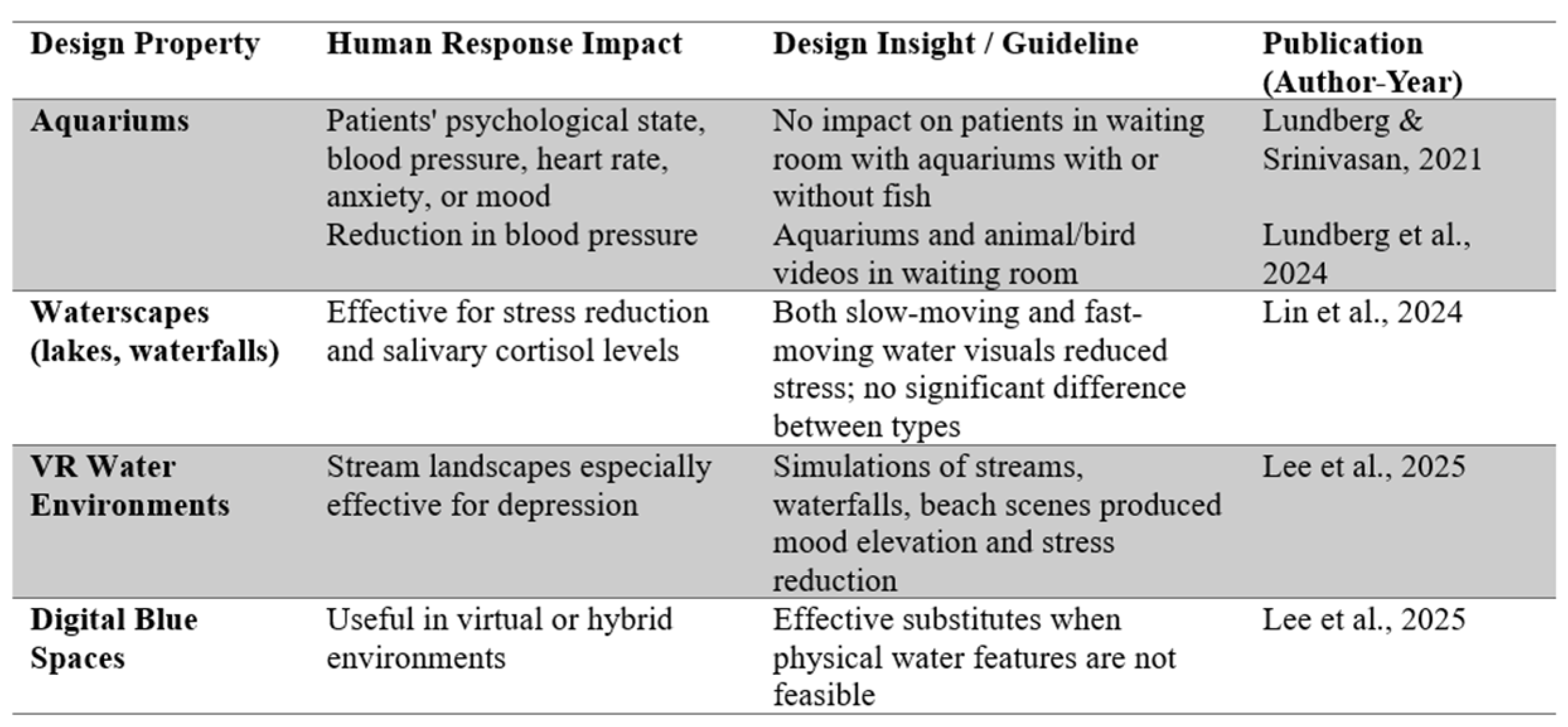

3.1.6. Water Features

3.1.7. Nature-Inspired Visual References

3.2. Cross-Category Analysis

3.2.1. Comparative Studies

3.2.2. Combination Studies

4. Discussions

4.1. General Design Guidelines for Biophilic Interventions

4.1.1. Indoor Green Coverage Ratio (IGCR)

- 20–30% IGCR: In most interiors; already yields strong restorative effects.

- 30–40% IGCR: For relaxation- or restoration-focused spaces (e.g., lounges, wellness rooms, green atriums).

- >40% IGCR: For specialty immersive spaces (e.g., botanical centers, exhibitions) and generally impractical for everyday environments.

4.1.2. Color, Pattern and Texture

- Use naturalistic green hues with tonal variation to mimic real foliage.

- Incorporate organic textures (wood grain, leaf veins, stone surfaces) to enhance engagement.

- Integrate fractal or branching patterns for visual complexity without overload.

- Leverage contrasts strategically, placing natural elements against neutral/complementary backgrounds.

- Avoid flat, uniform surfaces or unnatural colors that reduce fascination.

4.1.3. Spatial Composition and Location

- Prioritize high-visibility, direct-sightline locations in primary activity areas.

- Use diverse but coherent arrangements instead of uniform placement.

- Pair large features with smaller distributed elements.

- Integrate interventions functionally (e.g., green partitions, planter-benches).

- Place in high-dwell areas for maximum exposure.

- Apply perceptual contrast to boost salience and attention capture.

4.1.4. Combination of Biophilic Interventions

4.1.5. Virtual Biophilic Design

4.1.6. Duration of Exposure

- Short, intense exposures (e.g., VR relaxation rooms, waiting areas) should maximize sensory richness, spatial prominence, and visual accessibility of biophilic features.

- Longer, ambient exposures (e.g., offices, classrooms, hospital wards) should focus on integrating natural elements into the user’s visual and functional field over time, considering their goals and activities.

4.1.7. Demographic Variability

4.2. Biophilic Intensity Matrix (BIMx)

5. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Author(s), Year | Shortened Title | Journal, Link (All Accessed on 25 July 2025) |

|---|---|---|

| Altaf et al., 2025 | Impact of Windows, Materials, and Nature Representations on Well-Being | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2025.113147 |

| Yin et al., 2020 | Effects of Biophilic Indoor Environments on Stress and Anxiety Recovery | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.105427 |

| Holland et al., 2021 | Measuring Nature Contact: A Narrative Review | https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084092 |

| Yin et al., 2022 | Stress Recovery in Virtual Desert and Green Environments | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101775 |

| Cox et al., 2017 | Neighborhood Nature Exposure and Mental Health Benefits | https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biw173 |

| Jiang et al., 2015 | Tree Cover Density and Landscape Preference | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.02.018 |

| Douglas et al., 2022 | Built Environment Features and Human Well-Being: A Mixed-Methods Study | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109516 |

| Kort et al., 2006 | Restorative Effects of Virtual Trees | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2006.09.001 |

| Altaf et al., 2022 | Crowdsourced Studies of Architectural Design and Well-Being | https://doi.org/10.3389/frsc.2022.780376 |

| Bianchi et al., 2023 | Indoor Nature, Solidarity, and Group Identity in Remote Work | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2023.110909 |

| Yin et al., 2018 | Physiological and Cognitive Responses to Biophilic Indoor Environments | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2018.01.006 |

| Jiang et al., 2014 | A dose of nature: Tree cover, stress reduction, and gender differences | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.08.005 |

| Ramanpong et al., 2024 | Effects of Forest Density on Physiological and Psychological Responses | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tfp.2024.100551 |

| Sun et al., 2024 | Effects of Classroom Color Tones on Student Emotions | https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14103309 |

| Choi et al., 2016 | Physiological and Psychological Responses to Indoor Greenness | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2016.08.002 |

References

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razak, M.A.W.A.; Othman, N.; Nazir, N.N.M. Connecting People with Nature: Urban Park and Human Well-being. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 222, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama, N.; Korpela, K.; Lee, J.; Morikawa, T.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Park, B.-J.; Li, Q.; Tyrväinen, L.; Miyazaki, Y.; Kagawa, T. Emotional, Restorative and Vitalizing Effects of Forest and Urban Environments at Four Sites in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 7207–7230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological effects of forest-related visual, olfactory, and combined stimuli on humans: An additive combined effect. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 44, 126437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.M.; Fayek, M.B.; Hemayed, E.E. Human-inspired features for natural scene classification. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2013, 34, 1525–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.P.; Pahl, S.; Ashbullby, K.; Herbert, S.; Depledge, M.H. Feelings of restoration from recent nature visits. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 35, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepeis, N.E.; Nelson, W.C.; Ott, W.R.; Robinson, J.P.; Tsang, A.M.; Switzer, P.; Behar, J.V.; Hern, S.C.; Engelmann, W.H. The National Human Activity Pattern Survey (NHAPS): A resource for assessing exposure to environmental pollutants. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2001, 11, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, M. How might contact with nature promote human health? Promising mechanisms and a possible central pathway. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Mitchell, R.; de Vries, S.; Frumkin, H. Nature and Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, W.D.; Clancy, J. 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design: Improving Health & Well-Being in the Built Environment; Terrapin Bright Green: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, T.; Birrell, C. Are Biophilic-Designed Site Office Buildings Linked to Health Benefits and High Performing Occupants? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 12204–12222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elantary, A.R. Biophilic Design in Office Buildings: A Salutogenic Approach to Enhancing Well-being in the Built Environment. Proc. Int. Conf. Contemp. Aff. Archit. Urban.-ICCAUA 2024, 7, 1361–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, K.; Pieterse, M.E.; Pruyn, A. Stress-reducing effects of indoor plants in the built healthcare environment: The mediating role of perceived attractiveness. Prev. Med. 2008, 47, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Zimring, C.; Zhu, X.; DuBose, J.; Seo, H.-B.; Choi, Y.-S.; Quan, X.; Joseph, A. A Review of the Research Literature on Evidence-Based Healthcare Design. HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2008, 1, 61–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadvand, P.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Esnaola, M.; Forns, J.; Basagaña, X.; Alvarez-Pedrerol, M.; Rivas, I.; López-Vicente, M.; Pascual, M.D.C.; Su, J.; et al. Green spaces and cognitive development in primary schoolchildren. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 7937–7942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Yuan, J.; Arfaei, N.; Catalano, P.J.; Allen, J.G.; Spengler, J.D. Effects of biophilic indoor environment on stress and anxiety recovery: A between-subjects experiment in virtual reality. Environ. Int. 2020, 136, 105427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaoxue, S.; Huang, X. Promoting stress and anxiety recovery in older adults: Assessing the therapeutic influence of biophilic green walls and outdoor view. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1352611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Liu, H. Physiological and psychological effects of exposure to different types and numbers of biophilic vegetable walls in small spaces. Build. Environ. 2022, 225, 109645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeom, S.; Kim, H.; Hong, T.; Ji, C.; Lee, D. Emotional impact, task performance and task load of green walls exposure in a virtual environment. Indoor Air 2022, 32, e12936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedghikhanshir, A.; Zhu, Y.; Beck, M.R.; Jafari, A. Exploring the impact of green wall and its size on restoration effect and stress recovery using immersive virtual environments. Build. Environ. 2024, 262, 111844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedghikhanshir, A.; Zhu, Y.; Beck, M.R.; Jafari, A. Exploring Green Wall Sizes as a Visual Property Affecting Restoration Effect and Stress Recovery in a Virtual Office Room. In Proceedings of the Computing in Civil Engineering 2023, Corvallis, OR, USA, 25–28 June 2023; pp. 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedghikhanshir, A.; Zhu, Y.; Beck, M.R.; Jafari, A. The Impact of Visual Stimuli and Properties on Restorative Effect and Human Stress: A Literature Review. Buildings 2022, 12, 1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R.; Heerwagen, J.; Mador, M. Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Institute, I.W.B. WELL Building Standard v2. Available online: https://v2.wellcertified.com/v/en/overview (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC). LEED v4.1 Building Design and Construction (BD+C) Rating System. Available online: https://www.usgbc.org/leed/v41 (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Data Sourced from Dimensions, an Inter-Linked Research Information System Provided by Digital Science. Available online: https://www.dimensions.ai (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Digital Science. Dimensions: Landscape & Discovery. Digital Science. Available online: https://www.dimensions.ai/products/all-products/landscape-discovery/33 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Yeom, S.; Kim, H.; Hong, T. Psychological and physiological effects of a green wall on occupants: A cross-over study in virtual reality. Build. Environ. 2021, 204, 108134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedghikhanshir, A.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Harmon, B. Exploring the Impact of Green Walls on Occupant Thermal State in Immersive Virtual Environment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Hu, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Li, D.; Wu, L. Adding Green to Architectures: Empirical Research Based on Indoor Vertical Greening of the Emotional Promotion on Adolescents. Buildings 2024, 14, 2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, A.A.F. Interior Green Walls and Its Employment in Sustainable Commercial Spaces. Int. J. Adv. Res. Plan. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 2, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-Y.; Cho, S.-I. A Study on the Vertical Garden Design for Indoor Space—Focused on Green Wall in Lobby Space. Korean Inst. Inter. Des. J. 2013, 22, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-R.; Ahn, T.-M. Cafeteria Users’ Preference for an Indoor Green-wall in a University Dining Hall. J. Korean Inst. Landsc. Archit. 2015, 43, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmey, E.M.; Gast, G.; Wick, S.R.; Vo, T.U.H.; McLaughlin, M.A.; Osika, J.; Slocum, B.; Sawicki, N.; Mehta, K. EcoRealms: Improving Well-being and Enhancing Productivity Through Incorporating Nature into the Workplace. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference (GHTC), Santa Clara, CA, USA, 8–11 September 2022; pp. 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University, A.S.; Assem, A.; Hassan, D.K. Biophilia in the workplace: A pilot project for a living wall using an interactive parametric design approach. Archit. Eng. 2024, 9, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedghikhanshir, A.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Beck, M.R.; Jafari, A. Comparing the Restoration Effect and Stress Recovery in Real and Virtual Environments with a Green Wall. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslehian, A.S.; Roös, P.B.; Gaekwad, J.S.; Galen, L.V. Potential risks and beneficial impacts of using indoor plants in the biophilic design of healthcare facilities: A scoping review. Build. Environ. 2023, 233, 110057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydogan, A.; Cerone, R. Review of the effects of plants on indoor environments. Indoor Built Environ. 2019, 30, 442–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welagedara, K.D.C.M.; Hettiarachchi, A.A. A study on the impact of greenery in building interiors on the psychological well-being of occupants: An experimental study with special reference to Personalized Residential Spaces of University Students in Sri Lanka. In Proceedings of the 16th International Research Conference—FARU 2023, Moratuwa, Sri Lanka, 1–2 December 2023; pp. 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.-T. Effects of Indoor Plants on the Physical Environment with Respect to Distance and Green Coverage Ratio. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, C.; Akgün, İ.; Olgun, R. Evaluation of the Effects of Indoor Plant Preferences Used in Offices, Maintenance Opportunities and Air Quality: A Case of Akdeniz University. Turk. J. Agric.—Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 8, 702–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.-A.; Kim, S.-O.; Park, S.-A. Real Foliage Plants as Visual Stimuli to Improve Concentration and Attention in Elementary Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibata, S.; Suzuki, N. Effects of the Foliage Plant on Task Performance and Mood. J. Environ. Psychol. 2002, 22, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hähn, N.; Essah, E.; Blanusa, T. Biophilic design and office planting: A case study of effects on perceived health, well-being and performance metrics in the workplace. Intell. Build. Int. 2021, 13, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasoğlu, M.S.; Kahramanoğlu, İ. Effects of indoor plants on perceptions about indoor air quality and subjective well-being. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 106, 112563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, S.; Tokuhiro, K.; Ikeuchi, A.; Ito, M.; Kaji, H.; Muramatsu, M. Visual properties and perceived restorativeness in green offices: A photographic evaluation of office environments with various degrees of greening. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1443540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-H.; Mattson, R.H. Effects of Flowering and Foliage Plants in Hospital Rooms on Patients Recovering from Abdominal Surgery. HortTechnology 2008, 18, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsaee, M.; Demers, C.M.H.; Potvin, A.; Hébert, M.; Lalonde, J.-F. Window View Access in Architecture: Spatial Visualization and Probability Evaluations Based on Human Vision Fields and Biophilia. Buildings 2021, 11, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Dzhambov, A.M. Window Access to Nature Restores: A Virtual Reality Experiment with Greenspace Views, Sounds, and Smells. Ecopsychology 2022, 14, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharam, L.A.; Mayer, K.M.; Baumann, O. Design by nature: The influence of windows on cognitive performance and affect. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 85, 101923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.; Heo, J.; Jang, H.; Kim, J. Evaluating psychophysiological responses based on the proximity and type of window view using virtual reality. Build. Environ. 2025, 270, 112575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsadek, M.; Liu, B.; Xie, J. Window view and relaxation: Viewing green space from a high-rise estate improves urban dwellers’ wellbeing. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 55, 126846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fikfak, A.; Zbašnik-Senegačnik, M.; Drobne, S. Greenery as an Element of Imageability in Window Views. Land 2022, 11, 2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbašnik-Senegačnik, M.; Koprivec, L. The Importance of the Classroom’s Window View. IGRA Ustvarjalnosti (IU)—Creat. Game (CG) 2022, 10, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsadek, M.; Deshun, Z.; Liu, B. High-rise window views: Evaluating the physiological and psychological impacts of green, blue, and built environments. Build. Environ. 2024, 262, 111798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoudinejad, S.; Hartig, T. Window View to the Sky as a Restorative Resource for Residents in Densely Populated Cities. Environ. Behav. 2020, 52, 401–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, T.; Lin, W.; Bao, Z.; Zeng, C. Natural or balanced? The physiological and psychological benefits of window views with different proportions of sky, green space, and buildings. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 104, 105293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-H.; Kuo, N.-W.; Anthony, K. Impact of window views on recovery—An example of post-cesarean section women. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2019, 31, 798–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd-Alhamid, F.; Kent, M.; Calautit, J.; Wu, Y. Evaluating the impact of viewing location on view perception using a virtual environment. Build. Environ. 2020, 180, 106932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raanaas, R.K.; Patil, G.G.; Hartig, T. Health benefits of a view of nature through the window: A quasi-experimental study of patients in a residential rehabilitation center. Clin. Rehabil. 2011, 26, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, W.H.; Schiavon, S.; Santos, L.; Kent, M.G.; Kim, H.; Keshavarzi, M. View access index: The effects of geometric variables of window views on occupants’ satisfaction. Build. Environ. 2023, 234, 110132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Munakata, J. Assessing effects of facade characteristics and visual elements on perceived oppressiveness in high-rise window views via virtual reality. Build. Environ. 2024, 266, 112043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, W.H.; Kent, M.G.; Schiavon, S.; Levitt, B.; Betti, G. A Window View Quality Assessment Framework. LEUKOS 2022, 18, 268–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, C.; Fukuda, H.; Gao, W.; Meng, X. The Physiological and Psychological Impact of Artificial Windows on Office Workers during Working Phases: Cognitive Performance and Productivity. Energy Built Environ. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blume, C.; Garbazza, C.; Spitschan, M. Effects of light on human circadian rhythms, sleep and mood. Somnologie 2019, 23, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, R.; Cappadona, R.; Tiseo, R.; Bagnaresi, I.; Fabbian, F. Therapeutic Landscape Design, Methods, Design Strategies and New Scientific Approaches. In SpringerBriefs in Applied Sciences and Technology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, S.P. Natural Light Influence on Intellectual Performance. A Case Study on University Students. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.Y.; Chai, C.-G.; Lee, H.-K.; Moon, H.; Noh, J.S. The Effects of Natural Daylight on Length of Hospital Stay. Environ. Health Insights 2018, 12, 1178630218812817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turan, I.; Chegut, A.; Fink, D.; Reinhart, C. The value of daylight in office spaces. Build. Environ. 2020, 168, 106503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, I.; Campano, M.Á.; Bellia, L.; Fragliasso, F.; Diglio, F.; Bustamante, P. Impact of Daylighting on Visual Comfort and on the Biological Clock for Teleworkers in Residential Buildings. Buildings 2023, 13, 2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydarian, A.; Carneiro, J.P.; Gerber, D.; Becerik-Gerber, B. Immersive virtual environments, understanding the impact of design features and occupant choice upon lighting for building performance. Build. Environ. 2015, 89, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Casement, M.D. Promoting adolescent sleep and circadian function: A narrative review on the importance of daylight access in schools. Chronobiol. Int. 2024, 41, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöllhorn, I.; Deuring, G.; Stefani, O.; Strumberger, M.A.; Rosburg, T.; Lemoine, P.; Pross, A.; Wingert, B.; Mager, R.; Cajochen, C. Effects of nature-adapted lighting solutions (“Virtual Sky”) on subjective and objective correlates of sleepiness, well-being, visual and cognitive performance at the workplace. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turley, K.; Rafferty, J.; Bond, R.; Mulvenna, M.; Ryan, A.; Crawford, L. Evaluating the Impact of a Daylight-Simulating Luminaire on Mood, Agitation, Rest-Activity Patterns, and Social Well-Being Parameters in a Care Home for People with Dementia: Cohort Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2024, 12, e56951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKee, C.; Hedge, A. Ergonomic lighting considerations for the home office workplace. Work 2022, 71, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amleh, D.; Halawani, A.; Hussein, M.H.; Alamlih, L. Daylighting and Patients’ Access to View Assessment in the Palestinian Hospitals’ ICUs. HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2025, 18, 221–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermann, C.; Uhrenfeldt, L.; Birkelund, R. Room for caring: Patients’ experiences of well-being, relief and hope during serious illness. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2015, 29, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubekri, M.; Lee, J.; MacNaughton, P.; Woo, M.; Schuyler, L.; Tinianov, B.; Satish, U. The Impact of Optimized Daylight and Views on the Sleep Duration and Cognitive Performance of Office Workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golmohammadi, R.; Yousefi, H.; Khotbesara, N.S.; Nasrolahi, A.; Kurd, N. Effects of Light on Attention and Reaction Time: A Systematic Review. J. Res. Health Sci. 2021, 21, e00529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, V.; Turgeon, R.; Jomphe, V.; Demers, C.M.H.; Hébert, M. Evaluation of the effects of blue-enriched white light on cognitive performance, arousal, and overall appreciation of lighting. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1390614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keschner, Y.G.; Hasdianda, M.A.; Miyawaki, S.; Baugh, C.W.; Chen, P.C.; Zhang, H.M.; Landman, A.B.; Chai, P.R. Assessing Patient Experience and Orientation in the Emergency Department with Virtual Windows. Proc. Annu. Hawaii Int. Conf. Syst. Sci. 2022, 2022, 3994–3998. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35024006/ (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Burnard, M.D.; Kutnar, A. Wood and human stress in the built indoor environment: A review. Wood Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 969–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsunetsugu, Y.; Miyazaki, Y.; Sato, H. Physiological effects in humans induced by the visual stimulation of room interiors with different wood quantities. J. Wood Sci. 2007, 53, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCunn, L.J.; Fell, D. Understanding psychosocial impressions of wood materials in simulated office interiors. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2025; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muilu-Mäkelä, R.; Ojala, A.; Harju, A.; Kostensalo, J.; Viik, J.; Wik, I.; Matilainen, H.; Virtanen, L.; Niemi, H.; Butter, K.; et al. Impact of wooden interior surfaces on indoor environment quality and perceptions: Comparisons between wooden and non-wooden office rooms. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 111, 113429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watchman, M.; Potvin, A.; Demers, C.M.H. A post-occupancy evaluation of the influence of wood on environmental comfort. BioResources 2017, 12, 8704–8724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, T.; D’Penna, K. Biophilic Design for Restorative University Learning Environments: A Critical Review of Literature and Design Recommendations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Muslimi, G.M.F. Biophilic design to promote mental health in hospital resorts. Int. Des. J. 2021, 11, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.Z. How to Build Affordable but High Quality Houses for Villagers: Appropriate Design for Aini Vernacular Houses in Xishuangbanna. Key Eng. Mater. 2012, 517, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sornubol, N.; Lekagul, A. Restorative Interior Design to Renew Attention and Reduce Stress in Small Residential Units. J. Archit. Plan. Res. Stud. (JARS) 2024, 22, 269283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watchman, M.; Potvin, A.; Demers, C.M.H. Wood and Comfort: A Comparative Case Study of Two Multifunctional Rooms. BioResources 2016, 12, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, R.W. Desain Interior Kantor Click Indonesia Global Dengan Konsep Scandinavian. Abstr. J. Kaji. Ilmu Seni Media Dan Desain 2024, 1, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Ozaki, A.; Arima, Y.; Choi, Y.; Yoo, S.-J. Numerical modeling of biophilic design incorporating large-scale waterfall into a public building: Combined simulation of heat, air, and water transfer. Build. Environ. 2024, 266, 112104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katuk, D.; Köseoğlu, E. Biophilic Architecture and Water: Examining Water as a Spatial Sensory Element. IDA Int. Des. Art J. 2022, 4, 252–270. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/91970922/Biophilic_Architecture_and_Water_Examining_Water_as_a_Spatial_Sensory_Element (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Lin, C.Y.; Shepley, M.M.; Ong, A. Blue Space: Extracting the Sensory Characteristics of Waterscapes as a Potential Tool for Anxiety Mitigation. HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2024, 17, 110–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Chu, Y.-C.; Wang, L.-W.; Tsai, S.-C. Therapeutic Potentials of Virtual Blue Spaces: A Study on the Physiological and Psychological Health Benefits of Virtual Waterscapes. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, A.; Srinivasan, M. Effect of the presence of an aquarium in the waiting area on the stress, anxiety and mood of adult dental patients: A controlled clinical trial. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, A.; Hillebrecht, A.-L.; Srinivasan, M. Effect of waiting room ambience on the stress and anxiety of patients undergoing medical treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv. Integr. Med. 2024, 11, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bogerd, N.; Dijkstra, S.C.; Seidell, J.C.; Maas, J. Greenery in the university environment: Students’ preferences and perceived restoration likelihood. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catissi, G.; de Oliveira, L.B.; da Silva Victor, E.; Savieto, R.M.; Borba, G.B.; Hingst-Zaher, E.; Lima, L.M.; Bomfim, S.B.; Leão, E.R. Nature Photographs as Complementary Care in Chemotherapy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanda, U.; Eisen, S.; Zadeh, R.S.; Owen, D. Effect of visual art on patient anxiety and agitation in a mental health facility and implications for the business case. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2011, 18, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, T.; Dillon, D.; Chew, P.K.H. The Impact of Nature Imagery and Mystery on Attention Restoration. J 2022, 5, 478–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, M.; Chi, Y.; Ram, N.; Harari, G. Physical nature associated with affective well-being, but technological nature falls short: Insights from an intensive longitudinal field study in the United States. J. Environ. Psychol. 2025, 104, 102611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweon, B.-S.; Ulrich, R.S.; Walker, V.D.; Tassinary, L.G. Anger and Stress. Environ. Behav. 2008, 40, 355–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, S.; Mihandoust, S.; Joseph, A.; Markowitz, J.; Gonzales, A.; Browning, M. Design of Pediatric Outpatient Procedure Environments: A Pilot Study to Understand the Perceptions of Patients and Their Parents. HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2024, 17, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Zhang, S. Inpatient perceptions of design characteristics related to ward environments’ restorative quality. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 41, 102410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, D.R.; Drever, S.; Soltani, M.; Sharar, S.R.; Wiechman, S.; Meyer, W.J.; Hoffman, H.G. A comparison of interactive immersive virtual reality and still nature pictures as distraction-based analgesia in burn wound care. Burns 2023, 49, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, C.; Greinacher, A.; Alt-Epping, B.; Wrzus, C. My virtual home: Needs of patients in palliative cancer care and content effects of individualized virtual reality—A mixed methods study protocol. BMC Palliat. Care 2023, 22, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, C.; Vahdati, M.; Shahrestani, M. Green walls in schools—The potential well-being benefits. Build. Environ. 2022, 224, 109560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkhomchuk, M. Domestic and International Practices in Designing Mental Health Centers. Archit. Bull. KNUCA 2024, 30–31, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Zhang, S. The restorative quality of patient ward environment: Tests of six dominant design characteristics. Build. Environ. 2020, 180, 107039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altaf, B.; Tavakoli, A.; Ruth, P.; Green, A.; Xu, J.; Jain, S.; Chiu, E.; Bencharit, L.Z.; Murnane, E.L.; Landay, J.A.; et al. Impact of windows, natural materials, and diverse representations in built environments on psychological and physiological well-being: A between-subjects experiment in immersive virtual environments. Build. Environ. 2025, 280, 113147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, I.P.; Murnane, E.L.; Bencharit, L.Z.; Altaf, B.; dos Reis Costa, J.M.; Yang, J.; Ackerson, M.; Srivastava, C.; Cooper, M.; Douglas, K.; et al. Physical workplaces and human well-being: A mixed-methods study to quantify the effects of materials, windows, and representation on biobehavioral outcomes. Build. Environ. 2022, 224, 109516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evensen, K.H.; Raanaas, R.K.; Hagerhall, C.M.; Johansson, M.; Patil, G.G. Restorative Elements at the Computer Workstation. Environ. Behav. 2015, 47, 288–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Bratman, G.N.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Spengler, J.D.; Olvera-Alvarez, H.A. Stress recovery from virtual exposure to a brown (desert) environment versus a green environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 81, 101775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, R.S.; Shepley, M.M.; Williams, G.; Chung, S.S.E. The Impact of Windows and Daylight on Acute-Care Nurses’ Physiological, Psychological, and Behavioral Health. HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2014, 7, 35–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, J.A.; Ikaga, T.; Sanchez, S.V. Quantitative improvement in workplace performance through biophilic design: A pilot experiment case study. Energy Build. 2018, 177, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yang, H.; Zhong, B. Home Greenery: Alleviating Anxiety during Lockdowns with Varied Landscape Preferences. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanzadeh, M. Enhancing User Experience in Interior Architecture Through Biophilic Design: A Case Study of Urban Residential Spaces. New Des. Ideas 2024, 8, 137–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirkol, A.K.; Önaç, A.K. Integratıng bıophılıc desıgn elements ınto offıce desıgns. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, M.; Pazhouhanfar, M.; Stoltz, J. Evaluating Patients’ Preferences for Dental Clinic Waiting Area Design and the Impact on Perceived Stress. Buildings 2024, 14, 3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakr, E.; Kim, J. Evaluating Industry Perception of Biophilic Design in Enhancing Construction Job site Trailers’ Physical Work Environment. In EPiC Series in Built Environment, Proceedings of the 60th Annual Associated Schools of Construction International Conference (ASC 2024), Auburn, AL, USA, 3–5 April 2024; EasyChair: Stockport, UK, 2024; Volume 5, pp. 358–366. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, D.T.C.; Shanahan, D.F.; Hudson, H.L.; Plummer, K.E.; Siriwardena, G.M.; Fuller, R.A.; Anderson, K.; Hancock, S.; Gaston, K.J. Doses of Neighborhood Nature: The Benefits for Mental Health of Living with Nature. AIBS Bull. 2017, 67, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Larsen, L.; Deal, B.; Sullivan, W.C. A dose–response curve describing the relationship between tree cover density and landscape preference. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 139, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, I.; DeVille, N.V.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Buehler, R.M.; Hart, J.E.; Hipp, J.A.; Mitchell, R.; Rakow, D.A.; Schiff, J.E.; White, M.P.; et al. Measuring Nature Contact: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treisman, A.M.; Gelade, G. A feature-integration theory of attention. Cogn. Psychol. 1980, 12, 97–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, P.M.; Thompson, R.F. Habituation: A dual-process theory. Psychol. Rev. 1970, 77, 419–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsukkar, M.; Ibrahim, A.; Eltaweel, A. Multi-objective optimization of daylighting systems for energy efficiency and thermal–visual comfort in buildings: A review. Build. Environ. 2026, 288, 113921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.M. Presence, Explicated. Commun. Theory 2004, 14, 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vianen, A.E.M. Person–Environment Fit: A Review of Its Basic Tenets. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 75–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sedghikhanshir, A.; Montelli, R. Biophilic Design Interventions and Properties: A Scoping Review and Decision-Support Framework for Restorative and Human-Centered Buildings. Buildings 2026, 16, 515. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030515

Sedghikhanshir A, Montelli R. Biophilic Design Interventions and Properties: A Scoping Review and Decision-Support Framework for Restorative and Human-Centered Buildings. Buildings. 2026; 16(3):515. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030515

Chicago/Turabian StyleSedghikhanshir, Alireza, and Raffaella Montelli. 2026. "Biophilic Design Interventions and Properties: A Scoping Review and Decision-Support Framework for Restorative and Human-Centered Buildings" Buildings 16, no. 3: 515. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030515

APA StyleSedghikhanshir, A., & Montelli, R. (2026). Biophilic Design Interventions and Properties: A Scoping Review and Decision-Support Framework for Restorative and Human-Centered Buildings. Buildings, 16(3), 515. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030515