Study of the Resistivity of Concrete Modified with Recycled PET and Cane Bagasse Fiber to Facilitate the Cathodic Protection of Reinforcing Steel

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aggregates Preparation

2.1.1. Grinding of rPET

2.1.2. Selection and Delignification of Cane Bagasse Fiber (CBF)

2.2. Mixture Design

2.3. Mechanical Characterization

Compressive Strength

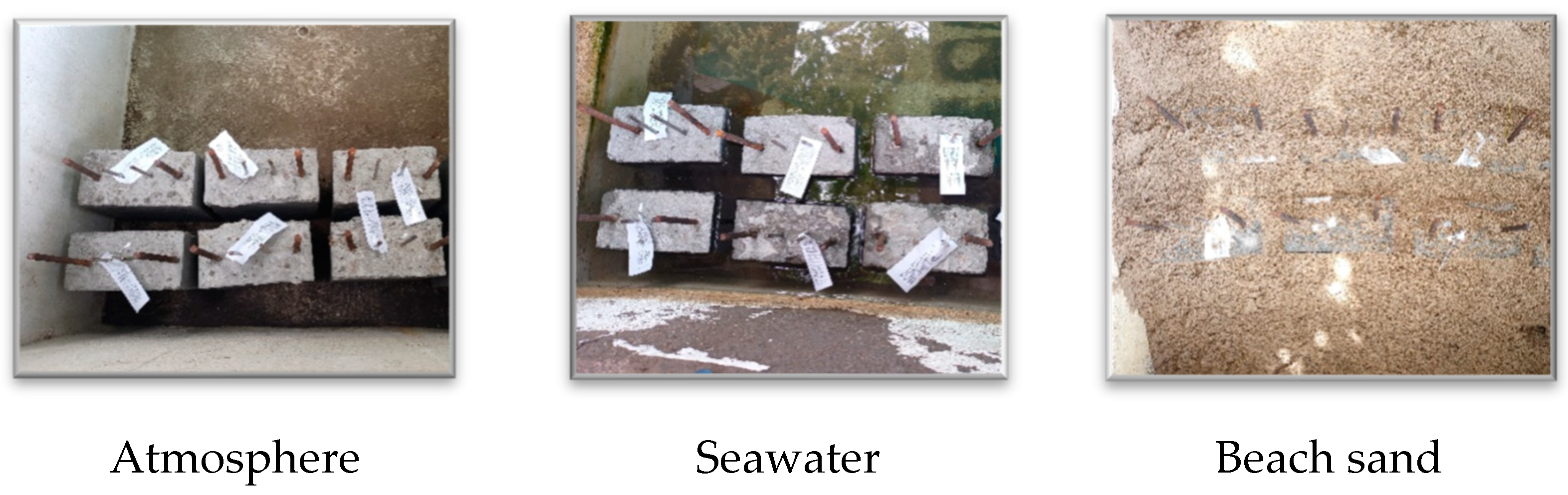

2.4. Exposure to Aggressive Environments

2.5. Electrical Characterization

2.6. Cathode Polarization Curves

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

3.1. Preparation of Aggregates

3.1.1. Grinding of rPET

3.1.2. CBF Delignification

3.2. Mechanical Characterization

Compressive Strength

3.3. Resistivity Results

3.4. Cathodic Polarization Curve Results

3.5. Efficiency of Cathodic Protection

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Compendio Tecnología del Hormigón: Instituto Chileno del Cemento y del Hormigón (ICH). Available online: https://ich.cl/publicaciones/compendio-tecnologia-del-hormigon/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Francis, A.J. The Cement Industry: A History; David&Charles: Madison, WI, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Huntzinger, D.N.; Eatmon, T.D. A life-cycle assessment of Portland cement manufacturing: Comparing the traditional process with alternative technologies. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 668–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igliński, B.; Buczkowski, R. Development of cement industry in Poland—History, current state, ecological aspects. A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 702–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Cheung, M.M.; Chan, B.Y. Modelado de la interacción entre la corrosión inducida por grietas en la cubierta del hormigón y la tasa de corrosión del acero. Corros. Sci. 2013, 69, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Cheung, M.M. Expansión de óxido no uniforme para corrosión por picaduras inducida por cloruro en estructuras de hormigón armado. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 51, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranc, S.C.; Sagüés, A.A. Detailed Modeling of Corrosion Macrocells on Steel Reinforcing in Concrete. Corros. Sci. 2001, 43, 1355–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozinguez, E.; Barthélémy, F.; Bouteiller, V.; Desbois, T. Contribución del ánodo de sacrificio en la reparación de parches de hormigón armado: Resultados de simulaciones numéricas. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 178, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolini, L.; Gastaldi, M.; Pedeferri, M.; Redaelli, E. Prevention of steel corrosion in concrete exposed to seawater with submerged sacrificial anodes. Corros. Sci. 2002, 44, 1497–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArthur, H.; D’Arcy, S.; Barker, J. Cathodic protection by impressed DC currents for construction, maintenance and refurbishment in reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 1993, 7, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouevidjin, A.B.; Adessina, A.; Barthélémy, J.-F.; Carpio-Perez, J.; Fraj, A.B.; Pavoine, A. Efficiency of the Impressed Current Cathodic Protection (ICCP) in reinforced concretes: Experimental and numerical investigation. Electrochim. Acta 2024, 480, 143923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broomfield, J.P. The Principles and Practice of Galvanic Cathodic Protection for Reinforced Concrete Structures; Technical note 6; Corrosion Prevention Association: Bordon, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- HA (Highways Agency). Design Manual for Roads and Bridges, Cathodic Protection for Use in Reinforced Concrete Highway Structures; Highways Agency: London, UK, 2002; Volume 3.

- Jiang, H.; Jin, Z.; Li, S.; Zhang, X. Composition-structure-corrosion resistance of steel passive film in concrete under cathodic protection. Corros. Sci. 2026, 260, 113551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Z.; Ansari, W.S.; Akbar, M.; Azam, A.; Lin, Z.; Yosri, A.M.; Shaaban, W.M. Microstructural and mechanical assessment of sulfate-resisting cement concrete over portland cement incorporating sea water and sea sand. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kean, R.L.; Davies, K.G. Cathodic Protection, Guide Prepared British Department Trade and Industry; National Physical Laboratory: Teddington, UK, 1981; Volume 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Kiamahalleh, M.V.; Gholampour, A.; Tang, Y.; Ngo, T.D. Incorporation of reduced graphene oxide in waste-based concrete including lead smelter slag and recycled coarse aggregate. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 88, 109221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, H.M.; Shi, J.; Al Jawahery, M.S.; Majdi, A.; Yousif, S.T.; Kaplan, G. Application of natural fibres in cement concrete: A critical review. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 35, 105833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshaid, H.; Mishra, R.K.; Raza, A.; Hussain, U.; Rahman, M.L.; Nazari, S.; Chandan, V.; Muller, M.; Choteborsky, R. Natural Cellulosic Fiber Reinforced Concrete: Influence of Fiber Type and Loading Percentage on Mechanical and Water Absorption Performance. Materials 2022, 15, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooqi, M.U.; Ali, M. Effect of Fibre Content on Compressive Strength of Wheat Straw Reinforced Concrete for Pavement Applications. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 422, 012014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, J.A.; Hawileh, R.A.; Bahurudeen, A.; Jyothsna, G.; Sofi, A.; Shanmugam, V.; Thomas, B. A comprehensive review on the use of natural fibers in cement/geopolymer concrete: A step towards sustainability. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anas, M.; Khan, M.; Bilal, H.; Jadoon, S.; Khan, M.N. Fiber Reinforced Concrete: A Review. Eng. Proc. 2022, 22, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C33/C33M-18; Standard Specification for Concrete Aggregates. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- De la Cruz Cruz, C.A. Determinación de la Eficiencia de Protección Del Sistema Concreto-Acero de Refuerzo Modificado Mediante Bagazo de Caña Y la Aplicación de Tratamientos Base Cerio. (Tesis de Maestría) Instituto Politécnico Nacional. 2016. Available online: https://www.repositoriodigital.ipn.mx/handle/123456789/137/browse?type=author&order=ASC&rpp=20&starts_with=de+la+cruz+cruz (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- ASTM C39/C39M-18; Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018. Available online: http://www.astm.org (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- ASTM G57-95a; Standard Test Method for Field Measurement of Soil Resistivity Using the Wenner Four-Electrode Method. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2001.

- SP0290-2007; Impressed Current Cathodic Protection of Reinforcing Steel in Atmospherically Exposed Concrete Structures. NACE: Houston, TX, USA, 2007.

- Sanchez-Torres, R.; Bustamante, E.O.; López, T.P.; Espindola-Flores, A.C. Efficiency Determination of Water Lily (Eichhornia crassipes) Fiber Delignification by Electrohydrolysis Using Different Electrolytes. Recycling 2025, 10, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N-CMT-2-02-005/04; Características de Los Materiales, Materiales Para Estructuras, Materiales Para Concreto Hidráulico, Calidad Del Concreto Hi-Dráulico. Secretaría de Comunicaciones y Transporte: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2004.

- N-CMT-2-02-001/02; Características de Los Materiales, Materiales Para Estructuras, Materiales Para Concreto Hidráulico, Calidad Del Cemento Portland. Secretaría de Comunicaciones y Transporte: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2004.

- Oviello, C.G.; Lassandro, P.; Sabbà, M.F.; Foti, D. Mechanical and Thermal Effects of Using Fine Recycled PET Aggregates in Common Screeds. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polder, R.; Andrade, C.; Elsener, B.; Vennesland, Ø.; Gulikers, J.; Weidert, R.; Raupach, M. Test methods for on site measurement of resistivity of concrete. Mat. Struct. 2000, 33, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Beaudoin, J.J. Electrically Conductive Concrete and its Application in Deicing. In SP-154: Advances in Concrete Technology, Proceedings of the Second CANMET/ACI International Symposium, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 11–14 June 1995; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olam, M. Pet: Production, Properties and Applications. In Advances in Materials Science Research; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Espindola-Flores, A.C.; Luna-Jimenez, M.A.; Onofre-Bustamante, E.; Morales-Cepeda, A.B. Study of the Mechanical and Electrochemical Performance of Structural Concrete Incorporating Recycled Polyethylene Terephthalate as a Partial Fine Aggregate Replacement. Recycling 2024, 9, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, E.O.; Espindola-Flores, A.C.; Fuente, A.K.C.D.L. Study of Integration, Distribution and Degradation of Sugarcane Bagasse Fiber as Partial Replacement for Fine Aggregate in Concrete Samples. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2023, 57, 1121–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearsley, E.; Wainwright, P.J. Porosity and permeability of foamed concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2001, 31, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, G.C.; Kurtis, K.E. Effect of mechanical processing on sugar cane bagasse ash pozzolanicity. Cem. Concr. Res. 2017, 97, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, J.; Boluk, Y.; Bindiganavile, V. Cellulose nanofibres mitigate chloride ion ingress in cement-based systems. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 114, 103780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Xing, M.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Guan, X. Micro-pore structure characteristics and macro-mechanical properties of PP fibre reinforced coal gangue ceramsite concrete. J. Eng. 2020, 2020, 1192–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerna, M.; Foti, D.; Petrella, A.; Sabbà, M.F.; Mansour, S. Effect of the Chemical and Mechanical Recycling of PET on the Thermal and Mechanical Response of Mortars and Premixed Screeds. Materials 2023, 16, 3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coviello, C.G.; Mansour, S.; Rizzo, F.; Foti, D. An experimental study on the mechanical and thermal properties of graphene-reinforced screeds. In Proceedings of the 3rd fib Italy YMG Symposium on Concrete and Concrete Structures, Torino, Italy, 9–10 November 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Sample | Mixture Component (Kg/m3) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cement | Water | Coarse | Fine | rPET | CBF | |

| Reference | 395 | 180 | 952.8 | 861.3 | 0 | 0 |

| rPET2.5 | 395 | 180 | 952.8 | 839.76 | 21.53 | 0 |

| rPET5 | 395 | 180 | 952.8 | 818.23 | 43.06 | 0 |

| rPET10 | 395 | 180 | 952.8 | 775.17 | 86.13 | 0 |

| rPET2.5-CBF | 395 | 180 | 952.8 | 831.16 | 21.53 | 8.61 |

| rPET5-CBF | 395 | 180 | 952.8 | 809.63 | 43.06 | 8.61 |

| rPET10-CBF | 395 | 180 | 952.8 | 766.56 | 86.13 | 8.61 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Espindola-Flores, A.C.; Somoza-Méndez, M.A.; Pérez Sánchez, F.J.; Onofre-Bustamante, E. Study of the Resistivity of Concrete Modified with Recycled PET and Cane Bagasse Fiber to Facilitate the Cathodic Protection of Reinforcing Steel. Buildings 2026, 16, 512. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030512

Espindola-Flores AC, Somoza-Méndez MA, Pérez Sánchez FJ, Onofre-Bustamante E. Study of the Resistivity of Concrete Modified with Recycled PET and Cane Bagasse Fiber to Facilitate the Cathodic Protection of Reinforcing Steel. Buildings. 2026; 16(3):512. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030512

Chicago/Turabian StyleEspindola-Flores, Ana C., Manuel A. Somoza-Méndez, Francisco J. Pérez Sánchez, and Edgar Onofre-Bustamante. 2026. "Study of the Resistivity of Concrete Modified with Recycled PET and Cane Bagasse Fiber to Facilitate the Cathodic Protection of Reinforcing Steel" Buildings 16, no. 3: 512. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030512

APA StyleEspindola-Flores, A. C., Somoza-Méndez, M. A., Pérez Sánchez, F. J., & Onofre-Bustamante, E. (2026). Study of the Resistivity of Concrete Modified with Recycled PET and Cane Bagasse Fiber to Facilitate the Cathodic Protection of Reinforcing Steel. Buildings, 16(3), 512. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16030512