An Excitation Modification Method for Predicting Subway-Induced Vibrations of Unopened Lines

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Field measurement arrangements and vibration characteristic analysis are introduced, followed by the development and validation of a 2D finite element model.

- Mathematical derivation of the frequency-band excitation modification formulas is established, incorporating tunnel burial depth, tunnel diameter, soil properties, and train speed. The method is subsequently verified through theoretical analysis and an engineering case study.

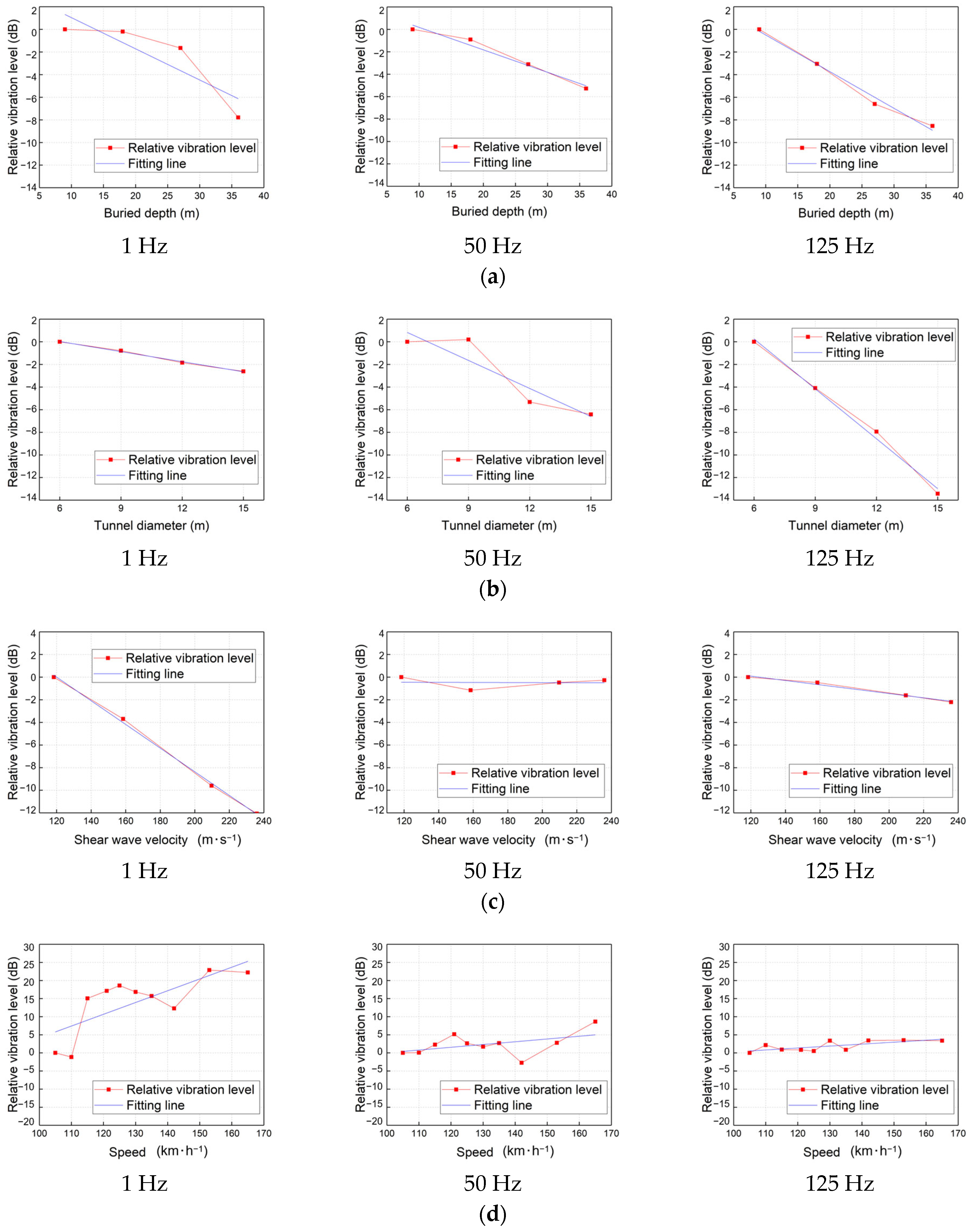

- Parametric sensitivity analyses are conducted to investigate the influence of the four key parameters on ground vibration responses using the proposed method.

2. Field Measurements

2.1. Engineering Background

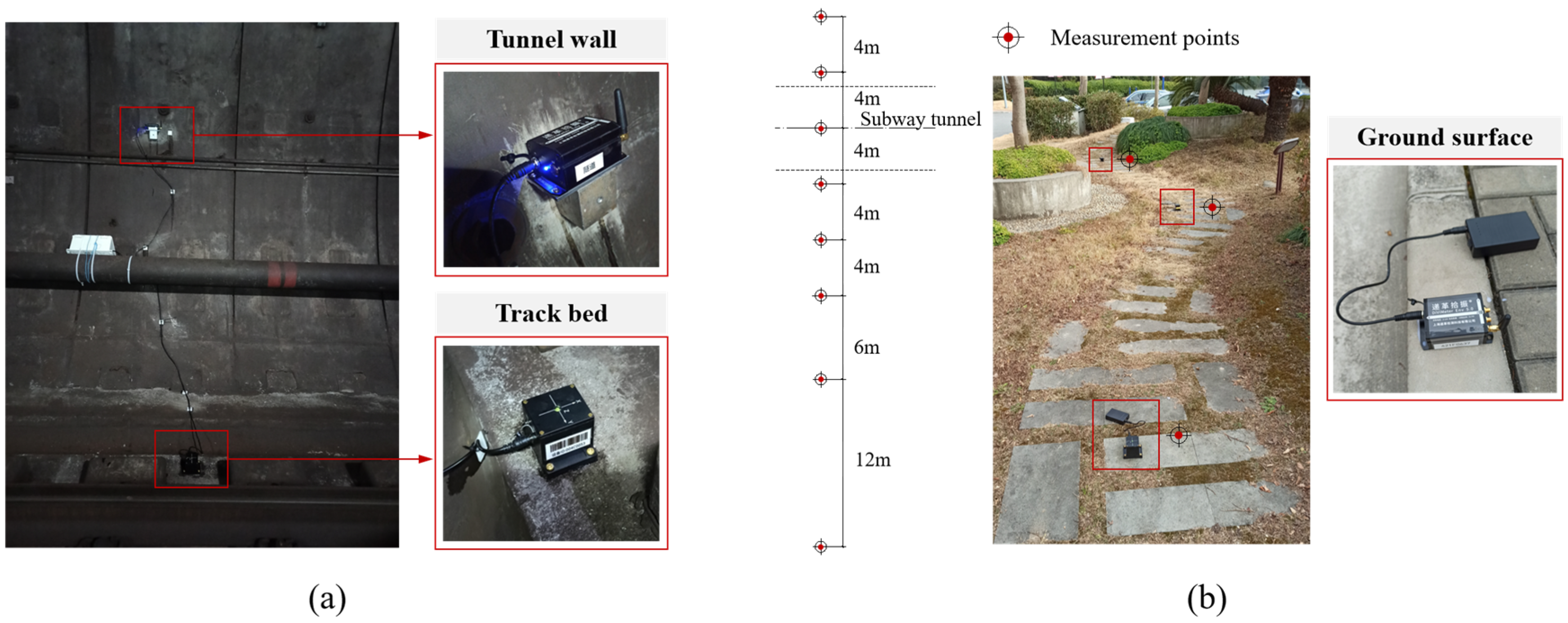

2.2. Measurement Arrangement

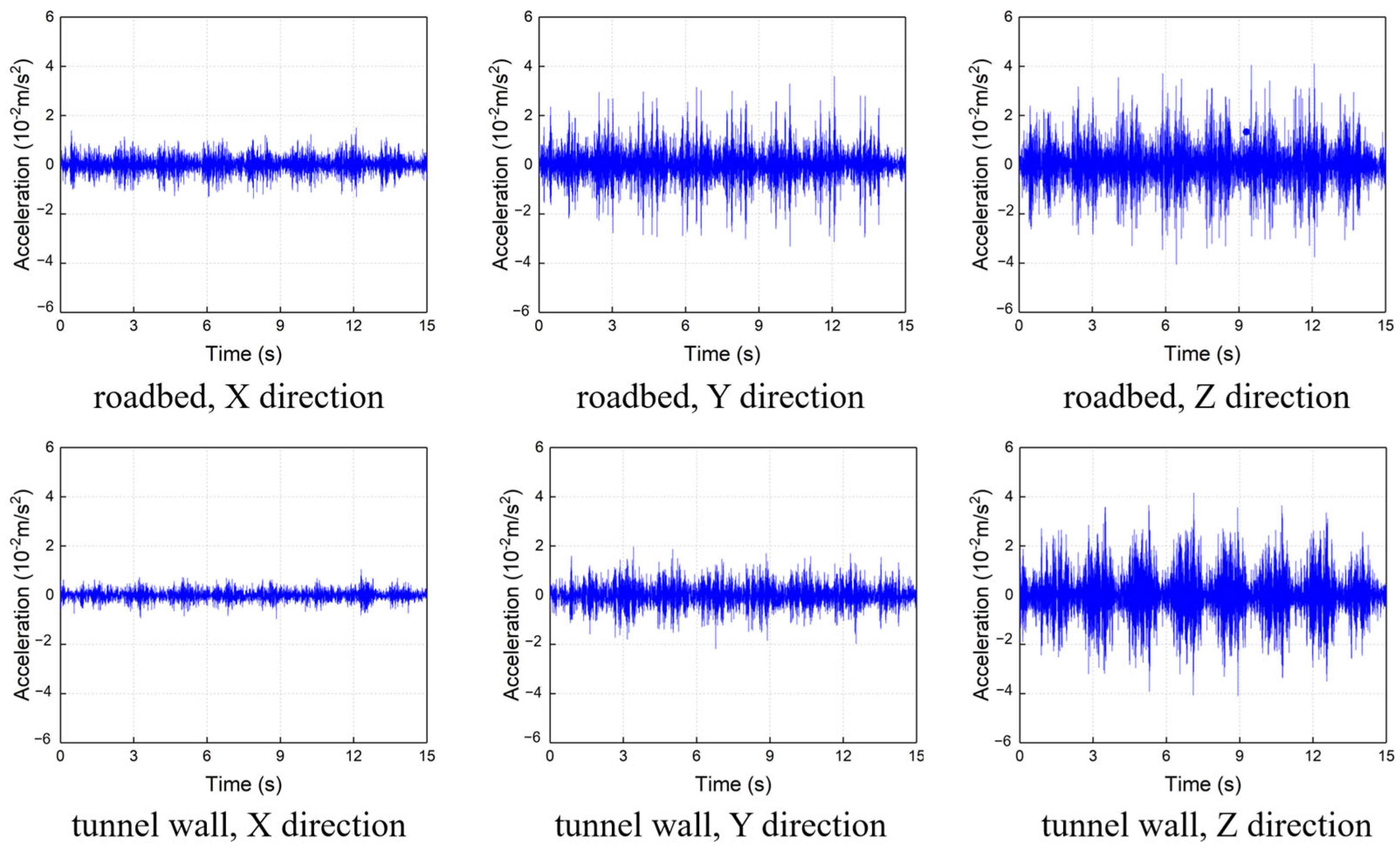

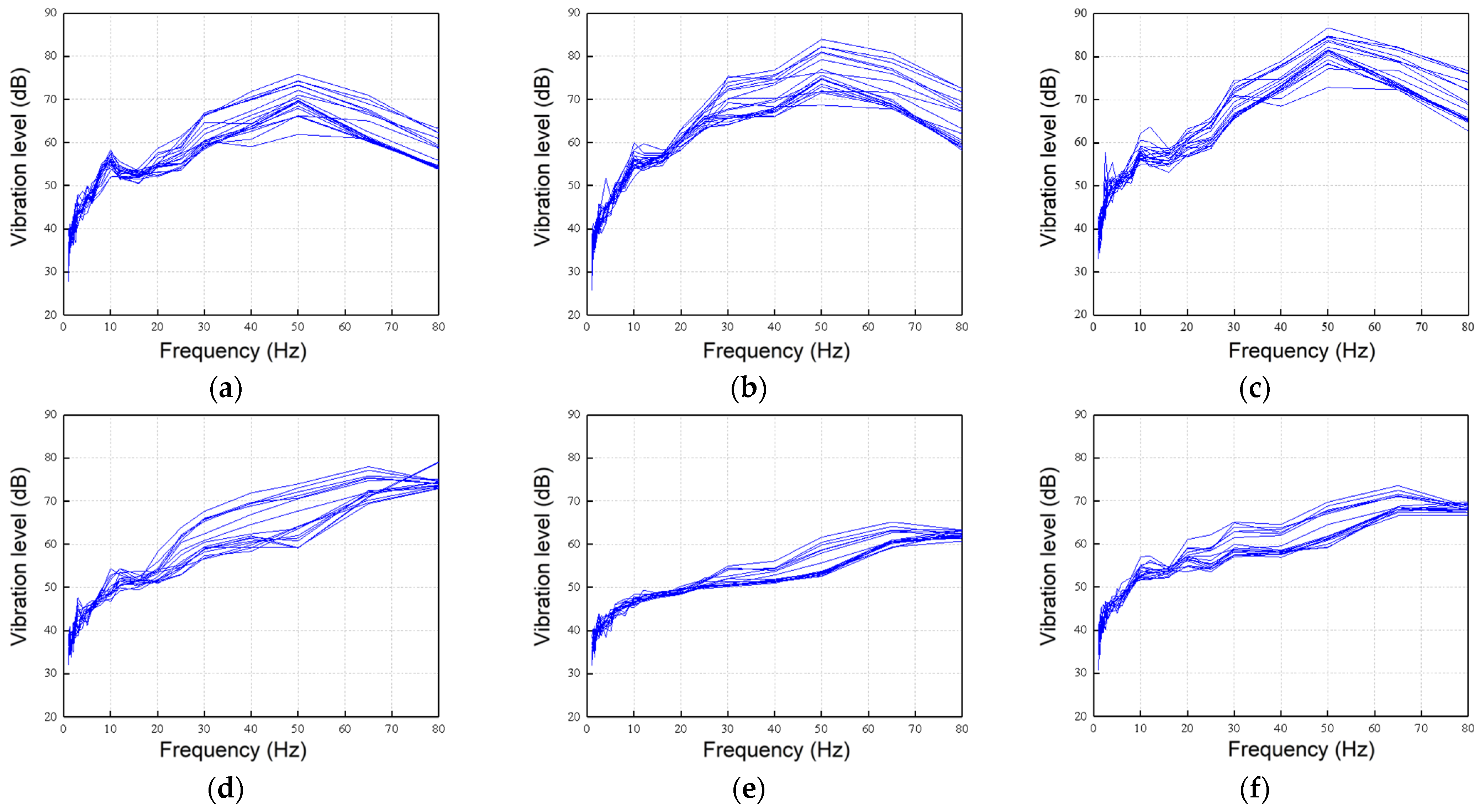

2.3. Characteristics of Vibrations in the Tunnel

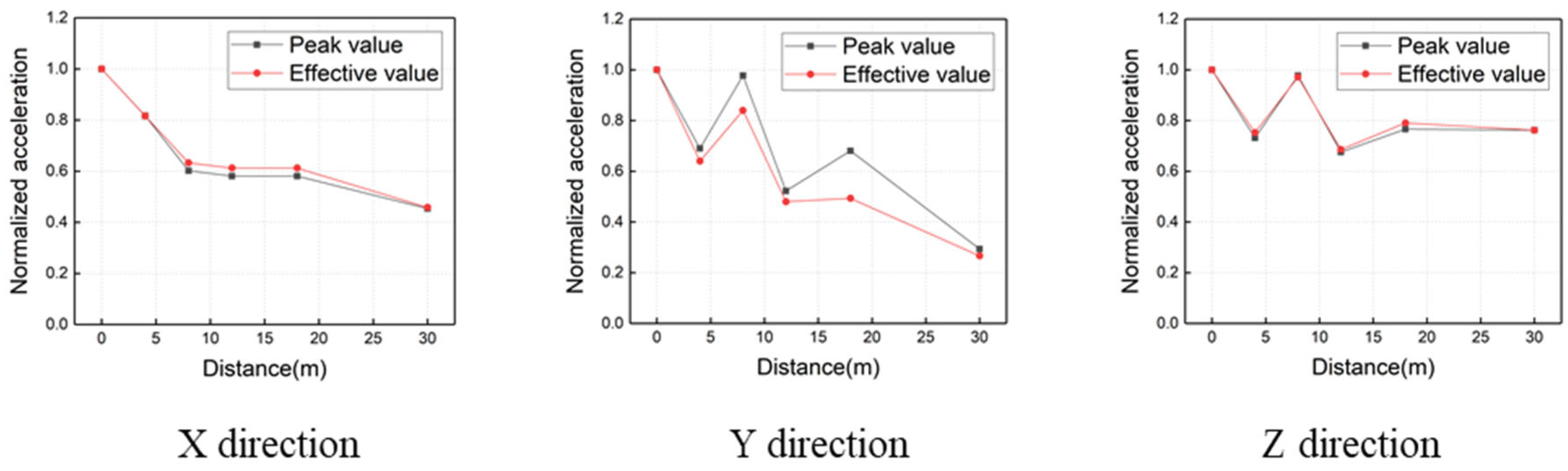

2.4. Characteristics of Ground Vibrations

3. Numerical Simulation

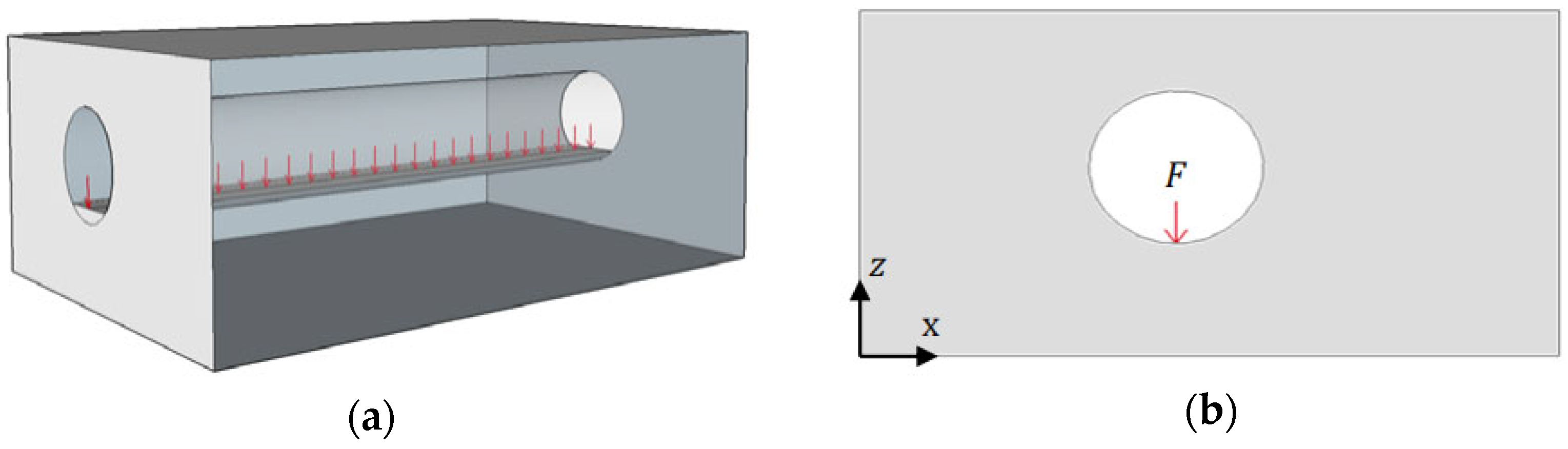

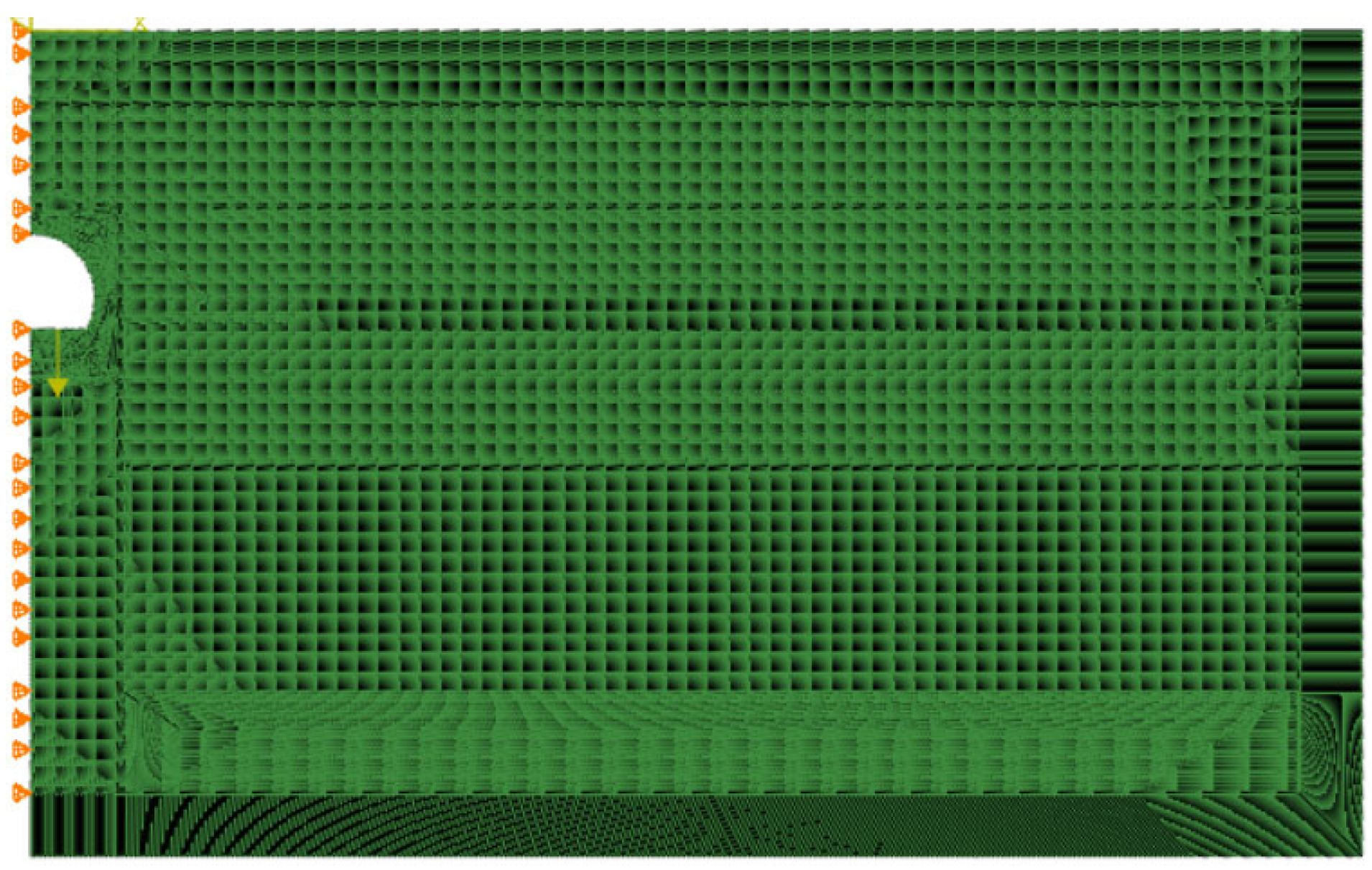

3.1. Finite Element Model

3.1.1. Justification for the 2D FEM

3.1.2. Model Parameters

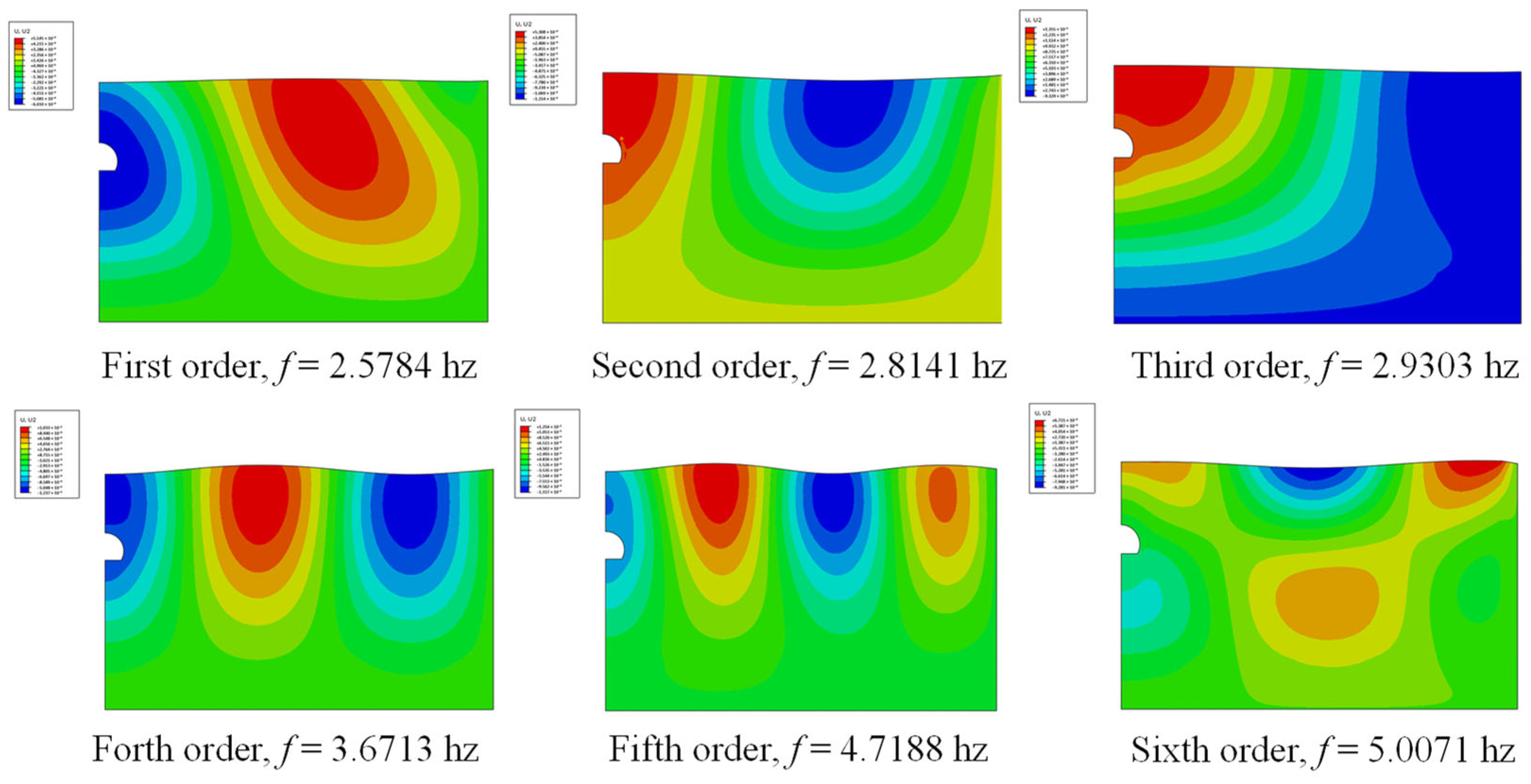

3.2. Modal Analysis

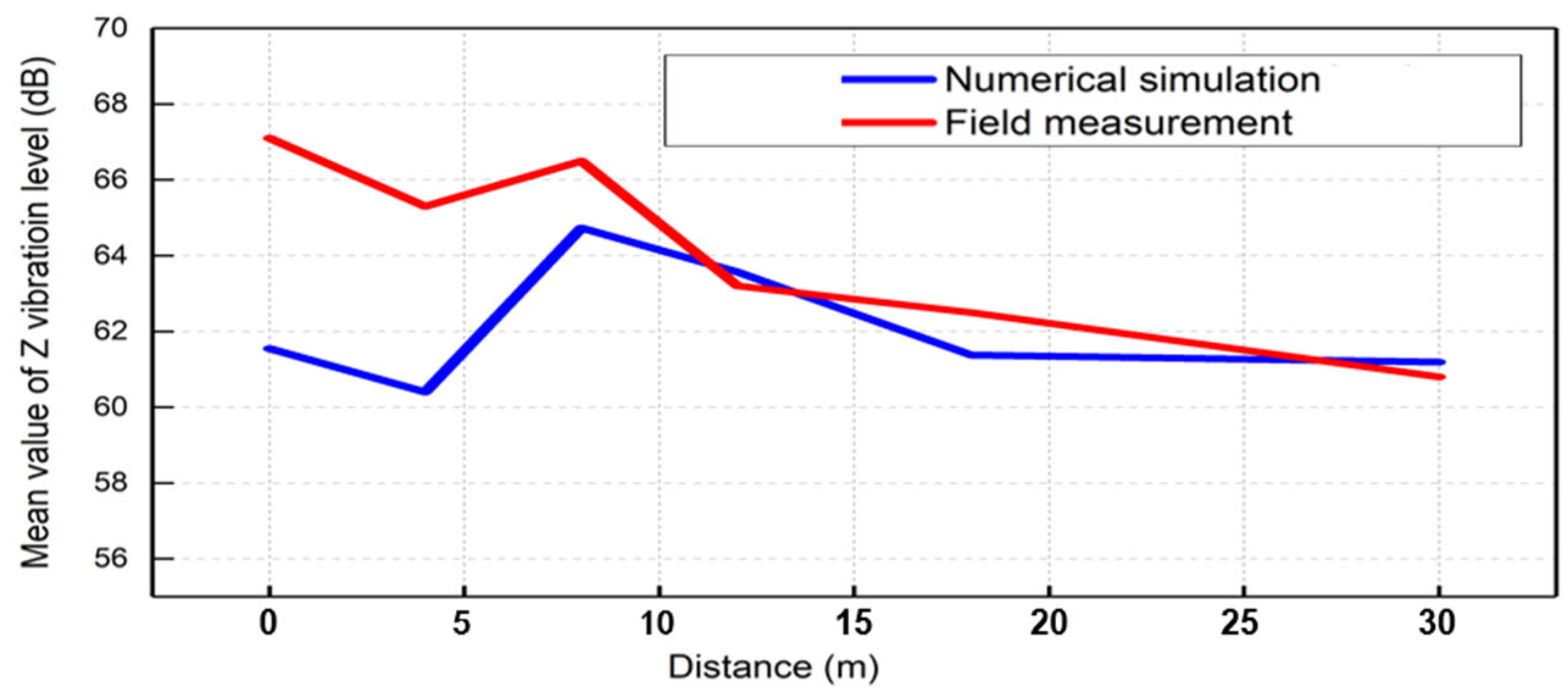

3.3. Validation of FEM Simulation

4. Excitation Modification Method

4.1. Excitation Modification Formula

4.2. Verification Through Theoretical Analysis

4.3. Verification Through Engineering Examples

5. Parametric Sensitivity Analysis and Discussion

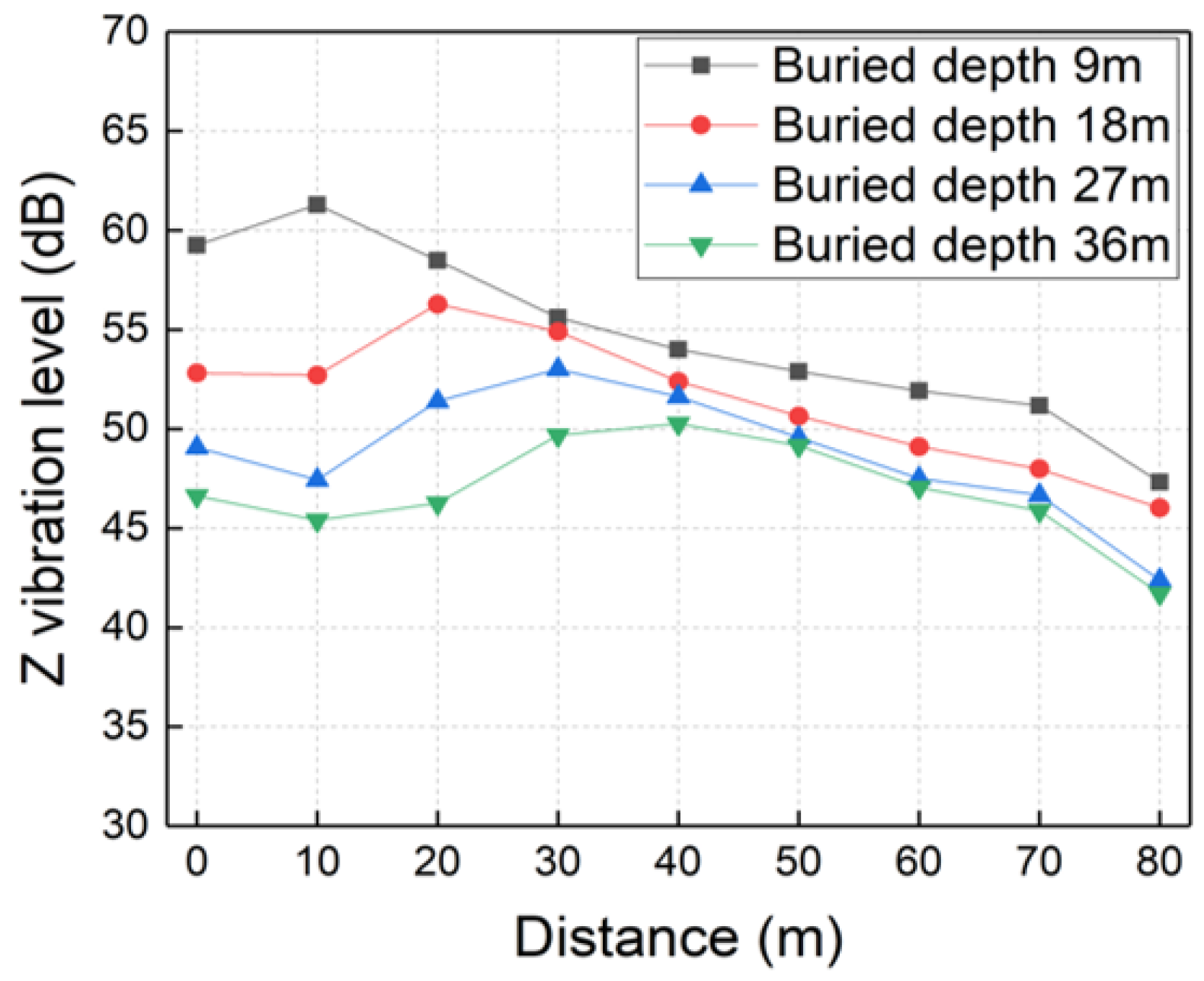

5.1. Tunnel Burial Depth

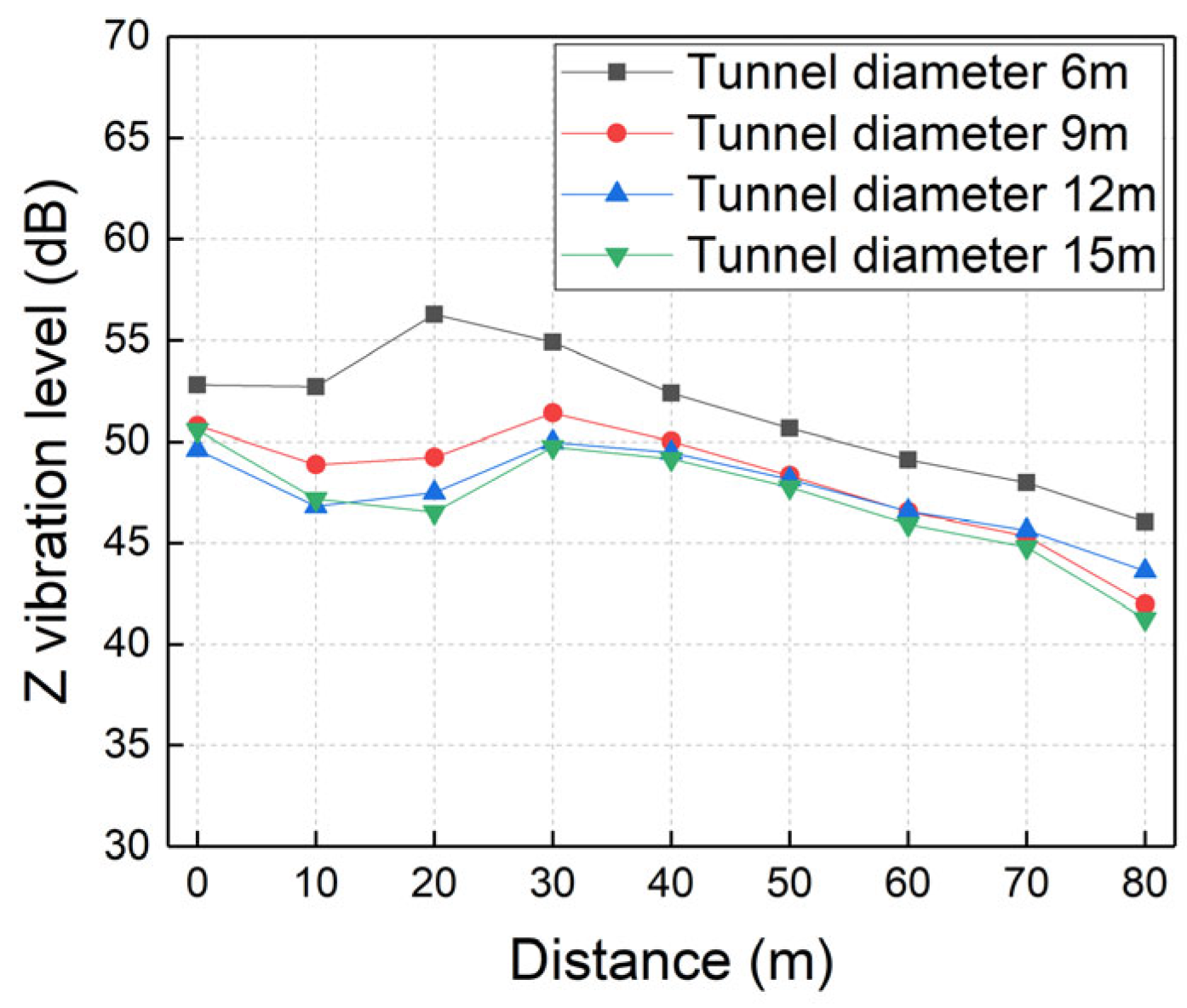

5.2. Tunnel Diameter

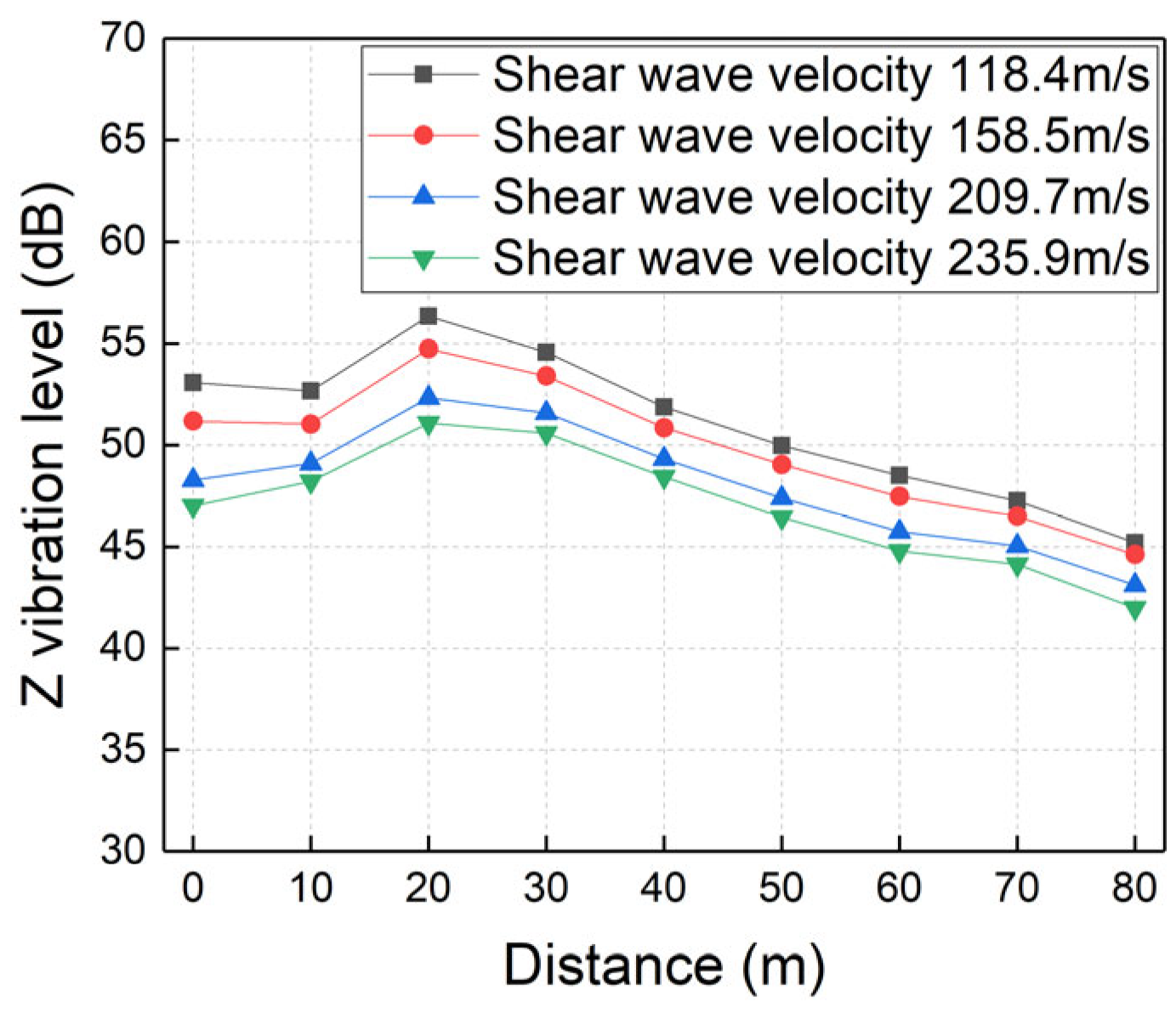

5.3. Soil Properties

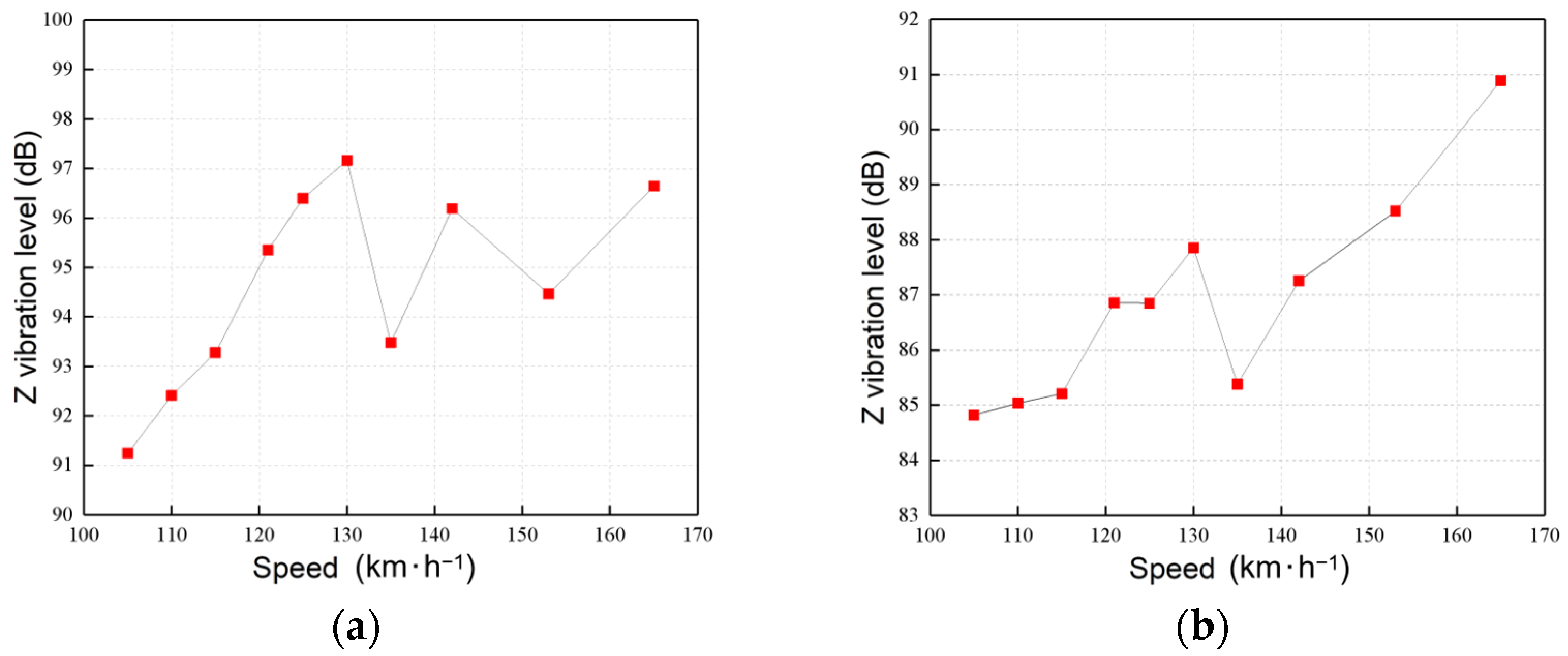

5.4. Train Speed

6. Discussion

6.1. Assumptions of Linearity and Superposition

6.2. Physical Modeling Simplifications

6.3. Scope of Applicability and Generalization

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- Field measurements indicate that vertical vibration dominates the tunnel response, and the vibration at the tunnel wall is more stable than at the track bed. The established 2D FEM was validated against field data, showing high accuracy with a prediction error of less than 3% in the near-field region, proving its suitability for parametric analysis.

- (2)

- The proposed excitation modification method improves prediction accuracy. Application to the engineering case study demonstrates that, compared to the traditional analogy method, the prediction error is reduced from 10.1% to 5.2%. This confirms that incorporating correction terms for key parameters effectively aligns the reference line data with the target line conditions, particularly for tunnels situated in soft soil environments similar to the verified case.

- (3)

- Ground vibration levels generally decrease with increasing tunnel burial depth, tunnel diameter, and soil shear wave velocity, while increasing linearly with train speed. Distinct vibration amplification zones are observed at specific distances correlated with burial depth and diameter. Furthermore, increasing the tunnel diameter yields the most significant mitigation benefits for smaller tunnels (6 m–9 m), and improving soil stiffness is particularly dominant in reducing near-field vibrations.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Duan, X.; Han, H. Design and Evaluation of Historically and Culturally Integrated Metro Spaces: A Case Study of Xi’an Metro Stations. Buildings 2025, 15, 4278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; He, B.; Li, G.; Wang, J.; Ou, Y.; Luo, Q.; Chen, H.; Zhong, K.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, Y. A Comparative Analysis of Prefabricated and Traditional Construction of a Rail Transit Equipment Room Piping System Under a Mountainous Area: A Case Study of Chongqing Rail Transit. Buildings 2025, 15, 4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, G.; Li, H.; Liu, G.; Han, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, C. Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete Segments for Shield Tunnels: A Comprehensive Review of Mechanical Performance, Design Methods and Future Directions. Buildings 2025, 15, 4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, P.; Yang, Y.; Xu, D. An improved EMD method for modal identification and a combined static-dynamic method for damage detection. J. Sound Vib. 2018, 420, 242–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, M.; Zhu, J.; Chen, D. Assessing Train-Induced Building Vibrations in a Subway Transfer Station and Potential Control Strategies. Buildings 2025, 15, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, M.; Lu, F.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, R.; Chen, Y.; Huang, W.; Zhao, Y. Dynamic Characteristics and Parameter Optimization of Floor Vibration Isolation Systems for Metro-Induced Vibrations in Over-Track Buildings. Buildings 2025, 15, 3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Bai, W.; Dai, J.; Sun, G. Measurement and analysis of vibration responses due to subway transit in residential areas. Structures 2024, 69, 107305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, D.P.; Costa, P.A.; Kouroussis, G.; Galvin, P.; Woodward, P.K.; Laghrouche, O. Large scale international testing of railway ground vibrations across Europe. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2015, 71, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zheng, B.; Chen, Y.; Zou, C. A hybrid methodology for estimating train-induced rigid foundation building vibrations. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 460, 139852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, Z.; Lu, D.; Ma, K.; Li, J.; Guan, Q.; Zhang, Z. Investigations on vertical and horizontal behavior of a three-dimensional isolation system for seismic isolation and subway-induced vibration control. Measurement 2025, 256, 118457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, R.A.; Greer, R.J.; Breslin, M.; Williams, P.R. The Calculation and Assessment of Ground-Borne Noise and Perceptible Vibration from Trains in Tunnels. J. Sound Vib. 1996, 193, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.Y.; Gu, X.Q.; Huang, M.S.; Ma, X.F.; Li, N. Experimental, numerical and analytical studies on the attenuation of maglev train-induced vibrations with depth in layered soils. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2021, 143, 106628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, P.; Di, H. Subway-Caused Vibration Propagation Behavior Inside Buildings Above Metro Tunnels. Transp. Res. Rec. 2025, 2679, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, W.; Shen, L.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Chen, J. A hybrid methodology for the prediction of subway train-induced building vibrations based on the ground surface response. Transp. Geotech. 2024, 48, 101330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Song, K.-I.; Kang, K.-N.; Lee, D. Numerical analysis of vibration standard conditions of adjacent buildings caused by subway train. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2025, 29, 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvín, P.; Domínguez, J. Experimental and numerical analyses of vibrations induced by high-speed trains on the Córdoba–Málaga line. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2009, 29, 641–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, W.M.; Wang, K.Y.; Cai, C.B. Fundamentals of vehicle-track coupled dynamics. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2009, 47, 1349–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kacimi, A.; Woodward, P.K.; Laghrouche, O.; Medero, G. Time domain 3D finite element modelling of train-induced vibration at high speed. Comput. Struct. 2013, 118, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.Q.; Yang, Q.; Ren, X.W.; Xiao, S.Q. Dynamic response of soft soils in high-speed rail foundation: In situ measurements and time domain finite element method model. Can. Geotech. J. 2019, 56, 1832–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, D.; Giannopoulos, A.; Forde, M.C. Numerical modelling of ground borne vibrations from high speed rail lines on embankments. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2013, 46, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slimane, H.; Berdoudi, S.; Hadji, R. Blast-induced vibration assessment in the Rouina open-pit mine: Impacts and measurements for the Ouled Mellouk Dam. Min. Miner. Depos. 2024, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, K.A.; Papadopoulos, M.; Lombaert, G.; Degrande, G. The coupling loss of a building subject to railway induced vibrations: Numerical modelling and experimental measurements. J. Sound Vib. 2019, 442, 459–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouroussis, G.; Verlinden, O.; Conti, C. Free field vibrations caused by high-speed lines: Measurement and time domain simulation. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2011, 31, 692–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.Y.; Thompson, D.J.; Lurcock, D.E.J.; Toward, M.G.R.; Ntotsios, E. A 2.5D finite element and boundary element model for the ground vibration from trains in tunnels and validation using measurement data. J. Sound Vib. 2018, 422, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.C.; Jiang, H.G.; Chang, C.; Hu, J.; Chen, Y.M. Track and ground vibrations generated by high-speed train running on ballastless railway with excitation of vertical track irregularities. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2015, 76, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.B.; Hung, H.H. A 2.5D finite/infinite element approach for modelling visco-elastic bodies subjected to moving loads. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 2001, 51, 1317–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, H.H.; Yang, Y.B. Analysis of ground vibrations due to underground trains by 2.5D finite/infinite element approach. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2010, 9, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.C.; Hung, H.H.; Yang, J.P.; Yang, Y.B. Seismic analysis of underground tunnels by the 2.5D finite/infinite element approach. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2016, 85, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Xu, C.; Chen, J.; Song, J. Investigation of ground vibrations induced by trains moving on saturated transversely isotropic ground. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2018, 104, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.Y.; Xiao, Z.C.; Liu, T.; Lou, P.; Song, X.M. Comparison of 2D and 3D prediction models for environmental vibration induced by underground railway with two types of tracks. Comput. Geotech. 2015, 68, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanayei, M.; Zhao, N.Y.; Maurya, P.; Moore, J.A.; Zapfe, J.A.; Hines, E.M. Prediction and Mitigation of Building Floor Vibrations Using a Blocking Floor. J. Struct. Eng. 2012, 138, 1181–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.A.; Powrie, W.; Priest, J.A. Dynamic Stress Analysis of a Ballasted Railway Track Bed during Train Passage. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2009, 135, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesami, S.; Ahmadi, S.; Ghalesari, A.T. Numerical Modeling of Train-induced Vibration of Nearby Multi- story Building: A Case Study. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2016, 20, 1701–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.B.; Liang, X.J.; Hung, H.H.; Wu, Y.T. Comparative study of 2D and 2.5D responses of long underground tunnels to moving train loads. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2017, 97, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, J.; Fraile, A.; Alarcon, E.; Hermanns, L. Dynamic response of underpasses for high-speed train lines. J. Sound Vib. 2012, 331, 5125–5140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real, T.; Zamorano, C.; Ribes, F.; Real, J.I. Train-induced vibration prediction in tunnels using 2D and 3D FEM models in time domain. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2015, 49, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Yao, X.; Huang, H.; Ge, S. Measurement and analysis of track-tunnel-stratum vibration during subway operation. Vib. Meas. Diagn. 2018, 38, 260–265+416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishchenko, O.; Novikov, L.; Ponomarenko, I.; Konoval, V.; Kinasz, R.; Ishchenko, K. Blast wave interaction during explosive detonation in a variable cross-sectional charge. Min. Miner. Depos. 2024, 18, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measurement Point | Max (dB) | Min (dB) | Mean (dB) | Standard Deviation | Range (dB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Track Bed | 89.0 | 78.0 | 83.6 | 2.7 | 11.0 |

| Tunnel Wall | 77.1 | 71.4 | 73.7 | 1.7 | 5.6 |

| Layer | Thickness (m) | Depth (m) | Materials | Density (g/cm3) | Shear Wave Velocity (m/s) | Dynamic Young’s Modulus (MPa) | Poisson’s Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ①-1 | 0.7 | 0.7 | Filled soil | 1.80 | 111.8 | 67.4 | 0.50 |

| ②-1 | 2.9 | 3.6 | Silty clay | 1.86 | 118.4 | 78.3 | 0.50 |

| ③ | 3.9 | 7.5 | Sandy silt | 1.93 | 153.9 | 137.3 | 0.50 |

| ④-1 | 10.3 | 17.8 | Mud clay | 1.72 | 158.5 | 129.2 | 0.49 |

| ⑤-1 | 8.7 | 26.5 | Clay | 1.72 | 158.5 | 129.2 | 0.49 |

| ⑥ | 4 | 30.5 | Yellowish silty clay | 1.86 | 209.7 | 244.3 | 0.49 |

| ⑦-1 | 3.5 | 34 | Silty clay | 1.86 | 209.7 | 244.3 | 0.49 |

| ⑦-2 | 7.5 | 41.5 | Silty clay with silt | 1.95 | 235.9 | 323.3 | 0.49 |

| Distance (m) | Mean Value of FEM Results (dB) | Mean Value of Field Measurement Results (dB) | Difference (dB) | Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 61.6 | 67.1 | −5.5 | −8.27 |

| 4 | 60.4 | 65.3 | −4.9 | −7.50 |

| 8 | 64.7 | 66.5 | −1.8 | −2.66 |

| 12 | 63.6 | 63.2 | 0.4 | 0.58 |

| 18 | 61.4 | 62.5 | −1.1 | −1.80 |

| 30 | 61.2 | 60.8 | 0.4 | 0.64 |

| Parameter | Scenario 1 (Different Burial Depths) | Scenario 2 (Different Tunnel Diameters) | Scenario 3 (Different Shear Wave Velocities) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Burial depth | 9 m, 18 m, 27 m, 36 m | 18 m | 18 m |

| Tunnel diameter | 6 m | 6 m, 9 m, 12 m, 15 m | 6 m |

| Soil type | Muddy clay | Muddy clay | Silty clay, Muddy clay, Yellowish silty clay, Silty clay with silt |

| Tunnel section | Circular | Circular | Circular |

| Track/Lining | C30 | C30 | C30 |

| Load excitation | 1/3 Octave Gaussian Harmonic | 1/3 Octave Gaussian Harmonic | 1/3 Octave Gaussian Harmonic |

| Load amplitude | 10 kN | 10 kN | 10 kN |

| Model size | Horizontal 50 m, Vertical 30 m | Horizontal 50 m, Vertical 30 m | Horizontal 50 m, Vertical 30 m |

| Frequency (Hz) | mki | R2 | 95% CI (Lower) | 95% CI (Upper) | Frequency (Hz) | mki | R2 | 95% CI (Lower) | 95% CI (Upper) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −0.276 | 0.765 | −0.740 | 0.189 | 16 | −0.286 | 0.907 | −0.565 | −0.007 |

| 1.25 | −0.300 | 0.731 | −0.852 | 0.253 | 20 | −0.415 | 0.990 | −0.541 | −0.289 |

| 1.6 | −0.342 | 0.731 | −0.973 | 0.289 | 25 | −0.460 | 0.965 | −0.728 | −0.191 |

| 2 | −0.356 | 0.949 | −0.607 | −0.105 | 32 | −0.475 | 0.952 | −0.798 | −0.152 |

| 2.5 | −0.281 | 0.997 | −0.332 | −0.231 | 40 | −0.428 | 0.971 | −0.651 | −0.204 |

| 3.2 | −0.186 | 0.943 | −0.325 | −0.047 | 50 | −0.201 | 0.971 | −0.306 | −0.095 |

| 4 | −0.304 | 0.957 | −0.500 | −0.109 | 64 | −0.219 | 0.887 | −0.456 | 0.019 |

| 5 | −0.260 | 0.986 | −0.353 | −0.167 | 80 | −0.179 | 0.923 | −0.337 | −0.022 |

| 6.4 | −0.181 | 0.961 | −0.292 | −0.069 | 100 | −0.250 | 0.901 | −0.502 | 0.002 |

| 8 | −0.149 | 0.907 | −0.293 | −0.004 | 125 | −0.324 | 0.988 | −0.434 | −0.214 |

| 10 | −0.222 | 0.921 | −0.421 | −0.024 | 160 | −0.217 | 0.949 | −0.370 | −0.063 |

| 12.5 | −0.256 | 0.855 | −0.577 | 0.064 | 200 | −0.140 | 0.871 | −0.304 | 0.024 |

| Frequency (Hz) | dki | R2 | 95% CI (Lower) | 95% CI (Upper) | Frequency (Hz) | dki | R2 | 95% CI (Lower) | 95% CI (Upper) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −0.297 | 0.996 | −0.352 | −0.242 | 16 | −0.961 | 0.884 | −2.018 | 0.097 |

| 1.25 | −0.281 | 0.998 | −0.322 | −0.240 | 20 | −0.987 | 0.968 | −1.534 | −0.441 |

| 1.6 | −0.257 | 0.993 | −0.322 | −0.192 | 25 | −1.034 | 0.978 | −1.509 | −0.560 |

| 2 | −0.293 | 0.996 | −0.351 | −0.235 | 32 | −1.026 | 0.991 | −1.331 | −0.720 |

| 2.5 | −0.386 | 0.980 | −0.555 | −0.216 | 40 | −0.728 | 0.856 | −1.635 | 0.179 |

| 3.2 | −0.439 | 0.899 | −0.885 | 0.008 | 50 | −0.826 | 0.847 | −1.895 | 0.244 |

| 4 | −0.542 | 0.717 | −1.578 | 0.494 | 64 | −1.106 | 0.997 | −1.291 | −0.921 |

| 5 | −0.560 | 0.809 | −1.387 | 0.268 | 80 | −1.311 | 1.000 | −1.346 | −1.275 |

| 6.4 | −0.631 | 0.870 | −1.373 | 0.112 | 100 | −1.189 | 0.980 | −1.704 | −0.674 |

| 8 | −0.767 | 0.851 | −1.744 | 0.210 | 125 | −1.471 | 0.993 | −1.842 | −1.100 |

| 10 | −0.925 | 0.845 | −2.133 | 0.282 | 160 | −1.447 | 0.946 | −2.497 | −0.398 |

| 12.5 | −0.931 | 0.862 | −2.065 | 0.203 | 200 | −1.097 | 0.959 | −1.786 | −0.407 |

| Frequency (Hz) | tki | R2 | 95% CI (Lower) | 95% CI (Upper) | Frequency (Hz) | tki | R2 | 95% CI (Lower) | 95% CI (Upper) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −0.105 | 0.998 | −0.119 | −0.090 | 16 | −0.020 | 0.938 | −0.035 | −0.004 |

| 1.25 | −0.090 | 0.987 | −0.121 | −0.059 | 20 | −0.025 | 0.998 | −0.029 | −0.021 |

| 1.6 | −0.068 | 0.978 | −0.099 | −0.037 | 25 | −0.030 | 0.993 | −0.037 | −0.022 |

| 2 | −0.048 | 0.980 | −0.069 | −0.027 | 32 | −0.021 | 0.937 | −0.038 | −0.004 |

| 2.5 | −0.050 | 0.990 | −0.065 | −0.034 | 40 | 0.001 | 0.029 | −0.013 | 0.015 |

| 3.2 | −0.048 | 1.000 | −0.051 | −0.045 | 50 | 0.000 | 0.002 | −0.029 | 0.028 |

| 4 | −0.076 | 0.984 | −0.105 | −0.046 | 64 | −0.011 | 0.993 | −0.014 | −0.008 |

| 5 | −0.086 | 0.997 | −0.100 | −0.072 | 80 | −0.004 | 0.452 | −0.019 | 0.010 |

| 6.4 | −0.081 | 0.991 | −0.105 | −0.057 | 100 | −0.012 | 0.999 | −0.013 | −0.010 |

| 8 | −0.053 | 0.967 | −0.084 | −0.023 | 125 | −0.019 | 0.984 | −0.027 | −0.012 |

| 10 | −0.032 | 0.957 | −0.053 | −0.012 | 160 | −0.014 | 0.988 | −0.019 | −0.009 |

| 12.5 | −0.025 | 0.932 | −0.046 | −0.005 | 200 | −0.010 | 0.992 | −0.013 | −0.007 |

| Frequency (Hz) | vki | R2 | 95% CI (Lower) | 95% CI (Upper) | Frequency (Hz) | vki | R2 | 95% CI (Lower) | 95% CI (Upper) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.325 | 0.561 | 0.090 | 0.559 | 16 | 0.144 | 0.486 | 0.023 | 0.264 |

| 1.25 | 0.069 | 0.040 | −0.205 | 0.343 | 20 | 0.124 | 0.526 | 0.028 | 0.220 |

| 1.6 | 0.247 | 0.531 | 0.058 | 0.437 | 25 | 0.052 | 0.237 | −0.024 | 0.128 |

| 2 | 0.440 | 0.878 | 0.307 | 0.574 | 32 | 0.042 | 0.157 | −0.038 | 0.122 |

| 2.5 | 0.056 | 0.046 | −0.151 | 0.262 | 40 | 0.179 | 0.575 | 0.054 | 0.305 |

| 3.2 | 0.100 | 0.144 | −0.099 | 0.300 | 50 | 0.076 | 0.225 | −0.039 | 0.192 |

| 4 | 0.076 | 0.320 | −0.014 | 0.166 | 64 | 0.083 | 0.279 | −0.026 | 0.193 |

| 5 | 0.135 | 0.153 | −0.124 | 0.394 | 80 | 0.055 | 0.536 | 0.013 | 0.096 |

| 6.4 | 0.321 | 0.740 | 0.166 | 0.476 | 100 | 0.091 | 0.782 | 0.052 | 0.131 |

| 8 | 0.038 | 0.042 | −0.111 | 0.187 | 125 | 0.054 | 0.520 | 0.012 | 0.096 |

| 10 | 0.046 | 0.096 | −0.069 | 0.162 | 160 | 0.014 | 0.046 | −0.038 | 0.067 |

| 12.5 | 0.018 | 0.010 | −0.127 | 0.164 | 200 | 0.016 | 0.052 | −0.040 | 0.072 |

| h0/m | δm | Δ/dB |

|---|---|---|

| 9 | 0.89 | −1.02 |

| 12 | 0.92 | −0.76 |

| 15 | 0.93 | −0.60 |

| 18 | 0.94 | −0.50 |

| 21 | 0.95 | −0.42 |

| 24 | 0.96 | −0.37 |

| 27 | 0.96 | −0.33 |

| 30 | 0.97 | −0.29 |

| 33 | 0.97 | −0.27 |

| 36 | 0.97 | −0.24 |

| Average | 0.95 | −0.48 |

| d0/m | δ | Δ/dB |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | 0.86 | −1.34 |

| 7 | 0.88 | −1.15 |

| 8 | 0.89 | −1.00 |

| 9 | 0.90 | −0.89 |

| 10 | 0.91 | −0.81 |

| 11 | 0.92 | −0.74 |

| 12 | 0.92 | −0.68 |

| 13 | 0.93 | −0.63 |

| 14 | 0.93 | −0.59 |

| 15 | 0.94 | −0.56 |

| Average | 0.91 | −0.84 |

| Vs0/(m/s) | δv | Δ/dB |

|---|---|---|

| 120 | 0.992 | −0.073 |

| 130 | 0.992 | −0.067 |

| 140 | 0.993 | −0.062 |

| 150 | 0.993 | −0.058 |

| 160 | 0.994 | −0.054 |

| 170 | 0.994 | −0.051 |

| 180 | 0.994 | −0.048 |

| 190 | 0.995 | −0.046 |

| 200 | 0.995 | −0.044 |

| 210 | 0.995 | −0.041 |

| 220 | 0.995 | −0.040 |

| 230 | 0.996 | −0.038 |

| 240 | 0.996 | −0.036 |

| Average | 0.994 | −0.051 |

| Speed (km/h) | Measured Z Vibration Level (dB) | Predicted Z Vibration Level (dB) | Difference (dB) | Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 105 | 84.8 | 84.8 | 0.0 | 0.0% |

| 110 | 85.0 | 85.2 | 0.2 | 0.2% |

| 115 | 85.2 | 85.6 | 0.4 | 0.5% |

| 121 | 86.9 | 86.1 | −0.8 | −0.9% |

| 125 | 86.9 | 86.3 | −0.5 | −0.6% |

| 130 | 87.9 | 86.7 | −1.2 | −1.3% |

| 135 | 85.4 | 87.0 | 1.6 | 1.9% |

| 142 | 87.3 | 87.4 | 0.2 | 0.2% |

| 153 | 88.5 | 88.1 | −0.4 | −0.5% |

| 165 | 90.9 | 88.8 | −2.1 | −2.4% |

| Main Parameter | A Section of a Subway Line in Shanghai | A Section of Shanghai Metro Line 9 |

|---|---|---|

| Tunnel burial depth (m) | 12 | 15 |

| Tunnel diameter (m) | 6.2 | 6.6 |

| Soil equivalent shear wave velocity (m/s) | 152.1 | 151.0 |

| speed (km/h) | 40 | 60 |

| Is it a curve segment? | No | Yes |

| Measured Z Vibration Level | Predicted Z Vibration Level Before Correction | Error Before Correction | Predicted Z Vibration Level After Correction | Error After Correction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 84.2 | 75.7 | 10.1% | 79.8 | 5.2% |

| Distance (m) | Depth 9 m~18 m | Depth 18 m~27 m | Depth 27 m~36 m | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | −0.72 | −0.41 | −0.27 | −0.47 |

| 10 | −0.95 | −0.58 | −0.23 | −0.59 |

| 20 | −0.24 | −0.54 | −0.57 | −0.45 |

| 30 | −0.08 | −0.21 | −0.37 | −0.22 |

| 40 | −0.18 | −0.08 | −0.15 | −0.14 |

| 50 | −0.25 | −0.12 | −0.05 | −0.14 |

| 60 | −0.31 | −0.18 | −0.05 | −0.18 |

| 70 | −0.35 | −0.15 | −0.09 | −0.20 |

| 80 | −0.14 | −0.41 | −0.08 | −0.21 |

| Mean | −0.36 | −0.30 | −0.21 | −0.29 |

| Distance (m) | Diameter 6 m~9 m | Diameter 9 m~12 m | Diameter 12 m~15 m | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | −0.67 | −0.39 | 0.32 | −0.25 |

| 10 | −1.28 | −0.69 | 0.12 | −0.61 |

| 20 | −2.35 | −0.58 | −0.33 | −1.09 |

| 30 | −1.17 | −0.48 | −1.15 | −0.93 |

| 40 | −0.79 | −0.18 | 0.09 | −0.29 |

| 50 | −0.77 | −0.06 | 0.34 | −0.17 |

| 60 | −0.85 | 0.00 | 0.40 | −0.15 |

| 70 | −0.79 | −0.10 | 0.19 | −0.23 |

| 80 | −0.80 | −0.55 | 0.94 | −0.14 |

| Mean | −0.86 | −0.23 | 0.14 | −0.32 |

| Distance (m) | Vs 118.4~158.5 m/s | Vs 158.5~209.7 m/s | Vs 209.7~235.9 m/s | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | −0.47 | −0.57 | −0.48 | −0.51 |

| 10 | −0.41 | −0.38 | −0.33 | −0.37 |

| 20 | −0.40 | −0.47 | −0.47 | −0.45 |

| 30 | −0.29 | −0.35 | −0.38 | −0.34 |

| 40 | −0.26 | −0.30 | −0.33 | −0.30 |

| 50 | −0.23 | −0.32 | −0.36 | −0.30 |

| 60 | −0.26 | −0.34 | −0.36 | −0.32 |

| 70 | −0.19 | −0.28 | −0.34 | −0.27 |

| 80 | −0.14 | −0.29 | −0.43 | −0.29 |

| Mean | −0.29 | −0.37 | −0.39 | −0.35 |

| Speed (km/h) | Peak Acceleration of Measurement Points (m/s2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Track Bed Z-Direction | Track Bed X-Direction | Tunnel Wall Z-Direction | Tunnel Wall X-Direction | |

| 105 | 1.35 | 1.56 | 0.22 | 0.11 |

| 110 | 1.22 | 1.74 | 0.24 | 0.10 |

| 115 | 1.46 | 1.63 | 0.25 | 0.11 |

| 121 | 1.35 | 1.70 | 0.25 | 0.14 |

| 125 | 1.29 | 1.87 | 0.23 | 0.14 |

| 130 | 1.58 | 1.58 | 0.26 | 0.16 |

| 135 | 1.54 | 1.69 | 0.24 | 0.10 |

| 142 | 1.69 | 1.91 | 0.28 | 0.15 |

| 153 | 1.80 | 2.60 | 0.29 | 0.22 |

| 165 | 1.94 | 2.24 | 0.30 | 0.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, F.; Li, P.; Zong, G.; Yu, L.; Yang, J.; Zhao, P. An Excitation Modification Method for Predicting Subway-Induced Vibrations of Unopened Lines. Buildings 2026, 16, 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020353

Zhang F, Li P, Zong G, Yu L, Yang J, Zhao P. An Excitation Modification Method for Predicting Subway-Induced Vibrations of Unopened Lines. Buildings. 2026; 16(2):353. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020353

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Fengyu, Peizhen Li, Gang Zong, Lepeng Yu, Jinping Yang, and Peng Zhao. 2026. "An Excitation Modification Method for Predicting Subway-Induced Vibrations of Unopened Lines" Buildings 16, no. 2: 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020353

APA StyleZhang, F., Li, P., Zong, G., Yu, L., Yang, J., & Zhao, P. (2026). An Excitation Modification Method for Predicting Subway-Induced Vibrations of Unopened Lines. Buildings, 16(2), 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020353