Abstract

Fly ash–based geopolymers have emerged as a promising alternative to ordinary Portland cement, offering high mechanical strength and reduced environmental footprint. However, they are often limited by significant shrinkage and strength degradation when subjected to elevated temperatures. To enhance their thermomechanical performance and thermal stability, this study investigates the effects of mix proportioning parameters, alkali activator type, and thermal shock on performance deterioration. Compressive strength was evaluated for sodium- and potassium-activated fly ash geopolymer composites as a function of alkaline activator (AA) ratios, both under ambient curing and after exposure to the ISO 834 standard fire curve for 1 and 2 h. Volume change, mass loss, and density variation were analysed to interpret mechanical behaviour and relate it to structural transformations, while XRF, XRD, SEM, and particle size distribution were employed for material characterisation. Results indicate that rapid temperature changes, whether from thermal shock or high fire-heating rates, induced notable additional thermal degradation. Sodium activation achieved the highest compressive strength retention of 145% at one hour of firing, while potassium activation showed superior thermal stability with delayed densification, reaching 154% strength retention at two hours. Furthermore, SiO2/M2O ratio exerted the strongest influence on both mechanical and thermomechanical performance. Overall, the findings highlight that the activator type, SiO2/M2O ratio, and rapid temperature changes collectively exert strong control over the thermomechanical and thermophysical response of fly ash geopolymers at elevated temperatures.

1. Introduction

Fly ash is a byproduct of coal combustion, generated when coal is burned in powerplants. The chemical composition of fly ash primarily consists of silica (SiO2) and alumina (Al2O3), classifying it as aluminosilicate material. This composition enables its use as a binder through a process known as ‘geopolymerisation’, which involves the alkali activation of the aluminosilicate material [1].

During alkali activation, the amorphous content of fly ash dissolves in a highly alkaline solution. This dissolution process releases silicate and aluminate monomers into the solution, which then undergo hydrolysis and polycondensation, leading to the formation of a 3D sodium (N-A-S-H) or potassium (K-A-S-H) aluminosilicate gel [2].

During polycondensation of the reacted soluble silicate and aluminate species, an inorganic viscous substance (geopolymer gel) begins to form, simultaneously binding to unreacted particles, and setting and hardening [3,4]. During this process, the quality of curing, influenced by temperature and humidity, is one of the critical factors contributing to the mechanical properties of FA geopolymers.

Curing at high temperatures accelerates polymerisation of dissolved aluminosilicate materials, promoting the formation of a three-dimensional aluminosilicate network. This method of curing resulted in enhanced densification of the geopolymer’s matrix, consequently improving the mechanical strength [5]. However, the constrained practical applicability of heat curing remains a serious obstacle to widespread geopolymer adoption. Ambient temperature curing, on the other hand, presents a more adoptable approach for field applications. While this method typically results in reduced strength development compared to elevated temperature curing, the incorporation of calcium-rich additives was found to accelerate early-age strength development, which minimised the strength differential between the two curing methodologies [6].

The mechanical strength of fly ash geopolymers is fundamentally governed by the selection of alkaline activator composition. Fly ash geopolymers are typically activated using sodium-based or potassium-based alkali solutions. Compressive strength results show that sodium-activated geopolymers generally achieve 50–60 MPa, whereas potassium-activated systems reach 30–40 MPa, respectively [7,8]. The superior mechanical strength noted in sodium-activated fly ash geopolymer is primarily attributed to the smaller sodium ionic radius and higher mobility, which promote greater liberation of silicate and aluminate monomers from the aluminosilicate precursor. On the contrary, the larger potassium ion and lower hydration energy may contribute to the development of a more open and interconnected geopolymer framework which is characteristically associated with enhanced long-term durability and reduced brittleness compared to sodium-activated systems [9,10,11,12].

Besides the effect of alkaline activator type, mix proportioning ratios are among the most critical factors influencing the mechanical performance, workability, and setting of fly ash-based geopolymers. Specifically, the ratio of water to binder (W/B), total alkaline activator to binder (AA/B), as well as the silica-to-alkali oxide ratio (SiO2/M2O), can remarkably influence the dissolution of aluminosilicate materials and the development of the geopolymer gel framework, consequently, dictating the mechanical strength of the final product [13,14,15,16,17,18].

In the geopolymer mix, the influence of individual ratio components must be characterised to optimise material performance and establish reproducible formulations. This analysis is challenged when water content is incorporated within multiple parameters rather than being isolated to the W/B ratio alone. For instance, both molarity and silicate-to-hydroxide ratio inherently contain water contributions. This prevents isolating the influence of water from these parameters. The influence from the embedded water in these parameters can be mistakenly attributed to other variables, resulting in confounding results. This is specifically a concern in parametric studies where one factor varies while others remain constant. When water content is linked to changes in molarity or solution ratios, adjusting one variable that embeds water, may indirectly affect multiple others, which compromise the reliability of the comparative study. Hence, isolating water to W/B ratio only, and expressing other ratios based on solids provides a more rigorous and consistent approach [19,20]. This methodological consideration becomes particularly important when evaluating geopolymer performance under varying conditions, such as elevated temperature exposure.

Studies examining FA geopolymers at elevated temperatures have demonstrated excellent retention of thermomechanical properties ascribed to the thermal resilience of the three-dimensional aluminosilicate network structure, formation of crystalline phases such as nepheline and leucite, and the occurrence of viscous sintering processes that densify the matrix above 600 °C [6,21,22]. However, despite the excellent thermomechanical performance exhibited by FA geopolymers, their high thermal shrinkage at elevated temperatures remains a serious drawback that compromises its dimensional stability [21,23].

Vickers, et al. [24] synthesised FA geopolymers and subjected them to sintering temperatures up to 1000 °C for 1 h. The results demonstrated a severe increase in volumetric shrinkage, rising from approximately 5% at 600 °C, corresponding to the onset of sintering, to ~15% at 1000 °C. In a subsequent investigation, Vickers, et al. [25] reported a thermal shrinkage of 11.8% for fly ash exposed to a temperature of 1000 °C. Similarly, Klima, et al. [26] observed a volumetric shrinkage of approximately 8.5% after exposing fly ash-based geopolymer specimens to a temperature of 1000 °C for 1 h. The severe thermal shrinkage reported in fly ash geopolymers at elevated temperatures is primarily ascribed to viscous sintering. During this process, unreacted aluminosilicate phases undergo reaction at elevated temperatures to produce additional geopolymer gel that fills the voids in the microstructure, which subsequently impacts the dimensional stability [27,28,29].

A thermomechanical analysis of FA geopolymers revealed important trade-offs between thermomechanical performance and compromised dimensional stability [8]. The study demonstrates that the superior residual strength of fly ash geopolymer mixes at elevated temperatures was accompanied by significantly higher thermal shrinkage compared to mixes with lower residual strength. This finding indicates an inherent trade-off where improved residual strength is achieved at the expense of dimensional stability under thermal loading.

Several studies in the literature have conducted comparative assessment on thermomechanical performance between sodium and potassium alkaline activators under elevated temperatures and noted key differences [7,30,31,32,33,34]. In the experiment conducted by Hosan, et al. [35], the thermomechanical performance was investigated at temperatures of up to 800 °C at a heating rate of 5 °C/min. The results revealed that sodium geopolymers achieved the highest compressive strength at ambient temperature with signs of minor degradation at 600 °C, while potassium geopolymers recorded the highest residual compressive strength, lower mass loss and thermal shrinkage with no signs of deterioration until 800 °C. In a similar study, Lahoti, et al. [36] employed a heating rate of 10 °C/min, and similar results to the Hosan et al. study [35] have been reported where potassium had increased strength retention over sodium. However, beyond 800 °C, the potassium was noted to continue increasing in strength, which opposes Hosan’s findings.

Research demonstrates that higher heating rates, such as those encountered in fire conditions, lead to different thermal responses and degradation patterns compared to slow heating, including crystalline phase formation, gel viscosity changes, and densification mechanisms [30,31,37]. Hence, studies employing slow heating rates may not accurately represent the impact of fire conditions, even when reaching nominal fire temperatures in the range of 1000–1100 °C, due to the significantly slower heating rates compared to actual fire scenarios.

Analogous to heating rate effects, cooling rate in heated specimens is also anticipated to exert considerable influence on thermal degradation mechanisms. Huang, et al. [38] assessed the effects of different cooling methods on thermally exposed geopolymers and reported that water quenching, as well as the temperature at which quenching was applied, had a pronounced impact on mass loss and strength degradation. For instance, the study demonstrated that quenching in water at 400 °C and 1000 °C, with a heating rate of 4 °C/min, exhibited a higher strength reduction of 3.9% and 14.2%, respectively, compared with their naturally cooled counterparts. Similar findings have been reported in the literature where rapid cooling by water exacerbated strength degradation [39,40,41].

This reduction in mechanical performance is ascribed to thermally induced stresses arising from non-uniform thermal contraction caused by steep temperature gradients within the specimen [42,43]. As such, the impacts from natural cooling protocol, characterised by gradual temperature reduction, may inadequately reflect the severe thermal shock imposed by rapid cooling methods such as water quenching or thermal spray systems. This becomes further critical when both elevated heating rates and rapid cooling rates are employed concurrently to simulate the impacts of real fire events followed by extinguishment on the densification of FA geopolymers. A representative fire extinguishment rapid cooling rate must be employed.

Although extensive research has been conducted on fly ash geopolymers, notable gaps remain in understanding their thermomechanical performance under realistic fire conditions. Previous studies assessing the thermal response of geopolymers have predominantly focused on heat-cured rather than ambient-cured fly ash geopolymers [27,28,36,44,45,46]. This emphasis limits the applicability of current findings to real construction environments, where ambient curing is generally preferred for economic and sustainability reasons, whereas heat curing requires substantially higher energy input [5].

Furthermore, existing investigations on thermomechanical performance of FA geopolymers have mostly employed controlled laboratory heating rates of 2–5 °C/min with natural cooling protocols [28,36,45,46,47,48], which fundamentally do not replicate the rapid, non-linear temperature escalation characteristic of actual structural fires. This methodological limitation creates a critical disconnect between laboratory data and real-world fire performance.

While previous investigations have examined sodium-activated [28,49,50] and potassium-activated [51] fly ash geopolymers independently, and even both activator types together [12,35], there is a lack of comparative thermomechanical assessment between the two types of activator under identical fire-exposure protocols while also accounting for the isolated influence of key formulation parameters. In particular, the differential effects of the activator modulus (SiO2/M2O), the total activator oxides-to-binder ratio, and the reactive Si/Al molar ratio of the mix on the thermal response of sodium- versus potassium-activated fly ash geopolymers.

The research gap is further compounded by the lack of investigation into thermally induced degradation mechanisms of fly ash geopolymers subjected to thermal shock subsequent to fire exposure. Despite several investigations having explored the thermal shock impacts of geopolymers using water quenching [38,40,43,52,53,54,55,56], there remains a conspicuous deficiency in assessing the combined thermal loading scenario of rapid ISO 834 fire heating followed by thermal shock through water quenching. A dynamic heating rate that reflects realistic fire-representative thermal profiles is essential to accurately simulate the rapid temperature escalations and complex thermal cycling characteristic of actual structural fire scenarios.

Therefore, this study aims to address the identified research gaps through the following objectives:

- -

- Investigate the influence of alkaline activator type (sodium vs. potassium) on the thermomechanical performance, dimensional and mass stability of ambient-cured fly ash geopolymers under identical ISO 834 fire exposure conditions for both 1 h and 2 h heating durations.

- -

- Conduct a comparative assessment of fundamental mix proportioning parameters and their isolated effects on thermal performance and residual mechanical properties of ambient-cured fly ash geopolymers following fire exposure.

- -

- Evaluate the effects of thermal shock, induced by water quenching immediately after fire-rate heating, on residual strength, densification mechanisms, and overall structural integrity.

This study presents direct comparative investigation of sodium- and potassium-activated, ambient-cured fly ash geopolymers subjected to extreme dynamic temperature change representative of ISO 834 fire exposure, evaluating microstructural evolution, thermomechanical performance and overall thermal stability, while explicitly correlating these responses with activator type and the isolated influence of fundamental mix design parameters. Furthermore, the study introduces a combined thermal loading protocol that couples rapid ISO 834 fire heating with immediate water-quenching thermal shock, therefore elucidating post-fire degradation mechanisms that are not captured by conventional single-stage thermal testing regimes. Collectively, these contributions establish explicit, design-oriented links between alkali chemistry, mix proportioning, and real-world post-fire performance, enabling engineers and researchers to optimise ambient-cured fly ash geopolymers for fire-resistant construction applications with confidence in their thermal stability, mechanical strength retention, and dimensional integrity under combined thermal loading. These findings support the development of durable, sustainable geopolymer materials with excellent fire resistance, contributing valuable knowledge toward their wider adoption in fire-safe building applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

Low-calcium fly ash and ground granulated blast-furnace slag (GGBS) were employed as binders. The fly ash was classified as class F according to ASTM C618 [57] specifications. Sodium-based alkaline activators were prepared from sodium silicate solution (Na2SiO3, grade D with a modulus ratio of 2 (Ms = SiO2/Na2O; SiO2 = 29%, Na2O = 15% by mass), combined with dissolved sodium hydroxide pellets of ≥99% purity. Likewise, potassium-based activators were produced using potassium silicate solution (Kasil 2040, grade D) supplied by a modulus ratio of 2 (Ms = SiO2/K2O; SiO2 = 27%, K2O = 13.3% by mass) and mixed with dissolved potassium hydroxide pellets of ≥90% purity. Hydroxide pellets and silicate solutions for both types of activators were supplied by Redox Pty Ltd., Melbourne, VIC, Australia and Potters Industries Pty Ltd., Melbourne, VIC, Australia, respectively.

2.2. Material Characterisation

2.2.1. X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF)

The chemical composition of FA and slag was determined using X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) to quantify the oxide content and assess the suitability of these materials for geopolymer synthesis. The quantification is essential for characterising the silica and alumina content, which directly influence the geopolymerisation process and final mechanical properties. The composition results are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of binders (%).

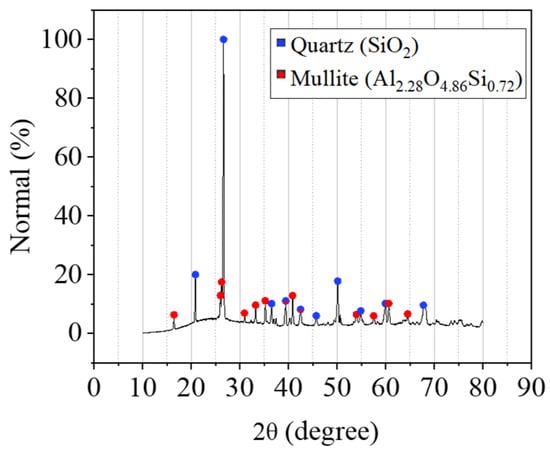

2.2.2. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

XRD (X-ray Diffraction) analysis was conducted using Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer to determine the mineral phase composition of raw FA powder. The XRD pattern shown in Figure 1 was obtained with CuKα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å) scanning the 2θ range from 10° to 80° at a step size of 0.02°, with a count time of 1 s per step and sample rotation at 15 rpm. The crystalline mineralogical composition primarily comprises Quartz and Mullite. Their prominent peaks are presented at 16, 20, 26, and 50°. The amorphous fraction manifests as a broad, undefined peak in the XRD background in the range of 15 to 30°. Similar findings were reported in other studies [58,59,60]. Quantitative XRD (QXRD) analysis was performed using Rietveld refinement in Bruker’s TOPAS software V7.13, with the amorphous peak identified via a PV function. Results of the quantitative phase analysis are presented in Table 2.

Figure 1.

XRD pattern and SEM imaging of FA.

Table 2.

QXRD analysis of FA powder.

Fly ash reactivity was characterised by determining reactive silica and alumina contents through subtraction of crystalline phases (quantified by XRD analysis) from total oxide compositions (measured by XRF). The resulting Si/Al molar ratios were 1.82 for total content and 3.35 for reactive (amorphous) content, and are presented in Table 3. The total reactive amorphous content of fly ash plays a critical role in geopolymer gel formation, as this fraction participates in dissolution and re-precipitation to form the binding network [59]. Studies that isolate glassy from crystalline phases generally indicate that reactive contents of approximately 50–70% are desired to develop a mechanically efficient geopolymer gel, while lower values reduce gel volume, increase unreacted residue and compromise strength and durability [21,59,61]. In this context, the reactive content of ~53% measured for the fly ash in the present study lies at the lower bound of this envelope, which implies sufficient but limited gel formation and notable presence of unreacted content.

Table 3.

Fly ash reactive content based on combined XRF and quantitative XRD analysis.

The reactive Si/Al ratio is another factor that has a significant influence on mechanical and thermomechanical performance of FA geopolymers [62,63,64,65]. A previous investigation by [21] examined reactive Si/Al ratios in the range of 2–3 and reported pronounced effects on high-temperature behaviour. Ratios towards the lower bound tend to yield more Al-rich, denser matrix but also lead to greater susceptibility to shrinkage-induced cracking and rapid strength loss after heating. On the other hand, higher reactive Si/Al ratios promote more silica-rich gels that can exhibit improved strength retention through viscous sintering. The reactive Si/Al ratio of 3.35 in this study sits near the upper end of this interval, suggesting that, in combination with the relatively low reactive content (~53%), the matrix is predisposed to silica-rich gel formation and associated thermal expansion phenomena.

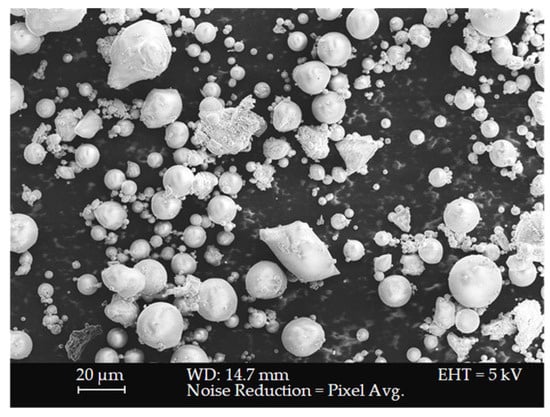

2.2.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Morphological analysis of the fly ash powder was performed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with a ZEISS SUPRA 55 VP field emission microscope. Sample preparation for the powders excluded gold coating; however, the fly ash geopolymer samples were gold-coated using a Quorum Q150R ES Plus sputter coater to eliminate charging effects and optimise image contrast and resolution. As depicted in Figure 2, the SEM scan displays a collection of particles that are predominantly spherical in shape with smooth surfaces. These spherical particles, known as cenospheres and plerospheres with a high surface area, are formed during the combustion process at elevated temperatures and are characteristic of fly ash morphology [66].

Figure 2.

SEM micrograph of FA powder.

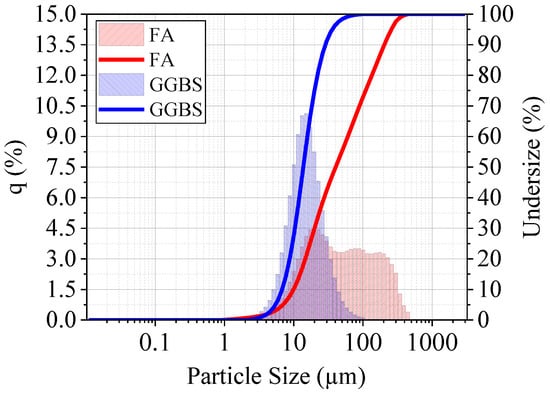

2.2.4. Particle Size Analysis (PSA)

Particle size analysis was measured using laser diffraction method with a Horiba particle size analyser. The result for the FA and GGBS powder particle size analysis is shown in Figure 3. The Laser diffraction analysis revealed median particle sizes of 40.39 μm for FA and 13.77 μm for ground GGBS, with corresponding D10 and D90 values of 9.94 and 204.16 μm for FA, and 6.79 and 28.76 μm for GGBS, respectively.

Figure 3.

Particle size analysis of FA and GGBS.

2.2.5. Gas Pycnometry

The specific gravity of loose fly ash powder was measured using Micromeritics AccuPyc 1330 via helium gas displacement methodology. The measurement employs successive cycles of gas purging and pressure equilibration to determine absolute particle density. The measured specific gravity of FA was 2.22.

2.3. Synthesis of FA Geopolymer

Sodium- and potassium-based FA geopolymer mixes have been proportioned based on 3 intrinsic ratios: total alkali activator’s oxides content-to-binder ratio (AA/B), activator’s molar ratio of oxides (SiO2/M2O), and water-to-binder ratio (W/B). Sodium-based activators require higher water content to achieve workability comparable to potassium-activated geopolymers [10,67,68]. Accordingly, the water-to-binder (W/B) ratio was set at 25% for potassium-activated mixes and increased to 30% for sodium-activated mixes (5% higher than the potassium systems), based on mini-cone spread results following procedures reported in the literature [69,70]. The potassium mix designated KW25C20R1.2 achieved an average spread of 114 mm, which is considered practical for applications such as bonded adhesives or castable materials. Its sodium-activated counterpart recorded only 57 mm at a 25% W/B ratio but increased to 103 mm at 30%, ensuring consistent workability and practicality across all mixes.

Matching workability across formulations ensures that fresh-state behaviour remains comparable, allowing any differences in thermomechanical performance to be attributed primarily to activator chemistry rather than rheological artefacts. This adjustment does not compromise the validity of the thermomechanical comparison. Sodium-activated geopolymers inherently exhibit greater mass loss, higher thermal shrinkage, and accelerated strength degradation at elevated temperatures compared to potassium-activated systems, even when potassium mixes have higher water-to-binder ratios [14]. This indicates that the thermal performance is strongly tied to activator chemistry rather a secondary effect of water content.

Ground slag was incorporated in all mixes as it is reported to increase the mechanical strength at room temperature [6,71]. It should be noted that the binder matrix consists exclusively of fly ash and slag powders. Geopolymer mixes and their proportioning are depicted in Table 4. The first letter of mix ID stands for the type of activator (Na or K), W for W/B ratio, while C and R stand for the activator’s total oxide content and molar ratio (SiO2/M2O), respectively.

Table 4.

Mix proportion of FA geopolymer.

2.4. Mixing and Sample Preparations

Fly ash and slag were dry blended for 30 s in a Hobart N50 mixer at 281 RPM. The alkaline activator was gradually poured, with mixing interrupted at 2.5 min to scrape adherent powder from the bowl walls before continuing for an additional 1.5 min at the same speed.

The mixtures were poured into 50 × 50 × 50 mm cubic moulds following ASTM C109 [72]. Casting was performed in two stages, with each layer vibrating for 30 s to eliminate trapped air. Following consolidation, a plastic sheet was applied to the surface to prevent moisture evaporation. The fresh geopolymer specimens were then stored in an environmental chamber maintained at 25 °C and 50% relative humidity for 28 days.

2.5. Test Programme Details

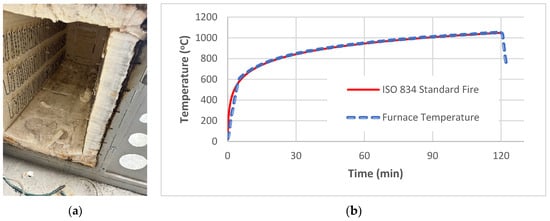

To simulate fire conditions, a horizontal Tetlow electrical furnace was utilised as shown in Figure 4a. The furnace heating rate was fabricated to follow the nominal fire curve in ISO 834 [73].

Figure 4.

(a) Electric furnace; (b) nominal fire curve vs. furnace temperature.

Nominal fire and furnace temperature curves are depicted in Figure 4b. All mixes were exposed to fire for the duration of 1 and 2 h to assess the changes in thermomechanical performance at different durations.

A Tecnotest compression machine with a loading rate of 900 N/s was used for compressive strength testing as per ASTM C109/C109M [72].

Volumetric changes were measured by a vernier calliper with an accuracy of up to two decimal places in mm. The mass was recorded using a commercial scale. Density was calculated by subdividing mass over volume where mass is measured in kg and volume in mm3. All measurements were taken before and after firing.

Thermal shock was carried out by quenching samples in water for 5 min for 1 cycle [74]. Thermal shock impact was assessed in terms of residual compressive strength, volume change, mass loss, and density change and careful visual inspection of sample’s surfaces for any signs of deterioration. All results are reported as the mean values of at least three samples for each tested parameter.

3. Results and Discussion

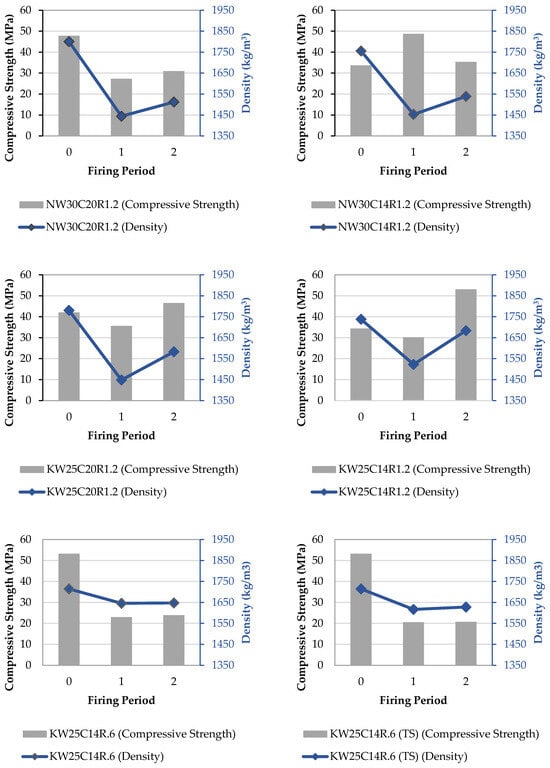

3.1. Compressive Strength

Table 5 presents the bulk density and compressive strength results obtained at ambient temperature and following thermal exposure. The highest compressive strength at ambient temperature was recorded by mix KW25C14R0.6. The mix contained the highest hydroxide solids content, and subsequently the lowest molar oxide ratio SiO2/K2O. It is noted that increasing the concentration of hydroxide to a certain extent in the activator enhances the quality of the structural reorganisation of the geopolymer gel, leading to a robust microstructure and a remarkable increase in compressive strength [68,75,76,77].

Table 5.

Compressive strength results.

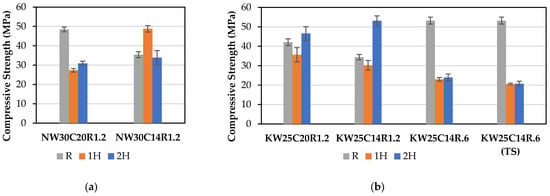

When comparing sodium- to potassium-activated mixes in Figure 5, it is noted that sodium-activated mixes recorded a higher strength at ambient temperature. This can be attributed to the better dissolution of aluminosilicate by sodium activator, which promotes geopolymer gel development and a more organised framework structure [10,36,78,79]. Additionally, results in Table 5 indicate that sodium-activated mixes had a higher bulk density compared to their corresponding potassium-activated mixes, leading to a less porous microstructure, and subsequently higher reference strength. This is in a good agreement with results reported in literature [2,9].

Figure 5.

Compressive strength of (a) sodium-activated and (b) potassium-activated FA geopolymers.

For both sodium- and potassium-activated FA geopolymers, it is observed in Figure 5 that reducing the total alkali concentration from 20% to 14% leads to a lower compressive strength. Lowering alkali concentration results in insufficient content to produce geopolymer gel, compromising the quality of geopolymer gel formation, consequently leading to a lower compressive strength [68,80].

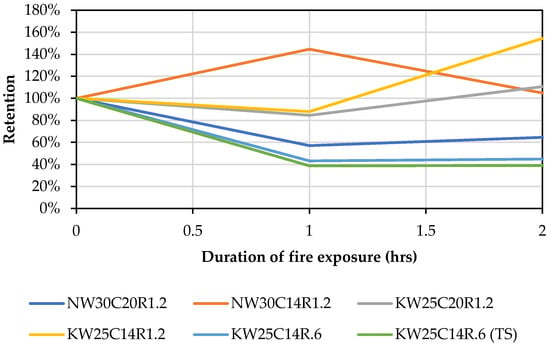

The trend from both activator types indicates that potassium mixes depicted higher retention of compressive strength post firing at 1 and 2 h. The potassium-activated mixes exhibit a lower degree of thermal deformation and sintering when compared to sodium mixes [12,36]. However, it is observed in Figure 6, and contrary to the general strength-retention trend, mix NW30C14R1.2 displayed higher retention of strength at 1 h compared with its corresponding potassium-activated geopolymer mix. This could be linked with its higher degree of shrinkage at the 1 h firing period, which resulted in densification of the microstructure at elevated temperatures.

Figure 6.

Retained compressive strength after exposure to fire at 1 and 2 h.

It is noted that in general, geopolymers with lower compressive strength at ambient temperatures achieved a higher relative residual strength at high temperatures compared to their corresponding mixes within the same type of activator. This behaviour can be explained by the fact that a compact microstructure is more susceptible to destructive thermal shrinkage than a less compact microstructure that has more voids [81]. Therefore, even if the strength was to increase at elevated temperatures, induced degradation by thermal shrinkage would offset any strength increase. Another explanation is that lower strength mixes at ambient temperature are likely to have more unreacted starting materials, which can further produce geopolymer gel at elevated temperatures [7].

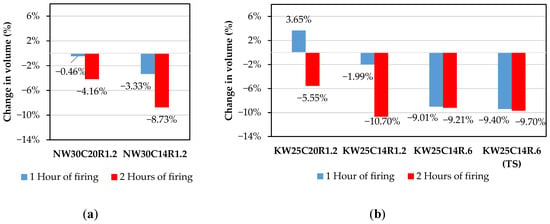

3.2. Volumetric Change

Volumetric changes including shrinkage and expansion pre- and post firing are shown in Figure 7a,b. A strong relationship can be observed between the total content of activator and thermal expansion at elevated temperatures. It is noted that mixes with activator contents of 20% exhibited a much lower shrinkage and even an expansion at the 1 h firing period, regardless of the activator’s type. On the other hand, mixes with 14% displayed higher thermal shrinkage. It is suggested that adding a higher content of activator would result in a higher content of unreacted or partially reacted silicates in the matrix which swells at elevated temperatures, causing expansion in the formation [45,62].

Figure 7.

Volume change of (a) sodium-activated and (b) potassium-activated FA geopolymers.

Despite volumetric changes ranging from an expansion of up to 3.65% to a shrinkage of 9.7%, no visible cracks were observed on the surface of any sample after firing. The absence of surface cracking likely explains why samples exhibiting significant volumetric shrinkage did not demonstrate reduced compressive strength, with the lowest recorded compressive strength remaining above 20 MPa.

Mixes with reduced activator content of 14% recorded higher shrinkage at both firing periods. The densification, driven by the viscous sintering of unreacted fly ash particles at elevated temperatures, was more pronounced for these mixes [27,28].

Therefore, mixes with lower activator content (14%) resulted in higher amounts of unreacted fly ash content that would contribute to viscous sintering at elevated temperatures leading to a higher degree of densification. Furthermore, it can be seen from Figure 7 that shrinkage also increases when reducing the molar ratio. This is attributed to the low silica content in the mix which is insufficient to alleviate shrinkage by swelling [36,82]. It is also observed that reducing the activator content had a stronger influence on shrinkage than when reducing the molar oxides ratio.

Densification of sodium-based mixes at 1 h was higher than that of their potassium-based counterparts, which is in a good agreement with the results reported in the literature [30,36]. However, at the second hour of firing, the trend inverted, such that the potassium-based mixes recorded a higher densification. This may be attributed to the delayed onset densification temperature of potassium [7]. Stronger linkages of Al-O-Al are formed when potassium is the cation, and those linkages requires higher energy to dehydroxylate, resulting in a higher temperature required for densification [30,83]. This also explains why potassium-based mixes exhibited delayed densification when compared to sodium-based counterparts.

As the densification process of potassium-based mixes took place during the second hour, unlike sodium-based mixes, the degree of densification was notably higher than its counterpart. Although potassium delays the densification process, it results in a higher degree of densification [30,34]. This in turn results in significant residual strength of potassium-activated geopolymers at the second hour of firing.

When comparing compressive strength to thermal shrinkage, it is noticed that, at the 2nd hour, the increased compressive strength is proportional to the magnitude of shrinkage. This is because densification of the mix results in a more compact microstructure, thus leading to higher compressive strength. However, this proportional relationship is disrupted under severe shrinkage, where excessive thermal stresses induce microcracking and compromise matrix integrity, leading to reduced compressive strength [84].

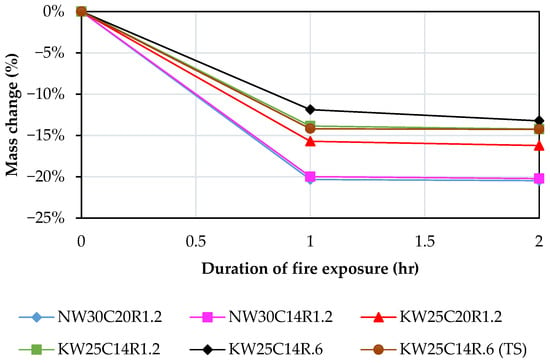

3.3. Mass Loss

Figure 8 presents the mass loss in FA geopolymers after 1 and 2 h of fire exposure, and all geopolymer mixes exhibited mass loss after 1 and 2 h of exposure to elevated temperatures because of evaporation of free and chemically bonded water and decomposition of hydration products [85].

Figure 8.

Mass loss in FA geopolymer after the exposure to 1 and 2 h of fire exposure.

Irrespective of the activator type, all geopolymer mixes exhibited a sharp decrease in mass ranging from 11 to 20% during the first hour of thermal exposure. This sharp decrease occurs as a result of evaporation of both free water and portion of the chemically bound water during the first hour of heating which results in voids, reduces the density of the formation and consequently compromises the mechanical strength [45,66]. This reduction in mass is predominantly influenced by the speed of moisture escape which controls both moisture migration dynamics and vapor pressure accumulation, and consequently the extent of thermochemical and thermomechanical degradation. The rate of moisture escape is positively correlated with heating rate; therefore, under rapid heating, the accelerated temperature rise promotes quick release of chemically and physically bound water compared with slower heating regimes, leading to higher thermal degradation [86]. The ISO 834 standard fire curve demonstrates that water vaporisation plateaus the temperature rise initially, during which moisture dissociates from the paste matrix and creates internal voids and stress concentrations that further exacerbate mechanical degradation [87]. The slight decrease in mass during the second hour could be attributed to the crystallisation which takes place post dehydration of geopolymer gel [85].

It is noted that for all potassium-based mixes, the mass loss was lower than its counterpart sodium-based mixes. Similar results have been reported from previous studies [2,34]. Although it is plausible that the higher W/B ratio in sodium-based mixes is the reason behind the higher mass loss, another study reported a higher mass loss in sodium-based mixes even when potassium-based mixes had a higher W/B ratio [12]. This may be ascribed to the higher thermal resilience of potassium geopolymer gel to combustion than sodium geopolymer gel. Furthermore, it is noted that sodium mixes did not exhibit further mass loss beyond the first hour of firing, whereas potassium mixes, such as KW25C14R6, demonstrated additional mass loss at the second hour. This indicates a delayed onset of network breakdown in the potassium systems. This observation suggests that potassium-activated gels maintain structural integrity at elevated temperatures longer than sodium-activated counterparts, with degradation and softening occurring at a later stage. Similar observations were reported in the literature [7,35].

As shown in Figure 8, in potassium mixes, maintaining total content while increasing the molar ratio of the alkaline activator (Si2O/K2O) from 0.6 to 1.2, a pronounced increase in mass loss is noted. This implicates elevated silica concentration as the primary factor behind the increased mass loss. This observation aligns with Duxson, et al. [30] and Cao, et al. [88] who reported that excessive silica incorporation destabilises the geopolymer gel and increases susceptibility to thermal degradation, resulting in higher mass loss. Duxson, et al. [30] identified a critical threshold at Si/Al > 1.65, whereas our findings suggest a comparable limitation expressed in oxide form, with a silica threshold of Si2O/K2O = 1.2. Beyond these limits, increasing silica content compromises gel stability and exacerbates mass loss at elevated temperatures.

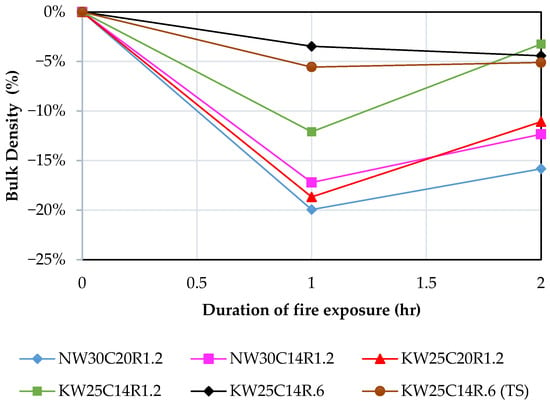

3.4. Density Change

Changes in densities for all mixes post and pre firing at 1 and 2 h are displayed in Figure 9. The changes in density are functions of the changes in mass and volume post firing. All geopolymer mixes displayed a sharp decrease in density during the first hour of firing, at 1 h. Although volumetric changes were observed during the first hour of firing, the severe mass loss resulted from the evaporation of water had the significant influence on the density change. Therefore, the trend depicted a sharp decrease in density, regardless of volume shrinkage which is expected to increase density. During the second hour of firing, changes in density were dictated by changes in volume only as the loss in water is not expected to continue beyond the first hour of firing [45]. It is observed from Figure 9 that potassium-based geopolymers exhibited lower density loss during first hour of firing, with the exception of mix KW25C20R1.2, which significantly expanded during the first hour of firing. The rest of potassium-based geopolymers recorded a higher shrinkage and lower mass loss which resulted in a higher density compared to their counterparts in sodium-based geopolymers.

Figure 9.

Density changes in K-activated and N-activated FA geopolymers at 1 and 2 h of fire exposure.

3.5. Effect of Thermal Shock

Mix KW25C14R.6 (TS) was subjected to thermal shock following a heating regime based on the standard nominal fire curve, applied after 1 and 2 h of firing. Thermal shock was induced by immersing hot specimens in water for 5 min, rather than allowing them to cool naturally.

For both heating periods, the thermal shock impacts, after the densification initiated, exhibited a higher reduction in compressive strength by 10% at 1 h and 13% at 2 h when compared to specimens that were allowed to cool down. This reduction arises from the external surface contracting more rapidly than the core, inducing differential thermal strains within the geopolymer and precipitating microcrack formation. Moreover, the imposed thermal shock might have provoked abrupt phase transformations in the binding gel, resulting in volumetric instabilities [89,90].

Volumetric shrinkage in thermally shocked samples exceeded that of naturally cooled specimens by 0.41% at 1 h, increasing to 0.5% at 2 h. This increase in thermal shock-induced shrinkage with temperature indicates an increased development of higher thermal gradients and associated thermal stresses when the temperature drop is greater.

Furthermore, the increased mass loss during the first and second hours of firing is attributed to microcracking and deterioration of the binding gel, which consequently reduced compressive strength and compromised volumetric stability.

Despite the additional thermal loading from water quenching, surfaces of samples remained intact, and no visible cracks were observed. This is in good agreement with the findings reported in the literature [40,91].

3.6. Compressive Strength—Density Relationship

It is noted that both compressive strength and density of all mixes have remarkably changed after exposure to temperatures following nominal fire curve for 1 and 2 h. Figure 10 displays the relationship between compressive strength and volume change in all tested mixes at all different firing periods. The figure suggests that there is a strong proportional relationship between the change in compressive strength and density such that the reduction in density at first firing hour, predominantly attributed to mass loss, constituted a reduction in compressive strength, whereas the increase in density at second hour of firing, ascribed to reduction in volume, led to an increase in compressive strength. At the first hour of firing, the matrix experiences a significant loss in physically adsorbed water and chemically bound water (dihydroxylation), and this results in internal damage and weakening in the geopolymer framework Si-O-Al, leading to reduced density and compressive strength [14]. At the second hour of firing, the effects of viscous sintering are pronounced where unreacted amorphous content contributes to the densification process, leading to production of geopolymer gel, and subsequently a more compact microstructure and higher compressive strength.

Figure 10.

Relationship between the change in compressive strength and density.

It should be noted from Figure 10 that the general trend with higher silica content exhibited high strength retention after firing at 2 h. Even when lowering total alkali content and while keeping a SiO2/M2O of 1.2, the strength retention behaviour remained. However, when SiO2/M2O molar ratio was lowered to 0.6, the strength retention decreased significantly, and density change was lower than all other mixes while also remaining stable towards the second hour of firing.

Lowering the SiO2/M2O molar ratio increases the concentration of hydroxide ions, which enhances the dissolution of aluminosilicates, leading to a high ambient compressive strength. However, lowering this ratio also reduces the presence of unreacted or partially reacted silica content, which is responsible for producing geopolymer gel during viscous sintering, resulting in densification of the microstructure, and subsequently, a higher compressive strength.

Another factor could be the initial compactness of the microstructure at ambient temperature. It can be derived from Figure 10 that mixes with lower reference strength, such as NW30C14R1.2 or KW30C14R1.2, were able to retain strength at 2 h of 105% and 154%, respectively, whereas mixes with high reference strength, such as KW25C14R0.6, retained only 43% compressive strength. A high ambient compressive strength indicates that a higher degree of dissolution took place and led to a better formation of a geopolymer gel. In this scenario, most of the reactive content has been already consumed; hence at elevated temperatures, the lack of reactive material results in low formation of gel during viscous sintering, subsequently lowering the densification degree.

3.7. Microstructural Characterisation

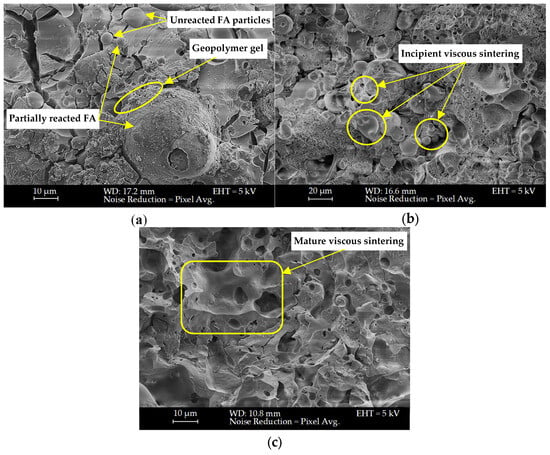

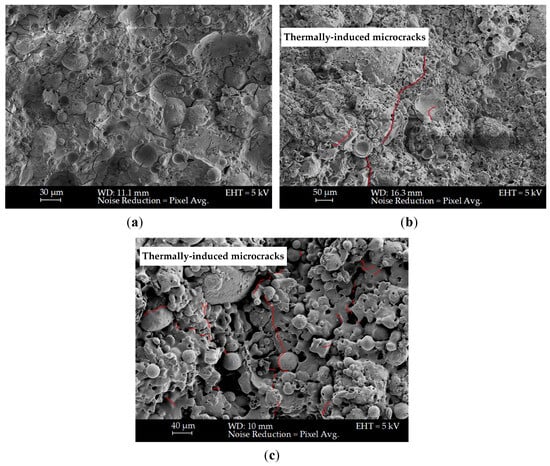

SEM analysis was conducted at room temperature after 1 h 2 h of firing, as shown in Figure 11 and Figure 12 for mixes KW25C20R1.2 and KW25C14R0.6 (TS), respectively.

Figure 11.

SEM captures of KW25C20R1.2 at (a) room temperature, (b) 1 h of firing, and (c) two hours of firing.

Figure 12.

SEM captures of KW25C14R0.6 (TS) at (a) room temperature, (b) 1 h of firing, and (c) two hours of firing, with thermal shock-induced microcracks highlighted in red (b,c).

The fracture surface morphology in Figure 11a displays angular and irregular particles embedded in heterogeneous microstructure, with evidence of unreacted or partially reacted fly ash particles. The surrounding matrix contains several voids and a network of drying shrinkage cracks, which likely formed due to water loss impacting gel formation.

The microstructure in Figure 11b displays early-stage partial neck formation between fly ash/geopolymer particles. Individual particles are still clearly distinguishable with thin material bridges forming at their contact points, indicating the onset of surface diffusion and viscous flow mechanisms. The structure exhibits high porosity characterised by large, interconnected voids which explains the reduction in density and subsequently in compressive strength after 1 h of fire exposure. The increase in porosity can be ascribed to the destructive moisture escape during early heating periods [6,92,93]. Fly ash particles appear partially softened but largely intact. This reflects the initial transition from geopolymer gel to an amorphous, viscous phase undergoing sintering [94,95].

Mature viscous sintering is evident in Figure 11c where formed necks are substantially more advanced, thick, and continuous. Unreacted fly ash particles and porosity are markedly reduced, and distinct particle boundaries have largely disappeared. The smooth surface morphology indicates enhanced viscous flow and progressive transformation of the geopolymer network [26]. This microstructural evolution resulted in a denser, more consolidated matrix that is consistent with the measured increase in shrinkage and compressive strength.

In Figure 12a, unreacted fly ash particles are also present; however, more extensive geopolymer gel binding these particles indicates a higher-degree reaction and matrix development compared to KW25C20R1.2 in Figure 11a. This resulted in more consolidated, dense formation, with less voids and microcracks and enhanced particle bonding. This improvement in microstructure directly correlates with the higher compressive strength in KW25C14R0.6 at room temperature.

In Figure 12b, and similar to mix KW25C20R1.2, the microstructure at 1 h of firing became denser due to the onset of viscous sintering [96]. Viscous flow and associated melting features became more pronounced after 2 h of firing, as evident in Figure 12c.

The SEM observations reveal pronounced microstructural degradation in mix KW25C14R0.6 (TS), exacerbated by the rapid cooling imposed during water quenching when compared to the naturally cooled mix KW25C20R1.2. In Figure 12b, at one hour of thermal exposure, the microstructure exhibits the onset of thermally induced cracking, which becomes more severe after two hours in Figure 12c. These cracks arise from steep thermal gradients generated between the rapidly cooled surface and the hotter interior, producing high transient thermal stresses [97]. Numerous fly ash particles exhibit clear debonding from the geopolymer matrix due to thermal-shrinkage mismatch, with cracks propagating from these particle–gel interfaces that act as local stress-concentration sites. Enlarged pores further amplify these stresses by serving as additional stress risers. The combined cracking, debonding, and pore coalescence indicate that the alkali-activated binder experienced only moderate gelation or incomplete polycondensation, resulting in weak interfacial bonding between the fly ash particles and the surrounding geopolymer gel. This has led to the increased strength degradation noted in KW25C14R0.6 (TS) relative to samples that were allowed to cool naturally.

4. Conclusions

This study presented a comparative thermomechanical assessment of potassium- and sodium-based alkaline activators and various mix design parameters, examining their influence on mechanical properties, densification behaviour, and mass loss following controlled exposure to fire-heating rates. The analysis also interpreted the interrelationships among these properties post-exposure, correlating findings with the suitability of these geopolymers for applications under elevated temperatures. Based on the experimental findings, the following conclusions can be drawn.

- Across all formulations, irrespective of activator type, exposure to the ISO 834 nominal fire curve revealed a progressive viscous sintering mechanism. During the first initial one-hour heating phase, scanning electron microscopy analysis revealed early-stage melting phenomena and modest consumption of unreacted fly ash particles, indicating incipient sintering activity accompanied by a maximum thermal shrinkage of 9.4%. During the subsequent one-hour heating phase, viscous sintering intensified, resulting in accelerated consumption of unreacted fly ash and enhanced production of additional geopolymer gel. This process facilitated pronounced microstructural densification, manifested by increased thermal shrinkage of 10.7%.

- Potassium-activated geopolymers exhibited approximately 5% lower mass loss compared to their sodium-activated counterparts, which can be attributed to the superior thermal stability and lower mobility of potassium cations. The delayed densification observed in potassium systems resulted in reduced shrinkage during the first hour of firing and the highest retained strength after the second hour (154%). This behaviour is linked to slower geopolymerisation kinetics and the higher melting temperature of potassium. In contrast, sodium-activated mixes demonstrated maximum retained strength at the first hour (145%) and lower shrinkage at the second hour, due to earlier densification and more rapid dehydroxylation.

- The oxide ratio had a greater influence over the total oxide content when reducing the oxide ratio of the activator from 1.2 to 0.6, while maintaining a fixed total alkaline activator content had the greatest impact on compressive strength at ambient temperature, increasing it by 55%. This reduction enhanced both compressive strength and mass stability by promoting improved gel formation and densification, supported by SEM. However, it significantly compromised strength retention at elevated temperatures, likely due to the initially compact microstructure which is more susceptible to thermal degradation. Conversely, increasing the oxide ratio, corresponding to higher silica content, led to a remarkable reduction in thermal shrinkage by approximately 5% (even offsetting to expansion) likely resulting from the swelling of the increased unreacted silica content.

- The rapid heating rates characteristic of ISO 834 fire conditions accelerated moisture release during initial heating to significantly higher rates than those in the literature employing slow heating protocols. This moisture loss resulted in high porosity with large, interconnected voids, reducing density and compressive strength.

- Exposure to thermal shock, induced by rapid water quenching immediately following ISO 834 fire heating, resulted in additional compressive strength reductions of 10% and 13% for potassium-activated fly ash geopolymers at 1 and 2 h of heating exposure, respectively. This thermal shock-induced degradation was accompanied by supplementary volumetric contraction of 0.5% and mass loss of 2%, attributed to differential thermal strains, microstructural microcracking evident in scanning electron microscopy analysis, and likely abrupt phase transformations within the geopolymer binding matrix precipitated by the rapid temperature decline.

While sodium-activated geopolymers exhibit higher ambient strength, making them suitable for high-strength applications where fire resistance is not critical, potassium-activated geopolymers demonstrate delayed densification and superior strength retention under fire exposure. This makes potassium activation preferable for fire-resistance applications, provided the Si/Al ratio is optimised within the range of 4.3–4.72, as the lower ratio of 4.0 in this study resulted in accelerated degradation and compromised strength retention.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, H.S.; experiment and data curation, H.S.; original draft preparation, H.S. and R.K.; review and editing, R.K. and R.A.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FA | Fly Ash |

| AA | Alkaline Activator |

| XRF | X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy |

| XRD | X-ray Diffraction |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| PSA | Particle Size Analysis |

References

- Davidovits, J. Properties of geopolymer cements. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Alkaline Cements and Concretes, Kiev, Ukraine, 11–14 October 1994; pp. 131–149. [Google Scholar]

- Omar, S.; Messan, A.; Prud’homme, E.; Escadeillas, G.; Tsobnang, F. Comparative Study on Geopolymer Binders Based on Two Alkaline Solutions (NaOH and KOH). J. Miner. Mater. Charact. Eng. 2020, 8, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phair, J.W.; Van Deventer, J.S.J. Effect of the silicate activator pH on the microstructural characteristics of waste-based geopolymers. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2002, 66, 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panias, D.; Giannopoulou, I.P.; Perraki, T. Effect of synthesis parameters on the mechanical properties of fly ash-based geopolymers. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2007, 301, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nongnuang, T.; Jitsangiam, P.; Rattanasak, U.; Chindaprasirt, P. Novel electromagnetic induction heat curing process of fly ash geopolymer using waste iron powder as a conductive material. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hager, I.; Sitarz, M.; Mróz, K. Fly-ash based geopolymer mortar for high-temperature application—Effect of slag addition. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 316, 128168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Sanjayan, J.G. Factors influencing softening temperature and hot-strength of geopolymers. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2012, 34, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosan, M.A.; Haque, S.; Shaikh, F. Comparative study of sodium and potassium based fly ash geopolymer at elevated temperatures. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Performance-Based and Life-Cycle Structural Engineering, Brisbane, Australia, 9–11 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sitarz, M.; Castro-Gomes, J.; Hager, I. Strength and Microstructure Characteristics of Blended Fly Ash and Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag Geopolymer Mortars with Na and K Silicate Solution. Materials 2021, 15, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Jiménez, A.; Palomo, A.; Criado, M. Alkali activated fly ash binders. A comparative study between sodium and potassium activators. Mater. Constr. 2006, 56, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, H.; Wu, T.; Jin, T.; Pan, Z.; Zheng, J.; Gao, Y.; Zhuang, W. The opposite effects of sodium and potassium cations on water dynamics. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 1429–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakharev, T. Thermal behaviour of geopolymers prepared using class F fly ash and elevated temperature curing. Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36, 1134–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bignozzi, M.C.; Manzi, S.; Natali, M.E.; Rickard, W.D.A.; van Riessen, A. Room temperature alkali activation of fly ash: The effect of Na2O/SiO2 ratio. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 69, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickard, W.D.A.; Williams, R.; Temuujin, J.; van Riessen, A. Assessing the suitability of three Australian fly ashes as an aluminosilicate source for geopolymers in high temperature applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2011, 528, 3390–3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provis, J.L.; Palomo, A.; Shi, C. Advances in Understanding Alkali-Activated Materials. Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 78, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, Y.-J.; Heah, C.-Y.; Al Bakri Abdullah, M.M.; Lee, Y.-S.; Ong, S.-W.; Ooi, W.-E.; Lim, J.-N.; Tee, H.-W. Effect of Water-to-Binder Ratio on Density, Compressive Strength and Morphology of Fly Ash/Ladle Furnace Slag Blended One-Part Geopolymer. Arch. Metall. Mater. 2024, 69, 1381–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Kayali, O. Effect of initial water content and curing moisture conditions on the development of fly ash-based geopolymers in heat and ambient temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 67, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Aydin, S.; Yardimci, M.Y.; Lesage, K.; de Schutter, G. Influence of water to binder ratio on the rheology and structural Build-up of Alkali-Activated Slag/Fly ash mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 264, 120253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provis, J.L.; van Deventer, J.S.J. Geopolymers: Structure, Processing, Properties and Industrial Applications; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasa, A.S.; Swaminathan, K.; Yaragal, S.C. Effect of Water to Geopolymer Solids Ratio on Properties of Fly Ash and Slag-Based One-Part Geopolymer Binders. Res. Transcr. Mater. 2024, 2, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickard, W.D.A.; Temuujin, J.; van Riessen, A. Thermal analysis of geopolymer pastes synthesised from five fly ashes of variable composition. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2012, 358, 1830–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, L.; Yuan, C.; Wang, Q.; Sarker, P.K.; Shi, X. Deterioration of ambient-cured and heat-cured fly ash geopolymer concrete by high temperature exposure and prediction of its residual compressive strength. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 262, 120924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, Z.; Guo, M.; Riaz, M.H. Thermal performance of MK/FA geopolymers: Unveiling the role of FA, equivalent Na2O and modulus. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, L.; Rickard, W.D.A.; van Riessen, A. Strategies to control the high temperature shrinkage of fly ash based geopolymers. Thermochim. Acta 2014, 580, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, L.; Pan, Z.; Tao, Z.; Van Riessen, A. In Situ Elevated Temperature Testing of Fly Ash Based Geopolymer Composites. Materials 2016, 9, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klima, K.M.; Schollbach, K.; Brouwers, H.J.H.; Yu, Q. Enhancing the thermal performance of Class F fly ash-based geopolymer by sodalite. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 314, 125574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, P.K.; Kelly, S.; Yao, Z. Effect of fire exposure on cracking, spalling and residual strength of fly ash geopolymer concrete. Mater. Des. 2014, 63, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.L.Y.; Sanjayan, J.G.; Sagoe-Crentsil, K. Comparative performance of geopolymers made with metakaolin and fly ash after exposure to elevated temperatures. Cem. Concr. Res. 2007, 37, 1583–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alehyen, S.; Zerzouri, M.; el Alouani, M.; el Achouri, M.; Taibi, M.H. Porosity and fire resistance of fly ash based geopolymer. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2017, 8, 3676–3689. [Google Scholar]

- Duxson, P.; Lukey, G.C.; van Deventer, J.S.J. Thermal evolution of metakaolin geopolymers: Part 1—Physical evolution. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2006, 352, 5541–5555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxson, P.; Lukey, G.C.; van Deventer, J.S.J. The thermal evolution of metakaolin geopolymers: Part 2—Phase stability and structural development. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2007, 353, 2186–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.L.Y.; Sanjayan, J.G.; Sagoe-Crentsil, K. Factors affecting the performance of metakaolin geopolymers exposed to elevated temperatures. J. Mater. Sci. 2008, 43, 824–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, F.U.A.; Hosan, A. Mechanical properties of steel fibre reinforced geopolymer concretes at elevated temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 114, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, F.; Haque, S. Effect of nano silica and fine silica sand on compressive strength of sodium and potassium activators synthesised fly ash geopolymer at elevated temperatures. Fire Mater. 2018, 42, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosan, A.; Haque, S.; Shaikh, F. Compressive behaviour of sodium and potassium activators synthetized fly ash geopolymer at elevated temperatures: A comparative study. J. Build. Eng. 2016, 8, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahoti, M.; Wong, K.K.; Tan, K.H.; Yang, E.-H. Effect of alkali cation type on strength endurance of fly ash geopolymers subject to high temperature exposure. Mater. Des. 2018, 154, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptáček, P.; Křečková, M.; Šoukal, F.; Opravil, T.; Havlica, J.; Brandštetr, J. The kinetics and mechanism of kaolin powder sintering I. The dilatometric CRH study of sinter-crystallization of mullite and cristobalite. Powder Technol. 2012, 232, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Li, J.; Shao, R.; Wu, C. Effect of high temperature and cooling method on compression and fracture properties of geopolymer-based ultra-high performance concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 105, 112433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poloju, K.; Srinivasu, K. Method of Determining Characteristics of Geopolymer Concrete under Elevated Temperatures. NeuroQuantology 2022, 20, 11063–11071. [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg, C. An Investigation of Geopolymers for Use in High Temperature Applications. Master’s Thesis, Michigan Technological University, Houghton, MI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, G.-F.; Bian, S.-H.; Guo, Z.-Q.; Zhao, J.; Peng, X.-L.; Jiang, Y.-C. Effect of thermal shock due to rapid cooling on residual mechanical properties of fiber concrete exposed to high temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2008, 22, 948–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Klima, K.M.; Melzer, S.; Brouwers, H.J.H.; Yu, Q. Uncover the thermal behavior of geopolymer: Insights from in-situ high temperature exposure. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2025, 164, 106282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, W.; Zhang, M. Behaviour of alkali-activated concrete at elevated temperatures: A critical review. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 138, 104961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, P.K.; McBeath, S. Fire endurance of steel reinforced fly ash geopolymer concrete elements. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 90, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulkareem, O.A.; Mustafa Al Bakri, A.M.; Kamarudin, H.; Khairul Nizar, I.; Saif, A.A. Effects of elevated temperatures on the thermal behavior and mechanical performance of fly ash geopolymer paste, mortar and lightweight concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 50, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Y.-S.; Liew, Y.-M.; Heah, C.-Y.; Al Bakri Abdullah, M.M.; Pakawanit, P.; Vizureanu, P.; Khalid, M.S.; Ng, H.-T.; Hang, Y.-J.; Nabiałek, M.; et al. Improvements of Flexural Properties and Thermal Performance in Thin Geopolymer Based on Fly Ash and Ladle Furnace Slag Using Borax Decahydrates. Materials 2022, 15, 4178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, S.; Guo, M.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, Z. Tailoring thermal performance of geopolymer via metakaolin/fly ash ratio and activator variation. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 103, 111856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashant, G.S.; Amol, P.; Anant, L.; Harshal, G.M. Compressive Strength of Ambient- and Heat-Cured Fly Ash Geopolymer Concrete after High-Temperature Exposure. J. Comput. Anal. Appl. 2024, 33, 743–748. [Google Scholar]

- Lahoti, M.; Wijaya, S.F.; Tan, K.H.; Yang, E.-H. Tailoring sodium-based fly ash geopolymers with variegated thermal performance. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 107, 103507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahoti, M.; Wong, K.K.; Yang, E.-H.; Tan, K.H. Effects of Si/Al molar ratio on strength endurance and volume stability of metakaolin geopolymers subject to elevated temperature. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 5726–5734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Kodur, V.; Wu, B.; Yan, J.; Yuan, Z.S. Effect of temperature on bond characteristics of geopolymer concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 163, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishak, S.; Lee, H.-S.; Singh, J.K.; Ariffin, M.A.M.; Lim, N.H.A.S.; Yang, H.-M. Performance of Fly Ash Geopolymer Concrete Incorporating Bamboo Ash at Elevated Temperature. Materials 2019, 12, 3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topal, Ö.; Karakoç, M.B.; Özcan, A. Effects of elevated temperatures on the properties of ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS) based geopolymer concretes containing recycled concrete aggregate. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2022, 26, 4847–4862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derinpinar, A.N.; Karakoç, M.B.; Özcan, A. Performance of glass powder substituted slag based geopolymer concretes under high temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 331, 127318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Xu, J.; Bai, E. Strength and Ultrasonic Characteristics of Alkali-Activated Fly Ash-Slag Geopolymer Concrete after Exposure to Elevated Temperatures. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2016, 28, 04015124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez-Molina, D.; Mejía-Arcila, J.M.; de Gutiérrez, R.M. Mechanical and thermal performance of a geopolymeric and hybrid material based on fly ash. DYNA 2016, 83, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C618-12a; Standard Specification for Coal Fly Ash and Raw or Calcined Natural Pozzolan for Use in Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2012.

- Kaplan, G.; Öz, A.; Bayrak, B.; Görkem Alcan, H.; Çelebi, O.; Cüneyt Aydın, A. Effect of quartz powder on mid-strength fly ash geopolymers at short curing time and low curing temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 329, 127153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambikakumari Sanalkumar, K.U.; Lahoti, M.; Yang, E.-H. Investigating the potential reactivity of fly ash for geopolymerization. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 225, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, S.K.; Kumar, S. Role of particle fineness on engineering properties and microstructure of fly ash derived geopolymer. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 233, 117294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, M.; Al-Azzawi, M.; Yu, T. Effects of fly ash characteristics and alkaline activator components on compressive strength of fly ash-based geopolymer mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 175, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provis, J.L.; Yong, C.Z.; Duxson, P.; van Deventer, J.S.J. Correlating mechanical and thermal properties of sodium silicate-fly ash geopolymers. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2009, 336, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carabba, L.; Moricone, R.; Scarponi, G.E.; Tugnoli, A.; Bignozzi, M.C. Alkali activated lightweight mortars for passive fire protection: A preliminary study. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 195, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, W.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Ren, Y. Effects of Si/Al ratio on the efflorescence and properties of fly ash based geopolymer. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaidi, S.; Najm, H.M.; Abed, S.M.; Ahmed, H.U.; Al Dughaishi, H.; Al Lawati, J.; Sabri, M.M.; Alkhatib, F.; Milad, A. Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer Composites: A Review of the Compressive Strength and Microstructure Analysis. Materials 2022, 15, 7098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Wang, D.; Zhao, S.; Duan, P.; Yang, S. Influence of Particle Morphology of Ground Fly Ash on the Fluidity and Strength of Cement Paste. Materials 2021, 14, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, E.D.; Bernal, S.A.; Provis, J.L.; Paya, J.; Monzo, J.M.; Borrachero, M.V. Effect of nanosilica-based activators on the performance of an alkali-activated fly ash binder. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2013, 35, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, H.Y.; Ong, D.E.L.; Sanjayan, J.G.; Nazari, A. The effect of different Na2O and K2O ratios of alkali activator on compressive strength of fly ash based-geopolymer. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 106, 500–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashad, A.M. Influence of different additives on the properties of sodium sulfate activated slag. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 79, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, E.-M.; Cho, Y.-H.; Chon, C.-M.; Lee, D.-G.; Lee, S. Synthesizing and Assessing Fire-Resistant Geopolymer from Rejected Fly Ash. J. Korean Ceram. Soc. 2015, 52, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Park, S.M.; Jang, J.G.; Lee, N.K.; Lee, H.K. Physicochemical properties of binder gel in alkali-activated fly ash/slag exposed to high temperatures. Cem. Concr. Res. 2016, 89, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C109; Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Hydraulic Cement Mortars. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2008.

- ISO 834-1:2025; Fire-Resistance Tests—Elements of Building Construction—Part 1: General Requirements. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2025.

- Rashad, A.M.; Zeedan, S.R. The effect of activator concentration on the residual strength of alkali-activated fly ash pastes subjected to thermal load. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 3098–3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.W.; Chiu, J.P. Fire-resistant geopolymer produced by granulated blast furnace slag. Miner. Eng. 2003, 16, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardjito, D.; Tsen, M. Strength and Thermal Stability of Fly Ash Based Geopolymer Mortar. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference-ACF/VCA 2008, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 11–12 November 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Duxson, P.; Provis, J.; Lukey, G.; Mallicoat, S.; Kriven, W.; Van Deventer, J. Understanding the Relationship Between Geopolymer Composition Microstructure and Mechanical Properties. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2005, 269, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxson, P.; Mallicoat, S.W.; Lukey, G.C.; Kriven, W.M.; van Deventer, J.S.J. The effect of alkali and Si/Al ratio on the development of mechanical properties of metakaolin-based geopolymers. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2007, 292, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Van Deventer, J.S.J. The geopolymerisation of alumino-silicate minerals. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2000, 59, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-Y.; Chen, T.-A. Effects of Composition Type and Activator on Fly Ash-Based Alkali Activated Materials. Polymers 2022, 14, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.T.; Kwon, H.M. Influence of Activator Na2O Concentration on Residual Strengths of Alkali-Activated Slag Mortar upon Exposure to Elevated Temperatures. Materials 2018, 11, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bocullo, V.; Vitola, L.; Vaiciukyniene, D.; Kantautas, A.; Bajare, D. The influence of the SiO2/Na2O ratio on the low calcium alkali activated binder based on fly ash. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2021, 258, 123846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leko, V.K.; Mazurin, O.V. Analysis of Regularities in Composition Dependence of the Viscosity for Glass-Forming Oxide Melts: II. Viscosity of Ternary Alkali Aluminosilicate Melts. Glass Phys. Chem. 2003, 29, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Li, S.H.; Klima, K.M.; Brouwers, H.J.H.; Yu, Q. Degradation mechanism of hybrid fly ash/slag based geopolymers exposed to elevated temperatures. Cem. Concr. Res. 2022, 151, 106649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovnaník, P.; Bayer, P.; Rovnaníková, P. Characterization of alkali activated slag paste after exposure to high temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 47, 1479–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, E.; Kim, G.; Choe, G.; Yoon, M.; Son, M.; Suh, D.; Eu, H.; Nam, J. Explosive Spalling Behavior of Single-Sided Heated Concrete According to Compressive Strength and Heating Rate. Materials 2021, 14, 6023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, B.; Gil, A.; Bolina, F.; Tutikian, B. Thermal damage evaluation of full scale concrete columns exposed to high temperatures using scanning electron microscopy and X-ray diffraction. DYNA 2018, 85, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Li, Y.; Li, P. Synergistic Effect of Blended Precursors and Silica Fume on Strength and High Temperature Resistance of Geopolymer. Materials 2024, 17, 2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolov, A.; Karamanov, A. Thermal Properties of Geopolymer Based on Fayalite Waste from Copper Production and Metakaolin. Materials 2022, 15, 2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallikarjuna Rao, G.; Gunneswara Rao, T.D.; Siva Nagi Reddy, M.; Rama Seshu, D. A Study on the Strength and Performance of Geopolymer Concrete Subjected to Elevated Temperatures. In Recent Advances in Structural Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 869–889. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, S.; Amritphale, S.; Matthews, J.; Paul, N.; Matthews, E.; Edwards, R. Advanced Solid Geopolymer Formulations for Refractory Applications. Materials 2024, 17, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Bakri Abdullah, M.M.; Jamaludin, L.; Hussin, K.; Bnhussain, M.; Ghazali, C.M.R.; Ahmad, M.I. Fly ash porous material using geopolymerization process for high temperature exposure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 4388–4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutaoukil, G.; Alehyen, S.; Sobrados, I.; el Mahdi Safhi, A. Effects of Elevated Temperature and Activation Solution Content on Microstructural and Mechanical Properties of Fly Ash-based Geopolymer. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2023, 27, 2372–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, N.H.; Al Bakri Abdullah, M.M.; Che Pa, F.; Mohamad, H.; Ibrahim, W.M.A.W.; Chaiprapa, J. Influences of SiO2, Al2O3, CaO and MgO in phase transformation of sintered kaolin-ground granulated blast furnace slag geopolymer. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 14922–14932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkifli, N.N.I.; Al Bakri Abdullah, M.M.; Przybył, A.; Pietrusiewicz, P.; Salleh, M.; Aziz, I.H.; Kwiatkowski, D.; Gacek, M.; Gucwa, M.; Chaiprapa, J. Influence of Sintering Temperature of Kaolin, Slag, and Fly Ash Geopolymers on the Microstructure, Phase Analysis, and Electrical Conductivity. Materials 2021, 14, 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heah, C.-Y.; Liew, Y.-M.; Al Bakri Abdullah, M.M.; Hussin, K. Thermal Resistance Variations of Fly Ash Geopolymers: Foaming Responses. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Sun, W.; Chan, S.Y.N. Effect of heating and cooling regimes on residual strength and microstructure of normal strength and high-performance concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2000, 30, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.