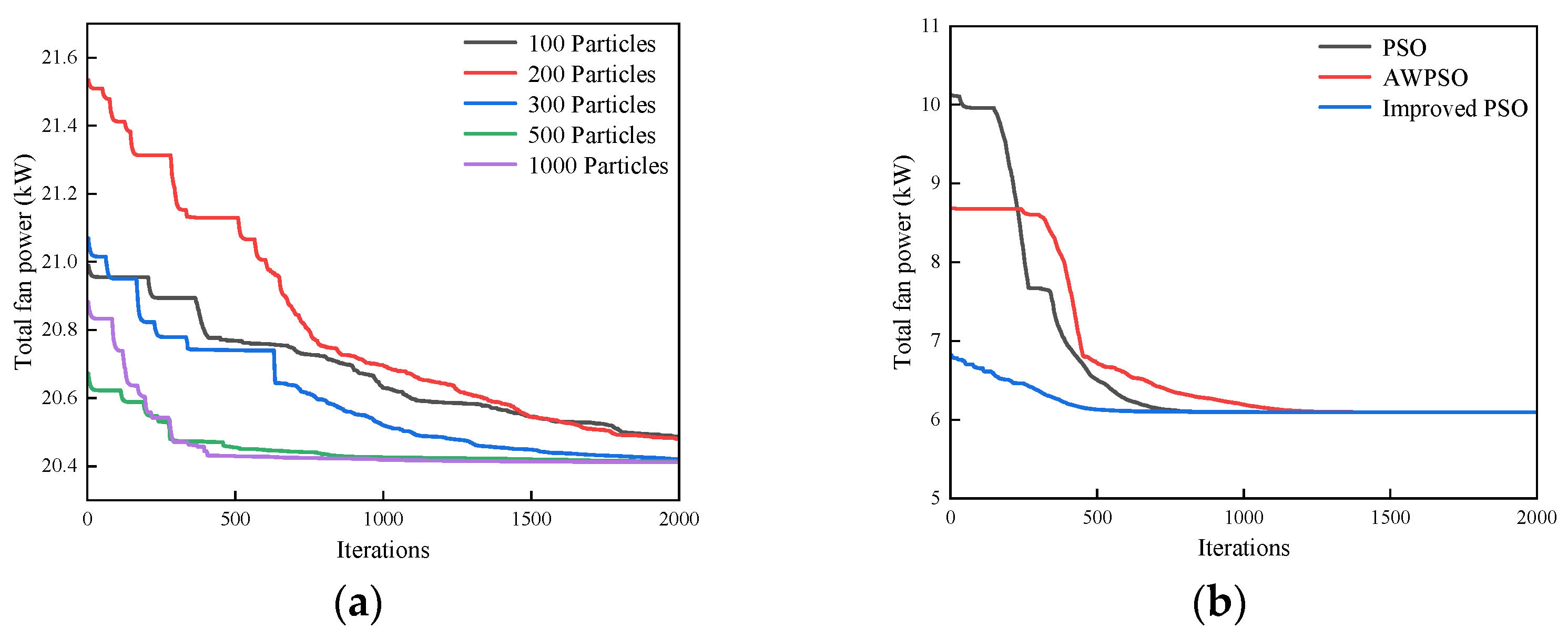

2.1. Tunnel Ventilation Model and CFD Simulation Method

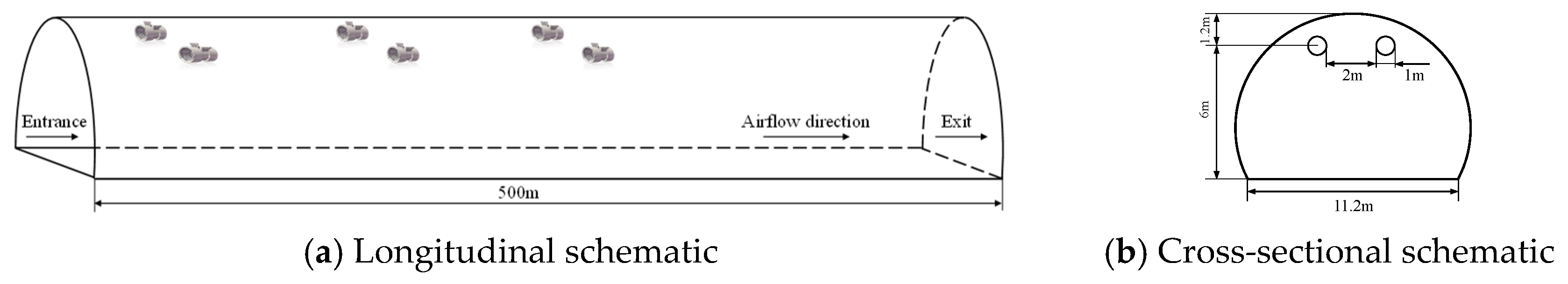

A 500 m-long, two-lane, single-bore highway tunnel is focused on in this work, representing a single ventilation section employing longitudinal mechanical ventilation. The arrangement of these jet fans is shown in

Figure 1a. Three pairs of jet fans are installed on the tunnel crown, located at 15 m, 165 m, and 315 m from the tunnel entrance. The cross-section features a 2 m transverse spacing between fans and an installation height of 6 m, as illustrated in

Figure 1b. The cross-sectional area of the tunnel is 65.4 m

2.

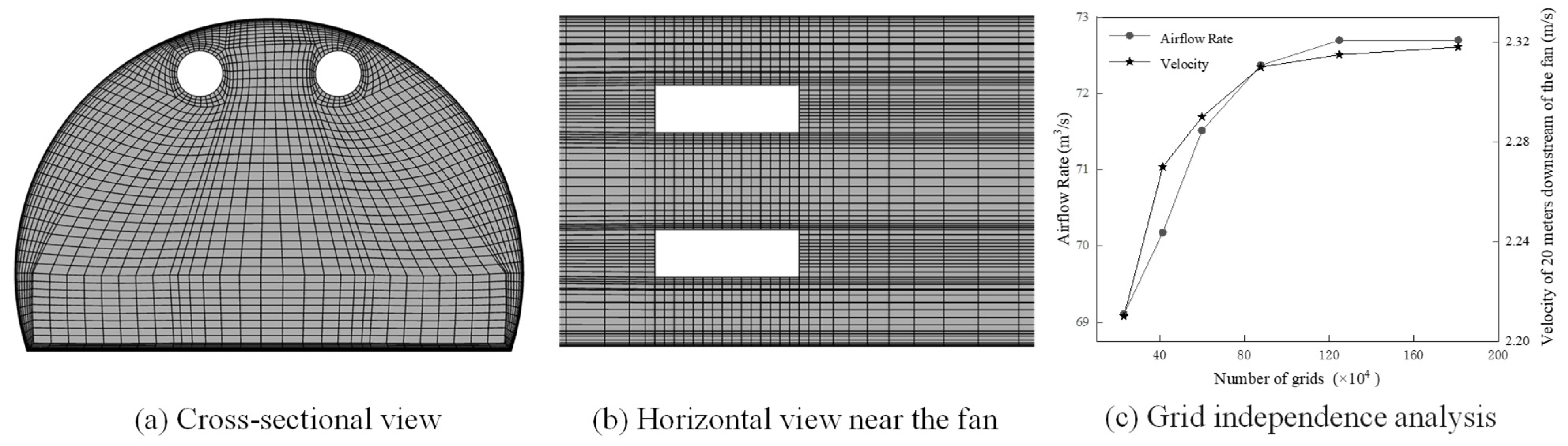

To simulate the airflow field in the tunnel ventilation system, a computational fluid dynamics (CFD) model is established using the ANSYS Fluent 2022 R1. The Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) method is applied in the CFD simulations. Referring to common CFD studies [

22,

42,

43,

44] the standard

k-

ε turbulence model exhibits high robustness and has been fully validated by experiments; it is employed in this work. Six sets of grids for the simulation with the same topology but different densities are selected for the grid independence analysis. The structure of the grid and the calculation results are presented in

Figure 2. It is shown that, when the grid density exceeds that of Grid 4 (the fourth from the left in

Figure 2c), the numerical error of total airflow rate in the tunnel and the velocity at 20 m downstream of the fan caused by the variance of grid density is about 1%, which can meet the precision requirement. Therefore, Grid 4 is selected in the work, and the total grid number is 8.76 × 10

5. Regarding boundary conditions, both the inlet and outlet of the fans are defined as velocity inlets, the inlet and outlet velocities of the fan are equal in magnitude but opposite in direction; the tunnel entrance is set as a pressure inlet; and the tunnel exit is set as a pressure outlet.

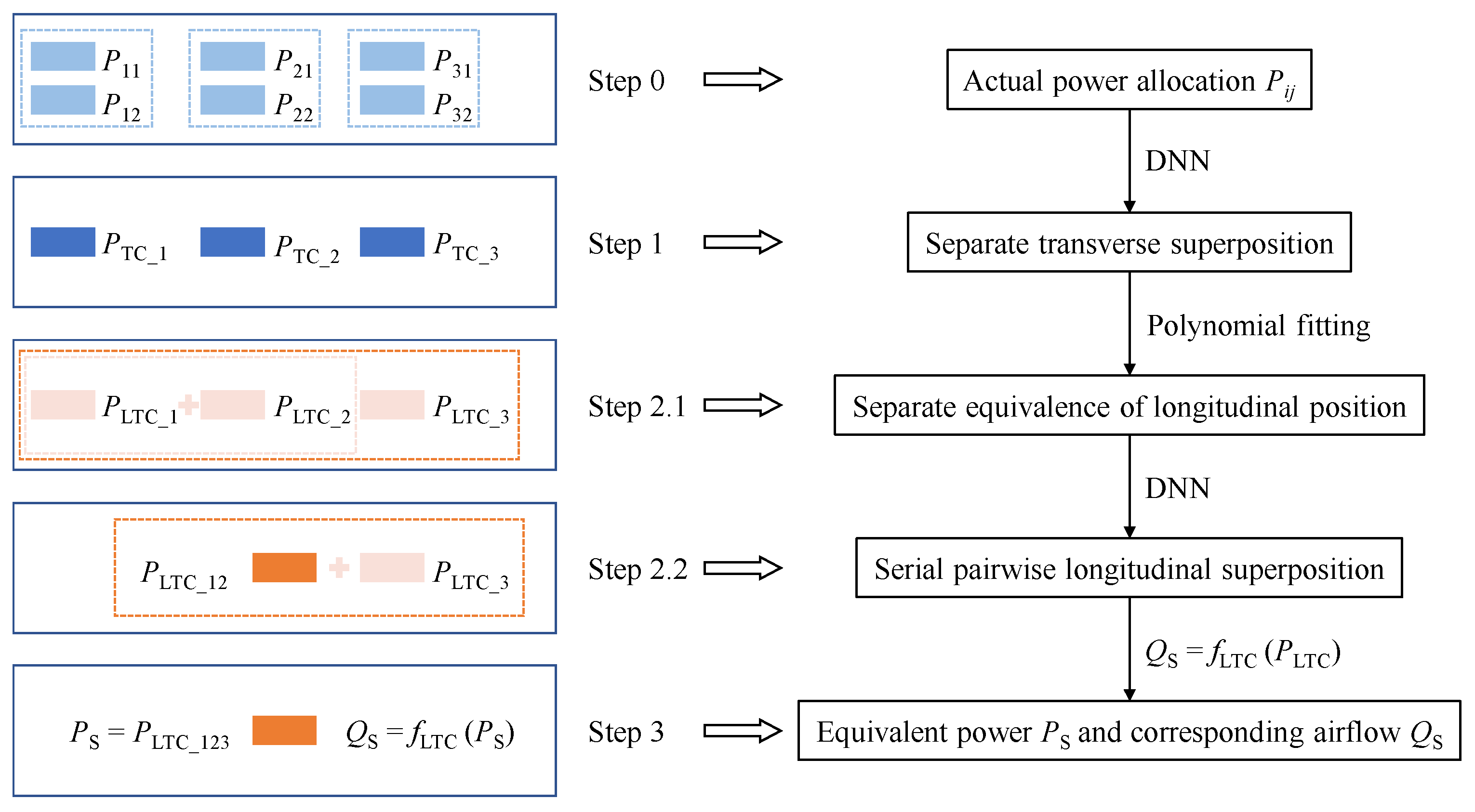

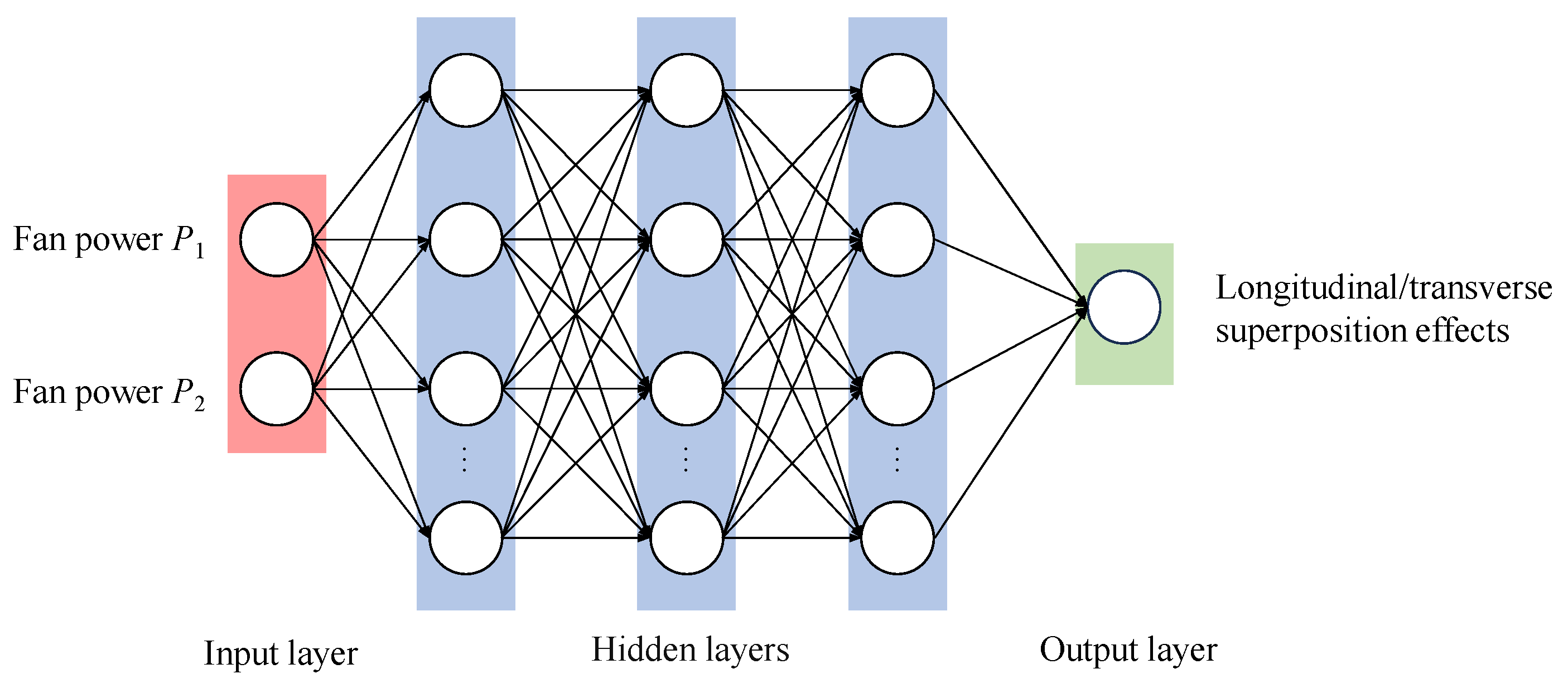

The multi-fan configuration in actual ventilation poses significant challenges for accurately predicting the total airflow rate. To address this, a simplification strategy is proposed, as illustrated in

Figure 3. The nonlinear superposition of the multi-fan ventilation effects is decoupled into longitudinal and transverse components. Through sequential transverse and longitudinal superposition, the equivalent power

PS corresponding to

fLTC with equal ventilation supply

QS is obtained. The equivalent object is a virtual scenario where tunnel ventilation is solely provided by a single fan (denoted

fLTC) centred in both the longitudinal and transverse directions, and its power

PLTC is assumed to be infinitely and continuously adjusted. Through the fitting of CFD results, a one-to-one correspondence is established between

PLTC and the resulting airflow rate

QS, as expressed in Equation (1). Based on this strategy, a simplified predictive model for the total tunnel airflow rate is developed, laying the groundwork for subsequent optimization. The physical basis, training, and usage of this model are as follows.

2.2. Analysis and Quantification of Transverse Synergy

In tunnel ventilation systems, jet fans are typically installed in parallel pairs, symmetrically positioned about the longitudinal axis. However, aerodynamic coupling between fans makes airflow calculations for such layouts computationally intensive. In this study, a transverse synergy-equivalence method is introduced, wherein the combined effect of paired fans is modelled as a single equivalent fan. This equivalent fan retains the original longitudinal position but is placed at the tunnel’s transverse centreline (denoted FTC).

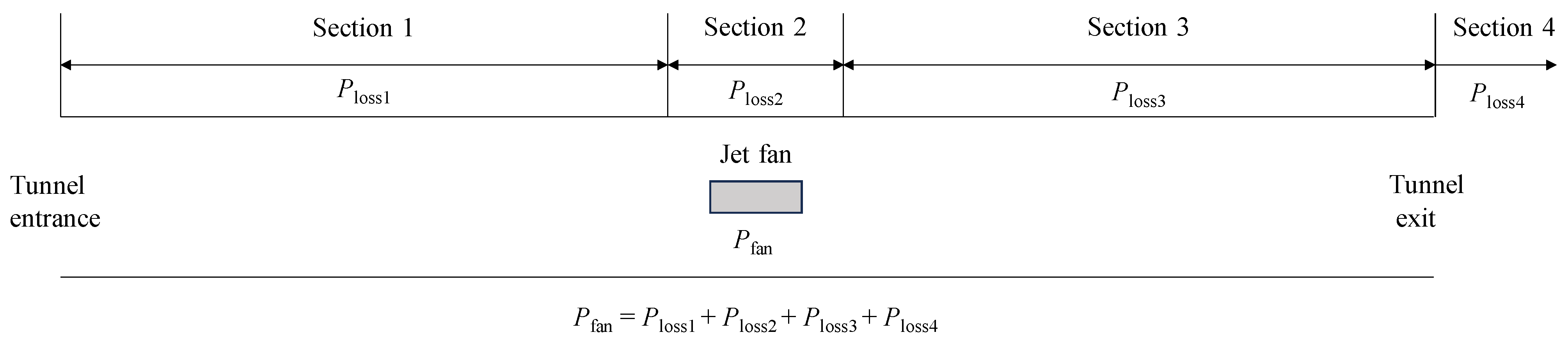

When the same ventilation effect is achieved, parallel fans operating in synergy consume less energy than the equivalent F

TC fan. For detailed analysis, the overall energy loss of tunnel airflow is divided into four segments, and their sum equals the fan power

Pfan according to the energy conservation principle, as shown in

Figure 4. Section 1 covers from the tunnel entrance to 1 m upstream of the fan inlet, with energy loss

Ploss1 and specific loss Δ

Ploss1. Section 2 spans from 1 m upstream of the fan inlet to 1 m downstream of the fan outlet, incurring with loss

Ploss2. Section 3 runs from 1 m downstream of the fan outlet to the tunnel exit, with loss

Ploss3 and specific loss Δ

Ploss3. Section 4 accounts for loss beyond the tunnel exit (

Ploss4).

Table 1 compares fan power and energy losses for each segment under the same tunnel airflow rate (200 m

3/s). The combined power of the parallel fans is 4.62 kW lower than that of a single fan. Sections 1 and 4 show negligible differences, whereas Section 2 contributes 2.04 kW (44.2%) and Section 3 contributes 2.58 kW (56.0%) of the total savings. Consequently, Sections 2 and 3 are identified as the primary focus.

To examine the loss in Section 2 in detail, the local distributions of longitudinal velocity (hereafter referred to simply as velocity) and entropy generation near the fans for single-fan and parallel-fan arrangements are compared in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, respectively. At equal tunnel airflow rates, the single fan produces higher inlet and outlet velocities, steep velocity gradients, and greater frictional loss—resulting in increased energy dissipation. By contrast, the parallel-fan arrangement uses lower power per fan and yields reduced inlet and outlet velocities, producing a more uniform velocity field and lower frictional loss. This difference continues downstream until the tunnel exit. The global distributions of velocity for both arrangements are presented in

Figure 7. It is revealed that in the extended downstream region, the airflow in the parallel-fan case is more evenly distributed, with lower velocity gradients. The reduced shear minimizes frictional energy loss in Section 3. Overall, the parallel-fan arrangement achieves superior aerodynamic synergy, reduces velocity gradients, and consequently cuts total frictional losses and energy consumption.

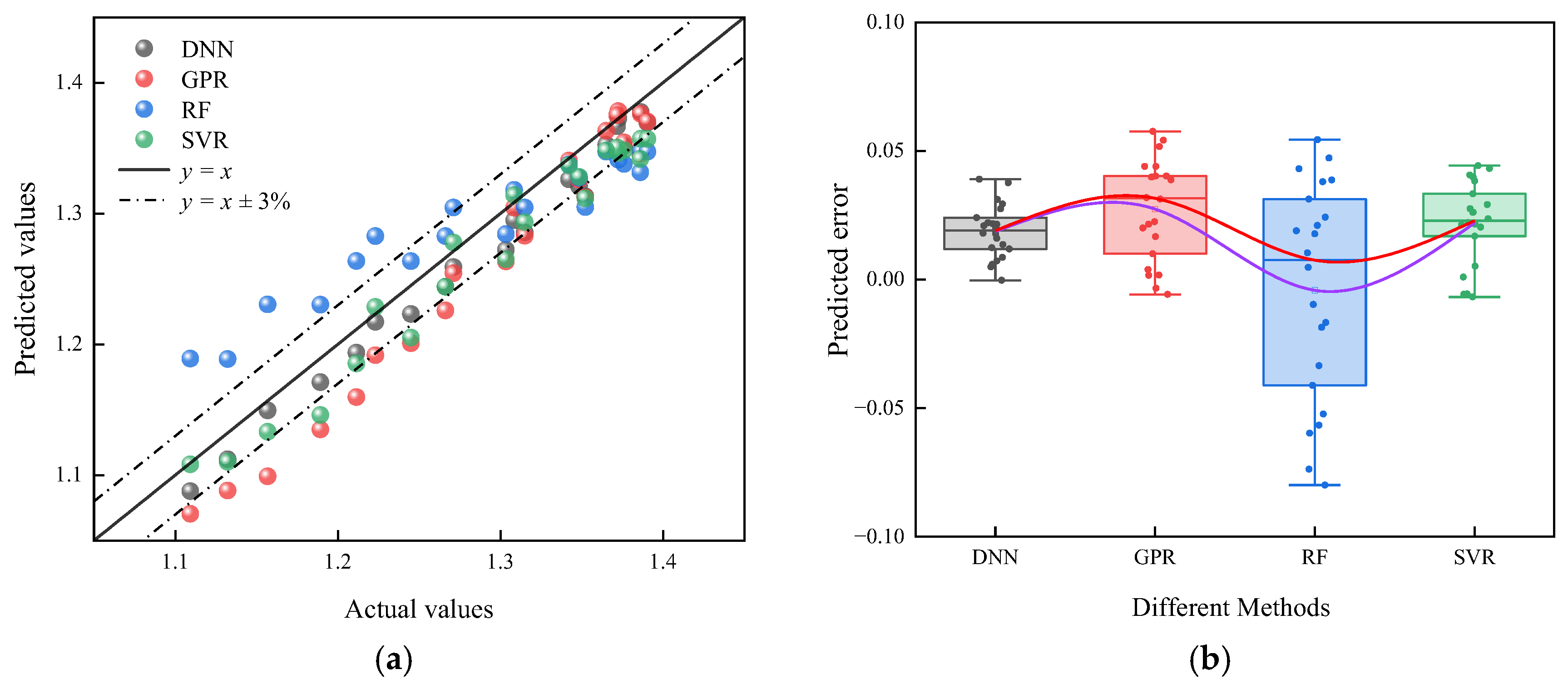

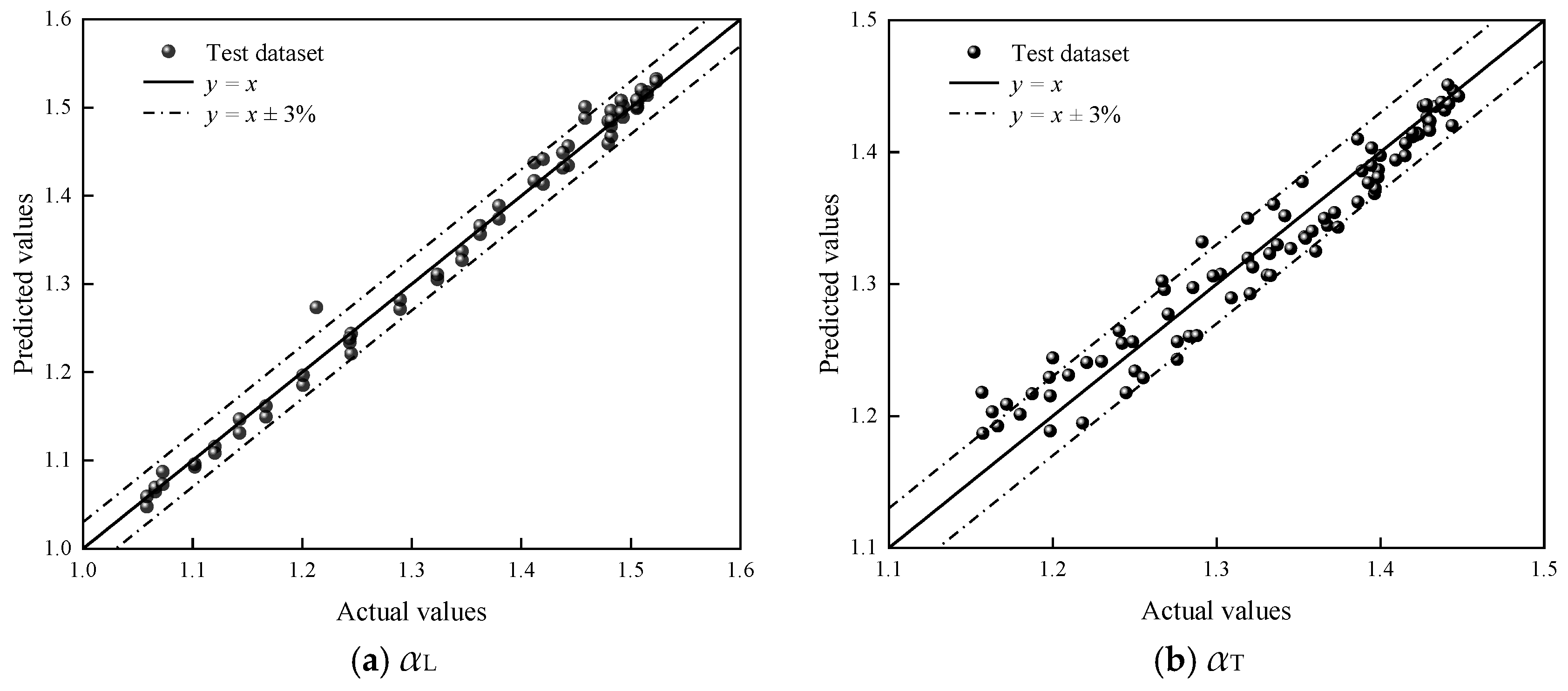

In the transverse equivalence calculation, under identical ventilation conditions, the combined power of two parallel fans is mapped to the power of a single equivalent fan F

TC (Equation (2)). Here,

PTC_i (

i = 1, 2, 3) denotes the equivalent fan power resulting from transverse superposition, while

Pi1 and

Pi2 represent the actual powers of the two parallel fans at the

ith longitudinal station. This nonlinear mapping is modelled using data from multiple representative operating conditions. Equation (1) is subsequently applied to calculate the equivalent ventilation effect. To quantify this synergy, the transverse superposition factor

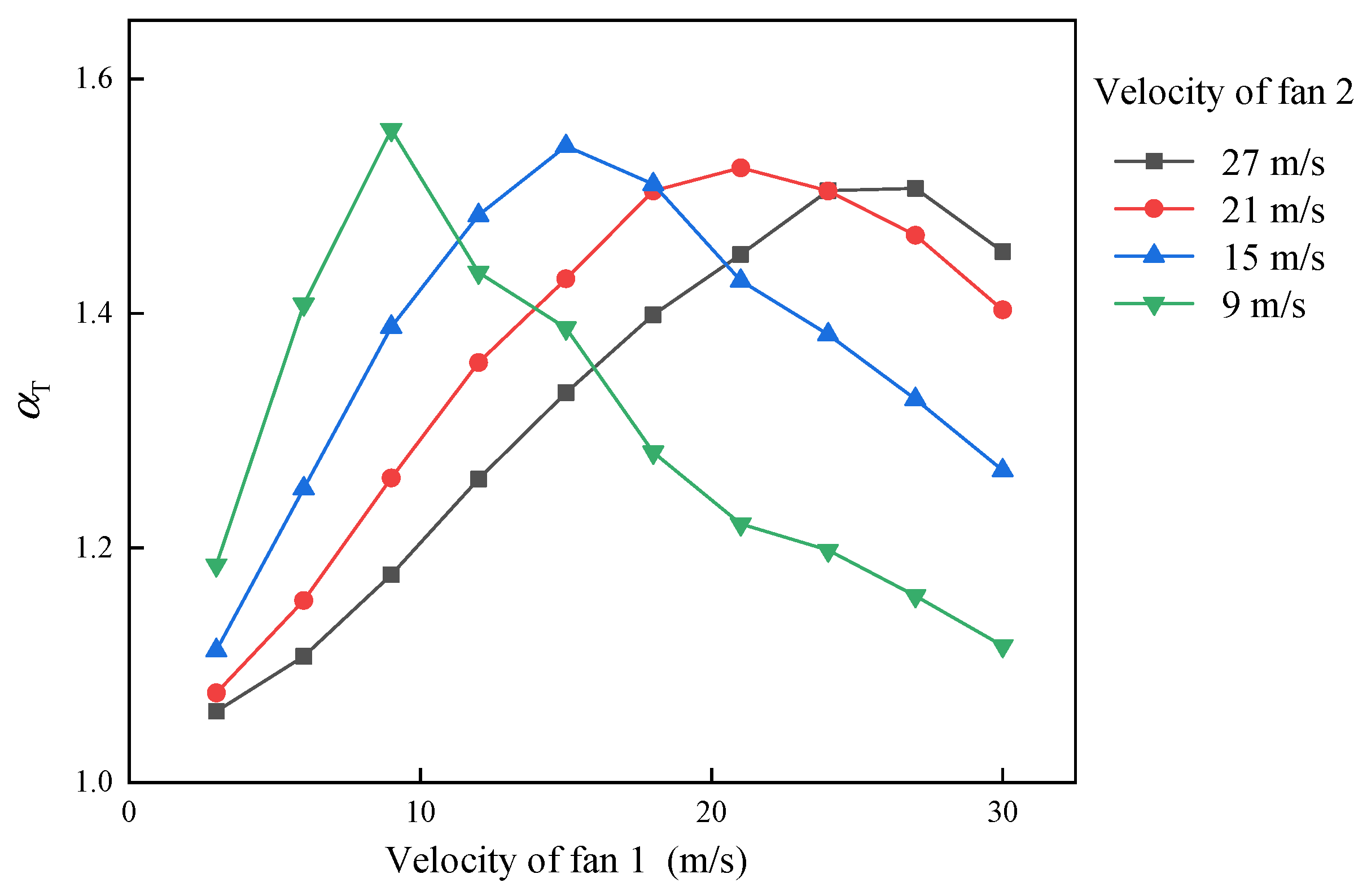

αT is introduced (Equation (3)), defined as the ratio of the equivalent single-fan power to the sum of the two fans’ powers at equal airflow. The relationship between

αT and the outlet-velocity difference is shown in

Figure 8: When velocities match closely, shear is minimal, frictional loss is low, yielding a high

αT; as the velocity gap widens, shear and loss increase, and

αT decreases.

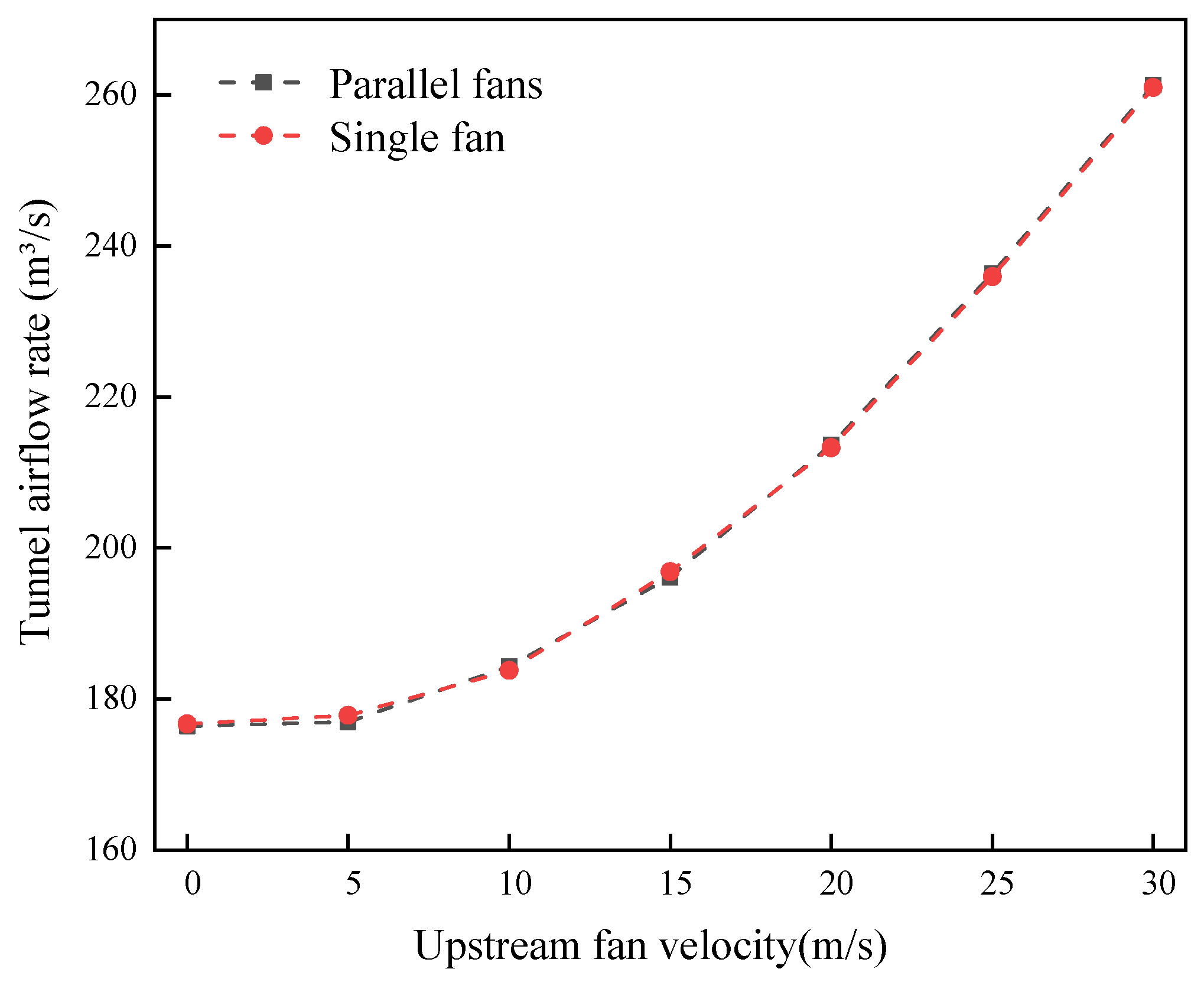

To validate decoupling local transverse superposition from global longitudinal superposition, the influence of transverse superposition on longitudinal effects is first examined, to ensure the applicability of the decoupling effect. It is demonstrated in

Figure 7 that two parallel jets diffuse and merge within a short distance, producing a flow field equivalent to a single fan. As a result, the perceived background flow around downstream fans is consistent with the single-fan conditions. The same applies to the upstream flow field. Thus, under identical ventilation conditions, the local transverse arrangement does not alter the background flow perceived by upstream or downstream fans. That is, the transverse arrangement of fans has no substantial effect on the longitudinal superposition within downstream ventilation systems. Next, the influence of longitudinal superposition on transverse superposition is analyzed. To assess whether upstream jets influence downstream transverse synergy, two scenarios are established: identical downstream ventilation is provided either by a single fan or parallel fans. An upstream fan is introduced with adjustable outlet velocity. As shown in

Figure 9, the total tunnel airflow remains unchanged across a range of background velocities, confirming that the transverse superposition effect is invariant with respect to longitudinal flow variations. In summary, when enough longitudinal spacing exists between fan groups, longitudinal and transverse superposition operate independently, allowing us to decouple them and simplify the multi-fan ventilation model.

2.3. Analysis and Quantification of Longitudinal Synergy

- (1)

Influence of longitudinal positions

Although the downstream diffusion of fan jets is fundamentally similar across longitudinal positions, ventilation performance varies with distance from the tunnel entrance. It is therefore necessary to compare the ventilation performance of fans at different longitudinal positions after applying the equivalent treatment of transverse synergistic effects described in the previous subsection. Fan powers and sectional energy losses of the fans located at 15 m, 165 m, and 315 m (Cases 15, 165, and 315) under the same tunnel airflow rate (200 m

3/s) are compared in

Table 2. The power difference between Cases 15 and 315 is 1.61 kW. Section 1 shows only minor variation in specific loss. Section 2 contributes a loss differential of 0.71 kW (44% of the overall difference), and Section 3 also exhibits a notable disparity. Section 4 adds 0.25 kW (15.6%). Accordingly, the losses in Sections 2 and 4 are first targeted, with the specific loss discrepancy in Section 3 examined next.

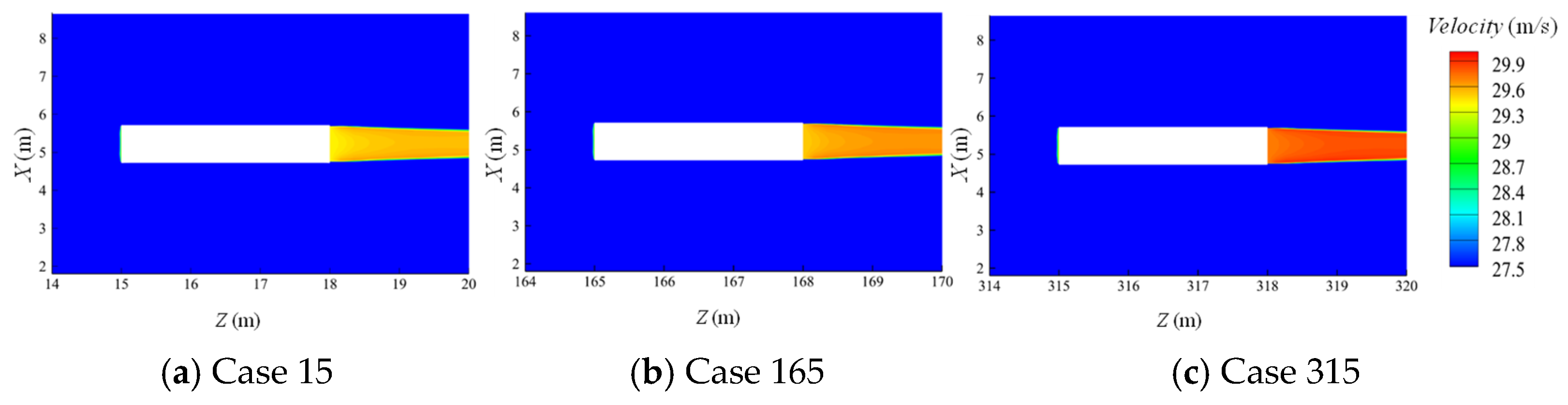

Regarding the energy loss in Section 4, velocity distributions at the tunnel exit for fans at three longitudinal positions are displayed in

Figure 10. Compared to the fan outlet, the velocity distribution at the tunnel exit is essentially uniform after long-distance mixing. However, this quantitative difference still results in a significant energy difference. In Case 315, due to relatively insufficient mixing, the larger velocity differences lead to greater total kinetic energy, increasing external dissipation. In comparison, as the mixing distance increases, the total kinetic energy in Case 165 and Case 15 decreases. The elevated residual kinetic energy (energy dissipation after exiting the tunnel) in Case 315 forces the upstream fan to inject more power, reflected in higher inlet and outlet velocities and highlighting notable local flow loss differences.

Local distributions of velocity are then compared in

Figure 11. In Case 315, the higher inlet and outlet velocities create steep velocity gradients and increased frictional loss, especially in high-shear zones near the fan. This raises local energy dissipation. By contrast, Cases 15 and 165 maintain gentler velocity gradients and lower frictional loss. This disparity in velocity gradients persists downstream from the fan outlets to the tunnel exit, driving proportionally larger specific loss in Section 3. On the other hand, at a tunnel flow rate of 200 m

3/s, the average velocity is about 3 m/s. Thus, the flow is considered uniform when the maximum cross-sectional velocity reaches 5 m/s. This occurs at 97 m, 100 m, and 101 m downstream of the fan for case15, case165, and case315, respectively. Case315 has the longest diffusion distance and the highest energy loss, while case15 has the shortest and lowest energy loss.

Fan power differentials across longitudinal arrangement positions, under identical ventilation conditions, are quantified. Equation (4) is applied to calculate the equivalent power

PLTC_i of

fLTC corresponding to the actual power at the

ith longitudinal position, and the relative ratio is defined as the longitudinal position coefficient

lp (Equation (5)). It is found that the relative ratio of power among the three positions remains essentially unchanged across a range of airflow rates. Based on this near-invariance, polynomial regression is applied to fit

lp as a function of fan power over the operational range at a given longitudinal position. The prediction of

lp is much easier than that of transverse and longitudinal superposition effects, which can also be approximated by interpolation according to the longitudinal position. Therefore, by equivalently treating the effect of different longitudinal positions in advance, there is no need to consider this effect in the subsequent longitudinal superimposition, further simplifying the prediction process.

- (2)

Longitudinal superposition

Under identical ventilation requirements, lower energy consumption is observed for serially configured fans compared to single-fan systems. A synergistic equivalence method is proposed to quantify longitudinal synergistic effects. For the same ventilation airflow supply (200 m3/s), a single fan installed in the longitudinal centre and a series of fans installed at 15 m and 165 m, respectively, are used for comparison. It is found that 3.59 kW more power is required by the single-fan configuration than by the serial-fan one, of which 1.86 kW is attributed to increased longitudinal distributed losses (51.8% of the total difference) and 1.75 kW to increased local losses (48.8%) near the fans.

Energy loss is analyzed based on local distributions of velocity for the single-fan and serial-fan arrangements (

Figure 12), respectively. The single-fan configuration exhibits significantly higher inlet and outlet velocities, resulting in larger velocity gradients and frictional losses that elevate overall energy dissipation. By contrast, in the serial-fan case, the upstream-generated jet is fully mixed before encountering the downstream fan, establishing a nearly uniform background flow field. At this time, the downstream fan generates a weaker jet. Consequently, the velocity difference between the fan inlet/outlet and the surrounding airflow is significantly reduced, and total frictional loss is markedly lowered. The global distributions of velocity in

Figure 13 further illustrate that the reduced velocity differentials are maintained over a long downstream distance, decreasing the frictional loss. A similar influence is observed for the downstream fan on the upstream unit. In summary, by providing a uniform background flow, the two fans in series minimize local velocity gradients and frictional loss, thereby reducing overall energy consumption.

Based on the above analysis, the ventilation effect resulting from longitudinal superposition is solely determined by the equivalent ventilation powers

PLTC of the upstream and downstream fans (rows), and is independent of their specific allocations. This demonstrates that upstream longitudinal superposition does not influence subsequent downstream superposition. Consequently, through successive pairwise superpositions, multiple fans can ultimately be represented by a single equivalent fan

fLTC situated at the longitudinal and transverse midpoint, thereby quantifying the coupling effect among multiple fans (rows). An illustrative example for three fans in series is given in Equation (6), in which the subscript L2 denotes longitudinal pairwise superposition.

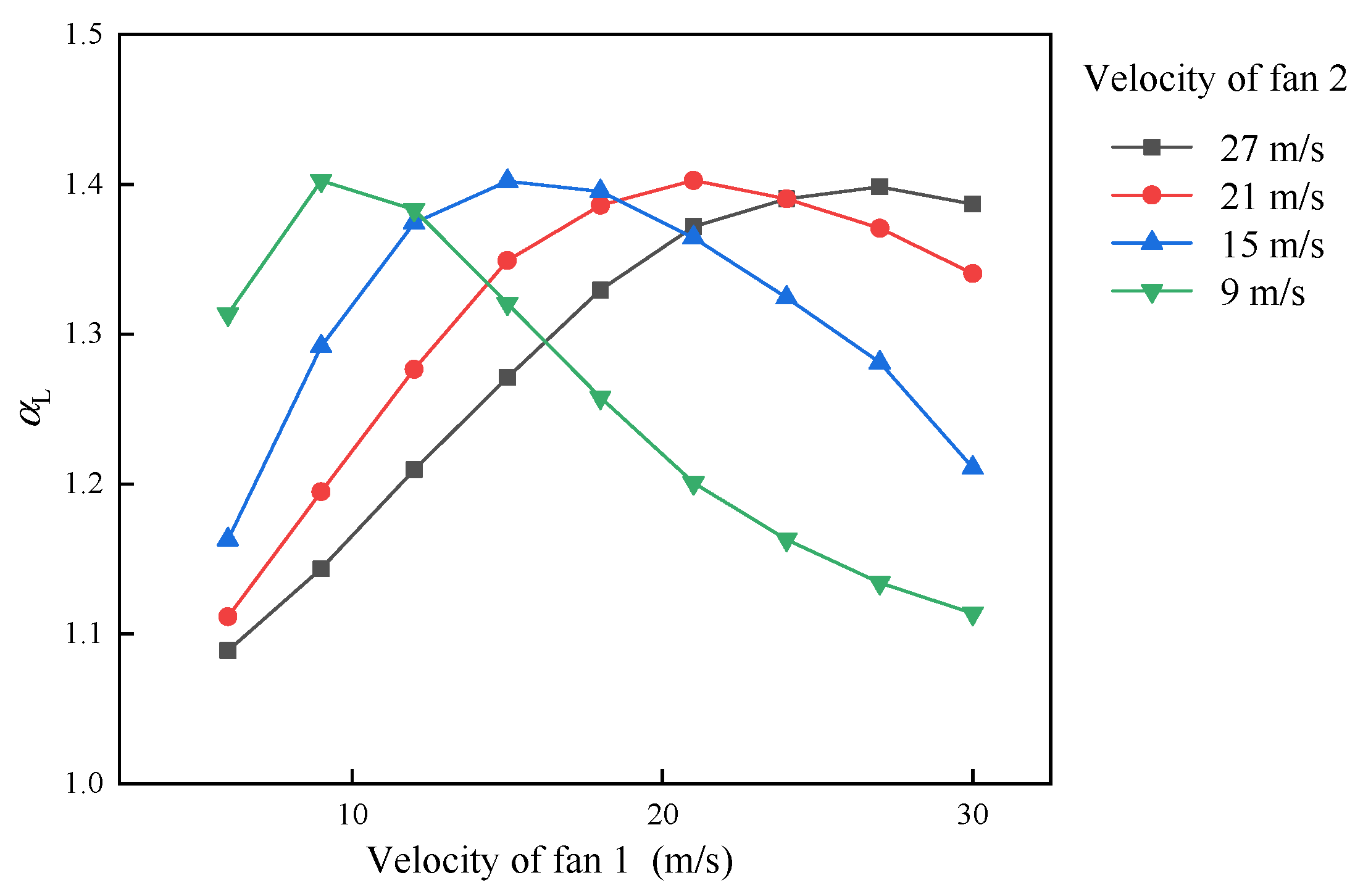

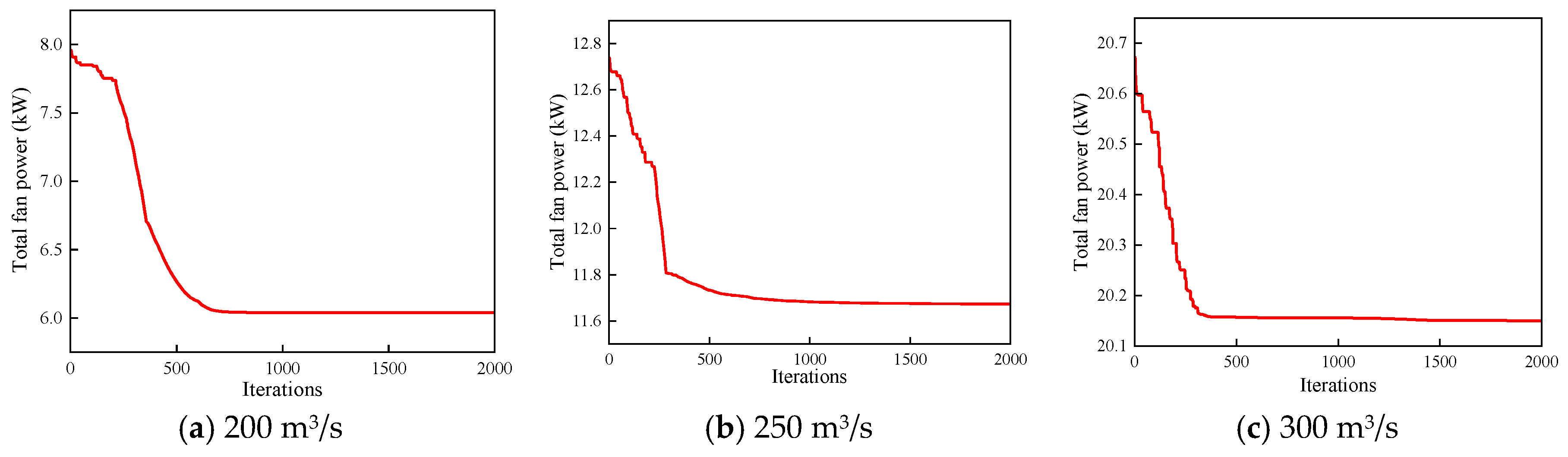

To quantify the synergistic effect of serial-fan operation, the longitudinal superposition factor

αL is defined as the ratio of the power of an equivalent single fan to the total power of all serially arranged fans achieving the same airflow rate. An example of two serial fans is shown in Equation (7). The relationship between

αL and the outlet velocity of each fan is presented in

Figure 14. When the outlet velocities are close, the velocity gradients in the surrounding flow field decrease, and the shear effect in the flow is weakened, resulting in an enhanced synergy (larger

αL). In contrast, when the velocity difference is large, the airflow becomes less uniform, leading to stronger friction and a reduced synergy.