A Comprehensive Review on Dual-Pathway Utilization of Coal Gangue Concrete: Aggregate Substitution, Cementitious Activity Activation, and Performance Optimization

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Global Inventory Scale and Environmental Load of Coal Gangue

1.2. Dual Value of Coal Gangue in Carbon Neutrality: Environmental Benefits and Low-Carbon Building Materials

1.3. Core Contradiction: Conflict Between Scalable Mitigation and High-Performance Concrete Requirements

1.4. Review Objective: Performance, Optimization, and Application Boundaries of Coal Gangue (Aggregates/Admixtures)

2. Intrinsic Properties of Coal Gangue Materials and Their Restrictive Mechanisms on Concrete Performance

2.1. Composition Variability: Effects of SiO2–Al2O3 Main Phases and Carbon/Sulfur/Heavy Metal Impurities

2.2. Mineral-Phase Nature: Kaolinite—Potential for Transformation to Halloysite and the Activation Threshold

2.3. Physical Drawbacks: Porosity, Water Absorption, and Strength

2.4. Logical Mapping from Raw Material Defects to Concrete Performance Degradation

3. Path 1: Performance Degradation Mechanism and Multiscale Enhancement Strategy with Coal Gangue as the Aggregate

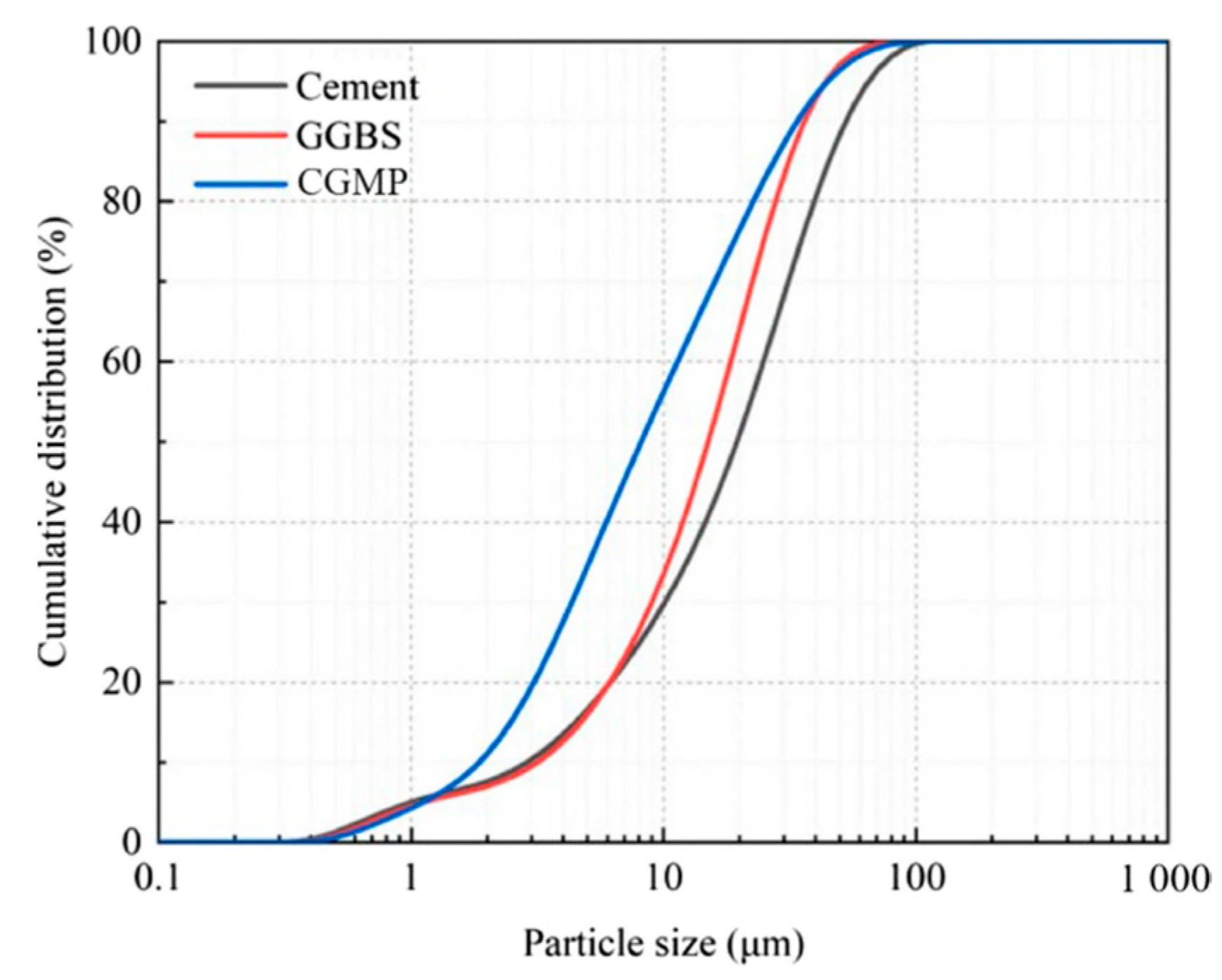

3.1. Performance Impact Law

3.1.1. Coarse Aggregate: Strength Monotonically Decreases with a “Strong Matrix–Weak Aggregate” System

3.1.2. Fine Aggregate: At Low Substitution Levels, the Microfilling Effect and Secondary Hydration Contribute to Strength Enhancement

3.1.3. Fresh Property Degradation: High Water Absorption Leads to Slump Loss

3.2. Durability Nonlinear Response

3.2.1. Significant Deterioration in Frost Resistance: Pore Water Freezing Expansion Drives the Propagation of Microcracks

3.2.2. Carbonation Acceleration: Permeable Pores Facilitate CO2 Penetration

3.2.3. The “Anomalous Advantage” of Chloride Ion Penetration: A Dual Physical-Chemical Barrier Mechanism of Dense ITZ

3.3. Performance Enhancement Technology System

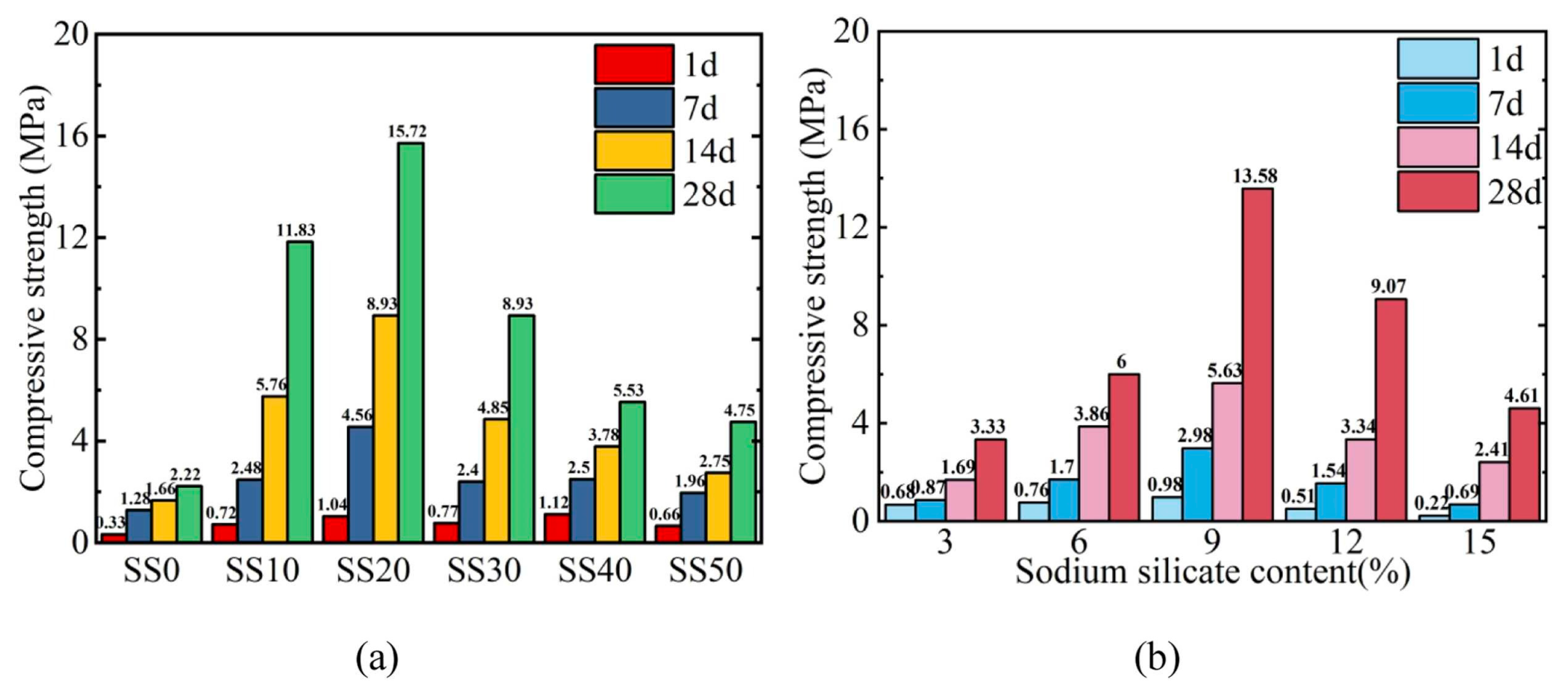

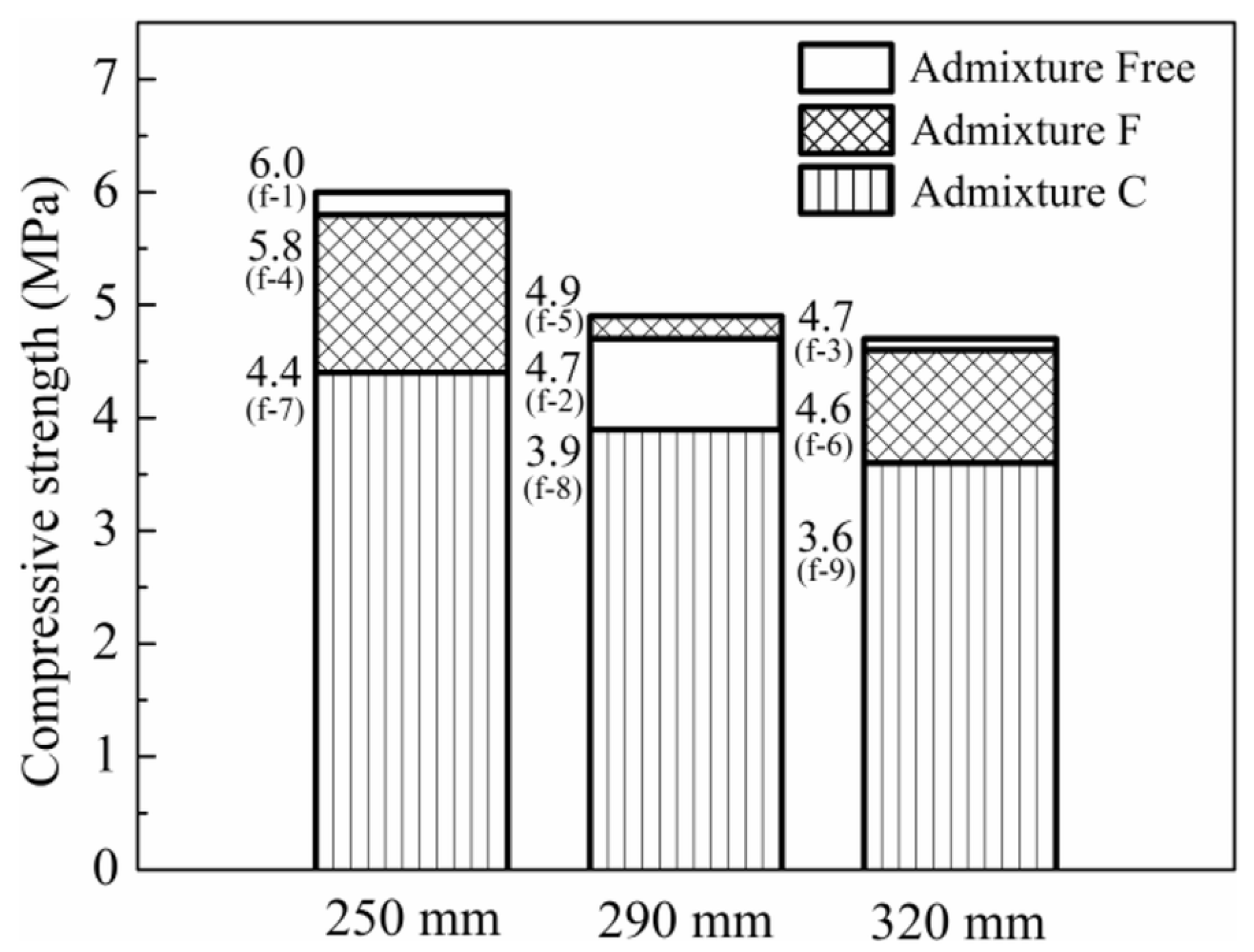

3.3.1. Aggregate Body Modification: Pre-Wetting (Internal Curing), Calcination (Surface Activation), and Sodium Silicate Coating (Pore Sealing)

3.3.2. Biomineralization (MICP): CaCO3 Precipitation Fills Pores and Immobilizes Heavy Metals

3.3.3. Matrix Synergistic Reinforcement: SCM Densification + Fiber Toughening System Compensation Strategy

4. Path 2: Activation Mechanism of Coal Gangue as a Mineral Additive and Its Performance Enhancement

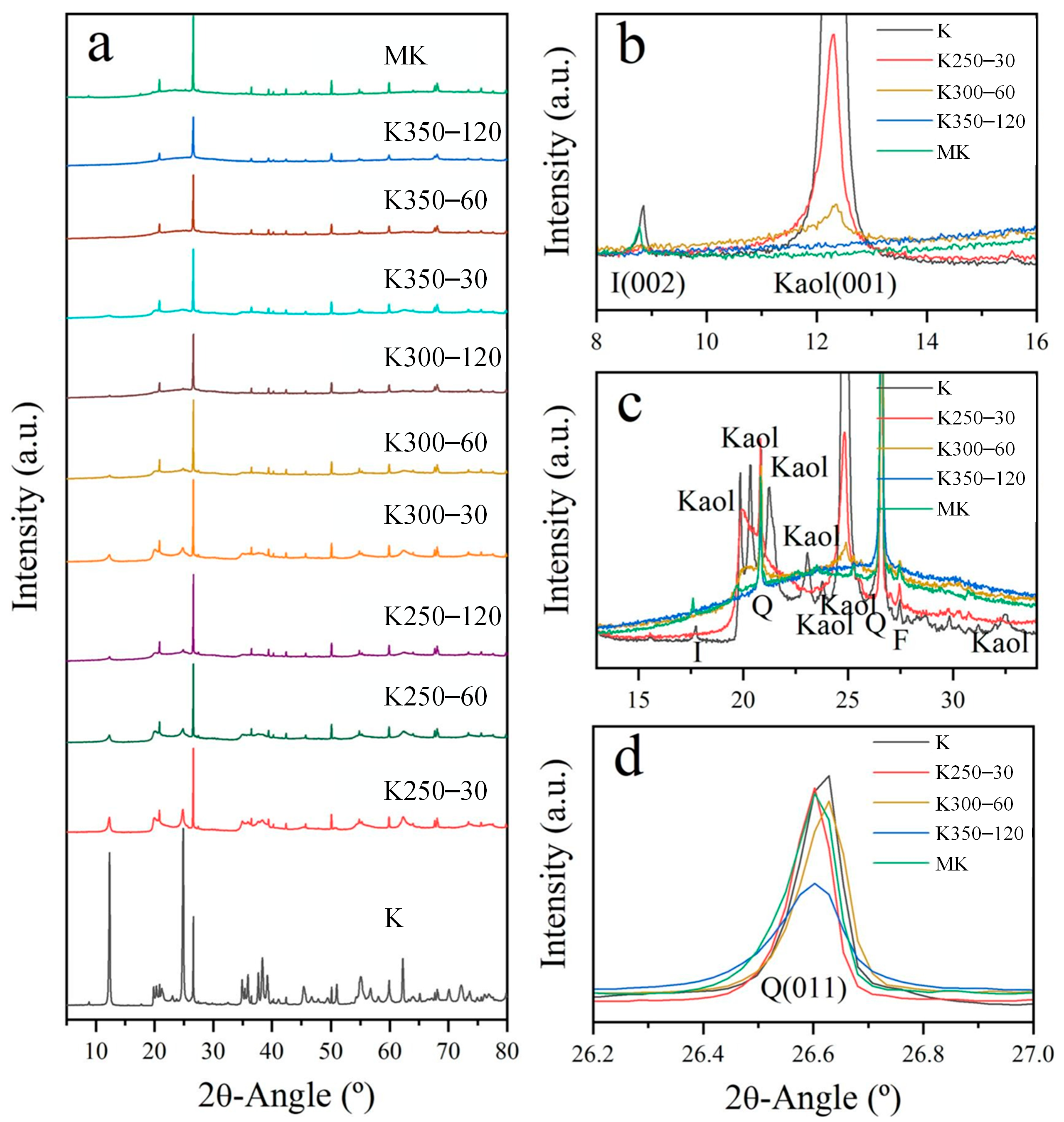

4.1. Core of the Activation Transformation: The Thermal Activation Window of Kaolinite → Metakaolinite (550–750 °C) and the Risk of Over-Burning (>900 °C)

4.2. Volcanic Ash Reaction Kinetics: Secondary Hydration Consumes Ca(OH)2, Generating A C-S-H/C-A-S-H Gel with Pore Optimization Effects

4.3. Performance

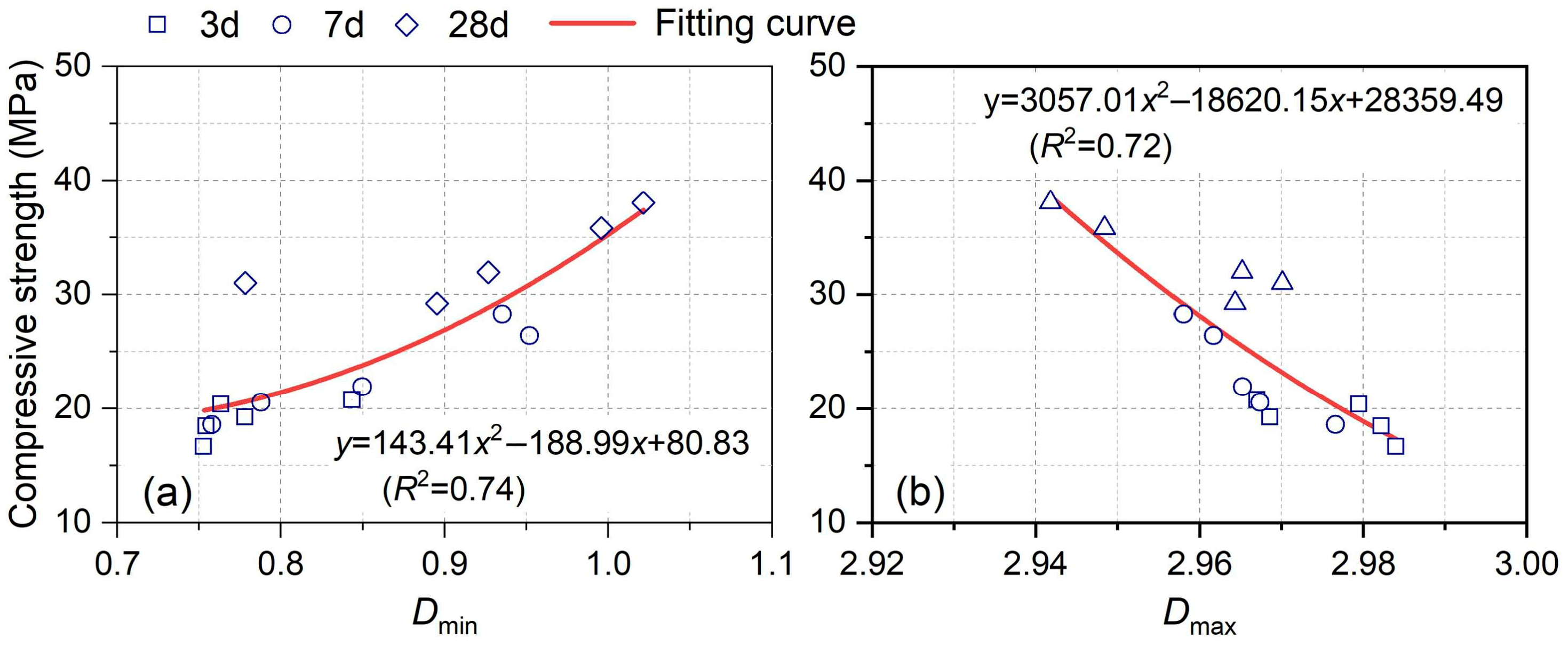

4.3.1. Mechanical Properties: Late Strength Compensation Achieved with a Low Dosage (≤20%)

4.3.2. Comprehensive Improvement in Durability: Mechanisms and Environmental Specificity

- (1)

- Sulfate Attack Resistance: Chemical Depletion and Pore Refinement

- (2)

- Chloride Ion Ingress and Corrosion Inhibition: A Coupled Physico-Chemical Barrier

- (3)

- Carbonation Resistance: Stabilization of the Hydrate Phase Assemblage

- (4)

- Performance in Freeze–Thaw Cycles: Indirect Benefits through Microstructure

4.4. Activation Path Expansion: Energy Efficiency Optimization Potential of Mechanical Activation and Composite Activation (Heat + Grinding)

5. Current Status of Engineering Applications and Challenges in High-Value Transformation

5.1. Current Mainstream Applications: Backfill, Subgrade, and Nonstructural Masonry Blocks—Low-Value, Disposal-Oriented Models

5.2. Disconnection Between High-Performance Research and Engineering Implementation: Lack of Cost, Standards, and Scalability Adaptation

5.3. Strategic Demand for Transition from “Waste Utilization” to “Resource Products”

6. Future Research Directions

6.1. Low-Carbon Activation Technology Innovation: Microwave, Chemical, and Biological Activation as Alternatives to Traditional High-Energy Consumption Calcination

6.2. High-Value Product Development: Geopolymers, Functional Adsorbent Materials, and Specialty Concrete

6.3. Intelligent Quality Control: AI-Assisted Mix Design and Process Optimization Frameworks

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Y.; Ling, T.C. Reactivity activation of waste coal gangue and its impact on the properties of cement-based materials–A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 234, 117424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xin, H.; Wang, D.; Qi, Z.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, W.; Hou, Z. Study on the secondary oxidation behavior and microscopic characteristics of oxidized coal gangue. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 33867–33884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, C.; Zhou, G.; Yin, X.; Wang, C.; Chi, B.; Cao, Y.; Li, R. Assessment of heavy metal in coal gangue: Distribution, leaching characteristic and potential ecological risk. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 32321–32331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhury, R.; Sharma, U.; Thapliyal, P.C.; Singh, L.P. Low-CO2 emission strategies to achieve net zero target in cement sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 417, 137466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Liu, P.; Mo, L.; Liu, K.; Ma, R.; Guan, Y.; Sun, D. Mechanism of thermal activation on granular coal gangue and its impact on the performance of cement mortars. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 45, 103616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Lin, C.; Gao, Y.; Liu, C. Feasibility of preparing red mud-based cementitious materials: Synergistic utilization of industrial solid waste, waste heat, and tail gas. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 285, 124896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, M.; Liao, L.; Lv, G. Environmental hazards and comprehensive utilization of solid waste coal gangue. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2024, 34, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Ding, L.; Guo, Q.; Gong, Y.; Yu, G.; Wang, F. Characterization, carbon-ash separation and resource utilization of coal gasification fine slag: A comprehensive review. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 398, 136554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Dou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B. Effects of the variety and content of coal gangue coarse aggregate on the mechanical properties of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 220, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Zhang, S.; Guo, L. Application of coal gangue as a coarse aggregate in green concrete production: A review. Materials 2021, 14, 6803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Pan, Y.; Zhao, J.; Liu, P.; Wang, Y.; Chu, Y.; Sun, D. Research progress of resourceful and efficient utilization of coal gangue in the field of building materials. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 99, 111526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Luo, Q.; Feng, Q.; Xing, F.; Liu, J.; Gu, Q.; Zeng, X.; Mao, Z.; Zhu, H. Integrated use of Bayer red mud and electrolytic manganese residue in limestone calcined clay cement (LC3) via thermal treatment activation. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 94, 109974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Shi, L.; Ma, D.; Chai, X.; Lin, C.; Zhang, F. Road performance evaluation of unburned coal gangue in cold regions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, R.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Gu, Z.; Wang, J. Impacts of Thermal Activation on Physical Properties of Coal Gangue: Integration of Microstructural and Leaching Data. Buildings 2025, 15, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snehasree, N.; Nuruddin, M.; Moghal, A.A.B. Critical Appraisal of Coal Gangue and Activated Coal Gangue for Sustainable Engineering Applications. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.; Yang, S.; Qiao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Dong, S.; Wang, Y.; Duan, C.; Liu, J. Extraction of valuable critical metals from coal gangue by roasting activation-sulfuric acid leaching. Int. J. Coal Prep. Util. 2024, 44, 1810–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepehrian, M.; Yazdi, F.; Anbia, M. Extraction and green template-free synthesis of high-value mesoporous γ-Al2O3 and SiO2 powders from coal gangue. Powder Technol. 2024, 444, 120023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Osbaeck, B.; Makovicky, E. Pozzolanic reactions of six principal clay minerals: Activation, reactivity assessments and technological effects. Cem. Concr. Res. 1995, 25, 1691–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, S.; Kong, X.; Li, S.; Wang, H.; Liu, D.; Gao, S.; Geng, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, X. Impact of Low-Activity Coal Gangue on the Mechanical Properties and Microstructure Evolution of Cement-Based Materials. Buildings 2025, 15, 3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Cao, Y.; Dong, H.; Zhang, J.; Sun, C. Effect of calcination condition on the microstructure and pozzolanic activity of calcined coal gangue. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2016, 146, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxson, P.; Fernández-Jiménez, A.; Provis, J.L.; Lukey, G.C.; Palomo, A.; van Deventer, J.S. Geopolymer technology: The current state of the art. J. Mater. Sci. 2007, 42, 2917–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, A.; Ojala, T.; Al-Neshawy, F.; Punkki, J. Effect of Slag Content and Carbonation/Ageing on Freeze-Thaw Resistance of Concrete. Nord. Concr. Res. 2024, 71, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tixier, R.; Mobasher, B. Modeling of damage in cement-based materials subjected to external sulfate attack. II: Comparison with experiments. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2003, 15, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quennoz, A.; Scrivener, K.L. Interactions between alite and C3A-gypsum hydrations in model cements. Cem. Concr. Res. 2013, 44, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Feng, P.; Li, W.; Geng, G.; Huang, J.; Gao, Y.; Mu, S.; Hong, J. Effects of pH on the nano/micro structure of calcium silicate hydrate (CSH) under sulfate attack. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 140, 106306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capraro, A.P.B.; Braga, V.; de Medeiros, M.H.F.; Hoppe Filho, J.; Bragança, M.O.; Portella, K.F.; de Oliveira, I.C. Internal attack by sulphates in cement pastes and mortars dosed with different levels of pyrite. J. Build. Pathol. Rehabil. 2017, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štulović, M.; Radovanović, D.; Kamberović, Ž.; Korać, M.; Anđić, Z. Assessment of leaching characteristics of solidified products containing secondary alkaline lead slag. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.D.; Poon, C.S.; Sun, H.; Lo, I.M.C.; Kirk, D.W. Heavy metal speciation and leaching behaviors in cement based solidified/stabilized waste materials. J. Hazard. Mater. 2001, 82, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman, R.N.; Knop, Y.; Querol, X.; Moreno, N.; Muñoz-Quirós, C.; Mastai, Y.; Anker, Y.; Cohen, H. Environmental impact and potential use of coal fly ash and sub-economical quarry fine aggregates in concrete. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 344, 1043–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tironi, A.; Trezza, M.A.; Irassar, E.F.; Scian, A.N. Thermal treatment of kaolin: Effect on the pozzolanic activity. Procedia Mater. Sci. 2012, 1, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Dong, C.; Huang, P.; Sun, Q.; Li, M.; Chai, J. Experimental study on the characteristics of activated coal gangue and coal gangue-based geopolymer. Energies 2020, 13, 2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmidi, D.; Panagiotopoulou, C.; Angelopoulos, P.; Taxiarchou, M. Thermal activation of kaolin: Effect of kaolin mineralogy on the activation process. Mater. Proc. 2021, 5, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Keppert, M.; Pommer, V.; Šádková, K.; Krejsová, J.; Vejmelková, E.; Černý, R.; Koňáková, D. Thermal activation of illitic-kaolinitic mixed clays. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2024, 149, 10533–10544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmerich, K. Spontaneous rehydroxylation of a dehydroxylated cis-vacant montmorillonite. Clays Clay Miner. 2000, 48, 405–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Xu, J.; Xu, Z.; Gao, J.; Zhu, X. Performance of cement-based materials containing calcined coal gangue with different calcination regimes. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 56, 104821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, Y.J.; Moon, H.S. Phase transformation sequence from kaolinite to mullite investigated by an energy-filtering transmission electron microscope. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1999, 82, 2841–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Liu, C.; Duan, G.; Liu, Z.; Jin, L.; Zhou, Y.; Fang, K. Research on the Mechanical Activation Mechanism of Coal Gangue and Its CO2 Mineralization Effect. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wan, J.; Sun, H.; Li, L. Investigation on the activation of coal gangue by a new compound method. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 179, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y. Influence and Mechanism of Coal Gangue Sand on the Properties and Microstructure of Shotcrete Mortar. Materials 2025, 18, 1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wu, K.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, J. Bacterially induced CaCO3 precipitation for the enhancement of quality of coal gangue. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 319, 126102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Choi, H.; Lim, M.; Inoue, M.; Kitagaki, R.; Noguchi, T. Evaluation on the mechanical performance of low-quality recycled aggregate through interface enhancement between cement matrix and coarse aggregate by surface modification technology. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2016, 10, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djenaoucine, L.; Argiz, C.; Picazo, Á.; Moragues, A.; Gálvez, J.C. The corrosion-inhibitory influence of graphene oxide on steel reinforcement embedded in concrete exposed to a 3.5M NaCl solution. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2025, 155, 105835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djenaoucine, L.; Picazo, A.; de la Rubia, M.A.; Gálvez, J.C.; Moragues, A. Effect of graphene oxide on the hydration process and macro-mechanical properties of cement. Boletín La Soc. Española Cerámica Y Vidr. 2024, 63, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Qiao, J.; Jia, R.; Wei, P.; Li, Y.; Ke, G. The influence of carbon imperfections on the physicochemical characteristics of coal gangue aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 409, 133965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, K. Coal gangue in asphalt pavement: A review of applications and performance influence. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e03282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhao, Y.; Luo, Y.; Ding, C.; Hu, B. Investigations on mineralogical characteristics and feasibility of coal gangue as a concrete aggregate from guizhou province, China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 31230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, C.; Yang, Y.; Yang, M.; Di, J.; Sun, Y.; Liang, P.; Wang, Y. Multi-scale analysis of the damage evolution of coal gangue coarse aggregate concrete after freeze–thaw cycle based on CT technology. Materials 2024, 17, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.X.; Chen, W.L.; Yang, R.J. Experimental study on basic properties of coal gangue aggregate. J. Build. Mater. 2010, 13, 739–743. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.Q.; Duan, D.Y.; Huang, D.M.; Chen, Q.; Tu, M.J.; Wu, K.; Wang, D. Lightweight ceramsite made of recycled waste coal gangue & municipal sludge: Particular heavy metals, physical performance and human health. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 376, 134309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.F.; Wang, L.A.; Huang, C. Environmental effects of coal gangue and its utilization. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2016, 38, 3716–3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-García, R.; de Rojas, M.S.; Jagadesh, P.; López-Gayarre, F.; Morán-del-Pozo, J.M.; Juan-Valdes, A. Effect of pores on the mechanical and durability properties on high strength recycled fine aggregate mortar. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 16, e01050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanfilippo, D.; Garcia-Hernández, A.; Alexiadis, A.; Ghiassi, B. Effect of freeze–thaw cycles on the void topologies and mechanical properties of asphalt. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 344, 128085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Cao, M.; Zhang, K.; Yuan, J.; Wang, Y. Wrapped coal gangue aggregate enhancement ITZ and mechanical property of concrete suitable for large-scale industrial use. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 72, 106649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Xu, W.; May, B.M.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Experimental study on the micro-mechanism and compressive strength of concrete with calcined coal gangue coarse aggregate. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, Q. Clarifying and quantifying the immobilization capacity of cement pastes on heavy metals. Cem. Concr. Res. 2022, 161, 106945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Ge, K.; Wang, G.; Geng, H.; Shui, Z.; Cheng, S.; Chen, M. Comparing pozzolanic activity from thermal-activated water-washed and coal-series kaolin in Portland cement mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 227, 117092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Guo, X.; Yao, X.; Han, R.; Li, L.; Zhang, M. Using Chinese coal gangue as an ecological aggregate and its modification: A review. Materials 2022, 15, 4495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Cao, D. Pore characteristics of recycled aggregate concrete and its relationship with durability under complex environmental factors. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 272, 121642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Bai, G.; Yan, F.; Gu, Y.; Zhu, K. Effects of coal gangue coarse aggregate on seismic behavior of columns under cyclic loading. Buildings 2022, 12, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Guo, Z.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y. Mechanical properties and meso-structure response of cemented gangue-fly ash backfill with cracks under seepage-stress coupling. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 250, 118863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noshin, S.; Aslam, M.S.; Kanwal, H.; Khan, M.A.; Ahmad, A. Effects on compressive and tensile strength of concrete by replacement of natural aggregates with various percentages of recycled aggregates. Mehran Univ. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2022, 41, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Pan, Y.; Yu, L.; Liu, P.; Wang, Y.; Liu, K.; Zhang, G.; Sun, D. Probe into the mechanism of water absorption-disintegration of coal gangue aggregates and its influence on concrete properties. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 104, 112321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Xia, J.; Xia, Z.; Chen, M.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y. Study on the mechanical behavior and micro-mechanism of concrete with coal gangue fine and coarse aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 338, 127626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrivener, K.L.; Crumbie, A.K.; Laugesen, P. The interfacial transition zone (ITZ) between cement paste and aggregate in concrete. Interface Sci. 2004, 12, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdipour, I.; Khayat, K.H. Understanding the role of particle packing characteristics in rheo-physical properties of cementitious suspensions: A literature review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 161, 340–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Lian, X.; Zhai, X.; Li, X.; Guan, M.; Wang, X. Mechanical properties of ultra-high performance concrete with coal gasification coarse slag as river sand replacement. Materials 2022, 15, 7552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Duan, Y.; Lyu, X.; Yu, Y.; Xiao, J. Axial compression behavior of coal gangue coarse aggregate concrete-filled steel tube stub columns. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2024, 215, 108534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaabeche, S.; Belaoura, M.; Kahlouche, R. The effects of the quality of recycled aggregates on the mechanical properties of roller compacted concrete. Res. Eng. Struct. Mater. 2025, 11, 587–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Zhang, R.; Guan, X.; Cheng, K.; Gao, Y.; Xiao, Z. Deterioration characteristics of coal gangue concrete under the combined action of cyclic loading and freeze-thaw cycles. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 60, 105165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankur, N.; Singh, N. An investigation on optimizing the carbonation resistance of coal bottom ash concrete with its carbon footprints and eco-costs. Res. Eng. Struct. Mater. 2023, 10, 135–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Bhunia, D.; Singh, S.B.; Aggrawal, M. Mechanical strength and durability of mineral admixture concrete subjected to accelerated carbonation. J. Struct. Integr. Maint. 2018, 3, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Gao, M.; Chen, S.; Ren, H.; Hu, Z.; Li, M.; Guo, C.; Guo, Z. Study on the degradation mechanism and performance improvement of coal gangue-based shotcrete under high-salt dry-wet cycling conditions in underground mining environments. Sci. Prog. 2025, 108, 00368504251387231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, X.; Zhong, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, J. Properties and microstructure of an interfacial transition zone enhanced by silica fume in concrete prepared with coal gangue as an aggregate. ACS Omega 2023, 9, 1870–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, Q. Influence of thermally activated coal gangue powder on the structure of the interfacial transition zone in concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 363, 132408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollivier, J.P.; Maso, J.C.; Bourdette, B. Interfacial transition zone in concrete. Adv. Cem. Based Mater. 1995, 2, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Li, W.; Gan, Y.; Wang, K.; Luo, Z. Nano/microcharacterization and image analysis on bonding behaviour of ITZs in recycled concrete enhanced with waste glass powder. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 392, 131904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Kirkpatrick, R.J.; Poe, B.; McMillan, P.F.; Cong, X. Structure of calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H): Near-, Mid-, and Far-infrared spectroscopy. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1999, 82, 742–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Nicolas, R.; Provis, J.L. The interfacial transition zone in alkali-activated slag mortars. Front. Mater. 2015, 2, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, E.; Zhang, X.; Su, L.; Liu, B.; Li, B.; Li, W. Analysis of calcination activation modified coal gangue and its acid activation mechanism. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 95, 109916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaahmadi, A.; Machner, A.; Kunther, W.; Figueira, J.; Hemstad, P.; De Weerdt, K. Chloride binding in Portland composite cements containing metakaolin and silica fume. Cem. Concr. Res. 2022, 161, 106924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, F.; Pan, Z.; Chen, W.; Muhammad, F.; Zhang, B.; Li, L. Geopolymerization of coal gangue via alkali-activation: Dependence of mechanical properties on alkali activators. Buildings 2024, 14, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Cheng, K.; Zhang, R.; Gao, Y.; Guan, X. Study on the influence mechanism of activated coal gangue powder on the properties of filling body. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 345, 128071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Jin, P.; Ding, Z.; Zhang, W. Surface modification of recycled coarse aggregate based on Microbial Induced Carbonate Precipitation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 328, 129537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, M.; Guo, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, G. Experimental study of microorganism-induced calcium carbonate precipitation to solidify coal gangue as backfill materials: Mechanical properties and microstructure. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 45774–45782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, K.; Pan, M.; Dong, W.; Wang, X.; Zhu, X. Research and Application of Green Technology Based on Microbially Induced Carbonate Precipitation (MICP) in Mining: A Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golewski, G.L. Concrete composites based on quaternary blended cements with a reduced width of initial microcracks. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, T.; Bai, H.; Li, L. Research on the Resistance Performance and Damage Deterioration Model of Fiber-Reinforced Gobi Aggregate Concrete. Materials 2024, 17, 2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Niu, D.; Song, Z. Frost resistance of coal gangue aggregate concrete modified by steel fiber and slag powder. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, A.; Zhang, Z.; Dai, J.-G.; Liu, K.; Wang, Y.; Chu, Y.; Sun, D. Hybrid fiber reinforced ultra-high performance coal gangue geopolymer concrete (UHPGC): Mechanical properties, enhancement mechanism, carbon emission and economic analysis. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 96, 110428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Jiang, W.; Yang, S.; Wang, W. A sustainable low-carbon pervious concrete using modified coal gangue aggregates based on ITZ enhancement. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 377, 134310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperinck, S.; Raiteri, P.; Marks, N.; Wright, K. Dehydroxylation of kaolinite to metakaolin—A molecular dynamics study. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 2118–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, M.; Rożek, P. The effect of calcination temperature on metakaolin structure for the synthesis of zeolites. Clay Miner. 2018, 53, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manosa, J.; Calvo-de la Rosa, J.; Silvello, A.; Maldonado-Alameda, A.; Chimenos, J.M. Kaolinite structural modifications induced by mechanical activation. Appl. Clay Sci. 2023, 238, 106918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazarika, A.; Huang, L.; Babaahmadi, A. Characterisation, activation, and reactivity of heterogenous natural clays. Mater. Struct. 2024, 57, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, L.; Yang, F.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, H.; An, J. Thermal activation and mechanical properties of high alumina coal gangue as auxiliary cementitious admixture. Mater. Res. Express 2024, 11, 025201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Mao, R.; Wu, H.; Liang, X.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Z. Preparation and properties of phosphogypsum-based calcined coal gangue composite cementitious materials. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajac, M.; Song, J.; Ullrich, P.; Skocek, J.; Haha, M.B.; Skibsted, J. High early pozzolanic reactivity of alumina-silica gel: A study of the hydration of composite cements with carbonated recycled concrete paste. Cem. Concr. Res. 2024, 175, 107345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; He, Z.; Niu, K.; Tian, B.; Chen, L.; Bai, W.; Zheng, S.; Yu, G. Analyzing Pore Evolution Characteristics in Cementitious Materials Using a Plane Distribution Model. Coatings 2023, 13, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Chen, T.; Hou, D.; Zhang, X.; Wang, M.; Wang, X. Utilization of coal gangue powder to improve the sustainability of ultra-high performance concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 385, 131482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Lodeiro, I.; Palomo, A.; Fernández-Jiménez, A. An overview of the chemistry of alkali-activated cement-based binders. In Handbook of Alkali-Activated Cements, Mortars and Concretes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 19–47. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Ye, C.; Wen, L.; Yu, B.; Tao, W.; Yang, Z.; Yuan, S. Study on the microscale structure and sulfate attack resistance of cement mortars containing graphene oxide nanoplatelets. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 78, 107727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahyaee, T.; Elize, H.S. A comprehensive study on mechanical properties, durability, and environmental impact of fiber-reinforced concrete incorporating ground granulated blast furnace slag. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e03190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Xia, J.; Fan, C.; Cao, J. Activity of calcined coal gangue fine aggregate and its effect on the mechanical behavior of cement mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 100, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Nadoury, W.W. Eco-friendly concrete using by-products as partial replacement of cement. Front. Mater. 2022, 9, 1043037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Yang, J.; Zou, Y.; Wang, Z. Understanding of the deterioration characteristic of concrete exposed to external sulfate attack: Insight into mesoscopic pore structures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 260, 119932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Ma, B.; Tan, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, T.; Qi, H.; Peng, Y.; Wang, J. Effects of amorphous aluminum hydroxide on chloride immobilization in cement-based materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 231, 117171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Cai, X.; Jaworska, B. Effect of pre-carbonation hydration on long-term hydration of carbonation-cured cement-based materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 231, 117122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, L.; Mao, J.; Li, L.; Shi, Q.; Fang, K.; Li, S.; Deng, X.; Li, G. Microstructural damage and durability of plateau concrete: Insights into freeze-thaw resistance and improvement strategies. Structures 2024, 60, 105888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, R.; Li, X.; Xu, P.; Liu, Q. Thermal activation and structural transformation mechanism of kaolinitic coal gangue from Jungar coalfield, Inner Mongolia, China. Appl. Clay Sci. 2022, 223, 106508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Guan, X.; Zhu, M.; Gao, J. Mechanism on activation of coal gangue admixture. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 2021, 5436482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Jiu, S.; Gao, Q.; Zhao, S.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, F.; Han, D.; Shi, R.; Yuan, K.; Li, J.; et al. Activation of Low-Quality Coal Gangue Using Suspension Calcination for the Preparation of High-Performance Low-Carbon Cementitious Materials: A Pilot Study. Processes 2024, 12, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Han, X.; Sun, Z.; Jin, P.; Li, K.; Wang, F.; Gong, J. Study on the reactivity activation of coal gangue for efficient utilization. Materials 2023, 16, 6321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

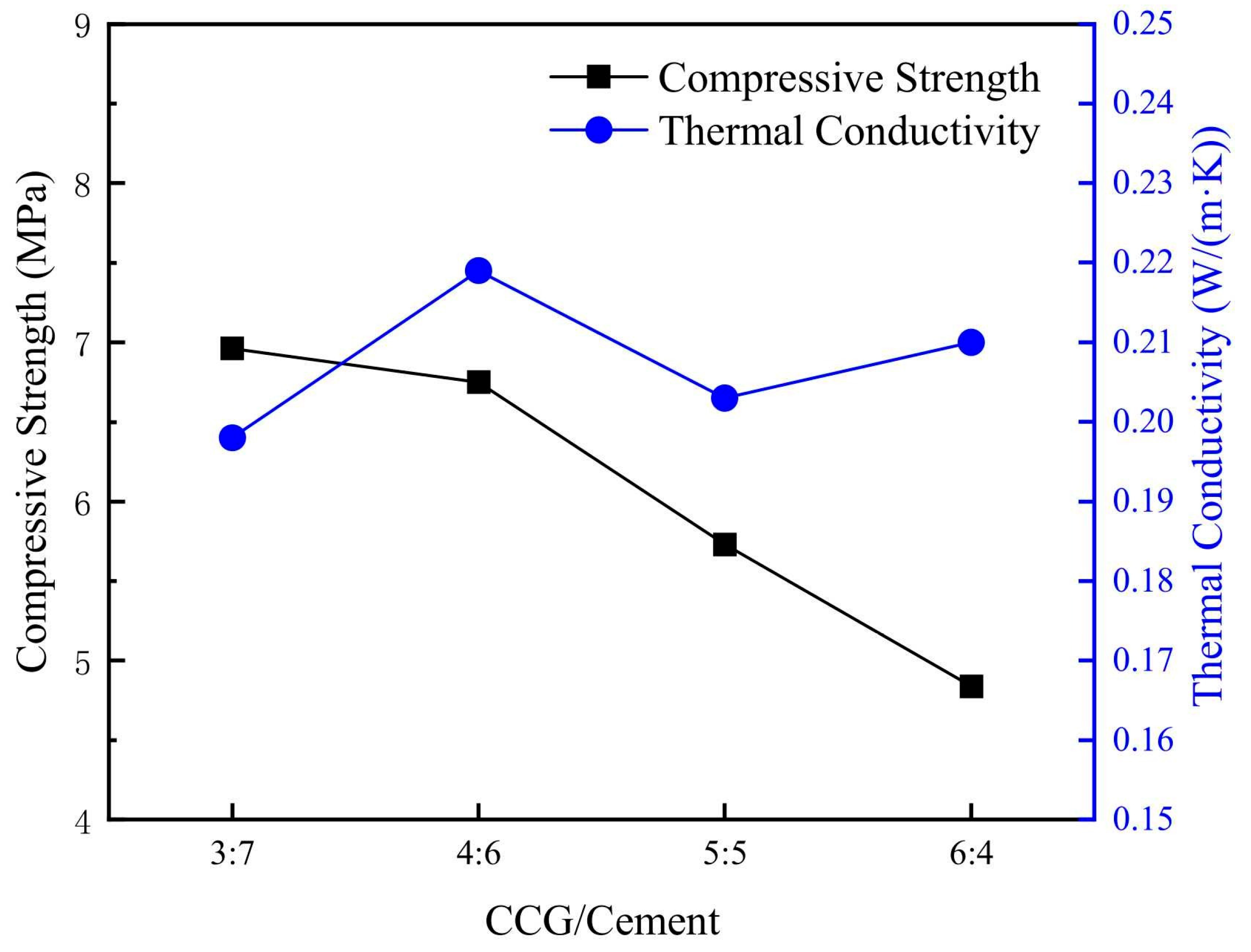

- Zhu, H.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, D.; Mao, M.; Li, J. Development of sustainable pervious concrete: Effects of coal gangue and GGBS on strength, frost resistance, and carbon efficiency. Low-Carbon Mater. Green Constr. 2025, 3, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mischinenko, V.; Vasilchenko, A.; Lazorenko, G. Effect of waste concrete powder content and microwave heating parameters on the properties of porous alkali-activated materials from coal gangue. Materials 2024, 17, 5670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, Y. Microstructure evaluation of fly ash geopolymers alkali-activated by binary composite activators. Minerals 2023, 13, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

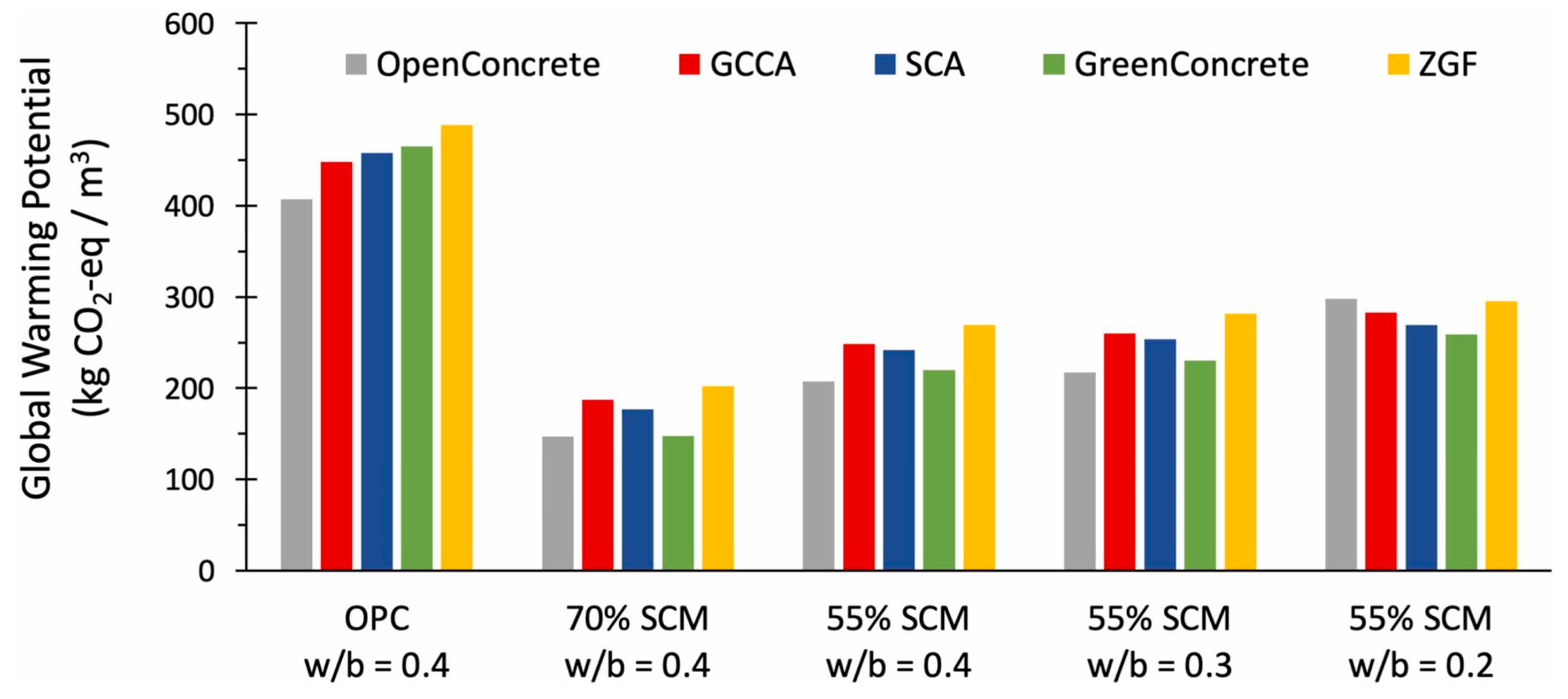

- Li, L.; Shao, X.; Ling, T.C. Life cycle assessment of coal gangue composite cements: From sole OPC towards low-carbon quaternary binder. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 414, 137674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Environment; Scrivener, K.L.; John, V.M.; Gartner, E.M. Eco-efficient cements: Potential economically viable solutions for a low-CO2 cement-based materials industry. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 114, 2–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shao, J.; Zheng, J.; Bai, C.; Zhang, X.; Qiao, Y.; Colombo, P. Fabrication and application of porous materials made from coal gangue: A review. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2023, 20, 2099–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Z.; Chen, Y. Overview of solid backfilling technology based on coal-waste underground separation in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Sun, N.; Tang, H.; Sun, W. A review on comprehensive utilization of red mud and prospect analysis. Minerals 2019, 9, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Ye, J.; Zhong, Y.; Chen, Z. Digital transformation in the Chinese construction industry: Status, barriers, and impact. Buildings 2023, 13, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Long, H.; Zhu, D.; Pan, J.; Li, S.; Guo, Z. Preparation of high-activity mineral powder from coal gangue through thermal and chemical activation. Int. J. Chem. React. Eng. 2025, 22, 1423–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, P.; Li, G. Character of the Si and Al phases in coal gangue and its ash. Acta Geol. Sin.-Engl. Ed. 2009, 83, 1116–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, P.; Wang, C.; Chen, M.; Chai, Z. Engineering property evaluation and multiobjective parameter optimization of argillaceous gangue–filled subgrade based on grey relational analysis. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2023, 35, 04023007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Hora, R.N.; Ahenkorah, I.; Beecham, S.; Karim, M.R.; Iqbal, A. State-of-the-art review of microbial-induced calcite precipitation and its sustainability in engineering applications. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yang, X.Y.; Li, Y.F. Mechanism and structural analysis of the thermal activation of coal-gangue. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 356, 1807–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Q.; Duan, D.Y.; Li, X.; Bai, D.S. Safe and environmentally friendly use of coal gangue in C30 concrete. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2024, 38, 101502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, A.; Garg, N. Quantifying the global warming potential of low carbon concrete mixes: Comparison of existing life cycle analysis tools. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e02832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Bakain, R.Z.; Al-Degs, Y.S.; Issa, A.A.; Jawad, S.A.; Safieh, K.A.; Al-Ghouti, M.A. Activation of kaolin with minimum solvent consumption by microwave heating. Clay Miner. 2014, 49, 667–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kása, E.; Baán, K.; Kása, Z.; Kónya, Z.; Kukovecz, Á.; Pálinkó, I.; Sipos, P.; Szabados, M. The effect of mechanical and thermal treatments on the dissolution kinetics of kaolinite in alkaline sodium aluminate solution under conditions typical to Bayer desilication. Appl. Clay Sci. 2022, 229, 106671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Shi, H.; Dick, W.A. Compressive strength and microstructural characteristics of class C fly ash geopolymer. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2010, 32, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Zhang, J.; Li, M.; Zhou, N.; Song, W.; Wang, Z.; Qi, S. A preliminary study of solid-waste coal gangue based biomineralization as eco-friendly underground backfill material: Material preparation and macro-micro analyses. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 770, 145241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjadi, B.; Chen, W.Y.; Mattern, D.L.; Hammer, N.; Dorris, A. Low-temperature acoustic-based activation of biochar for enhanced removal of heavy metals. J. Water Process Eng. 2020, 34, 101166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Ji, M. Application oriented bioaugmentation processes: Mechanism, performance improvement and scale-up. Bioresource Technology 2022, 344, 126192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, C.; Bi, Y. Alkali-activated steel slag-coal gangue cementitious materials: Strength, hydration, and heavy metal immobilization. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e05120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Feng, J.; He, R.; Chen, X.; Xu, C.; Liao, J.; Jiang, Q. Optimization of compressive strength and exploration of enhancement mechanism of coal gangue-based geopolymers using the Taguchi method. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2025, 39, 2550216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Dong, Y.; Fu, H.; Meng, F.; Sun, W. Study on the adsorption performance of coal gangue-loaded nano-FeOOH for the removal of Pb2+, Cu2+, and Cd2+ from acid mine drainage. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 22161–22178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Lu, C.; Bai, L.; Guo, N.; Xing, Z.; Yan, Y. Removal of Cd2+ and Pb2+ from an Aqueous Solution Using Modified Coal Gangue: Characterization, Performance, and Mechanisms. Processes 2024, 12, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, X.; Tan, Y.; Lu, S.; Wang, Z.; Huang, T. Water absorptivity and frost resistance performance of self-ignition coal gangue autoclaved aerated concrete. J. Infrastruct. Preserv. Resil. 2021, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, T.L.; Nash, W.; Del Galdo, M.; Rezania, M.; Crane, R.; Nezhad, M.M.; Ferrara, L. Coal mining wastes valorization as raw geomaterials in construction: A review with new perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 336, 130213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, Z.; Qi, Y.; Du, M.; Chen, Y.; Liu, T.; Chen, Y.; Yin, Z. Design and application of coal gangue sorting system based on deep learning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veliz Reyes, A.; Olmez, D.; Grout, J.; Carr, A. Digital material passports in the AEC industry: A scoping review and conceptualisation of future research challenges. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xia, P.; Chen, K.; Gong, F.; Wang, H.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Jin, W. Prediction and optimization model of sustainable concrete properties using machine learning, deep learning and swarm intelligence: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 80, 108065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziolkowski, P.; Niedostatkiewicz, M.; Kang, S.B. Model-based adaptive machine learning approach in concrete mix design. Materials 2021, 14, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchewka, A.; Ziolkowski, P.; García Galán, S. Real-time prediction of early concrete compressive strength using AI and hydration monitoring. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, S.; Dong, S.; Ashour, A.; Han, B. Development of sensing concrete: Principles, properties and its applications. J. Appl. Phys. 2019, 126, 241101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, B.; Yu, J.; Chen, Z.; Osman, A.I.; Farghali, M.; Ihara, I.; Hamza, E.H.; Rooney, D.W.; Yap, P.S. Artificial intelligence for waste management in smart cities: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 1959–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, J.; Li, A.; Zhou, N. Reutilisation of coal gangue and fly ash as underground backfill materials for surface subsidence control. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 120113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Origin/Sample Type | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | CaO | MgO | SO3 | LOI | Main Mineral Phases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Samples from North China | 57.8 | 31.7 | 4.2 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.58 | 3.2 | Kaolinite and Quartz |

| Typical Samples from Southwest China | 58.5 | 25.3 | 8.7 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.72 | 4.1 | Kaolinite and Pyrite |

| Spanish Samples | 48.6 | 36.2 | 5.1 | 2.3 | 1.5 | 0.45 | 5.8 | Kaolinite and Illite |

| Appalachian Samples from the United States | 52.4 | 28.9 | 7.3 | 3.8 | 1.7 | 0.63 | 5.2 | Kaolinite and Calcite |

| Global Range of Variability | 39–60 | 15–36 | 2–15 | 0.5–8.0 | 0.5–3.0 | 0.29–0.72 | <4−20+ | - |

| Range of Applicability for High Activity | 45–55 | 30–38 | <8 | <3 | <2 | <0.6 | <6 | Mainly Kaolinite |

| Activation Methods | Mechanism of Action | Optimal Parameters | Activity Gain | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Activation | Dehydroxylation and Lattice Disorder | 550–750 °C | High (significant activity enhancement) | High energy consumption, narrow temperature window, risk of overburning |

| Mechanical Activation | Lattice Defects and Increase in Specific Surface Area | Grind to a size of <0.074 mm | Moderate (limited activation) | High energy consumption, limited improvement in activity |

| Composite Activation | Thermally Induced Phase Transition + Mechanical Milling Synergy | 700 °C with fine grinding | Maximum (synergistic effect) | Complex process, high cost |

| Parameter | Coal Gangue Aggregate (CG) | Natural Aggregate (NA) |

|---|---|---|

| Water Absorption (%) | 5.0–9.0 | 0.5–1.35 |

| Crushing Value (%) | 16.0–23.0 | ~11.2 |

| Porosity | 3–5 times higher than NA | Baseline |

| Apparent Density (g/cm3) | 2.4–2.8 | ~2.72 |

| Bulk Density (kg/m3) | 1400–1800 | ~1560 |

| Material Defect Category | Specific Characteristics | Mechanism of Action | Impact on Concrete Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Variability | High Carbon Content (>15% LOI) | Interfering with Hydration, Reducing Air-Entrainment Efficiency | Poor Workability, Significantly Reduced Freeze Resistance |

| High Sulfur Content (0.29–0.72% SO3) | Sulfate Formation through Oxidation in Alkaline Environment | Internal Sulfate Attack, Leading to Expansion and Cracking | |

| Heavy Metals (As, Pb, Cd, Cr) | Leaching Risk under pH Variation | Long-term Environmental Safety Concerns | |

| Mineralogical Characteristics | Unactivated Kaolinite | Lattice Structure Stability, Chemical Inertness | Low Volcanic Ash Activity, Insufficient Early Strength |

| Improper Activation Temperature | <550 °C: Under-activation; >900 °C: Recrystallization | Insufficient Activity or Permanent Deactivation | |

| Physical Structural Defects | High Porosity | Uneven Water Absorption and Distribution | Slump Loss, Local Water-to-Cement Ratio Imbalance |

| Low Strength | “Strong Matrix—Weak Aggregate” Mismatch | The compressive strength decreases monotonically with the replacement ratio. | |

| Connected Pore Network | Increased CO2 Penetration Pathway | The carbonation depth increases. | |

| Pore Water Freezing Expansion | Freeze Expansion Stress | Microcrack propagation, rapid decrease in dynamic elastic modulus. | |

| High Water Absorption + Surface Activity | ITZ Water-to-Cement Ratio Reduction + Secondary Hydration | Chloride ion permeability “abnormally decreases”. |

| Technology Category | Representative Methods | Mechanism of Action | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aggregate Substrate Modification | Pre-wetting | Pore saturation, internal curing | Short timeliness, requires precise control of pre-wetting degree |

| Calcination (600–800 °C) | Aggregate sintering + surface activation | High energy consumption, which may increase CO2 emissions | |

| Sodium silicate coating | Formation of silica gel within the pores | Complex process, higher cost | |

| Biological Treatment | MICP | Microbial-induced CaCO3 precipitation | Long processing cycle, challenges in strain stability |

| Matrix Reinforcement | SCM (Supplementary Cementitious Materials) | Microfilling + Volcanic Ash Reaction | Need to optimize the dosage to avoid loss of workability |

| Fiber Reinforced | Crack Bridging + Energy Dissipation | Cost increase, challenges in dispersibility |

| Activation Methods | Optimal Temperature/ Parameters | Increase in Activity Index | Energy Consumption Level | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Activation | 550–750 °C | High (Up to 95%+ of the reference cement) | High | Narrow temperature window, high risk of overburning (>900 °C) |

| Mechanical Activation | Grind to < 0.074 mm | Moderate (Limited Activation) | Medium-High | Limited activity improvement, difficult to meet high-performance requirements |

| Composite Activation | 700 °C + Fine Grinding | Highest (Synergistic Enhancement) | High | Complex process, high cost, and difficulty in quality control |

| Activation Methods | Energy Density (kJ/kg) | Activity Index (%) | Implicit Carbon (ton CO2/ton) | Process Complexity | Applicable Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional thermal activation (750 °C) | 850 | 92–95 | 0.32 | Low | Kaolinite content > 35% |

| Mechanical activation (fine grinding) | 380 | 75–80 | 0.15 | Middle | Low activation requirement applications |

| Composite activation (650 °C + grinding) | 620 | 96–98 | 0.23 | High | High-performance requirement applications |

| Microwave activation (600 °C) | 490 | 90–93 | 0.18 | High | Challenges of scaled production |

| Application Dimensions | Laboratory Research Focus | Current Status of Engineering Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Technical Path | High-Performance Aggregate Modification, Precise Thermal Activation, Composite Reinforcement | Direct use of raw materials, simple crushing treatment |

| Performance Standards | Mechanical Properties, Durability, and Long-Term Stability | Basic physical properties, short-term stability |

| Value Positioning | Cement/aggregate substitutes, high value-added building materials | Filler materials, low-cost disposal solutions |

| Mixing Proportion | Precision optimization (aggregate ≤ 45%, SCM ≤ 20%) | The higher, the better (usually >60%) |

| Quality Control | Strict grading, activation parameter control | Extensive management, lack of standards |

| Evaluation Dimensions | Laboratory Research Characteristics | Practical Reality of Engineering Applications | Cause of the Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost Structure | Focusing on Performance Optimization While Ignoring Scale-up Costs | Strict Cost Control, Material Cost Proportion > 30% | High Activation Energy Consumption, Increased Technological Complexity |

| Quality Control | Strict Raw Material Selection with Small-Batch Precision Control | High Variability in Raw Materials, Uncontrollable Site Conditions | Lack of Classification Standards and Quality Control Systems |

| Performance Goals | Pursuit of Maximizing Single Performance (e.g., Strength, Impermeability) | Meet Minimum Specification Requirements, Focus on Construction Convenience | Balance and Trade-off Between Performance, Cost, and Timeline |

| Technical Complexity | Adopting Multi-Level Optimization Strategies (Aggregate Modification + Matrix Reinforcement) | Prioritize Simple and Direct Solutions (Direct Substitution) | Adaptability of Construction Techniques and Worker Skill Limitations |

| Verification Cycle | Short-term (28–90 days) performance test | Reliability Requirements for the Entire Lifecycle (25–50 Years) | Lack of Long-term Durability Data and Risk Mitigation |

| Activation Technology | Optimal Temperature/Conditions | Technology Maturity | Main Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional thermal activation (benchmark) | 750 °C, 60 min | High (industrialization) | High energy consumption, large carbon footprint |

| Microwave activation | 550–650 °C, 10–15 min | Pilot scale (laboratory to pilot scale) | Scaled equipment, energy uniformity |

| Chemical activation (alkali-assisted) | 500 °C + 5%NaOH | Pilot scale | Reagent recovery, wastewater treatment |

| Non-thermal chemical activation | Room temperature + 8 M NaOH | Laboratory scale | Reagent cost, environmental impact |

| Biological activation | 30 °C, 7–14 Days | Low (Proof of concept) | Long cycle, complex process control |

| Composite activation (thermal + chemical + mechanical) | 400 °C + 2% Na2SiO3 + grinding | Medium-high (Demonstration project) | Process integration, quality control |

| Product Type | Core Value | Performance Advantages | Coal Gangue Utilization Rate | Application Scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaline-Activated Geopolymer | Main Cementing Phase | Early Strength Acid Resistance Low Carbon | >80% | Industrial Flooring, Corrosion-Resistant Structures, Prefabricated Components |

| Functional Adsorption Materials | Environmental Remediation Agent | High Adsorption Capacity Renewable | 100%(Powder) | Wastewater Treatment, Soil Remediation, Emergency Pollution Removal |

| Corrosion-Resistant Concrete | Durability Enhancement | Sulfate Resistance Low Permeability | 35–45% (Aggregates + Powder) | Marine Engineering, Chemical Facilities, Underground Structures |

| Radiation Shielding Concrete | Functional Filler | Neutron Moderation Structural Stability | 30–35% | Medical Facilities, Nuclear Waste Disposal, Laboratory |

| System Modules | Core Technology | Function Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Raw Material Database | Blockchain + Cloud Storage | National Standardization Classification of Coal Gang |

| AI Proportioning Design | Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) | Performance-Oriented Precise Mix Ratio Generation |

| Process Monitoring | Multimodal Sensing + Edge Computing | Real-time Quality Feedback and Dynamic Regulation |

| Collaborative Optimization | Digital Twin + Multi-Objective Optimization | Performance-Cost-Carbon Balance of Multi-Waste System |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Xue, Y. A Comprehensive Review on Dual-Pathway Utilization of Coal Gangue Concrete: Aggregate Substitution, Cementitious Activity Activation, and Performance Optimization. Buildings 2026, 16, 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020302

Wang Y, Zhu L, Xue Y. A Comprehensive Review on Dual-Pathway Utilization of Coal Gangue Concrete: Aggregate Substitution, Cementitious Activity Activation, and Performance Optimization. Buildings. 2026; 16(2):302. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020302

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yuqi, Lin Zhu, and Yi Xue. 2026. "A Comprehensive Review on Dual-Pathway Utilization of Coal Gangue Concrete: Aggregate Substitution, Cementitious Activity Activation, and Performance Optimization" Buildings 16, no. 2: 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020302

APA StyleWang, Y., Zhu, L., & Xue, Y. (2026). A Comprehensive Review on Dual-Pathway Utilization of Coal Gangue Concrete: Aggregate Substitution, Cementitious Activity Activation, and Performance Optimization. Buildings, 16(2), 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020302