Exploring the Spatial Distribution of Traditional Villages in Yunnan, China: A Geographic-Grid MGWR Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Geographic Grid Analysis

2.3.2. Data Processing

2.3.3. Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

2.3.4. Models for Interpreting the Spatial Distribution of Traditional Villages

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Distribution Characteristics of Traditional Villages

3.1.1. Spatial Distribution Patterns

3.1.2. Spatial Distribution Balance

3.1.3. Spatial Density Characteristics

3.1.4. Results of Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

3.2. Influencing Factors of Traditional Village Spatial Distribution

3.2.1. Variable Selection and Model Comparison

3.2.2. Spatial Heterogeneity Analysis of Traditional Village Distribution

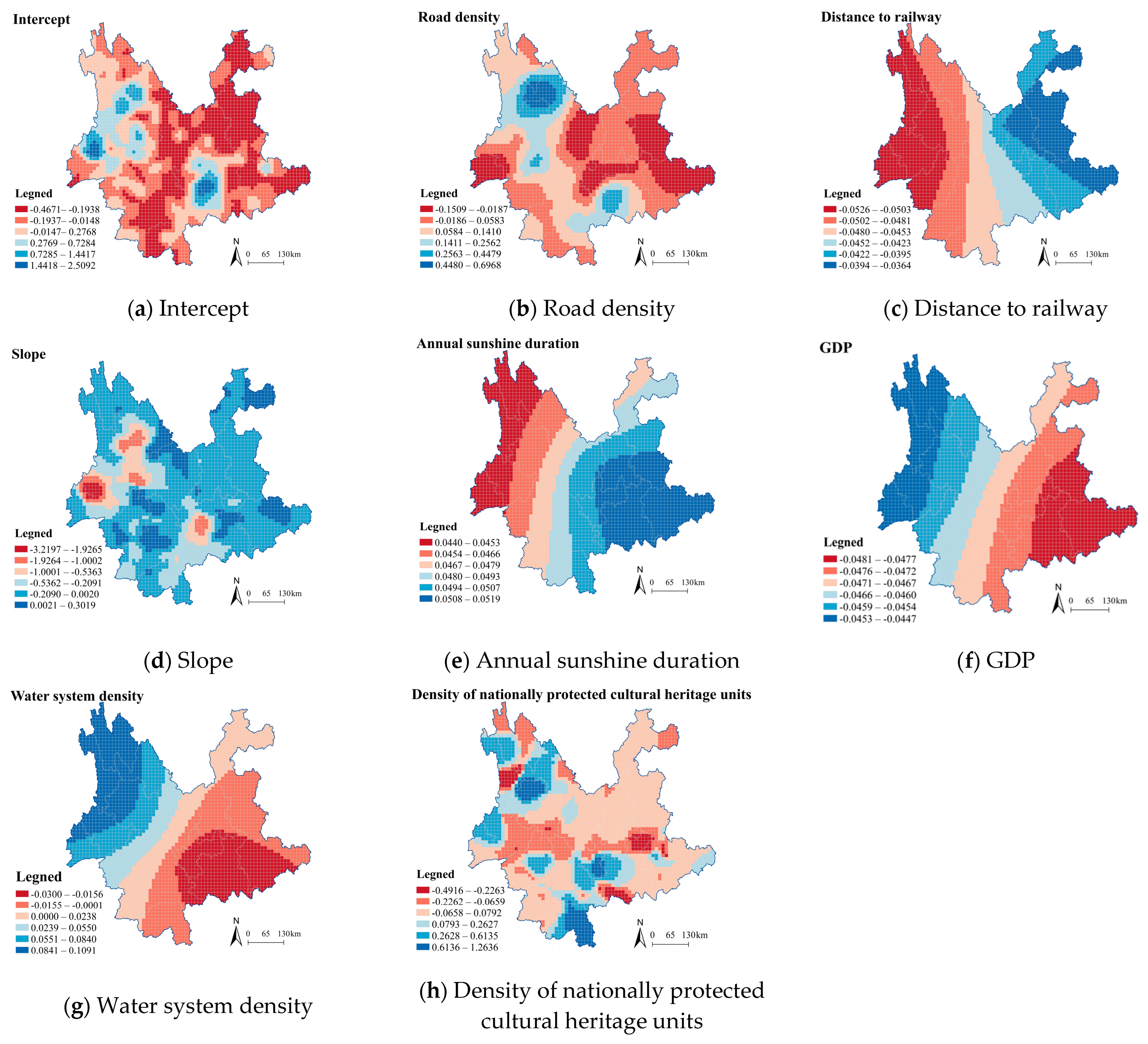

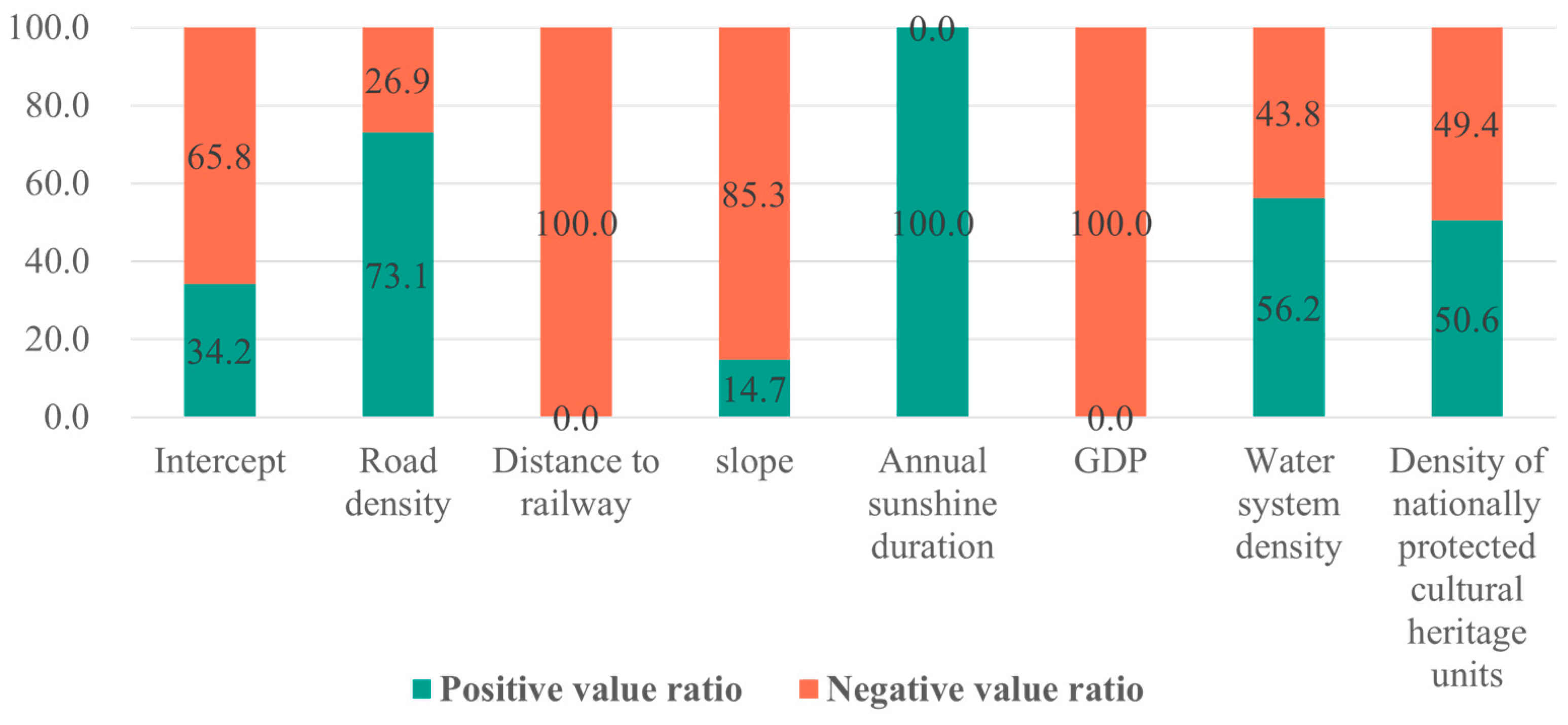

3.2.3. Influencing Factors Interpretation

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

4.1. Conclusions

- (1)

- Traditional villages display significant spatial clustering with a highly uneven distribution. Approximately 62.68% are concentrated in Dali, Baoshan, Honghe, and Lijiang, forming distinct high-density cores. Other regions are comparatively sparse, yielding a typical spatial pattern of “concentrated distribution with localized clustering”.

- (2)

- The spatial distribution shows strong positive spatial autocorrelation and an overall tendency of “more in the northwest, fewer in the southeast, dense in mountainous areas,” concentrated in northwestern Yunnan and plateau mountain regions. Clustering is not random but reflects the combined effects of natural geographic and socioeconomic factors, with marked spatial heterogeneity. MGWR further distinguishes variables with relatively stable, province-wide effects (distance to railway, annual sunshine duration, and GDP) from those with clearly local, context-dependent effects (road density, slope, water-system density, and the density of nationally protected cultural heritage units). By contrast, distance to the county center and elevation, which are often assumed to be key siting constraints, are significant in the global OLS model but show no spatially significant coefficients in the MGWR results, acting more as background conditions than as spatially differentiating drivers.

- (3)

- Natural geographic factors are the dominant associated factors of the spatial distribution of traditional villages in Yunnan. Comparing standardized regression coefficients indicates that sunshine duration and water availability exhibit stronger positive associations with village distribution, underscoring their leading roles in village presence. In particular, favorable sunshine conditions and water availability are strongly associated with a higher presence of traditional villages, providing supportive environmental foundations for settlement persistence [12]. Traditional villages are typically distributed along river systems [33], yet they usually maintain an appropriate distance from rivers to reduce flood risks while ensuring convenient access to water resources [13]. MGWR also reveals that the effect of slope is not spatially uniform: although slope is generally negatively associated with village presence across most of the province, small pockets of relatively level high-altitude areas (e.g., Dali and Lijiang) show positive slope coefficients, suggesting that the gently inclined highland terrain there is associated with higher village presence and long-term persistence of traditional villages [20].

- (4)

- Socioeconomic development and transportation factors exert secondary influences, generally displaying a negative correlation with traditional village distribution. Areas with higher levels of economic development and more convenient transportation tend to experience a decline in the number of traditional villages, largely due to the accelerated processes of urbanization and modernization [34]. Conversely, economically underdeveloped and less accessible areas, owing to lower external disturbances, are more favorable for the preservation of the authenticity and cultural heritage of traditional villages [13]. MGWR clarifies that this influence is spatially differentiated: distance to railway and GDP act as broadly suppressive factors at the provincial scale, whereas the impact of road density reverses from negative in many eastern and southern cells to positive in tourism-oriented regions such as Dali and Lijiang, where improved road access supports heritage-based revitalization rather than loss. This pattern highlights how local development models and policy orientations condition the relationship between infrastructure expansion and traditional village survival.

- (5)

- Historical and cultural factors, represented by the presence of nationally protected cultural heritage units, have a mixed but spatially structured effect on the distribution of traditional villages. Regions with dense clusters of heritage units tend, in some cases, to have fewer traditional villages, reflecting potential pressures from tourism development and planning controls, whereas in other areas, heritage units and villages co-cluster, indicating a positive guiding role of heritage protection policies. Overall, the MGWR results point to substantial regional variation in how heritage resources shape village patterns, suggesting that the strength and spatial reach of protection efforts still have room for improvement [30].

4.2. Recommendations

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Future Work

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MGWR | Multiscale geographically weighted regression |

| GWR | Geographically weighted regression |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| GDP | Gross domestic product |

| OSM | OpenStreetMap |

| AICc | Corrected Akaike Information Criterion |

| LISA | Local Indicators of Spatial Association |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

References

- Wang, X.; Zhu, Q. Influencing Factors of Traditional Village Protection and Development from the Perspective of Resilience Theory. Land 2022, 11, 2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.J.; Zhang, J.H.; Sun, F.; Cao, S.S.; Kan, Y.; Wang, C.; Xu, D. Spatial Distribution and Impact Mechanism of Traditional Villages in Southwest China. Econ. Geogr. 2021, 41, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Ahmad, Y. Heritage Protection Perspective of Sustainable Development of Traditional Villages in Guangxi, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, Y. Appraisal and Selection of “Chinese Traditional Villages” and a Study on Their Spatial Distribution. Archit. J. 2013, 12, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H. Value Orientation of Traditional Village Protection Reflected in the Selection Indicators of Chinese Traditional Villages. Urban Dev. Stud. 2024, 31, 82–90. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T.W.; Zhang, D.Y. Research on the Evolution of Selection Indicators and Value Assessment of Chinese Traditional Villages. City Plan Rev. 2022, 46, 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H.; Tong, Y. Spatial Differentiation of Traditional Villages Using ArcGIS and GeoDa: A Case Study of Southwest China. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 68, 101416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, L. Spatial Distribution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Traditional Villages in Fujian Province, China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Han, N.; Zhang, B.; Lu, C.; Yang, M.; Zhai, F.; Li, H. Spatial and Temporal Distribution Characteristics and Evolution of Traditional Villages in the Qihe River Basin of China. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.S.; Wang, X.R.; Li, X.J. Spatial Distribution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Chinese Traditional Villages. Econ. Geogr. 2020, 40, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiangcuo, T. Spatial Distribution Characteristics of Ethnic Traditional Villages Based on Schema Language. Acad. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2022, 5, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Wu, L.; Xie, L.; Liu, Z.; Li, Z. Study on the Distribution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Traditional Villages in the Yunnan, Guangxi, and Guizhou Rocky Desertification Area. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, W. Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Traditional Village Distribution in China. Land 2022, 11, 1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xiong, W.; Shao, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, F. Analyses of the Spatial Morphology of Traditional Yunnan Villages Utilizing Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Remote Sensing. Land 2023, 12, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, R.; Li, Q.; Zhang, X.; He, X. Spatial Sifferentiation and Differentiated Development Paths of Traditional Villages in Yunnan Province. Land 2023, 12, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, G.; Li, X.; Tian, S.; Li, H.; Song, Y. Influence of Human Settlements Factors on the Spatial Distribution Patterns of Traditional Villages in Liaoning Province. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Yan, H. Analyzing the Causes of Spatial Differentiation of the Traditional Villages in Gansu Province, Western China. GEP 2020, 8, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, X.; Lin, Q.; Qiu, J. Spatial Distribution of Ethnic Villages in the Mountainous Region of Northwest Yunnan and Their Relationship with Natural Factors. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Hu, J.; Liu, D.J.; Li, Y.J.; Chen, Y.; Hu, S.L. Spatial Differentiation of Ethnic Traditional Villages in Guizhou Province and the Influencing Factors. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2022, 36, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Wang, Y. Spatial Differentiation Patterns of Traditional Villages in Taihang Mountain Area and Influencing Mechanisms: A MGWR Model Based Analysis. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2024, 38, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.Q.; Li, F.; Gao, J.B.; Leica, B. Spatial Distribution and Influencing Factors of Chinese Traditional Villages Based on Geographic Grid. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2024, 44, 995–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Sun, J.; Deng, L.; Luo, J.; Tian, Y. Characteristics of Multi-Scale Spatiotemporal Pattern and Influencing Factors of Chinese Traditional Villages. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2025, 32, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Lu, H.; Huang, Z.; Zhu, Z. Spatiotemporal Distribution of Chinese Traditional Villages and Its Influencing Factors. Econ. Geogr. 2023, 43, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, D. Research on the Spatial Distribution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Traditional Villages in Yunnan Province. J. Guizhou Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2022, 39, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobler, W.R. A Computer Movie Simulating Urban Growth in the Detroit Region. Econ. Geogr. 1970, 46, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finley, A.O. Comparing Spatially-varying Coefficients Models for Analysis of Ecological Data with Non-stationary and Anisotropic Residual Dependence. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2011, 2, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsdon, C.; Fotheringham, A.S.; Charlton, M.E. Geographically Weighted Regression: A Method for Exploring Spatial Nonstationarity. Geogr. Anal. 1996, 28, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotheringham, A.S.; Yang, W.; Kang, W. Multiscale Geographically Weighted Regression (MGWR). Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2017, 107, 1247–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wang, L.; He, J.; Jung, T. Restorative Perception of Urban Streets: Interpretation Using Deep Learning and MGWR Models. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1141630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, J.; Chen, W.; Zeng, J. Spatial Distribution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Traditional Villages in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.L.; Teng, Y.B.; Fan, Y.M.; Li, L.P. Spatial Distribution and Influencing Factors of Traditional Villages in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. J. Guilin Univ. Technol. 2021, 41, 580–588. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, G. Analysis of the Spatial Distribution and Influencing Factors of China National Forest Villages. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Ceola, S.; Paik, K.; McGrath, G.; Rao, P.S.C.; Montanari, A.; Jawitz, J.W. Globally Universal Fractal Pattern of Human Settlements in River Networks. Earth’s Future 2018, 6, 1134–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Zhao, S. Research on Spatial Characteristics and Influence Mechanism of Traditional Villages and Intangible Cultural Heritage in Southwest China. Areal Res. Dev. 2024, 43, 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Na, R.; Shen, Z.; Deng, X. Impact of Major Function-Oriented Zone Planning on Spatial and Temporal Evolution of “Three Zone Space” in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Ma, H.; Bao, C.; Wang, Z.; Li, G.; Sun, S.; Fan, Y. Urban–Rural Human Settlements in China: Objective Evaluation and Subjective Well-Being. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Wu, Y.; Bian, C.; Gao, X. Spatial Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Chinese Traditional Villages in Eight Provinces the Yellow River Flows Through. River Res. Apps 2023, 39, 1255–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, D.; Xu, W.; Chen, H.; Li, J.; Mo, F. Explainable Dimensionality Reduction (XDR) to Unbox AI ‘Black Box’ Models: A Study of AI Perspectives on the Ethnic Styles of Village Dwellings. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Feldman, M.W.; Li, S. The Status of Family Resilience: Effects of Sustainable Livelihoods in Rural China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2021, 153, 1041–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Type | Dimension | Specific Indicator | Calculation Method | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | - | Density of traditional villages | Mean density of traditional villages | Catalogue of Chinese Traditional Villages (Batches 1–6), China Traditional Villages website; village coordinates geocoded via the Amap (Gaode) Geocoding API (https://lbs.amap.com/tools/picker, accessed on 11 December 2024) |

| Independent Variables | Traffic Accessibility | Distance to county center | Distance from each grid cell to the nearest county center | The API of the Gaode Open Platform |

| Road density | Mean road density within each grid cell | OSM | ||

| Distance to railway | Distance from each grid cell to the nearest railway | |||

| Natural Topography | Elevation | Mean elevation within each grid cell | Geospatial Data Cloud | |

| Slope | Mean slope within each grid cell (calculated based on elevation data) | |||

| Water system density | Mean water system density within each grid cell | OSM | ||

| Climatic Conditions | Annual sunshine duration | Mean annual sunshine duration within each grid cell | China Meteorological Elements Annual Spatial Interpolation Dataset | |

| Annual average temperature | Mean annual temperature within each grid cell | |||

| Annual precipitation | Mean annual precipitation within each grid cell | |||

| Socioeconomic Factors | Gross domestic product (GDP) | Mean GDP within each grid cell | China GDP Spatial Distribution Kilometer Grid Dataset | |

| Population density | Mean population density within each grid cell | |||

| Urbanization rate | Mean urbanization rate within each grid cell | Seventh National Population Census | ||

| Historical and Cultural Factors | Proportion of ethnic minority population | Mean proportion of ethnic minority population within each grid cell | ||

| Density of national intangible cultural heritage sites | Mean density within each grid cell | Global Change Research Data Publishing & Repository | ||

| Density of nationally protected cultural heritage units | Mean density within each grid cell |

| Batch | Nearest Neighbor Ratio (R) | Z-Score | p-Value | Distribution Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batch 1 | 0.781 | −3.305 | 0.000 *** | Clustered |

| Batch 1–2 (cumulative) | 0.694 | −10.035 | 0.000 *** | Clustered |

| Batch 1–3 (cumulative) | 0.747 | −10.826 | 0.000 *** | Clustered |

| Batch 1–5 (cumulative) | 0.741 | −12.285 | 0.000 *** | Clustered |

| Batch 1–5 (cumulative) | 0.749 | −12.772 | 0.000 *** | Clustered |

| Batch 1–6 (cumulative) | 0.733 | −14.215 | 0.000 *** | Clustered |

| Variable | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Probability | Robust_SE | Robust_t | Robust_Pr | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.014 | 17.914 | 0.000 *** | 0.014 | 17.946 | 0.000 *** | -- |

| Road density | 0.019 | 2.430 | 0.015 * | 0.020 | 2.329 | 0.019 * | 1.741 |

| Distance to railway | 0.016 | −2.203 | 0.028 * | 0.012 | −2.926 | 0.003 * | 1.195 |

| Distance to the county center | 0.016 | −3.508 | 0.000 *** | 0.013 | −4.350 | 0.000 *** | 1.291 |

| Slope | 0.018 | −4.194 | 0.000 *** | 0.018 | −4.125 | 0.000 *** | 1.571 |

| Elevation | 0.018 | 1.674 | 0.035 * | 0.014 | 2.199 | 0.027 * | 1.598 |

| Annual sunshine duration | 0.017 | 3.080 | 0.002 ** | 0.010 | 5.363 | 0.000 *** | 1.398 |

| GDP | 0.017 | −7.278 | 0.000 *** | 0.035 | −3.487 | 0.000 *** | 1.371 |

| Water system density | 0.016 | 2.391 | 0.017 * | 0.019 | 1.974 | 0.048 * | 1.163 |

| Density of nationally protected cultural heritage units | 0.016 | 11.297 | 0.000 *** | 0.066 | 2.802 | 0.005 ** | 1.271 |

| Koenker (BP) | 183.468 | ||||||

| Koenker (BP)’s Prob | 0.000 *** | ||||||

| Moran’s I | 0.244211 | ||||||

| Z-score | 7.970674 | ||||||

| p-value | 0.000000 |

| Model | R2 | Adjusted R2 | AICc |

|---|---|---|---|

| OLS | 0.092 | 0.089 | 7132.17 |

| GWR | 0.255 | 0.229 | 6989.96 |

| MGWR | 0.555 | 0.495 | 6675.56 |

| Indicator | MGWR Bandwidth | Proportion Significant (%) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 45 | 6.29 | Evident spatial heterogeneity |

| Road density | 211 | 7.29 | Weak overall heterogeneity, significant in some areas |

| Distance to railway | 3005 | 100.00 | Significant and stable global effect |

| Distance to the county center | 3005 | 0.00 | Significant in OLS but not spatially significant in MGWR; can be treated as an ineffective variable |

| Slope | 69 | 11.51 | Locally significant with clear spatial heterogeneity |

| Elevation | 3005 | 0.00 | Significant in OLS but not spatially significant in MGWR; can be treated as an ineffective variable |

| Annual sunshine duration | 3005 | 67.59 | Significant and stable global effect |

| GDP | 3005 | 100.00 | Significant and stable global effect |

| Water system density | 1600 | 29.82 | Moderate spatial heterogeneity |

| Density of nationally protected cultural heritage units | 97 | 11.58 | Mainly a locally significant variable |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yin, X.; Hou, S.; Han, X.; Kuang, B. Exploring the Spatial Distribution of Traditional Villages in Yunnan, China: A Geographic-Grid MGWR Approach. Buildings 2026, 16, 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020295

Yin X, Hou S, Han X, Kuang B. Exploring the Spatial Distribution of Traditional Villages in Yunnan, China: A Geographic-Grid MGWR Approach. Buildings. 2026; 16(2):295. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020295

Chicago/Turabian StyleYin, Xiaoyan, Shujun Hou, Xin Han, and Baoyue Kuang. 2026. "Exploring the Spatial Distribution of Traditional Villages in Yunnan, China: A Geographic-Grid MGWR Approach" Buildings 16, no. 2: 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020295

APA StyleYin, X., Hou, S., Han, X., & Kuang, B. (2026). Exploring the Spatial Distribution of Traditional Villages in Yunnan, China: A Geographic-Grid MGWR Approach. Buildings, 16(2), 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020295