Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.G.-M. and C.K.; methodology, D.G.-M. and C.K.; software, D.G.-M. and C.K.; validation, D.G.-M., C.K., M.D. and S.H.; formal analysis, D.G.-M., C.K., M.D. and S.H.; investigation, D.G.-M. and C.K.; resources, D.G.-M., C.K. and J.W.; data curation, D.G.-M., C.K., M.D. and J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, D.G.-M. and C.K.; writing—review and editing, D.G.-M., C.K., M.D., S.H., J.W. and R.P.; visualization, D.G.-M. and C.K.; supervision, J.W. and R.P.; project administration, D.G.-M. and J.W.; funding acquisition, D.G.-M., J.W. and R.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Person participating in study under the artificial sky: (a) view into the sky dome hemisphere with glare source at 0° azimuth, 40° elevation; (b) view of schematic design with artificial sun, viewpoint, and direction; (c) close-up with chin-headrest (tilted 10° from normal); (d) side view of schematic design.

Figure 1.

Person participating in study under the artificial sky: (a) view into the sky dome hemisphere with glare source at 0° azimuth, 40° elevation; (b) view of schematic design with artificial sun, viewpoint, and direction; (c) close-up with chin-headrest (tilted 10° from normal); (d) side view of schematic design.

Figure 2.

Glare source positions, sizes, and luminance values for main glare situations SIT01–SIT12.

Figure 2.

Glare source positions, sizes, and luminance values for main glare situations SIT01–SIT12.

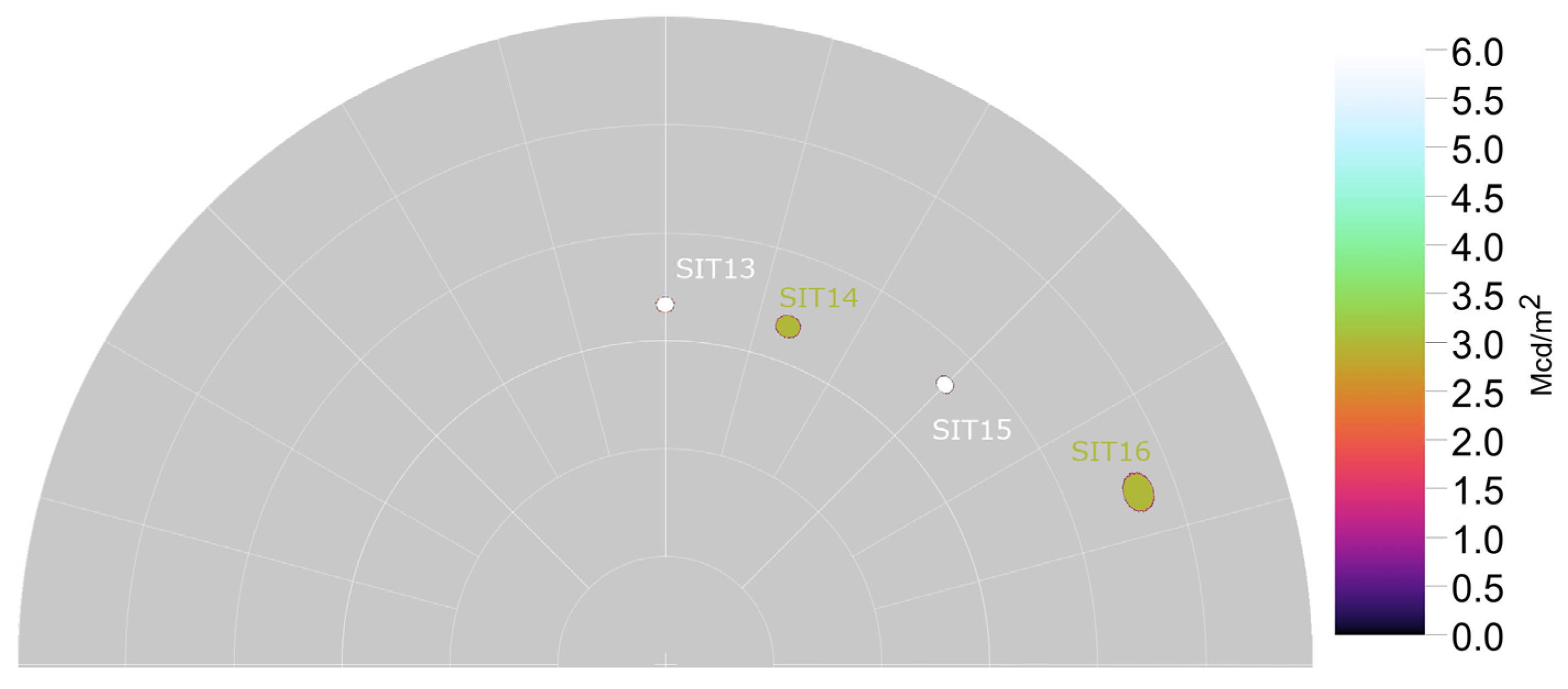

Figure 3.

Glare source positions, sizes, and luminance values for additional, high-glare situations SIT13–SIT16.

Figure 3.

Glare source positions, sizes, and luminance values for additional, high-glare situations SIT13–SIT16.

Figure 4.

Three-dimensional model used for the annual daylight simulations: (a) perspective view, (b) floor plan.

Figure 4.

Three-dimensional model used for the annual daylight simulations: (a) perspective view, (b) floor plan.

Figure 5.

Location and view from viewpoint 1. This view represents a typical view at the workplace next to the wall with view direction parallel to the façade for a sitting person (view height = 1.20 m): (a) location of viewpoint 1 in the room floor plan; (b) view with solar paths for location Stockholm; (c) view with solar paths for location Stuttgart; (d) view with solar paths for location Rome.

Figure 5.

Location and view from viewpoint 1. This view represents a typical view at the workplace next to the wall with view direction parallel to the façade for a sitting person (view height = 1.20 m): (a) location of viewpoint 1 in the room floor plan; (b) view with solar paths for location Stockholm; (c) view with solar paths for location Stuttgart; (d) view with solar paths for location Rome.

Figure 6.

Location and view from viewpoint 2. This view represents a typical view at the workplace in the middle of the room with view direction parallel to the façade for a sitting person (view height = 1.20 m): (a) location of viewpoint 2 in the room floor plan; (b) view with solar paths for location Stockholm; (c) view with solar paths for location Stuttgart; (d) view with solar paths for location Rome.

Figure 6.

Location and view from viewpoint 2. This view represents a typical view at the workplace in the middle of the room with view direction parallel to the façade for a sitting person (view height = 1.20 m): (a) location of viewpoint 2 in the room floor plan; (b) view with solar paths for location Stockholm; (c) view with solar paths for location Stuttgart; (d) view with solar paths for location Rome.

Figure 7.

Location and view from viewpoint 3. This view represents a view from the workplace in the middle of the room with view direction perpendicular to the façade for a sitting person (view height = 1.20 m): (a) location of viewpoint 3 in the room floor plan; (b) view with solar paths for location Stockholm; (c) view with solar paths for location Stuttgart; (d) view with solar paths for location Rome.

Figure 7.

Location and view from viewpoint 3. This view represents a view from the workplace in the middle of the room with view direction perpendicular to the façade for a sitting person (view height = 1.20 m): (a) location of viewpoint 3 in the room floor plan; (b) view with solar paths for location Stockholm; (c) view with solar paths for location Stuttgart; (d) view with solar paths for location Rome.

Figure 8.

Distribution of self-reported sensitivity to bright light (11-point Likert Scale).

Figure 8.

Distribution of self-reported sensitivity to bright light (11-point Likert Scale).

Figure 9.

High-glare situation SIT14 compared to reference glare situation SIT13.

Figure 9.

High-glare situation SIT14 compared to reference glare situation SIT13.

Figure 10.

Situations where the subjects’ assessment contradicts the DGP evaluations: (a) SIT02 causing significantly higher glare than SIT01, while DGP predicts the opposite; (b) DGP predicts higher glare for SIT04 than for SIT03, while user assessments show no significant difference in perceived glare.

Figure 10.

Situations where the subjects’ assessment contradicts the DGP evaluations: (a) SIT02 causing significantly higher glare than SIT01, while DGP predicts the opposite; (b) DGP predicts higher glare for SIT04 than for SIT03, while user assessments show no significant difference in perceived glare.

Figure 11.

Situation where the subjects’ assessment contradicts the DGP evaluations: DGP predicts higher glare for SIT06 than for SIT05, while user assessments show lower mean and median values even if this result is not significant.

Figure 11.

Situation where the subjects’ assessment contradicts the DGP evaluations: DGP predicts higher glare for SIT06 than for SIT05, while user assessments show lower mean and median values even if this result is not significant.

Figure 12.

Situations where the subjects’ assessment matches the DGP and DGM evaluations: (a) slightly higher glare reported for SIT08 compared to SIT05 (not significant); (b) higher glare reported for SIT08 compared to SIT06.

Figure 12.

Situations where the subjects’ assessment matches the DGP and DGM evaluations: (a) slightly higher glare reported for SIT08 compared to SIT05 (not significant); (b) higher glare reported for SIT08 compared to SIT06.

Figure 13.

Histograms showing responses to question Q4 comparing SIT09 with the situations SIT10, SIT11, SIT12, and SIT16; (a) SIT09 compared to SIT10; (b) SIT09 compared to SIT11; (c) SIT09 compared to SIT12; (d) SIT09 compared to SIT16.

Figure 13.

Histograms showing responses to question Q4 comparing SIT09 with the situations SIT10, SIT11, SIT12, and SIT16; (a) SIT09 compared to SIT10; (b) SIT09 compared to SIT11; (c) SIT09 compared to SIT12; (d) SIT09 compared to SIT16.

Figure 14.

Results for two high-glare situations: (a) subjects’ assessments follow the tendency predicted by the DGP (no significant difference); (b) glare metrics predict similar glare for SIT15 and SIT16, while test subjects report significantly higher glare for SIT16.

Figure 14.

Results for two high-glare situations: (a) subjects’ assessments follow the tendency predicted by the DGP (no significant difference); (b) glare metrics predict similar glare for SIT15 and SIT16, while test subjects report significantly higher glare for SIT16.

Figure 15.

Results including all three viewpoints and all 17 window systems, subdivided by location: (a) Stockholm; (b) Stuttgart; (c) Rome.

Figure 15.

Results including all three viewpoints and all 17 window systems, subdivided by location: (a) Stockholm; (b) Stuttgart; (c) Rome.

Figure 16.

Results including all three locations and 17 window systems, subdivided by viewpoint: (a) View 1; (b) View 2; (c) View 3.

Figure 16.

Results including all three locations and 17 window systems, subdivided by viewpoint: (a) View 1; (b) View 2; (c) View 3.

Figure 17.

Selected results including all three locations and three viewpoints, subdivided by window system: (a) EC window, τn-n = 0.02; (b) EC window, τn-n = 0.27; (c) Fabric MS1112, OF 1%, τn-h = 0.010; (d) Fabric MS1901, OF 5%, τn-h = 0.052.

Figure 17.

Selected results including all three locations and three viewpoints, subdivided by window system: (a) EC window, τn-n = 0.02; (b) EC window, τn-n = 0.27; (c) Fabric MS1112, OF 1%, τn-h = 0.010; (d) Fabric MS1901, OF 5%, τn-h = 0.052.

Figure 18.

Mean DGP values and mean value of differences from DGP for modified metrics: (a) mean DGP for all system/location/view combinations; (b) mean difference for DGP* (with blur); (c) mean difference for DGM; (d) mean difference for DGMexp1; (e) mean difference for DGMexp2; (f) mean difference for DGMugr.

Figure 18.

Mean DGP values and mean value of differences from DGP for modified metrics: (a) mean DGP for all system/location/view combinations; (b) mean difference for DGP* (with blur); (c) mean difference for DGM; (d) mean difference for DGMexp1; (e) mean difference for DGMexp2; (f) mean difference for DGMugr.

Figure 19.

Median DGP values and median value of differences from DGP value for modified metrics: (a) median DGP for all system/location/view combinations; (b) median difference for DGP* (with blur); (c) median difference for DGM; (d) median difference for DGMexp1; (e) median difference for DGMexp2; (f) median difference for DGMugr.

Figure 19.

Median DGP values and median value of differences from DGP value for modified metrics: (a) median DGP for all system/location/view combinations; (b) median difference for DGP* (with blur); (c) median difference for DGM; (d) median difference for DGMexp1; (e) median difference for DGMexp2; (f) median difference for DGMugr.

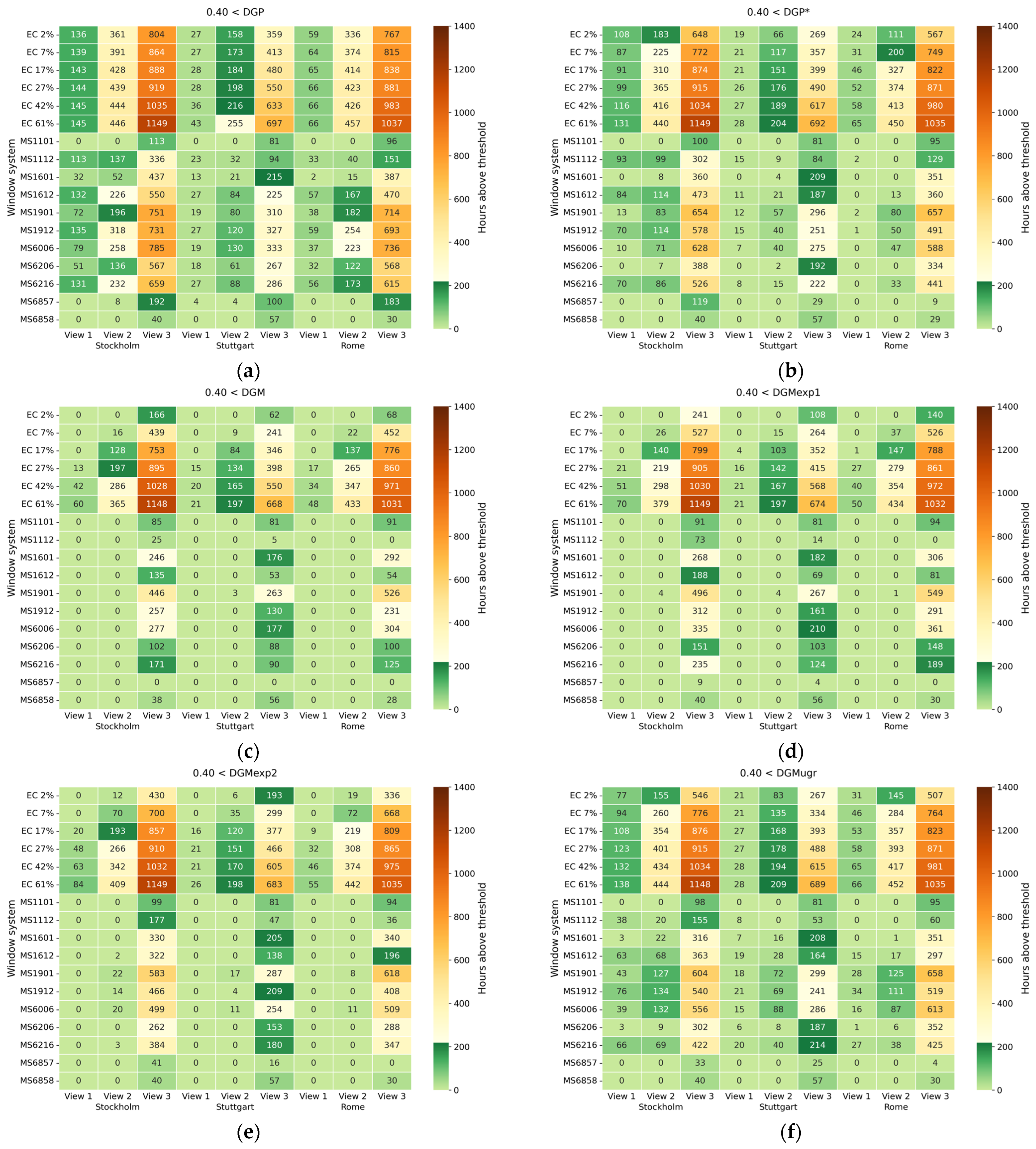

Figure 20.

Number of hours where the respective metric exceeds the threshold of 0.40: (a) DGP; (b) DGP* (with blur); (c) DGM; (d) DGMexp1; (e) DGMexp2; (f) DGMugr.

Figure 20.

Number of hours where the respective metric exceeds the threshold of 0.40: (a) DGP; (b) DGP* (with blur); (c) DGM; (d) DGMexp1; (e) DGMexp2; (f) DGMugr.

Table 1.

Categorization of DGP levels according to EN 17037.

Table 1.

Categorization of DGP levels according to EN 17037.

| Criterion | Categorization EN 17037 |

|---|

| Glare is mostly not perceived | DGP ≤ 0.35 |

| Glare is perceived but mostly not disturbing | 0.35 < DGP ≤ 0.40 |

| Glare is perceived and often disturbing | 0.40 < DGP ≤ 0.45 |

| Glare is perceived and mostly intolerable | 0.45 < DGP |

Table 2.

Glare source (GS) situations evaluated in the laboratory study; the reference situation SIT13 is marked as gray, the “low-glare” situation SIT07 is marked as light green, the “high-glare” situations SIT14 to SIT16 are marked as light red; the color coding of the values is scaled for each column (green is the lowest DGP/DGM rating, red is the highest rating; influencing factors in order of importance: green for low L/large opening angle/low Ev, red for high L/small opening angle/high Ev).

Table 2.

Glare source (GS) situations evaluated in the laboratory study; the reference situation SIT13 is marked as gray, the “low-glare” situation SIT07 is marked as light green, the “high-glare” situations SIT14 to SIT16 are marked as light red; the color coding of the values is scaled for each column (green is the lowest DGP/DGM rating, red is the highest rating; influencing factors in order of importance: green for low L/large opening angle/low Ev, red for high L/small opening angle/high Ev).

| Situation | Azimuth GS [°] | Elevation GS [°] | L [kcd/m2] | Opening Angle [°] | Ev [lx] | DGP | DGM |

|---|

| SIT01 | 0 | 40 | 3000 | 1.05 | 3418 | 0.535 | 0.468 |

| SIT02 | 0 | 40 | 375 | 2.96 | 3405 | 0.455 | 0.455 |

| SIT03 | 20 | 40 | 375 | 3.00 | 3328 | 0.451 | 0.451 |

| SIT04 | 20 | 40 | 3000 | 1.06 | 3340 | 0.531 | 0.456 |

| SIT05 | 45 | 35 | 1500 | 1.50 | 2866 | 0.470 | 0.402 |

| SIT06 | 45 | 35 | 3000 | 1.06 | 2873 | 0.498 | 0.403 |

| SIT07 | 45 | 30 | 750 | 1.47 | 1955 | 0.406 | 0.350 |

| SIT08 | 45 | 30 | 3000 | 1.04 | 2918 | 0.515 | 0.429 |

| SIT09 | 70 | 20 | 750 | 2.89 | 2931 | 0.448 | 0.404 |

| SIT10 | 70 | 20 | 1500 | 2.05 | 2940 | 0.475 | 0.405 |

| SIT11 | 70 | 20 | 3000 | 1.45 | 2934 | 0.501 | 0.404 |

| SIT12 | 70 | 20 | 6000 | 1.03 | 2941 | 0.529 | 0.405 |

| SIT13 | 0 | 40 | 6000 | 1.05 | 5836 | 0.692 | 0.624 |

| SIT14 | 20 | 40 | 3000 | 1.50 | 5663 | 0.656 | 0.607 |

| SIT15 | 45 | 35 | 6000 | 1.06 | 4747 | 0.625 | 0.528 |

| SIT16 | 70 | 20 | 3000 | 2.05 | 4879 | 0.606 | 0.533 |

Table 3.

Information about the locations used for the simulation study: EPW weather data file, latitude, number of “sun hours” with non-zero direct normal irradiance in the EPW file, and number of sunshine hours according to WMO (direct normal irradiance ≥ 120 W/m2).

Table 3.

Information about the locations used for the simulation study: EPW weather data file, latitude, number of “sun hours” with non-zero direct normal irradiance in the EPW file, and number of sunshine hours according to WMO (direct normal irradiance ≥ 120 W/m2).

| Location | Weather Data | Latitude | EPW Sun Hours | WMO Sunshine Hours |

|---|

| Stockholm | SWE_STOCKHOLM-BROMMA_024640_IW2.epw | 59.37° N | 4599 | 2726 |

| Stuttgart | DEU_Stuttgart.107380_IWEC.epw | 48.68° N | 3005 | 1605 |

| Rome | ITA_ROMA-FIUMICINO_162420_IW2.epw | 41.80° N | 4651 | 3424 |

Table 4.

Number of hours with direct radiation reported in weather file and sun seen from view positions 1, 2, and 3.

Table 4.

Number of hours with direct radiation reported in weather file and sun seen from view positions 1, 2, and 3.

| Location | View 1 | View 2 | View 3 |

|---|

| Stockholm | 421 | 740 | 1354 |

| Stuttgart | 227 | 468 | 849 |

| Rome | 250 | 668 | 1119 |

Table 5.

Glare metrics with parameters and description as used for the evaluation of the simulated images.

Table 5.

Glare metrics with parameters and description as used for the evaluation of the simulated images.

| Metric | Parameter for Equation (2) | Description |

|---|

| DGP | – | Metric as in [5] |

| DGP* | – | Blur filter as in [24] |

| DGM | scalethreshold = 2.346 | Metric as in [16] |

| DGMexp1 | scalethreshold = 1.780 | Matching experiment 1 in [16] |

| DGMexp2 | scalethreshold = 1.0 | Matching experiment 2 in [16] |

| DGMugr | ωi* = 0.0003 sr | UGR threshold for minimum solid angle |

Table 6.

Glare ratings and mean values of subjects’ responses to questions Q1 to Q7; color coding scaled for each column (green denotes the lowest ratings in the column, while red denotes the highest ratings in the column; Q6 not color-coded because the previous question was always different).

Table 6.

Glare ratings and mean values of subjects’ responses to questions Q1 to Q7; color coding scaled for each column (green denotes the lowest ratings in the column, while red denotes the highest ratings in the column; Q6 not color-coded because the previous question was always different).

| Situation | DGP | DGM | Q1 Av | Q2 Av | Q3 Av | Q4 Av | Q5 Av | Q6 Av | Q7 Av |

|---|

| SIT01 | 0.535 | 0.468 | 1.97 | 0.11 | 1.31 | 1.91 | 3.43 | 1.80 | 1.17 |

| SIT02 | 0.455 | 0.455 | 2.17 | 0.34 | 1.57 | 3.00 | 3.11 | 2.29 | 1.31 |

| SIT03 | 0.451 | 0.451 | 2.03 | 0.23 | 1.43 | 2.44 | 3.26 | 1.89 | 1.23 |

| SIT04 | 0.531 | 0.456 | 1.94 | 0.26 | 1.51 | 1.97 | 3.34 | 1.74 | 1.23 |

| SIT05 | 0.470 | 0.402 | 1.86 | 0.23 | 1.37 | 2.40 | 3.37 | 1.91 | 1.17 |

| SIT06 | 0.498 | 0.403 | 1.97 | 0.14 | 1.34 | 2.17 | 3.60 | 1.83 | 1.06 |

| SIT07 | 0.406 | 0.350 | 1.89 | 0.20 | 1.37 | 1.82 | 3.51 | 1.46 | 1.14 |

| SIT08 | 0.515 | 0.429 | 2.20 | 0.31 | 1.63 | 2.69 | 3.17 | 2.29 | 1.23 |

| SIT09 | 0.448 | 0.404 | 2.24 | 0.21 | 1.47 | 3.00 | 3.21 | 2.24 | 1.15 |

| SIT10 | 0.475 | 0.405 | 2.41 | 0.29 | 1.50 | 3.30 | 2.91 | 1.79 | 1.29 |

| SIT11 | 0.501 | 0.404 | 2.34 | 0.34 | 1.54 | 2.97 | 2.89 | 2.20 | 1.34 |

| SIT12 | 0.529 | 0.405 | 2.40 | 0.23 | 1.57 | 3.00 | 2.89 | 2.06 | 1.23 |

| SIT13 | 0.692 | 0.624 | 1.89 | 0.14 | 1.37 | 1.38 | 3.60 | − | 1.03 |

| SIT14 | 0.656 | 0.607 | 2.49 | 0.29 | 1.80 | 3.89 | 2.74 | 2.69 | 1.26 |

| SIT15 | 0.625 | 0.528 | 2.34 | 0.37 | 1.71 | 3.34 | 2.91 | 2.63 | 1.34 |

| SIT16 | 0.606 | 0.533 | 2.71 | 0.49 | 1.80 | 4.77 | 2.46 | 2.80 | 1.46 |

Table 7.

Glare ratings and median values of subjects’ responses to questions Q1 to Q7; color coding scaled for each column (green denotes the lowest rating in the column, while red denotes the highest rating in the column; Q6 not color-coded because the previous question was always different).

Table 7.

Glare ratings and median values of subjects’ responses to questions Q1 to Q7; color coding scaled for each column (green denotes the lowest rating in the column, while red denotes the highest rating in the column; Q6 not color-coded because the previous question was always different).

| Situation | DGP | DGM | Q1 Med | Q2 Med | Q3 Med | Q4 Med | Q5 Med | Q6 Med | Q7 Med |

|---|

| SIT01 | 0.535 | 0.468 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| SIT02 | 0.455 | 0.455 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 |

| SIT03 | 0.451 | 0.451 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| SIT04 | 0.531 | 0.456 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| SIT05 | 0.470 | 0.402 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| SIT06 | 0.498 | 0.403 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| SIT07 | 0.406 | 0.350 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| SIT08 | 0.515 | 0.429 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 |

| SIT09 | 0.448 | 0.404 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 1.0 |

| SIT10 | 0.475 | 0.405 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| SIT11 | 0.501 | 0.404 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| SIT12 | 0.529 | 0.405 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| SIT13 | 0.692 | 0.624 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 4.0 | - | 1.0 |

| SIT14 | 0.656 | 0.607 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 |

| SIT15 | 0.625 | 0.528 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 |

| SIT16 | 0.606 | 0.533 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 |

Table 8.

Glare ratings and subjects’ responses for SIT01-04, where the azimuth of the glare source was close to the viewing direction (0° and 20°); color coding scaled for each column (green denotes the lowest rating in the column, while red denotes the highest rating in the column).

Table 8.

Glare ratings and subjects’ responses for SIT01-04, where the azimuth of the glare source was close to the viewing direction (0° and 20°); color coding scaled for each column (green denotes the lowest rating in the column, while red denotes the highest rating in the column).

| Situation | DGP | DGP* | DGM | DGM 1.78 | DGM 1.00 | Q4 Average | Q4 Median |

|---|

| SIT01 | 0.535 | 0.512 | 0.468 | 0.488 | 0.533 | 1.909 | 2.0 |

| SIT02 | 0.455 | 0.451 | 0.455 | 0.455 | 0.455 | 3.000 | 3.0 |

| SIT03 | 0.451 | 0.447 | 0.451 | 0.451 | 0.451 | 2.438 | 2.5 |

| SIT04 | 0.531 | 0.508 | 0.456 | 0.476 | 0.521 | 1.969 | 2.0 |

Table 9.

Glare ratings and subjects’ responses for SIT05-08, where the azimuth of the glare source is 45° (elevation 35° and 30°); color coding scaled for each column (green denotes the lowest rating in the column, while red denotes the highest rating in the column).

Table 9.

Glare ratings and subjects’ responses for SIT05-08, where the azimuth of the glare source is 45° (elevation 35° and 30°); color coding scaled for each column (green denotes the lowest rating in the column, while red denotes the highest rating in the column).

| Situation | DGP | DGP* | DGM | DGM 1.78 | DGM 1.00 | Q4 Average | Q4 Median |

|---|

| SIT05 | 0.470 | 0.459 | 0.402 | 0.422 | 0.465 | 2.400 | 3.0 |

| SIT06 | 0.498 | 0.475 | 0.403 | 0.422 | 0.465 | 2.171 | 2.0 |

| SIT07 | 0.406 | 0.398 | 0.350 | 0.370 | 0.406 | 1.818 | 2.0 |

| SIT08 | 0.515 | 0.492 | 0.429 | 0.450 | 0.495 | 2.688 | 3.0 |

Table 10.

Glare ratings and subjects’ responses for SIT09-12 and 16, where the azimuth of the glare source is 70° and the elevation is 20°; color coding scaled for each column (green denotes the lowest rating in the column, while red denotes the highest rating in the column).

Table 10.

Glare ratings and subjects’ responses for SIT09-12 and 16, where the azimuth of the glare source is 70° and the elevation is 20°; color coding scaled for each column (green denotes the lowest rating in the column, while red denotes the highest rating in the column).

| Situation | DGP | DGP* | DGM | DGM 1.78 | DGM 1.00 | Q4 Average | Q4 Median |

|---|

| SIT09 | 0.448 | 0.443 | 0.404 | 0.423 | 0.448 | 3.000 | 3.0 |

| SIT10 | 0.475 | 0.466 | 0.405 | 0.424 | 0.467 | 3.303 | 3.0 |

| SIT11 | 0.501 | 0.484 | 0.404 | 0.423 | 0.466 | 2.967 | 3.0 |

| SIT12 | 0.529 | 0.501 | 0.405 | 0.424 | 0.467 | 3.000 | 3.0 |

| SIT16 | 0.606 | 0.592 | 0.533 | 0.554 | 0.598 | 4.771 | 5.0 |

Table 11.

Glare ratings and subjects’ responses for SIT07 and 14–16, the situations with the smallest DGP (0.4) and the largest DGP (>0.6); color coding scaled for each column (green denotes the lowest rating in the column, while red denotes the highest rating in the column).

Table 11.

Glare ratings and subjects’ responses for SIT07 and 14–16, the situations with the smallest DGP (0.4) and the largest DGP (>0.6); color coding scaled for each column (green denotes the lowest rating in the column, while red denotes the highest rating in the column).

| Situation | DGP | DGP* | DGM | DGM 1.78 | DGM 1.00 | Q4 Average | Q4 Median |

|---|

| SIT07 | 0.406 | 0.398 | 0.350 | 0.370 | 0.406 | 1.818 | 2.0 |

| SIT14 | 0.656 | 0.639 | 0.607 | 0.628 | 0.656 | 3.886 | 4.0 |

| SIT15 | 0.625 | 0.595 | 0.528 | 0.549 | 0.593 | 3.343 | 3.0 |

| SIT16 | 0.606 | 0.592 | 0.533 | 0.554 | 0.598 | 4.771 | 5.0 |