1. Introduction

Informal settlements are a global phenomenon, with an estimated 25% of the world’s population, approximately 1 billion people, living in various types of these communities [

1,

2]. Urban villages, often referred to as informal settlements, are a ubiquitous feature in rapidly industrializing and urbanizing regions worldwide [

3]. These settlements have evolved from rural communities that have been engulfed by expanding cities, resulting in a mix of traditional and modern architecture. Urban villages are characterized by high population density, substandard living conditions, and a lack of adequate infrastructure and services [

4,

5]. While previous studies claim that most residents in urban villages are not poor, the population in urban villages is diverse, often comprising rural migrants, migrant workers [

6,

7], and new-graduate young people.

Undoubtably, the living environment plays a significant role in shaping public health [

8]. However, living quality in urban villages is often criticized by the media and scholars [

9,

10]. The environment in urban villages presents several disadvantages that can negatively impact residents’ health. Poor infrastructure, inadequate healthcare services, and lack of green spaces contribute to a stressful living environment [

4,

11]. These conditions can lead to chronic stress, respiratory problems, and other health complications, particularly affecting the most vulnerable populations, including the elderly [

12,

13,

14]. They tend to spend more time within their immediate neighborhoods and may be more sensitive to environmental stressors and walking-related safety challenges in dense and complex streetscapes [

15,

16]. Understanding how micro-scale built-environment conditions affect older adults’ stress during everyday walking is therefore important for evidence-based, age-friendly renewal in high-density settlements.

A large body of research has examined environmental stressors in urban settings, including noise pollution and other exposures, and has linked built-environment characteristics to both psychological and physiological responses [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Evidence also suggests that exposure to natural environments and greenery can support stress reduction and recovery from mental fatigue [

22,

23,

24], whereas environments dominated by dense built forms and limited natural elements may increase stress and anxiety [

15,

19,

25]. However, in high-density urban villages where street-level scenes are visually dynamic and rapidly changing, it remains challenging to quantify visual exposure at fine spatial and temporal resolutions and to interpret how specific micro-scale visual elements contribute to older adults’ physiological stress during everyday walking.

To better address this challenge, prior work can be broadly grouped into two partially overlapping but complementary pathways. On the one hand, pedestrian-experience studies using eye tracking and visual simulation (often paired with explicit ratings) have established that visual attention and conscious appraisal differ systematically between “friendly” and “unfriendly” street environments [

26,

27]. On the other hand, neuroarchitecture and environmental neuroscience emphasize objective measurements (e.g., HRV, EDA) to capture responses that may not be fully accessible through self-report, yet many protocols rely on laboratory exposure or do not operationalize fine-grained street-level visual composition in situ.

Given the limitations of self-reported measures among the elderly and the role of EDA in capturing implicit stress and emotional arousal during actual walking, this study integrates wearable EDA measurements with semantic segmentation technology to quantify the impact of visual exposure on walking stress in the elderly. Furthermore, a CatBoost model combined with SHAP-based interpretability methods identifies key visual elements and their non-linear contributions to physiological stress during walking. Accordingly, the objectives are: (1) to measure older adults’ SCL responses along walking routes in urban villages; (2) to quantify street-level visual exposure using panoramic semantic segmentation and to derive interpretable exposure features; and (3) to model and interpret the relationships between visual exposure and stress using CatBoost (version 1.2.5) and SHAP (version 0.42.0). By these methods, we aim to identify key visual factors associated with increased or reduced stress and to provide actionable evidence for age-friendly renewal and micro-scale street interventions in high-density settlements.

2. Literature Review

The built environment, encompassing the physical structures and infrastructure of urban areas, significantly impacts physical and psychological well-being [

17]. In urban settings, environmental stressors range from traffic noise exposure [

18] to building density [

19], and they can elicit both psychological responses (e.g., perceived discomfort, anxiety) and physiological reactions (e.g., autonomic arousal). A related body of work further shows that exposure to natural environments, greenery, and open spaces can facilitate stress reduction and recovery from mental fatigue [

22,

23,

24], whereas environments dominated by dense built forms and limited natural elements are often associated with increased stress and anxiety [

15,

19,

25].

In the context of urban villages, the built environment is particularly salient. These areas are typically characterized by dense building clusters, narrow streets and alleys, limited daylight and open space, mixed traffic, and visually cluttered streetscapes. Such conditions can significantly affect the physical health of residents, especially the elderly, who may be more sensitive to environmental stressors [

16,

28]. Moreover, the elderly population in urban villages typically spends more time in their living environments, with limited mobility restricting their exposure to diverse stimulating environments. Consequently, the impact of these stressors in their living conditions becomes especially pronounced. Therefore, investigating how micro-scale street environments in urban villages influence stress responses during daily walking among older adults has become a critical component in enhancing the well-being of elderly residents.

Pedestrian-experience research assesses the “friendliness” of street environments through visual attention methods and explicit evaluations, typically incorporating scales or other scoring tools to correlate measurable visual and geometric features with perceived comfort, safety, and preference [

26,

27]. More recently, AI-enabled approaches have scaled these assessments by extracting streetscape attributes from images, enabling large-sample and fine-grained evaluation across urban contexts [

29,

30].

In parallel, to quantify human responses to built settings, neuroarchitecture and environmental neuroscience increasingly adopt multimodal measurement frameworks [

31]. These studies combine physiological and behavioral signals to capture arousal, attention, stress-related responses, and restorative effects under exposure to urban scenes, such as electrodermal activity (EDA), heart-rate variability (HRV), and electroencephalography (EEG). Among these, physiological stress can be indexed through multiple objective signals, including HRV and EDA-based measures, which reflect autonomic nervous system activity and can be continuously recorded during everyday activities. For elderly participants, it proves more effective than subjective reports, and field experiments incorporating wearable sensing technology can yield higher ecological validity. For instance, Torku et al. successfully detected stress-related responses in elderly pedestrians using wrist-worn sensors and data mining methods, demonstrating the broad potential of field-based physiological monitoring technologies for age-sensitive environmental assessments [

32]. Among wearable-friendly indicators, EDA is widely used in built-environment research because it provides high-temporal-resolution tracking of autonomic arousal. Prior studies have linked EDA dynamics to visually and physically stressful conditions, including dense built settings and degraded infrastructures [

19,

33,

34,

35,

36].

At the same time, because exposure features and human responses often exhibit non-linear relationships and context dependence, it is important to employ analytical approaches that can capture complex patterns while remaining interpretable for design and planning. Although traditional regression models have good interpretability, they are insufficient in capturing relationships other than linear relationships. More advanced machine learning models are usually black boxes; that is, they cannot explain the relationship between dependent variables and independent variables. Therefore, in the topic of the impact of the built environment on physiological stress, it is necessary to explore the interpretability of advanced machine learning models to further clarify the specific mechanism of action of built environment elements on physiological stress.

CatBoost is a gradient boosting decision tree algorithm. Compared with linear or single-model approaches, CatBoost can automatically capture non-linear effects and high-order feature interactions among predictors, and it typically requires limited feature preprocessing [

37]. However, as with many ensemble models, the learned decision rules are not directly interpretable from coefficients. To address this, we integrate SHAP, a game-theoretic explanation framework that attributes a model’s prediction to individual features in a consistent and locally accurate manner [

38]. Using TreeSHAP—an efficient implementation for tree-based models—SHAP provides both global interpretability (overall feature importance and dominant predictors) and local interpretability (case-by-case explanations), and can further quantify non-linear response patterns and interaction effects via dependence and interaction plots [

39]. Therefore, the CatBoost–SHAP combination enables us to jointly achieve strong predictive performance and transparent interpretation, allowing the study to identify which streetscape visual elements most strongly contribute to older adults’ physiological stress and how these effects vary across exposure ranges and contexts.

3. Methodology

This study comprises four main steps. Firstly, a walking experiment involving older adults was carried out in a specific high-density urban residential area, and the physiological stress data of the elderly were collected by using skin conductance technology. Secondly, capture street view videos of the same field of view along the walking route, extract image frames, and calculate the proportional parameters of various spatial elements within these frames to represent the walking environment perceived by participants during the walking experiment. Then, the Catboost machine learning algorithm was employed to develop a data model that illustrates the impact of the urban village’s spatial environment on the physiological stress experienced by older adults. Finally, the SHAP tool was utilized to parse the data model. The framework of this study is as follows (

Figure 1).

3.1. Study Area

Guangzhou, a significant city in southern China, has undergone rapid urbanization, particularly characterized by the emergence of urban villages. These areas, initially rural, have been engulfed by urban expansion, resulting in small villages that, while offering low-cost housing, often lack formal planning and essential infrastructure. Concurrently, the elderly population in Guangzhou is on the rise, presenting distinct requirements for a supportive community environment, which is crucial for enhancing the quality of life for older residents.

Xiaoguwei Island, situated in the northern part of Panyu District, Guangzhou, encompasses four typical urban villages. This study focuses on two representative urban villages on the island, characterized by the largest populations of elderly residents, as well as complex spatial environments. The first site, Beiting Village, boasts the only large-scale commercial center on the island. Furthermore, its attractive environment, convenient transportation, and numerous public squares draw many elderly residents who engage in relaxation, exercise, and walking. The second site, Nanting Village, offers a unique artistic atmosphere while featuring a narrower pedestrian pathway system compared to Beiting Village. The initial segment of the Beiting Village route features beautiful natural landscapes, while the latter segment transitions into a high-density urban village environment characterized by gradually increasing housing densities. Conversely, the first segment of the Nanting Village route presents an urban village living environment. The second segment reveals a natural environment that offers a gradually wider view and more beautiful surroundings. The walking route to Beiting Village is 1.2 km, and that to Nanting Village is 0.9 km.

Prior to the experiment, researchers established 98 sampling points along the Beiting Village experimental route, maintaining an average interval of 12 m between each point, and 94 sampling points along the Nanting Village experimental route, with an average interval of 8 m between each point. Each point possesses distinct characteristics, and adjacent points exhibit clear differences. During the experiment, the recorder logged the timestamps using a mobile phone as subjects passed each point. After the experiment, these timestamps were verified through the experimental video recordings. The timestamps represent the subject’s location information along the entire walking route.

3.2. Experiment Design

3.2.1. Subjects

This study identified the elderly aged 55 to 75 as the target research subjects and recruited participants through street recruitment. Seniors meeting the age criteria, capable of independent walking, in good physical condition, and without any recent serious accidents were recruited for the experiment. A total of 81 subjects participated in the experiment, comprising 35 males and 46 females, with a mean age of 58 years. All subjects signed the informed consent and received a participation fee of 100 RMB upon completion of the experiment. Specifically, a total of 37 subjects were assigned to the Beiting Village route and 44 subjects to the Nanting Village route. However, due to a malfunction in the experimental equipment, 6 subjects withdrew from the study during the process.

3.2.2. Experimental Period

The experiment was conducted during off-peak hours in spring (10:00 a.m.–12:00 p.m. and 2:00 p.m.–4:00 p.m.) to mitigate interference from summer heat, high humidity, and traffic congestion on experimental results. The data collection period encompassed weekends to ensure a more comprehensive dataset. In the event of adverse weather conditions, such as heavy rain, the experiment will be modified or canceled as necessary to maintain the safety and accuracy of data collection.

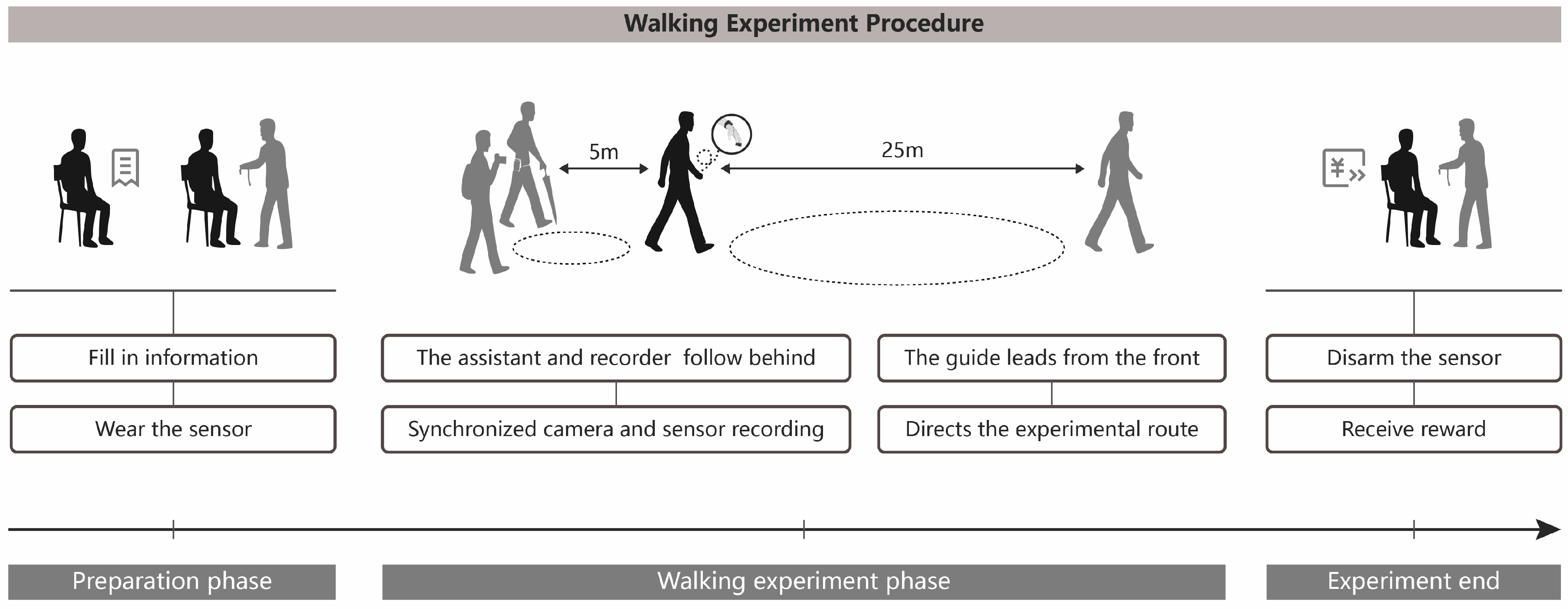

3.2.3. Experimental Procedure

The day prior to commencing the walking experiment, subjects were informed by researchers on precautions, including the requirement not to participate on an empty stomach. Upon arrival at the experimental site on the day of the experiment, subjects completed the experimental notice and informed consent. Subsequently, the ErgoLAB EDA wireless electrodermal activity sensor (Kingfar, Beijing, China) was attached to the subjects’ fingers.

Five minutes prior to the commencement of the experiment, subjects were instructed to remain seated in a chair while completing a personal information questionnaire. Each experiment was limited to one subject. Researchers provided a guide, an assistant, and a recorder to assist the subjects during the experiment. At the outset of the experiment, the guide delineated the walking route to the subjects. The assistant carried a device for receiving physiological data and an umbrella, while the experimental recorder operated a camera to document the subjects’ walking and the timing of their passage at designated experimental points. The assistant and recorder synchronized the start of the experiment by activating the equipment together. In order to minimize disruptions to the subjects’ observation of the urban village environment and to mitigate any undue physiological stress, the guide maintained a distance of 25 m ahead of the subjects, with the assistant and recorder positioned 5 m behind them. Subjects were instructed to limit conversations with others during the walking process to prevent the emergence of extraneous emotions and stress. Upon completion of the experimental route by the subjects and reaching the designated endpoint, the assistant and recorder collaboratively deactivated the data receiving device and camera to synchronize the end time. Subsequently, the assistant aided the subjects in detaching the ErgoLAB EDA wireless electrodermal activity sensor. The experimental procedure is shown in

Figure 4.

3.3. Data Acquisition

3.3.1. Physiological Data

During the walking experiment, subjects wore the ErgoLAB EDA wireless electrodermal activity sensor, which captured real-time skin electrical signals as they walked along a predetermined route. These signals were consistently recorded using two clasp finger-type Ag-AgCl dry electrodes firmly secured to the middle and index fingers of the subjects’ left hand. In the research, Skin Conductance Levels (SCLs) were identified as the primary indicator. This measure evaluates sweat gland activity through skin conductivity, providing a sensitive reflection of an individual’s emotional arousal and stress levels in a walking environment.

3.3.2. Environmental Data

To capture street scene videos that approximate the human eye’s field of view, researchers employed a SONY A7M3 camera (SONY Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with an EF 28–70 mm lens (Canon Inc., Tokyo, Japan), mounted on a FeiyuTech Scorp gimhead (Guangzhou Feiyu Electronic Technology Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China). The focal length was fixed at 43 mm, and the camera height was set to 168 cm to simulate the natural eye level. Researchers recorded first-person perspective street view videos along the designated experimental route and processed each video frame into independent static images. Ultimately, images were captured at average intervals of 12 m and 8 m along the Beiting Village and Nanting Village routes, respectively, totaling 948 images for Beiting Village and 605 images for Nanting Village. All extracted images were manually matched to precisely correspond with predefined sampling points along the routes.

3.4. Data Processing and Analysis

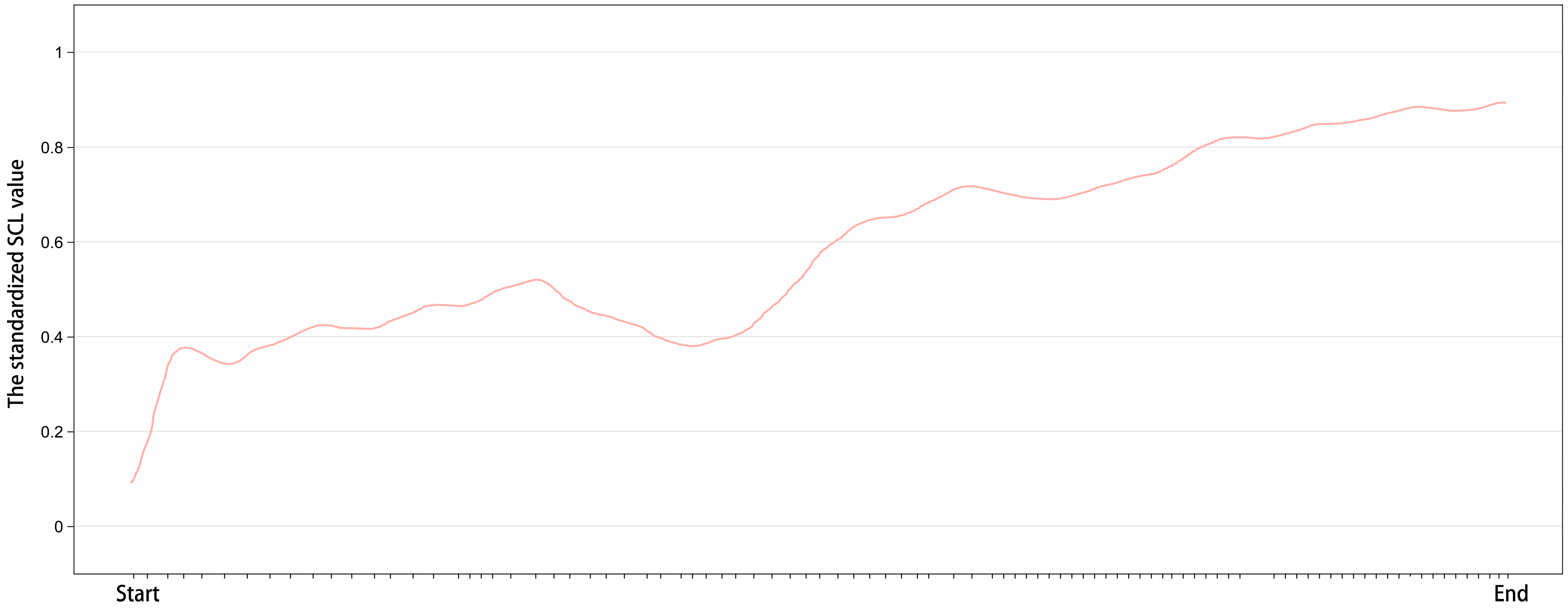

3.4.1. SCL Data Processing Method

Walking may introduce transient disturbances to EDA recordings. Because this study used SCL (tonic level) as the primary stress indicator rather than event-related phasic responses, motion-related high-frequency perturbations were mitigated mainly by the filtering strategy. During data preprocessing, the raw SCL signal was filtered to retain the physiologically meaningful tonic component while attenuating noise and drift. Specifically, we applied a low-pass filter with a cut-off frequency of 0.5 Hz to suppress high-frequency fluctuations, and a high-pass filter with a cut-off frequency of 0.05 Hz to remove very slow baseline drift and sensor offset. The ErgoLAB EDA wireless electrodermal activity sensor captures SCL data at a rate of four times per second.

Given the substantial inter-individual differences in the absolute range of SCL, we normalized the SCL time series for each participant using min–max scaling. Let

denote the raw SCL value at time

, and

and

denote the minimum and maximum SCL values observed for the same participant during the experiment. The normalized SCL value

was computed as:

This transformation maps each participant’s SCL values to the range , thereby reducing inter-individual variability and enabling comparisons across participants.

3.4.2. Analysis on Visual Exposure of the Routine

This research used Panoptic SegFormer as the semantic segmentation framework with a PVTv2-B5 backbone. The model was initialized with COCO pretrained weights (

https://github.com/zhiqi-li/Panoptic-SegFormer, accessed on 15 October 2024) and achieved a Panoptic Quality (PQ) of 54.4% on the COCO test-dev benchmark, providing a quantitative reference for segmentation performance. This model also decreased the number of parameters by approximately 34% compared to traditional single-stage methods [

40]. To balance computational efficiency and boundary integrity, the original 4K frames (3840 × 2160) were uniformly resized to 1024 × 576 pixels, reducing computational cost by approximately 60% while preserving pixel-level semantic boundaries for proportion estimation.

The segmentation output contains 133 semantic classes. To meet the analytical needs of the walking experiment and improve interpretability, we merged these classes into six broad streetscape categories: Roads, Sidewalks, Vegetation, Buildings, Sky, and Others. For each frame, the visual exposure of each category was computed as the proportion of pixels assigned to that category. Using aggregated proportions over six broad categories can reduce sensitivity to fine-grained misclassifications.

3.4.3. Time Synchronization Between Sampling Points, Visual Features, and SCL Signals

To establish a one-to-one correspondence between environmental visual exposure and physiological responses, three time series were synchronized: the time when a participant passed each predefined sampling point along the route, the time stamps associated with the semantic-segmentation outputs for the route video, and the EDA recording time series.

First, based on the route-recording video, the passing time of each participant at each sampling point was manually identified, yielding a set of time stamps . Second, the semantic-segmentation results were matched to the same sampling points . The segmentation outputs contain their own time information . Third, to align EDA samples with the sampling-point sequence, we densified the sampling-point time axis by linearly interpolating between adjacent passing times and . Specifically, nine intermediate time stamps were inserted between two neighboring sampling points, resulting in 10 time stamps per segment. For each interpolated time stamp, the EDA sample whose recording time was closest to that interpolated time was selected from the EDA series. This procedure produced aligned pairs of visual exposure features and for subsequent modeling.

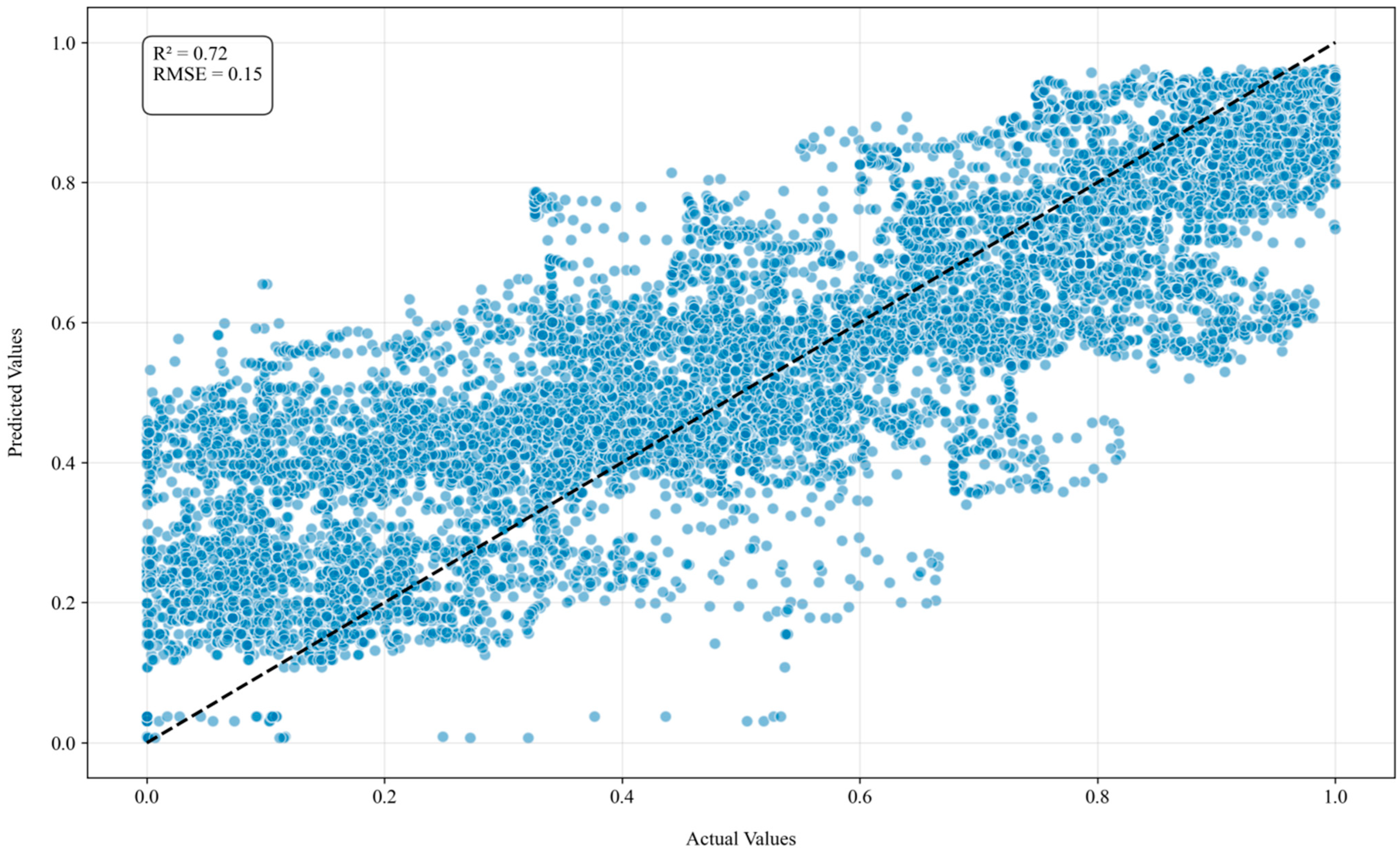

3.4.4. Ensemble Model Establishment and the Explanation Method

In this study, CatBoost gradient boosting was employed to model the relationship between streetscape visual exposure and physiological stress. Each aligned observation consisted of six visual-exposure proportions (Roads, Sidewalks, Vegetation, Buildings, Sky, and Others) as input features, and the corresponding normalized SCL value as the regression target. The CatBoost model was trained on the constructed dataset to generate stress predictions, and model performance was evaluated using standard regression metrics.

To enhance interpretability, the SHAP method is used to quantify the contributions of global and local features. Specifically, TreeSHAP—an optimized SHAP algorithm for tree-based models—was used to compute SHAP values efficiently for each observation. In this regression setting, SHAP explains each prediction as the sum of a baseline value (the expected model output) and feature-wise contributions. Therefore, a positive SHAP value indicates that a feature increases the predicted normalized SCL relative to the baseline, whereas a negative SHAP value indicates that the feature decreases the prediction. We visualized SHAP results using summary plots, and further used SHAP interaction values to explore non-linear coupling among streetscape elements.

5. Discussion

This research investigates the impact of various visual elements in the pedestrian environment of high-density urban villages on the physiological stress levels of the elderly. By monitoring physiological stress levels in elderly pedestrians across diverse environments using skin conductance sensors, continuous measurements of autonomic arousal (SCL) are provided. Micro-scale visual exposure metrics for urban village walking environments are obtained through semantic style, while the CatBoost model captures latent exposure-response nonlinear patterns from segmented street-scene imagery. Compared to eye tracking and VAS simulations emphasizing visual attention and evaluation, EDA physiological measurements capture most implicit autonomic arousal during actual walking. This is particularly relevant for the elderly, as it imposes minimal task burden and reveals stress responses potentially underreported through self-assessment.

Additionally, SHAP values explain how each visual element contributes to model predictions at varying exposure levels. The study establishes an interpretable association between micro-scale exposure and physiological stress responses during walking in high-density urban villages. The findings indicate that the relationship between the proportion of each element and stress levels is not purely linear, highlighting the intricate and context-specific nature of this relationship. Specifically, roads and sidewalks emerged as the primary factors influencing the physiological stress of the elderly, while vegetation and buildings exhibited a moderate yet significant effect. Conversely, the presence of sky and other elements showed minimal impact on stress levels.

Roads represent a critical factor influencing stress levels. Reduced road visibility is significantly correlated with a marked decrease in stress. This finding suggests that lowering road visibility in pedestrian settings emerges as an effective design approach to alleviate pedestrian stress. Strategies such as situating pedestrian zones away from roads or incorporating green spaces to create a safer separation between pedestrians and vehicles can achieve this. Conversely, sidewalks consistently serve as stress-relieving elements, signifying their role as secure and favorable environmental features. This discovery surpasses most studies relying on behavioral observation or self-reporting by elucidating its intrinsic physiological mechanism and consistently concluding that elderly individuals with diminished physical functions exhibit heightened sensitivity to fast-moving traffic and safety risks associated with physical obstacles and inadequate infrastructure maintenance [

41,

42]. The safety of the walking environment is intricately linked to physiological stress. The safety risks encountered while walking compel the elderly to engage in continual risk assessment and avoidance behaviors while walking, imposing a significant cognitive burden. Feelings of insecurity serve as direct and persistent physiological stressors, manifesting in elevated SCLs. Conversely, sidewalks serve as the fundamental safety assurance for the walking environment. This finding underscores that, in the development of age-friendly communities, the foremost priority must be to establish a safe and barrier-free walking system.

Vegetation elements generally decrease stress levels, aligning with the Stress Recovery Theory (SRT) and previous research [

43,

44,

45,

46]. However, more vegetation does not necessarily equate to better stress reduction. In contrast to a direct positive correlation [

25,

47], our study emphasizes an inverted U-shaped relationship between vegetation and stress, echoing research on the threshold effect of natural elements [

48,

49]. This research indicate that vegetation typically lowers stress, with moderate visibility yielding the most significant stress-relieving benefits. Conversely, excessively high levels of vegetation may weaken its positive impact. We posit that the attenuation of the decompression effect associated with a high green vision rate arises from the moderating influence of perceived safety. In the narrow streets of urban villages, excessively dense greenery can create a sense of visual obstruction, exacerbate the isolation of these streets and potentially generate blind spots. This situation may elevate concerns among the elderly regarding their personal safety. Torku et al. indicated that when a space is overly enclosed or too proximate to a physical boundary, the elderly experience heightened physiological stress due to claustrophobia, emphasizing their preference for open spaces with low barriers [

32]. This finding corroborates our assertion. Additionally, untrimmed and chaotic greenery may signal “unmanaged” and “dilapidated” conditions, potentially impacting the walking stress levels of elderly individuals. Consequently, the results of this research underscore that the stress-relieving effects of vegetation elements are context-dependent, suggesting that moderate vegetation may be the most effective approach. Vegetation design should prioritize “quality” factors—such as maintenance level, species composition, and spatial permeability—over merely pursuing an accumulation of “quantity,” or green vision rate.

One of the most surprising findings of this study is that buildings exhibit a stress-reducing effect in the predictive model. This finding directly challenges the traditional view that associates high-density built environments with congestion, oppression, and negative health effects. Compared with previous studies [

19], it can be found that there are some differences and commonalities in the impact of visual spatial configuration on young people and the elderly, and the results of this research show that the differences are reflected in buildings. We propose that this phenomenon may reflect the preferences of specific groups. For elderly residents in urban villages, buildings function as a form of “Social Infrastructure.” Their stress-relieving effects may arise from two key aspects. First, familiar building facades and clear street directions provide a strong sense of place and orientation, thereby reducing cognitive anxiety associated with navigating a complex road network. Second, elderly residents who have lived in these areas for an extended period may have adapted to, or even developed a preference for, the enclosed street and alley spaces, perceiving them as vibrant environments conducive to informal social interaction. Therefore, for older adults, such everyday social contact and perceived “knownness” of place may buffer stress responses, even in physically dense environments. This finding contrasts with numerous studies that regard high density as a source of stress. Importantly, this does not imply that “more building” is universally beneficial. Rather, it suggests that environmental preferences and stress responses are group- and experience-dependent, shaped by long-term residence, cultural familiarity, and age-related mobility needs. Future studies could test this adaptation hypothesis by comparing long-term residents with newcomers or visitors and by adding measures of place attachment, perceived safety, and spatial legibility, as well as by examining interaction effects.

The findings suggest that age-friendly renewal in high-density urban villages should prioritize safety infrastructure over purely aesthetic upgrades. Practically, interventions should focus on ensuring continuous and barrier-free sidewalks, reducing pedestrian–vehicle conflict, and increasing perceived separation from vehicular flow (e.g., traffic calming, edge buffers, or setbacks where feasible). At the same time, greenery should not be treated as a simple “more is better” solution: planting and greening programs should prioritize maintenance, visibility, and permeability, avoiding excessive enclosure that may create blind spots or amplify insecurity for older pedestrians. Finally, renewal strategies should recognize that existing buildings may provide valuable social and cognitive supports (familiarity, legibility, and opportunities for informal interaction). Rather than adopting a uniform “open-and-green” approach, practitioners may achieve better health outcomes by combining targeted safety improvements with design measures that preserve local identity and everyday social functioning.

The conclusions are most directly applicable to older adults walking in high-density urban villages or informal-settlement-like areas, where streets are narrow, traffic is mixed, and street-level visual scenes change rapidly over short distances. The identified non-linear patterns (e.g., the vegetation “threshold” effect) are therefore context-dependent and may differ in urban forms with wider streets, stronger pedestrian–vehicle separation, or different cultural expectations of enclosure (e.g., modern gated high-rise communities, low-density suburbs, or tourism-oriented historic districts). Cross-site replication across multiple neighborhood types and cultural settings is needed to establish broader external validity.

Finally, this research has several limitations that suggest avenues for future research. First, a limitation is potential segmentation misclassification in dense and visually complex urban-village streets. Although we used a well-established pretrained model and aggregated 133 classes into six broad categories using proportion-based features (which smooths random pixel-level errors), systematic confusions (e.g., road vs. sidewalk under occlusions) may propagate into the predictors and influence the magnitude of estimated effects and SHAP explanations. Future studies could improve robustness by fine-tuning the segmentation model on domain-specific imagery and introducing uncertainty-aware feature extraction. In addition, the semantic segmentation technology utilized here categorized the environment into broad classifications such as “vegetation” and “buildings,” overlooking nuanced differences within these groups, such as the transparency of building facades and the maintenance levels of greenery. Subsequent studies should leverage advanced computer vision techniques to uncover the specific principles underlying “beneficial buildings” and “high-quality vegetation”.

Second, while this research focused on analyzing the individual impacts of each element, in reality, these influences likely interact with each other. Future research should prioritize examining SHAP interaction effects to address the fundamental question of “under what conditions what is important.”

Third, the sample of this research concentrated on the elderly population in urban villages, making its conclusions difficult to generalize to other cultural contexts, urban settings (e.g., modern high-rise communities, historical and cultural districts), and age demographics (e.g., youth). Future comparative studies are necessary to validate the findings across diverse populations and environments.

6. Conclusions

This research quantitatively examined the influence of the built environment in high-density urban villages of Lingnan, China, on the walking physiological stress experienced by the elderly. This analysis employed an innovative framework that integrates physiological measurements, computer vision, and interpretable machine learning models. The research results provide physiological evidence that directly links visual features to the stress responses of the elderly, a susceptible population, offering new insights into the “environment–health” relationship in specific environments.

The primary conclusions are as follows. (1) Road and sidewalk exposures are the strongest predictors of stress, suggesting that walking safety conditions and pedestrian-supportive infrastructure play a more decisive role in stress regulation than purely aesthetic features. (2) Vegetation is generally associated with reduced stress but exhibits a non-linear, context-dependent effect, indicating that in narrow streetscapes, the restorative benefit may weaken when greenery increases enclosure or perceived insecurity. (3) Buildings can show an overall stress-buffering association in this context, plausibly reflecting place familiarity, spatial legibility, and informal social support functions among long-term older residents.

Empirically, the study extends micro-scale environment–health evidence to an under-studied yet globally prevalent settlement type (urban villages/informal settlements) and a vulnerable population (older adults). Methodologically, it demonstrates a replicable approach for quantifying fine-grained visual exposure and explaining non-linear exposure–stress relationships using interpretable Machine Learning. The most significant contribution of this research is its provision of evidence-based findings derived from objective physiological data, which challenges the traditional emphasis on visual aesthetic elements, such as greenery and open spaces, in urban renewal efforts. The findings encourage a reframing of renewal priorities: in high-density settlements, stress-sensitive design for aging should begin with safety-first walking infrastructure, while treating the existing dense built fabric as a potential resource that can support cognition and social life when combined with targeted safety upgrades.

For urban-village renewal and age-friendly practice, interventions should prioritize continuous, barrier-free sidewalks, reduction in pedestrian–vehicle conflict (e.g., traffic calming and buffers), and greening strategies that emphasize maintenance and visibility rather than maximum green quantity. Renewal should also avoid uniform “open-and-green” solutions and instead preserve local identity and legibility, leveraging buildings’ supportive functions while improving accessibility and safety.

Overall, the findings of this study provide an objective basis for understanding stress-relevant streetscape conditions experienced by older adults while walking in high-density urban villages. They offer design-oriented guidance for urban-village renewal and age-friendly practice, and furnish urban planners, architects, and decision-makers with quantitative evidence and actionable references for targeted micro-scale interventions. Future research could replicate this approach across diverse urban morphologies and cultural contexts, incorporate uncertainty-aware exposure features, explicitly test interaction effects among environmental elements, and combine physiological sensing with complementary perceptual measures (e.g., perceived safety and place attachment) to strengthen explanatory power and transferability. By integrating such evidence, subsequent work can help advance the creation of psychologically supportive and sustainable urban environments.