Evolutionary Game Theory in Architectural Design: Optimizing Usable Area Coefficient for Qingdao Primary Schools

Abstract

1. Introduction

- It fills the research gap in the architectural planning field regarding the multi-stakeholder game phenomenon in the determination of the UAC. For the first time, evolutionary game theory is applied to the optimization of the UAC in primary school buildings, thus expanding interdisciplinary methodologies within architectural planning.

- By constructing a government–school–student three-party evolutionary game model, the study identifies stable evolutionary strategy points and clarifies that the increment of overall benefits under low UAC and government risk compensation are key factors influencing the adoption of lower UAC in primary school buildings.

- Based on the stability conditions, the study proposes practical design strategies such as controlling construction and land-use costs and enhancing the usability of open activity spaces. These strategies not only ensure sufficient open activity spaces necessary for children’s education and learning but also balance fiscal budget constraints, thereby contributing to the creation of a healthy and comfortable educational environment.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Architectural Programming

2.2. Evolutionary Game Theory

2.3. Primary School Architecture

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

- Determination of benefit and cost parameters

- Benefits and cost parameters for each stakeholder were established through case studies and comparative policy analysis. Nine public primary schools in a district of Qingdao, characterized by floor area ratios of at least 1.9 and land compliance rates of no more than 0.5, were selected as samples. Architectural drawings and construction cost reports were collected, extracting key indicators such as total construction area, functional room areas (teaching, administrative, and logistical spaces), open activity spaces, and auxiliary circulation areas. These data formed a database correlating actual UAC with spatial configurations. Additionally, 11 national, provincial and municipal regulations were collated to extract constraint parameters, such as per-student land area, per-student building area, functional space ratios, and maximum floor area ratios. This process defined the policy-based range of UAC (e.g., provincial recommendation of UAC = 0.6). Cost parameters and investment data from the sample projects were systematically compared with corresponding standards, enabling accurate determination of government benefit parameters and costs.

- Stakeholder interests and survey data

- Two types of surveys were conducted to gather data on stakeholder interests. First, interviews were held with government officials, focusing on “UAC requirements” and the “distribution ratio of comprehensive benefits from low UAC between government and schools,” These interviews yielded 28 valid records. Second, questionnaires were distributed to schools (principals and academic staff) and students in grades 4–6, addressing “satisfaction with open spaces and spatial utilization issues” and the “distribution ratio of comprehensive benefits from low UAC between schools and students.” Out of 200 questionnaires distributed, 163 valid responses were received. Both survey instruments primarily collected quantitative data. Satisfaction and spatial utilization issues were analyzed using Likert scales, while distribution ratios were evaluated using a two-round Delphi method. This approach enabled comprehensive insight into stakeholder preferences and cost acceptance, offering robust data support for subsequent analyses and decision-making.

3.2. Data Processing

- Processing benefit and cost parametersCollected benefit and cost parameters were screened for outliers and standardized. Grubbs’ test was employed to exclude anomalous UAC (e.g., K > 0.85 or K < 0.35) arising from special policies (such as renovations of historical buildings), retaining nine valid samples for model parameter calibration. Data from primary schools of varying sizes (24, 36, and 48 classes) were converted to per-student indicators (m2/student) to eliminate interference from class-size differences. Additionally, various area types from schools of different scales were proportionally converted to eliminate project-scale disparities, using area proportion as a unified comparison dimension. Monetary and quasi-monetary data, including government subsidies, school costs, and parental expenditures, were uniformly adjusted to constant 2024 prices, removing inflationary influences and ensuring data comparability.

- Validation of stakeholder interest dataSurvey data consistency was validated using cross-analysis to examine correlations between questionnaire satisfaction ratings and actual proportions of open space, ensuring alignment between survey results and case data. A group-comparison validation strategy was employed, dividing the nine schools into three categories based on actual open space proportions: high (>10%), medium (5–10%), and low (<5%). Mean satisfaction scores across these groups were compared using ANOVA (p < 0.05). Significantly higher satisfaction scores among high-proportion schools compared to medium and low groups confirmed the congruence of survey data with case data, ensuring satisfaction ratings reliably reflected differences in spatial indicators related to UAC and preventing survey findings from diverging from actual spatial conditions.

4. Model Construction and Simulation Analysis

4.1. Model Construction

4.1.1. Stakeholder Analysis

4.1.2. Model Assumptions

4.1.3. Parameter Assumptions

4.1.4. Payoff Matrix

4.2. Model Simulation Analysis

4.2.1. Stability Analysis

- (1)

- Fundamental Derivation

- (2)

- Expected and Average Payoffs for the Government (G)

- (3)

- Expected and Average Payoffs for Schools (S)

- (4)

- Expected and Average Payoffs for Students and Parents (P)

4.2.2. Scenario Simulation

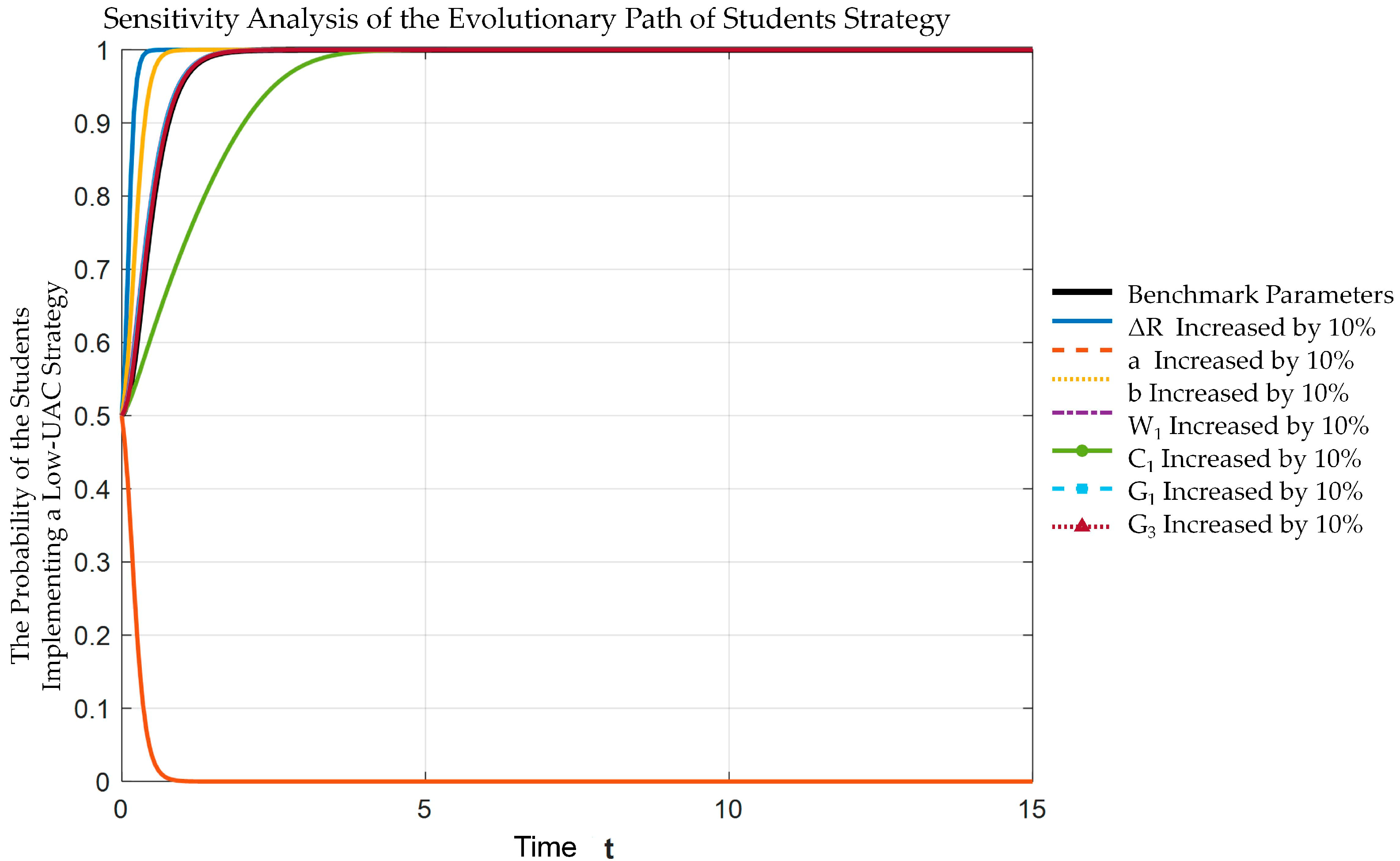

4.2.3. Sensitivity Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Practical Implications

5.2. Theoretical Significance

- Advancing UAC research within primary school architecture:

- Innovation from a multi-stakeholder dynamic equilibrium perspective:

5.3. Primary School Design Suggestions

5.4. Policy Optimization Suggestions

6. Conclusions and Limitations

- Conditions for Evolutionarily Stable Strategies: When the incremental comprehensive benefit of a low UAC (ΔR) exceeds 150,000 yuan/class and the government’s risk compensation to schools (W1) surpasses 80,000 yuan/class, the system converges with a probability of no less than 0.8 to a low UAC range (0.48–0.53). Under these conditions, the stakeholder strategy combination (E8(1,1,1)), namely, “active government implementation–schools requesting low UAC–students and parents expressing demands,” emerges as the unique evolutionarily stable strategy, enabling a synergy between intensive land use and well-being spaces.

- Key Influencing Parameters: Sensitivity analysis indicates that ΔR serves as the central driver influencing system evolution, with its increase positively aligning stakeholder strategies. The benefit-sharing coefficient a (0.6–0.7) significantly impacts the willingness of students and parents to express their demands. Additionally, when W1 ≥ 80,000 yuan/class, governmental willingness for active implementation notably increases, while school strategies demonstrate greater sensitivity to the benefit-sharing coefficient b.

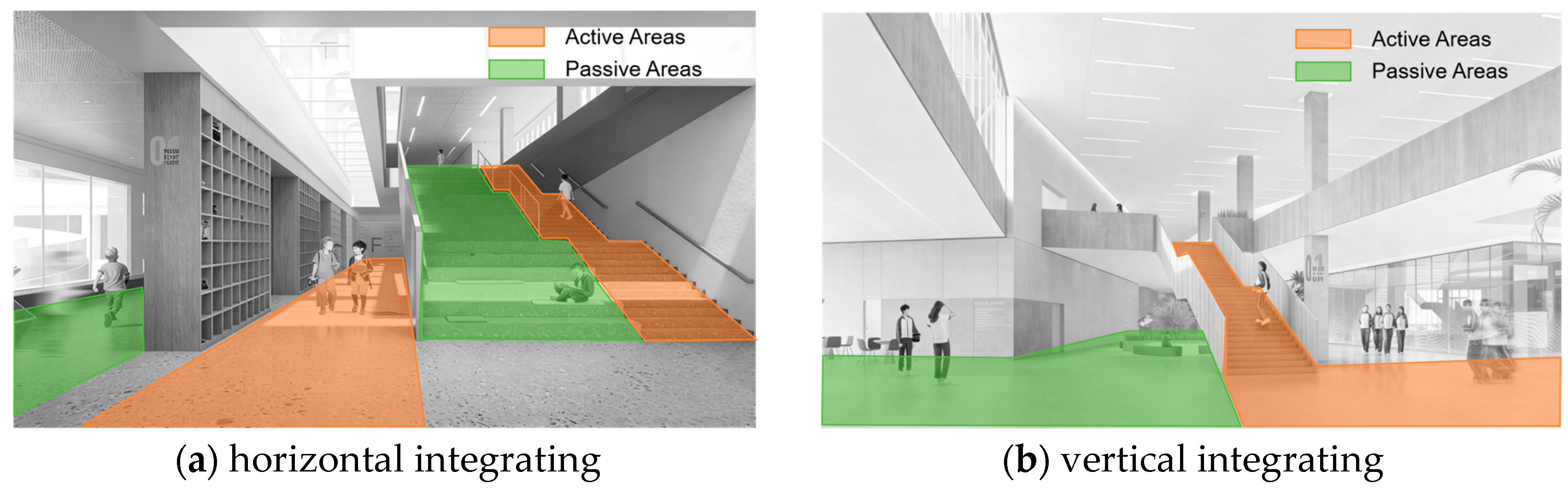

- Design Strategies: A combined strategy of centralized compact planning, functionally hybridized circulation, dynamically static zoned activity areas, and modular unit construction enables primary-school projects to achieve simultaneous gains in land efficiency, floor-area utilization, child well-being and construction quality without increasing either site area or overall cost.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UAC | Usable Area Coefficient |

| ESS | Evolutionarily Stable Strategy |

References

- Dumdie, L.B.M.; Mason, B.A.; Hajovsky, D.B.; Ethan, V.F. Student-report measure of school climate: A dimensional review. Sch. Ment. Heal. 2020, 12, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorbaz, D.; Akin-Arikan, C.; Terzi, R. Does school climate that includes students’ views deliver academic achievement? A multilevel meta-analysis. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2021, 32, 543–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duraku, H.Z.; Hoxha, L. Effects of school climate and parent support on academic performance: Implications for school reform. Int. J. Educ. Reform 2021, 30, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Liu, Q.; Wu, X. The Environmental Design for Eco Learning Camps for School Children: A Case Study of Changle, Fujian Province, China. In Towards a Carbon Neutral Future; Papadikis, K., Zhang, C., Tang, S., Liu, E., Di Sarno, L., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2024; Volume 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemet, B.M.; Velki, T. Some demographic personal and class characteristics as predictors of school climate. Educ. New Dev. 2019, 1, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Smul, M.D.; Heirweg, S.; Devos, G.; Keer, H.V. It’s not only about the teacher! A qualitative study into the role of school climate in primary schools’ implementation of self-regulated learning. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2020, 31, 381–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, R.N. Implementation of individual education program (IEP) in curriculum of students with. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Special Education in South East Asia Region 10th Series 2020, Bangi, Malaysia, 29–30 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pardamean, B. AI-based learning style prediction in online learning for primary education. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 35725–35735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layang, F.; Mahamod, Z. The level of knowledge, willingness and attitude Malay primary school teachers in teaching and learning map i-Think thoughts. Malays. J. Educ. 2019, 44, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, I.; Nielsen, L.M. Architecture in school practice: Possible tools for supporting spatial literacy. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2025, 35, 1597–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.E.; Imms, W. Flexible furniture to support inclusive education: Developing learner agency and engagement in primary school. Learn. Env. Res. 2025, 28, 223–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, I.; Patel, D.A.; Lad, V.H.; Rajesh, M.R. Development of Post Occupancy Index (POI) for High-Rise Residential Buildings. In Creating Capacity and Capability: Embracing Advanced Technologies and Innovations for Sustainable Future in Building Education and Practice; Sutrisna, M., Jelodar, M.B., Domingo, N., Le, A., Kahandawa, R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2025; Volume 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mba, E.J.; Okeke, F.O.; Oforji, P.I.; Ozigbo, I.W.; Emmanuel, E.C.; Ozigbo, C.A. Impact of Building Plan Shape on Natural Ventilation Efficiency for Thermal Comfort in Educational Facilities: A Post-occupancy Evaluation. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Civil Engineering, Singapore, 22–24 March 2024; Strauss, E., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2025; Volume 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Osaragi, T.; Ni, J.; Luo, Z.; Geng, Y.; Zhuang, W. A new space utilization assessment paradigm from the perspective of post-occupancy evaluation based on Wi-Fi and Bluetooth positioning systems. Build. Simul. 2025, 18, 2723–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.W.; Yoo, H.Y. Research on the Pre-planning Process for School Space Innovation Project for Operation of High School Credit System. In Proceedings of the 4th International Civil Engineering and Architecture Conference, Seoul, South Korea, 14–17 March 2024; Casini, M., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2025; Volume 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Ratavjia, S.; Rattadilok, P. Implementing a Participatory Design Approach to Create a Sensory-Friendly Public Space for Children with Special Needs. In Innovative Public Participation Practices for Sustainable Urban Regeneration; Mangi, E., Chen, W., Heath, T., Cheshmehzangi, A., Eds.; Urban Sustainability; Springer: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowaltowski, D.C.C.K.; Gonçalves, P.P.; Cleveland, B. Better school architecture through design patterns. Learn. Environ. Res. 2024, 27, 619–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.H. Compact design concept as an alternative for adapting school buildings to small plots in slums and unplanned urban areas. Eng. Res. J. 2023, 52, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Z. Optimal study based on measuring the K value of holistic classroom building group on the college campus. J. Xi’an Univ. Archit. Technol. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2011, 43, 576–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordass, B.; Leaman, A. Making feedback and post-occupancy evaluation routine1: A portfolio of feedback techniques. Build. Res. Inf. 2005, 33, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Shen, Q.; Xiaoling, Z. A user preoccupancy evaluation method for facilitating the designer-client communication. Facilities 2012, 30, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, H.; Tse, H.M.; Stables, A.; Cox, S. Design as a social practice: The design of new build schools. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2017, 43, 767–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, A. Evolutionary game theory. In Evolutionary Social Sciences; Hammerl, M., Schwarz, S., Willführ, K.P., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2025; pp. 152–162. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, R.; Loi, E.H.N.; Wang, X.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, T. A stochastic evolutionary game of boosting urban low-carbon development in China. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 33853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhu, D.; Wang, J. Impact of policy adjustments on low carbon transition strategies in construction using evolutionary game theory. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Qu, X.; Gong, Z. Decision mechanism of farmers’ low-carbon agricultural technology adoption: An evolutionary game theory approach. Empirica 2025, 52, 297–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wu, S.; You, H.; Wang, C. Governments’ behavioral strategies in cross-regional reduction of inefficient industrial land: Learned from a tripartite evolutionary game model. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zang, Z.; Ji, Q.; Sun, C.; Qiang, W.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, C.; Sun, F.; Xiong, H. Rethinking Generalizability and Discriminability of Self-Supervised Learning from Evolutionary Game Theory Perspective. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2025, 133, 3542–3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, G. An evolutionary game theory for event-driven ecological population dynamics. Theory Biosci. 2025, 144, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, H.; Franz, J.; Willis, J. (Eds.) School Spaces for students wellbeing and learning. In Insight from Research and Practice; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- AThanh, P.T.; Grierson, D. A Study on Children’s Spatial—Social—Natural Interactions Within Primary School: Design Approaches for Case Studies in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. In Proceedings of the 16th Asian Urbanization Conference, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 11–13 January 2024; Vien, H.T., Pomeroy, G.M., Ngoc Hieu, N., Eds.; AUC 2024. Advances in 21st Century Human Settlements. Springer: Singapore, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenath, N.; Ranade, P.; Verma, I.K. AI-Powered Personalised Learning in Primary Education: A Design Thinking Perspective. In Computing and Machine Learning; Bansal, J.C., Borah, S., Hussain, S., Salhi, S., Eds.; CML 2024. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Singapore, 2024; Volume 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falzon, D.; Conrad, E. Designing primary school grounds for Nature-based learning: A review of the evidence. J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 2024, 27, 437–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesch, A.; Hespos, S.; Hirsh-Pasek, K. Playful learning landscapes in the United States: Encouraging intellectual and social risk in everyday spaces. In Risk and Outdoor Play; Gray, T., Sturges, M., Barnes, J., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.: Singapore, 2025; pp. 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Zu’bi, M.A.A.; Al-Mseidin, K.I.M.; Yaakob, M.F.M.; Fauzee, M.; Mahmood, M.; Sohri, N.; Al-Mawadieh, R.; Senathirajah, A. The impact of the school educational environment on primary school teachers’ commitment to educational quality. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuranov, V.; Guketlov, K.; Shogenova, F.; Mazloev, A. Analysis of the Space-Planning Solution of the School in Nalchik for Renovation. In Proceedings of the II International Scientific Conference “Recent Advances in Architecture and Construction”, Kazan, Russia, 14–15 May 2024; Klyuev, S.V., Vatin, N.I., Nabiullina, K.R., Yumagulova, V.M., Eds.; ICRAAC 2024. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Zhang, W.; Sun, D. Multi-class teaching: The exploration of Caowo Primary School in Gansu. In New Pathways of Rural Education in China; Han, J., Ed.; Educational Science Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2024; pp. 115–128. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, R.L.; Suarez, A.M. Do inquiry-based teaching and school climate influence science achievement and critical thinking? Evidence from PISA 2015. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2020, 7, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moolman, B.; Essop, R.; Makoae, M.; Swartz, S.; Solomon, J.-P. School climate, an enabling factor in an effective peer education environment: Lessons from schools in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Educ. 2020, 40, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Latif, N.A.; Mohd Hamzah, M.I.; Mohd Nor, M.Y. Teacher change in practice and holding: The role of collaboration. World J. Educ. 2021, 3, 279–288. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, M.C. A Bio-Ecological Exploratory Case Study of the Forest School Approach to Learning and Teaching in the Irish Primary School Curriculum. In Risk and Outdoor Play; Gray, T., Sturges, M., Barnes, J., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. Micro-school Community: The Development and Transformation of Fanjia Primary School in Sichuan. In New Pathways of Rural Education in China; Han, J., Ed.; Research in Chinese Education; Springer: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. An Empirical Quantitative Analysis of the Plane System of the Office Floor of the Super High-Rise Building. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2020. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=OfZxIIxxsvCrJUgZtw5hQ2zOXzaBsT5nSPKGkZYjNjR0ohyLeQJLxAjz-Ly_Dqz9A0x2KL-hxX6o9dYzZL91DsY0oa9eITznCygUHq9emGPCHbbMgd8SZzhd48t9P1zHqpoeLiYSCzFuisKY7OBYkXdhQRgN-PfjVGMBfjjl5o08ShQevpj5UqSLM5srjIHl&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Wang, Y. Study on Optimize Strategy of Holistic Teaching Building Group in University. Ph.D. Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2012. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=OfZxIIxxsvCENSC-o9-z0CYDvlaS_TXoRHoW8RyAr3Amk4srnLPSN9NexxR2iEn8C2P86Myb3jo25AwkRUYVaciZI5vpmLIBwCUmVJnXEGV3L-XoGuu7BESLwF8vmPVN1-fNe8Mo1ox4a6tNlAmHVcw7HilmKMAmNf-bv_WVyfEV6NIsgaNYqg==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 10 January 2025).

| No. | Symbol | Description | Recommended Initial Value | Sensitivity Interval | Data Source/Calibration Method | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benefits | ||||||

| 1 | ΔR | Incremental comprehensive benefit of low UAC | 20 | [5, 40] | Mean of 9 public school cases | ★ Key control variable |

| 2 | a | Benefit-sharing coefficient (schools-students) | 0.65 | [0.45, 0.85] | Two-round Delphi survey | ★ |

| 3 | b | Benefit-sharing coefficient (government-schools) | 0.60 | [0.50, 0.75] | Same as above | ★ |

| 4 | D | Construction cost savings | 5 | — | Cost audit reports | Fixed |

| 5 | G1 | Government incentives to schools | 2 | — | Policy documents | Fixed |

| 6 | G2 | Government incentives to students | 1 | — | Same as above | Fixed |

| 7 | G3 | Social reputation benefit | 2 | — | Converted from social benefits | Fixed |

| 8 | G4 | Supportive Benefit of Campus Space | 7 | _ | Academic-return valuation | Fixed |

| Costs | ||||||

| 9 | W1 | Government risk compensation to schools | 8 | [1, 15] | Provincial financial audits | ★ Policy lever |

| 10 | W2 | School risk compensation to students | 8 | — | School internal regulations | Fixed |

| 11 | C1 | Government’s active implementation cost | 4 | [2, 10] | Administrative cost surveys | ★ |

| 12 | C2 | Schools’ active demand cost | 3 | [1, 8] | Expert Delphi survey | ★ |

| 13 | C3 | Cost of students expressing demands | 1 | — | Questionnaire statistics | Fixed |

| 14 | S1 | Schools’ opportunity loss | 4 | — | School surveys | Fixed |

| 15 | S2 | Students’ opportunity loss | 3 | — | Same as above | Fixed |

| Combination (G, S, P) | Government (UG) | Schools (US) | Students (UP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Active, Request, Assert) | (1 − b)ΔR + G3 + D − C1 − G1 − G2 | (1 − a)bΔR + G1 − C2 | abΔR + G2 + G4 − C3 |

| (Active, Request, Not Assert) | (1 − b)ΔR + G3 + D − C1 − G1 | (1 − a)bΔR + G1 − C2 | abΔR + G2 |

| (Active, Not Request, Assert) | (1 − b)ΔR − C1 − G2 | −S1 | G2 − C3 |

| (Active, Not Request, Not Assert) | (1 − b)ΔR − C1 | −S1 | G2 |

| (Passive, Request, Assert) | D − W1 | G1 − W2 − C2 | abΔR − C3 |

| (Passive, Request, Not Assert) | D − W1 | G1 − C2 | abΔR |

| (Passive, Not Request, Assert) | 0 | 0 | −C3 |

| (Passive, Not Request, Not Assert) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Scenario | ΔR | W1 | C1 | Expected ESS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | 20 | 8 | 4 | (1,1,1) |

| Negative | 5 | 2 | 8 | (0,0,0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhu, S.; Wang, X.; Zhao, D.; Song, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, S. Evolutionary Game Theory in Architectural Design: Optimizing Usable Area Coefficient for Qingdao Primary Schools. Buildings 2026, 16, 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020244

Zhu S, Wang X, Zhao D, Song Y, Li X, Wang S. Evolutionary Game Theory in Architectural Design: Optimizing Usable Area Coefficient for Qingdao Primary Schools. Buildings. 2026; 16(2):244. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020244

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Shuhan, Xingtian Wang, Dongmiao Zhao, Yeliang Song, Xu Li, and Shaofei Wang. 2026. "Evolutionary Game Theory in Architectural Design: Optimizing Usable Area Coefficient for Qingdao Primary Schools" Buildings 16, no. 2: 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020244

APA StyleZhu, S., Wang, X., Zhao, D., Song, Y., Li, X., & Wang, S. (2026). Evolutionary Game Theory in Architectural Design: Optimizing Usable Area Coefficient for Qingdao Primary Schools. Buildings, 16(2), 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16020244