Indoor Light Environment Comfort Evaluation Method Based on Deep Learning and Evoked Potentials

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Related Works

1.3. Research Gap and Contributions

- (1)

- A new objective evaluation paradigm for indoor lighting environment comfort has been proposed.

- (2)

- Realized deep end-to-end temporal modeling of EEG signals.

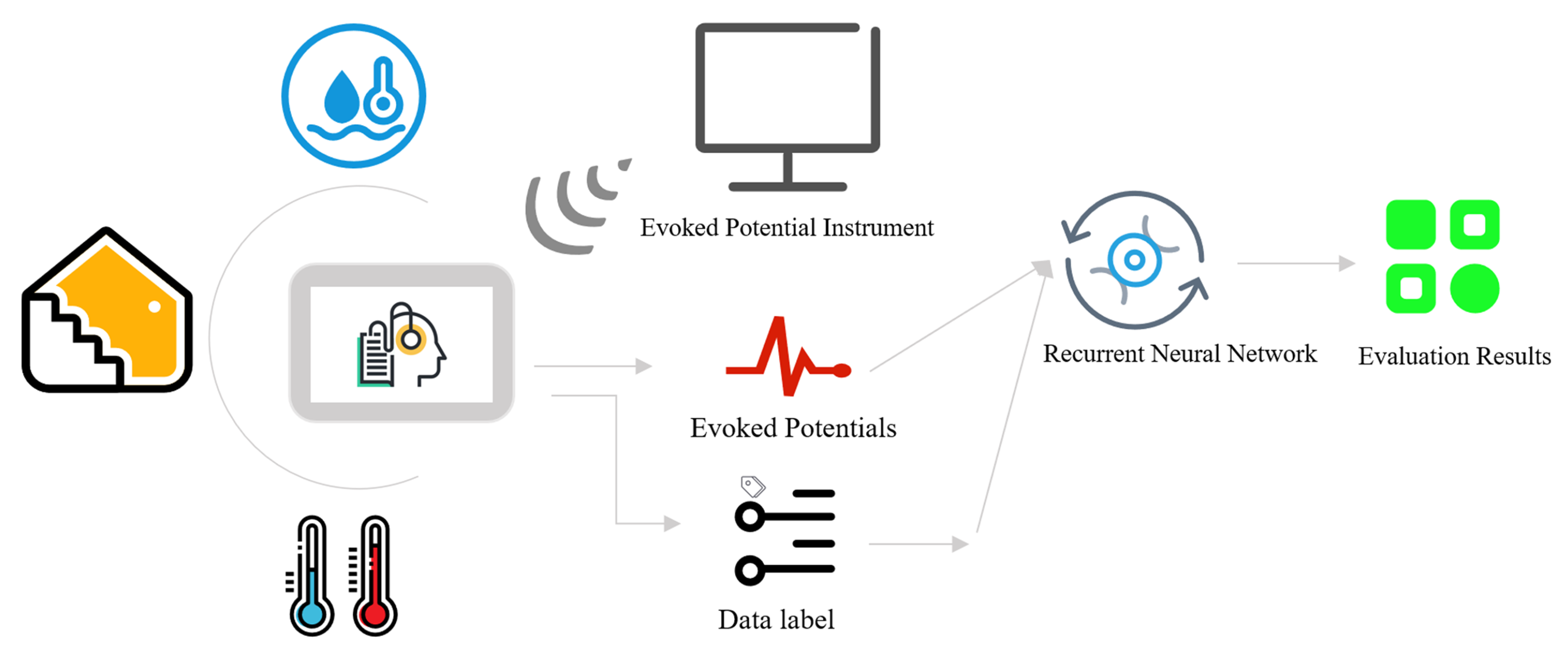

2. Methodology

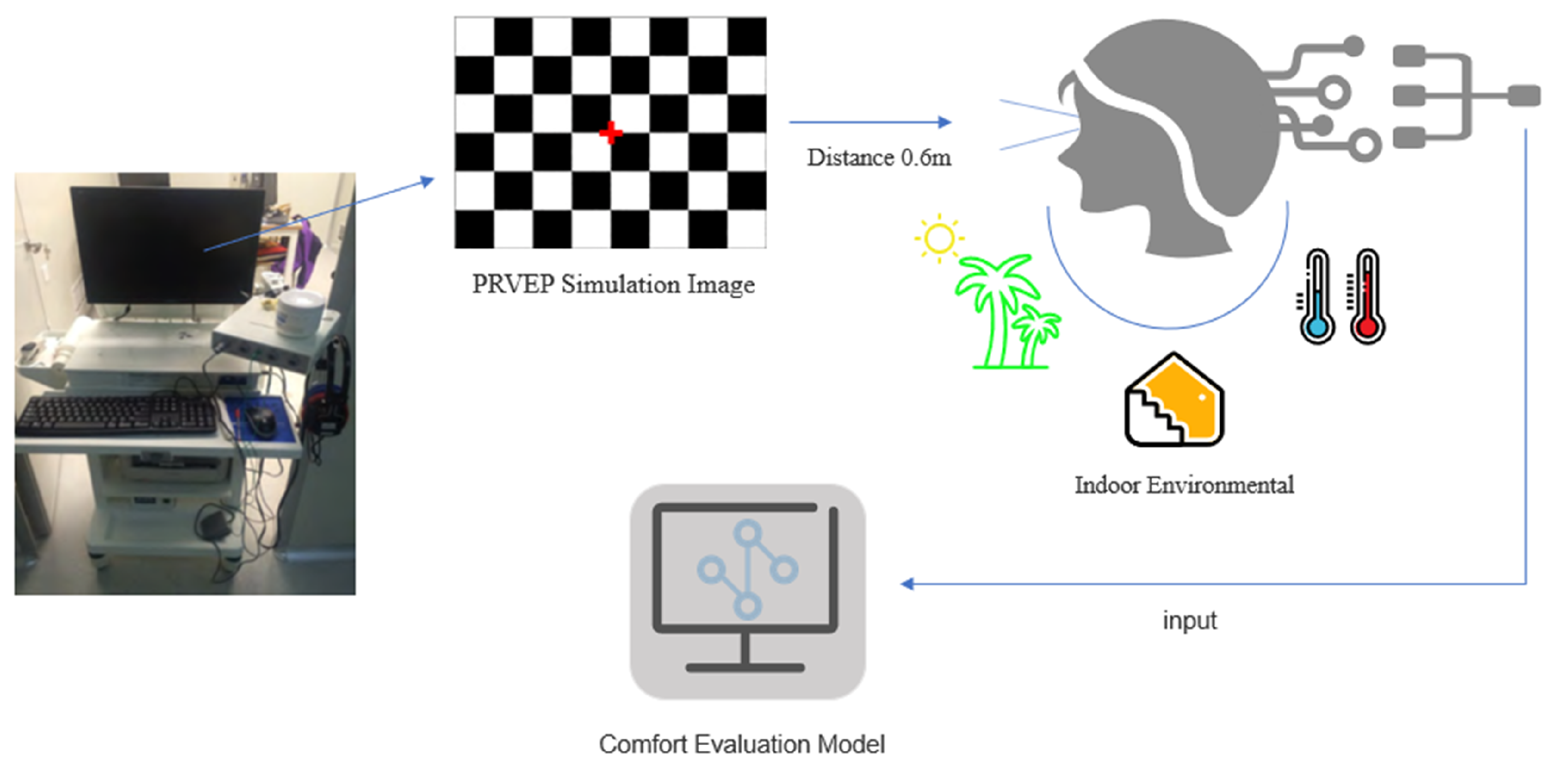

2.1. Environmental Setup

2.2. Data Acquisition

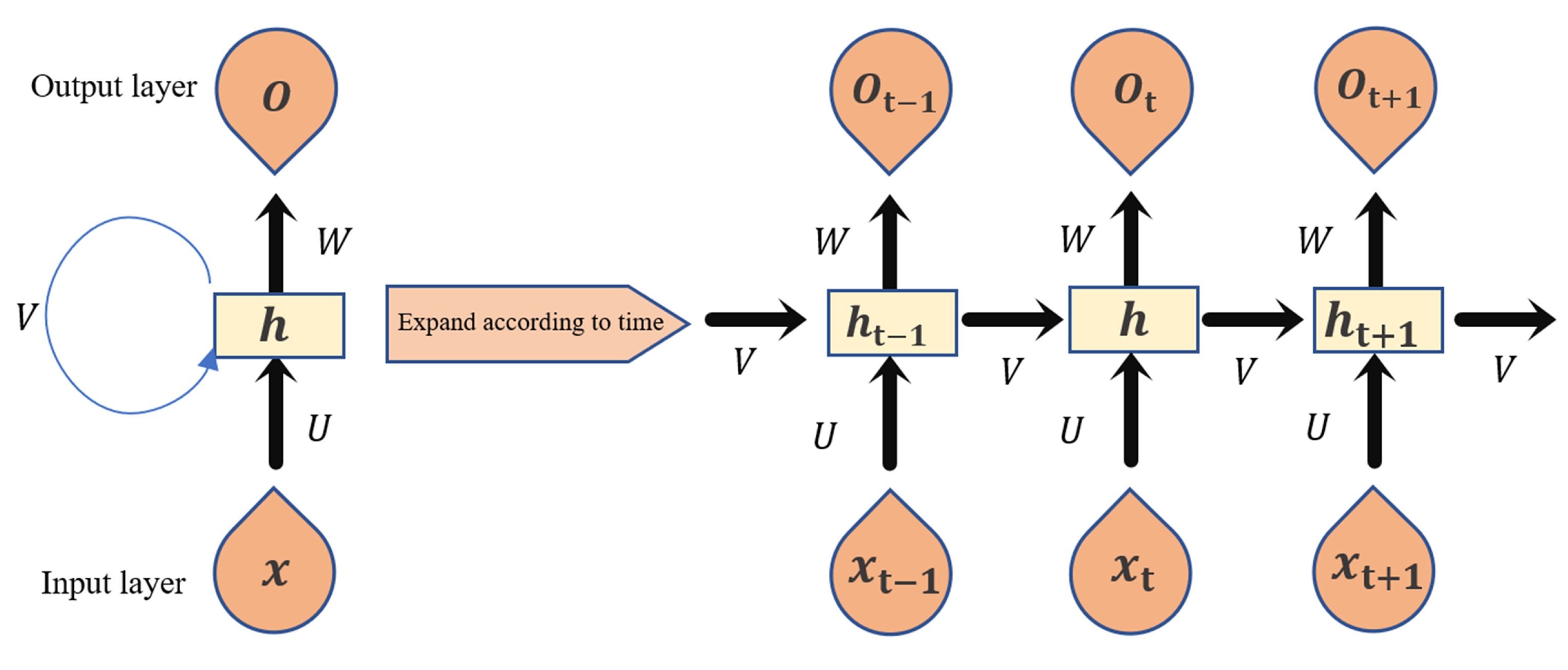

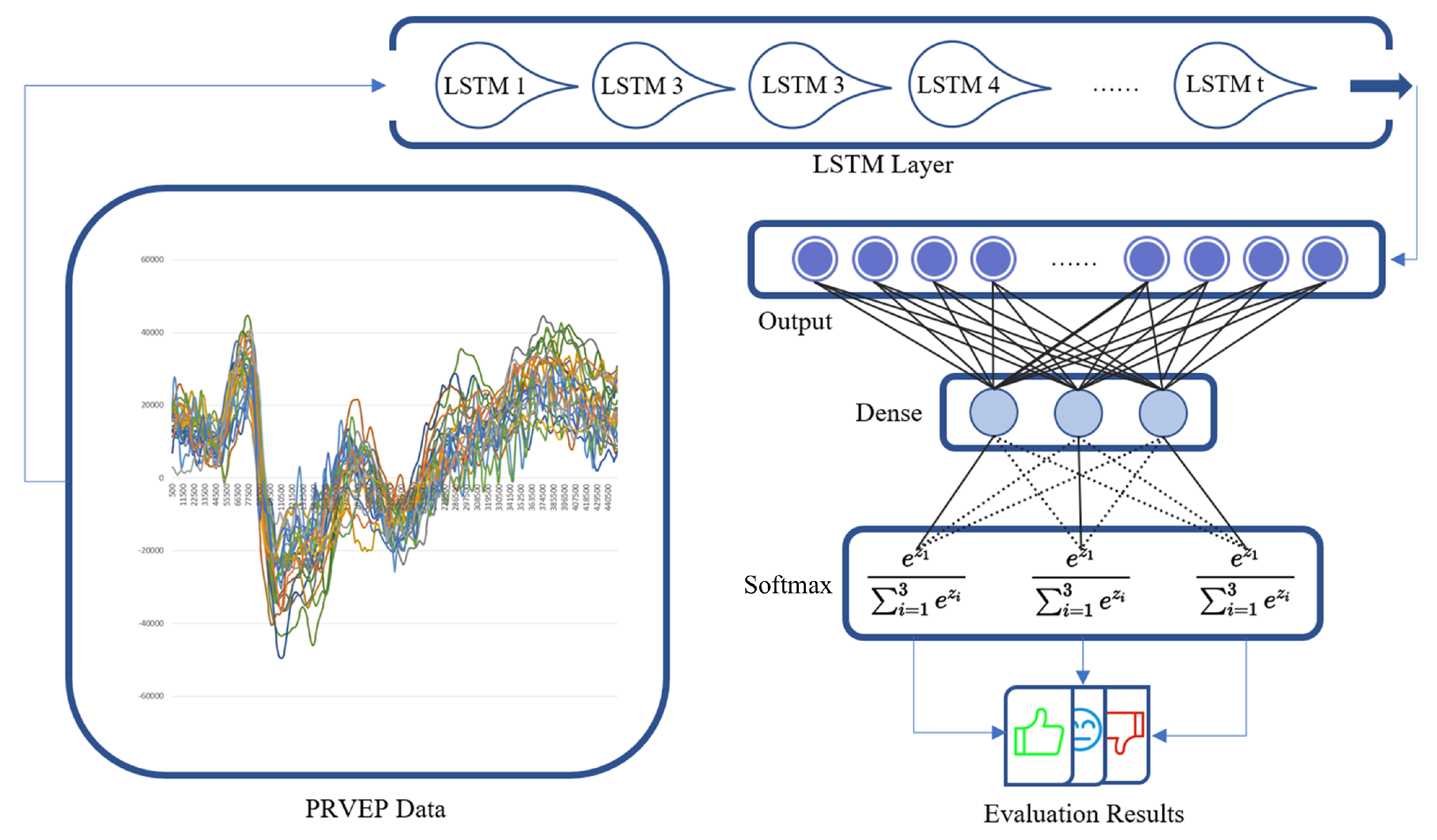

2.3. Recurrent Neural Network

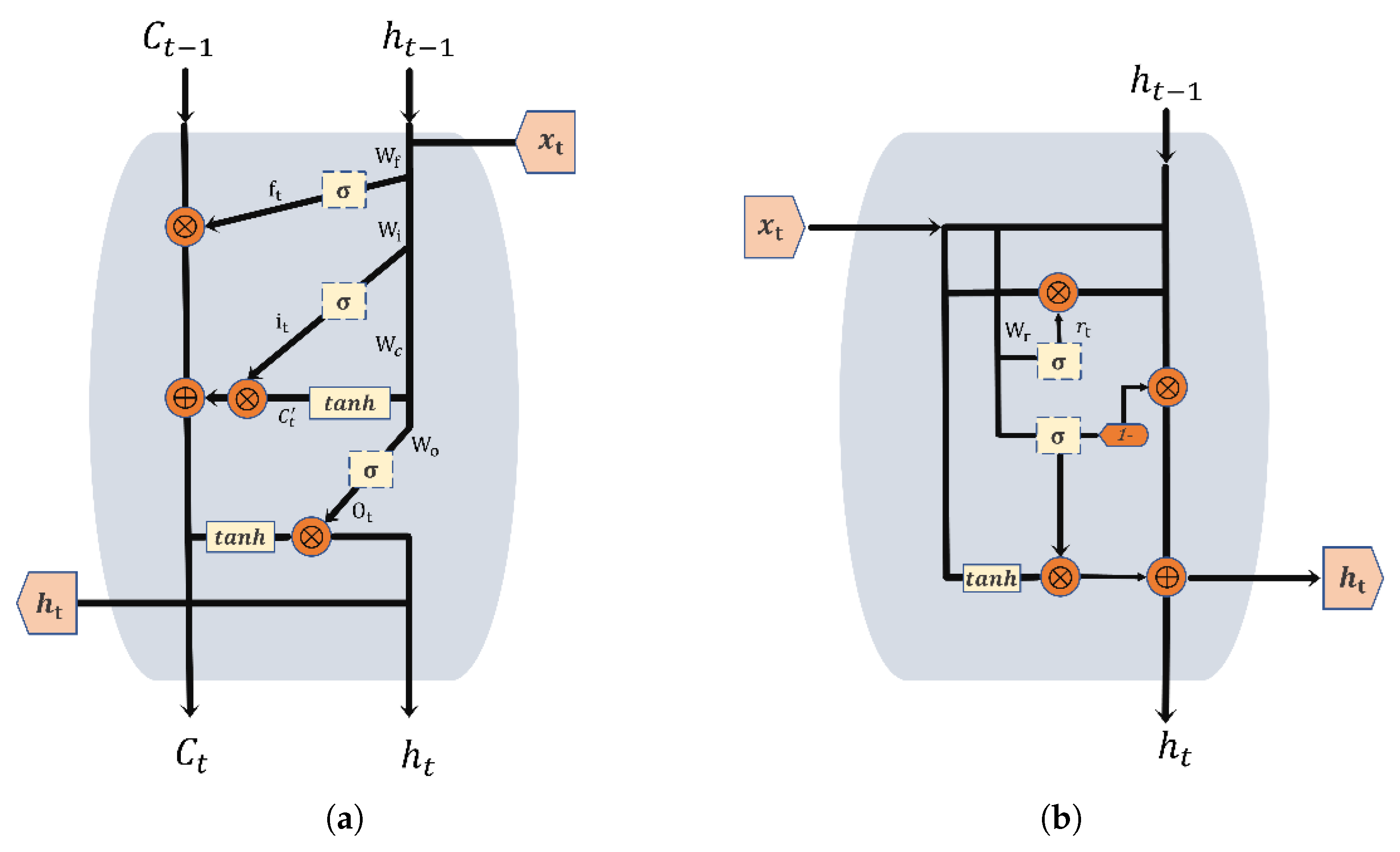

2.4. LSTM and GRU

2.5. Modeling

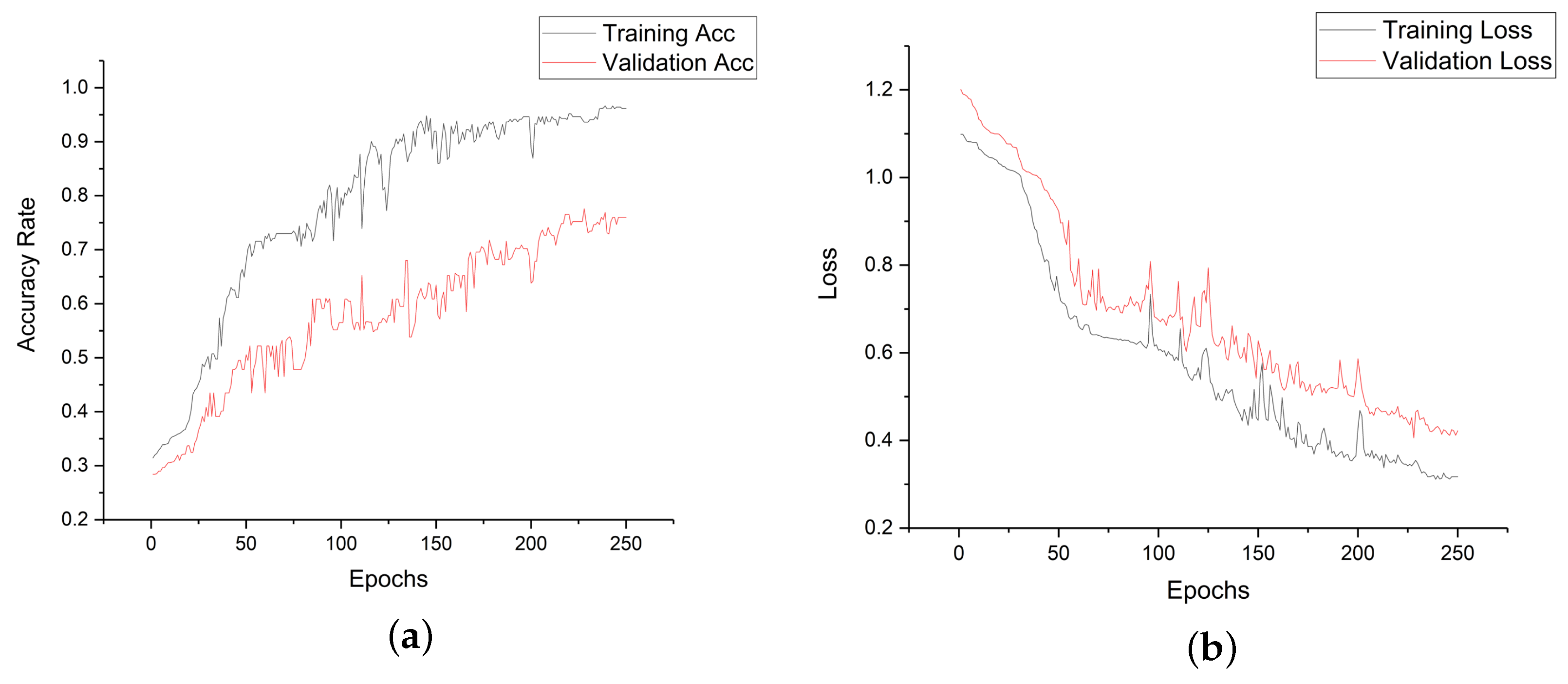

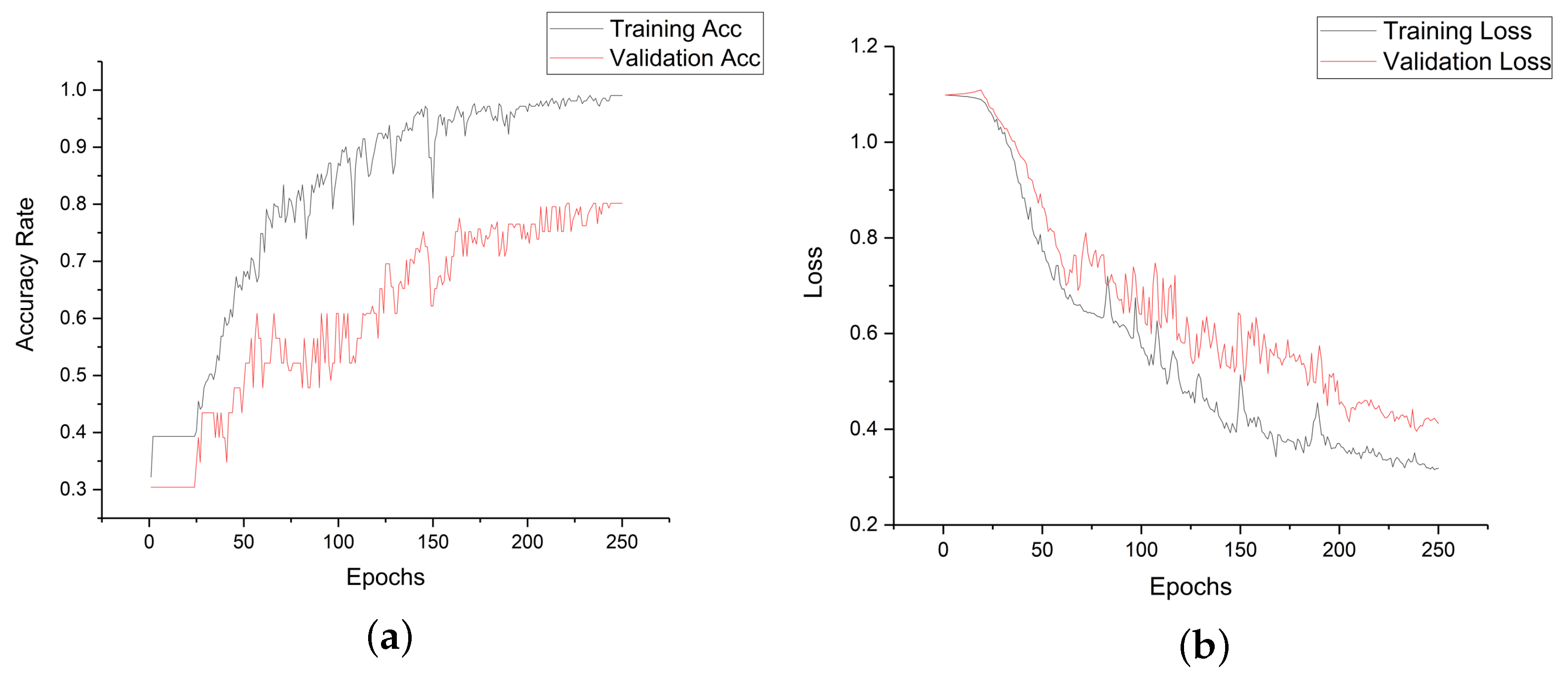

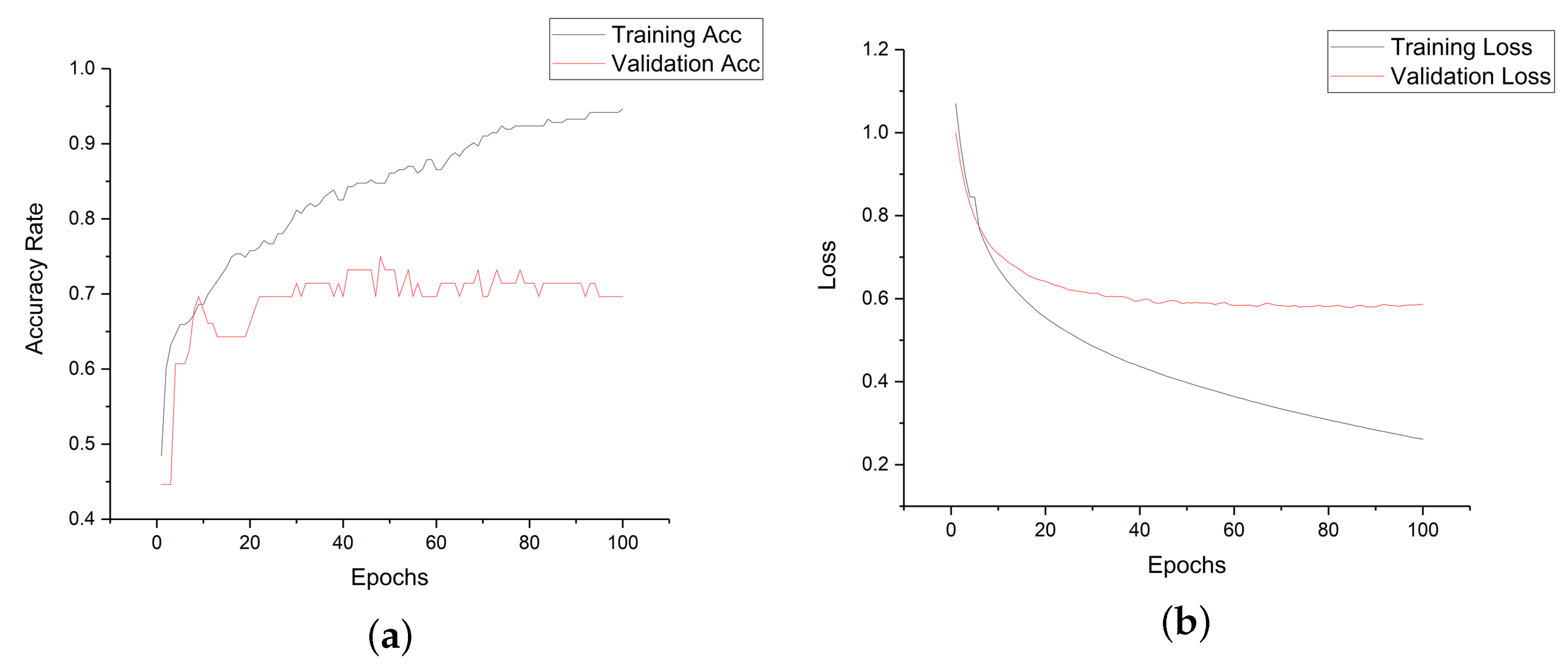

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Irga, P.J.; Mullen, G.; Fleck, R.; Matheson, S.; Wilkinson, S.J.; Torpy, F.R. Volatile organic compounds emitted by humans indoors—A review on the measurement, test conditions, and analysis techniques. Build. Environ. 2024, 255, 111442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Zhao, L.; Li, W.; Wu, J.; Zomaya, A.Y. Towards healthy and cost-effective indoor environment management in smart homes: A deep reinforcement learning approach. Appl. Energy 2021, 300, 117335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerasinghe, A.S.; Rasheed, E.O.; Rotimi, J. Occupants’ Decision-Making of Their Energy Behaviours in Office Environments: A Case of New Zealand. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikookar, N.; Sawyer, A.O.; Goel, M.; Rockcastle, S. Investigating the Impact of Combined Daylight and Electric Light on Human Perception of Indoor Spaces. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Wang, L.; Wu, Y.; Liang, Z.; Yu, J.; Chen, T. Computational design of indoor lighting supported by artificial intelligence: Recent advances and future prospects. Build. Environ. 2025, 285, 113575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.T.; Mui, K.W.; Hui, P.S. A multivariate-logistic model for acceptance of indoor environmental quality (IEQ) in offices. Build. Environ. 2008, 43, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantozzi, F.; Rocca, M. An Extensive Collection of Evaluation Indicators to Assess Occupants’ Health and Comfort in Indoor Environment. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, S.; Hataoka, H. Physiological effects of illuminance. J. Light Vis. Environ. 1986, 10, 1_15–1_20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Hu, S.; Liu, G. Evaluation Model of Specific Indoor Environment Overall Comfort Based on Effective-Function Method. Energies 2017, 10, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Mak, C.M. Relationships between indoor environmental quality and environmental factors in university classrooms. Build. Environ. 2020, 186, 107331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, A.K.; Arif, M.; Syal, M.M.G.; Rana, M.Q.; Oladinrin, O.T.; Sharif, A.A.; Alshdiefat, A.A.S. Effect of Indoor Environment on Occupant Air Comfort and Productivity in Office Buildings: A Response Surface Analysis Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Yin, S.; Jiang, X. Indoor thermal environmental evaluation of Chinese green building based on new index OTCP and subjective satisfaction. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 240, 118151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, E.M.A.; Neves, A.I.A.; Falcão, C.A.; Sousa, R.V.C.; Carvalho, J.P.; Leite, W.K.S.; Da Silva, L.B. Comfort requirements assessment on indoor environmental quality in hospital’s ICU. In Proceedings of the Occupational Safety and Hygiene IV—Selected, Extended and Revised Contributions from the International Symposium Occupational Safety and Hygiene, Guimaraes, Portugal, 23–24 March 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Molina, A.; Boarin, P.; Tort-Ausina, I.; Vivancos, J.L. Post-occupancy evaluation of a historic primary school in Spain: Comparing PMV, TSV and PD for teachers’ and pupils’ thermal comfort. Build. Environ. 2017, 117, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nian, F.; Wang, K. Study on indoor environmental comfort based on improved PMV index. In Proceedings of the 2017 3rd International Conference on Computational Intelligence & Communication Technology (CICT), Ghaziabad, India, 9–10 February 2017; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsul, B.M.T.; Sia, C.C.; Ng, Y.G.; Karmegan, K.J.A.J. Effects of Light’s Colour Temperatures on Visual Comfort Level, Task Performances, and Alertness among Students. Am. J. Public Health Res. 2013, 1, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, F.; Ma, Z.; Bai, M.; Liu, S. Experimental investigation and evaluation of the performance of air-source heat pumps for indoor thermal comfort control. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2018, 32, 1437–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Shi, H. Evaluating the overall comfort of undergraduates by using the punishment substitution method. Indoor Built Environ. 2022, 31, 1577–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Dangol, R.; Hyvärinen, M.; Bhusal, P.; Puolakka, M.; Halonen, L. User acceptance studies for LED office lighting: Lamp spectrum, spatial brightness and illuminance. Light. Res. Technol. 2015, 47, 54–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Te Kulve, M.; Schlangen, L.; van Marken Lichtenbelt, W. Interactions between the perception of light and temperature. Indoor Air 2018, 28, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Moon, J.W.; Kim, S. Analysis of Occupants’ Visual Perception to Refine Indoor Lighting Environment for Office Tasks. Energies 2014, 7, 4116–4139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, E.; Hu, J.; Patel, M. Energy and visual comfort analysis of lighting and daylight control strategies. Build. Environ. 2014, 78, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Zhang, M.Z.; Hu, S.T.; Zhang, X. Experimental study on thermal sensation and physiological parameter changes under the interaction of environmental temperature and taste. Energy Build. 2025, 345, 116093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, M.J.; Denton, D.A.; Ryan, P.J.; Yao, S.T.; Stefanidis, A.; Oldfield, B.J. From sensory circumventricular organs to cerebral cortex: Neural pathways controlling thirst and hunger. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2019, 31, e12689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadon-Grosman, N.; Asher, T.; Loewenstein, Y. On the geometry of somatosensory representations in the Cortex. NeuroImage 2025, 317, 121321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godenzini, L.; Alwis, D.; Guzulaitis, R.; Honnuraiah, S.; Stuart, G.J.; Palmer, L.M. Auditory input enhances somatosensory encoding and tactile goal-directed behavior. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noachtar, S.; Remi, J.; Kaufmann, E. Electroencephalography—An Update. Klin. Neurophysiol. 2022, 53, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teplan, M. Fundamentals of EEG Measurement. Meas. Sci. Rev. 2002, 2, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.; Lin, Y.; Fan, C.; Xu, Q.; Xu, D.; Yi, S.; Zhang, H.; Wang, K. Passenger overall comfort in high-speed railway environments based on EEG: Assessment and degradation mechanism. Build. Environ. 2022, 210, 108711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küller, R.; Wetterberg, L. Melatonin, cortisol, EEG, ECG and subjective comfort in healthy humans: Impact of two fluorescent lamp types at two light intensities. Light. Res. Technol. 1993, 25, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Yang, E.; Zhou, J.; Chang, V.W.C. Human-building interaction under various indoor temperatures through neural-signal electroencephalogram (EEG) methods. Build. Environ. 2018, 129, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Hu, S.; Lu, M.; He, M.; Zhang, X.; Liu, G. Analysis of human electroencephalogram features in different indoor environments. Build. Environ. 2020, 186, 107328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Li, H.; Qi, H. Using electroencephalogram to continuously discriminate feelings of personal thermal comfort between uncomfortably hot and comfortable environments. Indoor Air 2020, 30, 534–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Hu, S.; Mao, Z.; Liang, P.; Xin, S.; Guan, H. Research on work efficiency and light comfort based on EEG evaluation method. Build. Environ. 2020, 183, 107122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinear, C.M.; Byblow, W.D.; Ackerley, S.J.; Smith, M.C.; Borges, V.M.; Barber, P.A. PREP2: A biomarker-based algorithm for predicting upper limb function after stroke. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2017, 4, 811–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bembenek, J.P.; Kurczych, K.; Karliński, M.; Członkowska, A. The prognostic value of motor-evoked potentials in motor recovery and functional outcome after stroke—A systematic review of the literature. Funct. Neurol. 2012, 27, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murtazina, M.S.; Avdeenko, T.V. Classification of Brain Activity Patterns Using Machine Learning Based on EEG Data. In Proceedings of the 2020 1st International Conference Problems of Informatics, Electronics, and Radio Engineering (PIERE), Novosibirsk, Russia, 10–11 December 2020; pp. 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdary, M.K.; Anitha, J.; Hemanth, D.J. Emotion Recognition from EEG Signals Using Recurrent Neural Networks. Electronics 2022, 11, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Kumar, D.R.; Khatti, J.; Samui, P.; Grover, K.S. Prediction of bearing capacity of pile foundation using deep learning approaches. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 2024, 18, 870–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasneem, S.; Ageeli, A.A.; Alamier, W.M.; Hasan, N.; Safaei, M.R. Organic catalysts for hydrogen production from noodle wastewater: Machine learning and deep learning-based analysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 52, 599–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, D.; Chen, X.; Wei, Z.; Ji, S. Prediction of flexural and uniaxial compressive strengths of sea ice with optimized recurrent neural network. Ocean. Eng. 2023, 288, 115921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gu, Z.; Thé, J.V.; Yang, S.X.; Gharabaghi, B. The Discharge Forecasting of Multiple Monitoring Station for Humber River by Hybrid LSTM Models. Water 2022, 14, 1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahjoub, S.; Chrifi-Alaoui, L.; Marhic, B.; Delahoche, L. Predicting Energy Consumption Using LSTM, Multi-Layer GRU and Drop-GRU Neural Networks. Sensors 2022, 22, 4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S.L.; Klistorner, A. The Visual Evoked Potential in Humans. In Stimulation and Inhibition of Neurons; Pilowsky, P.M., Farnham, M.M.J., Fong, A.Y., Eds.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 287–299. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein, M.H.; Mash, C.; Arterberry, M.E.; Gandjbakhche, A.; Nguyen, T.; Esposito, G. Visual stimulus structure, visual system neural activity, and visual behavior in young human infants. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0302852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Maximum Age (Year) | Minimum Age (Year) | Average Age (Year) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 26 | 22 | 23.9 |

| Female | 25 | 22 | 23.3 |

| All Tester | 26 | 22 | 23.6 |

| Conditions | Temperature (°C) | Illuminance (lx) | Decibel (dB) | Color-Temperature (K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18 | 100 | 50 | 5700 |

| 2 | 18 | 100 | 50 | 4000 |

| 3 | 18 | 100 | 50 | 3000 |

| 4 | 18 | 300 | 50 | 5700 |

| 5 | 18 | 300 | 50 | 3000 |

| 6 | 18 | 300 | 50 | 4000 |

| 7 | 18 | 500 | 50 | 3000 |

| 8 | 18 | 500 | 50 | 4000 |

| 9 | 18 | 500 | 50 | 5700 |

| 10 | 22 | 300 | 50 | 4000 |

| 11 | 22 | 500 | 50 | 3000 |

| 12 | 22 | 300 | 50 | 5700 |

| 13 | 22 | 500 | 50 | 3000 |

| 14 | 22 | 500 | 50 | 4000 |

| 15 | 22 | 500 | 50 | 5700 |

| 16 | 22 | 100 | 50 | 3000 |

| 17 | 22 | 100 | 50 | 5700 |

| 18 | 22 | 100 | 50 | 4000 |

| 19 | 26 | 500 | 50 | 3000 |

| 20 | 26 | 500 | 50 | 5700 |

| 21 | 26 | 500 | 50 | 4000 |

| 22 | 26 | 300 | 50 | 5700 |

| 23 | 26 | 300 | 50 | 4000 |

| 24 | 26 | 300 | 50 | 3000 |

| 25 | 26 | 100 | 50 | 5700 |

| 26 | 26 | 100 | 50 | 3000 |

| 27 | 26 | 100 | 50 | 4000 |

| Algorithm | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FNN | 69.64% | 73.58% | 41.96% | 53.44% | 2.31s |

| LSTM | 80.16% | 89.18% | 44.54% | 59.41% | 36.21s |

| GRU | 75.99% | 83.96% | 42.85% | 56.74% | 32.09s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miao, S.; Li, S.; Yang, X.; Guan, H.; Shen, X. Indoor Light Environment Comfort Evaluation Method Based on Deep Learning and Evoked Potentials. Buildings 2025, 15, 4571. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244571

Miao S, Li S, Yang X, Guan H, Shen X. Indoor Light Environment Comfort Evaluation Method Based on Deep Learning and Evoked Potentials. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4571. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244571

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiao, Sheng, Sudong Li, Xixin Yang, Hongyu Guan, and Xiang Shen. 2025. "Indoor Light Environment Comfort Evaluation Method Based on Deep Learning and Evoked Potentials" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4571. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244571

APA StyleMiao, S., Li, S., Yang, X., Guan, H., & Shen, X. (2025). Indoor Light Environment Comfort Evaluation Method Based on Deep Learning and Evoked Potentials. Buildings, 15(24), 4571. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244571