1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

With the continuous evolution of social structure and population characteristics, the process of population aging is accelerating, and the birth rate shows a continuous downward trend [

1]. These demographic shifts have exacerbated the disparity between the supply and demand of community public service facilities. Meanwhile, traditional universal provision models and static planning strategies are no longer adequate to meet diverse societal needs [

2]. Community embedded service facilities have become the core carriers for undertaking governance transformation. They need to integrate diverse functions such as elderly care, childcare, cultural and entertainment services, and medical care within a limited space [

3]. These factors collectively drive the transformation and upgrading of community service facilities. Their functions have progressively expanded from single-purpose cultural and recreational venues to encompassing diverse spaces for education, exhibitions, leisure, office use, and ecological services. However, most of the existing community service facilities are configured with a single function, and their spatial organization mode is relatively fixed. They lack the flexibility to cope with function adjustment and service expansion, and it is difficult to meet the compound needs of residents arising from changes in the life cycle and family structure.

From the perspective of public service provision and facility development, community service centers are not only service delivery platforms but are increasingly being regarded as “social infrastructure” or “service hubs”. Their characteristics—functional integration, spatial consolidation, green and low-carbon design, and digital transformation (digital empowerment)—are becoming increasingly significant [

4,

5]. Among these characteristics, functional diversity, spatial efficiency, and digitalization represent the prevailing trends, as evidenced by the concepts of ‘community-embedded service facilities’ and ‘digitalization empowering urban community-embedded services. Against this backdrop of developmental trends and policy support, community service centers as public buildings must also incorporate these principles. Within their effective spatial boundaries, they should achieve functional diversity, flexibility, sustainability, and low-carbon development.

Consequently, overcoming the traditional paradigm of “static planning and single-service provision” to construct community centers that are functionally integrative and spatially adaptable has become a critical imperative in current architectural research. This study aims to explore spatial organization and construction for community service centers that cater to the multi-level needs of residents and maintain openness and sustainability in the time dimension, so as to respond to the continuously evolving social life scenarios.

1.2. Research Status

With the rapid development of urbanization, according to the prediction of the OECD, China’s urbanization rate will reach 75% by 2050. Among them, as the basic constituent unit of modern cities, urban communities are not only the main space and key support for the daily production and life of urban residents, but also the intersection of political, economic, cultural and other issues in urban society [

6]. Concurrently, in response to the national ‘dual carbon’ objectives, low-carbon communities (or sustainable/eco-communities) are the most basic components of a low-carbon society and models for low-carbon cities. Moreover, in a sense, they can be regarded as the foundation for building a low-carbon society and realizing the low-carbon development strategy [

7]. Low-carbon communities represent a new paradigm for sustainable urban development, serving as an essential pathway towards achieving the carbon peaking and carbon neutrality targets [

8]. The green and low-carbon retrofitting of existing community service centers, as well as new construction projects, has emerged as a research and piloting priority. Key research areas include green community design strategies, the application of low-carbon and zero-carbon building technologies within community facilities, and the integration of community energy management with renewable energy sources [

9]. The concept of the community center as a collection of physical facilities, services, and social resources has received significant attention [

10], with a growing emphasis on “transitioning from single-purpose community centers towards multiservice facilities” [

11]. Consequently, the diversification of community functions and spatial integration has progressively gained importance. In terms of functional integration (mixed-use), Jacobs proposed the concept of mixed-use in the 1960s, opposing the modernist practice of dividing cities into single-function zones [

12], While contemporary research predominantly focuses on the community level, the applicability of mixed-use at the building scale is now widely recognized [

13].

In addition to the above policy requirements, the current design requirements and research gaps of community centers can also be seen in some practical cases. For example, the overall design of the Suk Agawa Community Center emphasizes alignment with community needs and flexible use. It is mainly characterized by open stepped terraces, cantilevered floors, and an activity-oriented floor plan. At the same time, it also takes into account the integration of the building with the surrounding environment and the city, successfully connecting the city and the residents [

14]. Chen et al. (2025) [

15] took the renovation of an abandoned boiler room in Shenyang as an example. The research shows that transforming old spaces into community service centers with composite functions can greatly improve the site utilization efficiency (the utilization rate increases by 2.2 times) and vitality (the daily activity duration is extended by 12 h, and the cross-age interaction frequency increases by 43%). The research proposes the mechanism of “functional hybridization–spatial permeability–usage sustainability” and recommends community service centers as the preferred model for urban renewal to promote multi-functional spaces and low-carbon utilization (reduce large-scale demolition) [

15]. In the design of the Shepherd Park Community Center, two modes are integrated: an educational mode for daily use and a community mode for night use. During the day, the annex building serves as an activity area for students, and in the evening, it is “flipped” for community use. The design exceeds the LEED Silver standard. Through intelligent technology and an efficient electromechanical system, the building’s energy consumption is close to net-zero, achieving low-carbon operation. The “day–night flip mode” significantly saves land use and improves the functional utilization rate.

These three cases each have different focuses and have some deficiencies. For example, in the future, as the population structure of the community changes, the functional requirements will also change accordingly. Then, how to carry out the renovation with the lowest loss cost and carbon emissions? Under this consideration and combined with policy requirements, this study proposes a theoretical and practical system for sustainable community buildings. Taking the support structure theory as the main body, extend the entire life cycle of buildings and reduce the construction waste generated during building demolition and renovation, to achieve the goal of low carbon. Habraken’s “support–infill” concept and Open Building have laid the theoretical foundation for “permanent structure and variable function”. The “time-based architecture” proposed by Leupen et al. further incorporates the time dimension into design. These theories support the application of modular and support strategies in the sustainable design of public buildings. Habraken’s statement is that “the supporting structure belongs to the public domain and is permanent; while the fillers belong to individuals and can be changed. Public participation and user freedom of choice are the key goals” can also serve as theoretical support for the characteristic that “the community service center has diverse functions, and its functional structure is not stable, requiring changes according to the needs of residents.” Therefore, in terms of mixed functions, a composite space system is adopted to increase the diversity and real-time practicality of functions in the limited land area. Meanwhile, supported by the “support structure–Infill System” structure, when the functional requirements change in the subsequent stage, not only can the functions be replaced conveniently, but also the cost and carbon emissions can be reduced.

1.3. Summary of the Current Situation and Research Objectives

With the acceleration of the urbanization process and the proposal of the “dual carbon” goal, the design of community service centers is moving towards the direction of functional compounding and low-carbon development. The construction of the “15-min living circle” driven by policies is committed to enhancing the functional diversification of community service centers through diversified service facilities, and the construction of low-carbon communities will also become an important path to achieve sustainable development. Meanwhile, functional mixing and community resilience have gradually become the research focus, emphasizing enhancing the long-term adaptability of communities through flexible spatial design. Theoretically, the “Support-Infill” theory proposed by Habraken and the “Time-Based Architecture” theory by Leupen provide support for modular and functionally variable design and promote the long-term adaptability of building structures and functions. The community service center, a public building, aims to meet the diverse needs of local people and the requirements for indoor and outdoor activities. Considering the different behavior patterns of the crowd, functionally independent spaces are designed to meet different needs. These independent spaces also penetrate each other to form a complete space.

In this design, the mutual Permeability between spaces of different forms and spaces with different functions is studied. By overlapping and staggering blocks, various forms of spaces such as set-back terraces, outdoor activity platforms, and gray spaces under the eaves, as well as outdoor and semi-outdoor activity spaces are constructed to meet the needs of activity participants for gathering spaces, enhancing the interest and architectural vitality. Thus, a public building is created where the spaces have rich and diverse morphological changes, and these changing spaces blend with each other to form an integrated whole. At the same time, as a public activity platform that promotes communication among neighbors and provides comfortable and comprehensive services, the community service center also has important significance for improving the community management level and promoting the comprehensive development of the community. By staggering, overlapping, and stacking spaces with different functions or forms vertically or horizontally, a space with a sense of hierarchy and mutual integration is created. This design concept not only enriches the form of the space but also improves the utilization efficiency of the space and promotes communication and interaction between different functional areas. On the other hand, the design of community service centers urgently needs to explore an integrated path of “high density, multi-function, low energy consumption, and strong sense of belonging” to solve problems such as space efficiency, functional diversity, and the entire building life cycle.

2. Methodology

As shown in

Figure 1, the research based on the Supports Theory as the structural framework and integrating the composite functional space system, a sustainable design methodology system for community service centers is constructed. This framework aims to achieve the structural variability, spatial complexity, and architectural resilience of buildings, and respond to the flexibility and sustainability requirements of community public buildings in a high-density urban environment.

2.1. Supports Theory

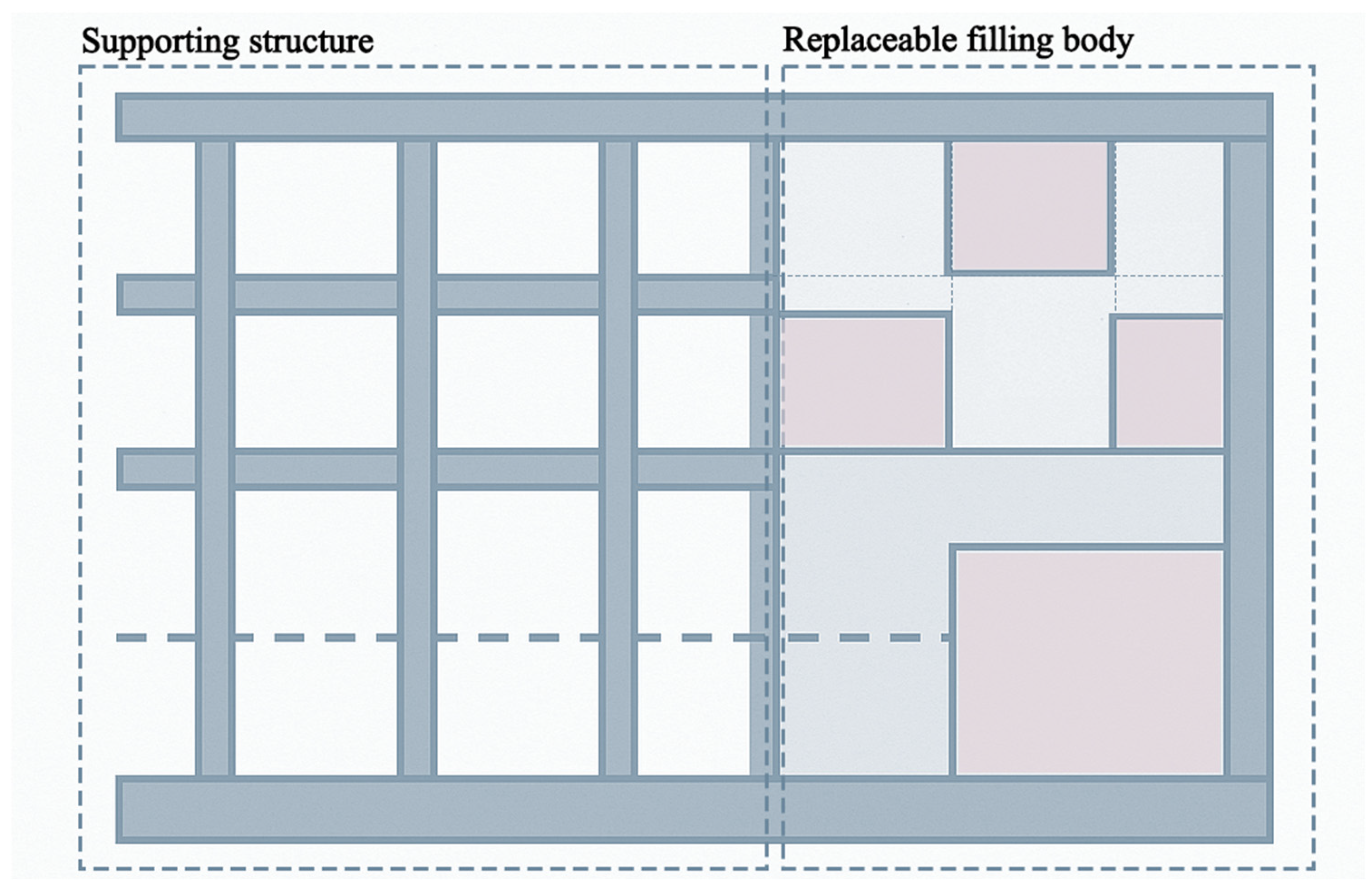

Community service centers serve as multifunctional integrated facilities designed to meet the diverse needs of residents. Consequently, they demand high levels of functional versatility, adaptability, and architectural sustainability. Conventional community public buildings, however, typically feature fixed spatial layouts and rigid structures, rendering them ill-equipped to respond effectively to the rapid evolution of community requirements. This often results in structures becoming functionally obsolete before reaching their physical lifespan. Dutch scholar Jan Habraken’s Supports Theory offers a novel approach to resolving this issue. As illustrated in

Figure 2, this theory emphasizes dividing buildings into long-term, stable ‘public domain’ and adaptable ‘infill elements’. By separating permanent structural supports (such as load-bearing walls and column grids) from replaceable infill elements (such as partition walls and equipment modules), it enables temporal adjustability and spatial adaptability of the building [

16]. This concept aligns closely with the contemporary architectural emphasis on “design for adaptability”.

Concurrently, the global construction industry faces challenges including excessive energy consumption, significant waste of building materials, and pressure to reduce carbon emissions [

17]. As community service functions frequently evolve with demographic shifts and policy directives (e.g., converting elderly care facilities into childcare centers), the use of support structures with pre-set standardized interfaces (such as unified column grids and centralized utility shafts) enables rapid replacement of infill modules (prefabricated partition walls, intelligent storage systems). This approach avoids extensive demolition and reconstruction work [

18]. This approach aligns closely with the Sustainable Development Goals outlined in the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [

19], and resonates with the life-cycle management and circular construction models advocated by the European Union’s Circular Economy Action Plan [

20], offering a viable pathway for the green, flexible, and sustainable development of future community service centers. By integrating diverse functional requirements with sustainability imperatives, the supporting structure theory combines with building life-cycle management and circular economy principles to explore forward-looking design models for community service centers.

2.2. Composite Spatial Structure

Facing the diverse functional requirements of community service centers, the traditional single layout often struggles to meet the needs of the compound use of space. From the renovation of small public spaces to the design of complex community centers, they all need to provide spaces for leisure activities, social interaction, and enhancing community awareness. The most typical design concept of community architecture is the community center, which provides a place for meetings and interactions, and its functions stem from the needs of the specific community [

21]. Based on this requirement, the architectural design achieves an efficient combination and dynamic balance of space by staggered superimposing and organically integrating different functional spaces in the vertical or horizontal direction.

Specifically, this approach employs a three-dimensional layout to segregate conflicting functions. For instance, modules exhibiting markedly contrasting characteristics—such as noisy versus quiet, public versus private, clean versus polluting—are separated across the vertical plane, thereby effectively preventing mutual interference. Simultaneously, utilizing vertical stratification allows additional functions to be stacked upon a limited building footprint, maximizing spatial resource utilization while preserving the building’s overall fluidity and coherence. On the “plan” level, horizontal interweaving techniques are employed to arrange different functions or spaces in an interlocking pattern, with partial overlaps or offset connections creating a visual permeability and functional interaction.

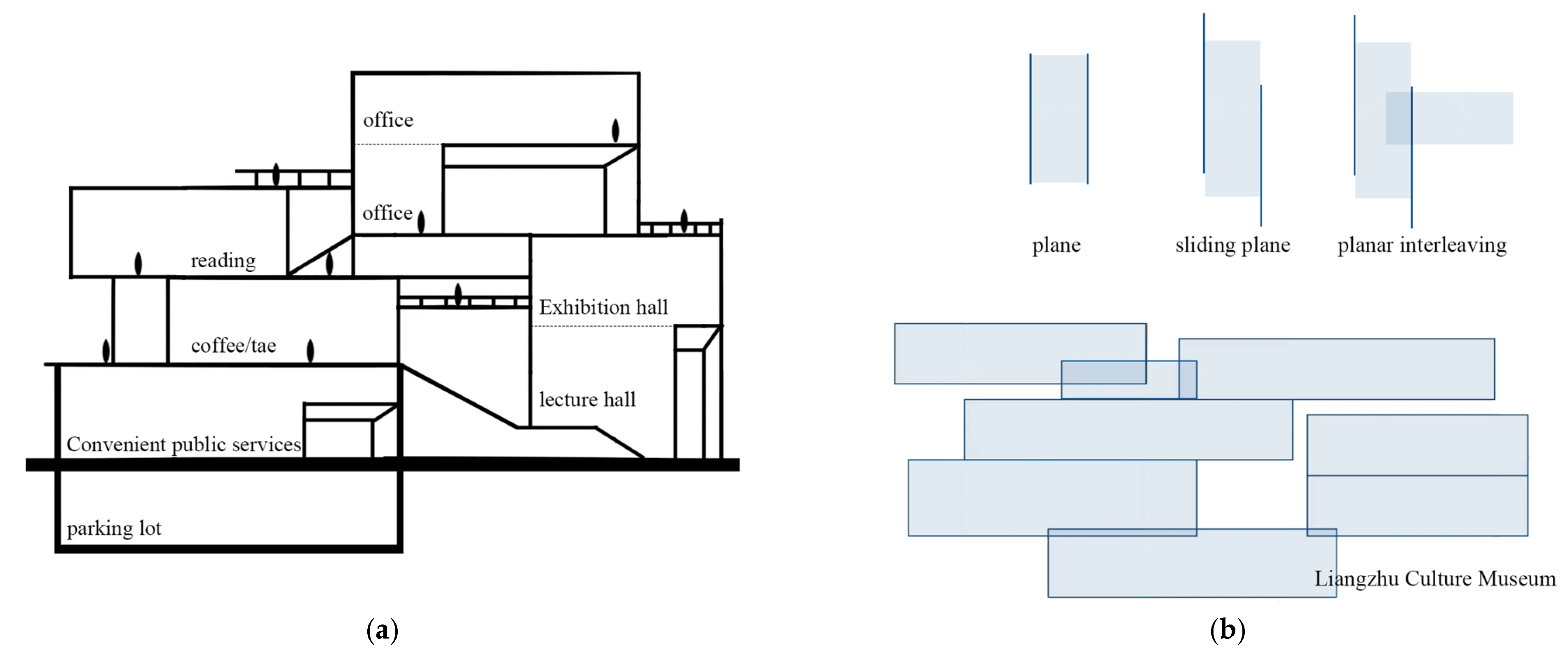

As shown in

Figure 3, “vertical stratification” rationally organizes functions; “horizontal interlacing” emotionally creates communication. This method not only enhances the complexity and utilization efficiency of the building space at the physical level but also promotes communication and interaction between different groups of people and functional modules at the social level. In a complex spatial environment, residents can not only conveniently access diverse services but also enhance the overall vitality and cohesion of the community during cross-functional communication processes [

22]. Especially under the current development requirements of “high density, multiple functions, low energy consumption, and strong sense of belonging”, functional diversification has become the core strategy for the design of community service centers.

With the continuous concentration of urban populations and the increasing scarcity of land resources, the rational integration of diverse functions—including public services, cultural and recreational activities, healthcare and wellness, as well as education and training—within a single building system can effectively alleviate land constraints and resource fragmentation. This multifunctional layering approach not only optimizes service efficiency but also enhances social value, transforming community service centers into comprehensive platforms and spiritual anchors for urban residents’ lives. More significantly, this design approach responds to the strategic imperative of modernizing China’s governance systems and capabilities. As the smallest unit of social governance, communities benefit from enhanced capacity and flexibility through integrated design, facilitating the establishment of convenient service networks that support the ‘15-min living circle’ concept [

23].

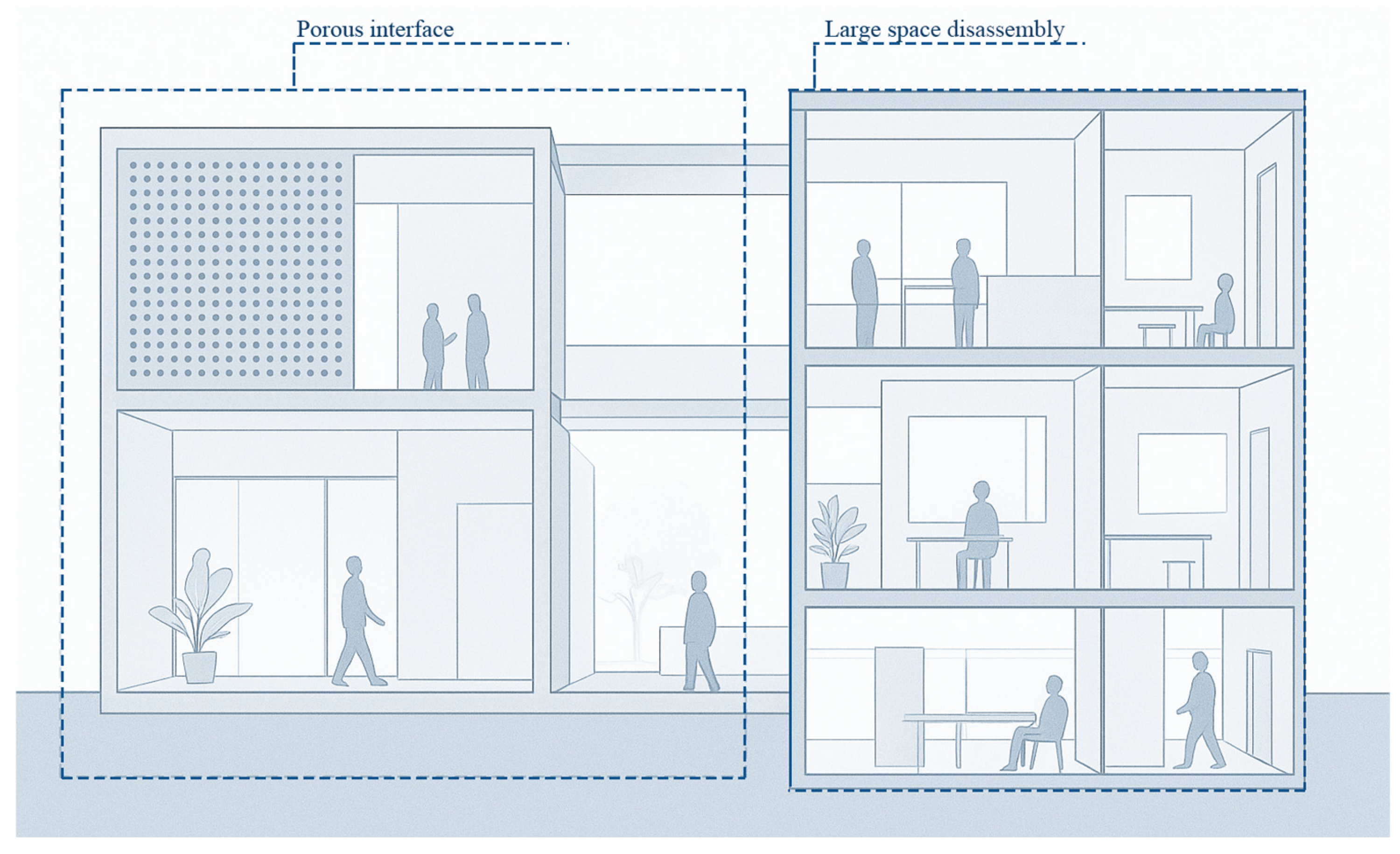

2.3. Spatial Permeability

Spatial Permeability proposes an adaptive design methodology within the framework of the “Supporting Structure Theory”, integrating porous interfaces with modular spatial decomposition. Its core objective lies in enhancing a building’s environmental resilience, spatial adaptability, and social interactivity by introducing permeability and variability simultaneously to both its exterior and interior. By deconstructing large-scale service spaces into smaller-scale units, the spatial arrangement becomes more flexible and user-friendly. These smaller units are then staggered and layered to form a ‘porous interface’, enabling spatial permeability, communication, and interoperability. The specific parameters of this design approach are detailed in

Table 1:

(1) “Porous” interface: Spaces are not entirely sealed or fragmented, but rather allow light, sightlines, air and activity to permeate and flow through porous interfaces, layered variations or scale divisions, thereby enhancing spatial openness and continuity. Brzezicki (2019) notes that ‘translucent facades’ represent a significant contemporary architectural trend balancing privacy and openness, achieving visual and environmental permeability through material porosity and layered construction [

24]. Oyedeji (2022) further proposes that building facades should be conceptualized as ‘ecological interfaces’, facilitating the reciprocal flow of energy, air, and social activity between space and environment [

25]. Regarding ventilation, empirical research by Shen et al. (2025) demonstrates that porous facades can significantly reduce wind pressure and improve the ventilation efficiency of double skin curtain walls [

26].

(2) Large-scale spatial decomposition: This approach aims to deconstruct expansive continuous spaces into independent, reconfigurable small-scale modular units. It achieves spatial flexibility and functional versatility while preserving overall continuity, aligning with Habraken’s theory of ‘separating structure from infill’. Leuven proposed the concept of ‘time-based architecture’, emphasizing that buildings should possess structurally stable frameworks with adaptable functions [

27]. Kendall & Teicher, in Open Building, note that integrating modularity with the supporting structure enables long-term renewal without altering the building’s fundamental framework [

28].

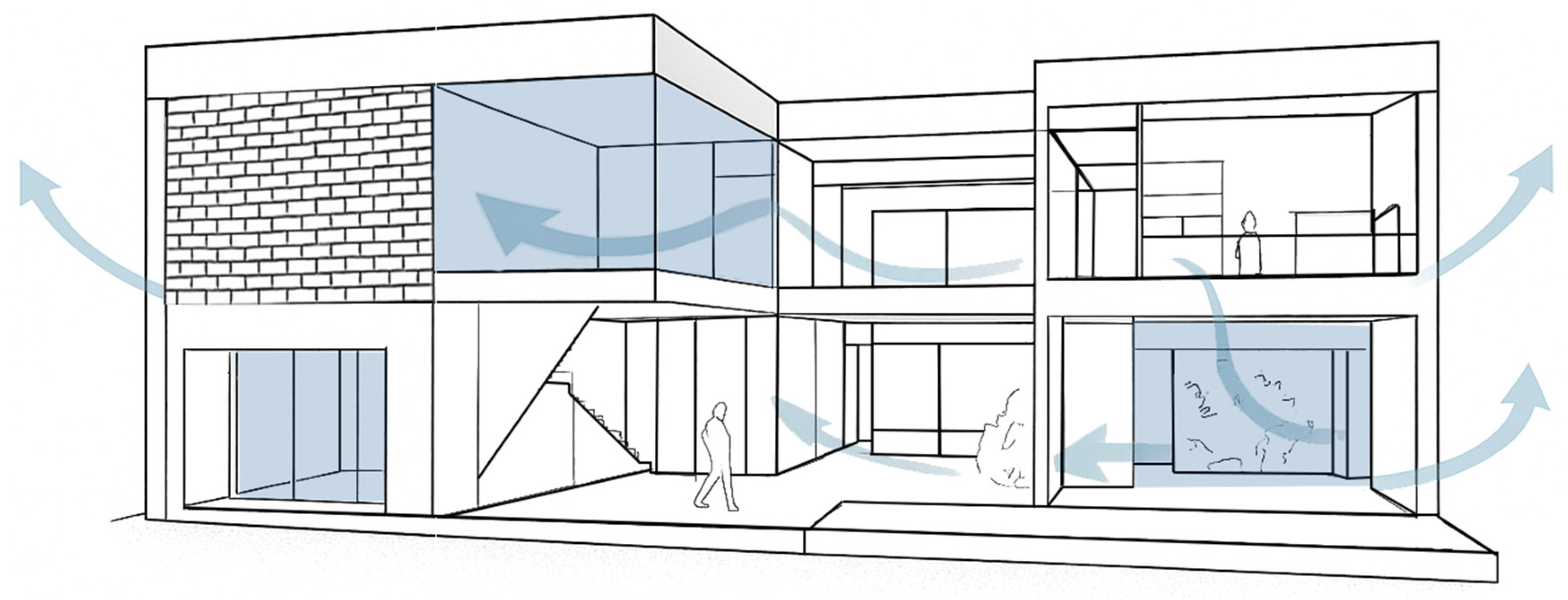

The coupling of permeability with modularity, combined with porous interfaces and the deconstruction of modular spaces, achieves dual-level adaptability: Physical Adaptability: The building forms a “breathing” system through permeable facades, optimizing ventilation and daylighting. Functional Adaptability: Modular layouts enable functional transitions and shifts in usage patterns without altering the structural framework. As illustrated in

Figure 4, these elements collectively constitute a dynamic spatial system under the ‘supporting structure-Infill System’s logic, enabling the building to maintain sustainable vitality and dynamic renewal capacity amidst societal and environmental shifts.

(3) Space Permeability: Space Permeability refers to breaking the enclosure of building interfaces and using design techniques and structural layouts to allow light, air, sightlines, and human activities to penetrate and flow, thereby enhancing the openness, continuity, and interactivity of space. Different from the traditional division of enclosed functional areas, space Permeability emphasizes the interaction and Permeability between the interior and exterior of space, promoting the formation of an organic connection between functional modules and between people and space. This design concept is often realized by using permeable interfaces (such as perforated walls, double facades, ventilation corridors, etc.) or through the interlacing and overlapping of space layouts. While enhancing the fluidity and permeability of the space, it also improves the interactivity and diversity of the space. Spatial permeability design is not only for the optimization of functional zoning but also to promote interaction between different functional areas. Through staggered layouts and the overlapping of functional modules, visual and circulation Permeability and interaction are formed. For example, multiple functional areas are connected by a shared atrium or corridor, so that each space is not only independent but also can interact with the surrounding spaces, enhancing the sociality and dynamism of the space. This design method enables the space to more flexibly meet the changing usage needs and at the same time, enhance the spatial experience.

2.4. Three-Dimensional Composite Spatial System

Guided by the concept of ‘spatial permeation’, vertical stratification and horizontal inter-weaving jointly constitute the composite logic of spatial organization within the community service center. The former achieves spatial continuity and interaction through the vertical layering and stacking of distinct functional units. The latter breaks the closed nature of spatial boundaries by interweaving and shifting functional zones across the plane, and by coupling this with the installation of semi-transparent interfaces, as illustrated in

Table 2. The combined action of these two approaches in both vertical and horizontal directions creates multidimensional pathways for light, airflow, and pedestrian circulation. This enhances the building’s spatial openness, continuity, and complexity, as illustrated in

Figure 5. That is, ‘Vertical Stratification + Horizontal Inter-weaving = The Composite Pathway for Spatial Permeability’. The former creates permeability in the three-dimensional plane, while the latter extends it across the horizontal plane. Together, they elevate the building’s spatial continuity, ventilation, and experiential diversity.

(1) Vertical stratification: Resolves functional conflicts whilst accommodating multifunctional integration and segregating noise levels and privacy requirements; vertical stratification achieves spatial continuity and interaction through the vertical layering of distinct functional units along the height dimension [

29].

(2) Horizontal interweaving: Promotes functional interaction and enhances spatial efficiency; for instance, Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion employs interwoven walls to construct spaces that not only fulfill diverse functional requirements but also offer users an enhanced spatial experience [

30], thereby improving spatial utilization and fostering serendipitous social encounters. This approach is frequently combined with spatial syntax, accessibility analysis, and behavioral observation to quantify the impact of staggered layouts on circulation patterns and congregational behavior [

31].

(3) Spatial Permeability: Breaking down enclosed interfaces to enhance visual and airflow connectivity, emphasizing the shift from “isolation” to “connection”: Strategies such as grilles, semi-transparent partitions, ventilated corridors, and atriums enable light, air currents, sightlines, and human activity to permeate and circulate between spatial units. This ensures functional differentiation while enhancing environmental connectivity and social dynamics [

32]. Spatial permeability serves both as a means to optimize environmental performance (daylighting, ventilation, thermal behavior) and as a strategy to shape social behavior (chance encounters, visual relationships).

3. Results

The construction site is located in Yicheng District, Zhumadian City, Henan Province. The building type is a community service center. The main purpose of the design is to provide a sustainable public building that is connected to the urban space. Based on the urban spatial structure around the construction site and the functional needs of community residents, the building functions and the social and cultural values that the building must possess are reasonably planned.

As shown in

Figure 6, in the design of the general plan, considering the surrounding environment of the site and the road grade, the entrances and exits of the site are first determined. The west side of the site is a city arterial road, and there is a green buffer zone that cannot be demolished. Therefore, the main entrance of the site is set on the south side, the secondary entrance on the north side, the main entrance of the building on the west side, and the secondary entrance on the east side. The southwest side of the site is open to the outside, and landscape steps are set up to correspond to the entrance square on the south side and provide a place for people to visit and rest. Since the north side of the site is a planned green space, functions such as catering and entertainment are set on the north side. According to the needs of the users, an outdoor activity square is set in the northeast corner of the site, making full use of the surrounding landscape for the activity and leisure places. The south side of the site is adjacent to the Yicheng District Government, so the exhibition-style spaces and the lecture hall are set on the south side of the site. In addition, the entrance of the underground garage is set on the north side of the site because the road adjacent to the north side of the site is a city branch road with a relatively low road grade.

3.1. Embodiment of the Support Body Theory

To construct a long-term building framework adaptable to social functional changes and avoid functional obsolescence, The case design divides the building structure into a fixed support structure and a replaceable infill body, and reserves a unified interface (structure, pipeline functional node) between the two to implement the design strategy of separating the “support body–infill body”, thereby enhancing the flexibility, maintainability and life-cycle value of the building in the time dimension. This can enhance the flexibility, maintainability, and life-cycle value of the building over time. This method combines modular assembly, standardized column grids and the concept of circular architecture. As shown in

Figure 7, its main contents and implementation key points are as follows:

(1) Fixed support structure

This design mainly reflects the fixed support structure from the following five aspects: 1. In the fixed column grid system, reinforced concrete is used as the long-term load-bearing system to ensure the safety and durability of the structure. A load-bearing frame is constructed by adopting regular and standardized column spacings (8 m × 8 m), thus providing “grid” support in terms of structure for the internal functional layout, and enabling the space to be reconfigured in the future without being restricted by the structure. 2. Integrated core tube: Elevators, staircases, pipe shafts, and equipment shafts are centrally arranged within the core tube of the building to ensure the stable operation of vertical transportation and electromechanical systems. Meanwhile, the peripheral space features a free layout, enhancing the flexibility of the peripheral infill. 3. Overhead and cantilever structures: Through long-span beams, truss structures, and cantilever beams, the main load-bearing structures are moved to both sides or the outer edges, and the central space is released for functional filling, thereby maximizing the variable space. 4. Foundation and structural levels of independence: Clearly distinguish between load-bearing structures and non-load-bearing components. Adopt a double-layer facade or a demountable curtain wall system, so that the service life of the supporting structure can be set to more than 50 years, while the infill can be replaced periodically (for example, every 5–15 years).

(2) Replaceable Infill System

Similarly, it is reflected in four aspects: 1. Use recyclable wooden structural supports and assemble internal partition walls with detachable panels (such as gypsum boards and wood veneers). Adopt modular assembly for easy decomposition. When the function changes, the partition walls can be quickly removed or reorganized. 2. Movable furniture and space units include furniture walls that can slide, fold, or rotate, sliding rail bookcases, movable storage modules, and folding partition walls. Making the furniture and partitions not only have functions but also play a role in space separation. Users can recombine them according to their usage needs without being fixed to the structural system. 3. The replaceable facade or skin system separates the building curtain wall and facade panels from the main structure and adopts the installation methods of slot type and hanging type, enabling the skin modules to be disassembled, replaced and updated during the operation period. 4. The modular system for the floor and ceiling is adopted. The floor uses an overhead floor system, with reserved space below for mechanical and electrical pipelines and data cable troughs. The ceiling is composed of modular ceiling panels (sound-absorbing panels and grille panels). This allows the ceiling modules to be replaced or adjusted according to functional areas, enabling faster overall construction and more convenient maintenance.

3.2. Functional Space Compounding

This study addresses the issues of scattered functions and inefficient space utilization in community service centers through functional three-dimensional superimposition and spatial boundary ablation. As shown in

Figure 8, in terms of building function layout, the first floor primarily accommodates dining and entertainment, convenience services, and some office areas; the second floor includes a gym, a multifunctional hall, and additional office spaces; the top floor is divided into a reading area, an exhibition area, and a youth activity zone. The first-floor centers around an atrium, with functional and circulation spaces arranged around it, such as dining and entertainment areas and convenience services. The west square serves as the main entrance, while the east and north sides act as secondary entrances, and a dedicated entrance is provided for the lecture hall on the south side. Office areas are located on the east side, separated from the main pedestrian flow to ensure a quiet and efficient working environment. Dining areas are situated on the north side to facilitate logistical organization while avoiding conflicts with pedestrian flow. Access to the second floor of the building is diverse, including internal vertical circulation facilities such as elevators, enclosed stairwells, and single-run stairs, as well as direct access via large external steps. The lecture hall in the southeast corner can be accessed directly from the outdoor steps. On the top floor, considering the need for a quiet environment, the north side is designated as a reading area, while the east side is planned for the youth activity center.

The functional spaces are arranged using the technique of “vertical stratification + horizontal staggering” to enhance the functional adaptability, spatial permeability, and richness of experience of the building. As shown in

Figure 9, the specific practices are as follows:

(1) Vertical stratification: in this design, spaces with different functions, natures, or user groups are distributed along the vertical axis to achieve hierarchical configuration of functions, separation of noise and privacy, and optimization of traffic flow diversion. For example, the basement floor is arranged for parking and equipment rooms: High noise, low lighting function; The first floor houses a coffee area, a lecture hall, and a community service center: Highly open and strongly interactive with the external streets; The second floor houses a fitness area, an exhibition hall and activity classrooms: semispan; The west side of the third floor is for reading: silence, Offices and meeting rooms on the north side of the third floor—Highly private. Such a “bottom-up” sequence, progressing from open to semi-open and then to private, and from high noise to low noise and then to quiet, forms a typical vertical hierarchical layout.

(2) Horizontal staggering: In the planar layout of the building, different functional or spatial units are arranged on the same floor plane through staggering, misalignment, and partial overlapping, creating visual and activity Permeability and interaction. For example, the reading area is connected to the children’s activity area through a semispan atrium, which not only achieves functional segmentation but also allows the two spaces to penetrate each other; The office area retreats backward to leave an activity platform. The part of the youth activity center above it is elevated, creating a connection between the upper and lower levels, allowing those on the upper level to view the activities on the lower level; The coffee shop and the fitness space are arranged in an “interlocking” layout through the public corridor to enhance the functional connection, These are horizontal staggering: not simply planar compartments, but a “dialogue between functions”.

Combining the two methods, a pattern of “spatial Permeability” is jointly constructed in both the three-dimensional (vertical) and planar (horizontal) dimensions.

3.3. Space Decomposition

After disassembling the large space into small-scale units, on the basis of the compounding of functional spaces, through four strategies of “functional zoning modularization”, “hierarchical superposition”, “staggered arrangement”, and “shared boundaries”, the building can maintain overall continuity while achieving higher variability and social interactivity, making the functions more flexible and the space use more comfortable. At the same time, it facilitates later replacement (which is consistent with the supporting structure theory).

(1) Functional zoning modularization: Divide different functions such as exhibitions, reading, fitness, and rest into standardized modular units, so that each module has relatively independent structural boundaries and functional labels. On the premise of a unified scale, interfaces, and structural nodes, these modules can be freely combined, replaced, or reconfigured. As shown in

Figure 10, in the fitness space on the second floor, several “functional boxes” can be preset, including the aerobic area, yoga area, leisure area, communication area, etc. Each box can be individually removed, replaced or repositioned within the support structure.

(2) Shared boundary: Similarly, if modules are completely separated by solid walls, it will instead weaken the overall coherence and interactivity. Therefore, in this case, the boundaries are shared or overlapped through means such as atriums, corridors, semi-open platforms, glass partitions, and vegetation walls, so that the modules are not completely isolated at the boundaries. As shown in

Figure 9, after splitting the modules in the reading hall, a shared atrium and a corridor are left in the middle. This corridor not only serves each module but also acts as an intermediary for the sightlines, activities, and circulation routes of multiple modules.

(3) Hierarchical superposition: In addition to modularization, embedding a “box-in-box” structure and setting mezzanines within a largescale volume can further enrich the spatial experience and usage hierarchy. Create multilevel and multifunctional secondary spaces within the main space through nesting. As shown in

Figure 11, by embedding the office area into the exhibition space, a closed block is independently embedded inside the large space of the original building, creating a space within a space. This not only enables the creation of good functional zoning but also enriches the spatial hierarchy and experience, making the functions of the large space more diverse.

(4) Spatial Staggering: After disassembling the large space, to enhance the structural sense and dynamic experience of the functional modules, in this case, horizontal misalignment and vertical overlapping arrangement methods are used. Stagger the functional modules on the plane and connect them with “skip floors” or “voids” in height. This makes the circulation route changeable and the line of sight penetrable when moving from one module to another. As shown in

Figure 9, the exhibition hall on the second floor extends forward, while the lecture hall on the first floor is set back. The communication area and the large staircase are placed under the overhead floor of the exhibition hall and connected by stairs.

3.4. Porous Interface

In the building interfaces (walls, facades, partitions), permeable structures are introduced to form spaces that allow light, air, sightlines, or human activities to “penetrate”, as shown in

Figure 12. This is basically achieved through the following four methods:

(1) Hollowed-out wall, Grille wall: In this case, by using materials and structural forms such as perforated metal panels, wooden grilles, and brick-holed walls, the wall surface visually presents a “ semi-transparent “ state. For example, using wooden grille screens on the facade of the exhibition space allows natural outdoor light and air to penetrate while maintaining a certain degree of privacy. At the same time, adjust the size, density, and arrangement rhythm of the grilles according to functional requirements to regulate the degree of line-of-sight Permeability, light Permeability, and air circulation.

(2) Ventilation corridors, open atriums: Set up shared atriums, corridors, and void walkways, etc., so that the space as an “interface” is not only a partition but also a passage for “transition” and “Permeability”. For example, both sides of the atrium are separated from the functional rooms by grilles or glass partitions, but the connection of sightlines and light is retained; Set up a landscape staircase and platform that passes through the second floor from the first floor to the roof, allowing the line of sight to penetrate between floors and the airflow to rise, These spaces together form nodes for air circulation, natural lighting, and interpersonal interaction.

(3) Double-skin facade: A double-layer structure is adopted in the facade system. The outer layer consists of sun shading grilles, perforated panels, and wooden grilles; the inner layer is a glass curtain wall or high-performance glass. For example, perforated metal panels are used on the exterior facade of the lecture hall for shading and decoration. At the same time, they cooperate with the glass wall behind to form a structure of “transparent outside—blocked inside—air layer”, thereby promoting ventilation. An air buffer cavity is formed between the two layers, which can play a role in sun shading, ventilation, lighting, thermal control, etc. When the direct sunlight is strong, the curved perforated metal plate can control the direct light and reduce glare. At the same time, the inner-layer glass and the buffer cavity dissipate heat through natural ventilation.

(4) Movable partition: In indoor or semi-outdoor spaces, through components such as sliding doors, folding screens, glass partitions, movable furniture, and walls, an elastic layout with “interfaces that can be both separated and permeable” is established. For example, the youth activity hall is divided into two classrooms and a communication hall by sliding glass walls. When large-scale activities need to be held, the sliding doors are opened, making the space transparent with the line of sight and circulation path connected. Usually, the doors are closed to achieve sound insulation, privacy, and functional zoning.

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison Between Plot Ratio and Demolition and Renovation Losses

In this case, the support structure theory is used as the main framework, dividing the building’s fixed supporting structure and replaceable infill into two parts. The core commonality between the Supports Theory and modular construction lies in their shared design logic: “permanent structure, variable function”. Therefore, through existing research on modular buildings, the modular structure can be compared with the traditional structural system. Starting from the two aspects of floor area ratio and demolition and renovation losses, the advantages of the supporting structure can be illustrated:

(1) Although the supporting structure and the modular structure have different origins, they are highly consistent in terms of architectural adaptability and sustainable design concepts. In this case, the advantages of modularity included in the “support structure–Infill System” structure are: 1. Divide the building into the long-term stable “main structure” (support structure–main module) and the replaceable and reconfigurable “filling part” (functional module–internal unit) to achieve flexible adjustment of the space. 2. A replaceable and updatable component system can prevent the entire building from being scrapped due to functional changes, enabling the building to continuously adapt to social and functional updates. 3. By separating the structure from the function, when the building is renovated or updated, only partial replacement is required, thus reducing resource waste and downtime and lowering the “demolition and renovation loss rate”.

Therefore, the advantages of the supporting structure can be illustrated by comparing the demolition and renovation losses between modular buildings and traditional buildings. The following will conduct a comparative analysis from three aspects. As shown in

Table 3, from the perspective of “demolition and renovation losses”, the supporting structure building theoretically has more advantages: that is, at the time of demolition and renovation or at the end of the life cycle, its resource waste and replacement cost are lower than those of traditional buildings: 1. It can effectively reduce construction waste and demolition waste. The basic concept of modular construction in supporting-body buildings is to manufacture building modules off-site and then assemble them on-site. This approach greatly reduces the amount of construction waste generated. According to a study by the Waste and Resources Action Programme (WRAP), off-site construction can reduce waste to 1.8%. In the context of traditional demolition, as pointed out by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the waste generated from demolition accounts for more than 90% of the total construction and development waste [

33]. The comparison of these two sets of data implies that the “support structure–Infill System” structure has a potentially lower loss ratio in terms of “demolition waste”. 2. Detachable and highly reusable: After modularizing the components of the fixed support structure and the replaceable functional space, the structural components can often be prefabricated in the factory, featuring strong standardization and Demount ability. Moreover, at the end of the life cycle, “module reuse” or “relocation” can be considered instead of just complete demolition. For example, a study on modular timber structures points out that in the “End-of-life” phase (C1–C4), modular structures have the design advantage of being disassembled, while in the corresponding phase of traditional buildings, it is often just demolition + waste disposal [

34]. This approach helps to reduce the losses caused by the “structural demolition requirement”. In other words, it reduces the resource losses, waste, and replacement costs associated with “demolition and renovation”. 3. Lower waste of materials and components and more precise manufacturing: In the “support structure–Infill System” building structure, building components are basically prefabricated in the factory. While standardizing the dimensions of building components, the assembly is also more precise, thus reducing the possibility of on-site adjustment, waste, and changes. For example, some studies have pointed out that modular buildings perform better than traditional methods in terms of material waste, waste transportation, on-site transportation, etc. [

35]. Although this study is not entirely focused on the renovation and demolition stage, from the perspective of the end of the life cycle, reducing waste in the initial construction stage will also reduce losses in the renovation and demolition stage.

(2) The floor area ratio (total floor area/land area) can serve as a key indicator for measuring development intensity, spatial utilization efficiency, and potential profitability. In the traditional planning and layout, traffic flow lines (elevators, evacuation passages, corridors), building setbacks, and structural spans (beam-column systems) often lead to the occupation of a part of the effective space. For example, if larger traffic spaces, relatively wide corridors, larger beam depths, or column grid spacings are configured to meet requirements such as fire protection, safe evacuation, natural lighting, and ventilation, the available area will decrease, thereby reducing the FAR (when the land area is fixed). Therefore, the effective space stacking efficiency of traditional structures may be relatively low. In contrast, the layered staggered or three-dimensional modular systems (such as modular rooms and stackable modules) in the “support–filler” structure usually can: Shorten the traffic flow lines, optimize the horizontal and vertical movement lines, so as to reduce the proportion of corridors and public transportation spaces; The separation of the “support structure–Infill System” makes the structure more regular and the panels more standardized, thus reducing the loss of clear headroom of beams and columns and the loss of structural depth. Therefore, a hierarchical staggered or three-dimensional modular system can usually make the structure more compact, minimize the waste of traffic flow lines, and thus increase the effective plot ratio. From the perspective of manufacturing and assembly, the modular structure contained in the “support structure–Infill System” structure may also support a larger clear height, less structural interference, and a more flexible layout, thereby further increasing the usable area [

36].

By comparing the two design schemes, under the condition of the same land area, use the floor area ratio calculation formula to compare the floor area ratios and illustrate their advantages and disadvantages. A hierarchical and staggered layout is adopted: the total building area is 14,500 m2, and the land area is 16,700.54 m2: Comparative calculation reveals a significant efficiency gain: the proposed design achieves an FAR of 0.86, whereas the traditional layout yields an FAR of 0.71. This represents an increase of approximately 0.15, validating the spatial efficiency of the vertical stratification strategy. This efficiency improvement not only enhances the space utilization rate but also partially offsets the initial cost of modular construction.

4.2. Economic and Life-Cycle Verification

Life-Cycle Cost Analysis (LCCA) is an important method for evaluating the economic benefits of a building throughout its entire life cycle, from planning, construction, and use to decommissioning. It considers not only the initial investment but also the comprehensive benefits of operation, maintenance, depreciation, and residual value. Compared with traditional buildings, in the “support structure–infill body” structure, although standardization and modularization have potential savings (up to 20%), there may also be a cost premium [

36]. It mainly stems from the costs of factory prefabrication, module transportation, and high-precision assembly. However, this part of the cost can be offset by energy savings and maintenance savings in the long-term operation. Research shows that the modular system in the “support structure–Infill System” structure can shorten the construction period by about 20–40%, enable faster capital turnover, and allow for earlier commissioning, thereby reducing financing costs and interest payments [

36]. In addition, the mass production of standardized components increases the material utilization rate by 10–12%, reducing waste and rework.

During the construction process of the “support structure–Infill System” building, investing in higher-quality materials, energy-efficient systems, and modular designs may require a higher initial investment. However, in the long run, it can significantly reduce maintenance costs, repair frequency, and energy consumption. Life cycle cost analysis typically shows that compared with traditional buildings, costs can be reduced by 15% to 25% [

37]. Traditional buildings usually require large-scale repairs around the 15th to 20th year. However, the “supporting structure–infill structure” can achieve “functional reconstruction” by replacing modules, thus avoiding overall shutdown.

The other is the environmental impact (recycling and carbon emissions): At the sustainability level, compared with traditional building practices, the greatest advantage of the “support–infill” building lies in reducing the rework rate, minimizing construction waste, and achieving the goal of carbon emission reduction [

38]. Due to the high prefabrication rate, construction waste is reduced by approximately 60–70%, and transportation energy consumption is decreased by about 30% [

39]. The supporting structure theory separates the fixed structure from the infill, allowing the infill to be replaced without changing the building structure. The demountability of the infill modules enables the components to be recycled after their service life, creating a potential path for “zero building waste”.

Due to the short construction period of “support structure–Infill System” buildings, the on-site machinery usage time is reduced, and the indirect carbon emissions also decline significantly. For example, multiple studies have shown that the emissions of the modular building method are lower than those of the traditional building method. Compared with on-site construction, modular buildings can reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 46.9% [

40]. In addition, the modular construction in the “support structure–Infill System” structure relies on off-site prefabrication, so the usage of on-site equipment and machinery is also reduced. For example, these modular materials are precisely cut in the factory first. This practice reduces the need for on-site machinery such as saws and grinders, thereby reducing waste. This practice reduces the need for on-site machinery such as saws and grinders, thereby reducing waste. At the same time, it minimizes the energy and emissions required to operate these tools, reduces the transportation of waste materials, and further lowers the greenhouse gas emissions generated during the construction process [

41]. In addition, industrialized production enables more precise material sorting and energy consumption monitoring, providing a feasible technical path for the realization of carbon-neutral buildings.

It can be seen from the comparison and summary of the costs and construction periods between the support-structure buildings and traditional buildings in

Table 4. The “support structure–Infill System” structure can effectively shorten the construction period and reduce the whole-life-cycle cost of the building. Although there will be a cost premium, in the long run, it can be offset by energy savings and maintenance savings; Moreover, in terms of low carbon: 1. It can reduce greenhouse gas emissions during the construction phase. 2. Due to the characteristics of unified prefabrication in the factory, construction waste can be significantly reduced. 3. Due to the separation of the fixed support and the replaceable filler, the modules can be partially replaced, which reduces the loss of decomposition and modification while achieving “functional reconstruction”.

Finally, it is a summary of the discussion section. Through comparative analysis, this study compares the traditional building model with the building scheme after applying the “support–infill” theoretical framework, and specifically conducts the following analyses supported by statistics and data:

- (1)

Comparison of building FAR

Research shows that after adopting the “support–filler” structure, the floor area ratio has increased by approximately 0.15. Through the design of vertical stratification and horizontal dislocation, buildings can more effectively integrate more multi-functional spaces within a limited land area, thereby effectively improving the land use efficiency.

- (2)

Life Cycle Cost Analysis (LCCA)

Statistical data shows that compared with traditional buildings, buildings adopting modular design and removable fillers can reduce the total cost by about 15–25% over their life cycle. This is mainly reflected in the shortening of the construction period, the reduction in material waste, and the significant decrease in later maintenance costs.

- (3)

Waste reduction and carbon emission control

Through the adoption of modular design, research shows that construction waste can be reduced by 60–70%. In addition, due to the high-precision production of modular components, the waste in the on-site construction process is significantly reduced, thus helping to reduce carbon emissions throughout the building’s life cycle.

5. Conclusions

This paper takes the Supports Theory as the core framework. On this basis, by combining “space Permeability” and the “composite space system”, a comprehensive design path that adapts to the changes in social functions and the requirements of life-cycle management is proposed from three aspects: structural variability, spatial complexity, and architectural resilience. A sustainable architectural design method system for community service centers is constructed. Research shows the following:

(1) The separation mechanism of support structure and infill structure can effectively extend the building’s life cycle. Through the demarcation of the fixed support structure and the replaceable Infill System, the building achieves flexible adaptability in the time dimension, avoids functional obsolescence, and supports future functional replacement and space reuse. Compared with traditional building structures, it can save 15% to 25% of the life-cycle cost and effectively reduce carbon emissions. For example, in on-site construction, it can reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 46.9%.

(2) The vertically stratified and horizontally interlaced spatial composite layout significantly enhances the building’s spatial utilization efficiency and social interaction potential. Compared with the traditional building model, the plot ratio can be increased by 0.15. The overlapping and staggering of multi-dimensional spaces not only optimize the functional organization and save the land area but also promote communication among different groups within the community, enhancing the social cohesion and usage vitality of the building.

(3) Spatial Permeability and porous interface design demonstrate advantages in both environmental performance and social behavior. For example, by introducing semi-transparent facades, shared atriums, and movable partitions, buildings achieve multi-dimensional connectivity of light, air flow, and sightlines, enhancing natural ventilation and lighting performance, and at the same time creating an open and shared community spatial atmosphere.

Through the application of this method framework, the mixed-function requirements of community service centers have been addressed, and the policies for low-carbon buildings have been responded to. It provides a new theoretical framework and practical path for dealing with the challenges of functional diversification and sustainable development in high-density urban environments. Meanwhile, this study also has some limitations.

Limitations and Future Work:

While this study establishes a robust theoretical framework for low-carbon functional integration, we acknowledge limitations regarding quantitative validation. Current findings rely on theoretical modeling and comparative calculations (e.g., FAR and waste reduction estimates).

Although the “support-core and infill” design framework proposed in this paper provides a theoretical basis and innovative approach for low-carbon design and functional integration in community service centers, we acknowledge the study’s limitations in data validation. Engineering research, especially when proposing new methods and frameworks, often faces significant challenges in verification. Due to the complexity of architectural design and the specific environmental conditions of each project, validation in practical applications usually requires longer timeframes and broader data support. Therefore, the contribution of this paper lies primarily in the proposal of the methodology and the exploration of design concepts. Future research will validate the effectiveness of these design frameworks through more extensive case studies, simulation analyses, and feedback from actual projects, further refining their application strategies. This limitation provides room for future work and lays the groundwork for more empirical research.

Although this study has made certain contributions, there are still some limitations. Although this study proposes a sustainable design framework based on the support theory and composite space organization, the analysis still lacks quantitative verification supported by Building Information Modeling (BIM). Future research will prioritize BIM-driven simulations—specifically Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) for ventilation and daylighting analysis—to rigorously quantify the environmental performance benefits proposed in this framework. In the section evaluating spatial flexibility, the ergonomics or human behavior analysis of the system is not included. Without users’ physiological and behavioral data, such as movement patterns, activity comfort, crowd density tolerance, and accessibility indicators, the adaptability and usability of the composite spatial system cannot be comprehensively verified. Integrating ergonomic simulation tools, agent-based behavioral models, and post-occupancy evaluation (POE) in subsequent research will contribute to optimizing the functional adaptability of community service centers designed under the support–infill framework.