A Review of Inter-Modular Connections for Volumetric Cross-Laminated Timber Modular Buildings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Literature Review and Data Collection

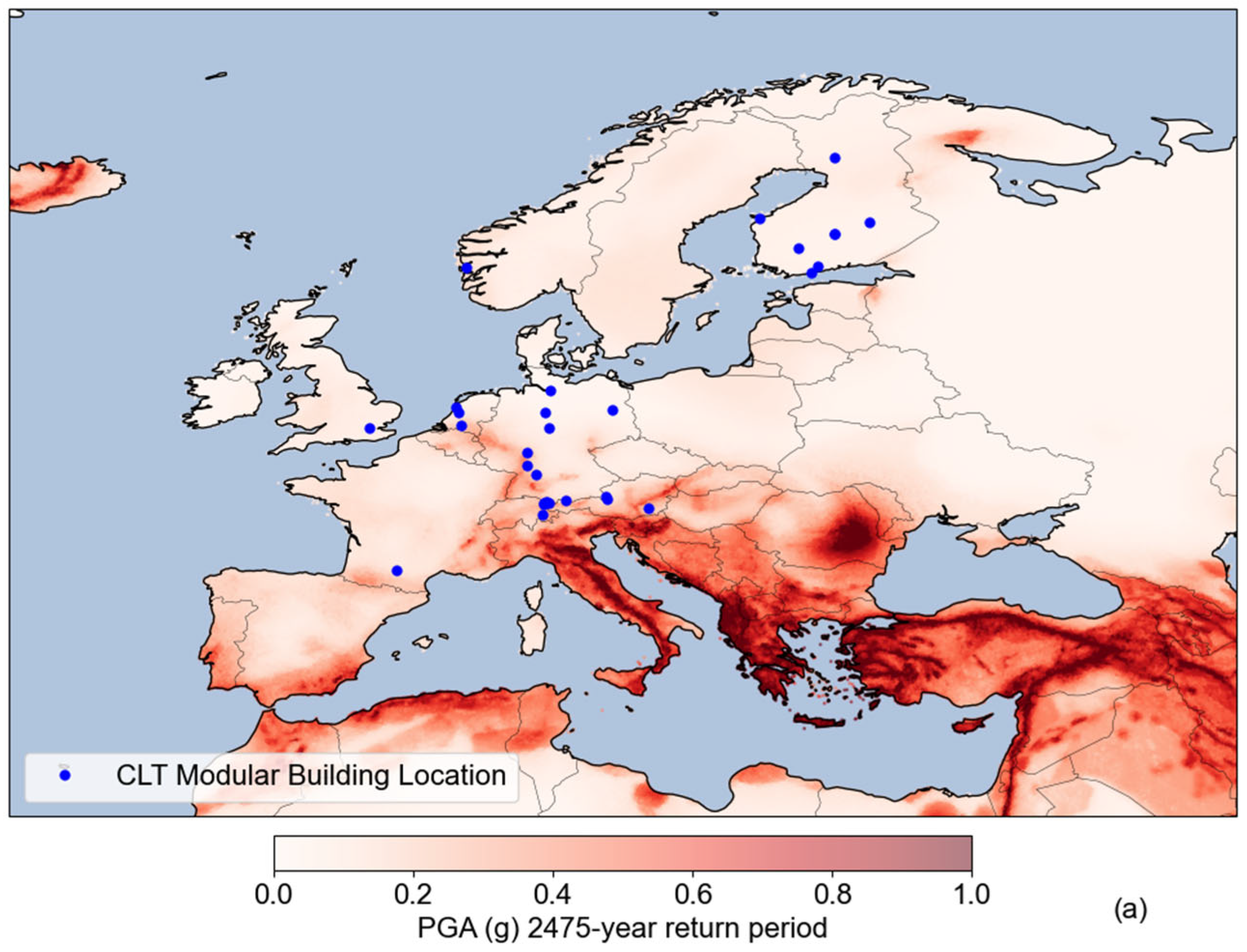

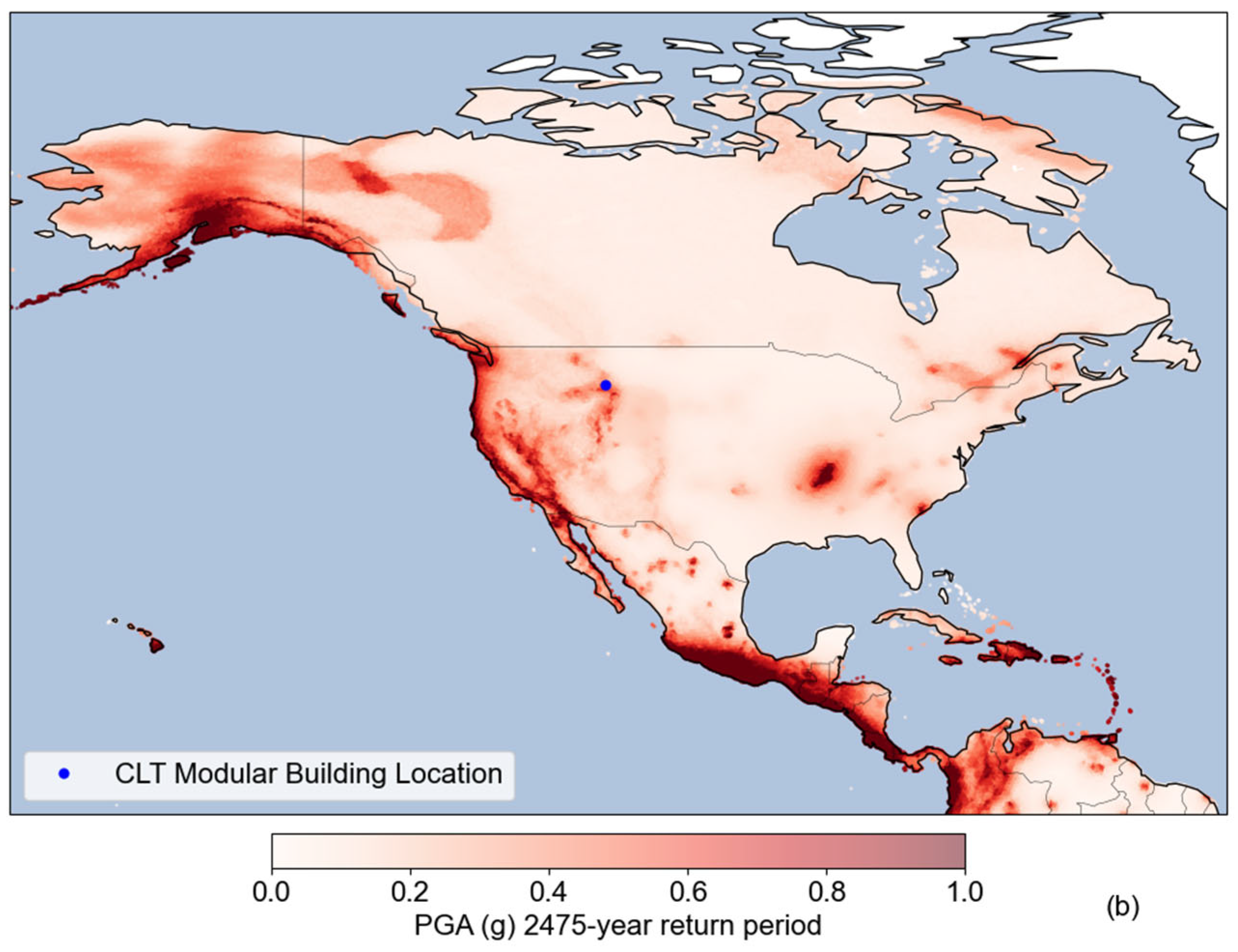

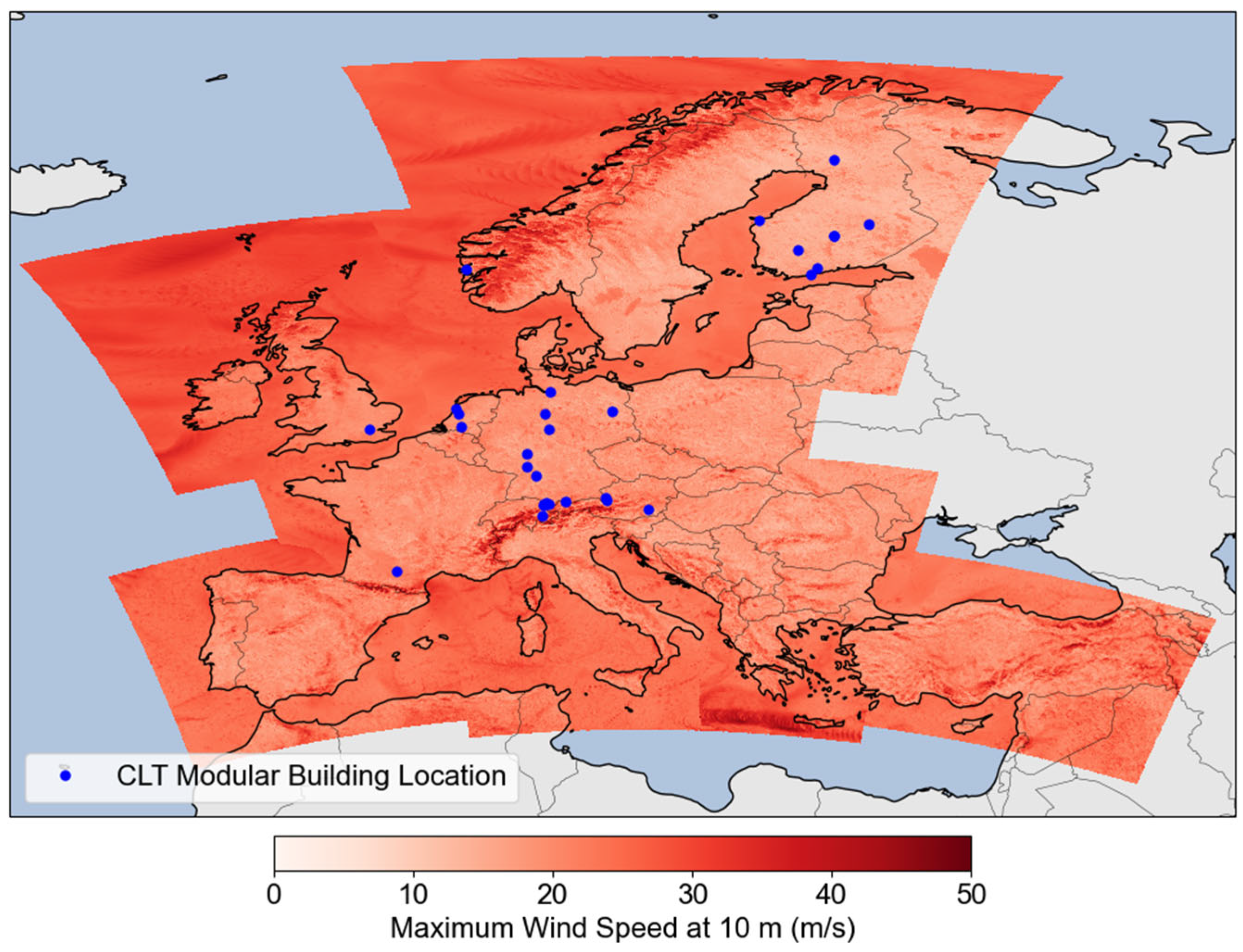

Seismic and Wind Hazard Definition

2.2. Evaluation of Inter-Modular Connections for CLT Modular Buildings

2.2.1. Structural Evaluation

2.2.2. Manufacturing Evaluation

2.2.3. Construction Evaluation

2.2.4. Experimental and Numerical Evaluation

3. Results

3.1. Structural Evaluation

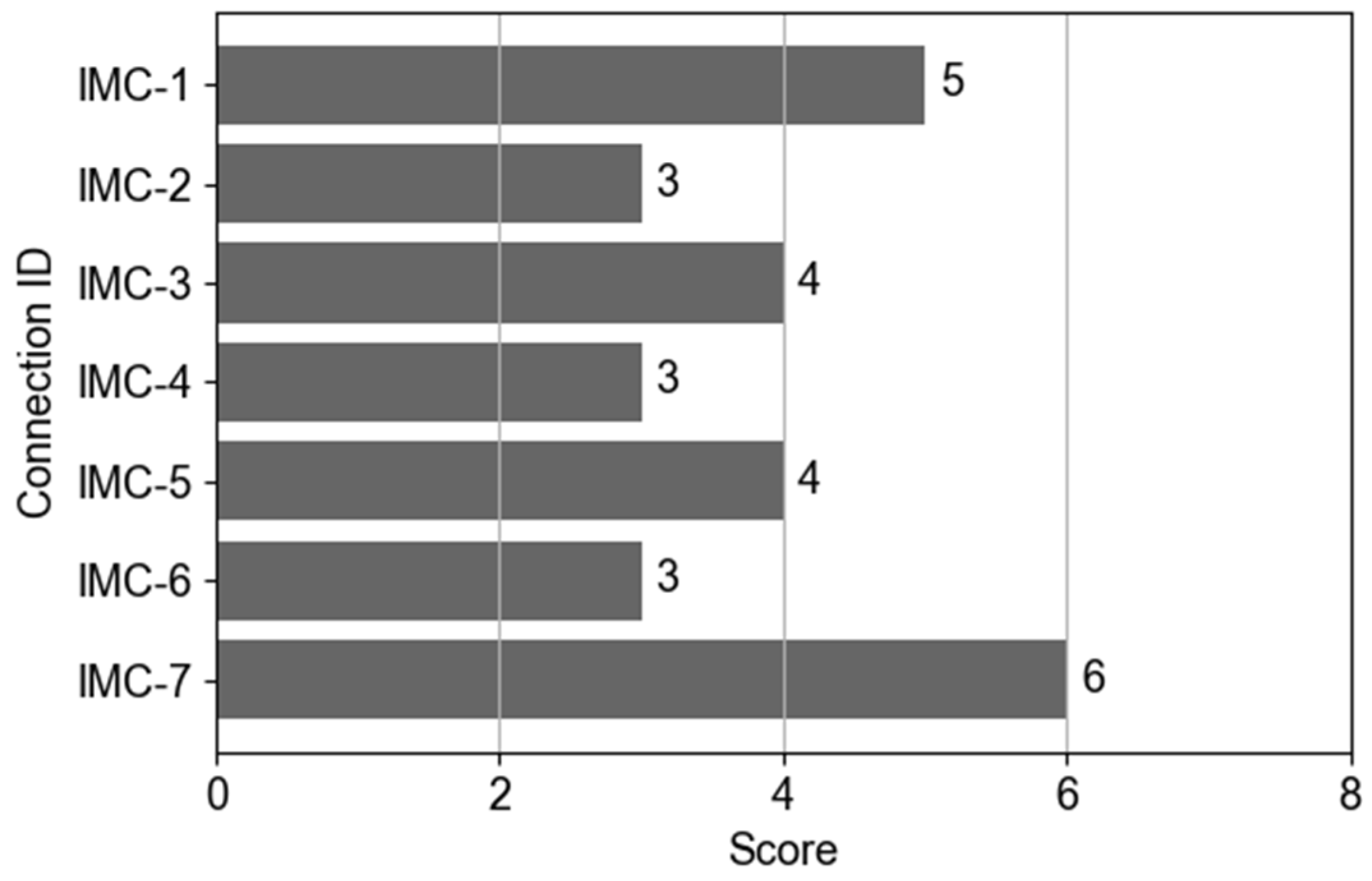

3.2. Manufacturing Evaluation

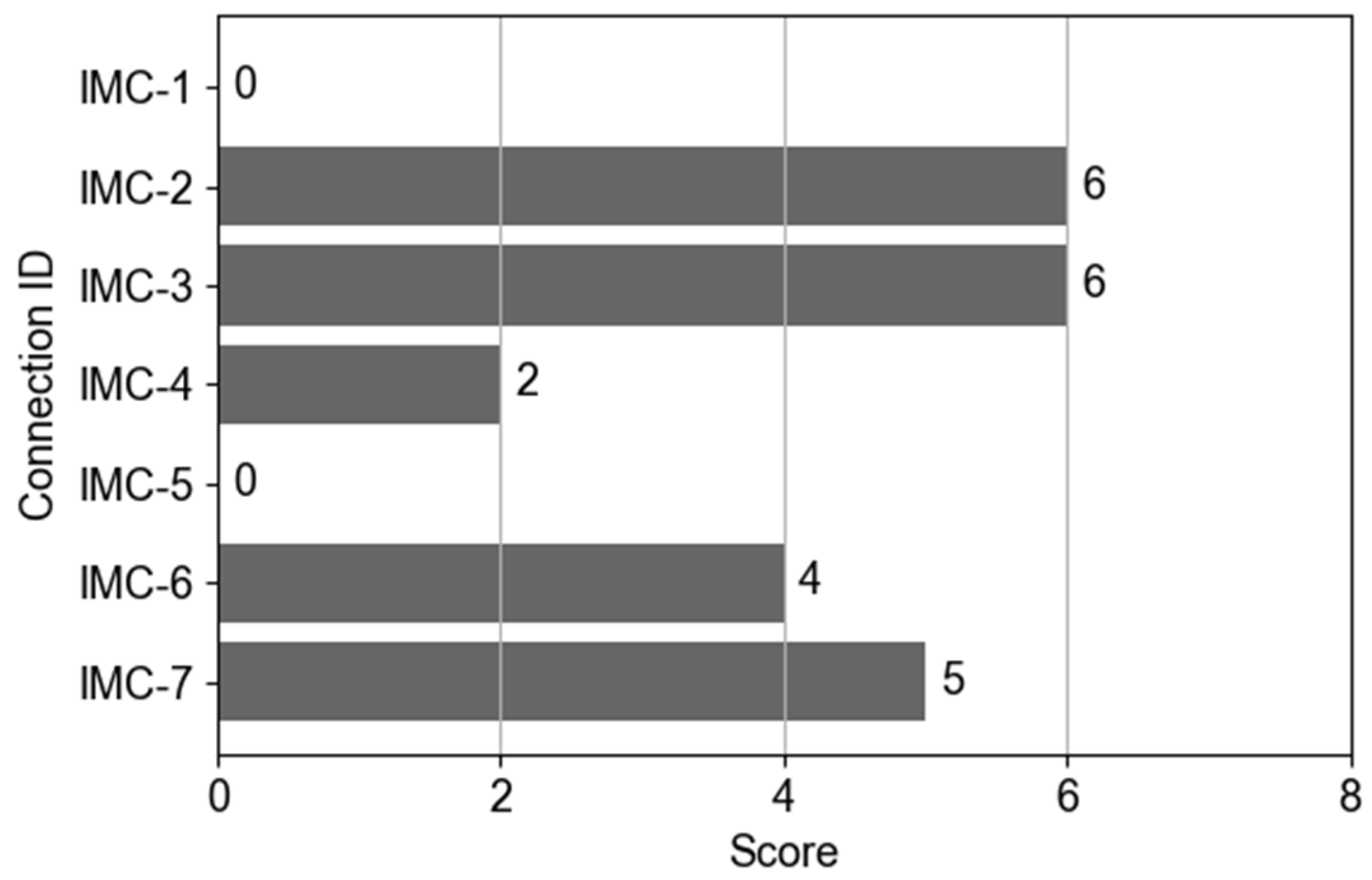

3.3. Construction Evaluation

3.4. Experimental and Numerical Evaluation

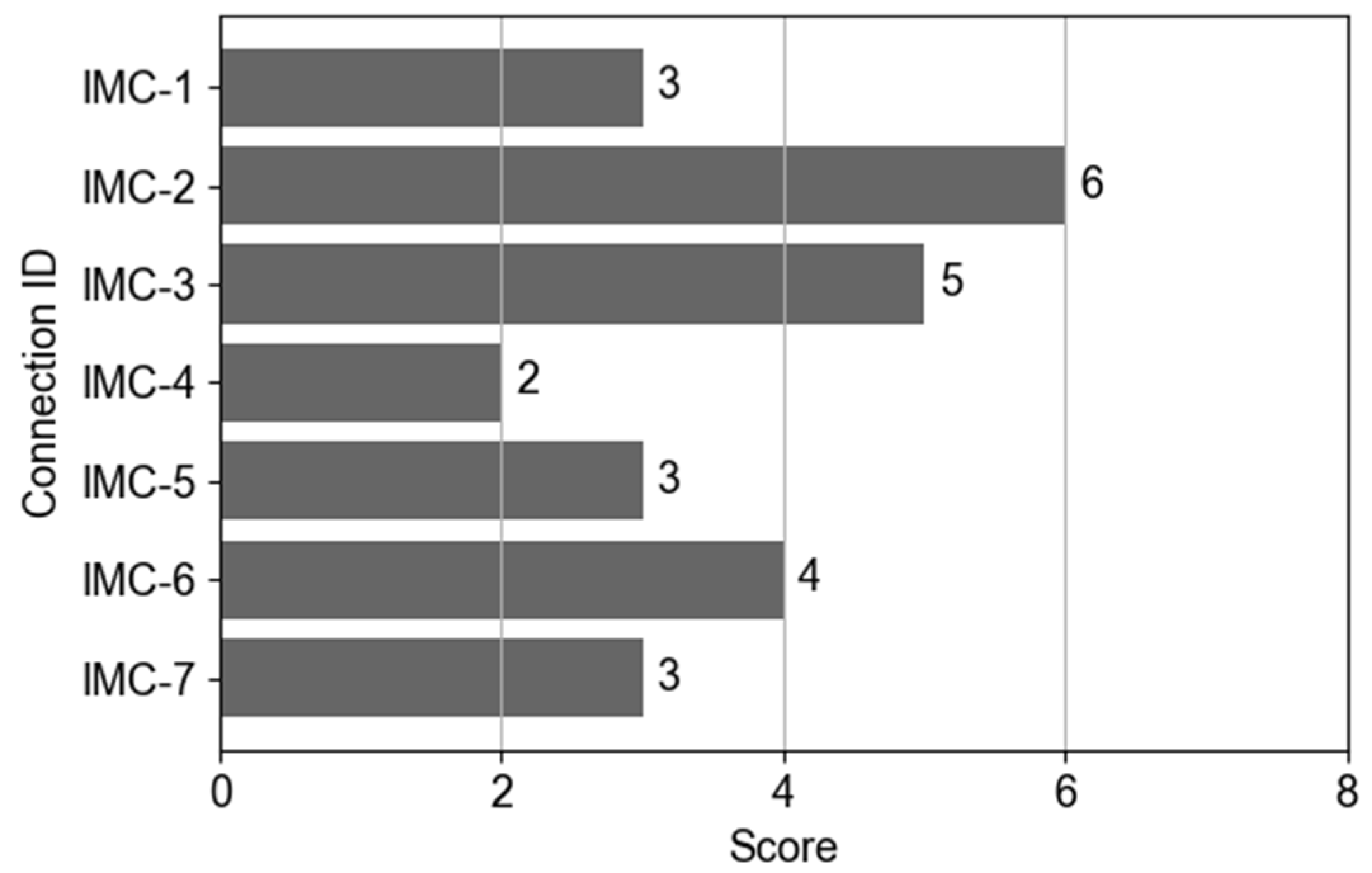

3.5. Overall Ranking

4. Discussion

5. Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sajid, Z.W.; Ullah, F.; Qayyum, S.; Masood, R. Climate Change Mitigation through Modular Construction. Smart Cities 2024, 7, 566–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association for Advancing Automation. The Effectiveness of Robotic Technologies in Construction and Infrastructure Development. Available online: https://www.automate.org/robotics/news/the-effectiveness-of-robotic-technologies-in-construction-and-infrastructure-development-72 (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Lim, Y.-W.; Ling, P.C.H.; Tan, C.S.; Chong, H.-Y.; Thurairajah, A. Planning and coordination of modular construction. Autom. Constr. 2022, 141, 104455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modular Building Institute. What Is Modular Construction? Available online: https://www.modular.org/what-is-modular-construction/#:~:text=Modular%20construction%20is%20a%20process%20in%20which,%E2%80%93%20but%20in%20about%20half%20the%20time.&text=Structurally%2C%20modular%2C%20prefabricated%20buildings%20are%20generally%20stronger,rigors%20of%20transportation%20and%20craning%20onto%20foundations (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Matson, S. Modular Construction Definition: A Look into Building Blocks at Scale. Available online: https://onekeyresources.milwaukeetool.com/en/what-is-modular-construction#:~:text=What%20Is%20Modular%20Construction?,are%20built%20exactly%20to%20spec (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- TWI. What Is a Modular Building? A Guide to Modular Construction. Available online: https://www.twi-global.com/technical-knowledge/faqs/what-is-a-modular-building#:~:text=Modular%20construction%20is%20a%20process%20where%20a,of%20different%20building%20types%20and%20floor%20plans (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Carvalho, L.F.; Jorge, L.F.C.; Jerónimo, R. Plug-and-Play Multistory Mass Timber Buildings: Achievements and Potentials. J. Archit. Eng. 2020, 26, 04020011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, R.Z.C.; Looi, D.T.W.; Tsang, H.; Wilson, J.L. A preliminary design tool for volumetric buildings. Struct. Des. Tall Build 2022, 31, e1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J. Design for Modular Construction: An Introduction for Architects; Building Green; The American Institute of Architects: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Whole Building Design Guide. Off-Site and Modular Construction Explained. Available online: https://www.wbdg.org/resources/site-and-modular-construction-explained (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Tenório, M.; Ferreira, R.; Belafonte, V.; Sousa, F.; Meireis, C.; Fontes, M.; Vale, I.; Gomes, A.; Alves, R.; Silva, S.M.; et al. Contemporary Strategies for the Structural Design of Multi-Story Modular Timber Buildings: A Comprehensive Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncheva, T.; Bradley, F.F. A comparison between Volumetric Timber Manufacturing Strategies in the UK and mainland Europe. In 2016 MOC Summit: Edmonton, Canada, Proceedings of the 2016 Modular and Offsite Construction (MOC) Summit, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 29 September–1 October 2016; MOC: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forum, W.E. How Modular Construction Drives Productivity, Circularity and the Convergence of Industries. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/01/modular-construction-productivity-circularity/ (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Srisangeerthanan, S.; Hashemi, M.J.; Rajeev, P.; Gad, E.; Fernando, S. Review of performance requirements for inter-module connections in multi-story modular buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 28, 101087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajanayagam, H.; Poologanathan, K.; Gatheeshgar, P.; Varelis, G.E.; Sherlock, P.; Nagaratnam, B.; Hackney, P. A-State-Of-The-Art review on modular building connections. Structures 2021, 34, 1903–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University, M. Handbook for the Design of Modular Structures; Monash University: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins & Will. Designing for Volumetric Modular—A Framework for Product and System Evaluation. May 2024. Available online: https://issuu.com/perkinswillvan/docs/designing_for_volumetric_modular_a_framework_for_p (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Kavaliauskas, D.S. Modular element system in high-rise wooden buildings: Challenges, advantages and perspective. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Timber Construction Forum (IHF 2017), Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany, 6–8 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Abiri, B. Decision-Making for Cross-Laminated Timber Modular Construction Logistics Using Discrete Event Simulation. 2020. Available online: https://www.journalofindustrializedconstruction.com/index.php/mocs/article/view/117 (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- ANSI/APA PRG 320; Standard for Performance-Rated Cross-Laminated Timber. American National Standards Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Council, A.W. Manual for Engineered Wood Construction; American Wood Council: Leesburg, VA, USA, 2015; Available online: https://awc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/AWC-2015-Manual-1603.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- 2015 IBC; International Building Code. International Code Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2014.

- EN 16351:2015; Timber Structures—Cross Laminated Timber—Requirements. CEN-CENELEC Management Centre: Brussels, Belgium, 2015.

- Ilgın, H.E.; Karjalainen, M.; Mikkola, P. Views of Cross-Laminated Timber (CLT) Manufacturer Representatives around the World on CLT Practices and Its Future Outlook. Buildings 2023, 13, 2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LSW Architects. PathHouse. 2025. Available online: https://lswarchitects.com/projects/pathhouse/ (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Green Canopy NODE. Green Canopy NODE—Impact Report. 2022. Available online: https://www.greencanopynode.com/impact (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Ryder, Z. Green Canopy NODE. Available online: https://offsitebuilder.com/high-efficiency-clt-modular-homes/ (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Corfar, D.-A.; Tsavdaridis, K.D. A comprehensive review and classification of inter-module connections for hot-rolled steel modular building systems. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 50, 104006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, N.; Negrão, J.; Dias, A.; Guindos, P. Bibliometric Review of Prefabricated and Modular Timber Construction from 1990 to 2023: Evolution, Trends, and Current Challenges. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, S.; Riggio, M.; Jahedi, S.; Fischer, E.C.; Muszynski, L.; Luo, Z. A review of modular cross laminated timber construction: Implications for temporary housing in seismic areas. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 63, 105485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.; Villani, M.; Bayliss, K.; Brooks, C.; Chandrasekhar, S.; Chartier, T.; Chen, Y.-S.; Garcia-Pelaez, J.; Gee, R.; Styron, R. Global Seismic Hazard Map. Zenodo 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ER 1110-2-1806; Engineering and Design Earthquake Analysis, Evaluation, and Design for Civil Works Projects. Department of the Army: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- Witha, B.; Andrea, H.; Tija, S.; Martin, D.; Yasemin, E.; Elena, G.-B.; Fidel, G.-R.J.; Grégoire, L.; Jorge, N. WRF model sensitivity studies and specifications for the NEWA mesoscale wind atlas production runs. Zenodo 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Society of Civil Engineers. ASCE Hazard Tool. Available online: https://ascehazardtool.org/#lat=45.258758&lon=-111.31032&z=5&r=2&sc=0&sv=7-22&m=si&l=Wind&v=Wind (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- National Weather Service and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Wind Threat Description. Available online: https://www.weather.gov/mlb/seasonal_wind_threat (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- National Weather Service and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. Available online: https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/aboutsshws.php (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Srisangeerthanan, S.; Hashemi, M.J.; Rajeev, P.; Gad, E.; Fernando, S. Numerical study on the effects of diaphragm stiffness and strength on the seismic response of multi-story modular buildings. Eng. Struct. 2018, 163, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacey, A.W.; Chen, W.; Hao, H.; Bi, K. Structural response of modular buildings—An overview. J. Build. Eng. 2018, 16, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Lu, W. Facility layout design for modular construction manufacturing: A comparison based on simulation and optimization. Autom. Constr. 2023, 147, 104713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, H.-T.; Ngo, T.; Uy, B. A review on modular construction for high-rise buildings. Structures 2020, 28, 1265–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huß, W.; Kaufmann, M.; Merz, K. Building in Timber—Room Modules; DETAIL: Munich, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann Bausysteme. Available online: https://www.kaufmannbausysteme.at/en/reference-overview-modular/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Integrated Design Cubed, Modular Mass Timber by IDCUBED. A Significant Breakthrough. Better Buildings. Faster. Cheaper. Available online: https://www.idcubedmodular.com/ (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Oopeaa, Modular Timber Construction. 2025. Available online: https://oopeaa.com/research/modular-timber-construction/ (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Abrahamsen, M.R.B. World’s tallest timber building—14 storeys in Bergen. In Proceedings of the 21. Internationales Holzbau-Forum IHF 2015, Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany, 2–4 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. Tall Timber Center—The Mass Timber Database of CTBUH. Available online: https://talltimbercenter.com/buildings/all (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- WSP. The Art and Science of The Possible. Tall Timber: How High Can CLT Go? Available online: https://www.the-possible.com/clt-high-rise-building-tall-with-engineered-timber/ (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Tuure, A.; Ilgın, H. Space Efficiency in Finnish Mid-Rise Timber Apartment Buildings. Buildings 2023, 13, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuure, A.; Hirvilammi, T.; Ilgın, H.E.; Karjalainen, M. Finnish mid-rise timber apartment buildings: Architectural, structural, and constructional features. Archit. Res. Finl. 2024, 8, 88–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waugh Thistleton Architects. Watts Grove Groundbreaking Modular Housing. Available online: https://www.graphisoft.com/case-studies/waugh-thistleton-architects-watts-grove/ (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Alter, L. The Construction Revolution Continues as Cross-Laminated Timber Goes Modular. Available online: https://www.treehugger.com/construction-revolution-continues-cross-laminated-timber-goes-modular-4858141 (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- CDM Stravitec. Straviwood ModuLink Case Studies. Available online: https://cdm-stravitec.com/en-us/case-studies?f%5B0%5D=solution%3A313 (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- De Groot Vroomshoop. Wooden Residential Buildings Koelmalaan Alkmaar. Available online: https://degrootvroomshoop.nl/bouwsystemen/houten-woongebouwen-in-alkmaar/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- BouwendNederland. New Construction Campus Valkenvoortweg Waalwijk. Available online: https://www.bouwendnederland.nl/vereniging/regio-zuid/afdeling-brabant-mid-west/circulair-bouwen-afdeling-brabant-mid-west/nieuwbouw-campus-valkenvoortweg-waalwijk (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Koskimies, J. Inter-Module Connections in Multi-Storey Modular Timber Buildings; Aalto University: Espoo, Finland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Tsavdaridis, K.D. A novel limited-damage 3D-printed interlocking inter-module connection system for Cross Laminated Timber (CLT) volumetric structures. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Timber Engineering (WCTE 2023), Oslo, Norway, 19–22 June 2023; pp. 1192–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Tsavdaridis, K.D. Design for Seismic Resilient Cross Laminated Timber (CLT) Structures: A Review of Research, Novel Connections, Challenges and Opportunities. Buildings 2023, 13, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Tsavdaridis, K.D. Limited-damage 3D-printed interlocking connection for timber volumetric structures: Experimental validation and computational modelling. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 63, 105373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Innovative Interlocking Connection System for Medium-Rise Timber Modular Structures; The University of Leeds: Leeds, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Angeli, A.; Polastri, A.; Callegari, E.; Chiodega, M. Mechanical characterization of an innovative connection system for CLT structures. In Proceedings of the WCTE 2016 World Conference on Timber Engineering, Vienna, Austria, 22–25 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Polastri, A.; Giongo, I.; Piazza, M. An Innovative Connection System for Cross-Laminated Timber Structures. Struct. Eng. Int. 2017, 27, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polastri, A.; Giongo, I.; Angeli, A.; Brandner, R. Mechanical characterization of a pre-fabricated connection system for cross laminated timber structures in seismic regions. Eng. Struct. 2018, 167, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothoblaas. X-RAD Connection System. Available online: https://www.rothoblaas.com/products/fastening/brackets-and-plates/x-rad/x-rad (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Bhandari, S.; Jahedi, S.; Riggio, M.; Lech, M.; Luo, Z.; Polastri, A. CLT Modular low-rise buildings a DfMA approach for deployable structures. In Proceedings of the WCTE 2021 World Conference on Timber Engineering, Santiago, Chile, 9–12 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari, S.; Fischer, E.C.; Riggio, M.; Muszynski, L. Numerical assessment of In-plane behavior of multi-panel CLT shear walls for modular structures. Eng. Struct. 2023, 295, 116846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, S.; Fischer, E.C.; Riggio, M.; Muszynski, L.; Jahedi, S. Mechanical Characterization of Connections for Modular Cross-Laminated Timber Construction Using Underutilized Lumber. J. Struct. Eng. 2024, 150, 04023221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gijzen, R. Modular Cross-Laminated Timber Buildings. Delft University of Technology. 2017. Available online: https://repository.tudelft.nl/islandora/object/uuid%3Af687e2cc-86e1-442e-862a-2ceb382f7157 (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Vilguts, A.; Phillips, A.R.; Antonopoulos, C.; Griechen, D. Testing and modeling of CLT-to-CLT joints made using hardwood dowels and screws with varying spacing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 458, 139449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Lee, G.; Lam, F. Connections for Stackable Heavy Timber Modules in Midrise to Tall Wood Buildings; TEAM 2018-08; Timber Engineering Applied Mechanics: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stravitec, C.D. Straviwood Modulink Datasheet. Available online: https://cdm-stravitec.com/en-us/media/4374/download?attachment (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Stravitec, C.D. Straviwood ModuLink—Installation Manual. Available online: https://cdm-stravitec.com/en-us/media/4375/download?attachment (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Stravitec, C.D. Timber Construction Acoustical Solutions. Available online: https://cdm-stravitec.com/en-us/media/4180/download?attachment (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- WOOD.BE. Test Report 220986—Straviwood Modulink: Mechanical Evaluation; Test Report 220986_EN_CDM_J_230223Rp; Wood.Be: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sharafi, P.; Mortazavi, M.; Samali, B.; Ronagh, H. Interlocking system for enhancing the integrity of multi-storey modular buildings. Autom. Constr. 2018, 85, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedon, C.; Fragiacomo, M. Numerical analysis of timber-to-timber joints and composite beams with inclined self-tapping screws. Compos. Struct. 2019, 207, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 12512; Timber Structures—Test Methods—Cyclic Testing of Joints Made with Mechanical Fasteners. CEN-CENELEC Management Centre: Brussels, Belgium, 2001.

- EN 26891; Timber Structures—Joints Made with Mechanical Fasteners—General Principles for the Determination of Strength and Deformation Characteristics. CEN-CENELEC Management Centre: Brussels, Belgium, 1991.

- ASTM D5764; Standard Test Method for Evaluating Dowel-Bearing Strength of Wood and Wood-Based Products. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- ASTM E2126; Standard Test Methods for Cyclic (Reversed) Load Test for Shear Resistance of Vertical Elements of the Lateral Force Resisting Systems for Buildings. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- American Wood Council. Nds ® 2018 National Design Specification® for Wood Construction 2018. 2018. Available online: www.awc.org (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- ASCE/SEI 7-22; Minimum Design Loads and Associated Criteria for Buildings and Other Structures. ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 2021. [CrossRef]

- BS EN 1998-1:2004; CEN. Eurocode 8: Design of Structures for Earthquake Resistance, Part 1: General Rules, Seismic Actions and Rules for Buildings. BSI: London, UK, 2004.

- Gunawardena, T.; Ngo, T.; Priyan, M.; Lu, A.; Alfano, J. Structural performance under lateral loads of innovative prefabricated modular structures. In From Materials to Structures: Advancement through Innovation; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pasquale, J.; Innella, F.; Bai, Y. Structural Concept and Solution for Hybrid Modular Buildings with Removable Modules. J. Archit. Eng. 2020, 26, 04020032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, H.-T.; Ho, Q.V.; Li, W.; Ngo, T. Progressive collapse and robustness of modular high-rise buildings. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2023, 19, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, T.; Sato, M.; Nakashima, S.; Matsuda, M.; Isoda, H.; Kawai, N. A study on the collapse limit of clt panel construction based on static lateral loading tests. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Timber Engineering 2025, Brisbane, Australia, 22–26 June 2025; pp. 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Andersen, L.V.; Hudert, M.M. The Potential Contribution of Modular Volumetric Timber Buildings to Circular Construction: A State-of-the-Art Review Based on Literature and 60 Case Studies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurocode 1995-1-1 2004 A1; Eurocode 5: Design of Timber Structures–Part 1-1: General-Common Rules and Rules for Buildings. The European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2004.

- AS 1720.1-2010; Timber Structures. Part 1, Design Methods. 3rd ed. Standards Australia: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2011.

- Bhandari, S. Modular Cross Laminated Timber Structures Using Underutilized Ponderosa Pine; Oregon State University: Corvallis, OR, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, S.; Pan, W. Structural design of high-rise buildings using steel-framed modules: A case study in Hong Kong. Struct. Des. Tall Build 2020, 29, e1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, S.; Ryan, K.L.; Berman, J.W.; van de Lindt, J.W.; Pryor, S.; Huang, D.; Wichman, S.; Busch, A.; Roser, W.; Wynn, S.L.; et al. Shake-Table Testing of a Full-Scale 10-Story Resilient Mass Timber Building. J. Struct. Eng. 2024, 150, 04024183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanches, R.; Tao, J.; Fathieh, A.; Mercan, O. Investigation of the seismic performance of braced low-, mid- and high-rise modular steel building prototypes. Eng. Struct. 2021, 234, 111986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, S.; Pan, W. Progressive collapse mechanisms of multi-story steel-framed modular structures under module removal scenarios. Structures 2022, 46, 1119–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Module equivalent frame method for structural design of concrete high-rise modular buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 44, 103214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.-W.; Ding, Y.; Zong, L.; Pan, W.; Duan, Y.; Ping, T.-Y. Seismic behavior of high-rise modular buildings with simplified models of inter-module connections. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2024, 221, 108867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lei, Z.; Han, S.; Bouferguene, A.; Al-Hussein, M. Process-Oriented Framework to Improve Modular and Offsite Construction Manufacturing Performance. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Pan, W. Millimeter-level position control in modular construction using laser scanning and tolerance chain. Autom. Constr. 2025, 177, 106335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case | Range | Wind Speed (m/s) |

|---|---|---|

| Normal conditions | Non-threatening | minimum |

| Very low | <9 | |

| Low | 9–11 | |

| Moderate | 11–17.5 | |

| High | 17.5–25.5 | |

| Extreme | >25.5 | |

| Hurricane | Very dangerous | 33–42.5 |

| Extremely dangerous | 42.5–49 | |

| Devastating damage | 49–57.5 | |

| Catastrophic damage | 57.5–70 | |

| Total damage | >70 |

| Structural Metrics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Metric | Score | Description |

| VC | 0 | Does not provide vertical connectivity. |

| 1 | Provides vertical connectivity to prevent module uplift. | |

| HC | 0 | Does not provide horizontal connectivity. |

| 1 | Provides horizontal connectivity with axial and shear capacity. | |

| CR | 0 | Provides low or non-energy dissipation capacity, and the damage is localized in the timber elements. |

| 1 | Provides a moderate energy dissipation capacity, and an intermediate or low level of damage is identified in the surrounding timber elements. | |

| 2 | Provides good energy dissipation capacity, and limited or no damage is produced to surrounding timber elements. The connection can be replaced. | |

| DF | 0 | Limited design flexibility. Designed to be positioned at a specific location within the modular unit. |

| 1 | Moderate design flexibility. Requires modifications and can be adapted for use in any location within the building. | |

| 2 | Good design flexibility. The connection is standard for any location within the building. | |

| Manufacturing Metrics | ||

| Metric | Score | Description |

| CC | 0 | Requires the manufacture of a large number of parts with a complex geometry or a complex manufacturing process. The mass production of components might be time-consuming. |

| 1 | Moderate number of parts, with a regular geometry that does not require an intensive manufacturing process. The mass production of components requires moderate time operations. | |

| 2 | A small number of parts with simple and regular geometry without complex manufacturing processes. Mass production is simple, with minimal time-consuming operations. | |

| CI | 0 | Complex manufacturing processes required to integrate the connection components (e.g., welding). |

| 1 | Intermediate difficulty for integration of connection components (e.g., drilling, welding of small parts). | |

| 2 | Simple integration of connection components (e.g., fastening, labeling, aligning elements). | |

| IP | 0 | Rigorous installation process of the inter-modular connection in the modular units (e.g., welding components into embedded parts, fitting heavy components). |

| 1 | Intermediate difficulty for the installation of the inter-modular connection (e.g., drilling timber panels, fastening or screwing of components, laser cutting of panels). | |

| 2 | Simple installation of the inter-modular connections (e.g., fastening single elements, aligning components). | |

| Construction Metrics | ||

| Metric | Score | Description |

| DA | 0 | Complex construction methods, no self-aligning/self-locating features, a large number of tasks, difficult access, and complex tooling. |

| 1 | Intermediate difficulty for construction methods, self-aligning/self-locating features, moderate number of tasks, moderate access, and moderate tooling. | |

| 2 | Simple construction methods, efficient self-aligning/self-locating features, a small number of tasks, easy access, and simple tooling. | |

| DD | 0 | Difficult process required to disassemble, limited access. Requires additional work before reusing. |

| 1 | Intermediate difficulty to disassemble, a few parts of the modular unit may need to be replaced before reuse, with minimum access limitations. | |

| 2 | Easy to disassemble, the modular units can be immediately reused or require small adjustments, adequate access. | |

| TC | 0 | Limited tolerance control, the construction process requires corrections to fit the modules. |

| 1 | Intermediate tolerance control, the construction process requires minor adjustments or modular alignment to fit the modular units. | |

| 2 | Adequate tolerance control, the modular connections effectively handle the required adjustments during the construction process. | |

| Experimental and Numerical Metrics | ||

| Metric | Score | Description |

| CET | 0 | No experimental tests have been performed on any component of the inter-modular connection. |

| 1 | Monotonic or cyclic experimental tests have been performed over the components of the inter-modular connection. | |

| FSET | 0 | No experimental test at full scale has been performed with the inter-modular connection. |

| 1 | Monotonic or cyclic tests at full scale have been performed with the inter-modular connection. | |

| NME | 0 | The connection has not been numerically simulated. |

| 1 | An elastic numerical model of the inter-modular connection has been developed to simulate its behavior. | |

| 2 | A nonlinear numerical model of the inter-modular connection has been developed and validated against experimental test results. | |

| AMD | 0 | No analytical model has been developed for the inter-modular connection. |

| 1 | An analytical model has been developed to simplify the design of the modular building. | |

| Building Name | City, Country | Completion Year | # Stories | # Modules | Seismic Hazard | Wind Hazard | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMW Alpenhotel Ammerwald | Ammerwald, Austria | 2009 | 5 (concrete first two stories) | 96 | Moderate | High | [7,41,42] |

| Senior Citizens’ Home in Hallein | Hallein, Austria | 2013 | 5 (concrete ground floor) | 136 | Moderate | High | [41] |

| Student Hostel in Heidelberg | Heidelberg, Germany | 2013 | 5 | 265 | High | Moderate | [7,41] |

| Moxy Hotels | Multiple countries | 2014 | 7 | 200 | - | - | [7] |

| Adoma Apartments | Toulouse, France | 2015 | 4 | 56 | Low | High | [7,41] |

| Frankfurt European School | Frankfurt Am Main, Germany | 2015 | 3 | 98 | High | Moderate | [7,41,43] |

| Puuokoka House 1 | Vainonkatu, Finland | 2015 | 8 | 116 | Low | Moderate | [7,44] |

| Puuokoka House 2 | Vainonkatu, Finland | 2015 | 7 | 91 | Low | Moderate | [7,44] |

| Puuokoka House 3 | Vainonkatu, Finland | 2015 | 6 | 71 | Low | Moderate | [7,44] |

| Steigart Strasse Refugee Settlement | Hannover, Germany | 2015 | 2 | 185 | Low | High | [7,41] |

| Treet | Bergen, Norway | 2015 | 14 | 62 | Moderate | High | [45,46,47] |

| Integrated Comprehensive School | Frankfurt am Main, Germany | 2016 | 3 | 90 | High | Moderate | [42,43] |

| Wohnen 500 | Mäder, Austria | 2016 | 3 | 60 | High | High | [41] |

| Hotel Katharinenhof | Dornbirn, Austria | 2017 | 4 (concrete ground floor) | 39 | High | High | [41] |

| Hotel Revier | Lenzerheide, Switzerland | 2017 | 4 (concrete ground floor) | 96 | High | High | [42] |

| Woodie Student Hostel | Hamburg, Germany | 2017 | 7 (concrete ground floor) | 371 | Low | High | [7,41,42] |

| Hotel Jakarta | Amsterdam, Netherlands | 2018 | 9 | 176 | Low | Moderate | [7] |

| DAS Kelo | Rovaniemi, Finland | 2019 | 8 | - | Low | Moderate | [48,49] |

| Daycare Center | Frankfurt am Main, Germany | 2019 | 2 | 50 | High | Moderate | [42,43] |

| Hotel Bergamo | Ludwigsburg, Germany | 2019 | 4 | 440 | Moderate | High | [42] |

| Josefhof Health Centre | Graz, Austria | 2019 | 2 | 120 | High | High | [42] |

| Toimela | Nurmijärvi, Finland | 2019 | 4 | - | Low | High | [48,49] |

| Kirkkonummen Konsulintorni | Kirkkonummi, Finland | 2020 | 4 | - | Low | High | [48,49] |

| Lutterterrasse Student Residence | Göttingen, Germany | 2020 | 5 (concrete ground floor) | 265 | Low | High | [42] |

| Mannisenrinteen Puumanni, Building A | Jyväskylä, Finland | 2020 | 4 | - | Low | Moderate | [48,49] |

| Mannisenrinteen Puumanni, Building B | Jyväskylä, Finland | 2020 | 4 | - | Low | Moderate | [48,49] |

| Office Kaufmann Building Systems | Reuthe, Austria | 2020 | 3 (concrete ground floor) | 32 | High | High | [42,43] |

| Watts Grove | Tower Hamlets, England | 2020 | 6 | - | Low | High | [50,51] |

| Kaarna | Kuopio, Finland | 2021 | 7 | - | Low | High | [49] |

| Luisenblock West | Berlin, Germany | 2021 | 7 | 460 | Low | High | [42] |

| Rautalepänkatu 2 Building A | Tampere, Finland | 2021 | 4 | - | Low | High | [49] |

| Rautalepänkatu 2 Building B | Tampere, Finland | 2021 | 4 | - | Low | High | [49] |

| Tampereen Härmälänsydän | Tampere, Finland | 2021 | 4 | - | Low | High | [48,49] |

| Tampereen Kaupin puukerrostalo | Tampere, Finland | 2021 | 8 | - | Low | High | [48,49] |

| Vaasan Viherlehto | Vaasa, Finland | 2021 | 6 | - | Low | High | [48,49] |

| Koelmalaan | Alkmaar, Netherlands | 2022 | 5 | 260 | Low | High | [52,53] |

| Lumipuu, Building A | Tampere, Finland | 2022 | 6 | - | Low | High | [48,49] |

| Lumipuu, Building B | Tampere, Finland | 2022 | 6 | - | Low | High | [48,49] |

| Nila | Kuopio, Finland | 2022 | 7 | - | Low | High | [49] |

| Pyssysepänkaari 3 | Kirkkonummi, Finland | 2022 | 5 | - | Low | High | [49] |

| Boarding School Wood Technology Centre | Kuchl, Austria | 2023 | 7 (concrete ground floor) | 82 | Moderate | High | [42] |

| Vogewosi, Flurgasse—Housing 500 | Feldkirch, Austria | 2023 | 3 | - | High | High | [42] |

| Campus Valkenvoortweg Waalwijk | Waalwijk, Netherlands | 2024 | 3 | - | High | High | [52,54] |

| Housing in Big Sky | Big Sky, United States | 2025 | 3 | 120 | High | Extreme | [43] |

| ID | Connection Description | Figure | Fasteners Detail | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

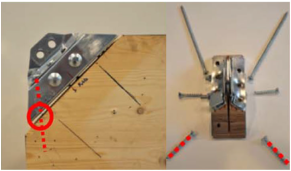

| IMC-1 | The connection system uses steel plates with screws to fasten adjacent modules. A soundproofing mechanism was proposed by installing elastic bearings between modular units that lack internal connectivity and have no soundproofing for modules within the same occupational unit. Steel plates were proposed for horizontal and vertical inter-modular connections to withstand shear forces, while steel rods were suggested to control uplift forces within the modules. |  | Fastener size between 6 and 12 mm screws | [55] |

| IMC-2 | An interlocking connection system was proposed for modular volumetric construction. It consists of steel 3D-printed tensile and shear connections, composed of male and female components that self-lock, restraining movement in their primary and secondary working directions. The construction process requires a specific order to slide and stack the modules. |   | Screws used for the connections HBSP12120 and LBS7100 | [56,57,58,59] |

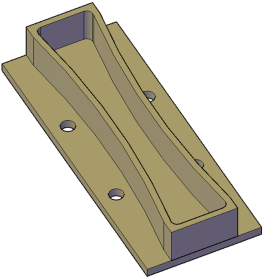

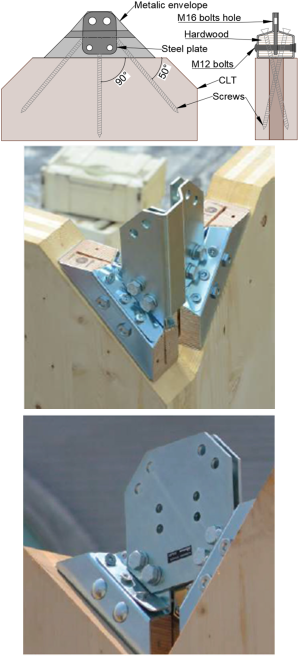

| IMC-3 | A connection system named X-RAD, designed for CLT structures that can be applied to both 2D and 3D modular construction. The X-RAD system was designed as a point-to-point mechanical connection located at the corners of the CLT panels. It is composed of an outer metallic envelope, an internal steel plate, an inner core made of hardwood, a pair of horizontal bolts, and a set of six self-tapping screws. |  | M12, M16 bolts, and VGS 11 × 350 screws | [60,61,62,63,64,65,66] |

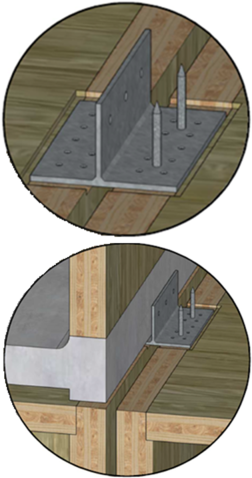

| IMC-4 | The inter-modular connection proposed consists of a steel T-shaped angle plate with pins. The steel pins were designed to fit into steel cones that should be cast into the prefabricated floor slab. For the assembly of the modular building, the steel plates are screwed on top of two adjacent side walls prior to stacking the modules of the next story. Once the first module of the next story is placed, the T-shape is secured on one side of the slab of that module. |  | Screws * | [67] |

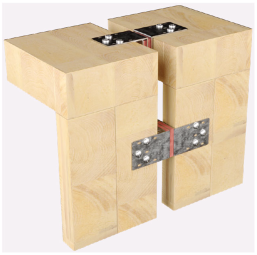

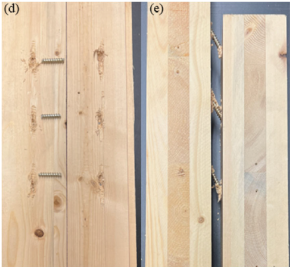

| IMC-5 | The proposed dowel-type connection is designed to join the floor panel of an upper CLT volumetric module to the ceiling panel of the module located directly beneath it, enabling effective shear transfer between vertically adjacent modules in a stacked modular building system. |  | 25.4 mm Read Oak and Yellow Birch dowels, and 8 mm fully threaded screws (SDCF22614 and SDCF22858) | [68] |

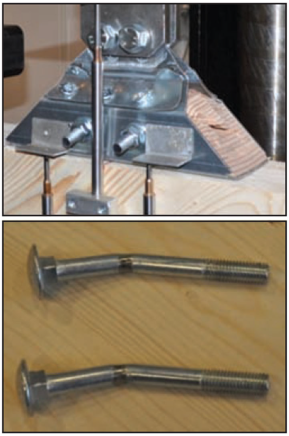

| IMC-6 | Two independent connections were developed as the inter-modular connection for volumetric stackable timber modules. The vertical connection was attached to the walls of the upper and lower modules to connect them through a bolt, preventing the uplift and horizontal sliding of the modules. The horizontal connection was designed as a damper device using low-yield steel to dissipate energy through shear deformation. |  | 8 × 160 mm screws | [69] |

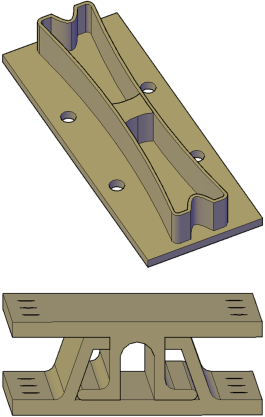

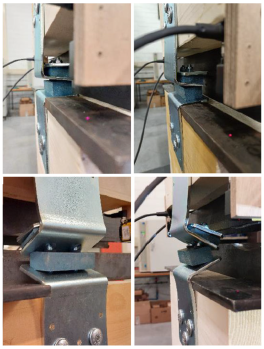

| IMC-7 | Straviwood ModuLink consists of two L-shaped steel brackets, one of which is shorter than the other. They are linked by two bolts M8 × 65 and contain two elastomeric bearing (foam) blocks to provide acoustic-isolation capacity. A locknut secures the plates in place and ensures adequate pre-compression of the foam block. It was developed as a horizontal connection for contiguous modular CLT constructions. Patent number BE 1030721. |  | 3 HECO-TOPIX-plus 10 × 100, flange head screws per side | [70,71,72,73] |

| Conn. ID | IMC-1 | IMC-2 | IMC-3 | IMC-4 | IMC-5 | IMC-6 | IMC-7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural metrics | VC | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| HC | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| CR | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| DF | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Total | 3 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Conn. ID | IMC-1 | IMC-2 | IMC-3 | IMC-4 | IMC-5 | IMC-6 | IMC-7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturing metrics | CC | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| CI | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| IP | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Total | 5 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 6 |

| Conn. ID | IMC-1 | IMC-2 | IMC-3 | IMC-4 | IMC-5 | IMC-6 | IMC-7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construction metrics | DfA | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| DfD | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| TC | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | |

| Total | 0 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 5 |

| Conn. ID | IMC-1 | IMC-2 | IMC-3 | IMC-4 | IMC-5 | IMC-6 | IMC-7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental and numerical metrics | CET | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| FSET | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| NME | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| AMD | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Total | 1 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| ID | Experimental Test | Loading Protocol | Damage | Failure Modes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMC-2 | Tensile connection: Three monotonic tests Two cyclic tests Shear connection: One monotonic test (two specimens) One cyclic test (two specimens) | Monotonic loading (0.05 mm/s) Cyclic loading (0.02 mm/s) EN 12512 [76] with estimated yield point of 4 mm in tension and 2 mm in shear |  Tension Tension  Shear | Plastic deformation within the male connection Tensile connection [58]: Bending of the L-shaped elements in the male connection Shear connection [58]: There was a sudden drop in the force after reaching 4 mm, followed by another after reaching 6.5 mm, indicating buckling in the shear connection |

| IMC-3 | Preliminary tests for screws withdrawal capacity The connection was tested in five different loading configurations as described in [60,61] | Monotonic loading (0.1 mm/s) EN 26891 [77] Cyclic loading EN 12512 [76] |  Tension Tension Shear Shear | Tension configuration [61]: Block-shear failure, local failure in the hardwood insert Shear, Tension-shear, and compression-shear [61]: Tensile failure of screws, cracks and splitting of wood insert |

| IMC-3 | Shear-tension and shear compression monotonic tests Wall systems assembled with X-RAD | Monotonic loading (0.1 mm/s) EN 26891 [77] Cyclic loading EN 12512 [76] |  Tension Tension Shear  Tension-shear Tension-shear Compression-shear Compression-shear | Tension [62]: Block tearing of the metal envelope Shear [62]: Tensile rupture of screws Tension-shear and Compression-shear [62]: Tensile rupture of screws |

| IMC-3 | Tests using Ponderosa Pine CLT Monotonic test specimens: Two specimens in tension One in compression One in tension-shear One in compression-shear Cyclic test specimens: Three in cyclic tension-compression Four in cyclic shear-tension and shear-compression | Monotonic loading EN 26891 [77] Cyclic loading EN 12512 [76] |  Tension/Compression-shear Tension/Compression-shear Tension | Tension-shear [66]: Tensile fracture of the screws Compression-shear [66]: Shear fracture of the screws at the connection-CLT interface Tension-shear and compression-shear [66]: Yielding of the screws in tension loading followed by shear fracture of the screws in compression loading Vertical cracks in the hardwood insert |

| IMC-5 | Monotonic and cyclic single-shear plane CLT-to-CLT joint tests using two species of hardwood dowel (RO, B) [68] and large-diameter screws installed at 90- (S90) and 45-degree angles (S45) (tension and compression for 45°) | Monotonic loading ASTM D5764 [78] Cyclic loading ASTM E2126 [79] CUREE basic protocol |  Hardwood dowels Hardwood dowels Screws | RO and B [68]: Longitudinal shear crack in the hardwood dowels S90 [68]: Two hinges in the screw corresponding to Mode IV, according to NDS [80] S45 [68]: Withdrawal and buckling when loaded in positive and negative phases, respectively |

| IMC-6 | Five cyclic tests for the vertical connection Three cyclic tests for the horizontal connection | Modified CUREE basic loading protocol (0.5 mm/min) |  Horizontal connection Horizontal connection | Vertical connection [69]: Permanent deformation of top plate Horizontal connection [69]: Stress concentration occurred at the corners of the low-yield steel dampers |

| IMC-7 | Each test was executed five times: The first test to determine Fmax (Fmax deformation = 15 mm), then four monotonic tests. Shear tests with four connections each, compression tests with four connections each, and tensile tests with two connections each. [73] | Monotonic loading EN 26891 [77] (3 mm/min) |  Shear Shear Compression  Tension | Shear [73]: Pronounced shearing of the spacing elastomer, rotation of L-plates and slip of the screws. Compression [73]: Complete compression of the elastomeric bearing. Yielding of L-plates. Contact between bolts and timber, indentation in the timber. Tension [73]: Compression of the elastomeric bearing, yielding of the L-plates, and pronounced bending of the bolts. |

| Conn. ID | IMC-1 | IMC-2 | IMC-3 | IMC-4 | IMC-5 | IMC-6 | IMC-7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural | 3 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Manufacturing | 5 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 6 |

| Construction | 0 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 5 |

| Exper. & Num. | 1 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 9 | 20 | 20 | 8 | 11 | 12 | 16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zambrano-Jaramillo, J.S.; Fischer, E.C. A Review of Inter-Modular Connections for Volumetric Cross-Laminated Timber Modular Buildings. Buildings 2026, 16, 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010078

Zambrano-Jaramillo JS, Fischer EC. A Review of Inter-Modular Connections for Volumetric Cross-Laminated Timber Modular Buildings. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):78. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010078

Chicago/Turabian StyleZambrano-Jaramillo, Juan S., and Erica C. Fischer. 2026. "A Review of Inter-Modular Connections for Volumetric Cross-Laminated Timber Modular Buildings" Buildings 16, no. 1: 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010078

APA StyleZambrano-Jaramillo, J. S., & Fischer, E. C. (2026). A Review of Inter-Modular Connections for Volumetric Cross-Laminated Timber Modular Buildings. Buildings, 16(1), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010078