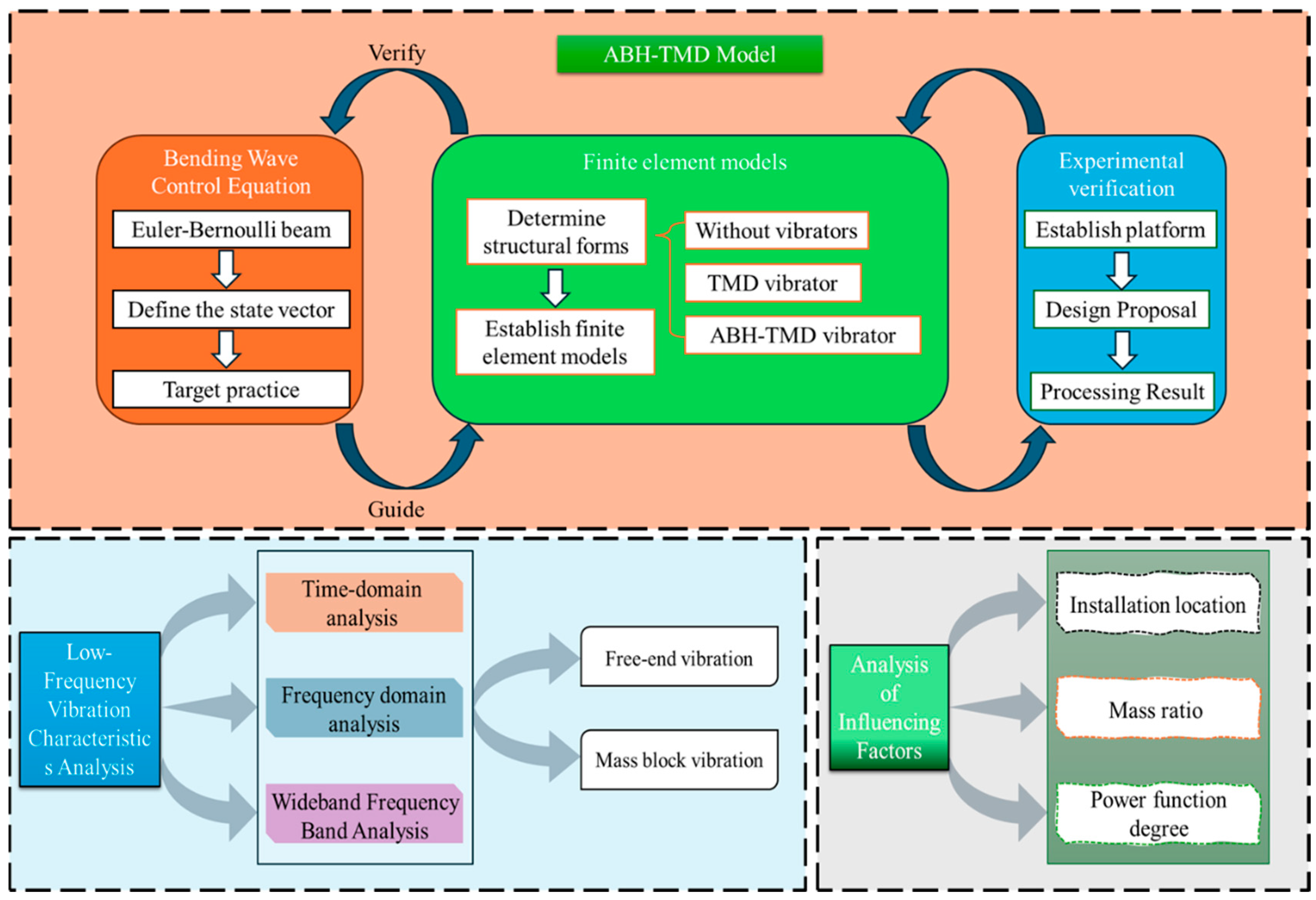

This chapter establishes a theoretical model of the ABH-TMD and derives its control equations to evaluate its feasibility for vibration suppression. Furthermore, based on these equations, a corresponding finite element model is constructed for subsequent dynamic analysis, followed by experimental validation of its accuracy.

2.1. One-Dimensional ABH Structure Bending-Wave Control Equation

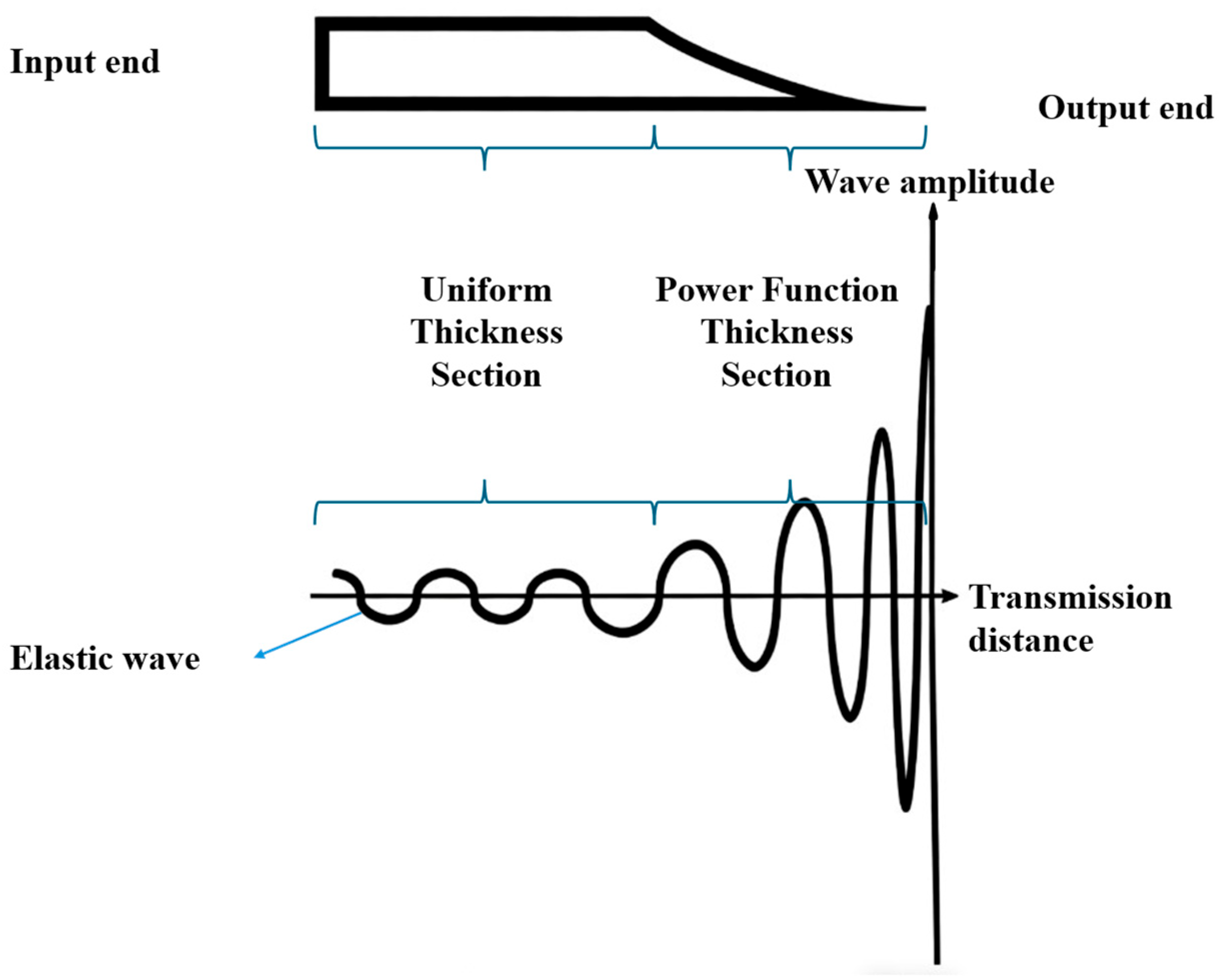

Acoustic black holes resemble the concept of black holes in astrophysics. Elastic plates of varying thickness gradually decreasing to zero (elastic wedges) can support a variety of unusual effects for flexural waves as they propagate towards the sharp edges of such structures and are reflected back [

23]. By specifically designing the thickness profile of a structure or altering its material properties, the wave propagation speed gradually decreases as thickness diminishes, while the regional wave number progressively increases with thickness. Under ideal conditions—where the structure exhibits total internal reflection at its boundaries and the plate thickness gradually diminishes to zero—elastic waves will concentrate along the thickness direction at the zero-thickness point, achieving zero reflection along the length. This principle is illustrated in

Figure 2.

According to Euler–Bernoulli beam theory, for a one-dimensional beam, the dispersion relationship between the circular frequency (

) and the wave number (

) of bending waves is

where

is the bending-wave velocity constant, which depends solely on the beam’s material and geometric properties.

Therein, represents Young’s modulus, is the material density, signifies Poisson’s ratio, and indicates the local thickness of the beam.

For a one-dimensional thin plate, under the assumption of small deformation and plane stress, the displacement equation of vibration,

, is an equality concerning

(the coordinate in the propagation direction),

(the coordinate in the perpendicular direction), and

(time). Herein, the governing equation for bending waves is

Here,

represents the bending stiffness, and

denotes the Laplace operator. Separating the spatial and temporal variables yields

The above equation, when substituted back into the wave-number equation, yields where

represents the spatial distribution of the vibration, and

denotes the temporal distribution.

Separating the temporal distribution from the spatial distribution yields

The time component is decomposed into the harmonic oscillation equation,

. The spatial component equation is

Considering that the lower-order terms are sufficient to describe the motion state at any point in the structure, the errors in vibration amplitude caused by higher-order terms are small enough to be negligible. The ABH-TMD structure designed in this paper must be used within a material’s elastic phase. We thus disregard its plastic deformation phase, and it is assumed that all materials comply with Hooke’s law. In neglecting higher-order derivative terms in the equation and assuming that the material is homogeneous, it can be derived that

Phase definition is the cumulative phase shift as a wave propagates through the plate material.

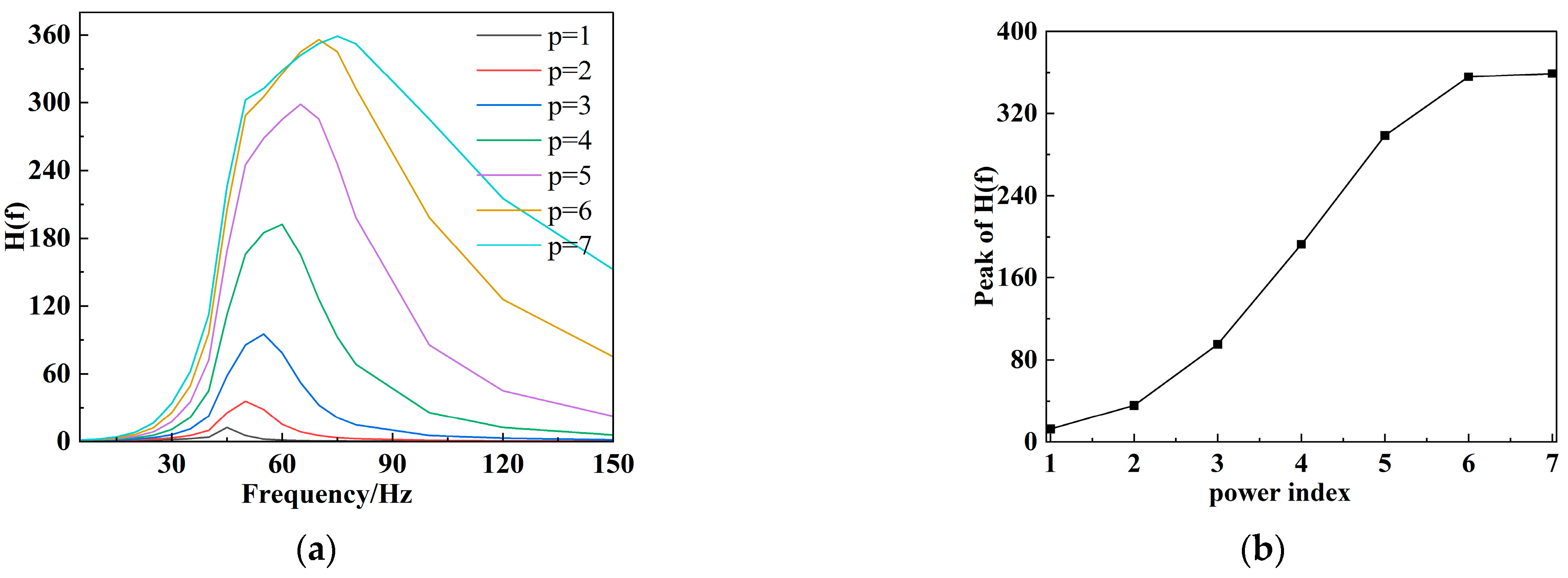

When , the cumulative phase approaches infinity, preventing the wave from escaping the thinnest part of the structure and eliminating reflection. When sound propagates through a wedge-shaped structure whose thickness varies according to a power function with an exponent greater than two, when the thickness approaches zero, the local acoustic number becomes infinitely large. Macroscopically, the sound waves can be thought to be concentrated and focused on the tip of the wedge plate, unable to escape. The vibration amplitude approaches infinity, and in the direction of energy propagation, the elastic wave energy becomes concentrated in the zero-thickness segment of the power-function-defined wedge plate.

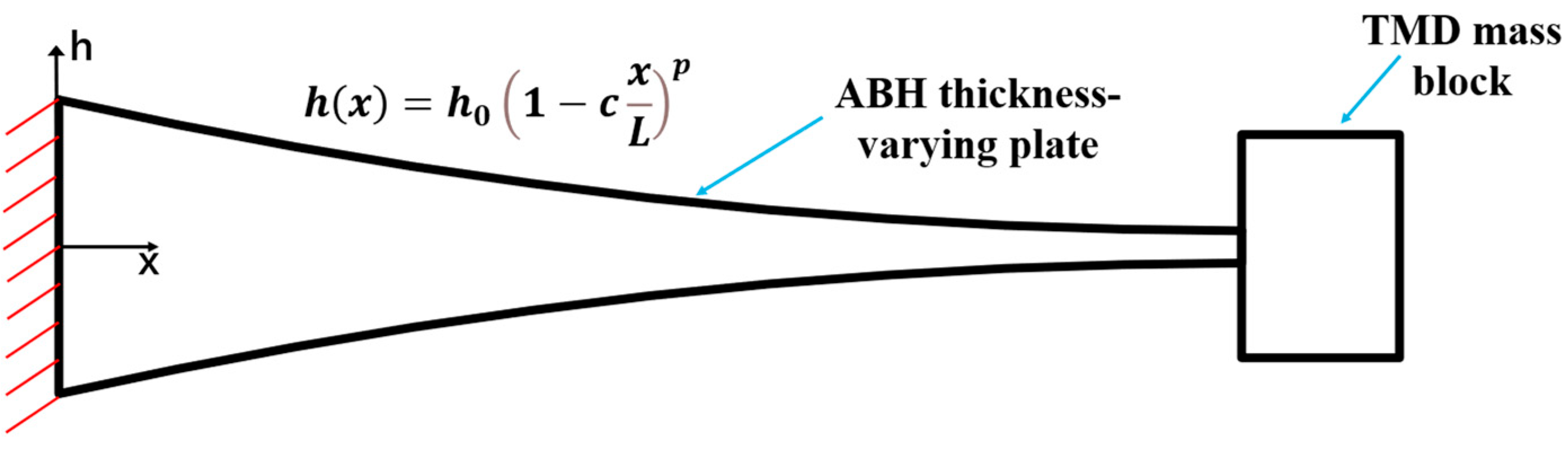

2.2. One-Dimensional ABH-TMD Structure Bending-Wave Control Equation

For the proposed ABH-TMD structure in this paper, the configuration involves placing an additional TMD mass block at the tip of the ABH varying-thickness plate. Let the extension direction of ABH thickness variation be

, where

represents the fixed end (maximum thickness). The fixed-end thickness is

. The free end at

has a thickness of

and connects to the TMD mass block on its right side. The thickness variation equation is

In this formula,

(

) denotes the order of the power function, which, in practice, corresponds to the steepness of the trend in cross-sectional thickness variation. A higher value indicates a more pronounced change in thickness. Here,

, such that

. The one-dimensional ABH-TMD structure is illustrated in

Figure 3.

The cross-sectional area and moment of inertia of the fixed end of the beam are

For the ABH varying-thickness plate with a rectangular cross-section and constant width, the cross-sectional area and moment of inertia at any point (

) along the model are

Here, . Assuming that excitation is applied from the fixed end of the structure, it exists in the form of a harmonic vibration, where the displacement equation is .

According to the Euler–Bernoulli beam bending vibration equation,

We substitute the section’s moment of inertia and cross-sectional area into the equation

Dividing both sides of the equation by

yields

We set

such that

; then, the controlling equation is

The equation is a fourth-order ordinary differential equation (ODE) with variable coefficients. In most cases, ODEs do not possess analytical solutions and require numerical methods for computation, including the Runge–Kutta method, the shooting method, and the finite difference method. The Runge–Kutta method uses known initial conditions and integrates from the starting point. In the context of ODEs, it is primarily used for solving initial value problems and cannot directly handle boundary value problems, making it unsuitable for this model’s requirements. The finite difference method approximates the differential equation as a system of algebraic equations on a discrete grid, making it suitable for solving complex boundary conditions. However, it requires large systems of equations, complex programming, and high computational power. Therefore, this paper employs the shooting method to solve the ODE, transforming the boundary value problem into an initial value problem. By adjusting the initial estimation to satisfy the terminal boundary conditions, it requires minimal computational resources and features an intuitive programming process. However, it is highly sensitive to the initial value estimation.

We set boundary conditions and solve the fourth-order ODE using the target method, followed by the application of harmonic excitation at the fixed end, with the remaining boundary conditions as follows:

At the fixed end (

),

where

is the amplitude of the input excitation. At the point of connection with the mass block (

), disregarding the gravitational effect on the entire structure, it can be derived that

Moreover, the shear forces at the connection surface are in equilibrium, meaning that the shear force

in the beam section equals the inertia force of the mass block:

In the equation,

represents the mass of the block, considering only translational coupling while neglecting rotational inertia.

We define the displacement transfer function as

, expressing the relationship between the input and output displacement in the frequency domain:

is a Fourier transform of the output signal; is a Fourier transform of the input signal. Here, represents the ratio of the output and input amplitudes, while denotes the phase delay of the output relative to the input.

The velocity transfer function

is identical to the displacement transfer function because the excitation load is harmonic, and the velocity

.

We define the form of a first-order system in preparation for the target practice method. The state vector is defined:

The bending moment and shear force at any point in the structure are

Through derivation from the definition, the following is obtained:

From the governing equations, it can be derived that

From the boundary conditions, it can be observed that

From

, we can obtain

The unknown boundary conditions are

and

, which are treated as target parameters

and

.

The initial conditions are .

Numerical integration of the state equation for from to results in .

We set boundary conditions at the end of the structure:

Newton’s method is used to adjust

and

until

. Once converged,

becomes

, and it can be calculated as follows:

The formula proposed above is validated by comparing the calculated and simulated results. We assume a beam length of

, rectangular cross-section width of

, and thickness variation of

. The chosen material is steel with

. The mass of the end mass block is

. The base excitation

;

. With

p = 3 selected, modeling was performed using the COMSOL (6.2) finite element simulation software. A point mass was applied at the free end of the ABH beam. The longitudinal displacement component at

was chosen as the output.

was calculated and compared with the simulation results. The results are shown in

Table 1 below.

Close agreement between the displacement transfer results obtained using finite element simulation software and those of the method described in this paper is observable in

Table 1 at different frequencies; errors are less than 2% in each case—within a reasonable range. Possible causes of such error include the limited minimum precision achievable in numerical calculations and the influence of mesh size and mesh quality on the results of finite element simulations.

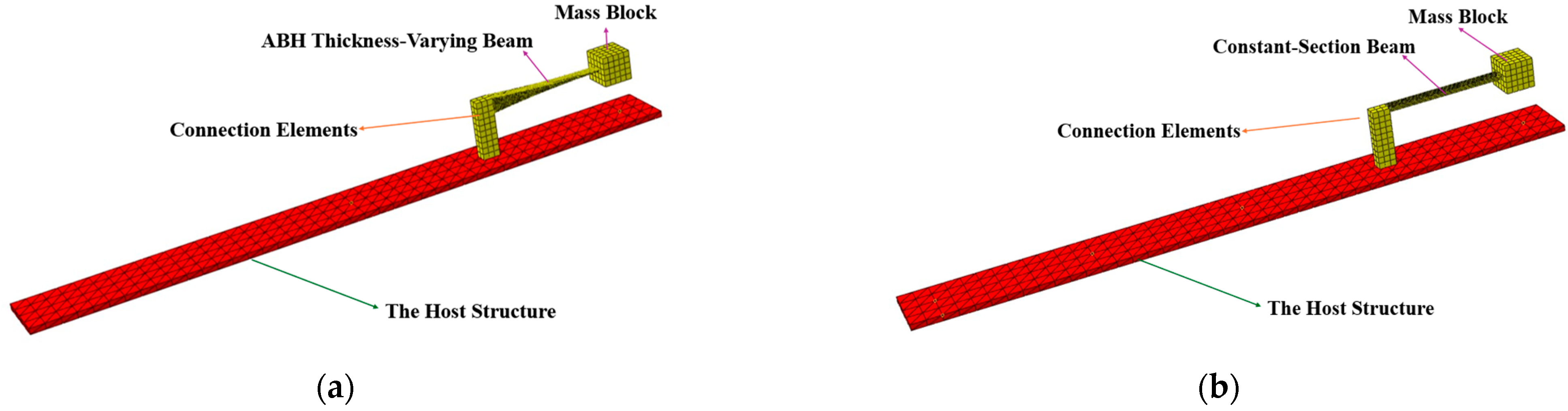

2.3. Finite Element Model Simulation and Validation

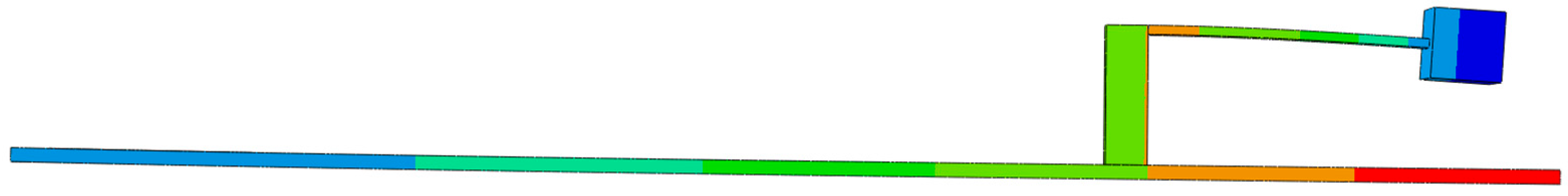

Based on the proposed vibration control scheme, in this section, we establish a finite element model to analyze its vibration suppression capability. The model is divided into three components: the host structure, connecting elements, and the vibrator. The host structure’s model adopts a cantilever beam structure, with the coordinate axes defined as follows: the x-axis is the beam length, the y-axis is the height, and the z-axis is the width. To evaluate the effectiveness of the vibration control scheme for the ABH-TMD, this section details two distinct vibrator models—an ABH varying-thickness beam composite model and a constant-section beam composite model—as shown in

Figure 4.

The finite element method was applied to validate the computational modeling of the ABH-TMD vibrator model. A three-dimensional vibration model was established in Abaqus/CAE(2023) software, comprising three components: the vibrating host structure, connecting elements, and the vibrator model. The vibrator model consists of a beam and a TMD mass block.

For the concrete model setup, the host structure was modeled using 7075 aluminums with dimensions of 1.1 m × 0.1 m × 0.01 m. Considering the material’s width-to-thickness ratio of 10:1 and length-to-thickness ratio of 110:1, the influence of thin-shell theory on results cannot be ignored. Beam elements in Abaqus neglect the effect of width on calculations, leading to significant discrepancies between the simulation results and the actual values. Therefore, a solid element with dimensions of 1.1 m × 0.1 m × 0.01 m is used for simulation in the finite element model. Material properties conform to 7075Al’s national standard density (2820 ), Young’s modulus (71 ), and Poisson’s ratio (0.33). The model was meshed using second-order tetrahedral elements. Boundary conditions specified a fixed constraint on the left end surface of the host structure.

The natural frequency of the secondary vibration system must be tuned to match the vibrations being suppressed. The inhibition range considered in this paper is close to the natural frequency of the host structure. When the external excitation frequency approaches the natural frequency of the host structure, resonance occurs, causing the vibration amplitude of the host structure to peak. This frequency is the primary control target. Furthermore, tuning the secondary system’s natural frequency close to the host structure’s natural frequency induces a dynamic damping effect. The original single resonance peak of the host structure splits into two new resonance peaks with slightly different frequencies. Between these two new peaks, the amplitude corresponding to the original resonance frequency approaches zero. To more effectively judge the effectiveness of the vibration control scheme for the ABH-TMD, the natural frequencies of the vibrator and the host structure must be analogous. Therefore, the first three natural frequencies of the host structure are solved.

The calculation formula is given in Equation (41), where

denotes the nth natural frequency of the host structure,

represents the nth modal characteristic value of the host structure (cantilever beam),

is the sectional moment of inertia,

is the length of the host structure, and

is the surface mass of the host structure, defined as

(where ρ is the density).

Finite element analysis was employed to calculate the modal forms and frequency magnitudes; the results are presented in

Table 2.

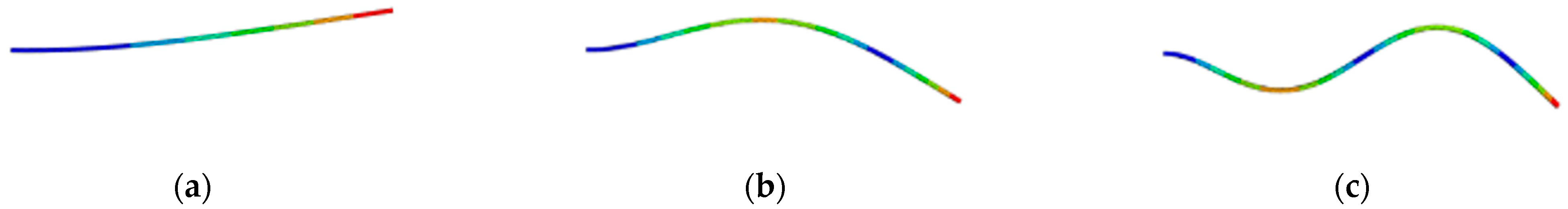

The mode shapes are illustrated in

Figure 5a–c.

The first-order frequency error (calculated using the frequency difference ratio formula) is 0.89%, the second-order error is 0.98%, and the third-order error is 1.13%—all within the permissible error range.

In TMD measures, the natural frequency of the secondary vibrating structure (vibrator) must be close to that of the host structure to achieve dynamic damping effects and reduce the vibration amplitude in the target frequency band. Therefore, when configuring the vibrators, the first-order natural frequencies of both the ABH-TMD and TMD were established akin to that of the host structure.

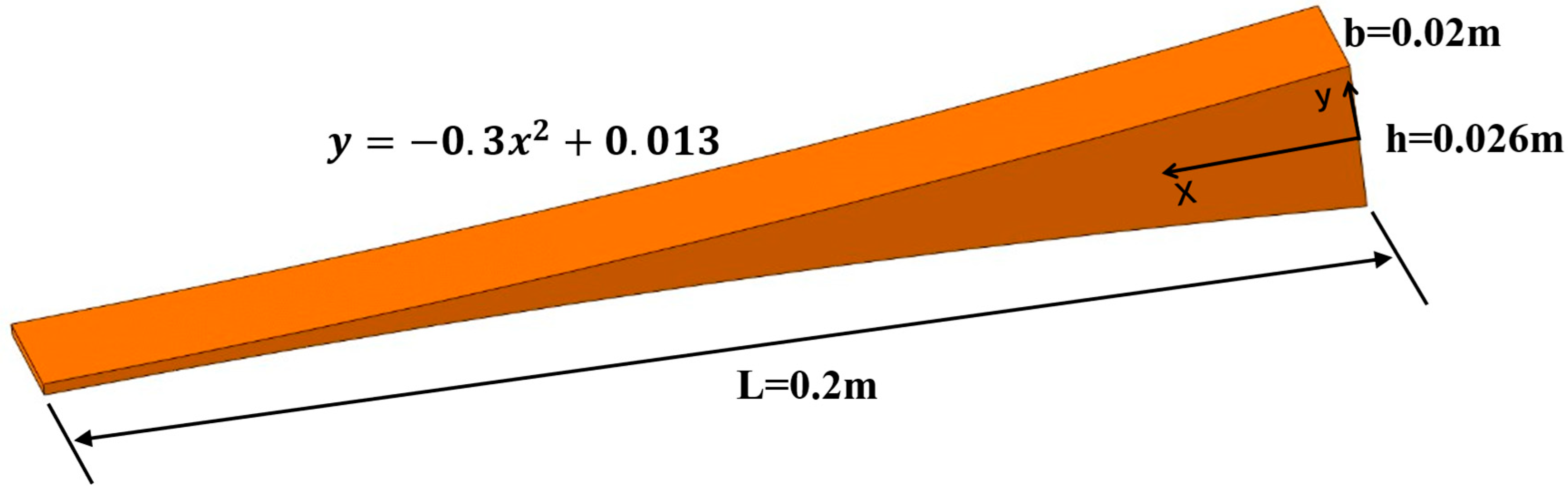

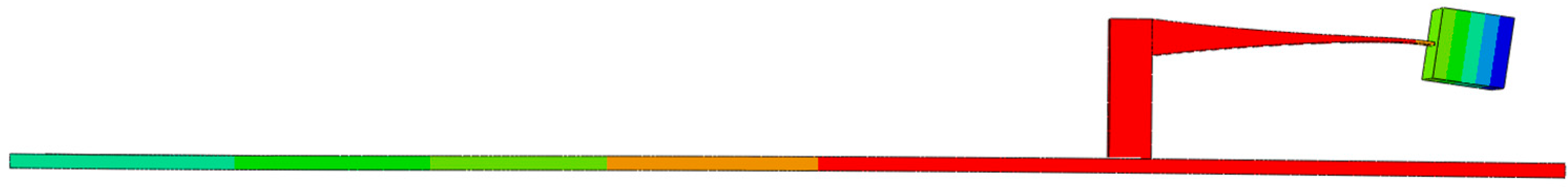

The geometric shape of the connector is a rectangular prism with dimensions of 0.03 m × 0.02 m × 0.1 m. The first natural frequency of the host structure is known to be 6.76 Hz. The ABH varying-thickness-beam composite-model vibrator is divided into two portions: the ABH varying-thickness beam and the mass block. The cross-section of the former is a quadrilateral with two curved edges, which are symmetrical about the central axis, and their functional expressions are given in Equation (43) as a variation of Formula 10. After determining the order (p) of the varying-thickness beam, the primary consideration is the magnitude of its first natural frequency, which must be similar to that of the host structure. The length of the varying-thickness beam is designed to be consistent with that of a beam with a uniform cross-section. The ideal ABH structure requires a thickness approaching zero, but the actual cutoff thickness cannot be zero. When this value is too large, reflections occur at the cutoff plane, leading to a decrease in the ABH’s wave-gathering capability and a reduction in the energy density introduced into the tip mass. However, excessively thin cutoff thicknesses may cause shear failure at the tip, and practical manufacturing precision is inherently limited. In order to meet material strength requirements, we select the minimum precision cutoff thickness feasible for actual fabrication. The varying-thickness beam’s width is 0.02 m, with a beam length of 0.2 m. The mass block dimensions are 0.05 m × 0.05 m × 0.05 m. The first-order natural frequency of the resulting ABH-TMD vibrator is 6.74 Hz. Due to the absence of functional curve expression in ABAQUS (Abaqus/CAE 2023) finite element software, the curve was approximated using twenty equal-distance linear segments. Simulating curves with continuous line segments can cause distortion in finite element models. In this paper, we employ linear interpolation, where a curve is approximated by twenty-line segments. An average length change of 1 cm corresponds to a thickness change of 0.17 cm. Within the reasonable range of linear interpolation, the structural thickness changes uniformly without abrupt variations, eliminating the risk of stress concentration caused by interpolation. A three-dimensional diagram of the ABH varying-thickness beam is shown in

Figure 6.

The composite model of the constant-section-beam vibrator consists of a constant-section beam and a mass block. It has a rectangular cross-section of 0.2 m × 0.0065 m, with a width of 0.02 m. The mass block has dimensions of 0.05 m × 0.05 m × 0.05 m. The first natural frequency is 6.75 Hz.

The host structure is formed from 7075AL. Both vibrator models and the connecting components are simulated using epoxy resin. The material properties are listed in

Table 3. The Young modulus of the resin material determines the stiffness of the variable-section beam, while its density determines the mass ratio of the ABH-TMD. Poisson’s ratio must be set such that the shear forces at the tip remain within the material’s tolerance range. The precision of grid partitioning primarily considers simulation fidelity, ensuring at least three grid cells within a single wavelength for simulation while simultaneously satisfying a minimum edge length of at least two grid cells. To ensure solution accuracy and reduce computation time, different meshing approaches are applied to various model components. The controlled body primarily undergoes bending deformation. Considering its thinness, first-order linear elements may exhibit shear locking under bending loads. Second-order tetrahedral elements are therefore employed, with a size of 0.1 times the minimum dimension. To minimize computational effort, linear hexahedral elements are used for connecting members and mass blocks. The varying-thickness and constant-section beams serve as primary comparison components, primarily experiencing minor bending deformation. Linear non-conforming hexahedral elements are employed, with element size referenced to the beam’s minimum cross-sectional dimension. The size is set to 0.02 times the minimum cross-sectional dimension to ensure accurate calculation of bending-wave energy. The frequency range considered in this paper centers around the first natural frequency of the structure. Both the main body and ABH-TMD exhibit minor bending deformation with sinusoidal excitation as the input load. Thus, structural damping is employed. For aluminum, this is set to 0.001, while that for resin is set to 0.005. The model is fixed at the left end of the main body. Gravitational acceleration of 9.8

is applied. A harmonic surface force with an amplitude of 10,000

is applied to the free-end surface, directed along the y-axis.

2.4. Experimental Verification

To validate the feasibility and accuracy of the aforementioned model, experimental verification was conducted. For the main experimental section, three distinct model configurations were established: a cantilever beam without control measures, a cantilever beam incorporating a TMD vibrator, and a cantilever beam incorporating an ABH-TMD vibrator. The cantilever beams and all components were configured according to

Section 2.3. The cantilever beams were secured using vise clamps, and the TMD and ABH-TMD vibrators were bonded to the main structure using AB adhesive. For the experimental excitation load, a YE1311 signal generator (Sinocera Piezotronics INC., Beijing, China) was used to establish the excitation form and frequency, transmitting electrical signals to the YE5872A power amplifier (Sinocera Piezotronics INC.), which adjusted the amplitude of the input vibration excitation. The YE5872A was connected to a JZK electric vibrator (Sinocera Piezotronics INC.), whose piston rod was fixed to the bottom of the cantilever beam’s free end. The input1 excitation was a sinusoidal function with an amplitude of 1 mm and a frequency range of 2 Hz to 14 Hz. The signal acquisition system employed a Picoscope 2124 eight-channel PC-based digital oscilloscope (Pico Technology Ltd., St. Neots, UK) to transmit collected data to a PC. An accelerometer probe with a sensitivity of 10 mV/g was positioned at the top surface of the cantilever beam’s free end to capture voltage signals. The experimental setup is illustrated in

Figure 7.

The acceleration amplitude at the free end of the cantilever beam was measured using the Picoscope (7.2.10). The amplitude data is in the form of a voltage signal, which must be converted into acceleration values. The conversion formula is as follows:

To avoid measurement errors caused by acceleration accuracy, sensor sensitivity was determined by averaging the five sets of experimental results. Simultaneously, to prevent clamping conditions from influencing results, the vise was adjusted to its tightest setting before each experiment.

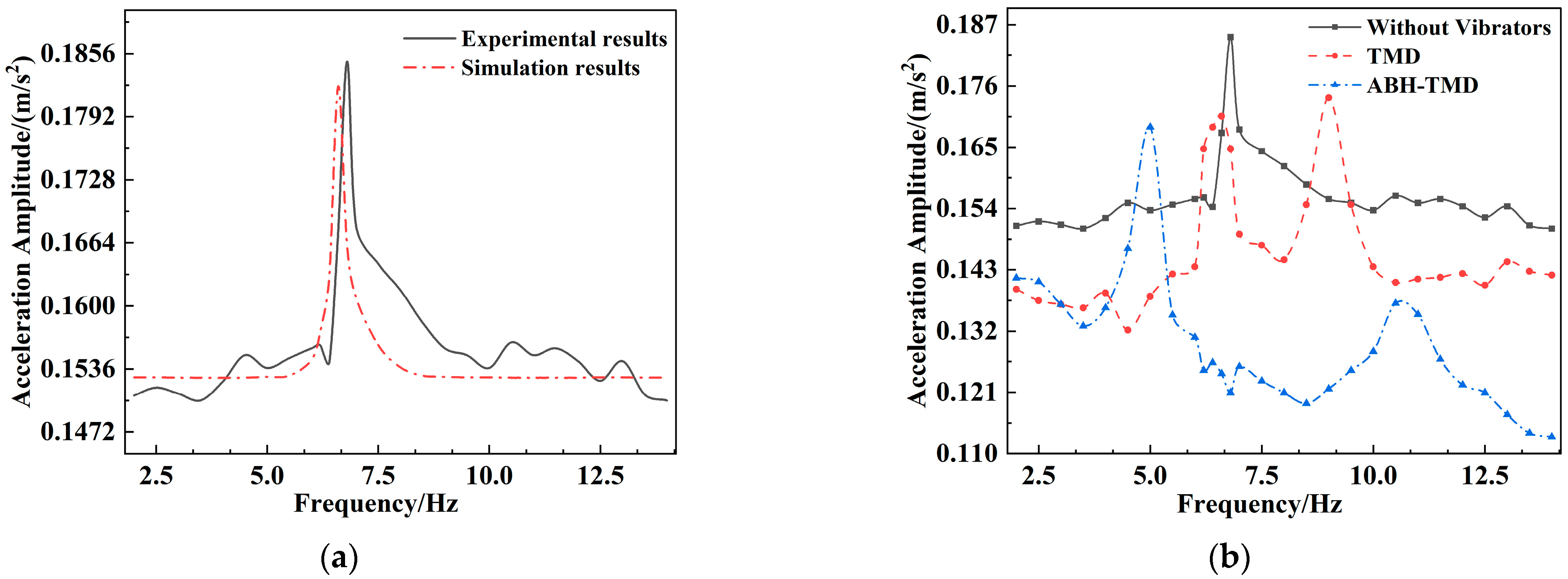

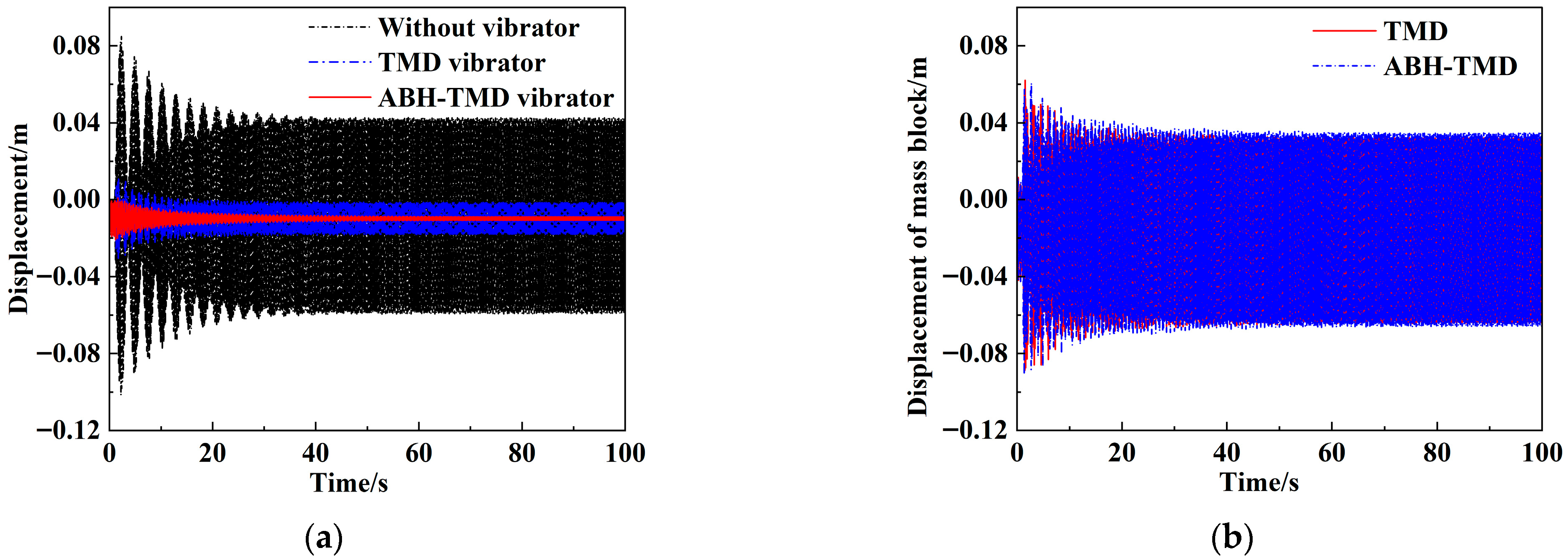

The measured voltage signal is converted into acceleration at the free end of the cantilever beam, with the acceleration amplitude shown in

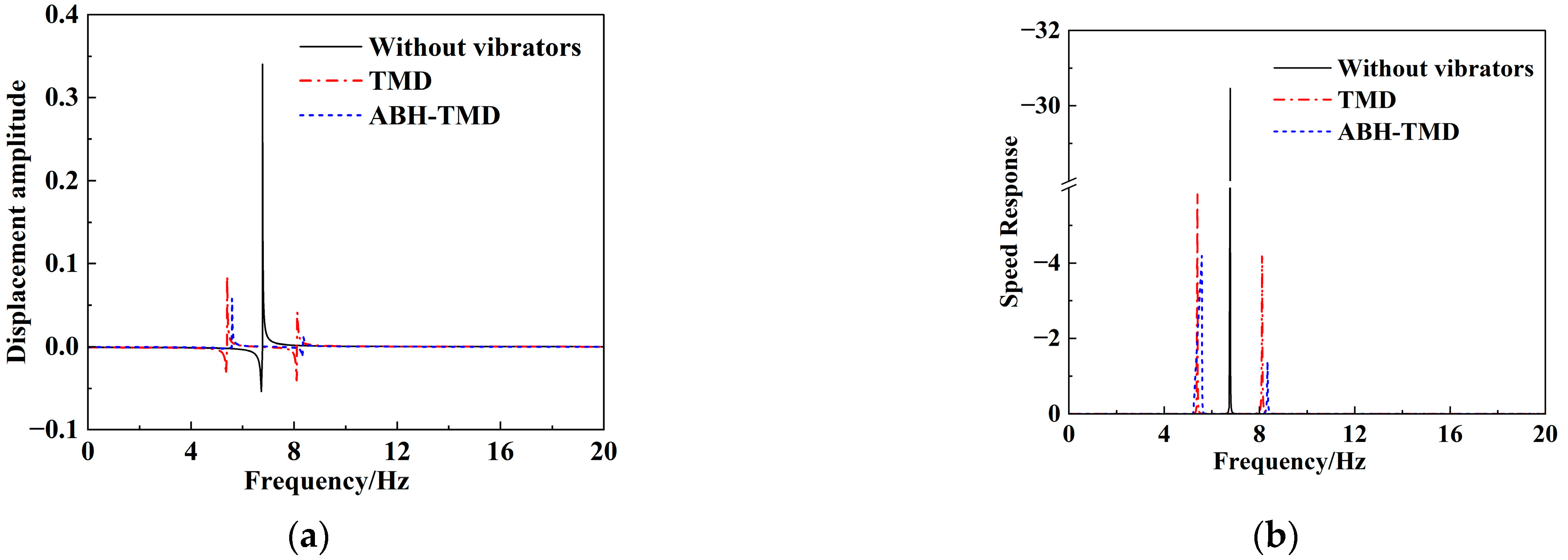

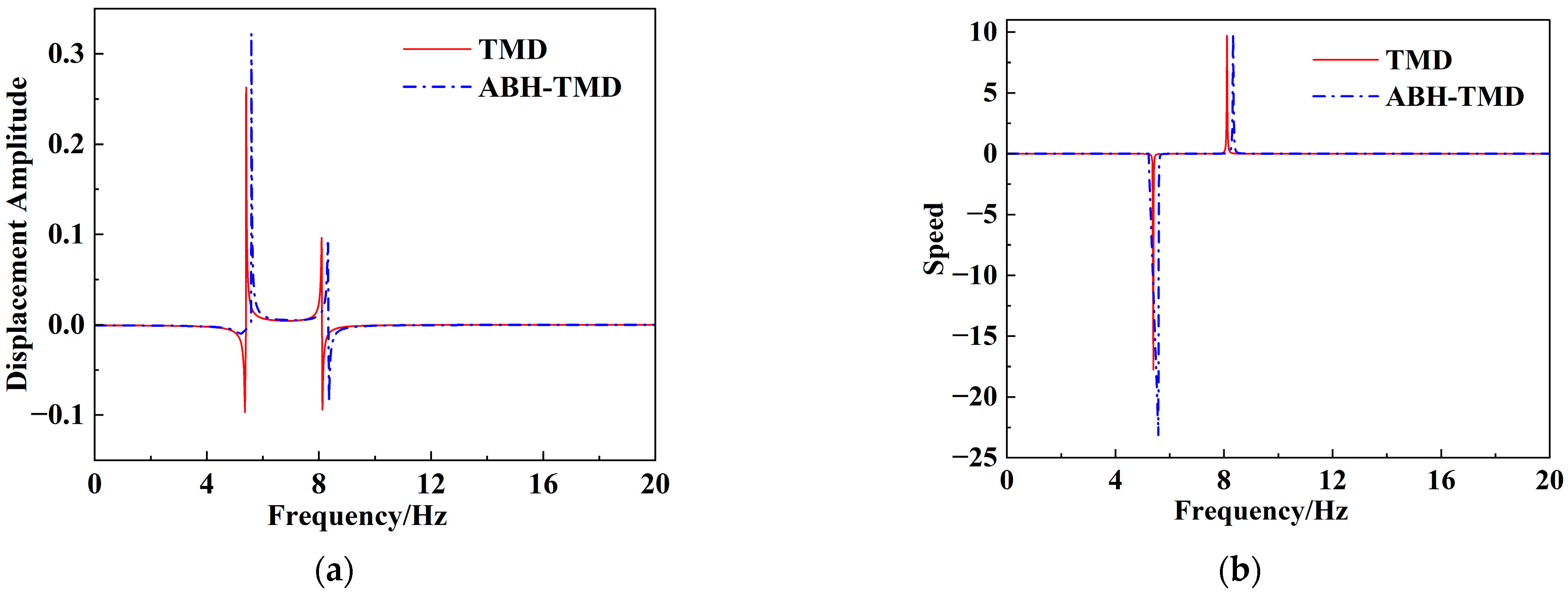

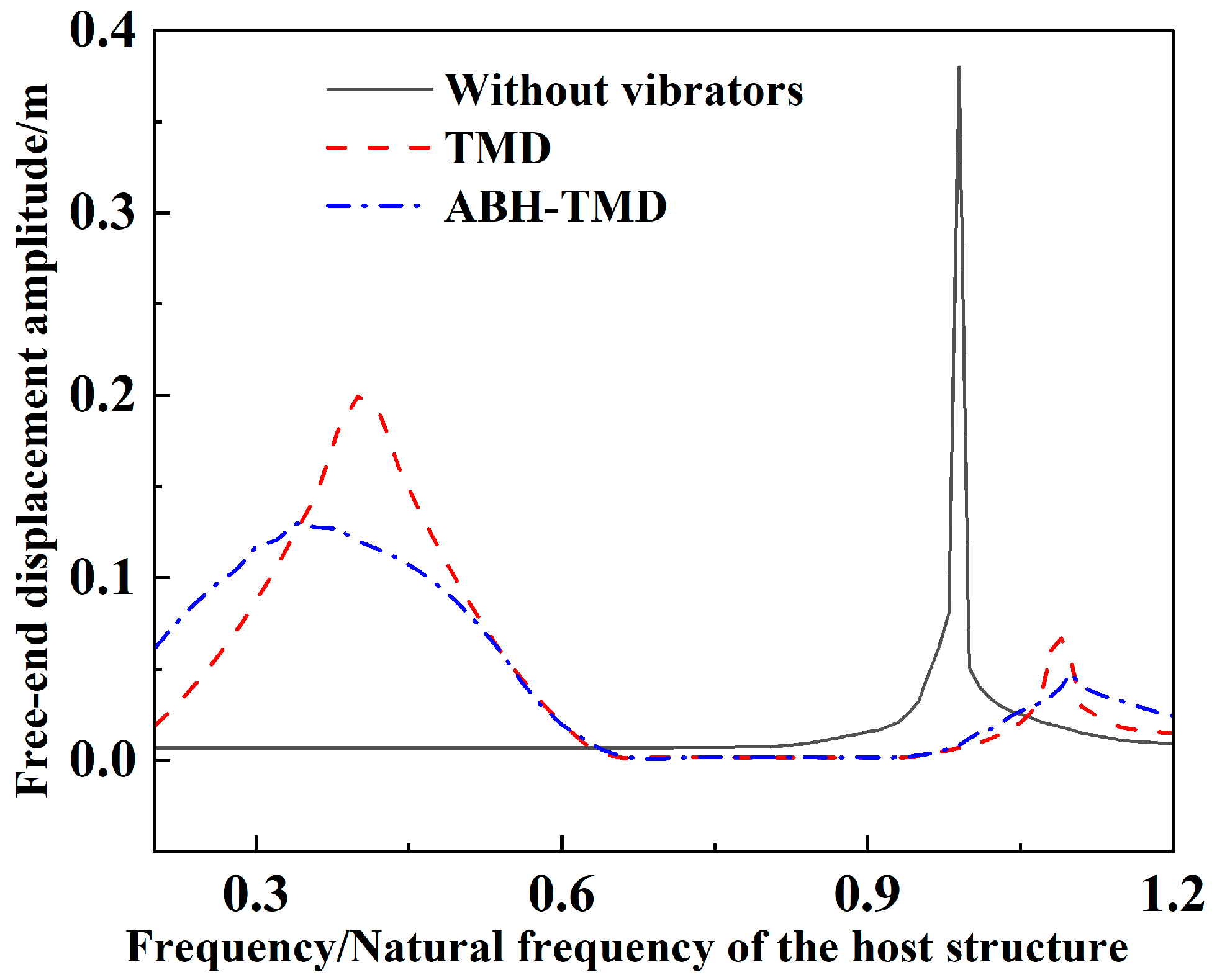

Figure 8.

The y-axis in

Figure 8 represents the amplitude of acceleration displacement after the cantilever beam stabilizes, while the x-axis denotes the magnitude of the input excitation frequency. As shown in

Figure 8a, the software simulation results are generally consistent with the experimental results, indicating that the finite element simulation is essentially accurate. Without any control measures, the free-end acceleration of the cantilever beam reaches a peak of 0.1848 m/s

2 at a frequency of 6.8 Hz. After installing the TMD and ABH-TMD vibrators, the resonance peak of the cantilever beam clearly splits into two distinct peaks. Under TMD control, these appeared at 0.1706 m/s

2 and 0.1739 m/s

2, while under ABH-TMD control, they occurred at 0.1686 m/s

2 and 0.1370 m/s

2, representing a 48.6% improvement in vibration suppression compared to TMD alone. Under TMD control, the two split peaks of the cantilever beam appeared at 6.6 Hz and 9.0 Hz. Under ABH-TMD control, they appeared at 5.0 Hz and 10.5 Hz, widening the vibration suppression bandwidth by 129.2%.

In the formula, denotes the structural vibration reduction rate, denotes the vibration reduction enhancement rate, denotes the maximum displacement amplitude, denotes the frequency band widening rate, and denotes the frequency bandwidth.

The experimental results show that the ABH variable-section rod can concentrate and absorb elastic waves input into the main body, focusing them onto the TMD mass block. This transfers and concentrates the vibration energy of the main body into the TMD mass block, broadening the TMD’s effective frequency band while significantly enhancing its vibration suppression performance in the low-frequency range.