A Review of the Soil–Geosynthetic Interface Direct Shear Test and Numerical Modelling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Soil–Geosynthetic Direct Shear Test Overview

2.1. Soil and Geosynthetic Features

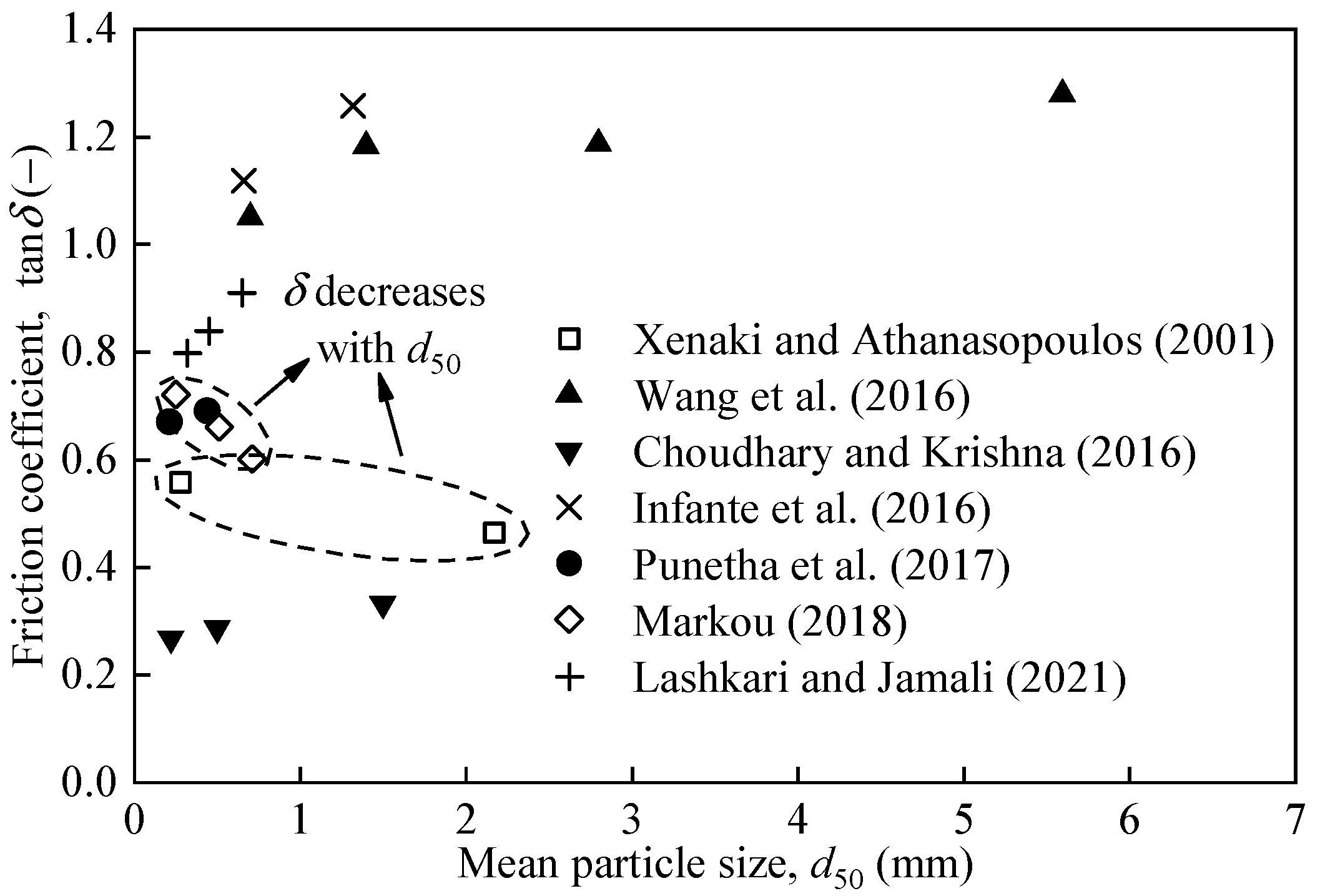

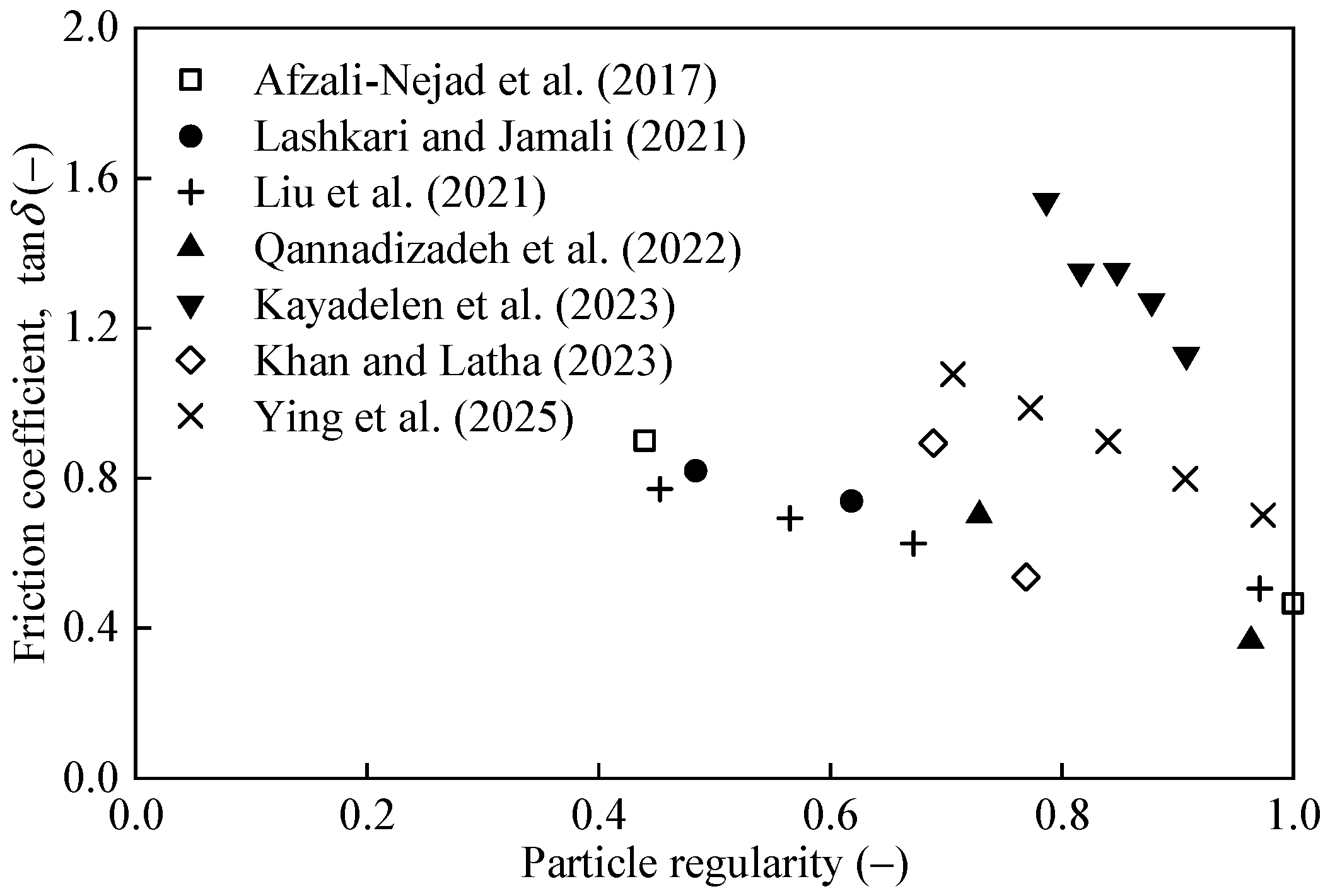

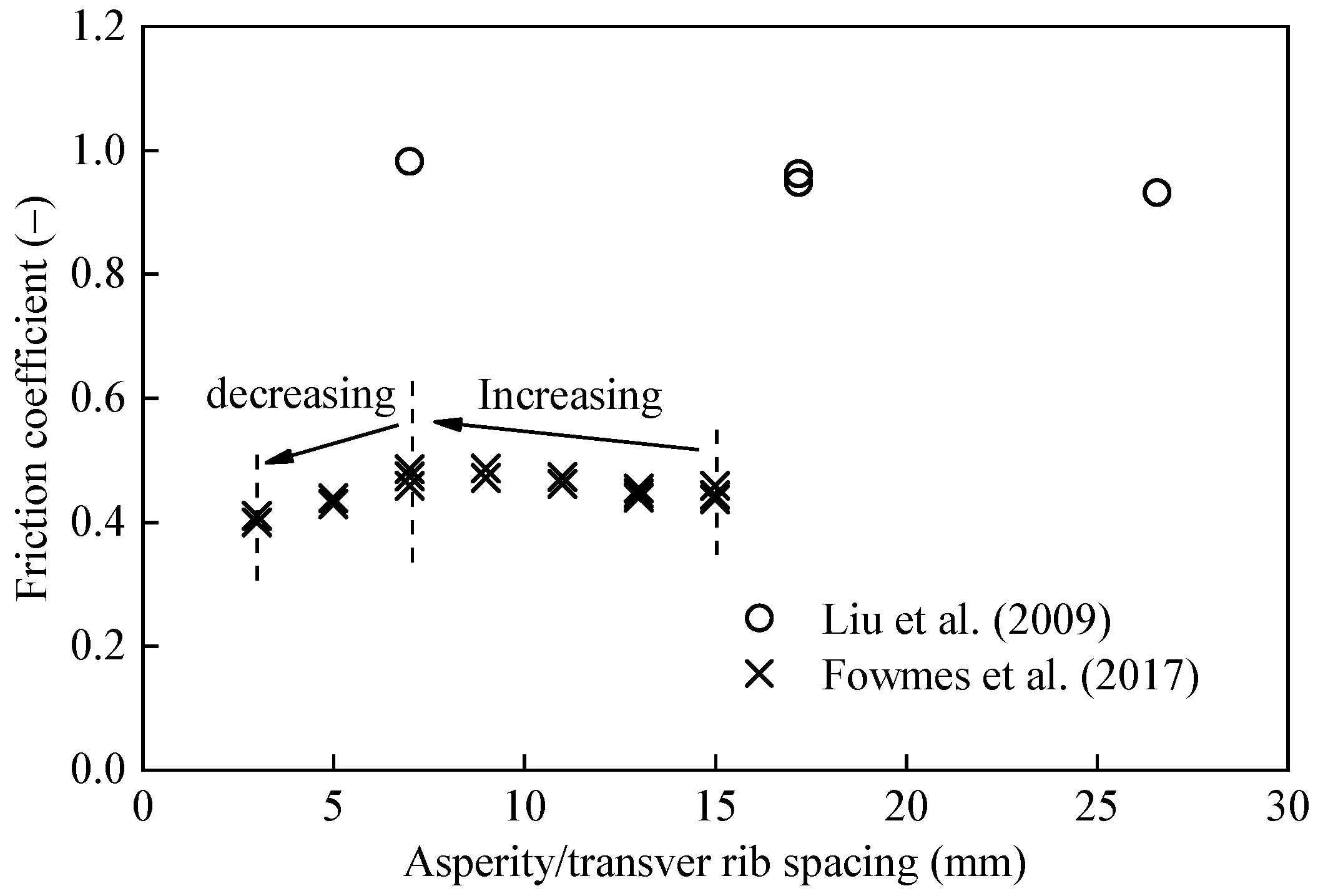

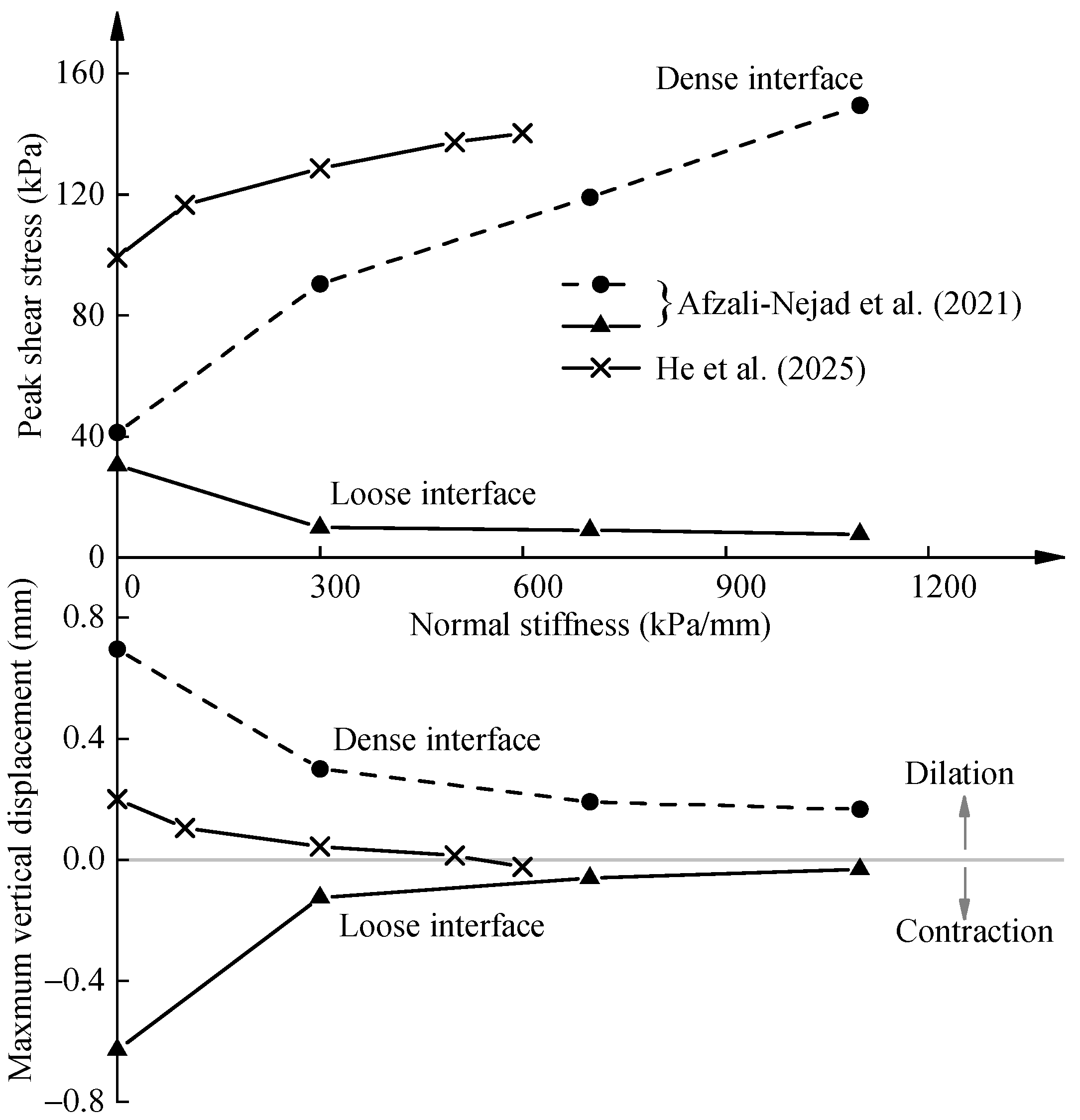

2.2. Influence of Soil and Geosynthetic Properties

2.3. Influence of Loading Conditions

2.4. Influence of Environmental Conditions

2.5. Summary of Soil–Geosynthetic Direct Shear Tests

3. Development of Numerical Modelling

3.1. Zero-Thickness Element (Goodman Element)

3.2. Thin-Layer Element (Desai Element)

3.3. Continuum Element (Solid Element)

3.4. Comparison of Zero-Thickness, Thin-Layer, and Continuum/Solid Interface Elements

3.5. Summary of the Numerical Modelling of Soil–Geosynthetic Interfaces

4. Concluding Remarks

- (1)

- The interaction between poorly graded sand and geogrids/-textile/-membranes has mainly been studied; experimental extension to cohesive soils, gravelly soils, well-graded granular soils, reinforced strips, and other emerging geosynthetic materials is encouraged.

- (2)

- Test findings on the effects of soil anisotropy and fine content, geosynthetic hardness and aperture, confining stiffness, shear rate and size, temperature, and chemical aspects need to be supplemented to clarify the influencing mechanism within the interface phenomenon.

- (3)

- Among the three interface elements, the zero-thickness element has undergone the most rapid development and has been employed in wide applications, while the thin-layer element and the continuum element are still young topics with potential development ahead.

- (4)

- The thin-layer and continuum elements are capable to obtain stress/deformation distribution within the interface, yet they exhibit sensitivity to the selection of numerical modelling parameters.

- (5)

- The primary constitutive formulations used remain conventional elastic or elastoplastic models; numerical implementations of recently developed bounding surface plasticity, hypo-plasticity, critical state laws, or machine learning-based models should be taken into consideration.

- (6)

- The zero-thickness and continuum elements are recommended for starters, given their common availability in most commercial software platforms, while researchers pursuing high-accuracy and realistic modelling may refer to thin-layer elements or newly self-developed zero-thickness elements.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bathurst, R.J.; Nernheim, A.; Walters, D.L.; Allen, T.M.; Burgess, P.; Saunders, D.D. Influence of reinforcement stiffness and compaction on the performance of four geosynthetic-reinforced soil walls. Geosynth. Int. 2009, 16, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, Y.; Bathurst, R.J.; Miyatake, H. Performance of three geogrid-reinforced soil walls before and after foundation failure. Geosynth. Int. 2015, 22, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathurst, R.J.; Lin, P.; Allen, T. Reliability-based design of internal limit states for mechanically stabilized earth walls using geosynthetic reinforcement. Can. Geotech. J. 2019, 56, 774–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, C.; Yin, J.H. Elastic analysis of soil-geosynthetic interaction. Geosynth. Int. 2001, 8, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmeira, E.M. Soil–geosynthetic interaction: Modelling and analysis. Geotext. Geomembr. 2009, 27, 368–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Bathurst, R.J. Influence of selection of soil and interface properties on numerical results of two soil–geosynthetic interaction problems. Int. J. Geomech. 2017, 17, 04016136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, J. State of the art: Mechanical behavior of soil–structure interface. Prog. Nat. Sci. 2009, 19, 1187–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Han, J.; Zhang, Z. Experimental study on performance of geosynthetic-reinforced soil model walls on rigid foundations subjected to static footing loading. Geotext. Geomembr. 2016, 44, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koerner, R.M.; Koerner, G.R. A data base, statistics and recommendations regarding 171 failed geosynthetic reinforced mechanically stabilized earth (MSE) walls. Geotext. Geomembr. 2013, 40, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, T.; Mitachi, T.; Ikeura, I. Direct shear testing method as a means for estimating geogrid-sand interface shear-displacement behavior. Soils Found. 1999, 39, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razeghi, H.R.; Ensani, A. Clayey sand soil interactions with geogrids and geotextiles using large-scale direct shear tests. Int. J. Geosynth. Ground Eng. 2023, 9, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.M.; Manjunath, V.R. Soil-geotextile interface friction by direct shear tests. Can. Geotech. J. 2000, 37, 238–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, C.S.; Lopes, M.D.L.; Caldeira, L.M. Sand-geotextile interface characterisation through monotonic and cyclic direct shear tests. Geosynth. Int. 2013, 20, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markou, I.N.; Evangelou, E.D. Shear resistance characteristics of soil–geomembrane interfaces. Int. J. Geosynth. Ground Eng. 2018, 4, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, I.R.; Sharma, J.S.; Jogi, M.B. Shear strength of geomembrane–soil interface under unsaturated conditions. Geotext. Geomembr. 2006, 24, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xenaki, V.C.; Athanasopoulos, G.A. Experimental investigation of the interaction mechanism at the EPS geofoam-sand interface by direct shear testing. Geosynth. Int. 2001, 8, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Farsakh, M.; Coronel, J.; Tao, M. Effect of soil moisture content and dry density on cohesive soil–geosynthetic interactions using large direct shear tests. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2007, 19, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, F.Y.; Wang, P.; Cai, Y.Q. Particle size effects on coarse soil-geogrid interface response in cyclic and post-cyclic direct shear tests. Geotext. Geomembr. 2016, 44, 854–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzali-Nejad, A.; Lashkari, A.; Shourijeh, P.T. Influence of particle shape on the shear strength and dilation of sand-woven geotextile interfaces. Geotext. Geomembr. 2017, 45, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzali-Nejad, A.; Lashkari, A.; Farhadi, B. Role of soil inherent anisotropy in peak friction and maximum dilation angles of four sand-geosynthetic interfaces. Geotext. Geomembr. 2018, 46, 869–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacas, B.M.; Cañizal, J.; Konietzky, H. Frictional behaviour of three critical geosynthetic interfaces. Geosynth. Int. 2015, 22, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzali-Nejad, A.; Lashkari, A.; Martinez, A. Stress-displacement response of sand–geosynthetic interfaces under different volume change boundary conditions. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2021, 147, 04021062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jotisankasa, A.; Rurgchaisri, N. Shear strength of interfaces between unsaturated soils and composite geotextile with polyester yarn reinforcement. Geotext. Geomembr. 2018, 46, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanikhah, A.; Miller, G.A.; Hatami, K. Laboratory investigation of unsaturated clayey soil-geomembrane interface behavior. Geosynth. Int. 2020, 27, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Z.; Fowmes, G. Modified stress and temperature-controlled direct shear apparatus on soil-geosynthetics interfaces. Geotext. Geomembr. 2021, 49, 825–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Z.; Fowmes, G.; Mousa, A.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, Z.; Zheng, J.; Shi, D. A new large-scale shear apparatus for testing geosynthetics-soil interfaces incorporating thermal condition. Geotext. Geomembr. 2024, 52, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzazan, S.; Keshavarz, A.; Mosallanezhad, M. Pullout behavior of polymeric strip in compacted dry granular soil under cyclic tensile load conditions. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2018, 10, 968–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Ramana, G.V.; Datta, M.; Soni, N.K.; Satyakam, R. Pullout behaviour of polymeric strips embedded in mixed recycled aggregate (MRA) from construction & demolition (C&D) waste—Effect of type of fill and compaction. Geotext. Geomembr. 2023, 51, 405–417. [Google Scholar]

- Damians, I.P.; Moncada, A.; Olivella, S.; Lloret, A.; Josa, A. Physical and 3D numerical modelling of reinforcements pullout test. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panah, A.K.; Eftekhari, Z. Shaking table tests on polymeric-strip reinforced-soil walls adjacent to a rock slope. Geotext. Geomembr. 2021, 49, 737–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathurst, R.J.; Miyata, Y.; Allen, T. LRFD Calibration of Internal Limit States for Polymer Strap MSE Walls. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2025, 151, 04024140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.J.; Wang, Y.Q.; Chen, H.X. DEM simulation of geotextile-geomembrane interface direct shear test considering the interlocking and wearing processes. Comput. Geotech. 2022, 148, 104805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Miao, C.; Zheng, Y. DEM study on shear behavior of geogrid-soil interfaces subjected to shear in different directions. Comput. Geotech. 2023, 156, 105302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meguid, M.A.; Hussein, M.G.; Ahmed, M.R.; Omeman, Z.; Whalen, J. Investigation of soil-geosynthetic-structure interaction associated with induced trench installation. Geotext. Geomembr. 2017, 45, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, S.W.; Edens, M.Q. Finite element modeling of a geosynthetic pullout test. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2003, 21, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Farsakh, M.; Ardah, A.; Voyiadjis, G. 3D Finite element analysis of the geosynthetic reinforced soil-integrated bridge system (GRS-IBS) under different loading conditions. Transp. Geotech. 2018, 15, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R.E.; Taylor, R.L.; Brekke, T.L. A model for the mechanics of jointed rock. J. Soil Mech. Found. Div. 1968, 94, 637–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, C.S.; Zaman, M.M.; Lightner, J.G.; Siriwardane, H.J. Thin-layer element for interfaces and joints. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 1984, 8, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.T.; Gui, M.W.; Pham, T.; Luong, B.T. Numerical Analysis of the Stress–Deformation Behavior of Soil–Geosynthetic Composite (SGC) Masses Under Confining Pressure Conditions. Buildings 2025, 15, 2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Pu, J.L. Application of damage model for soil–structure interface. Comput. Geotech. 2003, 30, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, J.M. Numerical modeling of soil–structure interface of a concrete-faced rockfill dam. Comput. Geotech. 2009, 36, 762–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi, M.; Annan, C.D.; Konrad, J.M. Implementation of a soil-structure interface constitutive model for application in geo-structures. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2019, 116, 714–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Damians, I.P.; Bathurst, R.J. Influence of choice of FLAC and PLAXIS interface models on reinforced soil–structure interactions. Comput. Geotech. 2015, 65, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damians, I.P.; Olivella, S.; Bathurst, R.J.; Lloret, A.; Josa, A. Modeling soil-facing interface interaction with continuum element methodology. Front. Built Environ. 2022, 8, 842495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damians, I.P.; Bathurst, R.J.; Olivella, S.; Lloret, A.; Josa, A. 3D modelling of strip reinforced MSE walls. Acta Geotech. 2021, 16, 711–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohra, B.F.; Fouad, B.A.; Mohamed, C. Soil-structure interaction interfaces: Literature review. Arab. J. Geosci. 2022, 15, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.N.; Zornberg, J.G.; Chen, T.C.; Ho, Y.H.; Lin, B.H. Behavior of geogrid-sand interface in direct shear mode. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2009, 135, 1863–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.N.; Ho, Y.H.; Huang, J.W. Large scale direct shear tests of soil/PET-yarn geogrid interfaces. Geotext. Geomembr. 2009, 27, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitanga, H.N.; Gourc, J.P.; Vilar, O.M. Interface shear strength of geosynthetics: Evaluation and analysis of inclined plane tests. Geotext. Geomembr. 2009, 27, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.W.; Chen, G.H.; Wu, J.H. The shear behavior obtained from the direct shear and pullout tests for different poor graded soil-geosynthetic systems. J. Geoengin. 2011, 6, 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Khoury, C.N.; Miller, G.A.; Hatami, K. Unsaturated soil–geotextile interface behavior. Geotext. Geomembr. 2011, 29, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, C.W.; Park, I.J.; Park, J.B. Evaluation of disturbance function for geosynthetic–soil interface considering chemical reactions based on cyclic direct shear tests. Soils Found. 2013, 53, 720–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F.B.; Vieira, C.S.; Lopes, M.D.L. Direct shear behaviour of residual soil–geosynthetic interfaces–influence of soil moisture content, soil density and geosynthetic type. Geosynth. Int. 2015, 22, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.C.; Saito, A. Interface shear strengths between geosynthetics and clayey soils. Int. J. Geosynth. Ground Eng. 2016, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, A.K.; Krishna, A.M. Experimental investigation of interface behaviour of different types of granular soil/geosynthetics. Int. J. Geosynth. Ground Eng. 2016, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infante, D.J.U.; Martinez, G.M.A.; Arrua, P.A.; Eberhardt, M. Shear strength behavior of different geosynthetic reinforced soil structure from direct shear test. Int. J. Geosynth. Ground Eng. 2016, 2, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.Y.; Wang, P.; Geng, X.Y.; Wang, J.; Lin, X. Cyclic and post-cyclic behaviour from sand–geogrid interface large-scale direct shear tests. Geosynth. Int. 2016, 23, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punetha, P.; Mohanty, P.; Samanta, M. Microstructural investigation on mechanical behavior of soil-geosynthetic interface in direct shear test. Geotext. Geomembr. 2017, 45, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowmes, G.J.; Dixon, N.; Fu, L.; Zaharescu, C.A. Rapid prototyping of geosynthetic interfaces: Investigation of peak strength using direct shear tests. Geotext. Geomembr. 2017, 45, 674–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markou, I.N. A study on geotextile—Sand interface behavior based on direct shear and triaxial compression tests. Int. J. Geosynth. Ground Eng. 2018, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namjoo, A.M.; Jafari, K.; Toufigh, V. Effect of particle size of sand and surface properties of reinforcement on sand-geosynthetics and sand–carbon fiber polymer interface shear behavior. Transp. Geotech. 2020, 24, 100403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashkari, A.; Jamali, V. Global and local sand–geosynthetic interface behaviour. Géotechnique 2021, 71, 346–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.Y.; Ying, M.J.; Yuan, G.H.; Wang, J.; Gao, Z.Y.; Ni, J.F. Particle shape effects on the cyclic shear behaviour of the soil–geogrid interface. Geotext. Geomembr. 2021, 49, 991–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qannadizadeh, A.; Shourijeh, P.T.; Lashkari, A. Laboratory investigation and constitutive modeling of the mechanical behavior of sand–GRP interfaces. Acta Geotech. 2022, 17, 4253–4275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muluti, S.S.; Kalumba, D.; Sobhee-Beetul, L.; Chebet, F. Shear strength of single and multi-layer soil–geosynthetic and geosynthetic–geosynthetic interfaces using large direct shear testing. Int. J. Geosynth. Ground Eng. 2023, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayadelen, C.; Altay, G.; Önal, Y.; Öztürk, M. Particle shape effect on interfacial properties between granular materials and geotextile. Geosynth. Int. 2023, 31, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Latha, G.M. Multi-scale understanding of sand-geosynthetic interface shear response through Micro-CT and shear band analysis. Geotext. Geomembr. 2023, 51, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kommanamanchi, V.; Mahopatra, P.K.; Duddu, S.R.; Mutha, A.; Chennarapu, H. Large-scale direct shear testing for assessing interfacial parameters of natural and recycled sand with geosynthetic reinforcements. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 442, 137598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, M.J.; Wang, J.; Liu, F.Y.; Liu, X.Y. Effect of Particle Overall Regularity on Macro-and Microscopic Cyclic Shear Behavior of Geogrid–Granular Aggregate Interface. Int. J. Geomech. 2025, 25, 04025147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Zhuang, C.; Kong, X.; Liu, B.; Zhang, F. Mechanical properties and mechanisms of soil-geotextile interface under constant normal Stiffness: Effect of freezing conditions. Geotext. Geomembr. 2025, 53, 1094–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Pan, L.; Liu, F.; Yang, Y. Shear behavior of saline soil-geotextile interfaces under freeze-thaw cycles. Geotext. Geomembr. 2025, 53, 867–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francavilla, A.; Zienkiewicz, O.C. A note on numerical computation of elastic contact problems. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 1975, 9, 913–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.X.; Yuan, H.N.; Li, Q.M.; Zhang, B.Y. Comparative Study on Interface Elements, Thin-Layer Elements, and Contact Analysis Methods in the Analysis of High Concrete-Faced Rockfill Dams. J. Appl. Math. 2013, 2013, 320890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pande, G.N.; Sharma, K.G. On joint/interface elements and associated problems of numerical ill-conditioning. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 1979, 3, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, A.; Roy, R. A comparative numerical study on soil–geosynthetic interactions using large scale direct shear test and pullout test. Int. J. Geosynth. Ground Eng. 2018, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Potts, D.M.; Zdravković, L.; Gawecka, K.A.; Tsiampousi, A. Formulation and application of 3D THM-coupled zero-thickness interface elements. Comput. Geotech. 2019, 116, 103204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Tian, Y.; Cassidy, M.J. An interface to numerically model undrained soil-structure interactions. Comput. Geotech. 2021, 138, 104327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghalamzan Esfahani, F.; Gajo, A. A zero-thickness interface element incorporating hydro-chemo-mechanical coupling and rate-dependency. Acta Geotech. 2024, 19, 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabatakis, D.A.; Hatzigogos, T.N. Analysis of creep behaviour using interface elements. Comput. Geotech. 2002, 29, 257–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, R.A.; Potts, D.M. Zero thickness interface elements—Numerical stability and application. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 1994, 18, 689–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, L.R. Finite element analysis of contact problems. J. Eng. Mech. Div. 1978, 104, 1043–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliakin, V.N.; Li, J. Insight into deficiencies associated with commonly used zero-thickness interface elements. Comput. Geotech. 1995, 17, 225–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, P.C.F.; Pyrah, I.C.; Anderson, W.F. Assessment of three interface elements and modification of the interface element in CRISP90. Comput. Geotech. 1997, 21, 315–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britto, A.M.; Gunn, M.J. CRISP90 User’s and Programmer’s Guide; Cambridge University: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Z.; Chua, K.M. Exact formulation of axisymmetric-interface-element stiffness matrix. J. Geotech. Eng. 1992, 118, 1264–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itasca. FLAC: Fast Lagrangian Analysis of Continua, User’s Guide; Itasca Consulting Group, Inc.: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkgreve, R.; Vermeer, P.A. Plaxis Scientific Manual; PLAXIS: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dassault Systemes. ABAQUS Analysis User’s Guide; Simulia Corporation: Providence, RI, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Olivella, S.; Gens, A.; Carrera, J.; Alonso, E.E. Numerical formulation for a simulator (CODE_BRIGHT) for the coupled analysis of saline media. Eng. Comput. 1996, 13, 87–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potts, D.M.; Zdravković, L.; Addenbrooke, T.I.; Higgins, K.G.; Kovačević, N. Finite Element Analysis in Geotechnical Engineering: Application; Thomas Telford: London, UK, 2001; Volume 2, p. 427. [Google Scholar]

- Zaman, M.M.U.; Desai, C.S.; Drumm, E.C. Interface model for dynamic soil-structure interaction. J. Geotech. Eng. 1984, 110, 1257–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, C.S.; Muqtadir, A.; Scheele, F. Interaction analysis of anchor-soil systems. J. Geotech. Eng. 1986, 112, 537–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, C.S.; Nagaraj, B.K. Modeling for cyclic normal and shear behavior of interfaces. J. Eng. Mech. 1988, 114, 1198–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.G.; Desai, C.S. Analysis and implementation of thin-layer element for interfaces and joints. J. Eng. Mech. 1992, 118, 2442–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, C.S.; Somasundaram, S.; Frantziskonis, G. A hierarchical approach for constitutive modelling of geologic materials. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 1986, 10, 225–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, C.S.; Rigby, D.B. Modelling and testing of interfaces. In Studies in Applied Mechanics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995; Volume 42, pp. 107–125. [Google Scholar]

- Samtani, N.C.; Desai, C.S.; Vulliet, L. An interface model to describe viscoplastic behavior. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 1996, 20, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi, M.; Annan, C.D.; Konrad, J.M.; Lashkari, A. A critical state two-surface plasticity model for gravelly soil-structure interfaces under monotonic and cyclic loading. Comput. Geotech. 2016, 80, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, D.V. Numerical studies of soil–structure interaction using a simple interface model. Can. Geotech. J. 1988, 25, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zou, D.; Kong, X. A three-dimensional state-dependent model of soil–structure interface for monotonic and cyclic loadings. Comput. Geotech. 2014, 61, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashkari, A. A simple critical state interface model and its application in prediction of shaft resistance of non-displacement piles in sand. Comput. Geotech. 2017, 88, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Tai, P.; Yin, J.H. A bounding surface model for saturated and unsaturated soil-structure interfaces. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2020, 44, 2412–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yin, Z.Y. Soil-structure interface modeling with the nonlinear incremental approach. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2021, 45, 1381–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, Z.U.; Zhang, G. Three-dimensional elasto-plastic damage model for gravelly soil-structure interface considering the shear coupling effect. Comput. Geotech. 2021, 129, 103868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghsoodi, S.; Cuisinier, O.; Masrouri, F. Non-isothermal soil-structure interface model based on critical state theory. Acta Geotech. 2021, 16, 2049–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Song, Z. An elastoplastic model for unsaturated soil-structure interfaces considering different initial states, boundary conditions and suctions. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 167, 106123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Zhou, C. A thermo-mechanical model for saturated and unsaturated soil–structure interfaces. Can. Geotech. J. 2024, 61, 2615–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, M.; Malidarreh, N.R.; Ghaseminejad, V.; Asgari, A. Seismic resilience assessment of RC superstructures on long–short combined piled raft foundations: 3D SSI modeling with pounding effects. Structures 2025, 81, 110176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrício, J.D.; Gusmão, A.D.; Ferreira, S.R.; Silva, F.A.; Kafshgarkolaei, H.J.; Azevedo, A.C.; Delgado, J.M. Settlement Analysis of Concrete-Walled Buildings Using Soil–Structure Interactions and Finite Element Modeling. Buildings 2024, 14, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Ref. No. | Soil | Geosynthetic Product | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Classification a (USCS) | Type b | Material c | |||

| Raw | Coating | |||||

| Lee and Manjunath (2000) | [12] | Beach sand | SP | GT | PET, PP | – |

| Xenaki and Athanasopoulos (2001) | [16] | Ottawa sand beach sand | – – | Geofoam | PS | – |

| Fleming et al. (2006) | [15] | Ottawa sand Sand–Bentonite mix silty sand | – – – | GM | HDPE | – |

| Abu-Farsakh et al. (2007) | [17] | Sand Clay-1 Clay-2 | SP CL, CH ML-CL | GT GG | PP PET, PP | – – |

| Liu et al. (2009) | [47,48] | Ottawa sand Gravel Laterite clay | – GP – | GT, GG | PET | PVC |

| Pitanga et al. (2009) | [49] | Silty sand | – | GM GT Geomat | HDPE PP – | – – – |

| Hsieh et al. (2011) | [50] | Quartz sand Riverbed gravel Crushed stone | SP GP GP | GT GG | PP PET | – PVC |

| Khoury et al. (2011) | [51] | Sand–glass bead mix | – | GT | PP | – |

| Vieira et al. (2013) | [13] | Silica sand | SP | GT | PET, PP | – |

| Kwak et al. (2013) | [52] | Jumunjin sand | – | GT | HDPE | – |

| Bacas et al. (2015) | [21] | Spain landfills | – | GT GM GC | PP, PE HDPE PP, HDPE | – – – – |

| Ferreira et al. (2015) | [53] | Granite residual soil | SW-SM | GG GT GC | HDPE, PET PP PET, PP | – – – |

| Wang et al. (2016) | [18] | Silica sand Gravel | SP GP | GG | PP | – |

| Chai and Saito (2016) | [54] | Mixed clayey soil Bentonite Decomposed granite | – – – | GM GT GCL | PE, PVC, HDPE PET | – – – |

| Choudhary and Krishna (2016) | [55] | Sand | SP | GT, GG | – | – |

| Infante et al. (2016) | [56] | River sand River sand | SW SM | GG GT | PVA, PP PP, PET | – – |

| Liu et al. (2016) | [57] | Fujian sand | – | GG | PP | – |

| Afzali-Nejad et al. (2017) | [19] | Angular sand | – | GT | PP | – |

| Punetha et al. (2017) | [58] | River sand | SP | GM GT | HDPE – | – – |

| Fowmes et al. (2017) | [59] | Uniform sand Mudstone clay | – CL | GM | HDPE | – |

| Markou and Evangelou (2018) | [14] | Ottawa sand Cohesive soil | SP – | GM | PVC, PET, HDPE | – |

| Afzali-Nejad et al. (2018) | [20] | Crushed sand | SP | GM GT | PVC – | – – |

| Jotisankasa and Rurgchaisri (2018) | [23] | Sand Silt Clay | SM ML CH | GT | PP, PET | – |

| Markou (2018) | [60] | Uniform sand | – | GT GT | PP, PET PET | – PVC |

| Hassanikhah et al. (2020) | [24] | Clay–silt mixture | – | GM | HDPE | – |

| Namjoo et al. (2020) | [61] | Sand | SP | GT GG GC | PP HDPE PP, HDPE | – – – – |

| Afzali-Nejad et al. (2021) | [22] | Angular sand | SP | GT GM | PP PVC | – – |

| Chao and Fowmes (2021) | [25] | Mudstone clay | CL | GDL | PP, HDPE | – – |

| Lashkari and Jamali (2021) | [62] | Sand | – | GT GM | – PVC | – – |

| Liu et al. (2021) | [63] | Crushed limestone Quartz/round gravel Spherical granular | – – – | GG | PP | – |

| Qannadizadeh et al. (2022) | [64] | Angular sand | SP | GRP | – | – |

| Razeghi and Ensani (2023) | [11] | Sand-1 Sand-2 Clay | SW, SC SP-SC CH | GT GG | PE PE | – PVC |

| Muluti et al. (2023) | [65] | River sand Clay | SP – | GT GCL | – PP | – – |

| Kayadelen et al. (2023) | [66] | Spherical sand Crushed sand Sand mixture | – – – | GT | PP | – |

| Khan and Latha (2023) | [67] | River sand Manufactured sand | SP SP | GT GM | – HDPE | – – |

| Chao et al. (2024) | [26] | Quartz sand Silica sand | – – | GM GG | – – | – – |

| Kommanamanchi et al. (2024) | [68] | Natural sand Recycled sand | SP SP | GG GT | PP, PET PET | – – |

| Ying et al. (2025) | [69] | Crushed limestone Spherical granular | – – | GG | PP | – |

| He et al. (2025) | [70] | Frozen soil | CL-ML | GT | – | – |

| Gao et al. (2025) | [71] | Saline soil | – | GT | PP | – |

| Category | Key Factor | Reference | Related Interface Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soil properties | Particle size | [16,18,55,56,58,60,62] | δp, δr, ψ, ts |

| Particle shape | [14,16,19,60,62,63,64,66,67,69] | δp, δr, ψ, ts | |

| Density | [16,17,19,22,53,56,58,62,64] | δp, ψ, ts | |

| Fine content | [11,57] | δp, δr | |

| Anisotropy | [20,49] | δp | |

| Geosynthetic properties | Surface roughness | [21,24,59,60,64] | δp, ψ, ts |

| Configuration | [47,48,50,53,55,56,59,68] | δp, δr, ψ, ts | |

| Density | [16,54] | δp, δr | |

| Loading conditions | Cyclic loading | [12,13,18,52,57,63,71] | δp, δr, ψ, ts |

| Confining stiffness | [22,70] | δp, δr, ψ, ks, kn, ts | |

| Shearing rate | [24,58] | δp, δr, ψ, ks | |

| Shear box size | [56,60] | – | |

| Environmental conditions | Suction/moisture | [11,15,17,23,24,25,26,51,53,54,58,70] | δp, δr, ψ, ts |

| Temperature | [25,26,70,71] | δp, δr, ψ, ts | |

| Chemical/pH | [52] | δp, δr, ψ |

| Element Type | Reference and Ref. No. | Constitutive Law | Modelling Scenario | Platform | Para. No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-thickness element | Hu and Pu (2003) [40] | Damage Elastoplasticity | Direct shear test and pullout test | – | 9 |

| Zhang and Zhang (2009) [41] | Damage Elastoplasticity | Slide block test, direct shear test, and CFRD | – | 12 | |

| Yu et al. (2015) [43] | Mohr–Coulomb criterion | Unit cells and concrete panel segment | FLAC, PLAXIS | 5 | |

| Yu and Bathurst (2017) [6] | Mohr–Coulomb criterion | Pullout test and GT-reinforced soil layer over a void | FLAC | 5 | |

| Abu-Farsakh et al. (2018) [36] | Mohr–Coulomb criterion | Integrated bridge system | PLAXIS | 5 | |

| Hegde and Roy (2018) [75] | Mohr–Coulomb criterion | Direct shear test and pullout test | PLAXIS | 5 | |

| Cui et al. (2019) [76] | Two-surface hardening | Triaxial heating test | ICFEP | 17 | |

| Liu et al. (2021) [77] | Elastic–perfectly plastic | Slide block test, T-bar penetration, and embedded chain link | ABAQUS | 4 | |

| Ghalamzan Esfahani and Gajo (2024) [78] | Chemo-mechanical coupled Cam-Clay | Casagrande direct shear test | ABAQUS | 23 | |

| Thin-layer element | Karabatakis and Hatzigogos (2002) [79] | Elasto- viscoplasticity | Creep shear test | FORTRAN | 7 |

| Qian et al. (2013) [73] | Linear elasticity | CFRD | – | 2 | |

| Saberi et al. (2019) [42] | Two-surface plasticity | Slide block test, pullout test, and CFRD | ABAQUS | 11 | |

| Continuum element | Damians et al. (2021) [45] | Mohr–Coulomb criterion | MSE wall | CODE_BRIGHT | 5 |

| Damians et al. (2022) [44] | Drucker–Prager criterion | Soil–facing interaction | CODE_BRIGHT | 5 | |

| Damians et al. (2024) [29] | Mohr–Coulomb criterion | Steel/PET trip pullout test | CODE_BRIGHT | 5 |

| Element Type | 2D Representation | Stress Components | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

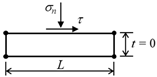

| Zero-thickness element |  | Normal stress σn and tangential stress τ | Simple and practicable, commonly available in FE codes, able to model complex shear behaviour | Numerical instability, particular constitutive law, hard to model separation |

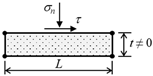

| Thin-layer element |  | Normal stress σn and tangential stress τ | Physical representation, numerical stability, able to model complex shear behaviour | Requiring small thickness (0.01 < t/L < 0.1), particular constitutive law, hard to model separation |

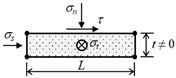

| Continuum element |  | Normal stress σn, horizontal stress σs, out-of-plane stress σt, and tangential stress τ | Physical representation, numerical stability, compatible with general constitutive laws | Careful selection of material law and parameters, hard to model separation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xiao, S.; Damians, I.P.; Hu, W. A Review of the Soil–Geosynthetic Interface Direct Shear Test and Numerical Modelling. Buildings 2026, 16, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010043

Xiao S, Damians IP, Hu W. A Review of the Soil–Geosynthetic Interface Direct Shear Test and Numerical Modelling. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010043

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Shuxiong, Ivan P. Damians, and Wei Hu. 2026. "A Review of the Soil–Geosynthetic Interface Direct Shear Test and Numerical Modelling" Buildings 16, no. 1: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010043

APA StyleXiao, S., Damians, I. P., & Hu, W. (2026). A Review of the Soil–Geosynthetic Interface Direct Shear Test and Numerical Modelling. Buildings, 16(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010043