How Time-of-Use Tariffs and Storage Costs Shape Optimal Hybrid Storage Portfolio in Buildings

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

1.2. Literature Review

- I

- Developing a life-cycle design framework for a hybrid storage system systematically considering the non-linear characteristics in operation.

- I

- Investigating the impact of diverse TOU tariff scenarios on the optimal portfolio of hybrid storage for commercial buildings.

- I

- Assessing the long-term economic robustness of different storage configurations under different storage capacity costs, providing forward-looking insights for making future-resilient investment decisions.

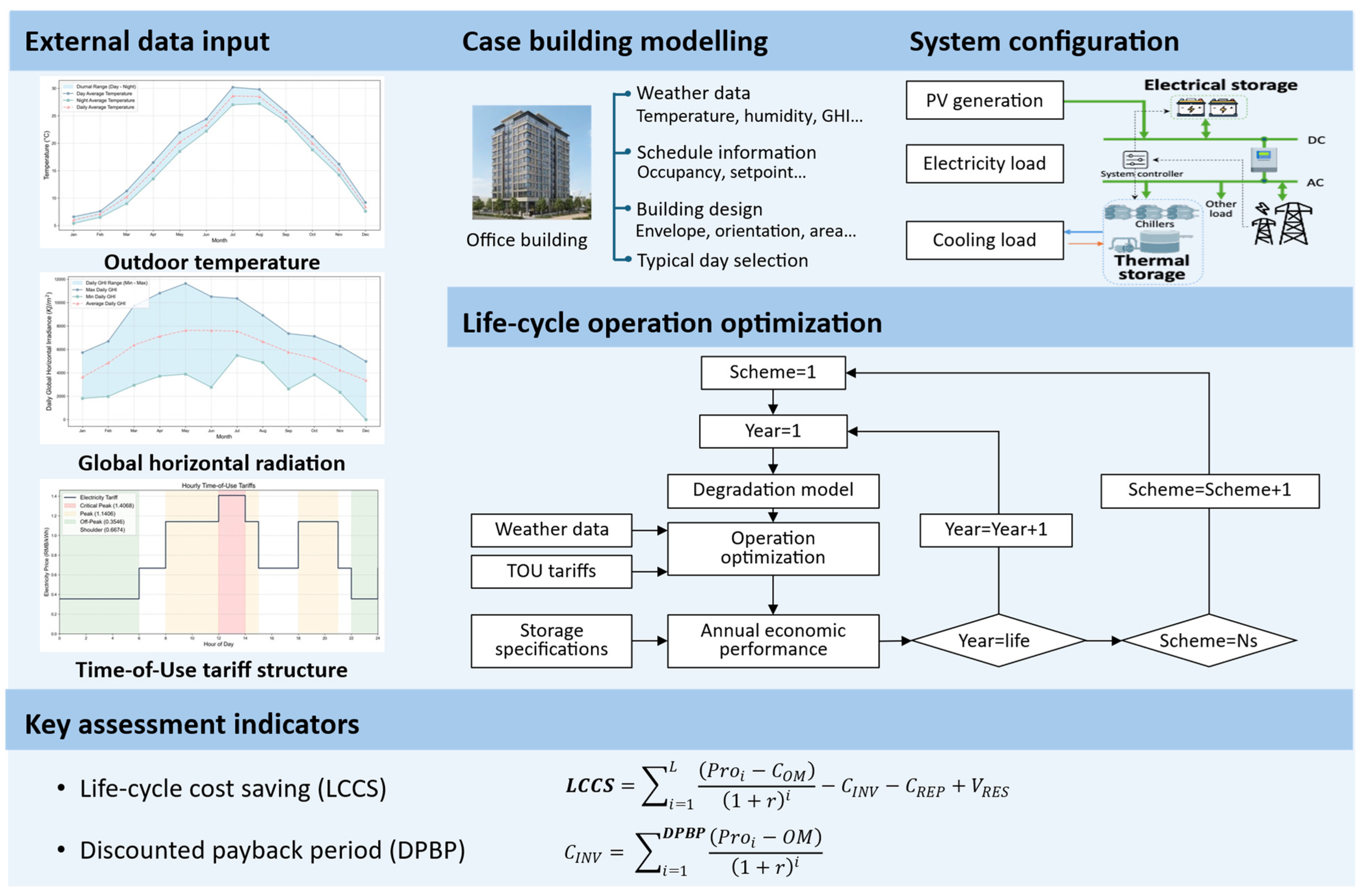

2. Methodology

2.1. Overall Framework

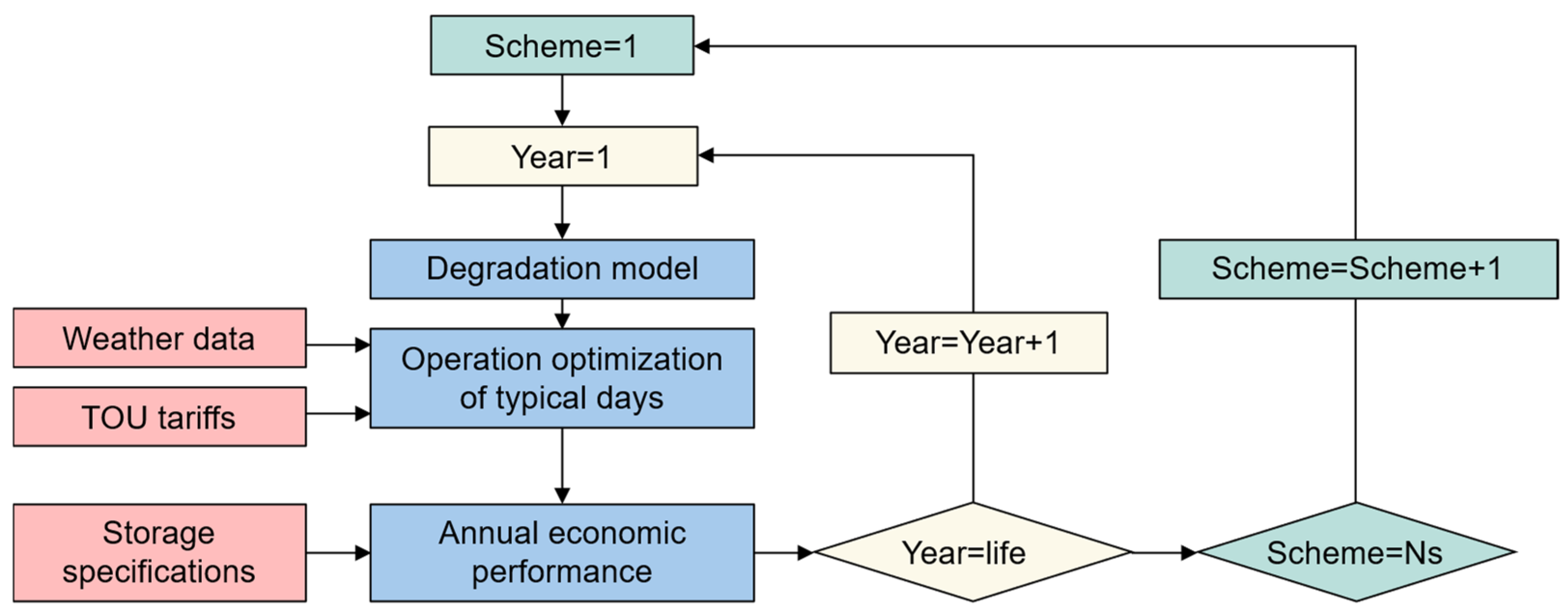

2.2. Daily Operation Optimization

2.3. Life-Cycle Assessment

2.3.1. Degradation Models and Key Assessment Indicators

2.3.2. Typical Day Selection

3. Validation Arrangement of Case Study

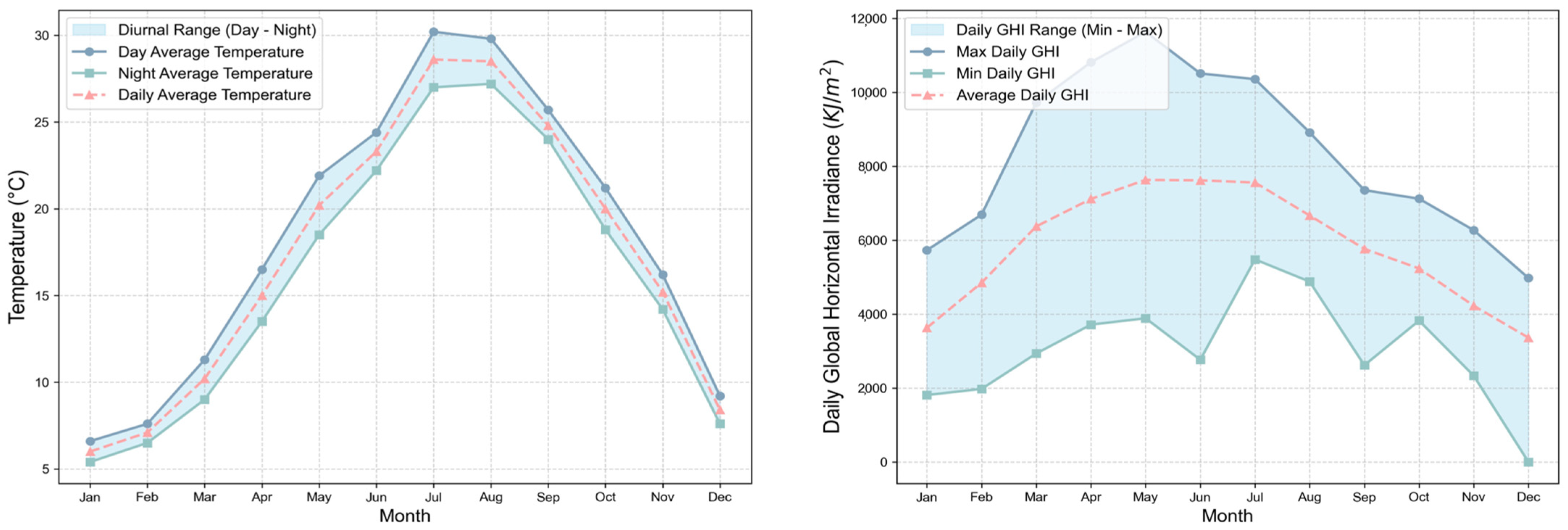

3.1. Test Scenario and Building Modeling

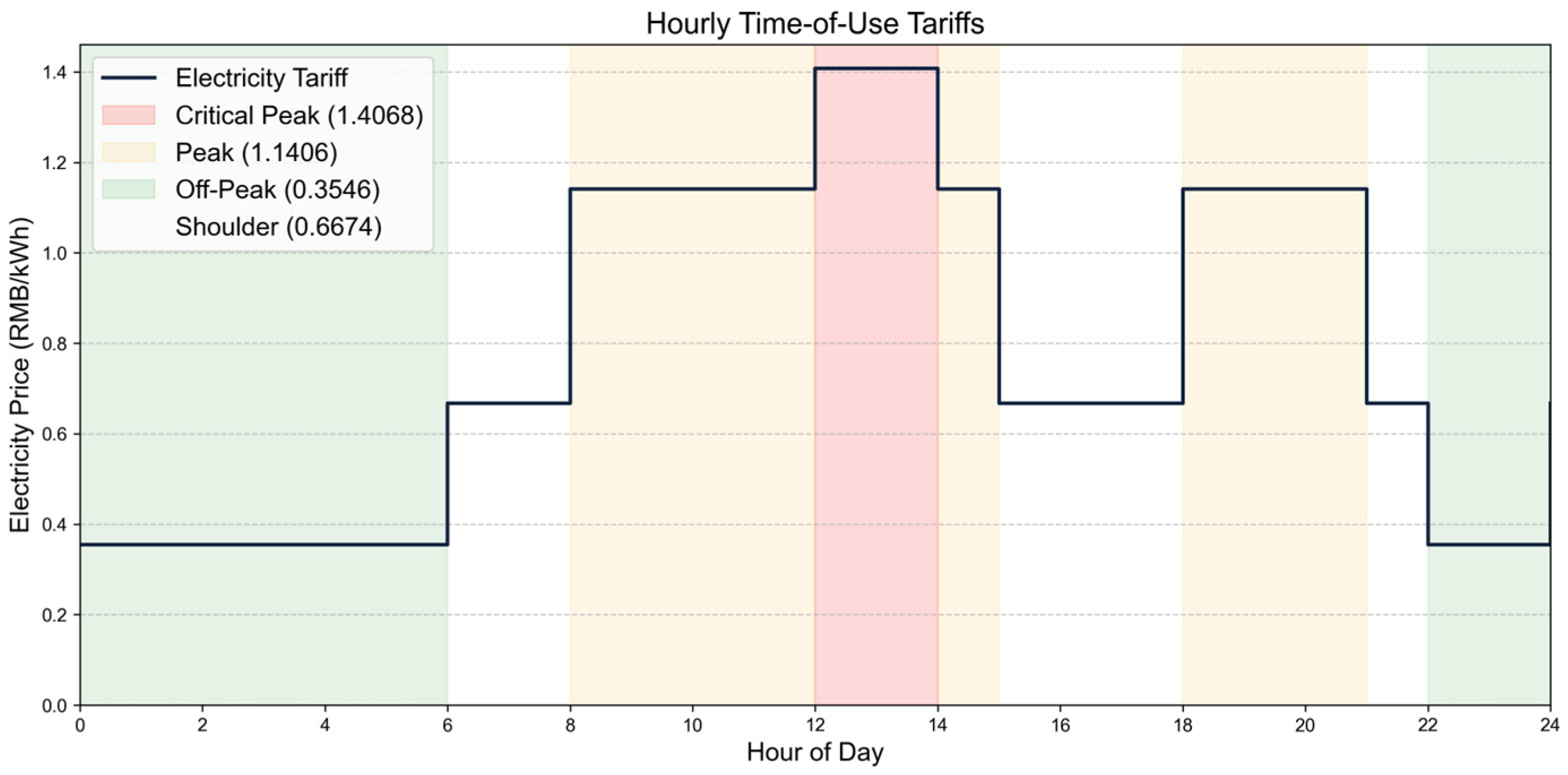

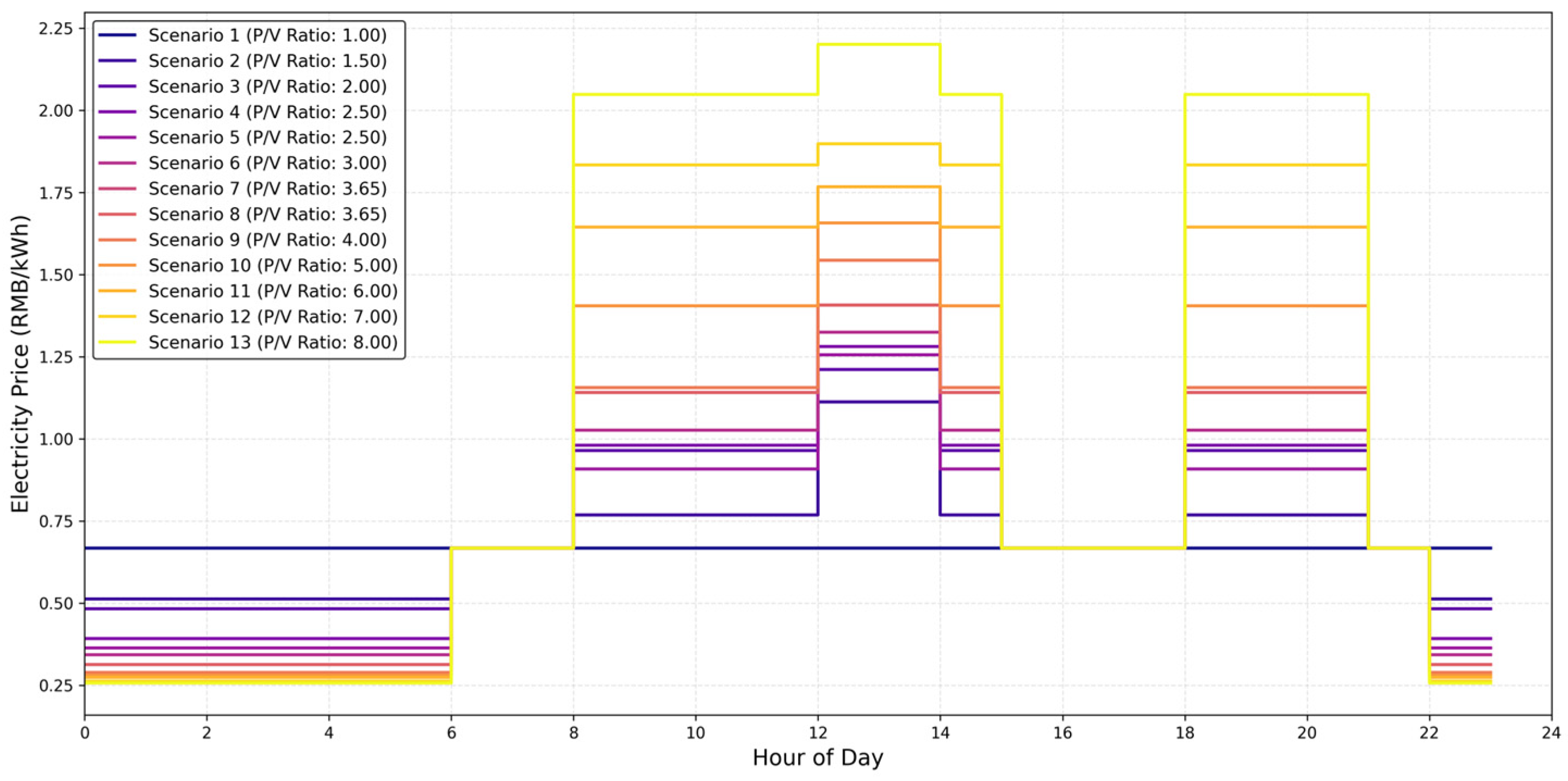

3.2. Different TOU Tariff Scenarios and Specifications of Storage System

4. Results and Analysis

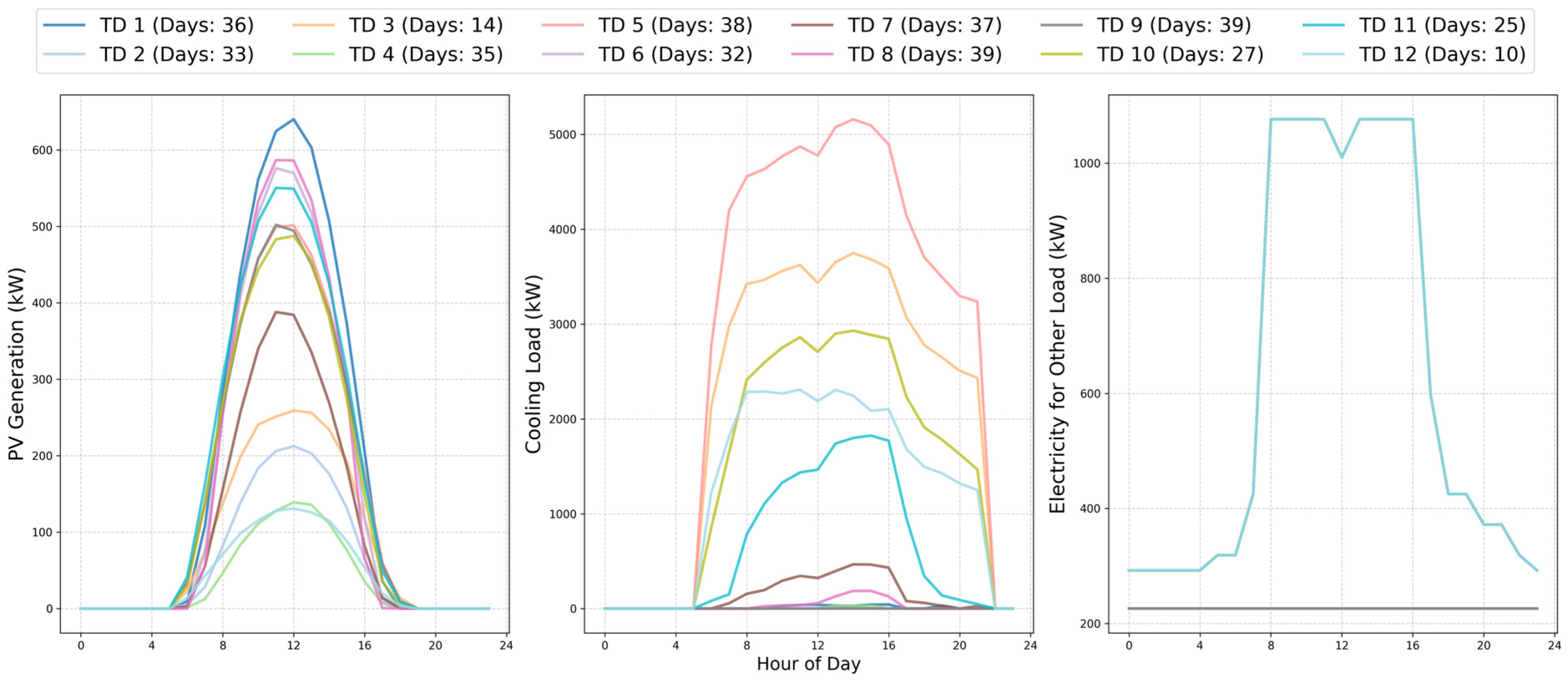

4.1. Clustering Results for Selecting Typical Days

4.2. Optimization Results of Hybrid Storage Systems

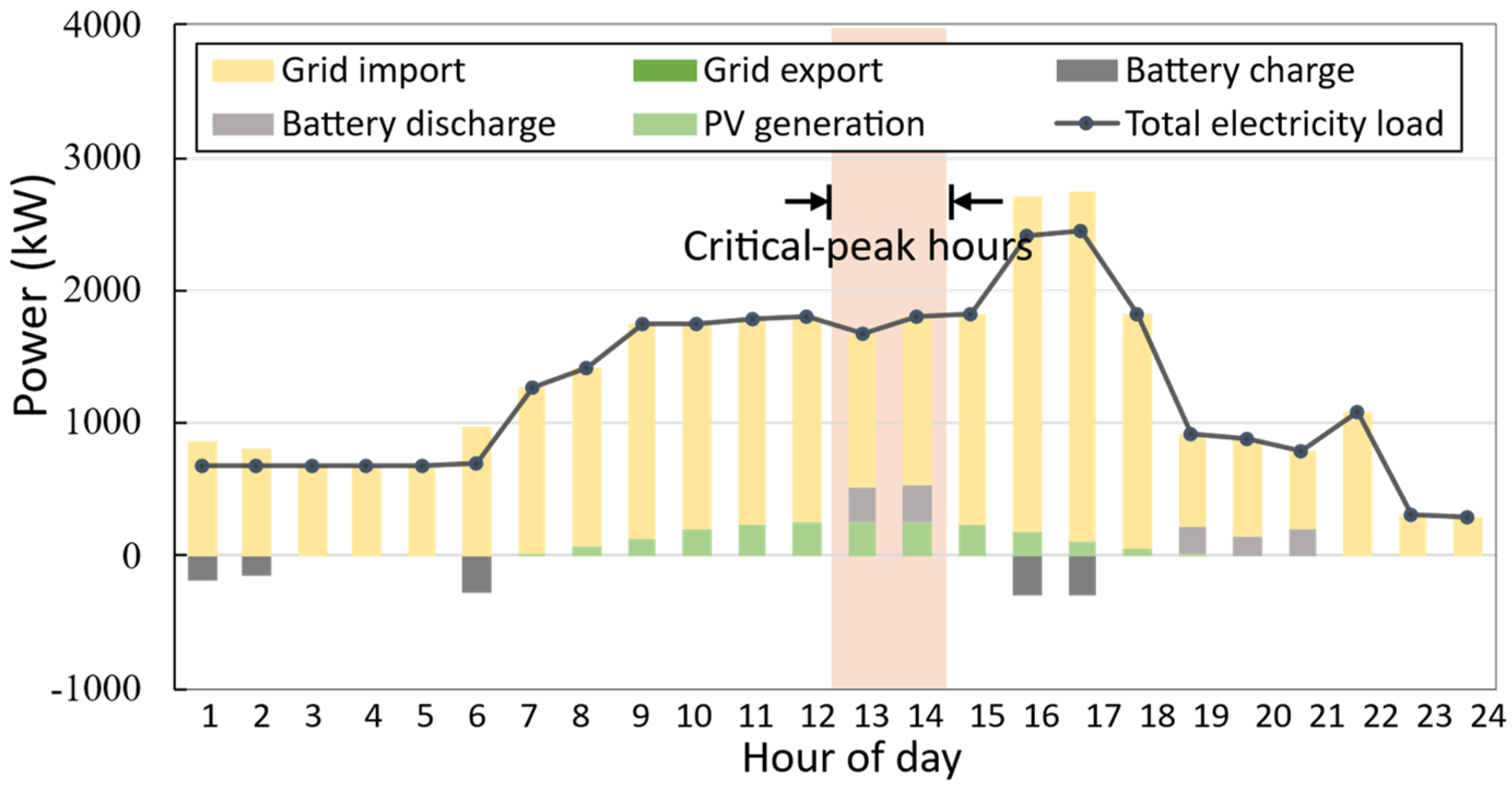

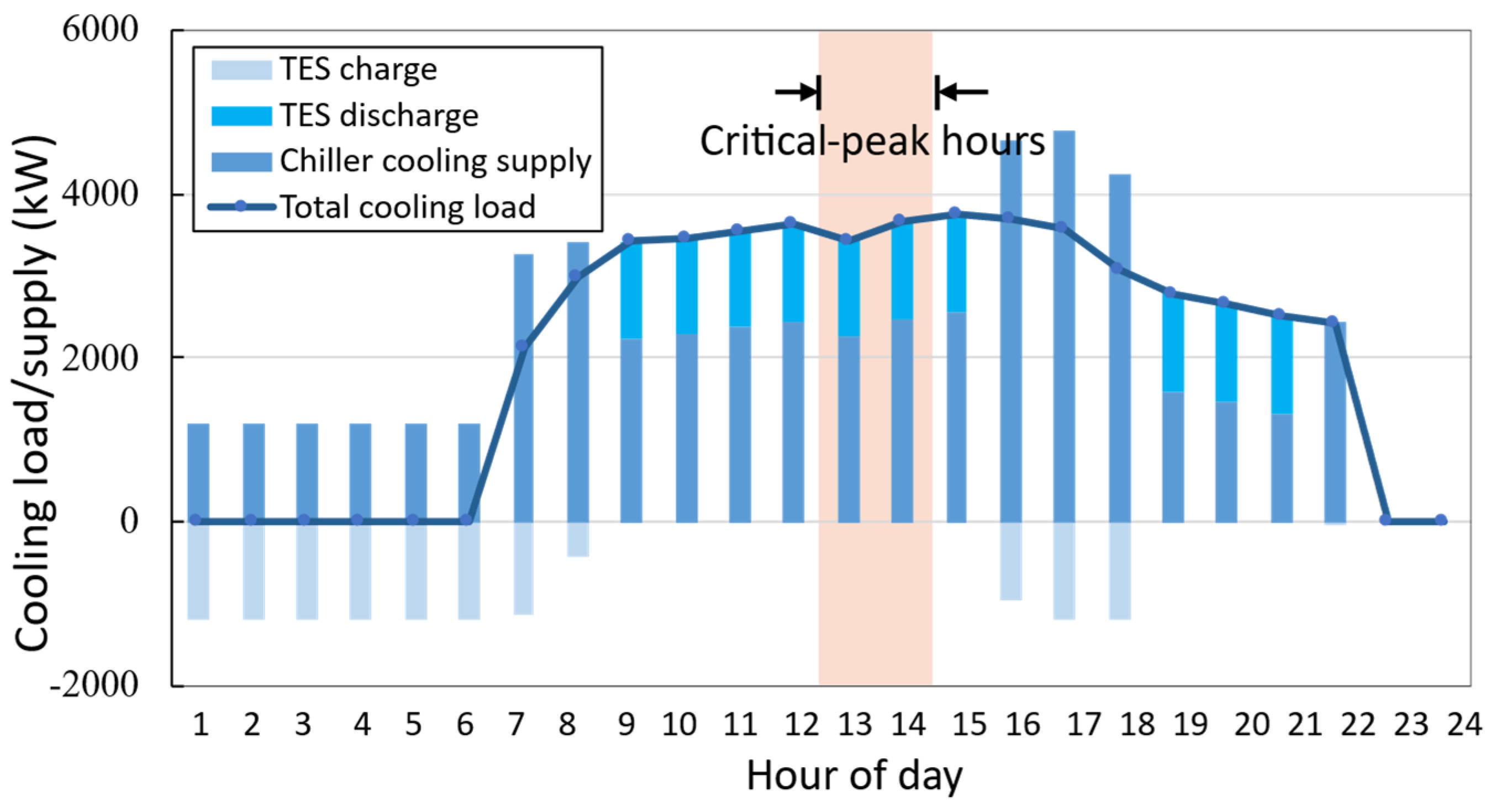

4.2.1. Operation Optimization of Typical Days

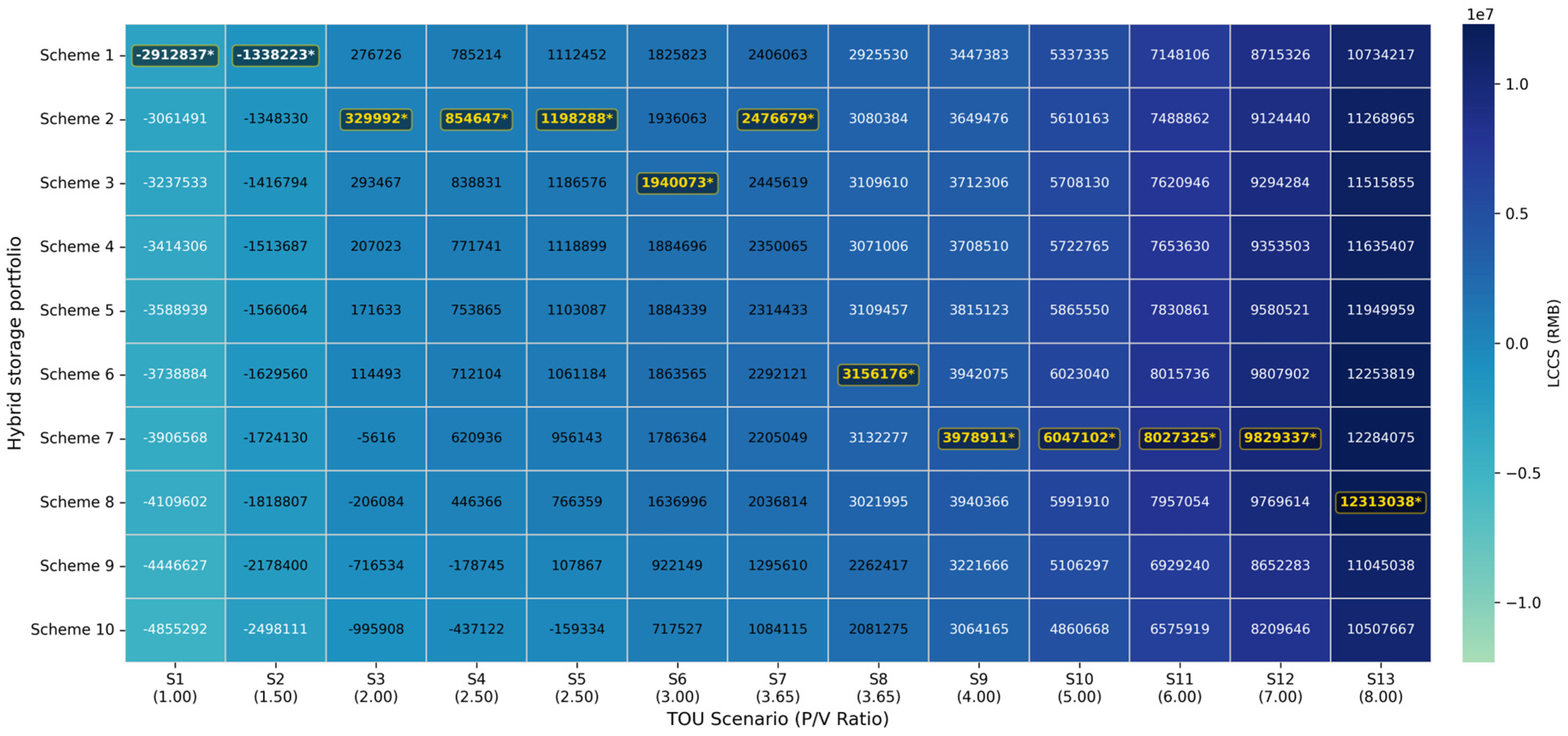

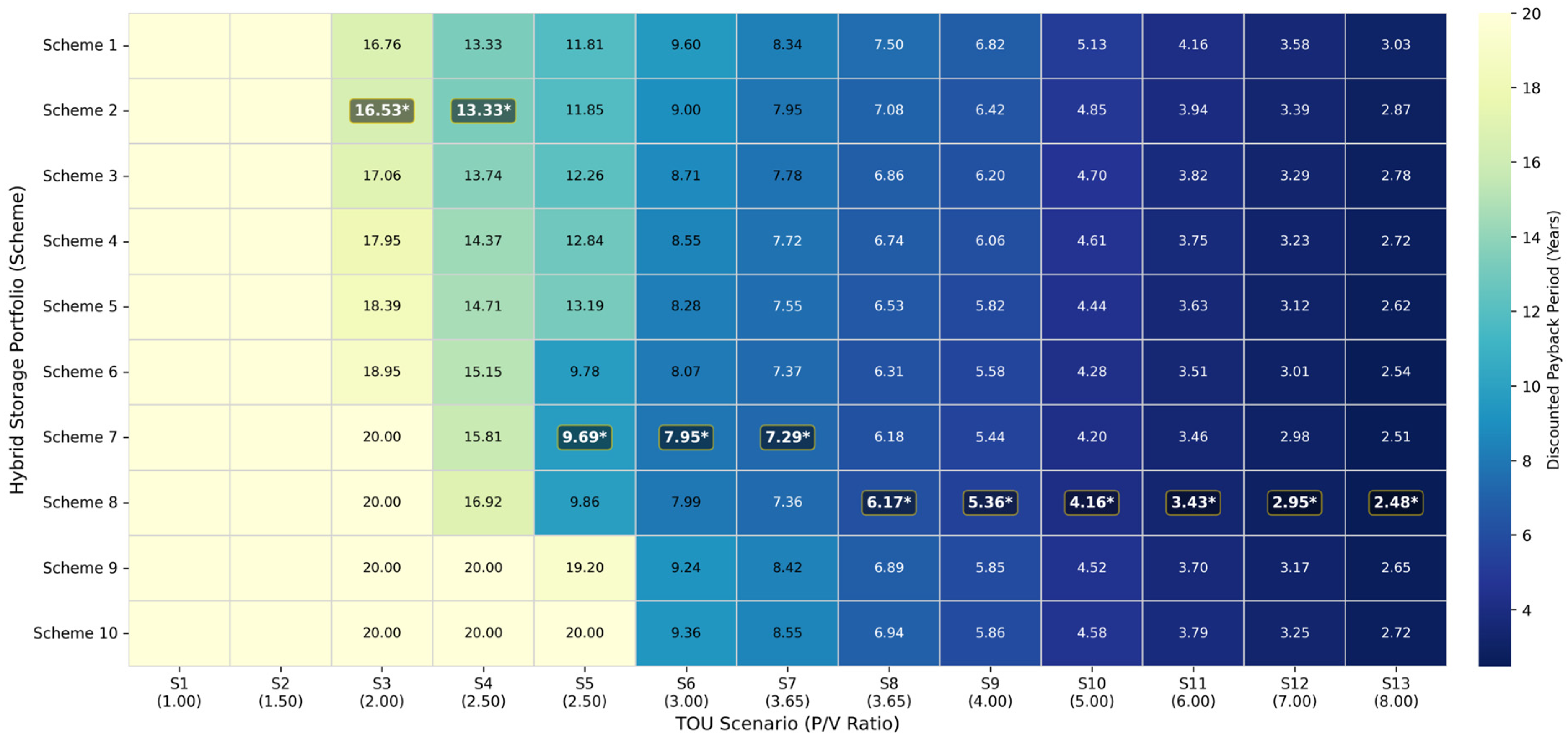

4.2.2. Optimal Hybrid Storage Portfolio Under Different TOU Tariffs

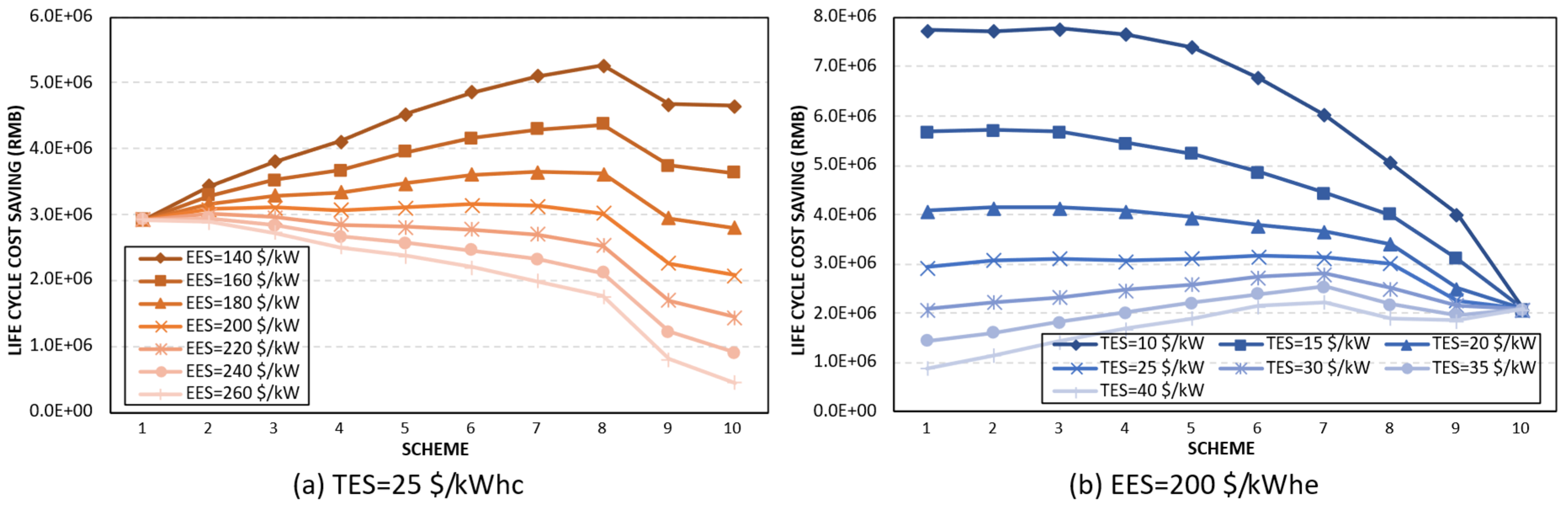

4.2.3. Optimal Hybrid Storage Portfolio Under Different Storage Costs

5. Conclusions

- A multi-scenario, life-cycle optimization framework is developed by incorporating daily operation optimization model considering storage degradation and system dynamic efficiencies. A multi-criteria evaluation considering both life-cycle cost savings and the discounted payback period is effective and required for the investment decision. While battery-dominant schemes generally achieve the shortest DPBP (as low as 2.48 years in S13), cooling storage-dominant schemes can sometimes offer better long-term LCCS under medium P/V ratios (S5–S7) due to battery degradation and replacement costs.

- The economic viability of the storage system is highly sensitive to the structure of the TOU tariff, particularly the P/V ratio and the presence of critical-peak pricing. As the P/V ratio increases, the profitability of the storage system is significantly enhanced, driving the optimal portfolio towards battery-dominant schemes due to its quick response capabilities. When the P/V ratio is at intermediate levels, the presence of a high critical price period, which is typically limited and coincides with high cooling demand, pushes the optimal portfolio towards cooling storage dominance.

- The optimal portfolio is highly sensitive to storage capacity cost fluctuations. An increase in battery capacity cost beyond 200 USD/kWhe can cause the optimal scheme to shift towards cooling storage-dominant portfolios. Conversely, if the cooling storage capacity cost exceeds 20 USD/kWhc, the optimal portfolio shifts back to battery-dominant schemes.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| TOU | Time-of-Use tariff |

| FIT | Feed-in tariff |

| TES | Thermal energy storage |

| BESS | Battery energy storage systems |

| SOC | State of Charge of battery |

| COP | Coefficient of performance |

| HVAC | Heating, ventilation and air conditioning |

| LCCS | Life cycle cost saving |

| DPBP | Discounted payback period |

| PLR | Part load ratio |

| GHI | Global horizontal irradiance |

| DHI | Diffuse horizontal irradiance |

| TD | Typical day |

| Power imported from the grid | |

| Power exported to the grid | |

| Charging rate of battery | |

| Discharging rate of battery | |

| Charging efficiency | |

| Discharging efficiency | |

| Cooling load | |

| Rated cooling capacity of chiller | |

| Charging rate of thermal energy storage | |

| Discharging rate of thermal energy storage | |

| Stored energy | |

| Storage efficiency | |

| Rated storage capacity |

References

- Impram, S.; Varbak Nese, S.; Oral, B. Challenges of renewable energy penetration on power system flexibility: A survey. Energy Strategy Rev. 2020, 31, 100539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Hodge, B.-M. Enhancing Power System Operational Flexibility with Flexible Ramping Products: A Review. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2017, 13, 1652–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Wang, S.; Li, H. Flexibility categorization, sources, capabilities and technologies for energy-flexible and grid-responsive buildings: State-of-the-art and future perspective. Energy 2021, 219, 119598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Energy Efficiency 2024; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-efficiency-2024 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Costa, R.; Silva, R.; Faia, R.; Gomes, L.; Faria, P.; Vale, Z. Empowering energy management in smart buildings: A comprehensive study on distributed energy storage systems for Sustainable consumption. Energy Build. 2024, 324, 114953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Ocłoń, P.; Klemeš, J.J.; Michorczyk, P.; Pielichowska, K.; Pielichowski, K. Renewable energy systems for building heating, cooling and electricity production with thermal energy storage. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 165, 112560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Wang, S. Life-cycle economic analysis of thermal energy storage, new and second-life batteries in buildings for providing multiple flexibility services in electricity markets. Energy 2023, 264, 126270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Optimal sizing of grid-connected photovoltaic battery systems for residential houses in Australia. Renew. Energy 2019, 136, 1245–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, T.; Elia Campana, P.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Dai, Y. A techno-economic sizing method for grid-connected household photovoltaic battery systems. Appl. Energy 2020, 269, 115106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Gou, Z. Hybrid forecasting and optimization framework for residential photovoltaic-battery systems: Integrating data-driven prediction with multi-strategy scenario analysis. Build. Simul. 2025, 18, 1587–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, M.; Khorsandi, A.; Vahidi, B.; Hosseinian, S.H.; Malakmahmoudi, A. Optimal sizing of battery energy storage in a microgrid considering capacity degradation and replacement year. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2021, 195, 107170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Kang, L.; Liu, Y. Optimal configuration of battery energy storage system with multiple types of batteries based on supply-demand characteristics. Energy 2020, 206, 118093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Peng, J.; Cao, J.; Yin, R.; Song, J.; Yuan, Y. Characterization and prediction of demand response potential of air conditioning systems integrated with chilled water storage. Energy Build. 2024, 323, 114805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarragona, J.; Pisello, A.L.; Fernández, C.; Cabeza, L.F.; Payá, J.; Marchante-Avellaneda, J.; de Gracia, A. Analysis of thermal energy storage tanks and PV panels combinations in different buildings controlled through model predictive control. Energy 2022, 239, 122201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, X.; Li, H.; Wang, S. Optimal design of energy-flexible distributed energy systems and the impacts of energy storage specifications under evolving time-of-use tariff in cooling-dominated regions. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Kuang, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhang, T. Optimal sizing and techno-economic analysis of the hybrid PV-battery-cooling storage system for commercial buildings in China. Appl. Energy 2024, 355, 122231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Tian, Z.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, H. Flexible dispatch of a building energy system using building thermal storage and battery energy storage. Appl. Energy 2019, 243, 274–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Wen, L.; Niu, J.; Lu, Y. Typical daily scenario extraction method based on key features to promote building renewable energy system optimization efficiency. Renew. Energy 2024, 236, 121420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmati, S.; Ghaderi, S.F.; Ghazizadeh, M.S. Sustainable energy hub design under uncertainty using Benders decomposition method. Energy 2018, 143, 1029–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütz, T.; Schraven, M.H.; Fuchs, M.; Remmen, P.; Müller, D. Comparison of clustering algorithms for the selection of typical demand days for energy system synthesis. Renew. Energy 2018, 129, 570–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsido, C.; Bischi, A.; Silva, P.; Martelli, E. Two-stage MINLP algorithm for the optimal synthesis and design of networks of CHP units. Energy 2017, 121, 403–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, N.; DiOrio, N.; Freeman, J.; Gilman, P.; Janzou, S.; Neises, T.; Wagner, M. System Advisor Model (SAM) General Description (Version 2017.9.5); National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Goel, S.; Rosenberg, M.; Athalye, R.; Xie, Y.; Wang, W.; Hart, R.; Zhang, J.; Mendon, V. Enhancements to ASHRAE Standard 90.1 Prototype Building Models; Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL): Richland, WA, USA, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Meiers, J.; Frey, G. Interfacing TRNSYS with MATLAB for Building Energy System Optimization. Energies 2025, 18, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, C.; Wang, S. An adaptive full-range decoupled ventilation strategy for buildings with spaces requiring strict humidity control and its applications in different climatic conditions. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 52, 101838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, V.N.; Cui, X.; Stroebl, F.; Uppaluri, M.; Onori, S.; Chueh, W.C. A decade of insights: Delving into calendar aging trends and implications. Joule 2025, 9, 101796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scenario | Critical Peak | Peak | Shoulder | Off-Peak (Valley) | Peak-to-Valley Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | - | - | 0.667 | - | 1.00 |

| 2 | 1.112 | 0.768 | 0.667 | 0.512 | 1.50 |

| 3 | 1.211 | 0.964 | 0.667 | 0.482 | 2.00 |

| 4 | 1.281 | 0.980 | 0.667 | 0.392 | 2.50 |

| 5 | 1.255 | 0.908 | 0.667 | 0.363 | 2.50 |

| 6 | 1.324 | 1.026 | 0.667 | 0.342 | 3.00 |

| 7 | - | 1.141 | 0.667 | 0.313 | 3.65 |

| 8 | 1.407 | 1.141 | 0.667 | 0.313 | 3.65 |

| 9 | 1.543 | 1.156 | 0.667 | 0.289 | 4.00 |

| 10 | 1.657 | 1.405 | 0.667 | 0.281 | 5.00 |

| 11 | 1.767 | 1.644 | 0.667 | 0.274 | 6.00 |

| 12 | 1.898 | 1.834 | 0.667 | 0.262 | 7.00 |

| 13 | 2.201 | 2.048 | 0.667 | 0.256 | 8.00 |

| System | Description | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| TES | Capacity cost | 70.3–281.3 | RMB/kWhc |

| Storage duration | 8 | h | |

| Operation and maintenance cost | 0.7% of investment cost | per year | |

| Energy storage efficiency | 0.998 | - | |

| Lifespan | 20 | years | |

| Efficiency degradation rate α | 0.002 | - | |

| BESS | Capacity cost | 984.2~1687.2 | RMB/kWhe |

| Storage duration | 2 | h | |

| Operation and maintenance cost | 0.5% of investment cost | per year | |

| Calendar life (normal corrosion) | 10 [26] | years | |

| Charging/discharging efficiency | 0.95 | - |

| Scenario | P/V Ratio | Cooling Storage | Battery Storage | LCCS | DPBP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.00 | 0.00% | 0.00% | - | - |

| 2 | 1.50 | 0.00% | 0.00% | - | - |

| 3 | 2.00 | 88.89% | 11.11% | 329,991.93 | 16.53 |

| 4 | 2.50 | 88.89% | 11.11% | 854,646.82 | 13.33 |

| 5 | 2.50 | 88.89% | 11.11% | 1,198,287.95 | 9.69 |

| 6 | 3.00 | 77.78% | 22.22% | 1,940,072.69 | 7.95 |

| 7 | 3.65 | 88.89% | 11.11% | 2,476,678.68 | 7.29 |

| 8 | 3.65 | 44.44% | 55.56% | 3,156,176.34 | 6.17 |

| 9 | 4.00 | 33.33% | 66.67% | 3,978,911.34 | 5.36 |

| 10 | 5.00 | 33.33% | 66.67% | 6,047,102.24 | 4.16 |

| 11 | 6.00 | 33.33% | 66.67% | 8,027,325.16 | 3.43 |

| 12 | 7.00 | 33.33% | 66.67% | 9,829,336.87 | 2.95 |

| 13 | 8.00 | 22.22% | 77.78% | 12,313,038.33 | 2.48 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Z. How Time-of-Use Tariffs and Storage Costs Shape Optimal Hybrid Storage Portfolio in Buildings. Buildings 2026, 16, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010042

Tang H, Zhang Y, Zheng Z. How Time-of-Use Tariffs and Storage Costs Shape Optimal Hybrid Storage Portfolio in Buildings. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010042

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Hong, Yingbo Zhang, and Zhuang Zheng. 2026. "How Time-of-Use Tariffs and Storage Costs Shape Optimal Hybrid Storage Portfolio in Buildings" Buildings 16, no. 1: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010042

APA StyleTang, H., Zhang, Y., & Zheng, Z. (2026). How Time-of-Use Tariffs and Storage Costs Shape Optimal Hybrid Storage Portfolio in Buildings. Buildings, 16(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010042