1. Introduction

The aesthetic quality of interior environments is fundamentally shaped by visually driven and cognitively mediated processes, through which users interpret materials, forms, and spatial configurations to construct environmental meaning [

1,

2,

3]. As an essential interface between individuals and their surroundings, furniture significantly influences spatial perception, comfort appraisal, and environmental satisfaction [

4]. Visual attributes—such as material texture, contour geometry, and structural detailing—serve as primary cues guiding perceptual judgments, with visually salient elements eliciting denser fixation patterns and longer gaze durations [

5]. These mechanisms underscore the importance of understanding how users visually engage with the material and structural characteristics of furniture within residential settings.

Recent advancements in eye-tracking research have contributed valuable insights into visual attention patterns across various furniture typologies and interior environments. Prior studies have examined stylistic cognition [

6,

7], morphological features [

2,

8], material and color perception [

9,

10], and interactive smart-furniture interfaces [

11,

12,

13]. Collectively, these works highlight the utility of tracking gaze behaviors to reveal perceptual preferences and emotional responses in design evaluation. Methodologically, eye-tracking studies increasingly integrate AOI (Area of Interest) -based analyses, statistical modeling, VR technologies, multimodal bio-signal measurement, and subjective questionnaires, resulting in more rigorous, data-driven decision-making frameworks for interior design research [

14,

15,

16].

Although eye-tracking technology has been widely applied in studies of visual cognition related to furniture and interior environments, systematic empirical research focusing on children’s furniture remains limited. Existing studies predominantly address adult furniture or general interior scenes, with emphasis on overall style, form, or spatial perception, while children’s furniture—as a safety-sensitive product category—has received comparatively little attention from a visual cognition perspective. In particular, the combined effects of material textures and safety-critical structural elements (such as guardrails, edges, and structural joints) on visual salience, attention allocation, and preference formation have not yet been systematically examined. Moreover, most prior research remains at a global level of analysis, lacking fine-grained, component-level investigation of children’s beds, which makes it difficult to explain what users attend to first and why during safety-related visual judgments. In addition, studies that integrate objective eye-tracking metrics with subjective evaluations to verify the consistency between visual behavior and user intention are still scarce. From the perspectives of visual salience theory and safety perception mechanisms, this gap is particularly critical, as the visual prioritization of guardrails and structural components directly shapes users’ perceived safety and usability assessments.

Building on the above gaps, it is particularly necessary to introduce eye-tracking in children’s bed research because children’s beds are safety-sensitive furniture: guardrails, structural joints, and exposed material surfaces directly shape parents’ rapid risk appraisal and the formation of perceived safety and trust. However, current design evaluation often relies on experience, code-compliance checks, or questionnaire-based preference outcomes, providing limited process-level evidence of what users attend to first and how safety perception and preference are formed. To address this limitation, this study develops a multi-level eye-tracking framework to systematically examine users’ visual attention and preferences toward children’s solid-wood beds across three dimensions: (1) material attributes, (2) bed typologies, and (3) component-level morphological features. By integrating eye-movement metrics with Likert-scale subjective evaluations, the study aims to (1) quantify the hierarchical structure of visual attractiveness in children’s bed design elements; (2) clarify the mapping relationships between material textures/functional structures and attention allocation; and (3) elucidate the cognitive mechanisms linking initial fixation, sustained attention, and preference formation, thereby translating “safety” and “function” into measurable and verifiable evidence for interior-furniture design decisions.

This integrated approach provides empirical evidence for optimizing children’s furniture design, supporting safer, more coherent, and user-centered interior environments [

17].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all relevant ethical guidelines for research involving human participants. The research protocol, including participant recruitment, data collection, and informed consent procedures, was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Nanjing Forestry University. All participants were informed of the study purpose and procedures and provided written informed consent prior to participation. Participation was voluntary, and all data were anonymized to ensure privacy and confidentiality.

2.2. Participant Selection

A total of 42 participants (20 males and 22 females), aged 22–50 years, were recruited for this study, including 12 designers and 30 parents. The participants were intentionally selected as adult observers representing parental users, as parents are the primary decision-makers in the purchase, evaluation, and safety assessment of children’s beds.

All individuals satisfied the following eligibility criteria: (1) Visual acuity: Uncorrected or corrected visual acuity of ≥1.0, with myopic participants allowed to wear glasses during testing; (2) Visual health: No astigmatism, color blindness, color vision deficiency, or notable inter-ocular visual acuity discrepancies; (3) General ocular and physical health: No ocular conditions (e.g., dry eye syndrome, glaucoma) or issues such as ptosis or periorbital edema; (4) Cognitive capability: No neurological disorders, cognitive impairments, or psychological conditions, ensuring participants could fully understand and complete the experimental tasks.

2.3. Definitions and Applications of Eye-Tracking Metrics

Eye-tracking experiments reveal visual attention distribution and cognitive processes by recording and analyzing users’ eye movement data [

18]. Key metrics used in this study, along with their definitions and applications, are summarized in

Table 1.

2.4. Stimulus Material Preparation

Experiment 1: 12 commonly used solid wood materials in furniture were selected through market research. High-definition images of each wood type (

Figure 1) were collected, ensuring visible texture and color clarity for use as visual stimuli. The materials were numbered left-to-right and top-to-bottom as follows: (1) Red Oak, (2) Maple, (3) Elm, (4) Ash, (5) White Oak, (6) Cherry, (7) Pine, (8) White Oak, (9) Tulipwood, (10) Black Walnut, (11) Beech, (12) Rubberwood. To elucidate participants’ visual attention pathways across different wood materials, the material images were divided into 12 AOIs.

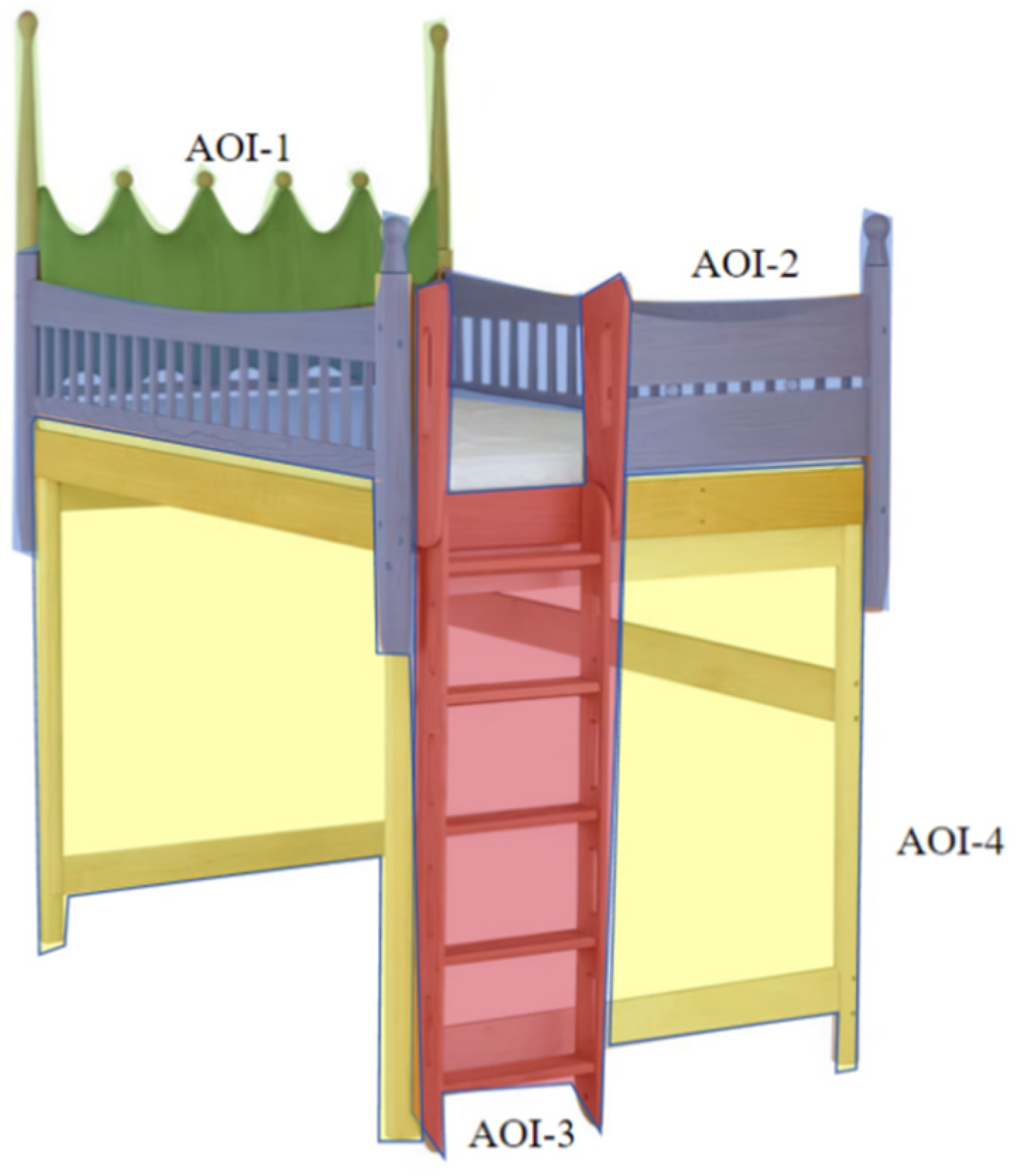

Experiments 2 and 3: Twenty children’s bed images were selected from e-commerce platforms based on sales performance, user reviews, and design diversity. The beds were categorized into five design types and standardized as simplified axonometric images to ensure structural clarity. For eye-tracking analysis, each bed was segmented into four functional AOIs: headboard, guardrail, ladder, and bed frame (including legs). An example AOI segmentation is shown in

Figure 2.

The correspondence between the three experiments and their respective visual stimuli is summarized in

Table 2.

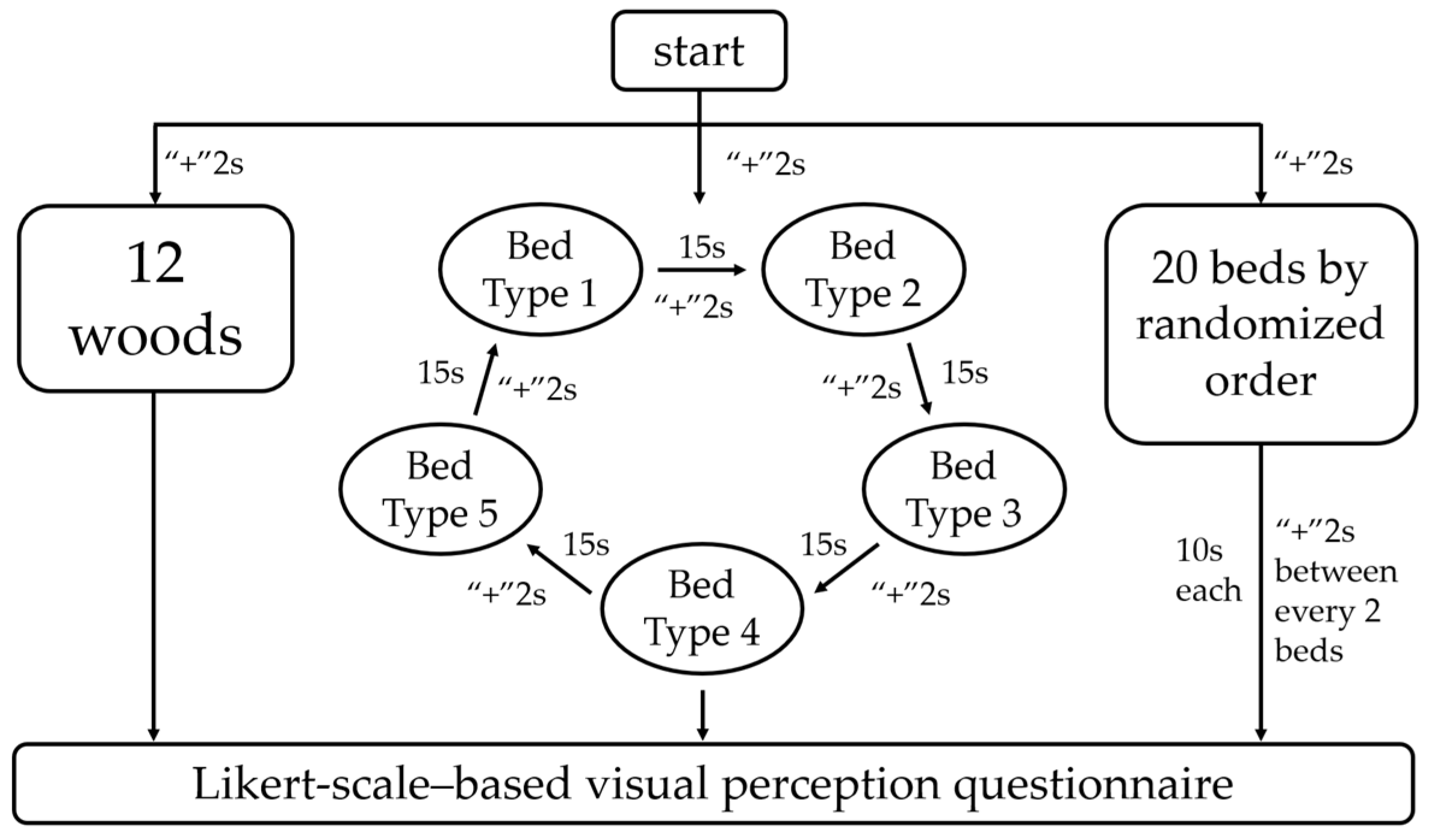

2.5. Experimental Procedure

The experiment comprised three sequential tasks examining users’ visual responses at the material, bed-type, and component levels. After informed consent and eye-tracking calibration, participants viewed all stimuli under standardized conditions (

Figure 3). All samples were presented on a single monitor as images of identical size and resolution, and the experimental conditions were kept consistent for all participants. The stimulus presentation durations were adjusted according to visual complexity and task demands: longer durations were used for multi-sample or comparative displays to allow sufficient scanning, while shorter durations were applied to single-object presentations to capture initial visual attention and key focal points efficiently.

Experiment 1: Resented 12 solid wood materials (4 × 3 matrix, 20 s) to assess how attentional allocation corresponded to subjective material preferences.

Experiment 2: Displayed five categories of children’s beds (4 samples per category, 15 s) to compare visual attractiveness across different design configurations.

Experiment 3: Showed 20 beds individually (10 s each, randomized order) and extracted time-to-first-fixation for four functional regions—guardrail, headboard, ladder, and bed frame—to identify priority visual focal points.

Across all tasks, a centrally displayed fixation cross (“+”) appeared for 2 s before each stimulus to reset gaze and eliminate carryover effects. After completing the viewing tasks, participants answered a Likert-scale visual perception questionnaire referencing a sample catalog to ensure accurate preference reporting and enhance data validity.

2.6. Data Analysis

Data were statistically analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics v25 and Microsoft Excel 365. The analysis included the following:

- (1)

Descriptive and preliminary analyses: including computation of means and standard deviations, and assumption testing through Levene’s test and Kolmogorov–Smirnov/Shapiro–Wilk tests to assess variance homogeneity and normality.

- (2)

Inferential statistics: where appropriate, parametric (one-way ANOVA, Welch ANOVA, Brown–Forsythe tests) or non-parametric methods (Kruskal–Wallis H test, Mann–Whitney U test) were applied to evaluate differences in eye-tracking metrics across materials, bed types, and AOIs.

- (3)

Post hoc and pairwise comparisons: using Games–Howell or Tukey HSD procedures to identify specific sources of significant differences following omnibus tests.

- (4)

Visual and correlation analyses: including gaze heatmaps, AOI fixation–sequence interpretation, and correlation analyses to link subjective evaluations with objective eye-tracking metrics and validate preference–attention consistency.

3. Results

3.1. Eye-Tracking Data Processing and Analysis for Solid Wood Material Preference

3.1.1. Gaze Transition Heatmap Analysis

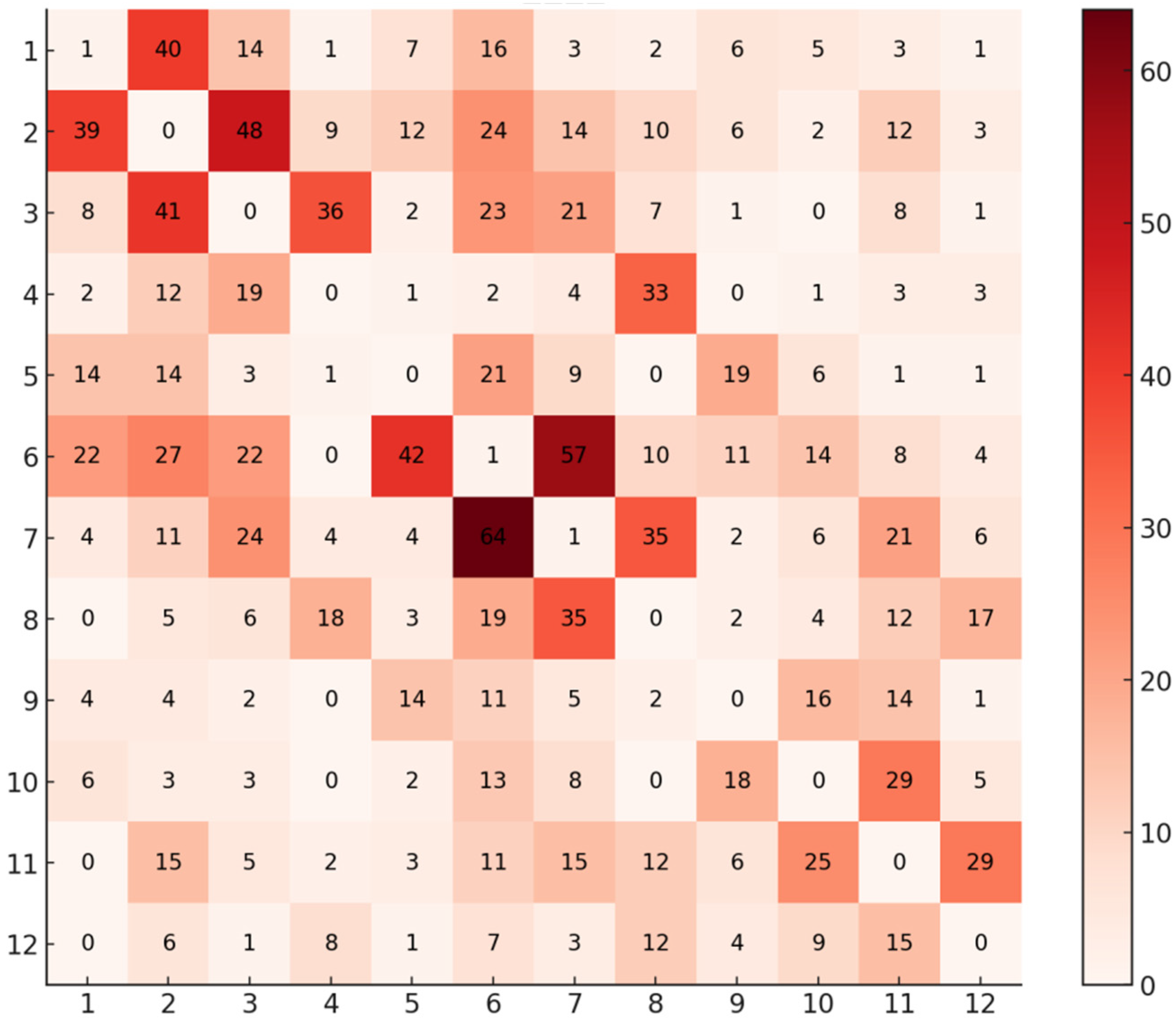

Gaze transition heatmaps for the 12 wood materials (

Figure 4) were generated based on fixation sequences, illustrating the saccadic transition frequencies between AOIs and thereby revealing users’ visual browsing patterns and material preference characteristics during exploration.

The gaze transition heatmap revealed that participants’ visual exploration followed a non-uniform and preferential transition mechanism driven by material salience. Materials such as Black Walnut, Maple, and Cherry showed consistently higher transition frequencies across AOIs, indicating stronger perceptual discriminability and greater involvement in comparative processing. The frequent bidirectional transitions between contrasting materials (e.g., Maple–Black Walnut) suggest that users employed contrast-based strategies to differentiate color, texture, and grain attributes. Moreover, AOIs with greater visual variability elicited more transitions, reflecting users’ reliance on active comparative judgment when evaluating material qualities under visually competitive conditions.

Key observations: (1) Color/Texture-Driven Comparisons: Transitions from lighter to darker materials (e.g., Maple to Black Walnut) suggest participants employed contrast-based viewing strategies, seeking differences in color, texture, or grain patterns. (2) Exploratory Visual Paths: Participants predominantly adopted exploratory gaze patterns rather than repetitive backtracking, shifting to new regions after initial information acquisition. (3) Salience of Material Variability: AOIs with greater differences in texture, color saturation, or surface finish attracted more transitions, becoming visual focal points. High transition frequencies may reflect participants’ need for comparative evaluations during material preference judgments, particularly when subjective distinctions were ambiguous.

3.1.2. Salience Analysis

A one-way ANOVA was conducted on time-to-first-fixation, total fixation duration, and fixation count across the 12 wood-material AOIs. Given significant variance heterogeneity (Levene’s test, all p < 0.001), Welch’s ANOVA and Brown–Forsythe robust tests were applied. The results (all p < 0.001), together with Games–Howell post hoc comparisons, demonstrated that visual attention differences among wood materials were systematic rather than random.

Across all three eye-tracking metrics, Maple, Cherry, and Pine consistently attracted earlier first fixations and longer viewing durations (p < 0.05) than low-salience materials such as Tulipwood, Rubberwood, and Ash. Importantly, these metrics did not operate independently; instead, they converged to form a stable attentional hierarchy, indicating coherent visual–cognitive processing rather than isolated effects. High-salience woods formed a tightly connected cluster with significant advantages over multiple materials, whereas low-salience woods showed minimal differentiation among themselves, suggesting weaker perceptual discriminability.

From a perceptual-cognitive perspective, several mechanisms underpin these visual attention patterns:

- (1)

Initial attention capture is shaped by material familiarity and intuitive recognition. Traditional and commonly used woods—such as Maple and Red Oak—are more readily detected under visually competitive conditions due to users’ prior exposure and culturally embedded expectations of quality.

- (2)

Sustained engagement is driven by texture richness, chromatic depth, and visual contrast. Materials with clearer grain patterns, layered coloration, and stronger surface definition provide higher perceptual information density, encouraging longer gaze durations, as observed with Maple and Cherry.

- (3)

Revisit behavior reflects users’ comparative evaluation strategies. When assessing material attributes, users tend to shift repeatedly between visually distinctive samples to compare grain clarity, color uniformity, or surface consistency. This leads materials with high perceptual discriminability—such as Cherry—to receive more frequent revisits, while low-contrast materials are more easily overlooked.

Overall, the integrated results highlight that users rely on a combination of perceptual distinctiveness, familiarity, and contrast-based evaluation when viewing wood materials. This produces a stable hierarchy of visual preferences that is consistently reflected across multiple eye-tracking indicators, offering a robust empirical basis for material selection in furniture and interior design.

3.1.3. Correlation Analysis of Subjective and Objective Preferences

To validate whether visual attention intensity reflects material preferences, subjectively preferred materials were compared with eye-tracking metrics using the Mann–Whitney U test (

Table 3).

Total Fixation Duration (

p = 0.000) and Fixation Count (

p = 0.001) were significantly higher for preferred materials than non-preferred ones, indicating that preferred materials elicited sustained and frequent visual engagement [

24]. Time-to-First-Fixation showed no significant difference (

p = 0.224), suggesting that preference formation relies on prolonged observation rather than initial attraction.

The Mann–Whitney U test results showed that total fixation duration (p = 0.000) and fixation count (p = 0.001) on preferred materials were significantly higher than on non-preferred ones, indicating that preferred materials elicited sustained and frequent visual engagement. In contrast, no significant difference was found in time-to-first-fixation (p = 0.224), suggesting that preference formation relies on prolonged observation rather than initial attraction. These results collectively validate the hypothesis that “longer fixation durations and higher fixation frequencies correlate with stronger preferences,” supporting the efficacy of eye-tracking metrics as predictors of subjective preferences.

The integration of subjective choices and fixation duration significance analysis reflects a latent association between visual attention and preference selection, implying that materials with longer fixation durations are more likely to be perceived as preferred [

25]. The mutual corroboration of subjective and objective data not only strengthens the persuasiveness of the findings but also provides theoretical support and empirical evidence for wood design and user experience optimization, further demonstrating the validity of eye-tracking metrics in predicting subjective material preferences.

3.2. Visual Preference Study of Different Bed Types

The 20 children’s beds were categorized into five groups based on design type: storage beds, mid-height beds, bunk beds, standard beds, and trundle beds. A preference study was conducted both within each group and across groups to analyze visual engagement patterns.

3.2.1. Integrated ANOVA Strategy for Multi-Type Bed Comparison

A one-way ANOVA was conducted for all five bed categories (storage beds, mid-height beds, trundle beds, bunk beds, and standard beds) to examine differences in time-to-first-fixation, total fixation duration, and fixation count. Levene’s tests consistently revealed violations of variance homogeneity for most visual metrics (all

p < 0.05), including time-to-first-fixation and total fixation duration across all bed types, as well as fixation count for storage, trundle, and bunk beds. Accordingly, Welch’s ANOVA and the Brown–Forsythe robust ANOVA were applied, followed by Games–Howell post hoc comparisons to ensure reliable multiple-comparison results. For metrics meeting the homogeneity assumption—specifically fixation count in mid-height beds (

p = 0.579) and standard beds (

p = 0.150)—standard one-way ANOVA was used instead (

Table 4), with Tukey HSD post hoc tests. This hybrid analytical approach ensured statistical rigor by matching the appropriate ANOVA model to each metric’s distributional characteristics.

3.2.2. Interpretation of ANOVA Results

- (1)

Time-to-First-Fixation

Across all five bed categories, one-way ANOVAs consistently revealed significant differences in time-to-first-fixation within each category (all

p < 0.001). However, the pattern of results points to a common mechanism rather than isolated sample effects. In most categories, at least one bed (often Bed 1 or Bed 2 within the group) showed markedly shorter time-to-first-fixation, indicating strong initial visual salience, whereas another bed in the same category (e.g., Storage Bed 3, Mid-Height Bed 3, Trundle Bed 4, Bunk Bed 2, Standard Bed 4) exhibited the longest latency (typically

p < 0.001), reflecting weak initial attraction [

26]. This recurrent contrast suggests that initial attention is highly sensitive to global form legibility and key-feature prominence: designs with clearer overall silhouettes, more easily recognizable safety structures, or visually well-organized layouts tend to capture attention rapidly, while visually ambiguous or less articulated designs are more likely to be overlooked in the early stages of scanning [

27].

- (2)

Total Fixation Duration

Total fixation duration also varied significantly within all bed categories (p < 0.01 or p < 0.001), but the resulting rankings differed from those of time-to-first-fixation. This divergence indicates a partial decoupling between initial attraction and sustained engagement. Designs that elicited the longest viewing times were not necessarily those noticed first, suggesting that sustained attention is more strongly influenced by information richness, structural articulation, and functional affordances—such as visible storage modules or complex safety-related components—rather than by salience alone. Thus, some beds may attract attention more slowly but maintain engagement once fixated due to higher perceptual and functional complexity.

- (3)

Fixation Count

Fixation count showed significant within-category differences in most bed types (p < 0.001), except for mid-height beds, where revisitation behavior was relatively balanced (p > 0.05). In the other bed categories, some samples exhibited higher fixation counts (e.g., Storage Bed 2 and Trundle Bed 4), whereas others consistently showed lower levels (e.g., Storage Bed 3 and Trundle Beds 1–2). Higher fixation counts were consistently associated with designs combining functional complexity and visible safety features, which encourage repeated scanning and comparative inspection across different regions. In contrast, visually simpler or less functionally expressive designs generated fewer gaze returns, resulting in lower fixation counts.

Taken together, these results indicate that, at the level of bed-type families, visual behavior follows a coherent mechanism: Initial attention is governed by global form and salient cues; Sustained attention reflects perceived functional and structural richness; Revisitation is driven by the cognitive need to inspect complex, safety- or function-critical areas in greater detail.

3.2.3. Multi-Type Beds Analysis Conclusion

Synthesizing the results across all five bed categories, a coherent three-stage pattern of visual behavior can be identified at the interior-environment scale: initial attraction, sustained attention, and exploratory revisitation. Beds that performed best in time-to-first-fixation (typically Bed 1 within each group) were characterized by clear global silhouettes and visually legible key elements, indicating that overall form articulation is critical for capturing early attention. By contrast, beds that dominated in total fixation duration and fixation count (often Bed 3 or models with more articulated functions) benefited from richer material expression, structural detailing, and visible functional components, which collectively support prolonged information processing and repeated visual inspection.

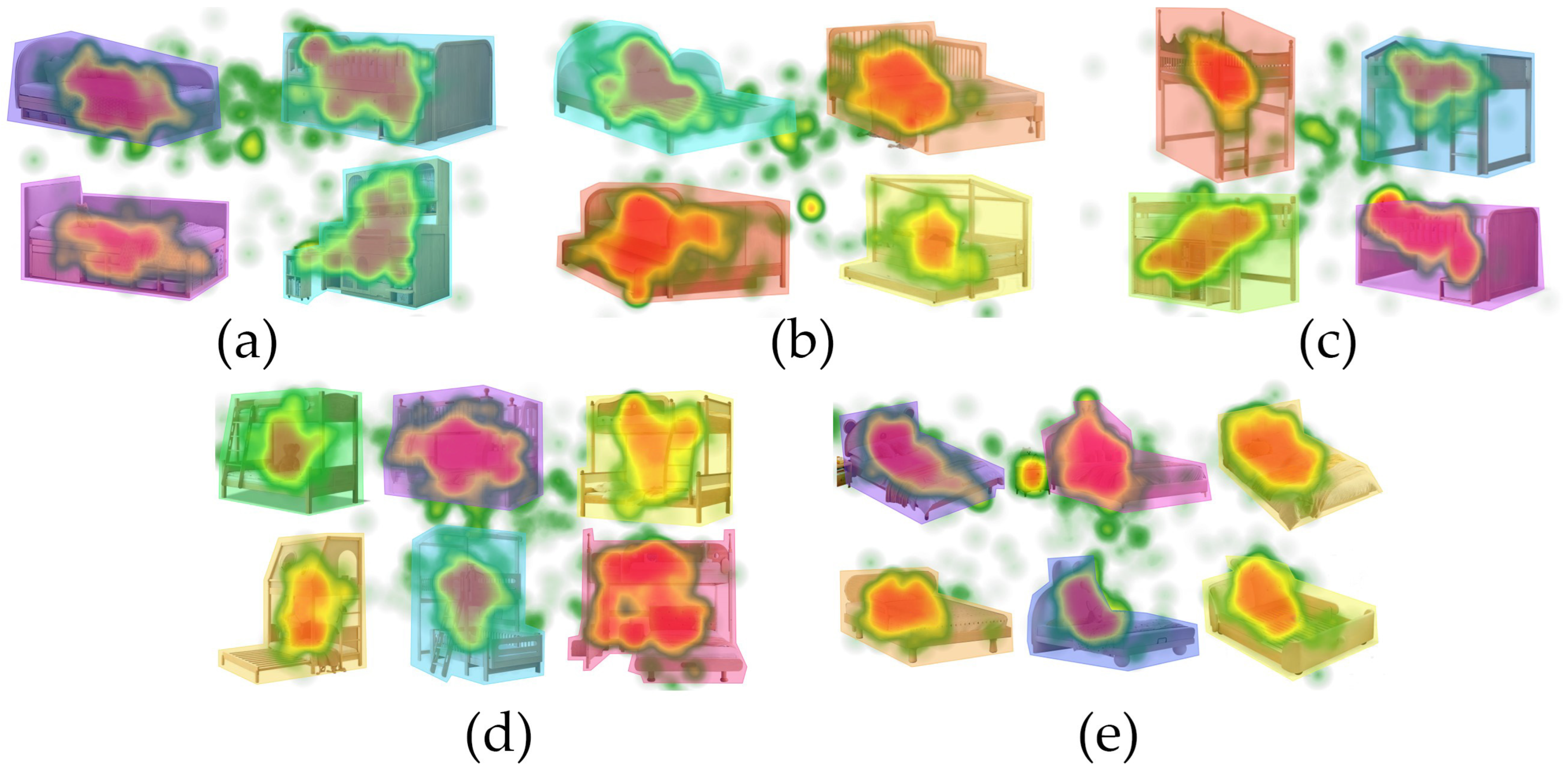

Heatmap analyses (

Figure 5) further showed that gaze clusters were consistently located on safety- and function-related components—such as guardrails, headboards, trundle rails, retractable mechanisms, ladders, and major structural joints—while lower frames and secondary support elements received comparatively limited attention. This distribution suggests that, in the context of children’s bedroom environments, users (especially caregivers) prioritize perceived safety, structural stability, and functional usability over purely formal or stylistic features. From an interior and furniture design perspective, these findings underscore the importance of visually emphasizing safety-critical and high-usage elements in children’s beds to align with users’ cognitive priorities and to enhance the perceived quality of the built environment.

3.3. Cross-Group Analysis: Comparative Visual Preference Analysis of Bed Types

According to the results of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests, the

p-values for time-to-first-fixation, total fixation duration, and fixation count of all bed types were less than 0.05, indicating that the data did not follow a normal distribution. Therefore, the Kruskal–Wallis H test (

Table 5) was employed to compare the significant differences in the three eye-tracking metrics across the five types of children’s beds.

Results from the Kruskal–Wallis H test revealed clear patterns across bed types in all three eye-tracking metrics. Time-to-first-fixation differed significantly among bed categories (

p = 0.025), with bunk beds and standard beds achieving the highest mean ranks and thus showing the strongest initial visual attraction, while mid-height beds ranked lowest, indicating reduced early salience. Total fixation duration did not differ significantly (

p = 0.575), suggesting that sustained visual engagement is influenced more by individual or contextual factors than by bed-type characteristics [

28]. In contrast, fixation count showed highly significant differences (

p = 0.000): storage beds exhibited the highest mean rank due to their structural and functional complexity, generating the most active exploratory gaze behavior; bunk beds, standard beds, and mid-height beds showed the fewest visual transitions, consistent with their simpler structures and fewer salient visual elements [

8]. Overall, bed type substantially shaped user visual attention mechanisms: bunk and standard beds excelled in initial attraction, while storage beds were most effective in sustaining exploratory engagement, offering useful implications for function-oriented children’s furniture design.

3.4. Single-Bed Visual Cognition Analysis

Time-to-first-fixation in the individual bed–level eye-tracking experiment, defined as the duration of the first gaze fixation on a specific region, is a core metric for assessing the initial visual salience of that region. Additionally, the sequence of first fixation locations reflects users’ overall visual scanning paths and attentional patterns, revealing their prioritization and cognitive preferences for different morphological features of the target object [

29]. A shorter time-to-first-fixation reflects a higher likelihood of drawing users’ attention. Therefore, the time-to-first-fixation for each AOI in the samples was extracted to determine the visual attention sequence during observation, thereby inferring users’ cognitive preference rankings for different bed regions. This method effectively identifies the morphological features that capture users’ attention first and supports subsequent design optimization and enhancement of key functional areas.

The time-to-first-fixation values for each AOI were averaged across all samples, and the corresponding visual attention priorities were ranked (

Table 6). The results show that participants fixated on the guardrail first, followed by the headboard, bed frame, and ladder. This pattern suggests that the guardrail—combining both safety functions and visual prominence—exhibited the strongest initial salience. Based on this finding, the guardrail and headboard were identified as the most representative visual attention regions and should be prioritized as key elements in the analysis of children’s bed design.

3.5. Questionnaire Data Processing and Analysis

Based on the eye-tracking results (visual priority: guardrail > headboard > bed frame > ladder), a questionnaire was administered to the same participants to collect subjective evaluations of the sample beds, enabling quantitative analysis of preferences related to overall form and functional configuration. In this study, user preference refers to parent-centered evaluative judgments of visual attractiveness, perceived safety, and functional suitability, rather than children’s own usage experiences.

A reliability test was conducted on the Likert-scale items in the questionnaire, yielding a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.822, indicating good internal consistency. According to general standards, an α value between 0.7 and 0.9 is considered acceptable, confirming the reliability of the survey data for further analysis.

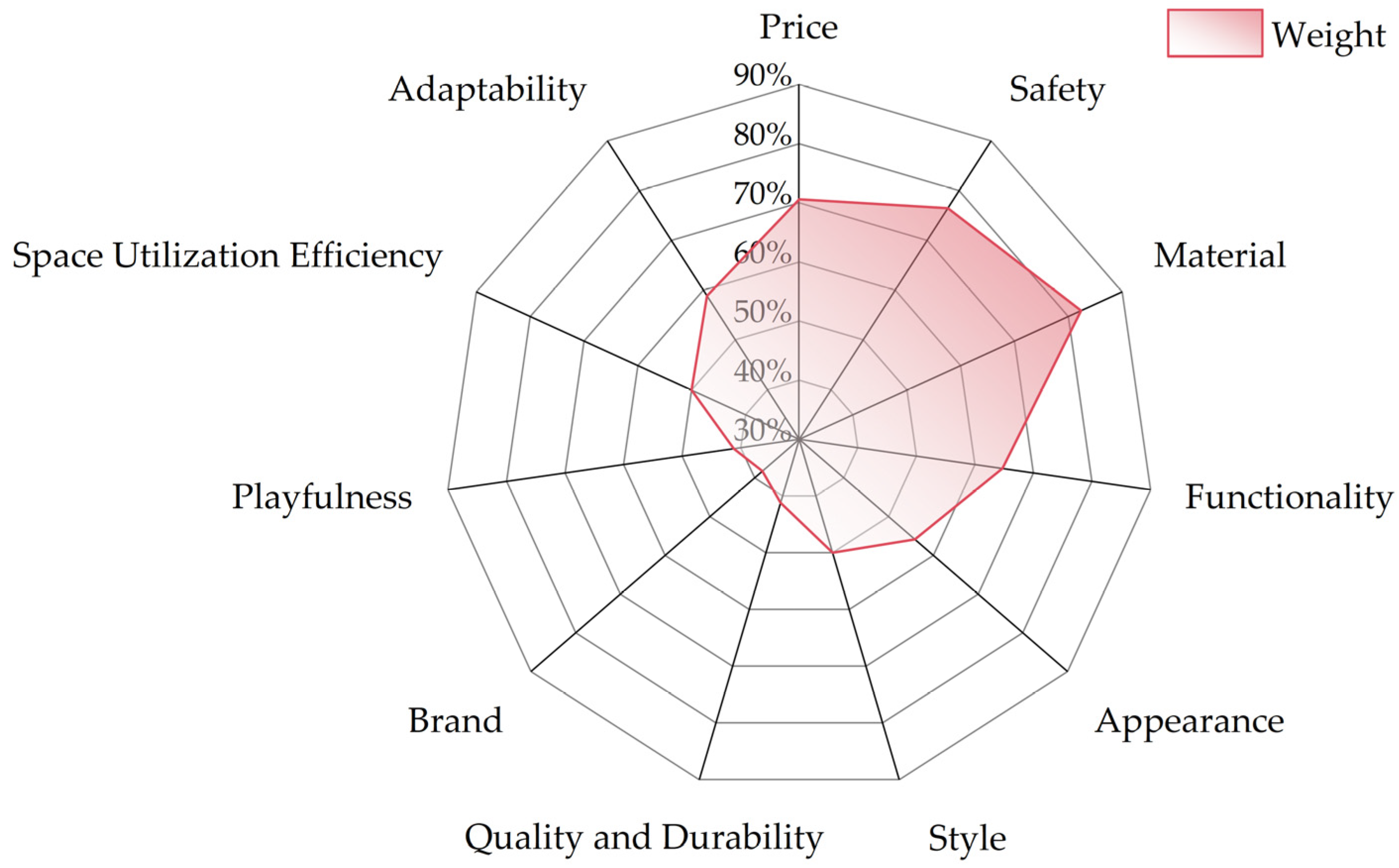

Analysis of the questionnaire results (

Figure 6) revealed the following priority structure for user concerns regarding children’s beds in interior environments: material (82.35%) > safety (76.47%) > price (70.59%). The strong emphasis on material quality reflects users’ attention to health, environmental performance, and sensory comfort. Safety ranked second, highlighting the importance of protective structural features in shaping the perceived safety of children’s rooms. Price remained a major consideration, while functionality (64.71%) and adaptability (58.82%) indicated users’ need for efficient storage and long-term spatial flexibility. Appearance (55.88%) and style (50%) were of lower concern, suggesting that aesthetic preferences are secondary to practical requirements. Brand (38.24%) and durability/lifespan (41.18%) showed the lowest priority, implying that users value experiential quality and cost-effectiveness more than brand reputation.

The survey results indicated a clear preference for solid wood (73.53%), attributed to its perceived eco-friendliness, safety, and durability. When combined with the eye-tracking findings—such as longer fixations on maple, cherry, and pine—these results further confirm the visual and functional advantages of solid wood materials. In terms of functional requirements, storage emerged as a primary need, with storage drawers (73.53%) and under-bed cabinets (55.88%) serving as key features, reflecting users’ strong demand for spatial efficiency. Overall, users valued not only basic functionality but also additional practical and expandable features. For design styles, simple modern aesthetics were most favored (47.06%), followed by playful, child-oriented styles (26.47%).

However, lower ratings for functionality (average score: 3.38) and safety (3.09) (especially for backrests and guardrails) suggest parents have higher expectations for protective and ergonomic features. This preference structure indicates that while aesthetics is valued, practical safety and functionality are prioritized in actual use.

4. Discussion

The observed differences in visual attention can be explained by a combination of perceptual salience and user-driven priorities. Notably, the bed’s guardrail consistently attracted the very first fixation, indicating the highest visual salience. This aligns with prior findings that, under free-viewing conditions, gaze initially lands on the most salient feature of an image—often areas with strong contrast or distinctive shape [

30]. The guardrail’s bold form (and possibly contrasting color) likely produced a “pop-out” effect, capturing bottom-up attention, as predicted by Feature Integration Theory and saliency-map models [

31]. In contrast, elements with lower perceptual salience (e.g., plain bed frames) received fewer early fixations unless guided by top-down factors.

Cognitive relevance further moderated these patterns. Beyond visual prominence, guardrails and headboards are closely associated with safety, a primary concern for parents. Viewers may therefore hold an implicit goal to inspect these components, reflecting top-down attention. Consistent with eye-tracking literature, initial fixations appear largely stimulus-driven, whereas later gaze allocation reflects user expectations and goals [

32]. In this study, bottom-up salience drove immediate attention to guardrails, while top-down safety relevance sustained focus on guardrails and headboards.

Differences among bed types and materials further support this interpretation. Storage beds elicited higher fixation counts, likely due to their greater structural and functional complexity, which encourages exploratory visual scanning [

33]. Bunk beds and standard beds exhibited shorter time-to-first-fixation than mid-height beds, possibly due to their larger scale or more familiar configurations. Regarding materials, beds made of maple, cherry, or black walnut attracted more fixations, indicating higher visual salience relative to the surrounding interior environment. Previous studies similarly report that wood with stronger color saturation or more pronounced grain contrast enhances visual engagement [

34].

Overall, these results corroborate and extend prior eye-tracking research in design contexts. For example, Göktaş et al. (2024) reported that eye-level elements and material variation attract greater attention in kitchen furniture displays [

8]. Similarly, in this study, guardrails and headboards emerged as natural focal points in children’s beds. Analogous to findings that salient décor can guide gaze through interior spaces [

35], the guardrail functioned as an inherent visual anchor, immediately attracting attention while conveying a sense of safety.

The generalizability of these findings should be interpreted with caution. This study focused on adult participants—primarily parents—viewing static images of children’s beds under controlled conditions. Visual attention patterns may differ in immersive real-world environments, during interactive use, or when evaluated directly by children. Nevertheless, the consistency of the present results with established visual attention theories and prior eye-tracking research in furniture and interior design suggests that the identified mechanisms are applicable to comparable residential furniture evaluation contexts.

From a practical design perspective, several implications emerge. Safety-critical components, particularly guardrails, should be treated as primary visual anchors and emphasized through clear form articulation and calibrated contrast. Visual complexity should be carefully managed, with functional features such as storage organized in a legible and structured manner to support intuitive visual exploration. Additionally, the use of natural wood materials with warm tones and distinct grain patterns can enhance both visual engagement and overall aesthetic coherence. By aligning bottom-up saliency cues with top-down parental priorities for safety and usability, designers can create children’s beds that are visually coherent, reassuring, and functionally supportive.

5. Conclusions

This study develops a multi-level visual attention framework for children’s beds in interior environments by integrating eye-tracking indicators with subjective preference evaluations. Rather than inferring internal cognitive mechanisms directly, the framework provides a behavioral interpretation of how visual stimuli are prioritized, how attention is allocated across components, and how these processes relate to preference formation in safety-sensitive furniture contexts. The results demonstrate that natural solid wood materials and safety-critical components, particularly guardrails and headboards, consistently receive higher visual priority, while storage-integrated beds encourage more exploratory viewing patterns. The primary contribution of this study lies in translating established visual attention principles into a transferable, design-oriented framework that operates at the component level. By linking perceptual saliency and user expectations to concrete design attributes, the proposed framework offers a structured approach for interpreting visual behavior and informing design decision-making in children’s furniture. The findings support design strategies that emphasize clear articulation of safety-related components and the use of visually legible, warm-toned materials to enhance both reassurance and aesthetic coherence. Several limitations should be acknowledged. The relatively small sample size and the use of two-dimensional visual stimuli may limit ecological validity, and the results should therefore be interpreted as guidance on visual priority rather than direct predictions of real-world use behavior. Future research should employ immersive or real-use environments and incorporate children’s visual responses to further test and refine the proposed framework, enhancing its applicability to broader design contexts.