Children’s Well-Being of Physical Activity Space Design in Primary School Campus from the Perspective of Basic Psychological Needs

Abstract

1. Introduction

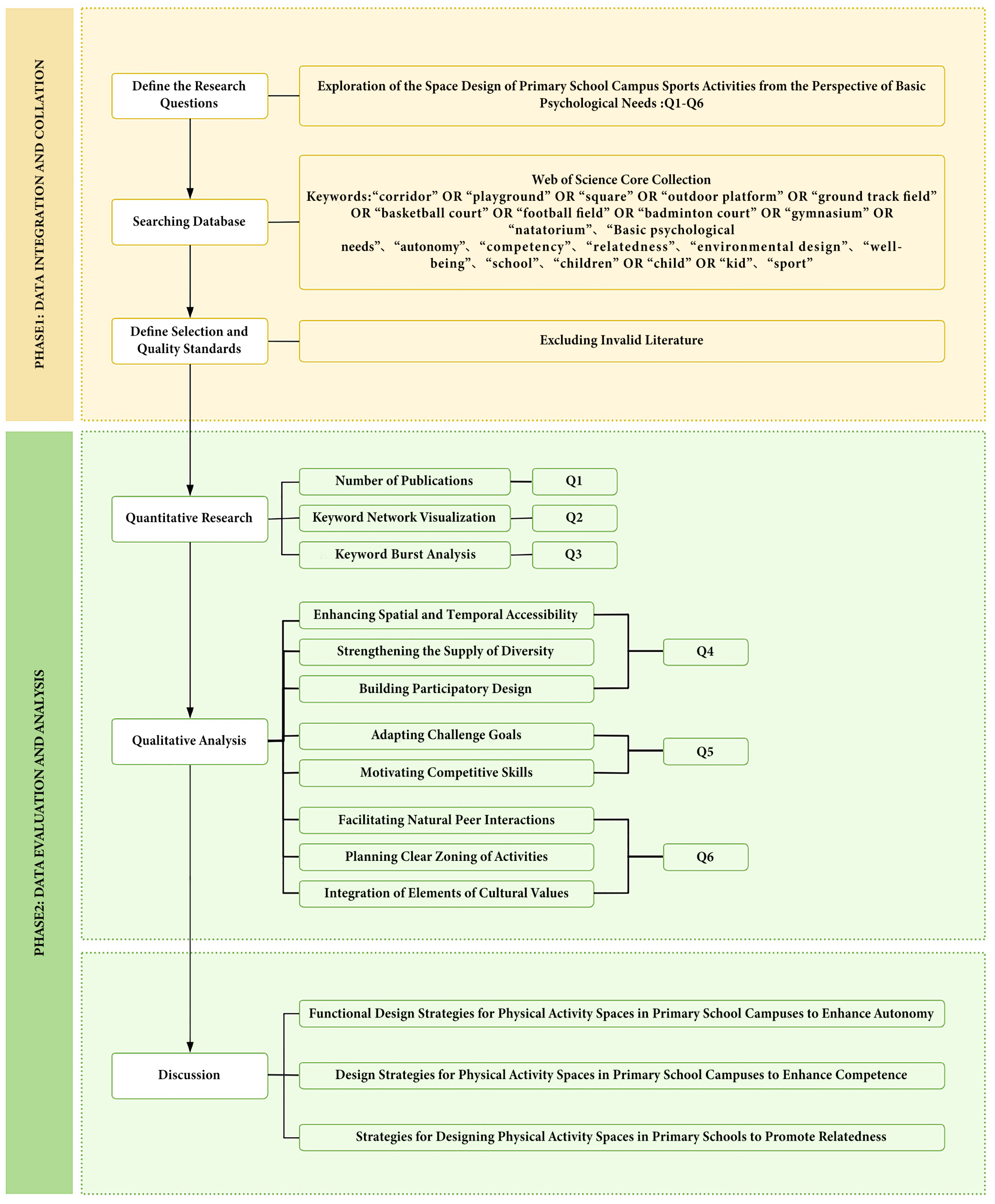

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Framework and Approach

2.2. Defining the Research Question

2.3. Searching the Database

2.4. Data Screening

- (1)

- Remove duplicate literature: Eliminate duplicate records to ensure data uniqueness.

- (2)

- Relevance to the theme: Exclude literature unrelated to research on physical activity spaces (e.g., exclude studies focusing solely on curriculum teaching).

- (3)

- Language: Exclude non-English text.

- (4)

- Document type: Peer-reviewed journal articles and conference papers.

- (5)

- Publication period: Literature published between 1985 (the year basic psychological needs were first proposed) and the first quarter of 2025 (the search date). As 2025 had not yet concluded at the time of retrieval, the 2025 cohort comprises only literature published and indexed in databases during the first quarter of that year (1 January to 31 March).

- (6)

- Design relevance: Exclude studies that do not explicitly mention design influences or spatial factors.

- (7)

- Academic influence: Priority shall be given to articles that have been widely cited within the field.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Research

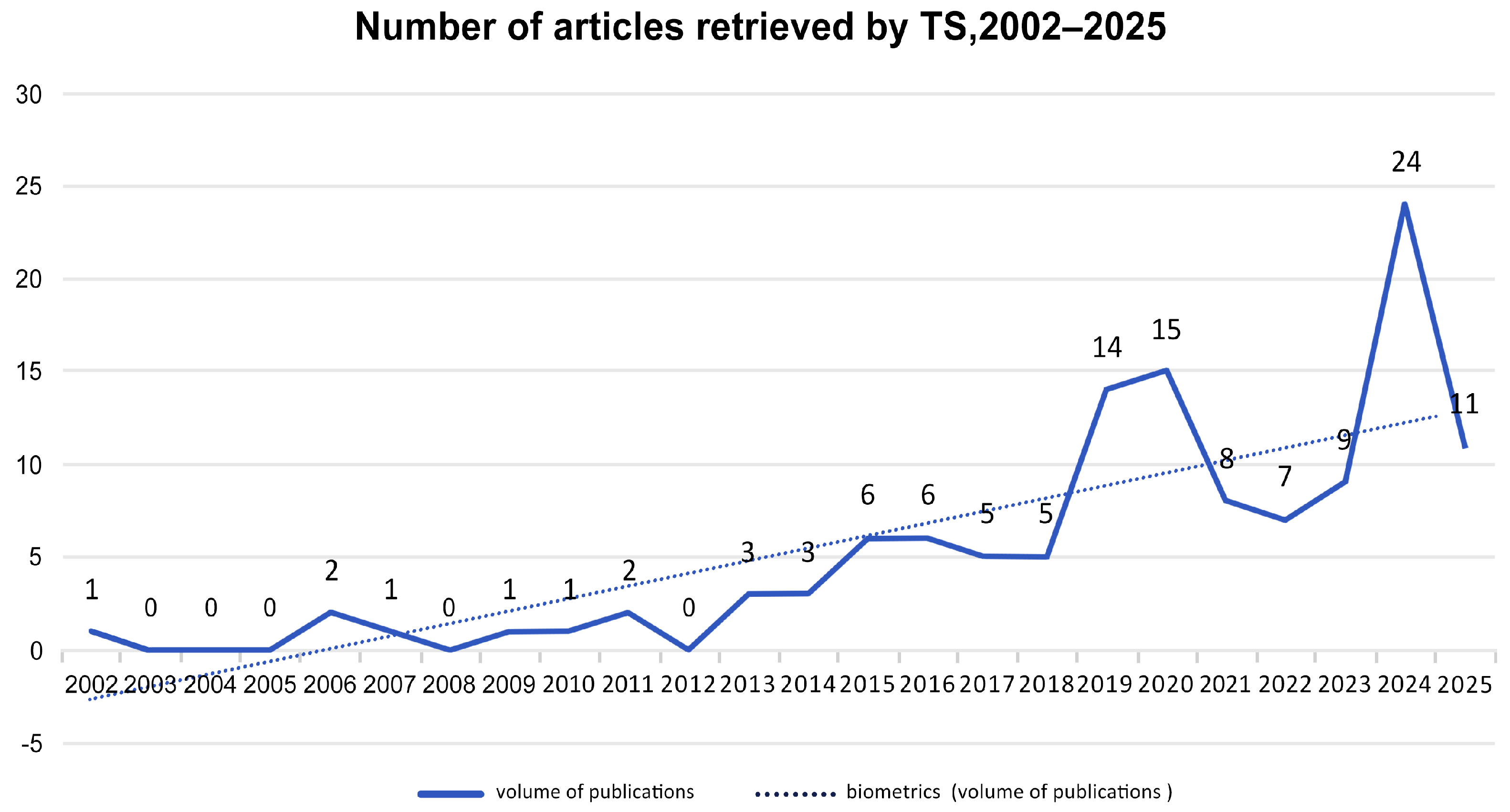

3.1.1. Number of Publications

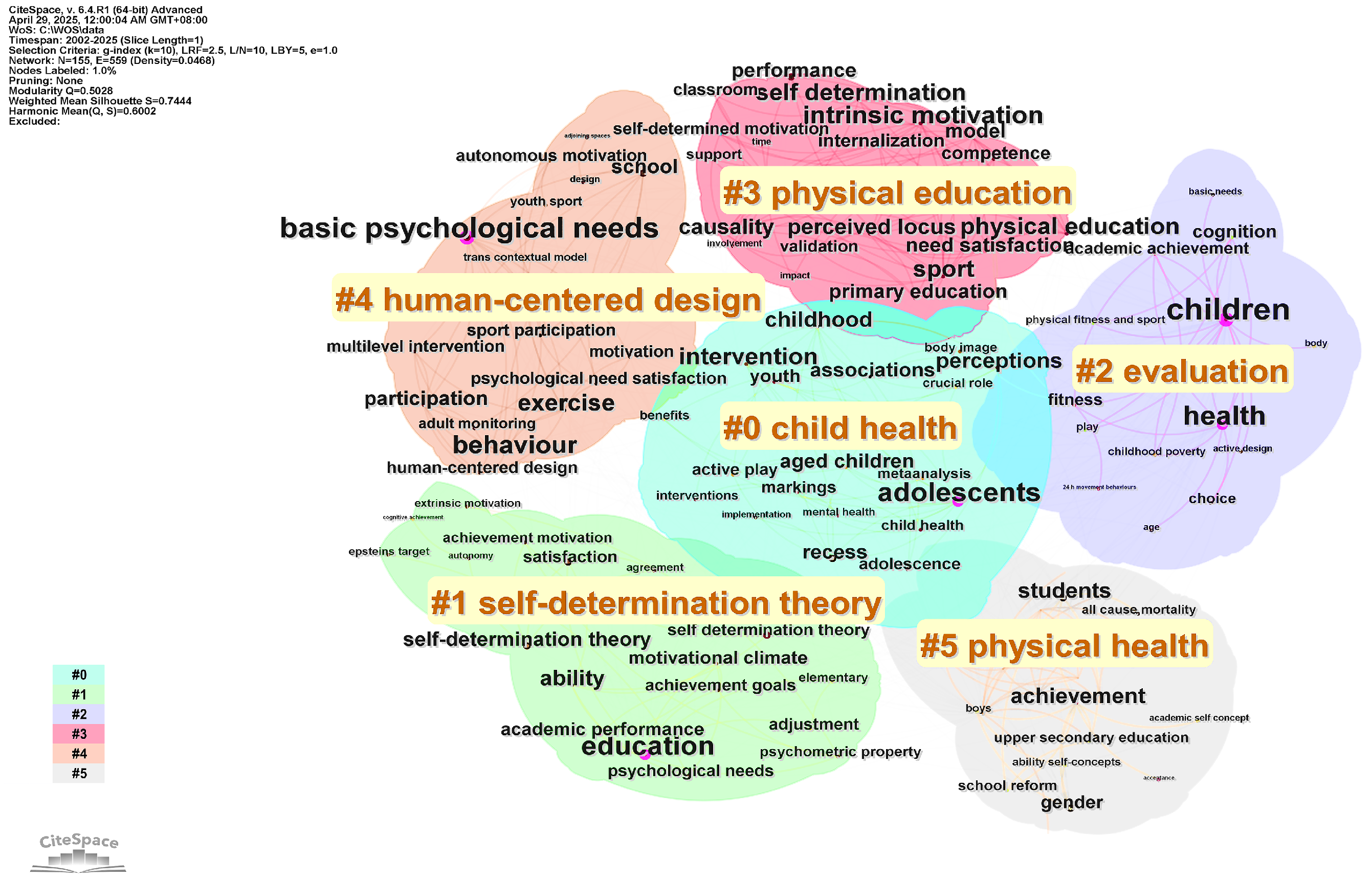

3.1.2. Keyword Network Visualisation

- (1)

- Health promotion and behavioural development objectives

- (2)

- Theory and design guidance

- (3)

- Evaluation

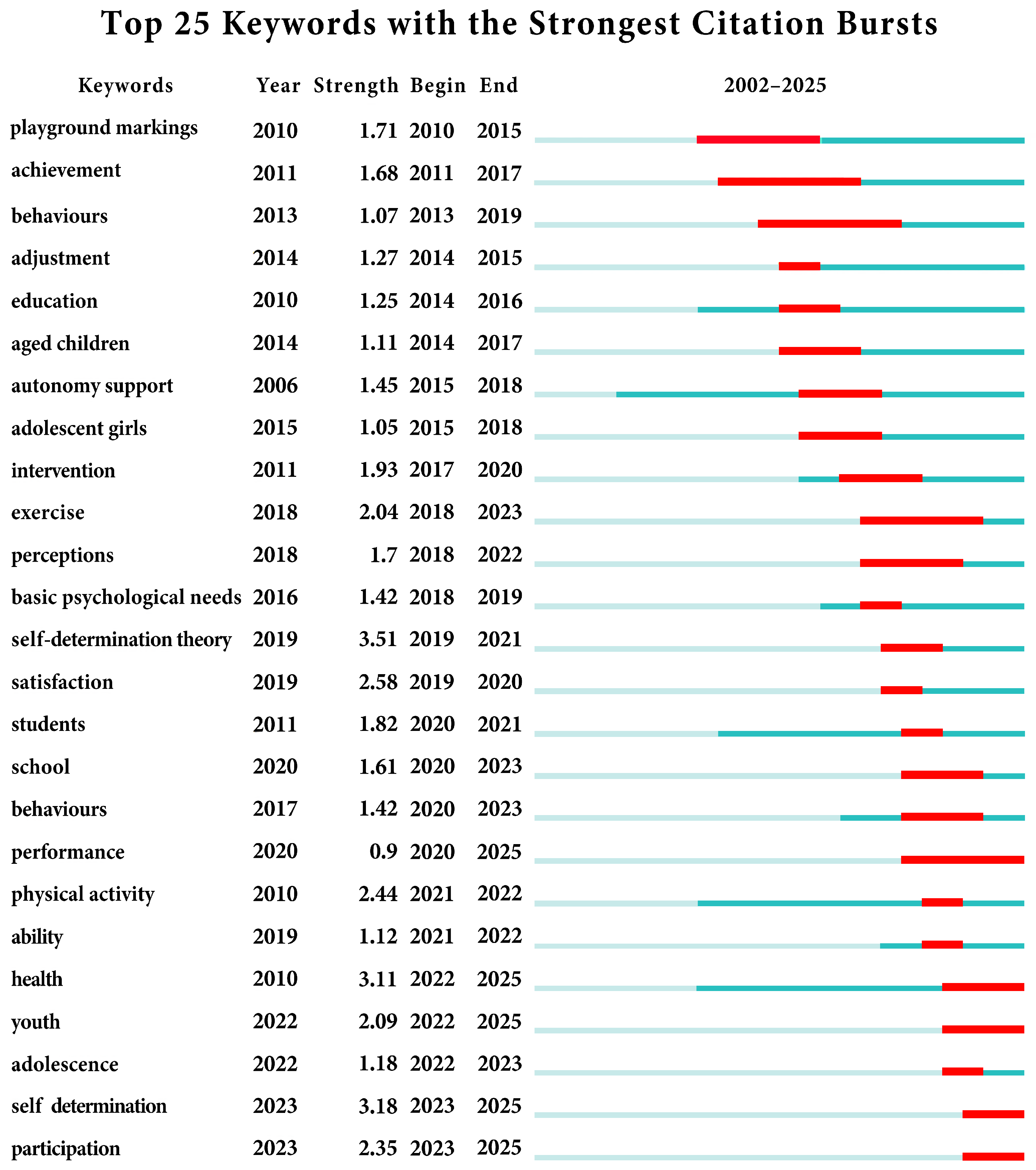

3.1.3. Keyword Burst Analysis

3.2. Qualitative Analysis: Impact on Children’s Well-Being Based on Basic Psychological Needs

3.2.1. Qualitative Content Analysis Procedure

3.2.2. Quantitative Analysis of Qualitative Coding

3.2.3. Q4: The Relationship Between Autonomy and the Design of Physical Activity Spaces in Primary School Campuses

- Enhancing spatial and temporal accessibility

- Strengthening the supply of diversity

- Building participatory design

3.2.4. Q5: The Relationship Between Competence and the Design of Physical Activity Spaces in Primary School Campuses

- Adapting challenge goals

- Motivating competitive skills

3.2.5. Q6: The Relationship Between Relatedness and the Design of Physical Activity Spaces in Primary School Campuses

- Facilitating natural peer interactions

- Planning clear zoning of activities

- Integration of elements of cultural values

4. Discussion

4.1. Functional Design Strategies for Physical Activity Spaces in Primary School Campuses to Enhance Autonomy

4.1.1. Functional Integration to Enhance Spatial and Temporal Accessibility

4.1.2. Synergistic Design of Diverse Facilities and Behaviours

4.1.3. Pathways to Practice Participatory Design for Children

4.2. Design Strategies for Physical Activity Spaces in Primary School Campuses to Enhance Competence

4.2.1. Dynamic Adaptation of Age and Ability Stratification

4.2.2. Sensory and Feedback Design for Competitive Environments

4.3. Strategies for Designing Physical Activity Spaces in Primary Schools to Promote Relatedness

4.3.1. Creation of Natural Interactive Scenes

4.3.2. Colour and Signage System for Functional Zones

4.3.3. Translation and Construction of Cultural Symbols

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Polanczyk, G.V.; Salum, G.A.; Sugaya, L.S.; Caye, A.; Rohde, L.A. Annual research review: A meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2015, 56, 345–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Luo, Y.; Li, H. Can sports cartoon watching in childhood promote adult physical activity and mental health? A pathway analysis in Chinese adults. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Mei, Y.; Huang, L.; Liu, X.; Xi, Y. Association of habitual physical activity with depression and anxiety: A multicentre cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e076095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Xiao, H.; Fan, X.; Zeng, W. Exploring the effects of physical exercise on inferiority feeling in children and adolescents with disabilities: A test of chain mediated effects of self-depletion and self-efficacy. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1212371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, J. Effect of Sports Participation on Social Development in Children Ages 6–14. Child Health Interdiscip. Lit. Discov. J. 2023, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Meng, X.; Qi, S.; Fan, J.; Yu, W.; Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y. The impact of school activity space layout on children’s physical activity levels during recess: An agent-based model computational approach. Build. Environ. 2025, 271, 112585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, S.; Brennan, D.; Hanna, D.; Younger, Z.; Hassan, J.; Breslin, G. The effect of a school-based intervention on physical activity and well-being: A non-randomised controlled trial with children of low socio-economic status. Sport.-Med.-Open 2018, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, K.; Lee, C.; Ndubisi, F. Universal design in playground environments: A place-based evaluation of amenities, use, and physical activity. Landsc. J. 2023, 42, 55–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Cho, T. A Study on the Preferences Structure of Speed Play Facilities in the Play Space of Developing Children-Focusing on Slides and Swings-. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2024, 20, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, J.; Roh, S.Y.; Kwon, D. Correlation Between Physical Activity and Learning Concentration, Self-Management, and Interpersonal Skills Among Korean Adolescents. Children 2024, 11, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westerskov Dalgas, B.; Elmose-Østerlund, K.; Bredahl, T.V.G. Exploring basic psychological needs within and across domains of physical activity. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health -Well-Being 2024, 19, 2308994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, M.; Wright, M.; Azevedo, L.B.; Macpherson, T.; Jones, D.; Innerd, A. The school playground environment as a driver of primary school children’s physical activity behaviour: A direct observation case study. J. Sport. Sci. 2021, 39, 2266–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Calvo, G.; Gerdin, G.; García-Monge, A. Soccer: The only way to be a boy in Spain? narratives from a Spanish primary school on the influence of playground soccer in shaping masculinities and gender relations. Sport. Educ. Soc. 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjønniksen, L.; Wiium, N.; Fjørtoft, I. Affordances of school ground environments for physical activity: A case study on 10- and 12-year-old children in a Norwegian primary school. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 773323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamer, M.; Aggio, D.; Knock, G.; Kipps, C.; Shankar, A.; Smith, L. Effect of major school playground reconstruction on physical activity and sedentary behaviour: Camden active spaces. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brittin, J.; Sorensen, D.; Trowbridge, M.; Lee, K.K.; Breithecker, D.; Frerichs, L.; Huang, T. Physical activity design guidelines for school architecture. PloS ONE 2015, 10, e0132597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Toussaint, H.M.; Van Willem, M.; Verhagen, E. PLAYgrounds: Effect of a PE playground program in primary schools on PA levels during recess in 6 to 12 year old children. Design of a prospective controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, J.; Bretz, K.; Herrmann, C.; Schuler, P.; Ferrari, I. Profiles of Primary School Children’s Sports Participation and Their Motor Competencies. Children 2024, 11, 1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnas, J.L.; Emerson, T.; Ball, S.D. Effects of Activity-zoned Playgrounds on Social Skills, Problem Behavior, and Academic Achievement in Elementary-aged Children. Health Behav. Policy Rev. 2024, 11, 1587–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, K.; Ni, E.; Deng, Q. Optimizing classroom modularity and combinations to enhance daylighting performance and outdoor platform through ANN acceleration in the post-epidemic era. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanza, K.; Alcazar, M.; Hoelscher, D.M.; Kohl, H.W., 3rd. Effects of trees, gardens, and nature trails on heat index and child health: Design and methods of the Green Schoolyards Project. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pate, R.R.; Davis, M.G.; Robinson, T.N.; Stone, E.J.; McKenzie, T.L.; Young, J.C. Promoting physical activity in children and youth: A leadership role for schools: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism (Physical Activity Committee) in collaboration with the Councils on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young and Cardiovascular Nursing. Circulation 2006, 114, 1214–1224. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Standage, M.; Duda, J.L.; Ntoumanis, N. Students’ motivational processes and their relationship to teacher ratings in school physical education: A self-determination theory approach. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2006, 77, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haapala, H.L.; Hirvensalo, M.H.; Laine, K.; Laakso, L.; Hakonen, H.; Kankaanpää, A.; Lintunen, T.; Tammelin, T.H. Recess physical activity and school-related social factors in Finnish primary and lower secondary schools: Cross-sectional associations. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strode, A.; Kaupužs, A. Opportunities for active design in school environment for promotion of pupils’physical activity. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies, Palma, Spain, 1–3 July 2019; pp. 5474–5482. [Google Scholar]

- Toft Amholt, T.; Westerskov Dalgas, B.; Veitch, J.; Ntoumanis, N.; Jespersen, J.F.; Schipperijn, J.; Pawlowski, C. Motivating playgrounds: Understanding how school playgrounds support autonomy, competence, and relatedness of tweens. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health -Well-Being 2022, 17, 2096085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, E.; Ayllon, E.; Eito, M.; Lozano, A.; Martínez, S.; Bañares, L.; Vicén, M.J.; Moreno, P. La Ciudad de las Niñas y los Niños de Huesca, una oportunidad en el diseño de entornos y políticas públicas saludables. Gac. Sanit. 2019, 33, 296–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greeven, S.J.; Fernández Solá, P.A.; Kercher, V.M.; Coble, C.J.; Pope, K.J.; Erinosho, T.O.; Grube, A.; Evanovich, J.M.; Werner, N.E.; Kercher, K.A. Hoosier Sport: A research protocol for a multilevel physical activity-based intervention in rural Indiana. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1243560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggan, M. Instilling positive attitudes to physical activity in childhood–challenges and opportunities for non-specialist PE teachers. Education 3-13 2022, 50, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichengreen, A.; Tsou, Y.T.; Nasri, M.; Klaveren, L.M.; Li, B.; Koutamanis, A.; Baratchi, M.; Blijd-Hoogewys, E.; Kok, J.; Rieffe, C. Social connectedness at the playground before and after COVID-19 school closure. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2023, 87, 101562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Giménez, A.; García-Rodríguez, I. Motivational predictors of schoolchildren’s moods in a recess intervention. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2024, 44, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerset, S.; Hoare, D.J. Barriers to voluntary participation in sport for children: A systematic review. BMC Pediatr. 2018, 18, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lousen, I.; Arvidsen, J.; Pawlowski, C.S. Children’s play behaviour and engagement with the schoolyard environment. Int. J. Play. 2024, 13, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasirci, D.; Wilson, S.G.; Pasin, B. Participatory Approaches in Design Education. In Proceedings of the 10th Annual International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation, Seville, Spain, 16–18 November, 2017; pp. 6987–6997. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwardson, C.L.; Harrington, D.M.; Yates, T.; Bodicoat, D.H.; Khunti, K.; Gorely, T.; Sherar, L.B.; Edwards, R.T.; Wright, C.; Harrington, K.; et al. A cluster randomised controlled trial to investigate the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of the ‘Girls Active’ intervention: A study protocol. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomé, G.; Guedes, F.B.; Cerqueira, A.; Noronha, C.; Freitas, J.; Freire, T.; Matos, M. How is leisure related to well-being and to substance use? The probable key role of autonomy and supervision. Children 2023, 10, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Patón, R.; Rodríguez-Negro, J.; Muíño-Piñeiro, M.; Mecías-Calvo, M. Gender and educational stage differences in motivation, basic psychological needs and enjoyment: Evidence from physical education classes. Children 2024, 11, 1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R.P.; Payne, R.; Raya Demidoff, A.; Samsudin, N.; Scheuer, C. Active recess: School break time as a setting for physical activity promotion in European primary schools. Health Educ. J. 2024, 83, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaraz-Muñoz, V.; Cifo Izquierdo, M.I.; Gea García, G.M.; Alonso Roque, J.I.; Yuste Lucas, J.L. Joy in movement: Traditional sporting games and emotional experience in elementary physical education. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 588640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lateef, S.; Zahir, R.; Sherdil, L.; McCleary, C.; Shafin, T. The power of play: Examining the impact of a school yard playground on attitudes toward school and peer relationships among elementary school students in Chennai, India. Glob. Pediatr. Health 2024, 11, 2333794X241247979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulos, A.; Wilson, K.; Lanza, K.; Vanos, J. A direct observation tool to measure interactions between shade, nature, and children’s physical activity: SOPLAY-SN. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2022, 19, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touloumakos, A.K.; Barrable, A. Adverse childhood experiences: The protective and therapeutic potential of nature. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 597935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, A.L.; Brown, C.D.; Reuben, A.; Nicholls, N.; Pfeiffer, K.A.; Clevenger, K.A. Elementary classroom views of nature are associated with lower child externalizing behavior problems. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulin, F.; McGovern-Murphy, F.; Chan, A.; Capuano, F. Participation in organized leisure activities as a context for the development of social competence among preschool children. J. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 2, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Chiu, C.; Tam, K.P.; Lee, S.; Lau, I.Y.; Peng, S. Perceived cultural importance and actual self-importance of values in cultural identification. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sando, O.J.; Mehus, I. Supportive indoor environments for functional play in ECEC institutions: A strategy for promoting well-being and physical activity? Early Child Dev. Care 2021, 191, 921–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montandon, K.A. Equipment Availability in the Home and School Environment: Its Relationship on Physical Activity in Children. Ph.D. Thesis, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, C.A.; Clark, A.F.; Gilliland, J.A. Built environment influences of children’s physical activity: Examining differences by neighbourhood size and sex. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, P.; Newman, S.; Swiniarski, L. On ‘becoming social’: The importance of collaborative free play in childhood. Int. J. Play. 2014, 3, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaei, L.; Shahbazi, M. Investigating Effective Factors on Designing of Educational Spaces with an Approach to Increase Learning Rate and to Improve Creativity among Children. Khazar J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2016, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjortoft, I. The natural environment as a playground for children: The impact of outdoor play activities in pre-primary school children. Early Child. Educ. J. 2001, 29, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber Taylor, A.; Kuo, F.E. Children with attention deficits concentrate better after walk in the park. J. Atten. Disord. 2009, 12, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez Pérez, B.M.; Ruedas Caletrio, J.; Caballero Franco, D.; Murciano-Hueso, A. La conexión con la naturaleza como factor clave en la formación de las identidades infantiles: Una revisión sistemática. TeoríA Educ. 2024, 36, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagdamen, N.J.B.; Castro, A.L.S. Enhancing Social Skills in Children with Autism Through Structured Interactions. Int. J. Res. Publ. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednar, J.; Bramson, A.; Jones-Rooy, A.; Page, S.E. Conformity, Consistency, and Cultural Heterogeneity. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Marriott, Loews Philadelphia, and the Pennsyivania Convention, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 20 November 2006; 2006. [Google Scholar]

| General Question | Sub-Questions | Research Methods |

|---|---|---|

| From the perspective of exploring basic psychological needs, how can the physical activity space in primary school campus be designed to improve children’s happiness? | Q1: Research status | Quantitative research |

| Q2: Research hotspots | ||

| Q3: Research trends | ||

| Q4: The relationship between autonomy and the design of physical activity spaces in primary school campuses | Qualitative analysis | |

| Q5: The relationship between competence and the design of physical activity spaces in primary school campuses | ||

| Q6: The relationship between relatedness and the design of physical activity spaces in primary school campuses |

| Search Dimensions | Keyword | Adjusted Keywords | Reasons For Adjustment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Theory | “Basic psychological needs,” “autonomy,” “competence,” “relatedness” | Remain unchanged | This study adopts the theory of basic psychological needs as its core analytical perspective. |

| Event venue | “corridor,” “playground,” “square,” “outdoor platforms,” “ground track field,” “basketball court,” “football field,” “badminton court,” “gymnasium,” “natatorium” | Remain unchanged | An operational definition of “primary school physical education activity spaces”. Drawing upon comprehensive studies, this has been specified into a series of distinct spatial typologies using English keywords to ensure exhaustive retrieval. |

| Core premises | “primary school,” “elementary school” | “school” | Reason for adjustment: The initial retrieval results were insufficient (only 123 articles), rendering analysis impracticable. Theoretical Basis: Physical activity spaces in primary schools and broader educational institutions share significant commonalities in functional attributes and usage logic. Adjustment effect: The number of retrieved results increased to 579, yielding richer data and a more comprehensive perspective while maintaining relevance to the core research focus. |

| Keywords | Number of Documents Searched |

|---|---|

| (TS = (“Basic psychological needs”) AND TS = (“children” OR “child” OR “kid”) AND TS = (sport)) | 61 |

| (TS = (“corridor” OR “playground” OR “square” OR “outdoor platform” OR “ground track field” OR “basketball court” OR “football field” OR “badminton court” OR “gymnasium” OR “natatorium”) AND TS = (“Basic psychological needs”) AND TS = (school)) | 9 |

| (TS = (“corridor” OR “playground” OR “square” OR “outdoor platform” OR “ground track field” OR “basketball court” OR “football field” OR “badminton court” OR “gymnasium” OR “natatorium”) AND TS = (autonomy) AND TS = (school)) | 87 |

| (TS = (“corridor” OR “playground” OR “square” OR “outdoor platform” OR “ground track field” OR “basketball court” OR “football field” OR “badminton court” OR “gymnasium” OR “natatorium”) AND TS = (competency) AND TS = (school)) | 124 |

| (TS = (“corridor” OR “playground” OR “square” OR “outdoor platform” OR “ground track field” OR “basketball court” OR “football field” OR “badminton court” OR “gymnasium” OR “natatorium”) AND TS = (relatedness) AND TS = (school)) | 12 |

| (TS = (“corridor” OR “playground” OR “square” OR “outdoor platform” OR “ground track field” OR “basketball court” OR “football field” OR “badminton court” OR “gymnasium” OR “natatorium”) AND TS = (“environmental design”) AND TS = (school)) | 7 |

| (TS = (“corridor” OR “playground” OR “square” OR “outdoor platform” OR “ground track field” OR “basketball court” OR “football field” OR “badminton court” OR “gymnasium” OR “natatorium”) AND TS = (“well-being”) AND TS = (school)) | 279 |

| Core Theme | Code | Operational Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Autonomy | A1—Enhancing spatial and temporal accessibility | The spatial layout described in the literature reduces physical or time barriers to accessing activity areas. |

| A2—Strengthening the supply of diversity | The literature describes a variety of facilities, equipment, and activity scenarios designed to support free selection and exploration based on individual interests, abilities, and moods. | |

| A3—Building participatory design | The literature indicates that the design process incorporates children’s participation, opinions, or ideas. | |

| Competence | C1—Adapting challenge goals | The difficulty level of facilities or activities described in the literature is matched to the abilities of children of different ages, genders, and skill levels. |

| C2—Motivating competitive skills | The literature describes the establishment of multiple difficulty levels within the same space or facility system. | |

| Relatedness | R1—Facilitating natural peer interactions | The literature describes how spatial design naturally elicits or facilitates behaviours such as social interaction, conversation, and cooperative play among children. |

| R2—Planning clear zoning of activities | The literature describes the use of physical boundaries, ground markings, and other means to clearly demarcate functional zones within activity spaces. | |

| R3—Integration of elements of cultural values | The literature mentions incorporating elements into spatial design that evoke cultural identity and collective memory. |

| Core Theme | Code | Frequency of Occurrence |

|---|---|---|

| Autonomy | A1—Enhancing spatial and temporal accessibility | n = 9 |

| A2—Strengthening the supply of diversity | n = 8 | |

| A3—Building participatory design | n = 2 | |

| Competence | C1—Adapting challenge goals | n = 6 |

| C2—Motivating competitive skills | n = 5 | |

| Relatedness | R1—Facilitating natural peer interactions | n = 4 |

| R2—Planning clear zoning of activities | n = 3 | |

| R3—Integration of elements of cultural values | n = 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, M.; Sun, B.; Li, Y. Children’s Well-Being of Physical Activity Space Design in Primary School Campus from the Perspective of Basic Psychological Needs. Buildings 2026, 16, 222. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010222

Song Q, Liu Y, Zhang Y, Huang M, Sun B, Li Y. Children’s Well-Being of Physical Activity Space Design in Primary School Campus from the Perspective of Basic Psychological Needs. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):222. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010222

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Qi, Yixin Liu, Yihao Zhang, Min Huang, Bingjie Sun, and Yuting Li. 2026. "Children’s Well-Being of Physical Activity Space Design in Primary School Campus from the Perspective of Basic Psychological Needs" Buildings 16, no. 1: 222. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010222

APA StyleSong, Q., Liu, Y., Zhang, Y., Huang, M., Sun, B., & Li, Y. (2026). Children’s Well-Being of Physical Activity Space Design in Primary School Campus from the Perspective of Basic Psychological Needs. Buildings, 16(1), 222. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010222