Assessment of BIM Maturity in Civil Engineering Education: A Diagnostic Study Applied to the Polytechnic School of the University of Pernambuco in the Brazilian Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. BIM Education

3. Methodology

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Questionnaire for Course Coordination

4.2. Questionnaire for the Information Technology Division

4.3. Questionnaire for Faculty Members

4.4. BIM Maturity Matrix for Higher Education Institutions (HEIs)

4.5. Contextualizing BIM Maturity Within the Higher Education Landscape

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BIM | Building Information Modeling |

| HEIs | higher education institutions |

| ITD | Information Technology Division |

| m2BIM-HEI | BIM Maturity Matrix for Higher Education Institutions |

| SDG 4 | Sustainable Development Goal 4 |

| STN | Structuring Teaching Nucleus |

| PIBc | Curricular BIM Implementation Plan |

| POLI/UPE | Polytechnic School of the University of Pernambuco |

References

- Ahmad, A.M.; Alkhaldi, A.; Al-Ali, S.; Al-Dweik, G.; Youssef, M. Developing Critical Success Factors (CSF) for Integrating Building Information Models (BIM) into Facility Management Systems (FMS). Buildings 2025, 15, 3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, I.A.; de Azevedo, V.F.B.; da Silva Neto, V.E.; Kohlman Rabbani, E.R.; Vasconcelos, B.M. Exploring the Role of BIM in Knowledge Management in Civil Construction Projects. Rev. Nac. Gerenciamento Cid. 2024, 12, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, H.; Chen, J.; Li, Q. A 3D Parameterized BIM-Modeling Method for Complex Engineering Structures in Building Construction Projects. Buildings 2024, 14, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, V.; Vasconcelos, B. Prevention of Accidents in Civil Construction: An Analysis of the Use of Digital Tools for Risk Mitigation in the Design Phase. arq.urb 2024, 39, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disney, O.; Arayici, Y.; Coates, P. Embracing BIM in Its Totality: A Total BIM Case Study. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2024, 13, 512–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, C.; Teicholz, P.; Sacks, R.; Liston, K. BIM Handbook: A Guide to Building Information Modeling for Owners, Managers, Designers, Engineers and Contractors, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio, A.Z.; Gomes, A.R.; Almeida, P.C. BIM Methodology in Structural Design: A Practical Case of Collaboration, Coordination, and Integration. Buildings 2023, 13, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brozovsky, J.; Labonnote, N.; Vigren, O. Digital Technologies in Architecture, Engineering, and Construction. Autom. Constr. 2024, 158, 105212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Succar, B.; Sher, W.; Williams, A. Measuring BIM Performance: Five Metrics. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2012, 8, 120–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X. Development and Implementation of a System for Electrical Engineering BIM Detailed Design in Construction Projects. Buildings 2025, 15, 2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Li, D.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y. BIM Adoption in Sustainability, Energy Modelling and Implementation Using ISO 19650: A Review. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, H.A.; Nugroho, A.; Fadli, M. Critical Government Strategies for Enhancing Building Information Modeling Implementation in Indonesia. Infrastructures 2023, 8, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotelino, E.D.; Natividade, V.; Travassos do Carmo, C.S. Teaching BIM and Its Impact on Young Professionals. J. Civ. Eng. Educ. 2020, 146, 05020005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazilian Federal Government. Federal Decree No. 9.377, of 17 May 2018. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2019-2022/2019/Decreto/D9983.htm#art15 (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Brazilian Federal Government. Federal Decree No. 10.306, of 2 April 2020. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2019-2022/2020/decreto/D10306.htm (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Checcucci, É.S.; Amorim, A.L. Method for Analyzing Curricular Components: Identifying Interfaces Between an Undergraduate Course and BIM. PARC Pesqui. Arquitetura Construção 2014, 5, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.A.I.; Ribeiro, R.A. The Inclusion of BIM in the Undergraduate Civil Engineering Course. In Proceedings of the 42nd Congresso Brasileiro de Educação em Engenharia (COBENGE 2014), Juiz de Fora, MG, Brazil, 16–19 September 2014; ABENGE: Brasilia, Brazil, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Böes, J.S.; Barros Neto, J.P.; de Lima, M.M.X. BIM Maturity Model for Higher Education Institutions. Ambiente Construído 2021, 21, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, V.F.B.; Rodrigues, I.A.; da Silva Neto, V.E.; Vasconcelos, B.M. Adoção de Softwares BIM na Disciplina de Arquitetura em Curso de Engenharia Civil. Periód. Téc. Cient. Cid. Verdes 2024, 12, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, L.O.; Catai, R.E.; Scheer, S. Analysis of Maturity Models for Measuring the Implementation of Building Information Modeling (BIM). Gestão Tecnol. Proj. 2021, 16, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alami, A.H.; Hassan, A.; Al-Khazaaleh, M.; Al-Shammari, M. 3D Concrete Printing: Recent Progress, Applications, Challenges, and Role in Achieving Sustainable Development Goals. Buildings 2023, 13, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, T.; Roofe, C.G. SDG 4 in Higher Education: Challenges and Opportunities. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alassaf, N. Computational Precedent-Based Instruction (CPBI): Integrating Precedents and BIM-Based Parametric Modeling in Architectural Design Studio. Buildings 2025, 15, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che Ibrahim, C.K.I.; Ahmad Kamal, N. A Bibliometric Exploration of Accreditation in Civil Engineering Education: Trends and Insights. Qual. Assur. Educ. 2025; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obi, L.I.; Omotayo, T.; Ekundayo, D.; Oyetunji, A.K. Enhancing BIM Competencies of Built Environment Undergraduate Students Using a Problem-Based Learning and Network Analysis Approach. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2024, 13, 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Adhikari, S. Bridging the Gap: Enhancing BIM Education for Sustainable Design Through Integrated Curriculum and Student Perception Analysis. Computers 2025, 14, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begić, H.; Galić, M. A Systematic Review of Construction 4.0 in the Context of the BIM 4.0 Premise. Buildings 2021, 11, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papuraj, X.; Izadyar, N.; Vrcelj, Z. Integrating Building Information Modelling into Construction Project Management Education in Australia: A Comprehensive Review of Industry Needs and Academic Gaps. Buildings 2025, 15, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolic, D.; Castronovo, F.; Leicht, R. Teaching BIM as a Collaborative Information Management Process Through a Continuous Improvement Assessment Lens: A Case Study. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2021, 28, 2248–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Károlyfi, K.A.; Szalai, D.; Szép, J.; Horváth, T. Integration of BIM in Architecture and Structural Engineering Education Through Common Projects. Acta Tech. Jaurinensis 2021, 14, 424–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lot Tanko, B.; Mbugua, L. BIM Education in Higher Learning Institutions: A Scientometric Review and the Malaysia Perspective. Int. J. Built Environ. Sustain. 2021, 9, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keung, C.C.W.; Yiu, T.W.; Feng, Z. Building Information Modeling Education for Quantity Surveyors in Hong Kong: Current States, Education Gaps, and Challenges. Int. J. Constr. Educ. Res. 2023, 19, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, E.; Kähkönen, K. BIM-Enabled Education: A Systematic Literature Review. In Proceedings of the 10th Nordic Conference on Construction Economics and Organization, Tallinn, Estonia, 7–8 May 2019; Emerald Publishing: Leeds, UK, 2019; pp. 261–269. [Google Scholar]

- Besné, A.; Pérez, M.Á.; Necchi, S.; Peña, E.; Fonseca, D.; Navarro, I.; Redondo, E. A Systematic Review of Current Strategies and Methods for BIM Implementation in the Academic Field. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alencar, L.; Barros, K.; Costa, K.; Toledo, A. A Utilização do BIM como Ferramenta de Ensino no Brasil: Uma Revisão Bibliométrica e Sistemática. Rev. Ímpeto 2023, 13, 51–65. [Google Scholar]

- Algahtany, M.; Radzi, A.R.; Al-Mohammad, M.S.; Rahman, R.A. Government Initiatives for Enhancing Building Information Modeling Adoption in Saudi Arabia. Buildings 2023, 13, 2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batistello, P.; Balzan, K.L.; Pereira, A.T.C. BIM no Ensino das Competências em Arquitetura e Urbanismo: Transformação Curricular. PARC Pesqui. Arquitetura Construção 2019, 10, e019019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, M.S. BIM and the Future of Architecture Teaching. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Santander, Espanha; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2022; Volume 1101, p. 052024. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos, B.; Germano, J.V.M. Percepção do BIM por Projetistas do Setor da AECO em Pernambuco. Rev. Proj.-Proj. Percepção Ambiente 2023, 8, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, L.A.M.N.; Guilherme, I.S.; Oliveira, D.M. BIM no Mercado da Construção Civil Percepção e Capacitação de Novos Engenheiros. Construindo 2023, 15, 25–37. Available online: https://revista.fumec.br/index.php/construindo/article/view/9757 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Silva, A.R.; Lima, J.W.M.; Lima, S.P. BIM no Ensino de Engenharia no Brasil: Avanços, Barreiras e Como as Instituições Respondem às Necessidades do Mercado. Cuad. Educ. Desarro. 2025, 17, e9217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mohamadsaleh, A.; Alzahrani, S. Development of a Maturity Model for Software Quality Assurance Practices. Systems 2023, 11, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griz, C.; Rocha, P.; Lima, F. BIM Adoption in an Architecture and Urbanism Course: Analysis of the Degree of Maturity. In Proceedings of the Sociedad Iberoamericana de Gráfica Digital (SIGraDi 2022), Lima, Peru, 7–11 November 2022; Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas: Lima, Peru, 2022; pp. 799–810. [Google Scholar]

- Alankarage, S.; Chong, H.Y.; Hosseini, M.R.; Chileshe, N. Organisational BIM Maturity Models and Their Applications: A Systematic Literature Review. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2023, 19, 567–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahamadu, A.-M.; Mahdjoubi, L.; Booth, C. The Importance of BIM Capability Assessment: An Evaluation of Post-Selection Performance of Organisations on Construction Projects. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2019, 27, 24–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Madalli, D.P. Maturity Models in LIS Study and Practice. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 2021, 43, 101069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginzburg, A.; Shilova, L.; Adamtsevich, A.; Shilov, L. Implementation of BIM-Technologies in Russian Construction Industry According to the International Experience. J. Appl. Eng. Sci. 2016, 14, 457–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruikar, D. Using BIM to Mitigate Risks Associated with Health and Safety in the Construction and Maintenance of Infrastructure Assets. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 204, 873–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messner, J.; Anumba, C.; Dubler, C.; Goodman, S.; Kasprzak, C.; Kreider, R.; Leicht, R.; Saluja, C.; Zikic, N.; Bhawani, S. BIM Project Execution Planning Guide, Version 3.0; The Pennsylvania State University: University Park, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fantin, N.R. Possibilidades e Limitações da Implementação do BIM no Ensino de Arquitetura e Urbanismo do CAU/FAU/UFJF. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora, Juiz de Fora, Brazil, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ruschel, R.C.; Ferreira, S.L. Rede de Células BIM ANTAC. In Encontro Nacional sobre o Ensino de BIM; ANTAC: Porto Alegre, Brasil, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hippert, A.; Molina, M.A. Inserção do BIM na Formação em Engenharia Civil: Análise e Reflexões. In Proceedings of the 3rd Portuguese Congress on Building Information Modeling, Porto, Portugal, 26–27 November and 4 December 2020; Faculdade de Engenharia da Universidade do Porto: Porto, Portugal, 2020; pp. 213–222. [Google Scholar]

- Arrotéia, A.V.; Freitas, R.C.; Melhado, S.B. Barriers to BIM Adoption in Brazil. Front. Built Environ. 2021, 7, 520154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, V.F.B.; Rodrigues, I.A.; da Silva Neto, V.E.; Soares, W.A.; Vasconcelos, B.M. Uso de Metodologias Ativas no Ensino de Arquitetura na Graduação de Engenharia Civil. Rev. Ibero-Am. Estud. Educ. 2024, 19, e024094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 19650-1:2018; Organization and Digitization of Information about Buildings and Civil Engineering Works, Including Building Information Modelling (BIM)—Information Management Using Building Information Modelling. Part 1: Concepts and Principles. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Abanda, F.H.; Balu, B.; Adukpo, S.E.; Akintola, A. Decoding ISO 19650 Through Process Modelling for Information Management and Stakeholder Communication in BIM. Buildings 2025, 15, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

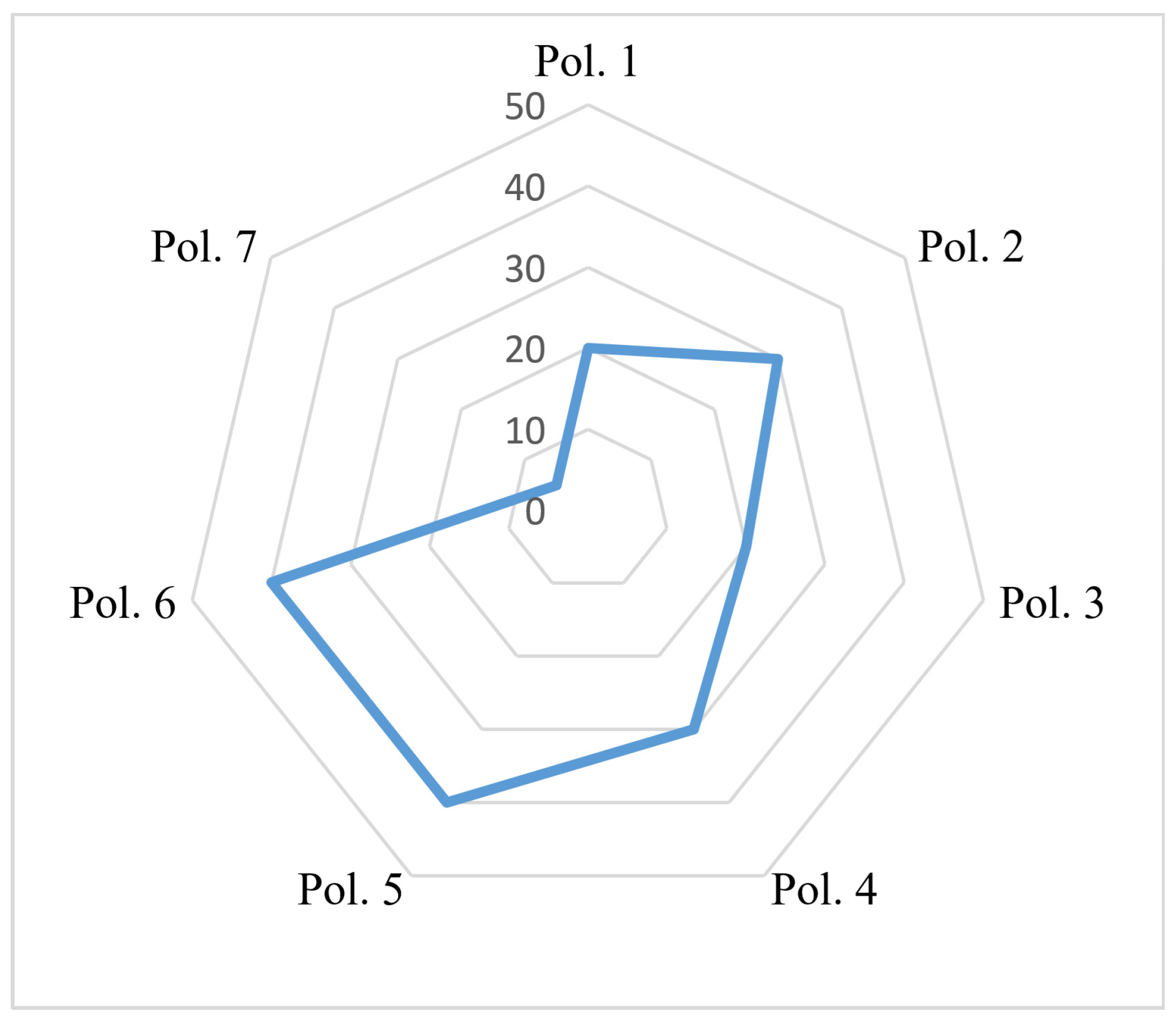

| Fields of Analysis | Evaluation Criteria |

|---|---|

| Policy Encompasses all institutional initiatives, actions, and strategic visions related to BIM. | Faculty Training (Pol. 1) |

| Faculty BIM Engagement (Pol. 2) | |

| Institutional BIM Vision (Pol. 3) | |

| BIM Teaching (Pol. 4) | |

| Academic Extension (Pol. 5) | |

| Research Initiatives (Pol. 6) | |

| Federal Decree 11.888/2024 (Pol. 7) | |

| Process Encompasses the performance of teaching, research, and extension activities involving BIM. | BIM Uses (Pro. 1) |

| BIM-related Courses (Pro. 2) | |

| Publications (Pro. 3) | |

| Trained Students (Pro. 4) | |

| Technology Encompasses all technological and physical infrastructure required for the development of BIM-based education. | Institutional Agreements with Software Developers (Tec. 1) |

| Software Availability (Tec. 2) | |

| Agreements with Hardware Manufacturers (Tec. 3) | |

| Hardware Availability (Tec. 4) | |

| Infrastructure (Tec. 5) |

| Indicator | Maturity Index | Maturity Level | Qualitative Classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0–19% | Pre-BIM | No maturity |

| B | 20–39% | Initial | Low maturity |

| C | 40–59% | Defined | Medium maturity |

| D | 60–79% | Integrated | High maturity |

| E | 80–100% | Optimized | Very high maturity |

| Target Group | Sample Field | Respondents | Response Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Course Coordination | 1 | 1 | 100.00% |

| Information Technology Division (ITD) | 1 | 1 | 100.00% |

| Faculty Members of the Civil Engineering Program at POLI/UPE | 34 | 94 | 36.17% |

| Members of the Structuring Teaching Nucleus (STN) of the Civil Engineering Program at POLI/UPE | 4 | 4 | 66.67% |

| Category | Criterion | Score | Maturity Level | Maturity Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy | Pol. 1 | 20 | 26.43 | 52.86% |

| Pol. 2 | 30 | |||

| Pol. 3 | 20 | |||

| Pol. 4 | 30 | |||

| Pol. 5 | 40 | |||

| Pol. 6 | 40 | |||

| Pol. 7 | 5 | |||

| Processes | Pro. 1 | 30 | 35.75 | 71.00% |

| Pro. 2 | 30 | |||

| Pro. 3 | 50 | |||

| Pro. 4 | 32 | |||

| Technology | Tec. 1 | 30 | 25.00 | 50.00% |

| Tec. 2 | 40 | |||

| Tec. 3 | 5 | |||

| Tec. 4 | 30 | |||

| Tec. 5 | 20 | |||

| Total | 452 | 28.25 | 56.50% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Azevedo, V.F.B.d.; Lago, E.M.G.; Griz, C.M.S.; Gusmão, A.D.; Vasconcelos, B.M. Assessment of BIM Maturity in Civil Engineering Education: A Diagnostic Study Applied to the Polytechnic School of the University of Pernambuco in the Brazilian Context. Buildings 2026, 16, 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010221

Azevedo VFBd, Lago EMG, Griz CMS, Gusmão AD, Vasconcelos BM. Assessment of BIM Maturity in Civil Engineering Education: A Diagnostic Study Applied to the Polytechnic School of the University of Pernambuco in the Brazilian Context. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):221. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010221

Chicago/Turabian StyleAzevedo, Vinícius Francis Braga de, Eliane Maria Gorga Lago, Cristiana Maria Sobral Griz, Alexandre Duarte Gusmão, and Bianca M. Vasconcelos. 2026. "Assessment of BIM Maturity in Civil Engineering Education: A Diagnostic Study Applied to the Polytechnic School of the University of Pernambuco in the Brazilian Context" Buildings 16, no. 1: 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010221

APA StyleAzevedo, V. F. B. d., Lago, E. M. G., Griz, C. M. S., Gusmão, A. D., & Vasconcelos, B. M. (2026). Assessment of BIM Maturity in Civil Engineering Education: A Diagnostic Study Applied to the Polytechnic School of the University of Pernambuco in the Brazilian Context. Buildings, 16(1), 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010221