Heritage Conservation and Management of Traditional Anhui Dwellings Using 3D Digitization: A Case Study of the Architectural Heritage Clusters in Huangshan City

Abstract

1. Introduction

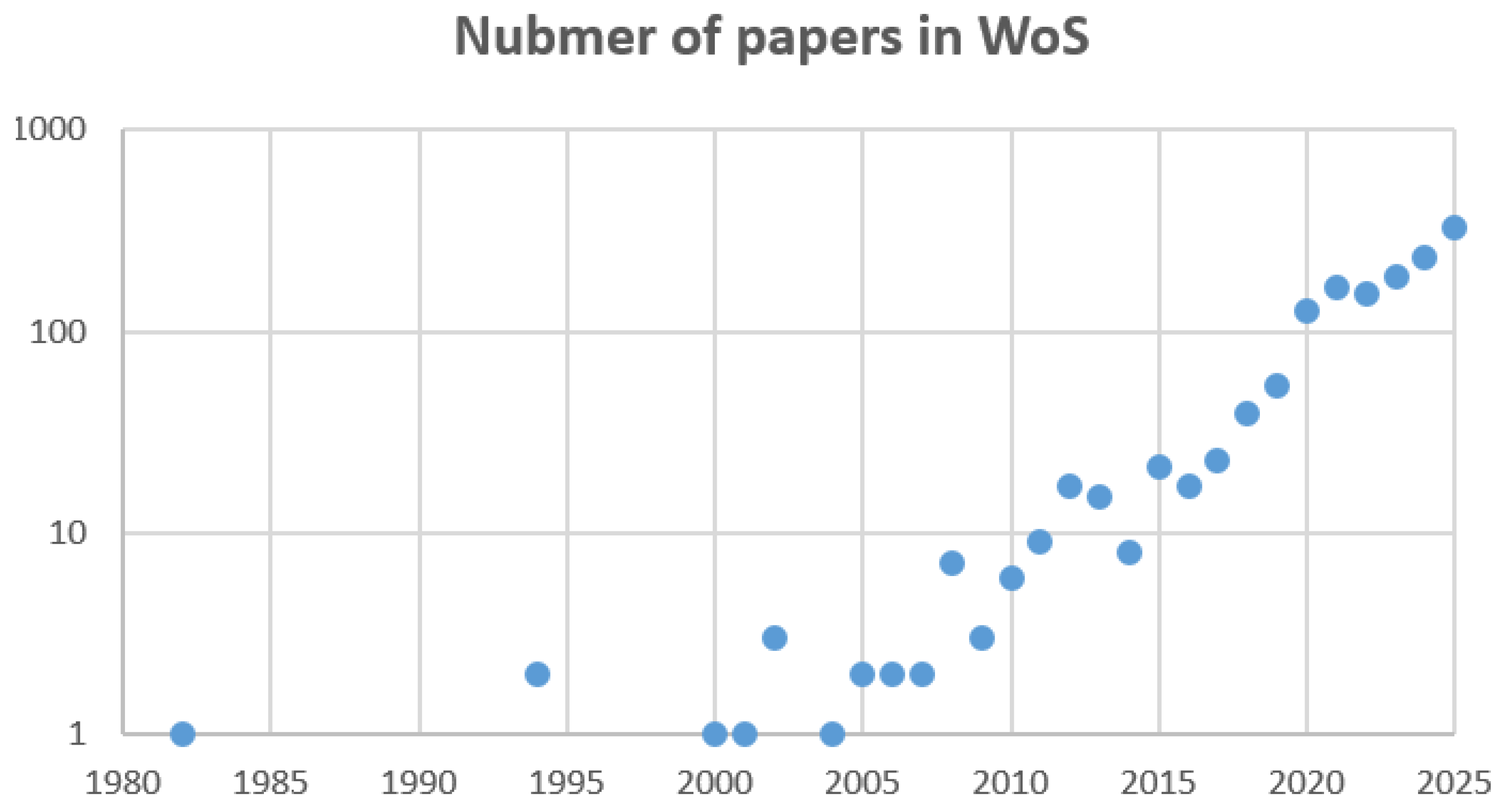

2. Literature Review

- (1)

- The objects addressed in architectural heritage protection include ancient buildings, cultural relics, traditional villages, historic districts, and archeological sites. From the perspective of heritage classification, these objects can be broadly categorized into cultural landscapes, natural heritage, and historic urban landscapes.

- (2)

- Digital technologies applied to architectural heritage conservation can be grouped into several major categories, including three-dimensional (3D) laser scanning, Building Information Modeling (BIM), virtual reality (VR), 3D reconstruction, point cloud–based processing, UAV-based photogrammetry, and oblique photography.

- (1)

- Heritage Data Acquisition and Collection Technologies represented by 3D laser scanning;

- (2)

- Management Technologies represented by HBIM;

- (3)

- Dissemination and Sharing Technologies represented by virtual reality.

3. Materials and Methods

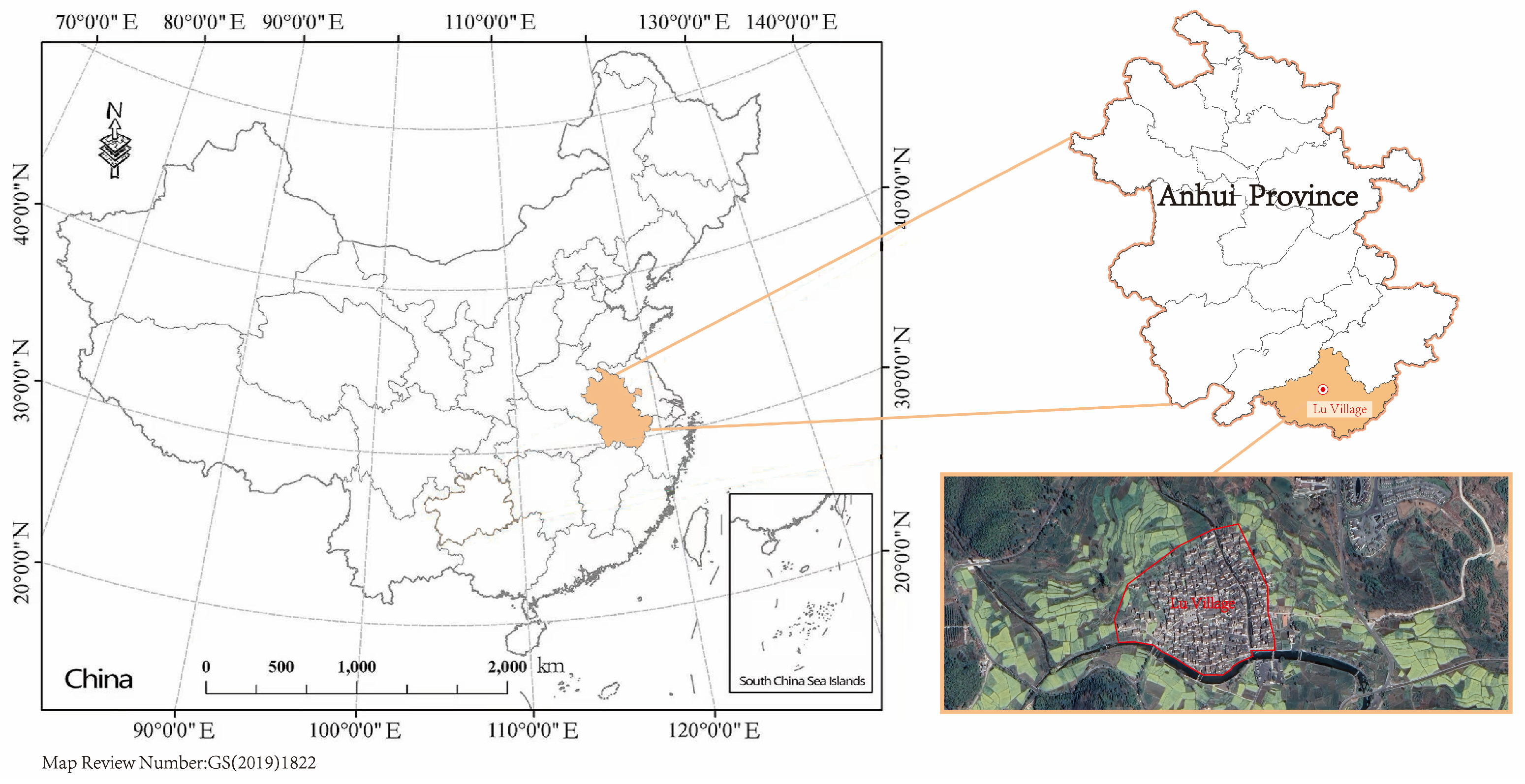

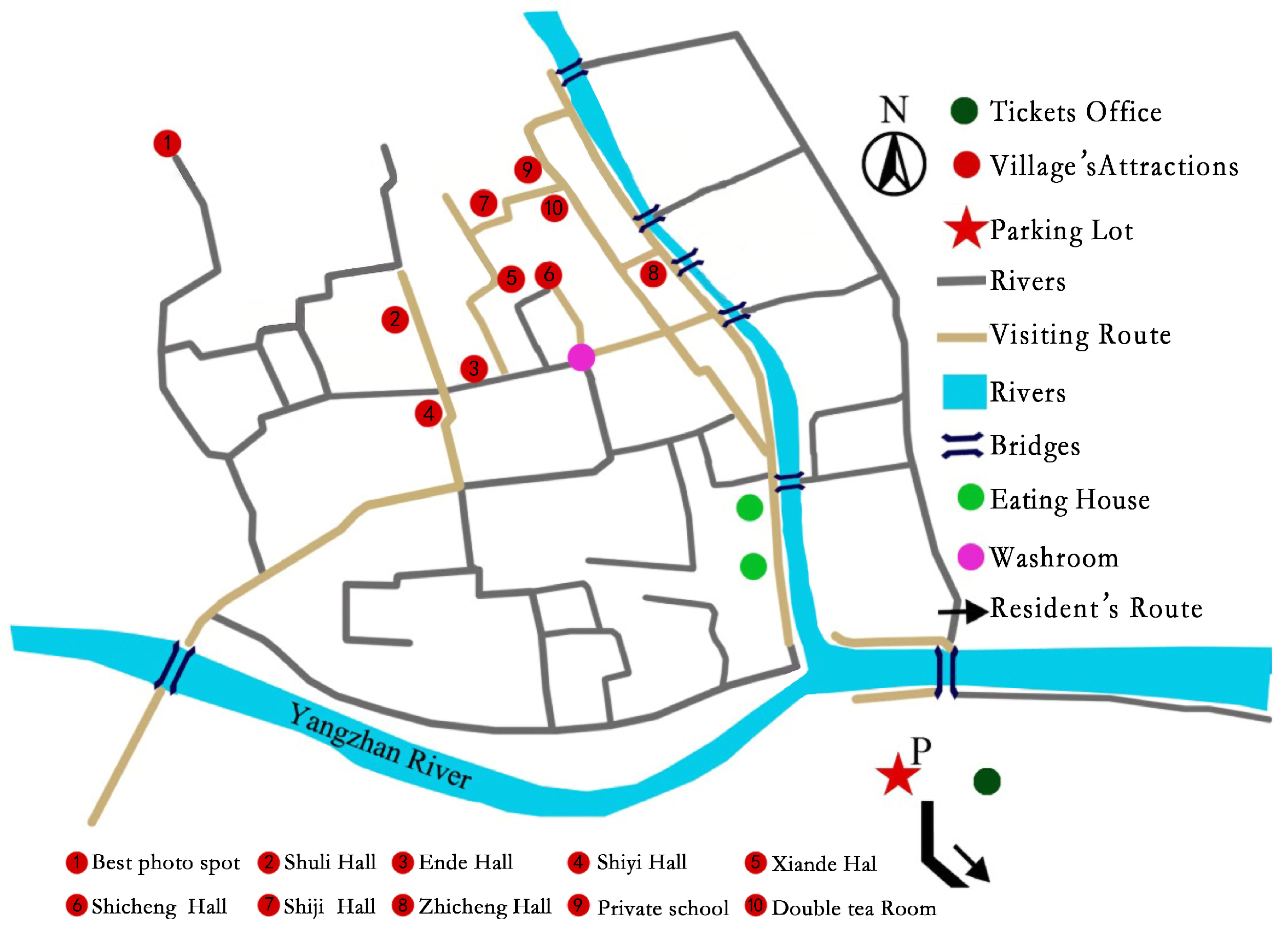

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Angle Positioning Principle

Y = S × cosβ × sinα

Z = S × sinβ

3.2.2. Structural Algorithms of Network Models

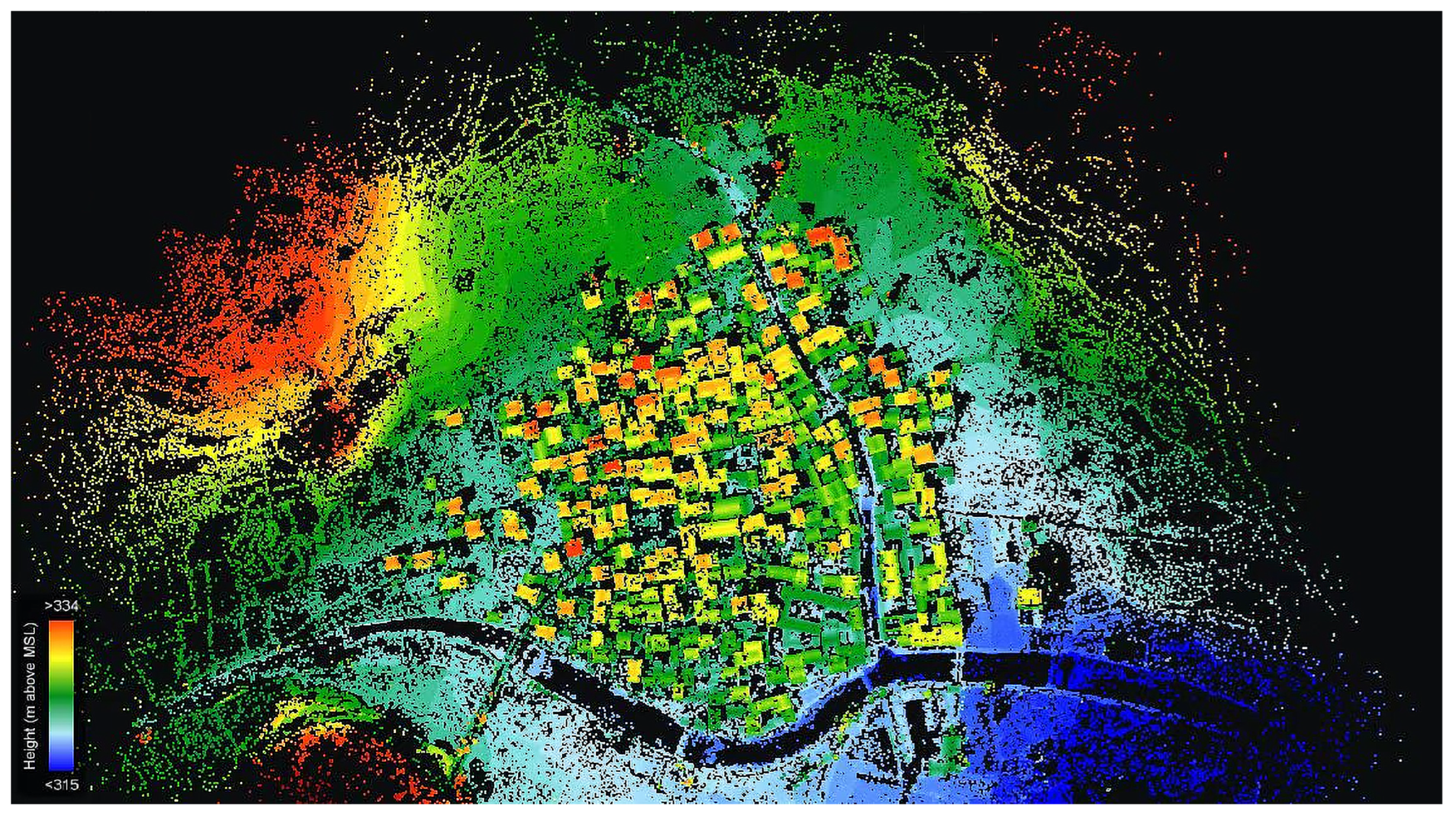

3.2.3. Acquisition of 3D Point Cloud Data Using 3D Laser Scanning

4. Result

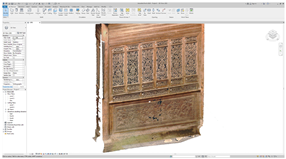

4.1. HBIM Generation Based on Segmented Point Clouds

4.2. Texturing in HBIM Models

5. HBIM Component Library Construction

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shen, H.; Aziz, N.F.; Lv, X. Using 360-Degree Panoramic Technology to Explore the Mechanisms Underlying the Influence of Landscape Features on Visual Landscape Quality in Traditional Villages. Ecol. Inform. 2025, 86, 103036. [Google Scholar]

- Apollonio, F.I.; Gaiani, M.; Sun, Z. A reality integrated BIM for architectural heritage conservation. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2016, 3, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banfi, F. HBIM generation: Extending geometric primitives and BIM modelling tools for heritage structures and complex vaulted systems. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, 42, 139–148. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno, N.; Roncella, R. HBIM for conservation: A new proposal for information modeling. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yan, A.; Sun, H. Study on Landscape Characteristics and Formation Mechanism of Chinese Traditional Settlements Based on Niche Theory. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Green Building, Civil Engineering and Smart City, GBCESC 2023; Guo, W., Qian, K., Tang, H., Gong, L., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2024; Volume 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Li, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Shao, W.; Shi, T. Similarity and stability: A study on the color features of regional built spaces—Taking Chinese Hui-style architecture as an example. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 24, 3625–3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Li, Z.; Xia, S.; Gao, M.; Ye, M.; Shi, T. Research on the Spatial Sequence of Building Facades in Huizhou Regional Traditional Villages. Buildings 2023, 13, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiabrando, F.; Sammartano, G.; Spanò, A. Historical buildings models and their handling via 3D survey: From points clouds to user-oriented HBIM. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2016, 41, 633–640. [Google Scholar]

- Dore, C.; Murphy, M. Integration of Historic Building Information Modeling (HBIM) and 3D GIS for recording and managing cultural heritage sites. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Virtual Systems and Multimedia: “Virtual Systems in the Information Society”, Milan, Italy, 2–5 September 2012; pp. 369–376. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, H.; Sun, Z. High-Definition Survey of Architectural Heritage Fusing Multisensors—The Case of Beamless Hall at Linggu Temple in Nanjing, China. Sensors 2022, 22, 3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassi, F.; Fregonese, L.; Ackermann, S.; De Troia, V. Comparison between laser scanning and automated 3d modelling techniques to reconstruct complex and extensive cultural heritage areas. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2013, 40, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionizio, R.F.; López-Chao, V. Integrating HBIM and WebGIS for the Documentation, Visualization and Management of Modern Architectural Heritage Sites. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2025, 19, 3530–3549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fregonese, L.; Barbieri, G.; Biolzi, L.; Bocciarelli, M.; Frigeri, A.; Taffurelli, L. Surveying and Monitoring for Vulnerability Assessment of an Ancient Building. Sensors 2013, 13, 9747–9773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Aguilera, D.; Rodríguez-Gonzálvez, P.; Gómez-Lahoz, J. An automatic procedure for co-registration of terrestrial laser scanners and digital cameras. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2009, 64, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grussenmeyer, P.; Landes, T.; Voegtle, T.; Ringle, K. Comparison methods of terrestrial laser scanning, photogrammetry and tacheometry data for recording of cultural heritage buildings. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2008, 37, 213–218. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, G.; Ryan, C.; Deng, Z.; Gong, J. Creating a softening cultural-landscape to enhance tourist experiencescapes: The case of Lu Village. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2024, 53, 101245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, X.; Dong, R.; Hou, Q. Study on Spatial Adaptability of Tangjia Village in the Weibei Loess Plateau Gully Region Based on Diverse Social Relationships. Land 2025, 14, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Hu, W.; Zhang, G. Research on fine model reconstruction method of ancient architecture based on least squares method. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersten, T.; Tschirschwitz, F.; Deggim, S.; Lindstaedt, M. Virtual reality for cultural heritage monuments—From 3D data recording to immersive visualisation. In Digital Heritage. Progress in Cultural Heritage: Documentation, Preservation, and Protection; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kioussi, A.; Karoglou, M.; Bakolas, A. Digital technologies for the conservation and promotion of cultural heritage. J. Cult. Herit. 2019, 36, 264–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limongiello, M.; Musmeci, D.; Radaelli, L.; Chiumiento, A.; di Filippo, A.; Limongiello, I. Parametric GIS and HBIM for Archaeological Site Management and Historic Reconstruction Through 3D Survey Integration. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Giordano, A.; Sang, K.; Stendardo, L.; Yang, X. Application of Terrestrial Laser Scanning in 3D Modeling of Traditional Village: A Case Study of Fenghuang Village in China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Li, G.; Giordano, A.; Sang, K.; Stendardo, L.; Yang, X. Three-Dimensional Documentation and Reconversion of Architectural Heritage by UAV and HBIM: A Study of Santo Stefano Church in Italy. Drones 2024, 8, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiabrando, F.; Lo Turco, M.; Rinaudo, F. Modeling the decay in an hbim starting from 3d point clouds. A followed approach for cultural heritage knowledge. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2017, XLII-2/W5, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macher, H.; Landes, T. Grussenmeyer, From point clouds to building information models: 3D semi-automatic reconstruction of indoors of existing buildings. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J. Multi-Image Photogrammetry for Heritage Recording: A Guide to Good Practice; English Heritage Publishing: Swindon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, D.; Sperner, J.; Hoepner, S.; Tenschert, R. Terrestrial laser scanning for heritage conservation: The Cologne Cathedral documentation project. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2017, IV-2-W2, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.; McGovern, E.; Pavia, S. Historic building information modelling (HBIM). Struct. Surv. 2009, 27, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesci, A.; Teza, G.; Casula, G. Terrestrial laser scanning for monitoring the stability of historic buildings. J. Cult. Herit. 2011, 12, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Lin, Q.; Ye, S. Deep learning based approaches from semantic point clouds to semantic BIM models for heritage digital twin. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remondino, F.; Campana, S. 3D Recording and Modelling in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage: Theory and Best Practices; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2014; ISBN 9781905739599. [Google Scholar]

- I Capó, A.J.; Gomez, J.V.; Moyà, G.; Perales, F. Rehabilitación motivacional basada en la utilización de serious games. Virtual Archaeol. Rev. 2013, 4, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, R.; Medcalf, K.; Brown, A.; Bunting, P.; Breyer, J.; Clewley, D.; Keyworth, S.; Blackmore, P. Updating the Phase 1 habitat map of Wales, UK, using satellite sensor data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2011, 66, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Xu, Z. The Application of Digital Technology in the Conservation of Huizhou Traditional Architecture: The Case of Wooden Carving Building in Lu Village, Yi County. Dev. Small Cities Towns 2024, 42, 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Stylianidis, E.; Remondino, F. 3D Recording, Documentation and Management of Cultural Heritage; Whittles Publishing: Dunbeath, UK, 2016; ISBN 9781849951606. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, R.; Jiang, B.; Liu, S.; Zhang, J. Game Engine Technology in Cultural Heritage Digitization Application Prospect–Taking the Digital Cave of the Mogao Caves in China as an Example. In Virtual, Augmented and Mixed Reality; HCII 2024; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Chen, J.Y.C., Fragomeni, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 14708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oreni, D.; Brumana, R.; Georgopoulos, A.; Cuca, B. HBIM for conservation and management of built heritage: Towards a library of vaults and wooden bean floors. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2013, II-5/W1, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucci, G.; Bonora, V.; Conti, A.; Fiorini, L. High-quality 3D models and their use in a cultural heritage conservation project. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2017, XLII-2/W5, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W. Research on the Application of UAV Oblique Photography Algorithm in the Protection of Traditional Village Cultural Heritage. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Computing Methodologies and Communication (ICCMC), Erode, India, 29–31 March 2022; pp. 1303–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yastikli, N. Documentation of cultural heritage using digital photogrammetry and laser scanning. J. Cult. Herit. 2007, 8, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xiong, W.; Shao, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, F. Analyses of the Spatial Morphology of Traditional Yunnan Villages Utilizing Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Remote Sensing. Land 2023, 12, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, C. Classification and Application of Digital Technologies in Landscape Heritage Protection. Land 2022, 11, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cluster | Keyword | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Three-dimensional laser scanner | Three-dimensional model | 32 |

| Digital technique | 32 | |

| 3d digitalization | 26 | |

| Heritage building | 18 | |

| Point cloud | 17 | |

| Drone photography | 17 | |

| Point cloud data | 12 | |

| Precise measurement | 6 | |

| Feature extraction | 3 | |

| Protecting mapping and surveying | 2 | |

| BIM | Digital protection system | 22 |

| Informatization | 17 | |

| Architectural conservation | 14 | |

| Historical Building Cloud Platform | 13 | |

| Recover | 12 | |

| Digital information platform | 12 | |

| Parametric Component | 9 | |

| Informationization expression | 7 | |

| Point cloud denoising processing | 6 | |

| Simulated analysis | 4 | |

| Forward and backward modeling | 2 | |

| Virtual reality | Digitalization of Cultural Heritage | 12 |

| Three-dimensional technology | 8 | |

| VR image | 6 | |

| Virtual museum | 6 | |

| Virtual interaction | 5 | |

| Augmented reality (AR) | 4 | |

| Construction Tour | 2 | |

| Immersive roaming | 1 |

| Drone Specifications | UAV Parameters | Camera Specifications | Camera Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagonal wheelbase | About 380.1 mm | Model of camera | Five global shutter sensors |

| Maximum take-off weight | 1050 g | Image sensor | 5 × 1/2.8 inches CMOS, effective pixels 5 million |

| Maximum take-off altitude | 6000 m | Equivalent focal length | 25 mm |

| Hovering accuracy | Vertical: ±0.1 m | Camera angle | Foresight: Horizontal 90°, Perpendicular103° Back vision: Horizontal 90°, Perpendicular 103° Side-looking: Horizontal 90°, Perpendicular 85° Upward view: Front and back 100°, Left and right 90° Downward view: Front and back 130°, Left and right 160° |

| Accuracy: ±0.3 m | |||

| Battery capacity | 5000 mAh | Lens stop | f/2.0 |

| Battery life duration | About 42 min | Picture size | 2592 × 1944 |

| Distannce Accuracy | Range | Measurement Rate | Laser Class | Integrated Color Camera | Operating Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Up to ±1 mm | 0.6 m to 350 m | Up to 976,000 points/s | 1 | Yes | +5 °C to +40 °C |

| Limited Texture and Surface Capture | Three-Dimensional Laser Scanning | Three-Dimensional Laser Scanning |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution Varies with Range | Yes | Consistent within a single flight |

| Slower Scanning Speeds | Yes | Faster data capture compared to scanning |

| Challenges with Reflective Surfaces | Yes | Can be mitigated with proper scanning techniques |

| Bulky Traditional Scanners (Some Models) | Yes | Lightweight equipment |

| Lower Accuracy than Laser Scanning | Yes | Yes |

| Requires Reference Points for Scale | Yes | Yes |

| Longer Processing Times for Complex Models | Yes | Faster than processing large scan datasets |

| Subject to Weather Conditions and Airspace Regulations | Yes | Yes |

| Model | Number Before Filtering | Number After Filtering | Filtering Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sicheng Hall | 6,510,111,443 | 2,799,347,920 | 43% |

| Shuangcha Hall | 8,043,468,140 | 2,815,213,849 | 35% |

| Siyi Hall | 9,456,721,123 | 4,160,957,294 | 44% |

| Chongde Hall | 8,237,454,054 | 2,800,734,378 | 34% |

| Zhicheng Hall | 6,787,908,237 | 2,647,284,212 | 39% |

| Shuli Hall | 31,548,481,074 | 11,672,937,997 | 37% |

| Detailed Information of the Components | The Display Results Within HBIM |

|---|---|

| The Que-ti of Zhicheng Hall |  |

| The wooden railings on the second floor of Zhicheng Hall |  |

| The wooden doors and windows on the first floor of Zhicheng Hall |  |

| The wooden straight beams inside the hall of Zhicheng Hall |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, J.; Zhong, J.; Ning, Q.; Xu, Z.; Fukuda, H. Heritage Conservation and Management of Traditional Anhui Dwellings Using 3D Digitization: A Case Study of the Architectural Heritage Clusters in Huangshan City. Buildings 2026, 16, 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010211

Chen J, Zhong J, Ning Q, Xu Z, Fukuda H. Heritage Conservation and Management of Traditional Anhui Dwellings Using 3D Digitization: A Case Study of the Architectural Heritage Clusters in Huangshan City. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):211. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010211

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Jianfu, Jie Zhong, Qingqian Ning, Zhengjia Xu, and Hiroatsu Fukuda. 2026. "Heritage Conservation and Management of Traditional Anhui Dwellings Using 3D Digitization: A Case Study of the Architectural Heritage Clusters in Huangshan City" Buildings 16, no. 1: 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010211

APA StyleChen, J., Zhong, J., Ning, Q., Xu, Z., & Fukuda, H. (2026). Heritage Conservation and Management of Traditional Anhui Dwellings Using 3D Digitization: A Case Study of the Architectural Heritage Clusters in Huangshan City. Buildings, 16(1), 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010211