1.1. Background

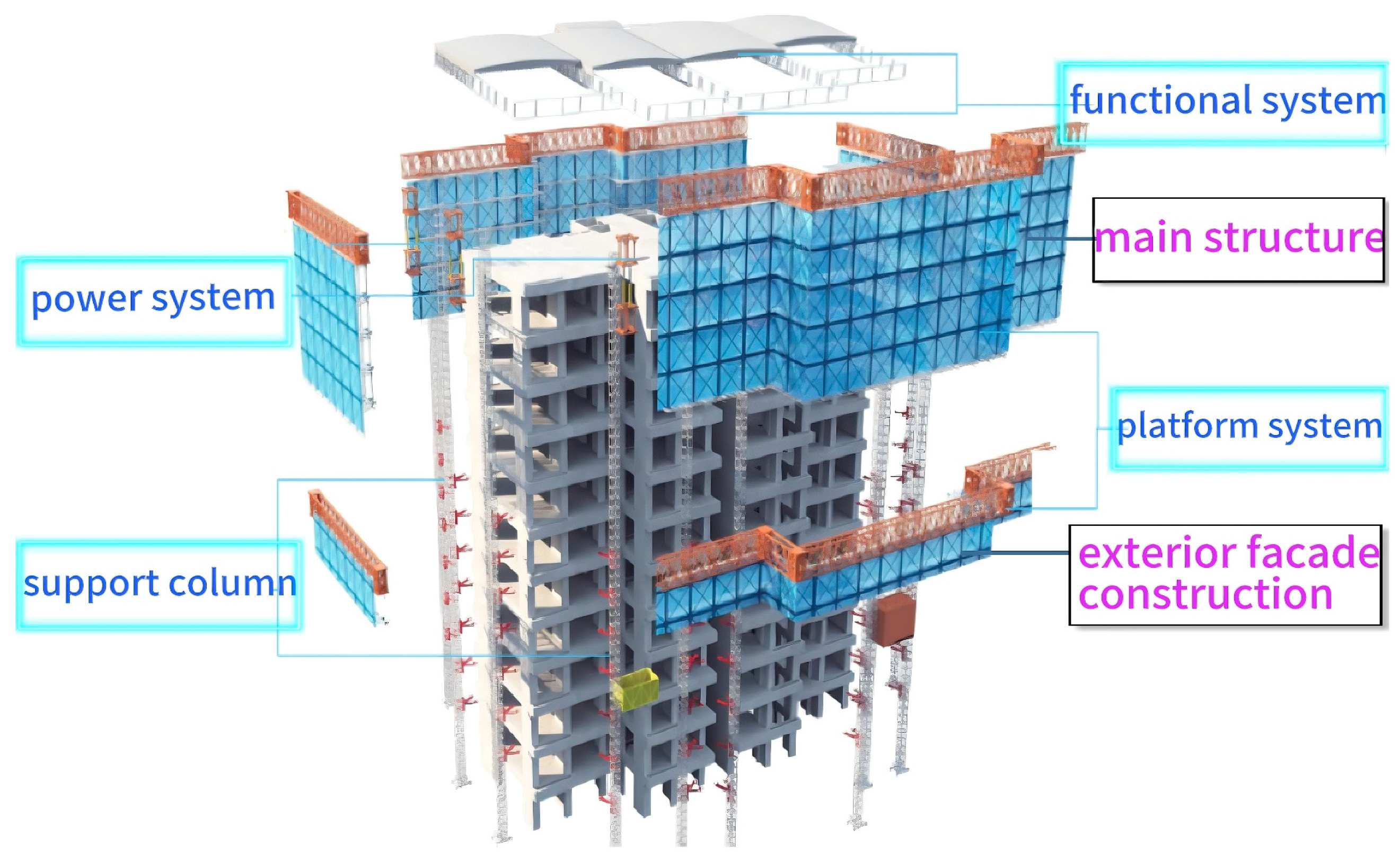

With the rapid increase in the number of high-rise and super high-rise buildings in China, the demand for efficient, safe, and intelligent construction equipment on job sites has grown significantly. Traditional scaffolding systems and single-platform integrated platforms are increasingly unable to meet the requirements of modern construction industrialization in terms of efficiency, space utilization, and safety assurance. The traditional single-platform integrated system is characterized by having only one lifting platform, where construction activities are carried out sequentially on the same level, resulting in a relatively simple workflow. Although this approach features a straightforward structure and intuitive management, it has notable limitations. In contrast, the dual-platform integrated system is equipped with two vertically arranged platforms that can operate independently within the same lifting system, enabling spatial separation and temporal overlap of structural and facade operations. The upper platform is primarily responsible for main structural construction, while the lower platform is used for facade operations, thereby achieving concurrent progress of structural works and facade installation. The system consists of four major components: the supporting system, power system, platform system, and functional system, collectively creating a factory-like construction environment on site. By coordinating two simultaneous workfaces, the dual-platform system transforms traditional high-altitude operations into standardized, factory-style production. Compared with conventional single-platform systems used in high-rise construction, it offers significant advantages in construction efficiency, safety, adaptability, and intelligent operation. The construction diagram of the dual-platform integrated platform is shown in

Figure 1.

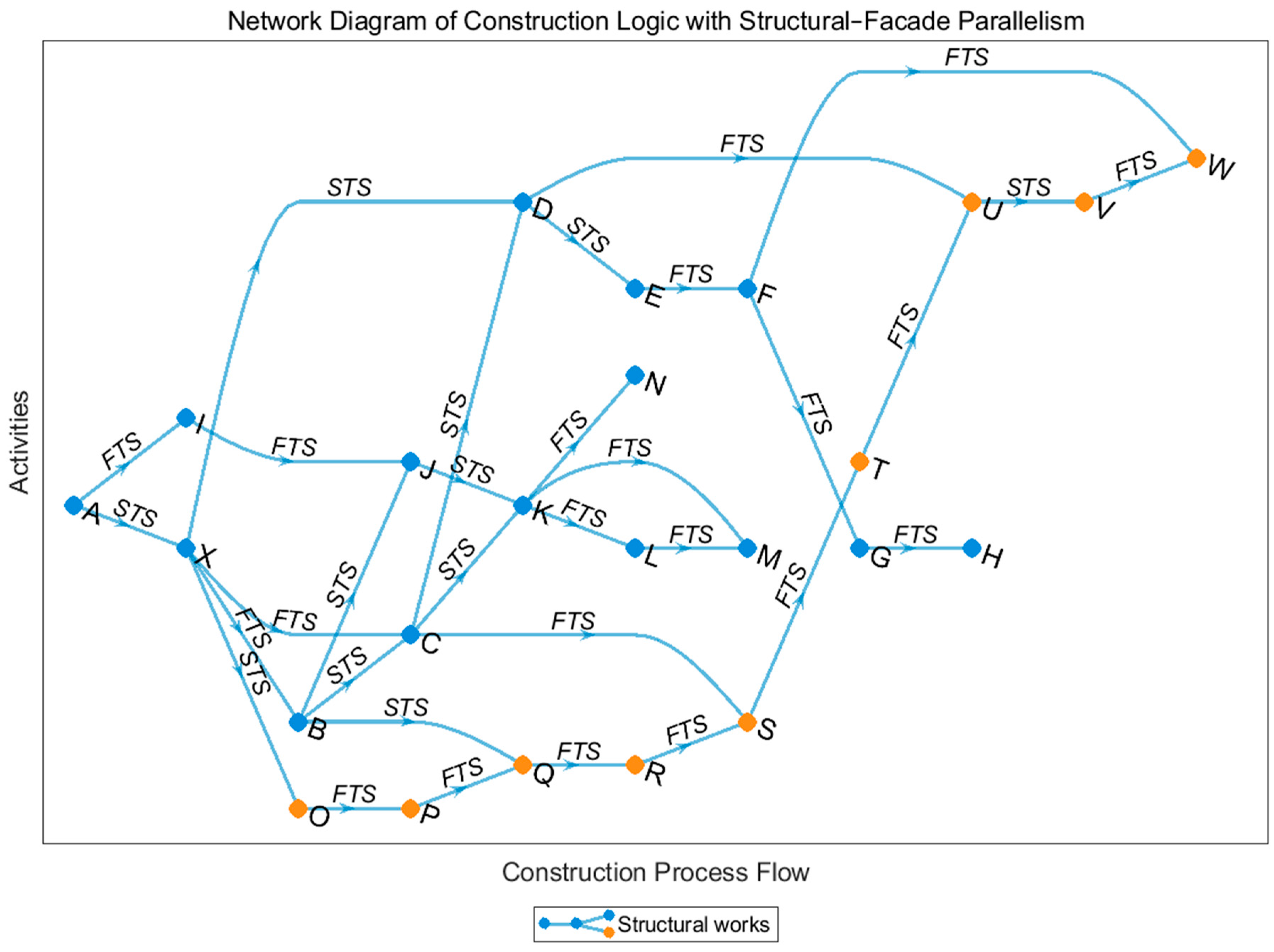

However, in actual engineering projects, the construction process of dual-platform integrated systems still largely follows the traditional serial-oriented approach, resulting in poor coordination between the two platforms. Currently, how to achieve optimized construction scheduling under multi-platform collaborative conditions has become a critical issue in high-rise construction management. Traditional schedules typically treat each “floor” as a single construction unit, overlooking the parallelism and interleaving relationships both between floors and within each floor. Meanwhile, the lack of precise temporal and spatial coordination between structural works and facade operations leads to process interruptions and resource waste. With the development of intelligent algorithms, construction schedule optimization based on genetic algorithms has gradually become an important method for improving construction organization efficiency.

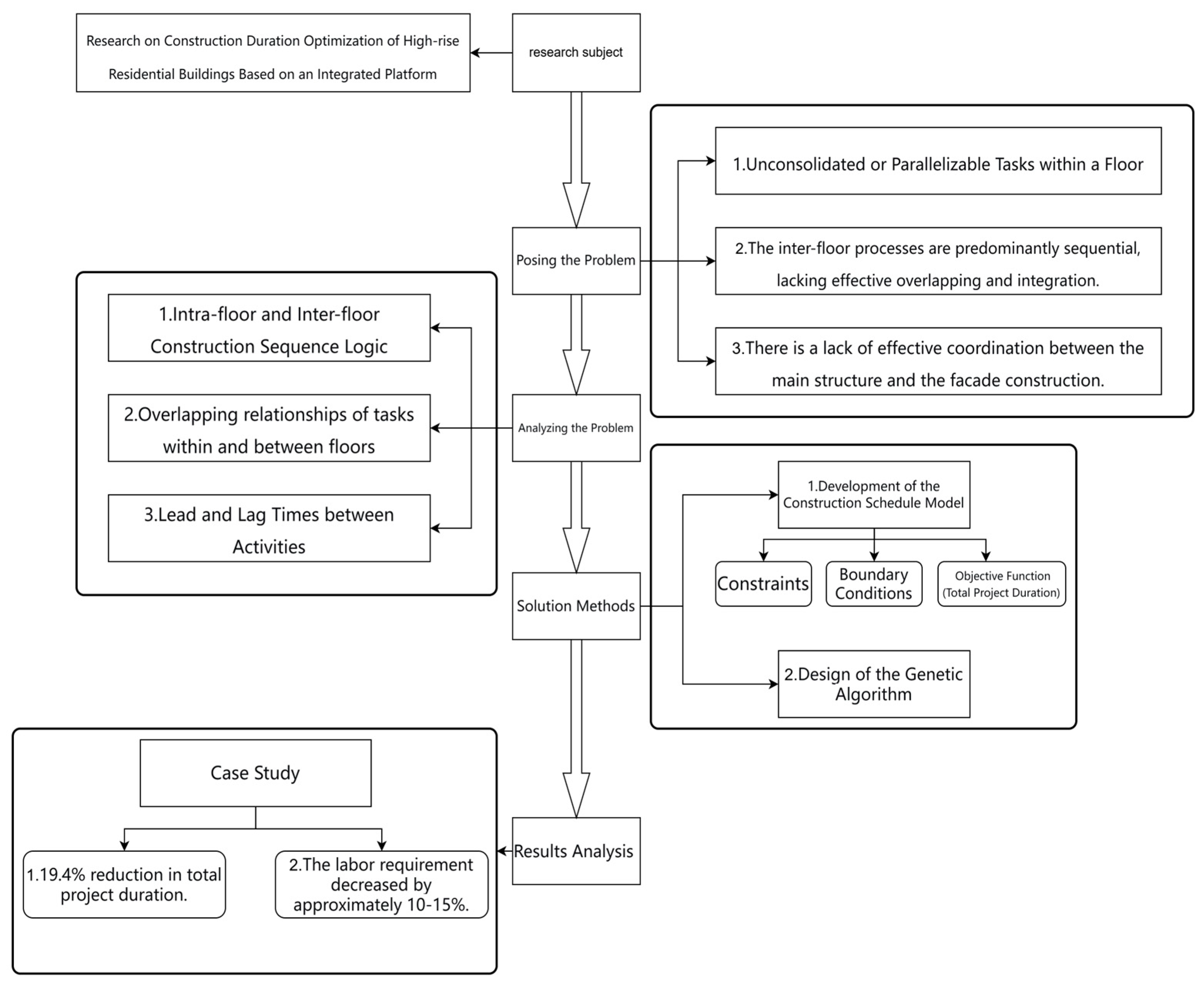

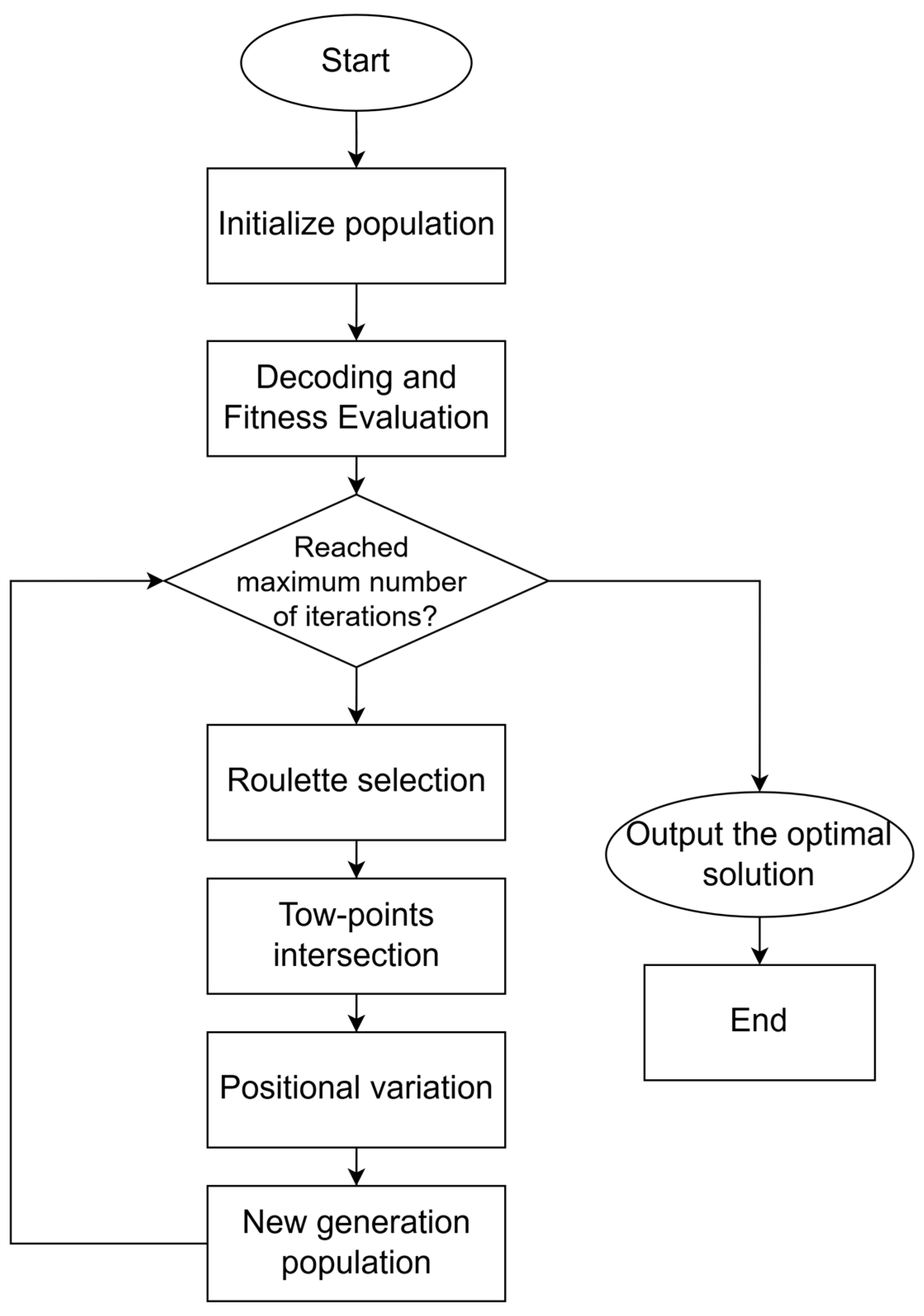

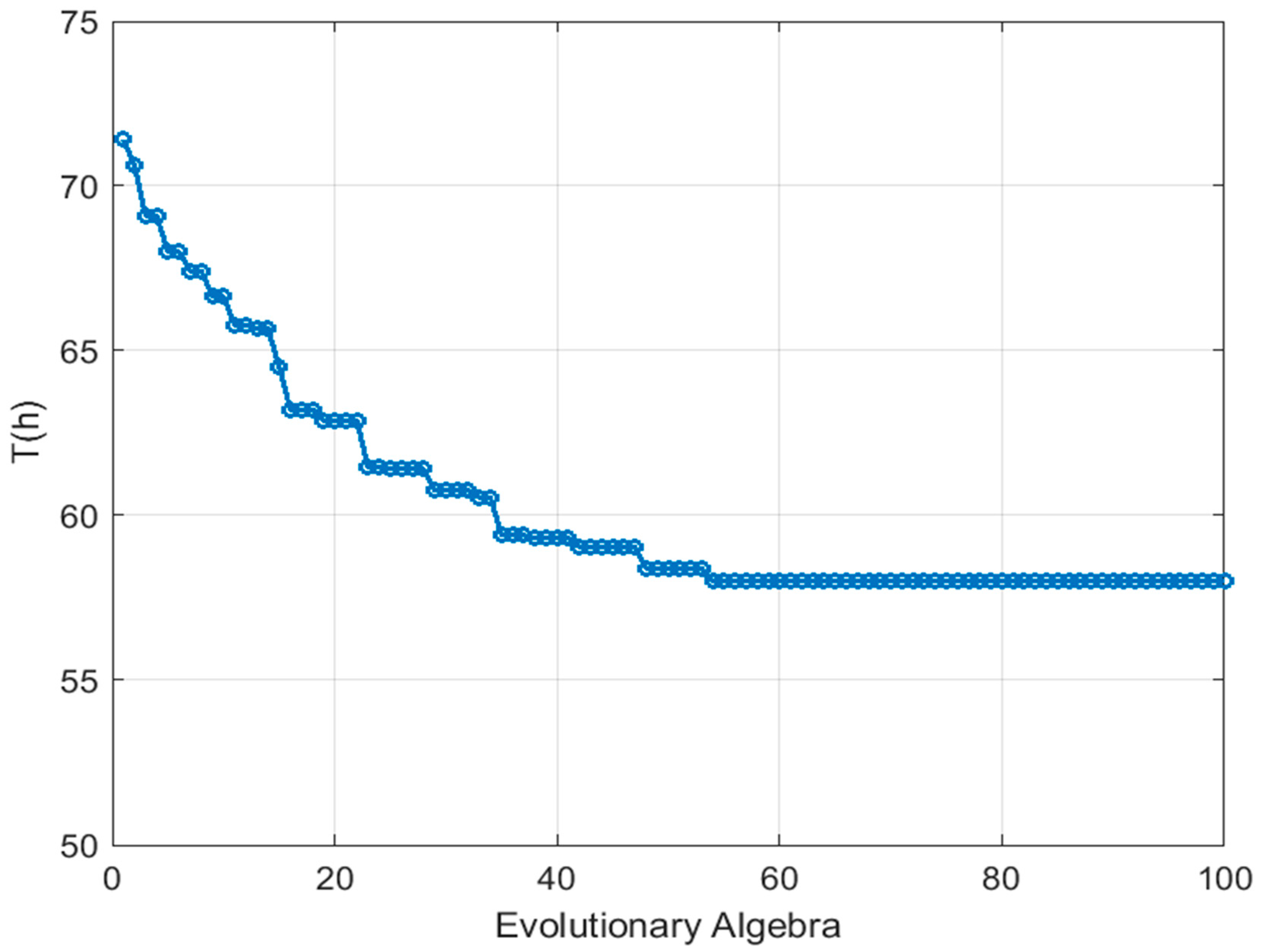

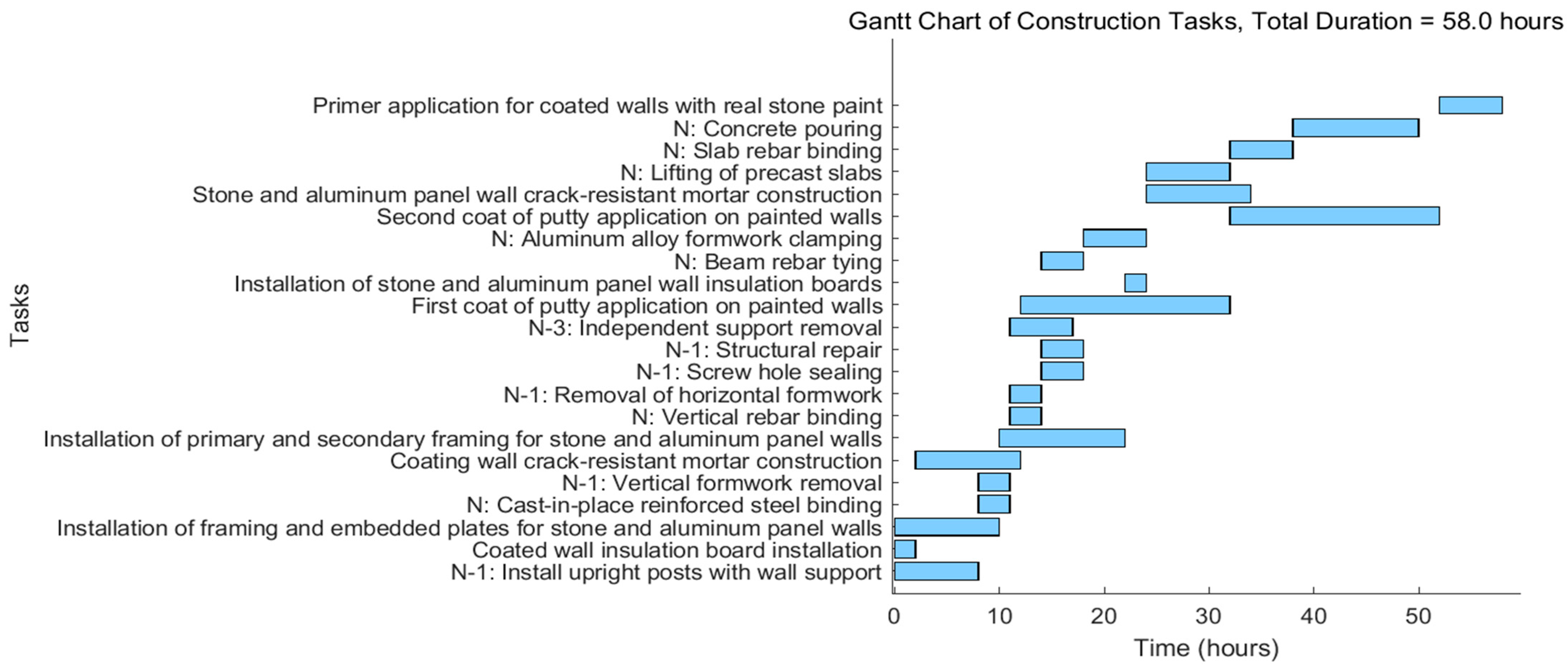

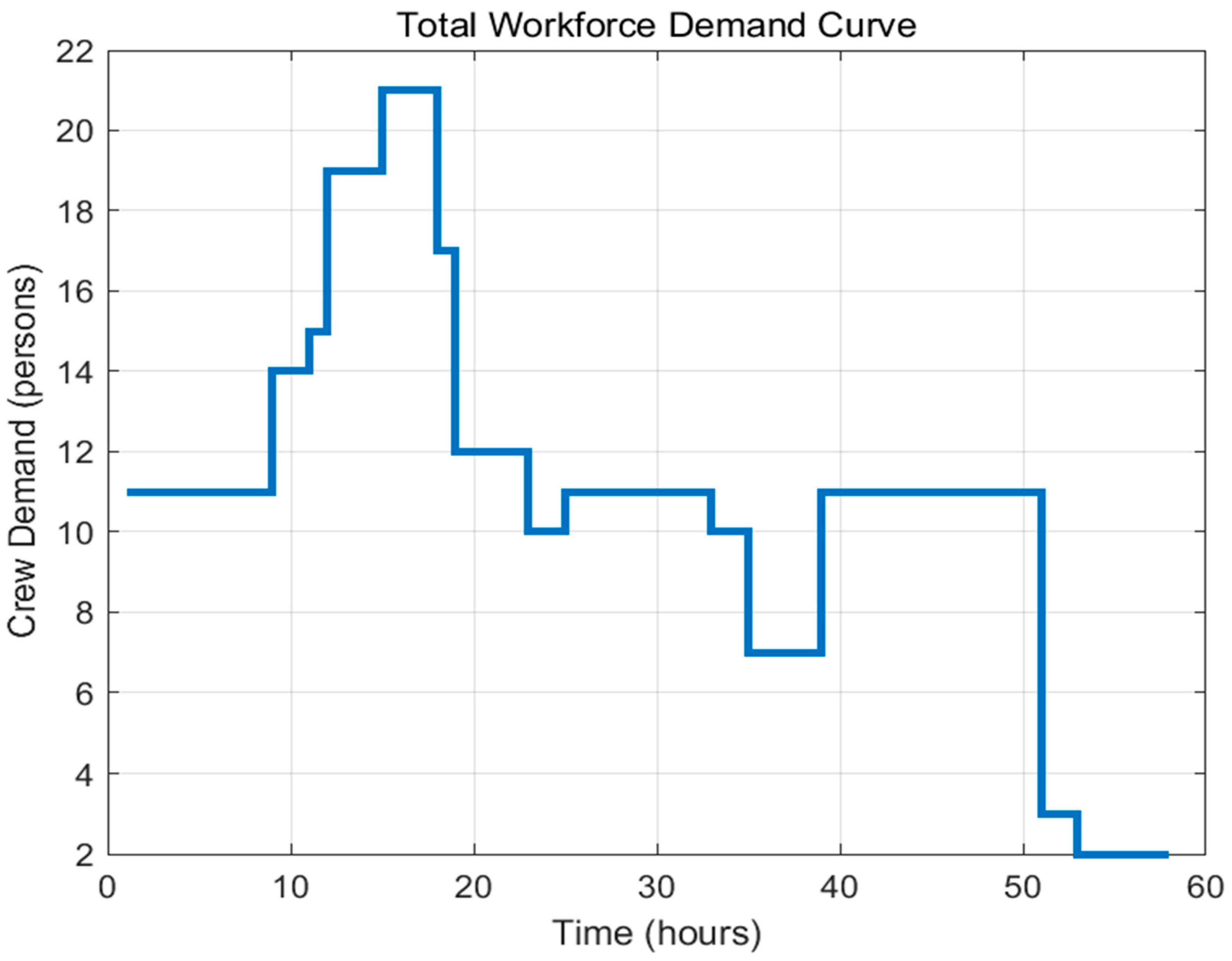

This study focuses on the construction duration of high-rise residential buildings using an integrated platform and investigates duration optimization issues for standard floors. A genetic-algorithm-based mathematical model is developed to optimize the construction schedule. By analyzing the logical relationships, overlapping conditions, and time-lag constraints among construction activities, an optimization objective function is formulated and solved to obtain the optimal schedule. The research aims to promote coordinated progress between structural and facade operations, enhance resource utilization efficiency of the integrated platform, and provide both theoretical support and practical guidance for construction schedule optimization in high-rise buildings.

1.2. Literature Review

In the field of construction project management, time optimization has long been a central research topic. As project scales grow and construction processes become more complex, traditional methods such as the Critical Path Method (CPM) and Linear Planning Method (LPM) are increasingly unable to meet optimal scheduling requirements under multiple constraints. ElSahly [

1] conducted a systematic review of time–cost optimization models in construction management, categorizing existing research into exact algorithms, approximate algorithms, and hybrid intelligent algorithms, and noting that exact algorithms suffer from low computational efficiency, whereas intelligent algorithms perform better in large-scale problems. Warne [

2] addressed large-scale time–cost trade-off problems using genetic algorithms, demonstrating the computational efficiency and accuracy of metaheuristic approaches in complex project networks and highlighting the advantages of GA for rapid optimization. Liu [

3] proposed a Discrete Symbiotic Organisms Search (DSOS) algorithm to solve large-scale TCTP problems, further illustrating that traditional mathematical methods struggle to deal with nonlinear relationships between project duration and cost. Overall, research on time optimization has evolved from deterministic models to stochastic/fuzzy models and, more recently, to intelligent optimization models, with optimization objectives shifting from simple duration minimization toward multi-objective balancing.

Among the major models and methods for duration optimization, the time–cost trade-off (TCT) problem is one of the earliest systematically studied. Warne developed a large-scale TCT model using genetic algorithms, achieving high-precision optimization across 630 activity variables and demonstrating the strong parallel computing capability and robustness of GA. Turkoglu and Arditi [

4] further proposed a multi-objective TCT model based on particle swarm optimization (PSO), integrating project duration, cost, resource fluctuations, and quality into a unified framework, which significantly advanced the development of multi-objective scheduling optimization. In recent years, multi-objective optimization has become increasingly comprehensive. For example, Yuan Zhenmin [

5] introduced a multi-objective optimization method for prefabricated buildings that combines ECRS techniques with intelligent simulation, simultaneously considering time, cost, quality, and CO

2 emissions, while addressing uncertainties such as material supply and weather conditions to achieve holistic trade-offs among performance objectives. Elbeltagi [

6] developed an integrated multi-objective optimization model encompassing time, cost, resources, and cash flow and applied particle swarm optimization (PSO) together with Pareto trade-off strategies to achieve unified scheduling under multiple decision criteria. These studies demonstrate that high-dimensional, multi-objective collaborative optimization has become a mainstream direction in large-scale engineering projects. Tran [

7] introduced a Multi-Objective Social Group Optimization (MOSGO) algorithm, generating time–cost trade-off curves through a multi-criteria decision-making mechanism to provide efficient solutions for complex projects. Huang [

8] developed an uncertainty-informed time–cost optimization model for high-rise buildings based on the NSGA-II algorithm, integrating Monte Carlo simulation with GA to enhance convergence accuracy under uncertain conditions. These studies collectively promote the TCT model toward a more intelligent direction involving multi-constraint and multi-factor coordination.

In complex construction systems, resource constraints are a critical factor limiting schedule optimization. Gonçalves [

9] proposed a Biased Random-Key Genetic Algorithm (BRKGA) to solve RCPSP problems and introduced a forward–backward improvement mechanism that significantly enhances search efficiency. Chen and Lee [

10] developed a hybrid genetic algorithm (HGA) for solving multi-mode resource-constrained multi-project scheduling problems (MMRCMPSPs), outperforming traditional GA approaches, particularly in highly complex projects. Damci [

11] further examined the problem from the perspective of resource leveling and systematically compared the performance of nine different resource-leveling objective functions in a real steel structure project. The study showed that different objective functions produce different resource histograms and that the optimal objective function is project-dependent. Therefore, contractors need to select an appropriate resource-leveling criterion based on the specific characteristics of the project. Abdel-Basset [

12] introduced a heuristic priority-rule scheduling model (PHR) for uncertain environments that can dynamically respond to fluctuations in resource availability. Xie et al. [

13] established an integrated scheduling model for multi-mode construction in prefabricated buildings, coordinating component supply and onsite installation to achieve joint optimization of resource constraints and duration minimization. These findings suggest that future research on time optimization should focus more on resource sharing, synchronized construction, and supply-chain coordination.

In studies on construction duration optimization based on intelligent algorithms, methods such as genetic algorithms (GAs), particle swarm optimization (PSO), and ant colony optimization (ACO) have been widely applied due to advancements in artificial intelligence. Among them, GA is most widely used owing to its strong global search capability and robust parameter performance. Yoonseok Shin [

14] proposed a hybrid model combining simulation and a genetic algorithm (GA) to achieve the optimal arrangement of temporary hoists in high-rise building construction. This approach overcomes the limitations of traditional formula-based methods, which struggle with multiple hoist combinations and the high time cost of pure simulation methods. In real projects, it produced results superior to conventional approaches, demonstrating the strong adaptability of GA in equipment scheduling. Fan Zesen [

15] applied GA to the automated layout of high-rise modular residential buildings, enabling the automatic generation of module units and core circulation arrangements. This study broadened the application boundary of GA in design-oriented architectural optimization and demonstrated its advantages in handling complex combinatorial search spaces. Faghihi [

16], using BIM, proposed a GA-based automatic generation method for construction sequences that ensures structural safety through stability constraints. Razavi-Alavi [

17] integrated GA with simulation frameworks to optimize site layout and scheduling simultaneously, achieving dual coordination of construction resources and onsite space. Xie [

18] developed a GA optimization model that accounts for resource constraints and component supply, significantly shortening the construction duration. Hu [

19] combined GA and PSO to form a hybrid GA–PSO model that outperforms single algorithms by 4–8%, demonstrating the superiority of hybrid intelligent approaches. Overall, GA has become one of the core algorithms in construction duration optimization.

In recent years, the integration of Building Information Modeling (BIM) with intelligent algorithms has provided data support and dynamic visualization capabilities for schedule optimization. Wefki [

20] constructed an integrated BIM–GA–5D simulation framework enabling automated schedule optimization and visual feedback. Yang [

21] proposed a BIM-based automated construction site layout planning method that leverages GA and PSO to reduce transportation time and cost. Essam [

22] further developed a BIM-based multi-objective optimization model to coordinate time, cost, and resource utilization. However, existing studies mainly focus on planar workflow scheduling or single-scenario optimization, with limited attention to spatiotemporal collaborative optimization involving multiple workspaces and parallelized tasks under integrated platform conditions. A dynamic optimization mechanism tailored for dual-platform vertical construction systems remains lacking.

As modular construction becomes a key direction of construction industrialization, its schedule optimization challenges have become increasingly prominent. Thai [

23] reviewed modular high-rise systems and connection technologies, highlighting their rapid construction and standardization advantages, which form the technical basis for duration optimization. Lee [

24] applied GA to schedule multi-module building projects, achieving integrated optimization of module production, transportation, and installation and significantly shortening overall duration. Yuan [

25] introduced fuzzy theory and a Hybrid Cooperative Evolutionary Algorithm (HCOEA) to enhance the robustness of prefabricated building scheduling under uncertainty. Xu [

26] achieved automated optimization of prefabricated component production using GA and IFC models, improving integration between offsite manufacturing and onsite assembly. These studies offer valuable insights for schedule optimization in industrialized construction.

Modern building project optimization objectives now extend beyond time alone. He Wei [

27] developed a multi-objective time–cost–energy consumption model and used principal component analysis to reveal correlations among the three factors. Wang [

28] built a four-objective model incorporating time, cost, quality, and carbon emissions and applied ACO to obtain Pareto-optimal solutions, enabling coordination between green construction and scheduling. Ekici [

29] and Faghihi [

30] explored multi-objective balance in sustainable high-rise construction from artificial intelligence and Pareto-front perspectives, providing theoretical foundations for future intelligent scheduling. Collectively, these studies illustrate that time optimization is evolving toward intelligent, low-carbon, and collaborative directions.

Compared with previous studies, this research does not limit its focus to scheduling optimization for a single task or a single platform. Wang Shuqiang et al. [

31] optimized the process path of a single-platform building integration platform to explore and study the best construction results in order to save construction time and improve efficiency, thereby minimizing construction time. Instead, it is based on a dual-platform integrated construction system and comprehensively analyzes the logical relationships, overlapping activities, and time-lag constraints between structural works and facade operations. A construction duration optimization model under multiple constraints is established. By introducing a genetic algorithm, this study enables global search and intelligent optimization of the construction process and develops an optimization model with project duration minimization as the objective function, thereby obtaining the optimal construction schedule.

The main innovations of this study are as follows:

(1) It breaks away from the traditional single-platform serial construction approach by treating structural and facade construction as a dynamic collaborative system. Through an analysis of their spatiotemporal relationships, this study achieves synchronized progress between the upper and lower platforms.

(2) It develops a multi-constraint optimization model that simultaneously considers logical constraints, resource constraints, platform load-bearing constraints, and other influencing factors, thus significantly enhancing the model’s practical applicability. It applies a genetic algorithm to obtain solutions, achieving global optimization and dynamic adjustment of the construction schedule, which greatly improves construction efficiency.

The results of the optimization model and simulation analysis show that, while shortening the construction duration, labor resource input is also effectively reduced, construction organization becomes more balanced and efficient, and platform utilization is significantly improved. This research not only fills the gap in previous studies regarding collaborative optimization for integrated platform operations but also provides a new technical pathway and theoretical foundation for intelligent scheduling and duration management in high-rise residential construction.