Fire-Resistant Steel Structures: Optimization Mathematical Model with Minimum Predicted Cost of Fire Protection Means

Abstract

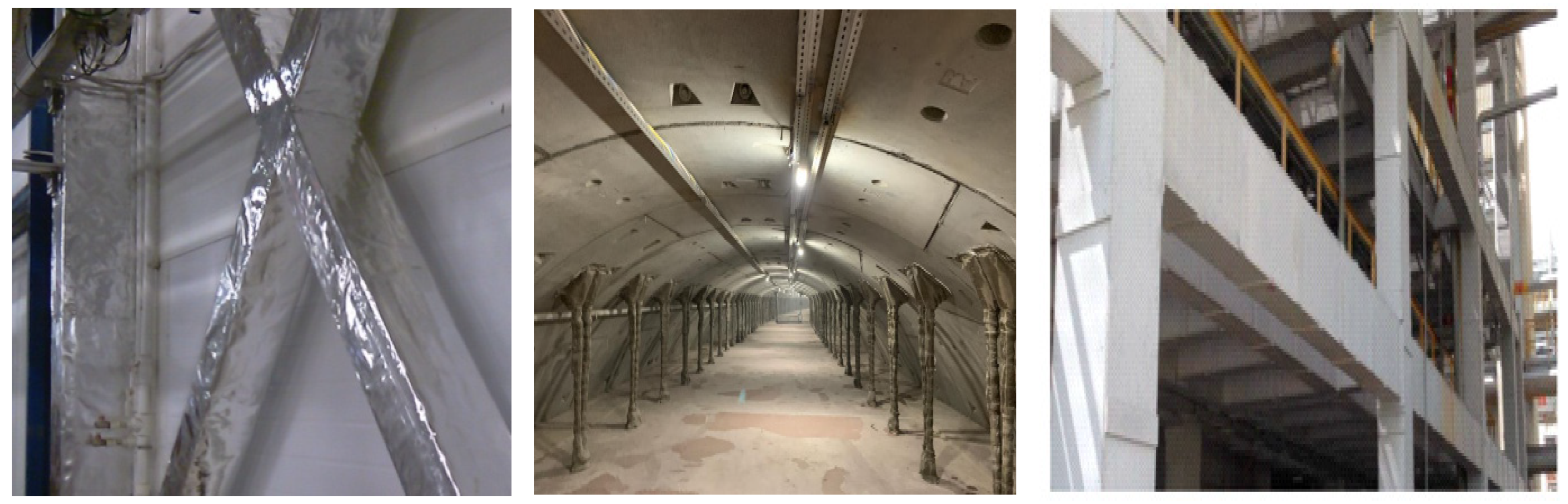

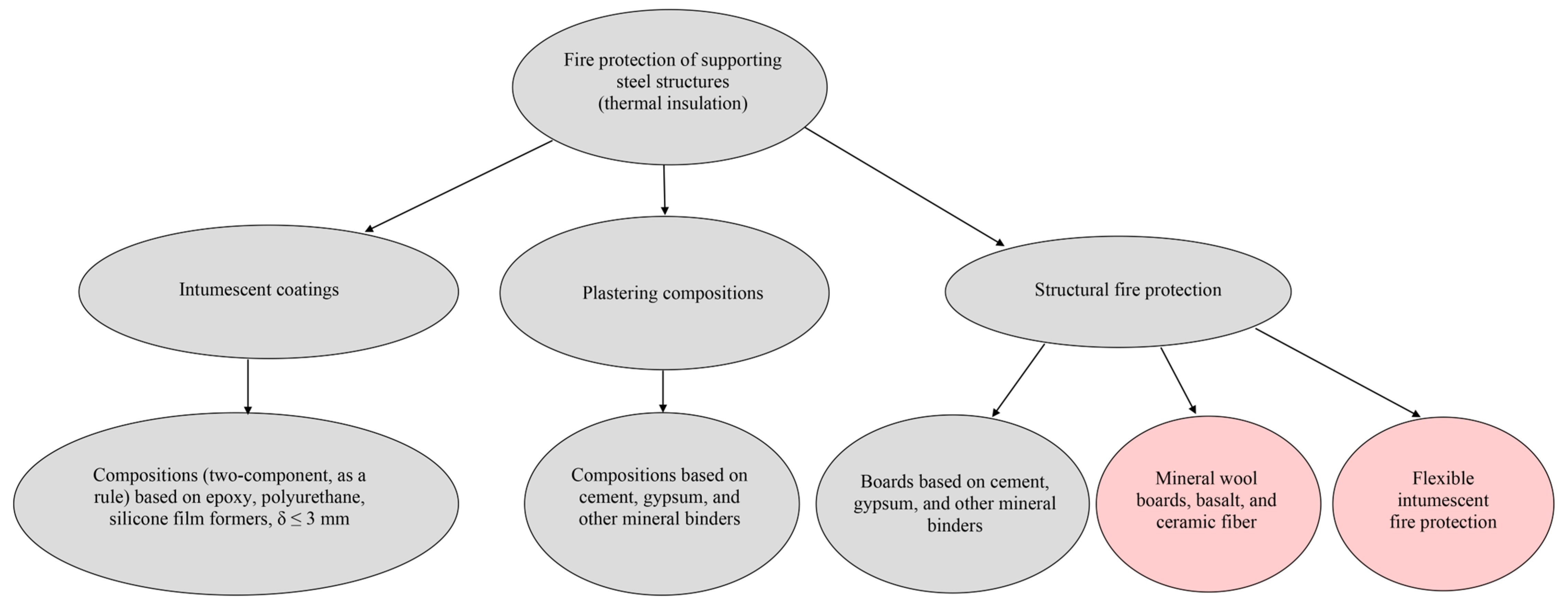

1. Introduction

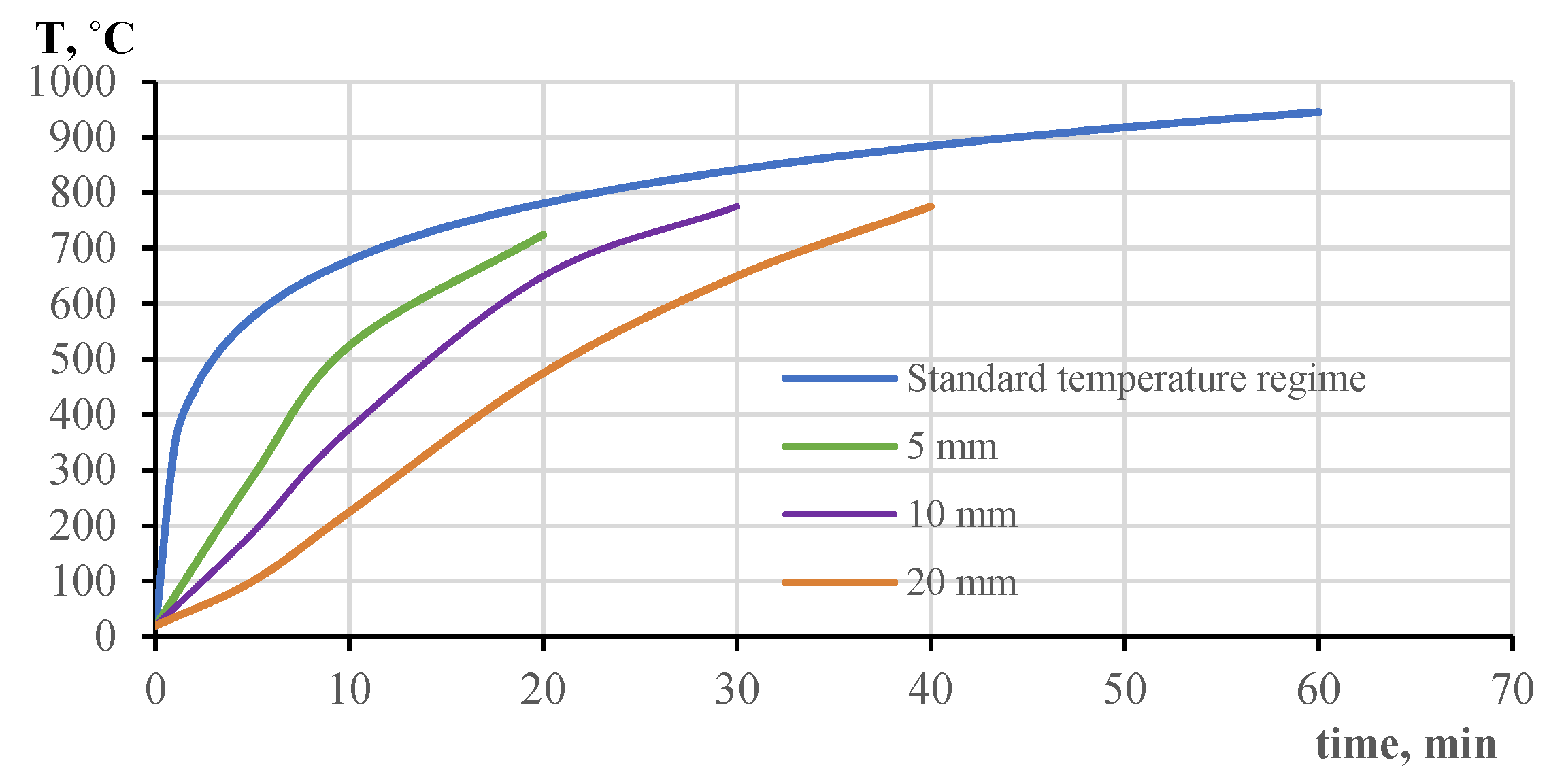

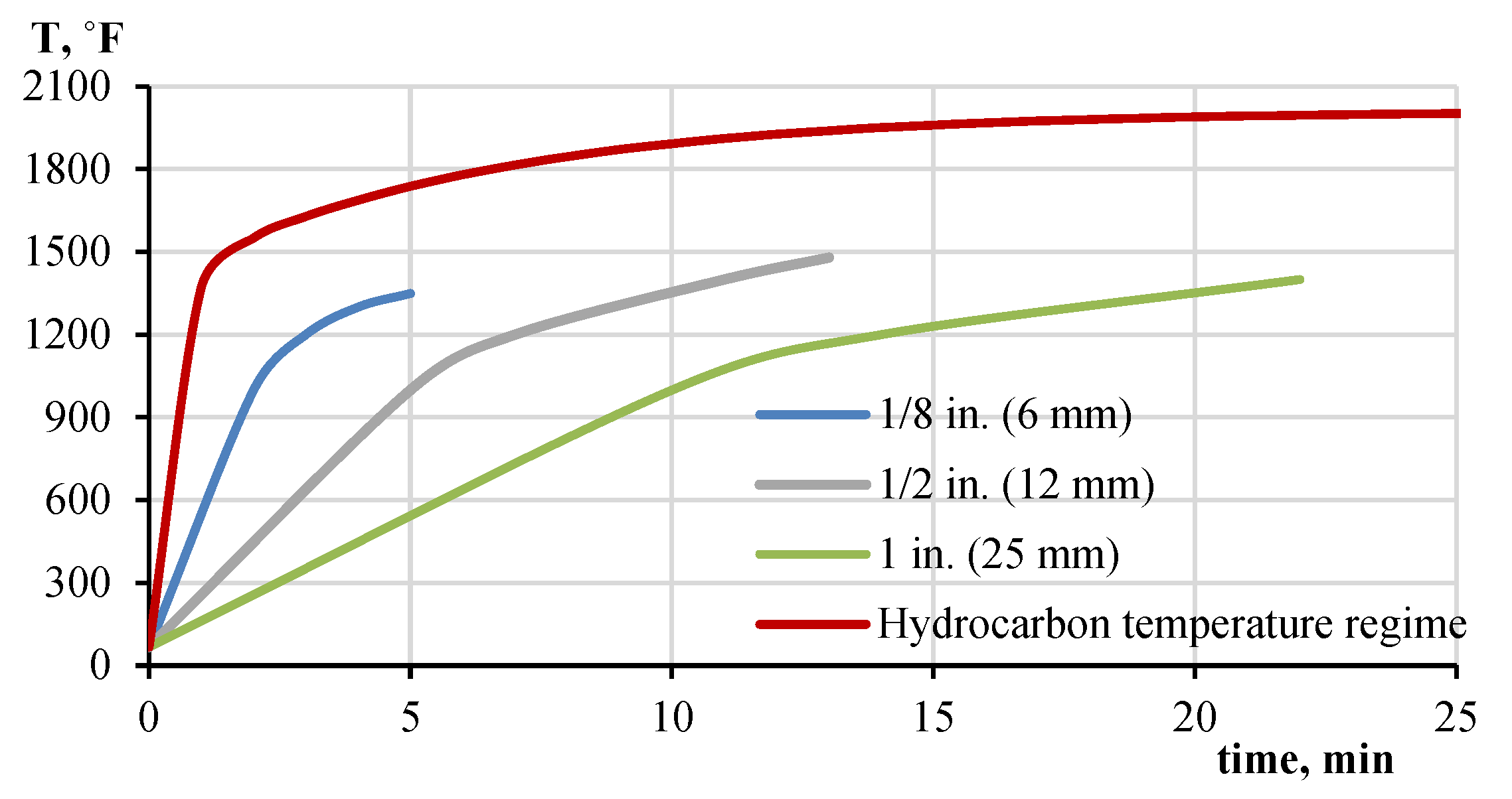

1.1. The Nominal Temperature—Time Curves and Fire Protection

1.2. Limit States of Structures and Predictive Model with Fire Protection

1.3. Review of Research on Predicting the Fire Resistance of Structures Under Different Fire Exposure

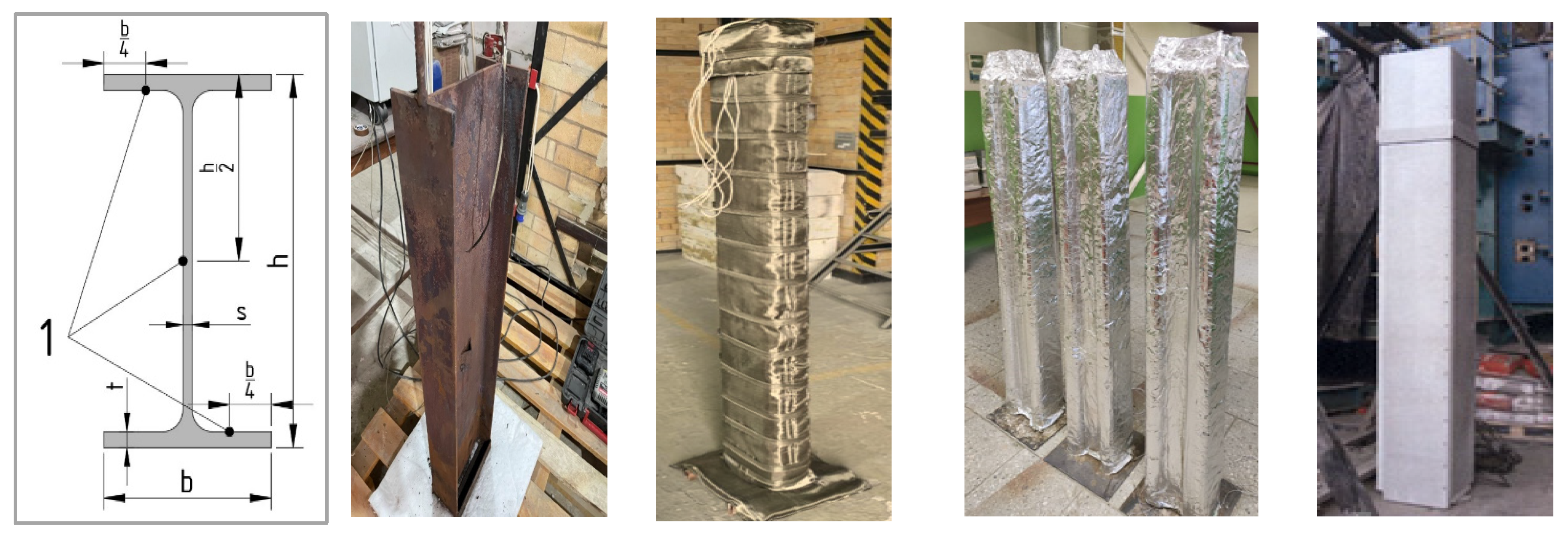

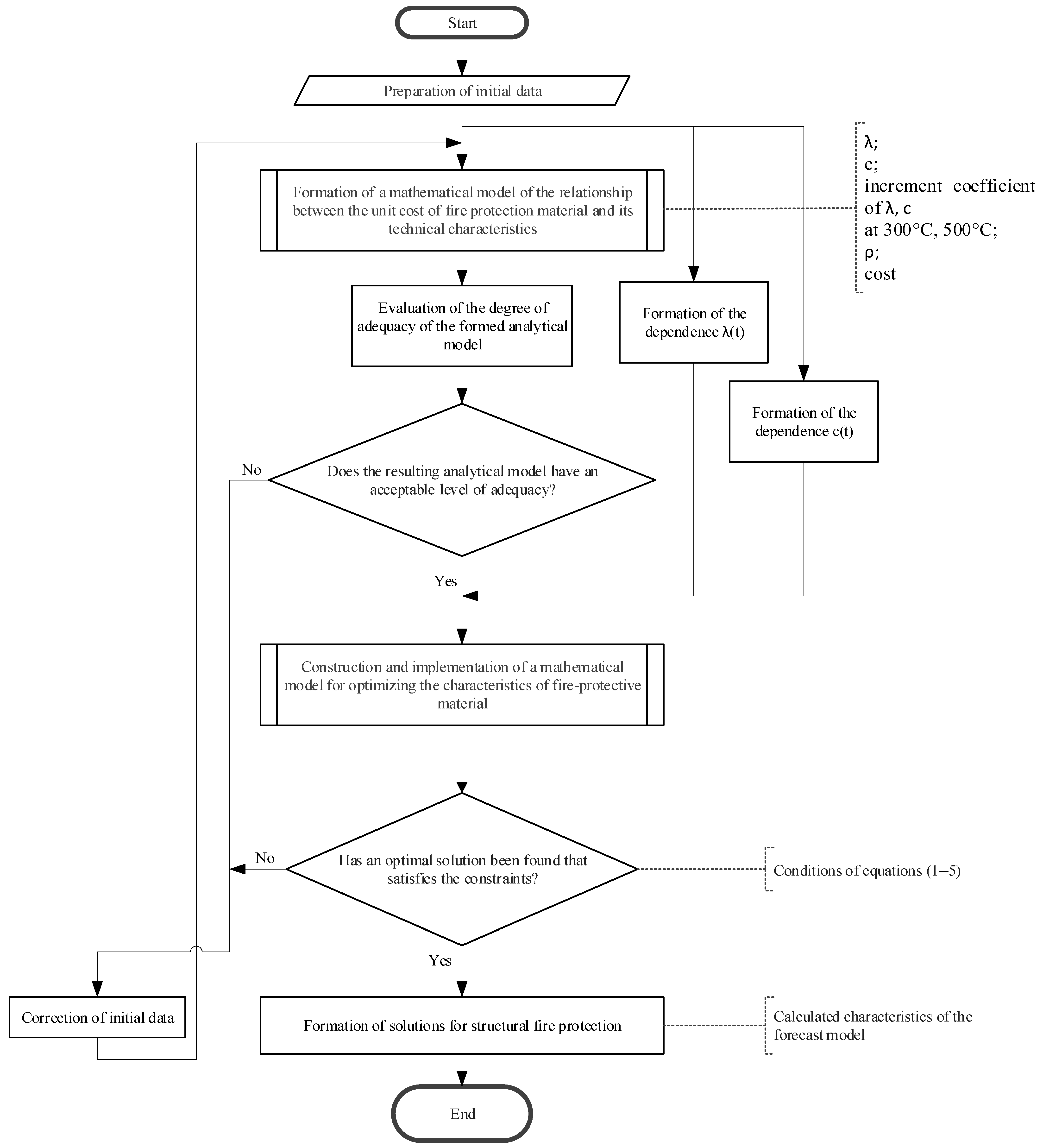

2. Materials and Methods

- -

- Modeling the development of a “real” fire scenario. Based on fire development scenarios, the predicted spread radius of flammable hydrocarbons and heat flux parameters are calculated; currently, field fire models are used for these purposes, though for external applications (fire development in open areas rather than indoors), certain assumptions must be made;

- -

- Solving the static problem for load-bearing structures, considering their thermal heating up to critical temperatures;

- -

- Ensuring the required fire resistance limit under design fire load conditions and calculating the necessary and sufficient amount of fire protection to maintain the structure’s fire resistance based on the loss of parameters established in the design documentation.

3. Discussion and Results

- −

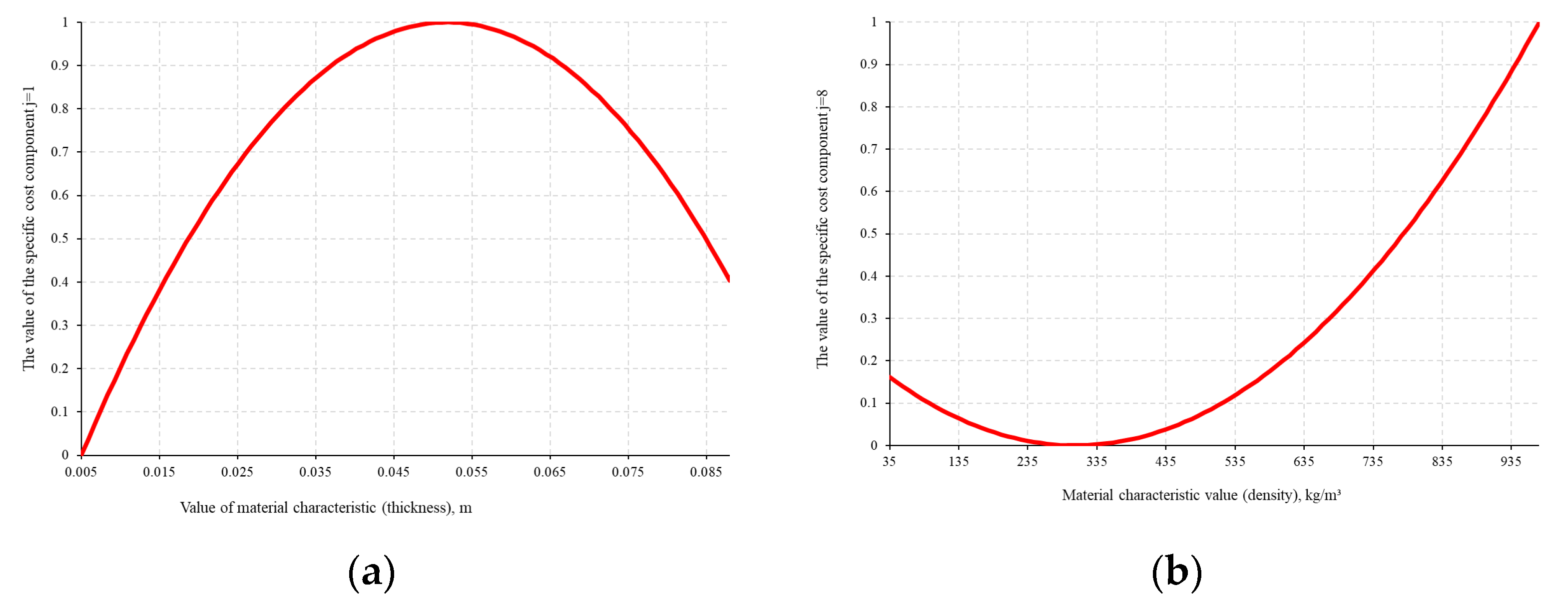

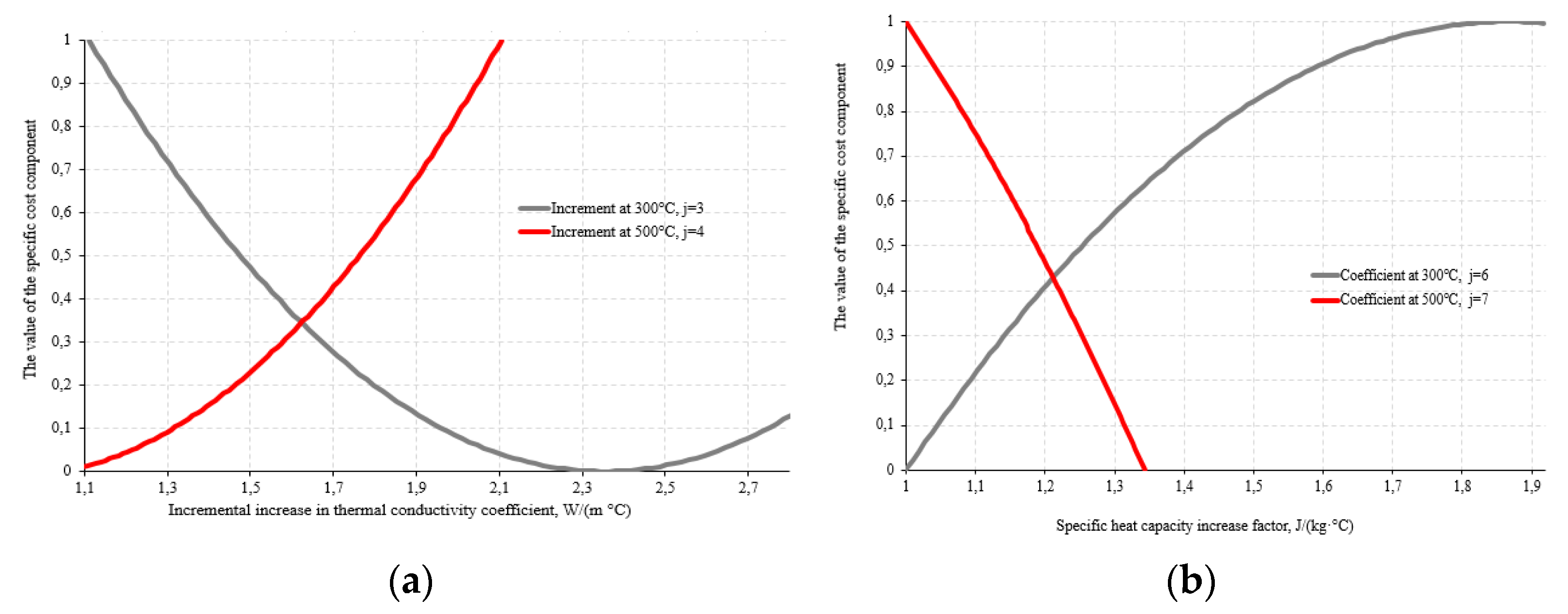

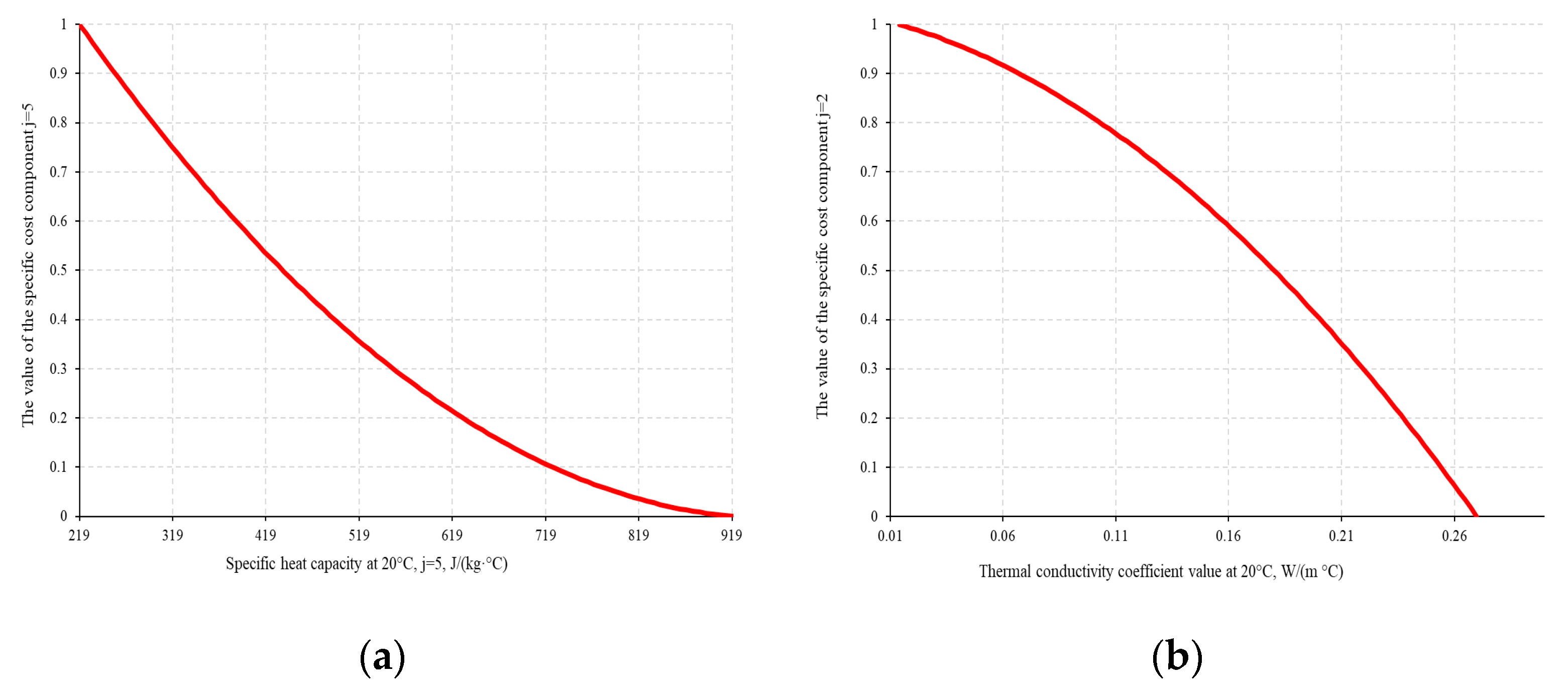

- : main (primary) technical characteristics describing the state of fireproofing material at the onset of fire, not directly describing changes in the material properties during fire development, and characterized by relatively high influence on the material’s specific cost;

- −

- : additional (secondary) technical characteristics of the material, directly describing changes in the fireproofing material properties during fire development, characterized by relatively low influence on the material’s specific cost.

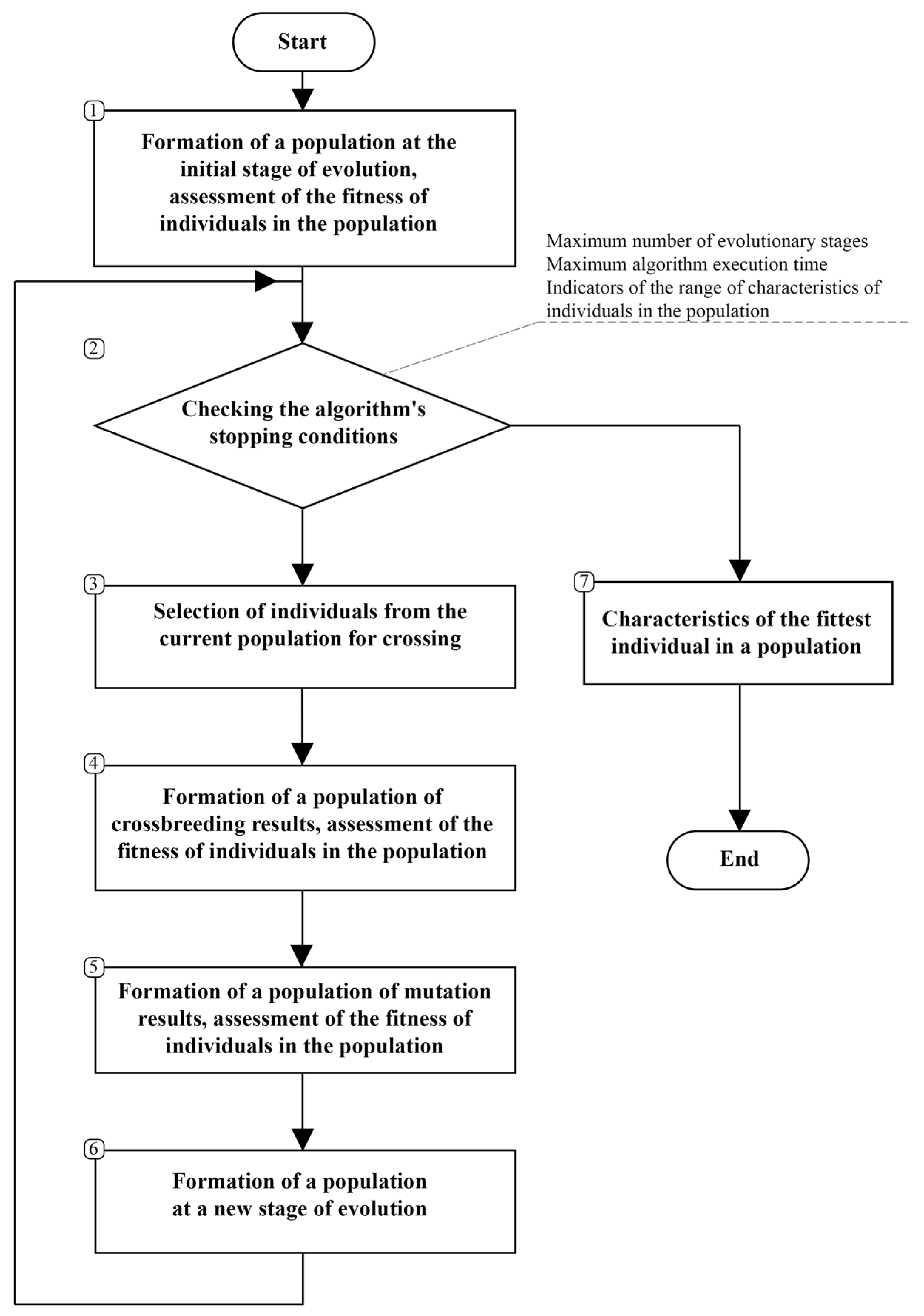

3.1. Genetic Algorithm Procedure

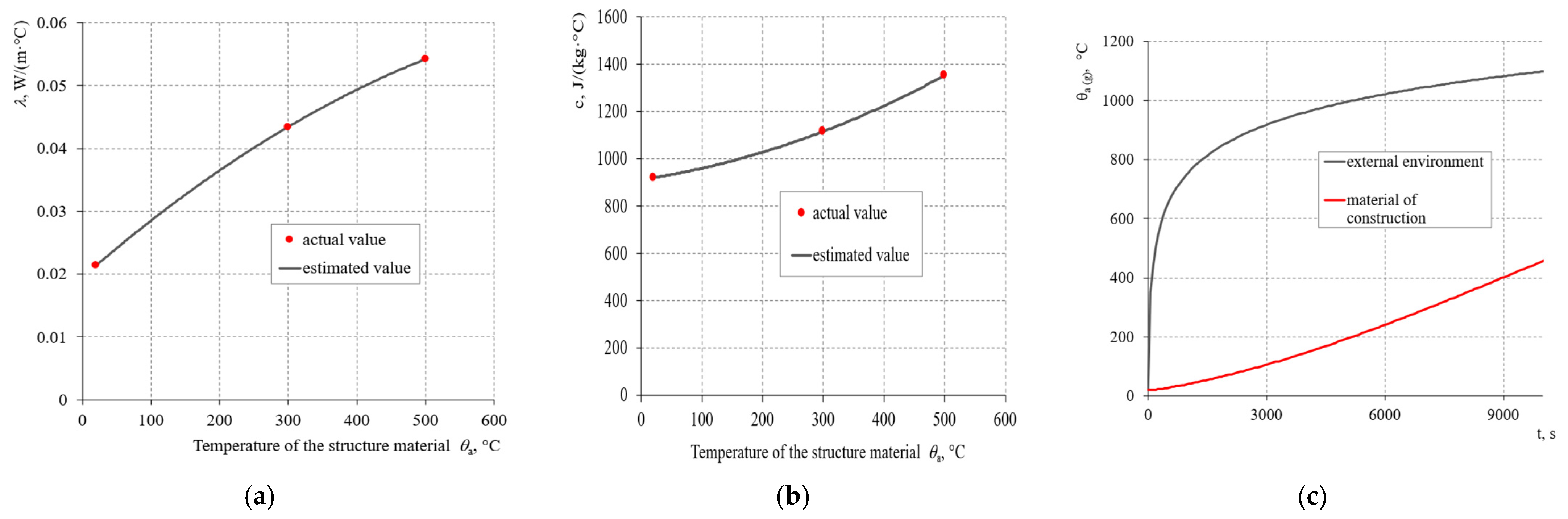

3.2. Implementation of the Model Using a Practical Example

- Geometric stability of the fire protection rod system during a fire (in the model, the temperature must not reach 500 °C for 180 min).

- The material density does not change during a fire.

- Maximum and minimum cost constraints for the materials in the sample: $80.00/m2 and $4.00/m2, respectively.

- The temperature on the unheated steel surface beneath the fire protection must not exceed 500 °C.

3.3. Model Validation

4. Limitations and Future Work

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ISO 834-1:1999/Amd 2:2021; Fire-Resistance Tests. Elements of Building Construction. Part 1: General Requirements. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. Available online: https://www.iso.org/ru/standard/81661.html (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Džolev, I.; Kekez-Baran, S.; Rašeta, A. Fire Resistance of Steel Beams with Intumescent Coating Exposed to Fire Using ANSYS and Machine Learning. Buildings 2025, 15, 2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassoune, M.; Kada, A.; Menadi, B.; Lamri, B.; Yessad, O.; Piloto, P.A.; Jiang, L. Performance of single and built-up I-shaped cold formed steel stud under double sided walls fire exposure. Eng. Struct. 2025, 335, 120392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1363-1:2020; Fire Resistance Tests—Part 1: General Requirements. Slovenski Inštitut za Standardizacijo: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2020. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/243adbdc-e0e0-43ac-a801-22c8e91e7f3c/en-1363-1-2020?srsltid=AfmBOookIsJU3EPvpbYwXaiZuu4oU2bhlu7zJS2dAHdgFgOOTTD04CvJ (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- UL 1709-2017; Standard for Safety Rapid Rise Fire Tests of Protection Materials for Structural Steel. Underwriters Laboratories Inc. (UL): Northbrook, IL, USA, 2017. Available online: https://docs.cntd.ru/document/550713257 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Gravit, M.; Dmitriev, I.; Shcheglov, N.; Radaev, A. Oil and Gas Structures: Forecasting the Fire Resistance of Steel Structures with Fire Protection under Hydrocarbon Fire Conditions. Fire 2024, 7, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOST R 53293-2009; Fire Hazard of Substances and Materials, Materials, Substances and Means. RUNORM: Moscow, Russia, 2009. Available online: https://runorm.com/catalog/102/828617 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- ASTM E119; Standard Test Methods for Fire Tests of Building Construction and Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.astm.org/e0119-00a.html (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- EN 1991-1-2; Eurocode 1: Actions on Structures—Part 1–2: General Actions—Actions on Structures Exposed to Fire. European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2002. Available online: https://www.phd.eng.br/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/en.1991.1.2.2002.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- BS EN 13381-4-2013; Test Methods for Determining the Contribution to the Fire Resistance of Structural Members—Part 4: Applied Passive Protection to Steel Members. European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. Available online: https://knowledge.bsigroup.com/products/test-methods-for-determining-the-contribution-to-the-fire-resistance-of-structural-members-applied-passive-protection-products-to-steel-members (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- ETAG 018-2013/Guideline for European Technical Approval of Fire Protective Products. Part 1: General. Available online: https://www.eota.eu/sites/default/files/uploads/ETAGs/etag-018-part-1-april-2013.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Pereira, D.; Fonseca, E.M.M.; Osório, M. Computational Analysis for the Evaluation of Fire Resistance in Constructive Wooden Elements with Protection. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolina, F.L.; Rodrigues, J.P.C. Temperature field of composite steel and concrete slabs in fire situation. Rev. IBRACON Estrut. Mater. 2024, 17, e17208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Gernay, T. Numerical analysis of full-scale structural fire tests on composite floor systems. Fire Saf. J. 2024, 146, 104182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodur, V.; Raut, N. A simplified approach for predicting fire resistance of reinforced concrete columns under biaxial bending. Eng. Struct. 2012, 41, 428–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, A. The Challenges of Predicting Structural Performance in Fires. Fire Saf. Sci. 2008, 9, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatachari, S.; Kodur, V.K.R. Modeling parameters for predicting the fire-induced progressive collapse in steel framed buildings. Resilient Cities Struct. 2023, 2, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R.K.; Gernay, T.; Van Coile, R. Cost-optimization based target reliabilities for design of structures exposed to fire. Resilient Cities Struct. 2024, 3, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, H.A.; Al-Juboori, O.A.; Mahjoob, A.M.R. Genetic Algorithms in Construction Project Management: A Review. Solid State Technol. 2021, 64, 5193–5213. [Google Scholar]

- Srimathi, K.R.; Padmarekha, A.; Anandh, K.S. Automated construction schedule optimisation using genetic algorithm. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 2023, 24, 3521–3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benaddi, F.Z.; Boukhattem, L.; Tabares-Velasco, P.C. Multi-objective optimization of building envelope components based on economic, environmental, and thermal comfort criteria. Energy Build. 2024, 305, 113909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Pan, H.; Luo, Z.; Liu, C.; Huang, H. Multi-objective optimization of residential building energy consumption, daylighting, and thermal comfort based on BO-XGBoost-NSGA-II. Build. Environ. 2024, 254, 111386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olekhnovich, Y.A.; Radaev, A.E. Justification of the combination of standard values of characteristics of materials of layers in the enclosing structure based on quadratic optimization. Bull. MGSU 2025, 20, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olekhnovich, Y.A. Methodology for Substantiating the Characteristics of Enclosing Structures of Residential Buildings Based on Energy Efficiency Criteria. Diss. Candidate of Engineering Sciences, SPbPU, St. Petersburg. 2025. Available online: https://www.spbstu.ru/dsb/09bb-thesis.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Memarzadeh, A.; Shahmansouri, A.; Nematzadeh, M.; Gholampour, A. A review on fire resistance of steel-concrete composite slim-floor beams. Steel Compos. Struct. 2021, 40, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memarzadeh, A.; Nazari, A.; Sabetifar, H.; Nematzadeh, M. Advanced predictive modeling for masonry walls: A comparative study of six AI models and existing empirical formulas. Results Eng. 2025, 28, 107634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Optimization Method of Building Structure Design Based on Genetic Algorithm. The 5th International Conference on Multi-modal Information Analytics (MMIA). Procedia Comput. Sci. 2025, 262, 1344–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavan, F.; Maalek, R. Reliability-Constrained Structural Design Optimization Using Visual Programming in Building Information Modeling (BIM) Projects. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SP 20.13330; Loads and Impacts. Ministry of Construction Industry, Housing and Utilities Sector of the Russian Federation: Moscow, Russia, 2016.

- SP 16.13330.2017; Steel Structures. Ministry of Construction Industry, Housing and Utilities Sector of the Russian Federation: Moscow, Russia, 2017.

- EN 1993-1-2:2005; Eurocode 3: Design of Steel Structures. Part 1–2: General Rules—Structural Fire Design. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2005. Available online: https://www.phd.eng.br/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/en.1993.1.2.2005.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Barthelemy, B.; Kruppa, J. Fire Resistance of Building Structures—M.: Stroyizdat, 1985. 216p. Available online: https://fireman.club/literature/ognestojkost-stroitelnyh-konstrukczij-1985/ (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- National Standard of Russia GOST R 53295-2009 Fire Retardant Compositions for Steel Constructions. General Requirement. Method for Determining Fire Retardant Efficiency. Available online: https://docs.cntd.ru/document/1200071913 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Alekseytsev, A.V.; Kurchenko, N.S. Searching the rational parameters of bar steel structures based on adaptive evolutionary model. Struct. Mech. Eng. Constr. Build. 2011, 3, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Shadrina, N.I.; Berman, N.D. Solving Optimization Problems in Microsoft Excel 2010: A Tutorial; Vikhtenko, E.M., Ed.; Publishing House of Pacific State University: Khabarovsk, Russia, 2016; 101p, ISBN 978-5-7389-1886-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bazukova, E.; Vankov, Y.; Gaponenko, S.; Smirnov, N. Study of thermal conductivity coefficient of basalt fiber insulation at various temperature conditions. Vestn. IGEU 2021, 4, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravit, M.V.; Nedryshkin, O.V.; Petrochenko, M.V. Structural Methods for Increasing the Fire Resistance of Load-Bearing Steel Structures [Electronic Resource]; study guide; Peter the Great St. Petersburg Polytechnic University, Civil Engineering Institute, Department of “Construction of Unique Buildings and Structures”: St. Petersburg, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsel, A.A. Optimization Methods; Mitsel, A.A., Shelestov, A.A., Romanenko, V.V., Eds.; Part 2: Tutorial; Publishing House of Tomsk. State University of Control Systems and Radioelectronics: Tomsk, Russia, 2022; 350p. [Google Scholar]

- State Standard 23630.1-79; Plastics Method for the Determination of Thermal Capacity. USSR State Committee for Standards: Moscow, Russia, 1979. Available online: https://docs.cntd.ru/document/1200018701 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Technical Insulation Catalog of ROCKWOOL Group. Available online: https://rwl.ru/files/rw/documents/katalog-tekhnicheskoy-izolyatsii%20-%2020227.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Motsa, S.M.; Stavroulakis, G.Ε.; Drosopoulo, G.A. A data-driven, machine learning scheme used to predict the structural response of masonry arches. Eng. Struct. 2023, 296, 116912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematzadeh, M.; Nazari, A.; Tayebi, M. Post-fire impact behavior and durability of steel fiber-reinforced concrete containing blended cement–zeolite and recycled nylon granules as partial aggregate replacement. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2021, 22, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaeicherati, F.; Arabkhazaeli, A.; Memarzadeh, A.; Naghipour, M.; Vahedi, A.; Nematzadeh, M. Experimental study of post-fire bond behavior of concrete-filled stiffened steel tubes: A crucial aspect for composite structures. Structures 2024, 62, 106203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Code of Practice 477.1325800.2020 Highrise Buildings and Complexes. Fire Safety Requirements. Available online: https://docs.cntd.ru/document/564612859 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

| Index | Name of the Accounted Technical Characteristic of the Fireproofing Material | Unit | Notation |

|---|---|---|---|

| j | - | MUx j | |

| 1 | Thickness of fire protection material | m | |

| 2 | λ at 20 °C | W/(m·°K) | |

| 3 | Increment coefficient of λ20 to λ300 | - | |

| 4 | Increment coefficient of λ300 to λ500 | - | |

| 5 | Specific heat capacity at 20 °C | J/(kg·°K) | |

| 6 | Increment coefficient of C00 at 300 °C to C11 at 20 °C | - | |

| 7 | Increment coefficient of specific heat capacity at 300 °C relative to 500 °C | - | |

| 8 | Material density | kg/m3 |

| No. | Name of Model Structure Parameter/Index/Input Data Element | Unit | Notation/ Expression |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Quantities: | ||

| 1.1 | Number of technical characteristics of fireproofing material | unit | |

| 1.2 | Main (additional) characteristics determining the main (additional) component of specific cost (1) | unit | |

| 1.3 | Parameters for the predictive model for the main (additional) component of specific cost (2) | unit | |

| 1.4 | Number of fireproofing material instances | unit | |

| 2 | Indices and Sets: | ||

| 2.1 | Index of fireproofing material instance | - | |

| 2.2 | Index of fireproofing material technical characteristic | - | |

| 2.3 | Index of the main (additional) technical characteristic of fireproofing material (3) | - | |

| 2.4 | Index of the predictive model parameter for the main (additional) cost component | - | |

| 2.5 | Index of time moment (4) | - | |

| 2.6 | Set of indices for the main technical characteristics of the material | - | |

| 2.7 | Set of indices for the additional technical characteristics of the material | - | |

| 3 | Input Data | ||

| 3.1 | General Input Data | ||

| 3.1.1 | Share of the main component in the total specific cost of the material | - | |

| 3.1.2 | Cross-section coefficient of the insulated structure | m−1 | |

| 3.1.3 | Specific heat capacity of the structural material | J/(kg·°K) | |

| 3.1.4 | Density of the structural material | kg/m3 | |

| 3.1.5 | S-mode exposure duration | s | |

| 3.1.6 | Time interval duration | s | |

| 3.1.7 | Maximum allowable temperature for the structural material | m−1 | |

| 3.1.8 | Reference temperature for the approximation curve (index 0) | °C | |

| 3.1.9 | Reference temperature for the approximation curve (index 1) | °C | |

| 3.1.10 | Reference temperature for the approximation curve (index 2) | °C | |

| 3.2 | Input Data for Each Fireproofing Material Variant (index i = 1, 2, …, m) | ||

| 3.2.1 | Material name | - | - |

| 3.2.2 | Actual specific cost value | CU/m2 | |

| 3.3 | Input Data for Each Technical Characteristic (index j = 1, 2, …, n) per Material Variant (index i = 1, 2, …, m) | ||

| 3.3.1 | Value of the technical characteristic | MUx j | |

| 4 | Unknown Variables | ||

| 4.1 | Variables considered for each technical characteristic with index j (j = 1, 2, …, n) | ||

| 4.1.1 | Value of the technical characteristic | MUx j |

| No. | Name of Model Structure Parameter/Index/Input Data Element | Unit | Expression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Calculated characteristics for each technical characteristic with index j (j = 1, 2, …, n) j (j = 1, 2, …, n) | |||||||

| 1.1 | Structurally permissible limit value of the characteristic | minimum | MUx j | |||||

| 1.2 | maximum | MUx j | ||||||

| 2.1 | Calculated characteristics for each main (additional) technical characteristic with index | |||||||

| 2.1.1 | Element of the main matrix of the equation system for determining the predictive model parameters, corresponding to row index and column index (1) | - | ||||||

| 2.1.2 | Element of the partial matrix of the equation system for determining the predictive model parameter with index , corresponding to row index and column index (2) | - | ||||||

| 2.1.3 | Main matrix of the equation system for determining the predictive model parameters (3) | - | ||||||

| 2.2 | Calculated characteristics for each predictive model parameter of the main (additional) specific cost component with index | |||||||

| 2.2.1 | Partial matrix of the equation system for determining the predictive model parameters (4) | - | ||||||

| 2.2.2 | Predictive model parameter defining the proportionality between the specific cost value and the technical characteristic value | var. (5) | ||||||

| 3 | Calculated characteristics for each pair of material technical characteristics with indices and | |||||||

| 3.1 | Maximum allowable conditional characteristic value | minimum | MUx j | |||||

| 3.2 | maximum | MUx j | ||||||

| 4 | Calculated characteristics for each fireproofing material variant with index i (i = 1, 2, …, m) | |||||||

| 4.1 | Predicted specific cost value | Main component | CU/m2 | |||||

| 4.2 | Additional component | CU/m2 | ||||||

| 4.3 | Predicted value of the main (additional) specific cost component | CU/m2 | ||||||

| 4.4 | Predicted specific cost value | CU/m2 | ||||||

| 5 | Calculated characteristics for each time moment of thermal exposure with index (6) | |||||||

| 5.1 | Time factor value | s | ||||||

| 5.2 | Ambient temperature parameter at time moment | Current | °C | |||||

| 5.3 | Next | °C | ||||||

| 5.4 | Ambient temperature change | °C | ||||||

| 5.5 | Structural material temperature value | °C | ||||||

| 5.6 | Thermal conductivity coefficient for the fireproofing material (7) | W/(m·°K) | ||||||

| 5.7 | Specific heat capacity for the fireproofing material (8) | J/(kg·°K) | ||||||

| 5.8 | Additional calculation parameter value | - | ||||||

| 5.9 | Structural material temperature change | °C | ||||||

| 6 | Generalized Calculated Characteristics of the Model | |||||||

| 6.1 | Actual value of the main (additional) specific cost of the fireproofing material | min | CU/m2 | |||||

| 6.2 | max | CU/m2 | ||||||

| 6.3 | Predicted value of the main (additional) specific cost of the fireproofing material | min | CU/m2 | |||||

| 6.4 | max | CU/m2 | ||||||

| 6.5 | Calculated coefficient of determination (R2) for the predictive model of the main (additional) specific cost of fireproofing material | - | ||||||

| 6.6 | Reference point ordinate value for the thermal conductivity approximation curve | 0 | W/(m·°K) | |||||

| 6.7 | 1 | W/(m·°K) | ||||||

| 6.8 | 2 | W/(m·°K) | ||||||

| 6.9 | Reference point ordinate value for the thermal conductivity approximation curve | 0 | W/(m·°K) | |||||

| 6.10 | 1 | W/(m·°K2) | ||||||

| 6.11 | 2 | W/(m·°K3) | ||||||

| 6.12 | Reference point ordinate value for the specific heat capacity approximation curve | 0 | J/(kg·°K) | |||||

| 6.13 | 1 | J/(kg·°K2) | ||||||

| 6.14 | 2 | J/(kg·°K3) | ||||||

| 6.15 | Reference point ordinate value for the C approximation curve | 0 | J/(kg·°K) | |||||

| 6.16 | 1 | J/(kg·°K2) | ||||||

| 6.17 | 2 | J/(kg·°K3) | ||||||

| 6.18 | Number of calculated time moments for thermal exposure | units | ||||||

| 6.19 | Predicted specific cost of the material | CU/m2 | ||||||

| T, °C | 25 | 100 | 200 | 300 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| λ, W/K·m | 0.17/0.257 * | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.11 |

| C, J/kg·m | 750/732 ** | 800/1068 ** | 815/1219 ** | 830/1164 **, 1216 *** |

| T, °C | Thermal Conductivity, λ, W/m∙K at Density, ρ | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ρ = 80 kg/m3 | ρ = 100 kg/m3 | ρ = 120 kg/m3 | |

| 50 | 0.0242 | 0.0217 | 0.0209 |

| 100 | 0.0277 | 0.0263 | 0.0246 |

| 200 | 0.0374 | 0.0345 | 0.0329 |

| 300 | 0.0488 | 0.0526 | 0.0464 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gravit, M.; Radaev, A.; Shcheglov, N.; Konstantinova, N.; Tsepova, A. Fire-Resistant Steel Structures: Optimization Mathematical Model with Minimum Predicted Cost of Fire Protection Means. Buildings 2026, 16, 215. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010215

Gravit M, Radaev A, Shcheglov N, Konstantinova N, Tsepova A. Fire-Resistant Steel Structures: Optimization Mathematical Model with Minimum Predicted Cost of Fire Protection Means. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):215. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010215

Chicago/Turabian StyleGravit, Marina, Anton Radaev, Nikita Shcheglov, Natalia Konstantinova, and Alla Tsepova. 2026. "Fire-Resistant Steel Structures: Optimization Mathematical Model with Minimum Predicted Cost of Fire Protection Means" Buildings 16, no. 1: 215. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010215

APA StyleGravit, M., Radaev, A., Shcheglov, N., Konstantinova, N., & Tsepova, A. (2026). Fire-Resistant Steel Structures: Optimization Mathematical Model with Minimum Predicted Cost of Fire Protection Means. Buildings, 16(1), 215. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010215