A Moment-Rotation Model of Semi-Rigid Steel Structure Joints with Bolted Connection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Finite Element Model

2.1. Geometric Model

2.2. Finite Element Modeling Procedure

2.3. Finite Element Model Validation

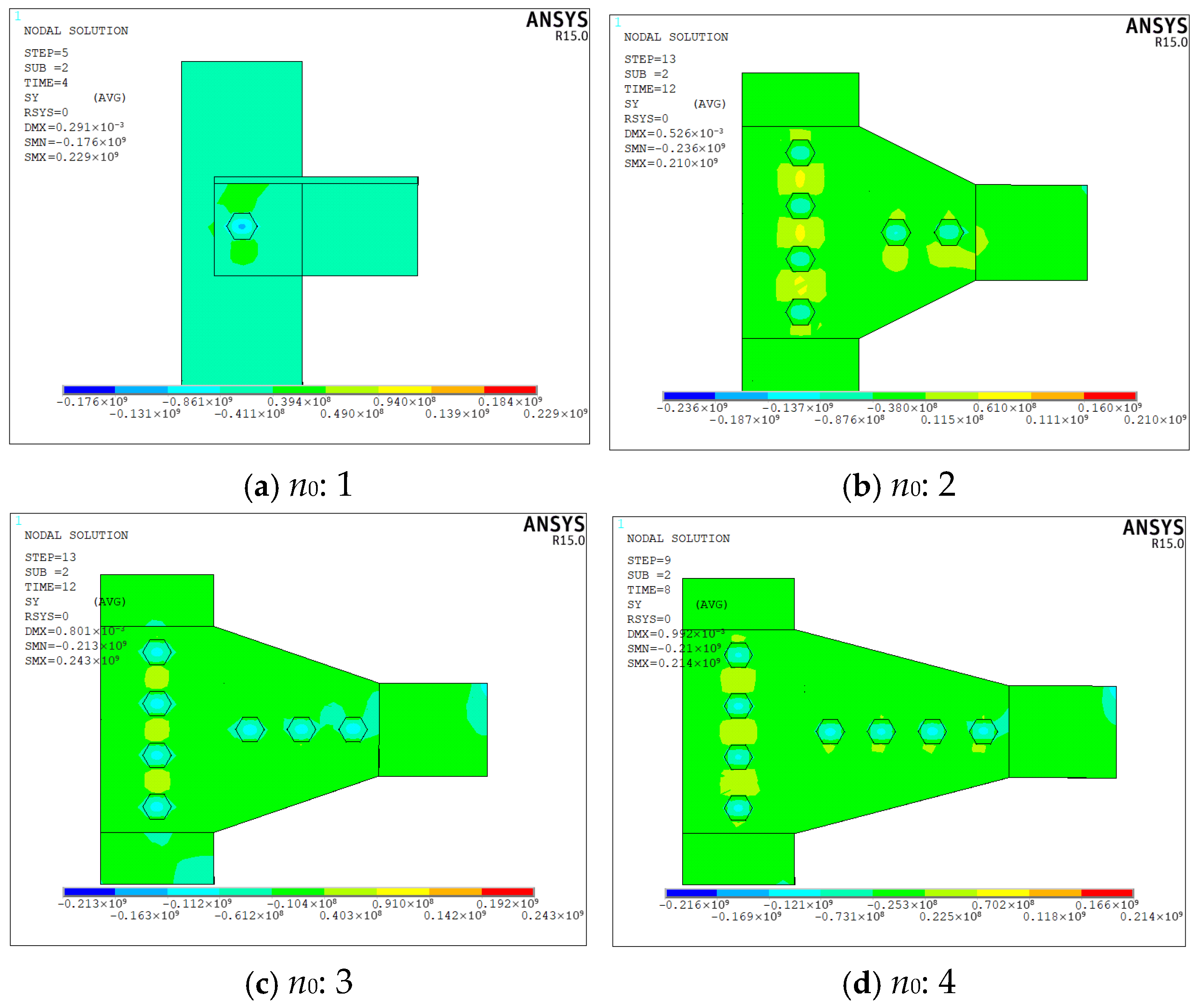

2.4. Parameter Settings for Bolted Connection Main Member Joints

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Factors Influencing Initial Rotation Stiffness

3.1.1. Bolt Diameter

3.1.2. Angle Steel Size

3.1.3. Bolt Preload

3.1.4. Friction Coefficient

3.1.5. Number of Bolts

3.1.6. Other Influencing Factors

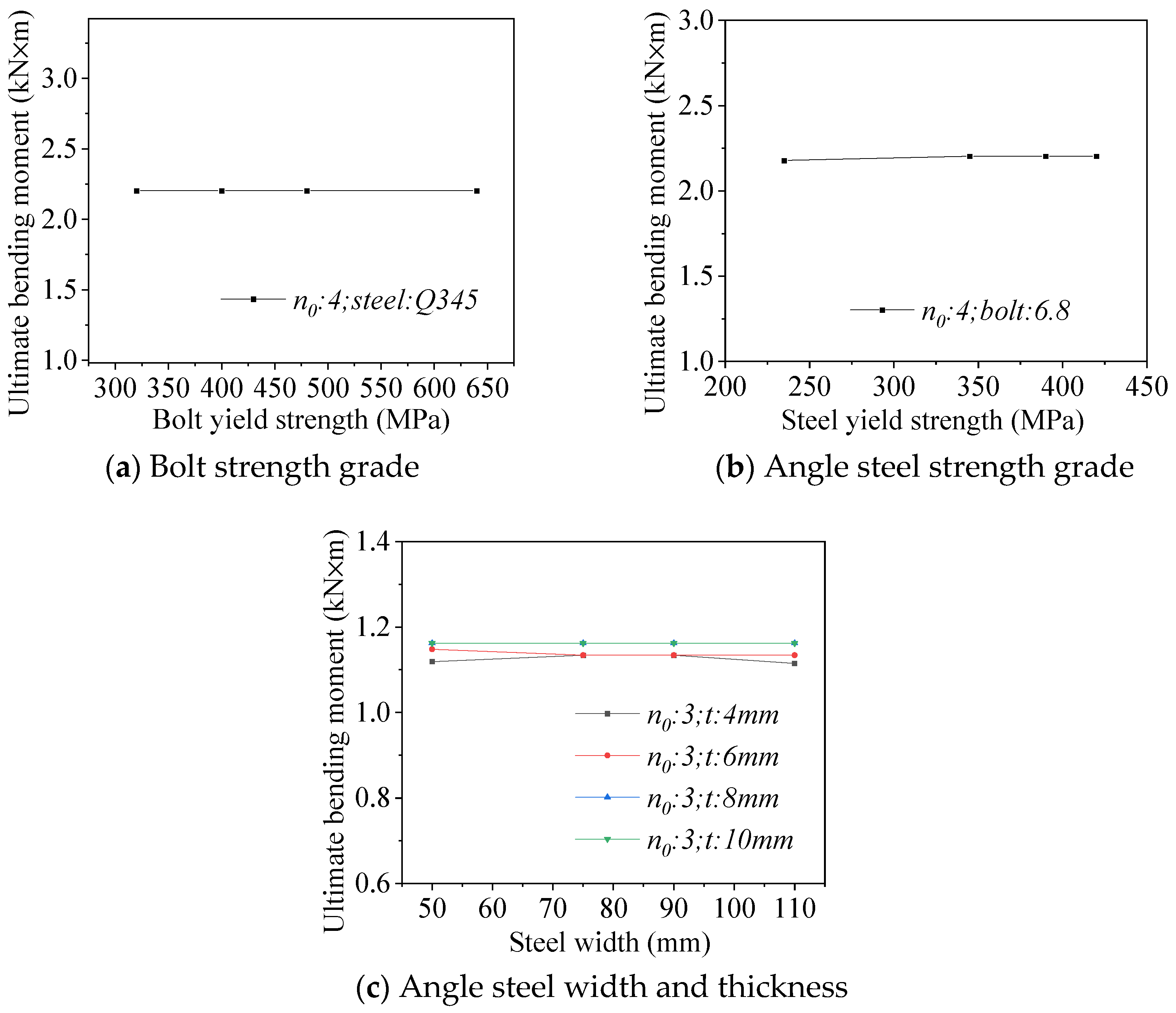

3.2. Factors Influencing Ultimate Bending Moment

3.2.1. Bolt Diameter

3.2.2. Bolt Preload

3.2.3. Friction Coefficient

3.2.4. Number of Bolts

3.2.5. Other Influencing Factors

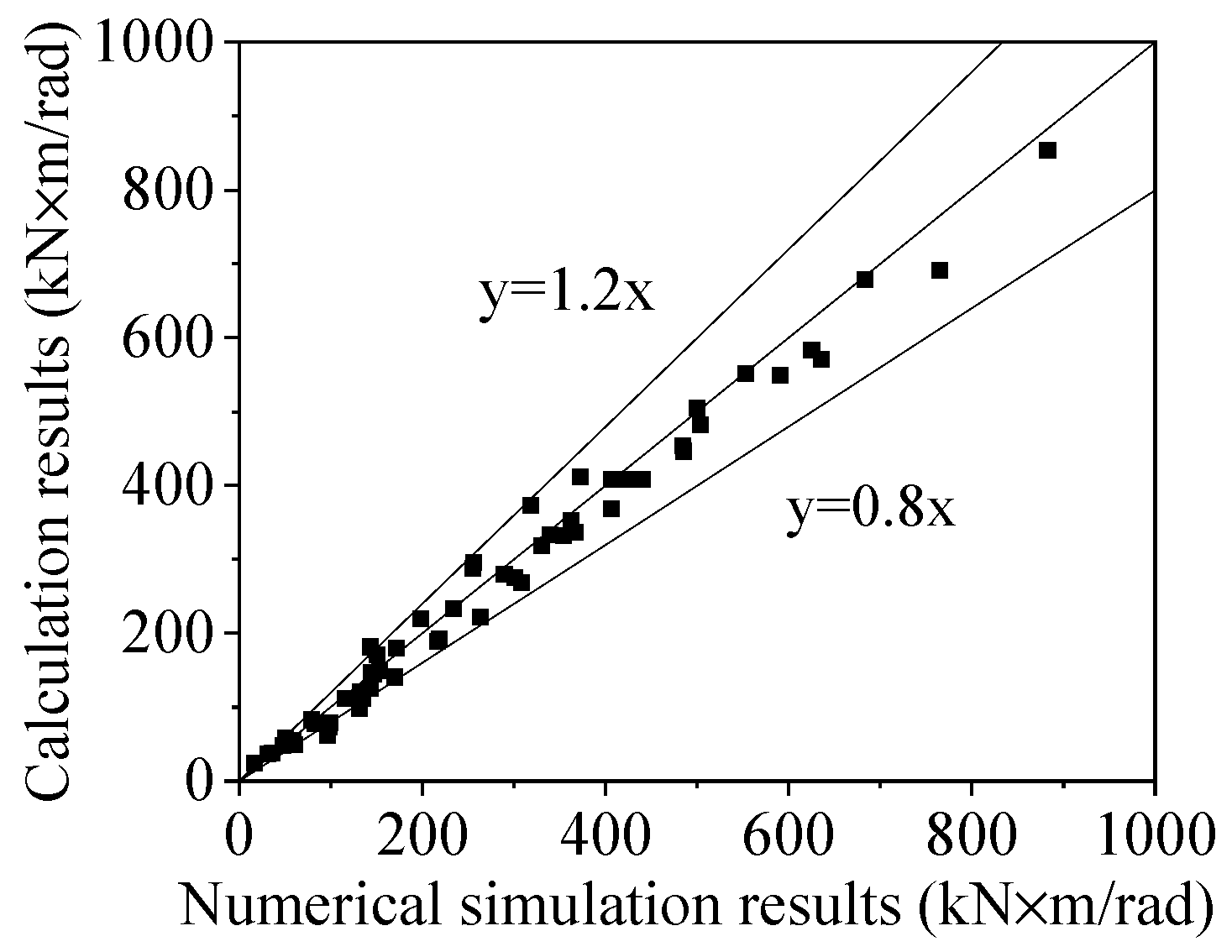

3.3. Moment-Rotation Relationship Model

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The primary factors influencing the initial rotational stiffness of the bolted joint are the bolt diameter, the width and thickness of the angle steel, the bolt preload, the friction coefficient, and the quantity of bolts. In contrast, the strength grades of both the bolt and the angle steel have minimal impact. Notably, the stiffness demonstrated an average increase of 50.6% per 4 mm increment as the diameter of the bolt increased from 12 mm to 24 mm. Furthermore, expanding the width from 50 to 75 mm resulted in a substantial average increase of 88.5% in the initial rotational stiffness. For angle steel widths increasing from 75 mm to 110 mm, the initial rotation stiffness increases by 17.4% on average for every 17.5 mm increase. The initial rotation stiffness increases by 33.8% on average for every 2 mm increase in angle steel thickness from 4 mm to 10 mm. As the friction coefficient increases, the range of initial rotation stiffness decreases. The initial rotation stiffness increases approximately linearly with an increase in the number of bolts.

- (2)

- Bolt diameter, preload, friction coefficient, and number of bolts have a strong influence on the ultimate bending moment of the bolted joint, while bolt strength, angle steel strength, angle steel width, and angle steel thickness have little effect. As the bolt diameter increases, the range of ultimate bending moment increases first, then decreases and increases sharply. The ultimate bending moment exhibits a linear correlation with both bolt preload and friction coefficient. Furthermore, it increases progressively with the number of bolts, demonstrating a more pronounced enhancement.

- (3)

- According to the analysis of different of bolted joint parameters, the moment-rotation curve model of semi-rigid joints is established by fitting, using the power function model proposed by Kishi-Chen [2] et al., and it can be used for mechanical performance analysis of semi-rigid steel structure joints with bolted connection.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Faella, C.; Piluso, V.; Rizzano, G. Structural Steel Semirigid Connections: Theory, Design and Software; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.F.; Kishi, N. Semirigid Steel Beam-to-Column Connections: Data Base and Modeling. J. Struct. Eng. 1989, 115, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attiogbe, E.; Morris, G. Moment-Rotation Functions for Steel Connections. J. Struct. Eng. 1991, 117, 1703–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reza, A.; Akbar, P. Nonlinear analysis of damped semi-rigid frames considering moment–shear interaction of connections. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2014, 81, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, H.; Uy, B.; Kang, W.; Hicks, S. System reliability evaluation of steel frames with semi-rigid connections. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2016, 121, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhu, X. Nonlinear dynamic collapse analysis of semi-rigid steel frames based on the finite particle method. Eng. Struct. 2016, 118, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.D.; Chen, Y.; Liu, C.Q.; Wu, H.D.; Wang, T.; Wei, X.D. An axial semi-rigid connection model for cross-type transverse branch plate-to-CHS joints (Article). Eng. Struct. 2019, 181, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, R.; Ibrahim, Z.; Jumaat, M.Z.; Hamid, Z.A.; Rahim, A.H.A. Behaviour of semi-rigid precast beam-to-column connection determined using static and reversible load tests. Meas. J. Int. Meas. Confed. 2020, 164, 108007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.M.; Shen, Z.Y. Influence of semi-rigid joints on internal force and displacement of steel frame structure. Build. Struct. 1991, 6, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Yu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Fan, F. Behavior of HCR semi-rigid joints under complex loads and its effect on stability of steel cooling towers. Eng. Struct. 2020, 222, 111062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, H.K.; Sakar, G. Semi-Rigid connections in steel structures State-of-the-Art report on modelling, analysis and design. Steel Compos. Struct. 2022, 45, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Dong, X. Numerical analysis of seismic performance of semi-rigid composite frame based on multi-scale. J. Tianjin Univ. (Nat. Sci. Eng. Technol. Ed.) 2016, 49, 161–167. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Z.; Wang, S.; Du, X.; Zhang, S. Research on mechanical properties of semi-rigid beam-column joints with T-shaped steel connections. J. Build. Struct. 2020, 41, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Zha, X.; Wang, K.; Wang, H. Initial lateral stiffness of plate-type modular steel frame structure with semi-rigid corner connections. Structures 2023, 56, 105021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Vu, Q.A. Analysis of steel frame with semi-rigid connections and constraints using a condensed finite element formulation. Int. J. GEOMATE 2023, 25, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, F.; Qiu, J.; Feng, H.; Wang, H.; Qian, H.; Jin, X.; Wang, K.; Fan, F. Calculation method of stability bearing capacity of transmission tower angle steel considering semi-rigid constraint. Curved Layer. Struct. 2022, 9, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, T. Direct Prediction Method for Semi-Rigid Behavior of K-Joint in Transmission Towers Based on Surrogate Model. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. 2023, 23, 2350027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, T. GPR-based prediction and uncertainty quantification for bearing capacity of steel tubular members considering semi-rigid connections in transmission towers. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 142, 106854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, T.; Lu, D.; Tan, Y. PDEM-based multi-component and global reliability evaluation framework for steel tubular transmission towers with semi-rigid connections. Eng. Struct. 2023, 295, 116838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sherif, R.H.; Ismael, M.A. Effect of Semi-Rigid Beam-Column Connection on Structural Behavior of Steel Frames. Fourth Int. Conf. Civ. Environ. Eng. Technol. AIP Conf. Proc. 2023, 2775, 020008-1–020008-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Wang, T.; Li, Z. Probabilistic bearing capacity assessment for cross-bracings with semi-rigid connections in transmission towers. Struct. Eng. Mech. 2024, 89, 309–321. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, D. Research on the Mechanical Calculation Model of Transmission Line Tower in Mining Area and the Interaction Mechanism of Tower-Line System. Doctoral Dissertation, China University of Mining and Technology, Xuzhou, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- BS EN 10027-1:2016; Designation Systems for Steels—Steel Names. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [CrossRef]

- EN 1993—1–8; Eurocode 3, Design of Steel Structures, Part 1–8: Design of Joints. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2005.

- GB 50017—2017; Standard for Design of Steel Structures. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China; Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2017.

- Kishi, N.; Chen, W.-F. Moment-rotation relations of semirigid connections with angles. J. Struct. Eng. 1990, 116, 1813–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mesh Size (mm) | Rotational Stiffness (rad) | Bending Moment (kN × m) | Time (min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 40.891 | 0.088 | 521 |

| 3 | 40.85788 | 0.088 | 210 |

| 4 | 40.65306 | 0.088 | 11 |

| 5 | 36.9529 | 0.088 | 7 |

| 6 | 35.14845 | 0.086 | 5 |

| Model-Influencing Factors | Values |

|---|---|

| Number of bolts n0 | 4, 3, 2, 1 |

| Bolt grade (grade) | 8.8, 6.8, 5.8, 4.8 |

| Angle steel grade (grade) (EN 10027-1:2016) [23] | Q235, Q345, Q390, Q420 (S235JR, S335JR, S390JR, S420NL) |

| Bolt diameter d (mm) | 24, 20, 16, 12 |

| Angle steel thickness t (mm) | 10, 8, 6, 4 |

| Angle steel width l (mm) | 110, 90, 75, 50 |

| Bolt preload (relative to the installation) x% | 100%, 75%, 50%, 25% |

| Friction coefficient μ | 0.5, 0.4, 0.3, 0.2, 0.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kang, M.; Hou, S.; Cai, J.; Zhang, L. A Moment-Rotation Model of Semi-Rigid Steel Structure Joints with Bolted Connection. Buildings 2026, 16, 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010182

Kang M, Hou S, Cai J, Zhang L. A Moment-Rotation Model of Semi-Rigid Steel Structure Joints with Bolted Connection. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):182. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010182

Chicago/Turabian StyleKang, Mengxin, Shifeng Hou, Juyang Cai, and Liang Zhang. 2026. "A Moment-Rotation Model of Semi-Rigid Steel Structure Joints with Bolted Connection" Buildings 16, no. 1: 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010182

APA StyleKang, M., Hou, S., Cai, J., & Zhang, L. (2026). A Moment-Rotation Model of Semi-Rigid Steel Structure Joints with Bolted Connection. Buildings, 16(1), 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010182