Experimental Study on the Mechanical Performance of Cast-in-Place Base Joints for X-Shaped Columns in Cooling Towers

Abstract

1. Introduction

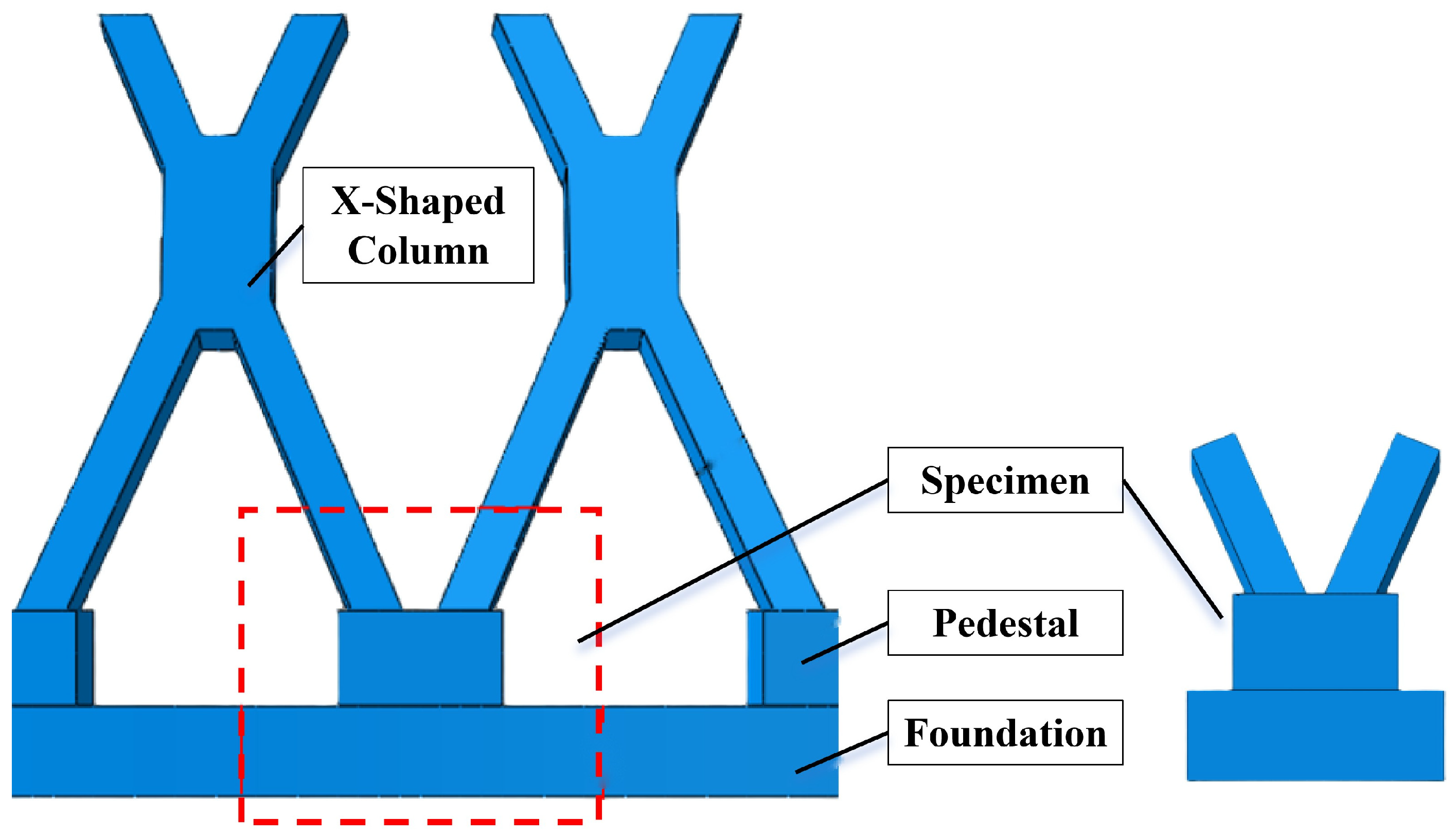

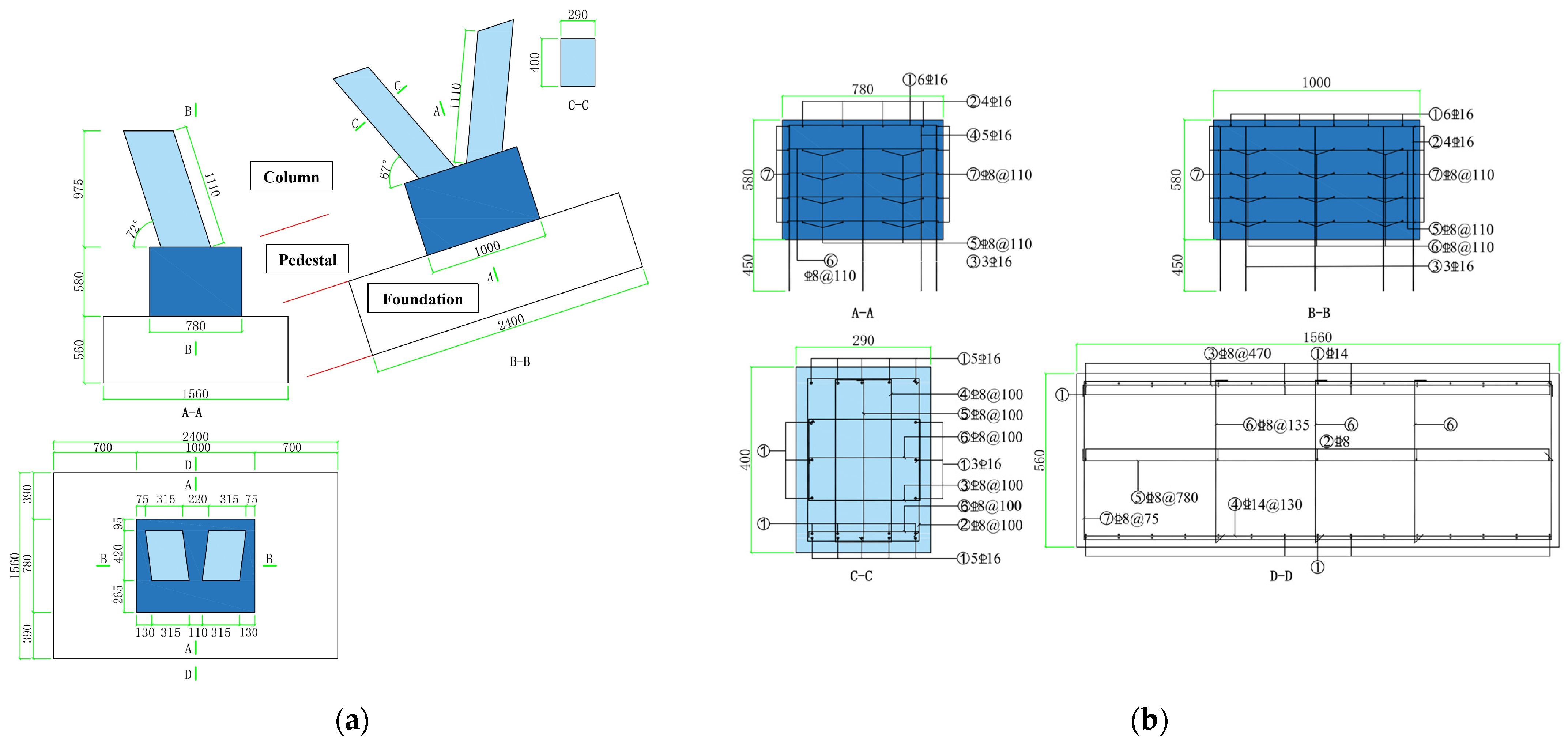

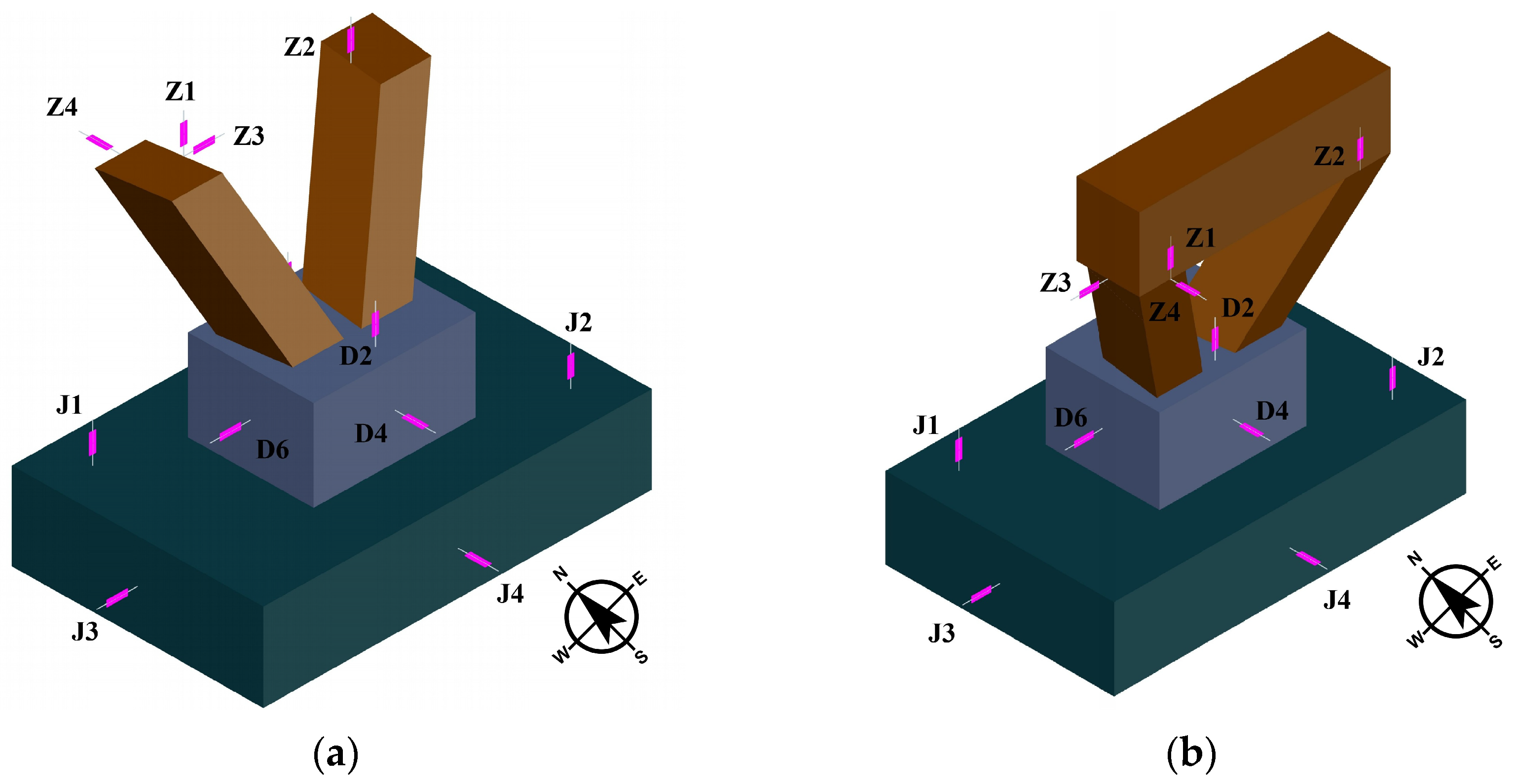

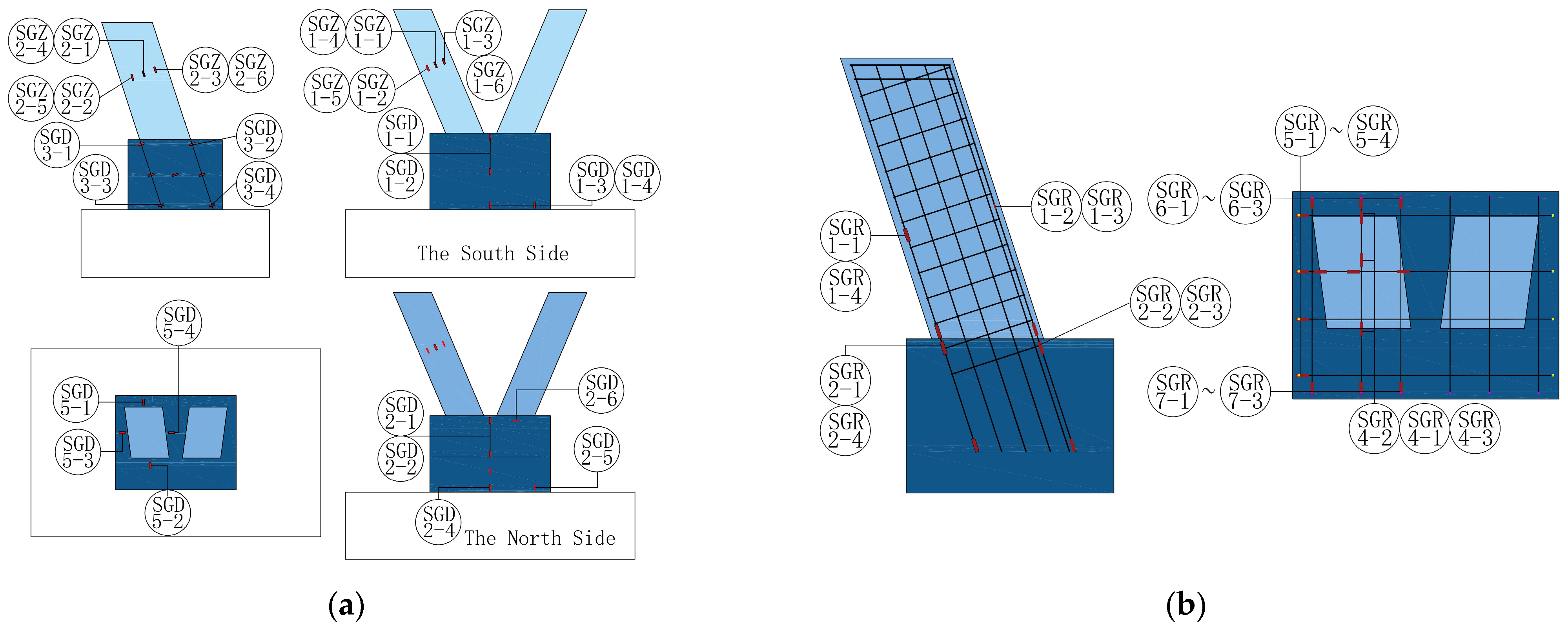

2. Experimental Program

2.1. Specimens and Material

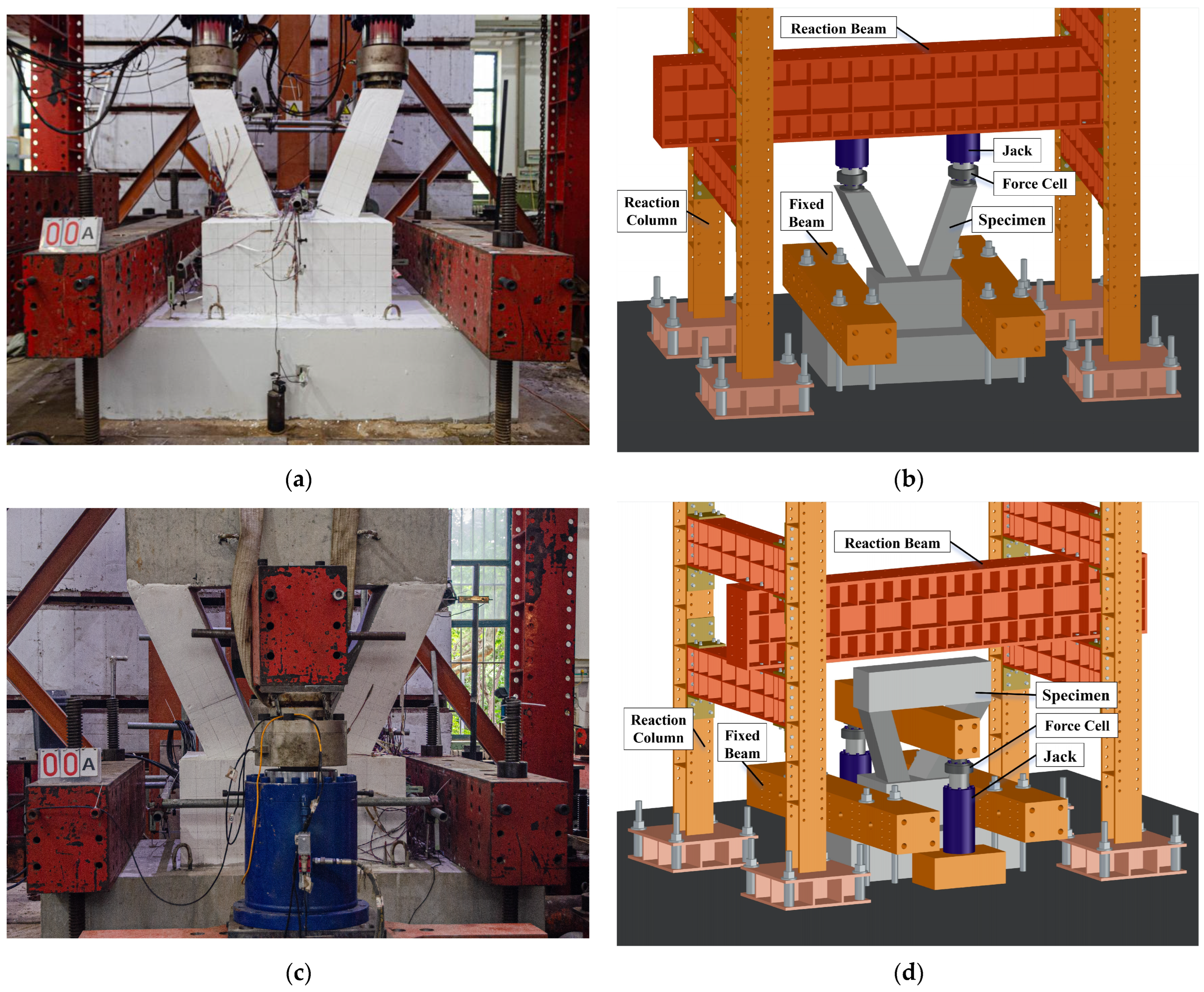

2.2. Test Setup and Loading History

3. Test Results and Analysis

3.1. Crack Propagation and Failure State

3.1.1. Compression Specimen

- Phase 1:

- Initial loading showed no visible deformation, though pre-existing microcracks from construction and curing were observed on concrete surfaces.

- Phase 2:

- Fine cracks developed in both the east and west columns. The cracks initially appeared at the common edge on the south side of the X-shaped columns and subsequently propagated across both adjacent surfaces, as shown in Figure 6. Concurrently, cracks emerged at the interface between the top surface of the pedestal and the columns.

- Phase 3:

- The loading mode was switched to displacement control. Superficial cement peeling was observed on the concrete surface at the bottom of the columns on north side. Meanwhile, the cracks on the top surface of the pedestal began to extend radially.

- Phase 4:

- Concrete crushing occurred at the bottom of the north side of the columns. A pronounced, elongated crack developed on the pedestal’s top surface, accompanied by the appearance of fine cracks on the south face, as depicted in Figure 7.

- Phase 5:

- Localized concrete spalling was observed at the bottom of the north side of the inclined columns. A prominent transverse crack developed on the south face of the pedestal, while fine cracks initiated on its east and west sides.

- Phase 6:

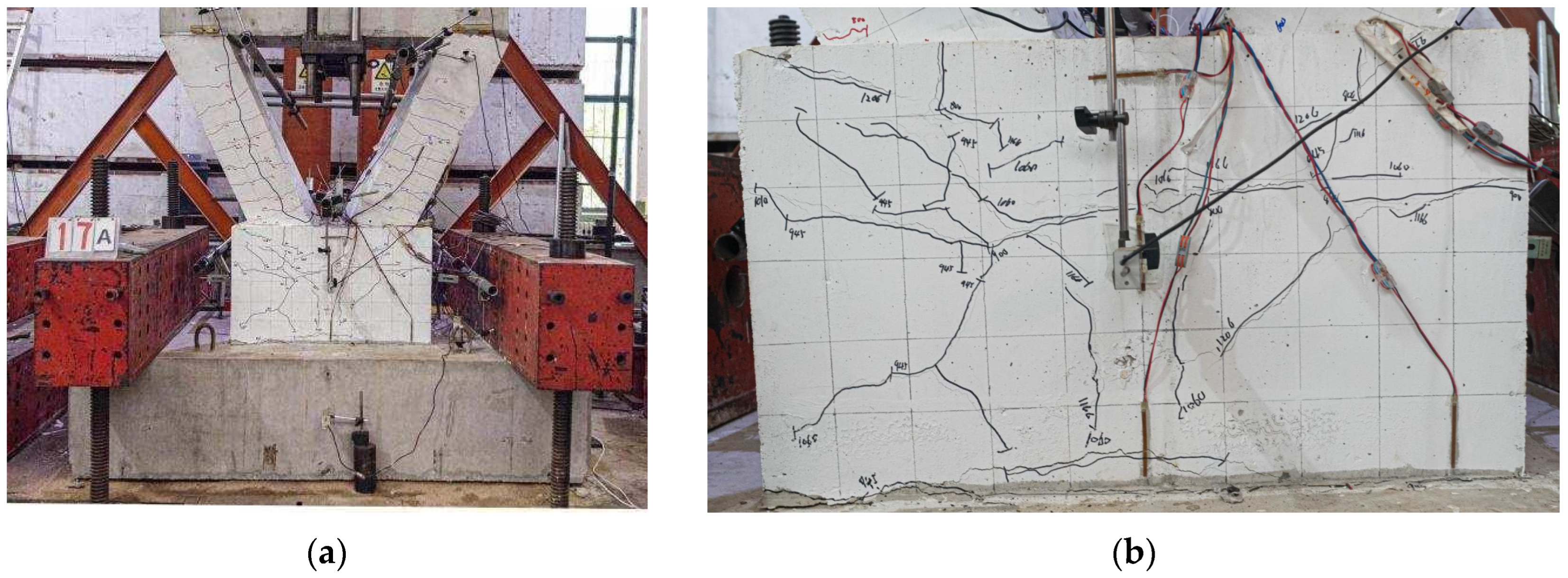

- The crack patterns in the columns fully developed. Extensive concrete spalling occurred at the bottom of the north side of the columns, with a visible separation gap appearing between the column bases and the pedestal top surface. The pedestal top surface showed slight upward bulging, while the cracks on the east and west sides remained relatively narrow, as shown in Figure 8.

3.1.2. Tension Specimen

- Phase 1:

- During the initial loading stage, no significant deformation was observed in the east and west columns, and no new cracks appeared on the concrete surfaces of either the inclined columns or the pedestal.

- Phase 2:

- Cracks developed in both columns, initiating from the edge on the south side of the X-shaped columns and subsequently propagating across both adjacent surfaces. The widest crack was observed at the interface between the top surface of the pedestal and the columns, as shown in Figure 9.

- Phase 3:

- Cracks on the surfaces of the X-shaped inclined columns continued to propagate. Cracks emerged on the top surface of the pedestal, initiating from the midpoint between the two column bases and extending towards the south face, where they developed into vertical cracks. A limited number of transverse cracks appeared on the south face of the pedestal, while minor diagonal cracks formed on its east and west sides.

- Phase 4:

- The loading mode was switched to displacement control. The crack pattern in the columns stabilized, with further development primarily manifesting as crack width enlargement. On the south face of the pedestal, the transverse cracks propagated completely across the surface and intersected with the vertical cracks, as shown in Figure 10.

- Phase 5:

- The crack patterns in the columns remained. A prominent transverse crack developed at the bottom of the south face of the pedestal, while additional vertical cracks formed at the top of the same face and propagated downward. The diagonal cracks on the east and west sides of the pedestal continued to extend.

- Phase 6:

- The cracks were fully developed, parallel to each other along the direction of the column sections. On the south face of the pedestal, transverse and vertical cracks intersected, forming a grid-like pattern. The diagonal cracks on the east and west sides propagated from the south edge toward the mid-section of the pedestal, as shown in Figure 11.

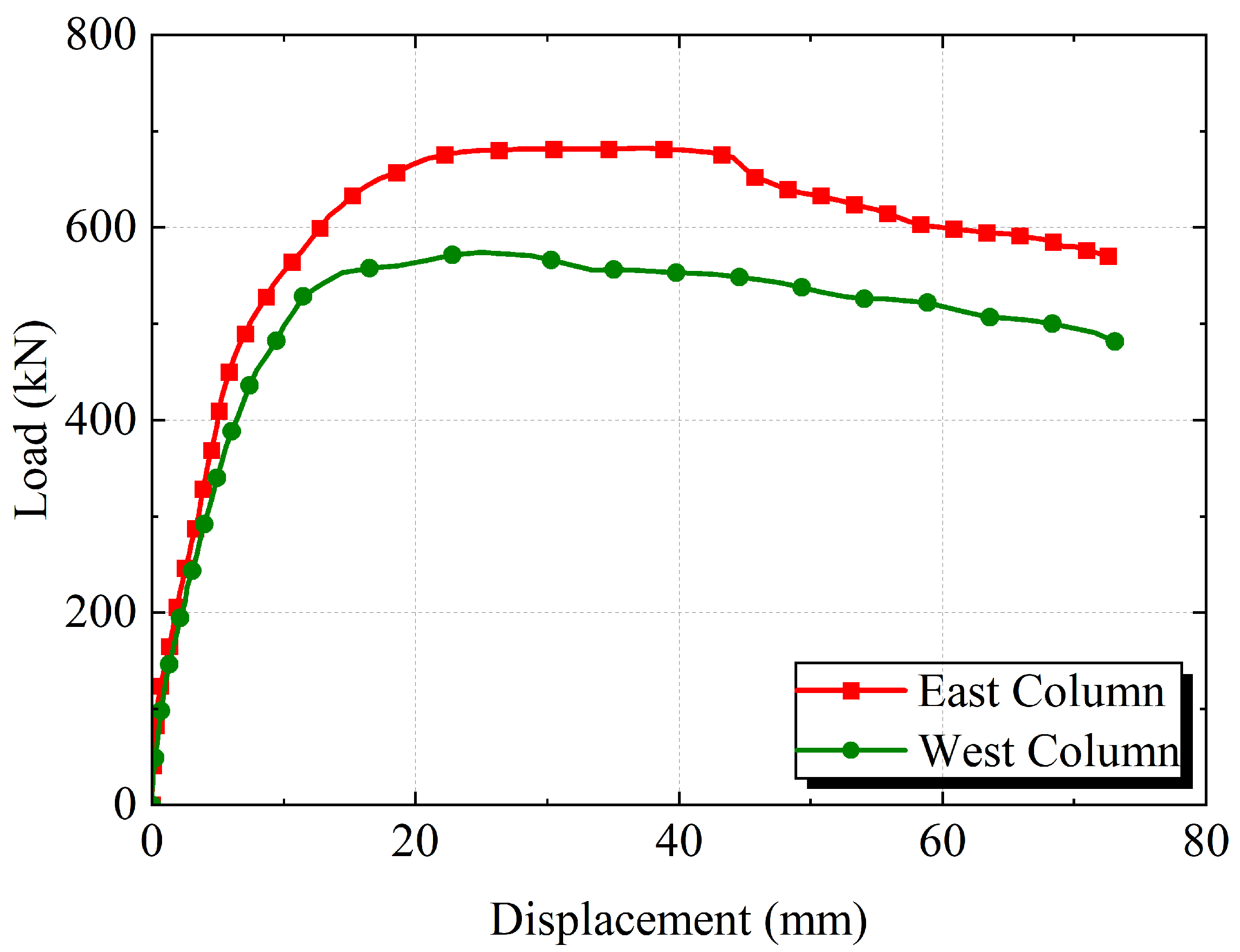

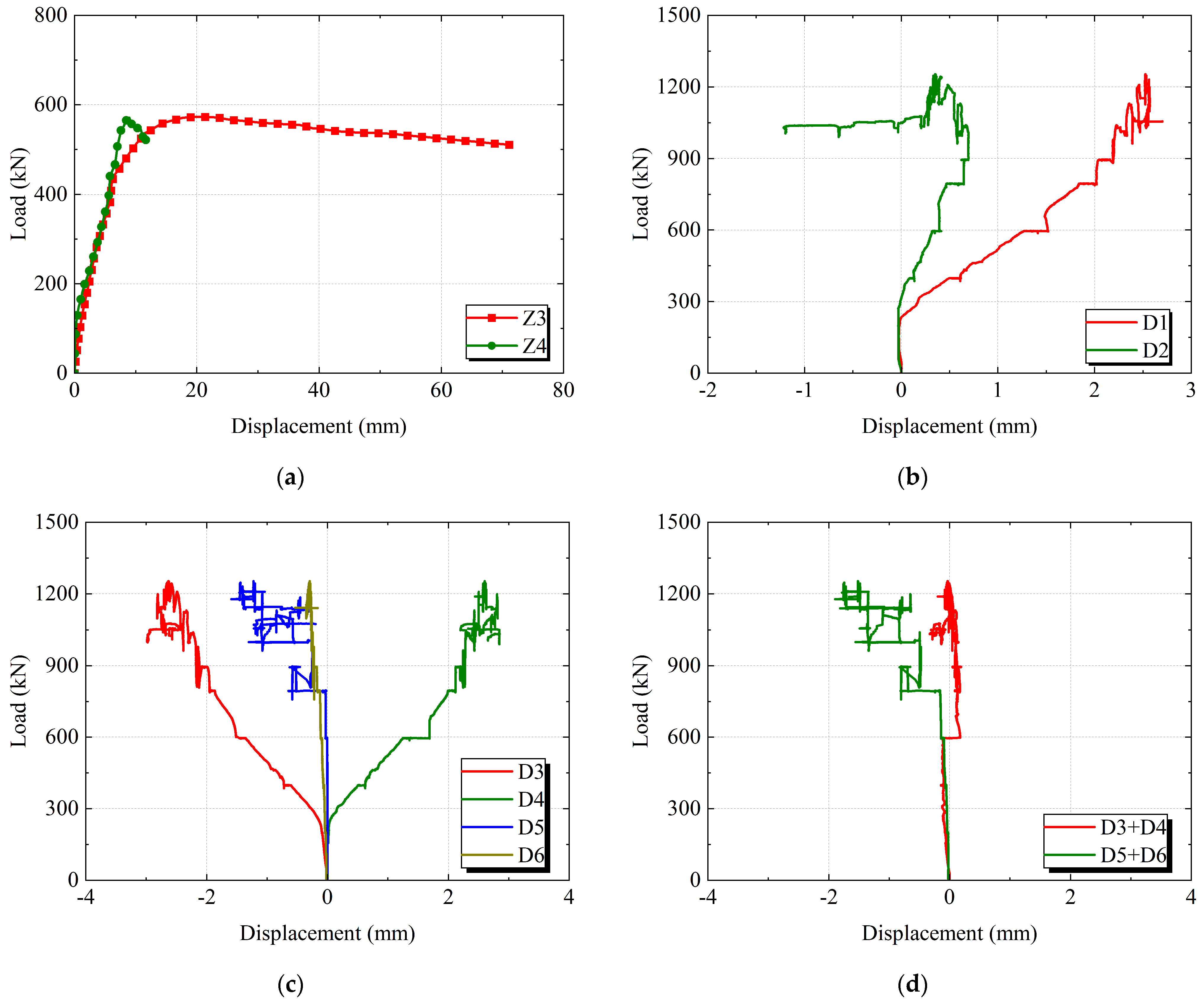

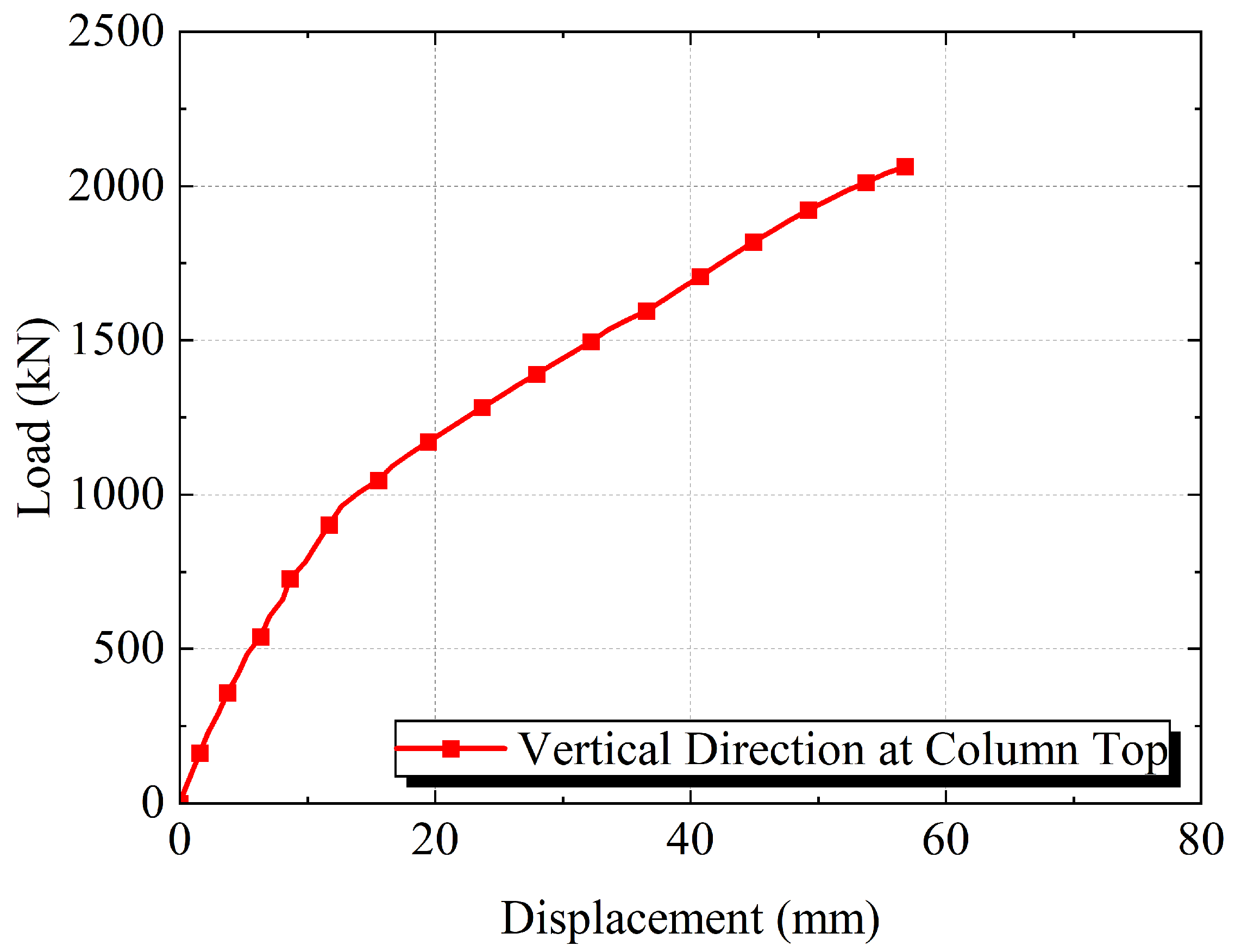

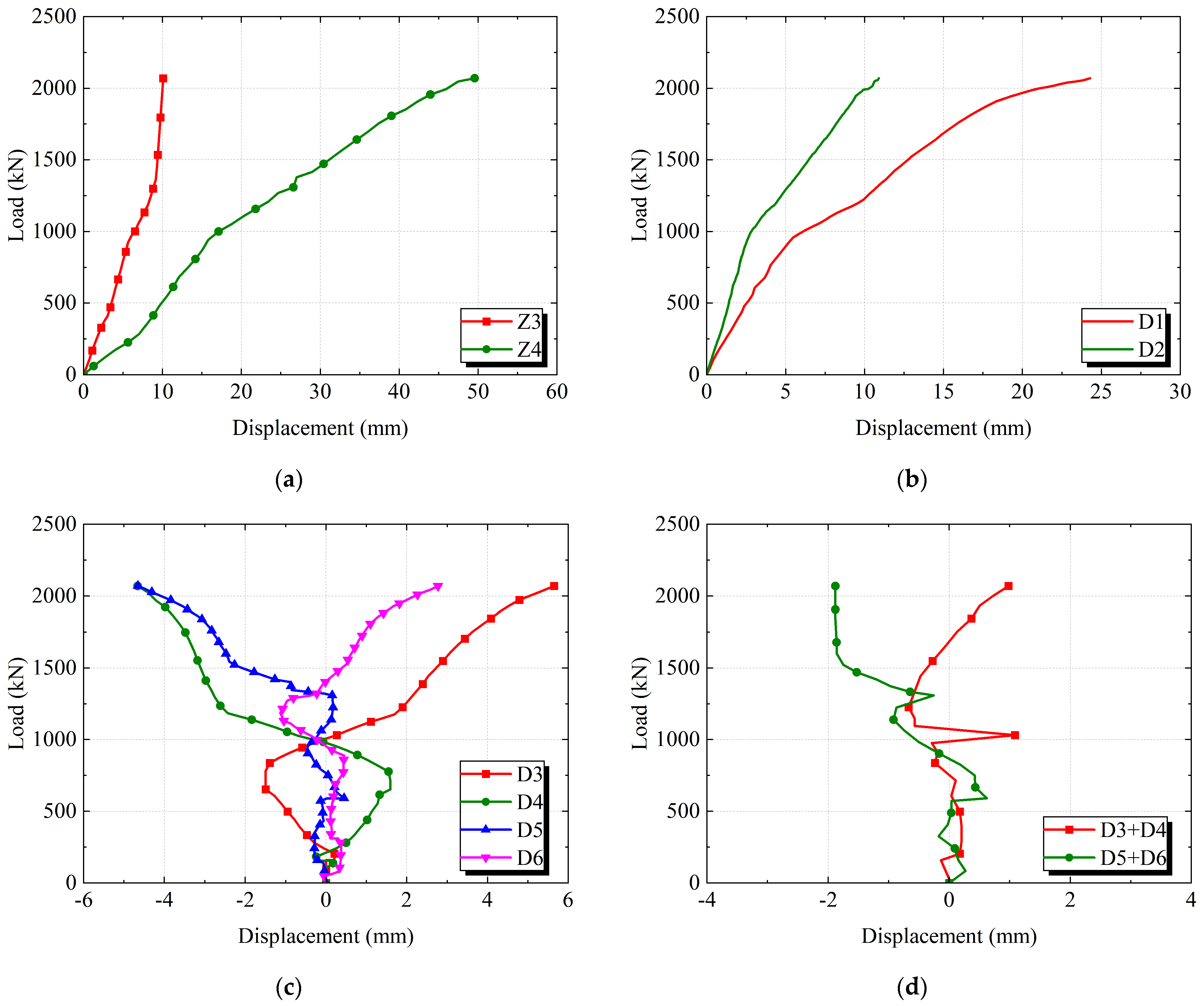

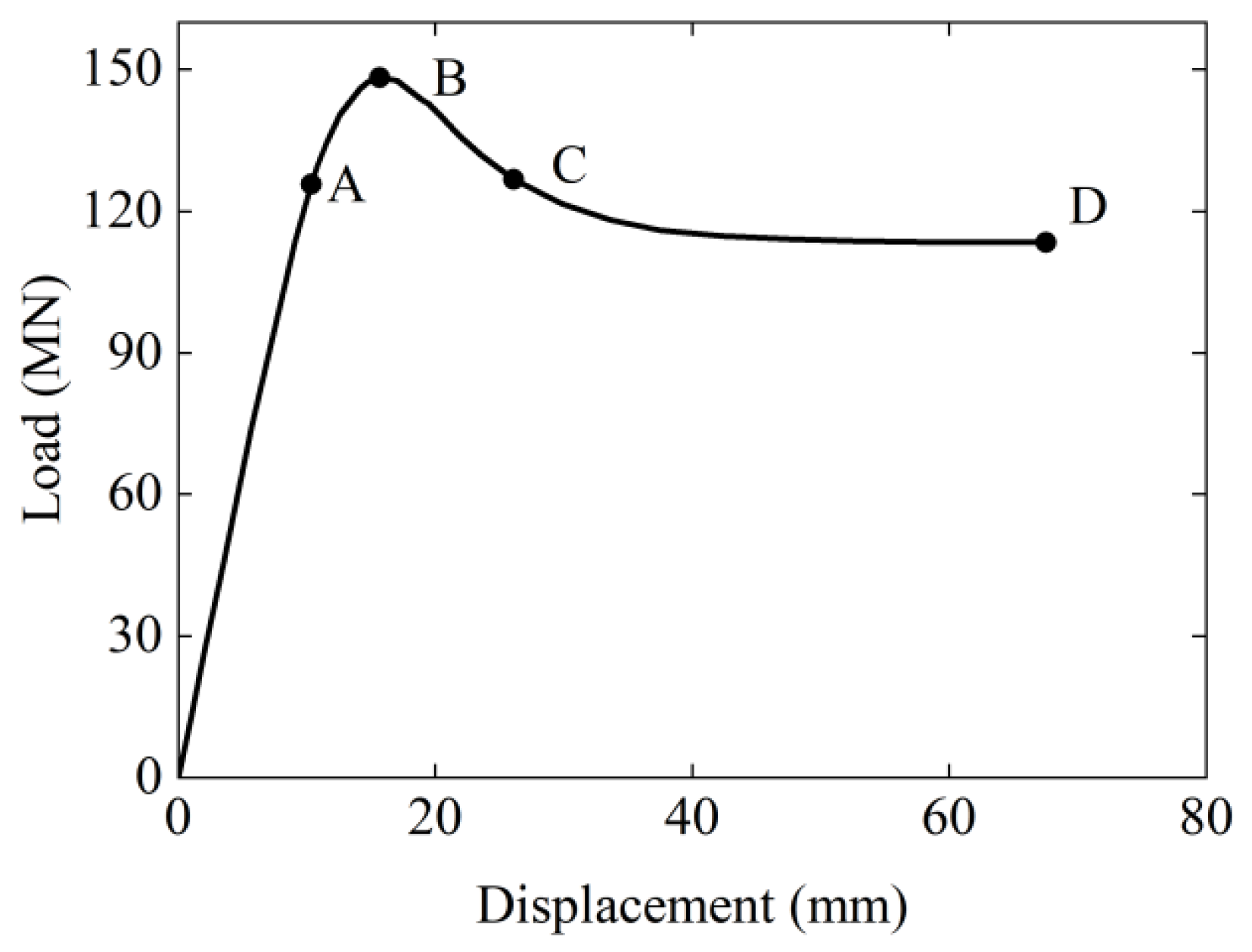

3.2. Load–Displacement Relationships

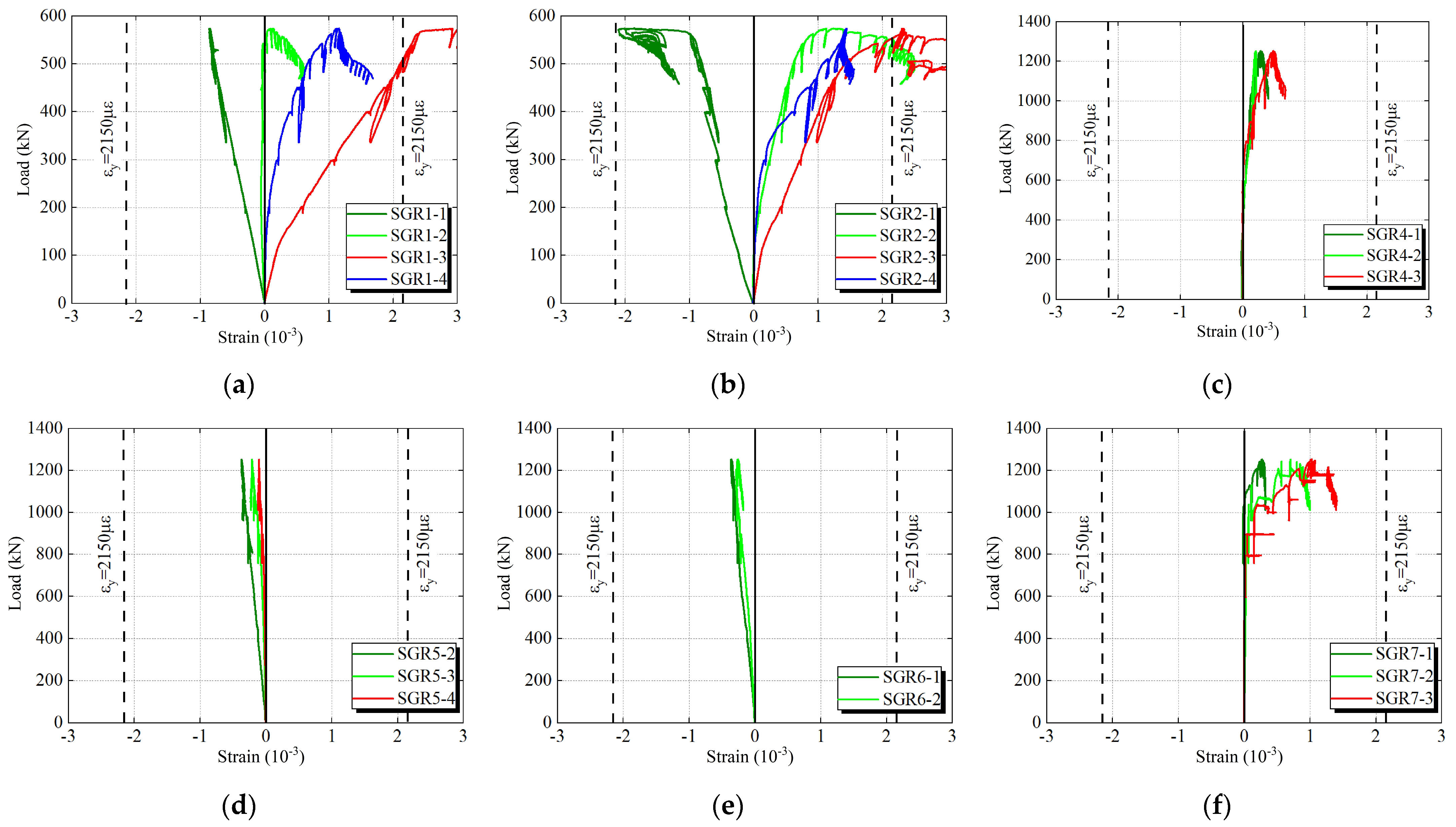

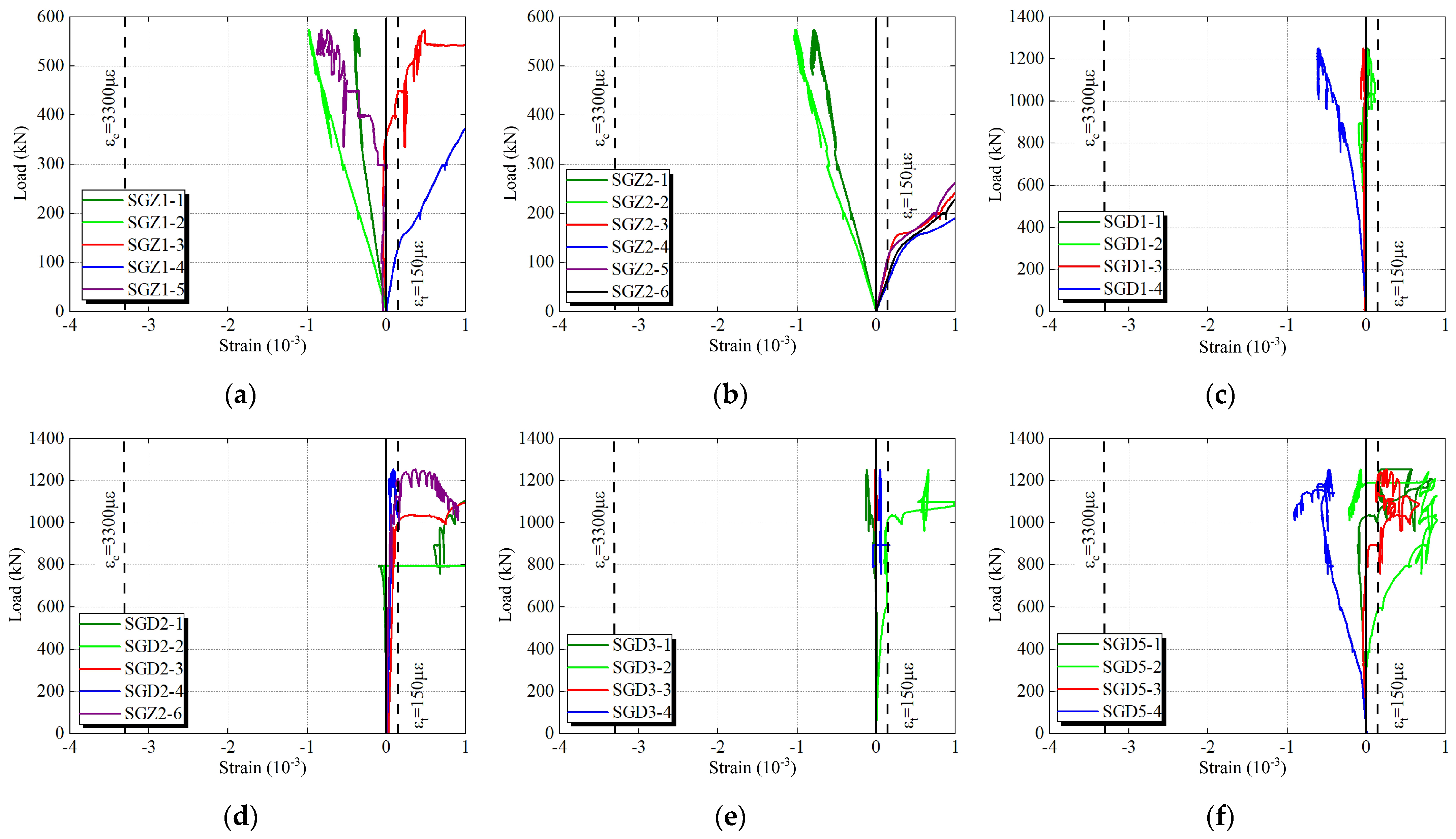

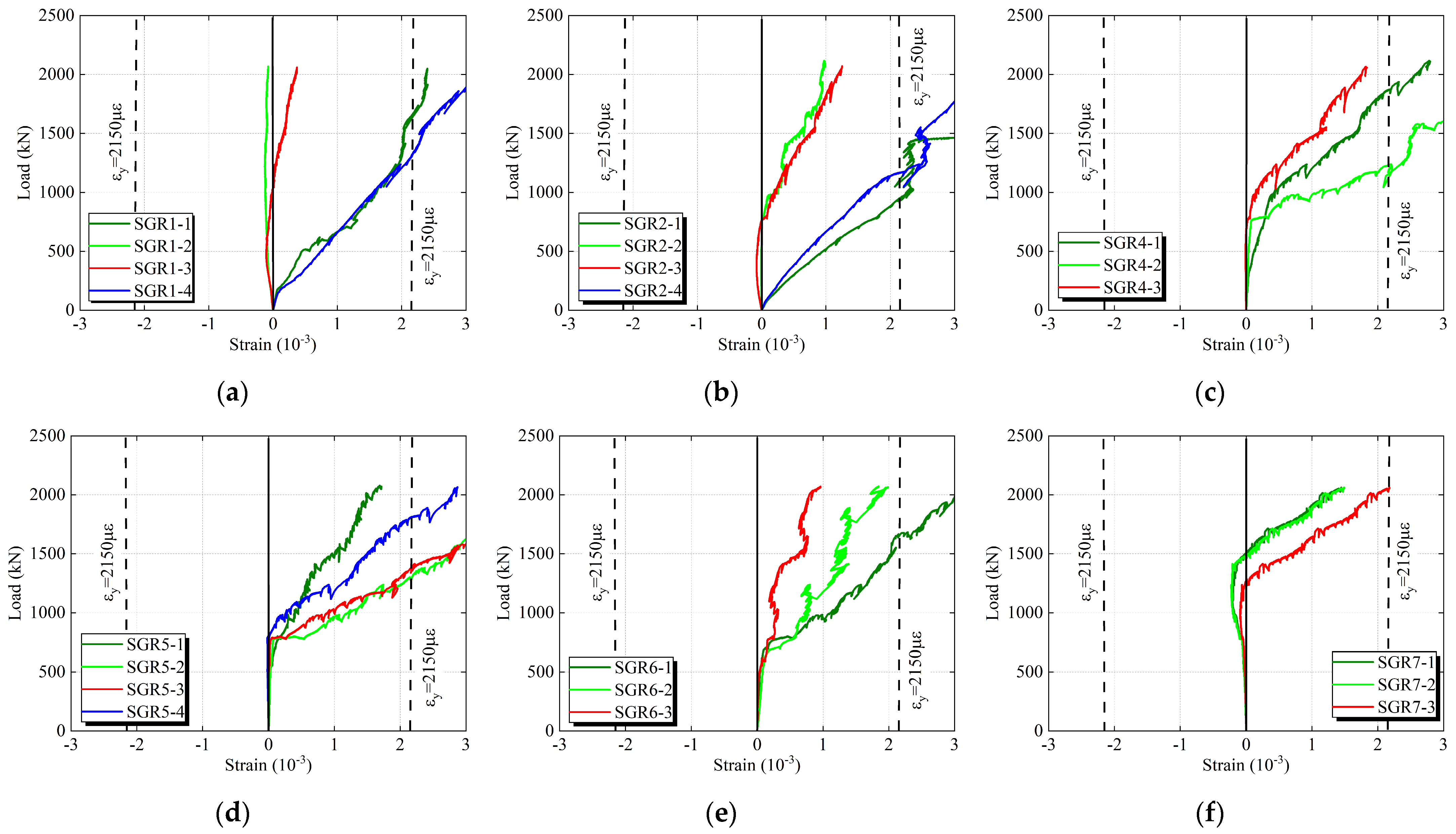

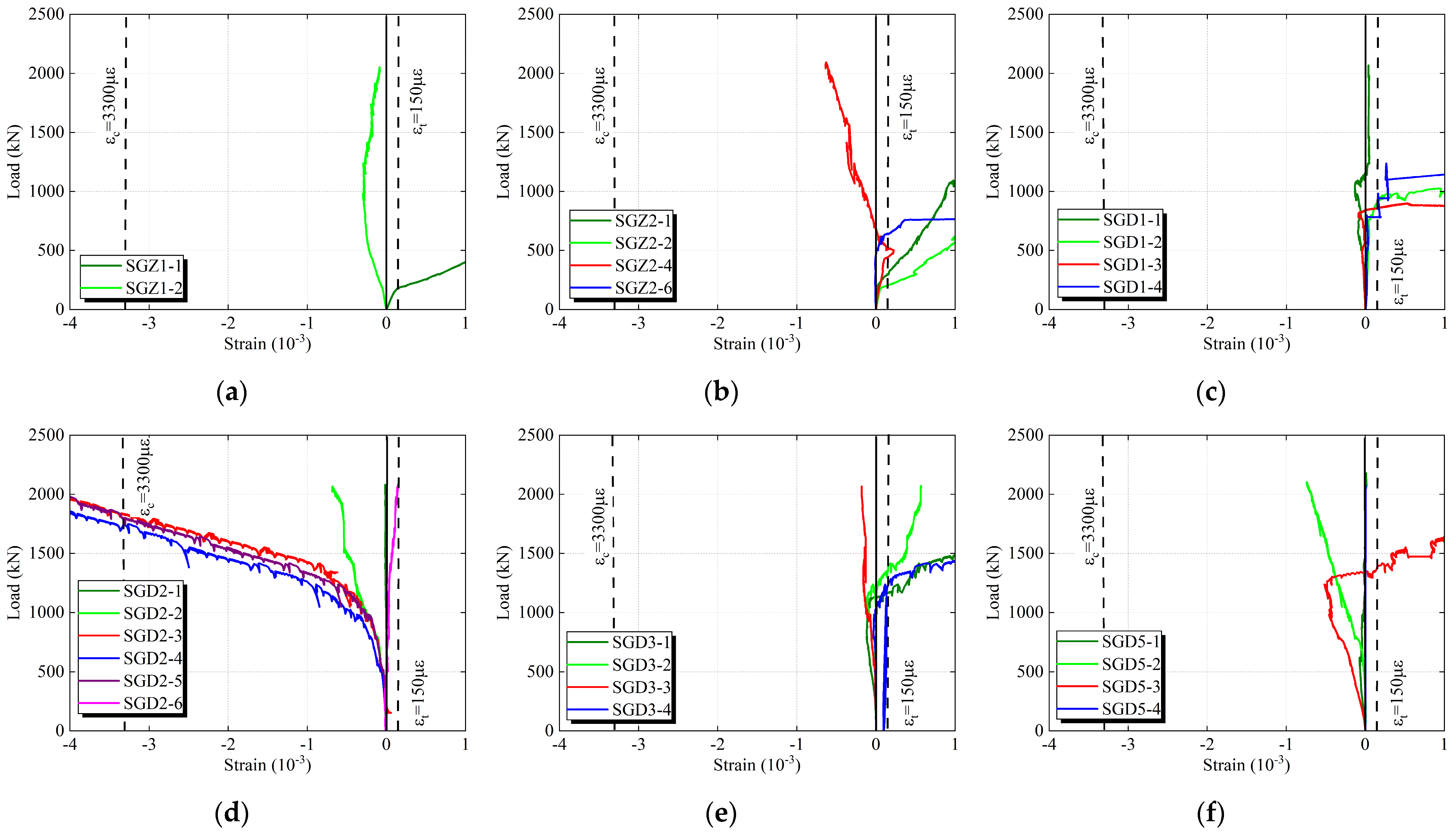

3.3. Load–Strain Relationships

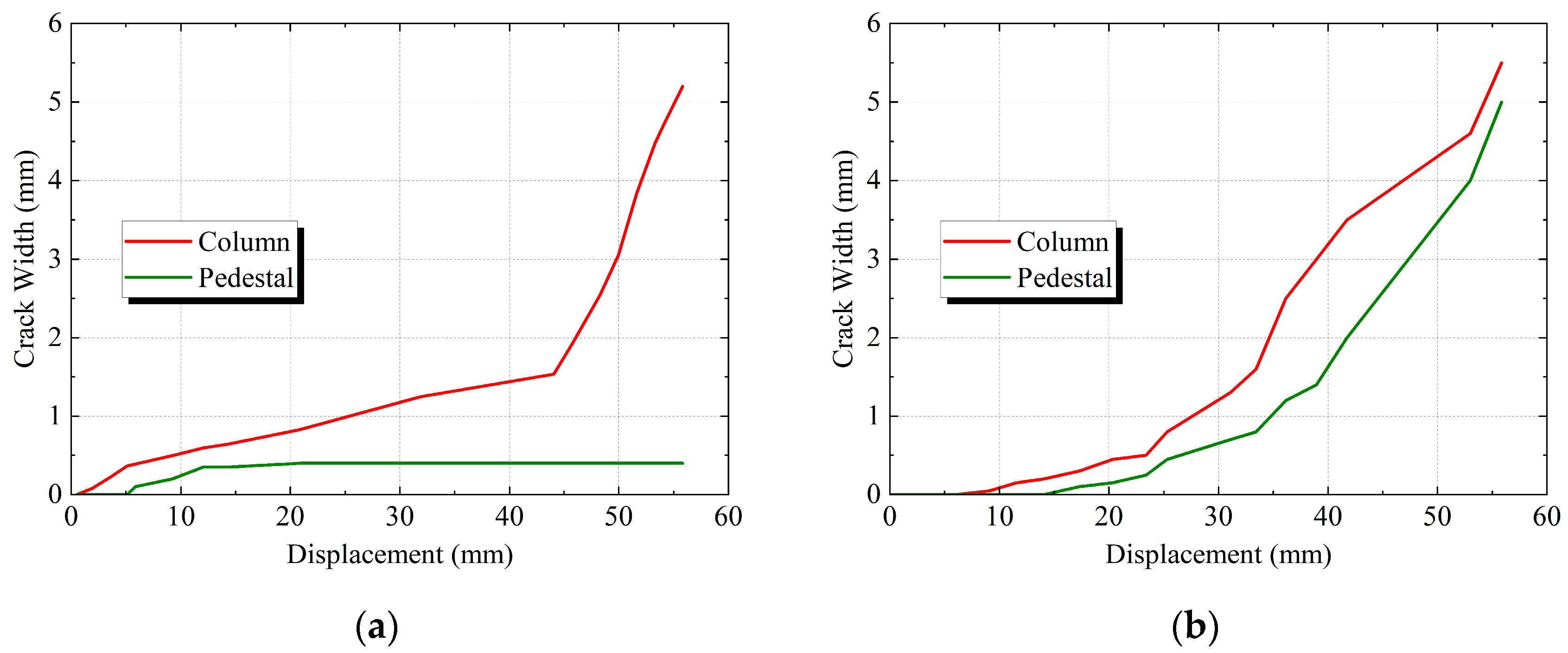

3.4. Crack Width Progression Curve

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanical Response

- Stage 1:

- Elastic Stage (0A). Point A represents the yield point of the specimen. During this stage, the load increases linearly. The concrete and reinforcement work in concert with good bond integrity, jointly resisting the external force. No cracking occurs in the concrete, and the overall structure remains intact.

- Stage 2:

- Elasto-plastic Stage (AB). In this stage, the curve begins to deviate from linearity, and the relationship between load and displacement becomes nonlinear, although the load continues to increase. After the reinforcement yields, the bond between the reinforcement and concrete begins to degrade, and the slip of the reinforcement within the concrete occurs. The load reaches its peak at Point B.

- Stage 3:

- Descending Stage (BC). After Point B, the curve enters the descending branch. A pronounced decline is observed in the stage: the load begins to decrease while the displacement continues to increase. The compressive stress in the concrete compression zone reaches the ultimate compressive strain, initiating failure phenomena such as crushing or diagonal cracking. Consequently, the load-bearing capacity of the concrete declines rapidly. Point C indicates the ultimate load.

- Stage 4:

- Failure Stage (CD). Point D, where the load has decreased to 0.85 times the peak load, defines the end of the test.

- 1.

- Compression Specimen

- 2.

- Tension Specimen

4.2. Load–Strain Response

- Compression Specimen

- 2.

- Tension Specimen

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The cast-in-place joint design for X-shaped reinforced concrete columns was validated as feasible and reliable for application in super-large cooling towers. The joints exhibited excellent mechanical performance, including substantial load-bearing capacity and pronounced ductility under both compressive and tensile loading regimes.

- (2)

- The failure mechanism confirmed the design principle of a strong joint–weak component. Specifically, the plastic hinge formed in the column section above the base, while the joint remained intact and stable even after the column yielded. This ensures progressive failure, which is crucial for structural safety under extreme conditions.

- (3)

- Under compression, the joint failed in a ductile flexural compression manner, whereas the failure was tension-controlled under uplift. The tensile specimen demonstrated higher initial stiffness and yield load compared to the compressive specimen, which experienced earlier stiffness degradation due to concrete crushing under combined compression and bending.

- (4)

- The strain analysis revealed a sequential yielding process of the longitudinal reinforcement and a complex internal stress distribution within the pedestal, which effectively facilitated stress diffusion and delayed catastrophic failure.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zheng, W.Y.; Zhu, D.S.; Song, J.; Zeng, L.D.; Zhou, H.J. Experimental and computational analysis of thermal performance of the oval tube closed wet cooling tower. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2012, 35, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Dong, X.; Huang, S.K.; Chen, M.; Ge, Y.J. Tornado-induced instability assessment of super large hyperbolic reinforced concrete cooling towers. Eng. Struct. 2024, 312, 118224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.Y. Stability and Continuous Collapse Prevention of Scaffold Structures of Inclined Column of Cooling Tower. Master’s Thesis, Shandong University, Jinan, China, 2018. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Viladkar, M.N.; Karisiddappa; Bhargava, P.; Godbole, P.N. Static soil–structure interaction response of hyperbolic cooling towers to symmetrical wind loads. Eng. Struct. 2006, 28, 1236–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.L.; Zhao, L.; Qian, J.H.; Chen, Y.Y. Wind-induced collapse mode and mechanism of super-large hyperbolic steel reticulated shell cooling tower with stiffening rings. Eng. Struct. 2024, 321, 118985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, S.T.; Ge, Y.J. The influence of self-excited forces on wind loads and wind effects for super-large cooling towers. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2014, 132, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witasse, R.; Georgin, J.F.; Reynouard, J.M. Nuclear cooling tower submitted to shrinkage; behavior under weight and wind. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2002, 217, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, H.C. Nonlinear behavior and ultimate load bearing capacity of reinforced concrete natural draught cooling tower shell. Eng. Struct. 2006, 28, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DL/T 5339-2018; Code for Hydraulic Design of Fossil Fired Power Plant. China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2018. (In Chinese)

- GB/T 50102-2014; Code for Design of Cooling for Industrial Recirculating Water. China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2014. (In Chinese)

- GB 50009-2012; Load Code for the Design of Building Structures. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2012. (In Chinese)

- VGB-S-610-00-2019-10-EN; Structural Design of Cooling Towers. VGB PowerTech e.V.: Essen, Germany, 2019.

- Rajashekhar; Kulkarni, S. Seismic analysis of hyperbolic cooling tower considering different column supporting systems: A case study. J. Struct. Eng. 2019, 12, 18–37. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, P.; Ke, S.T. Study on the pillars model selection of large hyperbolic cooling tower. Chin. J. Appl. Mech. 2016, 33, 116–122+186. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.J.; Zha, X.X.; Xu, P.C.; Li, W.T. Stability of slender concrete-filled steel tubular X-column under axial compression. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2021, 185, 106876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.J. Mechanical Behavior of Tapered Concrete-Filled Steel Tubular X-Columns. Ph.D. Thesis, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China, 2022. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.J.; Zha, X.X.; Fan, Y.H. Theoretical and experimental investigations on the stability performance of concrete filled steel tubular X-column with regard to the flexural rigidity variation. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 78, 107698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J.P.; Skrikerud, P.E. Influence of geometry and of the constitutive law of the supporting columns on the seismic response of a hyperbolic cooling tower. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1980, 8, 415–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.L. Analyses of cooling tower dynamics. J. Sound Vib. 1981, 79, 501–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabouri-Ghomi, S.; Abedi Nik, F.; Roufegarinejad, A.; A Bradford, M. Numerical study of the nonlinear dynamic behaviour of reinforced concrete cooling towers under earthquake excitation. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2006, 9, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziraoui, A.; Kissi, B.; Aaya, H.; Ahnouz, I. Dynamic response of hyperbolic cooling tower considering different column supporting systems subjected to seismic actions. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2024, 429, 113632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, N.H.; Zhang, W.P.; Zhou, Y.; Cai, F.; Liu, Y. Seismic response analysis of reinforced concrete cooling tower subjected to corrosion. Eng. Struct. 2025, 344, 121286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.T.; Uy, B.; Li, D.X.; Thai, H.T.; Mo, J.; Khan, M. Behaviour and design of coupled steel-concrete composite wall-frame structures. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2023, 208, 107984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.T.; Khan, M.; Uy, B.; Katwal, U.; Tao, Z.; Thai, H.T.; Ngo, T. Long-term performance of steel-concrete composite wall panels under axial compression. Structures 2024, 64, 106606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.T.; Zhang, T.; Wang, W.W.; Zhang, L.Q.; Xue, G.F. Behavior of concrete-filled circular steel tubular stub columns exposed to corrosion and freeze–thaw cycles. Structures 2023, 55, 2266–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.T.; Khan, M.; Uy, B.; Lim, L.; Thai, H.T.; Ngo, T. Behaviour, design and performance of steel-concrete composite walls in fire. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2025, 227, 109408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.H.; Li, W.; Bjoehovde, R. Developments and advanced applications of concrete-filled steel tubular (CFST) structures: Members. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2014, 100, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurdakul, Ö.; Routil, L.; Culek, B.; Avşar, Ö. CFRP-based structural repairing and strengthening of deficient cast-in-place RC foundation-column joints. Eng. Struct. 2025, 343, 121236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 50081-2019; Standard for Test Methods of Concrete Physical and Mechanical Properties. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2019. (In Chinese)

- GB/T 228.1-2021; Metallic Materials-Tensile testing-Part 1: Method of Test at Room Temperature. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2021. (In Chinese)

- GB/T 50152-2012; Standard for Test Methods of Concrete Structures. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2012. (In Chinese)

- Newmark, N. Closure of “Numerical Procedure for Computing Deflections, Moments, and Buckling Loads”. Trans. Am. Soc. Civ. Eng. 1943, 108, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.W.; Cui, G.Z.; Kishiki, S. Cyclic elasto-plastic behaviour of replaceable ductile Split-T located at the bottom beam flange. Eng. Struct. 2024, 303, 117506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, L.; Zanini, M.A.; Faleschini, F.; Toska, K.; Pellegrino, C. Seismic behavior of precast reinforced concrete column-to-foundation grouted duct connections. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2021, 19, 5191–5218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Part | fcu | fc | ft | E |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Column | 51.3 | 39.0 | 3.5 | 35,770.8 |

| Pedestal | 46.0 | 35.0 | 3.3 | 33,854.7 |

| Foundation | 45.6 | 34.7 | 3.2 | 33,772.7 |

| Diameter (mm) | δ (%) | fy (MPa) | ft (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 16.0 | 473 | 645 |

| 14 | 17.5 | 433 | 621 |

| 16 | 15.0 | 443 | 630 |

| Method | Part | K (kN/mm) | Fy (kN) | Δy (mm) | μ | Fmax (kN) | Δmax (mm) | Fu (kN) | Δu (mm) |

| Geometric Graphic Method | West column | 78.25 | 499.80 | 10.08 | 7.14 | 574.17 | 24.95 | 484.32 | 72.00 |

| East Column | 86.60 | 567.62 | 10.80 | 6.42 | 682.83 | 37.42 | 580.44 | 69.32 | |

| Equivalent Elasto-Plastic Energy Method | West column | 78.25 | 502.26 | 10.20 | 7.06 | 574.17 | 24.95 | 484.32 | 72.00 |

| East Column | 86.60 | 575.43 | 11.37 | 6.09 | 682.83 | 37.42 | 580.44 | 69.32 | |

| Park Method | West column | 78.25 | 498.96 | 10.03 | 7.18 | 574.17 | 24.95 | 484.32 | 72.00 |

| East Column | 86.60 | 570.49 | 10.86 | 6.38 | 682.83 | 37.42 | 580.44 | 69.32 | |

| Mean | West column | 78.25 | 500.34 | 10.10 | 7.13 | 574.17 | 24.95 | 484.32 | 72.00 |

| East Column | 86.60 | 571.18 | 11.01 | 6.30 | 682.83 | 37.42 | 580.44 | 69.32 |

| Method | K (kN/mm) | Fy (kN) | Δy (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geometric Graphic Method | 101.83 | 1575.71 | 35.54 |

| Equivalent Elastic-Plastic Energy Method | 101.83 | 1715.79 | 41.05 |

| Park Method | 101.83 | 1849.18 | 46.16 |

| Mean | 101.83 | 1713.55 | 40.92 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jin, X.; Chen, Z.; Li, H.; Kong, J.; Hou, G.; Miao, X.; Sun, L. Experimental Study on the Mechanical Performance of Cast-in-Place Base Joints for X-Shaped Columns in Cooling Towers. Buildings 2026, 16, 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010174

Jin X, Chen Z, Li H, Kong J, Hou G, Miao X, Sun L. Experimental Study on the Mechanical Performance of Cast-in-Place Base Joints for X-Shaped Columns in Cooling Towers. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):174. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010174

Chicago/Turabian StyleJin, Xinyu, Zhao Chen, Huanrong Li, Jie Kong, Gangling Hou, Xingyu Miao, and Lele Sun. 2026. "Experimental Study on the Mechanical Performance of Cast-in-Place Base Joints for X-Shaped Columns in Cooling Towers" Buildings 16, no. 1: 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010174

APA StyleJin, X., Chen, Z., Li, H., Kong, J., Hou, G., Miao, X., & Sun, L. (2026). Experimental Study on the Mechanical Performance of Cast-in-Place Base Joints for X-Shaped Columns in Cooling Towers. Buildings, 16(1), 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010174