1. Introduction

To fulfill functional requirements such as structural lighting and ventilation, inclined columns are frequently employed as primary supporting elements. To enhance the mechanical properties and seismic performance of these inclined columns, steel can be integrated into the concrete, resulting in a steel-concrete composite structure. This approach maximizes the benefits of high bearing capacity, favorable deformation characteristics, robust seismic performance, as well as fire resistance and corrosion resistance [

1,

2,

3]. Consequently, it is suitable for promotion and application in multi-layer, long-span, and uniquely shaped structures located in earthquake-prone regions [

4,

5,

6].

Recent research has yielded numerous beneficial insights into the seismic behavior of steel-reinforced concrete columns. Yang [

7] and Xue [

8] developed two innovative types of prefabricated steel reinforced concrete columns: one being partially prefabricated and the other consisting of prefabricated hollow steel reinforced concrete columns. The influence of cross-sectional shape, stirrup spacing, axial compression ratio, cast-in-place concrete strength, and other factors on the seismic behavior of columns was investigated through quasi-static tests conducted on ten column specimens. The findings revealed that the hysteretic behavior of certain prefabricated steel reinforced concrete columns, in terms of performance, strength degradation, ductility, and energy dissipation, is superior to that of prefabricated hollow steel reinforced concrete columns. Leveraging plastic stress theory, this research presents a calculation technique for determining the bending and shear bearing capacity of the two innovative types of steel columns. This method offers an effective predictive framework for their practical engineering design and application. Zhao [

9] examined the restraining mechanism and effects of steel and hoop stirrups on concrete, segmenting the concrete within the steel-concrete column into four distinct areas. Utilizing the Mander model [

10], he proposed a theoretical framework for the stress–strain relationship in each concrete area, which offers valuable theoretical guidance for the refined numerical model analysis of steel-concrete columns. Dong [

11] extended the restraint mechanism of section steel and steel bars to high-strength recycled concrete columns. He calculated the cracking, yielding, and peak loads of the concrete, which correlated well with the experimental results. Liu [

12] conducted a scaled model test on a 2-span, 5-story steel-concrete special-shaped column space frame structure to investigate its seismic performance. The results suggest that the structure follows the design concept of “strong columns and weak beams,” displaying remarkable energy dissipation and deformation capacities, along with substantial collapse resistance. The evaluation of the space frame’s seismic performance utilized the OpenSees 3.3 platform. Additionally, the findings from the numerical analysis indicate that an increase in both the aspect ratio and the axial compression ratio of the column limbs can improve the bearing capacity and stiffness of the special-shaped frame, although this may lead to a reduction in ductility. Ma [

13] reached conclusions similar to those of Liu [

12] regarding the steel high-strength concrete frame, which follows the concepts of robust columns and vulnerable beams, along with strong joints and weaker components. Additionally, Ma determined the limit of the axial compression ratio to be 0.75. Gautham [

14] utilized the software ABAQUS 2021 to carry out a parametric study on steel-reinforced concrete columns. The results revealed that increasing the hoop ratio and steel ratio significantly improves both the displacement ratio and the lateral displacement of the column at failure, leading to a change in the failure mode from shear to bending. Furthermore, a predictive method for assessing the interaction response of axial load and bending moment concerning bearing capacity was introduced. In comparison to the results obtained from the design principles outlined in Eurocode 4 (2004) and AISC 360-16 (2016) design guidelines, it was observed that Eurocode 4 (2004) adversely affects column bending failure, while the proposed prediction method for carrying capacity demonstrates greater reliability. Wang [

15] conducted an analysis of the damage test outcomes for steel-reinforced concrete columns that were exposed to low cyclic reciprocating loads. He combined mechanical analysis with regression analysis to summarize a simplified three-line skeleton curve model for the columns. Additionally, a cyclic damage index was established to reflect the performance degradation of the columns. Furthermore, a multi-line hysteresis model for steel-reinforced concrete columns was developed, which can accurately predict their cyclic response. The research findings indicate that the incorporation of steel within concrete columns can effectively leverage the advantages of both materials. These composite steel-concrete columns show a considerable improvement in load-carrying capacity, stiffness, and ductility.

With the improvement of the national economic level, residents have increasingly higher expectations for the esthetics of buildings. Designers may incorporate inclinations into the columns of structures for esthetic enhancement, thereby improving the architectural space and overall visual appeal. Additionally, irregular architectural styles and steeply inclined columns have gradually been adopted in actual construction projects [

16,

17,

18]. Due to the presence of the inclination angle, the mechanical properties and seismic performance of inclined columns differ from those of vertical columns. For instance, Hassan [

19] conducted an analysis on how the angle of inclination affects the stiffness and strength of columns. The findings indicated that as the inclination angle increases, there is a corresponding decrease in both the axial stiffness and strength of the column, with a greater reduction in strength observed at higher inclination angles. Allouzi [

20] developed nonlinear finite element models for three double-layer concrete-filled steel tube columns that had different inclination angles. The study revealed that as the inclination angle rises, the maximum bearing capacity of the columns diminishes. After quantifying this relationship, double-layer columns were analyzed, leading to the formulation of a column compressive strength prediction formula that effectively estimates the compression strength of inclined columns with angles ranging from 0° to 30°. Han [

21] and Ren [

22] conducted numerous vertical monotonic loading tests on short slanted concrete-filled steel tube columns. Their findings revealed that, as the angle of inclination rises, there is a slight reduction in the vertical load-bearing capacity of these columns. Building on Han’s experiments [

21], Lam [

23] extended the column inclination angle to a range of 0° to 15° through numerical simulations. He employed regression analysis to derive the reduction coefficient associated with the inclination angle and the compressive load-bearing capacity of short slanted concrete-filled steel tube columns. A linear relationship was established between these variables, which can accurately forecast the compressive load-bearing capacity of slanted columns. Hansapinyo [

24] investigated the mechanical characteristics of hollow steel tubes filled with concrete, specifically focusing on columns that are inclined and subjected to vertical reciprocal loads. The study found that the angle of inclination significantly reduces the vertical compressive load-bearing capability of these columns; however, filling them with concrete or thickening the steel tube wall can substantially alleviate the negative impact of the inclination on their bearing capacity. Zhang [

25] proposed a theoretical estimation model for the shear strength of inclined column-beam joints, which is founded on the softened tension and compression rod model. The findings reveal that the column inclination angle influences the initial shear force at the joint, leading to variations in the joint’s stress under both positive and negative loading conditions. Notably, the mechanical properties are contingent on the inclination direction: the shear strength increases in the direction of inclination while decreasing in the opposite direction. Furthermore, a larger inclination angle correlates with a more significant strength effect. In summary, the column inclination angle can diminish the compression or shear bearing capacity of the component to varying extents. However, in practice, steel-reinforced concrete inclined columns (SRCIC) are typically designed using the same procedures as conventional vertical columns. To date, there has been limited research on the seismic performance of SRCIC under cyclic loading. To enhance the safety of inclined column structures, further investigation is required regarding the seismic behavior of SRCIC when subjected to the simultaneous influences of vertical pressure and lateral cyclic loading.

This research investigates the seismic performance of highly inclined SRCIC and steel reinforced concrete vertical column (SRCVC) through a quasi-static test. Based on the results of the quasi-static test, a finite element analysis model was established. Utilizing this validated and robust finite element model, a parametric analysis was conducted on various factors, including inclination angle, steel ratio, reinforcement ratio, and stirrup ratio. The resulting changes in the ductility coefficient were systematically summarized, thereby enhancing the theoretical framework for SRCIC and offering theoretical guidance for their application in practical engineering projects.

3. Experimental Analysis and Discussion

3.1. Failure Progression

The phenomenon of damage observed in the specimen is concentrated within 200 mm from the base of the column.

Figure 4 illustrates the main milestones and key points of damage at the base of the specimen throughout the loading procedure. The failure process of SRCIC-11 resembles that of SRCIC-18. When the drift ratio

reaches 1.5%, a transverse main crack emerges in the concrete on the specimen’s north side due to tensile stress. As the drift ratio increases, this transverse main crack extends toward the east and west sides, while new horizontal and vertical cracks continue to develop, forming a network. When the drift ratio

reaches 3.5% to 4.0%, portions of the concrete are compromised by the network of cracks, gradually breaking and falling off. The concrete on the north side exhibits typical bending failure characteristics. Conversely, there are no notable cracks detected in the concrete on the south side of the specimen at

= 1.5%. When

increases to 2.5%, no major cracks are evident on the south side, although several areas of broken concrete appear. As the drift ratio continues to rise, the area of the crushing zone expands. By the time the drift ratio

reaches 3.5% to 4.0%, several broken concrete areas merge into a single piece, resulting in complete concrete failure and detachment, exposing the longitudinal bars. Consequently, the specimen’s load-bearing ability is diminished, and the concrete on the south side exhibits characteristics of compression failure. Therefore, due to the influence of the inclination angle, the combined effects of vertical pressure and lateral reciprocating push-pull forces lead to a failure mechanism characterized by bending failure on the northern side and compression failure on the southern side.

SRCVC-0 exhibits distinct failure processes, with similar concrete failure mechanisms observed on both the north and south sides. When the drift ratio reaches 2.5%, a transverse main crack first appears approximately 100 mm from the base of the column. As the drift ratio increases, this main crack extends from east to west, and numerous transverse and vertical cracks continue to develop, resulting in a dense network of cracks. The concrete becomes fragmented due to this network of cracks, and by the time the drift ratio reaches 5.0%, the concrete is completely shattered and has fallen off, rendering it incapable of bearing any load. Both the northern and southern sides of the specimen exhibit typical bending failure characteristics.

The specimens designed for this study are primarily subjected to bending failure; however, the failure modes of SRCIC differ from those of SRCVC. SRCIC exhibits an initial eccentricity,

, as illustrated in

Figure 5. Consequently, the concrete on the north side experiences rapid failure due to the combined effects of tensile stress from the lateral load

P and vertical pressure

N. Specifically, when the drift ratio is relatively small (

= 1.5%), a transverse bending main crack develops. In contrast, SRCVC lacks initial eccentricity

, resulting in a smaller tensile stress from the vertical pressure

N when the drift ratio is still relatively small. As a result, SRCVC primarily relies on the tensile stress generated by the lateral load

P, leading to a slower failure process compared to SRCIC. When

reaches 2.5%, lateral main cracks begin to appear. Similarly, under the combined effects of compressive stress from lateral load

P and vertical pressure

N, the concrete on the south side of SRCIC does not exhibit significant transverse main cracks, remaining predominantly under compression. However, the stress distribution between the concrete on the south and north sides of SRCVC is completely symmetrical, leading to the appearance of transverse main cracks due to the tensile stress induced by the lateral load

P.

Due to the combined effects of lateral load

P and vertical pressure

N, which accelerate the concrete damage process, SRCIC loses its bearing capacity at a drift ratio of 4.0%. In contrast, SRCVC can continue to bear load until the drift ratio reaches 5.0%. This exceeds the elastoplastic drift ratio limit specified in specification GB50011-2010 [

28]. This finding demonstrates that the deformation capacity of SRCIC under earthquake action is inferior to that of SRCVC. Nevertheless, SRCIC still exhibits good plastic deformation ability and can be effectively utilized in structures located in earthquake-prone areas.

3.2. Second-Order Effect

The bending member experiences significant lateral displacement when subjected to earthquake forces. Consequently, the actual bending moment experienced by the member section increases, resulting in a second-order effect. This second-order effect diminishes the load-bearing capacity and stability of the column, highlighting the necessity to investigate the second-order effects of SRCIC. The study adopts a quasi-static cyclic loading method based on existing research results [

7,

11], which has practical advantages of controllable operation and strong repeatability. This method can effectively separate dynamic factors such as load history and inertial coupling, thereby clearly quantifying the influence mechanism of second-order effects on the basic performance of structures, providing direct and reliable basis for design and evaluation. Although it is difficult to fully simulate dynamic phenomena such as high-frequency and cumulative effects in ground motions, the conclusions obtained still have important engineering benchmark value.

The loading process of SRCIC is depicted in

Figure 5, which shows the stress and deformation involved. In this figure, the constant vertical pressure is denoted as

N, the lateral reciprocating push-pull load is represented as

P, the inclination angle of the inclined column is

, the effective height is

, the initial displacement caused by the inclination angle is

, and the lateral reciprocating displacement during loading is

. Based on static balance analysis, it is essential to ensure that the bending moment at the column’s base is balanced, resulting in the formulation of the subsequent balance equation:

Bending moment equilibrium equation without considering the second-order effect:

Bending moment equilibrium equation considering second-order effect:

In Formulas (3) and (4),

represents the first-order bending moment effect, while

and

denote the second-order bending moment effects resulting from northward and southward loading, respectively. During the loading process, the lateral reciprocating displacement

continues to change as the drift ratio increases. Consequently, only the ratios of the second-order to first-order bending moments at the three characteristic points (yield, peak, and failure) are calculated, as shown in

Table 1.

Table 1 shows that at both the yield and peak points, the ratio of the second-order bending moment to the first-order bending moment for the specimen is approximately 5%, suggesting that the second-order effect has a minimal impact. However, as the drift ratio increases, the impact of the second-order effect becomes significantly more pronounced. At the failure point, the second-order effect reaches about 10%, indicating that it can no longer be disregarded. Furthermore, the inclination angle of the inclined column exacerbates the second-order effect of the specimen when subjected to northward loading, while it mitigates the second-order effect during southward loading, demonstrating an asymmetrical behavior. This asymmetry is a primary reason why the inclined column experiences bending damage on the front side and compression on the back side.

In Equations (1)–(4),

and

are the lateral loads of the specimen without considering and considering second-order effects, respectively. By substituting the column end bending moment

M in Equations (3) and (4) into Equations (1) and (2), we can obtain:

According to Equations (5) and (6),

In Equation (7), represents the improvement coefficient of the lateral load-bearing capacity of the specimen, excluding the influence of the second-order bending moment effect. It indicates that, in practical engineering applications, the presence of the second-order effect diminishes the lateral load-bearing capacity of the component. To account for this influence, the strength reduction coefficient is defined as .

By substituting Equation (7) into the strength reduction coefficient

, we can derive the necessary results:

By substituting the experimentally measured values at the three characteristic points into Equations (7) and (8), one can compute the lateral load-bearing capacity improvement coefficient

and the strength reduction coefficient

of the specimen, as presented in

Table 2.

Table 2 demonstrates that as the drift ratio increases, both the lateral load-bearing capacity improvement coefficient

and the strength reduction coefficient

of the specimen exhibit an upward trend. Notably, at the failure point, both

and

approach 10%, indicating that during the declining stage, the second-order effect accelerates the damage process of the specimen. However, in conjunction with the definitions and derivation processes of

and

, inclination angle of the specimen does not influence the values of

and

.

3.3. Horizontal Load vs. Drift Ratio Response

Figure 6 illustrates the response curve (i.e., hysteresis curve) of the horizontal load and drift ratio for each specimen. Both SRCIC and SRCVC demonstrate commendable hysteretic performance. In comparison to the hysteretic curve of reinforced concrete columns, only a minor pinching phenomenon is observed [

29], indicating that the inclusion of section steel in the specimens significantly enhances the hysteretic performance of the columns, enabling them to withstand strong earthquakes. Additionally,

Figure 6 highlights the concrete crack point, yield point, peak point, and failure point of the specimens. It reveals that prior to concrete cracking, the horizontal load and drift ratio exhibit a nearly linear relationship, suggesting that the specimens remain in the elastic stage. As the drift ratio increases, the specimens transition into the elastic-plastic phase, where cracks propagate and develop, resulting in a decrease in stiffness while simultaneously producing plasticity. After surpassing the peak point, the specimens gradually enter the failure stage, characterized by a substantial reduction in stiffness, a significant increase in plastic deformation, and a widening of the hysteresis loop, until either the concrete completely fails or the longitudinal reinforcement yields, thereby reaching the failure point.

In contrast, SRCIC exhibits hysteretic performance that differs from that of SRCVC. The hysteresis curve of SRCVC is approximately centrally symmetrical around the origin, whereas the hysteresis curve of SRCIC is distinctly asymmetric. The area of the hysteresis curve corresponding to northward loading (i.e., the segment of the curve located above ) is significantly larger than that for southward loading (i.e., the segment of the curve situated below ). To conveniently quantify the degree of asymmetry in inclined columns with varying inclination angles, we define the asymmetry coefficient as the ratio of the peak horizontal load applied in the north direction to that applied in the south direction. Calculations reveal that the asymmetry coefficients for SRCIC-11, SRCIC-18, and SRCVC-0 are 1.36, 1.73, and 1.03, respectively. This suggests that with a rise in the inclination angle, the asymmetry coefficient of the specimen also increases, thereby enhancing the hysteretic performance during northward loading while weakening it during southward loading. The failure mode of the specimen is primarily governed by the crushing of the concrete on the south side.

3.4. Deformation Capacity

The ability of a structure or component to deform under seismic forces can be assessed through the ductility coefficient

[

28]. Specifically,

is defined as

.

Table 3 displays the values obtained from tests and simulations for the ductility coefficient. In this table,

,

and

refer to the yield displacement, peak displacement, and failure displacement, respectively, while

,

and

denote the yield load, peak load, and failure load, respectively. Due to the absence of a distinct yield point in the specimen,

is typically determined using the energy equivalent method [

30,

31], as illustrated in

Figure 7. This method involves drawing a secant line on the skeleton curve to ensure that the areas of regions I and II are equal. The point where this secant line intersects the skeleton curve signifies the yield point. Furthermore,

is defined as 0.85 times

[

27], and the remaining characteristic parameters can be derived from

Figure 7.

The calculation results of the ductility coefficient reveal that the average ductility coefficients for the north and south sides of SRCVC-0 are 1.05 and 1.10 times greater than those of SRCIC-11 and SRCIC-18, respectively. This indicates that the inclination angle of the column adversely affects its ductility coefficient. Specifically, a greater inclination angle correlates with a lower ductility coefficient. Moreover, the reduction in ductility coefficient becomes increasingly pronounced with higher angles of inclination. Additionally, the northward ductility coefficients of SRCIC-11, SRCIC-18, and SRCVC-0 are 1.18, 1.44, and 1.13 times their respective southward ductility coefficients. This suggests that the reduction effect on the ductility coefficient is more pronounced in the southward loading direction. This phenomenon can be attributed to the bending failure characteristics exhibited by the north side of the inclined column, which retains good ductility, leading to a less significant reduction in the ductility coefficient. In contrast, the south side of the inclined column consistently experiences compressive stress during loading, which causes the concrete to crush and sustain damage at an earlier stage. This significantly reduces the stiffness of the specimen, thereby resulting in a marked decrease in the ductility coefficient.

3.5. Dissipated Energy

Energy dissipation serves as an essential measure for assessing the seismic behavior of a structure or its components. This performance can be evaluated using parameters such as the equivalent viscous damping coefficient

[

27], the energy consumption

of each cycle, and the cumulative energy consumption

. The equivalent viscous damping coefficient

is calculated using Equation (9).

In this formula,

represents the area contained within the hysteresis loop ABCD, while

denotes the sum of the areas of the triangles OBE and ODF, as demonstrated in

Figure 8.

Due to the varying inclination angles of the three specimens, the number of displacement cycles at final failure is inconsistent.

Figure 9 illustrates the curve that represents the relationship between the equivalent viscous damping coefficient

and the number of displacement cycles

. The curve exhibits an overall upward trend following the cracking of the specimen, indicating its transition into the elastic-plastic stage. The energy consumption of all specimens gradually increases with the drift ratio

, and at the point of failure, the

for each specimen reaches 0.30. Notably, this value of

surpasses that of conventional reinforced concrete columns, which typically ranges from 0.1 to 0.2 [

32]. This observation highlights the superior energy dissipation performance of SRCIC.

Figure 10 presents the energy consumption

for each displacement cycle throughout the loading process. The overall

-

curve displays a step-like rising pattern. Prior to cracking, the

-

curve remains relatively smooth, with energy consumption at a low level. Following cracking, the specimen promptly enters the elastic-plastic stage, resulting in a significant increase in energy consumption

. Even during the destruction phase, the energy consumption

continues to exhibit robust growth, indicating that the specimen possesses strong energy consumption capacity throughout the entire loading process. Under a consistent drift ratio

, as the number of displacement cycles

increases, the strength and stiffness of the specimen degrade, leading to a slight decrease in energy dissipation capacity, which is represented in a step-like manner. Furthermore, the

-

curve for the SRCIC-18 specimen consistently remains higher than those of the other two specimens. This is attributed to the larger inclination angle, which enhances the peak load value in the north direction, thus increasing the area of the hysteresis loop.

Figure 11 illustrates the relationship between the cumulative energy consumption

of each specimen across displacement cycles and the number of displacement cycles

. The

-

curves for all specimens exhibit a similar developmental trend, characterized by exponential growth. Prior to cracking, the cumulative energy consumption

of each specimen increases gradually. However, once the elastic-plastic stage is reached,

rises sharply with an increase in the number of displacement cycles, and the rate of increase becomes significantly pronounced. Consistent with the behavior of the

-

curve, the

-

curve for the SRCIC-18 specimen remains consistently higher than those of the other two specimens. It is important to note that SRCVC-0 has undergone 33 displacement cycles, whereas SRCIC-11 and SRCIC-18 have only experienced 28 displacement cycles. Consequently, upon final failure, the cumulative total energy consumption of SRCVC-0 was 1.69 and 1.34 times greater than that of SRCIC-11 and SRCIC-18, respectively. This indicates that the energy dissipation performance of vertical columns is superior to that of inclined columns. Nevertheless, the energy dissipation performance of inclined columns during each stage of the loading process is not inferior to that of vertical columns.

5. Numerical Investigation

Several factors influence the seismic performance of SRCIC, including inclination angle, steel ratio, reinforcement ratio, and stirrup ratio. An analysis comparing the test outcomes and simulation findings suggests that this finite element model effectively simulates the deformation capacity of SRCIC. Due to the large time and labor cost of experimental research, the finite element model can be used to analyze the influence of the above parameters on the seismic performance of SRCIC. The specific parameters selected for this analysis are as follows:

5.1. Inclination Angle

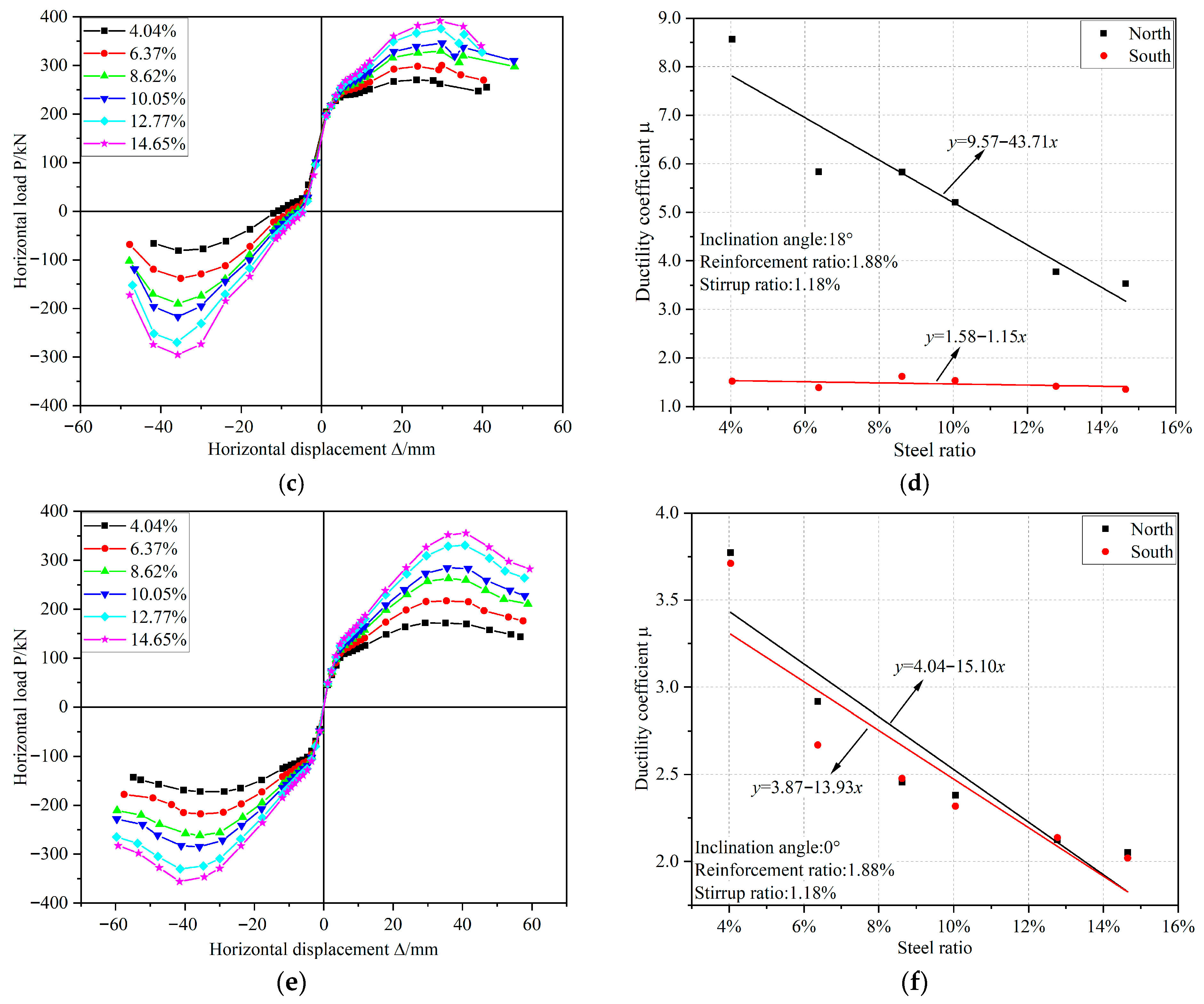

The test analysis results indicate that the column inclination angle significantly affects the failure mechanism and deformation capacity of SRCIC. Due to the test conditions, only specimens with inclination angles of 0°, 11° and 18° were produced. To further investigate the influence of additional inclination angles on the deformation capacity of SRCIC, specimens with angles of 3°, 6°, 9°, and 15° were included in the parameter analysis.

Figure 14a illustrates the skeleton curve at reference point 1 of the finite element model for various inclination angles. The trend of the curve indicates that as the inclination angle increases, the peak load in the north direction continues to rise, while the peak load in the south direction decreases. Concurrently, the asymmetry coefficient

increases, highlighting a more pronounced asymmetry, which aligns with the results of the experimental analysis. Furthermore, as depicted in

Figure 14b, the ductility coefficient for northward consistently increases, whereas the ductility coefficient for southward continues to decrease, exhibiting an approximately linear relationship with the inclination angle. This fitting formula can be employed to predict the ductility coefficient values of inclined columns at different inclination angles.

5.2. Steel Ratio

The steel sections of each test piece in the study were constructed from standard H-shaped steel. To ensure the appropriate thickness of the protective layer on the flange of the section steel and to maintain optimal joint performance between the section steel and concrete, the steel ratio in the specimen was kept relatively low. Typically, the steel ratio in steel reinforced concrete columns ranges from 4% to 15% [

26]. During the parameter analysis, the steel ratio was varied by adjusting the thickness of the steel web and flange. This included five different steel ratios, such as 4.04%, 6.37%, 10.05%, 12.77% and 14.65%, among others.

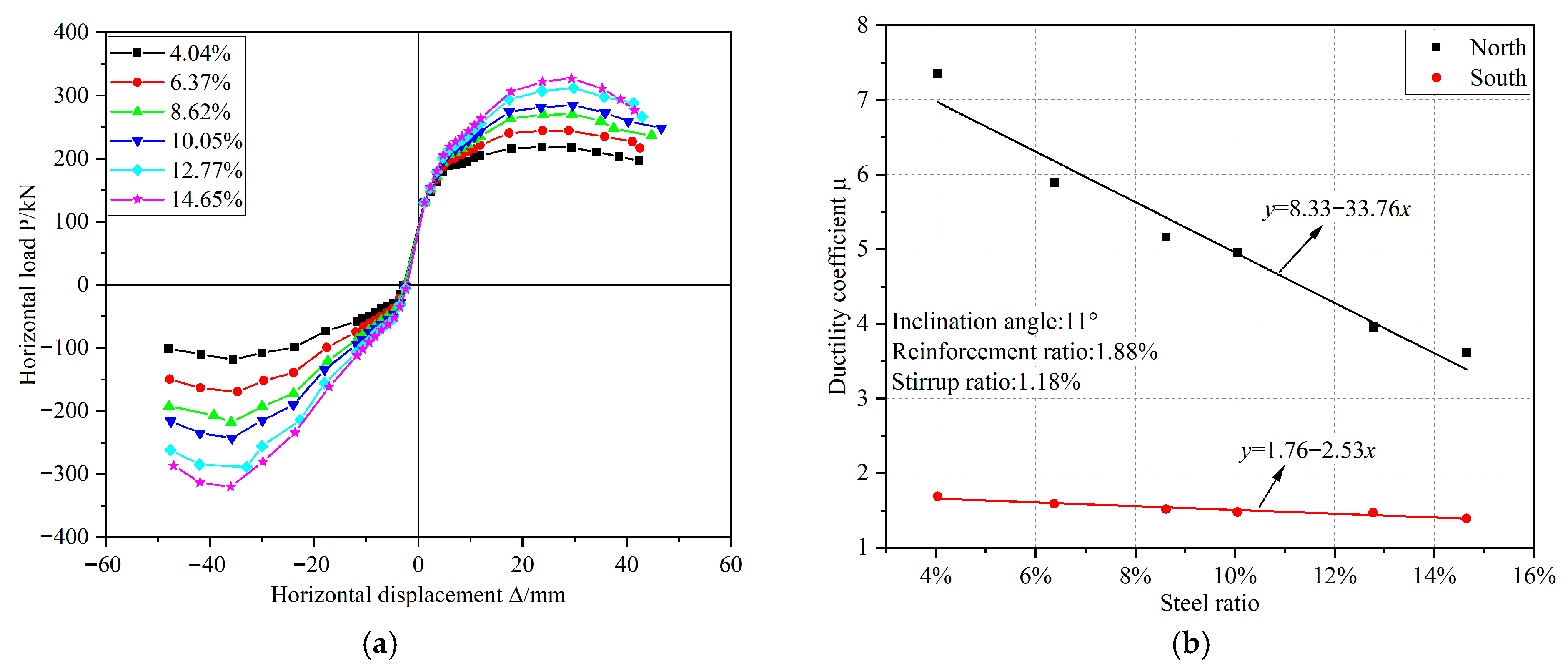

The skeleton curve for SRCIC-11, SRCIC-18, and SRCVC-0 at varying steel ratios, as illustrated in

Figure 15, indicate that increasing the steel ratio significantly enhances the peak load capacity. However, it is observed that the slope of the descending portion of the skeleton curve becomes steeper. Moreover, the ductility coefficient exhibits an overall decreasing trend with increasing steel ratio. This phenomenon can be attributed to the higher steel ratio, which increases the specimen’s stiffness and reduces the yield displacement. Although the steel may not yield when the specimen fails, the concrete sustains considerable damage, leading to an inability to support the load. Consequently, the failure displacement does not improve significantly, resulting in a decrease in the ductility coefficient.

5.3. Reinforcement Ratio

The longitudinal reinforcement ratio of steel reinforced concrete column is typically required to be no less than 0.8% [

26]. In the parameter analysis, the reinforcement ratio was varied by altering the number of longitudinal bars, resulting in three additional reinforcement ratios: 1.18%, 2.35%, and 3.53%.

As shown in

Figure 16, the peak load increases with the reinforcement ratio. However, the ductility coefficient of SRCIC decreases slightly, while that of SRCVC increases slightly. The overall change in these coefficients is not significant, indicating that the reinforcement ratio affects the column primarily in terms of bearing capacity, with a lesser impact on deformation capacity.

5.4. Stirrup Ratio

The restraining effect of stirrups significantly influences the load-bearing capacity and ductility of SRCIC. In the parameter analysis, the stirrup ratio was modified by adjusting the stirrup spacing, resulting in five distinct stirrup ratios: 1.04%, 1.39%, 1.67%, 2.08%, and 2.78%. This variation reflects the impact of different stirrup ratios.

Figure 17 illustrates that the stirrup ratio can marginally enhance the peak bearing capacity of SRCIC and SRCVC. However, this improvement is limited, and the effect on the ductility coefficient is also minimal. This phenomenon can be attributed to the restricted contribution of stirrups to the bending bearing capacity, as the specimens in this test were specifically designed for bending and compression failures. Additionally, the cross-shaped steel in the column exerts a significant restraining effect on the concrete, thereby diminishing the effectiveness of the stirrups in restraining the concrete.