Experimental and Numerical Study of the Seismic Behavior of Single-Plane Trussed CFSST Composite Column Frames

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Test Overview

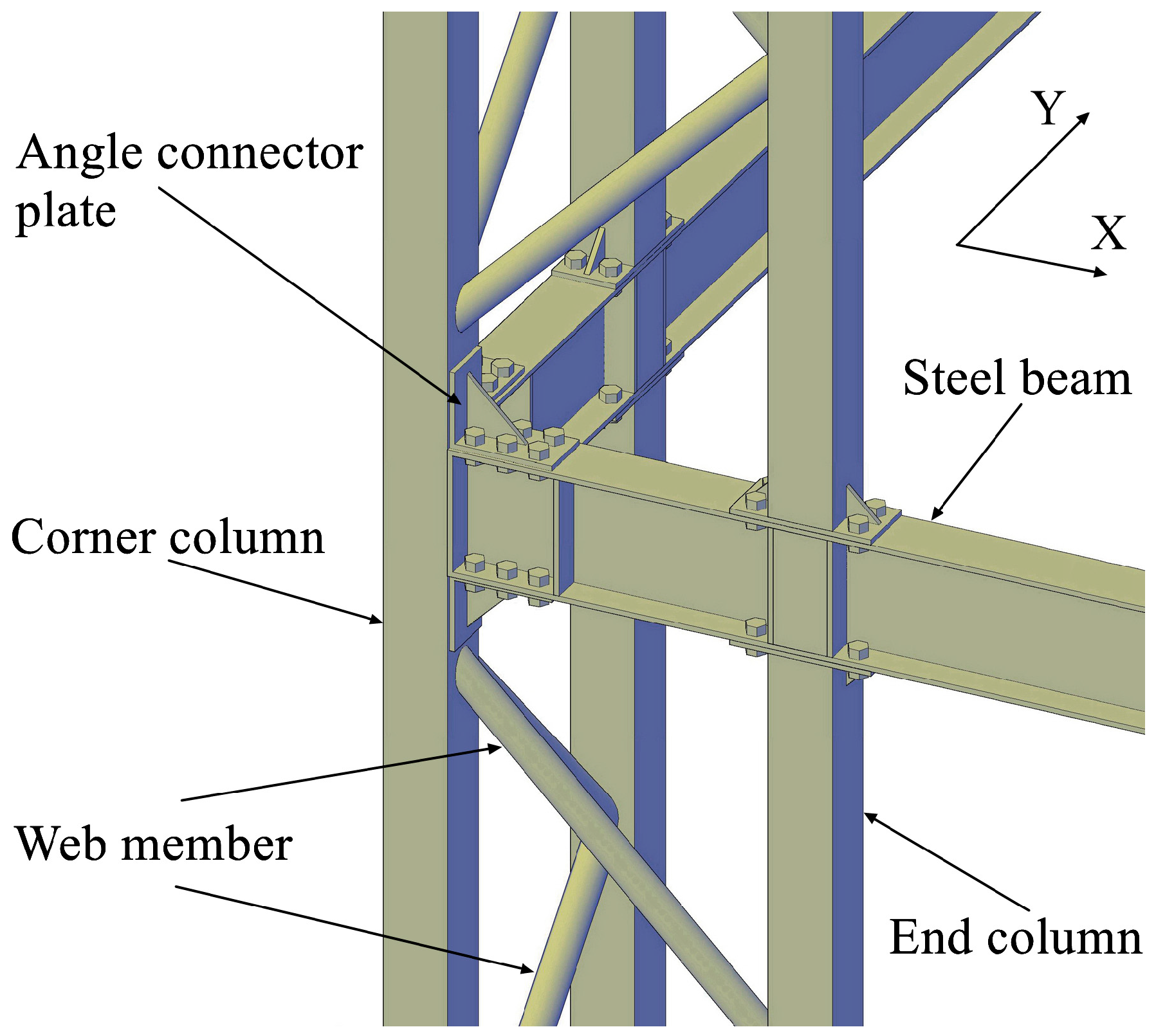

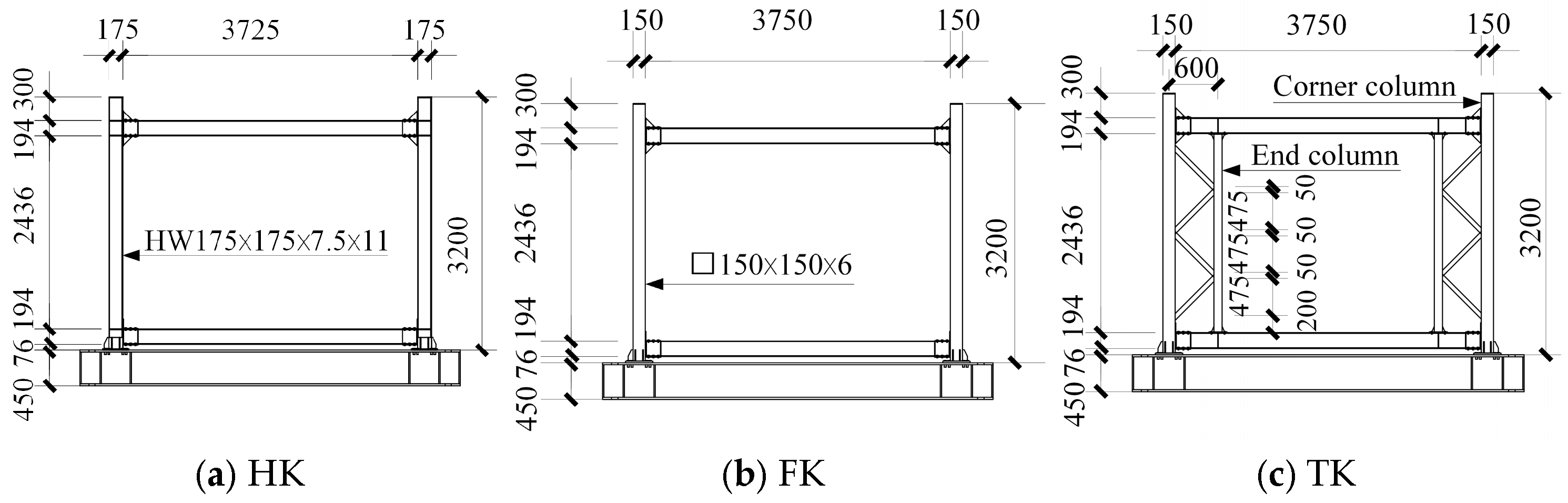

2.1. Specimen Design

2.2. Loading Scheme

2.3. Data Acquisition

3. Test Observations and Failure Processes

4. Test Results and Analysis

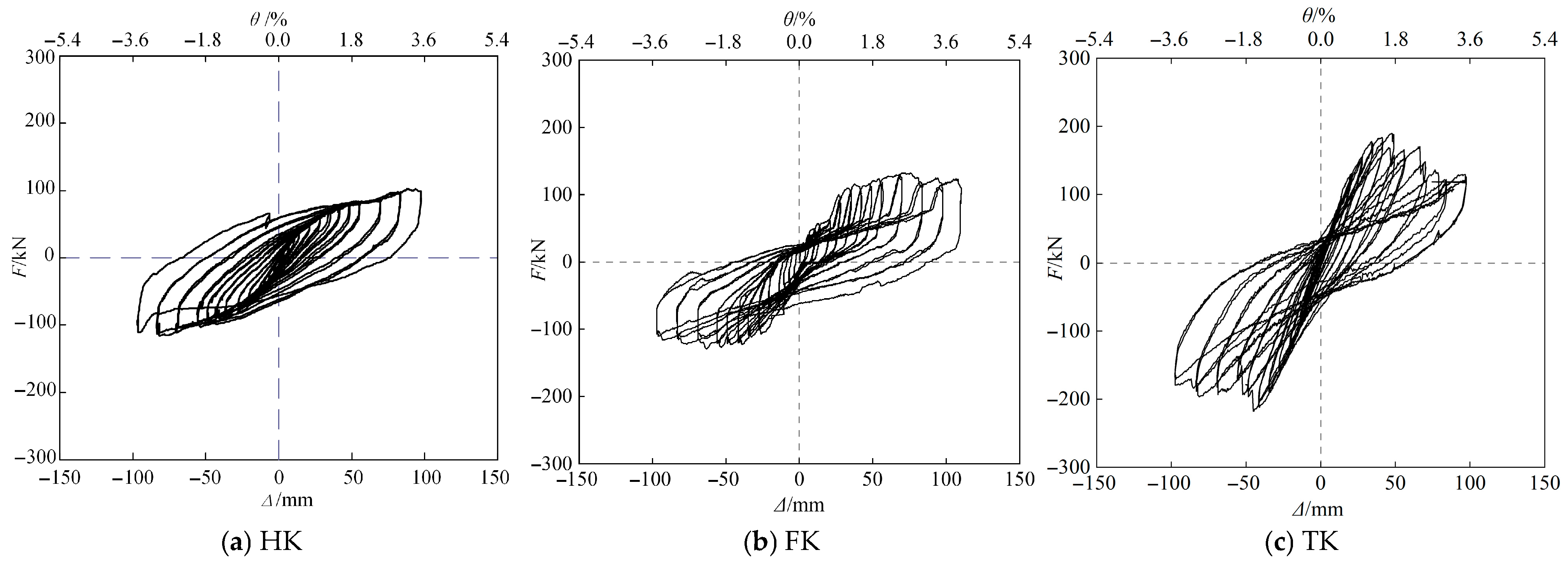

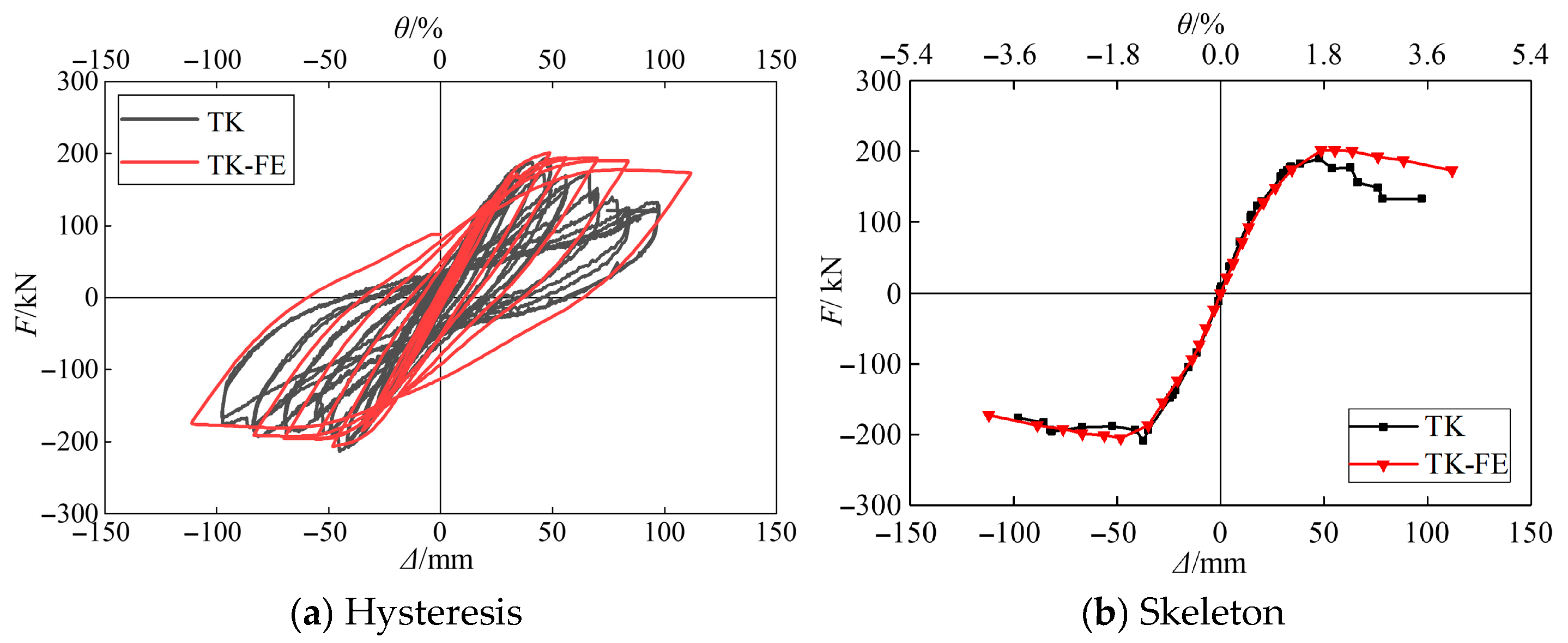

4.1. Hysteretic Curves

- (1)

- Specimen HK: The hysteretic curve exhibited a spindle-shaped and relatively full form. As θ increased, the slope of the line connecting the peak points of each hysteresis loop to the origin gradually decreased, indicating continuous stiffness degradation. After yielding, the load reduction was not pronounced.

- (2)

- Specimen FK: The hysteretic curve showed noticeable pinching. During the initial cycles, the load-carrying capacity increased rapidly, followed by a slower rate of increase and eventually a slight reduction near the ultimate load. The extended load plateau indicated that the specimen maintained a relatively high load-carrying capacity under large deformations, demonstrating a clear advantage over HK.

- (3)

- Specimen TK: The hysteretic curve displayed a reverse S-shaped form with moderate pinching. Although the steel consumption of TK was similar to that of HK, its initial stiffness and load-carrying capacity were substantially higher than those of HK and FK. After reaching the peak load, the load decreased in a stepped manner with only minor reductions. The specimen sustained a high load-carrying capacity even as deformation continued to increase.

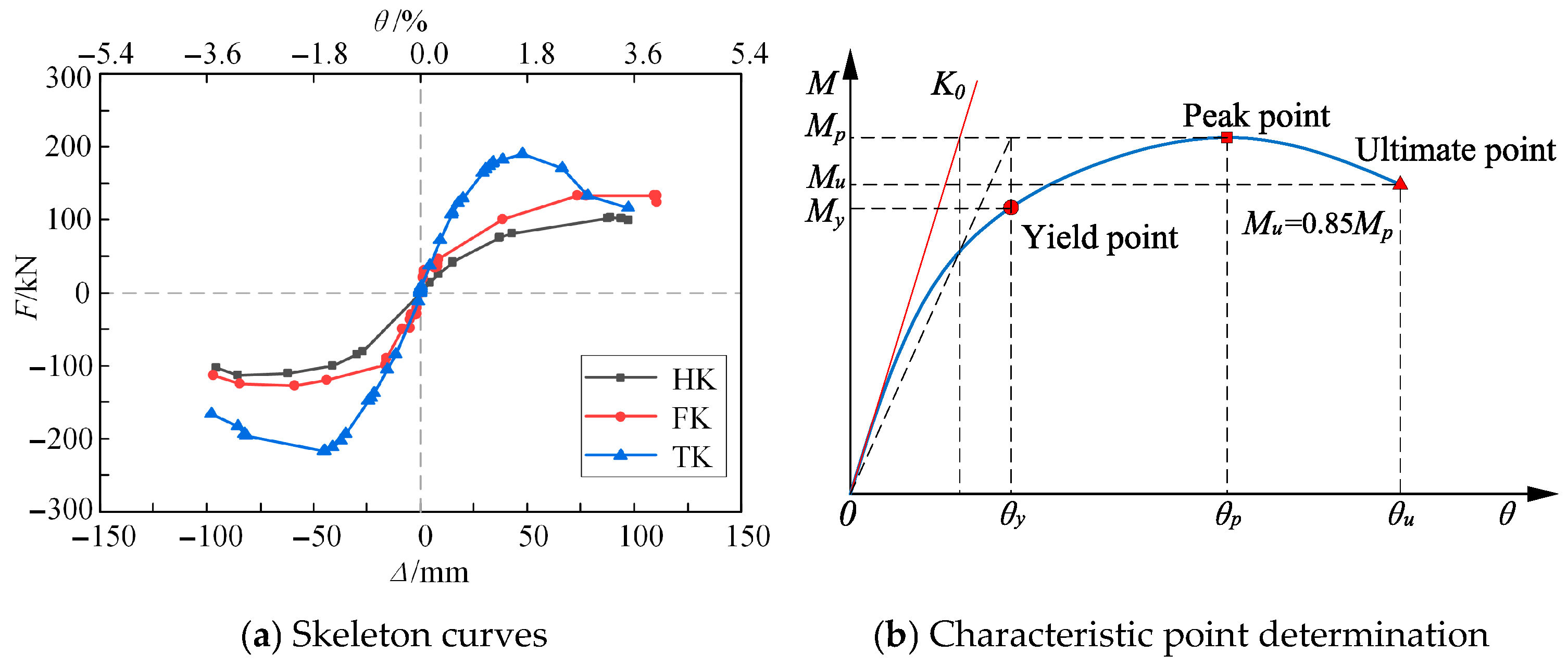

4.2. Skeleton Curves and Characteristic Points

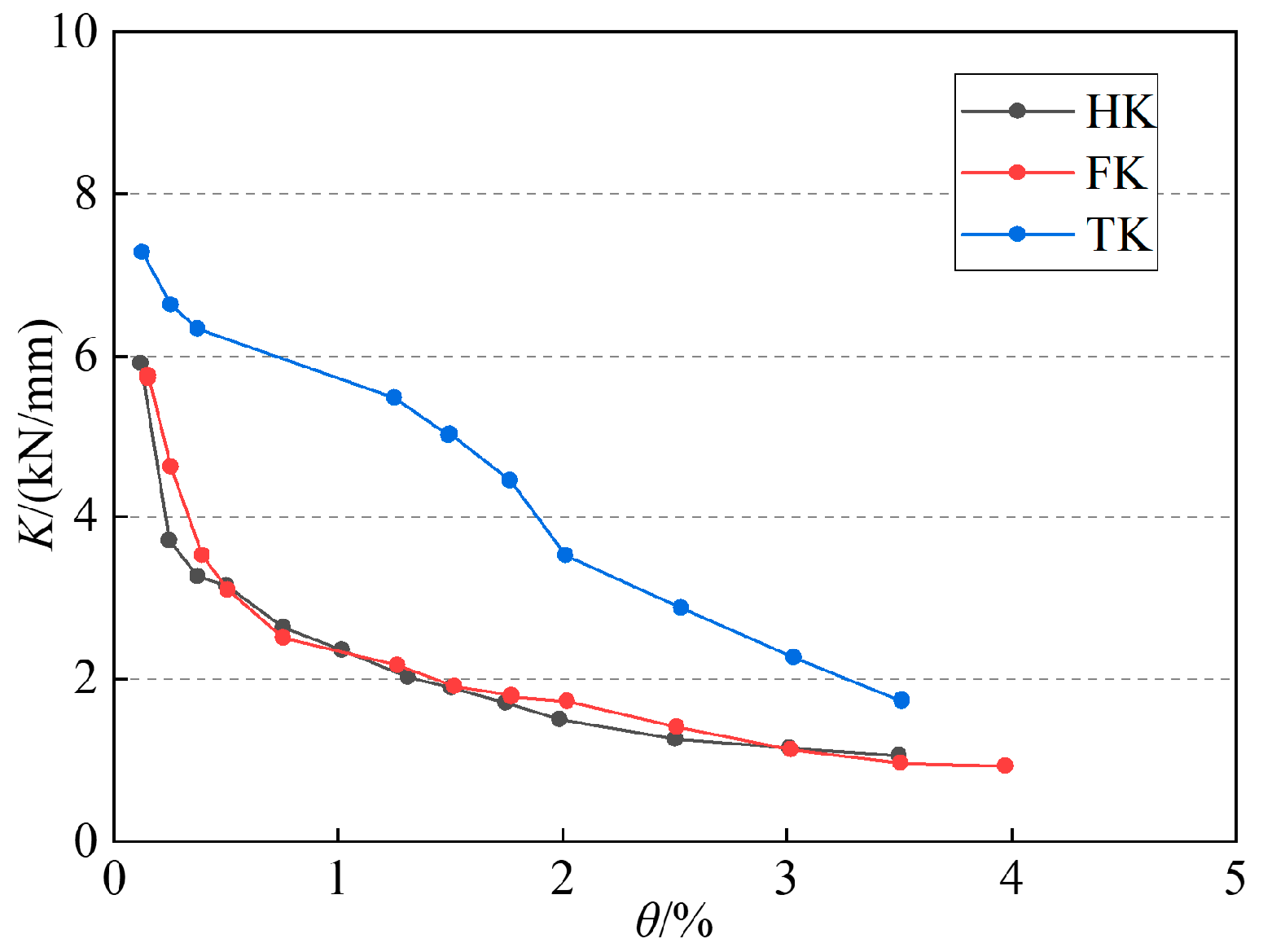

4.3. Stiffness Degradation

4.4. Deformation Capacity Analysis

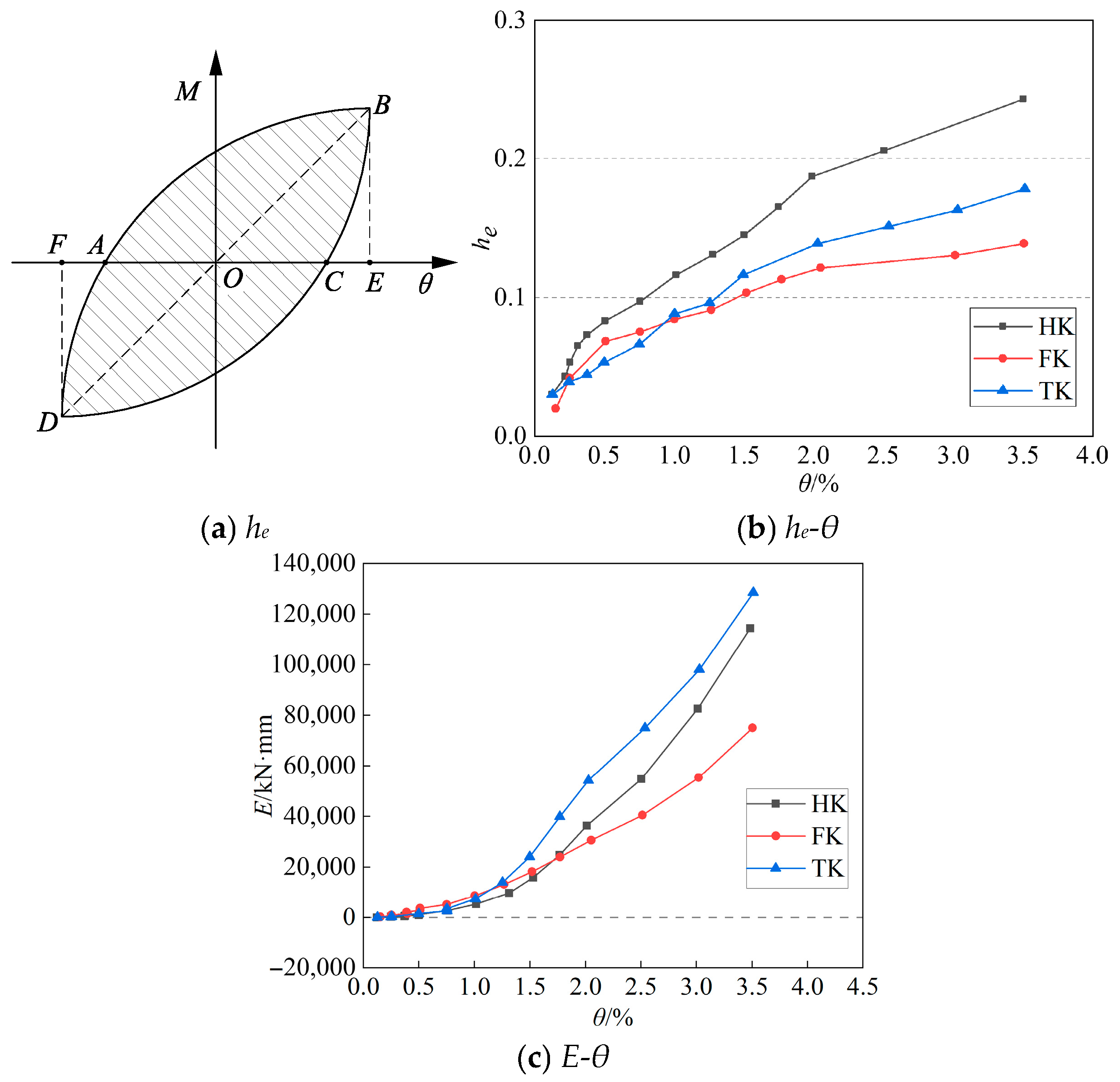

4.5. Energy Dissipation Capacity

5. FE Simulation

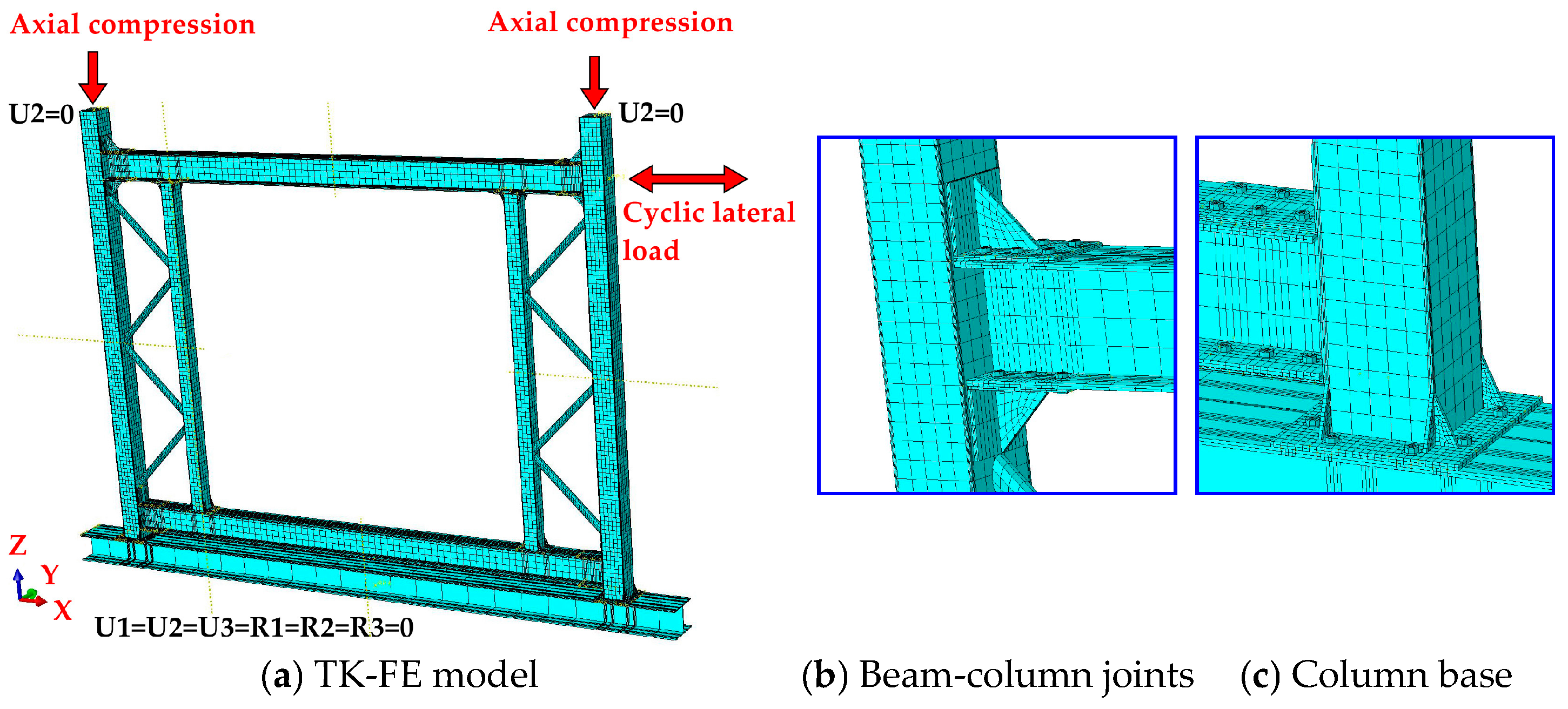

5.1. Modeling

5.1.1. Mesh Properties and Size

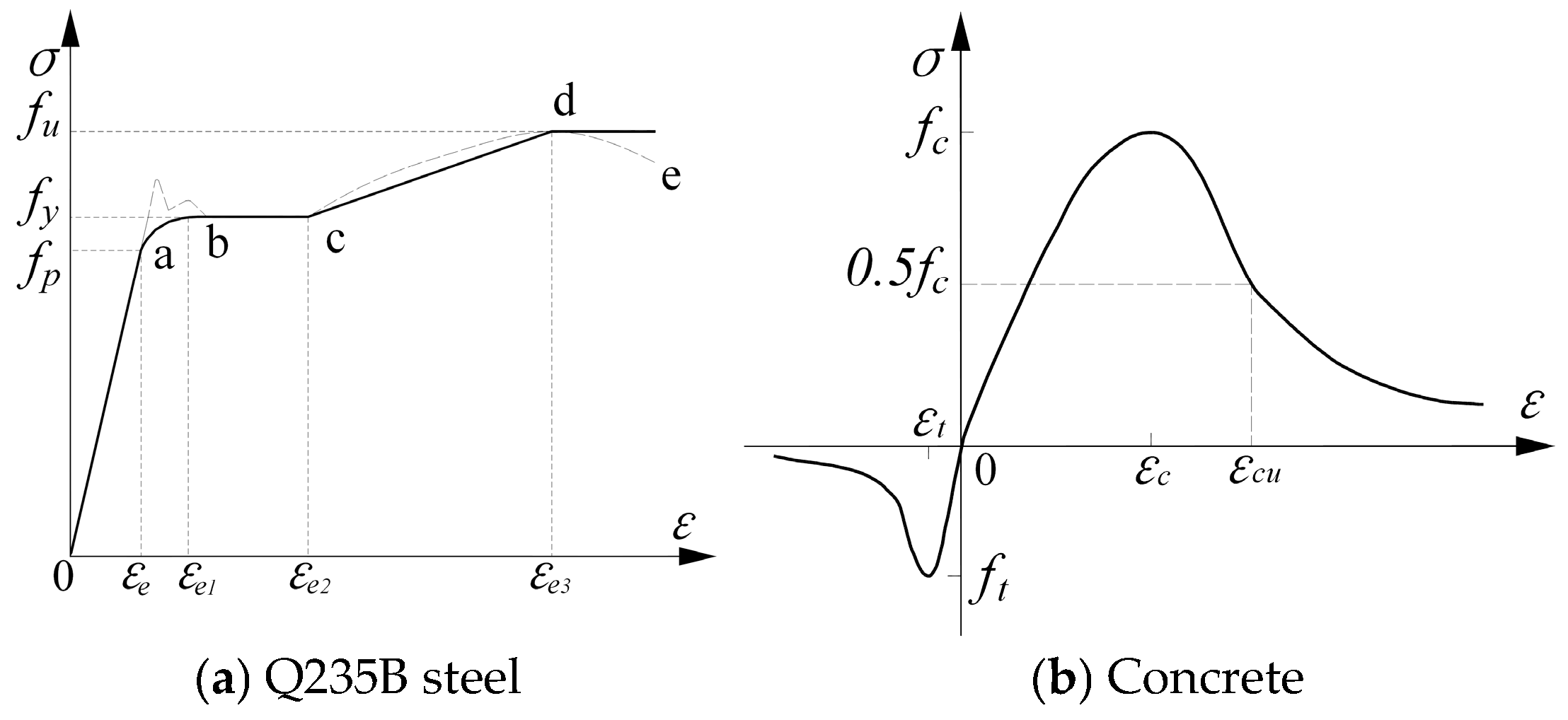

5.1.2. Stress–Strain Relationships

5.1.3. Interaction

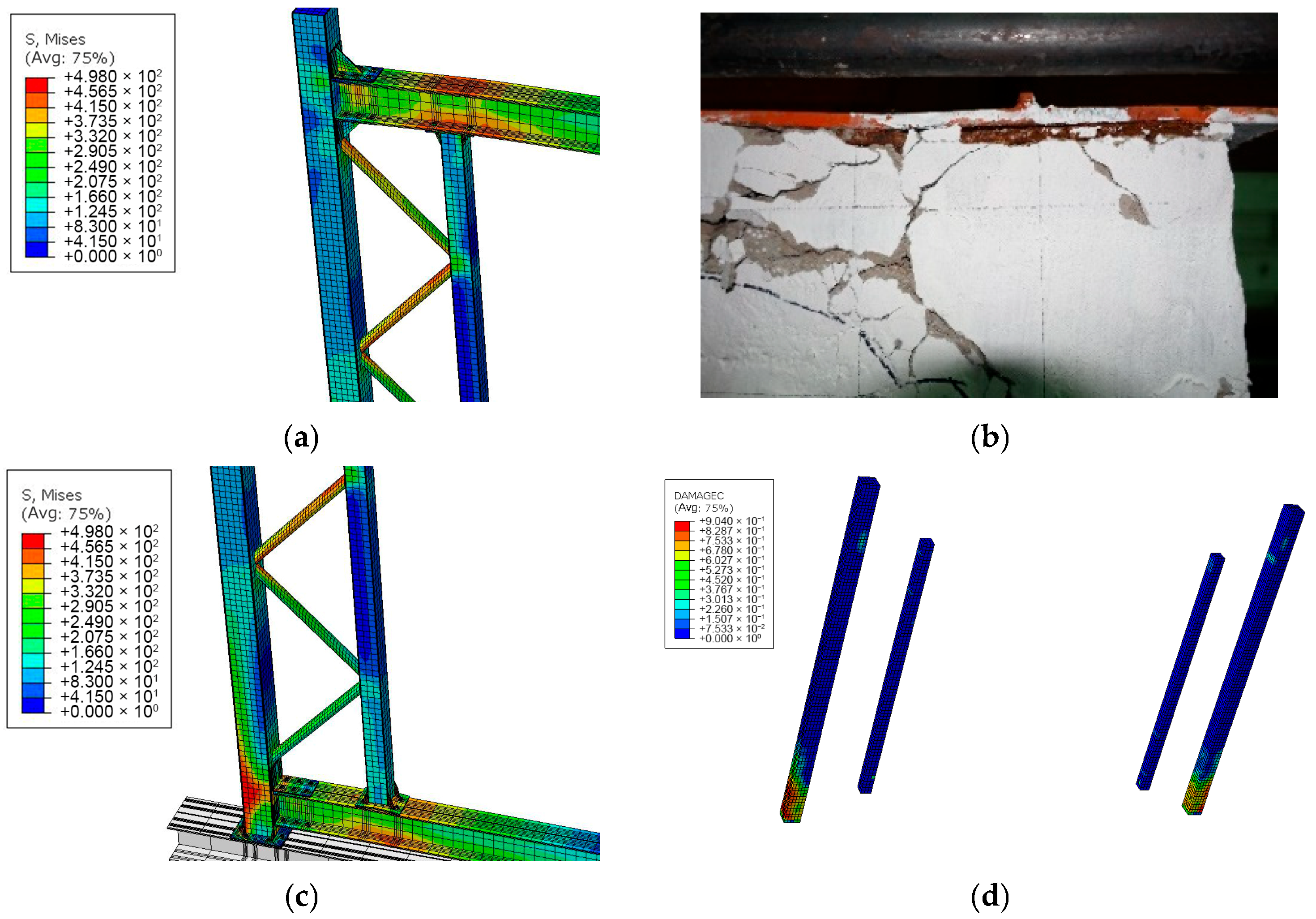

5.2. FE Model Verification

5.3. Parametric Analysis

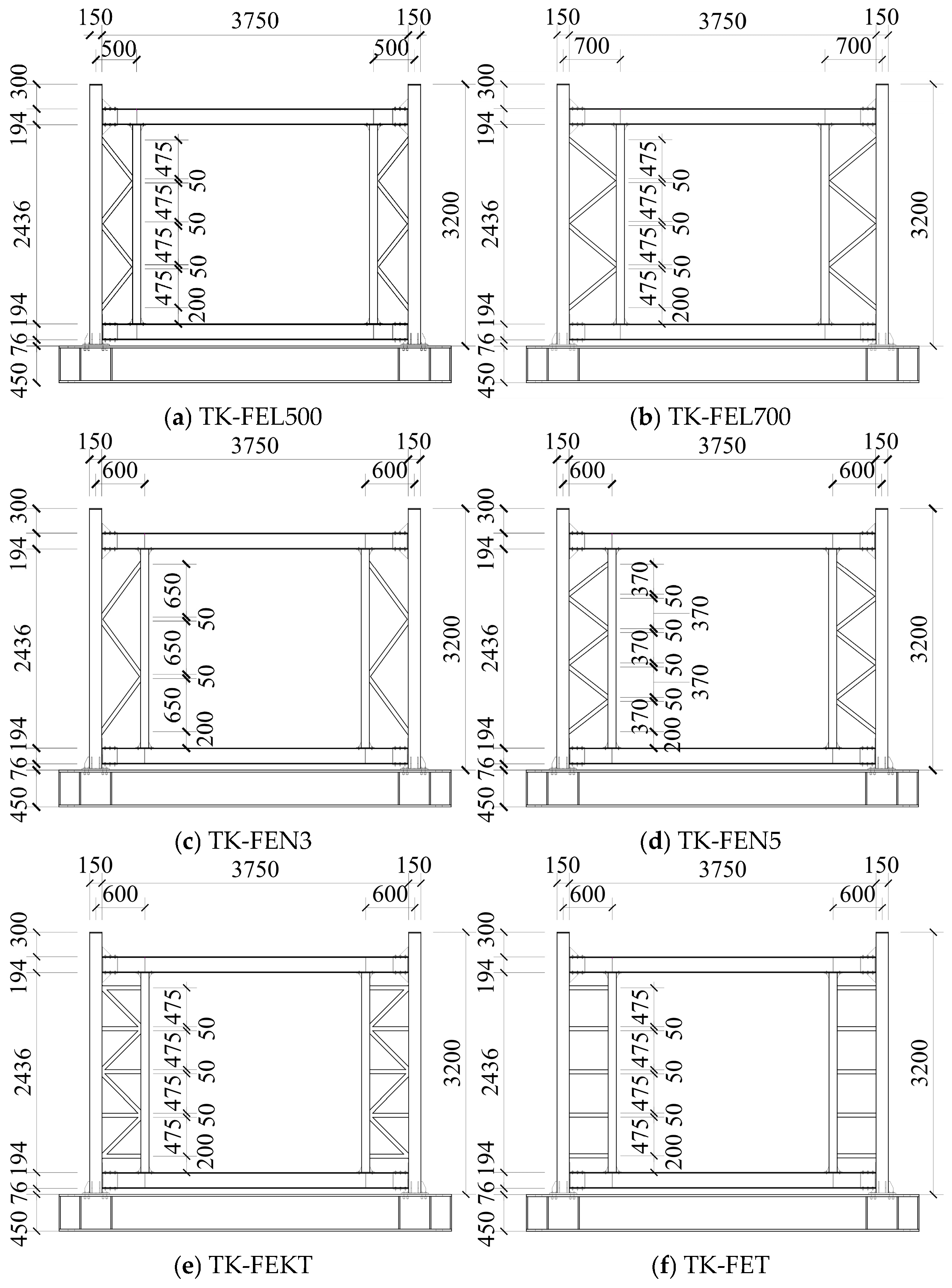

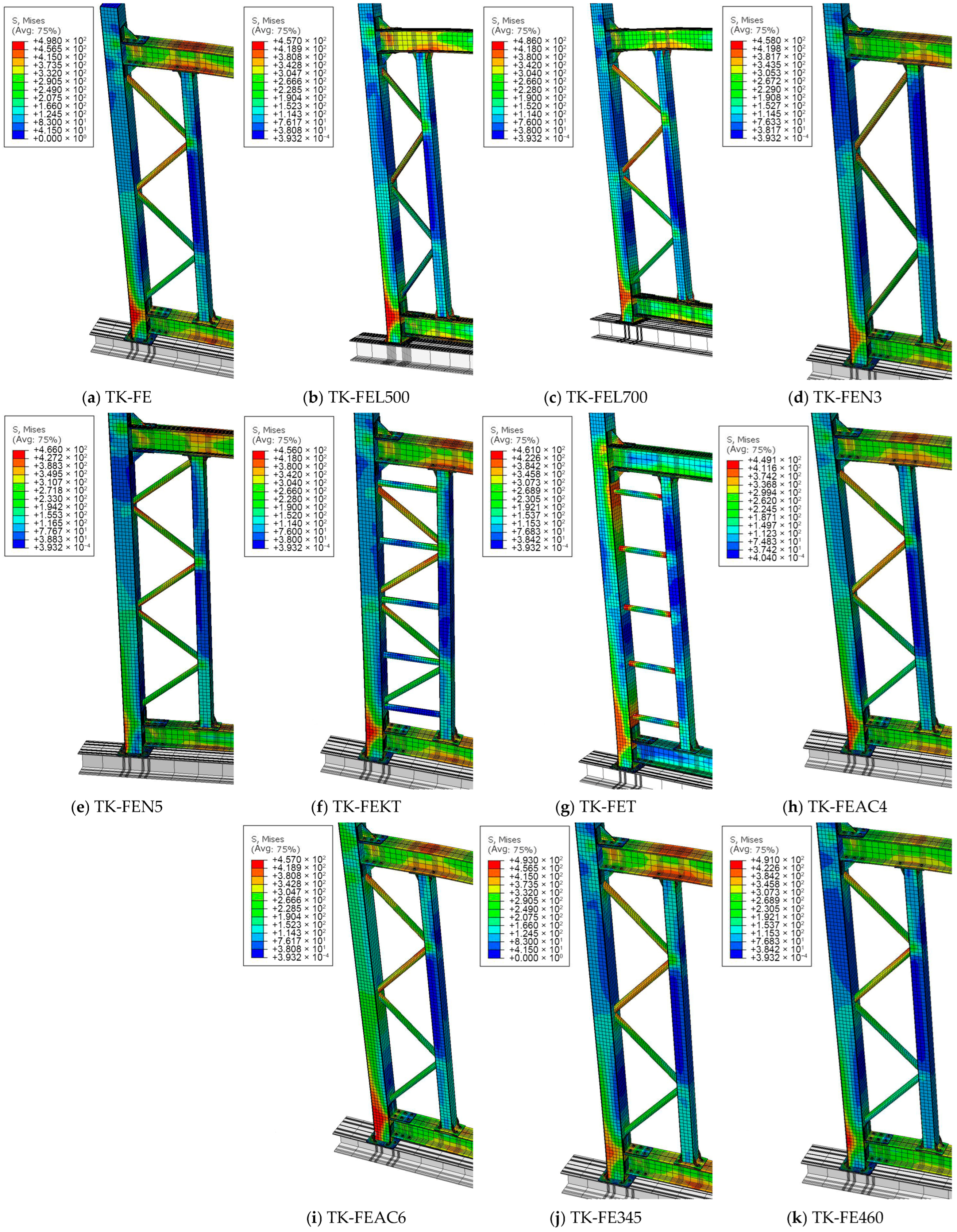

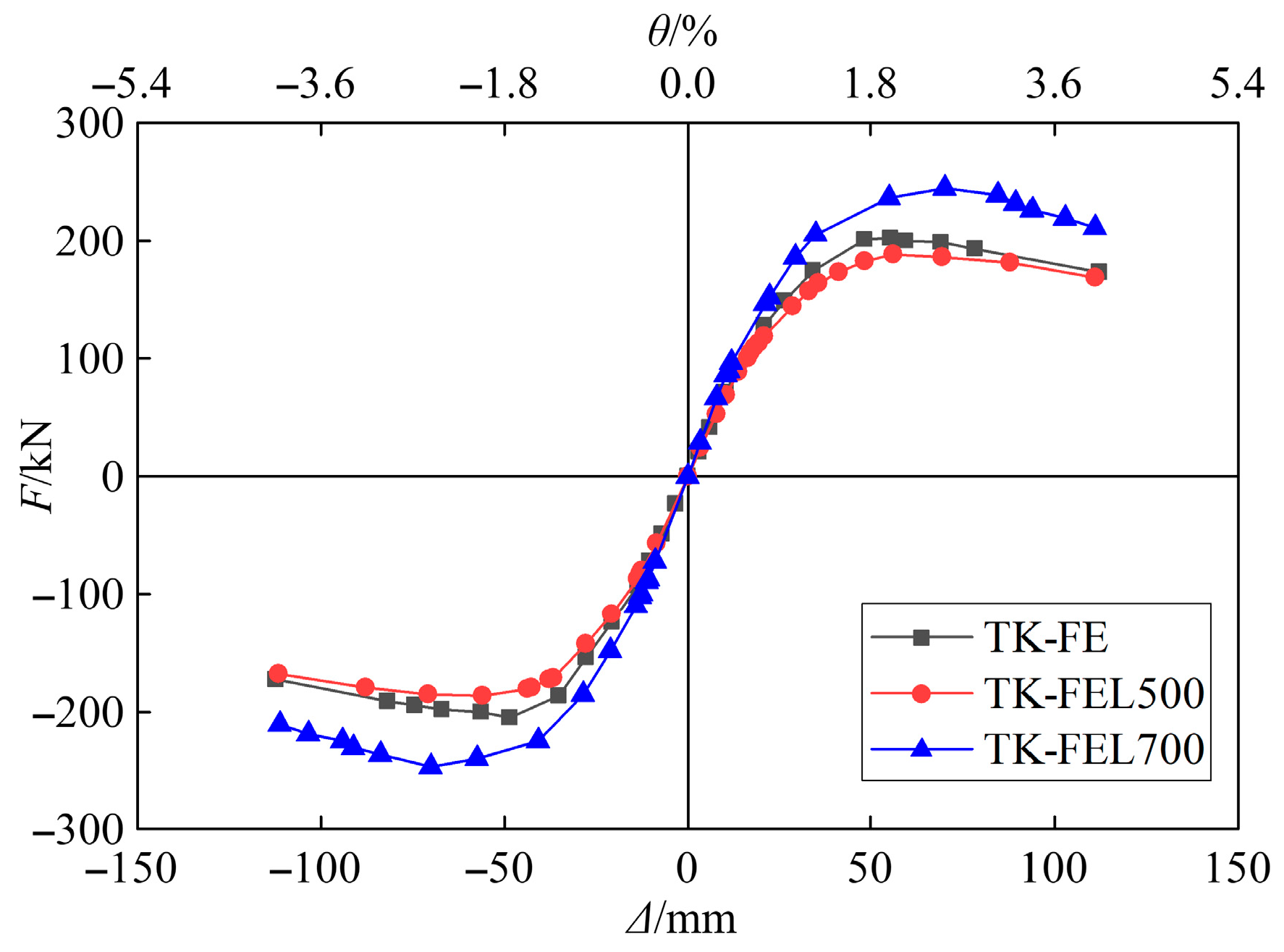

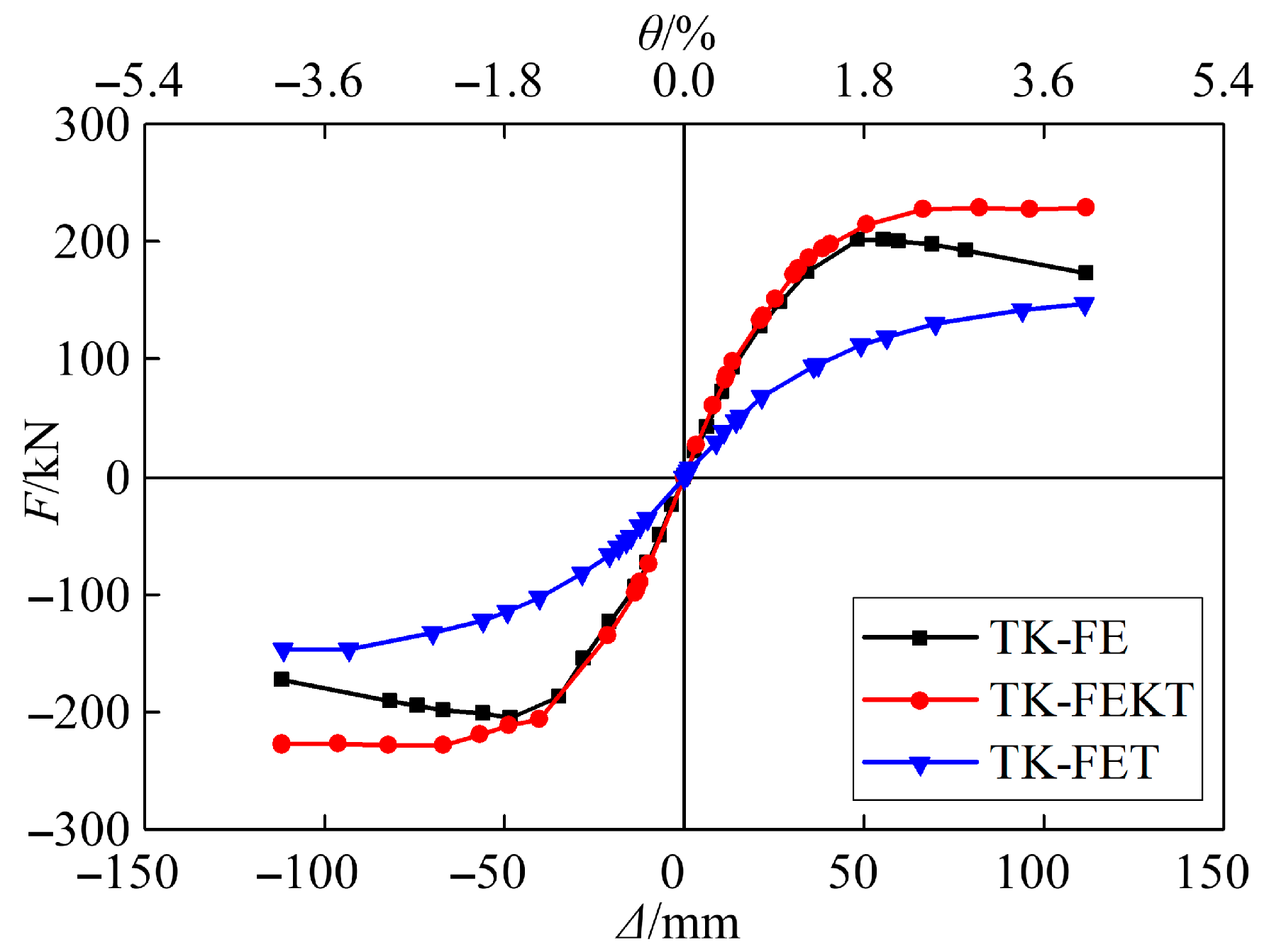

5.3.1. Effect of Corner Column and End Column Spacing

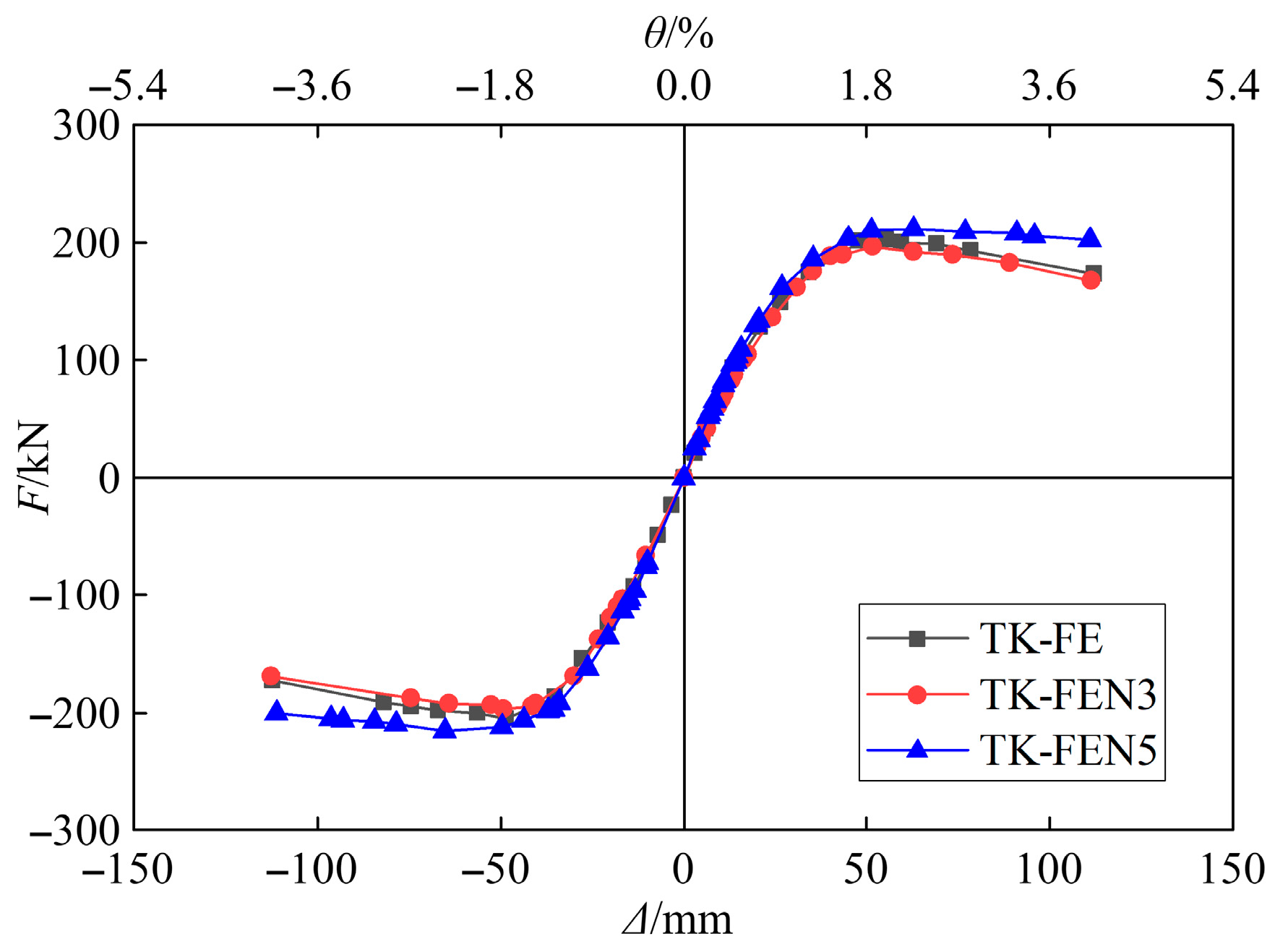

5.3.2. Effect of Number of Truss Diagonal Bars

5.3.3. Effect of Joint Type

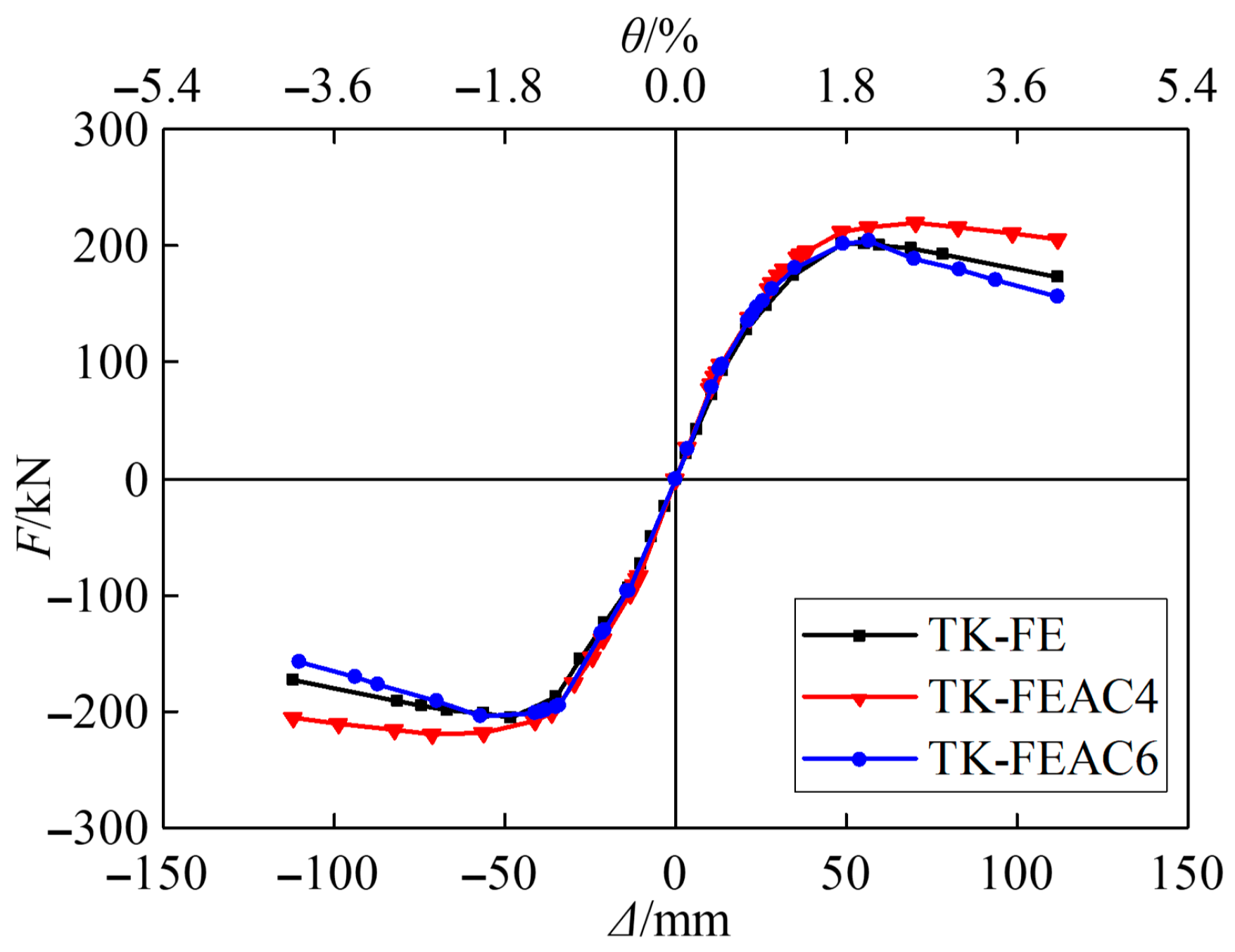

5.3.4. Effect of Column Axial Compression Ratio

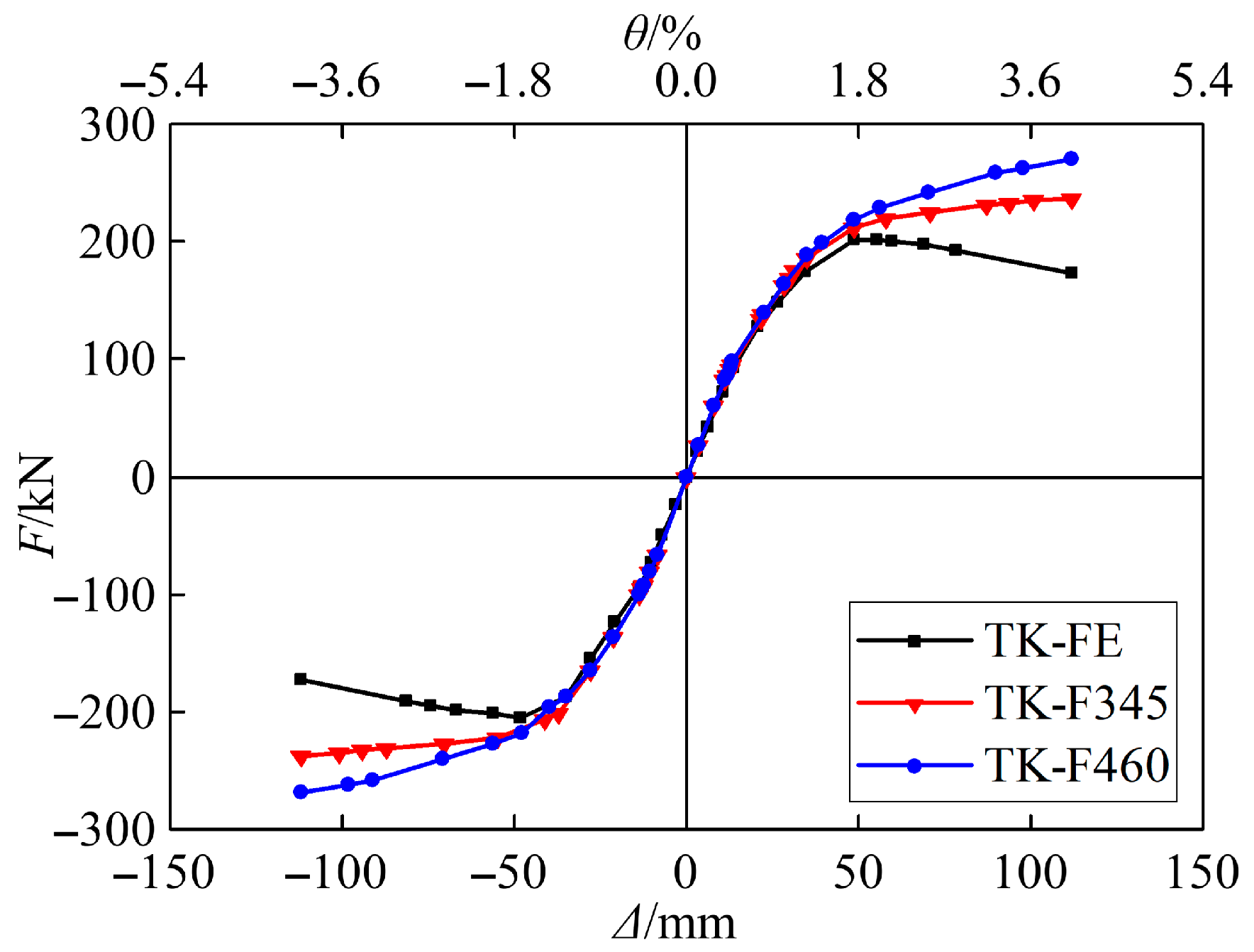

5.3.5. Effect of Steel Strength

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

- (1)

- Relative to an HK with comparable steel consumption, the TK achieved increases of 88.3% in yield load and 87.1% in peak load, along with markedly improved stiffness and cumulative energy dissipation, demonstrating a clear technical advantage.

- (2)

- Compared with a CFSST column frame, the TK required 41% more steel but achieved increases of 61% and 56% in yield load and peak load, respectively. Its initial and yield stiffnesses increased by 27% and 153%, respectively, and its cumulative energy dissipation and overall stiffness were significantly enhanced.

- (3)

- FE analysis indicated that: increasing the spacing between the corner and end columns improved the lateral stiffness and load capacity of the TK; the number of truss diagonal bars had minimal influence on the peak load; replacing K-type joints with KT-type or T-type joints increased the yield and peak loads by approximately 10% without affecting lateral stiffness; increasing the axial compression ratio produced modest gains in load capacity (within 10%), whereas excessively high ratios impaired structural performance; and steel strength exerted a substantial influence on load-carrying capacity and should be selected with due consideration of economic factors in design.

- (4)

- This study provides a structural system with high load-bearing capacity and regular indoor space for multi-story or low-rise frame residential buildings, and offers corresponding design basis and recommendations. However, it has limitations, such as the restricted number of specimens and the lack of investigation into multi-story frame models. Future research will address these aspects to achieve further refinement.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CFSST | Concrete-filled square steel tube |

| CFST | Concrete-filled steel tube |

| FE | Finite Element |

References

- Han, L.-H.; Li, W.; Bjorhovde, R. Developments and advanced applications of concrete-filled steel tubular (CFST) structures: Members. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2014, 100, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, B.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, J.; Zhang, R. Experimental and numerical research on hysteretic behavior of CFST frame with diaphragm-through connections. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 45, 103529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

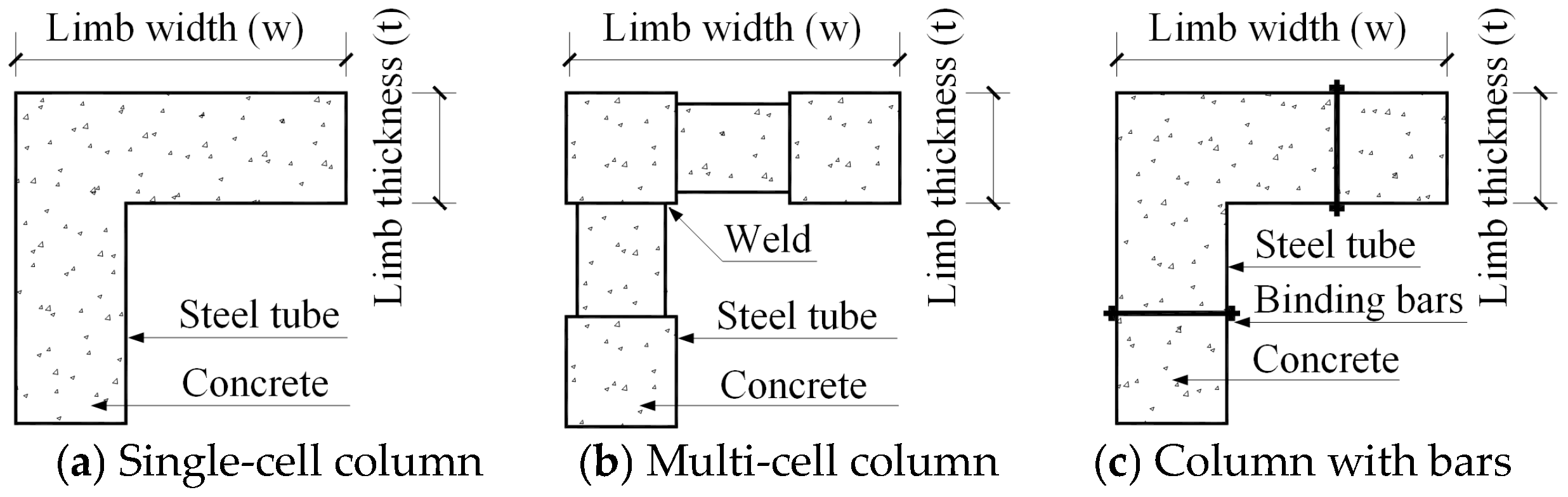

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Cai, J.; Lin, Y. Flexural behavior and design of stiffened and multi-cell cross-shaped CFST members. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2024, 220, 108870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zeng, S. Design of L-shaped and T-shaped concrete-filled steel tubular stub columns under axial compression. Eng. Struct. 2020, 207, 110262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Lin, Y.; Ma, S. Axial compressive behavior of stiffened and multi-cell cross-shaped CFST stub columns. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2024, 213, 108399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zeng, S. Flexural behaviour of stiffened and multi-cell L-shaped CFSTs considering different loading angles. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2021, 178, 106520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xu, C.; Liu, J.; Yang, Y. Research on special-shaped concrete-filled steel tubular columns under axial compression. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2018, 147, 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Q.; Chen, Z.; Kang, J.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, W. Experimental and finite element study on seismic performance of the LCFSTD columns. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2017, 137, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Q.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, W.; Du, Y.; Zhou, T.; Kang, J. Compressive behaviour and design of L-shaped columns fabricated using concrete-filled steel tubes. Eng. Struct. 2017, 152, 758–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Yu, Y. Seismic behavior of connections between H-beams and L-shaped column composed of concrete-filled steel tube mono-columns connected by double vertical plates. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2022, 198, 107513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Han, G.; Oluwadahunsi, S.; Sun, Y. Compressive capacity of cruciform-shaped concrete-filled steel tubes. Structures 2024, 69, 107592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, G.; Xiong, Q.; Gui, H. Seismic behavior of wide-limb special-shaped columns composed of concrete-filled steel tubes. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2023, 205, 107887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.-H.; Wang, X.; Guo, Y.-L.; Tian, Z.-H.; Li, J.-Y.; Bai, W.-H. Experimental and numerical study of L-shaped irregularly concrete-filled steel tube columns under axial compression and eccentric compression. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 84, 108572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Lei, H. Experimental and theoretical study on the eccentric compression performance of novel L-shaped composite columns composed of HGM-filled square steel tubes. Structures 2025, 75, 108728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alatshan, F.; Osman, S.A.; Hamid, R.; Mashiri, F. Stiffened concrete-filled steel tubes: A systematic review. Thin Walled Struct. 2020, 148, 106590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, R.; Luo, J.; Gong, M. Design of improved multi-cell L-shaped CFST columns under compression and bending. Structures 2024, 68, 107194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Z.-L.; Cai, J.; Chen, Q.-J.; Liu, X.-P.; Yang, C.; Mo, T.-W. Performance of T-shaped CFST stub columns with binding bars under axial compression. Thin Walled Struct. 2018, 129, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JGJ 149-2017; Technical Specification for Concrete Structures with Specially Shaped Columns. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2017.

- Zhou, T.; Xu, M.; Wang, X.; Chen, Z.; Qin, Y. Experimental study and parameter analysis of L-shaped composite column under axial loading. Int. J. Steel Struct. 2015, 15, 797–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Zhou, T.; Chen, Z.; Li, Y.; Bisby, L. Experimental study of slender LCFST columns connected by steel linking plates. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2016, 127, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

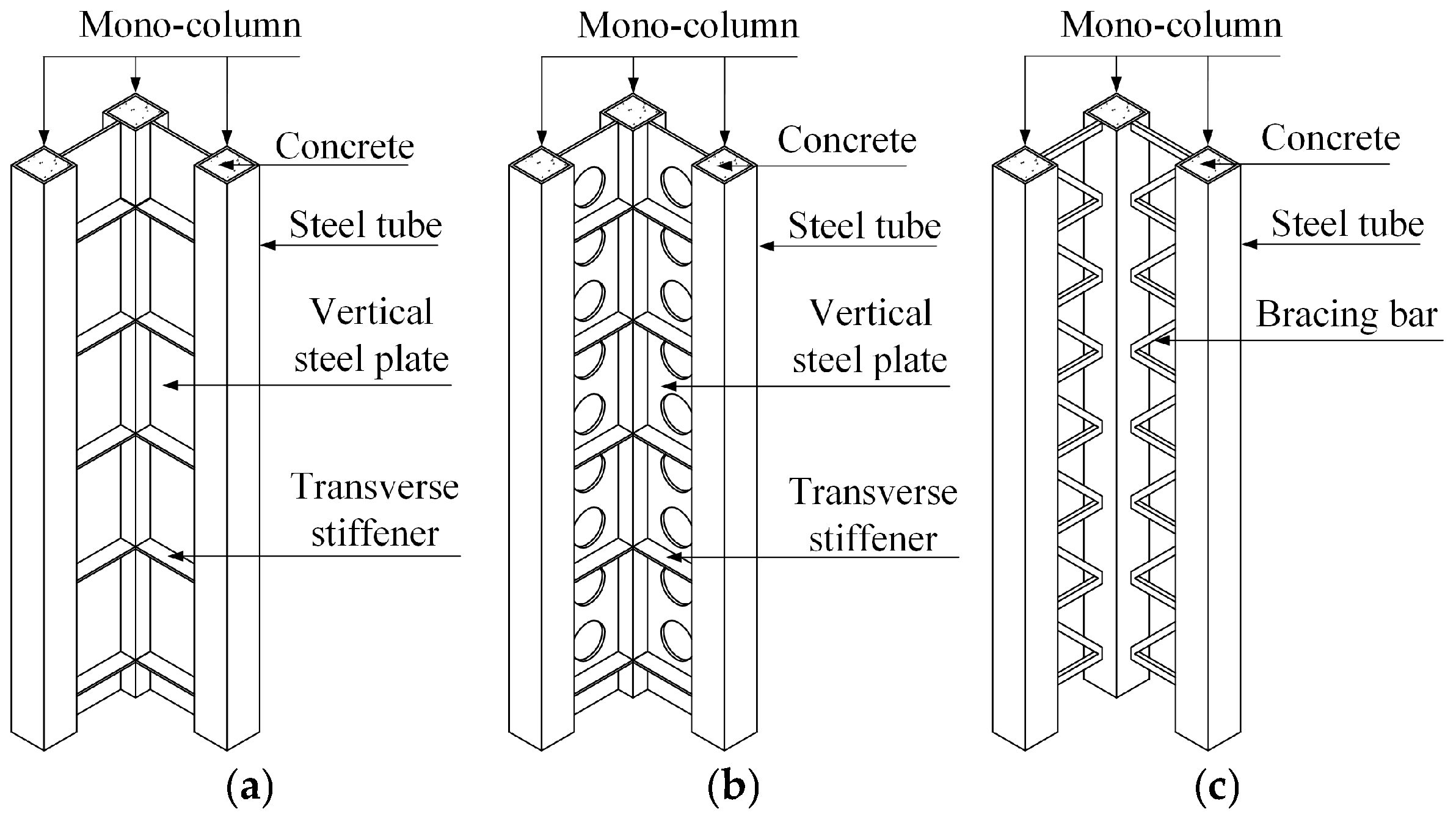

- Liang, Z.-S.; Han, L.-H. Trussed concrete-filled steel tubular hybrid structures subjected to axial compression: Performance and design calculation. Eng. Struct. 2024, 302, 117465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.-S.; Han, L.-H.; Hou, C. Trussed square concrete-filled steel tubular hybrid structures subjected to axial compression. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2023, 211, 108171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.-Q.; Li, G.-H.; Zhou, J.-Z.; Wang, Z.-Z. Behavior of three-chord concrete-filled steel tube built-up columns subjected to eccentric compression. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2021, 177, 106435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.-S.; Han, L.-H. Performance of trussed concrete-filled steel tubular (CFST) hybrid structures subjected to eccentric compression. Eng. Struct. 2025, 334, 120068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.-S.; Han, L.-H.; Wang, P. Performance and calculation of trussed concrete-filled steel tubular (CFST) hybrid structures subjected to bending. Eng. Struct. 2025, 325, 119478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Zhou, W.; Chen, L.; Liao, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Y. Flexural performance of steel fiber reinforced concrete filled stainless steel tubular trusses. Compos. Struct. 2023, 303, 116266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, Z.; Du, Y.; Amer, M.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Chen, J. Experimental and theoretical studies on lateral behavior of prefabricated composite concrete-filled steel tubes truss column. Structures 2024, 66, 106920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, M.; Chen, Z.; Du, Y.; Kang, S.; Mashrah, W.A.H. Experimental and numerical investigations on seismic behaviors of prefabricated composite CFT column V/Z-shaped truss. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2025, 227, 109364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Q.; Wu, C.; Cheng, Z.; Ding, Y.; Guo, H. The Seismic performance of new self-centering beam-column joints of conventional island main buildings in nuclear power plants. Materials 2022, 15, 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Q.; Qi, P.; Xue, Z.; Zhong, J.; Zhang, Y. Design and experimental analysis of seismic isolation bearings for nuclear power plant containment structures. Buildings 2023, 13, 2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Liu, S.; Zeng, S.; Zhang, B.; Xu, Z. Investigating seismic performance of a novel self-centering shear link in EBF utilizing experimental and numerical simulation. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2025, 224, 109129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, L.; Cai, L.; Li, Y.; Mohd Yusoff, Z. An experimental evaluation of steel beam-HSST/CFSST column connection with varying joint configurations. Buildings 2025, 15, 3774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 228.1-2021; Metallic Materials—Tensile Testing—Part 1: Method of Test at Room Temperature. China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2021.

- GB/T 50107-2010; Standard for Evaluation of Concrete Compressive Strength. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2010.

- JGJ 82-2011; Technical Specification for High Strength Bolt Connections of Steel Structures. China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2011.

- JGJ/T 101-2015; Specification for Seismic Test of Buildings. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2015.

- Ding, F.-X.; Chen, Y.-B.; Wang, L.; Pan, Z.-C.; Li, C.-Y.; Yuan, T.; Deng, C.; Luo, C.; Yan, Q.-W.; Liao, C.-B. Hysteretic behavior of CFST column-steel beam bolted joints with external reinforcing diaphragm. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2021, 183, 106729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50936-2014; Technical Code for Concrete Filled Steel Tubular Structures. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2014.

- GB 50011-2010; 2016 ed. Code for Seismic Design of Buildings. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Rong, B.; Feng, C.; Zhang, R.; Liu, S.; You, G. Studies on performance and failure mode of T-shaped diaphragm-through connection under monotonic and cyclic loading. J. Mech. Mater. Struct. 2018, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L. Concrete-Filled Steel Tubular Structures: Theory and Practice; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2022. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Cao, W.; Qiao, Q.; Zhang, J. Experimental and numerical study on the prefabricated double L-shaped beam-column joint with triangular stiffener. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 69, 106315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50010-2010; 2015 ed. Code for Design of Concrete Structures. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2015.

- Ruan, B.; Li, J.; Gan, Y.; Huang, J. Mesoscopic simulation of the mechanical behaviour of foam concrete subjected to large compressive deformation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 418, 135367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Amin, M.N.; Ahmed, B.; Khan, K.; Arifeen, S.U.; Althoey, F. Foam concrete for lightweight construction applications: A comprehensive review of the research development and material characteristics. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2024, 63, 20240022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, H.; Lv, B.; Du, C.; Wang, J. Investigation on the yield and failure criterion of foamed concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 84, 108604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Wei, Y.; Yun, Y. Analysis of steel-reinforced concrete-filled-steel tubular (SRCFST) columns under cyclic loading. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 28, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Qin, J.; Cao, W.; Zhao, L. Seismic behavior of circular CFST columns with different internal constructions. Eng. Struct. 2022, 260, 114262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Specimen | Frame Column Type | Column Section (mm) | Column Steel Weight (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HK | H-shaped steel column | HW 175 × 175 × 7.5 × 11 | 251.2 |

| FK | CFSST column | ☐ 150 × 150 × 6 | 173.5 |

| TK | CFSST column | Corner column 150 × 150 × 6 | 244.9 |

| End column 100 × 100 × 4 Diagonal bar Ø50 × 4 |

| Steel Type | Diameter/Thickness t (mm) | Yield Strength fy (MPa) | Ultimate Strength fu (MPa) | Elastic Modulus E (GPa) | Elongation δ (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFSST column square tube wall | 6 | 373.0 | 444.3 | 218.2 | 21.5 |

| Beam flange | 9 | 282.7 | 431.0 | 195.1 | 16.1 |

| Beam web | 6 | 296.0 | 453.0 | 202.2 | 30.7 |

| Angle connector plates | 8 | 318.0 | 468.0 | 202.9 | 19.1 |

| H-shaped steel column flange | 11 | 270.0 | 418.0 | 202.7 | 27.5 |

| H-shaped steel column web | 7.5 | 360.0 | 460.0 | 204.7 | 10.0 |

| CFSST corner column wall (in composite column) | 6 | 373 | 444.3 | 207.6 | 21.5 |

| CFSST end column wall (in composite column) | 4 | 414.0 | 552.0 | 204.8 | 27.3 |

| Hollow circular steel tube wall | 4 | 366.3 | 424.3 | 231.2 | 18.6 |

| Specimen | Loading Direction | Yield Point | Peak Point | Ultimate Point | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fy (kN) | θy (%) | Fp (kN) | θp (%) | Fu (kN) | θu (%) | ||

| HK | Positive | 89.4 | 1.78 | 103.5 | 3.34 | 99.1 | 3.52 |

| Negative | 101.3 | 1.79 | 112.1 | 3.47 | 102.2 | 3.48 | |

| FK | Positive | 109.1 | 1.52 | 132.5 | 2.81 | 122.6 | 3.98 |

| Negative | 113.4 | 1.46 | 125.9 | 2.34 | 113.7 | 3.50 | |

| TK | Positive | 169.8 | 1.36 | 196.2 | 1.71 | 164.2 | 2.49 |

| Negative | 188.9 | 1.49 | 207.5 | 1.62 | 184.9 | 3.07 | |

| Specimen | Initial Stiffness K0 | Yield Secant Stiffness Ky | Peak Secant Stiffness Kp | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (kN/mm) | (kN/mm) | (kN/mm) | ||||

| Measured Value | Relative Value | Measured Value | Relative Value | Measured Value | Relative Value | |

| HK | 5.9 | 1.00 | 1.27 | 1.00 | 1.36 | 1.00 |

| FK | 5.72 | 0.97 | 2.16 | 1.70 | 1.16 | 0.85 |

| TK | 7.28 | 1.23 | 5.47 | 4.31 | 3.49 | 2.57 |

| Specimen | Yield Point | Peak Point | Ultimate Point | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| θy (%) | Relative Value | θp (%) | Relative Value | θu (%) | Relative Value | |

| HK | 1.79 | 1.00 | 3.41 | 1.00 | 3.50 | 1.00 |

| FK | 1.49 | 0.83 | 2.58 | 0.76 | 3.74 | 1.07 |

| TK | 1.43 | 0.80 | 1.67 | 0.49 | 2.78 | 0.79 |

| Model ID | Difference from TK-FE |

|---|---|

| TK-FEL500 | Distance between the end column and angle column set to 500 mm |

| TK-FEL700 | Distance between the end column and angle column set to 700 mm |

| TK-FEN3 | Number of truss diagonal bars set to 3 |

| TK-FEN5 | Number of truss diagonal bars set to 5 |

| TK-FEKT | Truss joint type changed to KT type |

| TK-FET | Truss joint type changed to T type |

| TK-FEAC4 | Axial compression ratio set to 0.4 |

| TK-FEAC6 | Axial compression ratio set to 0.6 |

| TK-FE345 | Steel grade changed to Q345 |

| TK-FE460 | Steel grade changed to Q460 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Yuan, P.; Chen, L. Experimental and Numerical Study of the Seismic Behavior of Single-Plane Trussed CFSST Composite Column Frames. Buildings 2026, 16, 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010114

Zhang Z, Yuan P, Chen L. Experimental and Numerical Study of the Seismic Behavior of Single-Plane Trussed CFSST Composite Column Frames. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):114. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010114

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zongmin, Peng Yuan, and Lanhua Chen. 2026. "Experimental and Numerical Study of the Seismic Behavior of Single-Plane Trussed CFSST Composite Column Frames" Buildings 16, no. 1: 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010114

APA StyleZhang, Z., Yuan, P., & Chen, L. (2026). Experimental and Numerical Study of the Seismic Behavior of Single-Plane Trussed CFSST Composite Column Frames. Buildings, 16(1), 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010114