Parameter Sensitivity Analysis and Optimization Design of Shield Lateral Shifting Launching Technology Based on Orthogonal Analysis Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Project Overview

2.1. Project Location

2.2. Geological Conditions

2.3. Design Overview and Construction Sequence

2.4. Overview of Research Methods

- (1)

- Field monitoring and data analysis

- (2)

- Numerical model development and orthogonal experiment analysis

- (3)

- Regression analysis and parameter optimization

3. Field Monitoring

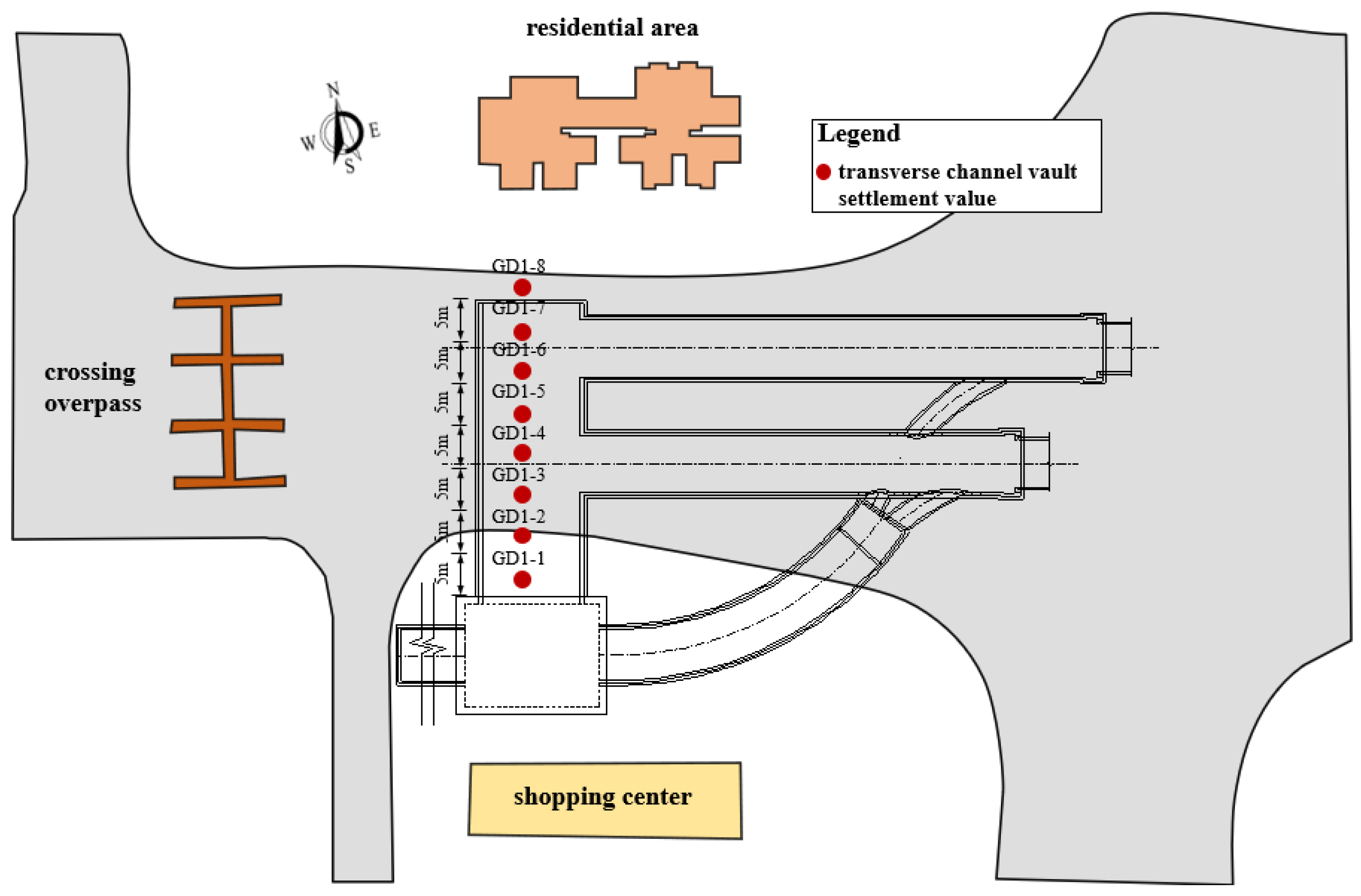

3.1. Monitoring Point Layout

3.2. Analysis of Monitoring Results

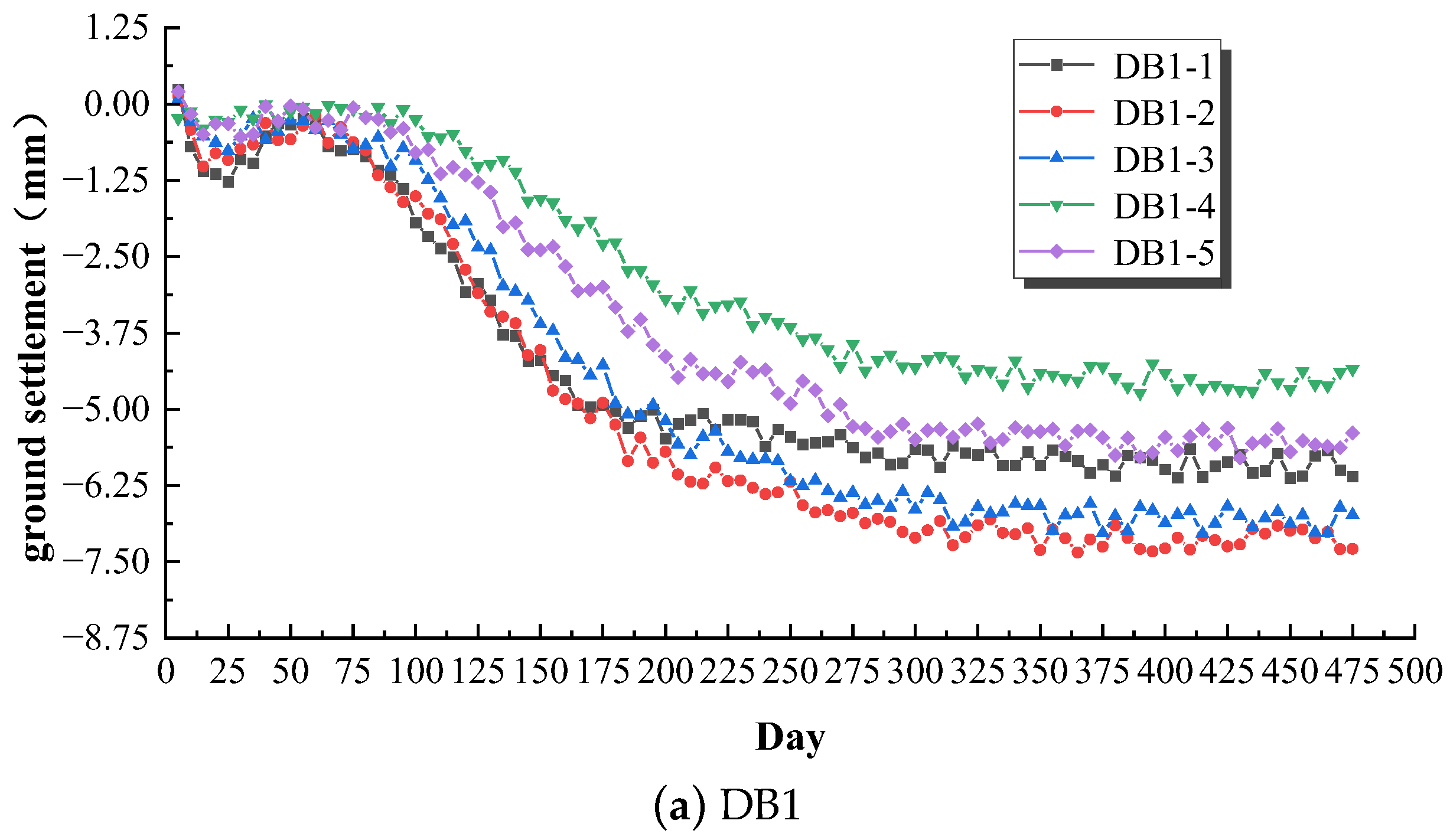

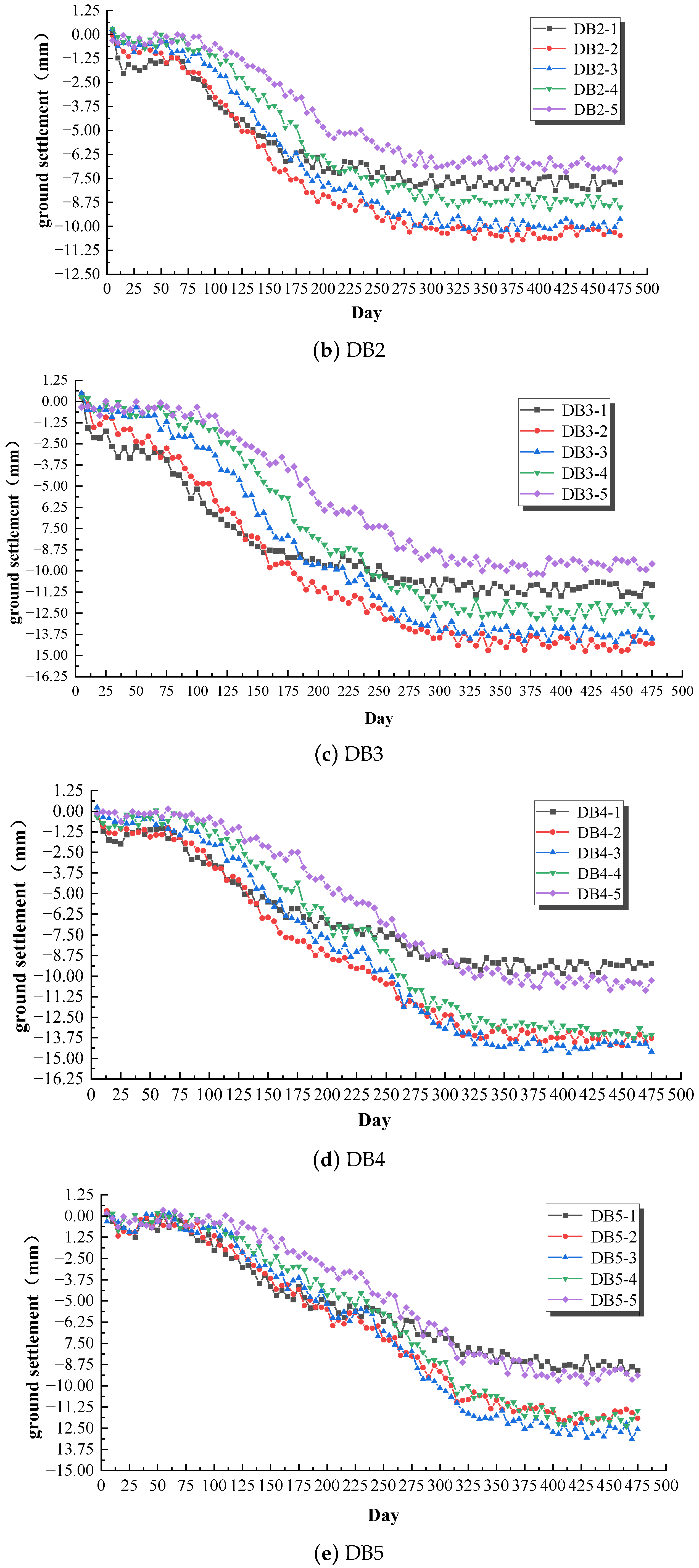

3.2.1. Analysis of Measured Ground Surface Settlement

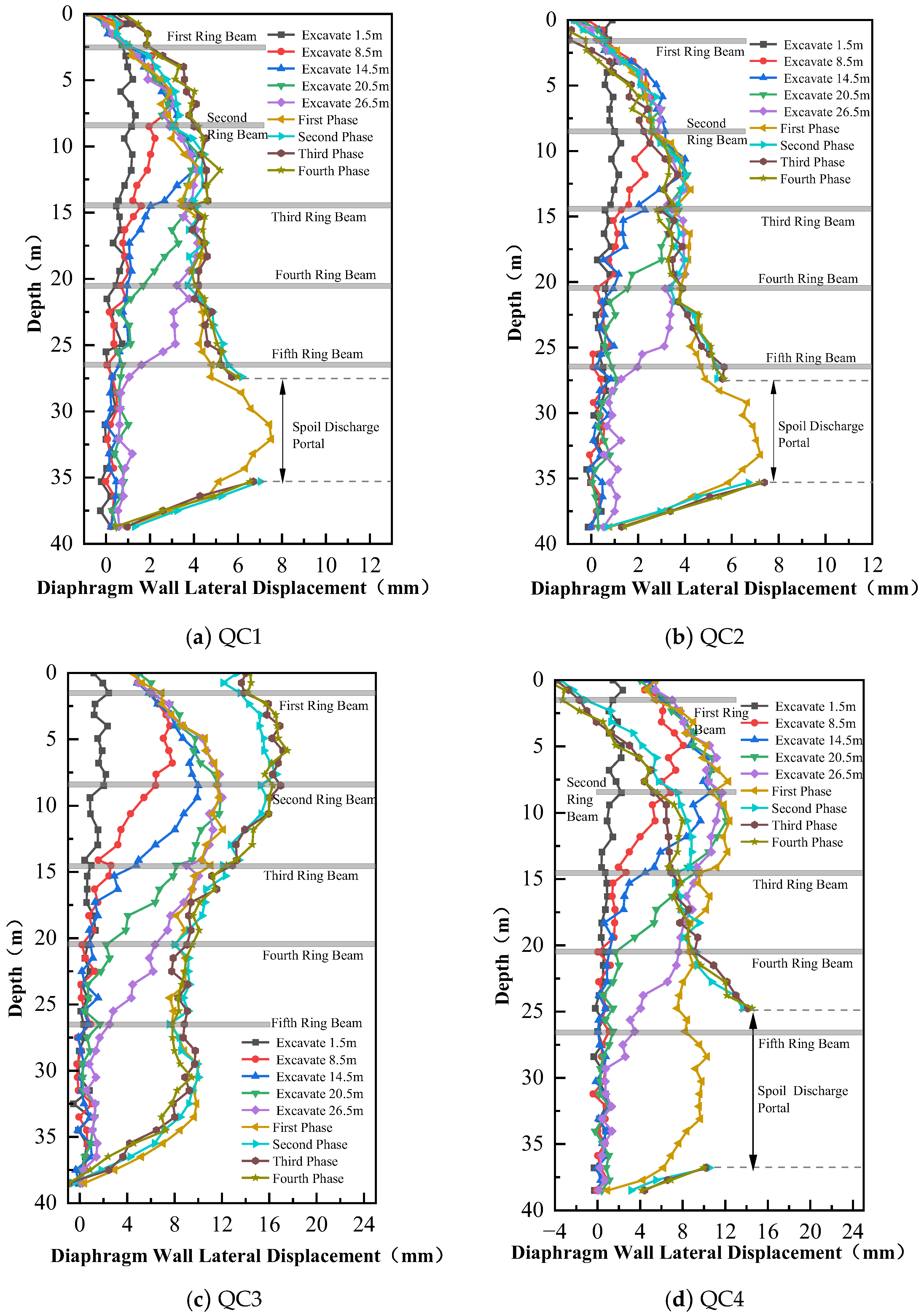

3.2.2. Diaphragm Wall Deformation Analysis

3.2.3. Tunnel Crown Settlement

4. Numerical Model Development and Verification

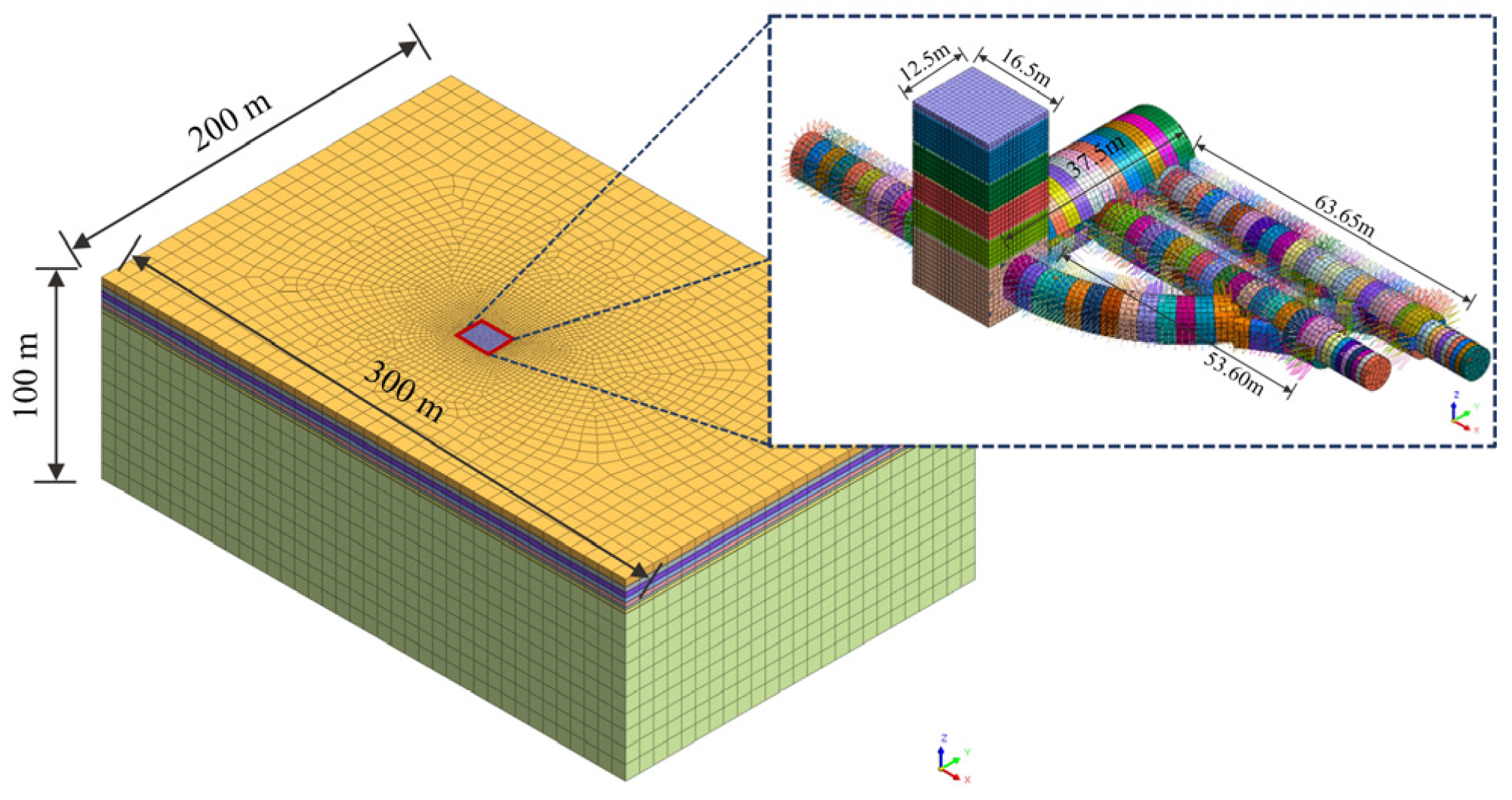

4.1. Numerical Simulation

4.2. Material Parameters and Constitutive Models

4.3. Verification of Numerical Simulation

4.3.1. Ground Settlement

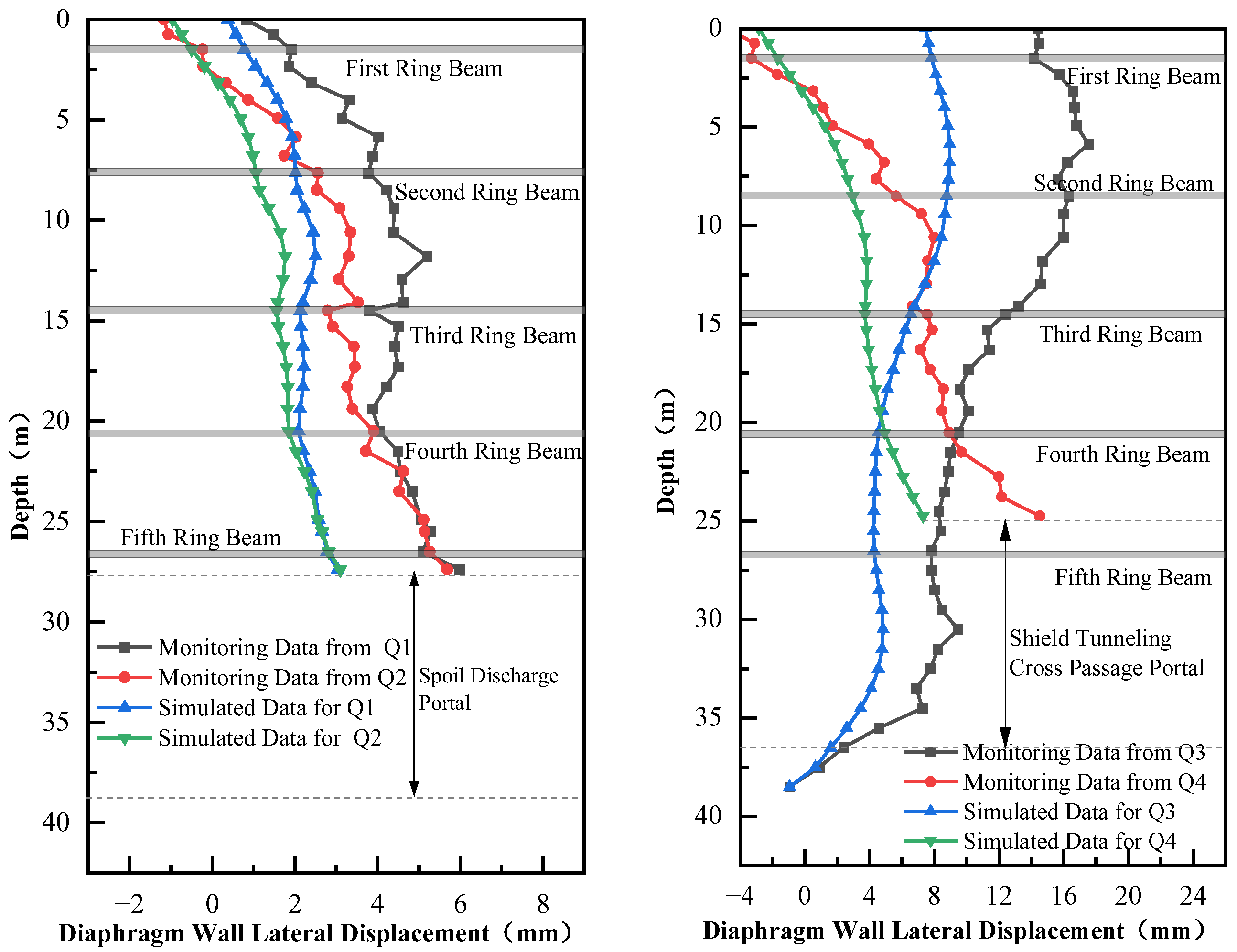

4.3.2. Diaphragm Wall Settlement

4.3.3. Tunnel Crown Deformation

5. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis Based on Orthogonal Design Method

5.1. Influencing Factors and Level Design

5.2. Test Calculation Results and Analysis

5.2.1. Summary of Orthogonal Test Results

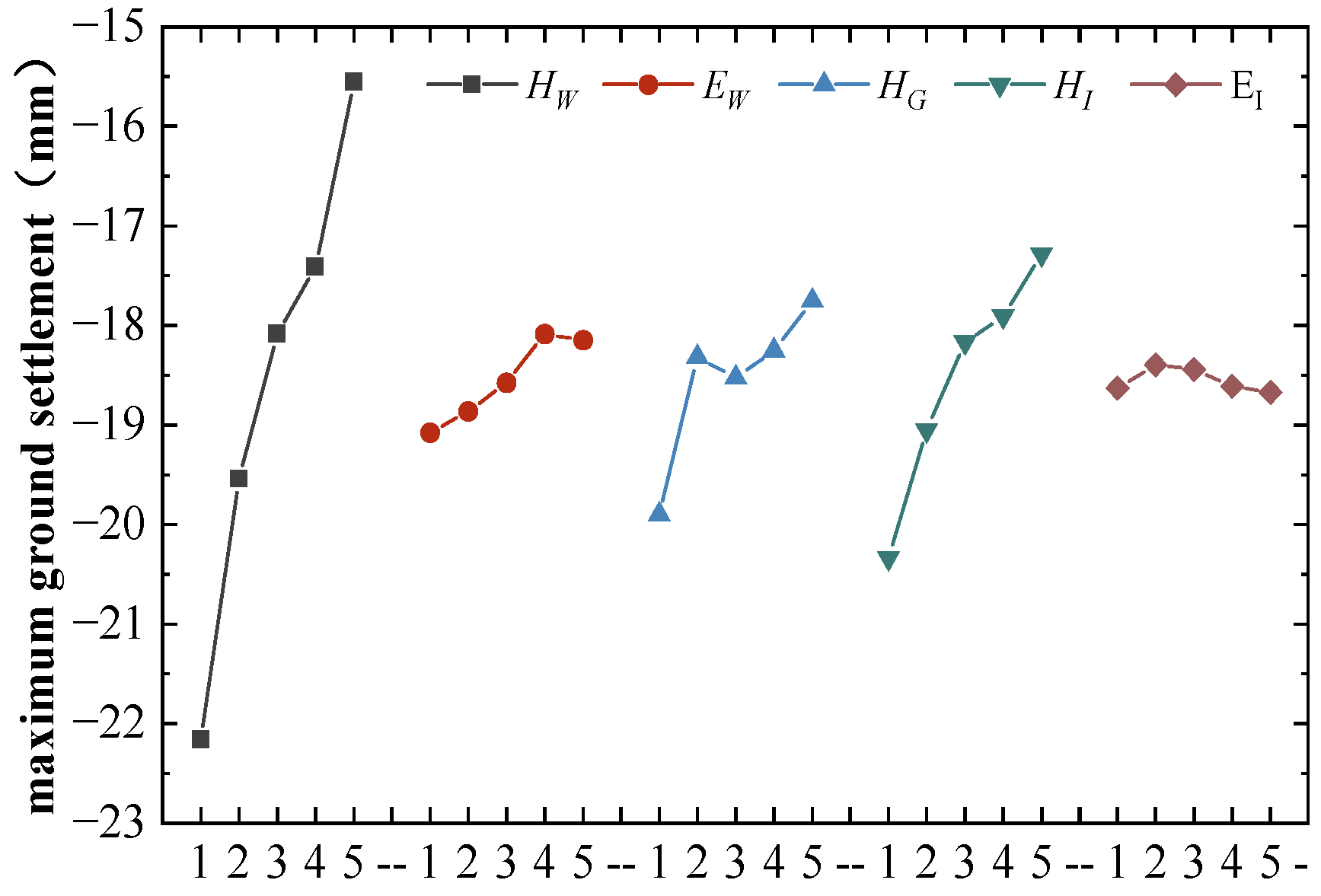

5.2.2. Analysis of Test Results and Parameter Sensitivity Evaluation

- (1)

- Range analysis

- (2)

- Analysis of Variance

- (3)

- Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

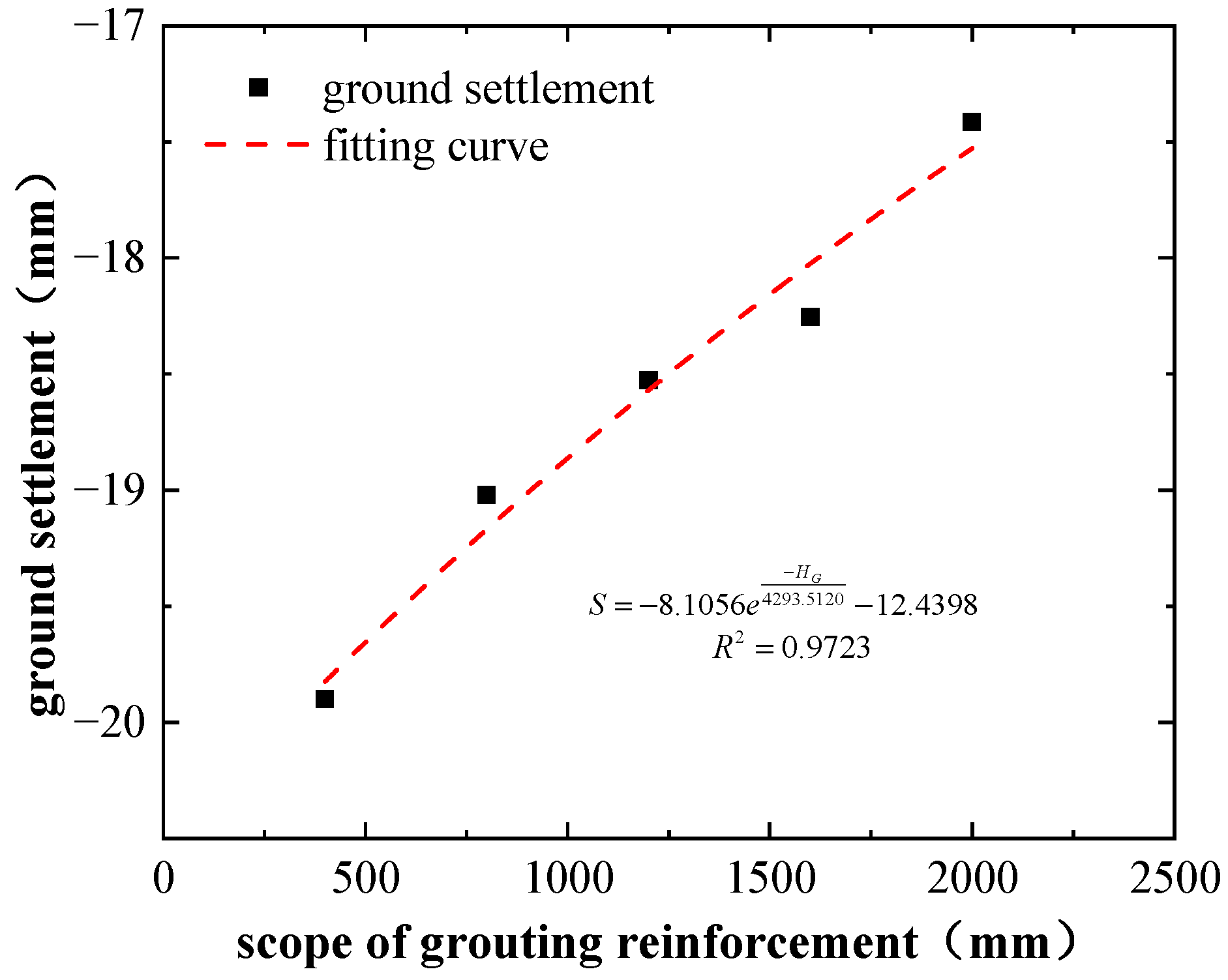

6. Parameter Optimization Design Based on Parameter Regression Analysis

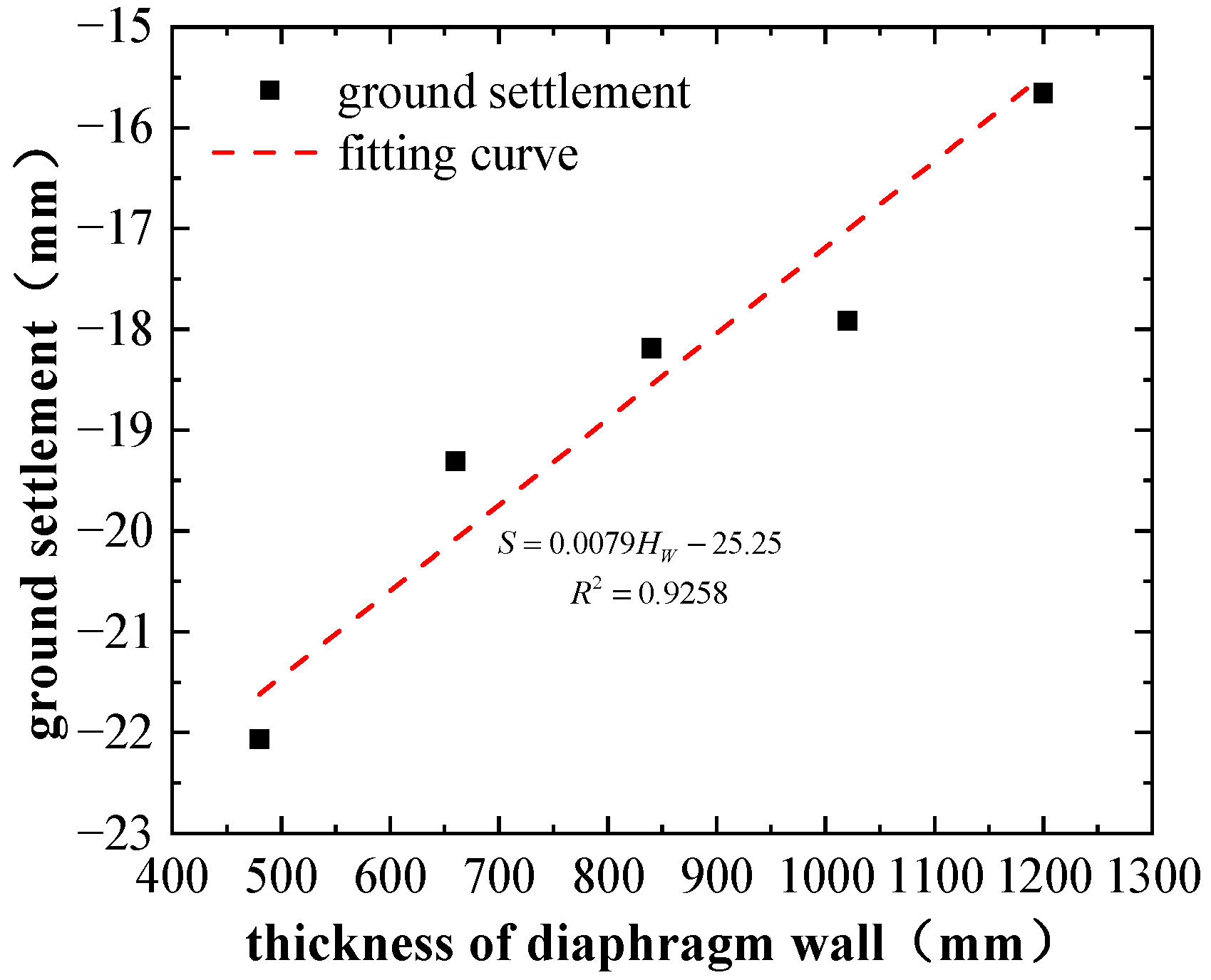

6.1. Regression Analysis of Ground Surface Settlement and Optimization Parameters

6.2. Design of the Optimization Scheme

6.3. Comparison of Deformation Control Schemes for the Optimization

6.4. Comprehensive Evaluation of the Optimized Scheme

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, D.; Mei, Y.; Ke, X.; Liu, Z.; Xu, W. Study on the Structural Behavior and Reinforcement Design of Openings in Subway Station Floor Slabs. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 110994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Yuan, D.; Li, X.; Zheng, H. Analysis of the Settlement of an Existing Tunnel Induced by Shield Tunneling Underneath. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 81, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, C. Vibration Table Test of Prefabricated L-Shaped Column Concrete Structure. Buildings 2025, 15, 2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Li, L.; Chen, K. Parametric Modeling for Detailed Typesetting and Deviation Correction in Shield Tunneling Construction. Autom. Constr. 2022, 134, 104052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Mei, Y.; Ke, X.; Liu, Z.; Xu, W. Experimental Study on Large-Scale Subway Station Model Considering Adjustable Water and Soil Pressure. Undergr. Space 2025, 25, 262–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, B.; Yuan, Y.; Yang, T.; Dong, G.; Shi, C. Study on the Effect of EICP Combined with Nano-SiO2 and Soil Stabilizer on Improving Loess Surface Strength. Buildings 2025, 15, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.-M.; Liu, J.-H.; Wang, R.-L.; Li, Z.-M. Shield Tunneling and Environment Protection in Shanghai Soft Ground. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2009, 24, 454–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Z.; Chen, T.; Song, Q.; Ren, D.; Wang, J. Analysis of the Influence of Stratum Parameters on Ground Settlement during Shield Construction in Composite Strata. Mod. Tunn. Technol. 2024, 61, 404–414. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, B.-X.; Gao, Z. Investigating Surface Deformation Caused by Excavation of Curved Shield in Upper Soft and Lower Hard Soil. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 844969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liang, Y.; Feng, T. Investigation of the Cause of Shield-Driven Tunnel Instability in Soil with a Soft Upper Layer and Hard Lower Layer. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2020, 118, 104832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Huang, Z. Influencing Factors and Sensitivity Analysis of Shield Construction in Water-Bearing Sand–Pebble Stratum. J. Eng. Geol. 2024, 32, 1787–1797. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, F.; Qin, N.; Gao, X.; Quan, X.; Qin, X.; Dai, B. Shield Equipment Optimization and Construction Control Technology in Water-Rich and Sandy Cobble Stratum: A Case Study of the First Yellow River Metro Tunnel Undercrossing. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2019, 2019, 8358013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Yang, Y.; Tao, M.; Wang, D.; Jie, Y. Earth Pressure Balance Shield Tunneling in Sandy Gravel Deposits: A Case Study of Application of Soil Conditioning. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2020, 79, 5013–5030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Huang, C.; Ma, S.; Hong, K.; Xu, Q.; Yan, M. Measurement and Analysis of Surface Settlement Caused by Construction of Quasi-Rectangular Shield Tunnel in Rich Water-Sand Stratum. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Niu, H.; Liu, X.; Dong, Y. Physical Modeling of Wetting-Induced Collapse of Shield Tunneling in Loess Strata. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2019, 90, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, R.; Yang, T.; Zhang, Y. Experimental Study on Shield Tunneling Control in Full Section Water-Rich Sand Layer of Collapsible Loess. Geofluids 2022, 2022, 9125283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, Z.; Wang, L.; Zeng, Z.; Gu, D. Numerical Simulation and Analysis of the Pile Underpinning Technology Used in Shield Tunnel Crossings on Bridge Pile Foundations. Undergr. Space 2021, 6, 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Wei, J.; Liang, H.; Chen, Z.; Ding, W.; Li, B. Structural Behavior Analysis for Existing Pile Foundations Considering the Effects of Shield Tunnel Construction. Buildings 2025, 15, 3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X. Settlement Analysis and Prediction of Existing Pipelines Induced by Shield Underpass Construction. Mech. Q. 2024, 45, 239–247. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Jiang, A.; Fang, Q.; Wan, Y.; Li, J.; Guo, X. Spatiotemporal Deformation of Existing Pipeline Due to New Shield Tunnelling Parallel beneath Considering Construction Process. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Hong, K.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, M.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, H. Deformation Analysis of Large-Section Quasi-Rectangular Shield Construction on Existing Underground Pipelines and Power Tunnel. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, R.; Xia, T.; Hong, Y.; Yu, F. Effects of Above-Crossing Tunnelling on the Existing Shield Tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2016, 58, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Ping, Y.; Ting, Z.; He, D. Vertical Freezing Reinforcement and Monitoring in Site for Tunnel Shield-Launching End in Soft Soil Stratum. J. Nanjing For. Univ. 2015, 39, 125. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, B.; Cai, H.; Cheng, H. Vertical Ground-Freezing Reinforcement Technology for Metro Shield Tunnel Portals. Railw. Stand. Des. 2011, 68, 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, X.L.; Wu, L.; Nguyen, K.T.; Bui, Q.A.; Nguen, H.H.; Luu, H.P. Research on Launching Technology of Shield Tunnel in Ho Chi Minh Metro Line 1. Arch. Civ. Eng. 2021, 67, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Liu, W.; Zhai, S.; Chen, P. Influence of Water Inrush from Excavation Surface on the Stress and Deformation of Tunnel-Forming Structure at the Launching-Arrival Stage of Subway Shield. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2019, 2019, 6989730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Lu, Y.; Zhen, J.; Lan, X.; Xu, C.; Yu, W. Analysis of Face Stability at the Launch Stage of Shield or TBM Tunnelling Using a Concrete Box in Complex Urban Environments. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 135, 105067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.-S.; Peng, F.-L.; Qiao, Y.-K.; Hu, Y.-Y. A New Cryogenic Sealing Process for the Launch and Reception of a Tunnel Shield. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2019, 85, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhang, J.-Y.; Wu, C.; Kao, C. Case Studies on Ground Freezing in Taipei. 2009. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:130418267 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Guo, B.; He, H.; Meng, X.; Ren, H.; Zuo, L.; Li, J.; Dai, B.; Zhao, C. Numerical Investigation of End Reinforcement Technology for Super-Large-Diameter Shield Tunnels and Online Prediction Using Machine Learning. Int. J. Multiscale Comput. Eng. 2025, 23, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Huang, X.; Dai, Z.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; Yu, W. Analysis of the Collapse Mechanism and Stabilization Optimization of the Composite Stratum at the Boundary Between Prereinforced and Unreinforced Areas Near a Shield Launching Area. Int. J. Geomech. 2023, 23, 5023002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Jiang, B.; Wei, H.; Wang, X. Applications of New Reinforcement Methods in City Tunnels for Shield Launching and Arriving. In Civil, Architecture and Environmental Engineering; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Jiang, B.S.; Zeng, H.; Chen, Y.N.; Zhu, Y.Y. Temperature Field Numerical Analysis of Different Freeze Pipe Spacing of Vertical Frozen Soil Wall Reinforcement at Shield Shaft. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 580–583, 738–741. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Liu, Y.; Wei, H.; Yao, K.; Wang, W. Finite-Element Analysis of Heat Transfer of Horizontal Ground-Freezing Method in Shield-Driven Tunneling. Int. J. Geomech. 2017, 17, 04017080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Liu, W.; Pan, Y.; Zeng, H. Site Measurement and Study of Vertical Freezing Wall Temperatures of a Large-Diameter Shield Tunnel. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2019, 2019, 8231458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.-F. Numerical Analysis on Reinforcement Range of a Closed Steel Sleeve against Collapse. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 2021, 5593657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.J.; Wei, G.; Hong, J. Study of Analytical Solution on Starting Shaft Disaster in Shield Launching. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 261–263, 1475–1479. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, G.; Zheng, H.; Li, P. Displacement Characteristics for a “π” Shaped Double Cross-Duct Excavated by Cross Diaphragm (CRD) Method. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 77, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Wu, H.; Zheng, A. Shield Machine Lateral Transfer Technology in Metro Cross-Passages Based on BIM. Railw. Constr. 2021, 61, 74–77. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z. Shield Lateral Launching Technology and Mechanical Characteristics of Special-Shaped Steel Sleeve in Narrow Urban Space. Master’s Thesis, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, H. Shield Lateral Transfer and Launching (Receiving) Construction Technology. Railw. Constr. Technol. 2020, 32, 122–126. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H. Study on Shield Lateral Launching Technology under Site Constraints. Constr. Saf. 2024, 39, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, X. Factor Analysis and Numerical Simulation of Rock Breaking Efficiency of TBM Deep Rock Mass Based on Orthogonal Design. J. Cent. South Univ. 2022, 29, 1345–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Su, J.; Liu, Z.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, S. Sensitivity Analysis and Experimental Verification of Bolt Support Parameters Based on Orthogonal Experiment. Shock Vib. 2020, 2020, 8844282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, B.; Xu, Z.; Wang, J.; Luo, Z.; Hu, L. Numerical Investigation on Influential Factors for Quality of Smooth Blasting in Rock Tunnels. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 2020, 9854313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Wang, S.; Geng, P.; Li, P.; Shen, H.; Deng, L. Parametric Study of Tunnel Fault Resistance Using Numerical Modeling and Orthogonal Experiment for Segmental Lining Design. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2025, 198, 109599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Sun, W.; Meng, G. Sensitivity Analysis of Influencing Factors of Karst Tunnel Construction Based on Orthogonal Tests and a Random Forest Algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; Li, W.; Abbassi, R.; Chen, K. Structural Integrity Assessment of Shield Tunnel Crossing of a Railway Bridge Using Orthogonal Experimental Design. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2020, 114, 104594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, H.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wan, L.; Liu, Y. Back Analysis and Optimization of SMW Pile Parameters Based on Orthogonal Numerical Tests. Mod. Tunn. Technol. 2022, 59, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50911-2013; Code for Monitoring of Urban Rail Transit Engineering. MOHURD: Beijing, China, 2014.

- Hu, J.; Sun, L.; Cui, H.; Gao, P. Numerical Analysis of Deep Excavation Deformation Based on Modified Mohr–Coulomb Model. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2021, 21, 7717–7723. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, B.; Liu, Q.; Yang, D.; Wang, Y.; Su, W. Study on Stability of Grouting Reinforcement for Highway Soil Slopes. J. Highw. Transp. Res. Dev. 2021, 38, 45–51, 87. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Qiu, D.; Su, M.; Li, L.; Li, Z.; Tao, Y. Analysis of Factors Influencing Tunnel Deformation in Loess Deposits by Data Mining: A Deformation Prediction Model. Eng. Geol. 2018, 232, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Wang, G.; Yu, F.; Du, J. Analytical Algorithm for Longitudinal Deformation Profile of a Deep Tunnel. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2021, 13, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, S. Sensitivity Analysis and Optimization of Diaphragm Wall Support Parameters for Deep Excavations in Soft Soil. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 2015, 11, 666–673. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, W.; Hou, F. Contribution Analysis of Advanced Reinforcement and Initial Support to Ground Settlement Control in Shallow-Buried Tunnels. J. Railw. Sci. Eng. 2021, 18, 720–727. [Google Scholar]

- Kavvadas, M.J. Monitoring Ground Deformation in Tunnelling: Current Practice in Transportation Tunnels. Eng. Geol. 2005, 79, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Wang, B.; Zi, X.; Guo, X.; Wang, Z. Effect of Prestressed Anchorage System on Mechanical Behavior of Squeezed Soft Rock in Large-Deformation Tunnel. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 131, 104782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JGJ 120-99; Technical Code for Building Foundation Pit Support. China Academy of Building Research: Beijing, China, 1999.

- GB 50086-2015; Technical Specification for Rock and Soil Anchors and Shotcrete Support Engineering. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2015.

| Project | Frequency | Instruments | Cumulative Settlement Value (mm) | Change Rate (mm/d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ground settlement | 1 times/day | level instrument | 30 | 3 |

| diaphragm wall lateral displacement | 1 time/2 days | convergence gauge | 30 | 2 |

| Tunnel crown settlement | 2 times/day | total station | 30 | 3 |

| Soil Layer Name | Poisson Ratio/ν | Severity/γ (kN·m−3) | Internal Friction Angle/φ(°) | Cohesion/c (kPa) | (MPa) | (MPa) | (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miscellaneous Fill | 0.30 | 17.8 | 8 | 10 | 14.5 | 14.5 | 43.5 |

| Silty Clay | 0.35 | 18.9 | 11 | 20 | 20.1 | 20.1 | 60.3 |

| Medium to Coarse Sand | 0.25 | 19.1 | 30 | 0 | 25.2 | 25.2 | 75.6 |

| Highly Weathered Argillaceous Siltstone | 0.25 | 20.3 | 30 | 40 | 134.2 | 134.2 | 402.6 |

| Moderately Weathered Argillaceous Siltstone | 0.22 | 23.7 | 35 | 60 | 242.5 | 242.5 | 727.5 |

| Slightly Weathered Argillaceous Siltstone | 0.20 | 26.1 | 40 | 80 | 305.8 | 305.8 | 917.4 |

| Project | Size (mm) | Elastic Modulus/ES (MPa) | Poisson Ratio/ν | Severity/γ (kN·m−3) | Constitutive Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| diaphragm wall | 1200 | 31,500 | 0.20 | 24.0 | slab |

| ring frame beam | 3000 × 1500 2500 × 1500 | 31,500 | 0.20 | 24.0 | beam |

| grouting reinforcement soil | 2000 | 60 | 0.28 | 22.0 | modified Mohr–Coulomb model |

| anchors | φ22 | 300 | 0.30 | 7.85 | embedded truss structure |

| initial support | 300 | 28,000 | 0.20 | 24.0 | slab |

| secondary lining | 600 | 31,500 | 0.20 | 24.0 | solid |

| shield segment | 300 | 50,000 | 0.20 | 24.0 | solid |

| Orthogonal Levels | Diaphragm Wall Thickness/HW (mm) | Elastic Modulus of Diaphragm Wall/EW (MPa) | The Scope of Grouting Reinforcement of the Transverse Channel/HG (mm) | The Thickness of the Initial Branch of the Transverse Channel/H1 (mm) | Thickness of Initial Branch of Advanced Starting Channel/H2 (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 480 | 22,050 | 400 | 120 | 110 |

| 2 | 660 | 26,775 | 800 | 165 | 150 |

| 3 | 840 | 31,500 | 1200 | 210 | 200 |

| 4 | 1020 | 36,225 | 1600 | 255 | 250 |

| 5 | 1200 | 40,950 | 2000 | 300 | 290 |

| Test | Diaphragm Wall Thickness/HW (mm) | Elastic Modulus of Diaphragm Wall/EW (MPa) | The Scope of Grouting Reinforcement of the Transverse Channel/HG (mm) | The Thickness of the Initial Branch of the Transverse Channel/H1 (mm) | Thickness of Initial Branch of Advanced Starting Channel/H2 (mm) | Maximum Ground Settlement (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| test 1 | 480 | 22,050 | 400 | 120 | 110 | −26.14 |

| test 2 | 480 | 26,775 | 800 | 165 | 150 | −22.07 |

| test 3 | 480 | 31,500 | 1200 | 210 | 200 | −21.80 |

| test 4 | 480 | 36,225 | 1600 | 255 | 250 | −21.13 |

| test 5 | 480 | 40,950 | 2000 | 300 | 290 | −20.66 |

| test 6 | 660 | 22,050 | 800 | 210 | 110 | −19.36 |

| test 7 | 660 | 26,775 | 1200 | 255 | 150 | −19.55 |

| test 8 | 660 | 31,500 | 1600 | 300 | 200 | −17.56 |

| test 9 | 660 | 36,225 | 2000 | 120 | 250 | −19.35 |

| test 10 | 660 | 40,950 | 400 | 165 | 290 | −21.19 |

| test 11 | 840 | 22,050 | 1200 | 300 | 110 | −17.48 |

| test 12 | 840 | 26,775 | 1600 | 120 | 150 | −19.62 |

| test 13 | 840 | 31,500 | 2000 | 165 | 200 | −18.11 |

| test 14 | 840 | 36,225 | 400 | 210 | 250 | −18.19 |

| test 15 | 840 | 40,950 | 800 | 255 | 290 | −17.02 |

| test 16 | 1020 | 22,050 | 1600 | 165 | 110 | −18.39 |

| test 17 | 1020 | 26,775 | 2000 | 210 | 150 | −17.94 |

| test 18 | 1020 | 31,500 | 400 | 255 | 200 | −17.84 |

| test 19 | 1020 | 36,225 | 800 | 300 | 250 | −17.58 |

| test 20 | 1020 | 40,950 | 1200 | 120 | 290 | −18.31 |

| test 21 | 1200 | 22,050 | 2000 | 255 | 110 | −15.01 |

| test 22 | 1200 | 26,775 | 400 | 300 | 150 | −16.14 |

| test 23 | 1200 | 31,500 | 800 | 120 | 200 | −17.57 |

| test 24 | 1200 | 36,225 | 1200 | 165 | 250 | −15.49 |

| test 25 | 1200 | 40,950 | 1600 | 210 | 290 | −14.56 |

| Factors | R | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| diaphragm wall thickness | −22.360 | −19.402 | −18.084 | −18.012 | −15.754 | 6.606 |

| elastic modulus of diaphragm wall | −19.276 | −19.064 | −18.576 | −18.348 | −18.348 | 0.928 |

| the scope of grouting reinforcement of the transverse channel | −19.900 | −18.720 | −18.526 | −18.252 | −18.214 | 1.686 |

| the thickness of the initial branch of the transverse channel | −20.198 | −19.050 | −18.370 | −18.110 | −17.884 | 2.314 |

| thickness of initial branch of advanced starting channel | −18.830 | −18.260 | −19.040 | −18.610 | −18.872 | 0.780 |

| Factors | Sum of Partial Variance Square /S | Degree of Freedom /f | Mean Square /V | F | PF | Significant Degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| diaphragm wall thickness | 117.088 | 4 | 29.272 | 37.390 | 0.002 | 3 |

| elastic modulus of the diaphragm wall | 3.625 | 4 | 0.906 | 1.158 | 0.445 | 0 |

| the scope of grouting reinforcement of the transverse channel | 9.525 | 4 | 2.381 | 3.042 | 0.153 | 1 |

| the thickness of the initial branch of the transverse channel | 17.434 | 4 | 4.359 | 5.567 | 0.062 | 2 |

| thickness of initial branch of advanced starting channel | 1.806 | 4 | 0.452 | 0.577 | 0.696 | 0 |

| Error | 3.131 | 4 | 0.783 | — | — | — |

| the critical value of F distribution | F0.01(4,4) = 16.00 F0.05(4,4) = 6.39 F0.1(4,4) = 4.11 | |||||

| Index | Diaphragm Wall Thickness | Elastic Modulus of Diaphragm Wall | The Scope of Grouting Reinforcement of the Transverse Channel | The Thickness of the Initial Branch of the Transverse Channel | Thickness of Initial Branch of Advanced Starting Channel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sensitivity parameters | 0.627 | 0.087 | 0.248 | 0.241 | 0.031 |

| Control Index | 75% × Warning Value | Value 1 | 90% × Warning Value | Value 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| diaphragm wall thickness (mm) | 917.72 | 950 | 462.02 | 500 |

| the scope of grouting reinforcement (mm) | 1618.31 | 1600 | 525.15 | 550 |

| the thickness of the initial branch of the transverse channel (mm) | 208.39 | 200 | 85.60 | 100 |

| Pre-Optimization Scheme | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| diaphragm wall thickness (mm) | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 600 | 600 | 600 | 600 |

| the scope of grouting reinforcement (mm) | 1600 | 550 | 1600 | 550 | 1600 | 550 | 1600 | 550 |

| the thickness of the initial branch of the transverse channel (mm) | 200 | 200 | 100 | 100 | 200 | 200 | 100 | 100 |

| Support Parameters | Diaphragm Wall Thickness (mm) | The Scope of Grouting Reinforcement (mm) | The Thickness of the Initial Branch of the Transverse Channel (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| pre-optimization plan | 1200 | 2000 | 300 |

| optimized plan | 1000 | 1600 | 100 |

| material savings percentage | 16.67% | 20.00% | 66.67% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ke, X.; Tian, X.; Lu, L.; Ruan, Y.; Chen, T.; Yu, H. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis and Optimization Design of Shield Lateral Shifting Launching Technology Based on Orthogonal Analysis Method. Buildings 2026, 16, 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010105

Ke X, Tian X, Lu L, Ruan Y, Chen T, Yu H. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis and Optimization Design of Shield Lateral Shifting Launching Technology Based on Orthogonal Analysis Method. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):105. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010105

Chicago/Turabian StyleKe, Xin, Xinyu Tian, Lingwei Lu, Yanmei Ruan, Tong Chen, and Huiru Yu. 2026. "Parameter Sensitivity Analysis and Optimization Design of Shield Lateral Shifting Launching Technology Based on Orthogonal Analysis Method" Buildings 16, no. 1: 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010105

APA StyleKe, X., Tian, X., Lu, L., Ruan, Y., Chen, T., & Yu, H. (2026). Parameter Sensitivity Analysis and Optimization Design of Shield Lateral Shifting Launching Technology Based on Orthogonal Analysis Method. Buildings, 16(1), 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010105