Identification of Spatial Influencing Factors and Enhancement Strategies for Cultural Tourism Experience in Huizhou Historic Districts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Objects, Data, and Methods

2.1. Study Objects

2.2. Data Source

2.2.1. Historic District Geographic Spatial Information Data

2.2.2. Historic District Cultural Tourism Experience Evaluation Data

2.3. Study Methods

3. Results

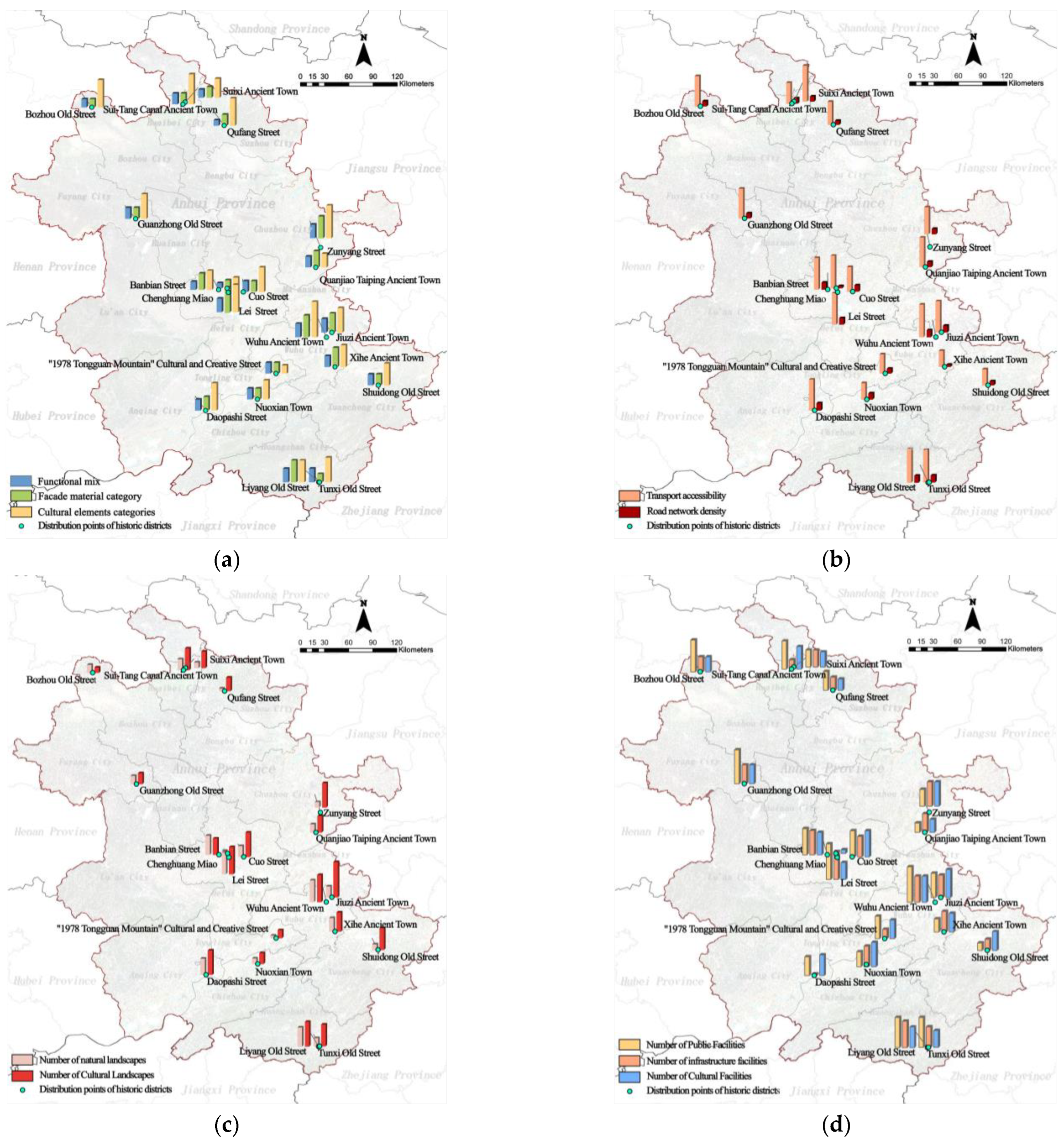

3.1. Historic District Spatial Form Indicator Analysis

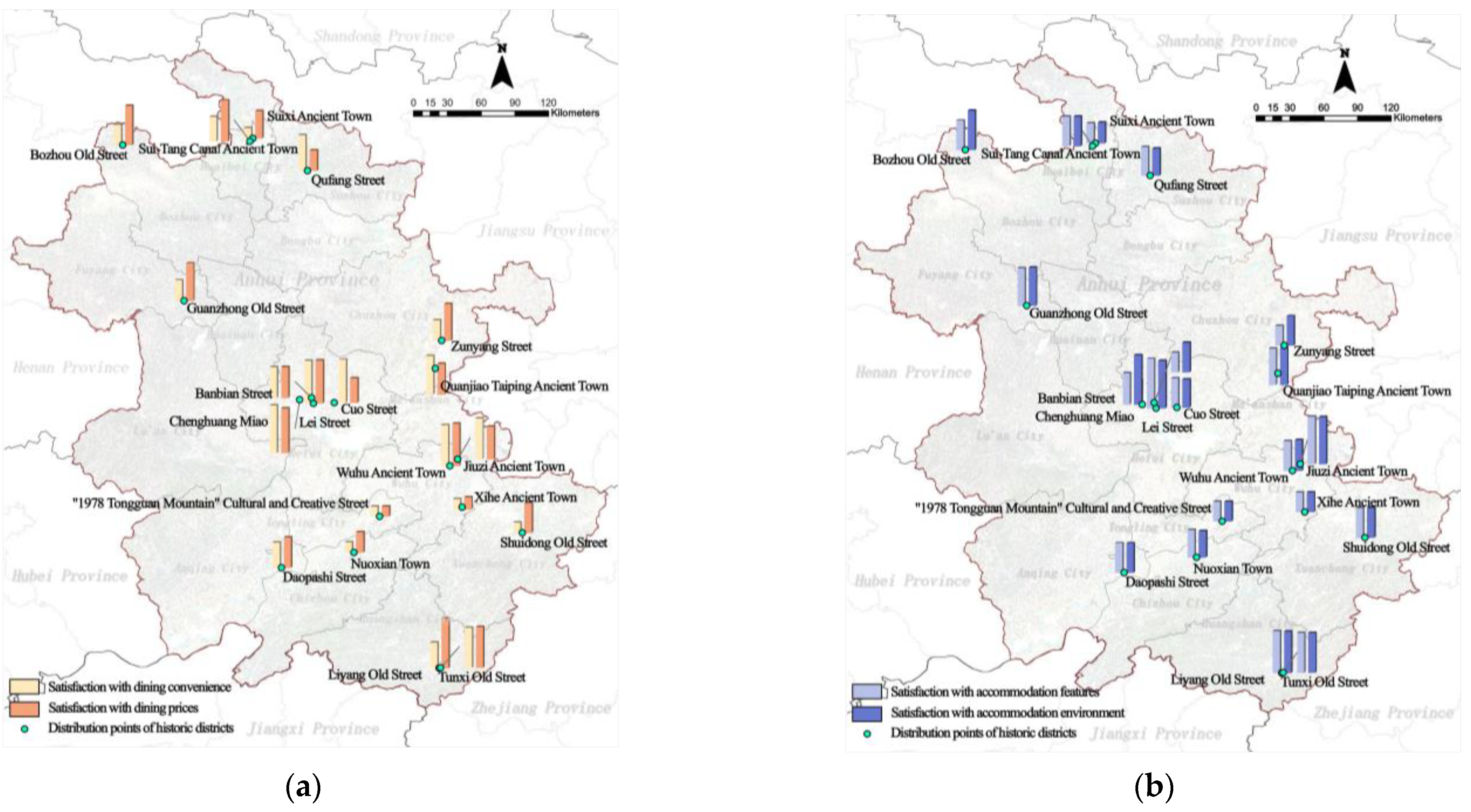

3.2. Analysis of Cultural Tourism Experience Indicators in Historic Districts

3.3. The Correlation Between the Spatial Form of Historic Districts and Cultural Tourism Experiences

3.3.1. Regression Analysis Steps

3.3.2. Regression Analysis Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- General Office of the State Council. Opinions of the General Office of the State Council on Further Stimulating the Consumption Potential of Culture and Tourism. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2019-08/23/content_5423809.htm (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Guo, R.; He, Y.; Zhang, X.; He, L.; Zhou, Q.; He, G. Semantic Comparison of Online Texts for Historical and Newly Constructed Replica Ancient Towns from a Tourist Perception Perspective: A Case Study of Tongguan Kiln Ancient Town and Jinggang Ancient Town. Land 2024, 13, 2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, K.; Xu, J. Formation Process and Spatial Representation of Tourist Destination Personality from the Perspective of Cultural Heritage: Application in Traditional Villages in Ancient Huizhou, China. Land 2024, 13, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yu, W. Canal Heritage Tourism Utilization Models: Experience and Inspirations from the Grand Canal (Beijing Section). Land 2024, 13, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, J.; Lin, Y.; Xiao, L.; Zhou, J. Revitalizing Historic Districts: Identifying Built Environment Predictors for Street Vibrancy Based on Urban Sensor Data. Cities 2021, 117, 103305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Hu, X.; Wang, J.; Lu, A. How Diversity and Accessibility Affect Street Vitality in Historic Districts? Land 2023, 12, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIAM. The Athens Charter. In Proceedings of the 4th Congress of Congress International Architecture Modern, Athens, Greece, 29–31 August 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 187–199. [Google Scholar]

- Furlan, R.; Petruccioli, A.; Jamaleddin, M. The authenticity of place-making: Spaceand character of the regenerated historic district in Msheireb, Downtown Doha (state of Qatar). Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2019, 13, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, J.; Zheng, Y. Preservation and Renewal: A Study on Visual Evaluation of Urban Historical and Cultural Street Landscape in Quanzhou. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, X. Vitality Evaluation of Public Spaces in Historical and Cultural Blocks Based on Multi-So-urce Data, a Case Study of Suzhou Changmen. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Sun, J.; Wang, Z.; Jin, S. Influencing Factors of Street Vitality in Historic Districts Based on Multisource Data: Evidence from China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Ahmad, Y.; Mohidin, H.H.B. Spatial Form and Conservation Strategy of Sishengci Historic District in Che-ngdu, China. Heritage 2023, 6, 891–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, X.; Dai, Z.; Hermaputi, R.L.; Hua, C.; Li, Y. Spatial Layout and Coupling of Urban Cultural Relics: Analyzing Historical Sites and Commercial Facilities in District III of Shaoxing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Chiou, S.-C. A Study on the Sustainable Development of Historic District Landscapes Based on Place Attachment among Tourists: A Case Study of Taiping Old Street, Taiwan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosone, M.; Nocca, F.; Fusco Girard, L. The Circular City Implementation: Cultural Heritage and Digital Technology. In Culture and Computing. Interactive Cultural Heritage and Arts; Rauterberg, M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 40–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotsch, P.M. Tourism’s uneven impact: History on Cannery Row. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 779–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, N. Baltimore and Lowell: Two American approaches. Built Environ. 1986, 12, 145–152. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23286695 (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Kotler, P.; Baloglu, S.; Makens, J.; Bowen, J. Marketing for Hospitality and Tourism, 7th ed.; Pearson International: London, UK, 2016; pp. 507–549. [Google Scholar]

- Frochot, I.; Hughes, H. HISTOQUAL: The development of a Historic House Assessment Scale. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Rollo, J.; Jones, D.S.; Esteban, Y.; Tong, H.; Mu, Q. Towards Sustainable Heritage Tourism: A Space Syntax-Based Analysis Method to Improve Tourists’ Spatial Cognition in Chinese Historic Districts. Buildings 2020, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Pan, Y.; Gu, M.; Liu, Y.; Lei, L. Research on the Paths and Strategies of the Integrated Development of Culture and Tourism Industry in Urban Historical Blocks. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1016801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimura, T. Cultural Heritage and Tourism in Japan; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 274–290. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, S.; Li, J.; Wang, M.; Ma, H. Post-Renewal Evaluation of an Urbanized Village with Cultural Resources Based on Multi Public Satisfaction: A Case Study of Nantou Ancient City in Shenzhen. Land 2023, 12, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skotis, A.; Livas, C. A Data-Driven Analysis of Experience in Urban Historic Districts. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2022, 3, 100052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfi, S.; Hall, C.M.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M. Exploring the Nexus of Heritage Tourism and Sustainable Development: A Comprehensive Review. J. Herit. Tour. 2020, 15, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatori, A.; Smith, M.K.; Puczko, L. Experience-Involvement, Memorability and Authenticity: The Service Provider’s Effect on Tourist Experience. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yin, P.; Peng, Y. Effect of Commercialization on Tourists’ Perceived Authenticity and Satisfaction in the Cultural Heritage Tourism Context: Case Study of Langzhong Ancient City. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Zheng, Q.; Ng, P. A Study on the Coordinative Green Development of Tourist Experience and Commercial-ization of Tourism at Cultural Heritage Sites. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Q.; Qin, W. Evaluation of Authentic Perception of Urban Historical and Cultural Blocks under Global Tourism. J. Cent. South Univ. For. Technol. 2024, 44, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhu, H.; Zhao, W. Evaluating Scientific Tourism of Geoheritage: An Empirical Study of Fangshan Global Geopark in Beijing. Land 2024, 13, 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, P.G.; Burtenshaw, P. Heritage Sites: Economic Incentives, Impacts, and Commercialization. In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology; Smith, C., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 4989–4995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, W.; Zhu, T.; Xia, J.; Zhou, Y.; Lai, Y.; Jiang, J.; Li, Q. Portraying the Spatial Dynamics of Urban Vibrancy Using Multisource Urban Big Data. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2020, 80, 101428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, W.; He, C.; Lv, S. Sustainable Renewal of Spontaneous Spatial Characteristics of a Historical–Cultural District: A Case Study of Tanhualin, Wuhan, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Martí Casanovas, M.; Bosch González, M.; Sun, S. Revitalizing Heritage: The Role of Urban Morphology in Creating Public Value in China’s Historic Districts. Land 2024, 13, 1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wu, A.N.; Biljecki, F. Classification of Urban Morphology with Deep Learning: Application on Urban Vitality. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2021, 90, 101706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Zhao, J.; Li, M. A Study on the Influencing Factors of the Vitality of Street Corner Spaces in Historic Districts: The Case of Shanghai Bund Historic District. Buildings 2024, 14, 2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wold, S.; Albano, C.; Dunn, W.J. Pattern Regression Finding and Usingregularities in Multivariate Data; Analysis Applied Science Publication: London, UK, 1983; pp. 147–188. [Google Scholar]

- Huiwen, W.; Zaibin, W.; Jie, M. Partial Least Squares Regression—Linear and Nonlinear Methods; National Defense Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2006; pp. 138–149. [Google Scholar]

- Wentong, Z.; Wei, D. Advanced SPSS Statistical Analysis, 2nd ed.; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2015; pp. 130–132. [Google Scholar]

| Number | Name | Location | Area Occupied (hm2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Liyang Old Street | Tunxi District, Huangshan City | 6 |

| 2 | Tunxi Old Street | Tunxi District, Huangshan City | 13 |

| 3 | Nuoxian Town | Guichi District, Chizhou City | 3.6 |

| 4 | Shuidong Old Street | Xuanzhou District, Xuancheng City | 6 |

| 5 | Suixi Ancient Town | Suixi County, Huaibei City | 9 |

| 6 | Jiuzi Ancient Town | Jiujiang District, Wuhu City | 2.15 |

| 7 | Wuhu Ancient Town | Jinghu District, Wuhu City | 30 |

| 8 | Sui-Tang Canal Ancient Town | Xiangshan District, Huaibei City | 34.87 |

| 9 | Quanjiao Taiping Ancient Town | Quanjiao County, Chuzhou City | 12 |

| 10 | Xihe Ancient Town | Wanchai District, Wuhu City | 33.33 |

| 11 | Daopashi Street | Yingjiang District, Anqing City | 2.24 |

| 12 | Guanzhong Old Street | Yingshang County, Fuyang City | 7 |

| 13 | Bozhou Old Street | Qiao Cheng District, Bozhou City | 9.6 |

| 14 | “1978 Tongguan Mountain” Cultural and Creative Street | Tongguan District, Tongling City | 3.26 |

| 15 | Lei Street | Baohe District, Hefei City | 2.2 |

| 16 | Cuo Street | Feidong County, Hefei City | 6.2 |

| 17 | Zunyang Street | Langya District, Chuzhou City | 5.8 |

| 18 | Qufang Street | Yongqiao District, Suzhou City | 1.7 |

| 19 | Banbian Street | Shushan District, Hefei City | 3.47 |

| 20 | Chenghuang Miao | Luyang District, Hefei City | 10 |

| Classification | Independent Variable | Indicator | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Architectural space | X1 | Building density | Number of buildings within a district per unit area |

| X2 | Functional mixing degree | Diversity of functions in the district | |

| Architectural space | X3 | Façade material category | Number of material categories for building facades within the district |

| X4 | Cultural elements categories | Number of categories of expressions of cultural elements such as Horse-head Walls and antique doorways in the district | |

| Traffic space | X5 | Transport accessibility | Ease of access to the district for tourists |

| X6 | Road network density | Intra-neighborhood traffic network density | |

| Landscape space | X7 | Number of natural landscapes | Number of natural landscape vignettes in the district |

| X8 | Number of Cultural landscapes | Number of cultural landscape features within the district | |

| Facility space | X9 | Number of Public facilities | Number of public service facilities such as tourist service centers, guide maps, and street offices within the district area. |

| X10 | Number of infrastructure facilities | Number of basic facilities such as streetlights, traffic signs, and leisure seats within the district | |

| X11 | Number of cultural facilities | Number of cultural facilities such as cultural signboards, cultural sketches and publicity boards within the street area |

| Classification | Independent Variable | Indicator | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dining experience | Y1 | Satisfaction with dining convenience | Tourists’ evaluation of the distribution of meals and the waiting situation before dining |

| Y2 | Satisfaction with dining prices | Tourists’ evaluation of overall price of meals | |

| Y3 | Satisfaction with accommodation environment | Tourists’ evaluation of the hygiene and safety of the accommodation environment | |

| Y4 | Satisfaction with accommodation features | Tourists’ evaluation of the unique features and services of the accommodation | |

| Lodging experience | Y5 | Satisfaction with traffic information service | Tourists’ evaluation of the richness of the transportation information services provided |

| Y6 | Satisfaction with traditional street texture | Tourists’ evaluation of the preservation and continuation of traditional spatial forms in streets and alleys | |

| Transportation experience | Y7 | Satisfaction with the overall atmosphere of the district | Tourists’ evaluation of the cultural atmosphere embodied in the block’s spaces and landscapes |

| Y8 | Satisfaction with the cultural branding of the district | Tourists’ evaluation of the construction of block culture brand | |

| Sightseeing experience | Y9 | Satisfaction with shopping environment | Tourists’ evaluation of commodity prices in the shopping environment, professional quality of practitioners, and service attitude of managers |

| Y10 | Satisfaction with the characteristics of cultural and creative products | Tourists’ evaluation of the richness of cultural activity types | |

| Shopping experience | Y11 | Satisfaction with the characteristics of cultural and recreational activities | Tourists’ evaluation of the compatibility of the content and historical features of cultural activities and the quality of the activities |

| Y12 | Satisfaction with types of cultural and entertainment activities | Tourists’ evaluation of the richness of cultural activity types |

| Number of Principal Components (h) | SS | PRESS | Qh2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 142.615 | 184.584 | 1 |

| 2 | 121.04 | 185.048 | −0.298 |

| 3 | 111.61 | 198.045 | −0.636 |

| 4 | 102.542 | 220.749 | −0.978 |

| 5 | 96.4 | 269.496 | −1.628 |

| 6 | 91.463 | 301.51 | −2.128 |

| 7 | 83.209 | 330.299 | −2.611 |

| 8 | 75.992 | 327.358 | −2.934 |

| 9 | 73.557 | 342.886 | −3.512 |

| 10 | 69.939 | 456.834 | −5.211 |

| 11 | 68.718 | 534.491 | −6.642 |

| 1 Principal Component | 2 Principal Components | 3 Principal Components | 4 Principal Components | 6 Principal Components | 7 Principal Components | 8 Principal Components | 9 Principal Components | 10 Principal Components | 11 Principal Components | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Building density | 0.162 | 0.63 | 0.774 | 0.784 | 0.779 | 0.836 | 0.841 | 0.835 | 0.829 | 0.83 |

| Functional mixing degree | 0.975 | 1.013 | 0.973 | 1.021 | 1.041 | 1.027 | 1.004 | 1.01 | 1.013 | 1.01 |

| Facade material category | 1.002 | 0.92 | 0.902 | 0.913 | 0.958 | 0.95 | 0.951 | 0.944 | 0.963 | 0.961 |

| Cultural elements categories | 0.826 | 0.78 | 0.885 | 1.016 | 0.979 | 0.993 | 0.971 | 0.967 | 0.971 | 0.968 |

| Transport accessibility | 0.731 | 1.047 | 1.056 | 1.036 | 1.013 | 0.986 | 0.99 | 0.993 | 0.982 | 0.983 |

| Road network density | 1.193 | 1.138 | 1.089 | 1.096 | 1.053 | 1.031 | 1.031 | 1.027 | 1.016 | 1.032 |

| Number of natural landscapes | 1.336 | 1.24 | 1.194 | 1.145 | 1.162 | 1.152 | 1.13 | 1.13 | 1.143 | 1.138 |

| Number of cultural landscapes | 1.134 | 1.055 | 1.013 | 0.985 | 0.972 | 0.998 | 1.061 | 1.056 | 1.049 | 1.048 |

| Number of public facilities | 1.115 | 1.057 | 1.034 | 0.987 | 0.999 | 0.975 | 0.953 | 0.969 | 0.988 | 0.986 |

| Number of infrastructure facilities | 1.164 | 1.057 | 1.095 | 1.052 | 1.058 | 1.065 | 1.099 | 1.094 | 1.082 | 1.078 |

| Number of cultural facilities | 0.844 | 0.921 | 0.913 | 0.915 | 0.941 | 0.957 | 0.936 | 0.942 | 0.931 | 0.934 |

| X | Independent Variable | Principal Component U1 |

|---|---|---|

| X1 | Building density | 0.048 |

| X2 | Functional mixing degree | 0.606 |

| X3 | Facade material category | 0.536 |

| X4 | Cultural elements categories | 0.405 |

| X5 | Transport accessibility | 0.148 |

| X6 | Road network density | 0.599 |

| X7 | Number of natural landscapes | 0.652 |

| X8 | Number of cultural landscapes | 0.621 |

| X9 | Number of public facilities | 0.475 |

| X10 | Number of infrastructure facilities | 0.531 |

| X11 | Number of cultural facilities | 0.504 |

| Comprehensive | 0.466 |

| Y | Dependent Variable | Principal Component V1 |

|---|---|---|

| Y1 | Satisfaction with dining convenience | 0.561 |

| Y2 | Satisfaction with dining prices | 0.513 |

| Y3 | Satisfaction with accommodation environment | 0.64 |

| Y4 | Satisfaction with accommodation features | 0.618 |

| Y5 | Satisfaction with traffic information service | 0.527 |

| Y6 | Satisfaction with traditional street texture | 0.466 |

| Y7 | Satisfaction with the overall atmosphere of the district | 0.537 |

| Y8 | Satisfaction with the cultural branding of the district | 0.623 |

| Y9 | Satisfaction with shopping environment | 0.222 |

| Y10 | Satisfaction with the characteristics of cultural and creative products | 0.67 |

| Y11 | Satisfaction with the characteristics of cultural and recreational activities | 0.496 |

| Y12 | Satisfaction with types of cultural and entertainment activities | 0.552 |

| Comprehensive | 0.535 |

| Average Value | Standard Deviation | Building Density | Functional Mix Degree | Facade Material Category | Cultural Elements Categories | Transport Accessibility | Road Network Density | Number of Natural Landscapes | Number of Cultural Landscapes | Number of Public Facilities | Number of Infrastructure Facilities | Number of Cultural Facilities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Building density | 41.850 | 20.551 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Functional mix degree | 3.950 | 0.945 | 0.287 | 1 | |||||||||

| Facade material category | 5.250 | 1.943 | 0.084 | 0.609 *** | 1 | ||||||||

| Cultural elements categories | 8.450 | 2.502 | 0.385 * | 0.389 * | 0.355 | 1 | |||||||

| Transport accessibility | 1.601 | 0.379 | −0.041 | 0.061 | 0.211 | 0.130 | 1 | ||||||

| Road network density | 0.320 | 0.089 | −0.143 | 0.555 ** | 0.311 | 0.385 * | 0.440 * | 1 | |||||

| Number of natural landscapes | 3.800 | 2.308 | 0.059 | 0.478 ** | 0.692 *** | 0.427 * | 0.367 | 0.572 *** | 1 | ||||

| Number of cultural landscapes | 6.900 | 2.936 | 0.355 | 0.719 *** | 0.650 *** | 0.551 ** | 0.180 | 0.531 ** | 0.572 *** | 1 | |||

| Number of public facilities | 11.950 | 4.883 | 0.093 | 0.410 * | 0.240 | 0.515 ** | 0.403 * | 0.617 *** | 0.574 *** | 0.257 | 1 | ||

| Number of infrastructure facilities | 9.250 | 3.959 | 0.196 | 0.567 *** | 0.641 *** | 0.339 | 0.196 | 0.444 * | 0.478 ** | 0.441 * | 0.453 ** | 1 | |

| Number of cultural facilities | 10.200 | 3.105 | 0.209 | 0.668 *** | 0.410 * | 0.476 ** | −0.161 | 0.627 *** | 0.424 * | 0.637 *** | 0.383 * | 0.522 ** | 1 |

| Y1 | Y2 | Y3 | Y4 | Y5 | Y6 | Y7 | Y8 | Y9 | Y10 | Y11 | Y12 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | Perturbation coefficient | −0.057 | 0.034 | −0.091 | 0.037 | 0.3 | 0.516 | 0.119 | 0.028 | −0.091 | −0.107 | 0.109 | −0.196 |

| X2 | Perturbation coefficient | 0.115 | 0.333 | 0.281 | 0.501 | 0.662 | 0.754 | 0.228 | 0.318 | 0.307 | 0.353 | 0.476 | 0.345 |

| X3 | Perturbation coefficient | 0.28 | 0.326 | 0.34 | 0.362 | 0.329 | 0.544 | 0.425 | 0.316 | 0.384 | 0.494 | 0.591 | 0.426 |

| X4 | Perturbation coefficient | 0.241 | 0.465 | 0.185 | 0.239 | 0.475 | 0.470 | 0.646 | 0.195 | 0.18 | 0.353 | 0.289 | 0.086 |

| X5 | Perturbation coefficient | 0.526 | 0.655 | 0.543 | 0.375 | 0.261 | 0.029 | 0.205 | 0.094 | 0.483 | 0.511 | 0.249 | 0.212 |

| X6 | Perturbation coefficient | 0.493 | 0.536 | 0.547 | 0.583 | 0.562 | 0.359 | 0.405 | 0.411 | 0.404 | 0.638 | 0.585 | 0.567 |

| X7 | Perturbation coefficient | 0.476 | 0.565 | 0.506 | 0.504 | 0.493 | 0.502 | 0.577 | 0.462 | 0.478 | 0.713 | 0.859 | 0.509 |

| X8 | Perturbation coefficient | 0.410 | 0.339 | 0.316 | 0.515 | 0.552 | 0.756 | 0.483 | 0.324 | 0.420 | 0.524 | 0.536 | 0.327 |

| X9 | Perturbation coefficient | 0.406 | 0.577 | 0.504 | 0.538 | 0.532 | 0.35 | 0.617 | 0.355 | 0.342 | 0.509 | 0.531 | 0.342 |

| X10 | Perturbation coefficient | 0.32 | 0.365 | 0.431 | 0.424 | 0.517 | 0.614 | 0.422 | 0.622 | 0.342 | 0.424 | 0.546 | 0.625 |

| X11 | Perturbation coefficient | 0.091 | 0.14 | 0.134 | 0.221 | 0.499 | 0.581 | 0.347 | 0.405 | 0.269 | 0.351 | 0.585 | 0.476 |

| Y1 | Y2 | Y3 | Y4 | Y5 | Y6 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction with Dining Convenience | Satisfaction with Dining Prices | Satisfaction with Accommodation Environment | Satisfaction with Accommodation Features | Satisfaction of Traffic Information Service | Satisfaction of Traditional Street Texture | ||

| Architectural space | |||||||

| X1 Building density | coefficient | −0.057 | 0.034 | −0.091 | 0.037 | 0.3 | 0.516 |

| p | ** | ||||||

| X2 Functional mixing degree | coefficient | 0.115 | 0.333 | 0.281 | 0.501 | 0.662 | 0.754 |

| p | ** | *** | *** | ||||

| X3 Facade material category | coefficient | 0.28 | 0.326 | 0.34 | 0.362 | 0.329 | 0.544 |

| p | ** | ||||||

| X4 Cultural elements categories | coefficient | 0.241 | 0.465 | 0.185 | 0.239 | 0.475 | 0.470 |

| p | ** | ** | ** | ||||

| Traffic space | |||||||

| X5 Transport accessibility | coefficient | 0.526 | 0.655 | 0.543 | 0.375 | 0.261 | 0.029 |

| p | *** | *** | ** | ||||

| X6 Road network density | coefficient | 0.493 | 0.536 | 0.547 | 0.583 | 0.562 | 0.359 |

| p | ** | ** | ** | *** | *** | ||

| Landscape space | |||||||

| X7 Number of natural landscapes | coefficient | 0.476 | 0.565 | 0.506 | 0.504 | 0.493 | 0.502 |

| p | ** | *** | ** | ** | ** | ** | |

| X8 Number of Cultural Landscapes | coefficient | 0.410 | 0.339 | 0.316 | 0.515 | 0.552 | 0.756 |

| p | * | ** | ** | *** | |||

| Facility space | |||||||

| X9 Number of Public Facilities | coefficient | 0.406 | 0.577 | 0.504 | 0.538 | 0.532 | 0.35 |

| p | * | *** | ** | ** | ** | ||

| X10 Number of infrastructure facilities | coefficient | 0.32 | 0.365 | 0.431 | 0.424 | 0.517 | 0.614 |

| p | * | * | ** | *** | |||

| X11 Number of Cultural Facilities | coefficient | 0.091 | 0.14 | 0.134 | 0.221 | 0.499 | 0.581 |

| p | ** | *** | |||||

| R-Square 3 | 0.229 | 0.363 | 0.29 | 0.375 | 0.484 | 0.511 | |

| Y7 | Y8 | Y9 | Y10 | Y11 | Y12 | ||

| Satisfaction with the Overall Atmosphere of the District | Satisfaction with the Cultural Branding of the District | Satisfaction with Shopping Environment | Satisfaction with the Characteristics of Cultural and Creativeproduct | Satisfaction with the Characteristics of Cultural and Recreational Activities | Satisfaction with Types of Cultural and Entertainment Activities | ||

| Architectural space | |||||||

| X1 Building density | coefficient | 0.119 | 0.028 | −0.091 | −0.107 | 0.109 | −0.196 |

| p | |||||||

| X2 Functional mixing degree | coefficient | 0.228 | 0.318 | 0.307 | 0.353 | 0.476 | 0.345 |

| p | ** | ||||||

| X3 Facade material category | coefficient | 0.425 | 0.316 | 0.384 | 0.494 | 0.591 | 0.426 |

| p | * | * | ** | *** | * | ||

| X4 Cultural elements categories | coefficient | 0.646 | 0.195 | 0.18 | 0.353 | 0.289 | 0.086 |

| p | *** | ||||||

| Traffic space | |||||||

| X5 Transport accessibility | coefficient | 0.205 | 0.094 | 0.483 | 0.511 | 0.249 | 0.212 |

| p | ** | ** | |||||

| X6 Road network density | coefficient | 0.405 | 0.411 | 0.404 | 0.638 | 0.585 | 0.567 |

| p | * | * | * | *** | *** | *** | |

| Landscape space | |||||||

| X7 Number of natural landscapes | coefficient | 0.577 | 0.462 | 0.478 | 0.713 | 0.859 | 0.509 |

| p | *** | ** | ** | *** | *** | ** | |

| X8 Number of cultural landscapes | coefficient | 0.483 | 0.324 | 0.420 | 0.524 | 0.536 | 0.327 |

| p | ** | * | ** | ** | |||

| Facility space | |||||||

| X9 Number of public facilities | coefficient | 0.617 | 0.355 | 0.342 | 0.509 | 0.531 | 0.342 |

| p | *** | ** | ** | ||||

| X10 Number of infrastructure facilities | coefficient | 0.422 | 0.622 | 0.342 | 0.424 * | 0.546 | 0.625 |

| p | * | *** | * | ** | *** | ||

| X11 Number of cultural facilities | coefficient | 0.347 | 0.405 | 0.269 | 0.351 | 0.585 | 0.476 |

| p | * | *** | ** | ||||

| R-Square 3 | 0.386 | 0.26 | 0.158 | 0.479 | 0.58 | 0.317 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Du, S.; Xiao, Y. Identification of Spatial Influencing Factors and Enhancement Strategies for Cultural Tourism Experience in Huizhou Historic Districts. Buildings 2025, 15, 1568. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15091568

Yang Y, Du S, Xiao Y. Identification of Spatial Influencing Factors and Enhancement Strategies for Cultural Tourism Experience in Huizhou Historic Districts. Buildings. 2025; 15(9):1568. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15091568

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yue, Shaoshan Du, and Yang Xiao. 2025. "Identification of Spatial Influencing Factors and Enhancement Strategies for Cultural Tourism Experience in Huizhou Historic Districts" Buildings 15, no. 9: 1568. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15091568

APA StyleYang, Y., Du, S., & Xiao, Y. (2025). Identification of Spatial Influencing Factors and Enhancement Strategies for Cultural Tourism Experience in Huizhou Historic Districts. Buildings, 15(9), 1568. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15091568